Abstract

This article explores an organizational design perspective of open government. A conceptual model is developed of how contingency factors, design parameters, and goals fit together in an open government organization based on two case studies in the United Kingdom and the United States. The cases are compared, and the unique and common organizational design choices are drawn out and evaluated. The countries’ political systems mean they differ in how they design open government. However, they both designed organizational structures of centralized leadership, technology-driven processes of coproduction, and co-option of existing policy networks.

Open government has become a popular form of government reform since the turn of the millennium. In many governments around the world, politicians are increasingly enthusiastic in their support for open government, seeing it as a method to boost their democratic credentials with a type of bipartisan endeavor that is difficult for political opponents to question without appearing to be antitransparency (Ingrams, Citation2017a; Schnell, Citation2017). In today’s political environment, citizens expect more in terms of government openness (Piotrowski & Van Ryzin, Citation2007). In addition to open government’s democratic appeal for politicians and citizens, its promotion of open data and access to information initiatives may help deliver better efficiency as transaction costs in government-to-government, government-to-business, and government-to-citizen activities might be reduced (Danziger & Andersen, Citation2002; Mergel, Citation2013). To realize these benefits, reforms seek to change the processes and structures of public organizations to make the exchange of information interaction with citizens, businesses, and other stakeholders more open. Reforms adopt new organizational systems for managing information, such as social media (Mergel, Citation2013), crowdsourcing, (Mergel & Desouza, Citation2013), or open data (Ingrams, Citation2017a). New work units are established, such as social media departments and public information commissioners (Howard & McDermott, Citation2016). Additionally, in less tangible ways, new rules, norms, and laws that govern administrative behavior, and structures for reporting arrangements with other public organizations or nongovernmental organizations are created (Howard & McDermott, Citation2016; Ingrams, Citation2017b).

However, despite these organizational ideas that accompany open government reforms in public administration, the potential for rational design approaches in open government has been relatively overlooked and ignored. This is an important and timely topic given that scholars have identified evidence of recurring problems in open government where organizational arrangements regarding information sharing, accountability, and decision making are under scrutiny. For example, Yu and Robinson (Citation2012) argued that the open government movement in the United States has been prone to a kind of soft transparency where public information is released to create accountability while in practice there are no internal mechanisms leading to consequences for poor decisions by public officials. Coglianese (Citation2009) and Piotrowski (Citation2017) both identified flaws in open government initiatives in that initiative leaders claim they will have a transformative effect on government and yet policymakers and administrators report very little belief in the initiatives’ internal impact on their organizations. Part of this charge of low-internal salience comes from other works, such as that of Grimmelikhuijsen and Feeney’s (Citation2017), where it was found that while open government consists of several dimensions such as accessibility, transparency, and participation, each of these dimensions responds to different institutional antecedents and influences, so that the organizational unity of open government structures and processes in practice appears very limited. All these critiques point to the puzzle of whether and how organizational changes in open government reforms reflect the ideals of open government. Policy theorists recognize that gaps between the structural realities of organizations and the rational designs that the organizations take to adopt new ideas or initiatives are a primary cause of program failure (Heeks, Citation2001; Suchman, Citation1987). Thus, it may well be that more can be done by scholars and practitioners to give explicit attention to organizational design in order to improve open government performance.

To sum up, studies of open government identify a gap in understanding of how the high-level policy ideals of open government reform relate to openness in terms of organizational designs. Therefore, this article seeks to investigate such designs in open government. Organizational design theory is a core public administration perspective and is ideally suited to answering questions about structure and performance (Aucoin, Citation1990; Clark, Citation1975; Simon, Citation1947). According to Burton and Obel (Citation2004, page xviii), organizational design is “a normative science with the goal of prescribing how an organization should be structured in order to function effectively and efficiently.” Organizational effectiveness depends on how organizations are designed to fit with their environment and goals (Mintzberg, Citation1990; Simon, Citation1973; Sinclair & Whitford, Citation2012). This article presents an explorative approach to organizational design in open government. The analysis focuses not exclusively on organizational design decisions but also on broader organizational factors of open government success, and how these shape choices. It poses the following two research questions: (1) what is organizational design in open government? (2) What organizational environments, design choices, and goals contribute to better open government performance? The research uses two cases of open government initiatives in two leading countries of open government reform, the United Kingdom and the United States. To answer the first research question, the article starts by developing a basic conceptual model of open government organizational design informed by theory. In order to answer the second research question, key environmental and design dimensions and decisions are identified, a final high-performance organizational design model is developed, and the country cases are described and contrasted to provide further clues as to how organizational design relates to environment and goals.

Theory of organizational design and open government

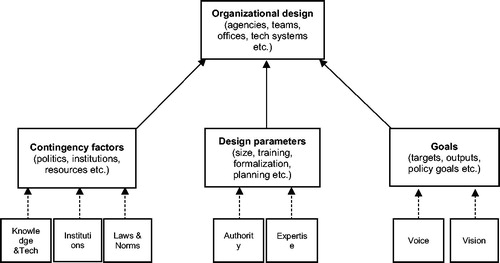

In this section, organizational design and open government literature is reviewed to develop a basic conceptual model of organizational design in open government initiatives. The discussion is structured according to Mintzberg’s (Citation1980) three organizational design components: contingency factors, design parameters, and goals.

The contingency factors of open government

While organizational design refers to the internal structure and arrangement of processes and tasks, decisions regarding these processes must necessarily take into account an organizational environment that creates constraints (Allen, Hurcan, & Queyranne, Citation2016; Mintzberg, Citation1980). Public sector reforms, such as open government reforms, must engage with this setting in order to successfully adapt to, interact with, and build on the environment (Lane & Wallis, Citation2009; Metcalfe, Citation1993). In open government reforms, contingency factors include the availability of technologies, knowledge, and skills (Evans & Campos, Citation2013), the legal and legislative rules and norms in the environment of public organizations that provide stepping stones to adoption of open government programs (Ingrams, Citation2017b), and the existing institutions that produce, manage, and use information (Dawes, Vidiasova, & Parkhimovich, Citation2016; Safarov, Citation2018).

