Abstract

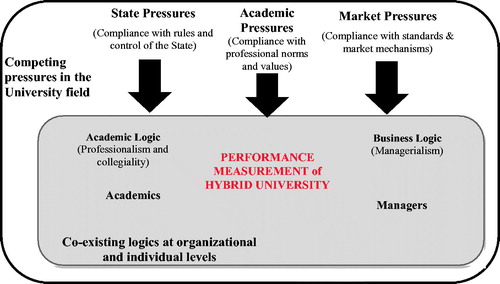

This study contributes to the current debate on competing institutional pressures and logics and performance measurement practices in hybrid universities and examines how shifts in logics have affected performance measurement practices at the organizational and individual levels. It draws upon the theoretical lenses of institutional theory and adopts a longitudinal case study methodology based on participant observations and retrospective interviews. The findings show that universities and academic workers are affected by external pressures related to higher education that include government regulations and control of the state (state pressure), the expectations of the professional norms and collegiality of the academic community (academic pressures), and the need to comply with international standards and market mechanisms (market pressures). Academic workers operate in an organizational context in which conflicting conditions from both academic and business logics co-exist. The results indicate that institutional pressures and logics related to the higher education field and organizational context shape the use of universities’ performance measurement practices and result in diverse solutions. While previous literature has focused mainly on competing logics and the tensions they may generate, this study shows that, in a university context, potentially conflicting logics may co-exist and create robust combinations.

Introduction

Neo-liberal views have increasingly influenced the perception of universities in recent years. The drive to increase the market orientation of operations in academia transformed the role of universities’ performance management (PM) practices, which not only played a developmental role, but also aimed to help academic workers improve their future performance (Jemielniak & Greenwood, Citation2015). Evaluations shifted towards a more quantitative and judgmental approach, in which evaluation is based largely on the quantitative evaluation of past performance (Kallio, Kallio, & Grossi, Citation2017; ter Bogt & Scapens, Citation2012). This change in performance evaluation is associated with the rise of new public management (NPM) and the growth of managerialism, which influenced the use of private sector mechanisms and tools within the public sector. These market pressures transformed many public organizations (including universities) into hybrid organizations that need to apply both commercial logic and historically dominant professional and public service logic (Battilana & Lee, Citation2014; Denis, Ferlie, & Van Gestel, Citation2015; Gebreiter & Hidayah, Citation2019). While a substantial body of literature on hybrid organizations from the general management and organizational perspectives exists, more specific research on performance measurement and management in hybrid organizations is still limited (Grossi, Reichard, Thomasson, & Vakkuri, Citation2017).

The present study explores the effects of shifting logics in the use of PM practices due to external pressures and internal challenges in a hybrid university characterized by competing and co-existing logics. This research includes a longitudinal case study of a private university that, apart from accreditations, rankings, and other market mechanisms (i.e., market pressures), depends mainly on student enrollment for financing. However, the university is also subject to governmental regulation and control. The university also applies for public funding for selected activities (research and some educational activities). These different financing streams largely determine the methods of management and reporting. At the organizational level, academic employees are interested in protecting their professional norms and values based on collegiality (i.e., academic logic). The institution also applies the managerial practices of the private sector (business logic). Conflicting external pressures (i.e., market and state) and organizational logics (i.e., business and academic) create tensions and conflicts among academics, who are engaged in an ongoing debate about the role and mission of the university. We will examine changes in the use of PM practices and their effects on individual academics in a hybrid university in which competing external pressures and organizational logics exist and interact, each dominating at a different time while co-existing and creating tensions. The co-existence, in this case, is quite stable rather than transitional, and more in the form of layering than blending, as the various elements of institutional logics are added on top of, and alongside, each other, with individual logics still discernible (Battilana & Lee, Citation2014; Polzer, Meyer, Höllerer, & Seiwald, Citation2016).

This study analyzes how such competing institutional pressures in the higher education field affect organizational logics in hybrid universities and the use of PM practices by individual actors (i.e., academics and managers) in hybrid universities. We conducted a qualitative, longitudinal case study of the process of change in the PM practices of a hybrid university that became increasingly research-oriented.

Prior research documented that universities’ PM practices developed due to reforms in the higher education sectors in the United Kingdom, Europe, North America, and Australia (e.g., Ahrens & Khalifa, Citation2015; Boitier & Rivière, Citation2013; Broadbent & Laughlin, Citation1998; Grossi, Kallio, Sargiacomo, & Skoog, Citation2019; Nagy & Robb, Citation2008; Roberts, Citation2004; ter Bogt & Scapens, Citation2012). Many scholars highlighted that due to changes higher education financing and growing international competition, universities had to become more entrepreneurial (Geuna & Rossi, Citation2011; Martin, Citation2012; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015), which resulted in their corporatization (Christopher, Citation2012; Hendriks & Sousa, Citation2013; Hull, Citation2006; Nagy & Robb, Citation2008; Parker, Citation2011; Pop-Vasileva, Baird, & Blair, Citation2011). University performance is now becoming more quantified (Kallio, Kallio, Tienari, & Hyvönen, Citation2016). The diffusion of “audit culture” and new bureaucratic mechanisms designed to render the universities more accountable, manageable, efficient, and visible through performance measures is referred to as “coercive commensurability” or “tyranny of numbers” (Brenneis, Shore, & Wright, Citation2005). These global trends based on NPM ideologies create several negative effects (resistance to change, internal conflicts, and dissatisfaction among employees) on academics and new internal power relations between academics and managers, which altered historically established roles and equilibria within traditional universities (Broucker, De Wit, & Verhoeven, Citation2018).

Despite the considerable amount of research on performance evaluation in traditional public universities, there is little research on how competing institutional pressures in higher education affects organizational logics and the use of PM practices by academics and managers in hybrid universities (ter Bogt & Scapens, Citation2012).

This paper is divided into five sections. The second section discusses the prior literature and the theoretical framework. The third section describes the research data, methods, and study context. The fourth section presents the results. The discussions and conclusions, as well as recommendations for future research, are presented in the last two sections.

Theoretical framework

Competing institutional pressures in the university field

In a globalized world experiencing strong effects of economic and financial crises, and which shares the need for reform, exogenous pressures motivated organizations to adopt a similar reform package through isomorphic behaviors; that is, each organization tends to resemble the others for the sake of increasing their legitimacy and conforming to socially accepted rules and practices (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). The idea of convergence comes from institutional theory, which emphasized the process of isomorphism, whereby organizations adopt similar procedures to gain legitimacy because of coercive, mimetic, and normative pressures (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). Hence, the agendas of many universities worldwide converged towards PM systems given the influence of competing pressures from the state, academic community, and market.

