Abstract

This study sought to expand the scope of research on bi+ (bisexual and other plurisexual orientations such as pansexual) women and their experiences with disordered eating. A small body of research suggests that bi + women are at elevated risk of disordered eating compared with many other demographics, and this may be attributable to minority stress experiences (i.e., discrimination). The mechanism by which discrimination affects disordered eating in bi + women, however, remains unexamined. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationships between bisexual discrimination and disordered eating behaviors in bi + women. N = 250 bi + women completed an online survey including the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, the Brief Version of the Anti-Bisexual Experiences Scale, and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. A series of mediation analyses showed that bisexual discrimination was indirectly associated with binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and restraint through psychological distress, with the relationship between bisexual discrimination and binge eating becoming non-significant when considering psychological distress. This study illustrates the importance of understanding bisexual discrimination and psychological distress when examining disordered eating in bi + women. Implications may inform research and clinical practice focused on promoting bi + women’s overall health. Future work should seek to examine these relationships longitudinally to investigate their temporal nature.

Disordered eating behaviors (DEBs) are a term used to identify and describe a wide range of abnormal eating behaviors that can appear at subclinical levels (Austin et al., Citation2013). These maladaptive behaviors are typically aimed at controlling body weight and shape and/or reducing negative emotions (Hadland et al., Citation2014). Behaviors can include fasting (i.e., voluntary abstinence from food for a certain period of time), binge eating (i.e., eating an objectively large amount of food in an uncontrolled manner, over a short period of time), and compensatory behaviors (i.e., using behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or emetics, or excessive exercise to counteract perceived overeating or reduce guilt associated with eating). DEBs are found to have severe consequences, with research suggesting that frequent engagement may lead to significantly higher rates of morbidity and suicide compared to standard population norms (Ágh et al., Citation2016). For some, undetected and/or untreated DEBs can act as precursors of clinical eating disorders (EDs; Kärkkäinen et al., Citation2017); a major public health concern, worldwide (Erskine et al., Citation2016; Hay et al., Citation2015). The global prevalence of DEBs is much higher than formal ED diagnoses (Levinson & Brosof, Citation2016), and thus, understanding the etiology of DEBs is deemed pivotal.

Although disordered eating can affect all individuals, disparities have been found in specific marginalized groups, such as sexual minorities (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual; Austin et al., Citation2013; Nagata, Ganson, et al., Citation2020; Simone et al., Citation2020). Previously, the majority of disordered eating research seldom reported the sexual orientation of participants, however, emerging evidence illustrates disordered eating risk is disproportionately higher among LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual) populations (Calzo et al., Citation2017; Hadland et al., Citation2014). As such, sexuality-specific risk factors have since been evaluated, with several studies requesting further investigation into sexual discrimination: biased and prejudicial treatment based on sexual orientation and identity characteristics, and the resultant psychological distress (Cao et al., Citation2022; Parker & Harriger, Citation2020). Research regarding disordered eating in relation to bi+ (bisexual and other plurisexual orientations like pansexual) women is a relatively emerging field that is yet to be fully defined (Dotan et al., Citation2021). Studies have not yet concurrently separated bi + individuals of various genders, particularly in cases where specific DEBs are distinguished (Brewster et al., Citation2014; Jhe et al., Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2016). Exploring bi + women’s experiences of disordered eating is particularly important, given recent studies have found greater DEB prevalence among these women, relative to women with lesbian or heterosexual orientations (Chmielewski & Yost, Citation2013; Watson et al., Citation2016). Thus, it is imperative to gain a deeper understanding of the affiliated factors contributing to this elevated risk, to ameliorate current interventions which do not consider the role of sexuality-specific risk factors. This study explored the relations of bisexual discrimination and psychological distress to DEBs in bi + women.

Disordered eating and sexual minorities

Although disordered eating is widespread across all demographic strata (Hay et al., Citation2015), a substantial body of research has found an increased prevalence of disordered eating psychopathology among the LGBTQIA + population (Arcelus et al., Citation2018; Shearer et al., Citation2015; Simone et al., Citation2020). Results of a representative study (N = 35,995) conducted in the United States reported sexual minority adults had between two to four times greater odds of experiencing symptoms of bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge eating disorder compared to heterosexual adults (Kamody et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, sexual minority adults were found to be at elevated risk of engaging in unhealthy weight control behaviors, including fasting, purging (e.g., self-induced vomiting, laxative use) and restricting caloric intake (Calzo et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2019; Nagata, Ganson, et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Diemer et al. (Citation2015) and Simone et al. (Citation2020) both found sexual minority individuals exhibited greater ED symptomatology occurring at higher rates than heterosexual individuals.

Interestingly, disordered eating literature concerning sexual minority men seems to have received considerably more attention than sexual minority women (SMW; Bankoff & Pantalone, Citation2014). This may be, in part, due to initial research findings indicating lesbian women had a reduced likelihood of experiencing EDs and body dissatisfaction compared to heterosexual women (Siever, Citation1994; Strong et al., Citation2000). Additionally, findings for sexual minority men seem to be clearer and more consistent than SMW, with a consensus across the literature indicating sexual minority men experience more symptoms of disordered eating compared to heterosexual men (Calzo et al., Citation2017; Gigi et al., Citation2016; Matthews-Ewald et al., Citation2014). However, disordered eating research concerning SMW appears to be equivocal. Some studies suggest SMW experience more disordered eating than heterosexual women (Mason et al., Citation2018; Nagata, Ganson, et al., Citation2020). In a large scale study of Minnesota college students (N = 13,906) Simone et al. (Citation2020) found that cisgender SMW had greater self-reported EDs compared with cisgender heterosexual women. Similarly, Jones et al. (Citation2019) found SMW (n = 197) reported more frequent fasting, binge eating, and laxative use compared to heterosexual women (n = 768). Moreover, the results of a longitudinal study also found that SMW had greater rates of restrictive dieting (Luk et al., Citation2019).

In contrast, other studies have found minimal DEB differences between heterosexual women and SMW. For instance, in a meta-analysis of 21 studies, heterosexual women and lesbian women did not significantly differ in overall disordered eating (Dotan et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, Yean et al. (Citation2013) found SMW (n = 86) did not differ from heterosexual women (n = 361) in a lifetime prevalence of EDs. Moreover, Moore and Keel (Citation2003) also found no differences between heterosexual women (n = 47) and SMW (n = 45) when investigating bulimic symptomology. However, the majority of these studies focused on comparing heterosexual women with all SMW subgroups, overlooking the distinct analysis of bi + women. This omission may contribute to the inconclusive results (Hazzard et al., Citation2020). As bi + women have elevated risk of adverse mental health outcomes compared to other sexual minority groups (McCann et al., Citation2020; Simone et al., Citation2020), it is, therefore, beneficial to explore this group independently to generate more relevant findings.

