ABSTRACT

ICD-11 Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) is a disorder of six symptom clusters including reexperiencing, avoidance, sense of threat, affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbed relationships. Unlike earlier descriptions of complex PTSD, ICD-11 CPTSD does not list dissociation as a unique symptom cluster. We tested whether the ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms can exist independently of dissociation in a nationally representative sample of adults (N = 1,020) who completed self-report measures. Latent class analysis was used to identify unique subsets of people with distinctive symptom profiles. The best fitting model contained four classes including a “low symptoms” class (48.9%), a “PTSD” class (14.7%), a “CPTSD” class (26.5%), and a “CPTSD + Dissociation” class (10.0%). These classes were related to specific adverse childhood experiences, notably experiences of emotional and physical neglect. The “PTSD,” “CPTSD,” and “CPTSD + Dissociation” classes were associated with a host of poor health outcomes, however, the “CPTSD + Dissociation” class had the poorest mental health and highest levels of functional impairment. Findings suggest that ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms can occur without corresponding dissociative experiences, however, when CPTSD symptoms and dissociative experiences occur together, health outcomes appear to be more severe.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) 11th version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) came into effect on January 1, 2022 (WHO, Citation2019). Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) is included in ICD-11 alongside Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the chapter on “Disorders Specifically Associated with Stress”. CPTSD is a disorder of six symptom clusters including reexperiencing in the here and now, avoidance of trauma reminders, sense of current threat, affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. The first three symptom clusters are shared with PTSD, and the latter three are collectively termed “Disturbances in Self-Organization” (DSO). Exposure to a traumatic event, or series of events, is a requirement for ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD, and prototypical events likely to give rise to CPTSD include child abuse, intimate partner violence, torture, slavery, and genocide campaigns (Reed et al., Citation2022; WHO, Citation2019). The defining feature of traumatic events most likely to lead to the full spectrum of ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms is that escape from the trauma is difficult or impossible. Since the publication of the proposed description of ICD-11 CPTSD nearly a decade ago (Maercker et al., Citation2013), a substantial body of evidence has accumulated in support of its construct validity (Brewin et al., Citation2017; Redican et al., Citation2021). Various studies suggest that approximately 4–8% of the general adult population meet diagnostic requirements for ICD-11 CPTSD (Cloitre et al., Citation2019; Hyland, Karatzias, et al., Citation2020, Citation2021), and that the disorder is common in clinical samples (Cloitre et al., Citation2021; Murphy et al., Citation2021; Vallières et al., Citation2018).

The ICD-11 model of CPTSD differs from prior descriptions of complex PTSD including Herman’s (Citation1992) formulation, the ICD-10 diagnosis of “Enduring Personality Change After Catastrophic Experience,” and the DSM-IV appendix diagnosis of “Disorder of Extreme Stress Not Otherwise Specified” in several ways that have contributed to its success. These include the fact that ICD-11 CPTSD has a simple and well-defined set of essential features, that diagnosis is defined by the presenting symptoms rather than the nature of the trauma, that core PTSD symptoms are a requirement, and that functional impairment is necessary for diagnosis (Brewin, Citation2020). One notable difference between earlier formulations of complex PTSD and ICD-11 CPTSD relates to dissociation. In pre-ICD-11 descriptions of complex PTSD, dissociation was identified as a core feature of the condition (J. D. Ford & Courtois, Citation2009; Herman, Citation1992). In ICD-11, dissociative experiences are part of the overall symptom profile (i.e., dissociative flashbacks within the reexperiencing cluster and emotional numbing within the affective dysregulation cluster), but there is no distinct dissociation symptom cluster. Thus, dissociation is not part of the essential requirements for a diagnosis of ICD-11 CPTSD.

