ABSTRACT

The impacts of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been well documented. One possible consequence of ACEs is dissociation, which is a major feature of post-traumatic psychopathology and is also associated with considerable impairment and health care costs. Although ACEs are known to be associated with both psychoform and somatoform dissociation, much less is known about the mechanisms behind this relationship. Little is known about whether social and interpersonal factors such as family environments would moderate the relationship between ACEs and somatoform dissociation. This paper discusses the importance of having a positive and healthy family environment in trauma recovery. We then report the findings of a preliminary study in which we examined whether the association between ACEs and somatoform dissociation would be moderated by family well-being in a convenience sample of Hong Kong adults (N = 359). The number of ACEs was positively associated with somatoform dissociative symptoms, but this association was moderated by the level of family well-being. The number of ACEs was associated with somatoform dissociation only when the family well-being scores were low. These moderating effects were medium. The findings point to the potential importance of using family education and intervention programs to prevent and treat trauma-related dissociative symptoms, but further investigation is needed.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been recognized as a major public health issue because of their long-lasting health consequences (Hughes et al., Citation2017). A total of 789 academic papers on ACEs were published between 1998 and 2018, providing a rich literature describing the potential physical and mental health impacts of ACEs (Struck et al., Citation2021). The most commonly investigated ACEs include childhood maltreatment and household dysfunctions, although some other types of ACEs could be harmful too (Bartlett & Sacks, Citation2019; Felitti et al., Citation1998; Waite & Ryan, Citation2020). ACEs have been suggested to be the most preventable risk factor for severe mental disorders and many leading causes of death (e.g., substance abuse, suicide, heart diseases) (The Childhood Adversity Narratives, Citation2015). Research also shows that ACEs are quite common in different populations, including in well-developed countries. For instance, a systematic review found that the prevalence rates of ACEs range from 41% to 97% in school-aged youth; in nationally representative samples, the rates can be as high as 79% (Iceland) to 83% (Netherlands) (see Carlson et al., Citation2020).

