Abstract

This article examines the public, private, and nonprofit facilitators at play in the growing field of impact investing, explores their roles, and proposes market rationales for their involvement. We identify four types of facilitation in which actors may participate. Enabling, improving, moving, and launching facilitation types are developed, and case examples of each are mapped to this framework. This article is the first step in creating a broader model of the impact investing marketplace, which will assist market actors in identifying the optimal or most efficient investment for both investor and investee. By envisioning the landscape of facilitation, we can begin to imagine the optimal type of facilitation as well as the facilitator best suited to undertake it for a particular investment.

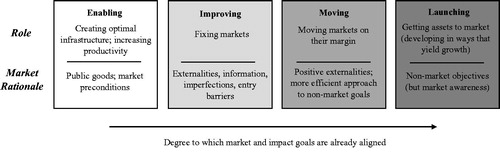

A large number of actors are now at play in the emerging marketplace of impact investing, which includes among others a multinational group of national governments and local government agencies; nonprofit organizations and foundations; for-profit corporations; asset managers; and institutional investors (Littlefield, Citation2011; Tekula & Shah, Citation2016). A growing body of literature examines impact investment as an emerging asset class (Lehner, Citation2016; Nicholls, Paton, & Emerson, Citation2015), yet one area with significant theoretical and practical implications that warrants close observation and study is the facilitation of this marketplace. This article examines the facilitators at play in the growing field of impact investing and explores roles and market rationales for their involvement. We propose four facilitation types across a spectrum of the degree to which market and impact goals are already aligned: enabling, improving, moving, and launching.

This theory and study contributes to the public administration, public policy, and nonprofit literature in two ways: first, it addresses a gap in the literature around the facilitation of impact investments; second, it moves toward more theoretical development in impact investment research.

An emerging marketplace

The roots of social finance can be traced at least to the mid-1700s when the Quakers prohibited members from participating financially in the slave trade (Royal Bank of Canada, Citation2010). In the late 1900s, concerns about the environment and sustainability inspired many socially conscious investors. Yet during this period, socially responsible investing typically took a passive role of simply screening possible investments for businesses and funds that did not meet a certain standard, like tobacco, firearms, and alcohol, while encouraging responsibility via shareholder activism. During the last half of the twentieth century, social investing evolved through movements like fair trade, corporate social responsibility, and the microfinance market to a more proactive approach. This evolution in business “upends the recent belief . . . that businesses should focus on shareholder value while nonprofits should work on social value, and government should deliver public value” (Barman, Citation2016, p .1). While controversial, the broad commercialization of the social sector in the last few decades represents a major shift (Edwards, Citation2008; Spiess-Knafl & Aschari-Lincoln, Citation2015; Weisbrod, Citation1998) and a variety of potential partnerships between market actors in the pursuit of social and financial returns.

As social finance has evolved, diverse investors, including nonprofits like foundations and venture philanthropies (Moody, Citation2008; Van Slyke & Newman, Citation2006), for-profits like financial firms, and state governments have entered the marketplace, using a variety of debt, equity, and guarantee vehicles (Chowdhry, Davies, & Waters, Citation2016; Höchstädter & Scheck, Citation2015). While a generally accepted notion of an impact investee is harder to identify (Höchstädter & Scheck, Citation2015), nonprofits and social enterprises, which work to create financial returns under a social mission (Besley & Ghatak, Citation2017; Katz & Page, Citation2010), feature prominently in impact investing. As these social enterprises seek funding, governments, charitable foundations, philanthropists, and high net-worth individuals play a role of first mover (Milligan & Schöning, Citation2011; Spiess-Knafl & Aschari-Lincoln, Citation2015; Sunley & Pinch, Citation2012) by providing grants and first-loss capital during early stages of enterprise development. As these social enterprises and socially responsible businesses become financially viable and scale their operations, they have an opportunity to take on larger and somewhat more traditional capital, now referred to as impact investments.

To date, much of the literature on impact investing considers the range of investors, investees, financial vehicles, and investment processes. As such, there is a sufficient foundation for thinking about impact investing as constituting a marketplace of various investors and investees seeking particular returns. Already, estimates of the market potential of impact investing range from $400 billion to $1 trillion in invested capital (O’Donohoe, Leijonhufvud, & Saltuk, Citation2010, p. 11; Sardy & Lewin, Citation2016), suggesting the need for a comprehensive theoretical approach to examining facilitation. This article will take first steps toward developing a model of the types of facilitation in the impact investing marketplace, after reviewing the foundational work upon which such an understanding of the marketplace is built.

Defining impact investing

As the field grows, it becomes increasingly important to define clearly impact investing. As such, impact investing is part of a broader movement to make capitalism more socially inclusive (Dacin, Dacin, & Tracey, Citation2011; Höchstädter & Scheck, Citation2015). The Rockefeller Foundation coined the term “impact investing,” when it convened financial, foundation, and development leaders in Italy in 2007 (Harji & Jackson, Citation2012; Kozlowski, Citation2012). More recent efforts have attempted to define the practitioner and academic understandings of impact investing that emerged in the decade since, differentiating it from similar movements like SRI (socially responsible investing) and CSR (corporate social responsibility) (Höchstädter & Scheck, Citation2015). As Höchstädter and Scheck’s (Citation2015) review of impact understandings conveys:

