Abstract

In the public context, it is crucial to know how a motivating work environment can inspire employees to engage in collective problem solving. This study examines whether working in autonomous primary healthcare teams offers such a motivating work environment that enhances individual vitality and team innovations. A 2-1-2 multilevel mediation analysis was conducted on multi-sourced survey data from 767 employees and 59 supervisors in 78 primary healthcare teams. The results show that greater team autonomy makes individual employees feel more vital, which, in turn, leads to more innovations being developed by the team. These findings thereby emphasize the importance of the relatively underexposed “psychological perspective” in the public administration literature.

Introduction

Policy makers and scholars in the field of public administration are grown aware of the relevance to spur public innovation and enhance employee well-being (Borst et al., Citation2020). To achieve these objectives, an increasing number of public organizations have shown interest in decentralizing the organizational structure (Lee & Edmondson, Citation2017). A prominent example of a decentralized organizational form that is accordingly becoming more popular is the (semi-) autonomous team, which consists of team members sharing the decision-making and diffusing the responsibilities (Kalliola, Citation2003; Uhl-bien & Graen, Citation1998). In public organizations, which are typically characterized by a high number of hierarchical levels, the use of (semi-) autonomous teams implies that the decision-making power needs to be delegated to the team level (Jiang & Chen, Citation2018). A main benefit of (semi-) autonomous teams in public organizations is therefore that it brings the decision-making power closer to the citizens, for which public services can be adapted more adequately to local circumstances (Wynen et al., Citation2014). Moreover, the shared opportunity and responsibility characterizing the (semi-) autonomous teams pushes public employees to engage in collective problem solving, fostering innovations developed and implemented by the team (Jiang & Chen, Citation2018). In this way, the use of (semi-) autonomous teams has become well known as a suitable approach to enhance public innovations (Lee & Edmondson, Citation2017).

In addition, from a job design perspective, team autonomy is also known as a strategic approach to create a motivating work environment for improved quality of work-life (Kalliola, Citation2003; Van Mierlo et al., Citation2007). Scholars explain that working in (semi-) autonomous teams comes with greater opportunities for employees to act in accordance with their deeply held values, goals, and interests, which play a key role in peoples general well-being (Alper et al., Citation1998). Accordingly, previous research shows that high autonomy, collaboration with colleagues and shared decision-making, which are the main characteristics of (semi-) autonomous teams, makes public employees feel more vital (Tummers et al., Citation2015). This vitality refers to the conscious and subjective feeling of psychological and physical well-being, expressed in positive energy that one feels as available to oneself so that one can function fully (Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997). Working in (semi-) autonomous teams in public organizations as such improves the work experience of public employees by generating a sense of “aliveness” and positive experience to have energy for themselves (Bauwens et al., Citation2021; Tummers et al., Citation2018).

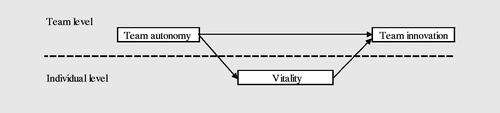

The benefit of using (semi-) autonomous teams in public organizations thus lies in the opportunity that more new ideas are generated and implemented through teamwork, as well as in its potential to enhance individual vitality. Related to this, there is literature showing that the positive mindset that comes with vitality makes people think more flexibly, pay more attention to external factors, and are more willing to participate in teamwork (e.g., Mitchell & Boyle, Citation2019; Walter & van der Vegt, Citation2013). As individual vitality has been found to be a significant predictor of employee behavior in a team context (Bauwens et al., Citation2021), this study specifically suggests that the positive relationship between team autonomy and team innovation develops through the enhanced individual vitality, which is a central argument to this study. The central research question of this study is therefore as follows: “To what extent does team autonomy influence team innovation through individual employee vitality in the public context?”

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. Its first contribution is to the research on the psychological perspective in public administration literature. Understanding psychological processes driving the behavior of public employees is seen as an important topic for academics and policymakers in public administration (Bauwens et al., Citation2021). In fact, there is growing awareness that employee well-being has a significant influence on the outcomes of public organizations (Borst et al., Citation2020). As a result, there has been specifically called for more research on the eudaimonic dimension of well-being, which, unlike the hedonic dimension, relates to an active state of being and is therefore strongly related to behavior (e.g., Bauwens et al., Citation2021; Borst et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). Considering that individual vitality is an important indicator of eudaimonic well-being, it can be concluded that the vitality of public sector employees can’t be ignored (Tummers et al., Citation2018)

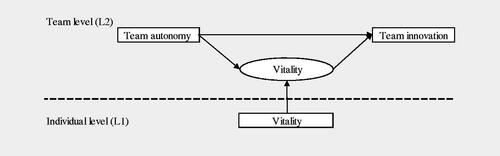

The second contribution of this study is to the public administration literature on innovation. Scholars in the field of public administration have largely overlooked the fact that new ideas are usually developed and implemented by teams. Scholars in the field of general management, on the other hand, point out that future theoretical efforts on team innovation need to focus on how the innovation process develops across different levels of analysis, including the team level (Anderson et al., Citation2014; Van der Voet & Steijn, Citation2021). By studying, through a so-called 2-1-2 multilevel design, whether team innovation in the public sector results from individual employees working in (semi-) autonomous teams, this study thus makes a unique contribution, since very few studies on innovations have adopted a research design that recognizes the cross-level process of innovation so far (Anderson et al., Citation2014). As such, this multilevel approach provides an in-depth insight into the role of individuals in (semi-) autonomous teams, who are ultimately responsible for the team innovations (Meijer, Citation2014).

