Abstract

This paper presents an analytical model for studying “encounters” that take place when ideas for innovation meet institutions (The IIE-model). Our model aims to expand the dichotomous barriers/driver approach in innovation research. Building on the theoretical contributions of studies on institutional logics and change, this model presents a dynamic, institution-based understanding of what happens when innovative ideas meet institutions. Four ideal types of encounters describe the mutual impact of institutions and innovative ideas. This paper aims to contribute to a wider and more nuanced understanding of the dynamics of innovation processes.

Introduction

The stress on the public sector, and especially the local level, to be innovative, is increasing. Local governments, as prominent service providers in Western countries, have been challenged to provide more efficient solutions and enhanced service quality. Meanwhile, there has been a rising interest in determining which factors accelerate or hamper innovation in the public sector. Research in this area has focused on the municipal sector, with a predominance of studies focused on drivers and barriers to innovation (Aagaard, Citation2012; Bason, Citation2007; Clausen et al., Citation2020; De Vries et al., Citation2016). This perspective has its qualities regarding identifying push factors for innovation processes and expected obstacles to such processes, as well as dealing with these obstacles. However, this approach can also reinforce the understanding that innovations are naturally desirable and good, and that organizations can be designed to welcome innovations. Such an approach is less open to the possibility of ideas changing or being rejected during the innovation process, thus reinforcing the common narrative of good ideas penetrating an organization and replacing one or more previous arrangements.

These contestable aspects of this widespread perspective on public innovation are the inspiration for this article. It contributes to this ongoing discussion by presenting a framework for a dynamic, institution-based understanding of what happens when innovative ideas meet public sector institutions. The framework is based on selected and well-established theoretical contributions from institutional theory, institutional logics, and change (Akrich et al., Citation2002a, Citation2002b; Douglas, Citation1986; March & Olsen, Citation2010; Røvik, Citation2007; Scott, Citation1995; Thelen, Citation2002, Citation2004; Thornton et al., Citation2012). By connecting significant contributions to institutional change and idea development, this paper seeks to clarify the relation between institutions and ideas; by offering an analytical model of four different “encounters.” We refer to this as the IIE-model (the Idea Institution Encounter Model). Ideas and institutions are considered as interconnected and as core elements for innovation and change. The key premise is that the generation and practical realization of new ideas provide the basis for future innovations and improvement of institutions (Meijer & Thaens, Citation2021). We explore the “encounters” between innovative ideas and institutions from a theoretical perspective. Moreover, we draw on examples from empirical studies of encounters in local government to illustrate the analytical model. Through this approach, we offer a reflexive framework to clarify the impact ideas and institutions have on each other and the implications of these findings on the dynamics of innovation processes in the public sector.

The article is organized into four sections. Section From barriers and drivers to a dynamic analytical framework introduces the theoretical inspirations for the framework with special focus on Institutions and Ideas. In Section Institutions and ideas, we outline our analytical model. Section When innovative ideas encounter institutions: An analytical model discusses the implications of the IIE-model for scholarly understandings of the dynamics between ideas and institutions. Finally, we highlight aspects that require further research.

From barriers and drivers to a dynamic analytical framework

De Vries’ review article on public innovation demonstrates that antecedents—that is, drivers and barriers—is a common theme and analytical tool in publications on public innovation (De Vries et al., Citation2016). There may be several reasons for this. One is that public innovation is still a “young” research topic, whereas private sector innovation is not. Approaches and patterns of thought, particularly those developed in the earliest years of research on public sector innovation, were inspired by studies on private sector innovation and product innovation, which relied on these concepts for understanding how businesses innovate (Chesbrough, Citation2003; Schumpeter, Citation1934). Another possible reason is that major research projects on public innovation emphasized identifying drivers of and barriers to public innovation (Aagaard, Citation2012; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011a). Other scholars have adopted the same perspective, and they occasionally incorporate their ambition to help public service providers overcome barriers into this perspective (Bason, Citation2007, Citation2018; Cinar et al., Citation2019; Demircioglu & Audretsch, Citation2017; Meijer, Citation2015; Meijer & Thaens, Citation2021). These dynamics are intimately connected to the general policy attention on service innovation and the drive to improve public services in terms of quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. Knowledge of drivers and barriers is employed to assess how different parts of the public sector respond to innovation initiatives, what factors explain why such initiatives are made, and how to develop innovation processes and innovations to improve public services.

One objection to this approach is that factors that serve as drivers in certain contexts can function as barriers in other contexts. Hierarchical leadership is one example of such a factor. Indeed, in its capacity to control resources and information, hierarchical leadership has been identified in several works as essential for making an organization innovative (Bason, Citation2007). When a top-leader is against an innovation, this same factor can become an unsurmountable barrier. Co-creation, much heralded as a driver, can in some instances be a barrier that hampers or halts the innovation process (Torfing & Triantafillou, Citation2016). Barriers will vary substantially depending on the type of innovation and contextual factors (Cinar et al., Citation2019).

This dichotomous perspective reduces the opportunities to ask questions about the idea itself, events that occur during its journey, and changes and adjustments it undergoes along the way. In addition, innovation is rarely one type of innovation: service innovation, organizational innovation, or conceptual innovation (Windrum, Citation2008). New services or new ways of providing services will often demand or cause shifts in organizational models or routines and changes in how people understand and talk about the service area in question. The barriers and drivers are multi-faceted and interconnected and express themselves in various relations during the process which calls for an equally multi-faceted and dynamic analytical framework.