[I]mpact investing is generally defined around two core elements: financial return and some sort of non-financial impact. The return of the invested principal appears to be a minimum requirement. Generally, however, there are no limitations with regard to the expected level of financial return, that is, whether it must be below, at, or above market rates. With regard to the non-financial impact, impact investing is typically defined around a social and/or environmental impact. In addition, a number of definitions further require that the non-financial return be intentional and measurable or measured, respectively. (Höchstädter & Scheck, Citation2015, p. 454)

Essentially, impact investing is dual purpose financing: the pursuit of both social benefit and financial profit (Marlowe, Citation2014; Tekula & Shah, Citation2016). This notion of profitable solutions to social and civic problems is interesting both to investors already committed to responsible investing, and to individuals and institutions new to social finance. Beyond a more passive or filtering “do no harm” approach to socially responsible investing, impact investing is an active, intentional selection of investments in projects, funds, or companies that are projected to create measureable economic, social, or environmental impacts, while earning a relatively attractive financial return. This intentionality, or the intention of making positive impact when making an investment, has emerged as a distinctive aspect of impact investing (Addis, McLeod, & Raine, Citation2013; Boerner, Citation2012; Brown & Swersky, Citation2012).

The rise of impact investing happens at a time when there is a desire, among both individual and institutional charitable donors, for greater accountability and performance measurement from the recipients of their contributions. This expectation of evidenced, measurable social benefit is another defining characteristic of impact investing (O’Donohoe et al., Citation2010).

Growth of impact investing infrastructure

Beyond private equity investments, impact investments come in the form of a number of vehicles and instruments including private debt, deposits, guarantees, and real assets. Furthermore, new instruments have been created in this arena including community investment notes, pay-for-success bonds, and social impact bonds (SIB). The SIBs are actually not bonds in the traditional, commercial sense; rather, they are contractual obligations held (usually) by governments (Jackson, Citation2013). Chowdhry, Davies, and Waters (Citation2013) have proposed the addition of a social impact guarantee (SIG), specific to the impact investing market. The guarantee allows for a social market to be developed within a standardized market, by aligning lower financial returns to social investors when social outcomes are high, while simultaneously permitting greater monetary returns to financial investors for these same social outcomes (Chowdhry et al., Citation2013, Citation2016). Large infrastructure projects and public-private partnerships also offer unique opportunities for various investors and supporters, including both nonprofit organizations and government.

Though not a vehicle or instrument, venture philanthropy has emerged as a strategy specific to impact investing, within the nonprofit sector (Hehenberger & Alemany, Citation2017). Gordon (Citation2014) characterizes venture philanthropy as a hybrid model incorporating venture capital, developmental venture capital, and angel investing. She elaborates eight stages of venture philanthropy, beginning with deal sourcing and relationship building, participating in cocreation with the investee and finally, ending with disengagement and return, which sets it apart from traditional philanthropy. Venture philanthropies also tend to focus on more commercially oriented investees, typically social enterprises (Spiess-Knafl & Aschari-Lincoln, Citation2015). The literature on such venture philanthropy also suggests some best practices for effective philanthropic venture capital funds, such as the importance of hiring a founding team with commercial experience when attempting to maximize social and economic performance (Scarlata, Zacharakis, & Walske, Citation2016).

As the above literature suggests, much work has been done in the past decade to develop a shared understanding of impact investing, as well as the tools, and market specific investors and investees. However, much of the work to date has elaborated a singular investment, investor/investee relationship or tool. In the following section, we will attempt to think of those organizations facilitating investment in the impact investing marketplace by type, allowing for a synthesis and elaboration of the roles played by various investors throughout an investment’s life cycle. This marketplace view is particularly necessary when considering whether and how impact investing is capable of meeting the perceived promise of creating social value and producing profit for investors in market-based partnerships between philanthropic funders, traditional investors (Barman, Citation2016, p. 199), and government entities.

Facilitators

At this nascent stage, a spectrum of facilitators including governments, the private sector, innovative foundations, hubs, and academic institutions, all play a part in the growth of impact investing (Tekula et al., Citation2015). For the purposes of this article, we define facilitators as those organizations stimulating the growth of social enterprises and nonprofits and assisting them in attaining scale, such that they are fundable by larger impact investors. We contend that facilitators help organizations in this market through enabling, improving, moving, and launching assets to market. Not only do facilitators play multiple roles, they also come from multiple sectors themselves. By envisioning the landscape of facilitation, we can begin to imagine the optimal type of facilitation as well as the facilitator best suited to undertake it for a particular investment. Further, facilitators often work together, either jointly or consecutively, thus emphasizing the importance of considering them collectively. Government, nonprofit, and private finance organizations all play one or more of the roles—enabling, improving, moving, and launching—aforementioned.

It is possible to delve more deeply into certain aspects of mediation in the impact investment sector. The goal of this section is to propose a framework in order to fine-tune and develop the study of the role of facilitators in the impact investing marketplace, and the market rationale for each stage and type of involvement.

Depending on the degree to which market and impact goals are already aligned, government and nonprofit facilitators can play a number of different roles in the impact investing marketplace. illustrates this continuum and the associated characteristics of each type. Although these four types of facilitation do not capture the full spectrum of roles that nonprofits and government can play in the impact investing marketplace, they illustrate critical differences.

We propose four categories of facilitation types: enabling, improving, moving, and launching. There are several broad implications to these types of facilitation. First, facilitation may be seen as a strategic response in the sense that it is targeted toward an increase in social benefit, following market rationales by addressing externalities, imperfections, and entry barriers not only by supportive legislation and risk-sharing, but also by seeding impact investments.