Finally, a third contribution of this study is to the public administration literature on “post-bureaucratic” organizations (Wynen et al., Citation2014). The (semi-) autonomous team is a prominent example of post-bureaucratic organization forms, yet it seems that teams are still a blind spot in the public administration literature so far (Van der Voet & Steijn, Citation2021). A major objective of this study is therefore to focus attention on teams by empirically examining the influence of (semi-) autonomous teams for public innovation and employee well-being in a public sector context.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, the theoretical framework describes how the relationship between team autonomy and team innovation can be explained through the individual employees’ vitality. Next, the data and methods used to test the conceptual model are described. After this, the results are presented, and conclusions drawn and discussed.

Theoretical framework

Team autonomy to spur innovation and vitality in the public sector

Policy makers and scientists in the field of public administration are increasingly aware of the need to stimulate public innovation, leading to an increasing interest in (semi-) autonomous teams in which employees share decision-making and responsibilities (Borst et al., Citation2020). In public organizations, the use of autonomous teams is also a structural approach to bring decision-making closer to the citizens and inspire a bottom-up flow of information (Jakobsen & Thrane, Citation2016). Characteristic to (semi-) autonomous teams is therefore the greater opportunity and responsibility for employees to improve performances and adapt to changing circumstances (Hoegl & Parboteeah, Citation2006). This suggests that, when working in (semi-) autonomous teams, employees are stimulated to gain new perspectives, introduce ideas and generate innovative solutions for new and improved ways of working (Jiang & Chen, Citation2018; West, Citation2003). As employees have the discretion to decide through trial and error, they will be stimulated to experiment with innovative ways of working more often (Yeh & Walter, Citation2016). Since the changes come from the employees themselves, they also tend to be highly motivated to overcome resistance to change and to solve unforeseen problems that are innate to the process of implementing innovation (Anderson et al., Citation2014). Moreover, as the societal problems that require public innovations transcend individual expertise, working in (semi-) autonomous teams stimulates team innovations rather than individual innovations in the public sector (Jakobsen & Thrane, Citation2016; Bekkers et al., Citation2013). A key element of (semi-) autonomous teams in the public context is thus particularly in its great potential for team innovation, which can be any new element in a public service that amounts to a discontinuity with the previous situation and is created by the team (Osborne & Brown, Citation2012). Based on these arguments, the first hypothesis for this research is:

Hypothesis 1:

Team autonomy is positively related to team innovation.

Individual vitality as a mediator in the relationship between team autonomy and team innovation

To get a more in-depth understanding of the dynamics underlying the relationship between team autonomy and team innovation, this study builds on the overarching input-mediator-output-input (IMOI) model by Ilgen et al. (Citation2005). This framework emphasizes that the relationship between a team’s characteristics (i.e., inputs) and a team’s results (i.e., outputs) evolves through the affective, behavioral and cognitive states that occur while team members work together (i.e., mediators). This reasoning as such emphasizes the active role of the employees in creating team dynamics (Ilgen et al., Citation2005).

Having said that, from previous studies among public organizations, it appears that working in (semi-) autonomous teams generates positive and active feelings among team members (van Mierlo et al., Citation2007). Other studies in the field of public administration also show that the high autonomy, participation in shared decision-making and high-quality teamwork, which are characteristic of (semi-) autonomous teams, are important work characteristics of a motivating work environment in which employees can feel more vital (Borst et al., Citation2019; Lahat & Ofek, Citation2022; Tummers et al., Citation2015). This feeling of vitality is an important indicator of well-being, as it refers to the general sense of “aliveness” and positive experience of having energy available to oneself (Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997). Employees who feel vital therefore experience a positive energy that makes them feel mentally and physically strong (Ryan et al., Citation1999; Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997).

An explanation of why working in (semi-) autonomous teams enhances feelings of vitality can be found in the self-determination theory (SDT), which states that individuals have an integrative tendency to enhance feelings of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2002). When the social contextual factors allow one to experiences themselves as the “origin” of the actions that lead to the satisfaction of these basic needs, this is associated with a greater sense of vitality (Ryan & Deci, Citation2002). This means that, since working in (semi-) autonomous teams involves joint problem solving, the individual team members reinforce their personal strengths and act on their deep values, goals, and interests, leaving them feeling positive and energized (Borst, Citation2018; Dackert, Citation2016; Walter & van der Vegt, Citation2013). Furthermore, the high-quality connection that emerges between employees when sharing decision-making is known to reinforce this vital and energized feeling even further (Atwater & Carmeli, Citation2009).

Working in a more autonomous team thus comes with the potential to make employees feel more vital and, vice versa, working in a less autonomous team decreases the individual vitality. It should be noted that feeling vital is in essence an individual subjective experience, which means that the strength of the positive influence of team autonomy on individual vitality can differ for each person and across contexts (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000, p. 232). The positive relationship between team autonomy and vitality therefore crosses the level of analysis, leading to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

Team autonomy is positively related to individual vitality.

