Abstract

The quality of judgment by regulatory professionals is key to good regulatory governance yet also a potential problem. Psychological studies have shown that individuals easily make judgment errors and that feeling accountable—expecting to have to explain and justify oneself—improves one’s judgments. This paper explores to what extent felt accountability improves regulatory judgment processes in more realistic settings than the traditional laboratory study. It does so in an experimental design inspired by a classic study. Samples of professional regulators and students were given a judgment task with conflicting and incomplete information under varying conditions of accountability and in a context of ambiguity. Results confirm that accountability improves professional regulators’ judgment processes in terms of decision time, accurate recall of information and absence of recency bias. However, professional regulators were significantly more accurate in their judgments than students. Our results suggest that it is important to devise appropriate forms of operational accountability for regulatory professionals that stimulate their cognitive efforts and guard against biases.

Introduction

The past decades have witnessed a large growth in attention for behavioral studies of human judgment, personified by the Nobel prizes for Herbert Simon, Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler. This literature generally suggests that the individuals’ capacity for rational, unbiased and comprehensive judgment is quite limited. The mind is, to paraphrase Kahneman (Citation2011), “a lazy machine … jumping to conclusions.” Individuals are prone to make various decision errors, to an important degree as a result of low effort. Kahneman (Citation2011, p. 35) speaks about

a general ‘law of least effort’ [which] applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action (…) Laziness is built deep into our nature.

Tetlock (Citation1992) spoke in comparably strong words about humans as “cognitive mizers.” This skeptical perspective on the individuals’ ability to make high quality judgments has in recent years had a huge impact on public policies (Feitsma, Citation2019; Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008).

Behavioral research suggests that felt accountability—making judgments or decisions whilst anticipating (possible) future accountability (Hall et al., Citation2017; Han & Robertson, Citation2021; Overman et al., 2021)—serves as a powerful antidote against low quality judgments. There are hundreds of experimental studies showing the effects of (felt) accountability on human judgment (see for reviews Hall et al., Citation2017; Lerner & Tetlock, Citation1999). In these studies, higher decision time is the most frequently found effect of accountability (Aleksovska et al., Citation2019) which, in turn, is strongly related to cognitive effort (Cooper-Martin, Citation1994; Rausch & Brauneis, Citation2015) and is a prerequisite for less biased, more highly informed and more accurate, judgment processes.

The human judgment problem is crucial from a public administration perspective as individual professional judgment has become an ever more important aspect of governmental work. In contemporary regulatory states (Majone, Citation1994), an increasing part of the government’s work rests on the exercise of judgment by thousands of individual regulatory professionals. They form “concentric circles” (Hood et al., Citation1998) involving auditors, inspectors, market regulators, judges, grievance handlers and many others. Good individual judgment is key to important developments in regulatory governance, such as performance-based regulation (Coglianese et al., Citation2003), principle-based accounting (Cohen, et al., Citation2013), and risk-based regulation (Black & Baldwin, Citation2010). In these cases, regulators and auditors need to do more than “just” assess whether some organization or product complies with clearly operationalized and finite standards. Rather, they have to make complex judgments in less or more ambiguous contexts where they are guided by open norms.

The behavioral science research would generally put question marks behind the capability of individuals such as regulatory professionals to consistently pass high-quality judgments. Research in regulation adds more specific concerns to this and shows how regulatory judgment in practice can be divergent and at times problematic.Footnote1 Beyond organizational, political and legal concerns (Koop & Hanretty, Citation2018), scholars have pointed at several psychological factors with potential detrimental effects on the quality of judgment. Regulatory judgment has been found to be influenced by such psychological factors as emotions (Maroney, Citation2011), (lack of) empathy (Lee, Citation2013), and ego-depletion (Hurley, Citation2015). Regulators as “Humans” (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008) may be biased in their judgments (Dudley & Xie, Citation2020; Helm et al., Citation2016) and affected by for instance anecdotal evidence (Wainberg et al., Citation2013) or partition dependence bias (Wolfe et al., Citation2017).

The above suggests that the general human judgment problem may also affect regulatory professionals specifically. And while felt accountability may serve as an antidote against some judgment errors, this is difficult to operationalize in this regulatory governance, as independence is generally seen as a key value (Koop & Hanretty, Citation2018; Majone, Citation1994). Although the accountability of regulatory agencies has often been identified as a salient issue (Black, Citation2008; Maggetti, Citation2010; Mills & Koliba, Citation2015; Scott, Citation2000), its empirical impact has not had much academic attention in research of regulatory governance (but see Koop & Hanretty, Citation2018), notably not on the individual level (but see Cushing & Ahlawat, Citation1996; Helm et al., Citation2016; Thomann & Sager, Citation2017).

The study of human judgment and accountability has been mainly developed outside of public administration and regulatory governance. The psychological literature on accountability and judgment has been developed almost exclusively in the lab (83%), mostly with student samples (73%) and with nonrealistic assignments (Aleksovska et al., Citation2019). Although there are some indications from public administration studies of biased regulatory judgment in the real world, as noted above, and there is currently a strong development in behavioral public administration (cf. Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Citation2017), the ecological validity (Brewer & Crano, Citation2000) and scope of both the human judgment problem in regulatory governance and the effect of accountability on regulatory judgment have not been assessed so far (cf. Dudley & Xie, Citation2019). Both the prevalence of lower quality judgments as well as the effectiveness of accountability as an antidote have not been established for regulatory professionals. It is reasonable to expect different outcomes when research is moving from the lab toward the field; yet it is uncertain what those differences would be.

Against this background, the aim of this paper is to contribute to our understanding of the quality of regulatory judgment processes and accountability as a potential antecedent. The study makes two, related, contributions. First, it is one of the first to analyze the effects of felt accountability on the quality of judgment processes of regulatory professionals in a more realistic (yet still artificial) setting. This is relevant as the overwhelming majority of experimental studies on accountability and judgment have been conducted with students (cf. Aleksovska et al., Citation2019) and professional regulators are likely to differ from students. Secondly, the study compares the judgments of a sample of general students to those of regulatory professionals. This contributes to our understanding of the scope of judgment problems in regulation, which has been highlighted as salient in literatures on regulation (cf. Dudley & Xie, Citation2019, Citation2020; Koop & Hanretty, Citation2018) but has not been investigated thoroughly on the individual level.

The study is inspired by a classic experiment (Tetlock, Citation1983) which has been translated to a more realistic (yet still artificial) context of regulatory governance and is conducted with samples of professional regulators as well as students. The study draws on the key assumption that accountability can lead to “more complex and vigilant information processing” (Tetlock, Citation1983, p. 86) which, in turn, accounts for higher regulatory judgment.

Two research questions are addressed: (1) How do professional regulators compare to students in a more realistic task of regulatory judgment?, and (2) Does felt accountability enhance the quality of regulatory judgment processes?