New perspectives have diversified how scholars’ study, speak, and write about public innovation. The translation perspective (Myklebø, Citation2019; Røhnebæk & Lauritzen, Citation2019; Røvik, Citation2016), offers an alternative to Rogers’ (Citation2003) model of diffusion. Rogers illustrates how specific ideas are adopted (in their original form) by different users through communication in a diffusion process (Rogers, Citation2003). The model does not consider whether and how the idea itself can develop and change. The translation perspective offers a more dynamic approach in emphasizing that ideas are adapted to fit the context, hence affecting the innovation process itself. Other contributions highlight how public sector innovation depends not only on organizational fit with organizational values (van Buuren et al., Citation2015), public organizations’ readiness to adopt ideas (Demircioglu & Audretsch, Citation2017; Yun, Citation2020) but also on contextual and demographic variables (Demircioglu, Citation2020; Meijer, Citation2015). These contributions necessitate an institutional approach that can handle the transformation of an idea into an institutionalized practice.

The more comprehensive discussion found in Torfing and Triantafillou (Citation2016) has influenced the development of a contextualized and dynamic perspective on the implementation of innovation. The two authors highlight the three dominating steering paradigms in the public sector—traditional public administration, new public management, and new public governance—and identify different drivers and barriers to innovation between them. Further, they point out that in practical innovation contexts, various combinations between paradigms will occur. Paradigms are systems of institutionalized orientations (Salet, Citation2018) that frame and guide the behavior of actors within a particular setting. With overlapping paradigms, the institutional factors that impact the success rate of innovation processes are likely to appear in a multitude of combinations. Hence, what drives, blocks, or restrains public sector innovation must be expected, from the outset, to vary considerably.

The examples of new theoretical developments mentioned above reflect contextualized perspectives on innovation that emphasize the institutional framing of the innovation process. When innovative ideas enter an organization from the outside or from within, they are received by a set of institutions. This encounter determines whether the idea will develop into an innovation that proves new and useful for the public organization (Grossi et al., Citation2020; Lindholst et al., Citation2023; Osborne & Brown, Citation2011) and to what degree it will shift the institutional framework it is placed within.

Institutions and ideas

Innovation is broadly defined as the implementation of an idea that is perceived as new to the context and results in—more or less disruptive—changes in institutions (Fagerberg et al., Citation2005; Meijer & Thaens, Citation2021; Rogers, Citation2003). Ideas are the core element for change and innovative solutions. The key premise is that the generation and practical realization of new ideas provide the basis for future innovations (Meijer & Thaens, Citation2021). Institutions and ideas are because of this the core concepts of our analytical model where the encounter between institutions and ideas have a mutual effect on each other and may lead to new solutions. Our approach emphasizes the importance of understanding the dynamics between these concepts when dealing with public sector innovation. In this section, we elaborate on a selection of key contributions to institutions and institutional change, and contributions to ideas as an essential component of innovation.

Institutions and institutional change

“Institutions create shadowed places in which nothing can be seen, and no questions asked” (Douglas, Citation1986, p. 69). The citation illustrates the embeddedness and force of institutions in our daily activities. Precisely by expressing the presence of institutions in this way, Douglas raises questions about the nature of institutions and how they change. These questions have led to the development of several definitions that recognize that institutions consist of values, norms, and more or less formalized rules that define and govern practices (Douglas, Citation1986; March & Olsen, Citation2010). This definition allows for institutions to appear in both formal and informal shapes. However, institutions are more difficult to define empirically than theoretically. For both purposes, Scott (Citation1995) identified three “pillars of institutions”: regulative, normative, and cognitive structures and activities (Scott, Citation1995). Other perspectives provide a less rigid view of what institutions are and describe them as both multi-layered and ambiguous (Steinmo, Citation2021).

The above-mentioned contributions are all related to Neo-institutional theory, which “comprises a rejection of rational-actor models, an interest in institutions as independent variables, a turn toward cognitive and cultural explanations and an interest in properties of supra-individual units of analysis that cannot be reduced to aggregations or direct consequences of individuals attributes or motives” (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991, p. 8). In the context of public sector innovation, we apply the neo-institutional perspective to understand and explain institutional stability and change.

Institutions contribute to stability and predictability within organizations. By adopting the perspective of norm based new-institutionalism, March and Olsen explain how institutions remain stable over time. According to this perspective, actors behave according to rules and norms of proper behavior (March & Olsen, Citation2010). Indeed, proponents of this perspective argue that institutions remain stable because actors within them support traditional arrangements and rules instead of pushing for change. Within this perspective, change is often related to exogenous shocks (Thelen, Citation2004; Vos & Voets, Citation2023).

However, other theoretical and empirical contributions widen the scope of sources of institutional change, and argue that institutions are subject to change and evolution due to challenges related to an institution’s surroundings (Douglas, Citation1986; Lewis & Steinmo, Citation2012; Thelen, Citation2004), new contextualization (Salet, Citation2018), and initiatives by actors operating within institutional frames (Hacker et al., Citation2015; Lindholst et al., Citation2023; Thornton et al., Citation2012), and that these may take place simultaneously. This implies that some institutional elements can survive challenges while others are pushed aside or undergo changes both small and large. This dynamic may appear different in various organizational contexts, even if they are subject to a common external or internal impulse for change. An example of this is how the idea complex of new public management has been implemented across countries. In many ways, questions about institutional evolution are about the relation between structure and action.