Traditionally, state pressure related to national priorities that reflect the needs of the public and the desires of higher education programs and services influenced universities, often expressed by national and international rules and monitored by national agencies for higher education. Thus, to obtain and maintain legitimacy in society, universities operated in research, teaching, and a third mission related to the need for strong national and local development and contacts with the local community and enterprises. Today, universities face increased governmental pressure to conduct better research and provide better education to receive the available, albeit reduced, government funding (Pop-Vasileva et al., Citation2011). Since the 1990s, several quality assessments occurred, with government funding tied to research and teaching output, forcing universities to become increasingly competitive to obtain these resources. State logic also influenced PM practices, with an increased focus on research performance, which is usually measured by the number of publications in academic journals. Furthermore, the international rankings of these journals are used as indicators of quality (ter Bogt & Scapens, Citation2012). There is increasing pressure on the research production side of academic work, exemplified by the phrase “publish or perish” (Kallio et al., Citation2016).

In addition, universities are exposed to market pressures derived from the need to sell program and services within and beyond national boundaries to ensure financial sustainability. Management cutback initiatives in funding compelled universities in several European countries to turn towards different sources of financing, resulting in the adoption of more market logics. Market pressures are the main drivers of this scenario, with a private tertiary sector regulated by private companies in terms of quality assurance and accreditation, and mostly funded through market mechanisms. Market logics stem from the need to maintain good positions in national and international rankings and to guarantee survivability. Market forces give rise to institutions that are specialized according to function (e.g., teaching, research), field (e.g., business, humanities), and audience (e.g., part-time students, distance education, adult learning, etc.), while business firms grant degrees to their employees for their corporate training. Market pressures also influenced the use of PM practices, with an increased focus on teaching performance related to the number of students, the degrees awarded, accreditations, and the quality of the education provided (Harker, Caemmerer, & Hynes, Citation2016). These PM changes led to higher student/staff ratios and greater teaching requirements and pressures (Parker, Citation2011).

Competing institutional logics within universities

The external pressures that emerge over time and are established at the field, environmental, and societal levels can impact an organization and alter the balance of its existing logics. At the organizational and individual levels, universities in Europe and elsewhere can be considered hybrid organizations subject to conflicting conditions from the perspective of both academic and business logic (Kallio et al., Citation2016; Kubra Canhilal, Lepori, & Seeber, Citation2016).

Academic logic is based on the idea that a university is a “community of scholars” whose main mission is to produce scholarly knowledge and maintain its academic reputation among peers (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008). Authority is based on professional seniority and collegial principles, whereas decisions are made by consensus, and academics are guaranteed full autonomy (Kubra Canhilal et al., Citation2016). Academic logic focuses on the specific nature of research activities, which cannot be controlled from the outside, and provides a rationale for the autonomy of research and a lack of central control. Academic logic aims to advance knowledge and is very different from and difficult to conciliate with business logics aimed at generating revenue and increasing commercial activities (Narayan, Northcott, & Parker, Citation2017). Universities in several countries are operating in environments in which governments introduced reforms based on business logics under the strong influence of neo-liberal ideologies that follow managerialism and an audit culture (Parker, Citation2011). Pollitt (Citation1990) described the new phenomenon of managerialism in public sector organizations, whose foundation is in the private sector, in which the importance of PM practices appears self-evident in several contexts. The key aspects of business logic maintained a focus on output, outcomes, and related value-for-money auditing; the outsourcing of former government activities to private organizations; more accountability and control mechanisms; performance based budgeting; a user-pay philosophy; and market-based competition. These strategic changes due to market and societal pressures related to internal organization, academic activities, hiring and firing, financing, and the internal allocation of resources represent a real threat to academic freedom (Evans & Nixon, Citation2015). Townley (Citation1997) examined the link between academics’ professional identities and institutional logics in the critical implementation of PM systems in universities. Business logic dictates the centralization of decisions and their implementation through command and rule systems, guiding employees in their activities (Kubra Canhilal et al., Citation2016). ter Bogt and Scapens (Citation2012) focused on the increased use of judgmental forms of more quantitative performance measures and the ambiguous effects they may have on individual workers, such as stress, uncertainty, and anxiety (Chandler, Barry, & Clark, Citation2002). For most academic workers, managerial logic led to increased occupational insecurity, work-related stress, and disillusionment with employer responsibility (Evans & Nixon, Citation2015). Kallio et al. (Citation2016) noted that business logics elevate metrics and indicators, and the system is likely to become self-referential and self-fulfilling. The diminishing sense of collegiality and academic logic that now evaluates individuals solely on the basis of measurable performance is evident (Evans & Nixon, Citation2015).

Hybrid universities and competing institutional pressures and logics

Universities are increasingly becoming hybrid organizations that combine the features of public sector organizations with those of private sector organizations (Billis, Citation2010; Grossi & Thomasson, Citation2015; Koppell, Citation2003). Hybrid organizations can be explained by the increasing prevalence of pluralistic and complex institutional environments and are exposed, over long periods of time, to multiple institutional logics (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008). Pache and Santos (Citation2013) stressed that it is not enough to focus mainly on the organizational-level perspective because it reveals little about the incorporation of logics within organizations; further study is needed on the elements of logics that individual actors enact as they attempt to deal with the competing pressures present in the institutional environment and the factors that drive their behavior. We address this gap by exploring how hybrid universities internally incorporate elements of competing logics influenced by external pressures related to their institutional fields.

Hybrid organizations are complex; often, understanding and measuring their organizational performance is difficult and affected by diverging interests and pressures (André, Citation2010; Billis, Citation2010; Grossi & Thomasson, Citation2015; Grossi et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Burke (Citation2005, p. 22) identified three conflicting pressures: (1) state pressure that reflects public needs for higher education program and services, often expressed by civic leaders outside the government; (2) academic pressure involving the issues and interests of the academic community, particularly of professors and administrators; and (3) market pressure related to the consumer needs and demands of students, parents, and businesses, as well as other clients. Universities are becoming hybrid organizations driven by competing logics, in the form of professional norms based on the collegiality of academics (i.e., academic logic), as well as managerial principles and tools (i.e., business logic) under the influence of competing pressures from the state, market, and academic community (Jongbloed, Citation2015; Mouwen, Citation2000).

The universities are thus hybrid organizations because they have multiple ambiguous goals. Their hybridity is also relevant in the area of university finance (Vakkuri, Citation2010). An emerging research issue is the impact of ambiguous goals on the performance of hybrid universities (Chun & Rainey, Citation2005; Johanson & Vakkuri, Citation2017). We should study hybrid universities as unique institutional spaces with distinct institutional logics. To understand these emerging logics, the links between the goals of hybrid universities and PM practices require further exploration.

In our study, we built a theoretical model (see ) that identifies institutional pressures present at the field level, and the organizational and individual responses to these pressures. In particular, we examine how the state, academic, and market pressures present in the higher education field (macro-level) influence the institutional logics (academic and business logics) at the organizational and individual levels (micro-level) and the use of PM practices by academics and managers.