The paper first discusses the relevance of accountability for regulatory governance and conceptualizes how accountability is used in psychological studies. The paper then discusses our procedural notion of judgment quality, resting on decision effort, accuracy and complexity. After the methods section, the analyses offer both confirmation and consolation. The results confirm that regulatory professionals may also make easily avoidable decision errors, even though the exercise of judgment is key to their work, and that felt accountability improves the quality of judgment processes. This is reason for concern from the perspective of regulatory governance. However, the comparison between the experimental groups also offers consolation, as the trained professionals made arguably stronger judgments than the students. In the concluding discussion, the limitations of this study, prospects for future research and policy implications for regulatory governance are discussed.

Accountability, regulation and judgment

Accountability and regulatory governance

The growth and global diffusion of the regulatory state in the past decades have been mapped out extensively (cf. Jordana et al., Citation2011). Regulatory agencies need independence or autonomy to operate effectively which stands at odds with classical conceptions of democratic accountability. As a result, the accountability of regulatory agencies has received considerable scholarly attention (cf. Biela & Papadopoulos, Citation2014; Black, Citation2008; Maggetti, Citation2010; May, Citation2007; Mills & Koliba, Citation2015; Scott, Citation2000).

Although the notion of independent regulatory agencies suggests otherwise, studies show that those agencies are de jure and de facto encapsulated in more or less complex accountability regimes (Biela & Papadopoulos, Citation2014; Fernández-i-Marín et al., Citation2015). Autonomy and accountability seem to be at odds but can in fact co-exist, although they do apparently not co-evolve (Maggetti et al., Citation2013). Regulatory agencies may be pressured by political and societal forces and thus need to be well-connected to political powers and other salient constituencies, both for support as well as for legitimacy (Black, Citation2008; Fernández-i-Marín et al., Citation2015). In effect, regulatory agencies tend to operate in webs of accountability in which they are accountable to various political, legal, societal and professional account-holders (Thomann & Sager, Citation2017).

Accountability comes in many guises, operates in different forms and has accordingly been identified as a chameleonesque (Sinclair, Citation1995) or magic concept (Pollitt & Hupe, Citation2011). In most studies on regulation, the focus lies on the meso-level of the organization and the ways in which the organization is or can be held accountable. This is for instance evidenced in the study by Koop and Hanretty (Citation2018) who, as in this article, analyzed the effects of accountability on the quality of regulatory decision-making. They made an inventory of accountability requirements on the meso-level of the organization by focusing on statutory designs. On the basis of available documents, they measured accountability in terms of items, such as the requirement to submit an annual financial report or (multi)annual activity plans and then related this to some quality criteria.

Meso-level accountability should affect the micro-level of the individual regulators’ judgments (Thomann & Sager, Citation2017; Overman et al., Citation2021). There is however quite some distance between the aggregated accountability in an annual report and the accountability for single case decisions. Biela and Papadopoulos (Citation2014) refer to the latter with “operational accountability.” This refers to whether and how individual regulators explain their (role in) the judgment of a specific case to some salient “forum,” in line with Bovens’ (Citation2007) much used definition.

The micro-level of accountability is the subject of psychological studies. Here, accountability has been more or less consistently used to denote situations where agents anticipate that their decisions or actions may be assessed by a salient audience (or accountability forum) in the future (Hall et al., Citation2017; Lerner & Tetlock, Citation1999). These studies showcase the micro-level mechanisms that may explain the effects of accountability on individuals, as was also noted by Koop and Hanretty (Citation2018, p. 45). Accountability then denotes the individual’s “felt” accountability (Hall et al., Citation2017): does (s)he expect to have to explain her judgment in the future?

In experimental studies in psychology (Hall et al., Citation2017; Lerner & Tetlock, Citation1999) and public administration (Overman et al., Citation2021), individually felt accountability was found to have an impact on decisions and judgments. Accountability works by making people alert; signaling the salience of some norms or values that have to be taken into account. This not only makes the decision-maker more alert to the problem at hand but also to demands, interests, concerns and viewpoints of strategically relevant stakeholders (Black, Citation2008). The immediate effect of accountability on the individual’s judgment process is increased cognitive effort (Lerner & Tetlock, Citation1999). The related concept of decision time has been found in a very large number of experimental studies (Aleksovska, Citation2019) and is a prerequisite for “good” regulatory judgment process, as is explained below.

Quality of regulatory judgment processes

Regulators monitor and assess the behaviors of others (often economic agents) and apply sanctions to enforce compliance with norms (Koop & Lodge, Citation2017). They have to collect, assess and weigh information, apply generic norms and standards appropriately to specific situations, and weigh competing norms and concerns in the inevitable circumstance of ambivalence and ambiguity. At the core of regulatory governance, thus, lies the behavioral problem of good judgment by professional regulators amidst ambiguity.

In the literature on regulation, a majority of studies focus on the “problem” of regulatory discretion and how the individual regulators’ use of discretion can be curbed in order to ascertain control and compliance (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012). This presupposes that regulatory problems can be solved by consistent and controlled application of general standards to situations. However, regulatory practice is often marked by “pragmatic improvisation” by individual regulators executing “agency.” Regulatory practice involves the use of discretion by individual regulators, as Braithwaite (Citation2011, p. 518) reflects regarding “responsive regulation.” In responsive regulation, this mostly refers to the use of instruments and sanctions, where regulators in practice have some discretion. The judgment issue which is central to our study focuses on the interpretation of a case. This is of particular relevance to cases with loosely specified performance standards which give regulators, but also targets of regulation, more discretion in how they interpret the standard and work toward compliance with the general idea, rather than specified requirements (Aleksovska, Citation2021; Coglianese et al., Citation2003). Loosely specified standards are often seen as desirable although they introduce uncertainties and ambiguities for regulators and industries. In contexts with non-finite regulations, regulators face a judgment problem: there is (some) ambiguity that cannot be solved by top-down rule application but requires regulators to weigh existing evidence and interpret incomplete rules in order to “conserve institutional norms” (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012, p. S22).

In broader studies of judgment, the decision-making situation is characterized by ambiguity or uncertainty (Pitz & Sachs, Citation1984). Information may be ambiguous or incomplete; norms may be unknown, uncertain or conflicting; the causal chain relating outcomes to decisions may be opaque. In such cases it is not possible from the outset or with hindsight to judge what the right judgment was or will be. In such cases, scholars revert to “good process” criteria to assess the quality of judgment processes.

Common process norms to evaluate decision-making under uncertainty are rationality, consistency (Pitz & Sachs, Citation1984), and cognitive/integrative complexity (Lerner & Tetlock, Citation1999; Suedfeld & Tetlock, Citation2014). Rationality suggests that someone’s judgment is the logical outcome of a proper weighting and understanding of the evidence. This implies the absence of bias. Consistency implies that individuals and individual cases are consistently judged similarly across time and by different regulatory professionals. And cognitive complexity implies that the regulator digests all of the available information and comprehensively weighs the different pieces of information. In studies of regulatory judgment and regulatory decision-making, these and comparable norms are generally identified (see Supplementary Appendix 4 for an overview of extant studies).