Following the reasoning of the IMOI model, this greater vitality in (semi-) autonomous teams could subsequently explain the positive relationship between team autonomy and team innovation (Ilgen et al., Citation2005). While vitality is a positive outcome in itself, recent studies in public administration show that feeling dedicated and energized also predict behavioral and attitudinal outcomes (Borst et al., Citation2020). This influence of vitality is explained by the idea that feeling vital is a reinforcing experience, which means that vital people tend to invest their energy in activities that reinforce their positive vigor, creating a positive spiral in which they become more open-minded and approach potential challenges more positively (Kark & Carmeli, Citation2009). Moreover, when people feel vital, they benefit from cognitive flexibility and rich knowledge structures, and are motivated to engage in in-depth exploration, which helps them cope with change (Bauwens et al., Citation2021; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Vital people furthermore remain resilient to challenges that arise during the realization of change as they have a strong perseverance (Bauwens et al., Citation2021; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017).

Specifically in the public context, the societal challenges require employees to integrate their expertise and engage in collective problem solving (Van der Voet & Steijn, Citation2021), meaning that individual vitality stimulates and enables employees to share and develop new ideas through teamwork (Rangus & Slavec, Citation2017). Having said that, it is important to realize that the focus on the individual employee in this reasoning goes beyond the role of the “creative genius,” and the role of individuals has become rather distributed with a focus on the collaboration (Meijer, Citation2014). With this notion it can thus be concluded from previous studies that greater individual vitality will generate more team innovation. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3:

Individual vitality is positively related to team innovation.

Combining the rationale of the IMOI model, as an overarching theoretical framework to address the dynamics of teams, with the SDT to understand the behavior and attitudes of individuals in teams, it can thus be concluded that individual vitality mediates the relationship between team autonomy and team innovation in public organizations. In other words, team autonomy has a positive relationship with team innovation because it creates a motivating work environment that encourages positive and active feelings of vitality in individual employees, which in turn enables them to develop successful team innovations. This comes together in the following final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4:

Individual vitality mediates the positive relationship between team autonomy and team innovation.

See for the visual representation of this relationship.

Method

Sampling

To test the hypotheses and examine the conceptual model, survey data were collected from supervisors and professionals working in Dutch primary healthcare teams. These teams were formed following a decentralization process in which public responsibility for social welfare was delegated from the national government to municipalities in 2015 (Dijkhoff, Citation2014). A key feature of the Dutch primary healthcare teams is that they consist of a range of professionals who jointly bear responsibility for all primary and social care in a specific neighborhood. An important assumption underlying this way of organizing is that the shared responsibility between the various professionals will stimulate them to find tailor-made solutions for the complex social issues they face on a daily basis (van Zijl et al., Citation2019). The hypothesized positive relationship between the autonomy of the teams and their innovations in the implementation of new procedures or services, is therefore highly prevalent in the context of Dutch primary healthcare teams (Van Zijl et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the scope in the regulations provided to the municipalities, results in enough variations in autonomy and innovation across teams, making these teams appropriate to examine the hypotheses.

Based on convenience sampling, the two largest municipalities and the largest partnership of municipalities were invited to participate in this study. The 1822 professionals and 61 supervisors working in these municipalities received an online questionnaire between June 2018 and July 2019. In total, 831 professionals (response rate of 46%) and 59 supervisors (response rate of 97%) completed the online survey, with 20 supervisors leading multiple teams. Teams where the supervisor and at least 30% of the team members had completed the survey were included in the subsequent analyses to ensure that the team data were sufficiently representative. This filter resulted in the exclusion of ten teams, with the eligible dataset including 767 professionals and 58 supervisors working in 78 teams. The respondents’ characteristics are reported in Table A1 of the Online Appendix, showing that the majority of the professionals were female (89%) with an average age of 42 years, and 74% having completed higher vocational education. On average, the professionals had worked in their team for 28 months when completing the survey, and had a contract for 29 hours a week, which is close to the average of 30 working hours a week in the Dutch working population (CBS, StatLine 2020). Most of the supervisors were also female (76%), with an average age of 46 years, and the majority (78%) having completed higher professional education. A large majority of the supervisors (85%) had previously worked as public healthcare professionals themselves, and most (64%) have also previously held other supervisory positions. The overrepresentation of women in the sample is representative of the workforce in the social domain in the Netherlands, where 79% of employees are female (CBS, StatLine 2020).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

Data analysis

The variables of interest in this study were operationalized and measured on both the individual and the team levels, with the individual data being nested within teams. As such, this study adopts a multilevel technique known as 2-1-2 multilevel mediation (Krull & Mackinnon, Citation2001). This means that the independent variable (team autonomy) and the dependent variable (team innovation) are measured on the higher level 2 (the team level), while the mediating variable (individual vitality) is measured on the lower level 1 (the individual level) as shown in . This approach separates the within- and the between-group constructs in a way that the overall relationship can be formulated in a multilevel structural equation model (MSEM) as recommended by Preacher et al. (Citation2011).

