Abstract

The public administration (PA) discipline recognizes public sector organizations’ need to manage tensions and competing pressures, especially in the context of turbulence and complexity. But it but has only recently considered organizational ambidexterity (OA) as a capability that allows this. This study reports bibliometric reviews and content analyses concerning OA. It identifies implications for PA and research gaps. Despite OA’s appeal in addressing PA challenges, an understanding of how the PA context might influence OA applicability is just emerging. We describe a PA research agenda that includes OA and the conditions promoting it.

Introduction

Public administrations (PAs) are increasingly expected to manage inherent tensions in their service delivery (Qiu & Chreim, Citation2021). They are expected to use resources efficiently while innovating in response to changing social and individual circumstances and to manage citizen participation, while also fulfilling legally mandated performance requirements. Consequently, over recent years, there has been a growing interest in the concept of organizational ambidexterity (OA) and how it relates to PA. This is the capability to combine exploration (which includes more enterprising, trial-and-error, boundary-traversing, risk-taking, and other innovative ‘variance-increasing’ behaviors to absorb and adapt to changing external circumstances) with exploitation (which includes more conservative, efficient, risk-averse, and other ‘variance decreasing’ behaviors) to use existing resources efficiently (Cannaerts et al., Citation2020, p. 691). Effectively combining these two capabilities lies at the core of OA. For instance, an ambidextrous organization can develop innovations through effective exploration, then deploy them at scale through exploitation; or it can exploit organizational processes to source ideas for exploration.

OA is well established in the management discipline, and it is becoming more established in PA, with substantial scope for knowledge transfer between the two. Although the disciplines have diverged over the last 40 years, PA and organization studies share common roots (Vogel, Citation2014, p. 383), and many organizations have some degree of publicness (Antonsen & Jørgensen, Citation1997; Bozeman, Citation1987). This cross-boundary study seeks to strengthen and highlight the relevance of OA to PA and examine its potential to address distinct PA dilemmas (Bozeman, Citation1987).

Studies of OA stem from March’s (Citation1991) seminal paper, which argued that organizations had to make tradeoffs or choose between the capacities to explore new knowledge (innovation) and exploit their operations’ existing knowledge (optimization) as doing both was very difficult. But Tushman and O’Reilly’s (Citation1996) study provided the genesis for recent research into ambidexterity by concluding that choosing might not be necessary and that, instead, the two practices can interact and even mutually reinforce each other. Thus, the capacities to both innovate (explore) and optimize existing resources (exploit) can correlate positively rather than negatively (e.g. Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; Gieske et al., 2019). Studies show that the interaction of exploration and exploitation supports long-run performance in both public and private organizations (Gieske et al., Citation2020; Junni et al., Citation2013, Plimmer et al. Citation2017). There are several strategies to achieve OA.

Early work in OA was primarily concerned with differentiation or structural ambidexterity, where different business units explore or exploit depending on their role (e.g. Tushman & O’Reilly, Citation1996), and temporal ambidexterity, where organizations cycled between explorative and exploiting activities sequentially (Adler et al., Citation1999). These two strategies were supplemented by Gibson and Birkinshaw (Citation2004), who emphasized integration of exploration and exploitation through contextual ambidexterity (p. 209) (an organization creating a context that supports ambidextrous behavior, often at the job level). Thus, there are strategic choices to be made when deciding how to achieve OA (i.e. structural, temporal, contextual). Within PA, there are no pure ambidextrous designs (Cannaerts et al., Citation2020). Although contextual ambidexterity at the personal or business unit levels is often studied as a method of addressing competing goals, tensions, and paradoxes, within PA these frequently lie within tasks rather than as choices between tasks (Gieske et al., Citation2020; Plimmer et al., Citation2017). For instance, a prison officer might explore options for rehabilitation but remain within public security requirements; and a medical doctor might explore novel treatment options but deploy them within existing medical systems. This study examines OA as a means to address the dilemmas that arise in PA from the paradoxes, tensions, and competing goals that pervade it (Backhaus et al., Citation2022, Dudau et al., Citation2018).

Ambidexterity and the public sector

Public and private organizations share many similarities, but public organizations have different opportunities (such as regulatory powers) and constraints (such as public tolerance for risk or cost cutting). They need to heed their authorizing environments, which may constrain options for value creation (Ansell et al., Citation2020; Moore, Citation1995). Their services may be either in a highly transparent ‘fish bowl’ or highly secretive (Meijer et al., Citation2018).

Public sector organizations have distinct internal features, in both their staff and organization. For example, public service motivation (PSM), which concerns motives “grounded in the public interest in order to serve society” (Ritz et al., Citation2016, p. 9), could reveal exploratory behavior such as workarounds, rule bending, and adaptions to better serve the public (Ritz et al., Citation2016). In contrast, red tape, which concerns unnecessary and burdensome rules and regulations, could inhibit the exploratory behavior needed to source new ideas, as well as the ability to exploit such ideas well. There are also distinctive characteristics to leadership in the public service (Vogel & Werkmeister, Citation2020). How these PA-context issues impact the achievement of OA remains largely unexplored.

Contradictory goals are “inherent in the activities of any typical public-sector organization” (Parikh & Bhatnagar, Citation2018, p.95), creating a challenge for managers (Van der Wal, Citation2017, p.65). Such managers are urged to innovate, and also be efficient and lower cost (Gieske et al., 2019, p. 341). They are also urged to maintain long-term ‘social value’ goals (societal wellbeing, environmental sustainability, and so forth) and respond to short-term political processes (Van der Wal, Citation2017, p. 65; cf. Donadelli & Lodge, Citation2019). These tensions occur in private organizations too, but they have high salience in hybrid and PA organizations. These tensions often require choices between exploratory and exploitative actions. For example, the multiplicity of stakeholders identified by Van der Wal (Citation2017, p. 68) include those who demand close involvement and co-design opportunities (requiring exploratory behaviors and capabilities) and those concerned only with efficient delivery of core services (requiring exploitative skills). Thus, the capability to manage tensions in general may develop from the ability to manage the specific tension between exploration and exploitation.