The relevance of these norms for individual judgment processes follows from the predictably irrational (Ariely, Citation2008) nature of human decision-making and judgment (see also Kahneman, Citation2011). Psychological studies suggest that humans are bounded in their capacity to make rational, unbiased, consistent and high-effort judgments. In the past decade, there has been an enormous growth in interest in the behavioral problems of public policy making and administration, departing from this more realistic, if not more pessimistic, view of humans as flawed decision-makers (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Citation2017; Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008). These insights are of acute relevance to professional regulators. Dudley and Xie (Citation2019, Citation2020) have recently provided compelling overviews of the various judgment biases that might be relevant to regulators, mostly based on system I responses in which unconscious, automatic and often emotionally laden impulses drive our judgments. They for instance describe that regulatory judgment may be susceptible to affect heuristics, in which someone’s personal affects drive judgments. Regulatory judgment may also be affected by different types of aversion—ambiguity aversion, risk aversion or extremeness aversion—all of which standing in the way of a balanced and rational judgment. And they also point at the problem of overconfidence and over-optimism. Particularly more experienced regulators may prematurely conclude that they fully understand a case. These types of biases may lead to sub-optimal assessments of, and unrealistic solutions for, real problems.

Dudley and Xie’s (Citation2019, Citation2020) agenda-setting papers tie in with studies on the judgments and decisions of judges and auditors. In those studies, scholars find that auditors and judges may indeed not always manage to be “objective” (Svanberg & Öhman, Citation2016) or “impartial” (Lee, Citation2013). The evidence suggests that they can be unduly affected by irrelevant factors such as the tone or presentation of evidence or the role of attorneys (Black et al., Citation2016; Collins et al., Citation2015; Szmer & Ginn, Citation2014). The particular problem is that of proper weighting of arguments, data, evidence and advice which may go against their ability to come to a rational judgment (Bednarik & Schultze, Citation2015; Cutler & Kovera, Citation2011; Kim, Citation2017; Kovera & McAuliff, Citation2000; Samaha, Citation2018; Tadei et al., Citation2014; Wainberg et al., Citation2013).

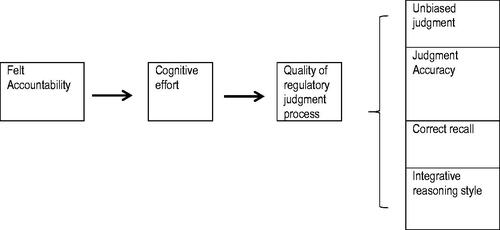

On the basis of the above, and building on the measures used in Tetlock’s (Citation1983) original experiment, this study adopts four measures for the quality of regulatory judgment processes. These are all preceded, as shows, by judgment effort as an antecedent or procedural prerequisite. A basic assumption is that the regulator at least puts in a serious cognitive effort and tries to digest all available information (cf. Aleksovska et al., Citation2019; Ossege, Citation2012). Higher cognitive effort is then expected to be associated with several elements of good regulatory judgment processes.

The first element is judgment accuracy. Regulators have to assess and weigh facts and evidence which requires accuracy. Being accurate is important to counter problems with consistency (Ashton, Citation2000) and reliability (Tuijn et al., Citation2014). Accuracy in collecting and recalling information lowers the risk of over-aggressive or over-moderate judgments (Cianci et al., Citation2017; Cohen et al., Citation2013).

The second element is correct recall. Regulators use their memories in the judgment of cases and they need to be able to correctly recall several distinct salient facts from a case. This was also part of the original study by Tetlock (Citation1983).

The third element is an integrative reasoning style. It is important for regulators not only to disentangle and correctly remember different facts and values in a case, these also need to be integrated and related to each other. Weighting and relating evidence properly is crucial for professional regulators and others passing judgment under the condition of ambiguity (Bednarik & Schultze, Citation2015; Cutler & Kovera, Citation2011; Kim, Citation2017; Kovera & McAuliff, 2000; Samaha, Citation2018; Tadei et al., Citation2014, 2016; Wainberg et al., Citation2013).

Our last indicator of good regulatory judgment processes is unbiased judgment. Inattentive decision-makers may easily fall for relatively simple decision biases, for instance related to the order of information (Wolfe et al., Citation2017) or a confirmation bias (Dudley & Xie, Citation2020; Helm et al., Citation2016). In the short term, there can be a recency bias, where the most recent information clouds one’s judgment (Cushing & Ahlawat, Citation1996). On the somewhat longer term, there may be a primacy bias, where the first received information dominates (Tetlock, Citation1983). Both biases result from order-effects of information, which influences the inattentive decision-maker who may disregard or forget some of the information.

Extant studies have shown that accountability may improve judgment accuracy (Harari & Rudolph, Citation2017; Mero & Motowidlo, Citation1995), guards against many biases (although it may also increase some other biases) (Aleksovska et al., 2019; Tetlock, Citation1983) and boost cognitive complexity (Lerner & Tetlock, Citation1999; Schillemans, Citation2016). These effects in turn presuppose increased cognitive effort. All in all, we reason that the presence of accountability stimulates regulators to put more cognitive effort into a judgment task, which may then have salutatory effects. below summarizes our conceptual model.

Increasing experimental realism

The conceptual model in is consistent with Tetlock’s (Citation1983) original study, although accuracy and integrative reasoning were added to this, and dovetails with many recent findings on the effects of felt accountability (Hall et al., Citation2017; Overman et al., Citation2021). This paper tests the ecological validity of the relations in this model and compares the effects of accountability on regulatory judgment processes by professionals to students. The study is still artificial in several ways yet is more realistic than the classic laboratory study (cf. Supplementary Appendix 3).

While student samples are valid for experimental studies as they help to uncover fundamental human traits, we must be hesitant to generalize findings from the lab to comparable situations in the field. In this particular case, it is relevant to note that students are generally more compliant than other subjects (McDermott, Citation2002, p. 37). One can imagine that the effects of accountability may be overestimated when tested on relatively compliant subjects. Further and in line with this, effect sizes of accountability are consistently larger for student samples than for professional participants (Aleksovska et al., Citation2019). In addition, professionals are repeat players with training and skills. Experience has often been found to improve the quality of judgment (Martinov-Bennie & Plugrath, Citation2009). Professional regulators can thus be expected to outperform students in more realistic regulatory judgment cases (Lindholm, Citation2008; Moulin et al., Citation2018). Finally, through professional training and socialization, professionals become part of “epistemic communities” that see the world in specific ways. Together these points suggest that student judgments may be substantively unrepresentative of judgments by regulatory professionals. One of the two aims of the study is therefore to compare student and professional participants in the same experimental scenario.

Study design

The study was conducted in three distinct yet related experiments. As we will explain below, we originally aimed to conduct two identical experiments with different samples (students and professional regulators). This only served to answer one of the two research questions. A third experiment was therefore added, with a strengthened scenario and a more powerful manipulation of accountability, to answer the second research question.

The study was modeled on a classic experiment on the effects of accountability on the quality of judgment processes by Tetlock (Citation1983). The original scenario was used for heuristic purposes. The study aims to generalize and extend insights from generic laboratory studies to more realistic contexts of public sector regulation. The study is still marked by a level of abstractness an artificiality—participants obviously know they are not really judging a case—but the selection (and comparison) of participants, the setting, the task and the scenario increase experimental realism (see also Supplementary Appendix 3). The first experiment is a laboratory experiment while the latter two can be seen as framed field experiments, with a field context in task, information set and subjects (cf. Bouwman & Grimmelikhuijsen, Citation2016).