In summary, universities are becoming hybrid organizations because at the organizational and individual levels, multiple, competing institutional logics (e.g., academic and business logics) co-exist as a combination of professional/academic and managerial/administrative values and PM practices (Pettersen, Citation2015), These logics operate in a community, environment, and field influenced by multiple and competing pressures from the state, academia, and the market (Battilana & Lee, Citation2014).

When different logics co-exist, organizations must prioritize (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, Citation2011). To understand how this prioritization occurs, we must establish an understanding of how multiple and competing logics affect hybrid organizations by eventually changing existing PM practices. An analysis of organizational and especially individual behavior is also desirable (Lounsbury, Citation2008). A focus on the key actors operating within the organization and leading the incorporation of different logics requires a study of the elements that act as enablers of or resistors to the PM changes universities introduce in response to external pressures from the state, market, and academic community.

In the next section, we will present the data collection and research methods, as well as the research context of Polish higher education and the hybrid university case.

Data collection, methods, and study context

A qualitative study is suitable for understanding the dynamics and processes of change from within the environment from which such changes emerge, as it allows researchers to engage with organizations and draw rationales from the field that could provide insight into how change unfolds over time and how accounting practices interact with the change process to enhance practice (Adams & Larrinaga-Gonzalez, Citation2007; Ball & Craig, Citation2010; Liguori & Steccolini, Citation2014). Such closeness to the people, events, and natural practice in the context being studied helps to produce a rich, in-depth portrayal of life that is representational and interpretive and persuades the reader that they are seeing a real picture of a studied phenomenon (Putnam, Bantz, Deetz, Mumby, & van Maanan, Citation1993, p. 224). In this qualitative case study, we conducted a longitudinal investigation (1992–2017) into the effects on and reactions to the changes in the institutional context in a private university in Poland and its workers. Our study is consistent with the call for new longitudinal research, as isomorphism and institutional logics are neither isolated nor static processes (Townley, Citation1997).

This study uses multiple data collection methods, such as archival analysis, retrospective interviews, and participant observation. The archival data sources included university regulations, rectors’ directives, minutes of senate and rectors’ meetings, accreditation reports, committee meeting minutes, and research reports prepared for university management and external bodies (e.g., accreditation agencies and state bodies) beginning from the establishment of the university in 1992 until 2017.

We made participant observations over the course of the last eight years; in one instance, one of the coauthors of this paper assisted the university in setting up performance systems. Observations during managerial meetings, faculty meetings, and the meetings of a special committee gave one of the team members the unique advantage of “comparing the rhetoric of reform with the reality of experience,” since “there has, so far, been very little systemic empirical research into practitioners’ experiences” (Norman & Gregory, Citation2003, p. 35).

To minimize researcher bias and improve the trustworthiness of the data, we triangulated data from archival sources (internal and external documents). We also applied a reflexive approach given our commitment to the university PM system (Beck, Citation1996). This approach has been important in building and maintaining the mindfulness of the object of this research, allowing us not only to ensure objectivity but also to invoke alternative voices or regain control over discursive practices (Cooper, Parkes, & Blewitt, Citation2014; Johnson & Duberley, Citation2003).

We conducted fifteen retrospective interviews in two rounds (in spring 2015 and spring 2017). We also conducted retrospective interviews as an appropriate technique to interview the participants and beneficiaries of a change process after its completion. Retrospective interviews most likely reflect the difficulties in capturing the dynamics of ongoing change that can span years (Roberts & Bradley, Citation2002). The interviews lasted from twenty minutes to one hour and fifty-two minutes. From the first round, the interview questions revolved around (1) changes in the performance evaluation systems and the evaluation of the current system caused by the shift in logic in the higher education field, and (2) the perceived consequences of the changes. The second round of interview questions referred to (1) the use of PM practices on the individual, departmental, and organizational levels, and (2) the perception of the changes in the use of these practices over the course of 24 years of university operation (see Supplementary Appendix 1). The retrospective interviews were semi-structured and conducted with the founders and management of the university, with senior and junior faculty, and with research and teaching faculty (see Supplementary Appendix 2). The initial intention of the research team was to interview the founders and the senior faculty who had been with the school since its establishment. However, because of the great diversity in faculty in terms of research engagement, we divided the interviewees into four groups: senior faculty fully engaged in research, junior faculty with at least five years of employment fully engaged in research, and senior and junior faculty who devoted more time to teaching than to research.

The authors recorded, transcribed, and coded the retrospective interviews. We conducted the coding processes and analysis using the MAXQDA software by one member of the research team. The other team members also conducted a manual analysis. We eliminated the differences during discussions between the researchers, and we reached a unified conclusion on any issue under analysis.

We applied open, axial, and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) to integrate the observations into codes, sub-categories, and categories. In the beginning, we adopted open coding by creating initial codes (derived from the textual field data and representing the main characteristics of the studied empirical material). Subsequently, we applied axial coding to identify relationships between the codes and to combine them into sub-categories such as “market logic,” “state logic,” and “academic logic.” We used selective coding in the final stage. To create the story and construct brother clusters that included all of the data, we developed the categories further. We selected core concepts, such as the categories of “logic in the field and society,” “logic in the organization,” and “the use of PM practices.” The data analysis helped to develop a narrative concerning how the shifts in logics in the higher education field affected the use of PM practices at the individual academic, department, and organization levels, and how different logics can change, dominate, and co-exist over time.

Higher education in Poland is one of the most dynamically developing areas of society in the country, but it is also highly regulated. Since 1990, Poland witnessed accelerated development in the higher education private sector (Dobija & Hałas-Dej, Citation2017). The research activities of nonpublic universities were always eligible for public funding. However, to receive such funds, nonpublic universities needed to undergo a voluntary evaluation of their research activities as public universities. Furthermore, there is a new mechanism to limit research funding for newly evaluated universities.

The case university was established in 1993 as one of the first nonpublic business universities in Poland. The university was integrated fully within the Polish system of higher education since its founding. According to Polish law, the founders of a private (nonpublic) university cannot be its owners or hold property rights over the school assets. The founders are not entitled to a share of the school’s financial surplus, which the university must reinvest in the school’s development by law. The founders provide the seed capital, prepare statutes for approval by the Ministry of Higher Education, and nominate the governing bodies of the new institution. Currently, the case university is a fully fledged, broad profile business school. It runs undergraduate and graduate program (approved by the state), as well as doctoral program in five disciplines. The university also has international accreditation and is included in international rankings of business schools.

In the next paragraph, we will present the longitudinal findings on the reasons and effects of shifting university logics in our case study.

