?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Can a politician cue national identity and fit? Given that Trump’s rhetoric often signaled the devaluation of certain groups, we examined this across three pre-registered studies . In Study1 (2017), targets of Trump’s rhetoric reported less social fit, greater social identity threat, and expected increased discrimination . In Study2 (2017), marginalized targets reported less fit and American identification as well as greater threat and discrimination when anticipating Trump(vs. Obama). Study3, conducted during the 2020 election, revealed that racialized participants felt greater fit and American identification after (vs. before) Biden’s victory , but effects of Trump’s presidency on expected discrimination had not reversed. These findings suggest that a divisive leader can induce feelings of devaluation, threat, and national detachment.

To what extent can the election of a particular political leader cue fit and national identity for their constituents? In the campaign leading up to the 2016 election, Donald Trump promised to “make America great again.” Although a significant proportion of Americans were enticed by this message, some of Trump’s talking points were widely viewed as devaluing certain groups such as women, members of minoritized ethnic groups, and members of the LGBTQ+ community (Huber, Citation2016). A number of qualitative studies suggest that Trump’s election was met with distress and fear of repercussion among these groups (Abreu et al., Citation2021; Albright & Hurd, Citation2020; Brown & Keller, Citation2018; Drabble et al., 2018b; Gonzalez et al., Citation2018; Veldhuis et al., Citation2018b, Citation2018a), suggesting that Trump’s election may have also impacted their feelings of fit within American society. Social psychological research has considered how cues in the environment signal a sense of fit (or lack thereof) to members of marginalized groups. Given the identity-based rhetoric that targeted women, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ+ community during Trump’s campaign, his election in 2016 and defeat in 2020 might have provided members of these groups with powerful cues to their fit within American society. In the present set of studies, we draw on and extend past literature to examine the degree to which the election of a president who apparently devalues one’s ingroup is linked to a lower sense of fit and identification within one’s country.

After his inauguration, Trump’s marginalizing rhetoric continued and was matched by explicit policies and executive actions that promoted or condoned discriminatory behaviors carried out by individuals and institutions (e.g., refusing to condemn white supremacists and proposing to end DACA – Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals). The unique historical nature of the present research is itself a novel and important aspect of this work. Importantly, the focus of the present research is not on Americans’ reactions to Trump’s actual actions and policies as the president of the United States. Rather, our focus is on people’s reaction to the democratic election of a populist leader and the ways in which his election served as a symbolic cue to marginalized groups’ immediate feelings of fit, identity, and threat. Simply put: what does it mean to me if my fellow Americans elected a person who devalues my social group? And does his later defeat then also restore feelings of fit and identification?

Belonging in social contexts

Having a sense of belonging within one’s community has been described as a basic human need (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Yet research shows that members of marginalized groups frequently experience belonging uncertainty – uncertainty over whether they fit in – in mainstream cultural contexts (Cohen & Garcia, Citation2008; Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018; Walton & Cohen, Citation2007). Related to belonging uncertainty is social identity threat, the feeling that one is at risk of being socially devalued on the basis of one’s group membership (Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, Citation2002). Importantly, even subtle contextual cues that bring identity threat to mind (e.g., everyday interactions with others, physical cues in the environment) can be detrimental to performance, health, and motivation (Cheryan et al., Citation2017; Hall, Schmader, Aday, & Croft, Citation2019; Major & Schmader, Citation2018; Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018; Spencer, Logel, & Davies, Citation2016). Over time, a sense of identity threat will erode the extent to which members of marginalized groups identify with contexts in which devaluation and threat occur (e.g., African Americans in post-secondary education contexts; Steele et al., Citation2002).

National identity can be construed, in part, as a sense of belonging among one’s compatriots. A sense of national identity is particularly important for binding individuals together in large and diverse societies (Hornsey & Hogg, Citation2000). Across many nations, however, marginalized groups (e.g., ethnic or religious minorities) tend to show weaker national identity than members of dominant groups in society (Staerkle, Sidanius, Green, & Molina, Citation2005). In the United States, for instance, European Americans and members of racialized groups alike tend to associate being American with being White, and see people of color as perpetually foreign and/or inferior (Cheryan & Monin, Citation2005; Devos & Banaji, Citation2005; Huynh et al., Citation2011; Zou & Cheryan, Citation2017). Accordingly, many Americans of color experience relatively low levels of national identification (Devos, Gavin, & Quintana, 2010) and feel excluded from mainstream society (Phinney, Cantu, & Kurtz, Citation1997).

To date, national identity, or lack thereof, has largely been studied as a stable characteristic of individuals who are members of different groups. In the current set of studies, however, we consider that one’s sense of fit and national identity can be influenced by powerful situational cues. Specifically, our interest is in whether: a) a sense of identity misfit is cued for members of particular groups in response to political events, like the inauguration of Donald Trump as president of the United States in 2017, and b) whether sense of fit can be restored by new political event, as when Trump was defeated in the 2020 election to Joseph Biden. Past psychological theory gives us a framework for identifying how and why Trump’s election and failed reelection bid might signal fit.

Three facets of fit to the environment

Environments can provide situational cues to different types of fit to one’s identity. The SAFE model (State Authenticity as Fit to Environment; Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018) specifies that such contextual fit can take on three distinct forms: (1) social fit, (2) self-concept fit, and (3) goal fit. A person will feel a sense of social fit to the degree that others in the environment seem to accept and validate them for who they truly are (e.g., a comedian whose friends appreciate her sense of humor). A person will feel a sense of self-concept fit to the degree that they perceive important, self-defining aspects of the self are a match to the environment (e.g., an avid nature-lover on a hike). A person will feel a sense of goal fit to the degree that motivational structures within the environment afford the goals they personally value and are motivated to pursue (e.g., an environmentally conscious employee whose office-policy encourages recycling). Each distinct form of fit is cued by features of the environment, and together (independently or in interaction) can contribute to an overall sense of state authenticity (the sense of being one’s true or genuine self; Aday and Schmader, Citation2019; Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018). Such state authenticity, in turn, promotes a tendency to approach and identify with contexts that promote fit and authenticity, and avoid those contexts that do not.

Marginalized groups are at risk of feeling a lack of fit in mainstream cultural contexts created for and by members of majority groups (Aday & Schmader, Citation2019). In line with the SAFE model, when marginalized groups feel a sense of social devaluation (i.e., threats to belonging), they experience a lack of social fit (Brown & Pinel, Citation2003; Hall et al., Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2019; Logel et al., Citation2009; Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, Citation2014). In contrast, when marginalized groups feel alienated because their own traits or interests are misaligned with the environment, they experience a lack of self-concept fit (Cook, Purdie-Vaughns, Garcia, & Cohen, Citation2012; Cheryan, Plaut, Davies, & Steele, 2009; Phillips, Stephens, & Townsend, 2016). Finally, when women or people of color feel a lack of fit because their own goals are misaligned with those afforded by the environment, they experience a lack of goal fit (Diekman, Brown, Johnston, & Clark, 2010; Diekman, Clark, Johnston, Brown, & Steinberg, 2011). In the present studies, we focused on the distinction between self-concept and social fit in response to the election (and failed reelection) of a political leader known to espouse and promote sexist and racist beliefs. Although we acknowledge that goal fit may also play a role in specific contexts and situations, it is not central to the present project given that citizens’ personal goals are less likely to be directly impacted by the outcome of a national election.

Fit in the political context

To date, most research on the lack of fit and belonging among marginalized groups has focused on contextual cues in academic and organizational settings. Here, we apply these ideas to the national political context. Although political party membership is an increasingly important part of American identity (Huddy, Citation2001; Huddy & Khatib, Citation2007), little is known about how expressed views from a political leader, or their election into or out of public office, may cue different types of national fit and belonging. One notable exception is research by Dai and colleagues (2021), demonstrating in a series of four studies that liberal-leaning White Americans disidentified with their American identity when reminded of their racial ingroup’s support for Trump’s presidency. This study did not, however, address how Trump’s election might have been even more threatening to members of groups that have been portrayed negatively by the leaders’ campaign for election.