The MSEM is analyzed following a two-step approach where, first, the measurement model is examined to test the factor structure, and second, the structural model is examined to test the proposed relationships (Silva et al., Citation2019). Ideally, both the measurement and the structural models would contain all the individual items as indicators of the latent variable. However, since this would require a sample size larger than 78 teams for the structural model to provide sufficient statistical power, the structural model adopted includes the latent variables as a single indicator (Silva et al., Citation2019). In addition, because the level-2 sample size is below 100, the model fit of the measurement model is assessed using only the the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual Within (SRMRW) as recommended by Padgett and Morgan (Citation2021). The data were analyzed in Mplus version 8.3 and the MSEM was evaluated with a Robust Maximum Likelihood estimation method to ensure the model’s chi square and standard errors were corrected for non-normality (Brown, Citation2015; Rhemtulla et al., Citation2012).

Measurement

Team autonomy was measured through four items in the survey for professionals that were based on Campion et al.’s (Citation1996) measurement scale for self-management. An example item being “In my team, we allocate the tasks ourselves.” The professionals could respond on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1” fully disagree to “5” fully agree. The resulting Cronbach’s alpha of .71 indicates that the measurement is reliable. Furthermore, the intraclass correlations (ICCs) and interrater reliability (Rwg) were calculated to evaluate whether aggregation of the individual scores to the team level was justified. The ICC(1) findings show that team autonomy has a small to medium (0.08) association with team membership, and the ICC(2) shows that 63% of the variance in team autonomy is explained on the team level (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008). In addition, the Rwg score of .83 is sufficiently above .7, meaning that aggregated scores of team autonomy are considered accurate (Bliese, Citation2000).

Individual vitality was calculated by three items, based on the UBES survey of Schaufeli and Bakker (Citation2003), that were included in the survey for professionals. An example item being “At work I am full of energy.” Answers were provided on a seven-point Likert scale from “1” never to “7” always/daily. The resulting Cronbach’s alpha of .92 indicates that this scale reliably measures individual validity. The ICC(1) score of .04 suggests that there is a small association with team membership, and the Rwg value of .41 shows a weak agreement between team members, both confirming that vitality is indeed an individual-level construct (Bliese, Citation2000; Woehr et al., Citation2015). In addition, the ICC(2) score shows that 19% of the variability in the professionals’ vitality ratings is related to their team membership. This indicates that there is also sufficient variance at the between team level, and individual vitality can be adequately examined in the multilevel model (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008).

Team innovation was evaluated in the survey of supervisors on the basis that previous healthcare research had shown them able to provide an informed and subjective assessment (Mitchell & Boyle, Citation2019). The measurement scale contained four items based on the scale developed by Anderson and West (Citation1998), adapted by de Dreu (2002), with an example item being “Team members often implement new ideas to improve the quality of our products and services.” Agreement was measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1” fully disagree to “5” fully agree. With a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 the scale was considered reliable, and with the concept being measured at the supervisor level, there was no need to further aggregate the data.

Control variables included the individual team members’ age measured in chronological years as previous studies on well-being at work suggest that growing older is accompanied by greater affective well-being (Warr, Citation1990), more positive job attitudes (Ng & Feldman, Citation2010) and increased intrinsic motivation (Kooij et al., Citation2011), all suggesting that age could have a significant positive influence on individual vitality. Another control variable included was the individual team members’ highest completed education level measured in the professionals’ survey. Based on the Dutch educational system the education level was measured in six categories (1, elementary education; 2, secondary education; 3, vocational education; 4, higher professional education; 5, academic education; and 6, doctoral education). In line with previous research by, for example, Vermeeren (Citation2014), this variable was included in the analysis as a continuous variable. Earlier research has shown that education level is positively associated with well-being in general (Witter et al., Citation1984) and mental well-being specifically (Jongbloed, Citation2018). Given that well-being encompasses subjective vitality it can be assumed that education level also has a significant positive influence on individual vitality.

Common method bias

The central concepts in this study are, by their very nature, perceptual and this makes a survey an appropriate measurement method (George & Pandey, Citation2017). However, using a survey for both the independent and the dependent variables can lead to systematic error variance that inflates the correlations, also known as common method bias (CMB) (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Several procedures were therefore applied to reduce the potential CMB based on Podsakoff et al.’s (Citation2012) recommendations. First, the concept measurements were obtained from two distinct sources. While the professionals’ survey measured perceptions of the teams’ autonomy and feelings of vitality, the supervisors’ survey measured supervisor judgment of team innovation. Furthermore, the questionnaire measured several other concepts that made it possible to physically separate the measurements of team autonomy and of individual vitality, reducing the salience of the link between the two concepts. Furthermore, with this in mind, the measures of team autonomy and of individual vitality were evaluated on different scales.

Results

presents the means, standard deviations and correlations of the key variables and the control variables. The table shows that team autonomy and team innovation are positively and significantly correlated (r = .37, p < .01), which is in line with the first hypothesis suggesting that autonomous teams are more innovative than less autonomous ones. The correlations between the control variables and individual vitality are not significant, suggesting that the ages and education levels of the individual team members have no significant association with the level of individual vitality.

Measurement model

The multilevel measurement model was developed to test whether the latent constructs fit together as theoretically expected. It included the four items measuring team autonomy and four items measuring team innovation at the team level, and three items measuring vitality at the individual level. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted and the results show that the measurement model had a good fit with the data, as the RMSEA score of .02 and the SRMRwithin score of .00 were well below Padgett and Morgan’s (Citation2021) recommended cutoff scores of .03 and .04, respectively (Padgett & Morgan, Citation2021). This suggests that the theoretical model fitted the data well and the results of the measurement model can be found in the Online Appendix in Figure A1.