The goals of open government

In addition to contingency factors, organizational designers consider what the organization is seeking to achieve. Organizational design theory views goals as clear and consciously thought-out objectives, outputs, or results pursued with a strategy (Mintzberg, Citation1990). In open government, goals can be specific production targets, such as reaching a targeted number of freedom-of-information requests or launching a new open data portal, as well as policy goals, such as establishing protocol for crowdsourced decision making. However, beyond these specific outputs, open government has more fundamental goals that are the ultimate purpose of open government and which the outputs should contribute to in the long term. These outcomes involve two main areas of access to information and public participation (Evans & Campos, Citation2013; Grimmelikhuijsen & Feeney, Citation2017), which Meijer, Curtin, and Hillebrandt (Citation2012) call vision and voice.

The design parameters of open government

According to Sinclair and Whitford (2012), scholars disagree widely on what parameters matter most for design decisions. Mintzberg (Citation1980) listed nine different design parameters (size, indoctrination, training, formalization, bureaucratic level, grouping, planning, liaison, and centralization), but, in a later article, recommended keeping design models as simple as possible (Mintzberg, Citation1990). For Simon (Citation1973), there are two key considerations guiding design parameters: the level of independent specialization permitted to units and the types of authority mechanisms for coordinating them, which are termed here expertise and authority, respectively. Crucially, in designing structures and process, decisions about expertise and authority must address certain tradeoffs (Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2012; Simon, Citation1947). For example, specialization of skills requires autonomy but also control (Gulick, Citation1937). Organizations with more specialist or expert units tend to have quite high autonomy and reliance on internal expertise but also higher vertical accountability systems, while less specialization of expertise may allow for more flexibility and adaptation with less vertical control (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, Citation1983; Taylor & Burt, Citation2010). Decisions regarding technology specialization are especially important in open government organizational design. The adoption of technology in organizations has led to more decentralization but simultaneously more control and reliance on information specialists (Woodward, Citation1970; Zuurmond, Citation2005).

Similar decisions about design parameters are also seen in the open government approach to authority, which tends to emphasize horizontal approaches where decisions are made with networks or task forces from civil society and the private sector (Piotrowski, Citation2017). When boundaries are relatively porous with information and public participation (as they are in open government), organizations need structures that facilitate a type of horizontal, learning management style that is responsive to the environment (Allen, Hurcan, & Queyranne, Citation2016; Lane & Wallis, Citation2009). Nevertheless, central authority may also be strong in reform movements, because political and administrative executives are in charge of the processes of change and have a strong political interest in completing the reforms (Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2012). Further, reforms involving information technology may also foster this type of centralization as greater numbers of middle managers are required (Im, Citation2011), central organizational arrangements provide institutional support to guide implementation (Piña & Avellaneda, Citation2018; Safarov, Citation2018), and standardization of software and systems may also call for a degree of centralized coordination (Dunleavy, Margetts, Bastow, & Tinkler, Citation2006).

The foregoing theoretical discussion brings together the two literature streams of organizational design and open government reform. shows a basic conceptual model of the main components of open government organizational design. The contingency factors comprise the environmental setting that is influenced by three main factors: knowledge and technology, institutions, and laws and norms. The design parameters involve the types of structural and process options available to designers. Two key decisions influence these choices in terms of authority and expertise. Finally, goals involve specific outputs and the longer-term open government goals of voice and vision.

Data and methods

It remains to explore and refine as well as to address the second research question regarding the organizational designs that contribute to better open government performance. The empirical method follows a qualitative approach using case studies of open government programs in two countries that have high-performing government at a global level in terms of openness: the United Kingdom and the United States. The countries are in the top five according to ratings of the Open Government Partnership (OGP; https://www.opengovpartnership.org), an international open government organization with over 70 participating countries. Both countries were founding members of the OGP in 2011, and, historically, were also early adopters of open government principles and values. Woodrow Wilson, who later became the US President, was one of the first public administration scholars to write about open government as a fundamental component of democratic government in 1887. The United States was also the second country worldwide to adopt a Freedom of Information Act (in 1966/1967; https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-80/pdf/STATUTE-80-Pg250.pdf; https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-81/pdf/STATUTE-81-Pg54.pdf). The United Kingdom is similarly advanced. British intellectuals, such as John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, are credited with laying the foundations of freedom of information theory in the nineteenth century (Stiglitz, Citation2002), and it is a world leader in open government data (Safarov, Citation2018).

Open government is implemented in the form of individual program initiatives that focus on a specific policy area. Thus, an open government program was selected from each of the countries; one program on policing (the US case) and one on healthcare (the UK case). The choice of program cases from each country was motivated by a different empirical rationale from the country selections. Rather than demonstrating successful or unsuccessful cases, these cases demonstrate two typical types of governmental policy areas with strong citizen relevance, and which were in the process of implementation during the course of the research, so that they could be observed. Using a purposive sampling approach, the choice of program cases aimed to answer a call from scholars to develop knowledge of transparency policies from areas of service delivery that matter to the everyday life of citizens to gain better understanding of transparency (de Fine Licht, Citation2014). Policing (e.g., de Graaf & Meijer, Citation2018; Grimmelikhuijsen & Meijer, Citation2015; Ingrams, Citation2017b) and healthcare (e.g., Evans & Campos, Citation2013; Mergel & Desouza, Citation2013) are two policy areas that have been noted by open government scholars as important cases of open government at the front line of service delivery where policy matters greatly to citizens. These considerations were discussed with the UK and US country assessors in the OGP Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM), and the IRM assessors agreed that policing and healthcare were ideal policy areas, and confirmed that these programs provided good points of access for interviews and documentary data collection. While the choice of two policy areas limits direct comparisons between the programs, it does allow for an exploration of two organizational designs that matter in the delivery of key services to citizens. A second motivating factor for the program selection was the fact that open government is a multidimensional policy area that can include one of three components: transparency, participation, and collaboration (McDermott, Citation2010; Piotrowski, Citation2017). According to Grimmelikhuijsen and Feeney (Citation2017), open government aims to combine all three components, though in practice this is not always achieved. Therefore, in this research, a requirement was set that the policy cases should exhibit program efforts to combine all three components rather than being narrowly focused on one or the other. The current OGP action plans for the countries were read. Just one healthcare and one law enforcement programs were found for the UK and the United States, respectively, but they both met the three-dimension requirement. In both cases, the lead organization(s) and the key decision makers in the organizations who are responsible for design decisions were part of the unit of analysis. In both cases, the organizational design is an ongoing process and key decision makers included officials involved in the initiation plan as well as those who made decisions during implementation.