While not all ACEs can be regarded as a “traumatic” event according to the DSM-5-TR definition (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022), many of these adverse experiences could be overwhelming to children because their vulnerable brains are still developing and because they do not yet have the social, physical and mental resources to cope with the stress. Betrayal trauma theory (Freyd, Citation1996) affirms the key role of caregiver abusive behavior, emphasizing the importance of the traumatized child remaining attached to the abusive caregiver despite the pain and betrayal the caregiver has created. This theory suggested that dissociation is a process of overlooking facts that would intrude with the need to stay in close proximity to an abusive attachment figure, thus providing as a protective mechanism once physical flee is not feasible. Certain ACEs (such as neglect or abandonment by a caregiver) may be traumatic to a child even though they may not necessarily meet the DSM-5-TR definition of a traumatic event. Thus, many ACEs can be “traumatic” to children in the sense that their “ability to integrate his/her emotional experience is overwhelmed” (Giller, Citation1999). Integration refers to the ability to recognize the past while maintaining centered in the present, and it involves the process of synthesis (binding and differentiating different experiences [e.g., memories, emotions, sensation] of a particular event) and realization (which includes personification and presentification) (Piedfort-Marin, Citation2019; Van der Hart et al., Citation2006). The opposite of integration is dissociation, which refers to failure in the process of integrating certain biopsychosocial experiences (e.g., emotions, memories, identities) (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022; Ross, Citation2007; Scalabrini et al., Citation2020). Dissociation may affect either or both psychoform and somatoform experiences (Van der Hart et al., Citation2005), with psychoform dissociation being more commonly investigated in the literature (Pullin et al., Citation2014). While both types of dissociation involve a disconnection from one’s sense of self, somatoform dissociation is specific to physical sensations while psychoform dissociation is specific to mental processes (Henschel et al., Citation2019). Although somatoform dissociation is less emphasized than psychoform dissociation in the DSM-5-TR dissociative disorders section, it has long been suggested that somatoform symptoms are related to trauma and dissociation (Van der Kolk, Citation2014) and should be conceptualized as dissociative in nature (Brown et al., Citation2007; Nijenhuis, Citation2001; Nijenhuis et al., Citation1998). Somatoform dissociation describes symptoms (e.g., analgesia or anesthesia, pain, lack of mobility, or pseudoseizures) that are phenomenologically related to the body but cannot be attributed to a medical disease (Mueller-Pfeiffer et al., Citation2010). Theoretically speaking, similar to psychoform dissociation, somatoform dissociation can be a self-defense mechanism in which the painful bodily experiences or sensations are kept out of the conscious mind, so that the child can remain attached to the caretaker-perpetrator, become “apparently normal,” and function in daily life (Freyd, Citation2008; Van der Hart et al., Citation2006). It is important to note that the conceptual definition of dissociation is still a debated topic in the field (Fung, Ross, et al., Citation2022), as some scholars believe that only those experiences involving structural dissociation of the personality are “dissociative” while other experiences (e.g., depersonalization) may not necessarily be (Nijenhuis & Van der Hart, Citation2011; Van der Hart, Citation2021). Despite the disagreements regarding the conceptualization and definition of dissociation in the field, operationally defined dissociative symptoms are empirically linked to trauma and adversities (Dalenberg et al., Citation2012). The association between childhood betrayal trauma and dissociative symptoms has been observed across cultures (Fung, Chien, Chan, et al., Citation2022); dissociation is a core feature of post-traumatic psychopathology and it is also one of the major consequences of ACEs (Fung, Chien, Lam, et al., Citation2022; Van der Hart et al., Citation2006). Importantly, severe dissociation is associated with considerable impairment and huge health care costs (Brand & Loewenstein, Citation2010; Gonzalez Vazquez et al., Citation2017). Especially, somatoform dissociation is more likely to be related to ACEs than psychoform dissociation as the ACEs are often related to physical and emotional trauma (Kate et al., Citation2020). Although many studies have shown that social and interpersonal environments (e.g., perceived support, quality of parenting) may buffer the effects of adverse experiences on mental health problems (e.g., Evans et al., Citation2013; Gewirtz-Meydan, Citation2020; McCabe et al., Citation2020), little is known about what specific social and interpersonal factors would moderate the relationship between ACEs (which by definition occur before 18 years old) and somatoform dissociation in adulthood. Although a large body of work has found that ACEs are associated with dissociation, more research is needed to investigate which types of ACEs are particularly associated with somatoform dissociation (Kienle et al., Citation2017).

A recent study showed that paternal emotional validation moderated the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and post-traumatic and depressive symptoms in children (Ferrajão, Citation2020). Another study indicated that spousal support can provide a buffer against trauma symptoms among IPV-exposed men (Evans et al., Citation2014). Family environments are important for mental health recovery, especially among trauma survivors. Substantial evidence from systematic reviews suggested that mental health problems are associated with loneliness and perceived social support (Wang et al., Citation2018), intimate partner violence victimization (Lagdon et al., Citation2014), and family and social capital (McPherson et al., Citation2014). It has also been reported that low social support, perceived threat to life and poor family functioning are significant risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder, with large effects (Smith et al., Citation2019). Two recent systematic reviews further indicated that social and family support is associated with better response to trauma treatment (Dewar et al., Citation2020; Fredette et al., Citation2016). This literature points to the importance of taking social and family environments into account when preventing and treating trauma-related mental health problems. We hypothesize that general family well-being should moderate the relationship between ACEs and somatoform dissociation. However, this has not been previously investigated. Such knowledge gaps should be addressed in order to inform risk assessment and faciliate the development of future preventative and early intervention strategies for somatoform dissociation in people exposed to ACEs.

