Abstract

The public sector is increasingly collaborating with the private sector in the development of large-scale public infrastructure projects. However, the difficulties arising due to working across organizational boundaries are often detrimental to project performance. This article argues that boundary-spanning activities can enhance the quality of collaboration and subsequently the performance of projects. Boundary spanners utilize relational governance mechanisms and undertake conscious endeavors for building interorganizational relationships by engaging in activities, such as coordination and communication with the stakeholders. The data for this study are composed of 158 survey responses from lead public managers involved in Dutch national public infrastructure projects. The data are analyzed using structural equation modeling. The study demonstrates that the quality of collaboration has a significant impact on the performance of the project during the implementation phase. Further, we find that the different boundary-spanning activities are interconnected and that they have a significant positive relationship on project performance, with a mediating effect of collaboration. The study concludes that, and shows how boundary spanners are vital to the collaborative processes through which public infrastructure projects are implemented.

1. Introduction

Government agencies worldwide are increasingly engaging in collaborative governance for achieving policy objectives (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007; O’Flynn, Citation2008; Vento & Sjöblom, Citation2018). One of the primary motives for collaboration is the pooling of resources, thus efficiently utilizing the resources and leading to better services (Mitchell et al., Citation2015). Recent studies show that successful collaborative governance requires relational governance, in addition to and alongside contractual governance (e.g., Benítez-Ávila et al., Citation2018; Warsen et al., Citation2019). Depending solely on contractual governance is not practical as it is impossible to account for all unforeseen circumstances in a contract (Brown et al., Citation2016). A relational approach to governance, therefore, aims to build trustful interpersonal relationships between partners centered on a common interest (Poppo & Zenger, Citation2002). These relationships then act as a medium for resource transactions (Cardenas et al., Citation2017). Research has indeed shown that the success of a project depends significantly on maintaining good relationships between the involved stakeholders (e.g., De Schepper et al., Citation2014; Mok et al., Citation2015; Verweij, Citation2015).

Existing research has established that, in projects, micro-level activities and interpersonal dynamics between the collaborating stakeholders have an impact on the larger collaborative environment (Keast, Citation2016). Little is known, however, about the exact activities and their impact on the quality of the collaboration and whether this leads to better project performance. On a micro level, especially cross-boundary work is often discussed to play a crucial role in effectively facilitating relational governance (Zheng et al., Citation2008). Such work, performed by boundary spanners, involves actions or behavior focused on gathering resources or support across boundaries for achieving project completion and success (Wilemon, Citation2014). Based on a systematic literature review into boundary spanning, Van Meerkerk and Edelenbos (Citation2018, p. 58) provide the following definition of boundary spanners:

People who proactively scan the organizational environment, employ activities to cross organizational or institutional boundaries, generate and mediate the information flow and coordinate between their “home” organization or organizational unit and its environment, and connect processes and actors across these boundaries.

Studies show that boundary spanners play an important role in capturing the potential of collaborative relationships by being a conduit to join efforts and work toward mutually agreed goals (Gustavsson & Gohary, Citation2012). From the literature, we find that some of these activities are more relational in nature and others are more management-oriented (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018). Despite the growing importance of boundary-spanning activities, however, there has been almost no detailed investigation of the effect of different sets of boundary-spanning activities on collaboration and project performance; and this requires further investigation (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018).

Previous studies have demonstrated that boundary spanners are important for organizational performance (Dollinger, Citation1984), as well as for other inter-organizational outcomes or network performance (Luo, Citation2001; Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2014). However, less attention has been paid to boundary-spanning activities in the implementation phase of well-defined projects. This is especially true for the literature on public-private partnerships (Casady et al., Citation2022; Jones & Noble, Citation2008; Warsen, Citation2021), while in particular in the implementation of such partnerships stakeholders are expected to actively leverage collaborative arrangements to accomplish common goals (Margerum, Citation2008). To bridge this gap, we investigate how different boundary-spanning activities during the project implementation phase impact collaboration and subsequently project performance. The lead public managers become principally responsible for the public infrastructure development project and have an important boundary-spanning role in managing the project and the quality of the collaboration. To achieve good collaboration, they could invest in building and maintaining relationships through boundary-spanning activities (Busscher et al., Citation2022). Using covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), we analyze 158 survey responses from lead public managers involved in Dutch national public infrastructure projects.

The Dutch context is well-suited for studying collaboration because of its long tradition of collaborative relationships between the public and private sectors, including in the development of public infrastructure projects (Koppenjan & de Jong, Citation2018). Joint partnerships between the public and private sectors have evolved since the 1980s with the majority of the public-private collaborative projects being developed in the infrastructure sector (Klijn, Citation2009); and the performance of the private sector is steered by the public sector based on contracts (Koppenjan & de Jong, Citation2018). Such contracts with their sanctioned governance and administrative structures can provide a shared collaborative space for public and private sectors in public infrastructure projects to work together. Moreover, recently a “Market Vision” was drafted jointly by the public and the private sectors, emphasizing again that along with the contractual agreements, there must be good collaboration developed through constructive dialogues between partners, as one of the guiding principles (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu, Citation2016; Rijkswaterstaat, Citation2019).

2. Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Due to their varying interests, the definitions of project performance in collaboration may differ between the collaborating partners (McGuire & Agranoff, Citation2011). In the context of collaboration in public infrastructure projects, narrow definitions of performance tend to focus on on-time and on-budget delivery, while broader definitions of performance also include subjective satisfaction of the participants as well as a cost-benefit assessment of the developed infrastructure (Skelcher & Sullivan, Citation2008; Verweij, Citation2015; Warsen et al., Citation2018). Studies of project performance often aim to measure if the set objectives of the project have been achieved (Muzondo & McCutcheon, Citation2018). However, due to the different interests and perceptions of stakeholders in complex infrastructure projects, these objectives, and their assessment might differ (Leendertse & Arts, Citation2020; Lehtonen, Citation2014; Verweij, Citation2015). There is no prescribed single correct way to measure project performance (Khosravi et al., Citation2020). In addition, different dimensions of performance might conflict with each other, e.g., on-time delivery vs. more innovative or robust solutions. In this study, we, therefore, follow previous studies and focus on different dimensions of public project performance, including perceived effectiveness of the solution offered, robustness of the results, cost-effectiveness, on-time delivery, and support of the partners in the project for the results (Koppenjan et al., Citation2020; Steijn et al., Citation2011; Warsen et al., Citation2018).