More broadly, however, research suggest that leaders have an important effect on the social climate within their group. Leaders, like other high-status individuals, are uniquely influential in signaling the norms and beliefs of a group (Feldman, 1984), regardless of whether a leader’s status is achieved through dominance (i.e., status gained through force and intimidation) or prestige (i.e., status gained through respect and demonstrated expertise; Cheng et al., Citation2013). Importantly, accompanying status is influence, or the ability to modify others’ thoughts, behaviors, and feelings (Cheng et al., Citation2013; Hogg, 2010).

Research suggests that Trump’s election in 2016 normalized prejudice against the groups he targeted during this campaign. Specifically, Crandall and colleagues discovered that shortly after the election, compared to shortly before the election, Americans tended to express significantly greater prejudice against groups that Trump voiced bias against (e.g., Muslims), but not against other politically liberal groups that Trump had not targeted during his campaign (e.g., atheists; Crandall, Miller, White et al., Citation2018). Other research not only shows that people with stronger sexist and racist beliefs were more likely to vote for Trump in 2016 (Bock et al., Citation2017; Bracic et al., Citation2019; Saldaña et al., Citation2018; Vescio & Schermerhorn, Citation2021), but also that Trump’s presidency led to an increase in explicit expressions of prejudice against religious, ethnic, and sexual minorities, especially among Trump supporters (Crandall, Miller, White et al., Citation2018; Does et al., Citation2019; Georgeac et al., Citation2019; Monteith & Hildebrand, Citation2020; Ruisch & Ferguson, Citation2022).

Such changing norms toward expressing social prejudices could have real consequences for the daily lives of members of marginalized groups. Members of the LBGTQ+ community, for example, reported experiencing significantly more frequent discrimination in the days after (vs. before) Trump’s election (Drabble et al., Citation2018a; Garrison et al., Citation2018). Given the importance of political leaders in signaling social norms, the current research aimed to empirically examine how the initial election and, later, failed reelection of a leader who has campaigned on identity politics impacts those who feel targeted by his/her views. We primarily focus on the effects on individuals’ sense of social and/or self-concept fit, and national identity centrality (our pre-registered primary outcomes), but also examine downstream effects on social identity threat, and expectations of discrimination (as secondary outcomes).

We theorize that the democratic election of a leader who is perceived as dismissing minority interests is likely to signal to members of marginalized groups that they are not valued or accepted by other people in their society (i.e., lowering their sense of social fit). Some indirect evidence supports the premise that political events and elections can influence feelings of social fit. For example, because of a tendency to include political candidates in our own sense of self, a failed election bid can be experienced as a vicarious rejection to that person’s supporters (Claypool et al., Citation2020; Young et al., Citation2009). Such impacts to social belonging might be particularly enhanced for members of politically marginalized groups. After the historic supreme court ruling for marriage equality in 2015, for example, gay men reported increased feelings of social inclusion (Metheny & Stephenson, Citation2018).

This past work suggests that the election of a leader like Donald Trump might, in turn, erode feelings of social acceptance among groups targeted by his rhetoric. A sample of LGBTQ individuals reported more identity salience and discrimination after the election (Gonzalez et al., Citation2018), suggesting that concerns about fitting in socially could be heightened. While not directly addressing feelings of fit, qualitative studies further suggest that following the 2016 election, women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and Latinx youths (some of the groups most targeted by Trump’s election campaign rhetoric) perceived and feared lower acceptance in society (Brown & Keller, Citation2018; Daftary et al., Citation2020; Drabble et al., 2018b; Gonzalez et al., Citation2018; Veldhuis et al., Citation2018a). While these studies did not assess perceived social fit and threats to social belonging directly, this evidence provides the basis for our hypothesis that the election of a leader who devalues marginalized groups in society might lead to lower perceptions of social fit among members of these targeted groups.

To date, there is even less research that can speak to whether the election of a seemingly biased political leader also affects self-concept fit – the extent to which we perceive fit between our own characteristics and mainstream national culture. Political scholars have argued that the 2016 election contributed to increasing partisanship in the U.S. – a sense that voters of the other party are very different from oneself and political views are fundamentally irreconcilable (Abramowitz & McCoy, 2019). Perceiving such irreconcilable differences has important consequences; individuals who experience ideological misfit in environments that are perceived as not sharing their political preferences are more likely to leave such environments in search of communities that align with one’s own self-views (Motyl, Iyer, Oishi, Trawalter, & Nosek, 2014). Over time, such patterns can lead to mass geographical segregation on the basis of political identity (Bishop, 2009). The election of a leader that is seemingly biased against one’s ingroup might signal to members of groups targeted by those biases that they are very different from their fellow citizens, and that their own traits and values do not fit within the group’s mainstream culture (i.e., lowering their sense of self-concept fit). Over time, this might lead members of targeted groups to self-segregate more, exacerbating their feelings of exclusion.

When feelings of social and/or self-concept fit are decreased (or increased) in response to the election of a political leader, we might expect members of marginalized groups to disengage (or reengage) with their national identity. Although this idea has not been explicitly tested to date, there is suggestive evidence in the literature. First, a sense of self-concept fit with American society characterized by a focus on shared values has shown to protect national identity in members of marginalized groups (Citrin, Wong, & Duff, 2001). Thus, if an election lowers one’s sense of self-concept fit with mainstream America or enhances feelings of social rejection and devaluation (i.e., lower social fit), either could reduce American identification among members of marginalized groups. For example, immigrants who feel targeted by negative stereotypes and discrimination (i.e., a low sense of social fit) experience greater conflict between their ethnic and national identities (Benet-Martínez & Haritatos, Citation2005; Huynh et al., Citation2011). Such conflict might eventually translate into weakened identification with one’s national identity. In sum, existing evidence seems to suggest that one’s sense of fit to national culture and national identity are deeply intertwined.

Overview of current research

In three pre-registered studies, we tested the effects of Trump’s election in 2016 (Studies 1 and 2) and failed reelection in 2020 (Study 3) among those who felt their social ingroup was targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric – in our first two studies mostly women and members of the LGBTQ+ population (Studies 1 and 2), as well as nonwhite participants (Study 3). Studies 1 and 2 were conducted in January of 2017 (before and during the days of Trump’s inauguration), with samples of legal permanent US residents recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). For the purposes of these studies, as pre-registered, we excluded participants who indicated they strongly supported Trump in the election1. In Study 1 and 2, participants self-reported the extent to which they identified as members of a group that was negatively targeted by Trump’s campaign (those who felt targeted were predominantly women). Although we might expect these individuals to chronically feel a lower sense of fit and identification with America compared to those who fit the White male cultural default, experimental reminders of Trump’s election or upcoming presidency were expected to exacerbate these feelings. In Study 1, we subtly manipulated reminders of popular support for Trump (support vs. lack of support) before having participants complete measures of fit and American identity. In Study 2, participants were asked to complete measures of fit and American identity while reflecting on either the outgoing Obama presidency or the incoming Trump presidency. In Study 3, people of color recruited through targeted sampling were similarly asked to report their feelings of fit, identification, and threat, either in the days before the 2020 presidential election or just after Joseph Biden and Kamala Harris’ win over Trump was announced by major news outlets.

Across all three studies, we hypothesized that reminders of Trump’s election or failed reelection would lead to lower (failed reelection: higher) social fit and self-concept fit (primary outcomes) as well as increased (failed reelection: decreased) social identity threat and expectations of discrimination (secondary outcomes) – especially for those who felt their in-group had been targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric. In addition, we hypothesized that, specifically for those who reported feeling targeted, experimental effects on social and/or self-concept fit would predict ratings of national identification as an American. These studies were preregistered and are available on the OSF at https://osf.io/evjwy/?view_only=541800e59d9d42e3813f8712283d1cfb (Study 1), https://osf.io/2n82e/?view_only=8ac319b6fbe7448d86d5ab179b4c5ed1 (Study 2) and https://osf.io/9ayq2/?view_only=5cf35af581584c02843391d4a2cf777e (Study 3).