The UK program is called Better Information About Health and Care, designed by the Cabinet Office and the UK healthcare commissioning body, NHS England. According to the policy statement on the Cabinet Office self-assessment report, the objective of the program was “improving the quality and breadth of information available to citizens to support them to participate more fully in both their own health care and in the quality and design of health services which will result in greater accountability” (UK Cabinet Office, Citation2016, page 37). The program committed to creating a patient and public participation policy network tasked with improving patient access to healthcare. In the United States, an open government program called Build Safer and Stronger Communities with Police Open Data was selected. The program was designed by the Office of Science and Technology Policy in the White House and the Office of Management and Budget. The central goal of the program was to promote awareness of open data potential in police departments by bringing together academic experts, citizens, and police chiefs to identify the main challenges and opportunities. The four stated principles of the program were: (1) treating people with dignity and respect; (2) giving individuals “voice” during encounters; (3) being neutral and transparent in decision making; and (4) conveying trustworthy motives.

The data collection took place in 2016. A purposive sample was used to identify senior level open government decision makers in the central executive bodies of the UK and United States for interview. There were 13 interviews in the UK case and 25 interviews in the US case. The individuals selected for interview were required to be senior ranking staff in the organizations directly involved in designing and implementing the open government programs. An initial list of eligible interviewees from each case was developed in consultation with the program leads at the White House and the Cabinet Office. From that stage, the remaining interviewees were identified through recommendations from the starting sample. Efforts were made to gain the perspective of decision makers inside and outside of government, and the final sample was approximately half government and half nongovernment. The interviews lasted between 40 minutes and an hour. A pilot test found that the terminology of “design,” “structure,” or “environment” caused confusion for interviewees. Thus, there were two simpler questions asked during the interview: (1) What organizational factors help open government programs to be more effective? (2) What organizational barriers prevent open government programs from being effective? The broad scope of the two questions encouraged respondents to identify a wide range of environmental and internal factors that delimit design choices in a complex organizational area. It also permitted a standardized interview structure across the interviews. In their responses, interviewees were prompted to go into detail on descriptions of the decision-making role of leaders of the program that contributed to success. Notes were taken by hand because some interviewees objected to having the conversation recorded due to their political status in the government.

To build background knowledge of the cases using diverse sources, the researcher also participated in the consultative initiatives of both countries, attended meetings between government and CSOs, and was a member of online forums and e-mail Listservs for a period of 12 months. In addition, official government policy reports and news articles were used to build a richer picture of the organizational design structures and processes involved in the initiatives. The total amount of textual material therefore comprised all the research notes taken from the fieldwork in addition to the notes from interviews with 35 decision makers (see Appendix 1 for a full list of data sources).

Results

The results are described below drawing out the main details of the cases. The discussion highlights how each design component factored into the organizational designs that were ultimately chosen. Following the theme of the interview questions, both helpful and harmful elements are explored. While the cases are examples from high-performing open government countries, the policy cases are not, and they reveal organizational designs that are by no means perfect. The flaws, as much as the successes, are noted in the analysis to bring out important design choices.

Better information about health and care in the United Kingdom

Contingency factors. The environmental setting of the Better Information About Health and Care program was shaped by recent legal and institutional reforms. In 2012, the UK Health and Social Care Act (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/pdfs/ukpga_20120007_en.pdf) mandated the forming of several new health departments tasked with increasing transparency and patient participation in setting policies and targets in the NHS. One of these agencies, NHS England, the new commissioning authority for health services, could therefore be selected as the lead organization in planning and implementing the program. Its arm’s length position in government and high level of resources meant that NHS England occupied an effective role as a network coordinator of civil society organizations (CSOs) and foundations, such as Macmillan, and other government agencies such as the health IT systems provider NHS Digital, that could make things happen despite very little formal authority.

At the time of the launch, the UK also had an advanced health data analytics sector. Popular health analytics companies and apps had begun to emerge as a result of coproduction efforts by the NHS to make data available for commercialization. These organizations were later incorporated into a decentralized, diverse, expert, but rather large and discordant network called the Stakeholder Forum involving both expert technology organizations that were interested in health open data and patient groups that were nontechnical but cared about the healthcare implications. The Forum was managed through a close partnership featuring regular meetings and monitoring to ensure delivery of results. Partnership and technology support was also available from among new specialist data organizations within the government, such as NHS Digital, that were put in control of coordinating information systems and data management efforts across government and nongovernmental actors. In this way, an overarching, transparent, data infrastructure that was relatively autonomous could be used for patient-centered delivery of healthcare metrics.

Goals. The healthcare program targeted several different goals. It aimed to add hundreds of new datasets to the UK open data portal including treatment rates at GP services and the results of clinical trials. Two patient feedback programs, Friends and Family Test (FFT) and the Patient-Centred Outcome Measurement (PCOM) tool were undertaken to deliver reviews of hospital services and cocreate health indicators with patients. These goals were strongly technology oriented, and this was reflected in the decision to give a coordinating role to NHS Digital and to co-opt exiting health technology organizations into the consultation network.

