Abstract

This article presents an ex-post evaluation of the performance of Dutch Design-Build-Finance-Maintain (DBFM) infrastructure projects compared to Design and Construct (D&C) contracts, which uses quantitative (financial project data and survey) and qualitative (interviews) data. Drawing on institutional theory, notably the economic institutionalism inspired-contractual perspective and the sociological institutionalism-oriented collaborative perspective, the evaluation focuses on four performance indicators—cost, time, quality, and innovation—and five public–private partnership (PPP) performance drivers—private financing, performance-dependent payments, bundling (i.e., the integrated nature of contracts), risk transfer, and collaboration. It was found that the DBFM projects performed similarly to, or better than, the D&C contracts. The impact of bundling on innovation was positive, while its impact on quality was inconclusive. The collaboration proved to be a strong driver for performance and innovation but was not stronger in DBFM projects compared to D&C projects. Over time, collaboration and performance improved suggesting that besides project characteristics, PPP performance is influenced by the way actors deal with contracts and by the gradual process by which they learn to do so. Theoretically, this means that historical institutionalism is part of the explanation of PPP performance.

1. Introduction: evaluating the performance of PPPs

Public–private partnership (PPP)—an instrument commonly used worldwide to realize public infrastructure and services—is now well-established in both government rhetoric and policy practice. The underlying assumption is that cooperation between public and private partners will result in better, more effective, and more efficient infrastructure and services (Grimsey & Lewis, Citation2005; Koppenjan, Citation2008). A core theme in the PPP literature is hence performance (Palcic et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2018). However, the complexity of PPP projects, their organizational and contractual arrangements, their long timespan, and the lack of project-level data, make evaluating PPP performance a challenging task (Chen et al., Citation2016; Hodge, Citation2010; Jeffares et al., Citation2013). Despite PPP’s long history, many experiences with PPPs, and the growing PPP literature (Shi et al., Citation2020), relatively few comparative evaluations of PPP performance have analyzed how PPPs perform compared to other types of procurement (Petersen, Citation2019). Such evaluations are, however, much needed (Petersen, Citation2019). This is especially true because the motivation to opt for PPP is based on the ex-ante expectation that PPP adds value compared to traditional types of public procurement of infrastructure and related services.

Most comparative PPP evaluations are based on ex-ante value-for-money assessments. These are criticized because, instead of analyzing realized performance, the report projected performance, based on assumptions that can be, and are, contested (Boers et al., Citation2013; Pollock et al., Citation2007). Evaluations of ex-post, realized performance are limited in number. Insofar as they exist, they present opposing conclusions. Consider, for instance, the literature on ex-post PPP performance compared to traditional procurement regarding cost performance and value-for-money (see Petersen, Citation2019). Some authors have reported higher value-for-money for PPPs (e.g., Meduri & Annamalai, Citation2013; Oliveira dos Reis & Cabral, Citation2017; Raisbeck et al., Citation2010), others have reported lower performance (e.g., Daito & Gifford, Citation2014; Froud & Shaoul, Citation2001; Reeves & Ryan, Citation2007), and yet others have found no significant differences between PPPs and traditional procurement (e.g., Atmo et al., Citation2017; Hong, Citation2016; Whittington, Citation2012). The uncertainty about the performance of PPPs is further enhanced by the various ways in which performance is defined and measured, and specifically the lack of consensus about how value-for-money should be defined and measured (Hodge & Greve, Citation2017).

Given these points, it is therefore important to (1) evaluate ex-post realized PPP performance compared to traditional procurement and (2) explore and test this performance for specific sectors and countries. Petersen (Citation2019) identified this as an important challenge that warrants attention, to improve the evidence for, and understanding of, PPP performance. This article addresses this challenge in the case of road and waterway infrastructure (sector) in the Netherlands (country).

Empirically, a wide array of partnership forms can be identified. One of the most discussed PPP forms in the international literature, and in infrastructure specifically, is the Design-Build-Finance-Maintain (DBFM) contract. In DBFM, public actors procure the designing, building, and maintenance of a public infrastructure project and related services from a private consortium for a relatively long period of time through an integrated contract. This private consortium also finances most of the project activities (Yescombe, Citation2007). It consists of a Special Purpose Company (SPC) as the contract partner of the public procurer. Private investors and construction firms are represented in the SPC. The SPC arranges investments and loans from financiers and banks, and it has subcontracts with an Engineering, Procurement, and Construction Company (EPC) and with a Maintenance Company (MTC), which are responsible for the construction and the maintenance of the project, respectively.

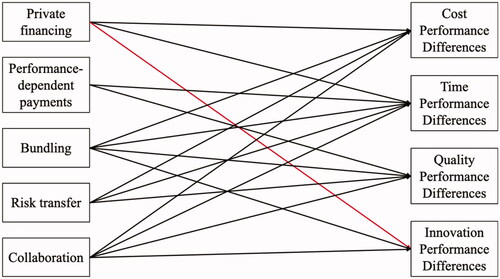

In the present article, the expectations about a higher performance in Dutch road and waterway infrastructure projects governed by DBFM contracts are evaluated in terms of cost, time, quality, and innovation. Regarding the second part of the challenge (see above), this article evaluates five dominant explanations or drivers of the expected higher performance of PPPs that are often mentioned in the literature: private financing, performance-dependent payments, bundling (i.e., the integrated nature of contracts), risk transfer, and collaboration.

Theoretically, the evaluation presented here draws on institutional theory, more especially on the economic institutionalism-inspired contractual perspective on PPP (building on principal-agent and transaction costs theory) and the collaborative perspective inspired by ideas on relational contracting, governance, and sociological institutionalism (Deakin & Michie, Citation1997; Huxham & Vangen, Citation2005; Lowndes & Roberts, Citation2013; Williamson, Citation1996).

The empirical and analytical strategy of this article revolves around the comparison of Dutch road and waterway infrastructure projects with DBFM and Design and Construct (D&C) contracts. We present an evaluation of the performance of 21 Dutch DBFM projects—compared to the performance of D&C projects—procured and implemented in the last 15 years by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management in the Netherlands (Koppenjan et al., Citation2020a; see Appendix 1). Whereas DBFM is considered a type of PPP, D&C is not because it does not involve private financing (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2021; Yescombe, Citation2007). The evaluation involved multiple datasets—financial project data, a survey, and interviews—analyzed using different methods. The various data sources and multiple methods enabled us to get a holistic view of the performance of the studied projects. The research question is as follows: Do infrastructure projects with DBFM contracts outperform projects with D&C contracts (in terms of cost, time, quality, and innovation) and what drivers explain performance differences?

In section 2, it is explained how each of the said five drivers differs for DBFM and D&C, and how DBFM is expected, therefore, to result in higher levels of performance. In section 3, we present the data and methods. In section 4, the main results of the evaluation are presented. We finish in section 5 with some reflections on PPPs and their performance.

2. Theory on PPP performance

Two theoretical perspectives can be discerned regarding PPP performance. The contractual perspective—inspired by economic institutionalism ideas, such as principal–agent theory and transaction costs theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Lowndes & Roberts, Citation2013; Williamson, Citation1996)—is the dominant one. In this perspective, the partnership is seen as a principal–agent relationship between a principal (public partner; commissioner) and an agent (private partner; consortium) (see, e.g., Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2021). Both are rational actors making calculations to realize their own preferences. Their relationship is characterized by diverging preferences and information asymmetry: the principal hires the agent and the principal is dependent upon the agent to get information about the agent’s performance. The agent may act opportunistically, by misinforming the principal about performance while wriggling out of obligations, taking short cuts, economizing on quality, or trying to change contract conditions. To ensure performance, the contract and its enforcement are important. In the contract, the principal can specify the agent’s required performance and obligations. However, the limitations and the high transaction costs of collecting information mean that a contract per definition is incomplete. It, therefore, needs to be supplemented by additional governance mechanisms (Williamson, Citation1979). Through monitoring and sanctioning, the principal can incentivize the agent to perform according to the contract conditions. This implies that the principal has to incur costs—transaction costs—to negotiate a good contract and to monitor and enforce it. The DBFM contract, therefore, has several features that create incentives that are considered able to create added value in terms of performance (see, e.g., Reynaers, Citation2014) compared to more traditional contract forms, such as, in the Netherlands, D&C.