2.1. Collaboration and performance

The literature on collaboration and relational governance stresses the importance of social relationships and mutual interdependencies between public and private actors for realizing good performance (Eriksson & Westerberg, Citation2011; Warsen et al., Citation2019), in this case, the successful completion of public infrastructure projects. According to Thomson et al. (Citation2007, p. 25) collaboration is broadly defined as:

a process in which autonomous or semi-autonomous actors interact through formal and informal negotiation, jointly creating rules and structures governing their relationships and ways to act or decide on the issues that brought them together; it is a process involving shared norms and mutually beneficial interactions.

This definition highlights that collaborative quality is characterized by developing shared norms and attitudes. The main idea is that, through collaboration, better performance for public services can be achieved, or policy problems can be solved that a single organization could not do by itself (Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003; Ansell & Gash, Citation2007; Huxham et al., Citation2000).

Effective collaboration is characterized by joint problem-solving in the face of unexpected events, by developing shared norms and responsibilities, and by ways to deal with conflicts (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007; Thomson et al., Citation2007). In practice, informal relationships are cultivated in collaborative governance through two-way communication between private and public actors (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007). Even if adverse relationships exist, involved actors work toward having cooperative alliances to see the entire project to fruition (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007).

Collaboration provides a frame of reference, which helps public and private actors to deal with difficult and/or unexpected situations and to search for win-win solutions (Poppo & Zenger, Citation2002; Verweij, Citation2015; Warsen, Citation2021). High-quality collaboration helps to facilitate opportunities among the stakeholders and to instill commitment toward the project through relationship building, and this creates a supportive environment for the stakeholders to effectively contribute to the project outcome (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018). Long-term collaboration can be considered as a means to achieve integration between partners and it could help in knowledge sharing (Eriksson et al., Citation2017). Good collaboration increases the accessibility to stakeholders with relevant knowledge and expertise (Vento & Sjöblom, Citation2018), and benefits project performance through improved relationships and organizational learning (Mitchell et al., Citation2015; Verweij, Citation2015). Given the assumed benefits of collaboration, and given previous studies on public-private collaboration and the relationship to performance in public infrastructure projects, we formulate the following hypothesis:

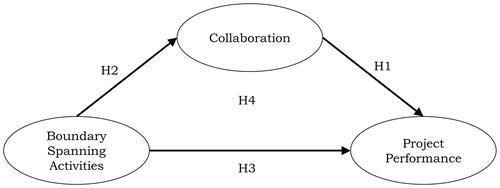

H1: Good collaboration between the public and private actors has a positive effect on project performance.

2.2. Boundary spanning activities and the impact on collaboration and performance

Boundary spanners are individuals who keep the cogwheels turning in collaboration, by maintaining interactions with the partnering organizations (Marchington et al., Citation2005). Boundary spanners can strengthen the interpersonal trust at the interface between the partner organization and the home organization (Williams, Citation2002). They are facilitators of collaborations and partnerships (Curnin & Owen, Citation2014; Williams, Citation2012).

Although both collaboration and boundary-spanning aim at capturing the synergy of working together, they are fundamentally different. Collaboration is a process that offers a way for stakeholders to build and manage relationships by creating shared norms and attitudes for working together across boundaries (Williams, Citation2012). This provides a basis for boundary spanners to engage in activities, which could lead to opportunities for fortifying the collaboration. Boundary spanners work within a collaboration—proactively utilizing potential opportunities to improve the quality of collaboration. For example, they could be involved in informal relational and mediating activities to develop shared working arrangements at the micro-level. Similarly, boundary spanners involve themselves in activities that build relationships and develop partnerships (Noble & Jones, Citation2006).

Boundary spanning thus involves various types of activities. Based on a systematic review of the literature, Van Meerkerk and Edelenbos (Citation2018) find four different types of boundary-spanning activities: relational activities, mediation and facilitation activities, information exchange and knowledge sharing activities, and coordination and negotiation activities (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018; see also Jesiek et al., Citation2018). Some of these boundary-spanning activities are more relational in nature (Sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2); others are more management-oriented (Sections 2.2.3 and 2.2.4) (cf. Edelenbos & Klijn, Citation2009).

2.2.1. Relational activities

Boundary spanners connect stakeholders across the stakeholder network (Lundberg, Citation2013). Relational capabilities are required for connecting stakeholders across boundaries for a successful collaboration (Ungureanu et al., Citation2021). This is achieved by building and maintaining inter-organizational relations (Marchington et al., Citation2005), not just based on formal contractual arrangements but also on informal and personal relationships (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018). Developing the partnership through relation-building via daily encounters is how boundary spanners operate (Noble & Jones, Citation2006). To align the interests of the collaborating parties, boundary spanners have to develop good linkages, both in their own organization and with the partnering organization (Eriksson et al., Citation2017; Smith & Thomasson, Citation2018; Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018). According to Tushman and Scanlan (Citation1981), it is exactly the combination of internal linkages (in their own unit or organization) and external linkages (to other organizations) which makes up the perceived competence and determines the status of boundary spanners. Their work entails facilitating situations that could lead to a win-win situation for the partnering organizations, by understanding the different needs and not just acting in self-interest (Stjerne et al., Citation2019).

2.2.2. Mediation and facilitation

The boundary spanner works toward building consensus between the organizations involved in the collaboration. They need to be able to identify the opportunities and undertake proactive measures in ideating strategies to seize the opportunity, so as to benefit the collaboration (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018). They can take the initiative to connect individuals across boundaries and strengthen the collaboration (Williams, Citation2012). This set of activities deals with actively engaging with their partners to influence or sway their opinion to benefit the project (Lundberg, Citation2013). Boundary spanners do this by bridging and strengthening ties with the external actors (Brion et al., Citation2012). In a collaboration between public and private actors, boundary spanners are confronted with different interests and identities. They are skilled in mediating these different interests and in bringing unlikely partners together (Williams, Citation2002).