Despite good use of technology, the organization was not as well designed to serve other goals such as transparency and privacy. Advancement of these goals, a common refrain from decision makers concerned the difficulty of realizing high-quality outcomes for patient participation (“voice”) and transparency (“vision”). Decision makers noted the need to make goals clearer by designing measurement systems for the policy outputs in a way that stakeholders could agree upon and collectively monitor progress. Measurement was seen as particularly important because stakeholders disagreed on how to balance values such as transparency and privacy in the pursuit of open government goals. According to one decision maker: “open government health [practitioners] have fallen to the trap of the idea that volume equals success. As much information as you can get out as possible is seen as being the goal. This leads to spurious figures being produced about how much data is being published but they are absolutely useless.” Decision makers believed that designing measurement processes of these types were a key precondition for achieving greater outcomes of open government and that, in this respect, the health care program had fallen short.

Design parameters. Discussion of interviewees on the organizational structures and processes was predominantly focused on the topic of authority structures finding the right balance between centralization and decentralization. The Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office directed the overall plan for implementing the program, though NHS England was given responsibility for its day-to-day running. NHS England cochaired a Program Board with the chair of the Stakeholder Forum and a patient representative. The Stakeholder Forum was relied on to monitor implementation and provide technical solutions to any problems. However, the network’s commitment depended upon both high-level political reassurances from the Cabinet Office and bureaucratic responsiveness from NHS England. One decision maker said, “carrying out the work is not possible without the high-level commitment of the prime minister. All of that allows the internal motivation of the officials.”

But, while there was a clear central leadership structure with NHS England at the top, in practice, owners and managers of relevant health data were quite decentralized, being spread across different types of healthcare providers from cancer care to mental health and other national bodies such as NHS Digital. According to respondents, this structure was used because it gave teams within each agency the flexibility to use data-driven decision making where it was most needed. On the other hand, what the centralized dimension with the Cabinet Office seemed to provide was leadership, shared vision, and joined-up decision making. Another decision maker said that, “departmental ministries, rather than the office of the Prime Minister, have made the program inefficient. It requires good decentralized leadership.” The overall concern with these discussions was with achieving structural seamlessness between vertical and horizontal actors so that the leading governing actor was always placed in a central coordinating position.

Another key design choice in the structural organization of the program focused on the coordination among decision-making units in government, the private sector, and civil society. An existing network, OpenGovUK, consisting of advocacy groups, academics, and technology organizations, was co-opted for organizational support and expertise. One decision maker said, “the challenge is that you want good civil society engagement including health experts and privacy lobbyists, but there are so many organizations.” Selection among civil society partners was important, but it was not necessarily something that could or should be controlled. As the expertise and legitimacy of organizations representing patients was vital to the programs, when civil society was strongly opposed to a view of the government, the effects could be frustrating, but ultimately beneficial for the results of the program. Such an event happened when the creation of the health open data portal, Care.Data, was canceled, due to civil society and patient opposition to the inadequacy of stipulated data privacy protections. This event was an important learning moment for the program. It was vital to structure the involvement of the civil society network in a consistent and genuinely collaborative way with regular meetings and reports. Otherwise, if steps were taken without consultation, those steps might later lead to dead-ends or to being walked backward again at further expense to the material resources and trust of the collaboration.

While the Cabinet Office designed the program so that NHS England, the private sector, and civil society would work together, in practice they operated in a climate of mutual suspicion because, separately from the program, they were very competitive with each other. Here the organizational parameters faced a tradeoff between expertise and standardization of ethical rules and legal processes, and failed to find a good balance. Decision makers said that collaboration with private entrepreneurs, such as Ben Goldacre, who created the comparison Website OpenPrescribing.net, meant that open government specialization was being achieved through the private sector at a time when there was a widely reported funding gap for the NHS of billions of pounds. While this expertise could therefore be an advantage, collaboration with third-party technology experts meant that decision makers were constantly running up against the legal tension between openness and privacy. For example, one interviewee asked, “Where is the line between modernization and going over the legal line? With health data, the government argued that it would be anonymized but actually it is very difficult to do that.” A formal process for organizations to collaborate according to standard rules and procedures was lacking, though decision makers within both the government and nongovernment sides repeatedly voiced a need for such processes provided that they allowed for both entrepreneurial innovations in healthcare open government and compliance with privacy laws.

Safer and stronger communities with police open data in the United States

Contingency factors. Decision makers in the Safer and Stronger Communities with the Police Open Data program said that the creation of the program involved co-option of preexisting networks of multisectoral technology and police partnerships and civil society associations. In effect, the police program was a clever reorganization of an earlier White House project called the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing that had been subsequently expanded and given new impetus as part of the open government initiative. Many of the same organizations and actors were incorporated into the new effort, and there was already quite a well-developed technology infrastructure for community policing solutions provided by the nonprofit technology organization, Code for America.

The contingency of existing political mechanisms for addressing contentious political and social issues also shaped the available design options of the program. According to one respondent, following a spate of high-profile deaths of African American men during police operations, the “relationships between police and community had become so broken and police worried about the control of false narratives.” The local communities of the police departments became important street-level interfaces for police and citizens to address the problem of police violence. Technological resources closely integrated with the political and social needs of communities were also needed to galvanize problem solving. For example, Code for America helped work on IAPro, a digital proprietary crime information system that the network of police departments and partners could rapidly adopt. One decision maker said of police chiefs that, “It sounds like what happened was that people were able to wake up and learn about what tools are available to them in their cities from learning about other city efforts and technologies.”