Other tensions that public sector agencies contend with include serving diverse populations with conflicting interests, trying to achieve different types of value simultaneously (such as economic, social and cultural, political, and environmental concerns), balancing technical and political concerns (Bennington, Citation2011; Smith, Citation2014), and integrating outcomes, trust and legitimacy, service quality, and value for money to create public value (Faulkner & Kaufman, Citation2018). OA may provide the capability to manage these tensions.

Reforms during the new public management (NPM) era flattened the tensions associated with multiple stakeholders by wishing one polarity or stakeholder group away (Dunleavy et al., Citation2005) or treating public services as singular products rather than services carrying inherent tensions. In the post-NPM era, models such as public service value ecosystems, as well as the ‘co’ concepts of design, production, and creation often lack precise definition (Dudau et al., Citation2019; Kinder & Stenvall, Citation2023). It is unclear whether they actually create value or whether apparent successes are replicable or scalable (Dudau et al., Citation2019), i.e. whether these exploratory behaviors are capable of exploitation. Volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) problems add further complexity.

An ‘ambidexterity lens’ potentially helps address these issues. Exploration, or variance increasing, provides the means to co-create, learn, and adapt from engagement with individuals and communities. In contrast, exploitation, or variance reduction, allows for consistency and fairness through regulatory adherence and consistency in deploying innovations to promote value in broader society (and within societal norms). If successfully applied, exploitation may lead to more effective expenditure with less waste. OA provides a useful lens for examining intra-organizational capacity to manage across these differing levels and goals.

Several rigorous studies have examined OA and demonstrated its potential for PA, spanning antecedents at different organizational levels, from the role of top management teams (Smith & Umans, Citation2015; Umans et al., Citation2020) and the configuration of organizational design (Cannaerts et al., Citation2016; Cannaerts et al., 2020) to the use of formal and informal processes, leadership, culture, and human resource management (HRM) practices (Gieske, Duijn, et al., 2019; Gieske et al., Citation2020; Gieske, van Meerkerk, et al., 2019). Other studies have examined the role of contextual factors (moderators). For instance, OA seems most effective in service organizations (Junni et al., Citation2013), which characterizes many PA organizations. It is also most effective in dynamic environments, as these provide competitive forces that elicit ambidexterity (Simsek, Citation2009). Meanwhile, PA environments are dynamic in non-market ways, driven more by citizen and stakeholder forces or political ‘marketplaces’ (Donadelli & Lodge, Citation2019; Wynen et al., Citation2017). PA drivers of OA potentially differ in both intensity and style compared with drivers of OA in organizations with purely private goals. Whether and how this shapes OA is largely unknown.

While initial PA findings are significant, more research on contexts, antecedents, and consequences of OA is needed. Few studies consider OA as a capability that would allow post-NPM models of public administration to be operationalized or to manage specific PA tensions and paradoxes (Page et al., Citation2021). Many studies in the general management literature potentially apply to PA, and OA studies in PA contexts are oft-times published in the general management literature. Hence a stronger integration of the two literatures potentially enriches OA studies and both PA and general management practices.

Bibliometric analysis of co-citation patterns provides a means of integrating these two strands of OA literature as it summarizes large quantities of bibliometric data to identify the intellectual structure and emerging trends of a research field. By identifying the most influential publications, thematic clusters, areas of consensus, and dissensus, research gaps can be identified, as can ideas that have not yet been applied to the PA context but that may well be fruitful.

This study makes three contributions to the literature: it systematically identifies the known body of literature on OA in public sector environments; it examines and compares constructs from the general management literature that may be applicable to the PA environment; and it identifies a future research agenda. Accordingly, our research questions are:

RQ1: What is the intellectual structure of the OA field?

RQ2: What are the current research frontiers of OA in public administration?

RQ3 What is a future OA agenda for PA researchers?

Research strategy

We first perform bibliometric analyses to systematically examine the general management literature concerning OA (RQ1). We then identify key findings and frontiers from the PA literature (RQ2). In the discussion, we identify a future research agenda (RQ3).

Eligibility criteria

Data used in this study were obtained by searching the abstract and citation Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases. The time frame for the search was from 1996, the year of Tushman and O’Reilly’s seminal article. The last search was January 2023.

Studies were then included if they met the following criteria:

Field – Business, management and public administration topic – studies should contain organ* AND ambidext* as author keywords in title or abstract.

Year of publication – Studies published in the period from 1 January 1996 to 31 January 2023 were retrieved.

Language – English only.

Publication status – International peer reviewed journal articles and books from established publishers.

In all, 479 original articles from Scopus were screened, with 177 removed as duplicates, irrelevant, incorrect, or missing. This process was repeated with WoS yielding an additional 231 unique and relevant articles. In total, 533 studies were found, with 40 being PA articles (either published in PA journals or undertaken in PA settings). The sample selection process is summarized in .

Table 1. Sample Selection Process for Bibliometric Analysis.

As robustness checks we first examined the impact of choosing to use the search terms (“organ*” and “ambidext*”) as author key words, rather than the more general “topic” of ambidexterity in the title. As we expected, this approach limited the number of papers. Re-running the analysis using topic rather than author key word as the locus of the search terms dramatically increased the number of papers (to around 2,000), but close examination revealed a large majority of these to be only tangentially related to the topic. We concluded that our decision to limit search terms to author key words alone is justified both in terms of reflecting authorial intent, and in terms of the specificity of the search results. We also ran a search for OA within Public Administration in Google Scholar. While we chose the established bibliometric approaches of using Web of Science or Scopus because of their tougher criteria for inclusion, Google Scholar provides more articles with more citations. This, however, reflects its lack of discrimination in terms of where citations were made (and hence quality), and some concerns that it has erroneous records (Gusenbauer, Citation2019).

This was reflected in our robustness check. While this showed 12,000 results, a review of the 50 results judged most relevant by Google Scholar showed that only 11 were in peer reviewed journals and covered both organizational ambidexterity and public administration. All 11 were already in our database. This confirms that our more rigorous search criteria using Scopus and Web of Science avoids the large majority of irrelevant and poor-quality studies.