Given the importance of building and maintaining relationships across boundaries for developing good collaboration, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Boundary spanning activities, particularly relational and mediating activities, have a positive effect on the collaboration between the public and private partner.

Moreover, boundary-spanning actions at the individual level may lead to a better fit between organizational processes, better aligning different actors’ interests and values, and as such achieve higher performance (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2010; Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2014). The intended project outcome would require boundary spanners to facilitate processes of management by navigating the organizational complexities using boundary-spanning activities, such as informational and coordinating activities (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992a).

2.2.3. Information exchange and knowledge sharing

Boundaries increase the efficiency of processes within a system, but there is a possibility that the system becomes too specialized, with the consequence that it no longer observes, or is able to adapt to, changes in the external environment. Projects have dynamic environments and the boundary spanners need to be able to quickly adapt to the changing circumstances by dealing with a wide array of information sources (Dollinger, Citation1984). Boundary spanners are involved in processing the information from the external environment through methods, such as filtering, storing, and translating; and they disseminate the information within the home organization (Nelson-Marsh, Citation2017). Competent boundary spanners know where to collect information, how to attain that information, and who needs to be made aware of the information, without overwhelming the recipients (Miller, Citation2008). However, this is not just a matter of disseminating information. Boundary spanners take up the role of managing the information flow by gathering information from external project environments, sorting the information based on the relevance, and then translating the information to the project environment (Birkinshaw et al., Citation2017; Tushman & Scanlan, Citation1981; Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018).

2.2.4. Coordination and negotiation

This activity links the organizations working together by coordinating cross-border activities and processes. Coordination activities require balancing the connection between the internal and external stakeholders (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018). Boundary spanners can play a role in aligning the interests of stakeholders and in creating a relational connection that goes over and beyond the interactions based on formal mechanisms (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992a). Through coordination, aligning, and negotiation, boundary spanners allow for a tighter coupling and smooth running of cross-boundary collaboration (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992a; Curnin & Owen, Citation2014).

With their role in moderating the flow of information, and translating information across organizational boundaries, coordinating and mediating processes across organizational boundaries, we expect that boundary-spanning activities also directly influence project performance:

H3: Boundary-spanning activities, particularly informational and coordinating activities, have a positive effect on project performance.

The processes of collaboration deal with how issues of common interest are addressed, reconcile differences and cultivate trust and reciprocity (Thomson & Perry, Citation2006). Boundary spanners play a role in facilitating the process by balancing the interests and values of the collaborating partners (O’Mahony & Bechky, 2008), and capturing the value of collaboration by influencing the interactions in the network (Scott et al., Citation2019). Assuming that boundary-spanning activities positively influence collaboration and project performance, and that collaboration also contributes to project performance, we expect a partially mediating role of collaboration:

H4: The relationship between boundary-spanning activities and project performance is partly mediated by collaboration.

3. Research design

The conceptual model () comprises of a structural model and a measurement model, which are formulated using observed and latent variables. For multivariate analysis, such as in the present paper, covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is a well-suited technique (Byrne, Citation2010). In SEM, the relationships in the hypotheses can be tested using latent variables derived from observed variables (De Carvalho & Chima, Citation2014).

3.1. Sampling and data collection

The data were collected through a survey sent to public managers from Rijkswaterstaat, the executive agency of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management in the Netherlands. The participants for the survey were selected based on their involvement in public infrastructure projects that had started (i.e., contract awarded) between 2006 and 2018. The information regarding the public infrastructure projects was accessed through the Rijkswaterstaat Project Database in May 2020. The two most prevalent contract types in the Project Database for partnering with the private sector were Design-and-Construct (D&C) and Design-Build-Finance-Maintain (DBFM) projects (see more about the contract types in Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020). A project was selected only if it had one of the said contract types and if it was a major infrastructure development project. Minor maintenance work projects, knowledge projects or programs, etc. were excluded because these involve different stakeholder networks, dynamics, and procurement and management dynamics (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020). Accordingly, most of the selected projects concern construction projects pertaining to major highways, water works, bridges, and/or tunnels. The dataset represents a total of 68 projects. In each of the surveyed infrastructure projects, the public managers are part of an Integrated Project Management (IPM) team (Rijkswaterstaat, Citation2014). The team consists of five core IPM roles: project manager, contract manager, stakeholder manager, technical manager, and the project control manager (see for descriptive statistics of role distribution). These lead public managers were contacted and asked to fill out the survey for a specific project. The data were collected in the period from October 2020 to January 2021. Before this, a pilot test was conducted in September 2020 to contextualize the study to public-private collaboration projects from Rijkswaterstaat and to further improve the questionnaire’s comprehensibility for the respondents.

Table 1. Summary of Demographics and Project Characteristics Distribution of the Survey.

The questionnaire was developed in English based on prior literature linking measurement items to latent constructs. It was then translated to Dutch by three English-Dutch bilinguals who are familiar with Dutch infrastructure planning generally and with Rijkswaterstaat projects in particular. The survey was published in Dutch to make it more accessible to the respondents. A total of 390 potential respondents were identified from the Rijkswaterstaat Project Database, but contact details could be retrieved for 308 managers. The managers are usually involved in more than one project; we sent the survey to a maximum of two projects per manager to not overburden the managers. This provided us with a sample size of 406 survey respondents (i.e., 98 managers received invitations for two projects). Deleting invalid email addresses, we in the end had a sample of 392 respondents, from which we received 171 responses. A total of 13 responses were discarded from the dataset since they completed <35% of the survey. This brings the number of observations in the dataset to a total of 158 (from 58 projects). The response rate was 43.6% and the average completion rate was 93.4%. The conceptual model is relatively simple with three constructs making the sample size of 158 sufficient for this study.

3.2. Participant and project characteristics

The questionnaire posed a series of questions about the demographic characteristics as well as the characteristics of the project for which respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire. The responses are tabulated in . The response bias based on the demographic data was checked and no significant bias was found. In other words, there is no statistically significant difference between the projects based on the demographic data and the project data.

