ABSTRACT

In recent philosophical and (neuro)psychological discussions of phenomena such as motivated forgetting, memory inhibition, self-deception, and implicit bias, various authors have suggested that repression might be a useful notion to make sense of these phenomena, or that these phenomena indeed provide evidence for repression. However, surprisingly, these claims usually do not rely on any explicit model of repression. Consequently, it remains unclear whether invoking repression in these discussions is justified. In this paper, I propose a psychological “how-possibly” model that can serve as a basis for scientific research that I call the hybrid model of repression. This model combines the advantages while avoiding the problems of two types of models of repression – the higher-order model and the separation model – that have been discussed and defended by different authors and that both have their origin in Freud. This “how-possibly” model may then set the stage for further empirical research, which can form the basis for a “how-actually” model in the longer run.

Introduction

According to Freudian psychoanalysis, repression is an ego-defense mechanism by which the ego protects itself from inner conflicts by rendering at least one of the mental states that create the conflict unconscious. Due to its psychoanalytic origin, repression has had a rather bad reputation amongst academic psychologists and analytic philosophers. To put it in the words of the psychologist James Uleman: “the psychoanalytic unconscious [i.e. the repressed unconscious] is widely acknowledged to be a failure of scientific theory because evidence of its major components cannot be observed, measured precisely, or manipulated easily” (Ulemann, Citation2005, p. 5).

While Ulemann might be right that this is the standard view in contemporary science, one might be surprised to find that talk about repression is far from absent in contemporary philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience. First, there is a small but increasing trend among cognitive neuropsychologists, so-called neuropsychoanalysts (Axmacher et al., Citation2010; Bazan, Citation2013; Erdelyi, Citation2006; Fotopoulou, Citation2013; Solms, Citation2013), to investigate the central notions of Freudian psychoanalysis with neuroscientific tools. Repression, thereby, forms the core target of investigation. Indirect evidence for repression is taken to be found in studies on motivated forgetting and memory inhibition (Anderson, Citation2001; Berlin, Citation2011). These phenomena involve suppression – the voluntary counterpart of repression. While one of the goals of neuropsychoanalysts is to scientifically investigate core Freudian notions, the interest in repression is also motivated by empirical findings that seem to be best explained in terms of repression such as memory distortions (Axmacher et al., Citation2010) and the finding that people with a repressive personality style are more likely to be physically ill (Berlin, Citation2011, p. 14).

A second area where the notion of repression is used is in the contemporary philosophical and psychological literature on self-deception. Different authors argue that repression is just a form of self-deception (Billon, Citation2011; Boag, Citation2007, Citation2017); that self-deception involves repression (Cohen, Citation1995; Johnston, Citation1995); or that there is a link between the tendency to self-deceive and the tendency to repress. For example, different studies report evidence that “repressors”, i.e. people who tend to repress, score high on self-deception questionnaires (Derakshan, Citation1999; Furnham et al., Citation2002; Garssen, Citation2007). Others propose repression as one mechanism underlying anosognosia – an extreme form of self-deception where patients seem to be unaware of a rather obvious deficit, such as a paralyzed limb (Billon, Citation2011; Ramachandran, Citation1996). Again, others argue that the mechanism underlying self-deception involves repression. For example, the philosopher Kevin Lynch (Citation2014) argues that so-called intentionalist accounts of self-deception “are supposed to work by leading to the repression of one’s knowledge of the unwelcome considerations” (Lynch, Citation2014, p. 63 my italics). Lynch rejects intentionalist accounts of self-deception because he takes empirical evidence on thought-suppression to speak against the existence of repression.

Third, the well-known neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran suggests that depression arises due to a breakdown of the repression mechanism.

I suggest, therefore, that, to compensate for the growing awareness of death – of the terrifying annihilation that it portends – our brains also evolved a special purpose mechanism to selectively uncouple it from limbic/emotional centers in the brain, a mechanism akin to denial or “repression”. (…) Now, in my view at least, some forms of depression may arise when this particular mechanism goes awry, so that the person's coping mechanisms break down. (Ramachandran, Citation1996, pp. 359–360)

Fourth, different authors have discussed the idea that implicit attitudes, i.e. attitudes that do not correspond to one’s self-ascribed opinion, arise because people repress some of their attitudes (Gawronski et al., Citation2006; Krickel, Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2000). For example, the psychologists Timothy D. Wilson, Samuel Lindsey, and Tonya Y. Schooler (Citation2000) suggest that implicit attitudes may “result from repression, whereby an attitude is kept out of awareness because it is anxiety-provoking” (2000, p. 105). Gawronski et al. (Citation2006, pp. 493–494), however, argue that empirical evidence suggests that implicit attitudes are indeed conscious – which is in conflict with how repression is usually understood. I have argued (Krickel, Citation2018) that the empirical evidence only suggests that they can in principle be made conscious, which is compatible with the idea that they are repressed.

This brief (non-exhaustive) summary is offered to show that the notion of “repression” has not disappeared from contemporary psychology, neuroscience, and analytic philosophy. On the one hand, repression is taken to be an explanandum to be investigated, e.g. in neuropsychonalysis; on the other hand, repression is taken to be a potential explanans for other phenomena such as memory distortions, self-deception, depression, or implicit attitudes. This observation is in stark contrast with the widely held view among scientists that psychoanalysis, as well as the notion of repression, is a “scientific failure” that lacks empirical support. How to explain this tension? According to Simon Boag (Citation2012), the primary problem is a conceptual rather than empirical one as.

we cannot compare psychoanalytic theory with empirical evidence until we have clarified what we are talking about first. With respect to the empirical evaluation of repression, this first step, for the most part, has been neglected and, consequently, any claim that Freud’s theory of repression lacks empirical support is premature. (Boag, Citation2012)

The goal of the present paper is to present a model of repression – which I will call the hybrid model – that is as clear as possible so that it can be applied and evaluated in the different research contexts. This will be based on a summary of two prominent types of theories of repression. Before I outline my argument, it is important to note what is not the goal here.

First, my goal is not to provide an exegesis of Freud or to present and discuss all interpretations and accounts of repression that have been put forward since Freud. To be able to stay within paper length, I must ignore many accounts. The reader may excuse this ignorance – and see it as a rich source for future projects on comparing and taxonomizing the different accounts. My starting point is the discussion of the concept of repression in contemporary analytic philosophy. I will ground my discussion on the work of researchers in the analytic philosophical tradition such as W. D. Hart (Citation1982), Alexandre Billon (Citation2011), and Simon Boag (Citation2006, Citation2007, Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2017). These authors have helped to re-introduce the Freudian notion of repression to the analytic-philosophical discourse. Still, some ambiguities and unclarities remain. The hybrid model of repression that I present here is meant to be a clarification and integration of their core ideas while removing ambiguities and potential problems.

Second, my goal is not to show that the resulting proposal indeed is an account of what Freud or Freudian psychoanalysts take repression to be. Given the many different interpretations of Freud’s view and given the many ambiguities, unclarities and potential inconsistencies in Freud’s original views, at this point, I have to be indeterminate about that. My goal is to provide a model of repression that incorporates central features that many take to characterize repression – in a way that is clear, consistent, and in line with contemporary psychology, cognitive science, and neuroscience.