Structural model

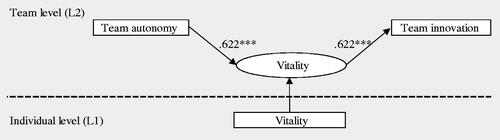

To test the remaining hypothesized relationships, the composite scores of the observed variables were calculated to serve as indicators of the latent variables as seen by Vermeeren (Citation2014), Ogbonnaya and Valizade (Citation2018), and Kaur and Kaur(Citation2022), and the causal paths and control variables were added to build a structural model. After an initial evaluation of the estimates, the control variables, age and education, are deleted from the model as they have no significant relationship with vitality. The model that includes only the hypothesized relationships then shows a positive significant relationship between team autonomy and vitality (β = 0.83, p < .001) and confirms Hypothesis 2. The relationship between vitality and team innovation is positive significant (β = 1.65, p < .01) as well, and therefore supporting Hypothesis 3. Furthermore, the direct effect between team autonomy and team innovation is non-significant (β = −0.99, p > .10). The direct effect is therefore deleted and the results show that, after removing the direct effect, both the relationship between team autonomy and individual vitality (β = 0.62, p < .001) and between individual vitality and team innovation (β = 0.62, p < .001) remained positive and significant. Furthermore, the results show a positive significant cross-level mediation (B = 0.89, p < .001, 95% CI [0.52, 1.27]) confirming Hypothesis 4. The significant results of multilevel structural equation modeling are also presented in .

Discussion and research implications

A key promise of team autonomy is its potential to spur public innovation and make employees feel more vital (Lee & Edmondson, Citation2017). The aim of this study was to validate and extend this argument with empirical evidence, showing a relationship between team autonomy and team innovation mediated by individual vitality. The results confirm the hypotheses and therefore contribute to the public administration literature in several ways. First, the findings reveal that public employees feel more vital when working in autonomous teams. This suggests that (semi-) autonomous teams indeed offer a motivating work environment in which employees can feel more positive and energized, as suggested in the self-determination theory (Ryan et al., Citation1999). The relevance of this finding is particularly salient in the field of public administration, as public employees are usually prone to low well-being as a result of overdemanding jobs in times of societal complexity (Potipiroon & Faerman, Citation2020). As such, the finding provides greater insight for those scholars who want to support public organizations in harnessing the positive energy of their employees (Bauwens et al., Citation2021). In addition, this finding also shows the relevance of the team context for understanding individual vitality as suggested by Bauwens et al. (Citation2021) and thus endorses their call for bringing in the team context in public administration.

Second, the findings demonstrate a positive relationship between individual vitality and team innovation. This supports the theory that, when employees feel more vital, they are more likely to engage in teamwork, show resilience, and approach challenges more positive (Ryan et al., Citation1999). In this line of reasoning, Borst et al (Citation2020) recently showed that employee eudaimonic well-being has a positive relationship with attitudinal, behavioral, and performance outcomes of individuals in public organizations. This study adds to this by showing that individual vitality, as an important indicator of eudaimonic well-being, has a positive relationship with innovation at the team level. It furthermore shows that a psychological perspective is a promising avenue for understanding why individual public employees develop new ideas through teamwork (Bauwens et al., Citation2021). With its focus on individual vitality as indicator of eudaimonic well-being, this finding especially subscribes to the argument that more attention should be paid to public employees’ vitality by scholars in the field of public administration (Tummers et al., Citation2015, Citation2018).

Next, this study shows a significant indirect relationship between team autonomy and team innovation mediated by individual vitality. This confirms the rationale of the IMOI model, which states that the relationship between team characteristics and team outcomes can be better understood by looking at team members’ behaviors and attitudes (Ilgen et al., Citation2005). This finding furthermore uniquely provides empirical evidence for the hypothesis that public organizations can stimulate public innovation by using (semi-) autonomous teams as a strategic approach to decentralized organizing. Put differently, this finding informs scholars on how a decentralized organizational approach can make use of (semi-) autonomous teams to enhance the public innovation. This finding furthermore explains that individual vitality, as an indicator of eudaimonic well-being, could be an important concept through which post-bureaucratic organizations are about to spur public innovation (Lee & Edmondson, Citation2017). Moreover, this supports the idea that individual and team factors should be considered simultaneously in order to better understand public innovation (Meijer, Citation2014; Van der Voet & Steijn, Citation2021). Inherently, this shows that multilevel research is a useful approach to evaluate the innovation process (Anderson et al., Citation2014).

Practical implications

From a practical perspective, the results show that (semi-) autonomous teams can play a significant role in boosting public innovation. Public organizations looking for structural ways to stimulate innovation would therefore do well to use (semi-) autonomous teams. This usually means that public organizations must adopt a more decentralized organizational structure and that public managers must ensure the teams have the right skills and resources to actually work autonomously (Magpili & Pazos, Citation2018). Furthermore, public managers should invest in supporting their team members while sharing the decision-making to stimulate their innovative processes (West, Citation2003). This study also highlights the importance of individual vitality as an important precondition for public innovation. Public organizations would therefore do well to monitor the characteristics of the work environment and how this affects the energy of employees (Bauwens et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, public managers are advised to be aware of the necessity to satisfy the needs of their employees for autonomy, participation in decision-making and teamwork in order to make them feel vital (Tummers et al., Citation2018).