This systematic review used the bibliometric techniques of co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling to understand the relationships between published papers, attempting to reveal the underlying commonalities among the reviewed research (e.g. Apriliyanti & Alon, Citation2017; Marsilio et al., Citation2011; Vogel & Masal, Citation2015). Measuring and visualizing the co-citation patterns helps identify key research streams and, when supplemented by thematic analysis of papers’ content, helps clarify research findings and gaps.

Both HistCite and VosViewer were used to implement bibliometric techniques. Co-citation analysis (HistCite) performs bibliometric analysis by providing the most important articles, journals, authors, institutions, and countries in terms of various metrics, such as total local citations (LCS) (the number of times a retrieved article is cited by others within the retrieved set of articles) or total global citations (GCS) (the number of times a retrieved publication is cited in the whole database). HistCite was used for RQ1, as it identifies the underlying structure of how a research discipline has emerged over time, based on the most highly cited papers. VosViewer was used for RQ2, as it has been found to be better at tracing more recent publications (Andersen, Citation2019; Vogel & Masal, Citation2015).

RQ1: What is the intellectual structure of the OA field?

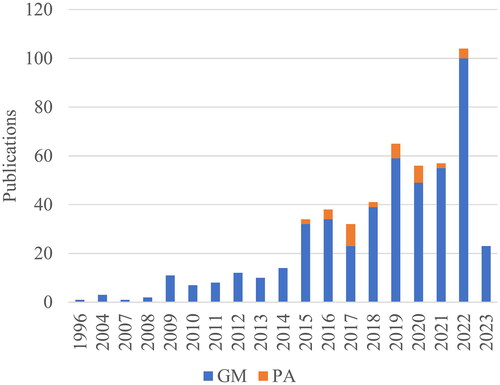

We examine intellectual structure by sector, top 10 articles, leading journals, and then by research theme drawn from a co-citation analysis. By sector, most studies concern general management, with little or no consideration of public value or management. PA studies are firmly in the minority (40 out of 533 studies) (). We found no PA studies before 2015. None of the top 10 cited articles about OA were in the PA field or in PA journals ().

Table 2. Rank of Top 10 Articles, by Total Global Citations Per Year – GCS/t.

shows the journals that have published the most articles on OA, including their citation statistics. Journal topic areas spanned HRM, leadership, and strategy as well as more general management. Public Management Review is the only PA journal in the list, with five articles.

Table 3. Rank of Top 20 Journals, by Number of Publications (POA).

Co-citation analysis

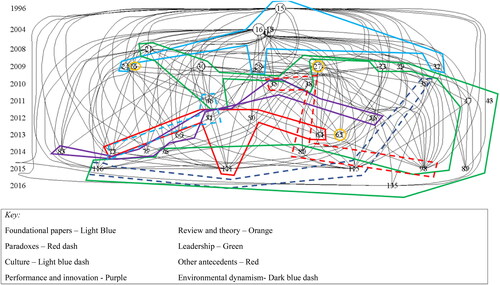

Research streams were identified using co-citation analysis (see ). The 533 articles identified in were imported into HistCite. To get an interpretable co-citation map, balancing comprehensiveness and usability, only articles cited 15 or more times locally in our dataset (LCS ≥ 15) were considered. This identified 35 top papers. The appropriateness of this approach was confirmed by comparing it with other management studies. For example, Apriliyanti and Alon (Citation2017) used an LCS/t of 11 and studied a co-citation graph of 30 articles to understand the intellectual structure of Absorptive Capacity. Marques (Citation2021) studies the co-citation graph of 20 most cited articles in public sector motivation and leadership to understand the knowledge base of the field. Marsilio et al. (Citation2011) used a citation threshold of more than 11 to study the intellectual structure of the public-private partnership field. We also tested the effects of using alternative thresholds (LCS/t = 10 and LCS/t = 5). While this increased the number of papers included in our analysis, our core streams of research remained unchanged.

Figure 2. Top 35 OA papers: Thematic analysis co-citation graph papers with LCS/t > 15 (n = 35 – note none are PA). Foundational papers: Light Blue; Paradoxes: Red dash; Culture: Light blue dash; Performance and innovation: Purple; Review and theory: Orange; Leadership: Green; Other antecedents: Red; Environmental dynamism: Dark blue dash.

Beyond some foundational and theoretical papers that emphasized strategic choices and different types of ambidexterity, the co-citation analysis showed six distinct streams: OA as a response to paradox; three streams concerning antecedents of OA (including leadership and culture); one stream concerning the relationship between OA and performance and/or innovation; and the relationship between environmental dynamism and OA. Appendix 1 summarizes these 35 papers within these streams and provides a key to . The papers are discussed in the next section.

Foundations, theory, and review – Strategic choice and paradox

Tushman and O’Reilly (Citation1996) introduced the idea of OA as being the capability to manage both the evolutionary and the revolutionary change required for success. They recommended OA be achieved primarily structurally through a broad unifying culture, with differentiated business units and a balance of control and autonomy. Gibson and Birkinshaw (Birkinshaw & Gibson, Citation2004; Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004) introduced the concept of contextual ambidexterity, which results from the ambidextrous behavior of individuals who are facilitated or constrained by the organizational context. Simsek et al. (Citation2009) further developed the OA concept by recognizing the role of strategic choices, including structural (i.e. between or within business units), temporal (i.e. cycling between exploration and exploitation or pursuing the two simultaneously), and contextual (i.e. within business units), which they noted is difficult to achieve.

Regarding these strategic choices, temporal OA (or organizational vacillation) has been found to be more effective than structural OA (Boumgarden et al., Citation2012). It is, however, questionable whether temporal OA would be applicable in PA, where tensions and competing goals (e.g. in frontline services) often occur concurrently. Structural OA, which concerns balancing exploration and exploitation between different modes of firm operation (internal organization, alliance, and acquisition) had positive effects on performance. However, contextual OA, the balancing within each mode, can actually damage performance (Stettner & Lavie, Citation2014). Beyond a certain point, an increase in exploration harms performance; exploration by itself seems to have an inverted u-shaped effect on performance (Wei et al., Citation2014).