Finally, my goal is not to develop a model of repression that captures all clinical and non-clinical cases that have been categorized as cases of repression. My goal is to present a model that can potentially be applied in the contexts mentioned above, i.e. that can be used to systematically evaluate whether repression indeed can have the explanatory role that it is said to have for phenomena such as memory distortions, the correlation between repressive personality style and illness, self-deception, depression as a reaction to awareness of death, and implicit attitudes. These contexts are about adult minds and behaviors. The model that I am going to develop, thus, is a model of what may be called a cognitive notion of repression that requires higher cognitive capacities such as language. In this way, the model has a different target than, e.g. Mark Solms’s influential model, according to which repression consists in the proceduralization of illegitimate predictions (action plans) due to the ego’s being affectively overwhelmed with a problem (according to Solms, the Oedipus complex is an example of a problem that triggers this kind of repression) (see e.g. Smith & Solms, Citation2018; Solms, Citation2018). In that regard, I opt for pluralism – there may be different interrelated phenomena that could all be clustered as “repression”-phenomena and there may be different concepts of repression corresponding to them. Still, as I will show, the model that I am going to develop does not only combine the core ideas of two central types of models of repression but also has relevant similarities with, e.g. Solm’s model that may ground a family resemblance between the corresponding concepts and phenomena. However, elaborating on this idea must be left for future research. The main goal here is to develop and defend the hybrid model.

The paper proceeds as follows: in Section 2, I explain in more detail which features are often taken to characterize repression by providing what I call a surface description of the phenomenon. Furthermore, I formulate criteria of adequacy that a successful model of that type of repression has to satisfy – e.g. it must account for the surface description. Note once again that there may be some disagreement on the details. My analysis can be viewed as conditional: if one agrees that a phenomenon that has the features mentioned by the surface description counts as repression (i.e. the features may turn out to be sufficient but not necessary for repression), then one should agree that the hybrid model is an adequate model of repression.

In Section 3, I briefly summarize two types of models of repression that have been proposed by different authors and that both originate in Freud’s work – what I call the higher-order model and the separation model. I present two specific versions of each model and show how they fail to account for the criteria of adequacy formulated in Section 1. In Section 4, I develop my own proposal – the hybrid model of repression – that combines the core insights of higher-order models and separation models while avoiding their problems. I show how the hybrid model can account for all criteria of adequacy. Section 5 concludes.

A surface description of repression & criteria of adequacy

According to Freud and his followers, repression is an ego-defense mechanism, i.e. an action that the subject performs in order to protect herself from threats that conflict with the subject’s beliefs and desires and/or her self-image (Axmacher et al., Citation2010; Garssen, Citation2007). Contrary to a widespread view, repression does not primarily concern traumatic memories but rather it is wishes, desires, or affective states that create inner conflicts and are, thus, the target of repression (Axmacher et al., Citation2010; Boag, Citation2012, p. xiv). More specifically, repression can be characterized by means of what I call the “surface description” of repression. The surface description of repression lists those features that, according to the literature on repression, are essential features of repression, i.e. those features that a model or repressed must account for. I take the following five features to constitute this surface description:

| 1. | Repression starts with an inner conflict that consists in the incompatibility of the contents of two mental statesFootnote1 M1 and M2 where one is (derived from) the self-image, the internalized social norms, or moral beliefs of the subject. (Boag, Citation2012, pp. xi – xix; Hart, Citation1982) | ||||

For example, imagine you are in love with your best friend’s partner (this is a slight modification of an example used by Hart (Citation1982, p. 183)). You have the desire to spend time with him, you want to kiss him, and you fantasize about having sex with him. This creates an inner conflict as you also have the desire to be a good friend, and you have internalized the social norm that good friends do not fall in love with their best friends’ partners and do not have the desires and fantasies you have. Hence your desires, fantasies, etc. concerning your best friend’s partner are incompatible with your self-image and the social norms you have internalized, i.e. they create an inner conflict.

| 2. | Repression is an unconscious process (or “act”) that leads to an unconscious product (or “target”). (Boag, Citation2010, p. 167, Citation2012, p. 7; Hart, Citation1982, p. 180) | ||||

To avoid feeling bad due to the conflict, you repress (some) of the mental states that give rise to it. While this sounds intentional and conscious, when repressing you are not conscious of the mental states that you are repressing and neither are you conscious of the fact that you are repressing them. In our example, solving the conflict by means of repression is itself unconscious to you and renders your desires and fantasies involving your best friend’s partner unconscious.

| 3. | Repression is selective, i.e. not every conflict-inducing mental state is repressed. (Boag, Citation2007, p. 424) | ||||

Typically, in cases like our example, it is the desires and fantasies that are repressed and not your desire to be a good friend or the social norms you have internalized. Furthermore, some inner conflicts are conscious and are dealt with in other ways (such as the conflict between my desire to smoke and not to smoke at the same time that I solve by modifying one of the desires: I do not want to smoke more than one cigarette a day). Also, not every mental state that is connected to unpleasure is repressed. I do not repress my sensation of a bad stomach to protect myself from the pain. Rather, I pay full attention to it, search the internet for possible explanations for my symptoms, and plan to see the doctor the next day if I won’t feel better. Thus, repression is selective in the sense that not every pain-inducing mental state is targeted by repression. A model of repression has to clarify how this is possible by, e.g. explaining what the states that are targeted by repression have in common, which the states that are not targeted lack.

| 4. | Repression is a goal-directed action the subject is motivated to do. (Boag, Citation2010, p. 166; Hart, Citation1982) | ||||

Repression is a teleological concept, i.e. it describes an action or behavior that has the goal or purpose of protecting the self from inner conflicts (Hart, Citation1982).Footnote2 Repression happens for a reason (Billon, Citation2011). You repress your feelings and fantasies about your best friend’s partner in order to stop feeling guilty and in order to be able to maintain your belief that you are a good friend. This idea is captured by saying that repression happens intentionally (Billon, Citation2011, p. 4). As intentional action is often defined as involving consciousness, some authors argue that it suffices to view repression as a “motivated response” to a painful stimulus (Boag, Citation2010, p. 166, Citation2012, p. 7).

| 5. | Even though the repressed is unconscious it remains in existence. (Boag, Citation2012, p. 13) | ||||

That the repressed is not deleted but only rendered unconscious is crucial for the Freudian notion of repression. A theory of repression must at least in principle allow for the idea that the repressed keeps influencing you (e.g. by making you neurotic), that it may “return” (Boag, Citation2012, p. 31), and that it can be recovered by means of psychoanalytic therapy (for a critique of this idea see Grünbaum (Citation1984)). To go back to our example: you still have the feelings, fantasies and desires directed at your best friend’s partner – but you are not conscious of them anymore. The feelings, fantasies, and desires will keep influencing your thoughts and behavior. For example, you might have sexual dreams of your best friend’s partner, or you might feel strangely excited when he enters the room.

To summarize, repression can be characterized in the following way, which I will call “surface description” to indicate that this is not yet a full-fledged psychological model but only specifies the target of our model:

(Surface Description) Repression is an unconscious, goal-directed, non-deliberative, and selective act triggered by an inner conflict and by which the subject protects herself from the inner conflict by rendering conflict-inducing mental states unconscious without deleting them.