The scenario

In the original experiment, students as subjects acted as a jury judging “mister Grey,” who was the suspect of murder. This scenario was translated to a public sector context. In the new scenario (see Supplementary appendix 1 for the scenario and Supplementary appendix 3 for a comparison of the designs of the studies), the murder case was transformed into a bankruptcy case in which a semipublic organization went bankrupt and the CEO was suspected of mismanagement. Participants were told they were asked as experienced regulators (which they in fact were) to assess 18 pieces of information—half of them suggesting the CEO might indeed be guilty while the other half suggested he might not be—about the case and to give a preliminary assessment of the likelihood of mismanagement as an advice to the authorities. The information was made available in different orders (mixed, all exculpatory evidence last, or all inculpatory evidence last). They performed this judgment task in the presence or absence of accountability: the expectation that they might have to explain their judgment to a salient forum in the future. Participants had limited time to read all available information. They could not take notes or go back to the information. They thus had to pay attention and collect and remember the available information, which requires cognitive effort. They then had to indicate the likelihood of mismanagement on a slider (0–100) and justify their advice using all relevant information they could remember from the case.

The scenario was based on a string of comparable cases in the Netherlands in which semipublic organizations in social housing, education and health care ran into financial problems. The scenario and the accountability conditions were verified with advice from five experts in public sector regulation. The case was however set in a different administrative system—in Nordrhein Westphalen—in order to create some distance to specificities of Dutch administrative law and financial regulations.

As participants had to draw conclusions from evidence and provide a numerical evaluation of the case (see also Harari & Rudolph, Citation2017) this is a judgment case. In this task, participants’ short-term memories play an important role which is expected to be activated by felt accountability. In the real world of public sector regulation, obviously records and notes disburden people’s memories. However, even when regulators work with files and records, their memorization skills and efforts still play a role. Memories affect how records are used, what conclusions are drawn and how new insights are integrated. Particularly during impression formation, memories affect how information is digested and one’s initial impression has an effect on the final judgment over time. The accurate recall of information is thus important to judgment (Libby & Trotman, Citation1993; Spellman, Citation2010).

Participants

The study was conducted with three samples of participants (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for details and descriptives).

The first sample consisted of students enrolled in an undergraduate public policy-course. The second sample consisted of regulatory professionals enrolled in professional workshops or training programs. The first two samples shed light on the relative quality of judgment of both groups. However, the accountability manipulation was insufficiently powerful. For this reason a third experiment was conducted with a new sample of professional participants and a stronger accountability manipulation. This third sample consisted of judges and legal professionals.

Sample sizes are modest (N = 86; 77; 85). As the experiment was modeled on Tetlock’s (Citation1983) study, we aimed to have at least the same sample size he had (N = 72) and did not conduct a power analysis.

Participants were informed in advance that they participated in research by making a case on how information was used in judgments, as Tetlock (Citation1983) had also done. The words “accountability,” “quality” and “experiment” were carefully avoided prior to the debriefing. Participation was voluntary. Participants had the opportunity to withdraw after the debriefing. In total, approximately 10 participants from all samples withdrew.

All three experiments were integrated in existing classes for professional training or university education and were followed by a workshop or lecture explaining the full experimental design and facilitating a debriefing and joint reflections on how regulatory professionals can counter bias and boost the quality of judgment. Access was dependent on our professional networks in the Netherlands enabling access to high-level professional or student training programs. From a research perspective, this procedure had the advantage of access to professionals in settings where they had the time to participate seriously. The debriefings and workshops were highly informative and provided valuable feedback on the study design and the judgment challenge of professional regulators. The group of professional participants was intentionally diverse as we wanted to understand how regulators in general compare to a more traditional sample of student-participants.

Measurements and manipulations

Accountability

In line with the original experiment, some randomly selected participants in the first two studies were informed that their judgments would be assessed and they were, thus, judging under the condition of accountability (“pre-exposure accountability”).Footnote2 This was part of the set of information provided. Debriefings soon suggested that participants sometimes missed or disregarded this part of the information and, thus, missed the manipulation. This was later confirmed in the analysis: accountability was not related to the dependent variables. In the third sample, we therefore strengthened the manipulation of accountability and simplified it to one condition of anticipated face-to-face accountability to peers and professors in the workshop. This manipulation was successful, based on the debriefing.

Order of information

There were nine pieces of exculpatory evidence and nine pieces of inculpatory evidence (see Supplementary Appendix 1). The evidence was presented in different orders: all exculpatory evidence last, all inculpatory evidence last, or mixed. Participants were randomly assigned to these conditions. In the third experiment, the mixed-order group was dropped to increase statistical power.

Cognitive effort was approximated by measuring decision time, as recorded by the survey software, in line with many previous studies on judgment in psychology (Aleksovska et al., Citation2019). Decision time is a relevant but not a perfect measure for effort as there are other explanations of variation in decision time between individuals. It has nevertheless been used frequently in experimental studies and as it is related to cognitive effort (Cooper-Martin, Citation1994; Rausch & Brauneis, Citation2015).

Unbiased judgment was measured by comparing the mean judgments of the different groups in order of information. An unbiased judgment means that there is no information order effect and that participants weigh the evidence irrespective of the order of presentation. A biased judgment means that the information order significantly affects group means leading to either a primacy effect (Tetlock, Citation1983) or a recency effect (Cushing & Ahlawat, Citation1996). Tetlock (Citation1983) originally found the former, by letting participants think about the information for two minutes before they had to recall it. This waiting time was impossible to incur in our experimental settings and participants went straight into judging. Earlier research suggests that on a short notice a recency effect is likely as the last read information “sticks” (Cushing & Ahlawat, Citation1996). Both effects are to a large degree contingent on the same mechanism: low-effort, inattentive decision-making.

Judgment Accuracy was measured by independent manual coding of responses by two researchers. We counted the number of items properly recalled but also calculated the numbers of errors and mistakes made, including the use of arguments not actually given in the experimental materials. Intercoder reliability was high with Cohen’s kappa 0.82.

Correct recall was measured by calculating the number of correctly recalled items from the case, in line with Tetlock (Citation1983).

Integrative reasoning was measured by coding the reasoning style of participants. As it turned out, quite some participants simply related their arguments in a string of more or less unrelated bullets (mostly actually using bullets). Others wrote more narrative elucidations of their judgments, in which they provided some reasoning and weighing of the arguments in the case and brought inculpatory and exculpatory evidence together and explained how they weighed them.

The data set further includes a limited number of background variables (Table A-2 in Supplementary appendix 1). For all groups, we know (1) gender and (2) sub-group (that is, samples were collected on several dates) of subjects. For the two professional samples we know (3) years of professional experience in their current role, (4) whether or not they have experience with these types of cases, and (5) professional background in terms of education (sample 2) or legal area (sample 3).