Research has often prioritized gay men and lesbian populations over bisexual-related concerns in research (Watson et al., Citation2016). Hence, the number of studies on disordered eating among bi + populations specifically is relatively limited. Nevertheless, extant research suggests that bi + individuals experience more disordered eating and eating disorders than both heterosexual and lesbian/gay men populations (Simone et al., Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2018). In particular, Matthews-Ewald et al. (Citation2014) found bisexual college students (n = 3,310) were more likely to develop ED symptomology compared to their heterosexual peers (n = 102,191). Comparably, research has also suggested that DEBs were more frequent among individuals who reported attraction to two or more genders (Hazzard et al., Citation2020; Shearer et al., Citation2015). Although these studies provide rich perspectives into an often neglected population, it is important to note the majority have amalgamated bisexual men and women. This approach may have led to an oversight in recognizing the elevated risk for women to experience disordered eating (Ágh et al., Citation2016). It is therefore deemed necessary to not only examine the role of gender, but to also separate specific non-heterosexual identities to gain a richer understanding of the factors related to DEBs. When considering the research centered on disordered eating in bi + women, these studies provide valuable insights into this particular demographic. However, they do possess certain limitations. For example, although Watson et al. (Citation2016) investigated various factors that mediate disordered eating in bi + women, they did not explore specific outcomes of disordered eating. Likewise, in their examination of disordered eating in bi + women, Brewster et al. (Citation2014) presented only a global pathology of DEBs. Moreover, although Jhe et al. (Citation2021) revealed modest associations between minority stress and disordered eating in bi + individuals, their analysis encompassed all genders and did not distinctly focus on bi + women. Nevertheless, by considering factors that influence sexual minorities, like minority stress (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003), it may be helpful in understanding the factors contributing to disordered eating in bi + women.

The minority stress theory

Epidemiological research has found that in comparison to heterosexual people, sexual minorities are at greater risk of adverse mental health outcomes (Hay et al., Citation2015; Watson et al., Citation2016), including disordered eating (Arcelus et al., Citation2018; Calzo et al., Citation2017; Mason et al., Citation2018). This heightened vulnerability may be explained using the minority stress theory (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003)—a leading conceptual framework used to explain the discrepancies between the health of sexual minority persons compared with heterosexual persons. Meyer (Citation2003) suggests sexual minorities have an increased risk of mental health conditions due to chronic stress induced by societal stigmatization and discrimination. The theory, which also emphasizes the notion of heterosexism (i.e., the marginalization of LGBTQIA + individuals based on the belief heterosexuality is the norm; Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, Citation2013), suggests these unique stressors can lead to several psychologically injurious effects (Brooks, Citation1981; Friedman et al., Citation2014; Mason et al., Citation2017; Testa et al., Citation2015). Stressors can vary from external experiences like discrimination and harassment, to internal processes such as internalized homonegativity (i.e., shame toward oneself about one’s sexuality) and identity concealment (Frost et al., Citation2013; Mason & Lewis, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2018). These stigma-inspired experiences may create a cascade of stressful environments for victims, increasing psychological distress and vulnerability to poor mental health outcomes (McCann et al., Citation2020; Testa et al., Citation2015).

Although effective in deliberating the challenges among sexual minorities, Meyer (Citation2003) noted that acknowledging these groups as homogenous may obsure the unique differences tied to different orientations. For example, bi + individuals may share similar stressors with gay men/lesbian peers, but they may also encounter distinct bisexual-related issues, such as bisexual discrimination (Frost et al., Citation2013; Taylor, Citation2018). Thus, it is imperative to take heed of this concern to cultivate responsive interventions for this overlooked population.

Minority stress and bisexual discrimination

Respective lines of evidence indicate that bi + individuals living in predominately heterosexist societies may be subjected to chronic stress that is directly related to a unique form of prejudice; biphobia (Taylor, Citation2018). Biphobia (or bisexual discrimination) is a form of discrimination that exclusively targets individuals identifying with a sexual orientation that falls outside of the heterosexual-lesbian/gay men binary: bisexuality (Dyar et al., Citation2017). Emerging from both heterosexual and lesbian/gay men populations (McCann et al., Citation2020), biphobia is driven by negative attitudes that are deeply embedded within unique stereotypes about bisexuality (Dyar et al., Citation2017; Taylor, Citation2018). For instance, bisexual individuals are often labeled hypersexual and ambivalent in their sexuality, and perceived as untrustworthy romantic partners, incapable of monogamous relationships (Brewster et al., Citation2014; McCann et al., Citation2020). Experiences of bisexual discrimination are found to be particularly anxiety-inducing and may therefore lead to negative health outcomes (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009), including disordered eating (Brewster et al., Citation2014; Taylor, Citation2018). Although a modest body of literature exists on this matter, it is noteworthy that the investigation of DEBs as a product of sexual discrimination, let alone bisexual discrimination, remains relatively scarce within scholarly research. A recent exception found that 60.9% of LGBTQIA + individuals reported engaging in more than one DEB within the past 12 months; of these, 80.4% revealed they had also experienced at least one form of sexual orientation discrimination within that same year (Gordon et al., Citation2019). Although Gordon et al. (Citation2019) did not focus on bi + women, their study sheds light on the associations between sexual discrimination and DEBs, and whether bisexual discrimination impacts DEBs in bi + women warrants investigation.

The mediating effect of psychological distress

When an individual identifies with a minority status in a discriminatory and stigmatizing environment, the conflict between the person and the prevailing culture may be arduous, and the resultant psychological distress is substantial (Calzo et al., Citation2017; Watson et al., Citation2015). As a result, emerging data have found that marginalized individuals may engage in maladaptive behaviors as a method of coping with these elevated levels of distress (Carter et al., Citation2014; Dyar et al., Citation2017; McCann et al., Citation2020). However, literature is yet to explore the relationship between bisexual discrimination (a stigma-inspired event) and DEBs (maladaptive behaviors) in bi + women. This is not to say that when bi + women feel discriminated against, they then directly engage in disordered eating. Instead, it is more likely that bisexual discrimination causes a significant amount of psychological distress, which thus leads to an outcome of DEBs (Mason & Lewis, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2018). This may be particularly useful when exploring DEBs as a coping mechanism used by individuals to manage their levels of distress (Parker & Harriger, Citation2020). For example, studies have found that external stressors may lead individuals to feel as though they have no control over their social lives, which ultimately triggers an unconscious need to regain power in other areas of their life (Ball & Lee, Citation2000; Beukes et al., Citation2009). As such, food may be used as a control mechanism to neutralize the distress caused by having a sense of no control (Parker & Harriger, Citation2020) or offer ways of coping with distress through routine and comfort (Bayer et al., Citation2017; Colledge et al., Citation2020). However, these findings are based on the general population and have not yet been examined in the context of sexual orientation discrimination.

In their renowned paper on sexual minority stigma, Hatzenbuehler (Citation2009) proposed a theoretical framework that explains how an external, stigmatizing event can lead to adverse mental health outcomes among sexual minorities. The model, or the psychological mediation framework, posits that LGBTQIA + individuals experience increased levels of stress from stigmatizing experiences, which in turn, may shape their coping and cognitive processes in damaging ways that heighten general distress and psychopathology (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009; Schwartz et al., Citation2016). As bisexual discrimination is a remarkedly stressful experience (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009; McCann et al., Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2018), it is therefore highly likely that these prejudicial experiences may thus increase levels of psychological distress in bi + women (Carter et al., Citation2014; Dyar et al., Citation2017; McCann et al., Citation2020). Given increased levels of psychological distress have been found to be associated with higher levels of binge eating episodes in lesbian and bisexual women (Bayer et al., Citation2017) and greater frequencies in overall symptoms of disordered eating (Arcelus et al., Citation2018; Shearer et al., Citation2015), higher levels of bisexual discrimination may also be related to higher levels of DEBs in populations of bi + women. In consonance with this claim, Mason and Lewis (Citation2019) comparably suggested that the relationship between sexual orientation discrimination and DEBs among a sample of lesbian women was better explained when considering their levels of general distress. Seeing these findings occurred in one group of SMW, an investigation into whether a similar pattern occurs within another minority group, bi + women, is warranted. Thus, by adding a related variable justified by Meyer (Citation2003), and Hatzenbuehler (Citation2009), it may be theorized that bisexual discrimination increases levels of psychological distress which therefore increases DEB engagement in bi + women.