Facilitation type: Enabling

When facilitators play an enabling role in the impact investing marketplace, they work to create optimal infrastructure and increase productivity. The market mechanism underlying this behavior is one of the creation of public goods and market preconditions. This type of facilitation is typically undertaken by governments through the provision of property rights, and by partnering on and supporting large transportation and infrastructure projects. Both nonprofit and government agencies can play a grantmaking role when enabling impact investments. maps government, trade association, philanthropy and private capital examples to the enabling type of facilitation, along with the other facilitation types improving, moving, and launching.

Table 1. Facilitation Types, Roles, Market Rationales, and Examples.

Governments play a policy, regulatory, and investor role by stimulating supply, directing capital, and regulating demand (Martin, Citation2016). In a specific example, a government may enter into a social impact bond, which typically functions as a contract paying for specific social outcomes (e.g., reduced prison recidivism rate). In this model, investors fund the cost of running the program that creates the social outcomes, and government pays the investors the services plus a financial return if the outcome targets are met. The risk associated with outcome performance may be “transferred to the investors or shared among the stakeholders (investors, philanthropy, service providers, and the public sector)” (Godeke & Resner, Citation2012, p. 5). This example demonstrates the interplay of facilitators, in addition to the facilitation enabling the SIB project.

As the markets for social finance have emerged, there is a growing focus of government policies and initiatives on the support of impact investing. The United Kingdom has seen the development of a Social Investment Task Force, while Canada has developed a Ministerial Advisory Council on Social Innovation and the United States has a Social Innovation Fund. In 2013, building upon the United Kingdom’s role as a global leader in social innovation development and domestic innovations such as Big Society Capital, during the UK presidency of the G8, former Prime Minister David Cameron announced a Social Impact Investment Taskforce aiming to “catalyze the development of the social impact investment market” (Social Impact Investment Taskforce, Citation2014). This initiative brought together government officials and leaders from G8 nations’ finance, business, and philanthropy sectors, holding its first meeting at the White House in the autumn of 2013 forming several working groups: (1) impact measurement, (2) asset allocation, (3) international development and impact investing, and (4) mission alignment (Social Impact Investment Taskforce, Citation2014).

Also in 2013, the United States Small Business Administration (SBA) announced that it would increase its impact investment funds from $80 million to $150 million. The following year, in 2014, the White House hosted a number of roundtable discussions on the topic of impact investing, while the Obama Administration committed to catalyzing additional private sector impact investments and supporting the involved companies and entrepreneurs (Office of Science and Technology Policy [OSTP], Citation2014a, p. 2). These commitments included an increase of the reach and flexibility of the SBA Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) Impact Fund, an U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) managed $60 million loan guarantee facility green base-of-the-pyramid serving businesses, and pay-for-success field-building support through the Social Innovation Fund (SIF) (OSTP, Citation2014b).

Pay-for-success bonds (PFS) and social impact bonds (SIB) were developed in the United Kingdom through a unique public-private partnership and designed as a vehicle to catalyze private capital toward advancing social good. These bonds can be developed in a process whereby a public sector entity identifies a discrete social or environmental issue to be addressed, defines a specific measurable outcome with a timeline, and contracts an external organization to (1) hire a reputable nonprofit to provide services to achieve the outcomes, and (2) convene funders, philanthropic or private investors, to provide the working capital needed to fund the service providers’ programs (Shah & Costa, Citation2013). As defined by the contract, an independent evaluator then measures and verifies the outcomes. If the outcomes are achieved, the public-sector entity repays the invested principal, plus an agreed return for taking on the financial risk. When a contracted outcome is not achieved, there is no payout, and investors lose their principal.

From developing legislation and providing incentives to creating supportive frameworks and leveraging agency funding, there is a growing number of success stories of policy-makers effectively calling attention to the field and setting standards, and thus motivating investors to join the sector. In these ways, government can play many roles in the sector: underwriter; coinvestor; regulator; procurer of goods and services; provider of subsidies; and supplier of technical assistance.

Government case example: Enabling

In January 2014, the State of Massachusetts announced a pay-for-success program targeted at reducing youth crime. This intervention raised $18 million dollars from private funders including the Goldman Sachs Social Impact Fund and the Kresge Foundation. An external organization, Third Sector Capital Partners, manages the project. A nonprofit youth intervention group, Roca, acts as the service provider. Roca’s youth intervention program has a proven track record, including mechanisms to measure and report on outputs and outcomes. With the working capital injection, Roca will work with almost one thousand young men recently released or about to be released from jail with the goal of reducing repeat criminal violations and prison terms. The contracted outcome is a reduction in number of incarceration days by 40% over the seven year contracted period, as measured by an independent third party evaluator. If this is achieved by 2019, the State of Massachusetts will pay principle plus some interest to the private investors; this amount is roughly equal to the estimated money the State would save through the decrease in incarceration days (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Citation2014). While the enabling role for government as intermediary in impact investments can come with considerable risks, in a case study exploring the contractual risks and transaction costs of this project, Pandey, Cordes, Pandey, and Winfrey (Citation2018) found the contract to contain “high levels of contractual specificity, multiple oversight provisions, and procedural rigidity to reduce the likelihood of opportunistic behavior by any party” (p. 18).

Facilitation type: Improving

Improving facilitation essentially fixes markets with an underlying market rationale around externalities, information imperfection, and entry barriers. In the impact investing arena, government examples include regulations, supportive legislation, credit guarantees, and safe harbor provisions. Nonprofits playing an improving role may develop impact metrics, provide technical assistance, and convene actors in the field.