Goals. Most discussion on the goals of the police program focused around the high level of ambition and impact but a comparative shortcoming in matching careful goal setting in the organizational design. At the time of the program’s launch, 26 police departments were part of the initiative, and this number had approximately doubled after a year. Despite this success, decision makers noted a lack of specificity in targets, and the idea for the organization seemed to be simply set on expansion without an idea of what this would achieve for public participation or transparency. The program had not turned their goals into measurable targets or milestones such as numbers of participating police departments, data sets, or crime reduction. Some police chiefs, such as the Dallas chief, David Brown, who was known to be a strong supporter of police open data, argued that statistics supported the effectiveness of open data as a crime reduction tool, but most decision makers opined that more time was needed to substantiate such claims. Again, interview respondents thought this focus on expansion rather than on how police departments could be held more accountable and transparent was reflected in the decision to put a small group of champions at the center of the network rather than a diverse group of experts that might be able to create better results in the long term for the goals such as accountability, transparency, and participation.

While decision makers in the program were mostly focused on organizational design to deliver quantitative measures of success, the political background of growing awareness of unauthorized uses of police force was challenging the stipulated goals of the program with tough questions about outcomes. In particular, the claim was made that many citizens, particularly in the African American community, had relatively little voice in police reforms. In the course of the interviews, it became clear that police chiefs were unsure about how to address this discrepancy between vision, in the provision of greater police data, and voice, in the provision of opportunities for community members to contribute to reform in law enforcement. Despite the general puzzlement on this point among interview respondents, two police chiefs opined that the solution was greater community participation that allowed shared definitions to be developed with community stakeholders on what types of data needed to be released to build trust.

Design parameters. Centralized authority was clearly a key organizational design decision of the program. Program leadership was placed at the top of the government executive with two agencies in the White House (Domestic Policy Council and Office of Science and Technology Policy) and the Office of Management and Budget. This vertical structure provided a coordinating mechanism for a national policy endeavor that could operate across multiple states and jurisdictions. One decision maker said: “White House meetings are often a lot of show. However, this program has been different. It has fellows who push through with things. They got the internal affairs idea from the Indianapolis police which allows them to organize and filter data. The White House initiative has focused them all in the same direction.”

A notable limitation of this centralized structure was that there were inevitable coordination problems resulting from the diversity of political, economic, and social contexts in which police departments were working in different states and cities. Police chiefs wanted to empower local citizens by asking for input on which data were needed. However, this led to local differences in practice, and coordination among the participating police departments was frustrated by a lack of standardization coding and data management practices. The White House network of police chiefs was designed to be small to address this coordination problem. A core of committed police departments would act as exemplars, which would result in a wave of new open data police departments across the country. However, in practice, the technical support available to the network was too meager to keep pace with adopters. Some police departments came under criticism for adopting poor standards, with data not in machine-readable formats or having missing fields. A further problem was that lack of expertise and the decentralized structure of the organization made it impossible to create a central database of police data, which is what national news media increasingly called for in the wake of revelations of police violence.

Another barrier was the use of different definitions used to classify data such as police actions classified as “use of force.” Attempts to create the right level of standardization across departments and to manage data using specialist tools was also frustrated by the fact that police departments seemed to be lacking in sufficient funding or in-house tech support. The fact that the program was driven primarily by the White House and the voluntary collaboration of a relatively small number of municipal police forces meant that the organizational structure relied on resources thinly spread over a large area. A data analysis tool, Socrata, had been promoted by the White House to try to solve the problem of data standardization, but not all departments could afford the cost of Socrata as funding was dependent on their cities, and, further, legal rules differed making the treatment of proprietary data uneven across the program. To meet the skills shortage, the White House relied on large ad hoc grassroots training sessions where advocates among police, academic, nonprofit, and technology company representatives met to share best practices and develop new ideas.

Similarities and differences

Finally, what can be said about the similarities and differences between the US and UK cases? The healthcare and policing programs had many similarities in their organizational design. Some differences resulted from different contingency factors, but the role of these factors was not deterministic, as designers responded actively with internal structural and process arrangements used to balance tradeoffs between vertical or horizontal decision making or selection of specialist technology providers. For example, while each case co-opted an existing civil society network, in the case of the UK it was designed to be a high expertise network in order to contribute effectively to a national data infrastructure. In contrast, in the United States, the network was quite narrow and mostly used for advocacy purposes in order to move closer toward nationwide open data adoption. Further the contingency factors in both cases provided existing civic technology capacity in the private and nonprofit sectors, supportive open government laws establishing access to information and data sharing guidance, and institutional mechanisms that were reasonably—though not always—responsive to citizens.

In terms of design parameters, both programs involved choosing horizontal arrangements with civil society to address political and social issues raised by citizens but ultimately the central executive offices of the countries, the White House and the Cabinet Office, were put at the center perhaps precisely because of the gravity of these issues. The UK network was larger and more formal with regular meetings, while the US approach was smaller, more flexible with intermittent training and technology experiments, and perhaps ultimately more cohesive and cooperative. Both relied heavily on giving autonomy to expert organizations, such as data analytics and software companies, and putting them in key partnership roles. In addition, in both cases, central information agencies were reformed to provide a more distinctly intergovernmental support role and to standardize processes across the entire program, though the healthcare program had also noted that such standardization processes were missing for addressing difficult areas such as the balance between transparency and privacy. In the United States, the technology support agency within this structure was a newly created company called 18F, and in the UK, the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) was rebranded as NHS Digital.

While both programs designed a strongly vertical authority structure, of the two programs, the police program was the least vertical as it was implemented by police departments that had volunteered to join in an earlier initiative and were therefore needed to be highly intrinsically motivated. In contrast, the healthcare program, through NHS England, did not delegate or enjoin local or regional healthcare providers to take part. In the US case, the local focus appeared to have good impacts as dozens of police departments had agreed to adopt open data programs and that number was constantly growing as the technology became more widely available, but, on the negative side, it did mean that sharing of technological resources was more limited.