The Present Study

Research has illustrated a greater prevalence of disordered eating among LGBTQIA + populations, with several studies stipulating bi + women may be particularly at risk (Jones et al., Citation2019; Mason et al., Citation2018; Shearer et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, literature has also revealed that bi + women experience high degrees of bisexual discrimination (Katz-Wise et al., Citation2016; Taylor, Citation2018) which may lead to the engagement of maladaptive coping (Beukes et al., Citation2009; Calzo et al., Citation2017; Parker & Harriger, Citation2020). However, much of what is known about disordered eating in bi + women stems from research examining SMW as one group, or when bisexual men and women have been reflected together, with most favoring a male sample. This casts doubt on whether findings can accurately be generalized to bi + women, given their unique experiences have been overlooked. Furthermore, although there have been some studies conducted, the current body of scholarly research examining discrimination within a population already identified as high-risk (women) and underrepresented in research (bisexuality) remains limited. As a result, this study endeavored to address these substantial gaps within the literature, attempting to understand the relationship between bisexual discrimination and DEBs in bi + women, and test a theoretical model of their development that provides a foundation for future studies examining causality or establishment of risk factors using longitudinal designs.

It should be noted that due to the high amounts of variability across the presentations of disordered eating, the present study employed the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) to focus specifically on three behavioral outcomes: binge eating; consuming an excessive amount of food in an uncontrolled manner, restraint; purposely limiting caloric intake, and compensatory behaviors; inappropriate behaviors intended to prevent weight gain (APA, Citation2013). These behavioral outcomes were deemed appropriate categories due to their distinct characteristics, allowing for the identification of specific risk profiles that may manifest (e.g., compensatory behaviors may indicate bulimia nervosa; bingeing relates to bulimia and binge eating disorder, and restraint to anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; Nagata, Murray, et al., Citation2020). However, it is crucial to acknowledge that these behaviors can be present across various diagnoses (e.g., individuals with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder often adopt dietary restraint; Mason et al., Citation2018), and therefore cannot be relied upon solely to diagnose types of EDs. Thus, this research aimed to determine whether psychological distress mediates the relationships between bisexual discrimination and binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviors in bi + women. Two hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1. Higher perceived bisexual discrimination would be associated with higher binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviours in bi + women.

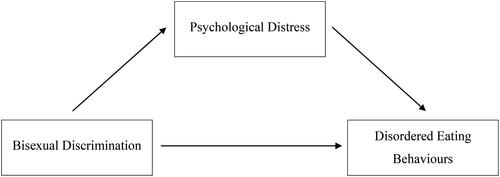

Hypothesis 2. The relationships between these variables would be mediated by psychological distress. Specifically, there would be an indirect effect of bisexual discrimination on binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviours through psychological distress, such that bisexual discrimination would be associated with psychological distress, that in turn, would be associated with binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviours (see ).

Method

Participants

Inclusion criteria required participants to be women aged between 18 and 30 years, living in Australia, as well as self-identifying as bisexual or another plurisexual orientation. The age group was chosen as age of onset for EDs is typically around late adolescence to early adulthood (Hudson et al., Citation2007).

Participants were drawn from a larger data set of N = 503 women of a range of sexual orientations, where n = 236 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria (i.e., not bi+, or were over the age of 30) and n = 17 were omitted for incomplete (i.e., did not complete one or more whole measures used in the current study) responses. The final sample comprised n = 250 individuals. See for detailed participants’ characterization. Following the guidelines of Feingold et al. (Citation2019) and Muthen and Muthen (Citation2002), a Monte Carlo simulation was conducted to evaluate the statistical power of each model. Bias was evaluated based on the coverage provided by confidence intervals in the percentage of replications for the simulation (Feingold et al., Citation2019; Muthen & Muthen, Citation2002). The acceptable range for bias in estimating confidence intervals is between .91 and .98 (Feingold, Citation2019). All estimates reported in this paper fell between these values to estimate significance for the pathways, although bias was outside of the acceptable range to provide accurate estimates of ORs for direct effects, and was slightly under the acceptable range of bias to estimate the confidence intervals for the direct effect for compensatory behavior (.90). As such, the precision of OR values for the direct effect, and CIs for the direct effect for compensatory behavior should be interpreted with caution.

Table 1. Retained Demographics of Study Sample.

Measures

Demographic information

Demographics were collected at the beginning of the survey. Participants were initially required to specify their sexual orientation and gender identity, then asked to report their age, highest level of education, relationship status, annual income, cultural and ethnic background, and country of birth. Sexual orientation was indicated from a list of options, including heterosexual, bisexual (including other non-monosexual orientations, e.g., pansexual), lesbian, and not listed. Those who selected not listed were invited to provide their sexual orientation in a text box. Those who specifically indicated any sort of attraction to more than one gender in their text response (n = 4) were coded as bi+ (for instance, a person responding as biromantic and asexual would be coded as bi+). As part of the larger study, participants were also asked for their height and weight, the gender of their partner (for those in a relationship), and their language predominately spoken at home.

Disordered eating behaviors

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, Citation1994) was used to measure participant levels of DEBs. Considered the most widely cited self-report measure in ED research/clinical practice (Nagata, Murray, et al., Citation2020), this 28-item scale assesses DEBs and attitudes over the past 28 days. As this study focused on the behavioral aspects of disordered eating, only the behavioral items of the EDE-Q were used, which are described below. Given that the current sample was a general sample rather than a clinical sample, the presence of behaviors (i.e., occurring vs not occurring) was considered, rather than the frequency of behaviors. This approach to measuring the behavioral component of disordered eating has been validated in prior research (Nagata, Murray, et al., Citation2020). Previously, the EDE-Q has demonstrated excellent reliability (Reas et al., Citation2006) and good validity in community samples of women (Mond et al., Citation2004; Nagata, Murray, et al., Citation2020). Although only the behavioral items were used in inferential analyses, internal consistency for the Global EDE-Q was excellent in the current sample; α =.96. The Global score for the sample was M = 2.20 (SD = 1.50), indicating slightly higher than community norms for a US based sample of cisgender bisexual women (Nagata, Murray, et al., Citation2020).

Binge eating behaviors

Binge eating was defined as consuming an excessive amount of food with a sense of loss of control over eating (APA, Citation2013). Two items from the EDE-Q were employed to measure the presence of binge eating behaviors: item 13 (“how many times have you eaten what other people would regard as an unusually large amount of food [given the circumstances]?”) and item 14 (“… on how many of these times did you have a sense of having lost control over your eating [at the time that you were eating]?”). Participants were required to state the number of times they have taken part in these behaviors over the past 28 days. Given a binge episode is characterized by both the loss of control and the consumption of a large amount of food (APA, Citation2013), participants who scored 0 on one or both items were coded as 0 = no engagement, and participants who reported more than 1 on both items were coded as 1 = engagement.

Restraining behaviors

Restraining behaviors were defined as deliberately restricting caloric intake (APA, Citation2013). Item 2 (“on how many of the past 28 days have you gone for long periods of time [8 waking hours or more] without eating anything at all in order to influence your shape or weight?”) of the EDE-Q was employed to measure participant levels of restraining behaviors. This approach has been used in previous literature (Nagata, Murray, et al., Citation2020) and is further justified by the current DSM-5 criteria for the restricting subtype (APA, Citation2013). On a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (no days) to 6 (every day), participants stated the number of days they have engaged in this behavior over the past four weeks. To calculate scores for restraining behaviors, this item was coded as 0 = no engagement for those who selected 0 days, or 1 = engagement for those who selected between 1 and twenty-eight days (i.e., indicating the presence of restraint).