To be able to empirically verify whether repression is real or not, and to be able to use repression as an explanatory posit, we need a model of repression that is consistent and clear enough so that scientists can use it as the basis for their research. To create and evaluate a satisfying model of repression it should be evaluated based on a pre-defined list of criteria of adequacy. In the following I provide such a list.

First, and almost trivially, a satisfying model of repression must account for the surface description (see above). That is, the model must not be such that one of the conditions of the surface description must be rejected. It must clarify in which sense the product and the process of repression are unconscious, what exactly an inner conflict is and how it causes repression. Furthermore, the model must clarify how repression can be unconscious and non-deliberative, on the one hand, and at the same time goal-directed and selective, on the other. This implies that the model must dissolve the apparent paradoxical nature of the combination of the latter requirements. Finally, it must make sense of the idea that the relevant mental states are unconscious but still in existence.

Second, a model of repression must be psychological in the sense that it must characterize repression in psychological terminology rather than, say, neural or sociological terminology, to be able to account for the surface description of repression. For a model to be an adequate model of repression, it must be a psychological model rather than a purely neural one. For example, the conflict that triggers repression must come out as a conflict between states because they carry content that creates a conflict (e.g. “I want to have sex with my best friend’s partner,” “People who want to have sex with their best friend’s partner are bad people,” and “I do not want to have the desire to have sex with my best friend’s partner”, “I do not want to be a bad friend”). Also, the conflict must be unpleasant to the subject, which is a further psychological state. Finally, the repressed must be such that it at least potentially could become conscious. If repression were framed in purely neural vocabulary like, say, edge detection in early visual cortical area V1, the whole enterprise of psychoanalytic therapy would not make sense (as edge detection in V1 could never become conscious). Providing a psychological model means to provide a model that is framed in the vocabulary of psychology rather than in the terminology of neurobiology. The vocabulary of psychology is essentially mental vocabulary involving intentionality, semantic content, or phenomenology.

Third, the model must be mechanistic in the sense that it must identify causal steps of repression in such a way that they can in principle be mapped onto neural (or bodily) realizers. Repression is a real phenomenon only if there is a neural mechanismFootnote3 that constitutes it. This view is in line with Freud’s own view according to which the psyche is a biological phenomenon realized in the brain (Freud, Citation1954). Also, it is an assumption shared by repression-critics, such as Uleman, and it is especially the neural mechanism with regard to which they argue that there is no empirical evidence. Scientifically-minded philosophers agree that psychological phenomena supervene on neural or at least purely physical phenomena. Furthermore, by talking about a “mechanistic” model I want to highlight that the model is supposed to explain how repression works rather than enabling predictions, allowing for generalizations, providing unification, or the like. Finally, it need only be a how-possibly model (rather than a how-actually model, see Craver (Citation2007)) as its empirical validation is only the second step. The empirical validation can take two forms: a model can be validated by showing that the different steps it postulates indeed map onto causal components of a real mechanism; or a model can be validated by showing that it captures the features of real-world cases of the phenomenon that is modeled. A how-possibly model provides the starting point for the empirical search for evidence for or against repression. How-possibly models provide descriptions of how a mechanism might look like given certain theoretical assumptions. To show that the how-possibly model indeed is a how-actually model one must do the necessary empirical research. The goal of the paper is only to provide a how-possibly model – to what degree it may also be a how-actually model is left open and needs to be addressed by future research.

Fourth, a successful model of repression should be compatible with contemporary science. This implies that it should not invoke concepts such as psychic energies or oedipal drives that are foreign to or at least highly controversial in contemporary scientific psychology. This does not imply that these concepts are necessarily non-scientific. It may turn out that psychologists will rehabilitate, say, the notion of an oedipal complex (Solms, Citation2021) as part of their best psychological theories. However, for a model of repression to be applicable in contemporary research as it is now it should not depend on concepts whose scientific status is controversial and for which it is unclear whether hypotheses can be derived that are empirically testable.

Fifth and finally, in order to be sure that the model is indeed a model of repression, it needs to provide the resources for distinguishing repression from suppression. Repression and suppression are both processes involving a “subject removing something from awareness” (Boag, Citation2010, p. 173). The difference is that repression is understood as an unconscious and non-deliberative act, whereas suppression is taken to be conscious and deliberate (Boag, Citation2010, p. 167). As explained in the previous section, in repression the target as well as the process itself are prevented from becoming conscious. In suppression, the target becomes unconscious (i.e. there is an unconscious product), while the process itself remains conscious. An account of repression must clarify how repression differs from its conscious counterpart suppression. Note that the distinction between repression and suppression remains controversial (see, e.g. Erdelyi (Citation2006) and Boag (Citation2010) for a criticism of this distinction). Here, I will treat the distinction as a conceptual one: repression is defined as an unconscious process, while suppression is defined as a conscious process. This is compatible with the idea that the process of repression might gradually turn into a process of suppression, and vice versa, in real cases, or that as a matter of fact or of necessity, each process of repression starts with suppression.

This list summarizes the criteria of adequacy. A successfully model of repression should …

… account for the surface description.

… be a psychological model.

… be a mechanistic model.

… be compatible with contemporary science.

… make sense of repression vs. suppression.

Models of repression: the higher-order model & the separation model

Two types of models of repression are prominent in the literature – both of which can be traced back to Freud (Boag, Citation2012, p. 193; Hart, Citation1982, p. 180). According to the first type, which I call higher-order models, repression consists in the lack or prevention of some kind of higher-order mental state or awareness of a first-order mental state. The first-order mental state is thereby repressed, i.e. rendered unconscious as the specific sort of higher-order state or awareness is taken to be necessary for consciousness. In one version of this type of model the higher-order mental state is a higher-order knowledge state (Boag, Citation2012; Hart, Citation1982; McGinn, Citation1979): repression is a process that leads to a situation where the subject does not know that she knows a certain conflict-inducing content. According to another version of this model, repression results in the lack of attention of the first-order mental state. This is usually referred to as “selective inattention” (Schechner, Citation2010). Others combine both versions of this models: the lack of higher-order knowledge about the first-order mental state is due to a lack of attention to the first-order mental state (Boag, Citation2012).

According to the second type of model, which I will call separation models, repression consists of the separation of an affective state from its semantic categorization or representation (Billon, Citation2011; Freud, Citation1974, pp. 3000–3003; Hart, Citation1982). The affective state is not conscious as a particular affective state. In the philosopher Fred Dretske’s (Citation1993) words: the subject is thing aware but not fact aware of the affective state – she is aware of the affective state but she is not aware of the fact that she is aware of it. Consequently, it cannot be reported or used for rational control. Billon (Citation2011) describes this mode of unconsciousness, based on Block’s famous distinction, as one in which an affective state is phenomenally conscious (p-conscious) but not access conscious (a-conscious). Mental states that are felt are p-conscious; mental states that can be reported and that can be used in deliberate thinking are a-conscious. One example Billon uses to illustrate the idea is that of a woman who represses her fear of dying from cancer (Billon, Citation2011, p. 17). She experiences an intense fear of dying induced by the diagnosis. “This fear would push her into (…) considering her fear of dying as something else, maybe as an indeterminate anxiety, or even as a mere bodily phenomenon” (ibid.). Thus, the fear of dying is repressed by separating its affective aspect from its content (its intentional object) by miscategorizing the former.