The development of theories of endogenous change complement theories of exogenous change. Contributions to exogenous change argue for adaptive change and systematic punctuation (Kingdon & Stano, Citation1984), and they are predisposed to evolutionary thinking. The evolutionary approach to institutional change asserts that such changes can occur in a multitude of ways over a long period. New institutions can thus be part of an initiative that incorporates previous institutional elements. Thelen (Citation2002, Citation2004) is an important source of knowledge on the evolutionary approach to institutional change. She acknowledges that there are many forms of change; however, she has identified two forms of change as particularly important: “layering” and “conversion.” Institutional layering is described as introducing amendments to new institutional elements into an existing institutional framework. Occasionally, layering can cause major alterations to an institution’s trajectory. Institutional conversions are described as large and comprehensive changes that can occur when new groups or goals are incorporated into a social system. This can occur, for example, through shifts in a power balance (Thelen, Citation2002, Citation2004). Lewis and Steinmo argue that “an evolutionary framework helps address one of the more vexing problems confronting institutions today; the relationship between ideas, preferences, and institutions” (Lewis & Steinmo, Citation2012, p. 327). This approach integrates ideas into an institutional analysis that is based on the argument that the adoption of certain ideas and preferences will always cause variations. Lewis and Steinmo (Citation2012, p. 338) write, “Internalization of ideas is affected by the ways that ideas are framed, the degree to which they are perceived as a relevant solution to current environmental challenges, and the extent to which they are undermined by negative feedback.”

The institutional logics perspective (Thornton et al., Citation2012) builds on several contributions dealing with the relation between structures, actors, and institutional change. This perspective seeks to overcome dichotomies, such as rational versus non-rational actors, and it includes both exogenous and endogenous change. For this purpose, scholars who adhere to this perspective “examine how action depends on how individuals and organizations are situated within and influenced by the spheres of different institutional orders, each of which represents a unique view of rationality” (Thornton et al., Citation2012, p. 10). The authors develop a typology to understand changes in institutional logics, transformative change, and developmental change. Transformative change refers to situations where an institutional logic is replaced by logics from another field to create new practices, frames, and narratives. Sometimes logics are combined with other logics or are developed into new logics. Developmental change refers to situations where core elements of the institutional logic remain largely unharmed but are still somewhat affected by other logics. However, change is not necessarily the outcome.

What unites the abovementioned approaches is that they concentrate on institutional change, the sources for which can be many, including the inclusion of new groups, goals, or ideas. Generally, the approaches are all about new ideas: the idea that new groups are relevant in certain institutional settings, the idea that the social system should pursue new goals, and the idea that activities should be carried out in new ways. However, this strand of theory fails to theorize what happens to the ideas that lead to institutional change. Do they undergo changes as well? To conceptualize the reverse causal processes—that is, institutions changing ideas—it is necessary to turn to theories that explains how ideas are selected and developed.

Ideas as catalysts for innovation

Lewis and Steinmo (Citation2012, p. 338) write, “Ideas are the product of agent variation at the micro-level, are impacted by selection pressures, and are imperfectly replicated.” According to this definition, ideas can develop both within and outside institutions; however, the development of ideas occurs with new combinations of agents (Yuriev et al., Citation2022). Foregoing the implementation of an idea, a process of selection takes place. During the selection, pressure can be exerted by institutional rules, norms, policy, and logics. The implementation of ideas is “imperfect,” indicating a process of transformation or adaption.

Several studies have discussed how ideas can transform and adapt to new contexts. Translation theory has contributed to scholarly understandings of how ideas undergo transformation. This theory addresses how ideas form, react, and develop when they enter new contexts, and it often emphasizes the role of actors, that is, “translators.” Transformation is perceived as a process of negotiation, where the journey of the idea depends significantly on the institutional values of the actor and the way the idea is communicated (Akrich et al., Citation2002a). Adopting this perspective, Røvik (Citation2007) demonstrates how ideas can travel from one organizational context to another. This translation goes both ways: practices can be translated into ideas (decontextualization), and ideas can be translated into practice (contextualization). An organization’s capability to translate is crucial to this process (Waeraas & Nielsen, Citation2016). Røvik (Citation2007) has presented three modes of how organizations respond to new ideas: the reproducing mode, where the organization copies a practice with few changes; the modifying mode, where the idea is adapted to a new context; and the radical mode, where the idea functions as inspiration for existing logics or solutions. Much of this is embedded in what Scheuer labels “the idea-practice-translation model” (Scheuer, Citation2021). This model includes humans, human actions, and transactions among factors that contribute to translating an (exogenous) idea into a new social and organizational context. This model also includes artifacts and thereby provides a method for theorizing the relevance of material conditions in the translation process.