Dissociation involves the temporary or prolonged absence of normal integration of psychological phenomena manifesting in a variety of ways including pathological absorption, trauma-related amnesia, identity disturbances, unexplained physical pain, depersonalization, and derealization (Moskowitz, Citationn.d..). Dissociation is positively correlated with history of trauma exposure, and much like ICD-11 CPTSD, exposure to traumatic events from which escape is difficult or impossible is most likely to lead to dissociation (Bailey & Brand, Citation2017; Briere et al., Citation2008; Cloitre et al., Citation2009). A meta-analysis of 65 studies including 7,352 people found that dissociation was most common in survivors of childhood abuse and childhood neglect, and levels of dissociation were highest amongst those who had experienced childhood physical abuse and childhood sexual abuse (Vonderlin et al., Citation2018). In their analysis of the World Mental Health Survey data, Stein et al. (Citation2013) found that two adverse childhood experiences – parental mental illness and family violence – were independently associated with a dissociative subtype of PTSD. Jowett et al. (Citation2021) also reported that dissociation mediates the relationship between traumatic life events in childhood and the presence of ICD-11 CPTSD symptom clusters.

In a landmark paper published a decade ago, Dalenberg and Carlson (Citation2012) discussed the various ways in which dissociation might be related to DSM-IV PTSD, namely as a mediator in the relationship between trauma and PTSD, as a moderator of the relationship between trauma and PTSD, as a comorbid outcome of trauma alongside PTSD, as a component of PTSD, or as a subtype of PTSD. Following a review of the literature they concluded that the evidence most strongly supported conceptualizing dissociation as a component of DSM-IV PTSD or as a subtype of DSM-IV PTSD. Subsequently, the DSM-5 included a dissociative subtype of PTSD (i.e., PTSD plus symptoms of depersonalization or derealization), and various studies suggest that approximately one-in-five people that meet diagnostic criteria for DSM-5 PTSD satisfy requirements for the dissociative subtype (Hansen et al., Citation2017; Stein et al., Citation2013).

Theoretical accounts of how dissociation is related to ICD-11 CPTSD have not been published, but several studies have explored how these constructs are related (Bondjers et al., Citation2019; Elklit et al., Citation2014; Hyland, Karatzias, et al., Citation2020; Møller et al., Citation2021). Two consistent findings have emerged. One is that those meeting diagnostic criteria for ICD-11 CPTSD (or those with a symptom profile reflecting ICD-11 CPTSD) have higher levels of dissociation than those meeting diagnostic criteria for ICD-11 PTSD or no diagnosis (or those with a symptom profile reflecting ICD-11 PTSD or neither disorder). The other is that the ICD-11 CPTSD symptom clusters of reexperiencing in the here and now, affective dysregulation, and disturbed relationships are most strongly associated with dissociation.

Given that dissociation and ICD-11 CPTSD share a key etiological risk factor (i.e., exposure to trauma from which escape is difficult or impossible), that dissociation is prominent among those who meet diagnostic requirements for ICD-11 CPTSD, and that dissociation was once considered a core feature of complex PTSD, it raises the question of whether dissociation should be considered a core component of ICD-11 CPTSD. If, as ICD-11 describes, dissociation is not a core component of CPTSD then researchers should seek to understand how dissociation relates to this disorder (e.g., as a mediator, moderator, or comorbid response to trauma). However, if the ICD-11 model of CPTSD is incorrect, and dissociation is a core but unrecognized component of the disorder, this would have serious implications for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning. Consequently, the primary objective of this study is to test whether dissociation and ICD-11 CPTSD are empirically distinguishable.

A mixture-modeling approach will be used to identify the optimal number of discrete latent classes required to explain the covariation between ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms and a range of dissociative experiences. Assuming the ICD-11 formulation of CPTSD is accurate (i.e., that dissociation is not a core component of CPTSD), the best-fitting model should include multiple classes where at least one class has elevated probabilities of all ICD-11 CPTSD features and correspondingly low probabilities of all dissociative features. This would demonstrate that ICD-11 CPTSD can occur without dissociation. However, if the best-fitting model includes multiple classes where each class with elevated probabilities of all ICD-11 CPTSD features also has elevated probabilities of dissociation, this would suggest that dissociation is a component of CPTSD, and thus represent positive evidence against the ICD-11 formulation of CPTSD.