Both models provide an analysis of the “unconscious product” (see previous section), i.e. they tell us in which sense the repressed state is unconscious. However, both models leave open how the unconscious product is produced. While selective inattention gives us a first hint as to how repression works, it leaves the details unspecified, and it is unclear how it avoids the following paradoxical situation: mental states that are to be repressed, i.e. that are to be the target of selective inattention, are mental states that create inner conflicts. Mental states do create inner conflict because of their contents. For the subject not to pay attention to a conflict-inducing mental state, she must know that a particular mental state is conflict-inducing. Thus, she must know that a mental state has a certain content. Thus, she must have higher-order awareness and knowledge of that mental state. Hence, to selectively not attend to the relevant mental state, she must attend to that mental state. This is, prima facie, a paradoxical situation. Furthermore, it remains unclear in which sense selective inattention is an unconscious process rather than a fully conscious action performed by the subject.

Separation models as such do not come with a specification of how repression works. However, Billon adds a further idea to his version of the separation model. He argues that the repressed mental state is impulsively miscategorized. The impulsive miscategorization is triggered by a hot emotional state such as the fear of death. This idea is compelling as impulsive actions are accepted by psychologists (Frijda et al., Citation2014) and they provide an intermediary between fully automatic movements and full-blown deliberative actions. Impulsive actions are automatic as they are reactions to affective triggers rather than due to conscious decisions. Still, impulsive actions are goal-directed and purposeful as they have the function of changing the subject’s unpleasant experiential state to a more pleasant one. Thus, Billon’s idea of repression as an impulsive act provides a convincing analysis of how repression is an unconscious but still a goal-directed process. According to Billon, due to the impulsive act, the hot emotional state while still being felt becomes a-unconscious, and thus, repressed.

Billon’s view of how repression might work is clearly not paradoxical and provides a causal analysis: a hot affective state triggers an impulsive miscategorization of a mental state. Still, there are two problems: first, there is no inner conflict. What triggers repression, according to this model, is a hot affective state, such as strong fear. This fear alone is sufficient to trigger the impulsive act. It need not create any conflict with other mental states, nor does the content play any role in the triggering of repression. Second, it is unclear whether the miscategorization is an effect of the impulsive act or whether the impulsive act is the miscategorization. In both cases, it is unclear either how the impulsive act leads to miscategorization, or why the impulsive act is one of miscategorization rather than something else.

The core idea of my proposal is to combine the central ideas of both types of models, i.e. of higher-order models as well as separation models and Billon’s idea that repression is an impulsive action.

A stepwise mechanistic model of repression

In the stepwise mechanistic model I develop in this section, the hybrid model of repression combines the core insights of the higher-order models and the separation models. According to the hybrid model, repression proceeds in six steps:

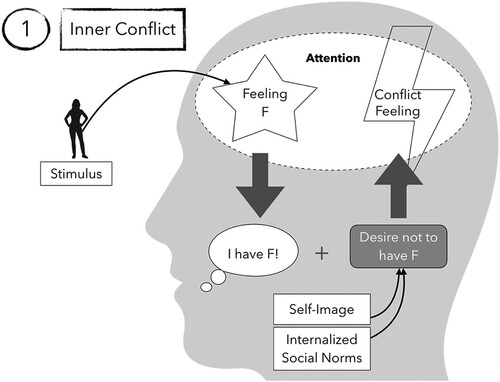

First (see ), an inner conflict arises between a feeling F and the desire not to have F. The feeling F – the “conflict-inducing feeling” – is triggered by an external stimulus that attracts the subject’s attention. Consequently, the subject has thoughts about F in which F is categorized as F. The desire not to have F is a conscious and reportable consequence of the subject’s internalized social norms, and/or her self-image (for a discussion of internalization see, e.g. (Kelly, Citation2020)). The inner conflict, thus, consists in the violation of the desire not to have F. This violation is felt as a conflict feeling, such as shame or guilt.

Figure 1. First step of repression: A stimulus induces a feeling F that attracts attention and therefore causes occurrent thoughts that categorize the feeling correctly. This categorization leads to the detection of a violation of a desire – a desire not to have that feeling F which is a consequence of the self-image and the internalized social norms. The violation of the desire induces a conflict feeling that again attracts attention. Consequently, the subject feels, for example, shame or guilt.

To use our example from Section 2: seeing or thinking about your best friend’s partner induces feelings of sexual arousal. These feelings will (at least at first) attract attention and you will note that you have sexual feelings for your best friend’s partner (under that or a sufficiently similar description). For example, you will have thoughts like “I want to see him!” or you might imagine kissing him. Since you consider yourself a good friend and you believe that good friends do not have sexual feelings for their best friends’ partners, you have the desire not to have these thoughts and imaginations. The desire and the induced sexual arousal are in conflict as the induced sexual feelings violate the desire to be a good friend. You feel shame or guilt for having the sexual feelings.

Note that the conflict-inducing feeling is conscious along three dimensions: it is p-conscious, it attracts attention, and it is correctly categorized. However, the conflict feeling is only conscious according to two dimensions: it is p-conscious, and it attracts attention. The conflict feeling is not conscious in the sense of being categorized correctly (thus, according to Billon’s interpretation of Block’s distinction, it is not a-conscious). That is, the conflict feeling is not categorized as shame or guilt as this would require more reflections by the subject to detect that what one is feeling is indeed shame or guilt rather than something else. The subject will not reflect upon the conflict feeling and, thus, does not detect its being induced by the violation of a desire that is important to her self-image. The reason is that the conflict feeling, due to its strong negative valence, will immediately, or rather impulsively, trigger the second step.Footnote4

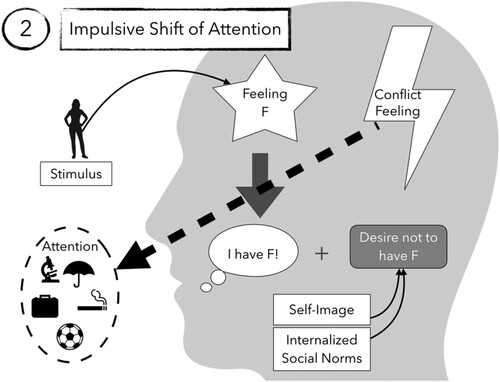

Second (see ), the negative conflict feeling triggers an impulsive shift of attention such that the subject will no longer pay attention to her feelings (thereby, I combine the core idea of selective inattention with Billon’s idea of repression as an impulsive act). Impulsive shifts of attention are attention shifts that are triggered by affective states and that have the purpose of improving the experiential state of the subject; they are automatic rather than deliberate (see previous section). After the impulsive attention shift, the subject will focus on external objects or activities. For example, the shame she feels due to her sexual feelings towards her best friend’s partner induces the impulsive shift towards, for example, her work and thoughts like “I have to finish my project!” whenever the conflict feeling is induced. Hence, the process of repression itself is made sense of in terms of an impulsive, non-deliberative, act that is a shift of attention away from a conflict-inducing feeling.

Figure 2. Second step of repression: The conflict feeling, due to its negative valence, triggers an impulsive shift of attention, e.g. towards external things. Thereby, the attention is moved away from the subject’s feelings.