Ideas are core elements of innovation, and they develop through an innovation process. There is an ongoing debate in the innovation literature over the linearity of the innovation process; starting at one point and following a traceable path (Baregheh et al., Citation2009; Edquist, Citation2010). Toivonen and Tuominen (Citation2009) and Toivonen et al. (Citation2007) have systematized different innovation processes into a model. Using this model, they identified three types of innovation processes. In the first type, the idea emerges, develops, and ends in a market application (project separated from practice). In the second type, an idea emerges and is applied (tested), often followed by further adjustments before implementation (rapid application model). In the third type, changes in service practices lead to the “finding” of an idea, which eventually leads to development (practice-driven model) (Toivonen & Tuominen, Citation2009; Toivonen et al., Citation2007). According to Toivonen and Tuominen (Citation2009), the most common process type is the rapid application type. Several other authors have emphasized that the innovation process is a process of discovery (Van de Ven et al., Citation1999), implying that the initial idea need not necessarily be a stable entity. As the mentioned contributions deal with idea development, rejection does not appear as a relevant category. However, if a model seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of what may happen to an idea when introduced to an institutional setting, then it must include rejection as a possibility. Several studies have identified public sector institutions as reluctant to take on the risk associated with implementing new ideas (Bason, Citation2007; Parsons, Citation2006; Potts, Citation2009; Townsend, Citation2013). The fear of failure causes managers and employees of public organizations to avoid the possible risk associated with new ideas instead of adapting ideas for specific institutional settings. Some scholars argue that changing public servants’ calculations of risk is key to encouraging innovation behavior in the public sector (Bason, Citation2007; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011b; Townsend, Citation2013).

These theoretical approaches to idea development and idea adjustment do not explicitly or systematically thematize institutions as forces that drive such development. However, institutions can be implicitly read out of theoretical contributions. Røvik (Citation2007) emphasizes how ideas affect organizations; Toivonen and Tuominen (Citation2009) argue that institutions have an implicit role in innovation processes. Several studies show a “lock in” of ideas due to public servants’ resistance to risk and innovation. If ideas are affected by factors, such as regulations, norms, and cultural-cognitive perceptions, and, conversely, if the aim of new ideas is to destabilize such institutional pillars, the risk aspect of innovation, then scholars need a framework to capture these processes simultaneously (Osborne & Brown, Citation2011; Townsend, Citation2013). The IIE-model we present in the next section builds on previous research on institutional responses, idea development, and adjustment. The IIE-model offers a framework for conceptualizing encounters between ideas and institutions for future innovations.

When innovative ideas encounter institutions: An analytical model

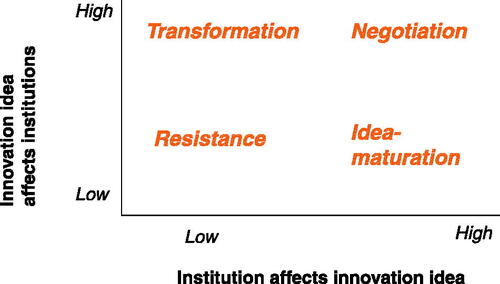

The different strands of theory offer well-developed analytical frameworks for studying institutional change and transformation of ideas. Considered as elements of a wider context, they motivate and underpin a comprehensive approach to innovation, which seek to grasp the reflexivity between ideas and institutions. Contributions to innovation processes have traditionally focused on factors hampering or driving processes forward. In this section, we offer an alternative and reflexive model of the “encounters” that play out when ideas and institutions meet, how encounters impact both ideas and institutions, and what innovations such encounters may lead to. Based on selected and well-established contributions referred to in the previous section, we have developed a model founded on the observation that ideas as well as institutions can undergo changes when aiming for innovation. We refer to this model as the IIE-model (the Idea Institution Encounter Model). We illustrate this as change along a high–low dimension and identify four “encounters.” The encounters should, however, not be regarded as closed categories. Rather, they function as devices for structuring the basic idea of dynamic encounters. Nevertheless, in each corner of the figure we have placed labels on the encounters; describing the various relations that can occur between idea and institution. The labels are as follows: resistance, idea maturation, transformation, and negotiations ().

Resistance

Encounters where the innovative idea has a low impact on the institution, we have labeled Resistance. In these situations, the innovative idea does not change, and the institution is stable or to a small degree affected by the innovative idea. According to March and Olsen (Citation2010), strong institutional norms and routines maintain stability over time and are resistant to transient ideas. In this context, those who represent institutional values are not motivated to change an idea to conform with a solution that fits the institution. Several studies on political innovations in municipalities illustrate the resistance encounter. Torfing and Triantafillou (Citation2016) argues that it can be painful for politicians to adopt new roles, which often enables entrenched perceptions of roles to persist (Torfing et al., Citation2019). This conclusion is also supported by the findings of Sønderskov, who studied politicians in Norwegian municipalities who sought to deepen interactions with citizens. Her findings demonstrate that although politicians desire to achieve closer dialogue with citizens, institutional framings and perceptions of roles make it easier to develop dialogue in-house with other politicians and administrations (Sønderskov, Citation2019). Politicians are embedded within and affected by the institutional norms and rules of traditional representative democracy, which leads to resistance when introducing ideas meant to promote the interactive role of politicians. This is in line with several studies arguing that public authorities and servants fear that new ideas may reduce the reliability of task performance. This often leads to resistance or a “risk-minimizing approach” (Osborne & Brown, Citation2011; Townsend, Citation2013; van Buuren et al., Citation2015).

