ABSTRACT

The Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., 2015) documented devastating information about the American Psychological Association (APA) and the profession of psychology in the United States, prompting a public apology and a formal commitment by APA to correct its mistakes (APA, 2015). In the current article, we utilize betrayal trauma theory (Freyd, 1997), including betrayal blindness (e.g., Freyd, 1996; Tang, 2015) and institutional betrayal (Smith & Freyd, 2014b), to understand and learn from APA’s behaviors. We further situate this discussion in the context of inequality, both within APA and in American society generally. We detail how the impact of APA’s institutional betrayals extended beyond the organization, its members, and the psychology profession, highlighting the potential for disproportionate harm to minorities, including those who were tortured; Muslims, Middle Easterners, Afghans, and non-Americans who were not tortured; and other minority individuals (Gómez, 2015d). Acknowledging, understanding, and addressing its institutional betrayals offers APA the opportunity to take meaningful corrective and preventive measures. We propose several institutional reparations, including making concrete changes with transparency and conducting self-assessments to inform further needed changes (Freyd & Birrell, 2013). By engaging in institutional courage, APA has the potential to grow into an ethical governing body that fulfills its mission to “advance the creation, communication and application of psychological knowledge to benefit society and improve people’s lives” (APA, 2016).

Organizations perpetrating harm through action or inaction on those who are dependent is nothing new. For instance, through racialized police brutality in the United States—including the public killing of African American men such as Michael Brown (Gómez & Freyd, Citation2014), Alton Sterling, and Philando Castile (Poniewozik, Citation2016) and the sexual assaults of 13 African American women (McClain, Citation2015; Philips, Citation2015)—police systems have garnered increased attention for this seemingly government-sanctioned terrorism against people in the United States. The construct of institutional betrayal (Smith & Freyd, Citation2013, Citation2014b) may help in understanding—and ultimately preventing and ameliorating—the abuses and harms perpetrated by institutions.

The Report to the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent Review Relating to APA Ethics Guidelines, National Security Interrogations, and Torture (Hoffman et al., Citation2015), more commonly known as the Hoffman Report, offered devastating information regarding the American Psychological Association’s (APA’s) collusion with the U.S. Department of Defense for the greater part of a decade following the 2001 terrorist attacks. APA’s role included finalizing an independent modification of its ethics code to be in contrast with the Nuremberg Ethic (e.g., Hoffman et al., Citation2015; Pope & Gutheil, Citation2009a, Citation2009b), engaging in willful ignorance by disregarding evidence that abusive interrogation techniques had been used and were likely still being used (Hoffman et al., Citation2015), and disparaging some individuals who spoke out against these injustices (e.g., American Association for the Advancement of Science, Citation2016).

These harms by APA are the latest in a long list of institutional betrayals perpetrated by institutions associated with the psychology and psychiatry professions. Although APA and other membership institutions have often behaved in socially responsible ways, they have also caused considerable harm. As detailed by Levine (Citation2015), other institutional betrayals by psychological and psychiatric organizations and professionals include pathologizing homosexuality and oppressing non-heterosexual Americans; using psychometric testing, including IQ tests, to justify the oppression and genocide of Native American populations; and enabling the subjugation of African Americans through erroneous disorders and diagnoses. Given that institutional betrayal may disproportionately affect minorities (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013), it is unsurprising that the aforementioned institutional betrayals—along with those detailed in the Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015)—differentially impacted societally marginalized individuals, including ethnic, religious, and/or national minorities. Therefore, acknowledging, addressing, correcting, and making amends for all of APA’s institutional betrayals would benefit from utilizing trauma-informed, psychologically rooted perspectives that incorporate both majority and minority viewpoints. We hope to offer one such perspective.

In the current article, we utilize the theoretical and empirical work from betrayal trauma theory (BTT; e.g., Freyd, Citation1996) as a foundation. As one theoretical framework for conceptualizing APA’s actions and inactions (Thomas, Citation2016), we then detail the construct of institutional betrayal (e.g., Smith & Freyd, Citation2014b), including the potential harm that was caused to the organization, its members, and the profession of psychology in the United States. Furthermore, we explore the potentially exacerbated harm to diverse minorities that these institutional betrayals may have caused. We additionally examine how these disparate harms may negatively impact the current and future state of APA. Finally, we detail institutional reparations, which are concrete, measurable steps that APA can take to address these institutional betrayals and prevent similar future harms.

BTT

BTT (Freyd, Citation1994, Citation1996, Citation1997, Citation2001) provides a conceptual framework for understanding the unique impact of traumas perpetrated by trusted and depended-on people and institutions (betrayal traumas) on posttraumatic functioning. Familial rape, childhood physical abuse perpetrated by a caregiver, and domestic violence are examples of betrayal traumas. According to BTT, traumas that are perpetrated in the context of a relationship in which the victim trusts and/or depends on the perpetrator will be remembered and processed differently than other traumas. BTT proposes that given the victim’s dependence on the perpetrator for survival and fulfillment of basic needs, the victim may need to ignore the betrayal in order to continue to engage in behavior that will preserve the necessary relationship with the perpetrator.