All of these facilitators address the critical issue of matching investors with investees. The available supply of capital seeks attractive financial returns and positive social, economic or environmental impact; and social enterprises are not independently poised to absorb the available financial support (Rutherford & von Glahn, Citation2014). For government, the key to managing “indirect governance” is its ability to balance the costs and benefits of contracting out service delivery or production to private corporations and nonprofit organizations (Kettl, Citation2002). Government’s role in improving the impact investing market can be seen as an attempt to manage toward this balance.

For quite some time, public and private funds have relied on nonprofits as funding mediators (Benjamin, Citation2010). These organizations gather funds and regrant money, often coupling this regranting role with other services as they work to support and strengthen the nonprofit sector (Abramson & McCarthy, Citation2002; Benjamin, Citation2010; Renz, Citation2008; Szanton, Citation2003). In the policy implementation literature, researchers have investigated nonprofit intermediary organizations in the context of subcontracting (see deLeon & deLeon, Citation2002; Milward & Provan, Citation2000). The nonprofit literature has considered categories, roles, and specific nonprofit funding mediators (e.g., Brown & Kalegaonkar, Citation2002). In general, these literatures suggest that these nonprofit facilitators play strong improving roles among interorganizational partners. Yet, this literature has examined neither the emerging marketplace of impact investing nor the potential for an optimal level of facilitation.

Trade associations and hubs have emerged in the impact investing ecosystem. In addition to providing outreach, networks, connections, and research resources, they also help to grow the capacity of the market by matching investors and investees, educating, and connecting talent to the field. One such organization is the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), a 501(c)(3) started in 2008 with seed funding from the Rockefeller Foundation (GIIN, Citation2017a). They established a Global Investors’ Council that identified a lack of transparency in how funds define, track, and report social and environmental performance of their portfolios. B Lab, another nonprofit, certifies B (Benefit) Corporations, which are companies whose social and environmental performance, legal accountability, and transparency have been verified (B Lab, Citation2018). Yet another nonprofit, Toniic, provides access to global deal flows for its members, and cocreates best practice tools (Toniic, Citation2018). Apart from their work qualifying and facilitating investments, these trade associations are involved in knowledge creation in the field. For instance, the Monitor Institute’s seminal 2009 report separated the market of impact investors into “finance first” and “impact first” investors (Freireich & Fulton, Citation2009), a categorization that is still often cited. Other reports, such as the GIIN’s Annual Impact Investors Survey and Toniic’s T100 project, which partners with the University of Zurich, shape the knowledge and direction of the market. In addition to knowledge creation in the field, trade associations, such as Mission Investors’ Exchange (MIE), convene market participants at conferences, such as MIE’s 2018 National Conference: Mission Forward. Working together, these nonprofits are creating a more visible community of impact investors, as well as aggregating tools and resources to help them invest in the market and understand the impact generated by these investments.

Forecasts of potential market size are dependent upon the successful implementation of standardized and meaningful metrics for measuring social impact. However there are a multitude of challenges to creating uniform metrics (Antadze & Westley, Citation2012; Barman, Citation2016, p. 206), much less ones that meet the demand for commensurability with standard market products (Barman, Citation2016; Brandstetter & Lehner, Citation2015; Harji & Jackson, Citation2012), and much can be learned from the work of innovative nonprofits and charities that have responded to the increasing demand for performance analytics by both individual and institutional funders (Brest & Born, Citation2013).

Trade association case example: Improving

The Global Impact Investment Network (GIIN), a leader among nonprofit trade associations in the field, supports impact investment with a directory of standardized metrics for articulating social, environmental, and financial performance. The GIIN created the infrastructure of the rating system and oversees the IRIS catalog. Using it, investors can sort vetted investment opportunities by social focus area, beneficiaries, operational impact, financials, IRIS reports, and investment lenses. These filters allow impact investors to navigate potential investment opportunities according to their particular financial and social/environmental goals. The IRIS metrics came under the auspices of the GIIN in 2009 and have been modified and updated four times, to upgrade metrics focused on specific topic areas, reflect feedback submitted by IRIS users and stakeholders, and to enhance usage by clarifying optimal use of metrics (GIIN, Citation2018). IRIS metrics are also aligned with other metrics systems, including the GIIRS rating done by B Analytics, and PRISM. This is significant, because the GIIN reported in its 2017 Annual Impact Investors Survey that 57% of the 209 respondents, representing $22.1 billion invested, used IRIS aligned metrics. While they are not used universally, IRIS metrics through their development over the past decade have come to be a widely used tool for users investing billions of dollars. The development of metrics such as IRIS have improved the market by facilitating the navigation, investment, and evaluation processes for investors. While other rating systems such as GIIRS and ImpactBase have developed since IRIS and do more to answer the call for commensurability (Barman, Citation2016; Harji & Jackson, Citation2012), as the first of its kind, IRIS remains an important metric in the market aiming to facilitate standardization and ease of market entrance for new investors.

Facilitation type: Moving

Moving facilitation moves markets on their margins. In this case, the market rationale is around positive externalities, and a more efficient approach to nonmarket goals. Governments may provide tax credits, and nonprofits may provide patient capital or first-loss capital to an impact investment. Often philanthropic entities utilize this type of facilitation to de-risk investments in order to prepare them for the next stage: launching to market.