Secondary aims are to explore how the resultant latent classes are associated with specific adverse childhood experiences, and how the classes vary across a range of indicators of mental health and functional impairment. Given the uncertainty over the latent classes that will emerge in the best fitting mixture model, no specific hypotheses are formulated for these secondary aims.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This study uses data collected in February 2019 from a non-probability, nationally representative sample of adults living in the Republic of Ireland (N = 1,020). These data were collected by the survey company Qualtrics, with participants recruited from actively managed, double-opt-in research panels via e-mail, text message, or in-app notifications. Quota sampling methods were used to recruit a sample that was representative of the general adult population of Ireland in terms of sex, age, and geographical distribution, as per Irish census data at the time (Central Statistics Office, Citation2016). It is important to note however that certain member of society (i.e., those hospitalized, in prison, homeless, or without access to the internet) were not eligible for inclusion in the study as they could not belong to a research panel. Inclusion criteria were that respondents were aged 18 years or older, residing in the Republic of Ireland, and capable of completing the survey in English. Participants were remunerated by Qualtrics, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval was granted by the Social Research Ethics Committee at Maynooth University in Ireland (SRESC-2019-001). Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are presented in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample (N = 1,020).

Materials

Primary measures

ICD-11 CPTSD

The International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ: Cloitre et al., Citation2018) is a self-report measure capturing all diagnostic criteria for ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD. Participants completed the ITQ in relation to their worst traumatic life event, as identified using the International Trauma Exposure Measure (Hyland, Karatzias, et al., Citation2021). There are 12 items measuring the six symptom clusters of reexperiencing in the here and now, avoidance, sense of current threat, affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbed relationships. Each symptom cluster is measured using two items, and all items use a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). A symptom is present based on a response of ≥ 2 (Moderately) on the Likert scale. Diagnostic rules for ICD-11 CPTSD require that at least one symptom is present from each cluster. The psychometric properties of the ITQ are well supported (Redican et al., Citation2021), and the internal reliability of the scale scores in this sample was excellent (α = .93).

Dissociation

The ten-item dissociation subscale of the Trauma Symptom Inventory-2 (Briere, Citation2011) was used to measure dissociative experiences. Items include “feeling like you were in a dream,” “feeling like you were outside your body,” “feeling like things weren’t real,” “spacing out,” “finding yourself some place and not knowing how you got there,” “people saying you don’t pay enough attention to what’s going on around you,” “feeling like there were two or more people inside you,” “not feeling like your real self,” “having trouble remembering the details about something bad that happened to you,” and “feeling like you were watching yourself from far away.” Respondents were asked to report how frequently they had each experience in the last six months using a four-point Likert scale including response options Never (0), Rarely (1), Sometimes (2), and Often (3). The psychometric properties of the TSI-2 have been well supported (Godbout et al., Citation2016). We used confirmatory factor analysis with weight least squares mean- and variance-adjusted estimation to test the unidimensional structure of these items in the current sample. This model had acceptable fit to the sample data (χ2 (35) = 343.05, p < .001; CFI = .98; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .09; SRMR = .03), and all items loaded significantly (p < .001) and strongly (factor loadings ranged from .74 to .90) on to the latent factor. The internal reliability of the scale scores was excellent (α = .92).

Secondary measures

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-Q; Felitti et al., Citation1998) measures exposure to ten events occurring before the age of 18. All items were answered on a “Yes” (1) or “No” (0) basis. The measure is widely used and multiple studies with adult samples have demonstrated that the ACE-Q produces reliable and valid scale scores (e.g., D. C. Ford et al., Citation2014). The internal reliability of the scale scores in this sample was good (α = .79).

Depression and general anxiety

Participants completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9: Kroenke et al., Citation2001) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale (GAD-7: Spitzer et al., Citation2006). These measures ask participants to indicate how often they have been bothered by each symptom over the last two weeks using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Nearly every day). Total scores range from 0–27 and 0–21 on the two measures, respectively. Both measures have been shown to produce reliable and valid scores in general population surveys (Hinz et al., Citation2017; Shin et al., Citation2020). The PHQ-9 (α = .93) and GAD-7 (α = .94) had excellent internal reliability in this sample.

Psychosis

A modified version of the seven-item Adolescent Psychotic-like Symptom Screener (APSS: Kelleher et al., Citation2011) was used. Items include “Some people believe that their thoughts can be read by another person. Have other people ever read your mind?” and “Have you ever felt you were under the control of some special power?” Participants first indicated how often they had each experience on a four-point Likert scale (Never, Sometimes, Often, and Nearly Always), and then how distressed they were by each experience, also on a four-point Likert scale (Not distressed, A bit distressed, Quite distressed, and Very distressed). A “symptom” of psychosis was present if (a) the frequency was rated as Sometimes or above, and (b) the distress was rated as A bit distressed or more. The summed score ranges from 0–7 with higher scores reflecting greater symptomatology. Kelleher et al. (Citation2011) reported that APSS scores detected those with clinical interview verified psychotic experiences with a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 83%. The internal reliability of the seven psychosis symptoms in this sample was good (α = .88).