Although humans have evolved to be exceptional betrayal detectors (Cosmides, Citation1989), being aware of betrayal by a trusted and/or needed other may inspire emotional or behavioral withdrawal from the perpetrator and potentially threaten survival. Betrayal blindness, which involves remaining unaware of or forgetting the trauma, helps to ensure survival by inspiring attachment behavior. Substantial empirical support exists for BTT, suggesting that betrayal is a fundamental aspect of psychological trauma (e.g., Kelley, Weathers, Mason, & Pruneau, Citation2012). For instance, exposure to betrayal trauma has been associated with elevated posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity (Kelley et al., Citation2012); impaired cheater detector abilities (DePrince, Citation2005); physical health symptoms (Freyd, Klest, & Allard, Citation2005); depression, anxiety, panic, anger, and poor health functioning (Edwards, Freyd, Dube, Anda, & Felitti, Citation2012); suicidality (Edwards et al., Citation2012; Gómez & Freyd, Citation2013); hallucinations (Gómez & Freyd, Citation2016; Gómez, Kaehler, & Freyd, Citation2014); elevated rates of revictimization (DePrince, Citation2005; Gobin & Freyd, Citation2009); and intergenerational trauma (Hulette, Kaehler, & Freyd, Citation2011).

BTT identifies dissociation as one potential mechanism by which betrayal blindness occurs. Betrayal trauma has been linked with dissociation (DePrince et al., Citation2012; Gómez & Freyd, Citation2016; Gómez, Kaehler, et al., Citation2014; Gómez, Smith, & Freyd, Citation2014) and increased dissociative tendencies (Chu & Dill, Citation1990; DePrince, Citation2005). Furthermore, compared to low dissociators, high dissociators were found to have impaired memory for words associated with trauma but no impairment for neutral words under divided attention conditions, suggesting that dissociation may be the cognitive mechanism that facilitates betrayal blindness among survivors of betrayal trauma (DePrince & Freyd, Citation2001, 2004). Thus, betrayal appears to be an important component in understanding posttraumatic functioning.

Institutional betrayal

The concept of institutional betrayal arises from BTT (e.g., Freyd, Citation1996), expanding the scope of betrayal to acknowledge that institutions are often trusted or depended on in much the same way as individuals (Freyd, Citation2008; Platt, Barton, & Freyd, Citation2009; Smith & Freyd, Citation2013, Citation2014b). The trust individuals have in institutions is based on expectations that institutions will fulfill an important role in their lives—a religious institution providing a place of worship and community, an educational institution providing an environment conducive to learning and growth, or a health care institution providing a source of safe and effective treatment. When these expectations are violated and individuals instead find themselves harmed, institutional betrayal has occurred.

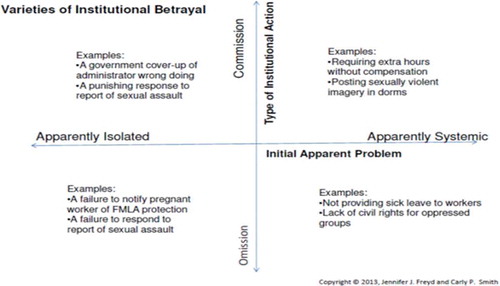

Institutional betrayal can happen through acts of commission or omission (e.g., Smith & Freyd, Citation2014b; see ). An institution can take actions that harm members (e.g., a church knowingly hires clergy with abuse allegations) or fail to take actions that could protect members (e.g., a church does not act on reports of clergy abuse). Institutional betrayal can also occur in ways that either are clearly systemic in nature or appear to be isolated incidents. Institutional policies often underlie systemic sources of institutional betrayal (e.g., lack of protection for individuals reporting abuse, arduous reparation processes); conversely, experiences that can be attributed to individuals’ behaviors can initially appear to be isolated events (e.g., receiving a curt e-mail in response to sharing a concern may appear to be an isolated incident, but all complaints of this nature may receive the same response).

Figure 1. Dimensions of institutional betrayal. FMLA = Family and Medical Leave Act . © Jennifer J. Freyd and Carly P. Smith. Reproduced by permission of Jennifer J. Freyd and Carly P. Smith. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

Measuring institutional betrayal requires inquiring about experiences that take any of these forms: an institution creating an environment in which harm is more likely, failing to prevent harm, making it difficult to report harm, covering up reports, or even punishing individuals for making such reports. These and other institutional actions and inactions are assessed through the Institutional Betrayal Questionnaire (Smith & Freyd, Citation2013), which has been applied in contexts ranging from universities (e.g., Smith & Freyd, Citation2013), to the military (Monteith, Bahraini, Matarazzo, Soberay, & Smith, Citation2016), to health care settings (Smith & Freyd, Citation2015). Empirical evidence of the impact of institutional betrayal includes psychological distress, such as anxiety, dissociation, and suicide attempts (Monteith et al., Citation2016; Smith & Freyd, Citation2013). Institutional betrayal also impacts trust in and engagement with the institution (Smith & Freyd, Citation2013, Citation2015).