Compensatory behaviors

Compensatory behaviors were defined as inappropriate behaviors intended to prevent weight gain (APA, Citation2013). Three items from the EDE-Q were used to measure participant levels of compensatory behaviors: item 16 (“how many times have you made yourself sick [vomit] as a means of controlling your shape or weight?”), item 17 (“how many times have you taken laxatives as a means of controlling your shape or weight?”) and item 18 (“how many times have you exercised in a “driven” or “compulsive” way as a means of controlling your weight, shape or amount of fat, or to burn off calories?”). This particular approach to measuring compensatory behaviors has been validated through previous research (Lavender et al., Citation2010; Nagata, Murray, et al., Citation2020). Participants were required to record the number of times they have taken part in these behaviors over the past 28 days. Due to the nature of these behaviors generally having the same underlying mechanisms in what people are trying to “achieve” (e.g., weight loss/compensating for the amount of food consumed; APA, Citation2013), the presence of any one behavior was required to be coded as engagement in compensatory behaviors. As such, to calculate scores, items were coded as 0 = no engagement, and 1 = engagement.

Bisexual discrimination

Bisexual discrimination was assessed using the Brief Version of the Anti-Bisexual Experiences Scale (Brief ABES; Dyar et al., Citation2019), an instrument that examines bisexual individuals’ distinctive experiences of discriminatory events. Comprising eight items, the Brief ABES contains three subscales that address various types of bisexual discrimination: instability stereotypes (e.g., bisexuality is an unstable or illegitimate sexual orientation), irresponsibility stereotypes (e.g., bisexual persons have a high sexual drive and are reckless in sexual encounters), and general hostility (e.g., negative emotions/feelings toward bisexual individuals). Participants responded to items on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (almost all of the time). Examples of questions include: “I have been alienated because I am bisexual” and “people have not taken my sexual orientation seriously, because I am bisexual.” Each item was administered twice; once referring to anti-bisexual experiences from heterosexual individuals, and once referring to anti-bisexual experiences from gay and lesbian individuals. Scores could range between 8 (indicating less frequent anti-bisexual discrimination) and 48 (indicating more frequent anti-bisexual discrimination). For this study, a total score was achieved by averaging responses across all subscales. Previously, this scale has illustrated excellent reliability with Cronbach’s α ranging between .81 and .94 across subscales (Brewster & Moradi, Citation2010; Dyar et al., Citation2019), as well as acceptable levels of convergent validity with the original ABES (Dyar et al., Citation2019). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was α = .93 for the full scale.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Andrews & Slade, Citation2001), a 10-item instrument designed to yield a global measure of an individual’s psychological distress over a four-week period. The K10 contains two subscales: depression (e.g., “In the past four weeks, about how often did you feel worthless?”) and anxiety (e.g., “In the past four weeks, about how often did you feel nervous?”). For the purposes of this study, the global measure was used to calculate total distress, an approach supported throughout the literature (Kessler et al., Citation2002; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., Citation2018). On a five-point Likert-type scale, participants responded to each item ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Total scores were calculated by adding each item’s score and could range between 10 (indicating low levels of distress) and 50 (indicating severe levels of distress). Previously, the K10 has shown adequate criterion and convergent validity (Cornelius et al., Citation2013; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., Citation2018), as well as consistent reliability (α = .93) across major sociodemographic subsamples (Baxter et al., Citation2021; Kessler et al., Citation2002). In this study, excellent internal consistency was found (α = .92).

Procedure

This study was approved by the Victoria University Ethics Committee (approval number HRE21-029). Participants were recruited via convenience sampling, where survey advertisements were distributed via Prolific (an online survey platform), the research team’s social media, and several LGBTQIA + organizations. Potential participants clicked on the study link which directed them to the Qualtrics-hosted survey, where they read the participant information sheet. The information sheet explained that the purpose of this study was to better understand body image in sexual minority women; that participation was voluntary and would take 10–15 min; of their rights to withdraw at any time; and that their responses would be anonymous. If participants met the inclusion criteria and agreed to the terms of the study, they were asked to provide their consent via the forced entry checkbox “Yes, I consent.” Those who did not wish to continue were instructed to exit the survey. From there, participants completed the survey, responding to demographics and measures of disordered eating, bisexual discrimination, and psychological distress. As part of the larger project, participants also completed other social media and body image-related measures. Upon conclusion of the survey, participants were thanked for their time and participation and were provided with the details of the chief investigator and several support services (i.e., The Butterfly Foundation, LifeLine, and QLife) in case of concerns related to the research topic.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlational analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27.

Descriptive statistics and correlational analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. Mediation analyses were chosen to test a theoretical causal model of the relationship between bisexual discrimination and DEBs, although it is important to note that due to the cross-sectional nature of the data and lack of experimental manipulation, no causality can be inferred or is implied within the current study. The approach was specifically chosen to align with the theoretical premise of Hatzenbuehler (Citation2009). Following the recommendations of Feingold et al. (Citation2019), maximum likelihood estimation models with logit link for pathways including the binary predictor were used to analyze the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationships between bisexual discrimination and binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviors in bi + women. All mediation analyses were conducted using MPLUS (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017). Ten thousand bootstrap re-samples calculated the direct and indirect effects of bisexual discrimination on outcomes of disordered eating, generating three mediation models. Finally, the threshold for significance was set at an alpha of .05.

Analyses for the larger portion of this study were pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9vfks/). This specific study was not preregistered. Of note, however, the outcomes examined in this study were not examined in any of the previous literature.

Results

Data cleaning and preliminary analyses

All data were cleaned and screened through SPSS version 27. No participant was missing more than five per cent of the data at the item level, and Little’s MCAR test also revealed data were missing completely at random (p = .97). As such, the expectation maximization technique for missing data was conducted; an appropriate method for handling smaller amounts of data missing at random (Field, Citation2018; Fox-Wasylyshyn & El-Masri, Citation2005). Preliminary analyses were then performed to ensure no violations of the assumptions of mediation had occurred. Assumptions of univariate normality (as indicated by histograms, z-scores, and skewness and kurtosis statistics), multivariate normality (as indicated by Mahalanobis distance, Cook’s distance, leverage, and df betas), independence of errors, multicollinearity (as indicated by tolerance and VIF) and linearity of the logit (as indicated by non-significant interaction terms between the logistic term and predictor variables) were all met (Field, Citation2018; Hosmer et al., Citation2013). As an additional preliminary analysis, percentage counts were employed to determine the number of participants who did and did not engage in DEBs. Sample differences are presented in .

Table 2. Sample Differences in the Presence of Disordered Eating Behaviors (n = 250).

indicates that binge eating behaviors recorded the highest percentage of participant engagement, followed by restraint and compensatory behaviors. It is important to note, however, that a higher number of participants appeared to report no engagement in disordered eating among all three behavioral outcomes. Before mediation analyses were performed, bivariate correlations were examined to identify the strength, significance, and directionality of the focal variables (see ). Effect sizes are described using Cohen’s (Citation1988) benchmark for small (r ≥ .10), medium (r ≥ .30) and large (r ≥ .50).

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Variables of Interest.

shows that all outcomes of disordered eating were significantly and positively related with both bisexual discrimination and psychological distress. The relationships between the predictor variables and outcomes of disordered eating were all in expected directions.