Study 1

Method

Participants

A final sample of 290 participants (114 men/174 women/2 “Other”) 2 were recruited from Mturk and completed the study for $1.50. On the Open Science Framework (OSF), we pre-registered our aim to recruit 400 participants for a usable sample of at least 236, allowing us to detect a large mediational relationship in the half of our sample that felt most targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric at 80% power (power analyses for mediation conducted according to guidelines by Fritz & Mackinnon, Citation2007). As pre-registered, we excluded 91 participants of the 381 who completed the survey for the following reasons: 3 were not legal or permanent residents of the U.S.; 10 failed attention checks; 21 who showed excessively fast reaction times suggesting inattention (more than 10% of responses below 300 ms on the implicit measure described in the supplementary online material; SOM)3; and 57 who indicated “I strongly supported Trump.” These last exclusions were preregistered to minimize the chance that findings were explained by high political support for Donald Trump rather than not being a target of his rhetoric. A continuous measure of political orientation was further included as a covariate in analyses for the same reason. Note, however, that evidence summarized in Tables S2 and S4 of the SOMC shows that conclusions were unchanged (and if anything became descriptively stronger) when Trump supporters were included in analyses. details the sample characteristics for Study 1 and Study 2, and reveals that our final sample was approximately 38 years old, slightly liberal leaning, and college-educated. In addition, our sample slightly overrepresented women and the majority of our sample identified as White. The most frequently cited reasons for feeling targeted by Trump were: a) being a woman, b) being part of a minoritized racial or ethnic group, and c) being part of the LGBTQ+ community.

Table 1. Summary of sample demographics in studies 1 and 2.

Procedure

Stu took place between January 11th and January 15th, 2017 (approximately two months after Trump was elected and one week before his inauguration as president). First, participants completed a demographic questionnaire (gender, ethnicity, political orientation, income, religiosity, and the extent to which they identified as a member of a targeted ethnic group; demographic data across Studies 1 and 2 are summarized in ). They were then randomly assigned to see one of two conditions designed to manipulate perceived popular support for Trump, both of which presented materials from real online sources (e.g., Politico.com, Twitter).

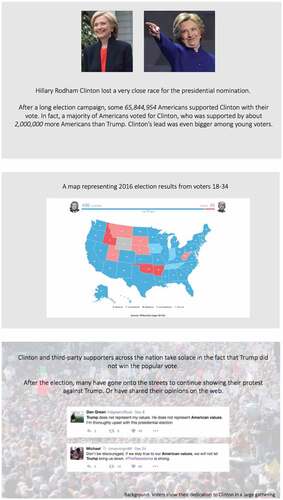

In the Low Support condition (n = 147), the information presented emphasized that Clinton won the popular vote (i.e., the majority of Americans did not support Trump) and included salient examples of Tweets that were unsupportive of Trump.

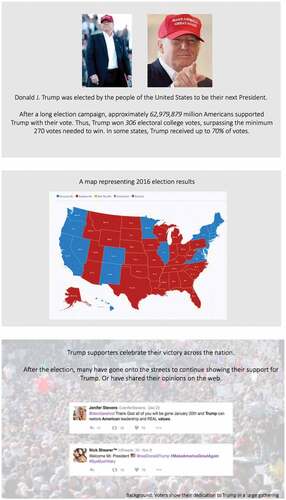

In the High Support condition (n = 143), the information presented emphasized that Trump won the democratic election and included salient examples of Tweets that were supportive of Trump. Images used in each manipulation can be found in Appendix 1. After this manipulation, participants completed measures in the order listed below.

Measures

Identity as a member of a targeted group (predictor)

In designing our initial study, we did not want to presume which groups would feel targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric. Thus, to assess the extent to which participants saw themselves as part of a group targeted by Trump, participants rated their agreement with one item (“In the lead up to the election, Trump and/or his campaign said, or did, things that implied negative stereotypes and prejudice towards a social group (e.g., ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexuality) that I am personally part of.”) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = Not at all true for me to 5 = Very true for me (with scale points in-between unlabeled). Participants were then asked to list one or more such groups in an open-ended response. As summarized in , the majority of those who felt targeted in our sample (as pre-registered, the half of our sample that scored at or above the median (Md = 4) on this feeling targeted measure)4, felt targeted for being female (n = 90, 64%), a person of color (n = 46, 33%), or a sexual minority (n = 26, 18%).

Table 2. Summary of Coded Responses for Ingroups Targeted by Campaign Rhetoric in Studies 1 and 2.

Manipulation check

To ensure our experimental manipulation of support for Trump was effective, participants estimated what percentage “of all Americans (whether they voted or not) fully and wholeheartedly support Donald Trump” on a scale ranging from 0 to 100%”.

Social and self-concept fit (primary outcomes)

Measures of fit were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = Not at all, 7 = Very much). Two items tapped into perceptions of social fit within American society, (r = .96, “To what extent do you feel that the average American would value YOU as a member of American society?”; “To what extent do you feel that the average American would appreciate YOU as a member of American society?”). Two additional items tapped into self-concept fit (r = .75, “How similar do you see yourself to the average American?”; “To what extent do your values match those of the average American?”). As hypothesized, a confirmatory factor analysis conducted in lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) revealed a two-factor model had good fit for these 4 items, CFI = .998, RMSEA = .082, and performed significantly better than a one-factor model collapsing across the two forms of fit, χ2 diff = 145.50, p < .001.

American identification

American identification was measured with the Identity Centrality subscale from the Collective Self-Esteem scale (CSE; Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992). Participants used a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) to rate their agreement with four items modified to assess American identification (α = .88, e.g., “Being American is an important reflection of who I am.”).5

Social identity threat

To assess current feelings of social identity threat, we modified a two-item measure of social identity threat used by Hall et al. (Citation2015; 2019). Participants responded to two items (r = .61, “I feel very aware of my race, gender, religion, or sexual orientation”; “I am concerned that, because of my race, gender, religion, or sexual orientation, my actions will influence the way other people interact with me”), using a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree). The two items were averaged to form a composite score as measure of social identity threat.

Expectations of discrimination

Participants reported the likelihood of personally experiencing overt (“How likely are you to experience overt (openly expressed, direct) discrimination based on a social group that you are part of (e.g., ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality)?”) and covert discrimination (“How likely are you to experience covert (hidden, indirect) discrimination … ?”) within the next month on a 7-point scale (1 = Quite unlikely, 7 = Extremely likely). The two items were strongly correlated (r = .86), and were therefore averaged to represent a measure of expected discrimination.

Demographic variables

We collected demographic variables to describe our sample, and to rule out third-variable explanations of any relationship between being a targeted group and feeling less American. The pre-registered control variables included political orientation, income, age, education, employment status (employed vs. unemployed), context of residence (rural vs. urban), and state of residence (red vs. blue based on the outcome of the presidential vote count of the 2016 election). To better understand who felt most targeted by campaign rhetoric, we measured gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religious affiliation and religiosity, legal resident status, whether participants were born in the U.S., whether they voted, and who they supported in the election.

Results

Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and Cohen’s ds for condition differences on key variables can be found in .

Table 3. Study 1 – Bivariate correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Main Study Variables Including Political Orientation.

Manipulation Check

An independent samples t-test revealed that, as expected, participants perceived that a higher percentage of Americans supported Trump in the high support condition (M = 43.97, SD = 19.07) than in the low support condition (M = 35.15, SD = 16.72), t (288) = – 4.19, p < .001, d = .49, CI.95 (.26, .73), thus confirming the effectiveness of our manipulation.

Analysis plan

To test hypotheses about the effects of our experimental manipulation on fit and expected discrimination, we conducted a series of linear regression analyses. Each analysis regressed an outcome variable on condition (0 = Low Trump support; 1 = High Trump support), perceptions of being targeted (a z-scored continuous variable), and their interaction, while controlling for our pre-registered covariates (age, education, employment status, lives in rural vs. urban area, lives in blue vs. red state, political orientation, and income; all z-scored).