Most of these background variables were not related to the dependent variables in this study. There were two exceptions. First of all, sample 2 consists of subjects whose responses were collected during five different professional workshops and this intra-group distinction had some impact on judgment effort. The participants in the first of these workshops spent significantly more time on the judgment task while the participants in the fourth workshop spent significantly less time on the task. Secondly, in the third sample there were, given the small group sizes, some unexpected effects of legal area on the numerical judgments made. Those working in criminal law were significantly harsher in their judgment of the CEO than others, while those working in commercial law were significantly more lenient. Given the small sample, we must be careful to interpret this.

provides an overview of the concepts, the samples, the measures, and the analyses. Supplementary Appendix 3 provides details of analyses and descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Overview of the experiments.

Results

Regulatory judgment processes

As stipulated in , we expected that the quality of judgment processes first of all depends on the regulators’ cognitive effort which will make her less susceptible to bias, more accurate, able to remember more facts correctly and more likely to adopt an integrative reasoning style. These various indicators are not necessarily related although, normatively, one would hope. It is relevant from a normative position as none of these variables on their own would easily be acceptable as criterion for “good” regulatory judgment processes. In conjunction, however, they provide a much more convincing case. A regulator putting in more time and effort, using more information, explicitly weighing evidence, steering clear of bias and avoiding factual errors, could convincingly claim to use her “discretion” (Braithwaite, Citation2011) or “agency” (Maynard‐Moody & Musheno, Citation2012) wisely.

Our analyses show that most of these variablesFootnote3 are indeed related, although not all of them and not similarly across the samples. As table A-5 (Supplementary Appendix 2) shows for the first two samples, the time spent on the task was significantly related to the number of correctly recalled items and an integrative reasoning style. Accuracy, the number of mistakes made, was not related to the other variables of interest. The pattern was somewhat different in the third sample (see table A-6, Supplementary Appendix 2), where time and differentiation are related and, separately, correct recall and integrative reasoning style are also related. All in all this suggests that there is variation in regulatory judgment processes and that there are significant relations between the different dependent variables, although the relations are imperfect.

Recency bias

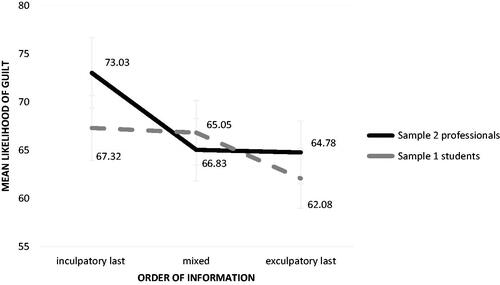

We calculated the mean assessments of guilt of mismanagement by the CEO in the scenario for the three groups with different orders of information (inculpatory last, mixed, exculpatory last) in sample 1 and 2. It turned out that in the joint sample of professionals and students, but also within the separate samples, the order of information had an effect on judgment. The last received information was found to stick. Participants reading the nine pieces of inculpatory evidence last were on average significantly harsher in their judgments of the likelihood of guilt of mismanagement than the other participants. The pattern was very clear even though obtained in 11 separate class-room settings with inevitable noise. The order of information was significantly correlated to the assessment of guilt in the joint sample as well as in the separate samples. A one-way ANOVA confirmed the relationship (F = 6,446, p = 0.013). below visualizes the differences between the groups. As the visualization shows, the order effect is even somewhat more pronounced for professional subjects than for students. Our experiment thus dovetails with others finding orders effect on judgment (Tetlock, Citation1983; Wolfe et al., Citation2017).

Figure 2. The recency bias. * This figure shows the mean judgments of likelihood of guilt of the three experimental groups regarding information provision in samples 1 and 2. The figure shows that the groups of participants receiving al inculpatory evidence last believed the CEO in the scenario is significantly more likely to be guilty of mismanagement.

Professionals are more accurate than students

The finding above may raise some concern about the quality of regulatory judgment processes. Even though the manipulation was transparent and every participant could easily gauge the specific order in which information was provided, it still had effects on the judgments passed by trained professionals. Obviously, this was not a real case so we cannot claim to have measured how regulators operate in the field. However, the debriefings acknowledged that it was fairly realistic and participants participated actively. It still demonstrated the human propensity to make biased decisions which also affected trained professionals in a more realistic setting.

The comforting finding from this experiment is that the quality of regulatory judgment processes by professionals was significantly higher than the judgments of students. Professionals were able to recall more correct arguments but, more importantly, they were also significantly more accurate. On average, students made twice as many mistakes as professional participants. Almost half of the professionals made no mistake at all while recalling information, whereas only 8% of the students was totally flawless.

In addition to that, the regulatory professionals seemed to be somewhat more extreme in their judgments of the case, with a much larger standard deviation and less consistency as a group. Several qualitative responses during the workshops following on the experiment strengthened this impression of professional dissensus. Such inconsistencies could point at over-confidence, a prevalent decision-bias amongst experienced professionals (Dudley & Xie, Citation2020). However, subsequent analyses did not confirm this impression. Both Levene’s test for equality of variances and the Brown Forsyth test suggested the distinction between the two groups was not significant on this relatively small sample.

Ultimately, thus, at least in this specific case, professionals outperformed students, notably because they were more careful and precise in their judgments. The training (see also Kovera & McAuliff, 2000) and experience (Moulin et al., Citation2018; Espinosa-Pike & Barrainkua, Citation2016) of professional regulators may significantly diminish accuracy-problems in regulatory judgment. An alternative interpretation could also be that professionals are not necessarily more accurate in their judgments but, rather, that the task was simply more familiar to them. This does not matter materially (they are still more accurate), yet it matters greatly for causality. One way to control for this would be to conduct a new judgment experiment, but now with a realistic student-task and then again compare the judgments of the two groups.

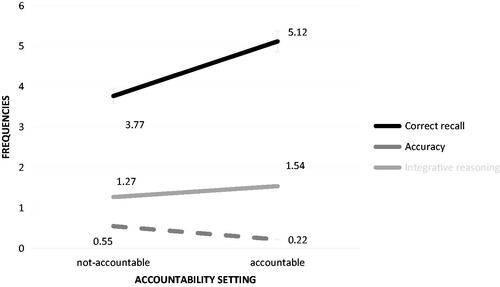

Accountability improves judgment processes

Finally, we analyzed the effects of pre-exposure accountability on regulatory judgment processes. As explained earlier, this was only possible for the third sample consisting of judges and legal professionals. This last experiment confirmed that accountability indeed raises the stakes for regulators which induces them to put more time into a task, which is rewarded by a better task performance; in this case a higher quality of regulatory judgment process. Accountability clearly improved the quality of judgment processes in terms of several measures, both t-tests and a one-way ANOVA showed. Under the condition of accountability, participants were able to recall more arguments correctly (F = 7,421, p = 0.008) and they were also more accurate and made significantly fewer mistakes (F = 5,106, p = 0.027). There was no significant effect on reasoning style, which was separately confirmed with a Chi-Square test.

below visualizes the effect of accountability on these measures of regulatory judgment processes.