Key foundational papers from the late 2000s emphasized the complex, multi-level nature of OA and its relevance to paradox. The achievement of OA and its effect on performance may be dependent on the interactions within and between organizations and with the broader environment (Simsek, Citation2009). Contextual OA may be better for responding to paradox when competing demands are embedded within the job or task and require ‘both/and’ rather than ‘either/or’ service delivery; compared to structurally or temporally separating the conflicting elements from each other (Papachroni et al., Citation2015; Smith, Citation2014). OA is demanding on leadership and needs CEO involvement (Tushman et al., Citation2011) to preempt defaults to a favored polarity, such as efficiency (Magnusson et al., Citation2020).

The different approaches for achieving OA, such as structural, temporal, or contextual, likely need to be blended, often varying by level within organization and requiring constant adjustment. OA can also be considered as dialectic in that every state of an organization will eventually be contradicted and negated, so there is a continuous cycle of innovation based on recurring antithesis and synthesis (Bledow et al., Citation2009), with potential unexpected consequences. More generally, context matters, and there are multiple pathways to achieving OA (Bledow et al., Citation2009; Raisch et al., Citation2009; Simsek et al., Citation2009).

Collectively these highly cited papers record development of OA from a mechanism for organizational performance to a set of capabilities to address paradox, complexity, and uncertainty. The most recent of the highly cited foundational articles (Birkinshaw & Gupta, Citation2013) argues that OA should be seen as a multilevel capability that allows tensions between competing objectives to be managed in many different ways. The ability to combine integrating and differentiating techniques is essential but difficult for leaders (Andriopoulous & Lewis, 2010; Smith et al., Citation2010).

Antecedents, leadership, and culture

Most highly cited PA papers concern the antecedents of OA (present in 21 out of 35), with employee characteristics, leader characteristics, organizational structure, cultures, social relationships, and organizational environments commonly studied (Junni et al., Citation2015). Leadership is a large stream, with the value of paradoxical leadership (Smith, Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2010) and CEO leadership (Tushman et al., Citation2011) being prominent. Four studies consider ambidextrous leadership, which through balancing ‘opening’ and ‘closing’ behaviors fosters both exploration and exploitation in individuals and teams and increases ambidextrous innovation (Rosing et al., Citation2011). Opening behaviors support exploration, and closing behaviors support exploitation (Havermans et al., Citation2015; Zacher et al., Citation2016), while the interaction of the two is associated with increased innovation (Zacher & Rosing, Citation2015). Transformational leadership increased the effectiveness of senior team attributes in achieving OA (Jansen et al., Citation2008), which is also effective in PA (Backhaus & Vogel, Citation2022). Strategic leadership, defined as “leadership which focuses on the creation of meaning and purpose for the organization along with the evolution of the organization as a whole” (Lin & McDonough, Citation2011, p. 499), directly impacts on the culture of knowledge sharing, which directly impacts on innovation ambidexterity and mediates the relationship between strategic leadership and innovation ambidexterity. Top management team (TMT) shared leadership enhances OA, mediated by a cooperative conflict management style and decision-making comprehensiveness (Michalache et al., Citation2014). TMT behavioral integration (“the degree to which the group engages in mutual and collective interaction,” Carmeli & Halevi, Citation2009, p. 209) is positively related to OA (Carmeli & Halevi, Citation2009; Halevi et al., Citation2015). TMT leadership, which is characterized by risk tolerance and adaptability, is also associated with increased OA (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012). Middle managers are important in addressing the ambidextrous challenge of a firm’s transition to new technologies by linking existing assets with new technologies (Taylor & Helfat, Citation2009).

Culture is also prominent among the most cited studies. A knowledge-sharing culture (Lin & McDonough, Citation2011), social relationships that combine formalization and connectedness (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012), and a culture that combines organizational diversity with a shared vision support contextual OA (Wang & Rafiq, Citation2014).

OA and performance/innovation

The foundational papers posit OA as something that can enhance organizational performance. The most cited studies that consider performance as an outcome generally support this, with OA sometimes as a mediator between organizational structure or culture and performance (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012; Wang & Rafiq, Citation2014; Wei et al., Citation2014). There are some caveats and nuances. For example, Junni et al.’s (Citation2013) review found that both context and research method affected results with stronger relationships in service organizations and when combined measures of OA and performance were used.

Environmental dynamism

Dynamic environments are those where destabilizing forces, such as technical innovation, globalized competition, and entrepreneurial action, operate with amplified frequency, making strategizing and organizing effectively more challenging (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2010, p. 1264). Ambidexterity provides flexibility for unpredictable environments while maintaining efficiency in stable environments (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2010). Dynamic environments also provide pressure to pursue contextual ambidexterity (Havermans et al., Citation2015) and increase the effect of TMT behavioral integration on OA (Halevi et al., Citation2015).

RQ2: What are the current research frontiers of OA in public administration?

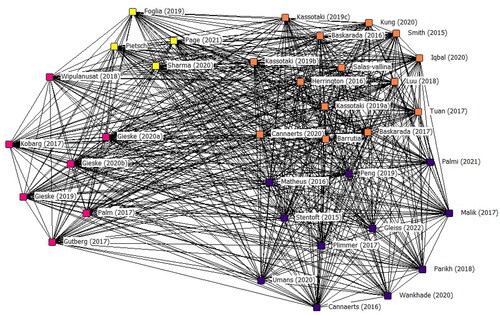

shows that the PA literature on OA is smaller and more recent than the general management literature. Therefore bibliographic coupling (with VosViewer) was performed on the set of 40 public sector articles to answer RQ2 because it is well suited to an early and emerging field. Bibliographic coupling reveals the network of citing documents and helps in identifying the current research themes: it traces more recent publications, independent of the frequency with which the documents have been cited (Andersen, Citation2019; Vogel & Masal, Citation2015).

shows that, of the 40 PA studies,Footnote1 four groups of papers were identified, shown in orange, pink, blue, and yellow and broadly covering, respectively: leadership, culture, structure and processes, and external environment. While these broadly align with the common general management themes around antecedents (see and ), with 36 papers ‘coupling’ (co-citing), no stream considered OA as a response to the PA-specific issues, and there were no foundational theoretical papers considering the PA-specific paradoxes and tensions that OA might address.