Pre-registered hypotheses focused on testing condition by feeling targeted interactions for fit and identification – the primary outcome variables – as well as social identity threat and expected discrimination – our secondary outcome variables. However, given the unique ability of this study to index whether there were general concerns with feeling lower fit and expecting greater discrimination around Trump’s election, we also had a stated interest in the main predictive relationship of feeling targeted by Trump’s rhetoric (regardless of the priming manipulation) with key outcomes. Results of regression models including p-values are summarized in . In addition, Table S3b of the SOM shows that controlling for support for Trump also did not change any conclusions.

Table 4. Study 1: Results of Linear Regression Analyses (standardized betas and p-values) Predicting Core Outcome Variables from Condition, Feeling Targeted, and their Interaction.

Feelings of social and self-concept fit

Analyses with social fit and self-concept fit as outcomes revealed that those who felt most targeted by campaign rhetoric reported significantly less social fit, ß = – .15, CI.95 (−.27, −.02), but not less self-concept fit, ß = .01, CI.95 (−.13, .14), within American society. However, the manipulation itself did not have a significant main or interactive effect on either social fit, bmain = −.15, CI.95 (−.38, .08); ßint = – .05, CI.95 (−.29, .19), or self-concept fit, bmain = −.15, CI.95 (−.39, .09); ßint = – .09, CI.95 (−.34, .16).

American identification

When the same analyses were repeated with self-reported American identification as an outcome, results revealed a non-significant trending effect of condition, such that those in the high Trump support condition rated their American identity as descriptively less important to themselves than those in the low Trump support condition, b = −.20, CI.95 (−.43, .00). Although not significant in this study, this effect is replicated in Study 2, and suggests that being reminded of Trump’s election may lead some Americans to disidentify from their national identity. There was no significant main effect of feeling targeted by Trump’s rhetoric, ß = −.03, CI.95 (−.16, .10), and the predicted interaction was not significant, ß = −.11, CI.95(−.35, .13).

Social identity threat and discrimination

We next tested secondary predictions about social identity threat and anticipated discrimination that mirrored our predictions regarding sense of fit. Results of regression analyses revealed that those who felt targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric expected to experience significantly more social identity threat, ß = .40, CI.95 (.28, .53), and more frequent discrimination within the next month, ß = .46, CI.95 (.34, .59). Condition had no main or interactive effects on these variables, all ßs < .17.

Focused analyses on those targeted by trump

Given our theoretical focus on the experience of those who feel targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric, we pre-registered exploring the indirect effect of condition on American identification through social and/or self-concept fit among those who responded with a 4 or 5 on the targeted measure, (n = 128 with complete data). We tested these pre-registered hypotheses with two path models6 (testing each type of fit separately) using the lavaan7 package (Rosseel, 2012), including the same pre-registered covariates specified in the omnibus analyses. In this segment of the sample, being exposed to information suggesting that Americans strongly support Trump (vs. Clinton) significantly reduced American identification, b = −.35, t (119) = −2.08, SE = 0.17, p = .039, CI.95 (−69, −.02); recall that this main effect was non-significant in the larger sample.

Furthermore, results of path analyses (bootstrapped standard errors) indicated that reading about high (vs. low) Trump support was significantly associated with lower self-concept fit, a-path, ß = −.34, SE = .17, z = −1.99, p = .046, CI.95 (−.66, −.01); but not with significantly lower social fit, a-path, ß = −.27, SE = .18, z = −1.47, p = .142, CI.95 (−.60, .12) among this targeted subgroup. As hypothesized, both social fit, b-path, ß = .30, SE = .08, z = 3.62, p < .001, CI.95 (.15, .46), and self-concept fit, b-path, ß = .43, SE = .08, z = 5.47, p < .001, CI.95 (.28, .58), were significantly positively related to American identification. However, neither the indirect effect through self-concept fit, a*b = −.15, SE = .08, z = – 1.89, p = .059, CI.95 (−.32, −.01), nor social fit was significant, a*b = – .08, SE = .06, z = – 1.83, p = .167, CI.95 (−.22, .02).8

Discussion

In Study 1, our aim was to understand how individuals who identified as part of a group targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric felt impacted by the democratic election of Donald Trump as the new U.S. president. We found preliminary evidence that those who felt targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric tended to report lower social fit, greater social identity threat, and expected more discrimination. However, feeling targeted was not significantly related to self-concept fit within American society. This suggests that being part of a group targeted by a democratically elected political leader might especially provide cues about how others in the society think about one’s ingroup.

We also found that a manipulation of support for Trump had suggestive but non-significant effects on those who feel marginalized by Trump’s rhetoric. Specifically, in preregistered focal analyses among those who felt highly targeted, participants reported significantly lower American national identification after reading about support for the new president (vs. support for Clinton).

Furthermore, reading about support for Trump (vs. support for Clinton) lowered feelings of self-concept fit among those who felt targeted, and these relatively lower feelings of self-concept fit, in turn, predicted lower feelings of American identification. However, the overall indirect effect as well as the interaction with target identification in the full sample were not significant, leaving us with no clear evidence of a mechanism from this first study.

Although we found only mixed evidence that our experimental manipulation of support for Trump caused statistically detectable increases in identity-based concerns among members of targeted groups, this study is novel in that it provides first clear evidence that simply feeling targeted by political rhetoric of the winner in a national election predicts lack of perceived social fit in American society. In addition, we provide additional empirical evidence supplementing qualitative studies suggesting that those who felt part of a group targeted by Trump were increasingly concerned with experiencing discrimination during Trump’s presidency (Abreu et al., Citation2021; Brown & Keller, ; Daftary et al., Citation2020; Drabble et al., Citation2018a; Veldhuis et al., Citation2018b, Citation2018a). A key limitation of Study 1 is that, although Clinton won the popular vote, as specified in one of our experimental conditions, Trump was the de-facto elected president and cues of this election were ubiquitous at the time of data collection. This may have severely weakened the degree to which reminders of popular support for Clinton could mitigate concerns about the future reality under Trump’s administration. It is then likely that those cues of Trump’s presidency were in fact made salient by both conditions in our design.

We anticipated this possibility when conducting Study 1, and thus designed and pre-registered a second study that was carried out approximately one week later (i.e., at the time of Trump’s inauguration in January 2017) and before Study 1 data were analyzed. In this second study, we tested hypotheses utilizing the same dependent measures but employing a stronger manipulation to alter participants’ sense of living in an identity-safe vs. identity-unsafe political context. Specifically, we asked participants to complete measures while reflecting on the past four years under Obama’s administration or while imagining the upcoming four years under Trump’s administration. This sample constitutes a truly unique historical sample given that data collection straddled the exact point in history at which Trump took office, and was largely complete before Trump enacted specific policies that might constitute explicit institutionalized discrimination9. In addition, we also aimed to collect a larger sample in this second study, increasing our statistical power to detect mediation, especially among the sub-sample of those who feel targeted by Trump (Fritz & Mackinnon, Citation2007).

Study 2

Method

Participants

A final sample of 360 participants (149 men/203 women/3 trans/4 other) were recruited from MTurk and completed the study for $1.50. We pre-registered (https://osf.io/2n82e/?view_only=8ac319b6fbe7448d86d5ab179b4c5ed1) our aim to recruit 500 participants to obtain a usable sample of at least 300 after exclusions, which would allow us to detect a large indirect effect (in the half of our sample that felt targeted) at 80% power (power analyses conducted according to guidelines by Fritz & Mackinnon, Citation2007). As pre-registered and as in Study 1, we excluded an additional 128 participants10: 9 participants failed attention checks, 8 were not legal or permanent residents of the U.S., 32 who showed excessively fast reaction times suggesting inattention (more than 10% of responses below 300 ms on the implicit measure described in SOM), and 69 participants who strongly supported Trump. Sample demographics were similar to Study 1 (see, ).