As with betrayal traumas, perpetrators, victims, and bystanders of institutional betrayal are at risk for betrayal blindness (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013). In the context of institutional betrayal (e.g., Smith & Freyd, Citation2014b), betrayal blindness may take many forms, including an unwillingness to be aware of institutional wrongdoing, lack of sustained awareness of harmful institutional practices, failure to identify and correct institutional priorities and practices that inadvertently facilitate institutional betrayal, verbal denial of institutional betrayals, and retaliation against whistleblowers who speak up about betrayals occurring within their institution (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013; Gómez, Citation2015d; Smith & Freyd, Citation2014b). Amid allegations of APA’s involvement with so-called enhanced military interrogations, some APA members may have been unable to reconcile the fact that the institution they depended on for professional credibility could be involved in torture and human rights violations (Tang, Citation2015). Thus, APA and some of its members appear to have gone to great lengths to discredit and isolate whistleblowers (e.g., Pope, Citation2016a), thereby engaging in betrayal blindness and in effect protecting themselves from knowing about APA’s institutional betrayals.

APA’s institutional betrayals

Because institutional betrayal arises from violated expectations, any person who trusts and/or depends on the institution to meet those expectations is vulnerable to such betrayal. Institutional betrayal has most often been studied in individuals who have also experienced some traumatic event related to the institutional betrayal (e.g., a college student who first experiences sexual assault and subsequently institutional betrayal when the university fails to respond supportively); however, this is only one of the many forms institutional betrayal can take. The reaction of the professional psychological community to the events described in the Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015) provides a compelling example of how institutional betrayal manifests, even when the initial harm—in this case, potential involvement in torture and human rights violations—is not experienced firsthand by everyone.

The Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015) outlines numerous actions and inactions on the part of APA that can be conceptualized as institutional betrayals, such as collusion with the Department of Defense (Hoffman et al., Citation2015). Additional institutional betrayals included finalizing changes to the APA ethics code in 2002 that removed the stipulation that psychologists must place ethical considerations above legal, regulatory, and governing authority, which is in conflict with the Nuremberg Ethic (Pope, Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Pope & Gutheil, Citation2009a, Citation2009b). APA furthermore failed to respond to APA members’ concerns that this change was problematic (e.g., Tolin & Lohr, Citation2009) insofar that it allowed for a Nuremberg defense: the ability of psychologists to defend unethical acts by deferring to national laws that allow their behavior. In addition, in 2005, the Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security (also known as the PENS Task Force) supported the aforementioned change to the ethics code, failing to adopt international human rights standards regarding torture and instead using the more restrictive American definition (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Citation2016). According to the Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015), APA also failed to act on ethics complaints that alleged psychologists’ participation in torture while engaging in a dishonest public relations campaign that claimed that APA was protecting detainees. Finally, an overarching institutional betrayal of omission was APA’s apparent absence of action regarding the distinct possibility of psychologists’ involvement in torture (Soldz et al., Citation2014). As these institutional betrayals are diverse, ranging from apparent acts of omission to acts of commission that varied in appearing either isolated or systemic, the potential harm that APA caused is likely to be far reaching as well.

The harm of APA’s institutional betrayals

Harm to psychology, APA members, and clients

The psychology community and profession are affected by APA’s institutional betrayals, as APA serves many critical functions for its members. Some of these functions are providing professional cohesion and legitimacy, representing U.S. psychology, and setting educational and professional standards for psychologists. In addition, APA has taken brave and ethical stances on some matters, including support for same-sex marriage (APA, Citation2010b, 2011). When APA commits institutional betrayals and diverse individuals are harmed, APA betrays the psychology profession and all those who depend on it.

APA’s institutional betrayals perhaps most clearly impact members of APA; though impossible to quantify at this point, it is likely that many individuals have left the organization, either choosing not to renew their membership or publicly announcing their intention to leave. In many ways, this is an empowered response to betrayal; when one has the means (e.g., other social support, ways to maintain a professional identity as a psychologist) to leave an institution in which betrayal has occurred or is occurring, withdrawal is the surest way to avoid further betrayal. Yet leaving the institution is not only to protect against betrayal. Many APA members may have experienced a sense of shame at the actions of APA and/or their own failure to do more sooner; in fact, shame is a common response to betrayal and is associated with withdrawing from reminders of one’s perceived transgressions (Platt & Freyd, Citation2015). Those who do remain members may experience a sense of mistrust or disconnection from APA and be uncertain how to navigate continued relationships.

Finally, individuals who are in need of mental health care may be shaken by the revelations that APA committed these institutional betrayals of its members, detainees, and the general public. Before people form opinions of the trustworthiness of their therapists, they may derive information about the safety of the therapeutic relationship from the professional ethics that are meant to serve as safeguards (Heimer, Citation2001). To the extent that individuals seeking mental health care are aware of the actions of APA—for example, as published in The New York Times (Risen, Citation2015) or even the Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015)—their willingness to be trusting may depend on the ability of psychologists to discuss their own reactions to the institutional betrayal they experienced.