Figure 3. Bibliographic coupling map of PA articles (n = 36; 2015–2020). Theme 1 (orange): Leadership; Theme 2 (pink): Culture; Theme 3 (blue): Structure and processes; Theme 4 (yellow): External environment.

Table 4. Antecedents, Moderators, Mediators of OA in PA Studies (n = 18).

Early steps to understanding the relationship between OA and public value have been made. Barrutia and Echeberria (Citation2022) found that both exploitative and exploratory innovation were perceived to increase economic and social value in Spanish municipalities, especially when relatively large economic resources were available. Peng (Citation2019) suggested OA could help produce public value through a combination of small (exploitative) and large (exploratory) steps. For example, concentrating on both evolutionary and disruptive change may improve relationships between public administrations and those they serve by guaranteeing service stability during disruptive change. Furthermore, ambidextrous practices to promote co-production have been accompanied by collaboration with both employees and citizens.

However, a majority of PA papers studied the antecedents of OA in public sector organizations and OA’s effects on performance. While consideration of structure (which includes organizational design and use of specific HR work systems, procedures, and practices) is more prominent in the PA literature than in the most commonly cited general management studies, the majority of PA literature has, to date, followed the agenda of general management rather than identifying and addressing PA-specific concerns.

Our bibliographic coupling is supplemented with a close review of the content of PA papers to provide a comprehensive view of current research frontiers.

Orange group – Leadership

Eleven PA studies have looked specifically at leadership as an antecedent, moderator, or mediator of OA in public sector organizations. In line with the general management literature, OA in public sector organizations is linked to specific leadership styles: transformational (and transactional) (Baškarada et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Kassotaki, Citation2019a, Citation2019b); ambidextrous (Foglia et al., Citation2019; Luu et al., Citation2018); TMT shared leadership (Umans et al., Citation2020); and both forceful and enabling leadership (Cannaerts et al., Citation2020). As with the general management literature, other studies consider specific leadership behaviors, capabilities, and foci as antecedents of OA. These include management concerns for well-being fostering an organizational learning culture and individual-level ambidexterity (Salas-Vallina et al., Citation2021); leadership that has insight into the importance of exploration (Palm & Lilja, Citation2017); essential leadership competencies such as a public focus, creativity, and innovation and the ability to recruit and develop the right people (Mincu, Citation2017); managers in organizations who pay attention to leadership development and encourage their managers’ mobility (Gieske et al., 2019); and having the right type of managerial focus for the organization structure (Smith & Umans, Citation2015).

Pink group – Culture

More ambidextrous organizations have supportive and connected learning capabilities and transformational leadership styles, while less ambidextrous organizations are more rigid, legalistic, transactional, and risk averse in management and culture and performed worse (Gieske, Duijn, et al., 2019; Gieske, van Meerkeek, et al., 2019). Studies found positive effects in cultures that support learning and creativity (Foglia et al., Citation2019; Salas-Vallina et al., Citation2021), provide incentives and support for OA (Foglia et al., Citation2019; Palm & Lilja, Citation2017), and tolerate risk and mistakes (Baskarada et al., 2016; Palm & Lilja, Citation2017). Public service motivation is also found to positively moderate the effect of ambidextrous leadership on OA (Luu et al., Citation2018).

Blue group – Structure and processes

Organizational design is identified as an antecedent in two studies of Flemish cultural centers (Cannaerts et al., Citation2016, Citation2020). Even when formal organizational charts were identical, organizations that have informal structures were found to be more flexible, decentralized, with more ‘bottom-up’ thinking. However, none of the studied organizations had a pure ambidextrous structural design: team-level (contextual) ambidexterity was important. A second study considered designs in terms of the differentiation between teams, centralization, autonomy, and supportive context of the organizational design. It found that an absence of centralization was necessary for OA. Smith and Umans (Citation2015) found that the type of organizational form also mattered. For more economically oriented local government corporations, entrepreneurial and managerial leadership supported OA; whereas for more traditionally managed and socially oriented public authorities, a focus on stakeholders is what mattered. Shared leadership also supports OA, especially when combined with NPM systems of combined reward and performance controls (Umans et al., Citation2020).

The relationship between high-involvement work systems and OA is noted in Malik et al. (Citation2017) and Plimmer et al. (Citation2017), which also identified the role of formal and informal structures and processes. Palm and Lilja (Citation2017) highlight budget for both exploration and exploitation as an antecedent of OA.

Yellow group – External environment

The role of the environment in understanding public organizations and their leadership has been highlighted by Hartley (Citation2018), including the VUCA contexts in which public organizations operate. The relevance of uncertain and changing external environments to OA is a constant throughout foundational general management literature (e.g. Tushman & O’Reilly, Citation1996; Andriopoulos & Lewis, Citation2009), so it is unsurprising that five of the PA studies consider the effects of external environments on OA. For instance, a perceived competitive environment for schools stimulated exploratory and exploitative behaviors by principals (Pietsch et al., Citation2022); and a dynamic environment for hospitals was associated with exploratory behavior (Foglia et al., Citation2019). A turbulent or uncertain external environment was found to be present in most instances of collaborative ambidextrous work between transportation agencies (Page et al., Citation2021). Other factors, such as strong networks of relationships with external stakeholders, to gain external knowledge may be a vital antecedent (Palmi et al., Citation2021).

reports the 17 studies from our sample of 37 that identify antecedents, moderators, and mediators to OA.

PA-specific issues, such as red tape, public value, or PSM, and OA as an antecedent on performance were less commonly studied, but examples can be found across the four groups. Early results are discussed in the next section.