Private foundations are employing more, and sometimes all, of their endowment capital toward social impact (Tekula & Shah, Citation2016). In so doing, these foundations are using endowments as patient capital, and are potentially scaling social enterprises such that they can support investments from larger investors. However, it should be pointed out that while some tend to think of foundation support as occurring at an early stage (Milligan & Schöning, Citation2011), others find that older enterprises are more likely to have philanthropic funding (Spiess-Knafl & Aschari-Lincoln, Citation2015), demonstrating the variation of a facilitator’s types and involvement. For instance, in countries with absent government subsidies and infrastructure, new products are more expensive, resulting in social enterprises’ need for philanthropic funding for an extended period of time, usually 10–15 years (Milligan & Schöning, Citation2011). Such examples demonstrate that the role of philanthropic facilitation varies by place, and in relation to the action of other facilitators in the local market.

Along with high net-worth individuals and philanthropists, innovative nonprofit funding facilitators—often foundations—have the capacity to be first movers in the impact investing marketplace, as well as providing grant and first-loss capital during the early stages of a social enterprise as it becomes market-ready. Foundations and nonprofits can also help investees with technical assistance in the form of operational and organizational capacity, and provide access to their networks, as an enterprise becomes financially viable and scales its operations. These actions lead to harnessing and influencing nontraditional sources of capital, such as venture capital and private equity.

Foundations in the United States hold over $550 billion in assets invested in the financial markets (Roeger, Blackwood, & Pettijohn, Citation2012), and currently evolving strategies have the potential to unlock these assets toward mission and impact. A growing number of foundations are now making mission-related investments (MRI), which differ meaningfully from historically used program-related investments (PRI) in that MRI investments come from the endowment funds of the foundation, as opposed to the funds allocated for grants from the required yearly payout. These shifts in the portfolios held by foundations require a robust risk management overhaul. One of the pioneering foundations in this arena is the F.B. Heron Foundation, which has declared a move to deploy all their assets toward mission (F.B. Heron Foundation, Citation2014). Over the last few years, the Foundation has evolved from a solely grant-making approach to making a combination of grants and investments. These investments are made into both for-profit and nonprofit entities as debt and equity investments. Often they are “patient capital,” longer-term capital not requiring quick returns, and critical for early-stage enterprise development.

Philanthropy case example: Moving

The MacArthur Foundation, in collaboration with the Chicago Community Trust and the Calvert Foundation, launched an initiative to mobilize $100 million in impact investments in the Chicago area in 2016 (Benefit Chicago, Citation2018). The MacArthur Foundation invested $50 million of its own assets in the fund. The Chicago Community Trust is making an inaugural investment of $15 million in Calvert’s community notes, which will also be available to individual and organizational investors. The Calvert Foundation is issuing up to $50 million in these community investment notes, the proceeds of which will be lent to the Benefit Chicago fund, which Chicago nonprofits and social enterprises can apply to for low interest and longer-term investments.

One of Benefit Chicago’s first investments was in May 2016 to Sweet Beginnings, a for-profit subsidiary of the nonprofit North Lawndale Employment Network. This honey business employs formerly incarcerated people as beekeepers and to produce honey products online and in local stores. The program trains 20–40 former inmates at a time, and has trained 500 former inmates to date, with only a 4% recidivism rate. Sweet Beginnings is currently using a $500,000 loan from Benefit Chicago to extend the length of its training program, which provides background and job training experience that prepares participants for successful careers after graduating. The investments made by the Chicago Community Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation bring enough capital into the fund to launch it, making investments in Calvert’s community notes accessible to other business and individual investors, for as little as $20. By allocating foundation assets to this fund, these investors enable other smaller investors to enter the impact investing market and make patient capital available to nonprofits and social enterprises that would otherwise be ineligible for loans of that size and duration.

Facilitation type: Launching

Facilitators that play the role of launching act to support moving assets to market, and developing them in ways that yield growth. Here we have nonmarket objectives, but market awareness. Both government and nonprofits may provide initial capital, or seed capital, to an impact investment at this stage, however private capital most commonly plays the role of launching in the impact investing marketplace.

While much of the private capital in impact investing has been from foundations in the form of philanthropic capital or mission related investments, there is enormous potential for adoption by large financial institutions like banks and pension funds (Martin, Citation2016). While pension funds have moved quite slowly, there does appear to be public pressure for institutional investors to offer impact investing options: in 2012 a U.K. survey of 4.5 million pension holders found that 47% of respondents expected to have impact investments in their portfolios within two years (Social Finance, Citation2012, p. 4). One American pension fund, Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA-CREF), launched an impact investing unit over 10 years ago, in 2006, and by 2011 had committed over $600 million to a variety of impact vehicles (Bugg-Levine & Emerson, Citation2011). Nuveen, the investment manager of TIAA, now counts $1.1 billion in their own social impact portfolio (TIAA, Citation2018).

Private banks and family offices have also played an important role: the family office of eBay founder Pierre Omidyar helped to seed the first microfinance investment vehicles, and UBS established the Philanthropy and Values-Based Investing unit of its wealth management division in 2010 (Bugg-Levine & Emerson, Citation2011).

In the realm of investment banking, large financial institutions began to enter the impact investing marketplace over the last decade, with early movers including the Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group, JP Morgan Social Finance, and Citi Microfinance. The required deal size for these institutions is quite large, and so much of their involvement is in the areas of social impact bonds and large infrastructure projects.

In recent years, impact investing funds have emerged that invest only in companies that have social impact. Some of these include Toniic (previously described), Sonen Capital, and Impact America Fund (case example below).