Harm to minorities

APA’s harms to psychology and individuals who need mental health care are costly. However, equally as important is the harm of institutional betrayal that may be disproportionately brought to bear on minorities (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013; Levine, Citation2015). In relation to the findings in the Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015), the primary victims of APA’s institutional betrayals have not been those individuals who enjoy higher societal status: White, wealthy, educated Americans. Instead, those who have endured the greatest harm from APA’s collusion with the Department of Defense—as detailed by the Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015)—are those individuals of lower status who were not protected from torture by an organization that represents a healing profession. These people endured low societal status in the United States as foreign nationals who were predominantly ethnic and religious minorities (Middle Eastern, Afghan, Muslim; Gómez, Citation2015d). U.S. psychology organizations, including the American Middle Eastern/North African Psychological Network (Citation2015), the Asian American Psychological Association (Pituc, Citation2015), the Association of Black Psychologists (Citation2015), the National Latina/o Psychological Association (Citationn.d.), and the Society of Indian Psychologists (Morse et al., Citation2015), have condemned APA for its lack of protection of minorities in this context. Though not every minority community was victimized, APA’s role may be re-traumatizing, as it may remind diverse minority groups of past institutional and governmental abuses (e.g., APA, Citation2015; Society of Indian Psychologists, Citation2015). Though some members of APA undoubtedly were concerned about detainees because of their minority statuses, it appears that APA’s larger infrastructure did not prioritize protecting these individuals as minorities within the context of discrimination and oppression in the United States following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Because of inequality, the effects of institutional betrayal may be uniquely harmful to some minorities, particularly those of Middle Eastern, North African, and/or Muslim backgrounds (American Middle Eastern/North African Psychological Network, Citation2015). First, minority groups already must contend with the stress of oppression and discrimination in the United States. This may be particularly strong for Middle Eastern, North African, Arab, and/or Muslim Americans in post-9/11 American society. In a study of Muslim Americans, perceived discrimination was related to subclinical paranoia and increased vigilance (Rippy & Newman, Citation2006). In addition, in a sample of Arab American adults, perceived post-9/11 abuse was associated with higher psychological distress and worse health outcomes (Padela & Heisler, Citation2010). Finally, following 9/11, Arab Americans may have higher levels of depression and anxiety compared to other minority groups (Amer & Hovey, Citation2012).

For ethnic minorities generally, discrimination is associated with increased rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (Pole, Best, Metzler, & Marmar, Citation2005). Race-related stress has been found to be a stronger risk factor for psychological distress than other stressful life events among African Americans (Utsey, Giesbrecht, Hook, & Stanard, Citation2008). Physical health can also suffer from race-related stress. Sims and colleagues (Citation2012) found that among African Americans, lifetime experiences of racism and the perceived burden of the incidents were associated with a greater prevalence of hypertension. Furthermore, because of discrimination, minorities may experience increased rates of institutional betrayal (Gómez, Smith, et al., Citation2014). The experience of institutional betrayal may compound the preexisting stress of discrimination, not only by adding to the overall load of stress but also by assuming a more harmful meaning when associated with oppression.

Second, this potentially more harmful meaning may lead to exacerbated cultural mistrust of dominant culture systems and institutions, including the profession of psychology. Cultural mistrust is a construct used to describe a mistrust of Euro-Americans among African Americans due to experiences with racism and oppression (Terrell & Terrell, Citation1981); cultural mistrust also may be applicable to other minority groups. Cultural mistrust is distinguished from paranoia, as the former is an understandable and even self-protective response to oppression (Whaley, Citation2001). Cultural mistrust has most often been studied with regard to its impact on counseling relationships but has also been found to affect other health care settings. Benkert, Peters, Clark, and Keves-Foster (Citation2006) found that cultural mistrust mediates the relationship between perceived racism and health care satisfaction among African Americans. With APA’s institutional betrayals, justified cultural mistrust of APA, the psychology profession, psychological research, and mental health care may further negatively impact minorities.

Harm to APA itself

According to BTT (e.g., Freyd, Citation1997), reactions to betrayal include confronting the betrayer, withdrawing from the betrayer, or engaging in betrayal blindness. When the perpetrator is an institution that represents U.S. psychology, withdrawal by diverse minority individuals has the potential to be costly. As evidenced by the process of the PENS Task Force (Hoffman et al., Citation2015), singular perspectives can foster lack of innovation, limited insight, groupthink, and overreliance on dominant perspectives. In contrast, fostering, as opposed to simply tolerating, diversity of thoughts, experience, and backgrounds can unveil both different solutions and new lines of inquiry that benefit a wide range of individuals and situations, as scientific knowledge is derived within social dynamics and cultures (Isler, Citation2015).

Examples of contributions to psychology from underrepresented and minority perspectives are numerous (e.g., Bryant-Davis, Citation2005; Duh et al., Citation2016; Eberhardt, Davies, Purdie-Vaughns, & Johnson, Citation2006; Gómez, Citation2015a). Racial, ethno-cultural, class, religious, and other forms of diversity strengthen scientific inquiry by providing multiple lenses through which to explore psychological phenomena. Thus, the threat of disengagement as a result of APA’s institutional betrayals includes losing the benefit of diversity by scholars choosing not to contribute their work, talent, and expertise to APA journals, conferences, and divisions; doctoral programs focusing their energies on receiving alternative accreditation, such as Psychology Clinical Science Accreditation System (Citation2011); scholars choosing to leave the field of psychology; and scholars choosing not to pursue degrees in psychology. The harm of the potential exodus from APA and/or the field of psychology has yet to be measured. Nevertheless, there is potential for the field—and ultimately the individuals, groups, and systems that psychology serves—to sustain loss from minorities’ withdrawal.