The second theoretical perspective that is relevant to explain PPP performance emphasizes the relational aspects of the management of PPP contracts and is inspired by ideas on relational contracting, governance, and sociological institutionalism (Deakin & Michie, Citation1997; Lowndes & Roberts, Citation2013). Whereas economic institutionalists see monitoring and sanctioning as ways to deal with the incompleteness of contracts, this relational or collaborative perspective emphasizes the need to manage the contractual relationship throughout the contract period and to develop commitment and trust (Brown et al., Citation2016; Nooteboom, Citation2002; Poppo & Zenger, Citation2002). Trust and commitment are built-in processes of intensive interactions and in management activities aimed at building high-quality relationships by motivating actors, acknowledging interests, and sharing risks and responsibilities (Huxham & Vangen, Citation2005; Klijn et al., Citation2010; Weihe, Citation2009). Instead of a principal–agent relationship, a collaborative partnership is pursued to jointly address problems and unexpected developments that become manifest during the contract period (Barretta et al., Citation2008; Reeves, Citation2008; Smyth & Edkins, Citation2007).

Despite the different and contradictory directions in which these two perspectives seek solutions for dealing with the incompleteness of contracts, they are not mutually exclusive. The collaborative perspective addresses contractual relationships, including contracts and contract management. This perspective implies that, although contracts shape and constrain interactions, they do not determine them. Rather, the combination of contractual and collaborative mechanisms results in a certain performance (Warsen et al., Citation2019; Weihe, Citation2009). This insight suggests that, in addition to the features of DBFM, other mechanisms, such as a collaborative approach are required to realize a performance that results in added value compared to more traditional contracts, such as, in the Netherlands, D&C contracts.

In this study, we distinguish five drivers of DBFM performance. Four of these are based on features of DBFM contracts—private financing, performance-dependent payments, bundling, and risk transfer—and the fifth is collaboration.

2.1. Private financing

Private financing features in DBFM but not in D&C. In DBFM contracts, the private consortium finances the project upfront and needs to recoup its investments during the project (Yescombe, Citation2007). It has to obtain loans from banks and equity from private investors. This implies that, compared to publicly financed D&C projects, financing risks are transferred to the private consortium. Because the financing risks are transferred to the private partner, banks and equity providers become involved in the project; and these are known to be risk-averse and demand high-quality risk management (Demirag et al., Citation2011). This is expected to contribute to better identification, allocation, and mitigation of risks and as a consequence—because effective risk management reduces the impact of events on the project planning—a better cost performance (in terms of on-budget delivery) and time performance (in terms of on-time delivery) (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2021). Because private financing induces risk-averse behavior, it can have a negative effect on the development of innovations, which consequently are often only of an incremental nature (Hueskes, Citation2019).

2.2. Performance-dependent payments

Cashflow is generated in a PPP project by payments to the private consortium, either by users or by governments. In many countries, private consortia recoup their investments by collecting tolls from the users of road infrastructure (i.e., usage-based payments). In the Netherlands however, inter alia because of the density of the road network and because a budget deficit is not what motivates the government to enter into PPPs, payments to the private consortium are based on the performance of the service provided (i.e., availability-based payments or service-based payments). In countries where the public budget is insufficient, toll roads are more common (European PPP Expertise Centre, Citation2015; McQuaid & Scherrer, Citation2010). In projects with D&C contracts, the private consortium is also paid based on performance, but mostly for performance delivered in the construction phase of the project, meaning that its business case does not depend on regular payments after the construction has finished.

In the case of DBFM, when the infrastructure is unavailable—e.g., because a lane or road is being repaired or because of regular maintenance—the private partner will receive lower payments from the public partner or payments will be delayed, thereby negatively impacting its profits. It, therefore, has an incentive to invest in high-quality infrastructure that requires fewer repairs and less maintenance. This effect is absent in D&C and therefore DBFM projects are expected to result in higher quality performance in terms of both the sustainability of the infrastructure (Lenferink et al., Citation2013) and road safety (Albalate & Bel-Piñana, Citation2019). Because the payments are tied to the timely achievement of milestones agreed in the contract, performance-dependent payments are expected to positively influence time performance also.

2.3. Bundling (integrated contracts)

In DBFM contracts, various project phases that traditionally are contracted out separately are now integrated. Both D&C and DBFM contracts are integrated contracts (Culp, Citation2011; Lenferink et al., Citation2013), but maintenance is included in DBFM. The inclusion of maintenance allows for the realization of economies of scope and lifecycle optimization. This implies that, during the design and construction phases of the project, additional investments are made in building strong and high-quality infrastructure (quality performance), so that less maintenance is needed. Bundling means that clever combinations can be made in how the design, construction, and maintenance processes are planned and executed so that costs can be saved in terms of maintenance costs (cost performance in terms of lifecycle optimization) and time can be saved by parallelizing design and construction processes (time performance) (Lenferink, Citation2013). Because achieving lifecycle optimization requires novel and smart solutions, bundling is said to require innovative solutions (innovation). In integrated contracts that include maintenance, the contract details the services that need to be provided by the private consortium (outputs in terms of mainly road availability and safety) and not the inputs, and this is said to provide “enhanced opportunities and incentives for bidders to fashion innovative solutions to meet those requirements” (Lewis, Citation2021, p. 41).

2.4. Risk transfer

DBFM implies the transfer of risks related to designing, constructing, financing, and maintaining the project from the public partner to the private consortium. Besides the transfer of these risks related to the various project phases, responsibility for managing the connections between these phases is also transferred (Verweij, Citation2015). As a consequence, the DBFM contract has been characterized as a Bahamas Model (Hussain & Siemiatycki, Citation2018; Koenen, Citation2016), unburdening the public partner and reducing the workload involved in the management of the contract. As DBFM implies that government procures a service, it no longer has to worry about how the project is realized, managed, or maintained. The government can focus on steering performance, which in the case of infrastructure projects in the Netherlands relates mainly to road availability and safety (Rijkswaterstaat, Citation2011). As it is assumed that private parties are better at project decision making and management, and because the involved private financiers will ensure better risk management, DBFM is expected to result in a reduction of the risks related to cost and time overruns, to underperformance in terms of quality, and to overall project failure (Flyvbjerg, Citation2009).

2.5. Collaboration

DBFM contracts that are managed collaboratively will result in better performance. In collaborations, enhanced by relational governance, trust will develop, as a result of which public and private partners will be more inclined to share risks and resources, be receptive to the problems with which their partners have to deal, and be prepared to jointly seek solutions, thereby generating the conditions for added value and collaborative advantages (Casady et al., Citation2019; Ghobadian et al., Citation2004; Huxham & Vangen, Citation2005; Ni, Citation2012; Parker & Hartley, Citation2003; Weihe, Citation2009). Of course, collaboration may also enhance the performance of traditional contracts and D&C contracts. However, the long-term and integrated nature of DBFM contracts enhances the conditions for collaboration: actors who would normally fulfill tasks separately are now brought together for an extensive period (Steijn et al., Citation2011). In addition to relational governance by the public partner, the management efforts of the SPC—which is responsible for the coordination and the integration of the activities of the complex network of involved private financiers, contractors, and subcontractors that is absent in D&C projects—are important in this respect (Grimsey & Lewis, Citation2005).