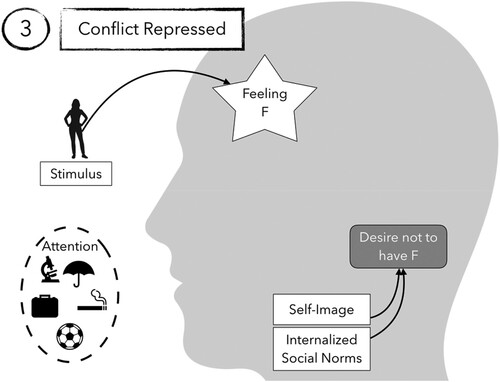

Third (see ), the subject does not pay attention to her internal states anymore and, thus, does not pay attention to the conflict-inducing feeling F. In other words, F is repressed in the sense of the higher-order model of repression: there is no higher-order awareness or knowledge of F anymore. This, again, leads to a prevention of the conflict becoming conscious: the subject has no occurrent thoughts about F anymore, which is why the conflict, i.e. the violation of the desire not to have F is no longer detected. Hence, the conflict feeling is not induced anymore. For example, because you are now immersed in your work, you will not pay attention to your feelings towards your best friend’s partner. Hence, you will not think about them anymore. Therefore, you do not form any occurrent thoughts that may allow you to detect the violation of your desire not to have sexual feelings for your best friend’s partner. Therefore, the conflict feeling (the shame or guilt) is not induced anymore. The conflict is repressed.

Figure 3. As a consequence of the impulsive shift of attention, the feeling F does not induce any occurrent thoughts anymore as the subject does not attend to it anymore. Therefore, the violation of the desire not to have F is not noticed anymore. Consequently, the conflict feeling is not induced anymore. The conflict-inducing feeling F as well as the conflict are repressed.

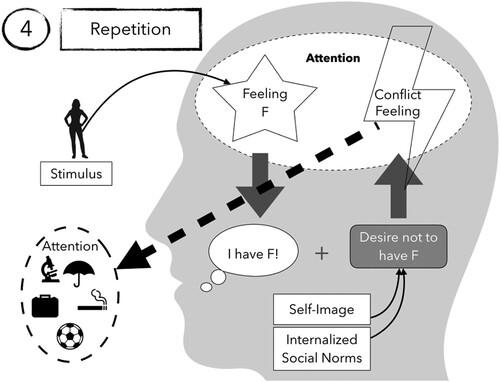

Fourth (see ), the steps 1–3 will be repeated multiple times given that the subject is confronted with the relevant stimulus more often (as a real encounter or as an encounter in thought/imagination). In our example, since you see your best friend often, you will also see the partner from time to time. Also, seeing your friend might trigger thoughts about her partner. Consequently, the conflict-inducing feeling F, the occurrent thoughts, the conflict, the conflict feeling, and the impulsive shift of attention will be induced again and again.

Figure 4. As the subject encounters the stimulus frequently, the steps 1, 2, and 3 are repeated multiple times.

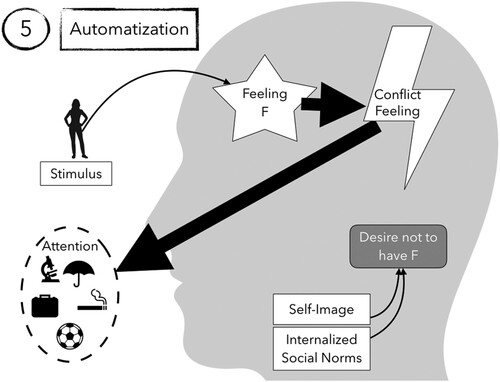

Fifth (see ), as a consequence of the repetition, at some point automatization sets in (similar to the formation of a habit, skill, or a conditioned behavior): due to the repetition of the sequence “F – > conflict – > attention shift” F will at some point automatically trigger the conflict feeling, which will automatically trigger the impulsive shift of attention – without the occurrence of any thoughts and without paying attention to any of these feelings. In our example: after a while, the subject will automatically direct her attention outwards and neglect her feelings when seeing or thinking about her best friend’s partner. While she may in principle be able to unlearn this behavior, it may become rather difficult (as it is the case for habits as well).

Figure 5. Due to the repetition, the shift of attention becomes automatized. Now, the presence of feeling F will automatically trigger the conflict feeling which will automatically trigger the shift of attention. Neither attention to the feeling F nor the occurrence of thoughts that categorize the feeling as F are required anymore.

This idea of automatization as a step in the hybrid model captures an idea that is central to Mark Solms’s view about repression: “The repressed (…) is illegitimately (or prematurely) automatized” (Solms, Citation2018, p. 9). Solms argues that standard unconscious cognitive processes, in contrast to repressed unconscious states and processes, are legitimately automatized because they work so well. In Solms’s account, in contrast to the hybrid model, what is automatized are predictions (in the sense of Friston’s predictive brain hypothesis) that aim at regulating affective states but are not successful in doing so. The predictions become non-declarative and procedural and, thus, unconscious. In the hybrid model, what becomes unconscious are feelings (the feeling F and the conflict feeling). In accordance with Solms’s views, these feelings are still p-conscious (as they are still felt) (see e.g. Smith and Solms (Citation2018)). Still, the feelings become a-unconscious because the subject can no longer pay attention to them and categorize them correctly as feelings of a certain type. Thus, one crucial difference between the hybrid model and Solms’s model is that proceduralization/automatization in Solms’s view is the mode in which repression leads to unconscious products: repression consists in the automatization of certain predictions. In the hybrid model, in contrast, proceduralization/automatization is the mode in which the process of repression is unconscious: the product is unconscious in the sense of not getting attention and not being categorized correctly due to automatization.

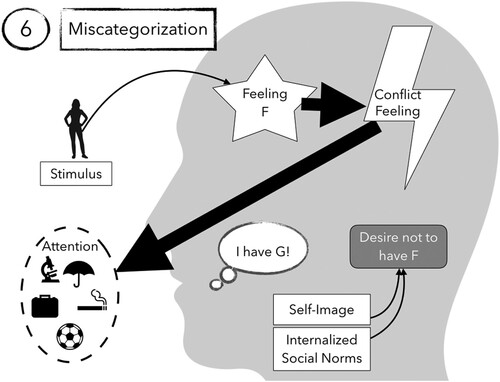

Sixth (see ), due to the automatization, the subject cannot focus her attention to the conflict-inducing feeling F and the conflict feeling anymore. Consequently, they are likely to be miscategorized (along the lines of Billon’s version of the separation model of repression; see Section 3). For example, the person in our example might still be aware of weird feelings when seeing or thinking about her best friend’s partner. Or someone might ask her why she, for example, always changes the topic when her best friend wants to talk about her relationship problems. However, due to the constant attention-shifts away from the feeling F she will be unable to pay attention and reflect on her feelings. She is, then, likely to come up with wrong explanations for her weird feelings and is likely to miscategorize it accordingly. The explanations she will come up with are likely to be compatible with her self-image and the social norms she has internalized as the explanations result from reflections that ignore the real nature of feeling F.

Figure 6. Since the subject does no longer pay attention to feeling F and since the shift of attention occurs each time F is induced, F is likely to be miscategorized by the subject. The subject is, thus, disposed to categorize F as something else, say G, in a way that does not conflict with her self-image and the internalized social norms.