The present study aimed to further our understanding of the relationship between ACEs and somatoform dissociation. We analyzed archival data collected in a sample of Chinese-speaking adults who completed self-report measures of ACEs, somatoform dissociation and family well-being. The degree to which family life is perceived as harmonious, orderly, and fulfilling is referred to as family well-being (Amato & Partridge, Citation1987). The specific relationship between different types of ACEs and somatoform dissociation were not examined in previous studies. The potential moderating effect of family well-being had not been explored either. Therefore, in the present study, we examined which types of ACEs would be particularly associated with somatoform dissociation. We also examined whether family well-being would moderate the relationship between ACEs (which by definition occur before 18 years old) and current somatoform dissociation (within the past year). As discussed, we tested this hypothesis because we assume that when there is good family well-being, the individual may have more opportunities and socio-emotional resources to talk about the painful experiences so that such experiences can be processed and integrated. With a safe and supportive family environment in recent days, even when exposed to adverse experiences before 18 years old, the individual may be more able to acknowledge and accept their own experiences, including sensations and bodily controls.

Method

Participants

We analyzed archival data collected in a previous project which investigated life experiences and mental health problems in a convenience sample of Hong Kong adults. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the City University of Hong Kong. The methodology and part of the data have been reported elsewhere (Fung, Chung, et al., Citation2020; Fung, Ross, et al., Citation2020). All participants were recruited through Hong Kong-based online channels (e.g., social media platforms and online groups). They were Chinese speakers and aged 18 or above, had lived in Hong Kong for at least seven years, and agreed to provide online informed consent and participate in an anonymous online survey; no exclusion criterion was set.

The original sample included 418 participants, but some participants did not respond to the family well-being measure (see the measure description above). Therefore, only 359 participants who answered all family well-being items were included for analysis in the present study.

Measures

Participants completed questions regarding demographic backgrounds in addition to the following self-report measures:

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACEs Questionnaire). This ACEs Questionnaire includes 10 yes/no items that assess ten different types of ACEs before 18 years old (Bruskas & Tessin, Citation2013; Reavis et al., Citation2013). A sample item is “Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often … Swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you? or Act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?” The ACEs Questionnaire had good test-retest reliability over one year in one study (Zanotti et al., Citation2018). The traditional Chinese version of the ACEs Questionnaire has been used in a previous study and has verified face validity (Fung, Ross, Yu, et al., Citation2019). The ACEs Questionnaire was internally consistent (α = .657) in this study, which is in acceptable range (Raharjanti et al., Citation2022). In addition, the factor structure of ACEs Questionnaire was examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which demonstrated a good construct reliability (H = .601) (Magnier et al., Citation2019). The total score of the ACEs Questionnaire could range from 0 to 10.

The 5-item Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ‐5). The traditional Chinese version of the SDQ-5 has acceptable reliability and good construct validity. The SDQ-5 is designed to distinguish people with or without somatoform dissociation (Chu, Citation2011). Sample items included “I have trouble urinating” and “I hear sounds from nearby as if they were coming from far away.” The traditional Chinese version of the SDQ-5 has acceptable reliability and good construct validity (Fung et al., Citation2018). The SDQ-5 was internally consistent (α = .722) in this study. In addition, the factor structure of SDQ-5 was examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which demonstrated a good construct reliability (H = .686) (Magnier et al., Citation2019). The total score of the SDQ-5 could range from 5 to 25.

The Overall Family Well-being Scale (OFWS). The OFWS is a 4-item self-report measure of current family well-being which has been used in a previous local study, the “Hong Kong Family Well-being Survey 2018” (Hong Kong Family Welfare Society, Citation2018). The measure is based largely on the conceptualization of family well-being by Poston et al. (Citation2003), with a focus on four major domains, which carried the operational definition of family well-being, including harmonious, orderly, fulfilling of family life. The four items measured current family well-being as perceived by the participants: “Overall, there is a good relationship between family members,” (family interaction); “Overall, parents care about me/children,” (parenting); “Overall, every member inside the family is happy,” (daily family life); and “The living conditions of my family can meet our needs” (financial well-being) (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The OFWS allows participants to select “not sure,” “not applicable” or “no answer;” these answers were treated as missing data in the present study. The OFWS was internally consistent (α = .854) in the present study. In addition, the factor structure of family well-being was examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which demonstrated a good construct reliability (H = .689) (Magnier et al., Citation2019). The total score of this scale could range from 4 to 20.