Another key difference in the choice of design parameters reflected a deliberate response to the institutional environments. Both countries had high-level support from President Barack Obama and Prime Minister David Cameron in the United States and UK, respectively. However, in the United States, Obama launched the Open Government Directive using the executive power of his office (https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2010-title3-vol1/pdf/CFR-2010-title3-vol1-other-id196.pdf). While executive orders send a strong political message, that type of executive power relies on political persuasion. In contrast, in the UK the benefit of parliamentary majority for the prime minister provides influence over the main government departments in the cabinet, but only with the guidance of parliament. An arm’s length body such as NHS England has considerable resources to implement its programs but is controlled by statutory authority in its ability to act at a national level. The ability to drive national policy change in open government was therefore more limited in the UK’s organizational choices and it focused more on the facilitation of innovative open government tools by technology entrepreneurs.

Key components and decisions in high-performance open government designs

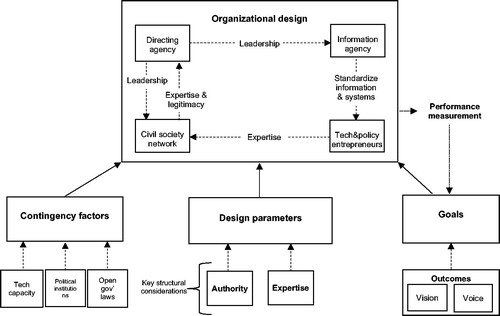

The case analysis described above is summarized in showing eleven key components of open government organizational designs. Each of the dimensions is presented according to the major three design components (contingency factors = 3; goals = 3; design parameters = 5). Each component is demonstrated using best practice examples from the cases. For example, the first component relates to Laws, such as access to information, open data, and statutory organizations with participatory functions. Examples of the types of designs in the UK and US cases that were chosen because of this contingency factor were participatory organizations in the UK (NHS England and NHS Digital) and the interagency task force in the United States (President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing).

Table 1. Key Components and Design Decisions of Open Government.

complements the 11 design components showing a final conceptual model of high-performing open government organizational design. Here, the details are fleshed out to show the relationship between contingency factors, goals, design parameters, and organizational design choices. The high-performing design parameters are informed by the two key structural considerations: authority and expertise. These two considerations each have structural tradeoffs that result in the UK and United States in four basic designs: (1) A directing agency to lead from the top; (2) A civil society network to offer expertise and legitimacy to decision-making processes; (3) Entrepreneurial organizations with skills to turn technical process into public value; and (4) A public information agency tasked with standardization of information systems and data coordination processes. The structural design of these four choices varies in the United States and the UK as a result of their unique environment, goals, and design parameters. Design structures and processes also interact dynamically with organizational understanding and management of goals. Thus, goals are now characterized by performance measurement that intervenes between outputs and outcomes. This signifies the role that performance measurement plays in turning quantifiable outputs into less quantifiable outcomes for open government. There is also a feedback arrow indicating a learning mechanism through which performance measurement informs decision makers about the right structures and processes to use for the effective pursuit of organizational goals.

Discussion

The results of the research establish a new conceptual framework of organizational design in open government and suggest some specific design choices in terms of structure that could improve open government performance. Organizational design approaches to open government have not previously been developed. While there is much more research needed to explore the specific types of designs that are possible within open government and their relative advantages and disadvantages for open government performance, the value of the approach in this article is that it demonstrates how contingency facts, goals, and design parameters fit together in examples from two important policy areas—policing and healthcare. Four major open government organizational design choices were identified in the research. Eleven components of contingency factors, goals, and design parameters help to explain how decision makers adopt these four high-performing designs. The range of qualitative sources used here does offer in-depth evidence for open government performance in terms of organizational designs. However, the type of analysis here also is broader than internal design-related concepts as it includes some important institutional, political, and technological conditions of open government performance. Here, we can further discuss each of the four major organizational design choices and their relation to contingency factors, goals, and design parameters.

First, decision makers designed an authority structure with a vertical directing agency. There was a recognized tension in vertical and horizontal structures as political leaders tried to steer a national process of reform across multiple organizations and levels of government. Second, horizontal civil society collaboration was adopted while simultaneously allocating vertical coordinating authority to the executive unit. The research thus confirms that civil society organizations play especially prominent roles in open government and transparency policy areas (Fung, Citation2013; Zyl, Citation2014), but assigns a strong role to the co-option of existing networks and their balance with vertical authority. Nonprofits and government organizations tend to value multisector, horizontal structures more strongly than other sectors (Koliba et al., Citation2017). According to Ferlie, Fitzgerald, McGivern, Dopson, and Bennett (Citation2011, p. 321), long-term networks provide “a stable organizational core, ultimately rooted in the logic of professionalism, which protected organizational memory and learning.” In their organizational structures, government leaders thus seek help from stakeholder organizations that they trust and can rely on. In earlier works on horizontal policy networks, Dressel (Citation2012) observed that there remain unanswered questions about the sustainability of this relationship because of lack of developed institutional structures, conflicts of interest, and discrepancies in core beliefs among government and civil society actors. This article adopted Simon’s (Citation1973) tradeoffs between types of authority and expertise in order to focus on key parameters from organizational design theory. Indeed, the finding on authority and expertise is important: advanced open government designs rely on a primary role for civil society and, if managed correctly, such networks balanced with a vertical leadership function can contribute to long-term program success. However, there may be other types of design parameters in open government organizational design that determine effectiveness, such as Mintzberg’s (Citation1980) size, indoctrination, and training that have been given limited attention here and need to be researched further.