Private Capital case example: Launching

Impact America Fund is a $10 million venture capital fund that invests in technology driven companies that have a mission to enhance the wellbeing of underserved communities in America. This fund evolved from Jalia Ventures, a minority-focused impact investing initiative that was founded in 2010 by Kesha Cash with the support of Josh Mailman and Serious Change, LP. Jalia executed deals through unique collaborations with large individual investors, accelerators, community organizations, and university programs. From this, Impact America, launched in 2014 with support from Prudential Financial which had recently visited the White House to announce its commitment to build a $1 billion impact investment portfolio (Impact America Fund, Citation2014).

One of Jalia’s first investments was Pigeonly, a platform that makes it easy for people to search, find, and communicate with an incarcerated loved one. Pigeonly’s founder, Frederick Hutson launched and sold his first business at 19 years old. After serving in the U.S. Air Force and leaving with an honorable discharge, he served a 4-year prison sentence for distributing 3,000 kg of marijuana. During his time in prison, Hutson discovered that inefficiencies and high prices in communicating with the outside world presented him with interesting business opportunities. Hutson began working on his idea for Pigeonly while he was living in a halfway house after being released from prison. Pigeonly’s technology reduces the cost of prison calls by 80 percent, and allows people to send their inmate contact greeting cards, letters and photos from a computer, tablet, or cell phone.

Pigeonly secured a $1 million seed round of funding from a network of investors including Jalia Ventures and Kapor Capital, the venture capital investment arm of the Kapor Center for Social Impact. At the Economist’s New York impact investing event in February 2018, Pigeonly founder Frederick Hutson was asked why his company was an “impact” firm and not simply good capitalism. Hutson replied, “I don’t look like a typical tech founder. Before impact investors backed me, mainstream investors wouldn’t give me the time of day” (Impact Alpha, Citation2018).

Conclusion

In the evolving landscape of social finance, impact investing has emerged as an important driver, with a potential for transformative growth and incredible scale. From various governmental bodies to private foundations and nonprofit associations, the impact investing ecosystem is populated by a multitude of actors, with many playing facilitating roles and brokering in the marketplace. As just one of a variety of recent approaches to generating social value alongside profit, impact investing is an important type of social finance to distinguish from Socially Responsible Investing, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Responsible Investing (Barman, Citation2016). Each of these represent different approaches to the perceived promise of the marketplace to supplement what the nonprofit sector and government have failed to do alone (Clarkin & Cangioni, Citation2016; Freireich & Fulton, Citation2009; Weisbrod, Citation1998). Impact investing is unique among social finance approaches in that it provides opportunities for each of these sectors—alone or in collaboration—to employ a market-based approach to generating dual returns.

This article provides an overview and classification of the facilitators at play in the growing field of impact investing and explores their main roles and activities. Further, we explain several financial instruments employed to cater expressly to impact investors and their concerns. This theory and study contributes to the public administration, public policy, and nonprofit literature in two ways: it addresses a gap in the literature around the limits and implications of mediation in impact investments; and, it moves toward more theoretical development in impact investment research with the intention of improving the field overall. Yet questions remain: Will impact investing grow to reach predicted market size? Can this industry ever function without heavily involved facilitators and intermediaries? Is there an optimal point of facilitation?

As with any public partnerships with the private sector, there is no such thing as unlimited risk-bearing, and incentives and performance requirements must be set out clearly, and an exit mechanism for the facilitator must be provided. For government, the key to managing “indirect governance” is its ability to balance the costs and benefits of contracting out service delivery or production to private corporations and nonprofit organizations (Kettl, Citation2002). Facilitation and mediation of impact investments runs the risk of resulting in loss of social benefit if the mediation is too weak or too strong, pro forma, or does not move assets toward market readiness. Some work is currently underway to explore this loss of social benefit which is sometimes termed “social risk” (Brandstetter & Lehner, Citation2015; Lehner, Citation2016; Moore, Westley, & Nicholls, Citation2012). An under researched area is the optimization of facilitation of impact investments. If there is an optimal point of maximum social benefit, there must also be the threat of less-than-optimal social benefit.

Martin (Citation2016) introduces the potential for impact investing to grow into an investment style rather than as an asset class. This potentiality could have an even greater reach and impact than what is currently predicted for this market. Understanding the challenges of scale and the factors limiting growth remain important areas for future exploration of the impact investing sector. In the end, facilitation of impact investments is only valuable if and when it increases social benefit.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editors, Professor Sanjay Pandey and Professor Jasmine Johnson, and all reviewers for their valuable suggestions. We further acknowledge the generous support of the Helene T. and Grant M. Wilson Center for Social Entrepreneurship. Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of their institutions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rebecca Tekula

Rebecca Tekula is an Assistant Professor in Public Administration in Pace University's Dyson College of Arts and Sciences. She also serves as the Executive Director of the Helene T. and Grant M. Wilson Center for Social Entrepreneurship at Pace University. Her research examines impact investing, social enterprise, social entrepreneurship, nonprofit economics and governance, and nonprofit management education.

Kirsten Andersen

Kirsten Andersen is a doctoral candidate in Sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research interests include meaningmaking and navigation in nascent markets, moral markets, the nonprofit sector and impact investing.