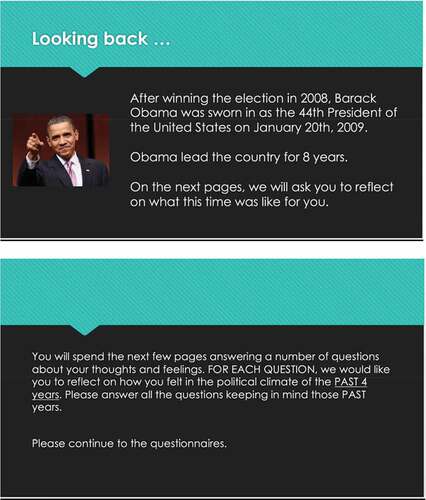

Procedure and manipulation

As in Study 1, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire and rated their identification as a targeted group member prior to the manipulation (see, ). For this study, we harnessed the salience of Trump’s inauguration on Friday, 20 January 2017 to strengthen our manipulation, yoking the manipulation itself to whether participants signed up and completed the survey in the days prior to or following this date. Specifically, half of the sample (Obama Administration condition, n = 181) were recruited and completed the survey on the Monday, Tuesday, or Wednesday before the inauguration (January 16–18, 2017). Participants in this condition were shown a page reminding them that the Obama administration is coming to an end and were instructed to “reflect on how [they] felt in the political climate of the PAST 4 years” throughout the survey.

The other half of our sample (Trump Administration condition, n = 179) were recruited and completed the survey on the same weekdays after the inauguration (January 23–25, 2017). Participants in this condition were shown a page reminding them that Trump has just taken office as the president and were instructed to anticipate “how [they] will feel in the political climate of the NEXT 4 years”. In line with these framings, wording of questions differed slightly between conditions to remind people which time period they were supposed to think about (see Appendix 2 for detailed manipulation and item wordings). Otherwise, as in Study 1, participants rated social fit (2 items, r = .95), self-concept fit (2 items, r = .78), explicit American identification (4 items; α = .91), social identity threat (2 items, r = .49), expectations of discrimination (2 items, r = .85), and the same demographics.11

Results

Analysis plan

Correlations, means, and condition differences for these variables are summarized in . As in Study 1, we conducted a series of linear regression analyses, regressing each outcome variable onto condition (0 = Obama; 1 = Trump) and identification as a member of a targeted group (a continuous z-scored variable) on Step 1, and their interaction on Step 2, while controlling for our pre-registered covariates (political orientation, age, education, employment status, lives in rural vs. urban area, lives in blue vs. red state, and income; all z-scored). As in Study 1, we pre-registered conducting analyses without strong Trump supporters and controlling for political orientation to ensure that variability observed in the extent to which individuals felt targeted by Trump’s campaign were not simply due to the extent to which individuals themselves supported the election of Trump. Results of these analyses, including p-values, are summarized in . As in Study 1, evidence summarized in Tables S5a and S5b of the SOM show that conclusions were unchanged (and if anything became descriptively stronger) when Trump supporters were included in analyses. In addition, Table S6b of the SOM shows that all conclusions further remain the same when controlling for support for Trump in the key effects.

Table 5. Study 2 – Bivariate correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Main Study Variables Including Political Orientation.

Table 6. Study 2: Results of Linear Regression Analyses (standardized betas and p-values) Predicting Core Outcome Variables from.

Social and self-concept fit

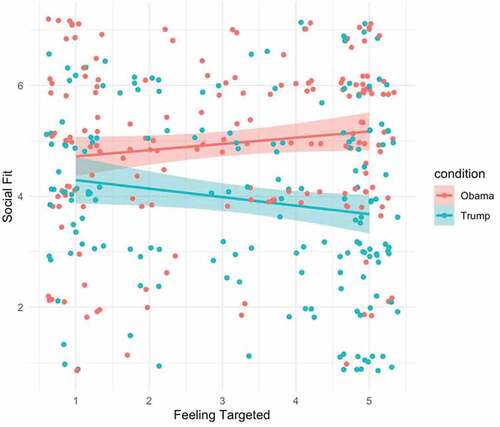

With the now arguably stronger manipulation and larger sample, analyses with social fit as an outcome revealed a significant main effect of condition, b = −.59, CI.95 (−.79, −.38), and the predicted targeted by condition interaction, ß = −.28, CI.95 (−.48, −.07), see, . Simple slopes analyses supported our preregistered hypothesis that those who identified as part of a highly targeted group (+1 SD, M = 4.87) felt significantly lower feelings of social fit when reflecting on Trump’s (vs. Obama’s) presidency, b = −.86, CI.95 (−1.15, −.57). Among those who did not identify as feeling highly targeted (−1 SD, M = 1.51), the effect of condition was also significant but weaker, b = −.31, CI.95 (−.60, −.03). Feeling targeted by Trump was positively but non-significantly related to social fit when participants reflected on Obama, ß = .15, p = .058, CI.95 (−.005, .30), but negatively though non-significantly related to social fit when participants reflected on Trump, ß = −.13, p = .093, CI.95 (−.28, .02).

Parallel analyses on self-concept fit as an outcome yielded only a main effect of condition. Participants in this sample generally felt a lower sense of similarity to the average American when imagining the future under Trump as compared to recalling the past under Obama, b = −.49, CI.95 (−.70, −.27). As in Study 1, there was no main effect of feeling targeted, ß = .06, t(313) = 0.99, CI.95 (−.06, .18), and no significant interaction between condition and feeling targeted, ß = .002, CI.95 (−.22, .22).

American identification

Repeating these analyses on American identification also yielded a significant main effect of condition, ß = −.27, CI.95 (−.47, −.06), whereas this effect was non-significant in Study 1 with a weaker manipulation. Across the sample, those reflecting on the Trump administration reported a weaker sense of identification with being American compared to those recalling the Obama administration. Feeling that Trump targeted one’s ingroup had no significant main, b = .02, CI.95 (−.09, .14), or interactive effect with condition, ß = .02, CI.95 (−.18, .23). Including Trump supporters in these analyses did not significantly change these results (see SOM).

Social identity threat and expected discrimination

As in Study 1, we also tested secondary hypotheses about social identity threat and expected discrimination with parallel analyses. As in Study 1, the extent to which participants identified as members of a targeted group predicted significantly greater feelings of social identity threat, ß = .28, CI.95 (.16, .39), and stronger expectations of discrimination, ß = .39, CI.95 (.28, .50). With the stronger manipulation of Study 1, we now found significant main effects of condition, all bs > .44, ts(312) >4.37, ps < .001 that were qualified by the predicted condition feeling targeted interaction for both social identity threat, ßinteraction = .43, CI.95 (.23, .62), and expectations of discrimination, ßinteraction = .41, CI.95 (.23, .60). Decomposing these interactions revealed that those who identified as part of a highly targeted group (+1 SD) experienced greater social identity threat, b = .88, CI.95 (.60, 1.16), and expectations of discrimination, b = 1.00, CI.95 (.73, 1.26), when reflecting on Trump compared to Obama. Those who did not identify as part of a targeted group (−1 SD) showed no such effect of condition on social identity threat, b = .03, CI.95 (−.25, .31), nor expectations of discrimination, b = .17, CI.95 (−.09, .44).

Focused Mediation Analyses on those Targeted by Trump

As pre-registered and parallel to analyses conducted in Study 1, we next tested indirect effects of condition through social fit and self-concept fit (in separate models) among those who identified as part of a highly targeted group (above the median score of 3, meaning those who scored 4 or 5 as in Study 1, n = 170 with usable data). Although the effect of condition on American identification was only a non-significant trend in this lower-powered sub-sample, b = −.26, t (148) = −1.71, SE = 0.15, p = .089, CI.95 (−56, .04), the indirect effects through both social fit and self-concept fit were significant, a*bsocial fit = −.22, SE = .10, z = – 2.29, p = .022, CI.95 (−.47, −.07); a*bself-concept fit = −.13, SE = .06, z = −2.24, p = .025, CI.95 (−.28, −.05). Among those who felt targeted by Trump, thinking about Trump’s (vs. Obama’s presidency) induced lower self-concept fit, a-path, ß = −.49, SE = .16, z = −3.06, p = .002, CI.95 (−.80, −.80), and social fit, a-path, ß = −.80, SE = .15, z = – 5.25, p < .001, CI.95 (−1.09, −.49); and both self-concept fit, b-path, ß = .27, SE = .09, z = 2.94, p = .003, CI.95 (.08, .44), and social fit, b-path, ß = .27, SE = .10, z = 2.72, p = .006, CI.95 (.06, .48), predicted stronger American identification.12 Thus, for those who already feel part of politically targeted group, thinking about Trump’s presidency indirectly cued a lack of fit in American society both via lowering social fit and self-concept fit.