Third, decision makers integrated entrepreneurial technology organizations into various parts of the structure in order to gain their expertise and to turn public information and data into public value. This finding echoes the growing case being made in empirical research that technology savvy nongovernmental organizations play an integral role as a “policy broker” (Dressel, Citation2012). In open government, as in other areas of collaborative government, these structures need to be managed and the process facilitated with a clear set of standardized legal and normative processes that work for all the members (McGuire & Agranoff, Citation2011). Thus, the fourth major design decision concerned appointment of an information agency tasked with standardization of information and data coordination processes. This finding makes sense from the perspective of government decision makers because the merging into vertical systems of regional control is meant to address problems of increasing numbers of government tasks and an effort to be more efficient through standardization (Bikker & van der Linde, Citation2016; Jacot-Descombes & Niklaus, Citation2016). Much scholarship supports the concept that technology-oriented organizational design may have an internal drive toward vertical standardization processes due to the trend toward information control and economies of scale in government communications systems (Dunleavy, Margetts, Bastow, & Tinkler, Citation2006). This tension between vertical standardization and horizontal networks is an interesting subject that merits much more attention.

Conclusion

The findings of this research provide a starting point for a new theoretical perspective on open government and organizational design. The research is limited to the extent that it does not reveal the whole structure of the US and UK cases in terms of the larger setting within the governmental system nor does it aim to comprehensively describe the everyday workings of the organizational units. This would certainly be an interesting next step. Instead, the focus is on providing a framework for how decisions about organizational design relate to the core categories introduced by Mintzberg. In such a way, scholars and practitioners can use the framework to make more self-consciously design-oriented decisions about how to relate their environments, goals, and parameters to better performing open government designs.

Two case studies primarily involving interviews with expert decision makers provided an empirical basis for testing and developing the conceptual model, and a final model of high-performance decision making was established. Open government structures and processes in the UK and United States are notably vertical in leadership but are simultaneously dependent on existing networks of citizens and nonprofits such as user groups, technology organizations, and associations that can be used for mobilizing support for policy and developing policy solutions from conceptual development through implementation. There were also several key differences in the way that two countries design the structures and processes for delivering the goals of open government initiatives. These differences are largely predicated upon contingency factors such as existing institutional structures available to central executive agencies in the UK and the United States, and the context of political issues. Several contingency factors—legal frameworks, civic technology capacity, and responsive political mechanisms—were shared by both and supported their organizational design efforts.

There is a growing field of research on open government performance, and the role of economic, institutional, and legal factors (e.g., Grimmelikhuijsen & Feeney, Citation2017; McDermott, Citation2010; Safarov, Citation2018), but none have so far taken an organizational design approach. The present article addressed some of these broader environmental factors such as information rights, technological resources, and robust political institutions exist in high-performing open government countries, but it treats these factors in a different way by connecting them to organizational design concepts. The unique contribution of an organizational design perspective to performance is to provide a more internal, agency-based understanding of performance. Such an approach is not only useful for public administration theory, but also particularly helpful for addressing the gap between the ideals of open government and the realities.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this work for their insightful readings and commentaries. As this research largely grew out of my PhD research, I also owe a debt of gratitude to the dissertation committee that helped to shape my ideas: Professors Marc Holzer, Albert Meijer, Yahong Zhang, and most of all my supervisor Suzanne Piotrowski.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alex Ingrams

Alex Ingrams is an assistant professor in the Institute of Governance, Tilburg University. His research interests focus on government transparency, accountability, and open government. His latest focus has been on open government reforms in the United States and the United Kingdom as well as challenges to public governance reform raised by digital trends such as open data and big data.

References

- Allen, R., Hurcan, Y., & Queyranne, M. (2016). The evolving functions and organization of finance ministries. Public Budgeting & Finance, 36(4), 3–25. doi:10.1111/pbaf.12141

- Aucoin, P. (1990). Administrative reform in public management: Paradigms, principles, paradoxes and pendulums. Governance, 3(2), 115–137. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.1990.tb00111.x

- Bikker, J., & van der Linde, D. (2016). Scale economies in local public administration. Local Government Studies, 42(3), 441–463. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1146139

- Burton, R. M., & Obel, B. (2004). Strategic organizational diagnosis and design: The dynamics of fit (Vol. 4). London: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Clark, P. (1975). Organizational design a review of key problems. Administration & Society, 7(2), 213–256. doi:10.1177/009539977500700205

- Coglianese, C. (2009). The transparency president? The Obama administration and open government. Governance, 22(4), 529–544. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01451.x

- Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2012). Competing principles of agency organization–the reorganization of a reform. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 78(4), 579–596. doi:10.1177/0020852312455306

- Danziger, J. N., & Andersen, K. V. (2002). The impacts of information technology on public administration: An analysis of empirical research from the “golden age” of transformation. International Journal of Public Administration, 25(5), 591–627. doi:10.1081/PAD-120003292

- Dawes, S. S., Vidiasova, L., & Parkhimovich, O. (2016). Planning and designing open government data programs: An ecosystem approach. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 15–27. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2016.01.003

- Dressel, B. (2012). Targeting the public purse: Advocacy coalitions and public finance in the Philippines. Administration & Society, 44(6_suppl), 65S–84S. doi:10.1177/0095399712460055

- Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., Bastow, S., & Tinkler, J. (2006). New public management is dead—long live digital-era governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(3), 467–494. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui057

- Evans, A. M., & Campos, A. (2013). Open government initiatives: Challenges of citizen participation. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(1), 172–185. doi:10.1002/pam.21651

- Ferlie, E., Fitzgerald, L., McGivern, G., Dopson, S., & Bennett, C. (2011). Public policy networks and ‘wicked problems’: A nascent solution? Public Administration, 89(2), 307–324. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01896.x

- de Fine Licht, J. (2014). Policy area as a potential moderator of transparency effects: An experiment. Public Administration Review, 74(3), 361–371. doi:10.1111/puar.12194

- Fung, A. (2013). Infotopia: Unleashing the democratic power of transparency. Politics & Society, 41(2), 183–212. doi:10.1177/0032329213483107

- de Graaf, G., & Meijer, A. (2018). Social media and value conflicts: An explorative study of the Dutch police. Public Administration Review, 79(1), 82–92. doi:10.1111/puar.12914

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S. G., & Feeney, M. K. (2017). Developing and testing an integrative framework for open government adoption in local governments. Public Administration Review, 77(4), 579–590. doi:10.1111/puar.12689

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S. G., & Meijer, A. J. (2015). Does Twitter increase perceived police legitimacy? Public Administration Review, 75(4), 598–607. doi:10.1111/puar.12378

- Gulick, L. H. (1937). Notes on the Theory of Organization. In L. Gulick & L. Urwick (Eds.), Papers on the science of administration (pp. 3–45). New York, US: Institute of Public Administration.