Although collaboration may result in higher transaction costs, the joint efforts are expected to result in collaborative advantages with positive impacts on cost, time, and quality, and commitment and trust increase actors’ inclination to take risks and invest in innovative solutions (Warsen et al., Citation2018). The expected relationships between the five drivers and the performance differences in terms of cost, time, quality, and innovation are summarized in .

3. Data, measurement, and methods

3.1. Data collection

We collected and analyzed multiple datasets using a mixed-methods design (Koppenjan et al., Citation2020a). The first dataset was collected between April 2018 and November 2019 (for the full details, see Verweij et al., Citation2020). Data on the project completion times and the additional work costs of the DBFM and D&C projects were collected from the Rijkswaterstaat Project Database. Sufficient data were available for 12 DBFM projects and 49 D&C projects. Only the 18 D&C projects with a contract size of at least €60 million are included in the analysis (this dataset is, therefore, N = 30). The reason is that DBFM is considered only for projects with a contract size of at least €60 million (Ministerie van Financiën, Citation2013).

The second dataset is a survey of project leaders and managers of the DBFM and D&C projects (for the full details, see Metselaar & Klijn, Citation2020). The survey data were collected from October 2019 to February 2020. We used our contacts in Rijkswaterstaat to identify the public project leaders and managers of the projects in its Project Database, and we used our contacts in Bouwend Nederland to identify the private project leaders and managers of the projects (N = 396). Nearly all the survey questions had already been validated in previous research (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016; Nederhand & Klijn, Citation2019; Warsen et al., Citation2018). We received 163 completed questionnaires, which is a response rate of 41%. This response rate is high for a survey; we think that it was achieved because respondents were requested to complete the survey through their organizations. Respondents were fairly equally distributed among the projects. The response rate for public respondents was 44% (N = 71), which is slightly higher than the 39% response rate for private respondents (N = 92). The distribution of the 163 responses over contract type is as follows: 110 responses for DBFM projects, 51 responses for D&C projects, and two responses for Design-Build-Maintenance projects.

The third dataset consists of interview transcripts (for the full details, see Koppenjan et al., Citation2020b). The data were collected from December 2019 to March 2020. We conducted 34 semi-structured interviews of approximately one hour each with persons closely involved in the organization and implementation of the 21 DBFM projects. Respondents—some involved in more than one project, including D&C projects—were selected based on their expertise and experience with DBFM. The intention was to select respondents who were representative of public and private partners involved in the DBFM projects and who were also able—based on their experience and (past) involvement in other projects—to compare these projects with D&C projects. Representatives of three respondent groups were interviewed: six respondents from Rijkswaterstaat, 22 respondents from involved construction companies, and six respondents from private financiers involved in the projects.

3.2. Performance measurement indicators

Many different performance indicators are mentioned in the literature. As suggested in the PPP literature, we used multiple performance indicators for cost performance, on-time delivery, quality, and innovation (see, e.g., Hodge, Citation2010; Jeffares et al., Citation2013; Petersen, Citation2019).

Cost performance was measured using three indicators:

Realized additional work costs, measured as the sum of the costs in Euro for additional work caused by contract changes that occurred after the contract was signed, divided by the contract size, resulting in a percentage (Verweij et al., Citation2015; Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020, Citation2021). A higher percentage indicates higher additional work costs, thus lower performance. [Project Database]

Quantitative performance perception, measured using two survey items on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from totally disagree to totally agree: (1) the costs of the project stayed within the set bandwidth and norms; and (2) the benefits of the project are in general greater than the costs (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016). [Survey]

Qualitative performance perception, is ascertained with the questions: (1) has the project been realized on-budget, and (2) has the project been realized with a reasonable return on investment for private partners? [Interviews]

Time performance was measured using the following indicators:

Realized achievement of the recommissioning milestone, measured as the actual number of days in the period between the day the contract was awarded and the day of the full recommissioning of the infrastructure after the construction activities were finished. This number of days is expressed as a percentage of the length of the period as planned on the day the contract was awarded. A higher percentage indicates an acceleration of the achievement of the milestone, thus a higher performance (Verweij et al., Citation2020; Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2021). [Project Database]

Quantitative performance perception was measured using one survey item on a 7-point Likert scale: the availability of the infrastructure developed in this project was realized within the predetermined agreed time frame. [Survey]

Quality was measured using the following indicators:

Quantitative performance perception, measured using four items on a 7-point Likert scale (see Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016; Metselaar & Klijn, Citation2020; Warsen et al., Citation2018): (1) the substantive results in this project can count on sufficient support from the involved organizations; (2) the developed solutions really deal with the problems at hand; (3) the developed infrastructure and associated assets are durable for the future; and (4) the goals of the project as formulated in the contract have been achieved. [Survey]

Qualitative performance perception, is ascertained with the question: (1) what was the level of product and process quality? [Interviews]

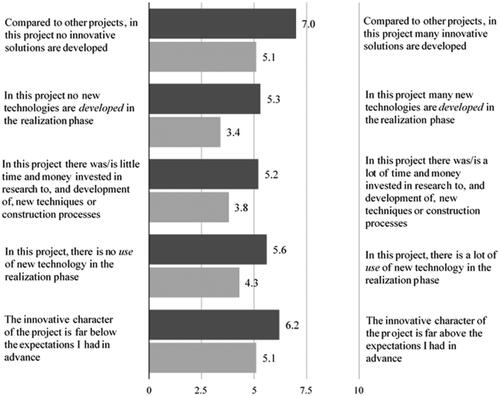

Innovation was measured using the following indicators:

Quantitative performance perception, measured using five survey items on a 7-point Likert scale (see Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016; Metselaar & Klijn, Citation2020): (1) compared to other projects, no/many innovative solutions have been developed in this project; (2–3) in this project, no/many new technologies have been (2) developed/(3) used; (4) in this project, little/much time and money are invested in researching and developing new technology or construction processes; and (5) the innovative character of this project is far below/beyond my initial expectations. [Survey]

Qualitative performance perception, is ascertained with the question: (1) do DBFM projects have fewer or more innovations than other contract forms? [Interviews]

3.3. Measurement of drivers and effects

Private financing was measured as follows:

Interview questions asking: (1) what is the role of investors and banks in DBFM and (2) what are the positive and negative effects of this on risk management?

Performance-dependent payments was measured by:

Interview question asking: what was the influence of the performance-dependent payment and associated contract instruments (in Dutch: beschikbaarheidsinstrumentarium) on the process and outcomes of the project, including infrastructure availability?

Bundling was measured by:

An interview question asking: to what extent and how did the lifecycle approach materialize?

In the survey, attention to the lifecycle nature of the project was measured by two extremes on a 10-point scale with the item: with the choice of materials and design, little/much attention was paid to the lifecycle of the project.

The effect of bundling was assessed by analyzing the correlations between the questions on lifecycle, performance, and innovation (survey) and then combining them with answers from the interviews.

Risk transfer was measured as follows:

Using a survey item on a 7-point Likert scale: no/many financial risks are shared.

Using interview questions asking: (1) how does the DBFM affect the risk profile of the projects and (2–3) what are the implications of DBFM for the allocation of risks and for the possibilities to manage risks?

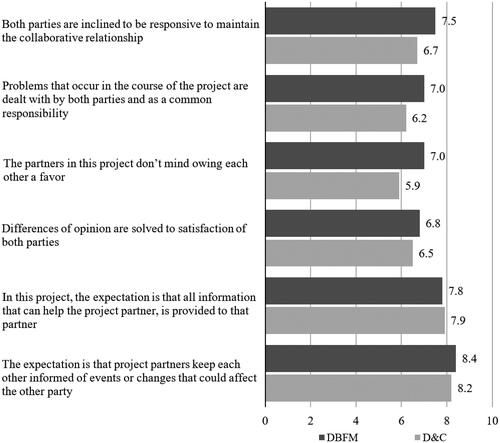

Collaboration between the public and private project partners was measured by:

Using six survey items on a 7-point Likert scale: (1) both parties tend to be very responsive to maintaining the cooperative relationship; (2) problems that arise during the project are treated by both parties as a joint responsibility; (3) the partners in this project do not mind owing each other a favor; (4) disagreements are resolved to the mutual satisfaction of both parties; (5) in this project, all information that can help the other party is provided to it; and (6) the project partners keep each other informed of events or changes that could affect the other party.