Institutional reparations

The Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015) outlined devastating details of APA’s actions and inactions regarding ethics, human rights, and the protection of detainees (APA, 2015; Gómez, Citation2015d; Hoffman et al., Citation2015), with its behavior being described as a cover-up (Brand & McEwen, Citation2016). With these institutional betrayals by the U.S. governing body of psychology, it would be easy to focus all attention on the harm APA has caused. However, APA’s ability to betray is matched by its opportunity to repair and ultimately better itself through institutional reparations, which are corrective and reparative institutional actions that both make amends for wrongdoings and serve as preventive measures against future injustices. With pro–human rights endeavors (e.g., same-sex marriage; APA, 2011), APA has demonstrated its ability to fight for equality, even when controversial. Furthermore, following the release of the Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015), APA swiftly engaged in some institutional reparations (Gómez, Citation2015d), including developing a panel to review APA’s ethics policies (Anton, McDaniel, & Kaslow, 2015).

Although this is a good beginning for APA, we further recommend the following institutional reparations: operating with transparency (Gómez, Smith, et al., Citation2014; Smith & Freyd, Citation2014b); conducting self-assessments (Freyd, Citation2014; Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013; Gómez, Smith, et al., Citation2014; Smith & Freyd, Citation2014b), including assessing measurable progress (Gómez & Freyd, Citation2014; Pope, Citation2016b), priorities and institutional culture (Gómez, Citation2015d), and the potential for additional institutional betrayals (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013; Gómez, Citation2015d); bearing witness to victims’ harms (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013; Platt et al., Citation2009; Smith, Gómez, & Freyd, Citation2014); acknowledging wrongdoing (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013); apologizing (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013; Gómez, Smith, et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2014); correcting and/or retracting false statements (Pope, Citation2016b); developing and implementing protocols (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013) for holding individuals accountable (Gómez, Citation2015c; Pope, Citation2015); educating individuals about institutional betrayal and betrayal blindness (Freyd & Birrell, Citation2013); complying with laws (Gómez, Smith, et al., Citation2014); and incorporating social justice in all endeavors (Gómez, Smith, et al., Citation2014). lists these institutional reparations, gives examples of each, and includes some verifiable outcomes of these actions, thus providing an avenue for needed genuine change (Soldz & Reisner, Citation2015) to occur within the organization. With institutional courage, APA can engage in institutional reparations, with the status of not-yet-completed institutional reparations being reported and newly created institutional reparations being added.

Table 1. Introductory institutional reparations checklist.

As with addressing sexual violence on college campuses (Gómez, Citation2015b), equality must be at the forefront of all facets of APA’s processes and policies. Formal diversity committees or divisions are not sufficient in addressing the inequality that abounds in American society and resides in U.S. institutions, including APA. Furthermore, discussions of oppression and its effects should not be relegated solely to professional settings (Lorde, Citation2007), such as specialized conference proceedings and peer-reviewed journals; the reality and implications of inequality should influence concrete change and must be embraced by the whole of APA, including its most powerful structures and leaders. Finally, to regain trust, institutional reparations and outcomes must be meaningful and verifiable. For instance, in 2008, APA appeared to take a stance against torture by passing an anti-torture referendum that was voted for by its members; however, this referendum was excluded from the ethics code and thus unenforceable (Pope & Gutheil, Citation2009a). By holding a standard of needing evidence as proof of change, APA can avoid the errors of professing good intent while action and results are absent (Pope, Citation2016b).

Concluding thoughts

The Hoffman Report (Hoffman et al., Citation2015) illustrates the abuse and injustices that powerful institutions can perpetrate against all those who depend on them. Institutions are structures with history, culture, and policies. Institutions are vulnerable to both conflicts of interest and influence from more powerful organizations. It is important to note that institutions are also composed of individuals. It is the individuals who have the power and duty to change institutions for the better. It is the individuals who can use betrayal as the impetus to bring about such change (Smith & Freyd, Citation2014a). With the revelations of APA’s actions and inactions, the challenge for members of the psychology community is to reject engaging in betrayal blindness at both institutional and individual levels (Tang, Citation2015) through self-examining their own roles in both what happened in the past and what will happen in the future. Psychologists and psychologists-in-training can take ownership of their roles in preventing similar injustices from reoccurring by either confronting the source of institutional betrayal and continuously demanding better or withdrawing from the organization. APA’s actions and inactions should serve as reminders that critical thinking about institutional actions and decisions is vital, regardless of how prestigious an organization may be (Pope, Citation2011a).

Amid the backlash over the release of the Hoffman Report (e.g., Bolgiano & Taylor, Citation2015; for a discussion, see Eidelson, Citation2016) there exists the potential for future institutional betrayals. However, parallel to that possibility is the opportunity for APA to demonstrate institutional courage through being true to its stated mission (APA, 2016) and working to protect those whom the psychology profession serves, including but not limited to minority psychologists, clients, research participants, students, and detainees. By being held accountable by empowered individuals who refuse to engage in betrayal blindness, APA has an opportunity to make fundamental change that will ultimately benefit those who have been so deeply betrayed.