Main analyses

Binge eating outcome

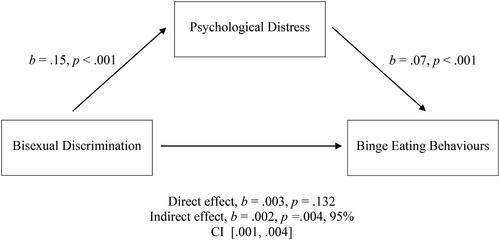

Mediation analysis using maximum likelihood estimation was used to investigate whether the relationship between bisexual discrimination and binge eating behaviors was mediated by psychological distress. In the first model, which regressed the independent variable on the mediator, bisexual discrimination was significantly and positively related to psychological distress, b = .154, SE = .037, p < .001, 95% CI [.081, .226] (pathway a). In the second model, which regressed the independent variable and mediator onto the dependent variable, only psychological distress, b = .07, SE = .02, p < .001, 95% CI [.04, 10], Odds Ratio (OR) 1.075 (pathway b; which corresponds to an 8% increase in binge eating for every unit increase in psychological distress, with 63.45% for every standard deviation increase) was significantly and independently related to binge eating behaviors—bisexual discrimination was not a significant predictor, b = .003, SE = .001, p = .132, 95% CI [−0.002, .005] (pathway c’), Odds Ratio (OR) 0.986. The bootstrap CI with 10000 resamples showed the indirect effect coefficient was significant, b = .002, SE = .001, p=.005, 95% CI [.001, .004]. As such, psychological distress was a complete mediator in the relationship between bisexual discrimination and binge eating behaviors in bi + women (see ).

Restraint outcome

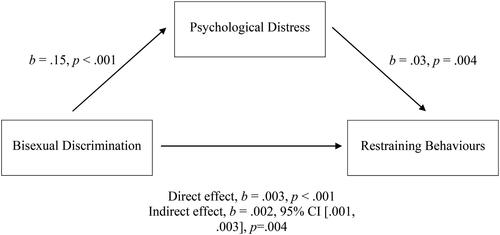

The mediation model described for the restraint outcome was conducted to determine whether the relationship between bisexual discrimination and restraint was mediated by psychological distress. In the first model, which regressed the independent variable on the mediator, bisexual discrimination was significantly and positively related to psychological distress, b = .154, SE = .037, p < .001, 95% CI [.081, .226] (pathway a). In the second model, which regressed the independent variable and mediator onto the dependent variable, both psychological distress, b = .100, SE = .020, p < .001, 95% CI [.064, .142], OR 1.105 (pathway b; which corresponds to an 10.5% increase in restraining for every unit increase in psychological distress, with 147.32% for every standard deviation increase) and bisexual discrimination, b = .033, SE = .011, p = .002, 95% CI [.012, .057], OR 1.031 (pathway c’; which corresponds to a 3.1% increase in restraining for every unit increase in bisexual discrimination, with 43.49% for every standard deviation increase) were significantly associated with restraining eating behaviors. The indirect effect was also significant, b = .002, SE = .001, 95% CI [.001, .003], p = .004. As both the direct and indirect effects were significant, the relationship between bisexual discrimination and restraint was partially mediated by psychological distress (see ).

Compensatory behaviors outcome

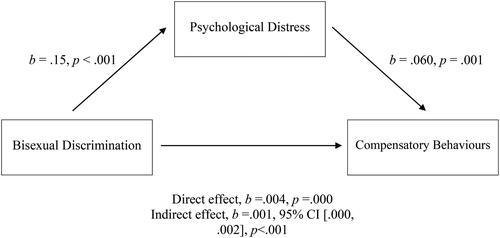

The final mediation model examined whether the relationship between bisexual discrimination and compensatory behaviors was mediated by psychological distress. The first regression model, which regressed the independent variable on the mediator, revealed bisexual discrimination was significantly and positively related to psychological distress, b = .154, SE = .037, p < .001, 95% CI [.081, .226] (pathway a). In the second regression model, which regressed the independent variable and mediator onto the dependent variable, both psychological distress, b = .060, SE = .018, p = .001, 95% CI [.027, .098], OR 1.062 (pathway b; which corresponds to a 6.2% increase in restraining for every unit increase in psychological distress, with 52.45% for every standard deviation increase) and bisexual discrimination, b = .038, SE = .010, p < .001, 95% CI [.019, .059], OR 1.039 (pathway c’; which corresponds to a 3.9% increase in compensatory behaviors for every unit increase in bisexual discrimination, with 54.72% for every standard deviation increase) were significantly related to compensatory behaviors. The indirect effect was significant, b = .001, SE <.001, 95% CI [.003, .018], p = .025. As both the direct and indirect effects were significant, the relationship between bisexual discrimination and compensatory behaviors was partially mediated by psychological distress (see ).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine whether psychological distress explained the relationships between bisexual discrimination and disordered eating behaviors in bi + women. Bisexual discrimination was first hypothesized to be associated with all outcomes of disordered eating. At the bivariate level, this was supported: higher perceived bisexual discrimination was significantly and positively related to higher binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviors in bi + women. Moreover, the hypothesis that psychological distress would explain the relationships between bisexual discrimination and binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviors in bi + women was also supported. Bisexual discrimination and binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviors were all indirectly related through psychological distress, with the relationship between bisexual discrimination and binge eating becoming non-significant when considering the role of psychological distress. The following implications for disordered eating in bi + women will be discussed in reference to each behavioral outcome.

Bisexual discrimination and binge eating behaviors were indirectly associated through psychological distress. The current finding corroborates previous assertions in the literature which suggest that general (psychological) distress is a significant predictor of binge eating behaviors in sexual minority women (SMW; Arcelus et al., Citation2018; Bayer et al., Citation2017). Moreover, this outcome also supports and broadens the findings of Mason and Lewis (Citation2019), who found heighented distress partly elucidated the link between sexual discrimination and the presence of disordered eating symptoms in lesbian women. The current study contributes a distinct angle by focusing on bi + women. As such, the current study identifies a specific source of psychological distress that may relate to the engagement of binge eating behaviors in bi + women explicitly: bisexual discrimination. An explanation for this particular finding comes from the psychological mediation framework of minority stressors (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009), which states that external stressors contribute to negative psychological processes, and in turn, leads to maladaptive coping. In the present study, the findings suggest that experiences of bisexual discrimination may alter bi + women’s cognitive and coping processes in harmful ways, which may subsequently increase their psychological distress (Schwartz et al., Citation2016). As such, the maladaptive coping that results from this heightened distress is suggested to be binge eating behaviors, which may ultimately provoke an immediate emotional relief in bi + women. Longitudinal research, however, is needed to test the temporality of these relationships. These predictions are consistent with Bayer et al. (Citation2017), who found binge eating behaviors in SMW may serve as a form of comfort eating: eating provoked by negative affect (Finch & Tomiyama, Citation2015). Therefore, bi + women may use binge eating behaviors to suppress the negative emotions attached to their elevated psychological distress (Ahorsu et al., Citation2020; Ball & Lee, Citation2000) which may surface, in part, from their encounters with bisexual discrimination.

To the author’s knowledge, the current study may be one of the first to include bisexual discrimination, psychological distress, and binge eating behaviors in one specific model. Accordingly, this finding illustrates the important role psychological distress may play in the relationship between bisexual discrimination and binge eating behaviors in bi + women. However, it should be noted that the overall variance explained in binge eating behaviors by bisexual discrimination was small, indicating there are other predictors that better explain binge eating in bi + women, which were not included in this study. Future research may wish to examine the role of other predictors relevant to bi + women, that have also been linked with binge eating episodes such as self-objectification (Schaefer & Thompson, Citation2018) and depression and anxiety (Rosenbaum & White, Citation2015).