Limitations and areas for future research

It is important for practitioners and scholars in the field of public administration that the limitations of this study are acknowledged, and potential avenues for future research to address these are offered. The first limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the data when seeking to test a mediation relationship. Previous studies by Maxwell and Cole (Citation2007) and by Maxwell et al. (Citation2011) suggest that cross-sectional data can lead to biased results from mediation analyses and instead urge the use of longitudinal data. Although this concern was not specifically related to multilevel mediation, future researchers could validate the presented findings using longitudinal data.

Second, an important limitation lies in the generalizability of the findings as the sample of this study includes only the teams of the three larger primary healthcare organizations in the Netherlands. This means that teams from other Dutch primary healthcare organizations are excluded from the study, which limits the generalizability of the results to Dutch primary healthcare and beyond. Future researchers interested in the primary healthcare teams are therefore advised to collect data from teams in a larger number of primary healthcare organizations in or outside the Netherlands. In addition, another interesting opportunity for researchers interested in teams in the public sector in more general, is to investigate whether the findings can be generalized to other industries or professions.

Third, the measure of team innovation adopted in this study is limited in the sense that it does not focus specifically on public service innovations aiming to create or maintain public value (Walker et al., Citation2019). Future research could therefore focus on further developing a measure for team innovation that fits the specific context in the public sector (Walker et al., Citation2019). While contextualizing the operationalization of innovation, future researchers are also recommended to reflect on the actual benefits of team innovation in the public sector. Possible perverse effects of innovations have often been neglected as public innovation is considered necessary, however, a more nuanced understanding of the effects of public innovation is desirable. This means that consideration is also given to the desirability of the innovation results in terms of public value (Meijer & Thaens, Citation2021).

Next, the results of this study could be limited by the relatively low team tenure of some respondents. Although it concerns only 15,8% of the respondents who have been working in their team for less than six months (and only 1,3% of the respondents working less than three months), it remains uncertain whether these employees with this relatively low tenure were able to adequately assess the teams’ autonomy and innovation. More research is therefore needed to understand how team tenure affects the quality of the analysis.

Furthermore, the multilevel mediated relationship central in this study omits the notion of a feedback loop in team dynamics and the concept of vitality as a reinforcing experience (Ilgen et al., Citation2005; Kark & Carmeli, Citation2009). It remains therefore unknown to what extent the individual vitality is influenced by previous team innovations, or even to what extent team autonomy is already affected by previous team innovations and/or individual vitality. Some caution is therefore required when it comes to the causality of the results, and future researchers are recommended to study cyclical processes between team autonomy, individual vitality, and team innovation (Ilgen et al., Citation2005).

Also, this study relies on the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain the relationship between team autonomy and individual vitality. However, this line of reasoning ignores the potential negative effect of team autonomy on individual autonomy due to too strong social cohesion. Although studies by van Mierlo et al (Citation2006) and Jønsson and Jeppesen (Citation2013) found that team autonomy has a positive association with individual autonomy in various kinds of teams, it is unknown whether this accounts for the primary healthcare teams in this study as well. Further research is therefore needed to understand whether team autonomy indeed enhances perceived autonomy in primary healthcare teams as assumed in the use of the self-determination theory.

Another recommendation for future researchers would be to investigate under which conditions the relationship between autonomy and innovation is optimized in the public context, given that previous findings suggest that the influence of autonomy and vitality on innovation may not be that straightforward. For example, Mitchell and Boyle (Citation2019) found that a positive mood is only useful for team innovation if the professional differences among the team members are salient. Further research is thus needed to understand which specific factors of the Dutch social welfare context were influential in the relationship between autonomy and vitality that led to innovation in the current research environment.

Conclusions

Given the need for public innovation in order to deliver high-quality public services, it is critical to understand how a motivating work environment can inspire public employees to engage in collective problem solving (Luu et al., Citation2019). Here, this study contributes to the field of public administration by providing an empirical analysis of how the positive relationship between team autonomy and team innovation evolves through the enhancement of team members’ individual vitality. By integrating the literature on (behavioral) public administration and (public) innovation, this study has set the scene with the intention to encourage other researchers to further examine the role of teams and employees in developing public innovation. When doing so, future researchers are encouraged to adopt a psychological perspective, as this study demonstrates that understanding how individual employees feel can well explain why adopting autonomous teams holds promise in the current context of increasingly complex social problems. For public organizations that want to facilitate employee well-being and public innovation, it is important that they endow teams with decision-making power. This will foster the vitality of the individual employees, which, in turn, stimulates them to share new ideas and engage in teamwork to develop innovative solutions. The implementation of autonomous teams is therefore an important step forward in ensuring high-quality public service delivery and good employment practices in today’s society.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not required by the research institute nor by the Dutch law on medical research (Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, http://www.ccmo.nl) since the study is based on a single anonymous survey that is free from radical, incriminating or intimate questions. Furthermore, participation in the survey was voluntary and all participants were considered to be competent to fill in the survey in a reasonable time period of approximately twenty minutes. Complete confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed, and all participants completed the consent form. The data were managed in accordance with the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.4 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alissa Lysanne van Zijl