Discussion

Study 2 utilized a stronger manipulation to better isolate how Donald Trump’s presidency led members of targeted groups to feel lower fit and identification with being American and also led such individuals to anticipate greater discrimination and social identity threat. Not only were all of these effects evident when participants imagined the four impending years of Trump’s presidency as compared with the prior four years of the Obama administration, but the social effects (social fit, social identity threat, and anticipated discrimination) were especially strong for those who reported membership in a group that was targeted by Trump’s rhetoric.

Importantly, however, even among those who did not feel especially targeted by Trump’s rhetoric, Trump’s inauguration led to lower feelings of self-concept fit and identification with being American (excluding those who strongly supported Trump’s election). Mirroring similar effects found among liberal leaning White Americans and Clinton supporters (Claypool et al., Citation2020; Dai et al., Citation2021), these findings suggest that many non-supporters of Trump questioned their personal relationship to America in the wake of Trump’s election. However, these results also go beyond that past work to identify that members of groups targeted by Trump especially experienced negative consequences for their sense of feeling accepted and included by other Americans.

Study 3 took place nearly four years after Studies 1 and 2 and was designed to test whether these important effects reversed when, in November 2020, Donald Trump lost his bid for reelection. Furthermore, whereas Studies 1 and 2 consisted of broad samples where only some considered themselves to be members of groups targeted by Trump’s rhetoric, in Study 3 we specifically recruited a sample from populations especially targeted by Trump, with half of the sample consisting of African Americans and the other half consisting of a diverse group of other ethnic minorities (Participants of this second group were largely Latinx and South East Asian, groups that are marginalized in different ways than Black Americans; see, Zou & Cheryan, Citation2017). During his presidency, Donald Trump enacted policies and made statements that explicitly disparaged certain racial and ethnic groups (e.g., calling immigrants from Mexico rapists) and/or condoned racism (e.g., referring to White supremacists involved in violent clashes in Charlottesville in 2017 as “very fine people.”). By surveying people from these groups either days before the election took place, or just after Biden was announced the winner, we were able to test pre-registered hypotheses that Biden’s election would lead to an increase in feelings of social fit, self-concept fit, and identification as an American (primary hypotheses) among people of color, as well as decreased feelings of social identity threat (secondary hypothesis). Given that a segment of the population continued to show vocal support for Trump and disdain for civil rights groups, such as Black Lives Matter (e.g., BBC, October 31st, 2020), we did not hypothesize that Biden’s election would lead to a reduction in anticipated discrimination or social identity threat but analyzed these effects as exploratory.

Study 3

Method

Participants

A final sample of 376 participants (185 men/185 women/4 non-binary/2 other) was recruited from the survey platform Prolific split into two simultaneously collected samples: one that was only open to Americans who identify as Black or African American (the racial group we surmised might feel most directly targeted by Trump’s rhetoric and policies in 2020) and one that was open more broadly to Americans who identify as nonwhite. We combined data across these sub-samples, however, and tested ethnicity (Black n = 189 vs. other people of color n = 187) as an exploratory moderator13. Based on the smallest main effect of interest in Study 2 (the main effect of condition on American Identification; d = .30;), we preregistered a target sample of at least 278 after exclusions to detect a one-tailed t-test with 80% power. As pre-registered, we collected a sample of 403 participants and excluded 6 participants who failed our attention check (“If you are reading this, please select six.”) and 19 participants who identified as “White/Caucasian”. The core independent variable (pre vs. post-election) was yoked to when participants completed the survey. One-hundred and eighty-nine participants completed the survey on October 29th and 30th, 2020, prior to the November 3rd election. The remaining 189 participants completed the study on November 7th and 8th, 2020, directly after the Associated Press announced Biden’s victory. A summary of the participant demographics can be found in .

Table 7. Summary of Sample Demographics in Study 3.

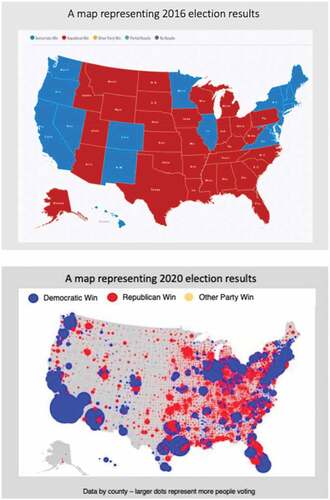

Procedure and materials

At both time points, participants were shown a map of election results (See Appendix) before completing our key-dependent variables. Those recruited prior to Biden’s election saw a map depicting the 2016 election results showing Trump’s win. States were colored red or blue to indicate a republican or democratic victory (the same map was used in Study 1). Participants recruited after the outcome of the election was called by the AP saw a map of the 2020 election results showing Biden’s win. This map showed voting data by county. For each county, a blue or red dot was used to represent Democrat and Republican votes. The size of the dot increased with the number of votes. This map visually emphasized Biden’s strong win because it emphasized the number of popular votes won.

After viewing the voting maps, as in Studies 1 and 2, participants rated their social fit (2 items; r = .88, p < .001), self-concept fit (2 items; r = .76, p < .001), American identification (4 items; α = .90), social identity threat (2 items, r = .29, p < .001), expectations of discrimination (2 items, r = .77, p < .001), and the same demographic variables. Correlations and condition differences for these variables are summarized in .

Table 8. Bivariate correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Main Study Variables Including Political Orientation in the Combined Study 3 Sample. Reported d-scores are from models without covariates.

Results

Focal pre-post analyses

Linear regression models were used to test for focal pre-post differences on our primary dependent variables of interest14. All p-values were two-tailed in reported results despite pre-registration of directional hypotheses. As pre-registered, these analyses were conducted controlling for age, political orientation, SES, education, and whether participants were born in America15. Results of these analyses, including p-values, are shown in . As hypothesized, participants, who were all part of minoritized racial groups, reported significantly higher feelings of social fit, d = 0.39, CI.95 (0.184, 0.596), self-concept fit, d = 0.233, CI.95 (0.028, 0.437), and American identification, d = 0.332, CI.95 (0.125, 0.538), after Biden’s was declared the winner compared to just before the election took place. As we had suspected, social identity threat, d = −0.084, CI.95 (−0.289, 0.125) and expected discrimination, d = −0.031, CI.95 (0.235, 0.173), did not significantly decrease after Biden’s election.

Table 9. Results of Linear Regression Analyses (standardized betas and p-values) Predicting Core Outcome Variables from Time.

Tests of mediation

We preregistered that if the effect of time-point on American Identity centrality was significant, we expected social fit and/or self-concept to mediate this effect. Parallel to analyses for Study 1 and 2, we tested this hypothesis with two path models using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012), where social fit and self-concept, respectively, were tested as mediators of the direct effect of time on American Identity centrality. Both models were run controlling for age, political orientation, SES, education, religiosity, gender, and whether participants were born in America. All continuous variables were standardized.

The model testing self-concept fit as a mediator revealed that the direct effect of time (pre vs. post Biden’s election) on American Identity centrality, b = 0.36, p < .001, CI.95 (0.18, 0.55), was mediated by self-concept fit, a*bself-concept fit = 0.11, SE = 0.05, z = 2.31, p = .021, CI.95 (0.02, 0.20), such that the direct effect of the manipulation was reduced in magnitude when accounting for self-concept fit, ß = 0.25, SE = 0.09, z = 3.01, p = .003, CI.95 (0.09, 0.43). The same was true for the model with social fit as a mediator: the direct effect of time (pre vs. post Biden’s election) on American Identity centrality, b = 0.36, p < .001, CI.95 (0.18, 0.55), was mediated by social-fit, a*bsocial fit = 0.13, SE = 0.04, z = 3.33, p < .001, CI.95 (0.05, 0.20), such that the direct effect of the manipulation was reduced in magnitude when accounting for social fit, ß = 0.23, SE = 0.09, z = 2.58, p = .010, CI.95 (0.06, 0.42)16.