Next, psychological distress partially explained the relationship between bisexual discrimination and restraining eating behaviors in bi + women. This result supports previous research that has identified sexual orientation discrimination as a potential factor contributing to maladaptive behaviors in sexual minority individuals (Calzo et al., Citation2017; Mason et al., Citation2018; Simone et al., Citation2020). Additionally, this finding is also somewhat consistent with other studies that have found restraint/restrictive eating is an emotional reaction to distress (Konstantellou et al., Citation2019) and may serve as an attempt to cope with feelings of uncertainty and negative emotions (Espeset et al., Citation2012). Thus, by extending upon these findings (Calzo et al., Citation2017; Konstantellou et al., Citation2019; Mason et al., Citation2018; Simone et al., Citation2020), the current study suggests that bi + women may use restraint as a form of maladaptive coping in response to their elevated distress, which may arise from experiences of bisexual discrimination. Moreover, this relationship between bisexual discrimination, psychological distress, and restraint is further supported by Hatzenbuehler’s (Citation2009) mediation model of minority stressors. This finding was, to some degree, anticipated by research exploring disordered eating in the LGBTQIA + population (Arcelus et al., Citation2018; Parker & Harriger, Citation2020). Arcelus et al. (Citation2018), and Parker and Harriger (Citation2020) mutually suggested that sexual minority individuals may use disordered eating, particularly restraint, to counteract prejudicial and stigmatizing experiences, perhaps as an effort to regain a sense of control (Ball & Lee, Citation2000). Consistent with these predictions, the present findings may then suggest that bisexual discrimination may increase the tendency for bi + women to perceive minimal control over their social lives (Ball & Lee, Citation2000; Meyer, Citation2003). Considering research has found strong correlations between a perceived lack of control and high levels of distress and anxiety (Parker & Harriger, Citation2020; Shi et al., Citation2019), this research thus indicates that bi + women may use restraint eating behaviors to regain control in their lives (Beukes et al., Citation2009), although the temporal nature of these relationships should be established with longitudinal research. As such, the associated psychological distress may also be alleviated temporarily by using these sorts of behaviors (Arcelus et al., Citation2018).

It is important to note that psychological distress only partially explained the relationship between bisexual discrimination and restraint in bi + women. This finding indicates that other factors may also serve as relevant variables in the relationship between bisexual discrimination and restraint. Hatzenbuehler’s (Citation2009) model suggests that external stressors can contribute to general psychological processes, such as rumination and negative self-schemas. Although psychological distress is a variable indicative of some of these processes, other specific variables, such as anxiety and low self-esteem, may also be examined as mediators between bisexual discrimination and restraining eating behaviors in future work. Considering anxiety and low self-esteem have been identified as both elevated in bi + women and contributors to restrictive eating (Timmins et al., Citation2019), exploration within the context of bisexual discrimination is thus warranted. Additionally, the relationship between bisexual discrimination and restraint was small to medium, and thus other explanatory variables, such as those discussed in relation to binge eating behavior, may be of interest in future research.

Lastly, bisexual discrimination and compensatory behaviors were indirectly related through psychological distress in bi + women. As the relationship remained significant after considering psychological distress, other potential variables may explain the relationship between discrimination and compensatory behavior engagement in bi + women. For example, low self-esteem may have also contributed to this relationship, considering it has been identified with both Hatzenbuehler’s (Citation2009) mediation model and linked to compensatory behaviors in general populations (Brechan & Kvalem, Citation2015). Nevertheless, similar to the binge eating and restraint outcomes, this finding is consistent with research highlighting that bisexual discrimination may be an anxiety-inducing situation that may increase distress (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009; Meyer, Citation2003) and may also lead bi + women to partake in compensatory behaviors as a form of maladaptive coping (Colledge et al., Citation2020; Frayn et al., Citation2018). This finding is of great importance, considering prior research has suggested that individuals who engage in purging behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives/diuretics) are at utmost risk for the development of bulimia nervosa (Stiles-Shields et al., Citation2012). In addition, other studies have found that engaging in compensatory eating behaviors may lead to increased morbidity and suicide ideation (Schaumberg et al., Citation2014; Warne et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the present research posits that bisexual discrimination experienced by bi + women may ultimately elicit these adverse outcomes. It is also worth noting, however, that similar to the models examining binge eating and restraint, the relationship between bisexual discrimination and compensatory behaviors was small to medium. Thus other predictors of compensatory behaviors in bi + women remain important to explore.

Although not the primary focus of this study, the findings indicated that it is relatively common for bi + women to engage in DEBs. Whereas examining the frequency of behaviors was beyond the scope of this research, it was evidenced that over one-third of participants had engaged in binge eating, restraint, or compensatory behaviors within the past month. This is consistent with previous estimates that have found similar percentages of bisexual women reporting disordered eating symptoms (Chmielewski & Yost, Citation2013; Parker & Harriger, Citation2020) and further lend credence to other studies that have suggested bisexual women are at elevated risk of disordered eating compared to many other demographics (Dotan et al., Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2016). As such, this study supports the research literature suggesting that bi + women are a high-risk group for disordered eating, as well as highlighting bisexual discrimination as a potential intervention point to reduce the prevalence.

Practical implications

This research denotes the significance of attending to the roles of bisexual discrimination, psychological distress, and DEBs in bi + women’s lives. As such, the present findings offer a point of intervention for psychologists and other mental health professionals working alongside bi + women experiencing ED symptomology. Specifically, given this study posits bisexual discrimination as a potential contributor to disordered eating in bi + women, clinicians may wish to explore/address experiences of biphobia when these women present with disordered eating or body image concerns. By investigating these relationships, clinicians can deliver psychoeducation on the adverse effects of bisexual discrimination and suggest strategies for more adaptive methods of coping (e.g., seeking LGBTQIA + support; Craney et al., Citation2018). This way, the tendency to internalize behaviors presented as disordered eating, may therefore be replaced. Importantly, this also requires clinicians to create an environment where their clients can feel safe disclosing their sexual orientation and experiences of discrimination. Many women who are bi + may not immediately identify themselves as such and may be assumed to be heterosexual or lesbian depending on the gender of their partner. Therefore, it is recommended that clinicians do not assume sexual orientation without clarifying this with their clients. Furthermore, it is pivotal for practitioners and policymakers to develop interventions specific to their targeted audience for a successful outcome. With the current research, prevention strategies for DEBs in bi + women may be designed to include the influence of biphobia amidst considering other contributing factors, such as weight/shape concerns and self-esteem (Arcelus et al., Citation2018; Austin et al., Citation2013). These individual-level interventions may assist in lowering the disordered eating prevalence among a high-risk population.

However, considering the social aspect of bisexual discrimination, the current research also implies that change is imperative at a societal level. A recent campaign, Still Bisexual (Citation2019), is an important example of these efforts. Over two years, the American-based movement was able to improve health outcomes in bisexual individuals by raising public awareness, acceptance and understanding of bisexuality, which thus reduced the experience of biphobia. In addition to this, structural interventions are crucial to change many social environments in which stigma-inspired stressors, including bi + discrimination, may develop and proliferate, including workplaces (DeSouza et al., Citation2017) and higher-education settings (Formby, Citation2017). So, although psychologists and other mental health professionals may use this research to help mitigate disordered eating in bi + women, change is still undeniably required at a broader level.