Other examples of resistance are situations where ideas are implemented due to exogenous shocks but fall back into “business as usual” after a situation normalizes. Kingdon and Stano (Citation1984) describes such cases using the term “policy windows.” According to Kingdon, shocks can be considered windows of opportunity that close after a short period. The case study by Nilssen and Hanssen (Citation2022) on the innovation processes in two municipalities in Denmark and Netherlands demonstrated that external shocks often lead to new paths that last only for a limited time until the idea has been abandoned (Nilssen & Hanssen, Citation2022). This is also in line with the study of Eshuis and Gerrits on adaptive governance (Eshuis & Gerrits, Citation2021).

Resistance as encounter conceptualizes that ideas introduced to strongly institutionalized contexts can be rejected. Rejection may be considered as an innovation failure; however, it can also be interpreted as a mechanism of critical assessment and an active selection of ideas.

Idea maturation

In the second type of encounter, which we refer to as idea maturation, the idea has a low impact on the institution. In these encounters, it is the institution that affects the innovative idea, and the idea affects the institution to a lesser extent. The innovative idea can either originate from within an organization or from outside, and it is developed based on what is deemed necessary and possible in the particular organizational context. According to the translation perspective, ideas can be adjusted or changed, or they can be used to generate entirely new and autonomous ideas. Røvik (Citation2007) refers to such practices as the modifying mode, and in this mode, practices can be developed into new ideas. A modifying mode is also in line with what Toivonen and Tuominen (Citation2009) describe as the most observed type of innovation process: rapid application. In this innovation process, after an idea emerges, it is applied (tested) and adjusted before being implemented. Thornton et al. (Citation2012) would likely label this as developmental change; in developmental change, the institutional logic remains largely intact but is still affected by other logics. In Thelen’s conceptualization (Thelen, Citation2004), this resembles an evolutionary process due to challenges from the surroundings and initiative from actors operating within the institutional frames. Most importantly, it is the institutional setting that determines how an idea progress (Eshuis & Gerrits, Citation2021; Hacker et al., Citation2015; Salet, Citation2018; Thelen, Citation2004).

Several studies of employee-driven innovation in municipalities give examples of Idea maturation. Based on existing institutional practices, employees develop new ideas to improve services and processes, including small incremental changes that are being tested, adjusted, and implemented. In these situations, ideas are developed inside the organization, where the idea is adjusted and adapted to fit institutional frames (Engen, Citation2016; Holmen, Citation2020a; Holmen & Ringholm, Citation2019; Lindland, 2019; Yuriev et al., Citation2022). Other studies of innovation in municipalities show how ideas are adopted from other municipalities, translated, and adjusted. Municipalities are inspired and intrigued by experiences outside the organization. This often implies “stealing” ideas and testing solutions in new contexts. Thus, solutions travel between municipalities. Ideas, concepts, and models for innovation are further transformed by encounters with resilient and stable institutional settings within municipalities (Holmen, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Røhnebæk & Lauritzen, Citation2019). These encounters lead to small changes in ideas, which at their core are regarded as useful and “possible to implement” in the institutional context (Osborne & Brown, Citation2011; van Buuren et al., Citation2015).

Transformation

Transformation refers to a type of encounters where innovative ideas have an impact on the institution. Compared to idea maturation, transformative change implies a stronger impact on the institution, in the form of adjustments in the existing institutional logics and praxis. Transformation can take place through new contextualization (Salet, Citation2018), transformative change (Lounsbury & Crumley, Citation2007; Thornton et al., Citation2012), or evolution (Lewis & Steinmo, Citation2012; Thelen, Citation2002, Citation2004). In these encounters, the innovative idea is implemented, and institutional patterns change because of the impact of the idea. The implementation takes place without notable changes to the idea itself. In line with Røvik, this can be understood as directly incorporating ideas into a new context or as a mode of reproduction where ideas are copied from one context to another (Røvik, Citation2016). This can also be referred to as a mode of reproduction or practice-driven model where concepts, methods, and “recipes” travel from one organization to another and are implemented in their original form in a new context (Røvik, Citation2016; Toivonen et al., Citation2007). Several empirical contributions illustrate the encounter of transformation in local government. The implementation of specific measuring tools derived from new public management reforms, management recipes (like LEAN), and specific process models for innovation are significant examples of transformation (Morris & Lancaster, Citation2006; Wæraas & Byrkjeflot, Citation2012; Waeraas & Nielsen, Citation2016). Sørensen et al. also argue through their studies of municipalities, that adopting innovative concepts in new and different circumstances is important for overcoming standard objections, such as “we do not need any changes.” It is also an important step for spreading innovative practices (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011a).

Negotiations

Negotiations characterize the last category of encounters in our model. During this type of encounter, both the innovative idea and institutions change. Negotiations adopt features from translation theory and the process of negotiating between values and logics (Akrich et al., Citation2002b). Røvik’s (Citation2007) understanding of the radical mode and Toivonen and Tuominen’s (Citation2009) understanding of the rapid application model of innovation also offer insight regarding this type of encounter. Negotiations occur in situations where existing institutional logics and innovative ideas challenge each other and both are subject to change.