- Heeks, R. B. (2001). Reinventing Government in the Information Age. London: Routledge.

- Howard, A. B., & McDermott, P. (2016). GOVERNMENT TRANSPARENCY. Reforms to improve US government accountability. Science (New York, N.Y.), 353(6294), 35–36. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2886

- Im, T. (2011). Information technology and organizational morphology: The case of the Korean central government. Public Administration Review, 71(3), 435–443.

- Ingrams, A. (2017a). Managing governance complexity and knowledge networks in transparency initiatives: The case of police open data. Local Government Studies, 43(3), 364–387. doi:10.1080/03003930.2017.1294070

- Ingrams, A. (2017b). The legal‐normative conditions of police transparency: A configurational approach to open data adoption using qualitative comparative analysis. Public Administration, 95(2), 527–545. doi:10.1111/padm.12319

- Jacot-Descombes, C., & Niklaus, J. (2016). Is centralisation the right way to go? The case of internal security policy reforms in Switzerland in the light of community policing. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82(2), 335–353. doi:10.1177/0020852315581806

- Koliba, C., Wiltshire, S., Scheinert, S., Turner, D., Zia, A., & Campbell, E. (2017). The critical role of information sharing to the value proposition of a food systems network. Public Management Review, 19(3), 284–304. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1209235

- Lane, J. E., & Wallis, J. (2009). Strategic management and public leadership. Public Management Review, 11(1), 101–120. doi:10.1080/14719030802494047

- McGuire, M., & Agranoff, R. (2011). The limitations of public management networks. Public Administration, 89(2), 265–284. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01917.x

- McDermott, P. (2010). Building open government. Government Information Quarterly, 27(4), 401–413.

- Meijer, A. J., Curtin, D., & Hillebrandt, M. (2012). Open government: Connecting vision and voice. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 78(1), 10–29. doi:10.1177/0020852311429533

- Mergel, I. (2013). A framework for interpreting social media interactions in the public sector. Government Information Quarterly, 30(4), 327–334. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2013.05.015

- Mergel, I., & Desouza, K. C. (2013). Implementing open innovation in the public sector: The case of Challenge.gov. Public Administration Review, 73(6), 882–890. doi:10.1111/puar.12141

- Metcalfe, L. (1993). Public management: from imitation to innovation. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 52(3), 292–304. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8500.1993.tb00281.x

- Mintzberg, H. (1980). Structure in 5’s: A synthesis of the research on organization design. Management Science, 26(3), 322–341. doi:10.1287/mnsc.26.3.322

- Mintzberg, H. (1990). The design school: Reconsidering the basic premises of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 11(3), 171–195. doi:10.1002/smj.4250110302

- Piña, G., & Avellaneda, C. (2018). Central government strategies to promote local governments’ transparency: Guidance or enforcement? Public Performance & Management Review, doi:10.1080/15309576.2018.1462215

- Piotrowski, S. J. (2017). The “Open Government Reform” movement: The case of the open government partnership and US transparency policies. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(2), 155–171. doi:10.1177/0275074016676575

- Piotrowski, S. J., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2007). Citizen attitudes toward transparency in local government. The American Review of Public Administration, 37(3), 306–323. doi:10.1177/0275074006296777

- Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363–377.

- Safarov, I. (2018). Institutional dimensions of open government data implementation: Evidence from the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK. Public Performance & Management Review. doi:10.1080/15309576.2018.1438296

- Schnell, S. (2017).Cheap talk or incredible commitment? (Mis) calculating transparency and anti‐corruption. Governance, 31(3), 415–430. doi:10.1111/gove.12298

- Simon, H. A. (1947). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organization (1st ed.). New York: Macmillan.

- Simon, H. A. (1973). Applying information technology to organization design. Public Administration Review, 33(3), 268–278. doi:10.2307/974804

- Sinclair, A. H., & Whitford, A. B. (2012). Separation and integration in public health: Evidence from organizational structure in the States. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(1), 55–77.

- Stiglitz, J. (2002). Transparency in government. The Right to Tell. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Suchman, L. A. (1987). Plans and situated actions: The problem of human-machine communication. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, J., & Burt, E. (2010). How do public bodies respond to freedom of information legislation? Administration, modernisation and democratisation. Policy & Politics, 38(1), 119–134. doi:10.1332/030557309X462538

- UK Cabinet Office (2016). Open Government Partnership National: Action Plan 2013-15: End-of-term self-assessment report. London, UK: The Cabinet Office. Last accessed on 07/14/2017 from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/open-government-partnership-national-action-plan-2013-15/open-government-partnership-national-action-plan-2013-15-end-of-term-self-assessment-report

- Yu, H., & Robinson, D. (2012). The new ambiguity of “open government”. UCLA Law Review Disclosure, 59, 178–208. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2012489

- Woodward, J. (1970). Industrial organization: Behaviour and control. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Zuurmond, A. (2005). Organisational transformation through the Internet. Journal of Public Policy, 25(1), 133–148. doi:10.1017/S0143814X05000231

- Zyl, A. (2014). How civil society organizations close the gap between transparency and accountability. Governance, 27(2), 347–356. doi:10.1111/gove.12073

Appendix

Detailed list of data sources used in the case study research.