Figure 3. The effects of accountability on the quality of regulatory judgment processes. * This figure is based on sample 3. The figure shows that the mean responses from the group of non-accountable subjects differ from the accountable subjects, in terms of (1) Correct recall (number of correctly recalled items), (2) Accuracy (Number of errors), and (3) integrative reasoning style (1 = “bulleting”; 0 = “reasoning”).

Our findings tie in with the original findings from Tetlock (Citation1983), the host of psychological studies on the effects of accountability on judgment (Hall et al., Citation2017), as well as earlier studies finding an order effect on professional judgment by regulators. In a sense, our findings confirm that regulators are indeed human (see also Dudley & Xie, Citation2020; Helm et al., Citation2016), prone to make mistakes yet correctable with accountability. This signals the relevance of operational accountability (Biela & Papadopoulos, Citation2014) for regulatory agencies and effective organizational procedures that ascertain that regulatory decisions in individual cases are reviewed by salient others. We will discuss the policy implications of this finding in the subsequent discussion section.

Discussion

This study was inspired by general psychological insights in judgment and accountability aiming to gauge their scope and relevance for regulatory professionals. The experiment added more realism to a classic study although it still was artificial in important ways. The study nevertheless engages with the fundamental issue of the quality of regulatory judgment under conditions of uncertainty and ambiguity. The study is one of the first to study the effects of accountability on judgment processes of professional regulators, confirming the risk of bias, low-effort strategies but also the promise of accountability for improving judgment. Having said this, the results must be read with care as the study inevitably has limitations. To begin with, the classroom settings introduced potential noise to the experiment with unknown effects. Also, this was a small-N study with a modest sample size (yet comparable to Tetlock, Citation1983). One should also be careful to generalize the findings from these specific samples of professionals to all professionals in the regulatory state. Further, as we tested the ecological validity of the effects of accountability on the quality of regulatory judgment processes, experimental realism was higher than in the original experiment yet still far from complete. The subjects were well aware that this was an artificial case which is likely to affect both cognitive effort and the power of felt accountability. Even in the third sample, participants knew very well that it was a manufactured form of accountability without real consequences other than losing face toward one’s peers. And the decisional task was deliberately set in a familiar yet not specific setting, taking norms, routines and practices out of the equation, while these are obviously very important for regulatory practice (Thomann et al., Citation2018). Further research is needed on the regulatory judgment of real cases by regulators to further explore the salience of regulatory judgment problems in regulatory practice (see also Helm et al., Citation2016; Wainberg et al., Citation2013; Wolfe et al., Citation2017) and the effects of accountability.

Despite these limitations, we believe our experimental research underscores the relevance of operational accountability for the quality of judgment processes in regulatory governance. This is a relevant yet difficult prospect. The issue is relevant, as judgment errors are easily made in agencies assessing scores of individual cases under conditions of uncertainty, ambiguity and time-pressure. Regulatory professionals, as humans, are prone to make errors in their decisions which can be remedied to some extent with organizational measures, such as accountability (Dudley & Xie, Citation2020). And, conversely, there are studies showing that major policy crises can result from failures in accountability, such as with Deepwater Horizon, the largest oil spill in US history (Mills & Koliba, Citation2015). Several more recent regulatory policies, such as risk-based regulation (Black & Baldwin, Citation2010), principle-based accounting (Cohen et al., Citation2013) and performance-based regulation (Coglianese et al., Citation2003), put high demands on the quality of judgment. The same goes for judgment issues such as assessing the veracity of expert advice in cases (Spellman, Citation2010), interpreting eye-witnesses (Tadei et al., Citation2014), and reading through emotional language in reports and briefs (Black et al., Citation2016). In all of those cases it can be expected that regulators will attain higher levels of regulatory judgment when they feel accountable.

Unfortunately, accountability is a difficult solution as independence is crucial to the functioning of regulatory authorities. The growth in regulatory agencies was predicated on the conviction that credible and effective regulation requires organizational independence (Black, Citation2008; Koop & Hanretty, Citation2018). And independence is often interpreted to mean the absence of accountability. The policy challenge of our findings is that it underscores the necessity to look for forms of accountability that “fit” (Schillemans, Citation2016) the specific operational demands and constraints of regulatory governance. We believe this study offers at least three important insights for regulatory policy.

The first insight for policy practice is that this study suggests that regulators as humans are obviously imperfect and may make biased judgments. This problem aggravates with time-pressures, uncertainties and reliance on single individuals making a call. This suggests it is important to ascertain balanced and structured flows of information reducing risks of bias. It is important to provide peer feedback to those who make judgments about final outcomes and assessments. And it is important for individual regulators to be aware of the risk of judgment errors and over-confidence. These policy implications seem mundane but are crucial and, in our experience teaching regulatory professionals, not always sufficiently guarded in everyday regulatory practice (cf. Coffeng, Citation2022).

A second take-away for regulatory policy is that even independent regulatory authorities need effective forms of operational accountability. Earlier, Maggetti (Citation2010; see also Scott, Citation2000) argued that accountability is a crucial issue for regulatory governance and is difficult to tackle with traditional hierarchical measures. He identified two possible “solutions.” The first refers to internal accountability in networks, where one’s decisions are reviewed by professional peers. This is likely to improve the quality of operational accountability. The second refers to horizontal accountability, where one’s decisions are reviewed by reputed societal actors. Both peer-accountability and horizontal (non-hierarchical) accountability to high-status forums were manipulated in the third sample of this study. The results suggest that operational accountability for individual judgments by regulators, using peers and external experts, may indeed enhance the quality of regulatory judgment processes.

A third consequence for regulatory policy is that it is important in the design of regulations not only to focus on what is expected of regulatees, but also to build in cues or “nudges” for regulatory professionals that may boost the quality of their judgments (cf. Dudley & Xie, Citation2020). These cues would need to differ with the type of judgment task the regulation implies for the regulator (cf. Schillemans, Citation2016; Wright & Houston, Citation2021). If the policy is about strict compliance with finite standards, a more “traditional” compliance focus is evident. However, newer forms of regulation such as performance-based and risk-based regulation put higher cognitive demands on regulators. Regulatory agencies would need to (further) develop operational forms of accountability signaling to the regulator that “good judgment” actually is what is expected. Being open to all sides of issues is conducive of high quality decision processes (Lee, Citation2013) stimulating high quality decision processes (see also Koop & Hanretty, 2018). In effect, we should be looking for expected qualitative feedback, comparable to nudging (Dudley & Xie, Citation2020), which stimulates regulators to employ system II cognitive processes.

Finally, with this paper we have aimed to connect behavioral research and to the study of regulatory governance in more realistic settings. To further understand issues of regulatory judgment process and its antecedents (such as accountability) it is necessary to further increase the realism of studies. Real-world regulatory practice is dependent on specified norms and procedures that regulators have to adopt and are “guarded” by sanctions. These were deliberately missing from our scenario but are undoubtedly relevant to real-world operational accountability. Important is also that they help to address consistency-problems. Future studies could include real regulations and accountability. This would necessitate uniform samples of participants, such as market regulators or health care inspectors, working on a real case with a specific regulation under varying conditions of accountability. This would further integrate behavioral knowledge with practices and insights from regulation and governance and improve our knowledge through greater experimental realism.