Findings

The reasons for and effects of shifting university logics

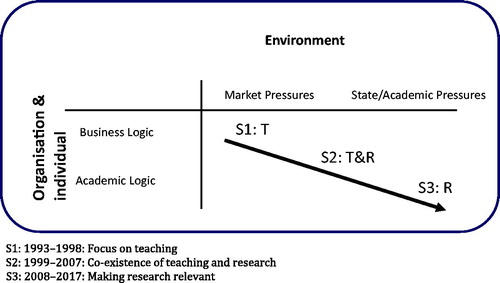

In this section, we analyze the pressures emanating from the field and society and the responses of the university as reflected by the applied organizational logics. We also discuss how external pressures and organizational logics affect the use of PM practices in the case study university. We identified three distinct periods in the development of our case university, in which state, market, and academic pressures competed and influenced the co-existence of business and market logics in terms of the PM practices it used. We summarize the findings in and .

Table 1. Institutional pressures in the university field and logics within the university.

Table 2. The evolution of the use of performance measurement.

Below, we analyze the three stages of our case study university’s development.

Stage one: focus on teaching (1993–1998)

Compared to many traditional universities, the case university had an “entrepreneurial” orientation (O’Shea, Allen, Chevalier, & Roche, Citation2005, 2007; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015) since its establishment. The first five years of the university’s operation were a period of faculty formation and organic growth in parallel to the formation and growth of the university itself. The university was fully immersed in its teaching activities, following the market needs and high demand for education. Market pressures had a significant impact on the university’s operations. Teaching was its core activity because tuition fees for higher education were the main source of the university’s funding. Furthermore, the university required permission from the Ministry of Higher Education to offer degree programs. At that time, the Ministry made such decisions based on an application showing that the school met the set criteria related to the number of teaching faculty in its programs and the requirements set in the so-called program minimum, a description of the minimum curriculum for a given degree. Not meeting those requirements would result in the withdrawal of the right to offer degree programs.

Subsequently, the university received permission to offer degree programs in accounting and finance, law, and sociology. The increased number of faculty members reflects this development. The university’s tuition had to cover not only the costs of education together with the increasing costs of faculty salaries, but also the development of infrastructure. Therefore, like many other private higher education institutions, the university struggled for financial survival. In addition, many public universities faced problems financing their operations, which resulted in schools adopting new hybrid forms of organization (Conrath-Hargreaves & Wüstemann, Citation2019). Regarding nonpublic universities, one respondent stated:

…as to non-public, private universities, (…) survival is for them the basic criterion. To survive, they had to earn money, so it is a financial criterion. (Interviewee P8)

To manage its financial solvency, the university had to provide a superior educational product in response to market needs, including various in-house company training sessions and programs for businesses. At the same time, business logic dominated the internal, organizational logic of the university. The quality of teaching and student satisfaction was the university’s priority, which its internal processes and procedures reflected. For instance, the school had no formalized procedure to manage and evaluate faculty at the time. Faculty evaluation was centralized at the top managerial level and conducted on an ad hoc basis. PM, especially information regarding the quality of teaching as provided by student evaluations, was used to allocate teaching responsibilities. As one of the department chairs described:

At the beginning, a formal system of evaluation of the departments did not exist. It had a subjective character. There was a form of individual conversation of the chair with the rector, organised on an annual basis. (…) We were discussing perspectives for the development of the school. (Interviewee P3)

Again, the focus was on the advancement of academic qualifications as well as the contributions that an individual faculty member could make to the expanding university. The “focus on teaching” stage involved the development of scattered research projects among faculty members. However, research was not a priority at the time. One of the interviewees described the situation as follows:

Twenty years back there was no system of research financing. There was no research really, from the point of view of the institution. There were, however, individual employees, but only some of them conducted research. (Interviewee P4)

At some point, the university management realized that two new developments were essential to ensure the long-term growth of the institution. The first was investment in the academic development of the university and permanent faculty hired on a full-time basis with exclusive contracts. The second was the development of more formalized research activities. The school designed a new performance measurement system in 1998 involving a research component. Additionally, the university also expected permanent faculty to participate in the university’s organizational activities. At this stage, the primary focus was on advancing the academic qualifications of the junior faculty, as well as the contributions of individual faculty members to the expanding school.

Stage two: co-existence of teaching and research (1999–2007)

Responding to market needs was still a priority for the university. However, to secure the school’s future, a high position in the local market was not considered sufficient; therefore, the university’s top management pushed for international accreditation as a signal of its superior quality in the international market (Dobija, Górska, & Pikos, Citation2018).

Internally, business logic still dominated the university’s decisions. The quality of teaching and student satisfaction were still considered important elements in securing funding. At the same time, the first attempt to receive research funding from the Ministry of Higher Education was successfully undertaken, causing a shift in performance expectations that originated from external research evaluations (i.e., state pressure). Additionally, accreditation agencies also expected the continued development of research activities (i.e., market pressure). This was when academic logic started to emerge at the university. These external pressures motivated faculty to participate in research projects, and the school developed appropriate management tools, such as the annual evaluation of departments and the periodic evaluations of individual faculty members. As one of the senior faculty members explained:

(…) the new performance evaluation system was introduced only for external reasons. Internally, the system was needed, but there was never pressure to introduce the system internally. (…) The system was enforced by external forces related to the accreditation process. (Interviewee P4)

The university developed a new performance system, which assumed evaluation at the departmental level and evaluation of individual faculty members. A chair produced a performance report, the results of which he or she then discussed with the top management of the university. However, it seems that the entire PM process, both at the departmental and individual levels, played a more ceremonial and symbolic role, already forgotten by the faculty (Dobija, Górska, Grossi, & Strzelczyk, Citation2019).

As one of the faculty members stated, “There was such an episode. But it was never accepted” (Interviewee P10). The respondents described the departmental evaluation not as a formal evaluation by a committee but rather as an informal annual meeting of each chair with the rector, at which point the evaluation and development plans for each department were discussed.

A motivational system supplemented the PM system. The school offered young faculty members exclusive contracts Ph.D. and research grants funded by the university that aimed to encourage them to focus on research activities. However, since the grant process lacked any monitoring, it was treated more like an additional benefit rather than a way to speed up the progress of completing a Ph.D. or habilitation. As with the department evaluations, in the case of individual PM, the divergence between the regulation and real practice is evident when contrasting the archival documents with the interview findings:

Later, with the development of the school, formal processes were established more for visibility reasons than out of real need. “Since there is a requirement of conducting faculty evaluation, let’s do it.” (…) A formal system was not really needed, as for many years the primary goal for the school, even today, has been teaching. (Interviewee P3)

Stage three: making research relevant (2008–2017)

The PM system introduced in stage two did not prove sufficient to provide the expected outcomes for the academic development of the university. At the same time, there was increasing market pressure from outside the university related to the development of internationalization and research activities. Accreditation agencies expected alignment between all of the university activities with its vision and mission. This led faculty members and the academic community to expect a higher research orientation, with research output taking the form of international journal publications. Moreover, participation in various academic degree rankings increased the academic pressure for more research activities, since research was one of the evaluation criteria. Changes in the higher education sector, understood as state and academic pressures, also pushed the university toward a research orientation and an improved academic standing. First, a new reform in higher education in Poland introduced a radical change in the research funding streams. The level of funding depended on the outcome of an evaluation of parameters that signaled the importance of journal publications in particular. The government created a separate stream of research funding by establishing The National Science Center and The National Center for Research and Development, which award research grants to individual researchers in a system based purely on competition.