Data analysis

SPSS 22.0 was used to analyze the data. We first conducted a descriptive analysis to report the sample characteristics. We then conducted correlation and regression analyses to examine the relationship between ACEs and somatoform dissociation. We also used the SPSS PROCESS V3.2 macro (Hayes, Citation2018) to examine the potential moderating role of family well-being in the relationship between ACEs and somatoform dissociation. Similar to other moderation studies (e.g., Woo & Kim, Citation2020), the Johnson-Neyman method and the pick-a-point method were used to investigate the moderation effect of family well-being (Montoya, Citation2019). The Pick-a-Point method entails picking representative values of the moderator variable (e.g., high, moderate, and low) and then assessing the impact of the focal determinant at those values, whereas the Johnson-Neyman method identifies regions in the scope of the moderator variable in which the impact of the focal determinant on the outcome is significant statistically and not. Significance was set at a two-tailed p-value of ≤ 0.05.

Results

All participants were Hong Kong residents who had lived in Hong Kong for at least seven years. More than half of them (67.6%) were female, 112 (31.3%) were male, and four (1.1%) identified themselves as transgender. The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 64 (M = 27.53, SD = 8.84). Participants reported an average of 1.78 ACEs (SD = 1.76); 29.5% reported three or more ACEs. The mean SDQ-5 score was 6.62 (SD = 2.50), with 15.9% scoring above the cutoff (≥9) for somatoform dissociation.

Association between ACEs and somatoform dissociation

We found that the number of ACEs was positively associated with the SDQ-5 score (r = .271, p < .001). A multiple regression analysis revealed that childhood physical neglect (β = .241, p < .001), sexual abuse (β = .143, p = .007) and emotional neglect (β = .123, p = .034) were significantly associated with somatoform dissociation symptoms ().

Table 1. Regression analysis predicting somatoform dissociative symptoms (N = 359).

The moderating effect of family well-being

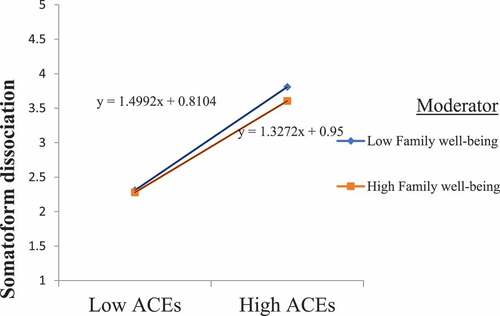

Moderation is a circumstance whereby the association between two constructs is not constant and is affected by the values of a third variable known as a moderator variable (Liu & Yuan, Citation2021). We examined whether family well-being would moderate the relationship between ACEs and somatoform dissociation (). The results showed that the interaction effect of family well-being and ACEs (β = −.043, S.E. = .02, p < .05) accounted for 10.9% of the variance in somatoform dissociation with a medium effect size (f2 = .33) ( and ). The Johnson-Neyman method results revealed a significant conditional effect of ACEs on somatoform dissociation when the OFWS score was ≤ 12.10.

Table 2. Moderator analysis of the effects of family well-being on somatoform dissociation.

The simple-slope analysis revealed that as the family well-being scores increased, the positive effects of ACEs on somatoform dissociation decreased. Individuals with more ACEs were more likely to have higher levels of somatoform dissociation if their OFWS scores were lower ().

Discussion

This study found that specific ACEs – including sexual abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect – were significantly associated with somatoform dissociation and the relationship between the number of ACEs and somatoform dissociation was moderated by the level of family well-being. Our findings are consistent with the betrayal trauma theory which proposes that certain ACEs (sexual abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect) before 18 years old are positively associated with somatoform dissociative symptoms. Yet, this association can be moderated by current family well-being as perceived by the participants. This study has looked at social moderators that may buffer the effects of ACEs on somatoform dissociation. As noted, there is a lack of studies on the mechanisms behind the relationship between ACEs and dissociation, especially somatoform dissociation. In one previous study, Narang and Contreras (Citation2005) reported that affective family environment moderated the relationship between abuse history and dissociation in a sample of mothers (N = 76). Our findings support the idea that somatoform dissociation is not only associated with trauma exposure, but also family dynamics and relationships (Fung et al., Citation2023; Ozturk & Erdogan, Citation2021). Even if a person was exposed to adversities before 18 years old, they are less likely to develop somatoform dissociative symptoms if there is a supportive family environment.