Conclusion

The quality of regulatory judgment is a key behavioral issue in the regulatory state (Majone, Citation1994). Several studies in regulation, public administration and governance have pointed at important concerns about regulatory judgment, while psychological studies have in general questioned human capacities for unbiased and complex judgments (cf. Kahneman, Citation2011 and many others). While laboratory studies suggest that accountability might be conducive of the quality of judgment this has not been tested in more realistic public sector settings. Against this background, this paper has set out to study the ecological validity (Brewer & Crano, Citation2000) of the link between accountability and judgment processes in a more realistic context. The paper suggests that professional regulators are more accurate and “better” in judgment tasks than students, while still susceptible to judgment errors and correctable by felt accountability. The implications for the study and practice of regulatory governance have been discussed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (48.1 KB)Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to the six organizations, the various contact persons and the 248 individual participants who have enabled me to conduct this study. I would also like to thank the five regulatory experts providing advice on the study design. And I would like to thank Marija Aleksovska, Ivo Giesen, Maj Jeppesen, Manuel Quaden, and Kees van der Wel for assistance and collaboration in various forms on this project.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thomas Schillemans

Thomas Schillemans is a professor of public governance: accountability, behavior and institutions, at Utrecht University School of Governance, the Netherlands. He has published widely on public accountability, public governance and the role of the media. Combining psychological and institutional methods and insights is one of his current main research interests.

Notes

1 A web of science query found 48 recent studies in which the quality of regulatory judgment (including auditors and judges) was studied as a salient problem. See Appendix 4 for an overview of judgment problems identified in that literature.

2 In line with Tetlock (Citation1983) we used two types of accountability in the first two samples; in this case accountability to an external expert reviewing one’s judgment and accountability to the organization itself, which was expected to moderate judgments (Harari & Rudolph, Citation2017). These were developed with the advice from five experts in regulatory governance.

3 The avoidance of bias was not integrated in this analysis as this is a group-level and not an individual level variable.

References

- Aleksovska, M. (2021). Accountable for what? The effect of accountability standard specification on decision-making behavior in the public sector. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(4), 707–734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2021.1900880

- Aleksovska, M., Schillemans, T., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2019). Lessons from five decades of experimental and behavioral research on accountability: A systematic literature review. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 2(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.22.66

- Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably irrational. The hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York: Harper Collins.

- Ashton, R. H. (2000). A review and analysis of research on the test–retest reliability of professional judgment. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0771(200007/09)13:3<277::AID-BDM350>3.0.CO;2-B

- Bednarik, P., & Schultze, T. (2015). The effectiveness of imperfect weighting in advice taking. Judgment and Decision Making, 10(3), 265–276.

- Biela, J., & Papadopoulos, Y. (2014). The empirical assessment of agency accountability: A regime approach and an application to the German Bundesnetzagentur. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 80(2), 362–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852313514526

- Black, J. (2008). Constructing and contesting legitimacy and accountability in polycentric regulatory regimes. Regulation & Governance, 2(2), 137–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2008.00034.x

- Black, J., & Baldwin, R. (2010). Really responsive risk‐based regulation. Law & Policy, 32(2), 181–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.2010.00318.x

- Black, R. C., Hall, M. E., Owens, R. J., & Ringsmuth, E. M. (2016). The role of emotional language in briefs before the US Supreme Court. Journal of Law and Courts, 4(2), 377–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/685660

- Bouwman, R., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2016). Experimental public administration from 1992 to 2014: A systematic literature review and ways forward. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 29(2), 110–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-07-2015-0129

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x

- Braithwaite, J. (2011). The essence of responsive regulation. UBCL Review, 44, 475–520.

- Brewer, M. B., & Crano, W. D. (2000). Research design and issues of validity. In S. T. Fiske, H. T. Reis, & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 3–16). Cambridge University Press.

- Cianci, A. M., Houston, R. W., Montague, N. R., & Vogel, R. (2017). Audit partner identification: Unintended consequences on audit judgment. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 36(4), 135–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51629

- Coffeng, T. (2022). Bias in supervision: A social psychological perspective on regulatory decision-making. Utrecht University.

- Coglianese, C., Nash, J., & Olmstead, T. (2003). Performance-based regulation: Prospects and limitations in health, safety, and environmental protection. Admin. L. Rev, 55, 705.

- Cohen, J. R., Krishnamoorthy, G., Peytcheva, M., & Wright, A. M. (2013). How does the strength of the financial regulatory regime influence auditors' judgments to constrain aggressive reporting in a principles-based versus rules-based accounting environment? Accounting Horizons, 27(3), 579–601. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-50502

- Collins, P. M., Jr, Corley, P. C., & Hamner, J. (2015). The influence of amicus curiae briefs on US Supreme Court opinion content. Law & Society Review, 49(4), 917–944. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12166

- Cooper-Martin, E. (1994). Measures of cognitive effort. Marketing Letters, 5(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993957

- Cushing, B. E., & Ahlawat, S. S. (1996). Mitigation of recency bias in audit judgment: The effect of documentation. Auditing, 15(2), 110.

- Cutler, B. L., & Kovera, M. B. (2011). Expert psychological testimony. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(1), 53–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410388802

- Dudley, S. E., & Xie, Z. (2019). Nudging the nudger: Toward a choice architecture for regulators [Working paper]. GW Regulatory Studies Center.

- Dudley, S. E., & Xie, Z. (2020). Designing a choice architecture for regulators. Public Administration Review, 80(1), 151–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13112

- Espinosa-Pike, M., & Barrainkua, I. (2016). An exploratory study of the pressures and ethical dilemmas in the audit conflict. Revista de Contabilidad, 19(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsar.2014.10.001

- Feitsma, J. (2019). Brokering behaviour change: The work of behavioural insights experts in government. Policy & Politics, 47(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15174915040678

- Fernández-I-Marín, X., Jordana, J., & Bianculli, A. (2015). Varieties of accountability mechanisms in regulatory agencies. In A. Bianculli, X. Fernández-i-Marín, & J. Jordana (Eds.), Accountability and regulatory governance (pp. 23–50). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., Jilke, S., Olsen, A. L., & Tummers, L. (2017). Behavioral public administration: Combining insights from public administration and psychology. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12609

- Hall, A. T., Frink, D. D., & Buckley, M. R. (2017). An accountability account: A review and synthesis of the theoretical and empirical research on felt accountability. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2052

- Han, Y., & Robertson, P. J. (2021). Public employee accountability: An empirical examination of a nomological network. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(3), 494–522.