References

- Amer, M. M., & Hovey, J. D. (2012). Anxiety and depression in a post-September 11 sample of Arabs in the USA. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(3), 409–418. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0341-4

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2016, February 8). AAAS Scientific Freedom and Responsibility Award goes to psychologist Jean Maria Arrigo. Retrieved from http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2016-02/aaft-asf020816.php

- American Middle Eastern/North African Psychological Network. (2015, August 14). Open letter to the American Psychological Association and the psychological community by the American Middle Eastern/North African (MENA) Psychological Network. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/MENAletter

- American Psychological Association. (2010a). American Psychological Association amends ethics code to address potential conflicts among professional ethics, legal authority and organizational demands. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2010/02/ethics-code.aspx

- American Psychological Association. (2010b). American Psychological Association reiterates support for same-sex marriage. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2010/08/support-same-sex-marriage.aspx

- American Psychological Association. (2011). Resolution on marriage equality for same-sex couples. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about/policy/same-sex.aspx

- American Psychological Association. (2015, July 10). Press release and recommended actions: Independent review cites collusion among APA individuals and Defense Department officials in policy on interrogation techniques. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2015/07/independent-review-release.aspx

- American Psychological Association. (2016). American Psychological Association: About APA. Retrieved from www.apa.org/about/

- Anton, B. S., McDaniel, S., & Kaslow, N. (2015, December 18). Year-end summary of APA responses to the independent review. Personal e-mail to American Psychological Association members.

- Association of Black Psychologists. (2015). ABPsi responds to the Hoffman Report. Retrieved from http://us6.campaign-archive1.com/?u=c53d7652a5d16356cf47880f2&id=17ffce76f8&e=262726b81d

- Benkert, R., Peters, R. M., Clark, R., & Keves-Foster, K. (2006). Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98, 1532–1540.

- Bolgiano, D. G., & Taylor, J. (2015, August 7). Honi soit qui mal y pense: Evil goings on behind the American Psychological Association Report on Interrogation. Retrieved from http://psychcoalition.org/5/post/2015/08/honi-soit-qui-mal-y-pense.html

- Brand, B. L., & McEwen, L. (2016). Ethical standards, truths, and lies. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(3), 259–266. doi:10.1080/15299732.2016.1114357

- Bryant-Davis, T. (2005). Thriving in the wake of trauma: A multicultural guide. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

- Chu, J. A., & Dill, D. L. (1990). Dissociative symptoms in relation to childhood physical and sexual abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 887–892. doi:10.1176/ajp.147.7.887

- Cosmides, L. (1989). The logic of social exchange: Has natural selection shaped how humans reason? Studies with the Wason selection task. Cognition, 31, 187–276. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(89)90023-1

- DePrince, A. P. (2005). Social cognition and revictimization risk. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6, 125–141. doi:10.1300/J229v06n01_08

- DePrince, A. P., Brown, L. S., Cheit, R. E., Freyd, J. J., Gold, S. N., Pezdek, K., & Quina, K. (2012). Motivated forgetting and misremembering: Perspectives from betrayal trauma theory. In R. F. Belli (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation Vol. 58: True and false recovered memories: Toward a reconciliation of the debate (pp. 193–243). New York, NY: Springer.

- DePrince, A. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2001). Memory and dissociative tendencies: The roles of attentional context and word meaning in a directed forgetting task. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 2, 67–82. doi:10.1300/J229v02n02_06

- DePrince, A. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2004). Forgetting trauma stimuli. Psychological Science, 15, 488–492.

- Duh, S., Paik, J. H., Miller, P. H., Gluck, S. C., Li, H., & Himelfarb, I. (2016, February 4). Theory of mind and executive function in Chinese preschool children. Developmental Psychology. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0040068

- Eberhardt, J. L., Davies, P. G., Purdie-Vaughns, V. J., & Johnson, S. L. (2006). Looking deathworthy: Perceived stereotypicality of Black defendants predicts capital-sentencing outcomes. Psychological Science, 17, 383–386. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x

- Edwards, V. J., Freyd, J. J., Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., & Felitti, V. J. (2012). Health outcomes by closeness of sexual abuse perpetrator: A test of betrayal trauma theory. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 21(2), 133–148. doi:10.1080/10926771.2012.648100

- Eidelson, R. (2016, June 20). Standing firm for reform at the APA: A deceptive coordinated campaign aims to undermine recent progress. Retrieved from the Psychology Today website: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/dangerous-ideas/201606/standing-firm-reform-the-apa

- Freyd, J. J. (1994). Betrayal-trauma: Traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics & Behaviour, 4, 307–329. doi:10.1207/s15327019eb0404_1

- Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Freyd, J. J. (1997). Violations of power, adaptive blindness, and betrayal trauma theory. Feminism and Psychology, 7, 22–32. doi:10.1177/0959353597071004

- Freyd, J. J. (2001). Memory and dimensions of trauma: Terror may be “all-too-well remembered” and betrayal buried. In J. R. Conte (Ed.), Critical issues in child sexual abuse: Historical, legal, and psychological perspectives (pp. 139–173). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Freyd, J. J. (2008, April). Betrayal trauma: Memory, health, and gender. Paper presented at the Colloquium of the Department of Psychology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM.

- Freyd, J. J. (2014). Official campus statistics for sexual violence mislead [Op-Ed]. Retrieved from the Al Jazeera America website: http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/7/college-campus-sexualassaultsafetydatawhitehousegender.html

- Freyd, J., & Birrell, P. (2013). Blind to betrayal: Why we fool ourselves we aren’t being fooled. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Freyd, J. J., Klest, B., & Allard, C. B. (2005). Betrayal trauma: Relationship to physical health, psychological distress, and a written disclosure intervention. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6, 83–104. doi:10.1300/J229v06n03_04

- Gobin, R. L., & Freyd, J. J. (2009). Betrayal and revictimization: Preliminary findings. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 1, 242–257. doi:10.1037/a0017469

- Gómez, J. M. (2015a, Spring). Conceptualizing trauma: In pursuit of culturally relevant research. Trauma Psychology News, 10(1), 40–44.