General Discussion

The 2016 and 2020 presidential elections were some of the most controversial elections in American history, in part because of Donald Trump’s often divisive identity-based rhetoric. Largely qualitative or descriptive research suggested that members of marginalized groups experienced increases in stress, fear of discrimination, and identity threats in the aftermath of the 2016 election (Abreu et al., Citation2021; Albright & Hurd, Citation2020; Brown & Keller, ; Drabble et al., Citation2018a; Gonzalez et al., Citation2018; Veldhuis et al., Citation2018a). More recent research suggests that Trump’s rhetoric was unfortunately influential; explicit prejudice did increase among Trump supporters in the years during his presidency (Ruisch & Ferguson, Citation2022). To what degree did members of groups who were targeted by Trump anticipate these effects by exhibiting threats to their sense of fit with America when Trump was elected? And to what extent did Trump’s failed reelection alleviate these concerns?

The three pre-registered studies in the current manuscript provide novel evidence for the effects of Trump’s election on people’s expectations about how others in society will treat them, and to a lesser degree, how their self-concept fits within broader American society. Specifically, Study 1 found that those who felt their social group was targeted by Trump’s campaign rhetoric tended to report lower social fit, as well as greater social identity threat, and expectations of discrimination. In Study 2, especially members of targeted groups anticipated feeling less acceptance from other Americans (lower social fit), as well as more frequent social identity threat and discrimination in the ensuing years of the Trump presidency compared to their recollection of the past four years during Obama’s second term. In a sense, these findings demonstrate that members of social groups targeted by Trump anticipated the increased social exclusions they were in fact later subjected to during Trump’s presidency (Ruisch & Ferguson, Citation2022).

Study 3 demonstrated that some of these effects reversed when Trump lost his reelection bid in 2020. Specifically, participants from minoritized ethnic backgrounds felt significantly stronger social fit after Biden won the election, compared to the days before. This suggests that the failure of Trump’s reelection bid reinstated a sense of social acceptance from compatriots in members of groups negatively targeted by Trump. As we suspected, however, expectations of social identity threat and discrimination did not show such a significant reversal, underlining the continued racial tensions that were connected to the 2020 election (BBC, October 31st, 2020).

Findings on self-concept fit within American society were more mixed and point toward a generally lowered sense of self-concept fit in the wake of Trump’s election, regardless of group membership. In Study 1, feeling targeted by Trump’s rhetoric did not predict feeling lower self-concept fit within American society. In Study 2, reflecting on the Trump (vs. Obama) presidency lowered self-concept fit regardless of whether participants felt they were part of a group targeted by Trump’s rhetoric. Similarly, in Study 3, self-concept fit was stronger after Biden was elected. The lowered self-concept fit associated with Trump’s presidency in Study 2 and Study 3 may have been a function of Clinton voters, who predominated in that sample, and generally felt alienated by Trump’s election. Indeed, analyses detailed in Table S6a and S6c of the SOM suggested that in Study 2 (the sample with most diverse political orientations), the more participants supported Clinton, or identified as liberal (vs. conservative) in general, the more they reacted to thinking about the Trump (vs. Obama) presidency with lowered social fit, lower self-concept fit, and American identification, as well as increased expectations of social identity threat and discrimination. These findings complement evidence by Young and colleagues (2009) as well as Claypool et al. (Citation2020) suggesting that psychological overlap with an elected candidate predicted heightened feelings of belonging when one’s preferred candidate won. Whereas these findings suggest that political orientation plays an important role in how people reacted to Trump’s election, they do not negate the hypothesized effects we found for those who feel their ingroup was marginalized by Trump. Specifically, all of our key effects were robust to controlling for a number of demographic factors, most notably political orientation (and support for Trump as detailed in the SOM), suggesting they were not simply due to liberals lamenting a conservative win in the election. However, future research could run more targeted studies to disentangle effects of self-concept fit versus social fit which were highly correlated in these studies.

In addition to effects on fit, we also demonstrate important and consistent effects on national identity in all three studies. In Study 1 and 2, those who felt targeted by Trump experienced lower American identification when confronted by Trump’s presidency (though note that the effect in Study 2 was non-significant). Trump’s failure to get reelected seemed to reverse these effects. In Study 3, participants who self-identified as ethnic minorities felt stronger American identity in the days after Biden/Harris’s election compared to before. In line with our overall argument, this suggests that the democratic election of a divisive political leader sends powerful cues of fit and national identity to members of marginalized groups.

This research offers novel insights into how political events can provide cues to fit and social identity threat among marginalized groups. Past research suggests that members of minoritized social groups in America frequently experience feelings of social identity threat in institutional settings (Walton & Cohen, Citation2007) and also feel less accepted in mainstream society overall (Phinney, Cantu, & Kurtz, Citation1997). Our evidence suggests that these feelings can be triggered by the election and failed reelection of a political leader that strategically devalues one’s social group. Our findings align with and extend recent qualitative and survey research that identifies belonging, discrimination, and even physical threats as key concern among women and minority group members in the wake of the 2016 election (Brown & Keller, ; Daftary et al., Citation2020; Drabble et al., 2018b; Gonzalez et al., Citation2018; Veldhuis et al., Citation2018b). As such, our results empirically demonstrate that formal political events, such as the democratic election of an individual who portrayed marginalized groups in a negative light during his campaign, can send powerful cues regarding the extent to which social groups are accepted and valued in American society.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the timeliness of this research and its contribution to our understanding of fit and social identity threat in the political realm, our research has several important limitations that provide an avenue for future research. First, future studies will need to investigate how those with intersecting target identities might react differently to identity-based rhetoric. About half of those in our sample who felt targeted by Trump in Studies 1 and 2 reported feeling targeted on the basis of their identity as a woman, most of whom identified as White. Sexism was, certainly, an important component of the biases that were frequently expressed in the 2016 election (e.g., when a video of Trump proclaiming “Grab them by the pussy” surfaced in the month preceding the national election). Studies examining predictors of support for Trump find that, even when controlling for a number of ideological individual differences, sexist belief predicted stronger support for Trump (Bock et al., Citation2017). In addition, heightened concerns of sexism among women post-election (Does, Guendemir, et al., 2019) fit well with our findings that many women in our sample from 2017 felt targeted by Trump. Thus, White women legitimately experienced and perceived a devaluation of their identity during the election. However, women of color are likely to have uniquely negative experiences and expectations of devaluation that would be worthy of more focused inquiry.

Furthermore, White women’s American identity is rarely called into question in the same way that minoritized racial or religious identities often are (Cheryan & Monin, Citation2005; Devos & Banaji, Citation2005; Huynh et al., Citation2011). To start exploring effects by subgroup for Study 2, we reported correlations separately for White women, White men, and minoritized ethnic and religious groups in SOM Table S10. These patterns suggest that feeling targeted had very similar relationships to key variables for White women, ethnic minorities, and religious minorities – although the effects of experimental condition were descriptively stronger for minoritized ethnic and religious groups than for White women.

To further address this limitation of Studies 1 and 2, Study 3 focused specifically on recruiting only people of color in the U.S. However, it is possible that different sub-groups (e.g., Black, vs. Latino, vs. Muslim) would show different reactions to Trump. Zou and Cheryan’s (2017) Model of Racial Position in the US may provide a framework for understanding how different minoritized racial groups in the US could be affected differently by a leader such as Trump. The model outlines that ethnic and racial minorities are marginalized along two distinct dimensions in the US; cultural foreignness and inferiority. For example, while African Americans are seen as inferior, they are not perceived as foreign. Latinx people, in contrast, are seen as both inferior and foreign, whereas Asians are seen as foreign but not inferior to Whites. In our sample, we purposely over-sampled Black Americans given that Trump’s failure to support the Back Lives Matter movement and encouragement of white nationalist groups was particularly salient around the 2020 election. In line with this political sentiment, exploratory analyses detailed in the SOM (Figure S1) show that Biden’s election led to greater increases in American identity among Black participants compared to participants from other minoritized racial/ethnic groups.