References

- Abramson, A., & McCarthy, R. (2002). Infrastructure organizations. In L. Salamon (Ed.), The state of nonprofit America (pp. 331–354). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Addis, R., McLeod, J., & Raine, A. (2013). Impact—Australia: Investment for social and economic benefit. Canberra: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Antadze, N., & Westley, F. R. (2012). Impact metrics for social innovation: barriers or bridges to radical change? Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 3, 133–150. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.726005

- Barman, E. (2016). Caring capitalism: The meaning and measure of social value. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Benefit Chicago. (2018). BenefitChicago.com. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from http://www.benefitchi.org/

- Benjamin, L. M. (2010). Mediating accountability: How nonprofit funding intermediaries use performance measurement and why it matters for governance. Public Performance & Management Review, 33, 594–618. doi:10.2753/PMR1530-9576330404

- Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2017). Profit with purpose? A theory of social enterprise. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 9, 19–58. doi:10.1257/pol.20150495

- B Lab. (2018). About B Lab. Retrieved January 23, 2018, from http://www.thegiin.org/binary-data/MEDIA/pdf/000/000/20-1.pdf

- Boerner, H. (2012). The corporate ESG beauty contest continues: Recent developments in research and analysis. Corporate Finance Review, 17, 32–36.

- Brandstetter, L., & Lehner, O. M. (2015). Opening the market for impact investments: The need for adapted portfolio tools. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5, 87–107. doi:10.1515/erj-2015-0003

- Brest, P., & Born, K. (2013). When can impact investing create real impact? Stanford Social Innovation Review, 11, 22–27.

- Brown, D. L., & Kalegaonkar, A. (2002). Support organizations and the evolution of the NGO sector. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 32, 231–258. doi:10.1177/0899764002312004

- Brown, A., & Swersky, A. (2012). The first billion: A forecast of social investment demand. London: The Boston Consulting Group, Big Society Capital.

- Bugg-Levine, A., & Emerson, J. (2011). Impact investing: Transforming how we make money while making a difference. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Chowdhry, B., Davies, S. W., & Waters, B. (2013). Designing markets for impact investing in social businesses. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from http://164.67.163.139/Documents/areas/ctr/cfi/Chowdhry_Paper%20(2).pdf

- Chowdhry, B., Davies, S. W., & Waters, B. (2016). Incentivizing impact investing. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from http://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty/bhagwan.chowdhry/iii.pdf

- Clarkin, J. E., & Cangioni, C. L. (2016). Impact investing: A primer and review of the literature. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 6(2), 135–173.

- The Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (2014). Massachusetts Launches Landmark Initiative to Reduce Recidivism: Among At-Risk Youth $27 million Initiative is Largest Financial Investment in a Pay for Success Contract in the Country. [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.thirdsectorcap.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/1.29.2014-SIF-Press-Release.pdf

- Dacin, M. T., Dacin, P. A., & Tracey, P. (2011). Social entrepreneurship: A critique and future directions. Organization Science, 22, 1203–1213. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0620

- deLeon, P., & deLeon, L. (2002). What ever happened to policy implementation? An alternative approach. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 12, 467–492. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003544

- Edwards, M. (2008). Just another emperor? The myths and realities of philanthrocapitalism. London: Demos.

- F.B. Heron Foundation. (2014). Frequently asked questions. Retrieved on October 24, from http://fbheron.org/about-us/fTQ/

- Freireich, J., & Fulton, K. (2009). Investing for social and environmental impact: A design for catalyzing an emerging industry. San Francisco, CA: Monitor Institute.

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). (2014a). Getting started with IRIS. Retrieved October 24, 2014, from https://iris.thegiin.org/guides/getting-started-guide

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). (2014b). Impact base, a database of impact investing funds, continues to attract subscribers. Retrieved November 25, from http://www.thegiin.org/binary-data/MEDIA/pdf/000/000/20-1.pdf

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). (2017). About us. Retrieved October 24 2017, from https://thegiin.org/about/

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). (2018). IRIS: Processes and principles. Retrieved January 23, 2018, from https://iris.thegiin.org/about/processes-and-principles

- Godeke, S., & Resner, L. (2012). Building a healthy & sustainable social impact bond market: The investor landscape. New York, NY: Godeke Consulting.

- Gordon, J. (2014). A stage model of venture philanthropy. Venture Capital, 16, 85–107. doi:10.1080/13691066.2014.897014

- Harji, K., & Jackson, E. T. (2012). Accelerating impact: Achievements, challenges and what’s next in building the impact investing industry. New York, NY: The Rockefeller Foundation.

- Hehenberger, L., & Alemany, L. (2017). Value-added in Venture Philanthropy vs. Venture Capital: Uncovering the subtle differences between two apparently similar fields of practice. Retreived January 23, 2018 from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2960699

- Höchstädter, A. K., & Scheck, B. (2015). What’s in a name: An analysis of impact investing understandings by academics and practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 132, 449–475. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2327-0

- Impact Alpha. (2018). #Signal: Ahead of the curve. Retrieved from https://news.impactalpha.com/low-carbon-banking-creative-impact-virginia-is-for-entrepreneurs-overheard-at-the-economist-53be31a7406

- Impact America Fund. (2014). Firm pioneers innovative approach to maximize opportunity in underserved communities in the US through investing in high-growth entrepreneurs. [Press Release]. Retrieved from http://www.impactamericafund.com/impact-america-celebrates-launch/

- Jackson, E. T. (2013). Evaluating social impact bonds: Questions, challenges, innovations, and possibilities in measuring outcomes in impact investing. Community Development, 44, 608–616. doi:10.1080/15575330.2013.854258

- Katz, R. A., & Page, A. (2010). The role of social enterprise. Vt. L. Rev, 59, 474.