OA as an antecedent of organisational success

In common with the general management literature, PA papers considering the relationship of OA with organizational performance are prominent. Public sector performance, and its measurement, have been huge areas of research over decades (e.g. La Porta et al., Citation1999; Hood, 1995). The controversies and competing explanations in part reflect that compared with measures of profitability, market share, and survival in the private sector, measuring public sector performance is less definite but includes concepts such as social impact, delivery as promised, legality, public acceptability, and sustainability (Douglas et al., Citation2022). The public value literature (e.g. Moore, Citation1995) also highlights different types of value, such as economic, social and cultural, political, and environmental (Bennington, Citation2011). This articulation of the multiple factors involved in judging public sector performance recognizes the importance of handling inherent public sector tensions. Consideration of OA, therefore, aligns naturally with analysis of public sector performance. But there is no single way to best measure or define such performance. The outcomes that are considered in OA studies are diverse, with only the two aforementioned studies considering the more rounded, but hard to measure construct of creating public value (Barrutia & Echeberria, Citation2022; Peng, Citation2019).

As with general management, studies tend to find positive results whatever outcome is selected, albeit with caveats and nuances. Subjective measures of organizational performance (Gieske, Duijn, et al., 2019; Gieske, van Meerkerk, et al., 2019; Gieske et al., Citation2020; Plimmer et al., Citation2017). Objective (though partial) measures of individual performance (Kobarg et al., Citation2017) have been associated with ambidexterity.

Two public-sector studies concentrate on the effects of constructs closely related to OA on individual innovation. Ambidextrous leadership (Rosing et al., Citation2011), the combination of opening and closing behaviors, enhances employees’ innovation (Kung et al., Citation2020). Similarly, an ambidextrous innovation culture that balances both innovation (closely related to exploration) and performance (exploitation) enhances both employee innovation and career satisfaction (Wipulanusat et al., Citation2018). Finally, OA has been associated with two very specific achievements in healthcare: Gleiss and Lewandowski (Citation2022) found that sequential ambidexterity helps remove barriers to implementing digital health services, and Gutberg and Berta (Citation2017) proposed that successfully implementing patient safety cultures depends on the different levels within healthcare organizations adopting different styles: senior leaders exploring new knowledge; middle managers adopting an ambidextrous view and engaging with both senior leaders’ exploration and front-line workers’ exploitation; and front-line workers exploiting existing knowledge.

OA as part of broader PA themes

OA as a mechanism to address specific PA tensions, such as balancing flexibility and creativity with demands for cost savings and efficiency, are addressed in several studies (e.g. Gieske et al., 2019; Palmi et al., Citation2021). Peng’s (Citation2019) consideration of OA strategies is one of the few, however, that specifically addressed public value creation.

In one study, high levels of public service motivation enhanced the effect of ambidextrous leadership in reforming public organizations through means such as simplifying HR rules, reducing hierarchical levels, and decentralizing decision-making (Tuan, Citation2017). Counter-intuitively, the need to circumvent red-tape (non-functional rules) may stimulate OA (Sharma et al., Citation2020).

OA’s potential to address aspects of VUCA are covered in a small number of papers. Ambidextrous leadership in policing allows sufficient innovation to deal with the complexity that leads to crime, while co-existing with policing’s traditional hierarchies (Herrington & Colvin, Citation2015). Ambiguous goals and paradoxes (that municipal corporations face) can be addressed through integrated and differentiated subunit identities, performance and learning, and ensuring performance while maintaining relationships with contractors (Parikh & Bhatnagar, Citation2018). Both structural and contextual ambidexterity strategies have been found to be effective in addressing these tensions, but leaving resolution of these tensions to individuals (expecting individuals to behave ambidextrously) showed mixed results (Parikh & Bhatnagar, Citation2018).

In the very specific example of emergency workers (who are often public employees), ambidexterity has been used to conceptualize how ambulance workers deal with shifts between the mundane but potentially extreme pressures of day-to-day work and the intense extreme pressures associated with, for example, major incidents (Wankhade et al., Citation2020). Finally, in the field of data transparency, relevant to the concept of e-government, exploration was stimulated by creating incentives to use open data to identify and deal with corruption, while exploitation was useful for improving data collection, storage, and use (Matheus et al., Citation2016).

Our RQ1 on the intellectual structure of the OA field and RQ2 about the research frontiers of public sector OA give input to our last RQ3: What is the future OA agenda for PA researchers?

Discussion – RQ3: What is the future OA agenda for PA researchers?

Our study sought to examine OA as a capability to address tensions in PA service delivery. We first searched general management literature and found that strategic choices, leadership, culture, structure, and processes all support OA (as does environmental dynamism) but there is no single way to achieve OA. It requires differentiated strategies at different levels of an organization, spanning top executive teams, middle managers, and front-line staff. These include TMT behavioral integration, high-performance behavioral contexts and structures for both exploration and exploitation (Simsek, Citation2009).

We then examined the smaller, more recent body of PA studies. These corroborate the general management studies as being applicable to PA. PA studies have identified a broad range of antecedents (leadership, structures and processes, the external environment, etc.) to predict often generic and subjective outcomes (Cannaerts et al., Citation2020; Foglia et al., Citation2019; Kobarg et al., Citation2017; Plimmer et al., Citation2017). However, the specific nature of public organizations are not often explicitly considered. For example, organizational culture is widely considered in both the PA and management literatures (e.g. Foglia et al., Citation2019; Gieske, Duijn, et al., 2020; Page et al., Citation2021; Palmi et al., Citation2021), yet the political and hence hierarchical nature of public sector cultures (which inhibit information flow and trust) may limit the openness, learning, and tolerance of risk cultures that are identified as antecedents of OA in management studies (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012; Lin & McDonough, Citation2011). The management literature can inform the PA literature, but PA cannot simply replicate the general management agenda.

Existing studies demonstrate well that OA is applicable to PA, but there is a need for more studies on the specific constructs, tensions, dilemmas, and paradoxes of PA. For instance, in complex policy networks diversity and an explicit motivation to balance exploration and exploitation helps foster ambidexterity and inhibit PA biases to exploitation (Heras et al., Citation2020). Managing a variety of tensions – such as between competing stakeholders could be enabled by OA through the ability to efficiently tailor and deploy different responses to different groups of stakeholders (Van Der Wal, Citation2017).