All of the developments described above pushed the university to strengthen its research activities and develop a more academic culture by adding a new layer to the existing business logic. The process of change to fully incorporate academic logic was not an easy one. The school first used its old tools to improve research performance. It used the same performance evaluation design, and emphasized meeting the performance targets described in the contract. Unfortunately, many of the school’s employees did not share that vision and were instead more concerned with maintaining the status quo in the name of academic freedom, understood as the idea that “faculty members were free to do what they wanted to do in the time it took.” It was also clear that, to introduce a real change in performance, a stronger consensus was needed.

The school introduced its new PM system in 2013 after two years of discussion and negotiations with key stakeholders with the hope of re-orienting the teaching culture of the organization to one that was more academic. The system intended to ensure better management of faculty, set clear goals for different groups of faculty members with similar contributions, and establish a system of rewards and consequences. As one faculty member states:

The reasons for the introduction [of the PM system] were simple: We wanted a tool for building expectations and consequences but also rewards. I mean positive and negative consequences, with certain expected behavior for the employees. (Interviewee P10)

At the university level, the school used the PM practices not only for external accountability purposes, but also for internal decision-making related to HR policy and incentive allocation. The university also allocated internal research funding based on the prior performance of an individual applicant. At the departmental level, the school would still base its teaching allocation on information about teaching quality and involvement in various activities. However, we observe a radical change in the use of PM practices at the individual level. Individuals used the information from the PM system to plan and prioritize different academic activities to reach the maximum output (a mix of teaching, organizational assignments, and research) and to create a research plan for the purposes of social comparison. Generally, individuals used PM practices to plan their academic careers. As one of the respondents noted, “… what, it seems to me, is the main change, is that we had to start planning our careers” (Interviewee P12).

Discussion

While the extant literature focused on competing logics and their possible conflict when expectations/pressures are divergent (Greenwood et al., Citation2011; Scott, Citation2014; Van Gestel & Hillebrand, Citation2011), this study shows that potentially conflicting logics may harmoniously co-exist in a university (Reay & Hinings, Citation2005). The analysis highlights the elements that render such an equilibrium possible in the university context, characterized by a process of change in PM systems due to external and internal forces and logics.

Since the 1990s, reforms in the university sector were often introduced by imitating private-sector ideologies and tools (such as PM systems) from Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Canada, and the United States (Boitier & Rivière, Citation2013; Coy Tower & Dixon, Citation1994; Guthrie & Neumann, Citation2007; Modell, Citation2003; Pettersen, Citation2015; ter Bogt & Scapens, Citation2012; Yamamoto, Citation2004; Vakkuri & Meklin, Citation2003). We focused on the experience of a central Eastern European country (Poland) that, during the last few decades, introduced several reforms.

In our study, we used a private university in Poland as an example of a hybrid university (Jongbloed, Citation2015; Pache & Santos, Citation2013) that operates in an environment with multiple and competing pressures from the state, academic community, and market, which affected its organizational and individual logics (academic and business) in different ways since its establishment.

The results of previous studies (Parker, Citation2011; Wedlin, Citation2008) reveal that the strength of external market pressures affects the internal adoption of managerial practices and logics within public universities that were historically permeated by academic logic. Our case presents different results because the university started as a business school specializing in teaching specific programs for national companies and government agencies, and only after several years of operations did it introduce academic logic under the growing state pressure through regulations. Over time, the environment changed; therefore, changes in the organizational logics as well as in the PM system occurred. presents the links between external pressures and organizational logics and PM practices.

Figure 2. The impact of competing institutional pressures, and logics on PM practices in the hybrid university.

In the first period (S1: 1993–1998), the university was mainly market-oriented (but faced a local market, including mainly the Warsaw area), and the organization and individual scholars concentrated mainly on teaching duties and other business activities. In this period, the dominant logic within the university was a business logic strongly influenced by the market pressures present in the Polish university field.

In the second period (S2: 1999–2007), the university began competing in the Polish and international university markets, where research was an important element of the academic environment. In this period, the Polish government also introduced university reforms with the aim of increasing academic quality among Polish universities. The changing pressures related to the context and the field of higher education strongly affected the dominating logic of the university, creating a specific mix of business and academic logics. In this period, the two potentially conflicting logics clearly co-existed in the university (Reay & Hinings, Citation2005), but not without friction. The academic logic required a new set of skills and resources. The main tensions came from faculty and administrators who preferred the status quo and were resistant to change. Although the business logic was written in the DNA of the university, the business school needed to add a new perspective to its core activities. The university started to introduce policies and initiatives focusing on research (e.g., the position of vice-rector for research, an office for research administration, policy and strategy, and a new regulation for awards for academic publications). The first attempts to obtain state funding for research also drew attention to the performance measures of the national research assessment. State and academic pressures strongly concentrated on the use of research performance measures that the school needed to add to its internal PM practices to motivate academic staff to produce the desired research output, which would permit the increase of the university’s share of government funds to finance its growing research activities.

The last period (S3: 2008–2017) brought about increased excellence in internal research due to the academic pressure related to highlighting academic autonomy in terms of choosing a research area, building research networking, and the very nature of research. High-quality teaching and market orientation remained the sine qua non of a private (nonpublic) university. However, business logic is strongly connected to the quality of teaching, and was dominated by academic logic, making the latter more visible to faculty; the PM system reflected this change. Simultaneously, the university developed its “entrepreneurial” activities (O’Shea et al., Citation2005, Citation2007; Martin, Citation2012; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015), which took a more complex form in cooperation with business. The research was commercialized and disseminated in a business environment. The effects of the dominance of research logic created resistance to change, internal conflicts, and dissatisfaction among employees who contributed mainly to the university’s teaching and commercial activities. Our results are consistent with previous studies in different European contexts (the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Finland) that highlighted the negative effects (e.g., stress, interpersonal conflict) of PM systems on individual researchers and departments (ter Bogt & Scapens, Citation2012; Kallio & Kallio, Citation2014).