- Gómez, J. M. (2015b, October 21). Inequality plays a role in campus sexual violence [Op-Ed]. Retrieved from the Register-Guard website: http://registerguard.com/rg/opinion/33611918-78/inequality-plays-a-role-in-campus-sexual-violence.html.csp

- Gómez, J. M. (2015c). Microaggressions and the enduring mental health disparity: Black Americans at risk for institutional betrayal. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 121–143. doi:10.1177/00957798413514608

- Gómez, J. M. (2015d, August 6). Psychological pressure: Did the APA commit institutional betrayal? [Op-Ed]. Retrieved from the Eugene Weekly website: http://www.eugeneweekly.com/20150806/guest-viewpoint/psychological-pressure

- Gómez, J. M., & Freyd, J. J. (2013, August). High betrayal child sexual abuse, self injury, and hallucinations. Poster presented at the 121st Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Honolulu, HI.

- Gómez, J. M., & Freyd, J. J. (2014, August 22). Institutional betrayal makes violence more toxic [Op-Ed]. The Register-Guard, p. A9.

- Gómez, J. M., & Freyd, J. J. (2016). High betrayal child sexual abuse and hallucinations: A test of an indirect effect of dissociation. Manuscript under review.

- Gómez, J. M., Kaehler, L. A., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). Are hallucinations related to betrayal trauma exposure? A three-study exploration. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 6, 675–682. doi:10.1037/a0037084

- Gómez, J. M., Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). Zwischenmenschlicher und institutioneller verrat [Interpersonal and institutional betrayal]. In R. Vogt (Ed.), Verleumdung und Verrat: Dissoziative Störungen bei schwer traumatisierten Menschen als Folge von Vertrauensbrüchen (pp. 82–90). Roland, Germany: Asanger Verlag.

- Heimer, C. A. (2001). Solving the problem of trust. In K. S. Cook (Ed.), Trust and society (pp. 40–88). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

- Hoffman, D. H., Carter, D. J., Viglucci Lopez, C. R., Benzmiller, H. L., Guo, A. X., Yasir Latifi, S., & Craig, D. C. (2015). Report to the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent review relating to APA ethics guidelines, national security interrogations, and torture—revised September 4, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/independent-review/revised-report.pdf

- Hulette, A. C., Kaehler, L. A., & Freyd, J. J. (2011). Intergenerational associations between trauma and dissociation. Journal of Family Violence, 26, 217–225. doi:10.1007/s10896-011-9357-5

- Isler, J. C. (2015, December 17). The “benefits” of Black physics students [Op-Ed]. Retrieved from the New York Times website: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/17/opinion/the-benefits-of-black-physics-students.html?_r=0

- Kelley, L. P., Weathers, F. W., Mason, E. A., & Pruneau, G. M. (2012). Association of life threat and betrayal with posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(4), 408–415. doi:10.1002/jts.v25.4

- Levine, B. E. (2015, September 29). The 10 most egregious U.S. abuses of psychology and psychiatry. Retrieved from Salon website: http://www.salon.com/2015/09/29/10_worst_ abuses_of_psychological_assns_partner/

- Lorde, A. (2007). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. In Sister Outsider (pp. 110–113). Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

- McClain, D. (2015, December 11). A former Oklahoma City police officer is found guilty in a sexual assault case. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/former-oklahoma-city-officer-found-guilty-in-sexual-assault-case/

- Monteith, L. L., Bahraini, N. H., Matarazzo, B. B., Soberay, K. A., & Smith, C. P. (2016). A preliminary investigation of institutional betrayal related to military sexual trauma. Manuscript under review.

- Morse, G. S., Garcia, M., Trimble, J., Swaney, G., McNeill, B., Lincourt, D., & Eaglin, C. (2015, July 20). Society of Indian Psychologists: Response and recommendations upon review of the Report to the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent Review Relating to APA Ethics Guidelines, National Security Interrogations, and Torture. Retrieved from http://www.aiansip.org/uploads/R2_RESPONSE_to_Hoffman_072015_FINAL.pdf

- National Latina/o Psychological Association. (n.d.). NLPA response to APA’s independent review (aka Hoffman Report). Retrieved from http://www.nlpa.ws/assets/docs/nlpa%20response%20to%20the%20apa%20hoffman%20report%20final%20for%20release.pdf

- Padela, A. I., & Heisler, M. (2010). The association of perceived abuse and discrimination after September 11, 2001, with psychological distress, level of happiness, and health status among Arab Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 284–291. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.164954

- Philips, D. (2015, December 10). Former Oklahoma city police officer found guilty of rapes. Retrieved from the New York Times website: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/11/us/former-oklahoma-city-police-officer-found-guilty-of-rapes.html?_r=0

- Pituc, S. (2015, August 1). Asian American Psychological Association response to the American Psychological Association’s report of the independent review relating to the ethics guidelines, national security interrogations, and torture. Retrieved from http://aapaonline.org/2015/08/01/response-to-apa-independent-review/