Strengths, limitations and future research

This study has numerous strengths. To date, limited studies are yet to research bi + women as a distinct sexual orientation group in social research (Parker & Harriger, Citation2020). Instead, it is common for researchers to amalgamate bi + women with other SMW (Hazzard et al., Citation2020; Mason et al., Citation2018) or bi + males (Jhe et al., Citation2021; Matthews-Ewald et al., Citation2014; Shearer et al., Citation2015), consequently rendering their experiences indiscernible. Therefore, a substantial strength of the present study is the sole inclusion of bi + women and the focus on their unique experiences associated with disordered eating. Moreover, this study aimed to abide by the practice guidelines for researching and writing on bisexuality, which provide guidance on conducting research that will help bi + people rather than further stigmatizing the community (Barker et al., Citation2012). In doing so, the present findings reflect a sound evidence base about bisexuality and the bi + experience without bias and/or assumptions. Furthermore, to the author’s knowledge, this study stands as an inaugural attempt to test models for the relationships between bisexual discrimination, psychological distress and specific types of disordered eating within the bi + women demographic. Additionally, this study may be one of the only studies within Australia, and arguably beyond, that has recruited a respectably sized sample (n = 250) of bi + women in the body image/disordered eating field. Hence, this study extensively adds to the relative dearth of literature and elucidates the significance of focusing on such variables in the lives of bi + women.

However, the findings of the current study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Firstly, these findings may not be generalized to a wider population of bi + women in Australia, given the convenience sampling method utilized to recruit participants. Future work would benefit from using a random sampling technique to ensure accurate extrapolation and validation of these results. Second, the cross-sectional study design limits the establishment of the temporal and causal relationships between bisexual discrimination, psychological distress, and outcomes of disordered eating. Although we wished to test a mediation model to provide direction for future research, our findings are correlational only, and a longitudinal study design is required to further confirm and test the pathways suggested in this study. Third, this study only examined two variables as predictors of disordered eating in bi + women. Although these variables were selected with meticulous theoretical justification (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009; Meyer, Citation2003), results suggest there may be other predictors and mediators that contribute to the development of DEBs in bi + women. An important direction for future research would be to investigate other variables applicable to bi + women (i.e., rumination, self-objectification; Dotan et al., Citation2021; Holmes et al., Citation2020). A fourth limitation of this study was the selection bias in sampling, which may have led to an overrepresentation of ‘healthier members’ within this sexual orientation group. For example, individuals who do not accept themselves, or are yet to accept their bisexuality, may be less likely to contribute to a study that focuses entirely on bi + women, compared to those who do accept themselves (Ryan et al., Citation2010). Given self-acceptance is typically associated with better psychological adjustment (Meyer, Citation2003), this selection bias may have therefore underestimated levels of psychological distress within this sample. Finally, a limitation was the operationalization of the dependent variables. Disordered eating behaviors were examined as binary variables (i.e., engaged or did not engage) and did not examine the frequency of behaviors, given the sample was not a clinical sample and was therefore not expected to have a high frequency of DEBs. As such, it cannot be certain whether the models predict more or less severe DEBs.

Conclusion

In summation, the present study provides significant data about disordered eating behaviors in bi + women. Of most importance, this is one of the first studies to report significant relationships between bisexual discrimination, psychological distress, and binge eating, restraint, and compensatory behaviors in bi + women. The findings of this study indicate that the psychological distress resulting from experiences of bisexual discrimination may ultimately play a key role in the occurrence of binge eating behaviors in bi + women. Moreover, the present results also demonstrate that although bisexual discrimination and restraint, and bisexual discrimination and compensatory behaviors are indirectly related through psychological distress, psychological distress does not explain the entire relationship. As such, it is implied that there are other variables contributing to these relationships that should be examined in future work. Nonetheless, this study offers novel insights concerning the health and well-being of bi + women, where findings may be deemed pivotal for clinicians, practitioners, and policymakers to combat bisexual discrimination and its related harm. Future researchers should be encouraged to use this study as an offset to conduct longitudinal studies to verify these findings.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by Victoria University Ethics Committee (approval number: HRE21-029). All participants provided informed consent to take part in this research.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jemima Croser, Gabriela Fernandez-Sulbaran, and Amanda Marazita for their assistance in data collection and survey design for the larger project. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Alan Feingold for sharing his expertise in MPLUS mediation analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available at https://osf.io/9vfks/

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mikayla E. Jones

Mikayla Jones completed her undergraduate studies in Psychology within the College of Health and Biomedicine at Victoria University. She was awarded First Class Honors upon completion of her Bachelor of Psychology (Honors) degree in 2022.

Jo R. Doley

Dr. Jo Doley is a researcher and lecturer in psychology within the College of Health and Biomedicine at Victoria University. They completed their undergraduate studies in psychology at Flinders University in 2014, and completed their PhD, which focused on stigma and eating disorders, at La Trobe University in 2018.

References

- Ágh, T., Kovács, G., Supina, D., Pawaskar, M., Herman, B. K., Vokó, Z., & Sheehan, D. V. (2016). A systematic review of the health-related quality of life and economic burdens of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 21(3), 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0264-x

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C., Imani, V., Griffiths, M. D., Su, J., Latner, J. D., Marshall, R. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). A prospective study on the link between weight-related self-stigma and binge eating: Role of food addiction and psychological distress. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(3), 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23219

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Andrews, G., & Slade, T. (2001). Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(6), 494–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x

- Arcelus, J., Fernádndez-Aranda, F., & Bouman, W. P. (2018). Eating disorders and disordered eating in the LGBTQ population. In L. K. Anderson, S. B. Murray, & W. H. Kaye (Eds.), Clinical handbook of complex and atypical eating disorders (pp. 327–343). Oxford University Press.

- Austin, S. B., Nelson, L. A., Birkett, M. A., Calzo, J. P., & Everett, B. (2013). Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US High School Students. American Journal of Public Health, 103(2), e16–22. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2012.301150

- Ball, K., & Lee, C. (2000). Relationships between psychological stress, coping and disordered eating: A review. Psychology & Health, 14(6), 1007–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008407364

- Bankoff, S. M., & Pantalone, D. W. (2014). Patterns of disordered eating behavior in women by sexual orientation: A review of the literature. Eating Disorders, 22(3), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2014.890458

- Barker, M., Yockney, J., Richards, C., Jones, R., Bowes-Catton, H., & Plowman, T. (2012). Guidelines for researching and writing about bisexuality. Journal of Bisexuality, 12(3), 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2012.702618

- Baxter, G. L., Tooth, L. R., & Mishra, G. D. (2021). Psychological distress in young Australian women by area of residence: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295(1), 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.037

- Bayer, V., Robert-McComb, J. J., Clopton, J. R., & Reich, D. A. (2017). Investigating the influence of shame, depression, and distress tolerance on the relationship between internalized homophobia and binge eating in lesbian and bisexual women. Eating Behaviors, 24(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.12.001

- Beukes, M., Walker, S., & Esterhuyse, K. (2009). The role of coping responses in the relationship between perceived stress and disordered eating in a cross-cultural sample of female university students. Stress and Health, 26(4), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1296

- Brechan, I., & Kvalem, I. L. (2015). Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eating Behaviors, 17(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.008

- Brewster, M. E., & Moradi, B. (2010). Perceived experiences of anti-bisexual prejudice: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021116

- Brewster, M. E., Velez, B. L., Esposito, J., Wong, S., Geiger, E., & Keum, B. T. (2014). Moving beyond the binary with disordered eating research: A test and extension of objectification theory with bisexual women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034748

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books.