Moreover, the medium significant moderating effects of family well-being imply that family education and interventions may be a potentially important approach to preventing somatoform dissociation developing after ACEs, but further investigation is necessary. For example, it might be beneficial if the family members know how to support each other, maintain healthy boundaries, and communicate peacefully (e.g., learning nonviolent communication) (Cheung et al., Citation2022). Parents and siblings might also learn how to take care of a family member who has encountered ACEs, and how to use emotional regulation techniques or coping skills (e.g., grounding) to manage the symptoms (e.g., flashbacks, depersonalization, psychogenic pain) of the family member. If a family member is also a perpetrator, risk assessment should take place and professional interventions should be considered. However, it is also possible that the participants with higher levels of family well-being had lower SDQ-5 scores because there was less betrayal trauma experienced by them, and/or there was more secure attachment to caregivers (Bailey & Brand, Citation2017).

In addition, the present study points to the importance of further investigating the potential effects of family environment. Future studies should further examine which types of family members and support can buffer the impacts of ACEs on trauma-related symptoms. Once we have more understanding of the role of family well-being, we could develop and evaluate the use of specific trauma and dissociation-informed family interventions to prevent and treat dissociative symptoms in trauma-exposed populations. Sometimes social support can be even more important than therapy for trauma survivors (Fung, Ross, & Ling, Citation2019; Herman, Citation1992). Family and social interventions are theoretically and clinically relevant to the treatment of dissociation, but surprisingly there is a lack of studies in this regard (Fung, Ross, et al., Citation2022). The findings of the present study call for more studies on the specific components of family aspects (i.e. financial security, family connection, attachment styles) of specific trauma-related symptomology (i.e. somatoform dissociation), as this research line may offer new hope and direction for buffering the effects of ACEs on dissociation.

While a local study showed that emotional abuse was the strongest predictor of somatoform dissociation symptoms (Fung, Ross, Yu, et al., Citation2019), the present study has different findings – physical neglect, sexual abuse and emotional neglect, but not emotional abuse, were associated with somatoform dissociation symptoms in our sample. Therefore, it remains unclear which types of ACEs are particularly associated with somatoform dissociation even in the same cultural context; further investigation is needed.

The study has several limitations. First, the study relied on brief self-report measures. Second, data were collected in a convenience sample. Third, the cross-sectional design did not allow us to infer causality. Fourth, we did not assess other important types of ACEs in the study (e.g., poverty, impacts of pandemic) (data were collected in 2018 to 2019). Fifth, the OFWS is a measure of general family well-being as perceived by the participants – although similar measures have been used in population health studies, the perception of family well-being might be partly influenced by the emotional state of the participants. Thus, further research on the moderating effects of various psychosocial variables is needed. Sixth, the lack of psychometric studies on the OFWS was also a limitation of the present study, although this was found to be a reliable measure with acceptable factorial validity. Seventh, family environment is complex, especially in the context of ACEs. In most cases, ACEs take place during childhood inside one’s family (Turner et al., Citation2020). Future study could consider friends as protective effects of social support.

Concluding remarks

In this paper, we discuss the important role of family environments in trauma recovery. We reported the findings of a preliminary study, which found that there was a medium moderating effect of family well-being on the relationship between ACEs and somatoform dissociation. This study explored the potential moderators between ACEs and dissociation. The limitations of the study should be considered when interpreting the findings. Our findings point to the potential importance of taking family environments into account when preventing and treating trauma-related dissociative symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author, HWF, received The RGC Postdoctoral Fellowship Scheme 2022/2023 from the Research Grants Council (RGC) of Hong Kong.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amato, P. R., & Partridge, S. (1987). Widows and divorcees with dependent children: Material, personal, family, and social well-being. Family Relations, 36(3), 316–320.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). text revision. American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Bailey, T. D., & Brand, B. L. (2017). Traumatic dissociation: Theory, research, and treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 24(2), 170. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12195

- Bartlett, J. D., & Sacks, V. (2019). Adverse Childhood Experiences are Different Than Child Trauma, and It’s Critical to Understand Why. https://www.childtrends.org/blog/adverse-childhood-experiences-different-than-child-trauma-critical-to-understand-why

- Brand, B. L., & Loewenstein, R. J. (2010). Dissociative disorders: An overview of assessment, phenomenology, and treatment. Psychiatric Times, 27(10), 62–69.