- Platt, M., Barton, J., & Freyd, J. J. (2009). A betrayal trauma perspective on domestic violence. In E. Stark & E. S. Buzawa (Eds.), Violence against women in families and relationships (Vol. 1, pp. 185–207). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Platt, M. G., & Freyd, J. J. (2015). Betray my trust, shame on me: Shame, dissociation, fear, and betrayal trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 7, 398–404. doi:10.1037/tra0000022

- Pole, N., Best, S. R., Metzler, T., & Marmar, C. R. (2005). Why are Hispanics at greater risk for PTSD? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 11, 144–161. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.144

- Poniewozik, J. (2016, July 7). A killing. A pointed gun. And two Black lives, witnessing. Retrieved from the New York Times website: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/08/us/philando-castile-facebook-police-shooting-minnesota.html

- Pope, K. S. (2011a). Are the American Psychological Association’s detainee interrogation policies ethical and effective? Key claims, documents, and results. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 219, 150–158. doi:10.1027/2151-2604/a000062

- Pope, K. S. (2011b). Psychologists and detainee interrogations: Key decisions, opportunities lost, and lessons learned. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 459–481. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104612

- Pope, K. S. (2015). Steps to strengthen ethics in organizations: Research findings, ethics placebos, and what works. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(2), 139–152. doi:10.1080/15299732.2015.995021

- Pope, K. S. (2016a). The code not taken: The path from guild ethics to torture and our continuing choices. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 57(1), 51–59. doi:10.1037/cap0000043

- Pope, K. S. (2016b). The Hoffman Report and the American Psychological Association: Meeting the challenge of change. In K. Pope & M. J. T. Vasquez (Eds.), Ethics in psychotherapy and counseling: A practical guide, 5th ed. (pp. 361–369). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Pope, K. S., & Gutheil, T. G. (2009a). Contrasting ethical policies of physicians and psychologists concerning interrogation of detainees. British Medical Journal, 338, b1653. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1653

- Pope, K. S., & Gutheil, T. G. (2009b). Psychologists abandon the Nuremberg Ethic: Concerns for detainee interrogations. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 32(3), 161–166. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.02.005

- Psychology Clinical Science Accreditation System. (2011). Psychology Clinical Science Accreditation System: Welcome. Retrieved from http://www.pcsas.org

- Rippy, A. E., & Newman, E. (2006). Perceived religious discrimination and its relationship to anxiety and paranoia among Muslim Americans. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 1(1), 5–20. doi:10.1080/15564900600654351

- Risen, J. (2015, July 10). Outside psychologists shielded U.S. torture program, report finds. Retrieved from the New York Times website: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/11/us/psychologists-shielded-us-torture-program-report-finds.html

- Sims, M., Diez-Roux, A. V., Dudley, A., Gebreab, S., Wyatt, S. B., Bruce, M. A., … Taylor, H. A. (2012). Perceived discrimination and hypertension among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. American Journal of Public Health, 102, S258–S265. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300523

- Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2013). Dangerous safe havens: Institutional betrayal exacerbates sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(1), 119–124. doi:10.1002/jts.21778

- Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2014a). The courage to study what we wish did not exist. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(5), 521–526. doi:10.1080/15299732.2014.947910

- Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2014b). Institutional betrayal. American Psychologist, 69, 575–587. doi:10.1037/a0037564

- Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2015, August). First, do no harm: Institutional betrayal in healthcare. Symposium presented at the 123rd Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Ontario.

- Smith, C. P., Gómez, J. M., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). The psychology of judicial betrayal. Roger Williams University Law Review. 19, 451–475. Retrieved from http://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1539&context=rwu_LR

- Society of Indian Psychologists (2015, July 20). Response and recommendations upon review of the Report to the Special Committee of Board of Directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent review relating to APA ethics guidelines, national security interrogations, and torture. Retrieved from http://www.aiansip.org/uploads/R2_RESPONSE_to_Hoffman_072015_FINAL.pdf

- Soldz, S., Raymond, N., Reisner, S., Allen, S. A., Baker, I. L., & Keller, A. (2014). All the president’s psychologists: The American Psychological Association’s secret complicity with the White House and US intelligence community in support of the CIA’s “enhanced” interrogation program. Retrieved from http://www.scra27.org/files/9614/3777/1227/Soldz_Raymond_and_Resiner_All_the_Presidents_Psychologists.pdf

- Soldz, S., & Reisner, S. (2015, July 2). Opening comments of Stephen Soldz and Steven Reisner to the American Psychological Association (APA) Board of Directors. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/Soldz-Reisner

- Tang, S. S. (2015). Blindness to institutional betrayal by the APA. [Letter]. BMJ, 351, h4172.

- Terrell, F., & Terrell, S. L. (1981). An inventory to measure cultural mistrust among Blacks. The Western Journal of Black Studies, 5, 180–184.

- Thomas, N. K. (2016). “We didn't know”: Silence and silencing in organizations. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/00207284.2016.1176489

- Tolin, D. F., & Lohr, J. M. (2009, Fall). Psychologists, the APA, and torture. Clinical Science Newsletter, pp. 4–10.

- Utsey, S. O., Giesbrecht, N., Hook, J., & Stanard, P. M. (2008). Cultural, sociofamilial, and psychological resources that inhibit psychological distress in African Americans exposed to stressful life events and race-related stress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 49–62. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.49

- Whaley, A. L. (2001). Cultural mistrust: An important psychological construct for diagnosis and treatment of African Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32, 555–562. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.32.6.555