As a result, the feeling F as well as the conflict feeling are still in existence. However, they are unconscious in the sense of the higher-order model of repression as well as in the sense of the separation model or repression: while both are still p-conscious, they are not contents of higher-order knowledge states and they do not get any attention. This is due to an impulsive, i.e. unconscious, shift of attention. The latter is a combination of the ideas regarding the process of repression that can be found in higher-order models (“selective inattention”) as well as in Billon’s version of the separation model (impulsive action). Furthermore, the subject is likely to miscategorize her feelings in a way that is compatible with her self-image and the internalized social norms (which is the core idea of Billion’s version of the separation model of repression).

The hybrid model accounts for all criteria of adequacy and, thus, avoids the problems of the pure higher-order models and separation models, as I will now summarize.

It accounts for the surface description. As a reminder, the surface description derived in Section 2 was formulated as: Repression is an unconscious, goal-directed, non-deliberative, and selective act triggered by an inner conflict, and by which the subject protects herself from the inner conflict by rendering conflict-inducing mental states unconscious without deleting them. This surface description is addressed by the model as follows:

The trigger of repression is an inner conflict: According to the hybrid model, repression is triggered by an inner conflict (see ). This conflict arises between a feeling that is categorized as a certain feeling F, and the desire not to have F. The desire is a consequence of the self-image and/or the internalized social norms. The conflict itself is depicted as the violation of a desire, where this violation induces negative feelings (the “conflict-feeling”) such as shame or guilt.

Repression is an unconscious but goal-directed process: The process of repression is analyzed as an impulsive shift of attention triggered by the inner conflict. As an impulsive act, it is not deliberative and thus is not a consciously performed action. Furthermore, as an impulsive act, it is nevertheless a goal-directed behavior of the subject (with the goal of rendering the current state more pleasant).

Repression selects some mental states to become unconscious: only feelings that induce inner conflicts are repressed. Negative feelings as such (e.g. pains) do not induce repression as long as they do not create a conflict with the subject’s self-image or her internalized social norms.

The products of repression are unconscious mental states: The mental states are feelings (the conflict inducing feeling F as well as the conflict feeling) that are unconscious in the sense of the higher-order model and the separation model.

Although the repressed is unconscious it remains in existence: The conflict-inducing feeling as well as the conflict-feeling (given the stimulus is present and induces the conflict-inducing feeling) are still present and still felt and thus, at least in principle, might still influence the subject’s thoughts and behaviors. Due to the automatization the feelings are likely to be miscategorized. In a nutshell: the model accounts for all five features of the surface description. The hybrid model avoids the paradoxical situation in which a subject needs to be aware of the repressed while at the same time must not be aware of it. Rather, the subject is aware of the conflict-inducing feeling as well as the conflict feeling at some time t1 but she is not aware of the feelings at a later time t2.

It is a psychological model. The hybrid model is a psychological model as it describes repression in purely psychological vocabulary. It is formulated in terms of concepts such as “feeling,” “desire,” “attention,” “impulsivity,” “conceptual categorization,” “automatization”.

It is a mechanistic model. The hybrid model does not only explain in which sense repressed states are unconscious. It also provides an explanation of how the process of repression works, i.e. the process that starts with a conflict and ends with a dissolution of the conflict by rendering a mental state unconscious. Furthermore, all steps of repression can in principle be mapped onto a neuronal or otherwise physical process. The steps that the model postulates describe behaviors that can be found in adult humans. For example, negative feelings are known to be potential triggers of impulsive actions (Frijda et al., Citation2014). Repression itself is described as an impulsive shift of attention triggered by a conflict-feeling. There are many examples of cases where we impulsively shift our attention to avoid negative stimuli such as when we see something disgusting or when we start to make strange noises when we think of something embarrassing.Footnote5 That there is a connection between re-directing attention and repression is accepted by many neuropsychoanalysts (Bazan, Citation2017; see, e.g. Diamond et al., Citation2006; Erdelyi, Citation2006) and there is plenty of evidence that repressing subjects refrain from paying attention to conflict-inducing stimuli. However, the exact connection remains unclear. The hybrid model offers a testable hypothesis regarding the role that attention might play in repression.

A core assumption of the hybrid model is that impulsive attention shifts can be automatized. That attentional processes can be automatized seems to be uncontroversial (e.g. during reading attention is directed automatically (Apel et al., Citation2012)). The hybrid model postulates that repression leads to a direct, automatic connection between the feeling that induces the conflict (feeling F) and the attention shift. To my knowledge, there is no empirical evidence on whether this can actually happen due to the fact that it has not been empirically investigated yet.

It is compatible with contemporary science. The hybrid model does not involve any scientifically controversial claims, but uses only concepts that are already accepted in contemporary psychology.

It makes sense of repression vs. suppression. Suppression is studied, e.g. with help of the think/no-think paradigm (Anderson & Green, Citation2001; Waldhauser et al., Citation2012). In studies where this paradigm is used, subjects learn a list of pairs of words. Then, they are presented with only one of the words of these pairs together with an indication of whether they are supposed to think of the second word or not. It could be shown that the words in the “no-think condition” are significantly more often forgotten than the words in the “think condition” and those that were learned but not part of the “think/no-think” phase. In these experiments, subjects are fully aware of the fact that they are not paying attention to the target word, and they do so intentionally – they have consciously formed the intention to participate in the experiment, follow the instructions, and to try not to think of the target word.

If repression is what is described by the hybrid model, how does repression differ from suppression? As explained in Section 2, suppression is the conscious counterpart of repression. They both have in common that they lead to an a-unconscious product. They differ in that, according to the hybrid model, repression is an automatic process while suppression is a deliberative process. In other words: in suppression subjects intentionally ignore contents; in repression they automatically neglect contents. The result of suppression as well as repression are mental states that do not receive attention and are, thus, likely to be miscategorized.

A further benefit of the hybrid model is that it can in principle account for the idea that an undoing of repression is an important step in psychotherapy to cure suffering. According to the hybrid model, the undoing of repression consists in learning to re-direct attention to the conflict feeling and learning to categorize it correctly. This, then, allows to find out where the conflict feeling comes from, i.e. identifying and categorizing the feeling F that creates the conflict. For example, a patient may suffer from repressed guilt. Due to the repression, she is not aware of the fact that it is guilt that she is suffering from. Still, she feels the guilt as an affective state (that is p-conscious but a-unconscious). Therapy might help her to learn to re-direct her attention to her unpleasant affective state (undo the automatization) and to learn to identify it as guilt. This may help her to see and accept where the guilt comes from and to find a different way to cope with this source other than repressing it.

Finally, a further benefit of the hybrid model is that it can make sense of the idea, widely shared among psychoanalysts, that by repressing contents their influence on the repressing person may become even stronger – at least if we add a few plausible assumptions. First, it is plausible to assume that if I am a-conscious of, say, my guilt I am able to and plausibly will consider it in my reasoning, planning and acting. For example, if I know that I feel guilty because I have sexual fantasies about by best friend’s partner, I can deal with this rationally: I can talk to my friend about it, I can intentionally avoid spending time with him, I can tell myself that this is not so bad to have these feelings as my best friend’s partner is obviously attractive and it is normal to feel attracted to people like him, I can actively forgive myself for having feelings that I do not actively produce, etc. When I repress this guilt, however, I cannot deal with it in rational/helpful ways. It will influence my behavior unconsciously which might worsen the situation and increase the guilt. E.g. due to the repression, my behavior towards my best friend may become more and more defensive without me knowing why this is even the case, which makes me feel even more guilty.