The private nature of the university, with its strong historical focus on commercial activities and international accreditations (i.e., market pressure) and the emerging pressures due to governmental regulations and control (i.e., state pressure), explain the organizational and individual tensions between business and academic logic (Greenwood et al., Citation2011; Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, Citation2012), especially regarding commercialization and internationalization, and the need to compromise (Oliver, Citation1991) when prioritizing decisions and activities. On the one hand, commercialization, internationalization, and a strong focus on teaching and training activities may improve a university’s financial performance. On the other hand, the public nature of educational services and the increased state and academic pressures for higher quality research may conflict with these non-core activities because of the risks and business-like nature of such initiatives.

All things considered, this longitudinal case study shows that hybrid universities may adjust to the prevailing logics at the organizational level by reducing engagement in commercial and teaching activities when national and environmental pressures work against them. The state regulatory bodies and regulations (i.e., state pressure) together with the pressures from the academic community in concert with different endogenous pressures related to market mechanisms (e.g., accreditations, international rankings, etc.; i.e., market pressures), can influence internal organizational logics, PM systems, and scholars’ professional choices. During this period, there was a clear shift at the organizational level as the dominant logic moved from business to academic logic. Our results also show different responses (i.e., compliance or resistance) to competing institutional pressures (Willmott, Citation1995; Townley, Citation1997).

Conclusions

Our study’s findings are consistent with those of previous research on PM practices in higher education (Dobija et. al., 2018, 2019; Geuna & Rossi, Citation2011; Harker et al., Citation2016; Kallio et al., Citation2016; Citation2017; Parker, Citation2011; Pettersen, Citation2015; Pop-Vasileva et al., Citation2011; ter Bogt & Scapens, Citation2012). Prior studies noted the changes in PM practices in universities conditioned by state and market pressures and the rise of managerialism and the corporatization of PM practices at universities. These practices contrasted with the ideas of a university community and collegial culture, which enjoys professional autonomy, collegiality, and freedom in setting research priorities. This study builds on the previously identified determinants of change in PM practices and adds to the literature on universities by advancing our understanding of how competing pressures in the university field over a period of more than twenty years influenced the shifts in organizational logics and PM practices used by individual workers (i.e., academics and managers).

The study also offers a unique research setting. We focus not on a traditional public university in a developed country that was already widely researched by previous scholars, but a hybrid organization (i.e., a private university) in Eastern Europe, which over time experienced the effects of different pressures coming from the academic community and both the private and public sectors. This study documents the process of adjustment to the prevailing logic at the organizational level and relevant changes in the use of PM practices, as well as the process of adjustment and responses to the changes at the individual level of academic workers. We provide clear evidence that multiple and diverging forms of logic shape the PM practices of hybrid universities. We also contribute to the debate on performance measurement of hybrid organizations (Grossi et al., Citation2017, Citation2019), as such universities operate in knowledge intensive fields (research, teaching, and third missions) and present several elements of hybridity and ambiguity in term of goals, financing, and their performance measurement systems.

More broadly, our study contributes to existing neo-institutional theory, which according to Greenwood et al. (Citation2011), concentrated mainly on two competing logics instead of focusing on the multitude of external pressures and organizational logics that organizations face. While the existing literature focused on competing logics and the possible tensions they can generate when expectations/pressures are divergent, the present study also shows that diverging logics can co-exist in a university context, as Reay and Hinings (Citation2005) suggested. Our findings show that the university added the emerging academic (i.e., research) logic to the existing (i.e., teaching) business logic, and now both logics co-exist among different academics but are still quite separate and not fully blended.

This study therefore has important managerial implications for the higher education sector, as it shows the different stages of development of a hybrid university, an institution which originated as a private teaching school applying a purely business logic and evolving to address the changes in pressures emanating from the outside. The market for private higher education institutions is growing worldwide. For instance, in an article published by Forbes on 25 March 2018, Russell Flannery (Citation2018) provided statistics about the private education sector in China. The revenue generated from the private education sector will rise from 19.7 billion USD in 2012 to 51.7 billion USD in 2020. Research on the private education sector is very limited (Dobija et al., Citation2018). This study thus offers some insight to owners and managers of private schools operating in different contexts on how to shape their university’s performance systems to meet the diverging demands of various stakeholders. In particular, PM in the university context should consider not only efficiency and quantitative measures, but also qualitative measures related to reputation, trust, and innovation.

The findings reported in this paper have several limitations. First, the results stem from a single case study; therefore, further research is required to explore whether these findings are applicable to other hybrid universities and can be extended to other types of hybrid organizations. Second, it is possible that the participation of one of the authors in the implementation of the PM system at the case study university could have affected the validity and reliability of the study to some extent. However, the other two authors were both recently hired at the school and were not permanent members of faculty during the period of analysis, and analyzed and interpreted the collected data in an independent manner.

We believe that future research should address the strategic responses hybrid universities adopt to improve their organizational and individual performances in a context of multiple competing pressures from the field of higher education and logics within the organization. Competing institutional pressures and logics may also be aligned with risk analyses. Additionally, further studies could also advance our understanding of other factors influencing these internal changes for academic workers. Such an exploration may provide universities and their managers with a basis for developing strategies to successfully manage tensions between different academics arising from a multiplicity of logics over time (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010; Kubra Canhilal et al., Citation2016; Jalali Aliabadi, Mashayekhi, & Gal, Citation2019). Researchers could apply the institutional work perspective to investigate the internal dynamics and interactive nature of actors’ relations to institutional changes (Lawrence, Suddaby, & Leca, Citation2011). Moreover, future studies could include the role of key actors (academics, managers, controllers, auditors, etc.) who enable changes (i.e., the institutional entrepreneurs) by considering their interests, power, and search for legitimacy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dr. Daniela Argento (Kristianstad University, Sweden), Prof. Christoph Reichard (Potsdam University, Germany), Prof. Olof Olson (Gothenburg University, Sweden) and Dr. Tobias Polzer (Sussex University, UK) for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this paper. The authors are grateful for the comments received by the participants of the 40th Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association, Valencia (Spain), 10-12 May 2017, Research Seminars at Monash University (Australia), 6 February 2018, and at Gothenburg University on 16 May 2018. The authors also recognize the support received from Prof. Alfred Ho (Kansas University, UK) and the three anonymous reviewers in the process of publishing this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Giuseppe Grossi

Giuseppe Grossi is Professor in Business administration (with a focus on Public Management and Accounting) at the, Kristianstad University (Sweden), Research Professor in Accounting at Nord University (Norway) and Kozminski University (Poland). Grossi’s research focuses on governance, performance management and budgeting of public and hybrid organizations. He’s currently guest editor of several public management and accounting journals, and editor in chief of Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting and Financial Management (Emerald).

Dorota Dobija

Dorota Dobija is Professor in Management and Accounting at Kozminski University (Poland). Her primary research interests are focus on performance management in public and non-profit sector and topics related to the links of accounting and corporate governance.

Wojciech Strzelczyk

Wojciech Strzelczyk holds a PhD and is Assistant Professor at Kozminski University (Poland). His main research areas are performance measurement in public sector and not for profit organizations, public and local government finance and socio-economic development.