- Brown, R. J., Cardeña, E., Nijenhuis, E., Sar, V., & Van Der Hart, O. (2007). Should conversion disorder be reclassified as a dissociative disorder in DSM–V? Psychosomatics, 48(5), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.369

- Bruskas, D., & Tessin, D. H. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences and psychosocial well-being of women who were in foster care as children. The Permanente Journal, 17(3), e131. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-121

- Carlson, J. S., Yohannan, J., Darr, C. L., Turley, M. R., Larez, N. A., & Perfect, M. M. (2020). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in school-aged youth: A systematic review (1990–2015). International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 8(sup1), 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2018.1548397

- Cheung, C. T. Y., Cheng, C. M.-H., Lam, S. K. K., Ling, H. W. H., Lau, K. L., Hung, S. L., & Fung, H. W. (2022). Reliability and validity of a novel measure of nonviolent communication behaviors. Research on Social Work Practice, 104973152211285. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315221128595

- The Childhood Adversity Narratives. (2015). Opportunities to change the outcomes of traumatized children. [ BOOK]. http://static1.squarespace.com/static/552ec6c7e4b0b098cbafba75/t/56915f539cadb61a0a0d94a2/1452367700722/CAN_Narrative_1-5-16-v4L.pdf

- Chu, J. A. (2011). Appendix 2: The somatoform dissociation questionnaire (SDQ-20 and SDQ-5). Rebuilding Shattered Lives, 282.

- Dalenberg, C. J., Brand, B. L., Gleaves, D. H., Dorahy, M. J., Loewenstein, R. J., Cardena, E., … Spiegel, D. (2012). Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(3), 550–588. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027447

- Dewar, M., Paradis, A., & Fortin, C. A. (2020). Identifying trajectories and predictors of response to psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: A systematic review of literature. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(2), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719875602

- Evans, S. E., Steel, A. L., & DiLillo, D. (2013). Child maltreatment severity and adult trauma symptoms: Does perceived social support play a buffering role? Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(11), 934–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.005

- Evans, S. E., Steel, A. L., Watkins, L. E., & DiLillo, D. (2014). Childhood exposure to family violence and adult trauma symptoms: The importance of social support from a spouse. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 6(5), 527. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036940

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., … Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study [themepage]. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-37979800017-8

- Ferrajão, P. C. (2020). The role of parental emotional validation and invalidation on children’s clinical symptoms: A study with children exposed to intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Trauma, Child Custody & Child Development, 17(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15379418.2020.1731399

- Fredette, C., El-Baalbaki, G., Palardy, V., Rizkallah, E., & Guay, S. (2016). Social support and cognitive–behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Traumatology, 22(2), 131. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000070

- Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Harvard University Press.

- Freyd, J. J. (2008). Betrayal Trauma. In G. Reyes, J. D. Elhai, & J. D. Ford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of psychological Trauma. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fung, H. W., Chien, W. T., Chan, C., & Ross, C. A. (2022). A cross-cultural investigation of the association between betrayal trauma and dissociative features. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 1630–1653. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221090568

- Fung, H. W., Chien, W. T., Lam, S. K. K., & Ross, C. A. (2022). The relationship between dissociation and complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 152483802211208. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221120835

- Fung, H. W., Choi, T. M., Chan, C., & Ross, C. A. (2018). Psychometric properties of the pathological dissociation measures among Chinese research participants – a study using online methods. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 15(4), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2018.1456995