However, our sample of non-black participants of color was not large enough to be sensibly divided into further subgroups for statistical analyses. Theoretically, we would expect distinct effects. From Zou and Cheryan’s model (2017), we might predict distinct effects on social and self-concept fit among Black, Lantix, and Asian Americans. Similarly, our studies were not designed to examine the specific threat faced by the LGBTQ+ community under the Trump administration (e.g., NPR, March 2nd, 2020). Follow-up research could specifically seek to sample different marginalized groups to discern unique effects that political leaders have on their experience.

Relatedly, our research did not examine how democrats or republicans (including those from advantaged social groups) experienced Trump’s election win and loss. Members of either political party might experience diminished fit when their preferred candidate loses an election, assuming that self-concept fit is affected by learning that others do not share important beliefs. For example, in Study 2 self-concept fit decreased when thinking about the Trump (vs. Obama presidency) among democrat-leaning participants as a whole (given that we excluded strong Trump supporters), and these effects were not moderated by identifying as part of targeted group. Such evidence matches findings by Young et al. (Citation2009) and Claypool et al. (Citation2020) discussed previously. In contrast, our results (especially Study 2 and 3) suggest that social fit is uniquely affected by Trump’s election for those belonging to marginalized groups targeted by Trump. Future research could nevertheless further clarify the intersection of political party affiliation and social group membership.

Another limitation of the current research is that we focused on people’s own sense of fit and their expectations of social identity threat and discrimination in the vacuum of (quasi) experimental designs. Whereas research does suggest biased attitudes were legitimized and thus increased after Trump’s election (Crandall, Miller, Ii et al., Citation2018; Ruisch & Ferguson, Citation2022), future research should examine how this plays out in the everyday personal interactions and experiences of members of marginalized groups over time. Follow-up work could, for example, more directly examine how change in popular support for Trump translates into changes in fit and identity threat among minority group members in their everyday life. Such longitudinal research might also identify coping strategies that members of marginalized groups employ to preserve a positive sense of identity in otherwise threatening circumstances (e.g., Crocker & Major, 1989). In line with a disengagement model of social devaluation (Steele et al., Citation2002), it will also be important to investigate how reported perceptions of threats to belonging and national identity impact actual future behaviors, such as political participation or activism. Dai and colleagues (2021) found the liberal leaning White American’s who felt a sense of identity threat from Trump’s election were more likely to signal their support for racial justice issues. It is not yet known whether targeted groups exhibited similar increases in political activism or coalition building with each other.

Finally, as these are the first studies examining this phenomenon, future studies could go further to identify the mechanisms through which the election of leader like Trump affects perceptions of national fit and identity. The election of someone like Donald Trump could threaten fit and identity among individuals from marginalized groups for at least two key reasons. First, given what a candidate has promised in their campaign, members of marginalized groups would likely anticipate specific policies or laws that would negatively impact them and hinder their fit in society. Second, the democratic election of a leader sends a powerful signal of how people within the nation want their world to look (Bass, 1990; Hais, Hogg, & Duck, 1997). Thus, if a political candidate who appears biased against one’s ingroup is elected by one’s fellow citizens, this should specifically strengthen perceptions that one’s fellow citizens devalue the ingroup and that one cannot expect to fit in with them. While both of these factors are likely to play a role to some extent, future research may want to distinguish these pathways.

Despite these limitations, these findings offer novel perspectives on how political events provide cues to fit and identity for groups who feel devalued in society. Identifying factors that erode a sense of fit and identification for members of marginalized groups is more important than ever. Especially, as we enter an era in which fostering diversity and inclusion is ironically seen by some as being at odds with reducing political polarization. By understanding how current world events shape groups’ sense of place in society, we can facilitate representation and fit for everyone.

SAI_205.21_Supplementary_File_Clean.docx

Download MS Word (197.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2022.2113124

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abreu, R. L., Gonzalez, K. A., Capielo Rosario, C., Lindley, L., & Lockett, G. M. (2021). “What American dream is this?”: The effect of Trump’s presidency on immigrant Latinx transgender people. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(6), 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000541

- Aday, A., & Schmader, T. (2019). Seeking authenticity in diverse contexts: How identities and environments constrain “free” choice. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12450

- Albright, J. N., & Hurd, N. M. (2020). Marginalized identities, trump-related distress, and the mental health of underrepresented college students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3–4), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12407

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

- BBC. US election 2020: The great dividing line of this campaign. By Aleem Maqbool, October 31st, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2020-54754792

- Bock, J., Byrd-craven, J., & Burkley, M. (2017). The role of sexism in voting in the 2016 presidential election ☆. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.026

- Bracic, A., Israel-Trummel, M., & Shortle, A. F. (2019). Is sexism for white people? gender stereotypes, race, and the 2016 presidential election. Political Behavior, 41(2), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9446-8

- Brown, C., & Keller, C. J. (2018). The 2016 presidential election outcome: fears, tension, and resiliency of GLBTQ communities. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 14(1–2), 101–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2017.1420847

- Brown, R. P., & Pinel, E. C. (2003). Stigma on my mind: Individual differences in the experience of stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(6), 626–633.

- Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103–125.

- Cheryan, S., & Monin, B. (2005). Where are you really from?: Asian Americans and identity denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(5), 717.

- Cheryan, S., Ziegler, S. A., Montoya, A., & Jiang, L. (2017). Why are some STEM field more gender balanced than others? Psychological Bulletin, 206. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000052

- Claypool, H. M., Trujillo, A., Bernstein, M. J., & Young, S. (2020). Experiencing vicarious rejection in the wake of the 2016 Presidential election. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 23(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430218798702

- Cohen, G. L., & Garcia, J. (2008). Identity, Belonging, and Achievement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(6), 365–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00607.x

- Cook, J. E., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Garcia, J., & Cohen, G. L. (2012). Chronic threat and contingent belonging: Protective benefits of values affirmation on identity development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 479.

- Crandall, C. S., Miller, J. M., & Ii, M. H. W. (2018). Changing Norms Following the 2016 U S . Presidential Election. The Trump Effect on Prejudice, 9(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617750735

- Crandall, C. S., Miller, J. M., & White, M. H. (2018). Changing Norms Following the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election: The Trump Effect on Prejudice. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617750735

- Daftary, A. M., Devereux, P., & Elliott, M. (2020). Discrimination, depression, and anxiety among college women in the Trump era. Journal of Gender Studies, 29(7), 765–778.

- Dai, J. D., Eason, A. E., Brady, L. M., & Fryberg, S. A. (2021). #Notallwhites: liberal-leaning white Americans racially disidentify and increase support for racial equity. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(11), 1612–1632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220987988

- Devos, T., & Banaji, M. R. (2005). American= white?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 447.

- Does, S., Gündemir, S., & Shih, M. (2019). The Divided States of America: How the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election Shaped Perceived Levels of Gender Equality. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(3), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618757033

- Drabble, L. A., Veldhuis, C. B., Wootton, A., Riggle, E. D. B., & Hughes, T. L. (2018a). Mapping the landscape of support and safety among sexual minority women and gender non-conforming individuals : perceptions after the 2016 US presidential election. Sexual Research and Social Policy.

- Fritz, M. S., & Mackinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x.Required

- Garrison, S. M., Doane, M. J., & Elliott, M. 2018. Gay and lesbian experiences of discrimination, health, and well-being : surrounding the presidential election. 9(2): 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617732391

- Georgeac, O. A. M., Rattan, A., & Effron, D. A. (2019). An exploratory investigation of Americans’ expression of gender bias before and after the 2016 presidential election. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(5), 632–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618776624