In interview question asking: has DBFM led to good collaboration between the public and private partners and between the different partners within the private consortium?

3.4. Analysis

The first dataset derived from the Project Database was analyzed using non-parametric methods applying the Mann-Whitney U test. The survey dataset was analyzed using SPSS through correlational and regression analysis. Regarding the third dataset, the interview transcripts were coded with ATLAS.ti, using the variables for codes. The respondents’ perceptions of each of the variables were compared, to find differences and commonalities in perceptions and experiences within the three respondent groups and across the groups.

4. Results

In this section, we first present the findings regarding the performance of the Dutch DBFM projects compared to the Dutch D&C projects. Then, we systematically discuss the drivers and their influence on performance.

4.1. Performance

4.1.1. Cost performance

The analysis of the data from the Rijkswaterstaat Project Database showed that the 12 DBFM projects had an average contract size of €267.006 million and an average of 13.59% of additional work costs. We compared the performance of the DBFM projects with that of the D&C projects with a contract size of at least €60 million. The results of the analysis are provided in (adapted from Verweij et al., Citation2020).

Table 1. Analysis of additional work costs performance (*sig two-tailed: p ≤ .05).

The analysis showed that the DBFM projects had fewer additional work costs as a percentage of the initial contract value (13.59%) than the D&C projects (27.78%) and that this difference is statistically significant (.048). DBFM thus had a better cost performance than D&C. The analysis of the interview data confirmed this high performance of DBFM. The respondents indicated that DBFM contracts were beneficial for the public partners, given the low bids based on which the contracts were awarded and the lower cost overruns of DBFM compared to other contract types.

Interestingly, the survey data did not confirm the better cost performance of DBFM. Regarding whether the project costs stayed within the set bandwidth and norms (first item), the DBFM projects received an average score of 5.4/10, against 6.1/10 for the D&C projects. Likewise, regarding whether the project’s benefits exceeded its costs (second item), DBFM again scored lower (6.1/10) than D&C (6.5/10). Whereas the analysis in concerns additional work costs as registered by Rijkswaterstaat, the survey measured the respondents’ perceptions about costs and their satisfaction with how costs related to expectations and benefits. However, the differences in the survey data between DBFM and D&C are small and hence statistically insignificant.

Regarding private profits and return on investment (rather than cost performance from the public partner’s perspective), it proved difficult to determine clearly the performance of the projects because of the complex, fragmented, and opaque nature of the financial arrangements between the various private parties involved. Still, the respondents confirmed that DBFM projects provided a rather safe return on investment for the banks. Financial investors, who accept a higher risk, received an internal rate of return of ∼11% (Koppenjan et al., Citation2020a). For the construction and maintenance companies, the financial results fluctuated strongly between projects. With the exception of the few projects that faced major financial losses, in general, the respondents had the impression that EPC members made a small profit, but lower than the 4% they had projected. One respondent stated:

Excessive profits are definitely not made. Projects that do not receive media attention probably have a profit margin between zero and two percent.

Another respondent explained what is considered to be a reasonable profit:

A reasonable profit depends on our expectations during the tender phase. As far as construction and maintenance is concerned, that is between 2 and 4 percent …. In the case of equity investments, between 9 and 12 percent is expected.

Because most DBFM projects in the Netherlands currently have just entered their maintenance phases (for an overview, see Koppenjan et al., Citation2020a), it was not possible yet to measure the overall financial performance over the entire project lifecycle. Respondents indicated, though, that they expected figures on return on investment to improve during the maintenance phase, when the benefits of the lifecycle approach would become manifest and smart practices would reduce maintenance costs.

4.1.2. Time performance

The analysis of the data from the Project Database showed that the seven DBFM projects for which sufficient data on the achievement of the recommissioning milestone were available had an average acceleration of 18.89% of the planned duration of the project implementation period between contract award and full recommissioning of the infrastructure. In comparison, the D&C projects with a contract size of at least €60 million had an average delay of 6.84%. These results are shown in (adapted from Verweij et al., Citation2020).

Table 2. Analysis of acceleration of the achievement of the recommissioning milestone (*sig two-tailed: p ≤ .05).

The analysis showed that the DBFM projects performed significantly better regarding the on-time delivery of the infrastructure (.022). The survey data also showed that DBFM projects were perceived to perform better in terms of on-time delivery, with an average score of 7.7/10, against 7.5/10 for the D&C projects.

4.1.3. Quality

Performance in terms of quality was assessed in the survey with four items (see section 3.2). For the third item, regarding future durability, DBFM scored better (8.5/10) than D&C (8.1/10). The D&C projects scored better regarding the other three items, but only slightly so: a score of 7.3/10 for DBFM and 7.5/10 for D&C (first item, support), a score of 7.9/10 for DBFM and 8.3/10 for D&C (second item, dealing with problems), and a score of 7.5/10 for DBFM and 8.3/10 for D&C (fourth item, goal achievement). However, none of these differences are statistically significant.

Although the DBFM projects were not of a higher quality than the D&C projects, we note that, across the board, the performance of the DBFM and the D&C projects regarding quality was rather high. This was confirmed by our analysis of the interview data. Almost all interview respondents emphasized that DBFM projects resulted in an infrastructure that met high-quality standards. This is true not only for the construction phase but also for infrastructure maintenance, regarding which the respondents perceived higher quality in the case of DBFM contracts. As one respondent stated:

If you simply look at roads, you can tell if it is a DBFM project. It is better maintained, less graffiti, grass in the verge is mowed, etcetera.

4.1.4. Innovation

In , the descriptive statistics for the survey on innovation are shown. The results clearly indicated that the projects did not perform very well, with scores ranging from 3.4/10 to 7.0/10. Yet, the analysis still indicated that the differences between the DBFM projects and the D&C projects are statistically significant. On average, combining the five items (see Metselaar & Klijn, Citation2020), DBFM scored 5.9/10 and D&C scored 4.3/10 (again a statistically significant difference).

Figure 2. Analysis of innovation performance (dark bars are averages of DBFM projects, light bars are averages of D&C projects. Total N = 163, DBFM = 110, D&C = 51, DBM = 2).

In the interviews, respondents explicitly acknowledged that innovations, especially product innovations, in DBFM projects were disappointing compared to their prior expectations about DBFM. Various respondents mentioned that a lot of process innovations were developed in the last decade.

Process innovation is activated enormously by this contract form [DBFM]. This results in optimalization of working methods and ways of working. Product innovation probably has lagged behind compared to that. We had higher expectations regarding product innovations.

4.2. Drivers

4.2.1. Private financing

Looking at the role of private financiers, we found that about 90% of financing was covered by bank loans, and 10% was provided by investors, including construction companies (see Koppenjan et al., Citation2020a). The Lenders’ Technical Advisor (LTA), hired by the bank, plays an important role in advising and monitoring the SPC. Our interview respondents stated that the LTA contributed to the quality of the business case and the financial management of the projects. The presence of banks in projects increases the quality of risk management. In the Netherlands, banks have not experienced any financial problems with DBFM projects. In addition to the role of the banks, the SPC is seen as an important organizational arrangement; financial investors bring in financial and project management experience.

A drawback of bank involvement in DBFM projects mentioned by the interview respondents was that the high demands for risk management can limit flexibility and the space for innovation. Thus, the “shadow of the banks” (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020, Citation2021) has both positive effects—in terms of incentivizing on-time delivery—and negative effects—in terms of hampering innovation.