- Fung, H. W., Chung, H. M., & Ross, C. A. (2020). Demographic and mental health correlates of childhood emotional abuse and neglect in a Hong Kong sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 99, 104288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104288

- Fung, H. W., Geng, F., Yuan, D., Zhan, N., & Lee, V. W. P. (2023). Childhood experiences and dissociation among high school students in China: Theoretical reexamination and clinical implications. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640231181528

- Fung, H. W., Ross, C. A., & Chung, H. M. (2020). The possibility of using dissociation to identify mental health service users with more psychosocial intervention needs: Rationale and preliminary evidence. Social Work in Mental Health, 18(6), 623–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2020.1832642

- Fung, H. W., Ross, C. A., Lam, S. K. K., & Hung, S. L. (2022). Recent research on the interventions for people with dissociation. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6(4), 100299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2022.100299

- Fung, H. W., Ross, C. A., & Ling, H. W. H. (2019). Complex dissociative disorders in social work: Discovering the knowledge gaps. Social Work in Mental Health, 17(6), 682–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2019.1658689

- Fung, H. W., Ross, C. A., Yu, C. K.-C., & Lau, E. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and dissociation among Hong Kong mental health service users. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(4), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1597808

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A. (2020). The relationship between child sexual abuse, self-concept and psychopathology: The moderating role of social support and perceived parental quality. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104938

- Giller, E. (1999). What is psychological trauma? https://www.sidran.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/What-Is-Psychological-Trauma.pdf

- Gonzalez Vazquez, A. I., Seijo Ameneiros, N., Díaz Del Valle, J. C., Lopez Fernandez, E., & Santed Germán, M. A. (2017). Revisiting the concept of severe mental illness: Severity indicators and healthcare spending in psychotic, depressive and dissociative disorders. Journal of Mental Health, 29(6), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1340615

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, mederation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guideford Press.

- Henschel, S., Doba, K., & Nandrino, J. L. (2019). Emotion regulation processes and psychoform and somatoform dissociation in adolescents and young adults with cumulative maltreatment. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(2), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2018.1502714

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

- Hong Kong Family Welfare Society. (2018). Hong Kong Family Well-being Survey Report 2018 (in Chinese: 香港家庭幸福感調查 2018). https://www.hkfws.org.hk/assets/files/reserch_reports/hongkongfamilywell-beingsurveyreport2018.pdf

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., … Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-26671730118-4

- Kate, M. A., Hopwood, T., & Jamieson, G. (2020). The prevalence of dissociative disorders and dissociative experiences in college populations: A meta-analysis of 98 studies. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 21(1), 16–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1647915

- Kienle, J., Rockstroh, B., Bohus, M., Fiess, J., Huffziger, S., & Steffen-Klatt, A. (2017). Somatoform dissociation and posttraumatic stress syndrome–two sides of the same medal? A comparison of symptom profiles, trauma history and altered affect regulation between patients with functional neurological symptoms and patients with PTSD. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1414-z

- Lagdon, S., Armour, C., & Stringer, M. (2014). Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 24794. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.24794

- Liu, H., & Yuan, K. H. (2021). New measures of effect size in moderation analysis. Psychological Methods, 26(6), 680. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000371

- Magnier, L., Mugge, R., & Schoormans, J. (2019). Turning ocean garbage into products–Consumers’ evaluations of products made of recycled ocean plastic. Journal of Cleaner Production, 215, 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.246

- McCabe, C. T., Watrous, J. R., & Galarneau, M. R. (2020). Trauma exposure, mental health, and quality of life among injured service members: Moderating effects of perceived support from friends and family. Military Psychology, 32(2), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2019.1691406

- McPherson, K. E., Kerr, S., McGee, E., Morgan, A., Cheater, F. M., McLean, J., & Egan, J. (2014). The association between social capital and mental health and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: An integrative systematic review. BMC Psychology, 2(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7283-2-7

- Montoya, A. K. (2019). Moderation analysis in two-instance repeated measures designs: Probing methods and multiple moderator models. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1088-6