3.3. Method

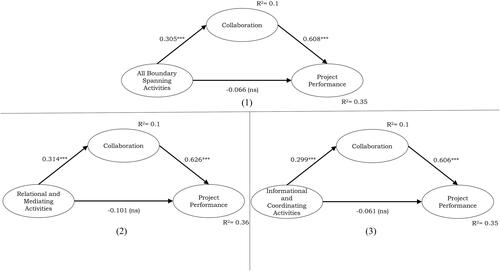

SEM estimates the model by demonstrating the correlations between the variables based on the covariance matrix (Collier, Citation2020) using AMOS (Version 25). Based on the theoretical concepts defining the latent variables, a set of questions was asked through the survey to gather data for the observed variables in the measurement model. As the first step of the analysis, the dataset generated from these responses was analyzed using Exploratory Factor analysis (EFA) to assess whether the observed variables measure the latent construct by identifying the underlying factors of the constructs (Collier, Citation2020). The EFA results demonstrated that the four boundary-spanning activities loaded onto a single construct. This indicates that the items pertaining to the boundary-spanning activities were found to be highly correlated with one another. Since the objective is to test the effect of relational and mediating activities as well as informational and coordinating activities on collaboration and project performance, we developed three models. The first model has all the items related to boundary spanning as one construct. The second model focuses on the relational and mediating activities and the third model examines the informational and coordinating activities (see also ). Following EFA, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) tested if the data fit the measurement model and the model was shown to have a good fit. The common variance between the variables is used to estimate the model parameters.

Figure 2. Hypotheses testing results using structural equation model analyzing the relationship of collaboration and perceived project performance to (1) Model 1—All boundary spanning activities, (2) Model 2—Only relational and mediating activities, and (3) Model 3—Only informational and coordinating activities. Note. ns: path is not significant; *** significant at 0.001.

The assumption of independence of observations and errors could be compromised as the data are clustered by projects. This has been accounted for, however, in the analysis by using clustered robust standard errors, which relaxes the assumption of independence of errors to the assumption of independence of clusters.

3.4. Measurement model

3.4.1. Boundary spanning

A new scale was developed to measure the construct of boundary spanning, based on the four types of boundary-spanning activities discussed in Section 2. Measurement scales of multiple studies have influenced the development of the new scale; this is shown in . The construct was measured using thirteen items and further classified into two categories: (1) relational and mediating activities and (2) informational and coordinating activities. It was scored on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates “very little involvement” and 7 indicates “involvement to a great extent.” Items from information collection and knowledge exchange activities include questions asking the respondents about the extent to which they exchanged “management information” and “technical knowledge” with contractors from the private sector. Similarly, items regarding relational activities inquired into the extent to which the respondent was involved in “building and maintaining long-lasting relationships with the private organization.” The various items are displayed in presented in Section 4.

Table 2. Literature Used to Develop the New Scale to Measure Boundary Spanning.

3.4.2. Collaboration

This scale is directly derived from the literature (Koppenjan et al., Citation2020, Citation2022; Warsen, Citation2021), and was measured on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 is “totally disagree” and 7 is “totally agree.” Six items were part of the measure and they indicated the degree of collaboration in the project (see further in ).

3.4.3. Perceived project performance

The measurement items for this construct have been adapted from Koppenjan et al. (Citation2020), who measured the success of the project based on satisfaction with the project as well as on performance measures, such as time and costs (cf. Petersen, Citation2019). Measurement of this construct followed the approach from prior research, where perceived project performance is used as a proxy for determining project performance (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016; Warsen et al., Citation2018). The respondents rated the performance of the project on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 is “totally disagree” and 7 is “totally agree.” The perceptions of the respondents regarding the success or failure of the projects were gathered through four items which determine the latent construct of perceived project performance (see further in ).

3.5. Non-response bias

Non-response bias is detected when the sample is not a characteristic representation of the population. There is a possibility of the presence of this bias as the data were collected online. To check the non-response bias, we divided the responses equally into two groups based on when the respondent responded to the survey. This means that observations 1–79 form the first group and observations 80–158 form the second group. The two groups were compared using the demographic and project characteristics from . The results indicated no significant difference between the two groups. Therefore, we can conclude that non-response bias is absent.

3.6. Common method bias

The methodological issues, which are inherent to the measurement scale or data collection through a self-reported survey, could have an impact on the data quality. The common method bias was tested through Harman’s one-factor test by performing an unrotated exploratory factor analysis. The covariance was found to be 41%, and since one factor does not account for the majority of the covariance, the bias is not pervasive (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Additionally, common method bias was analyzed by loading the items on the theoretical constructs and on a latent common method variance factor (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The model was then examined with and without the latent common method variance factor and negligible differences were observed. This indicates that common method bias is not an issue in this study.

3.7. Normality check

An assumption of the SEM technique is that the data satisfy the condition of multivariate normality (Collier, Citation2020). An assessment of normality indicated that there are no variables that are critically kurtotic with kurtosis values above 7 (Byrne, Citation2010). However, the multivariate normality could not be established due to the high value of the critical ratio in the normality assessment. Having non-normal data could lead to an inflated chi-square; and to remedy this issue (Collier, Citation2020), bootstrapping was performed on 5000 samples, the result of which is presented in .

3.8. Validity and reliability

The validity of the constructs is assessed using divergent validity and convergent validity, which are demonstrated in and , respectively. also shows the descriptive statistics. Convergent validity checks if all the items in a construct measure the same underlying concept; it is calculated by estimating if the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is above 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2010). Another check is to have all the factor loadings above 0.7—but 0.6 to 0.7 is also acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2010). Divergent validity examines whether two measures that should not be related are in fact not related. It is determined by comparing if AVE is greater than matrixed squared correlations with other constructs (Hair et al., Citation2010). The internal consistency of a construct is gauged from reliability assessments. The reliability of the constructs was measured using Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability; the measured value must be above the recommended value of 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2010). This criterion is satisfied by all the constructs in the model, as reported in .

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics and Discriminant Validity.

Table 4. Correlation among Latent Variables.

Table 5. Measurement Items and Their Reliability.

3.9. Control variables

By including control variables, we account for the potential influences of sample population or project characteristics on the model, to get unbiased estimates for the dependent variables (Collier, Citation2020). The demographic and project characteristics shown in were applied as the control variables to the structural model.