- Kettl, D. F. (2002). Managing indirect governance. In L. Salamon (Ed.), The tools of government: A guide to the new governance (pp. 490–510). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Kozlowski, L. (2012). Impact investing: The power of two bottom lines. Forbes.com. Retrieved January 23, 2018, from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/lorikozlowski/2012/10/02/impact-investing-the-power-of-two-bottom-lines/#6e1fa5f1edcc

- Lehner, O. (Ed.). (2016). Routledge handbook of social and sustainable finance. Oxford: Routledge.

- Littlefield, E. (2011). Impact investing: Roots & branches. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 6, 19–25. doi:10.1162/INOV_a_00078

- Marlowe, J. (2014). Socially responsible investing and public pension fund performance. Public Performance & Management Review, 38, 337–358. doi:10.1080/15309576.2015.983839

- Martin, M. (2016). Building the impact investing market: Drivers of demand and the ecosystem conditioning supply. In O. M. Lehner (Ed.), Routledge handbook of social and sustainable finance (pp. 672–692). Oxford: Routledge.

- Milligan, K., & Schöning, M. (2011). Taking a realistic approach to impact investing: Observations from the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Social Innovation. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 6, 155–166. doi:10.1162/INOV_a_00091

- Milward, B. H., & Provan, K. (2000). Governing the hollow state. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10, 359–379. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024273

- Moody, M. (2008). “Building a culture”: The construction and evolution of venture philanthropy as a new organizational field. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37, 324–352. doi:10.1177/0899764007310419

- Moore, M., Westley, F., & Nicholls, A. (2012). The social finance and social innovation nexus. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 3, 115–132. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.725824

- Nicholls, A., Paton, R., & Emerson, J. (2015). Social finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- O’Donohoe, N., Leijonhufvud, C., & Saltuk, Y. (2010). Impact investments, an emerging asset class. New York: J.P. Morgan Global Research (pp. 7–23, 60–63, 66–72).

- Office of Science and Technology Policy. (2014a). Background on the White House roundtable on impact investing: Executive actions to accelerate impact investing to tackle National and Global Challenges [Electronic Version]. Whitehouse.gov. Retrieved November 24, 2014, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/background_on_wh_rountable_on_impact_investing.pdf

- Office of Science and Technology Policy. (2014b). Executive actions to accelerate impact investing to create jobs and strengthen communities [Electronic Version]. Whitehouse.gov. Retrieved November 24, 2014, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/06/25/executive-actions-accelerate-impact-investing-create-jobs-and-strengthen-communities

- Pandey, S., Cordes, J. J., Pandey, S. K., & Winfrey, W. F. (2018). Use of social impact bonds to address social problems: Understanding contractual risks and transaction costs. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 28, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21307

- Renz, D. O. (2008). The U.S. nonprofit infrastructure mapped. Nonprofit Quarterly, 15(4). Retrieved June 7, 2013, from https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2008/12/21/the-us-nonprofit-infrastructure-mapped/

- Roeger, K. L., Blackwood, A., & Pettijohn, S. L. (2012). The Nonprofit Almanac 2012. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press.

- Royal Bank of Canada. (2010). An overview of impact investing. Vancouver: Phillips, Hager, & North Investment Management.

- Rutherford, R., & von Glahn, D. (2014). A fault in funding [Electronic Version]. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved November 17, 2014, from http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/a_fault_in_funding

- Sardy, M., & Lewin, R. (2016). Towards a global framework for impact investing. Academy of Economics and Finance Journal, 7, 73–80.

- Scarlata, M., Zacharakis, A., & Walske, J. (2016). The effect of founder experience on the performance of philanthropic venture capital firms. International Small Business Journal, 34, 618–636. doi:10.1177/0266242615574588

- Shah, S., & Costa, K. (2013). Social finance: A primer: Understanding innovation funds, impact bonds, and impact investing. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

- Social Finance. (2012). Microfinance, impact investing, and pension fund investment policy survey. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/pension_fund_survey_october_2012.pdf

- Social Impact Investment Taskforce. (2014). Social impact investment taskforce report [Electronic Version]. Gov.uk. Retrieved November 24, 2014, from https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/social-impact-investment-taskforce

- Spiess-Knafl, W., & Aschari-Lincoln, J. (2015). Understanding mechanisms in the social investment market: What are venture philanthropy funds financing and how? Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5, 103–120. doi:10.1080/20430795.2015.1060187

- Sunley, P., & Pinch, S. (2012). Financing social enterprise: Social bricolage or evolutionary entrepreneurialism? Social Enterprise Journal, 8, 108–122. doi:10.1108/17508611211252837

- Szanton, P. (2003). Toward more effective use of intermediaries: Practice matters. Improving Philanthropy Project, Foundation Center. Retrieved August 1, 2017 from www.fdncenter.org/for_grantmakers/practice_matters/.

- Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA). (2018). How we invest: Responsible investment. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from https://www.tiaa.org/public/why-tiaa/how-we-invest/responsible-investment

- Tekula, R., & Shah, A. (2016). Funding social innovation. In O. M. Lehner (Ed.), Routledge handbook of social and sustainable finance (pp. 125–136). Oxford: Routledge.

- Tekula, R., Shah, A., & Jhamb, J. (2015). Universities as intermediaries: Impact investing and social entrepreneurship. Metropolitan Universities, 26, 35–52.

- Toniic. (2018). Who we are. Retrieved January 23, 2018 from http://www.toniic.com/about/

- Van Slyke, D. M., & Newman, H. K. (2006). Venture philanthropy and social entrepreneurship in community redevelopment. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 16, 345–368. doi:10.1002/nml.111

- Weisbrod, B. A. (Ed.). (1998). To profit or not to profit: The commercial transformation of the nonprofit sector. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.