References

- Adams, C. A., & Larrinaga-Gonzalez, C. (2007). Engaging with organizations in pursuit of improved sustainability accounting and performance. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 333–355. doi:10.1108/09513570710748535

- Ahrens, T., & Khalifa, R. (2015). The impact of regulation on management control. Compliance as a strategic response to institutional logics of university accreditation. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 12(2), 106–126. doi:10.1108/QRAM-04-2015-0041

- André, R. (2010). Assessing the accountability of government-sponsored enterprises and quangos. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(2), 271–289. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0509-y

- Ball, A., & Craig, R. (2010). Using neo-institutionalism to advance social and environmental accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(4), 283–293. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2009.11.006

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.57318391

- Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing: Insights from the study of social enterprises. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397–441. doi:10.1080/19416520.2014.893615

- Beck, U. (1996). World risk society as cosmopolitan society? Ecological questions in a framework of manufactured uncertainties. Theory Culture and Society, 13(4), 1–32. doi:10.1177/0263276496013004001

- Billis, D. (2010). Towards a theory of hybrid organizations. In D. Billis (Ed.), Hybrid organizations and the third sector: Challenges for practice, theory and policy (pp. 46–69). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Boitier, M., & Rivière, A. (2013). Freedom and responsibility for French universities: From global steering to local management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(4), 616–649. doi:10.1108/09513571311327480

- Brenneis, D., Shore, C., & Wright, S. (2005). Getting the measure of academic: Universities and the politics of accountability. Anthropology in Action, 12(1), 1–10. doi:10.3167/096720105780644362

- Broadbent, J., & Laughlin, R. (1998). Resisting the new public management: Absorption and absorbing groups in schools and GP practices in the UK. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 11(4), 403–435. doi:10.1108/09513579810231439

- Broucker, B., De Wit, K., & Verhoeven, J. C. (2018). Higher education for public value: Taking the debate beyond New Public Management. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(2), 227–240. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1370441

- Burke, J. C. (2005). Achieving accountability in higher education: Balancing public, academic, and market demands. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Chandler, J., Barry, J., & Clark, H. (2002). Stressing academe: The wear and tear of the new public management. Human Relations, 55(9), 1051–1069. doi:10.1177/0018726702055009019

- Conrath-Hargreaves, A., & Wüstemann, S. (2019). Multiple institutional logics and their impact on accounting in higher education: The case of a German foundation university. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(3), 782–810. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-08-2017-3095

- Christopher, J. (2012). Tension between the corporate and collegial cultures of Australian public universities: The current status. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23(7–8), 556–571. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2012.06.001

- Chun, Y. H., & Rainey, H. G. (2005). Goal ambiguity and organizational performance in U.S. Federal Agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(4), 529–557. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui030

- Cooper, S., Parkes, C., & Blewitt, J. (2014). Can accreditation help a leopard change its spots? Social accountability and stakeholder engagement in business schools. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(2), 234–258. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-07-2012-01062

- Coy, D., Tower, G., & Dixon, K. (1994). Public sector reform in New Zealand: The progress of tertiary educational, 1990–92. Financial Accountability and Management, 10(3), 253–261. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0408.1994.tb00011.x

- Denis, J. L., Ferlie, E., & Van Gestel, N. (2015). Understanding hybridity in public organizations. Public Administration, 93(2), 273–289. doi:10.1111/padm.12175

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. doi:10.2307/2095101

- Dobija, D., & Hałas-Dej, S. (2017). Higher education in management: The case of Poland. In S. Dameron & T. Durand (Eds.), The future of management education. Challenges facing business schools around the world (Vol. 1, pp. 277–295), London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dobija, D., Górska, A. M., Grossi, G., & Strzelczyk, W. (2019). Rational and symbolic uses of performance measurement: Experiences from Polish universities. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(3), 750–781. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-08-2017-3106

- Dobija, D., Górska, A., & Pikos, A. (2018). The impact of accreditation agencies and other powerful stakeholders on the performance measurement in Polish universities. Baltic Journal of Management, 14(1), 84–102. doi:10.1108/BJM-01-2018-0018

- Evans, L., & Nixon, J. (Eds.). (2015). Academic identities in higher education: The changing European landscape. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Flannery, R. (2018, March 25). Why the private education market in China will outperform in the next decade. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com

- Gebreiter, F., & Hidayah, N. N. (2019). Individual responses to competing accountability pressures in hybrid organizations: The case of an English business school. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(3), 727–749. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-08-2017-3098

- Geuna, A., & Rossi, F. (2011). Changes to university IPR regulations in Europe and the impact on academic patenting. Research Policy, 40(8), 1068–1076. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.008

- Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371. doi:10.1080/19416520.2011.590299

- Grossi, G., & Thomasson, A. (2015). Bridging the accountability gap in hybrid organizations: The case of Copenhagen Malmö Port. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(3), 604–620. doi:10.1177/0020852314548151

- Grossi, G., Reichard, C., Thomasson, A., & Vakkuri, J. (2017). Performance measurement of hybrid organizations: Emerging issues and future research perspectives. Public Money and Management, 3(6), 379–385.

- Grossi, G., Kallio, K. M., Sargiacomo, M., & Skoog, M. (2019). Accounting, performance management systems, and accountability changes in knowledge-intensive public organizations: A literature review and research agenda. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, Advance online publication. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-02-2019-3869

- Guthrie, J., & Neumann, R. (2007). Economic and non-financial performance indicators in universities: The establishment of a performance-driven system for Australian higher education. Public Management Review, 9(2), 231–252. doi:10.1080/14719030701340390

- Harker, M. J., Caemmerer, B., & Hynes, N. (2016). Management education by the French Grandes Ecoles de Commerce: Past, present, and an uncertain future. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 15(3), 549–568. doi:10.5465/amle.2014.0146

- Hendriks, P. H. J., & Sousa, C. A. A. (2013). Practices of management knowing in university research management. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26(3), 611–628. doi:10.1108/09534811311328605

- Hull, R. (2006). Workload allocation models and “collegiality” in academic departments. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 19(1), 38–53. doi:10.1108/09534810610643677

- Jalali Aliabadi, F., Mashayekhi, B., & Gal, G. (2019). Budget preparers’ perceptions and performance-based budgeting implementation. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 31(1), 137–156. doi:10.1108/JPBAFM-04-2018-0037

- Jemielniak, D., & Greenwood, D. J. (2015). Wake up or perish: Neo-liberalism, the social sciences, and salvaging the public university. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 15(1), 72–82. doi:10.1177/1532708613516430

- Johanson, J. E., & Vakkuri, J. (2017). Governing hybrid organizations: Exploring diversity of institutional life. London: Routledge.