4. Results

4.1. Model fit

To obtain reliable results from hypothesis testing, the goodness of fit is measured using the fit indices. The fit indices indicate the fit of the data from the sample with the proposed model. The overall fit of the model is measured using chi-square per degree of freedom (χ2/df); the recommended value is 5 or less (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) value tests the closeness of the proposed model to a perfect model, with an acceptable value being below 0.08 (Hair et al., Citation2010). Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) evaluate the proposed model with a baseline model and the threshold values of these fit indices are 0.9 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The fit indices of the proposed models are presented in and it can be observed that the models have an acceptable fit.

Table 6. Summary of Model and Hypothesis Testing.

4.2. Structural model and hypothesis testing

The structural model estimates the relationships represented by the hypotheses. The results can be seen in and . It is worth noting that all the three models provide similar results when testing the hypotheses. Delving more in-depth into the full model, we find that the empirical findings support Hypothesis 1, stating that good collaboration impacts project performance positively. The relationship is strong: the standardized coefficient is 0.6 and statistically significant at p < 0.001. This indicates that when the quality of collaboration increases, it is more likely to have higher project performance. Hypothesis 2 postulates that boundary spanning has a positive effect on collaboration. This hypothesis is also confirmed: the standardized coefficient is 0.3 at p < 0.001. This can be interpreted as follows: projects with managers performing more boundary-spanning activities will likely result in having better quality collaboration with private partners. Hypothesis 3 is rejected due to an insignificant p-value (0.336), demonstrating that there is no statistically significant direct relationship between boundary spanning and project performance.

Since there is no direct relationship between boundary spanning to project performance, but an indirect relationship with the mediating effect of collaboration, Hypothesis 4 is partially true denoting full mediation, as there is a significant indirect effect of boundary spanning on performance. Comparing the results from the second and third models in shows that relational and mediating activities have a slightly higher influence on collaboration and performance than informational and coordinating activities.

4.3. Control variables

Among the tested control variables, there were no significant effects on the dependent variables. However, for boundary spanning, the significant influence was present from years of experience (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) and the scope of the project (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). This means that, as the work experience of a public manager increases, s/he tends to engage more in boundary-spanning activities. Similarly, when the complexity of the project increases, there is an increase in boundary-spanning activities undertaken. This makes sense and is in line with previous findings (Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2014): higher task complexity requires more boundary-spanning activities to manage the project.

5. Conclusion and discussion

The study was designed to determine the effect of various boundary-spanning activities performed by public managers on the quality of collaboration and on the performance of public infrastructure projects. The results of this study suggest that collaboration is essential for achieving higher project performance (H1), and that boundary spanning is important for collaboration (H2). This is in line with the studies by, for instance, Benítez-Ávila et al. (Citation2018) and Warsen (Citation2021), who found that relational governance remedies the drawbacks of incomplete contracting and has a strong positive influence on project performance (cf. Chen & Manley, Citation2014). Boundary spanning by public managers has a modest positive influence on project performance (H4); however, this relationship is not direct and therefore limits drawing straightforward conclusions. This demonstrates that the role of boundary spanners in collaborative governance is intricate. They achieve better outcomes by identifying and utilizing collaborative opportunities which could benefit the project. They achieve this by actively engaging in informal exchanges with the people involved in the stakeholder network. We can see that boundary spanners are vital to the collaborative process, and that the quality of collaboration strongly influences project performance.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The present study makes several contributions to the literature. First, we substantiated, using empirical research, that the performance of public infrastructure projects is strongly influenced by the quality of collaboration. This relationship is often assumed or studied qualitatively in previous works (Eriksson & Westerberg, Citation2011; Hällström et al., Citation2021). The results corroborate, amongst others, Ansell and Gash (Citation2007), Verweij (Citation2015), and Warsen (Citation2021), who suggested that public-private collaboration benefits public project performance by improving relationships among the actors involved. The strong impact of collaboration on project performance is an important finding, especially in contract-based partnerships, as it demonstrates that significant attention should be paid to the quality of collaboration alongside contractual governance to enhance performance. It can be observed that a composite of boundary-spanning activities contributes to improving collaboration indicating that boundary-spanning can be a means to implement relational governance.

Second, we provide insights into the boundary-spanning practices at the implementation phase of infrastructure development and this is a significant contribution in itself, as very few studies have studied this (Jones & Noble, Citation2008; Warsen, Citation2021). The analysis shows that boundary spanners, through relational governance strategies, contribute to enhancing the quality of collaboration and indirectly impact performance through collaboration. It reinforces the importance of boundary spanners in capturing the potential of collaboration (Gustavsson & Gohary, Citation2012; Zheng et al., Citation2008). Having investigated deeper into the various boundary-spanning activities, it was revealed that the relational and mediating activities are complementary to informational and coordinating activities, and enhance collaboration and subsequently improve performance in a similar manner. This implicit effect of boundary spanning by public managers on performance could mean that the public sector acts as a catalyst for enhancing the collaborative process. This, in turn, would require tailoring strategies depending on the need of the situation, such as steering, partnering, or even staying out of the situation (Bryson et al., Citation2014). A contextual explanation could be that the construction sector in the Netherlands is characterized as a system composed of strong and weak ties between public clients and private contractors, inter alia because of the limited number of players in the system (Leendertse & Arts, Citation2020). As a consequence, managers often meet each other repeatedly, also on different projects. This elevates the importance of collaboration in the Dutch context. In other contexts, perhaps characterized by less collaborative settings, collaboration might play a less dominant role in explaining performance. For collaborative settings, though, the quality of collaboration could be interpreted as the medium through which boundary spanning manifests itself and impacts the performance of public projects.

Third, an encompassing measurement scale was developed for boundary spanning, tailored specifically to the context of public-private collaboration. The scale surveys the interactions with the private sector partners from the perspective of public managers. This is a significant contribution because existing boundary-spanning measurement scales mostly focus on one aspect (see for an overview Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018), for example on knowledge sharing (Henttonen et al., Citation2016), and therefore have a limited scope; or they do not focus on the context of public-private collaboration specifically (Warsen, Citation2021). Boundary spanning is a term used for many different skills, activities, and capabilities that are crucial for cross-boundary work, such as understanding and gauging different perspectives, identifying opportunities, and taking action to tackle the challenges of multi-sectoral collaboration (Williams, Citation2002). The new scale provides a means to measure the operational as well as relational aspects of boundary spanning in public management. Based on boundary-spanning literature, four activity groups were identified: relational activities, mediation and facilitation activities, information and knowledge exchange activities, and coordination and negotiation activities. These four sets of activities were found to be highly correlated with one another, indicating that the activities are considerably interconnected thereby highlighting the complementary nature of the activities. In addition, the results showed the importance of these activities for making collaboration work.