Somatization

The ten-item somatization subscale of the Trauma Symptom Inventory-2 (Briere, Citation2011) was used. As with the dissociation items, respondents indicated how frequently they had each experience (e.g., aches or pains, dizziness, lower back pain) in the last six months along a four-point Likert scale with the response options Never (0), Rarely (1), Sometimes (2), and Often (3). The internal reliability of the somatization scale scores in this sample was good (α = .87).

Functional impairment

The five-item Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS: Mundt et al., Citation2002) assesses perceived impairments across five domains of work, home management, social leisure activities, private leisure activities, and relationships with others. Participants were asked to rate their agreement that their feelings affect their ability to engage in each activity on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly agree) to 7 (Strongly disagree). Scores range from 5–35 with lower scores indicating greater impairment. The WSAS has been shown to provide reliable and valid scores (Jansson-Fröjmark, Citation2014), and the internal reliability of the scale scores in this sample was excellent (α = .92).

Healthcare utilization

Participants were asked to indicate how many times in the last 12 months they had visited their general practitioner (G.P.), how many times in the last 12 months they had visited a mental health professional such as a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, or therapist, how many different medications they had been prescribed in the last 12 months, and how many times they had visited a hospital for treatment in the last 12 months.

Data analysis

The analytic plan for this study involved several steps. First, latent class analysis (LCA) was used to determine the optimal number of classes based on responses to the ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociation items. To keep the observed variables to a manageable number, six binary items representing whether participants met the diagnostic requirement for each of ICD-11 CPTSD symptom clusters were used (i.e., one of two symptoms were present for the six symptom clusters). Given the use of diagnostic thresholds for the CPTSD items, we set the threshold for dichotomizing the dissociation items to be above the mid-point on the Likert such that those who responded Often (3) were distinguished from those who responded Never (0), Rarely (1), and Sometimes (2). Models with 1–6 latent classes were estimated using the robust maximum likelihood estimation (Yuan & Bentler, Citation2000). To avoid solutions based on local maxima, 500 random sets of starting values and 100 final stage optimizations were used. The relative fit of these models was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, Citation1987), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC;Schwartz, Citation1978), and the sample-size adjusted BIC (ssaBIC; Sclove, Citation1987). In each case, the model with the lowest value is considered the best fitting model, and the BIC is considered the best test for detecting the correct number of classes (Nylund et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-A; Lo et al., Citation2001) compares models with increasing numbers of classes, and a non-significant result indicates that the model with one less class is the preferred model. Entropy values were assessed to determine how accurately individuals are classified into classes with values closer to 1 indicating better classification.

Second, after determining the best fitting LCA model, the latent classes were regressed onto the ten ACE items, as well as variables representing participant sex (0 = males, 1 = females) and age. These analyses were carried out using the “R3step method” which prevents class shifts due to the inclusion of covariates while accounting for the classification uncertainty rate (i.e., measurement error) (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014). Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals were computed to represent the independent associations between each predictor variable and membership of the classes.

Finally, the “BCH method” was used to compare the latent classes across all mental health and functional impairment variables (Bolck et al., Citation2004). Mean differences across the latent classes were assessed using an overall Wald chi-square test and pairwise comparisons. All analyses were performed using Mplus version 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017).