- Johnson, P., & Duberley, J. (2003). Reflexivity in management research. Journal of Management Studies, 40(5), 1279–1303. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00380

- Jongbloed, B. (2015). Universities as hybrid organizations: Trends, drivers, and challenges for the European University. International Studies of Management & Organization, 45(3), 207–225. doi:10.1080/00208825.2015.1006027

- Kallio, K. M., & Kallio, T. J. (2014). Management-by-results and performance measurement in universities: Implications for work motivation. Studies in Higher Education, 39(4), 574–589. doi:10.1080/03075079.2012.709497

- Kallio, K. M., Kallio, T. J., Tienari, J., & Hyvönen, T. (2016). Ethos at stake: Performance management and academic work in universities. Human Relations, 69(3), 685–709. doi:10.1177/0018726715596802

- Kallio, K. M., Kallio, T. J., & Grossi, G. (2017). Performance measurement in universities: Ambiguities in the use of quality vs. quantity in indicators. Public Money & Management, 37(4), 293–299. doi:10.1080/09540962.2017.1295735

- Koppell, J. G. S. (2003). The politics of quasi-government: Hybrid organizations and the dynamics of bureaucratic control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kubra Canhilal, S., Lepori, B., & Seeber, M. (2016). Decision-making power and institutional logic in higher education institutions: A comparative analysis of European Universities. In R. Pinheiro, L. Geschwind, F.O. Ramirez & K. VrangbÆk (Eds.), Research in the Sociology of Organizations: Vol. 45. Towards a comparative institutionalism: Forms, dynamics and logics across the organizational fields of health care and higher education (pp. 169–194). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Lawrence, T., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2011). Institutional work: Refocusing institutional studies of organization. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(1), 52–58. doi:10.1177/1056492610387222

- Liguori, M., & Steccolini, I. (2014). Accounting, innovation and public-sector change: Translating reforms into change? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25(4–5), 319–323. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2013.05.001

- Lounsbury, M. (2008). Institutional rationality and practice variation: New directions in the institutional analysis of practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4–5), 349–361. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2007.04.001

- Martin, B. R. (2012). Are universities and university research under threat? Towards an evolutionary model of university speciation. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36(3), 543–565. doi:10.1093/cje/bes006

- Modell, S. (2003). Goal versus institutions: The development of performance measurement in the Swedish university sector. Management Accounting Research, 14(4), 333–359. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2003.09.002

- Mouwen, K. (2000). Strategy, structure and culture of the hybrid university: Towards the university of the 21st Century. Tertiary Education and Management, 6(1), 47–56. doi:10.1080/13583883.2000.9967010

- Nagy, J., & Robb, A. (2008). Can universities be good corporate citizens? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19(8), 1414–1430.

- Narayan, A. K., Northcott, D., & Parker, L. (2017). Managing the accountability-autonomy of universities. Financial Accountability & Management, 33(4), 335–355. doi:10.1111/faam.12127

- Norman, R., & Gregory, R. (2003). Paradoxes and pendulum swings: Performance management in New Zealand's public sector. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 62(4), 35–49. doi:10.1111/j.2003.00347.x

- Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. doi:10.5465/amr.1991.4279002

- O’Shea, R. P., Allen, T. J., Chevalier, A., & Roche, F. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation, technology transfer and spinoff performance of U.S. universities. Research Policy, 34(7), 994–1009. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2005.05.011

- O’Shea, R. P., Allen, T. J., Morse, K. P., O’Gorman, C., & Roche, F. (2007). Delineating the anatomy of an entrepreneurial university: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology experience. R&D Management, 37(1), 1–16.

- Pache, A. C., & Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logic. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 972–1001. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0405

- Parker, L. (2011). University corporatisation: Driving redefinition. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 22(4), 434–450. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2010.11.002

- Pettersen, I. J. (2015). From metrics to knowledge? Quality assessment in higher education. Financial Accountability & Management, 31(1), 23–40. doi:10.1111/faam.12048

- Pollitt, C. (1990). Managerialism and public services: The Anglo-American experience. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Polzer, T., Meyer, R. E., Höllerer, M. A., & Seiwald, J. (2016). Institutional hybridity in public sector reform: Replacement, blending, or layering of administrative paradigms. In J. Gehman, M. Lounsbury & R. Greenwood (Eds.), Research in the Sociology of Organizations: Vol. 48B: How Institutions Matter! (pp. 69–99). Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

- Pop-Vasileva, A., Baird, K., & Blair, B. (2011). University corporatisation: The effect on academic work-related attitudes. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 24(4), 402–439.

- Putnam, L. L., Bantz, C., Deetz, S., Mumby, D., & van Maanan, J. (1993). Ethnography versus critical theory: Debating organizational research. Journal of Management Inquiry, 2(3), 221–235. doi:10.1177/105649269323002

- Reay, T., & Hinings, C. R. (2005). The recomposition of an organizational field: Health care in Alberta. Organization Studies, 26(3), 351–383. doi:10.1177/0170840605050872

- Roberts, N. C., & Bradley, R. T. (2002). Research methodology for New Public Management. International Public Management Journal, 5(1), 17–51.

- Roberts, R. W. (2004). Managerialism in US universities: Implications for the academic accounting profession. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(4–5), 461–467. doi:10.1016/S1045-2354(03)00039-X

- Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2015). Academic entrepreneurship: Time for a rethink? British Journal of Management, 26(4), 582–595. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12116

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Procedures and techniques for developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ter Bogt, H. J., & Scapens, R. W. (2012). Performance management in universities: Effects of the transition to more quantitative measurement systems. European Accounting Review, 21(3), 451–497.

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (pp. 99–129). London: Sage.

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure and process. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

- Townley, B. (1997). The institutional logic of performance appraisal. Organization Studies, 18(2), 261–285. doi:10.1177/017084069701800204

- Vakkuri, J., & Meklin, P. (2003). The impact of culture on the use of performance measurement information in the university setting. Management Decision, 41(8), 751–759. doi:10.1108/00251740310496260

- Vakkuri, J. (2010). Struggling with ambiguity: Public managers as users of NPM oriented management instruments. Public Administration, 88(4), 999–1024. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01856.x

- Van Gestel, N., & Hillebrand, B. (2011). Explaining stability and change: The rise and fall of logics in pluralistic fields. Organization Studies, 32(2), 231–251. doi:10.1177/0170840610397475

- Wedlin, L. (2008). University marketization: The process and its limits. In L. Engwall & D. Weaire (Eds.), The University in the market (pp. 143–153), London: Portland Press.

- Willmott, H. (1995). Managing the academics: Commodification and control in the development of university education in the UK. Human Relations, 48(9), 993–357. doi:10.1177/001872679504800902

- Yamamoto, K. (2004). Corporatization of national universities in Japan: Revolution for governance or rhetoric for downsizing? Financial Accountability and Management, 20(2), 153–181. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0408.2004.00191.x