5.2. Practical implications

This research has significant practical value in revealing that collaboration makes a dominant contribution to project implementation from the public manager’s perspective. Consistent with the literature on relational governance (Benítez-Ávila et al., Citation2018; Poppo & Zenger, Citation2002; Warsen et al., Citation2019), our results suggest that relational governance activities are essential to capture the potential of collaboration, even in contract-based partnerships. Furthermore, this study supports evidence from previous research that has suggested that collaboration is influenced by boundary spanning (Scott et al., Citation2019; Williams, Citation2012). For public organizations working together with private organizations in the implementation of public projects, this study highlights the pivotal role boundary spanners can play in achieving good collaboration and thereby good performance. The quality of collaboration can be increased if the interactions at the individual level are managed well (Scott et al., Citation2019). Boundary spanners are vital to the collaborative process. Therefore, investing in the development of skills for boundary-spanning will be beneficial for public projects in the long-run. It may be important that boundary-spanning actors are supported in their actions through changes in public management policies and practices. For instance, support from top management may encourage them to undertake boundary-spanning activities, such as building and maintaining productive work relationships, even if these activities mean that the boundary spanner has to go beyond his or her formal task description.

5.3. Limitations and directions for future research

The present study used empirical data collected from public managers. As such, it augments our knowledge of public-private collaboration from a public management perspective. Further studies could also include the private managers in the sampling (cf. Koppenjan et al., Citation2020), and compare their perspectives and experiences with those of the public managers, to shed light on what private boundary spanners can do to facilitate public-private collaboration. In addition, a case study approach could be used to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamic collaborative patterns involved, to also learn about the causal mechanisms underlying the relationships between boundary spanning and collaboration and between collaboration and public project performance.

This research focused on determining the activities that boundary spanners engage in and this is a significant contribution to the existing literature. Further investigations could build on this finding and determine the antecedents (e.g., interpersonal skills, project characteristics, trust-building mechanisms, or cultural differences) that facilitate boundary-spanning activities. This would be an important next step in the research on boundary spanning in public-private collaborative settings: we know from the literature that the behavior and actions of a boundary spanner are influenced by both character traits and contextual factors (Ewert & Loer, Citation2021; Van Meerkerk & Edelenbos, Citation2018). A more in-depth investigation of those traits and characteristics in the context of public-private collaboration can be a major step forward in designing effective and successful collaborative projects between public and private partners.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the long-term research co-operation between Rijkswaterstaat and the University of Groningen. The authors would like to thank all the respondents of the survey for their participation. We are also greatly indebted to Max van Heijst (Rijkswaterstaat) and to Ed van Vugt (Rijkswaterstaat) for making the data collection possible.

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest. The contents of this paper do not necessarily represent the views of Rijkswaterstaat and thus remain the authors’ responsibility.

Data availability statement

Due to the politicized and confidential nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shreya Anna Satheesh

Shreya Anna Satheesh is PhD candidate at the Department of Spatial Planning and Environment (University of Groningen, The Netherlands). Her research focuses on the boundary spanning between public and private sectors in a collaboration at the planning and implementation phases of public infrastructure development projects.

Stefan Verweij

Stefan Verweij is assistant professor of infrastructure planning, governance, and methodology at the Department of Spatial Planning and Environment (University of Groningen, The Netherlands). His research focuses on the design, implementation, and performance of collaboration in cross-sector governance networks, in particular public-private partnerships.

Ingmar van Meerkerk

Ingmar van Meerkerk is associate professor of interactive governance at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology (Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands). His research focuses on community-based initiatives, boundary spanning, innovation, democratic legitimacy, and performance in the field of urban, interactive governance and public-private partnerships.

Tim Busscher

Tim Busscher is assistant professor of infrastructure planning at the Department of Spatial Planning and Environment (University of Groningen, The Netherlands). His research focuses on management of spatial and infrastructure projects and programs. He also focuses on institutional analysis, in particular, the planning, realization, and renewal of transport infrastructure networks.

Jos Arts

Jos Arts is professor of environmental and infrastructure planning at the Department of Spatial Planning and Environment (University of Groningen, The Netherlands) and extraordinary professor, Unit Environmental Sciences & Management (North West University, South Africa). His research focuses on institutional analysis and design of integrated planning for sustainable infrastructure networks.

References

- Agranoff, R., & McGuire, M. (2003). Inside the matrix: Integrating the paradigms of intergovernmental and network management. International Journal of Public Administration, 26(12), 1401–1422. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-120024403

- Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992a). Bridging the boundary: External activity and performance in organizational teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(4), 634–665. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393475

- Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992b). Demography and design: Predictors of new product team performance. Organization Science, 3(3), 321–341. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.321

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Benítez-Ávila, C., Hartmann, A., Dewulf, G., & Henseler, J. (2018). Interplay of relational and contractual governance in public-private partnerships: The mediating role of relational norms, trust and partners’ contribution. International Journal of Project Management, 36(3), 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.12.005

- Birkinshaw, J., Ambos, T. C., & Bouquet, C. (2017). Boundary spanning activities of corporate HQ executives insights from a longitudinal study. Journal of Management Studies, 54(4), 422–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12260

- Brion, S., Chauvet, V., Chollet, B., & Mothe, C. (2012). Project leaders as boundary spanners: Relational antecedents and performance outcomes. International Journal of Project Management, 30(6), 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.01.001

- Brown, T. L., Potoski, M., & Slyke, D. V. (2016). Managing complex contracts: A theoretical approach. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv004

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Bloomberg, L. (2014). Public value governance: Moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12238

- Busscher, T., Verweij, S., & Brink, M. (2022). Private management of public networks? Unpacking the relationship between network management strategies in infrastructure implementation. Governance, 35(2), 477–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12602

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Multivariate applications series. In Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Cardenas, I. C., Voordijk, H., & Dewulf, G. (2017). Beyond theory: Towards a probabilistic causation model to support project governance in infrastructure projects. International Journal of Project Management, 35(3), 432–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.01.002

- Casady, C. B., Verweij, S., & Van Meerkerk, I. F. (2022). Conclusions about the performance advantage of PPP. In S. Verweij, I. F. Van Meerkerk, & C. B. Casady (Eds.), Assessing the performance advantage of public-private partnerships: A comparative perspective (pp. 206–228). Edward Elgar.