4.2.2. Performance-dependent payments

Interview respondents perceived a direct relationship between on-time delivery and the financial implications of missing milestones. If they missed out on availability payments, this had repercussions in terms of not being able to repay loans to banks and being confronted with high-interest charges. Sanctions in the event of missing milestones also had a major impact. A quote illustrates this:

Since the contract is so strictly designed, virtually everything is focused on reaching the milestones. …. If availability dates are not met, the financial consequences are gigantic.

Representatives of private consortia indicated that they found these sanctions exorbitant. Nevertheless, these sanctions contributed to the creation of strong incentives to deliver the infrastructure on-time.

Performance-dependent payments were also mentioned by respondents as an explanation for the generally low innovation rate in DBFM. The respondents explained that the strong contractual framework, and the fairly high penalties for not delivering on-time, made consortia risk-averse. Unproven techniques or technologies were usually not chosen, given the financial risks and the risk of time overruns in the projects. As a respondent from a private construction company indicated:

Because the time frame of the tender and the implementation is fairly tight …, but also because you have to steer on, let’s say, a low risk profile, and innovation is a journey of discovery, I think the time pressure actually blocks this.

At the same time, respondents mentioned that quality was sometimes traded-off against ensuring that deadlines were met. This tension between quality and time performance has also been identified in previous studies (Verweij et al., Citation2017). As far as innovation is concerned, the interview respondents indicated that the time pressure also resulted in process innovations aimed at speeding up the construction of the infrastructure and related assets.

4.2.3. Bundling

In the survey, a question was asked about the extent to which the lifecycle approach influenced the choice of materials. Unsurprisingly, the data showed that the lifecycle element was much more present in the DBFM projects than in the D&C projects: DBFM scored on average 7.4/10, against 5.0/10 for D&C, and the difference is statistically significant. The interviews confirmed this.

The integrated nature of the contract fostered both quality and innovation. The survey clearly confirmed the relation with innovation (Metselaar & Klijn, Citation2020); the regression showed a fairly strong correlation with innovation (+0.41). The relation with other performance indicators was less evident. Interview respondents attributed the better quality of the DBFM projects not only to the contract system and performance-dependent payments but also to the lifecycle approach. They also confirmed the contract’s positive impact on innovations, although, as mentioned earlier, they saw more process innovations than product innovations in DBFM projects—an outcome that they attributed to the performance-dependent payment mechanism.

4.2.4. Risk transfer

Interview respondents voiced the opinion that DBFM projects had a higher risk profile compared to projects with a D&C contract because of their size and complexity, but also because of the financial arrangements. They said that the risk transfer in the first Dutch DBFM projects was problematic: too many risks were transferred to the private partners. The competition during the tender phase had tempted construction companies to accept too many risks. As a response to the problems that occurred in these projects, more adequate risk allocations emerged. It was acknowledged that risks should be allocated to the partners that were best able to manage them. Also, public and private partners began to understand that some risks should be managed in collaboration. In the words of one respondent:

Some risks are hard to quantify and handle. They should be seen as shared risks. They should be pooled. To do so, we might create a joint risk reserve. Setbacks and windfalls could be shared according to an agreed upon distribution key. In such cases, risks can be addressed jointly.

The survey results did not show many differences in respondents’ answers concerning risk-sharing in D&C and DBFM. They did show that private respondents had a more negative view of risk-sharing than public respondents. In the survey, respondents could score between two extremes, where 1 indicated no sharing of financial risks and 10 indicated strong sharing of financial risks. The private respondents on average scored 4.2/10, whereas the public respondents scored 5.6/10. This is a relatively low score (certainly for the private respondents), and the difference is statistically significant.

The interview findings revealed that risks within the private consortium were not shared evenly. Private financiers did not experience high risks: in the event of problems, the first hits were absorbed by the construction companies in the EPC and the MTC. Only if they could not absorb the costs would the SPC be next to step in. Banks were liable only when other parties failed; their risks were small. In one of the DBFM projects that ran into problems, construction companies in the EPC were on the edge of bankruptcy, whereas the SPC was celebrating good financial results. That said, respondents acknowledged that the strict risk management by banks contributed to the quality of the business case and the management of these projects over the whole lifecycle.

4.2.5. Collaboration

The descriptive statistics for the survey on collaboration are shown in . The results showed that, generally, the DBFM projects scored higher than the D&C projects. However, the differences between the two contract types are small and statistically insignificant.

A regression analysis showed that collaboration had a positive and strong significant effect on performance (+0.63)—measured as a combined scale of the items for cost, time, and quality performance—and on innovation (+0.19) (see Metselaar & Klijn, Citation2020).

The positive impact of collaboration was also emphasized by virtually all the interview respondents. A typical quote that illustrates this is as follows:

Real relationship management achieves so much. I am not sure it is specific to DBFM projects, except that you need to work with each other for a long period. So, in DBFM projects, it is probably even more important to steer the relation actively. So not every time putting the contract first, but first discuss this together.

Interview respondents stated that, in the case of the older DBFM projects, Rijkswaterstaat took the position that private partners themselves should solve problems that they encountered during the contract implementation. Only when the success of some projects was jeopardized by the conflicts that emerged with the private consortia did this change (see also Koppenjan & De Jong, Citation2018; Verweij, Citation2015). The respondents agreed on the fact that, over time, the willingness and ability of partners to collaborate had increased:

You could say that the new generation of DBFMs is more tuned toward the need for collaboration between client and private contractor, whereas traditional DBFMs were less focused on this. …. Many more aspects can be discussed and they are dealt with in the spirit of the contract and less to the letter of the contract.

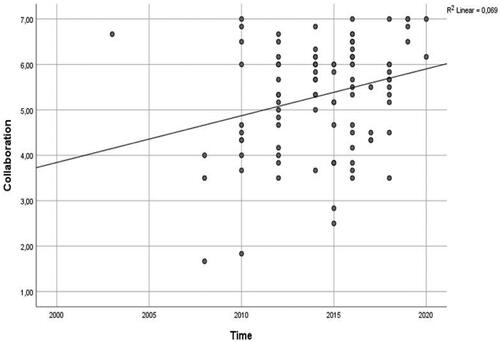

The idea that collaboration in DBFM projects increased over time was also confirmed by the survey. Plotting the starting date of the projects (contract close) with the perceptions of respondents about collaboration in the projects about which they were surveyed, we see an increase (see ). This could indicate that the impact of collaboration in more recent DBFM projects is greater than in earlier projects.

Within the private consortia, collaboration could still be improved, according to respondents. One respondent stated:

One topic is the difficult collaboration between constructors within a PPP project. The risks that emerge are carried by the constructors, but also influence the consortium as a whole.

Some respondents stated that the SPC sometimes assumed a coordinating role in DBFM projects, thus contributing to collaboration between the private partners. In addition to the disciplinary role of private financers (see section 2.1), this coordinating role of the SPC was absent in D&C projects.

4.2.6. Drivers and performance: an overview of the findings

Our findings regarding the performance of Dutch road and waterway infrastructure DBFM projects, compared to the performance of D&C projects, are mixed. The analyses showed that DBFM projects had a better time performance (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2021). Regarding cost performance, the DBFM projects had fewer additional work costs compared to D&C projects (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020, Citation2021), although their overall financial performance during the construction phase was comparable. Regarding quality performance, both DBFM projects and D&C projects performed well. The interview respondents considered the quality during the maintenance phase higher, although most Dutch DBFM projects have only recently entered this phase. Finally, regarding innovation, the analyses showed that DBFM projects performed better than D&C projects, although the level of innovation in all projects was perceived as rather low.