The frontier lies in integrating PA-specific issues with OA. This frontier spans institutional arrangements, managing PA outcomes, and PA processes within organizations, and the broader dynamic environments within which public organizations work.

Institutional arrangements

One frontier involves further investigating the role of NPM or other institutional arrangements in shaping OA: how NPM, post-NPM, or more traditional administrative arrangements are conducive to OA, and how this might affect the choice of strategies to achieve OA. The few studies that have examined this have found that NPM-influenced arrangements, such as contingent rewards and performance controls, can be beneficial for OA and performance (Pandey et al., Citation2022; Plimmer et al., Citation2017). This is consistent with Gibson and Birkinshaw’s (Citation2004) foundational general management study, which found that clear goals, expectations, and incentives (discipline and stretch) support OA. These findings support a non-ideological but nuanced approach to institutional settings that likely needs to be combined with soft factors (such as shared leadership), with carefully crafted consideration of how settings might operate in practice (Umans et al., Citation2020).

PA outcomes

A second frontier concerns OA’s potential to improve PA outcomes by resolving the tensions and competing goals inherent in the pursuit of public value (Bennington, Citation2011; Moore, Citation1995), and lessening the default to efficiency and risk of perverse outcomes from the pursuit of KPIs (Bevan & Hamblin, Citation2009; Rigby et al., Citation2014). More rounded interpretations of public sector performance, or public value creation, have emerged recently, which often combine varying mixes of outcomes, trust and legitimacy, service quality, and value for money (Faulkner & Kaufman, Citation2018). Richer and more contextual views of value creation are needed as study outcomes. Richer and more PA oriented approaches to achieving it are also needed.

PA processes

Further research frontiers concern the integration of both within and between organizational processes. Many PA studies concentrate on the public organization as a provider and so concentrate on within organizational factors. A more recent PA ecosystem approach that has emerged emphasizes partnership between and with different organizations (such as NGOs) and with consumers themselves as co-creators of value (Osborne et al., Citation2022). This complex approach highlights the need for exploratory (variance increasing) behaviors that can also be deployed and exploited (variance decreasing). A research focus on arrangements within organizations neglects arrangements between PA organizations and other stakeholders, and a focus on ‘co’ concepts risks neglecting the challenges that accountable hierarchies face. For collaboration, and other ‘co’ concepts, further research could examine how to deploy (or exploit) the benefits of these concepts more broadly. The knowledge gap regarding how to integrate external with internal processes could potentially be addressed with further PA-tailored concepts, such as ‘collaborative ambidexterity’ (Page et al., Citation2021).

The ‘co’ concepts embody several tensions, such as between individual and societal benefits and between stakeholders as consumers or as citizens (Laing, Citation2003; Palumbo & Manesh, Citation2021). The balancing of these tensions can include serious risks, including service ‘capture’ by powerful but unrepresentative groups (Palumbo & Manesh, Citation2021). Studies are needed on how ambidexterity can foster co-behaviors that create public value, including legitimacy and value for money, as well as service quality.

Future studies could examine processes to align multiple dimensions of value creation. Examples include maintaining trust by continuing with what already works well (exploitation); while innovating for emerging issues (exploration); or developing co-production with specific groups while maintaining legitimacy with the wider community through efficient and consistent service (Peng, Citation2019). The importance of the external environment, inter-organizational relations, and intra-organization behavior is emphasized in Simsek’s multi-level model of OA (2009), which has not yet been applied widely to PA. The importance of considering OA at different levels of healthcare organizations has been recognized though (Gutberg & Berta, Citation2017). The importance of top management team integration has received limited attention in the PA literature, despite several general management studies (Carmeli & Halevi, Citation2009).

The role of middle managers in fostering OA is currently understudied in public settings. Leadership styles, such as ambidextrous leadership (Rosing et al., Citation2011) and paradoxical leadership (Smith & Tushman, Citation2005) are relevant. In the PA literature, however, studies are few (Foglia et al., Citation2019).

Contextual ambidexterity for frontline workers remains understudied. How to promote the right mix of rule bending and rule adherence, versus corrupt rule bending or blind compliance, warrants further study. Front-line workers bend rules to deliver their services (Lipsky, Citation1980), and red tape can have the unexpected side effect of encouraging OA by encouraging workarounds (Sharma et al., Citation2020). A contextual ambidexterity lens provides guidance into how to balance between flexible and rigid rule-following. PSM may reciprocally help motivate ambidextrous responses. Only one study has examined the relationship between OA and PSM (Tuan, Citation2017), and it did not establish a causative link in either direction.

Environmental dynamism

Environmental dynamism was found to have a weak role in PA, based on the single PA study on this aspect (Foglia et al., Citation2019). In the management literature, however, the results are much clearer: environmental dynamism stimulates ambidextrous behavior. The challenge is to consider the difference between the dynamic environments experienced by private sector organizations with the volatility or turbulence faced by public sector institutions. At first sight, the public sector may appear to operate in a less dynamic environment as public agencies are not subject to market pressures or risk of financial failure. However, the volatility and complexity of environments in which public agencies operate, is increasingly recognized. Different conceptions of this include VUCA (Hartley, Citation2018; Van der Wal, Citation2017) turbulence (Ansell et al., Citation2023) and hyper-innovation (e.g. Moran, Citation2003; Pollitt, Citation2007), where the political process itself, through changes of administration and policy, creates volatility and uncertainty through radically changing structures, agendas, and priorities. These various forms of instability may make co-creation more difficult (Scognamiglio et al., Citation2023). Similarly, instability generated by repeated structural reform has been shown to have several detrimental side-effects (Wynen et al., Citation2017) including a tendency to reserve decision-making to a small set of central leaders; reducing the freedom to innovate at a local level; retrenching to the most well-ingrained behaviors; reducing flows of information; and reducing collaboration (Staw et al., Citation1981; Wynen et al., Citation2017). These behaviors all run counter to the flexible behaviors required for OA. In contrast, structural stability helps deliver the flexibility needed to allow adaption. (Trondal, Citation2023). Coping with political turbulence may require a quite different capability or type of ambidexterity than that required to better respond to changing citizen needs within resource constraints (Cao et al., Citation2023). A stable platform of technologies, values, and capabilities may provide the foundation for needed ambidexterity to deal with dynamism, but no research currently addresses this nuanced but critical question.