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018414

- Chen, L., & Manley, K. (2014). Validation of an instrument to measure governance and performance on collaborative infrastructure projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 140(5), 04014006. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000834

- Curnin, S., & Owen, C. (2014). Spanning organizational boundaries in emergency management. International Journal of Public Administration, 37(5), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.830625

- De Carvalho, J., & Chima, F. O. (2014). Applications of structural equation modeling in social sciences research. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 4(1), 6–11.

- De Schepper, S., Dooms, M., & Haezendonck, E. (2014). Stakeholder dynamics and responsibilities in public-private partnerships: A mixed experience. International Journal of Project Management, 32(7), 1210–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.01.006

- Dollinger, M. J. (1984). Environmental boundary spanning and information processing effects on organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 27(2), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.5465/255929

- Edelenbos, J., & Klijn, E. H. (2009). Project versus process management in public-private partnership: Relation between management style and outcomes. International Public Management Journal, 12(3), 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490903094350

- Eisenhardt, K. M., Furr, N. R., & Bingham, C. B. (2010). CROSSROADS—Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science, 21(6), 1263–1273. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0564

- Eriksson, P. E., Larsson, J., & Pesämaa, O. (2017). Managing complex projects in the infrastructure sector—A structural equation model for flexibility-focused project management. International Journal of Project Management, 35(8), 1512–1523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.08.015

- Eriksson, P. E., & Westerberg, M. (2011). Effects of cooperative procurement procedures on construction project performance: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Project Management, 29(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2010.01.003

- Ewert, B., & Loer, K. (2021). Advancing behavioural public policies: In pursuit of a more comprehensive concept. Policy & Politics, 49(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557320X15907721287475

- Gustavsson, T. K., & Gohary, H. (2012). Boundary action in construction projects: New collaborative project practices. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 5(3), 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538371211235272

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hällström, A., Bosch-Sijtsema, P., Poblete, L., Rempling, R., & Karlsson, M. (2021). The role of social ties in collaborative project networks: A tale of two construction cases. Construction Management and Economics, 39(9), 723–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2021.1949740

- Henttonen, K., Kianto, A., & Ritala, P. (2016). Knowledge sharing and individual work performance: An empirical study of a public sector organization. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(4), 749–768. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2015-0414

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huxham, C., Vangen, S., Huxham, C., & Eden, C. (2000). The challenge of collaborative governance. Public Management an International Journal of Research and Theory, 2(3), 337–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030000000021

- Jehn, K. A., & Mannix, E. A. (2001). The dynamic nature of conflict: A longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069453

- Jesiek, B. K., Mazzurco, A., Buswell, N. T., & Thompson, J. D. (2018). Boundary spanning and engineering: A qualitative systematic review. Journal of Engineering Education, 107(3), 380–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20219

- Jones, R., & Noble, G. (2008). Managing the implementation of public–private partnerships. Public Money and Management, 28(2), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2008.00629.x

- Keast, R. L. (2016). Shining a light into the black box of collaboration: Mapping the prerequisites for cross-sector working. In J. Butcher & D. Gilcrest (Eds.), The three sector solution: Delivering public policy in collaboration with not-for-profits and business (pp. 157–178). ANU Press.

- Khosravi, P., Rezvani, A., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2020). Emotional intelligence: A preventive strategy to manage destructive influence of conflict in large scale projects. International Journal of Project Management, 38(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.11.001

- Klijn, E. H. (2009). Public–private partnerships in the Netherlands: Policy, projects and lessons. Economic Affairs, 29(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0270.2009.01863.x

- Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. (2016). The impact of contract characteristics on the performance of public–private partnerships (PPPs). Public Money & Management, 36(6), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1206756

- Koppenjan, J., & de Jong, M. (2018). The introduction of public–private partnerships in the Netherlands as a case of institutional bricolage: The evolution of an Anglo‐Saxon transplant in a Rhineland context. Public Administration, 96(1), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12360

- Koppenjan, J., Klijn, E. H., Duijn, M., Klaassen, H., Van Meerkerk, I., Metselaar, S., Warsen, R., & Verweij, S. (2020). Leren van 15 jaar DBFM-projecten bij RWS: Eindrapport. Rijkswaterstaat.

- Koppenjan, J., Klijn, E. H., Verweij, S., Duijn, M., Van Meerkerk, I., Metselaar, S., & Warsen, R. (2022). The performance of public–private partnerships: An evaluation of 15 years DBFM in Dutch infrastructure governance. Public Performance & Management Review, 1(31), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2022.2062399

- Leendertse, W., & Arts, J. (2020). Public-private interaction in infrastructure networks – Towards valuable market involvement in the planning and management of public infrastructure networks. InPlanning.

- Lehtonen, M. (2014). Evaluating megaprojects: From the ‘iron triangle’ to network mapping. Evaluation, 20(3), 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00823.x

- Luo, Y. (2001). Antecedents and consequences of personal attachment in cross-cultural cooperative ventures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(2), 177–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667085

- Lundberg, H. (2013). Triple Helix in practice: The key role of boundary spanners. European Journal of Innovation Management, 16(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601061311324548

- Marchington, M., Vincent, S., & Cooke, F. L. (2005). The role of boundary-spanning agents in inter-organizational contracting. In Fragmenting work: Blurring organizational boundaries and disordering hierarchies (pp. 135–156). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199262236.003.0006

- Margerum, R. D. (2008). A typology of collaboration efforts in environmental management. Environmental Management, 41(4), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9067-9

- McGuire, M., & Agranoff, R. (2011). The limitations of public management networks. Public Administration, 89(2), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01917.x

- Miller, P. M. (2008). Examining the work of boundary spanning leaders in community contexts. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 11(4), 353–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120802317875

- Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu (2016). Marktvisie Rijkswaterstaat en Bouwsector.