As far as the drivers are concerned, our study shows that private financing and performance-dependent payments affected time and cost performance. Penalties for not meeting deadlines and quality standards are costly and create a strong incentive to deliver on-time and within budget. The effect of these two drivers on quality performance is less clear. The survey did not indicate significant relationships. Some interview respondents perceived better quality performance, whereas others stated that the strong pressure to meet deadlines came at the expense of quality. The performance-dependent payment mechanism was seen as a driver of process innovation, and, although this is not unique to DBFM, the private financing arrangements strengthened the impact of the performance-dependent payment mechanism. At the same time, there are indications that the mechanism hampered innovation.

Regarding risk transfer, we did not find clear effects in the survey data. Respondents stated that too many risks were transferred, and they reported a higher risk profile for DBFM projects.

We found no clear evidence that bundling and lifecycle optimization resulted in a better cost or quality performance. Although respondents considered the quality of DBFM projects better, we argue that this finding is premature, as most Dutch DBFM projects have only recently entered their maintenance phases (see Koppenjan et al., Citation2020a). DBFM contracts resulted in more innovation compared to D&C projects, although not as high as respondents expected from DBFM. Process innovations were to a large extent attributable to bundling and lifecycle optimization next to the performance-dependent payment mechanism.

Collaboration is clearly a powerful driver of good performance for both DBFM and D&C projects. Although our Dutch DBFM projects scored slightly better than D&C projects, the differences are statistically insignificant. Respondents agreed on the importance of collaboration for achieving good results. Interestingly, over time, collaboration appeared to have increased in DBFM projects; this indicates learning.

5. Conclusion and discussion

Our study confirms the assumptions under the contractual perspective in the PPP literature regarding the impact of private financing and performance-dependent payments on time performance and cost performance. This matches other studies’ results—such as Atmo et al. (Citation2017), Oliveira dos Reis and Cabral (Citation2017), Rodrigues and Zucco (Citation2018), and Verweij and Van Meerkerk (Citation2021)—adding credence to the claim that PPPs have a “solid record of on-time delivery” (Lewis, Citation2021, p. 70). Our study also confirms that PPPs perform better in terms of fewer additional work costs (Oliveira dos Reis & Cabral, Citation2017; Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020, Citation2021; Whittington, Citation2012). Our study also confirms the assumption about the negative impact of private financing on innovation (Hueskes, Citation2019). The strong incentive to deliver on-time does, however, appear to enhance process innovation. Our study could not confirm the expected positive impact of performance-dependent payments on a quality, although these impacts may become manifest in the coming years during the maintenance phases of the DBFM projects. There is a dearth of studies on the quality performance of PPPs compared to that of traditional types of public procurement (see Verweij et al., forthcoming), and the present article underscores the need for more studies on this, echoing the call by Petersen (Citation2019). The effect of the lifecycle approach consequent to the integrated nature of the contract (bundling) on innovation is acknowledged and also on quality, although this latter effect is less certain, given that the majority of Dutch DBFM contracts in road and waterway infrastructure projects only recently entered the maintenance phase. The collaboration proved to be a strong driver of performance and innovation; this is in line with previous research (e.g., Casady et al., Citation2019; Edelenbos & Klijn, Citation2009; Hueskes et al., Citation2019; Kort & Klijn, Citation2011; Ni, Citation2012; Warsen et al., Citation2018; Weihe, Citation2009; Zheng et al., Citation2018). However, in contrast to expectations, collaboration was not stronger in DBFM projects compared to D&C projects.

Overall, we can conclude that—despite some mixed and inconclusive findings—the DBFM projects (PPPs) did not perform worse than the D&C projects. This is an important conclusion in itself, even more so because the DBFM projects that we studied were generally larger and more complex than the D&C projects. In that sense, our study contributes to a more realistic view of PPP performance: although the DBFM projects may not have realized the high expectations attached to PPP in government rhetoric, in general, their performance proved rather adequate.

Our findings are also important in that they show that PPP performance is not static and that the performance of the DBFM projects improved over time as public and private partners learned to arrive at a better risk allocation and improved collaboration, as has also been found by other authors (Casady et al., Citation2019; Siemiatycki, Citation2015; Wang & Zhao, Citation2018). During the 15 years in which DBFM was used, partners learned to better manage the contract and that collaboration and flexibility are needed to make the contract work. From a theoretical point of view, this implies, in accordance with historical institutionalism (Lowndes & Roberts, Citation2013), that it is not the contract that determines performance, but the actors that enact the contract and the practices that they develop (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016). Theoretically, this means not only that explanations of PPP performance based on institutional economics are moderated by the sociological institutionalism-inspired collaborative perspective, but also that historical institutionalism is part of the equation. From a practical point of view, this implies that choosing a contract that is based purely on its presumed added value is problematic because that performance cannot be taken for granted and comes about only gradually (Koppenjan & De Jong, Citation2018; Willems et al., Citation2017). Actors learn to manage contracts over time.

Our study shows that managing DBFM contracts is demanding and not straightforward. To achieve strong time and cost performance, private financing and incentives, such as performance-dependent payments are effective (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2021); but these same incentives hamper product innovation and may squeeze quality. They may also inhibit flexible reactions to new circumstances and unexpected problems, and therefore collaboration is particularly important (Demirel et al., Citation2017; Verweij et al., Citation2017). In that sense, the performance of DBFM contracts may depend on the mixed use of drivers (Benítez-Ávila et al., Citation2018; Warsen et al., Citation2019).

A strength of the present evaluation is that it used different data collection and analysis methods, enabling a more holistic view of PPP performance. The comparison with D&C proved a useful benchmark against which the performance of DBFM could be assessed (see Petersen, Citation2019). Furthermore, the perceptions of private parties were included, whereas many PPP evaluations focus on the public perspective.

At the same time, naturally, the study is subject to limitations requiring further research. First, the data from the Rijkswaterstaat Project Database—as all data used in this study—are limited in that they generally do not concern the whole lifecycle of the projects, i.e., up to and including the full maintenance phase. The reason for this is simply that the DBFM projects in the Netherlands have not yet reached the end of their lifecycle (see Koppenjan et al., Citation2020a). Thus, ultimately, the question of whether private financing is in the end more cost-effective than public financing of infrastructure projects remains unanswered (compare Petersen, Citation2019; Silvestre & de Araújo, Citation2012; Siemiatycki, Citation2015). Second, the cost performance data concern mainly public records. We ascertained from the survey and the interviews that private respondents were less satisfied with the risk allocation and with the financial pressures experienced. To corroborate these perceptions and experiences, future studies should undertake systematic analyses of cost performance data from private consortia. Thirdly, this study focused on road and waterway infrastructure, and whether its results and conclusions also apply to other economic infrastructures (e.g., energy) or social infrastructure (e.g., courts, schools, prisons) needs to be tested in new evaluations (Verweij et al., forthcoming). Finally, this study presented findings regarding the Dutch DBFM practice. Although we have put these findings in the perspective of international literature and experiences elsewhere, the question regarding the generalizability of these findings remains. Therefore, similar studies in other countries, as well as international comparative research, are needed to further strengthen our knowledge of PPP performance and the influence of the contextual conditions underlying this performance.

Acknowledgments

The evaluation presented in this article was commissioned by Rijkswaterstaat—the executive agency of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management—and Bouwend Nederland—the Dutch association of construction and infrastructure companies.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joop Koppenjan

Prof. Dr. Joop Koppenjan is professor of Public Administration at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. His research focuses on complex decision making, governance networks, public private partnerships and public management.

Erik-Hans Klijn

Prof. Dr. Erik Hans Klijn is professor of Public Administration at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. His research is about complex decision making in networks, branding and media influence.

Stefan Verweij

Dr. Stefan Verweij is Assistant Professor in Infrastructure Planning, Governance & Methodology at the University of Groningen. His research focusses on collaboration in cross-sector governance networks, with a particular focus on Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in infrastructure planning. He is also specialized in comparative methods, in particular Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA).