- Mueller-Pfeiffer, C., Schumacher, S., Martin-Soelch, C., Pazhenkottil, A. P., Wirtz, G., Fuhrhans, C., … Rufer, M. (2010). The validity and reliability of the German version of the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20). Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 11(3), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299731003793450

- Narang, D. S., & Contreras, J. M. (2005). The relationships of dissociation and affective family environment with the intergenerational cycle of child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(6), 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.003

- Nijenhuis, E. R. (2001). Somatoform dissociation: Major symptoms of dissociative disorders. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 1(4), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v01n04_02

- Nijenhuis, E. R., Spinhoven, P., van Dyck, R., Van der Hart, O., & Vanderlinden, J. (1998). Degree of somatoform and psychological dissociation in dissociative disorder is correlated with reported trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11(4), 711–730. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024493332751

- Nijenhuis, E. R., & Van der Hart, O. (2011). Defining dissociation in trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12(4), 469–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2011.570599

- Ozturk, E., & Erdogan, B. (2021). Betrayal trauma, dissociative experiences and dysfunctional family dynamics: Flashbacks, self-harming behaviors and suicide attempts in post-traumatic stress disorder and dissociative disorders. Medicine Science | International Medical Journal, 10(4), 1526–1556. https://doi.org/10.5455/medscience.2021.10.342

- Piedfort-Marin, O. (2019). Synthesis and realization (personification and presentification): The psychological process of integration of traumatic memories in EMDR psychotherapy. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 13(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.13.1.75

- Poston, D., Turnbull, A., Park, J., Mannan, H., Marquis, J., & Wang, M. (2003). Family quality of life: A qualitative inquiry. Mental Retardation, 41(5), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765200341<313:Fqolaq>2.0.Co;2

- Pullin, M. A., Webster, R. A., & Hanstock, T. L. (2014). Psychoform and somatoform dissociation in a clinical sample of Australian adolescents. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2013.828149

- Raharjanti, N. W., Wiguna, T., Purwadianto, A., Soemantri, D., Indriatmi, W., Poerwandari, E. K., … Levania, M. K. (2022). Translation, validity and reliability of decision style scale in forensic psychiatric setting in Indonesia. Heliyon, 8(7), e09810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09810

- Reavis, J. A., Looman, J., Franco, K. A., & Rojas, B. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences and adult criminality: How long must we live before we possess our own lives? The Permanente Journal, 17(2), 44–48. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-072

- Ross, C. A. (2007). The trauma model: A solution to the problem of comorbidity in psychiatry. Manitou Communications.

- Scalabrini, A., Mucci, C., Esposito, R., Damiani, S., & Northoff, G. (2020). Dissociation as a disorder of integration–On the footsteps of Pierre Janet. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 101, 109928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109928

- Smith, P., Dalgleish, T., & Meiser‐Stedman, R. (2019). Practitioner Review: Posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(5), 500–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12983

- Struck, S., Stewart-Tufescu, A., Asmundson, A. J. N., Asmundson, G. G. J., & Afifi, T. O. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) research: A bibliometric analysis of publication trends over the first 20 years. Child Abuse & Neglect, 112, 104895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104895

- Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., & Henly, M. (2020). Strengthening the predictive power of screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in younger and older children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107, 104522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104522

- Van der Hart, O. (2021). Trauma-related dissociation: An analysis of two conflicting models. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(4), 100210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100210

- Van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R., & Steele, K. (2005). Dissociation: An insufficiently recognized major feature of complex posttraumatic stress disorder [PAPER]. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20049

- Van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R., & Steele, K. (2006). The haunted self: Structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. W.W. Norton.

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

- Waite, R., & Ryan, R. A. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences: What students and health professionals need to know. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429261206

- Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

- Woo, C. H., & Kim, C. (2020). Impact of workplace incivility on compassion competence of Korean nurses: Moderating effect of psychological capital. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(3), 682–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12982

- Zanotti, D. C., Kaier, E., Vanasse, R., Davis, J. L., Strunk, K. C., & Cromer, L. D. (2018). An examination of the test–retest reliability of the ACE-SQ in a sample of college athletes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 10(5), 559. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000299