Results

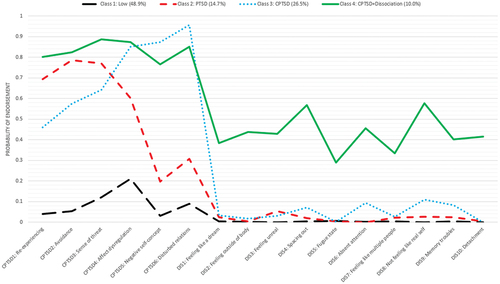

The fit statistics for the LCA models are presented in . The BIC results indicate that the best fitting model includes four latent classes. The BIC values declined markedly for models with one through to four classes, and then remained similar for the model with five classes before increasing for the model with six classes. Moreover, the LMR-A become statistically non-significant for the model with five classes suggesting no improvement in fit for the extraction of a fifth class. Inspection of the profile plots for the four- and five-class solutions revealed that one class in the four-class solution was split into two quantitatively differing classes in the five-class solution meaning no substantively new information was obtained by extracting an additional class. Thus, considering model fit, model parsimony, and model interpretability, the four-class solution was deemed to be the optimal representation of the sample data. The entropy value for this model was .84 suggesting good classification of participants to the respective latent classes. The latent classes profiles are displayed in .

Table 2. Latent Class Analysis Fit Statistics for Complex PTSD and Dissociation.

Class 1 (48.9%) was characterized by low probabilities of endorsing all ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociation items. This was labeled the “Low” class. Class 2 (14.7%) was characterized by elevated probabilities of meeting criteria for reexperiencing in the here and now, avoidance, and sense of current threat, and low probabilities of all other items. This was labeled the “PTSD” class. Class 3 (26.5%) was characterized by elevated probabilities of meeting criteria for the six ICD-11 CPTSD symptom clusters and low probabilities of endorsing all dissociation items. This was labeled the “CPTSD” class. Finally, Class 4 (10.0%) was characterized by high probabilities of meeting the criteria for the six ICD-11 CPTSD symptom clusters and elevated probabilities of endorsing all dissociation items. This was labeled the “CPTSD + Dissociation” class.

The latent classes were regressed on to the ten ACE events, plus gender and age, with the “Low” class set as the reference category (see ). Membership of the “PTSD” class was associated with emotional neglect (AOR = 2.76) and mental illness at home (AOR = 2.11). Membership of the “CPTSD” class was also associated with emotional neglect (AOR = 5.09) and mental illness at home (AOR = 2.24). Membership of the “CPTSD + Dissociation” class was associated with verbal abuse (AOR = 2.83), emotional neglect (AOR = 3.26), and mental illness at home (AOR = 3.74). Older age was associated with lower odds of membership of the “CPTSD” (AOR = 0.96) and “CPTSD + Dissociation” (AOR = 0.94) classes.

Table 3. Correlates of Class Membership.

The four latent classes were compared across all mental health and functional impairment variables (see ). The four classes significantly differed on all measures. Focusing on the pairwise comparisons between the “CPTSD + Dissociation” and “CPTSD” classes, the former had significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, psychosis, and somatization, and reported more visits to the GP, a mental health professional, and to the hospital in the last 12 months.

Table 4. Tests of Mean Differences Across Latent Classes (N = 1,020).

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to test whether ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms were empirically distinguishable from dissociation in a large general population sample. Our findings suggest that ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms can occur without dissociative experiences, however, a notable minority of people with ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms also showed elevated dissociative experiences. These findings provide tentative support for the conceptual and diagnostic model of CPTSD in ICD-11, while also indicating that dissociation is likely to co-occur with CPTSD for many people.

Additional aims included investigating associations between the latent classes and specific adverse childhood experiences as well as a range of indicators of mental health and functional impairment. We found that membership of the “PTSD,” “CPTSD,” and “CPTSD + Dissociation” classes were uniquely associated with a history of emotional neglect and growing up in a home with a household member that was mentally ill or had attempted suicide. Additionally, membership of the “CPTSD + Dissociation” class was also uniquely associated with a history of parental verbal abuse. Meta-analytic results previously showed that neglect during childhood is strongly associated with dissociation (Vonderlin et al., Citation2018), and that history of family violence and living with a household member with mental illness is uniquely associated with dissociative PTSD, as per the DSM-IV description (Stein et al., Citation2013). Our results add to these findings by highlighting the importance of early-life neglect and an unstable family environment for both ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociation. Theoretically, it has been suggested that children exposed to these types of inescapable and ongoing abuses from a parent or caregiver experience dissociation as a means of avoiding emotional distress and maintaining attachment with their caregivers (Bailey & Brand, Citation2017; Liotti, Citation1992; Nijenhuis et al., Citation1998). Fearful attachments have been found to correlate with both ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms (Karatzias et al., Citation2021) and dissociation (Simeon & Knutelska, Citation2022), and thus may be a useful clinical target for those people experiencing ICD-11 CPTSD and corresponding dissociation.