Alissa Lysanne van Zijl, Msc. ([email protected]) is an assistant professor at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

References

- Alper, S., Tjosvold, D., & Law, K. S. (1998). Interdependence and controversy in group decision making: Antecedents to effective self-managing teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 74(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2748

- Anderson, N. R., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527128

- Anderson, N. R., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(3), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199805)19:3<235::AID-JOB837>3.0.CO;2-C

- Atwater, L., & Carmeli, A. (2009). Leader-member exchange, feelings of energy, and involvement in creative work. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.07.009

- Bauwens, R., Decramer, A., & Audenaert, M. (2021). Challenged by great expectations? Examining cross-level moderations and curvilinearity in the public sector job demands-resources model. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 41(2), 319–337.

- Bekkers, V., Edelenbos, J., & Steijn, B., (2013). Innovation in the public sector: Linking capacity and leadership. Pelgrave Macmillan.

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Ed.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (1st ed., pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

- Borst, R. T. (2018). Work-related well-being of (semi-)public sector employees bringing in the job demands-resources model of work engagement [Doctoral dissertation, Radboud University Nijmegen]. Radboud Repository.

- Borst, R. T., Kruyen, P. M., & Lako, C. J. (2019). Exploring the job demands-resources model of work engagement in government: Bringing in a psychological perspective. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 39(3), 372–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X17729870

- Borst, R. T., Kruyen, P. M., Lako, C. J., & de Vries, M. S. (2020). The attitudinal, behavioral, and performance outcomes of work engagement: A comparative meta-analysis across the public, semipublic, and private Sector. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 40(4), 613–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X19840399

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. The Guilford Press.

- Campion, M. A., Papper, E. M., & Medsker, G. J. (1996). Relations between work team characteristics and effectiveness: A replication and extension. Personnel Psychology, 49(2), 429–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01806.x

- Dackert, I. (2016). Creativity in teams: The impact of team members’ affective well-being and diversity. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 04(09), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2016.49003

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- de Dreu, C. K. W. (2002). Team innovation and team effectiveness: The importance of minority dissent and reflexivity. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11(3), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320244000175

- Dijkhoff, T. (2014). The Dutch Social Support Act in the shadow of the decentralization dream. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 36(3), 276–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2014.933590

- George, B., & Pandey, S. K. (2017). We know the yin-but where is the yang? Toward a balanced approach on common source bias in public administration scholarship. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 37(2), 245–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X17698189

- Hoegl, M., & Parboteeah, P. (2006). Autonomy and teamwork in innovative projects. Human Resource Management, 45(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20092

- Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M., & Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: From input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 517–560.

- Jakobsen, M. L. F., & Thrane, C. (2016). Public innovation and organizational structure: Searching (in vain) for the optimal design. In J. Torfing & P. Traintafillou (Eds.), Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance, or vice versa? (pp. 217–236). Cambridge University Press.

- Jiang, Y., & Chen, C. C. (2018). Integrating knowledge activities for team innovation: Effects of transformational leadership. Journal of Management, 44(5), 1819–1847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316628641

- Jongbloed, J. (2018). Higher education for happiness? Investigating the impact of education on the hedonic and eudaimonic well-being of Europeans. European Educational Research Journal, 17(5), 733–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118770818

- Jønsson, T., & Jeppesen, H. J. (2013). Under the influence of the team? An investigation of the relationships between team autonomy, individual autonomy and social influence within teams. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.672448

- Kalliola, S. (2003). Self-designed teams in improving public sector performance and quality of working life. Public Performance & Management Review, 27(2), 110–122.

- Kark, R., & Carmeli, A. (2009). Alive and creating: The mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(6), 785–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.571

- Kaur, S., & Kaur, G. (2022). Human resource practices, employee competencies and firm performance: A 2-1-2 multilevel mediational analysis. Personnel Review, 51(3), 1100–1119. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2020-0609

- Kooij, D. T. A. M., de Lange, A. H., Jansen, P. G. W., Kanfer, R., & Dikkers, J. S. E. (2011). Age and work-related motives: Results of a meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(2), 197–225. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.665

- Krull, J. L., & Mackinnon, D. P. (2001). Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36(2), 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06

- Lahat, L., & Ofek, D. (2022). Emotional well-being among public employees: A comparative perspective. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 42(1), 31–59.

- LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

- Lee, M. Y., & Edmondson, A. C. (2017). Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 37, 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2017.10.002

- Luu, T. T., Rowley, C., Dinh, C. K., Qian, D., & Le, H. Q. (2019). Team creativity in public healthcare organizations: The roles of charismatic leadership, team job crafting, and collective public service motivation. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(6), 1448–1480. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1595067

- Magpili, N. C., & Pazos, P. (2018). Self-managing team performance: A systematic review of multilevel input factors. Small Group Research, 49(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496417710500

- Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23–44.

- Maxwell, S. E., Cole, D. A., & Mitchell, M. A. (2011). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(5), 816–841.