- Harari, M. B., & Rudolph, C. W. (2017). The effect of rater accountability on performance ratings: A meta-analytic review. Human Resource Management Review, 27(1), 121–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.09.007

- Helm, R. K., Wistrich, A. J., & Rachlinski, J. J. (2016). Are arbitrators human? Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 13(4), 666–692. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12129

- Hood, C., James, O., Jones, G., Scott, C., & Travers, T. (1998). Regulation inside government: Where new public management meets the audit explosion. Public Money and Management, 18(2), 61–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00117

- Hurley, P. J. (2015). Ego depletion: Applications and implications for auditing research. Journal of Accounting Literature, 35, 47–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acclit.2015.10.001

- Jordana, J., Levi-Faur, D. I., & Marín, X. F. (2011). The global diffusion of regulatory agencies: Channels of transfer and stages of diffusion. Comparative Political Studies, 44(10), 1343–1369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011407466

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

- Kim, C. (2017). An economic rationale for dismissing low‐quality experts in trial. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 445–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sjpe.12129

- Koop, C., & Hanretty, C. (2018). Political independence, accountability, and the quality of regulatory decision-making. Comparative Political Studies, 51(1), 38–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017695329

- Koop, C., & Lodge, M. (2017). What is regulation? An interdisciplinary concept analysis. Regulation & Governance, 11(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12094

- Kovera, M. B., & McAuliff, B. D. (2000). The effects of peer review and evidence quality on judge evaluations of psychological science: Are judges effective gatekeepers? Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4), 574–586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.4.574

- Lee, R. K. (2013). Judging judges: Empathy as the Litmus Test for Impartiality. University of Cincinnati Law Review, 82, 145.

- Lerner, J. S., & Tetlock, P. E. (1999). Accounting for the effects of accountability. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 255–275.

- Libby, R., & Trotman, K. T. (1993). The review process as a control for differential recall of evidence in auditor judgments. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 18(6), 559–574. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)90003-O

- Lindholm, T. (2008). Who can judge the accuracy of eyewitness statements? A comparison of professionals and lay‐persons. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22(9), 1301–1314. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1439

- Maggetti, M. (2010). Legitimacy and accountability of independent regulatory agencies: A critical review. Living Reviews in Democracy, 13, 2.

- Maggetti, M., Ingold, K., & Varone, F. (2013). Having your cake and eating it, too: Can regulatory agencies be both independent and accountable? Swiss Political Science Review, 19(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12015

- Majone, G. (1994). The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics, 17(3), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389408425031

- Maroney, T. A. (2011). Emotional regulation and judicial behavior. California Law Review, 99, 1485.

- Martinov-Bennie, N., & Pflugrath, G. (2009). The strength of an accounting firm’s ethical environment and the quality of auditors’ judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(2), 237–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9882-1

- May, P. J. (2007). Regulatory regimes and accountability. Regulation & Governance, 1(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2007.00002.x

- Maynard‐Moody, S., & Musheno, M. (2012). Social equities and inequities in practice: Street‐level workers as agents and pragmatists. Public Administration Review, 72(s1), S16–S23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02633.x

- McDermott, R. (2002). Experimental methods in political science. Annual Review of Political Science, 5(1), 31–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.5.091001.170657

- Mero, N. P., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1995). Effects of rater accountability on the accuracy and the favorability of performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(4), 517–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.4.517

- Mills, R. W., & Koliba, C. J. (2015). The challenge of accountability in complex regulatory networks: The case of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Regulation & Governance, 9(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12062

- Moulin, V., Mouchet, C., Pillonel, T., Gkotsi, G. M., Baertschi, B., Gasser, J., & Testé, B. (2018). Judges’ perceptions of expert reports: The effect of neuroscience evidence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 61, 22–29.

- Ossege, C. (2012). Accountability–Are we better off without it? An empirical study on the effects of accountability on public managers' work behaviour. Public Management Review, 14(5), 585–607. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2011.642567

- Overman, S., Schillemans, T., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2021). A validated measurement for felt relational accountability: Gauging the account holder’s legitimacy and expertise. Public Management Review, 23(12), 1748–1767. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1751254

- Pitz, G. F., & Sachs, N. J. (1984). Judgment and decision: Theory and application. Annual Review of Psychology, 35(1), 139–164.

- Pollitt, C., & Hupe, P. (2011). Talking about government: The role of magic concepts. Public Management Review, 13(5), 641–658. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.532963

- Rausch, A., & Brauneis, A. (2015). The effect of accountability on management accountants’ selection of information. Review of Managerial Science, 9(3), 487–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-014-0126-8

- Samaha, A. M. (2018). If the text is clear-lexical ordering in statutory interpretation. Notre Dame Law Review, 94, 155.

- Schillemans, T. (2016). Calibrating public sector accountability: Translating experimental findings to public sector accountability. Public Management Review, 18(9), 1400–1420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1112423

- Scott, C. (2000). Accountability in the regulatory state. Journal of Law and Society, 27(1), 38–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6478.00146

- Sinclair, A. (1995). The chameleon of accountability: forms and discourses. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(2-3), 219–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0003-Y

- Spellman, B. A. (2010). Judges, expertise, and analogy. In D. Klein & G. Mitchell (Eds.), The psychology of judicial decision making (pp. 149–163). Oxford University Press.

- Suedfeld, P., & Tetlock, P. E. (2014). Integrative complexity at forty: Steps toward resolving the scoring dilemma. Political Psychology, 35(5), 597–601. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12206

- Svanberg, J., & Öhman, P. (2016). Does ethical culture in audit firms support auditor objectivity? Accounting in Europe, 13(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2016.1164324

- Szmer, J., & Ginn, M. H. (2014). Examining the effects of information, attorney capability, and amicus participation on US Supreme Court decision making. American Politics Research, 42(3), 441–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X13502219

- Tadei, A., Finnilä, K., Korkman, J., Salo, B., & Santtila, P. (2014). Features used by judges to evaluate expert witnesses for psychological and psychiatric legal issues. Nordic Psychology, 66(4), 239–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2014.963648

- Tetlock, P. E. (1983). Accountability and the perseverance of first impressions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46(4), 285–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3033716

- Tetlock, P. E. (1992). The impact of accountability on judgment and choice: Toward a social contingency model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 331–376.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

- Thomann, E., & Sager, F. (2017). Hybridity in action: Accountability dilemmas of public and for-profit food safety inspectors in Switzerland. In P. Verbruggen & H. Havinga (Eds.), Hybridization of food governance (pp. 100–120). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Thomann, E., Hupe, P., & Sager, F. (2018). Serving many masters: Public accountability in private policy implementation. Governance, 31(2), 299–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12297

- Tuijn, S. M., Van Den Bergh, H., Robben, P., & Janssens, F. (2014). Experimental studies to improve the reliability and validity of regulatory judgments on health care in the Netherlands: A randomized controlled trial and before and after case study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 20(4), 352–361.

- Wainberg, J. S., Kida, T., Piercey, M. D., & Smith, J. F. (2013). The impact of anecdotal data in regulatory audit firm inspection reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 38(8), 621–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2013.10.005

- Wolfe, C. J., Fitzgerald, B. C., & Newton, N. J. (2017). The effect of partition dependence on assessing accounting estimates. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 36(3), 185–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51666

- Wright, J. E., & Houston, B. (2021). Accountability at its finest: Law enforcement agencies and body-worn cameras. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(4), 735–757. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2021.1916545