Those belonging to the “PTSD,” “CPTSD,” and “CPTSD + Dissociation” classes all reported poorer mental health and more impairments in their daily lives than those in the “Low” class. Notably, however, those in the “CPTSD + Dissociation” class had the poorest mental health and the highest levels of impaired functioning. Individuals with ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms and pervasive dissociative experiences will therefore likely require additional clinical interventions to achieve satisfactory outcomes. It should be stressed however that although the existing literature indicates that there are several barriers to treatment for those with dissociation in clinical practice (Nester et al., Citation2022), there are several programs including those with a trauma-focused component, that have demonstrated success in the resolution of dissociative symptoms co-occurring with PTSD and complex PTSD symptoms (Hoeboer et al., Citation2020). Research on how best to engage and treat patients with dissociation and what type of treatment will produce the best outcomes for this population is needed. The results of this investigation are helpful. They provide evidence that different kinds of dissociative symptoms, as represented in reexperiencing symptoms, emotional numbing or depersonalization/derealization, are organized differently in the diagnosis. This may have clinical implications regarding the translation of the identified symptom profile to optimal treatment interventions and engagement efforts.

There are several limitations with this study which should be noted. The first relates to the nature of “dissociation.” Dissociation tends to be defined and measured quite differently across studies (Nijenhuis & van der Hart, Citation2011), and there are debates as to what constitutes “normal” and “abnormal” dissociation. The measure of dissociation used in this study was designed as a global measure capturing a variety of dissociative experiences that may be considered more common (i.e., derealization) or less common (i.e., fugue states and identity disruption) following trauma. Replicating these findings with measures specifically designed to capture clinical manifestations of dissociation, including dissociative identity disorder, will be beneficial. Second, the use of a self-report measure of dissociation may be considered a limitation. For those experiencing dissociation, it may be challenging to accurately report on the frequency of their dissociative experiences. Measurement challenges like this will also exist with clinician-administered measures but replication with alternative measurement approaches is recommended. Third, these findings were derived from a non-clinical, general population sample. Since our sampling methodology could not include persons that were hospitalized, imprisoned, homeless etc. at the time of data collection, and it is precisely these people that may be more likely to have co-occurring ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociative experiences, it is possible that our recruitment method underrepresented those individuals in society with the highest likelihood of belonging to the “CPTSD + Dissociation” class. Future research with clinical and vulnerable samples will be required to determine whether ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms can manifest independently of dissociation among those in the population experiencing high levels of psychological distress. Relatedly, replication with samples characterized by high levels of chronic, early life trauma would be useful given that this is an etiological risk factor for both dissociation and ICD-11 CPTSD. Fourth, LCA requires the dichotomization of items into binary variables and the categorization point we selected in this study for the dissociation items was somewhat arbitrary. We selected responses above the mid-point on the Likert scale to try and capture a “clinical” threshold, but this inevitably raises doubts about the reliability of the reported results. Much more research is needed before any strong conclusions should be drawn about the separability of ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociation.

In conclusion, the findings from this study suggest that ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms can exist independently of dissociation. Nevertheless, for a substantial minority of people with ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms, dissociation co-occurs, and this co-occurrence of symptoms is associated with more severe and debilitating health profiles. Future work with longitudinal designs will be required to understand how ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociation symptoms emerge and potentially influence one another after trauma exposure.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akaike, H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294359

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using mplus. Structural Equation Modeling, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Bailey, T. D., & Brand, B. L. (2017). Traumatic dissociation: Theory, research, and treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 24(2), 170–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12195

- Bolck, A., Croon, M., & Hagenaars, J. (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mph001

- Bondjers, K., Hyland, P., Roberts, N. P., Bisson, J. I., Willebrand, M., & Arnberg, F. K. (2019). Validation of a clinician-administered diagnostic measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: The international trauma interview in a Swedish sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1665617. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1665617

- Brewin, C. R. (2020). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A new diagnosis in ICD-11. BJPsych Advances, 26(3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2019.48

- Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Maercker, A., Bryant, R. A., Humayun, A., Jones, L. M., Kagee, A., Rousseau, C., Somasundaram, D., Suzuki, Y., Wessely, S., van Ommeren, M., & Reed, G. M. (2017). A review of current evidence regarding the ICD-11 proposals for diagnosing PTSD and complex PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.001

- Briere, J. (2011). Trauma Symptom Inventory–2 (TSI–2). Psychological Assessment Resources. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy1010

- Briere, J., Kaltman, S., & Green, B. L. (2008). Accumulated childhood trauma and symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(2), 223–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20317

- Central Statistics Office. (2016). Census 2016 reports. Retrieved June 29, 2022. from https://www.cso.ie/en/census/census2016reports/

- Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Bisson, J. I., Brewin, C. R., Roberts, N. P., Karatzias, T., & Shevlin, M. (2019). ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: A population‐based study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(6), 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22454

- Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Prins, A., & Shevlin, M. (2021). The International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) measures reliable and clinically significant treatment-related change in PTSD and complex PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1930961. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1930961

- Cloitre, M., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Maercker, A., Karatzias, T., & Hyland, P. (2018). The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 536–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12956

- Cloitre, M., Stolbach, B. C., Herman, J. L., van der Kolk, B., Pynoos, R., Wang, J., & Petkova, E. (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20444

- Dalenberg, C., & Carlson, E. B. (2012). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder part ii: How theoretical models fit the empirical evidence and recommendations for modifying the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Psychological Trauma, 4(6), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027900

- Elklit, A., Hyland, P., & Shevlin, M. (2014). Evidence of symptom profiles consistent with posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in different trauma samples. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.24221

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998, May). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ace) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Ford, J. D., & Courtois, C. A. (2009). Defining and understanding complex trauma and complex traumatic stress disorders. In C. A. Courtois & J. D. Ford (Eds.), Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide (pp. 13–30). The Guilford Press.

- Ford, D. C., Merrick, M. T., Parks, S. E., Breiding, M. J., Gilbert, L. K., Edwards, V. J., Dhingra, S. S., Barile, J. P., & Thompson, W. W. (2014). Examination of the factorial structure of adverse childhood experiences and recommendations for three subscale scores. Psychology of Violence, 4(4), 432–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037723

- Godbout, N., Hodges, M., Briere, J., & Runtz, M. (2016). Structural analysis of the Trauma Symptom Inventory–2. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(3), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.1079285

- Hansen, M., Ross, J., & Armour, C. (2017). Evidence of the dissociative PTSD subtype: A systematic literature review of latent class and profile analytic studies of PTSD. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.004

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books/Hachette Book Group.

- Hinz, A., Klein, A. M., Brähler, E., Glaesmer, H., Luck, T., Riedel-Heller, S. G., Wirkner, K., & Hilbert, A. (2017). Psychometric evaluation of the generalized anxiety disorder screener GAD-7, based on a large German general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.012

- Hoeboer, C. M., De Kleine, R. A., Molendijk, M. L., Schoorl, M., Oprel, D. A. C., Mouthaan, J., Van der Does, W., & Van Minnen, A. (2020). Impact of dissociation on the effectiveness of psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Meta-analysis. BJPsych Open, 6(3), e53. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.30

- Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Cloitre, M., & Ben-Ezra, M. (2020). A longitudinal study of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in the general population of Israel. Psychiatry Research, 286, 112871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112871

- Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., McElroy, E., Ben-Ezra, M., Cloitre, M., & Brewin, C. R. (2021). Does requiring trauma exposure affect rates of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD? Implications for DSM–5. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 13(2), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000908

- Jansson-Fröjmark, M. (2014). The work and social adjustment scale as a measure of dysfunction in chronic insomnia: Reliability and validity. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42(2), 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246581200104X

- Jowett, S., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., & Hyland, P. (2021). Psychological trauma at different developmental stages and ICD-11 CPTSD: The role of dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 23(1), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2021.1934936

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Ford, J. D., Fyvie, C., Grandison, G., Hyland, P., & Cloitre, M. (2021). Childhood trauma, attachment orientation, and complex PTSD (CPTSD) symptoms in a clinical sample: Implications for treatment. Development and Psychopathology, 34, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001509

- Kelleher, I., Harley, M., Murtagh, A., & Cannon, M. (2011). Are screening instruments valid for psychotic-like experiences? A validation study of screening questions for psychotic-like experiences using in-depth clinical interview. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(2), 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp057