Several studies have reported findings regarding negotiations between ideas and institutions. Hansen et al. (Citation2022) provide an interesting contribution by analyzing how social entrepreneurs outside of the municipality can spur and contribute to public sector innovation. This study illustrates how initiatives by multi-agent collaborative arrangements (PINSIS) “somehow forces the public sector and civil society to enter each other’s domains and to explore and understand what kind of logics are at stake” (Hansen et al., Citation2022). This motivates formal collaborators to change their mode of operating and to invent new modes. van Buuren et al. (Citation2015, p. 694) similarly argue that negotiation through auxiliary arrangements contributes to solving misfits between innovation and organizational values. Negotiation is most present in public reforms, where ideas for solutions stem from national programs that invite engagement from municipalities to adjust the idea as well as their practice. Myklebø (Citation2019) and Røhnebæk and Lauritzen (Citation2019) also illustrate negotiation as an encounter by applying the translation perspective. In Røhnebæk and Lauritzen’s study on implementing national reform programs and Myklebø’s study on implementing widespread ideas in municipalities, the authors unfold the bargain between the reforming idea and institutionalized practice. This leads to a negotiation where both the initial idea, the institutional structures, and norms change (Myklebø, Citation2019; Røhnebæk & Lauritzen, Citation2019).

summarizes the key points from the framework informing our IIE-model.

Table 1. Key Points from the Framework Informing the IIE-Model.

Discussion and contribution

In the final section, we will highlight aspects related to the relevance of the IIE-model for praxis and research on innovation. This is the first attempt to form a comprehensive theory of the dynamic between ideas and institutional framings in public sector innovation, and therefore, the IIE-model can still benefit from further development.

Theoretical and managerial implications

The IIE-model contributes to several important discussions. Firstly: to understand institutional change and public sector innovations, it is necessary to explore and understand both ideas and institutions as dynamic elements. By combining perspectives on the translation of ideas and changes in institutions and their logics, this paper offers an interpretation of innovations as an outcome of the interaction between ideas and institutions. This approach to innovation processes is an alternative to the dichotomous approach to public sector innovation that is often found in studies on barriers and drivers (Bason, Citation2007; Clausen et al., Citation2020; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011b). For managerial purposes, the IIE-model offers a tool for understanding ongoing innovation processes. Bearing the possible tensions between idea and institution in mind can provide a broader understanding of encounters between idea and organizational features, and in turn, explain resistance and the level of engagement in an organization. Hence, the model offers a framework for public sector managers to understand the dynamics of innovation processes as it shows that the encounter between idea and institution played out at a given time might be different at another point in time. Such knowledge could lead to the well-known response of “this had been turned down before” to innovative ideas, being used more sparsely. And conversely: contemplating the institutional framework when thinking of adopting an innovative idea into a new setting.

The second discussion concerns the question of innovation diffusion. In general, the public sector is under a marching order to implement innovations and enhance their innovation potential. Policy initiatives instigated by central authorities often refer to innovation strategies, such as “stealing” ideas, communicating best practices, and establishing platforms for sharing, dispersing, and facilitating successful solutions in new contexts. That is, there is an underlying assumption that innovations can be transplanted rather frictionlessly from one organization to another, or at least between organizations that share important structural characteristics, such as municipal organizations. The IIE-model suggests that encounters between identical or at least very similar ideas and institutions can lead to successful innovation, a different form of innovation, or nothing, depending on the context. Many public sector organizations have experienced this variety of outcomes. This is much in line with translation perspectives, which emphasize how ideas are translated into a particular institutional context (Akrich et al., Citation2002a, Citation2002b; Røvik, Citation2007). For managerial purposes, these perspectives are important for public organizations initiating new ideas, as they make practitioners of innovation more aware of specific institutional contexts. A “successful innovation,” understood as a transformation according to the initial idea, in one context, may require negotiation or translation to be implemented in another context. Idea resistance can also be a tool for identifying ideas not suitable for an organization, hence avoiding a minor or major catastrophe. Within this reaction, there is an implicit recommendation to practitioners of not having a prejudiced conception of what the drivers and barriers are in innovation processes, but rather that circumstances vary from context to context and that one should be open-minded regarding institution-based reactions to an idea.

Avenues for future studies

The IIE-model suggests that encounters can develop over time because encounters between ideas and institutions are dynamic. In line with Van de Ven et al. (Citation1999), we understand the innovation process as a process of discovery. This indicates that neither the initial idea nor the institution is necessarily a stable entity. Therefore, an “encounter” at one point in time may develop into another “encounter” at a different point in time. Resistance at one point may mature and create space for idea maturation to occur at a later stage. When considering that encounters are dynamic, a barrier at one stage of an encounter may be a significant driver for implementing an innovative idea at a later stage. This supports interpretations of innovation as a multidimensional process that contains several shifts rather than as a single idea or innovation. These reflections are relevant contributions to the debate on the linearity of the innovation process. It is also an invitation to develop this model further so that it can capture the time dimension of the innovation process.

A possibly even more extensive discussion relates to innovation and change in public organizations and the connection to the three dominant steering paradigms in the public sector: public administration, new public management, and new public governance. This typology is used as an analytical framework to identify drivers of and barriers to the innovation process. Torfing and Triantafillou, however, emphasize that the three paradigms are in practice strongly intertwined and occur in many different combinations. This means that in innovation processes as well as the ordinary day-to-day activities, various combinations of the paradigms will occur (Torfing & Triantafillou, Citation2016). The IIE-model enables us to identify the impact that ideas and institutionalized values associated with any paradigm will have on one another when they meet. The IIE-model could, however, also be useful for identifying and investigating the strengths and weaknesses that new relationships between formal and informal institutions display in their encounters with the new ideas. This capability of the model is possible because it is a generic model that surpasses the categorization capacities of the three paradigms. Such identification, we believe, is to a large degree an empirical task that possibly demands a substantial number of empirical studies. Nevertheless, studies of this kind could also be one place to look for indications of the next steering paradigm.