Mike Duijn

Dr. Michael Duijn is senior academic researcher Public Administration at the Erasmus university Rotterdam and senior managing researcher at GovernEUR, an academic incubator. His research focuses on (inter-)organizational learning, policy evaluation, and participatory policy processes in the areas of mobility, spatial planning, energy, water and soil management, and climate adaptation.

Ingmar van Meerkerk

Dr. Ingmar van Meerkerk is Associate Professor at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology at Erasmus University Rotterdam. His research is focused on boundary spanning, trust, innovation, democratic legitimacy and performance of interactive forms of governance such as public-private partnerships and community-based initiatives.

Samantha Metselaar

Samantha Metselaar is a PhD researcher at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology of the Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Her research interests include time/spatial flexibility and its consequences for employee well-being and performance. She is also involved in PPP research.

Rianne Warsen

Dr. Rianne Warsen is assistant professor Public Management at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology of the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Her research interests include public-private partnerships, contracting in the public sector, and (network) governance.

References

- Albalate, D., & Bel-Piñana, P. (2019). The effects of public private partnerships on road safety outcomes. Accident; Analysis and Prevention, 128, 53–64.

- Atmo, G. U., Duffield, C. F., Zhang, L., & Wilson, D. I. (2017). Comparative performance of PPPs and traditional procurement projects in Indonesia. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 30(2), 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-02-2016-0047

- Barretta, A., Busco, C., & Ruggiero, P. (2008). Trust in project financing: An Italian health care example. Public Money and Management, 28(3), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2008.00641.x

- Benítez-Ávila, C., Hartmann, A., Dewulf, G. P. M. R., & Henseler, J. (2018). Interplay of relational and contractual governance in public-private partnerships: The mediating role of relational norms, trust and partners’ contribution. International Journal of Project Management, 36(3), 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.12.005

- Boers, I., Hoek, F., Van Montfort, C., & Wieles, J. (2013). Public–private partnerships: International audit findings. In P. De Vries & E. B. Yehoue (Eds.), The Routledge companion to public-private partnerships (pp. 451–478). Routledge.

- Brown, T. L., Potoski, M., & Van Slyke, D. M. (2016). Managing complex contracts: A theoretical approach. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv004

- Casady, C., Flannery, D., Geddes, R. R., Palcic, D., & Reeves, E. (2019). Understanding PPP tendering periods in Canada: A duration analysis. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(6), 1259–1278. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1597739

- Chen, Z., Daito, N., & Gifford, J. L. (2016). Data review of transportation infrastructure public-private partnership: A meta-analysis. Transport Reviews, 36(2), 228–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1076535

- Culp, G. (2011). Alternative project delivery methods for water and wastewater projects: Do they save time and money? Leadership and Management in Engineering, 11(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LM.1943-5630.0000133

- Daito, N., & Gifford, J. L. (2014). U.S. highway public private partnerships: Are they more expensive or efficient than the traditional model? Managerial Finance, 40(11), 1131–1151. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-03-2014-0072

- Deakin, S., & Michie, J. (Eds.). (1997). Contract, co-operation, and competition: Studies in economics, management, and law. Oxford University Press.

- Demirag, I., Khadaroo, I., Stapleton, P., & Stevenson, C. (2011). Risks and the financing of PPP: Perspectives from the financiers. The British Accounting Review, 43(4), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2011.08.006

- Demirel, H. Ç., Leendertse, W., Volker, L., & Hertogh, M. J. C. M. (2017). Flexibility in PPP contracts—Dealing with potential change in the pre-contract phase of a construction project. Construction Management and Economics, 35(4), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2016.1241414

- Edelenbos, J., & Klijn, E. H. (2009). Project versus process management in public-private partnership: Relation between management style and outcomes. International Public Management Journal, 12(3), 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490903094350

- European PPP Expertise Centre (2015). PPP motivations and challenges for the public sector: Why (not) and how. European Investment Bank.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2009). Survival of the unfittest: Why the worst infrastructure gets built – And what we can do about it. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 25(3), 344–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grp024

- Froud, J., & Shaoul, J. (2001). Appraising and evaluating PFI for NHS hospitals. Financial Accountability and Management, 17(3), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0408.00130

- Ghobadian, A., O’Regan, N., Gallear, D., & Viney, H. (2004). Private-public partnerships: Policy and experience. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grimsey, D., & Lewis, M. K. (2005). Are public private partnerships value for money?: Evaluating alternative approaches and comparing academic and practitioner views. Accounting Forum, 29(4), 345–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2005.01.001

- Hodge, G. A. (2010). Reviewing public-private partnerships: Some thoughts on evaluation. In G. A. Hodge, C. Greve, & A. E. Boardman (Eds.), International handbook on public-private partnerships (pp. 81–112). Edward Elgar.

- Hodge, G. A., & Greve, C. (2017). On public-private partnership performance: A contemporary review. Public Works Management & Policy, 22(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X16657830

- Hong, S. (2016). When does a public-private partnership (PPP) lead to inefficient cost management? Evidence from South Korea’s urban rail system. Public Money & Management, 36(6), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1206755

- Hueskes, M. (2019). Beyond the rhetoric of strategic public procurement: A study on innovation and sustainability in public-private partnerships [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Antwerp.

- Hueskes, M., Koppenjan, J. F. M., & Verweij, S. (2019). Public-private partnerships for infrastructure: Lessons learned from Dutch and Flemish PhD-theses. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 19(3), 160–176.

- Hussain, S., & Siemiatycki, M. (2018). Rethinking the role of private capital in infrastructure PPPs: The experience of Ontario. Public Management Review, 20(8), 1122–1144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1428412

- Huxham, C., & Vangen, S. (2005). Managing to collaborate: The theory and practice of collaborative advantage. Routledge.

- Jeffares, S., Sullivan, H., & Bovaird, T. (2013). Beyond the contract: The challenge of evaluating the performance(s) of public-private partnerships. In C. Greve & G. A. Hodge (Eds.), Rethinking public-private partnerships: Strategies for turbulent times (pp. 166–187). Routledge.

- Jensen, M., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs, and capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2016). The impact of contract characteristics on the performance of public–private partnerships (PPPs). Public Money & Management, 36(6), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1206756

- Klijn, E. H., Steijn, B., & Edelenbos, J. (2010). The impact of network management on outcomes in governance networks. Public Administration, 88(4), 1063–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01826.x

- Koenen, I. (2016). Bahamamodel nekt bouwers A15 MaVa. Cobouw.

- Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2008). Public-private partnership and mega-projects. In B. Flyvbjerg, H. Priemus, & B. van Wee (Eds.), Development and management of large infrastructure projects (pp. 189–199). Edward Elgar.

- Koppenjan, J. F. M., & De Jong, M. (2018). The introduction of public–private partnerships in the Netherlands as a case of institutional bricolage: The evolution of an Anglo-Saxon transplant in a Rhineland context. Public Administration, 96(1), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12360

- Koppenjan, J. F. M., Klijn, E. H., Duijn, M., Klaassen, H. L., Van Meerkerk, I. F., Metselaar, S. A., Warsen, R., & Verweij, S. (2020a). Leren van 15 jaar DBFM-projecten bij RWS: Eindrapport. Rijkswaterstaat en Bouwend Nederland.

- Koppenjan, J. F. M., Klijn, E. H., Duijn, M., Klaassen, H. L., Van Meerkerk, I. F., Metselaar, S. A., Warsen, R., & Verweij, S. (2020b). Leren van 15 jaar DBFM-projecten bij RWS: Interviewrapportage. Rijkswaterstaat en Bouwend Nederland.