- Calzo, J. P., Blashill, A. J., Brown, T. A., & Argenal, R. L. (2017). Eating disorders and disordered weight and shape control behaviors in sexual minority populations. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(8), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0801-y

- Cao, Z., Cini, E., Pellegrini, D., & Fragkos, K. C. (2022). The association between sexual orientation and eating disorders-related eating behaviours in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 31(1), 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2952

- Carter, L. W., Mollen, D., & Smith, N. G. (2014). Locus of control, minority stress, and psychological distress among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034593

- Chmielewski, J. F., & Yost, M. R. (2013). Psychosocial influences on bisexual women’s body image: Negotiating gender and sexuality. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684311426126

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Colledge, F., Cody, R., Buchner, U. G., Schmidt, A., Pühse, U., Gerber, M., Wiesbeck, G., Lang, U. E., & Walter, M. (2020). Excessive exercise—a meta-review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(1), 521572. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.521572

- Cornelius, B. L., Groothoff, J. W., van der Klink, J. J., & Brouwer, S. (2013). The performance of the K10, K6 and GHQ-12 to screen for present state DSM-IV disorders among disability claimants. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-128

- Craney, R. S., Watson, L. B., Brownfield, J., & Flores, M. J. (2018). Bisexual women’s discriminatory experiences and psychological distress: Exploring the roles of coping and LGBTQ community connectedness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(3), 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000276

- DeSouza, E. R., Wesselmann, E. D., & Ispas, D. (2017). Workplace discrimination against sexual minorities: Subtle and not-so-subtle. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 34(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1438

- Diemer, E. W., Grant, J. D., Munn-Chernoff, M. A., Patterson, D. A., & Duncan, A. E. (2015). Gender identity, sexual orientation, and eating-related pathology in a national sample of college students. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 57(2), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.003

- Dotan, A., Bachner-Melman, R., & Dahlenburg, S. C. (2021). Sexual orientation and disordered eating in women: A meta-analysis. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 26(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00824-3

- Dyar, C., Feinstein, B. A., & Davila, J. (2019). Development and validation of a Brief Version of the Anti-Bisexual Experiences Scale. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1157-z

- Dyar, C., Lytle, A., London, B., & Levy, S. R. (2017). An experimental investigation of the application of binegative stereotypes. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(3), 314–327. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000234

- Erskine, H. E., Whiteford, H. A., & Pike, K. M. (2016). The global burden of eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(6), 346–353. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000276

- Espeset, E. M. S., Gulliksen, K. S., Nordbø, R. H. S., Skårderud, F., & Holte, A. (2012). The link between negative emotions and eating disorder behaviour in patients with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 20(6), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2183

- Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/t03974-000

- Feingold, A., MacKinnon, D. P., & Capaldi, D. M. (2019). Mediation analysis with binary outcomes: Direct and indirect effects of pro-alcohol influences on alcohol use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 94, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.12.018

- Field, A. P. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Finch, L. E., & Tomiyama, A. J. (2015). Comfort eating, psychological stress, and depressive symptoms in young adult women. Appetite, 95(1), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.07.017

- Formby, E. (2017). How should we “care” for LGBT + students within higher education? Pastoral Care in Education, 35(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2017.1363811

- Fox-Wasylyshyn, S. M., & El-Masri, M. M. (2005). Handling missing data in self-report measures. Research in Nursing & Health, 28(6), 488–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20100

- Frayn, M., Livshits, S., & Knäuper, B. (2018). Emotional eating and weight regulation: A qualitative study of compensatory behaviors and concerns. Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-018-0210-6

- Friedman, M. R., Dodge, B., Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Hubach, R. D., Bowling, J., Goncalves, G., Krier, S., & Reece, M. (2014). From bias to bisexual health disparities: Attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. LGBT Health, 1(4), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0005

- Frost, D. M., Lehavot, K., & Meyer, I. H. (2013). Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-013-9523-8

- Gigi, I., Bachner-Melman, R., & Lev-Ari, L. (2016). The association between sexual orientation, susceptibility to social messages and disordered eating in men. Appetite, 99(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.12.027

- Gordon, A. R., Austin, S. B., Pantalone, D. W., Baker, A. M., Eiduson, R., & Rodgers, R. (2019). Appearance ideals and eating disorders risk among LGBTQ college students: The being ourselves living in diverse bodies study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(2), S43–S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.096

- Hadland, S. E., Austin, S. B., Goodenow, C. S., & Calzo, J. P. (2014). Weight misperception and unhealthy weight control behaviors among sexual minorities in the general adolescent population. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 54(3), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.021

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441

- Hay, P., Girosi, F., & Mond, J. (2015). Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the Australian population. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0056-0

- Hazzard, V. M., Simone, M., Borg, S. L., Borton, K. A., Sonneville, K. R., Calzo, J. P., & Lipson, S. K. (2020). Disparities in eating disorder risk and diagnosis among sexual minority college students: Findings from the national Healthy Minds study. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(9), 1563–1568. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23304

- Holmes, S. C., DaFonseca, A. M., & Johnson, D. M. (2020). Sexual victimization and disordered eating in bisexual women: A test of objectification theory. Violence against Women, 27(11), 2021–2042. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220963902

- Hosmer, D. W., Jr., Lemeshow, S., & Sturdivant, R. X. (2013). Applied logistic regression. John Wiley & Sons. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrew-Cucchiara/publication/261659875_Applied_Logistic_Regression/links/542c7eff0cf277d58e8c811e/Applied-Logistic-Regression.pdf

- Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. G., Jr, & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

- Jhe, G. B., Mereish, E. H., Gordon, A., Woulfe, J. M., & Katz-Wise, S. L. (2021). Associations between anti-bisexual minority stress and body esteem and emotional eating among bi + individuals: The protective role of individual- and community-level factors. Eating Behaviors, 43(1), 101575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101575

- Jones, C. L., Fowle, J. L., Ilyumzhinova, R., Berona, J., Mbayiwa, K., Goldschmidt, A. B., Bodell, L. P., Stepp, S. D., Hipwell, A. E., & Keenan, K. E. (2019). The relationship between body mass index, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology in sexual minority women. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(6), 730–734. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23072

- Kamody, R. C., Grilo, C. M., & Udo, T. (2019). Disparities in DSM-5 defined eating disorders by sexual orientation among U.S. adults. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(2), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23193

- Kärkkäinen, U., Mustelin, L., Raevuori, A., Kaprio, J., & Keski-Rahkonen, A. (2017). Do disordered eating behaviours have long-term health-related consequences? European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 26(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2568

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Mereish, E. H., & Woulfe, J. (2016). Associations of bisexual-specific minority stress and health among cisgender and transgender adults with bisexual orientation. Journal of Sex Research, 54(7), 899–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1236181

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074

- Konstantellou, A., Hale, L., Sternheim, L., Simic, M., & Eisler, I. (2019). The experience of intolerance of uncertainty for young people with a restrictive eating disorder: A pilot study. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 24(3), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00652-5

- Lavender, J. M., De Young, K. P., & Anderson, D. A. (2010). Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q): Norms for undergraduate men. Eating Behaviors, 11(2), 119–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.09.005

- Levinson, C., & Brosof, L. (2016). Cultural and ethnic differences in eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 12(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573400512666160216234238

- Luk, J. W., Miller, J. M., Lipsky, L. M., Gilman, S. E., Haynie, D. L., & Simons-Morton, B. G. (2019). A longitudinal investigation of perceived weight status as a mediator of sexual orientation disparities in maladaptive eating behaviors. Eating Behaviors, 33(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.04.003