Conclusion

Although public sector innovation and knowledge of barriers and drivers have been explored thoroughly in existing studies, few scholars have attempted to explore the interplay between ideas and institutions. The fact that institutions and ideas impact each other in a mutual relationship leads to a diversity of encounters that affect possible innovations. Institutional pillars and logics are building blocks that leave deep traces and create different conditions for ideas to develop or die. The pressure on public organizations to be innovative also provides a “window of opportunity” for ideas to travel and be tested against various institutional contexts, thus challenging the notion of there being fixed barriers and drivers of innovation.

The IIE-model presented in this article provides a new, dynamic framework for describing, understanding, and analyzing the innovation process by considering both institutional responses to ideas and various ways that ideas develop when introduced to different institutional settings. We also hope to inspire further reflections on how to capture the development of such relationships over time. This would be both a useful analytical framework and research tool for empirical studies. It would also benefit practitioners as a frame of reference in managing their processes of innovation. The IIE-model establishes a foundation for further development of the study of encounters between ideas and institutions. This model enables scholars to better understand the patterns of innovation in public institutions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ann Karin Tennås Holmen

Ann Karin Tennås Holmen is an associate professor of political science at The University of Stavanger, Norway. Her research covers the area of public sector innovation, co-creation, network governance and regional innovation.

Toril Ringholm

Toril Ringholm is a professor of public planning at UiT – The Arctic University of Norway. Her research interest is public sector innovation, innovative forms of participation in planning processes and strategic planning.

References

- Aagaard, P. (2012). Drivers and barriers of public innovation in crime prevention. The Innovation Journal, 17(1), 2.

- Akrich, M., Callon, M., Latour, B., & Monaghan, A. (2002a). The key to success in innovation part I: The art of interessement. International Journal of Innovation Management, 6(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919602000550

- Akrich, M., Callon, M., Latour, B., & Monaghan, A. (2002b). The key to success in innovation part II: The art of choosing good spokespersons. International Journal of Innovation Management, 6(2), 207–225. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919602000562

- Baregheh, A., Rowley, J., & Sambrook, S. (2009). Towards a multidisciplinary definition of innovation. Management Decision, 47(8), 1323–1339. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740910984578

- Bason, C. (2007). Velfærdsinnovation: ledelse af nytænkning i den offentlige sektor. København: Børsens Forlag.

- Bason, C. (2018). Leading public sector innovation: Co-creating for a better society. Policy Press.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press.

- Cinar, E., Trott, P., & Simms, C. (2019). A systematic review of barriers to public sector innovation process. Public Management Review, 21(2), 264–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1473477

- Clausen, T. H., Demircioglu, M. A., & Alsos, G. A. (2020). Intensity of innovation in public sector organizations: The role of push and pull factors. Public Administration, 98(1), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12617

- De Vries, H., Bekkers, V., & Tummers, L. (2016). Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Administration, 94(1), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12209

- Demircioglu, M. A. (2020). The effects of organizational and demographic context for innovation implementation in public organizations. Public Management Review, 22(12), 1852–1875. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1668467

- Demircioglu, M. A., & Audretsch, D. B. (2017). Conditions for innovation in public sector organizations. Research Policy, 46(9), 1681–1691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.08.004

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In The new institutionalism in organizational analysis, 1–38. University of Chicago Press.

- Douglas, M. (1986). How institutions think. Syracuse University Press.

- Edquist, C. (2010). Systems of innovation perspectives and challenges. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 2(3), 14–45.

- Engen, M. (2016). Frontline employees as participants in service innovation processes: Innovation by weaving (PhD) Lillehammer Uiversity Collage, Lillehammer.

- Eshuis, J., & Gerrits, L. (2021). The limited transformational power of adaptive governance: A study of institutionalization and materialization of adaptive governance. Public Management Review, 23(2), 276–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1679232

- Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D. C., & Nelson, R. R. (2005). The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Grossi, G., Dobija, D., & Strzelczyk, W. (2020). The impact of competing institutional pressures and logics on the use of performance measurement in hybrid universities. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(4), 818–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1684328

- Hacker, J. S., Pierson, P., & Thelen, K. (2015). Drift and conversion: Hidden faces of institutional change. In Advances in comparative-historical analysis (pp. 180–208). Cambridge University Press.

- Hansen, A. V., Fuglsang, L., Gallouj, F., & Scupola, A. (2022). Social entrepreneurs as change makers: expanding public service networks for social innovation. Public Management Review, 24(10), 1632–1651. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1916065

- Holmen, A. K. T. (2020a). 5. Innovasjon som nytt styringsparadigme i en kommunal hverdag? (pp. 97–113). Universitetsforlaget.

- Holmen, A. K. T. (2020b). Planning for innovation as innovative planning? Innovation in public planning (pp. 189–203). Springer.

- Holmen, A. K. T., & Ringholm, T. (Eds.). (2019). Innovasjon møter kommune. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Kingdon, J. W., & Stano, E. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little.