- Kort, M., & Klijn, E. H. (2011). Public–private partnerships in urban regeneration projects: Organizational form or managerial capacity? Public Administration Review, 71(4), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02393.x

- Lenferink, S. (2013). Market involvement throughout the planning lifecycle: Public and private experiences with evolving approaches integrating the road infrastructure planning process [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Groningen.

- Lenferink, S., Tillema, T., & Arts, J. (2013). Towards sustainable infrastructure development through integrated contracts: Experiences with inclusiveness in Dutch infrastructure projects. International Journal of Project Management, 31(4), 615–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.09.014

- Lewis, M. K. (2021). Rethinking public private partnerships. Edward Elgar.

- Lowndes, V., & Roberts, M. (2013). Why institutions matter: The new institutionalism in political science. Palgrave Macmillan.

- McQuaid, R. W., & Scherrer, W. (2010). Changing reasons for public-private partnerships (PPPs). Public Money & Management, 30(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540960903492331

- Meduri, S. S., & Annamalai, T. R. (2013). Unit costs of public and PPP road projects: Evidence from India. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 139(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000546

- Metselaar, S. A., & Klijn, E. H. (2020). Leren van 15 jaar DBFM-projecten bij RWS: Respondentenverslag survey. Rijkswaterstaat en Bouwend Nederland.

- Ministerie van Financiën (2013). Handleiding publiek-private comparator. Ministerie van Financiën.

- Nederhand, J., & Klijn, E. H. (2019). Stakeholder involvement in public-private partnerships: Its influence on the innovative character of projects and on project performance. Administration & Society, 51(8), 1200–1226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716684887

- Ni, A. Y. (2012). The risk-averting game of transport public-private partnership: Lessons from the adventure of California's state route 91 express lanes. Public Performance & Management Review, 36(2), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576360205

- Nooteboom, B. (2002). Trust: Forms, foundations, functions, failures and figures. Edward Elgar.

- Oliveira dos Reis, C. J., & Cabral, S. (2017). Public-private partnerships (PPP) in mega-sport events: A comparative study of the provision of sports arenas for the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Public Administration, 51(4), 551–579.

- Palcic, D., Reeves, E., & Siemiatycki, M. (2019). Performance: The missing ‘P’ in PPP research? Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 90(2), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12245

- Parker, D., & Hartley, K. (2003). Transaction costs, relational contracting and public private partnerships: A case study of UK defence. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 9(3), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-7012(02)00035-7

- Petersen, O. H. (2019). Evaluating the costs, quality, and value for money of infrastructure public‐private partnerships: A systematic literature review. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 90(2), 227–244.

- Pollock, A. M., Price, D., & Player, S. (2007). An examination of the UK Treasury’s evidence base for cost and time overrun data in UK value-for-money policy and appraisal. Public Money and Management, 27(2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2007.00568.x

- Poppo, L., & Zenger, T. (2002). Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strategic Management Journal, 23(8), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.249

- Raisbeck, P., Duffield, C. F., & Xu, M. (2010). Comparative performance of PPPs and traditional procurement in Australia. Construction Management and Economics, 28(4), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190903582731

- Reeves, E. (2008). The practice of contracting in public-private partnerships: Transaction costs and relational contracting in the Irish schools sector. Public Administration, 86(4), 969–986. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00743.x

- Reeves, E., & Ryan, J. (2007). Piloting public-private partnerships: Expensive lessons from Ireland’s schools’ sector. Public Money and Management, 27(5), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2007.00604.x

- Reynaers, A. (2014). It takes two to tangle: Public-private partnerships and their impact on public values [Doctoral dissertation]. VU University Amsterdam.

- Rijkswaterstaat. (2011). Ondernemingsplan 2015: Eén Rijkswaterstaat, elke dag beter!. Rijkswaterstaat.

- Rodrigues, B., & Zucco, C. (2018). A direct comparison of the performance of public-private partnerships with that of traditional contracting. Brazilian Journal of Public Administration, 52(6), 1237–1257.

- Shi, J., Duan, K., Wu, G., Zhang, R., & Feng, X. (2020). Comprehensive metrological and content analysis of the public–private partnerships (PPPs) research field: A new bibliometric journey. Scientometrics, 124(3), 2145–2184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03607-1

- Silvestre, H. C., & de Araújo, J. F. F. E. (2012). Public-private partnerships/private finance initiatives in Portugal: Theory, practice, and results. Public Performance & Management Review, 36(2), 316–339. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576360208

- Siemiatycki, M. (2015). Public‐private partnerships in Canada: Reflections on twenty years of practice. Canadian Public Administration, 58(3), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12119

- Smyth, H., & Edkins, A. (2007). Relationship management in the management of PFI/PPP projects in the UK. International Journal of Project Management, 25(3), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2006.08.003

- Steijn, B., Klijn, E. H., & Edelenbos, J. (2011). Public private partnerships: Added value by organizational form or management? Public Administration, 89(4), 1235–1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01877.x

- Verweij, S. (2015). Achieving satisfaction when implementing PPP transportation infrastructure projects: A qualitative comparative analysis of the A15 highway DBFM project. International Journal of Project Management, 33(1), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.05.004

- Verweij, S., Teisman, G. R., & Gerrits, L. M. (2017). Implementing public-private partnerships: How management responses to events produce (un)satisfactory outcomes. Public Works Management & Policy, 22(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X16672949

- Verweij, S., & Van Meerkerk, I. F. (2020). Do public-private partnerships perform better? A comparative analysis of costs for additional work and reasons for contract changes in Dutch transport infrastructure projects. Transport Policy, 99, 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.09.012

- Verweij, S., & Van Meerkerk, I. F. (2021). Do public-private partnerships achieve better time and cost performance than regular contracts? Public Money & Management, 41(4), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1752011

- Verweij, S., Van Meerkerk, I. F., & Klaassen, H. L. (2020). De performance van DBFM bij Rijkswaterstaat: Een kwantitatieve analyse van projectendata. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen en Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam.

- Verweij, S., Van Meerkerk, I. F., & Korthagen, I. A. (2015). Reasons for contract changes in implementing Dutch transportation infrastructure projects: An empirical exploration. Transport Policy, 37, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.11.004

- Wang, Y., & Zhao, Z. J. (2018). Performance of public–private partnerships and the influence of contractual arrangements. Public Performance & Management Review, 41(1), 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2017.1400989

- Wang, H., Xiong, W., Wu, G., & Zhu, D. (2018). Public–private partnership in public administration discipline: A literature review. Public Management Review, 20(2), 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1313445

- Warsen, R., Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2019). Mix and match: How contractual and relational conditions are combined in successful public–private partnerships. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(3), 375–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy082

- Warsen, R., Nederhand, J., Klijn, E. H., Grotenbreg, S., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2018). What makes public-private partnerships work? Survey research into the outcomes and the quality of cooperation in PPPs. Public Management Review, 20(8), 1165–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1428415

- Weihe, G. (2009). Public-private partnerships: Meaning and practice [Doctoral dissertation]. Copenhagen Business School. PhD Series No. 2.2009.

- Whittington, J. (2012). When to partner for public infrastructure? Transaction cost evaluation of design-build delivery. Journal of the American Planning Association, 78(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2012.715510

- Willems, T., Verhoest, K., Voets, J., Coppens, T., Van Dooren, W., & Van den Hurk, M. (2017). Ten lessons from ten years PPP experience in Belgium. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 76(3), 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12207

- Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. The Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2), 233–261. https://doi.org/10.1086/466942

- Williamson, O. E. (1996). The mechanisms of governance. Oxford University Press.

- Yescombe, E. R. (2007). Public-private partnerships: Principles of policy and finance. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Zheng, X., Yuan, J., Guo, J., Skibniewski, M. J., & Zhao, S. (2018). Influence of relational norms on user interests in PPP projects: Mediating effect of project performance. Sustainability, 10(6), 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062027