We started from the observation that the notion of repression is used even outside of psychoanalysis – despite what some psychologists claim. As presented in the introduction, some neuroscientists, psychologists and philosophers suggest that repression can (or cannot) explain phenomena such as explanations of memory distortions, the correlation between repressive personality style and illness, self-deception, depression as a reaction to awareness of death, and implicit attitudes. If repression is adequately modeled by the hybrid model, are these researchers right in that repression can(not) explain these phenomena? I do not have the space here to go into detail for each of the examples. I simply will list some remarks that point at next steps that one would have to take to settle the question.

Memory distortions: Axmacher et al. (Citation2010) argue that a certain type of memory distortion can be explained by repression. In experiments using free association subjects first freely associated words with other words that were presented by the experimenter. Then, they had to try to recall the words that they freely associated. It could be shown that subjects had impaired memory for words if these words were connected to an inner conflict. The hybrid model predicts that people who repress will automatically direct their attention away from stimuli that induce the feeling F (the one that creates the conflict). Thus, if they associate a word that is connected to the inner conflict, this will trigger the automatic attention shift. This plausibly leads to an interference with storing the word in memory. Furthermore, recall of the word will be difficult as well as attention is automatically shifted.

Correlation between repressive personality style and illness: As already explained above, the hybrid model predicts that subjects who repress are still p-conscious of the feeling that induces the conflict as well as of the conflict feeling (e.g. the guilt). The constant presence of negative feelings induces stress to the body, which increases the risk of illness.

Self-deception: According to philosophers, a standard case of self-deception consists in a subject coming up with a false belief due to the fact that she treats relevant evidence in a biased way while this evidence actually would tell her that her belief is false (Mele, Citation2001). The hybrid model predicts that a repressing person will automatically direct their attention away from any stimulus that is connected to the inner conflict. This implies that the repressing person will not pay attention to any sorts of evidence connected to the conflict, neither negative nor positive evidence. Thus, the presence of the inner conflict and the automated attention shift may explain the standard self-deception case.

Depression as a reaction to awareness of death: According to Ramachandran (Citation1996), depression is produced by the breakdown of the repression of the awareness of death. If it is true that non-depressed people are not depressed because they repress thinking about death, the hybrid model would predict that healthy people at least once had an encounter were they were fully aware of their own death which triggered the impulsive and then automatized attention shift. Depressed people, according to the hybrid model, would either have failed to have this first encounter that triggered the impulsive shift, or they could not automatize it, or the automatization for some reason broke down.

Implicit attitudes: People tend to not be aware of their implicit attitudes (i.e. attitudes measured by means of implicit methods) – especially not if they concern socially sensitive contents (such as racist or sexist attitudes). These kinds of implicit attitudes are called “implicit bias” in social psychology (Banaji et al., Citation2015). As Goedderz and Hahn (Citation2022) could show, people are usually not aware of their implicit biases because they do not pay attention to them. According to the hybrid model, a cause of this lack of attention could be the fact that people repress their implicit biases, and thus, automatically direct their attention away from them.

Conclusion

The hybrid model of repression combines the core ideas of two prominent models of repression, which I called higher-order models and separation models: it keeps the insight from the higher-order models that unconsciousness involves the lack of a higher-order awareness due to selective inattention. It keeps the insights from separation models that repression consist in an impulsive act that is triggered by a hot affective state. In contrast to Billon’s version of the separation model, according to the hybrid model, the repressive act is triggered by an inner conflict: the violation of the desire not to have a certain feeling F leads to a conflict feeling such as shame or guilt. According to the hybrid model, it is this latter hot affective state that triggers the impulsive shift of attention. Thereby, the hybrid model not only avoids the problems of the two other types of models, it can also be regarded as making good sense of their core ideas.

The hybrid model of repression can serve as the basis for empirical research. It accounts for all criteria of adequacy: it captures the surface description of repression, provides a mechanistic how-possibly account of how repression works in purely psychological terminology, is compatible with contemporary science, and provides the basis for distinguishing between repression and suppression. Thereby, the model promises to be fruitful for an analysis of memory distortions, the correlation between repressive personality style and illness, depression as a reaction to the awareness of death, implicit bias, self-deception, and it can be used by neuropsychoanalysts to study repression. Each step of the model is operationalizable and, thus, allows for empirical validation. Now, we can evaluate whether repression indeed is a real phenomenon, analyze existing empirical studies that claim to have found evidence for repression (such as Anderson (Citation2001)), and design new experiments.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the audiences of the workshop “Memory, Self, and the Unconscious Mind” held in Bochum in 2018, the annual congress of the International Neuropsychoanalysis Society in Mexico City in 2018, the workshop “The Self and its Realization” held in Boulder in 2018, and the colloquium at the Cognitive Science department of the university of Osnabrück, and to Bence Nanay and his group who I visited in 2018. I am especially grateful to Nikolai Axmacher, Bence Nanay, and Gerd Waldhauser for the helpful discussions of the topic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In what follows, I will use the term “mental state” as an umbrella term for any kind of mental entity in the mind of the subject such as beliefs, the process of thinking, affective states, perceptions, etc.

2 Teleological explanations are often rejected as they seem to require backwards causation by end-states (the goal) (Boag, Citation2012, p. 107). However, the reduction of teleological concepts to causal concepts is widely accepted in philosophy of science and “teleonaturalism” is now widely accepted (Allen & Neal, Citation2020). For this reason, I do not agree with Boag (Citation2012) that repression should not be characterized in terms of teleological concepts (see also Hart (Citation1982, p. 180)).

3 Note that the mechanism for repression might not be purely neural but may involve bodily factors, or even elements of the physical or social environment. The question of how far psychological mechanisms may be extended in that sense is subject of rather recent philosophical and psychological debates (de Haan, Citation2019; Leuzinger-Bohleber, Citation2018). The mechanistic account is prima facie compatible with this idea (Kaplan, Citation2012; Krickel, Citation2020).

4 Note that the claim is not that these steps necessarily follow each other. Some people may reflect on their inner conflict and realize that they feel shame or guilt, and based on this insight, find a different way to cope with the conflict. Thus, for repression to occur certain background conditions must be in place. These background conditions plausibly involve character traits, absence of training through therapy, intelligence, etc. Further aspects that may influence the process are strength of the conflict-inducing feeling and relevance to the self-image. These details must be worked out in detail by future research. The goal here is to propose a general outline of a how-possibly mechanism of repression.

5 That this seems to be a real phenomenon can be seen from a discussion on the online blog reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/cogsci/comments/8p8pz/when_i_remember_something_embarrassing_from_my/ [accessed on March 1st, 2024].

References

- Allen, C., & Neal, J. (2020). Teleological notions in biology. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/teleology-biology/.