- Meijer, A. J. (2014). From hero-innovators to distributed heroism: An in-depth analysis of the role of individuals in public sector innovation. Public Management Review, 16(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.806575

- Meijer, A. J., & Thaens, M. (2021). The dark side of public innovation. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(1), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2020.1782954

- Mitchell, R. J., & Boyle, B. (2019). Inspirational leadership, positive mood, and team innovation: A moderated mediation investigation into the pivotal role of professional salience. Human Resource Management, 58(3), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21951

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). The relationships of age with job attitudes: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 63(3), 677–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01184.x

- Ogbonnaya, C., & Valizade, D. (2018). High performance work practices, employee outcomes and organizational performance: A 2-1-2 multilevel mediation analysis. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(2), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1146320

- Osborne, S. P., & Brown, K. (2012). Managing change and innovation in public service organizations. Routledge.

- Padgett, R. N., & Morgan, G. B. (2021). Multilevel CFA with ordered categorical data: A simulation study comparing fit indices across robust estimation methods. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1759426

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

- Potipiroon, W., & Faerman, S. (2020). Tired from working hard? Examining the effect of prganizational ctizenship behavior on emotional exhaustion and the buffering roles of public service motivation and perceived supervisor support. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(6), 1260–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2020.1742168

- Preacher, K. J., Zhang, Z., & Zyphur, M. J. (2011). Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multilevel data: The advantages of multilevel SEM. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 18(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2011.557329

- Rangus, K., & Slavec, A. (2017). The interplay of decentralization, employee involvement and absorptive capacity on firms’ innovation and business performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 120, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.12.017

- Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. E., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029315

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). University of Rochester Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Work and organizations: Promoting wellness and productivity. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development and wellness (pp. 532–560). The Guilford Press.

- Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., Nix, G. A., & Manly, J. B. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 266–284.

- Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65(3), 529–565.

- Schaufeli, W., & Bakker, A. (2003). Voorlopige handleiding Utrechtse bevlogenheidschaal (UBES)[Preliminary manual Utrecht Engagement Scale (UBES)]. Utrecht University.

- Silva, B. C., Bosancianu, C. M., & Littvay, L. (2019). Multilevel structural equation modeling. SAGE Publications Inc.

- Tummers, L., Kruyen, P. M., Vijverberg, D. M., & Voesenek, T. J. (2015). Connecting HRM and change management: The importance of proactivity and vitality. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(4), 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2013-0220

- Tummers, L., Steijn, B., Nevicka, B., & Heerema, M. (2018). The effects of leadership and job autonomy on vitality: Survey and experimental evidence. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 38(3), 355–377.

- Uhl-Bien, M., & Graen, G. B. (1998). Individual self-management: Analysis of professionals’ self-managing activities in functional and cross-functional work teams. Academy of Management, 41(3), 340–350.

- Van der Voet, J., & Steijn, B. (2021). Team innovation through collaboration: How visionary leadership spurs innovation via team cohesion. Public Management Review, 23(9), 1275–1294.

- van Mierlo, H., Rutte, C. G., Vermunt, J. K., Kompier, M. A. J., & Doorewaard, J. A. C. M. (2006). Individual autonomy in work teams: The role of team autonomy, self-efficacy, and social support. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(3), 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500412249

- van Mierlo, H., Rutte, C. G., Vermunt, J. K., Kompier, M. A. J., & Doorewaard, J. A. C. M. (2007). A multi-level mediation model of the relationships between team autonomy, individual task design and psychological well-being. The British Psychological Society, 80, 647–664.

- Vermeeren, B. (2014). Variability in HRM implementation among line managers and its effect on performance: A 2-1-2 mediational multilevel approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(22), 3039–3059. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.934891

- Walker, R., Sawhney, M., & Chen, J. (2019). Public service innovation: A typology. Public Management Review, 22(11), 1674–1698.

- Walter, F., & van der Vegt, G. S. (2013). Harnessing members’ positive mood for team-directed learning behaviour and team innovation: The moderating role of perceived team feedback. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.660748

- Warr, P. (1990). The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(3), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00521.x

- West, M. A. (2003). Innovation implementation in work teams. In P. B. Paulus & B. A. Nijstad (Eds.), Group creativity: Innovation through collaboration (pp. 245–276). Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Witter, R. A., Okun, M. A., Stock, W. A., & Haring, M. J. (1984). Education and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 6(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737006002165

- Woehr, D. J., Loignon, A. C., Schmidt, P. B., Loughry, M. L., & Ohland, M. W. (2015). Justifying aggregation with consensus-based constructs: A review and examination of cutoff values for common aggregation indices. Organizational Research Methods, 18(4), 704–737. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115582090

- Wynen, J., Verhoest, K., & Rübecksen, K. (2014). Decentralization in public sector organizations. Do organizational autonomy and result control lead to decentralization toward lower hierarchical levels? Public Performance & Management Review, 37(3), 496–520.

- Yeh, S.-T., & Walter, Z. (2016). Determinants of service innovation in academic libraries through the lens of disruptive innovation. College & Research Libraries, 77(6), 795–804. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.6.795

- Zijl, A. L., Vermeeren, B., Koster, F., & Steijn, B. (2019). Towards sustainable local welfare systems: The effects of functional heterogeneity and team autonomy on team processes in Dutch neighbourhood teams. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12604