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Liotti, G. (1992). Disorganized/Disoriented attachment in the etiology of the dissociative disorders. Dissociation, 5, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1994/05679/001

- Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767

- Maercker, A., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., Cloitre, M., van Ommeren, M., Jones, L. M., Humayan, A., Kagee, A., Llosa, A. E., Rousseau, C., Somasundaram, D. J., Souza, R., Suzuki, Y., Weissbecker, I., Wessely, S. C., First, M. B., & Reed, G. M. (2013). Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: Proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry, 12(3), 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20057

- Møller, L., Bach, B., Augsburger, M., Elklit, A., Søgaard, U., & Simonsen, E. (2021). Structure of ICD-11 complex PTSD and relationship with psychoform and somatoform dissociation. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(3), 100233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100233

- Moskowitz, A. (n.d.). What is Dissociation?. Estd. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from http://estd.org/what-dissociation

- Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. H. (2002). The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.5.461

- Murphy, D., Karatzias, T., Busuttil, W., Greenberg, N., & Shevlin, M. (2021). ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD) in treatment seeking veterans: Risk factors and comorbidity. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(7), 1289–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02028-6

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus User’s Guide (Eighth ed.). Muthén & Muthén. 1998.

- Nester, M. S., Hawkins, S. L., & Brand, B. L. (2022). Barriers to accessing and continuing mental health treatment among individuals with dissociative symptoms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2031594. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2022.2031594

- Nijenhuis, E. R. S., & van der Hart, O. (2011). Dissociation in trauma: A new definition and comparison with previous formulations. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12(4), 416–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2011.570592

- Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Vanderlinden, J., & Spinhoven, P. (1998). Animal defensive reactions as a model for trauma-induced dissociative reactions. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024447003022

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A monte carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Redican, E., Nolan, E., Hyland, P., Cloitre, M., McBride, O., Karatzias, T., Murphy, J., & Shevlin, M. (2021). A systematic literature review of factor analytic and mixture models of ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD using the International Trauma Questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 79, 102381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102381

- Reed, G. M., First, M. B., Billieux, J., Cloitre, M., Briken, P., Achab, S., Brewin, C. R., King, D. L., Kraus, S. W., & Bryant, R. A. (2022). Emerging experience with selected new categories in the ICD-11: Complex PTSD, prolonged grief disorder, gaming disorder, and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry, 21(2), 189–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20960

- Schwartz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136

- Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294360

- Shin, C., Ko, Y. H., An, H., Yoon, H. K., & Han, C. (2020). Normative data and psychometric properties of the patient health questionnaire-9 in a nationally representative Korean population. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02613-0

- Simeon, D., & Knutelska, M. (2022). The role of fearful attachment in depersonalization disorder. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation = Revue Européenne du Trauma et de la Dissociation, 6(3), 100266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2022.100266

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Stein, D. J., Koenen, K. C., Friedman, M. J., Hill, E., McLaughlin, K. A., Petukhova, M., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, V., Spiegel, D., Borges, G., Bunting, B., Caldas de Almeida, J. M., de Girolamo, G., Demyttenaere, K., Florescu, S., Haro, J. M., Karam, E. G., Kovess-Masfety, V. … Kessler, R. C. (2013). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from the world mental health surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(4), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.022

- Vallières, F., Ceannt, R., Daccache, F., Abou Daher, R., Sleiman, J., Gilmore, B., Byrne, S., Shevlin, M., Murphy, J., & Hyland, P. (2018). ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD amongst Syrian refugees in Lebanon: The factor structure and the clinical utility of the International Trauma Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 547–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12973

- Vonderlin, R., Kleindienst, N., Alpers, G. W., Bohus, M., Lyssenko, L., & Schmahl, C. (2018). Dissociation in victims of childhood abuse or neglect: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Medicine, 48(15), 2467–2476. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718000740

- World Health Organization. (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (11th ed.). https://www.who.int/

- Yuan, K. H., & Bentler, P. M. (2000). Three Likelihood-Based Methods for Mean and Covariance Structure Analysis with Nonnormal Missing Data. Sociological Methodology, 30(1), 165–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/0081-1750.00078