- Anderson, M. C. (2001). Active forgetting: Evidence for functional inhibition as a source of memory failure. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 4(2), 185–210. https://doi.org/10.1300/J146v04n02_09

- Anderson, M. C., & Green, C. (2001). Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control. Nature, 410(6826), 366–369. https://doi.org/10.1038/35066572

- Apel, J. K., Henderson, J. M., & Ferreira, F. (2012). Targeting regressions: Do readers pay attention to the left? Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 19(6), 1108–1113. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0291-1

- Axmacher, N., Do Lam, A., Kessler, H., & Fell, J. (2010). Natural memory beyond the storage model: Repression, trauma, and the construction of a personal past. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4(November), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2010.00211

- Banaji, M. R., Bhaskar, R., & Brownstein, M. (2015). When bias is implicit, how might we think about repairing harm? Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.08.017

- Bazan, A. (2013). Repression as the condition for consciousness. Neuropsychoanalysis, 15(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2013.10773712

- Bazan, A. (2017). Alpha synchronization as a brain model for unconscious defense: An overview of the work of Howard Shevrin and his team. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 98(5), 1443–1473. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-8315.12629

- Berlin, H. A. (2011). The neural basis of the dynamic unconscious. Neuropsychoanalysis, 13(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2011.10773654

- Billon, A. (2011). Have we vindicated the motivational unconscious yet? A conceptual review. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(SEP), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00224

- Boag, S. (2006). Can repression become a conscious process? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29(5), 513–514. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X06239116

- Boag, S. (2007). Realism, self-deception and the logical paradox of repression. Theory & Psychology, 17(3), 421–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354307077290

- Boag, S. (2010). Repression, suppression, and conscious awareness. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019416

- Boag, S. (2012). Freudian repression, the unconscious, and the dynamics of inhibition. Karnac.

- Boag, S. (2017). Metapsychology and the foundations of psychoanalysis. Attachment, neuropsychoanalysis and integration. Routledge.

- Cohen, L. J. (1995). Essay on belief and acceptance. Oxford University Press UK.

- Craver, C. F. (2007). Explaining the brain: Mechanisms and the mosaic unity of neuroscience. Oxford University Press.

- de Haan, S. (2019). Enactive psychiatry. Cambridge University Press.

- Derakshan, N. (1999). Are repressors self-deceivers or other-deceivers? Cognition & Emotion, 13(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379348

- Diamond, L. M., Hicks, A. M., & Otter-Henderson, K. (2006). Physiological evidence for repressive coping among avoidantly attached adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23(2), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407506062470

- Dretske, F. (1993). Conscious experience. Mind, 102(406), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/102.406.263

- Erdelyi, M. H. (2006). The unified theory of repression. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29(5), 451–499. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X06009113

- Fotopoulou, A. (2013). Beyond the reward principle: Consciousness as precision seeking. Neuropsychoanalysis, 15(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2013.10773715

- Freud, S. (1954). Project for a scientific psychology. In M. Bonaparte, A. Freud, & E. Kris (Eds.), The origins of psycho-analysis: Letters to Wilhelm Fliess, drafts and notes: 1887–1902 (pp. 347–445). Basic Books. https://doi.org/10.1037/11538-013.

- Freud, S. (1974). The complete psychological works of sigmund freud (J. Strachey (ed.); Standard E). Hogarth Press.

- Frijda, N. H., Ridderinkhof, K. R., & Rietveld, E. (2014). Impulsive action: Emotional impulses and their control. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(June), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00518

- Furnham, A., Petrides, K. V., & Spencer-Bowdage, S. (2002). The effects of different types of social desirability on the identification of repressors. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(1), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00139-8

- Garssen, B. (2007). Repression: Finding our way in the maze of concepts. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(6), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9122-7

- Gawronski, B., Hofmann, W., & Wilbur, C. J. (2006). Are “implicit” attitudes unconscious? Consciousness and Cognition, 15(3), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2005.11.007

- Goedderz, A., & Hahn, A. (2022). Biases left unattended: People are surprised at racial bias feedback until they pay attention to their biased reactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102(July 2021), 104374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104374

- Grünbaum, A. (1984). The foundations of psychoanalysis - A philosophical critique. In Journal of chemical information and modeling (Vol. 53, Issue 9). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Hart, W. D. (1982). Models of repression. In R. Wollheim, & J. Hopkins (Eds.), Philosophical essays on Freud (pp. 180–202). Cambrdige University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511554636.

- Johnston, M. (1995). Self-deception and the nature of mind. In C. Macdonald (Ed.), Philosophy of psychology: Debates on psychological explanation (pp. 63–91). Blackwell.

- Kaplan, D. M. (2012). How to demarcate the boundaries of cognition. Biology and Philosophy, 27(4), 545–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-012-9308-4

- Kelly, D. (2020). Internalized norms and intrinsic motivations: Are normative motivations psychologically primitive? Emotion Researcher, 1(June), 36–45.

- Krickel, B. (2018). Are the states underlying implicit biases unconscious? – A neo-Freudian answer. Philosophical Psychology, 31(7), 1007–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2018.1470323

- Krickel, B. (2020). Extended cognition, the new mechanists’ mutual manipulability criterion, and the challenge of trivial extendedness. Mind & Language, 35(4), 539–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12262

- Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. (2018). Embodiment: A new key to the unconscious? In C. Charis & G. Panayiotou (Eds.), Somatoform and other psychosomatic disorders: A dialogue between contemporary psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy perspectives (pp. 121–142). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89360-0_7.

- Lynch, K. (2014). Self-deception and shifts of attention. Philosophical Explorations, 17(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13869795.2013.824109

- Maze, J. R., & Henry, R. M. (1996). Psychoanalysis, epistemology and intersubjectivity: Theories of Wilfred Bion. Theory & Psychology, 6(3), 401–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354396063004

- McGinn, C. (1979). Action and its explanation. In N. Bolton (Ed.), Philosophical problems in psychology (pp. 20–42). Methuen.

- Mele, A. R. (2001). Self-deception unmasked. Princeton University Press.

- Ramachandran, V. S. (1996). The evolutionary biology of self-deception, laughter, dreaming and depression: Some clues from anosognosia. Medical Hypotheses, 47(5), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9877(96)90215-7

- Sartre, J.-P. (1956). Being and nothingness. Philosophical Library.

- Schechner, R. (2010). Selective inattention. Performance Theory, 211–234. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203426630_chapter_6

- Smith, R., & Solms, M. (2018). Examination of the hypothesis that repression is premature automatization: A psychoanalytic case report and discussion. Neuropsychoanalysis, 20(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2018.1473045

- Solms, M. (2013). The conscious Id. Neuropsychoanalysis, 15(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2013.10773711

- Solms, M. (2018). The neurobiological underpinnings of psychoanalytic theory and therapy. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12(December), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00294

- Solms, M. (2021). A revision of Freud’s theory of the biological origin of the oedipus complex. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 90(4), 555–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332828.2021.1984153

- Ulemann, J. S. (2005). Introduction: Becoming aware of the new unconscious. In R. R. Hassin, J. S. Uleman, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The new unconscious (pp. 3–18). Oxford University Press.

- Waldhauser, G. T., Lindgren, M., & Johansson, M. (2012). Intentional suppression can lead to a reduction of memory strength: Behavioral and electrophysiological findings. Frontiers in Psychology, 3(OCT), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00401

- Wilson, T. D., Lindsey, S., & Schooler, T. Y. (2000). A model of dual attitudes. Psychological Review, 107(1), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.1.101