- Mitchell, G. E., O’Leary, R., & Gerard, C. (2015). Collaboration and performance: Perspectives from public managers and NGO leaders. Public Performance & Management Review, 38(4), 684–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1031015

- Mok, K. Y., Shen, G. Q., & Yang, J. (2015). Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions. International Journal of Project Management, 33(2), 446–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.08.007

- Muzondo, F. T., & McCutcheon, R. T. (2018). The relationship between project performance of emerging contractors in government infrastructure projects and their experience and technical qualifications. Journal of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering, 60(4), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-8775/2018/v60n4a3

- nelson-Marsh, N. (2017). Boundary spanning. In C. R. Scott & L. K. Lewis (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of organizational communication (pp. 1–15). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118955567.wbieoc012

- Noble, G., & Jones, R. (2006). The role of boundary‐spanning managers in the establishment of public‐private partnerships. Public Administration, 84(4), 891–917. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00617.x

- O’Flynn, J. (2008). Elusive appeal or aspirational ideal? The rhetoric and reality of the ‘collaborative turn’ in public policy. In Collaborative governance: A new era of public policy in Australia (pp. 181–195). ANU E Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/CG.12.2008.17

- O’Mahony, S., & Bechky, B. A. (2008). Boundary organizations: Enabling collaboration among unexpected allies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(3), 422–459. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.53.3.422

- Petersen, O. H. (2019). Evaluating the costs, quality and value for money of infrastructure public-private partnerships: A systematic literature review. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 90(2), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12243

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Poppo, L., & Zenger, T. (2002). Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strategic Management Journal, 23(8), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.249

- Rijkswaterstaat (2014). Samenwerken & integraal projectmanagement (IPM): Eén manier van werken voor elk project.

- Rijkswaterstaat (2019). Op weg naar een vitale infrasector – Plan van aanpak en aanzet tot een gezamenlijk transitieproces. Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat.

- Scott, W. R., Levitt, R. E., & Garvin, M. J. (2019). Introduction: PPPs–theoretical challenges and directions forward. In Public–private partnerships for infrastructure development. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788973182.00006

- Skelcher, C., & Sullivan, H. (2008). Theory-driven approaches to analysing collaborative performance. Public Management Review, 10(6), 751–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030802423103

- Smith, E. M., & Thomasson, A. (2018). The use of the partnering concept for public–private collaboration: how well does it really work? Public Organization Review, 18(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-016-0368-9

- Steijn, B., Klijn, E. H., & Edelenbos, J. (2011). Public private partnerships: Added value by organizational form or management? Public Administration, 89(4), 1235–1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01877.x

- Stjerne, I. S., Söderlund, J., & Minbaeva, D. (2019). Crossing times: Temporal boundary-spanning practices in interorganizational projects. International Journal of Project Management, 37(2), 347–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.09.004

- Thomson, A. M., & Perry, J. L. (2006). Collaboration processes: Inside the black box. Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00663.x

- Thomson, A. M., Perry, J. L., & Miller, T. K. (2007). Conceptualizing and measuring collaboration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(1), 23–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum036

- Tushman, M. L., & Scanlan, T. J. (1981). Boundary spanning individuals: Their role in information transfer and their antecedents. Academy of Management Journal, 24(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.2307/255842

- Ungureanu, P., Cochis, C., Bertolotti, F., Mattarelli, E., & Scapolan, A. C. (2021). Multiplex boundary work in innovation projects: the role of collaborative spaces for cross-functional and open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24 (3), 984–1010. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-11-2019-0338

- Van Meerkerk, I., & Edelenbos, J. (2014). The effects of boundary spanners on trust and performance of urban governance networks: Findings from survey research on urban development projects in the Netherlands. Policy Sciences, 47(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-013-9181-2

- Van Meerkerk, I., & Edelenbos, J. (2018). Boundary spanners in public management and governance: An interdisciplinary assessment. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786434173

- Vento, I., & Sjöblom, S. (2018). Administrative agencies and the collaborative game: An analysis of the influence of government agencies in collaborative policy implementation. Scandinavian Political Studies, 41(2), 144–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12114

- Verweij, S. (2015). Once the shovel hits the ground: Evaluating the management of complex implementation processes of public-private partnership infrastructure projects with qualitative comparative analysis [PhD thesis]. Erasmus University Rotterdam. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2646785

- Verweij, S., & Van Meerkerk, I. (2020). Do public-private partnerships perform better? A comparative analysis of costs for additional work and reasons for contract changes in Dutch transport infrastructure projects. Transport Policy, 99, 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.09.012

- Walter, A., Auer, M., & Ritter, T. (2006). The impact of network capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation on university spin-off performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(4), 541–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.02.005

- Warsen, R., Nederhand, J., Klijn, E. H., Grotenbreg, S., & Koppenjan, J. (2018). What makes public-private partnerships work? Survey research into the outcomes and the quality of cooperation in PPPs. Public Management Review, 20(8), 1165–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1428415

- Warsen, R., Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. (2019). Mix and match: How contractual and relational conditions are combined in successful public–private partnerships. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(3), 375–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy082

- Warsen, R. (2021). Putting the pieces together: Combining contractual and relational governance for successful public-private partnerships [PhD thesis]. Erasmus University.

- Wilemon, D. (2014). Boundary-spanning as enacted in three organizational functions: New venture management, project management, and product management. In J. Langan-Fox & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Boundary-spanning in organizations: Network, influence, and conflict (pp. 230–250). Routledge.

- Williams, H. W. (2008). Characteristics that distinguish outstanding urban principals. Journal of Management Development, 27(1), 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810840758

- Williams, P. (2002). The competent boundary spanner. Public Administration, 80(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00296

- Williams, P. (2012). Collaboration in public policy and practice: Perspectives on boundary spanners. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89g31

- Yan, S., Hu, B., Liu, G., Ru, X., & Wu, Q. (2020). Top management team boundary-spanning behaviour, bricolage, and business model innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 32(5), 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2019.1677885

- Zheng, J., Roehrich, J. K., & Lewis, M. A. (2008). The dynamics of contractual and relational governance: Evidence from long-term public–private procurement arrangements. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 14(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2008.01.004