- Lewis, O. A., & Steinmo, S. (2012). How institutions evolve: Evolutionary theory and institutional change. Polity, 44(3), 314–339. https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2012.10

- Lindholst, A. C., Hansen, M. B., & Nielsen, J. A. (2023). Private contractors as a source for organizational learning: Evidence from Scandinavian municipalities. Public Performance & Management Review, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2023.2172738

- Lindland (2019). Realisert ledelse av medarbeiderdrevet innovasjon i en kommunal kontekst. In A. K. T. Holmen, & T. Ringholm (Eds.), Innovasjon møter kommune (pp. 119–133). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Lounsbury, M., & Crumley, E. T. (2007). New practice creation: An institutional perspective on innovation. Organization Studies, 28(7), 993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078111

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (2010). Rediscovering institutions. Simon and Schuster.

- Meijer, A. (2015). E-governance innovation: Barriers and strategies. Government Information Quarterly, 32(2), 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.01.001

- Meijer, A., & Thaens, M. (2021). The dark side of public innovation. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(1), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2020.1782954

- Morris, T., & Lancaster, Z. (2006). Translating management ideas. Organization Studies, 27(2), 207–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605057667

- Myklebø, S. (2019). Når ideen om arbeidsretting møter integreringsfeltets logikker. In T. Ringholm & A. K. T. Holmen (Eds.), Innovasjon møter kommune. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Nilssen, M., & Hanssen, G. S. (2022). Institutional innovation for more involving urban transformations: Comparing Danish and Dutch experiences. Cities, 131, 103845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103845

- Osborne, S. P., & Brown, L. (2011). Innovation, public policy and public services delivery in the UK. The word that would be king? Public Administration, 89(4), 1335–1350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01932.x

- Parsons, W. (2006). Innovation in the public sector: Spare tyres and fourths plinths. Innovation Journal, 11(2), 1–10.

- Potts, J. (2009). The curious problem of too much efficiency and not enough waste and failure. Innovation, 11(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.5172/impp.453.11.1.34

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press.

- Røhnebæk, M., & Lauritzen, T. (2019). Kommunal innovasjon som oversettelse [Municipal innovation as translation] (pp. 193–208). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Røvik, K. A. (2007). Trender og translasjoner: ideer som former det 21. Århundrets Organisasjon, Universitetsforl.

- Røvik, K. A. (2016). Knowledge transfer as translation: Review and elements of an instrumental theory. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(3), 290–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12097

- Salet, W. (2018). Public norms and aspirations: The turn to institutions in action. Routledge.

- Scheuer, J. D. (2021). How ideas move: Theories and models of translation in organizations. Routledge.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard University Press.

- Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Sage Publications.

- Sønderskov, M. (2019). Councillors' attitude to citizen participation in policymaking as a driver of, and barrier to, democratic innovation. The Innovation Journal, 25(3), 1–20.

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2011a). Enhancing collaborative innovation in the public sector. Administration & Society, 43(8), 842–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399711418768

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2011b). Samarbejdsdrevet innovation i den offentlige sektor. Jurist-og Økonomforbundet.

- Steinmo, S. (2021). Historical institutionalism the cognitive foundations of cooperation. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(5), 1140–1159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1694548

- Thelen, K. (2002). The political economy of business and labor in the developed democracies. In Political science: The state of the discipline (pp. 371–403). New York, NY: APSA.

- Thelen, K. (2004). How institutions evolve. Cambridge Books.

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure and process. Oxford University Press.

- Toivonen, M., & Tuominen, T. (2009). Emergence of innovation in services. The Service Industries Journal, 29(7), 887–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060902749492

- Toivonen, M., Tuominen, T., & Brax, S. (2007). Innovation process interlinked with the process of service delivery: A management challenge in KIBS. Economies et Sociétés, 41(3), 355.

- Torfing, J., & Triantafillou, P. (2016). Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance. Cambridge University Press.

- Torfing, J., Sørensen, E., & Røiseland, A. (2019). Transforming the public sector into an arena for co-creation: Barriers, drivers, benefits, and ways forward. Administration & Society, 51(5), 795–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716680057

- Townsend, W. (2013). Innovation and the perception of risk in the public sector. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 5(3), 21–35.

- van Buuren, A., Eshuis, J., & Bressers, N. (2015). The governance of innovation in Dutch regional water management: Organizing fit between organizational values and innovative concepts. Public Management Review, 17(5), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.841457

- Van de Ven, A. H., Polley, D. E., Garud, R., & Venkataraman, S. (1999). The innovation journey. Oxford University Press.

- Vos, D., & Voets, J. (2023). Examining municipalities’ choices of service delivery modes through the lens of historical institutionalism. Public Management Review, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2174587

- Wæraas, A., & Byrkjeflot, H. (2012). Public sector organizations and reputation management: Five problems. International Public Management Journal, 15(2), 186–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2012.702590

- Waeraas, A., & Nielsen, J. A. (2016). Translation theory ‘translated’: Three perspectives on translation in organizational research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(3), 236–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12092

- Windrum, P. (2008). Innovation and entrepreneurship in public services. In Innovation in public sector services: Entrepreneurship, creativity and management (pp. 3–20). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Yun, C. (2020). Early innovation adoption: Effects of performance-based motivation and organizational characteristics. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(4), 790–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1666725

- Yuriev, A., Boiral, O., & Talbot, D. (2022). Is there a place for employee-driven pro-environmental innovations? The case of public organizations. Public Management Review, 24(9), 1383–1410. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1900350