Conclusions

OA has great potential as both a lens and a body of practice to assess PA dilemmas and tensions. Although there are many similarities to, and useful lessons from, the private sector that are applicable to PA, practices are not immediately transferable and need consideration of institutional context, PA structure and process, and the PA environment. There are also exciting research frontiers examining OA as a means to address specific PA issues such as complexity, tensions and tradeoffs. PA studies of OA are relatively recent. General management studies provide a rich body of knowledge to be adapted and verified to PA.

This article identified four research frontiers: institutional arrangements, managing PA outcomes, PA processes, and environmental dynamism. Further research is also needed on the tensions in creating public value and on ambidextrous ways to achieve it, with more focus on salient PA constructs and issues.

For practitioners, we point to the relevance of OA in addressing many of the issues broadly surrounding PA value creation and dilemmas. Organizations wishing to be ambidextrous need to operate on multiple levels and be ambidextrous in the implementation of ambidexterity itself. For example, the change process needs to be exploratory (such as seeking staff views) and exploitative (clearly and transparently deploying resulting suggestions). A useful place to start this approach may be within job and task design themselves, where employees can exercise exploratory knowledge gathering and allowable risk taking to find solutions. They can then seek to implement proven successful solutions efficiently through standardization of process.

Many organizations will need consciously to overcome bias and encourage one or other of exploratory or exploiting behaviors. Under NPM, public agencies have had a bias toward exploitation rather than exploration. In contrast, the emerging ‘co’- concepts are naturally exploratory. To fully realize the benefits of the concepts, clear but supportive exploitive behaviors such as systems and processes to deploy at scale are needed.

Structurally, consideration of the balance between exploration and exploitation in any given work unit is needed. No unit is likely to be entirely one or the other in their operating, but they all need to coherently integrate and balance the two. Development of ambidextrous leadership, where leaders are confident to move between opening and closing behaviors in response to circumstances is likely to help.

Top management teams should focus on behavioral integration (i.e. mutual and collective interaction among TMT members). However over-centralized organizational cultures and structures can inhibit the development of OA. Finally, the right formal (e.g. rules-based processes) and informal (e.g. organizational values, beliefs and traditions) systems will be positively associated with OA.

A study limitation is that it may have missed articles that are excluded from WOS and Scopus databases, and our checks elsewhere. Another weakness is the risk of the Matthew effect, where highly cited articles receive more citations regardless of their underlying merit (Merton, Citation1968), while other papers that are more recent and therefore have less citations are neglected. Nevertheless, the articles that have been studied in this paper provide a rich resource for the further development of OA in PA as a promising research domain.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard Hamblin

Richard Hamblin ([email protected]) is a PhD Candidate at the School of Management, Te Herenga Waka - Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand). He is also Director of Health Quality Intelligence at Te Tāhū Hauora - Health Quality and Safety Commission, and responsible for all aspects of the Commission’s measurement of the quality of New Zealand’s health care. He has published widely on the quality of healthcare systems and how to assess this. His PhD research is on Organizational Ambidexterity and Public Sector Performance.

Geoff Plimmer

Geoff Plimmer ([email protected]) is Associate Professor at the School of Management at Victoria University of Wellington. His research expertise primarily concerns the public sector. He is focussed on leadership, and what supports or impedes the development of organizational and individual capabilities.

Kamal Badar

Kamal Badar ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor, Nottingham University Business School, University of Nottingham, Malaysia. He previously worked as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow within the Brian Picot Chair in Ethical Leadership – Aritahi within Te Herenga Waka - Victoria University of Wellington. His research focuses on various leadership styles and employee outcomes, counterproductive work behaviors, and the work ethics of young generations.

Karin Lasthuizen

Karin Lasthuizen ([email protected]) is a Professor in Management and she holds the Brian Picot Chair in Ethical Leadership - Aritahi at Te Herenga Waka - Victoria University of Wellington. Her research is in the field of ethical leadership and ethics management within public and private sector organizations and in politics, and she specializes in methodology for research into integrity violations and organizational misbehavior, such as corruption, fraud, conflicts of interest, abuse of authority and interpersonal deviance.

Notes

1 The largest connected component was 36 articles.

References

- Adler, P., Goldoftas, B., & Levine, D. I. (1999). Flexibility versus efficiency? A case study of model changeovers in the Toyota production system. Organization Science, 10(1), 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.1.43

- Andersen, N. (2019). Mapping the expatriate literature: A bibliometric review of the field from 1998 to 2017 and identification of current research fronts. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(22), 4687–4724. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1661267

- Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20(4), 696–717. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0406

- Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2010). Managing innovation paradoxes: Ambidexterity lessons from leading product design companies. Long Range Planning, 43(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.08.003

- Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? The need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Public Management Review, 23(7), 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272

- Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2023). Public administration and politics meet turbulence: The search for robust governance responses. Public Administration, 101(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12874

- Antonsen, M., & Jørgensen, T. B. (1997). The ‘publicness’ of public organizations. Public Administration, 75(2), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00064

- Apriliyanti, I., & Alon, J. (2017). Bibliometric analysis of absorptive capacity. International Business Review, 26(5), 896–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.02.007

- Backhaus, L., Reuber, A., Vogel, D., & Vogel, R. (2022). Giving sense about paradoxes: Paradoxical leadership in the public sector. Public Management Review, 24(9), 1478–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1906935

- Backhaus, L., & Vogel, R. (2022). Leadership in the public sector: A meta‐analysis of styles, outcomes, contexts, and methods. Public Administration Review, 82(6), 986–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13516

- Barrutia, J. M., & Echebarria, C. (2022). Public managers’ perception of exploitative and explorative innovation: An empirical study in the context of Spanish municipalities. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 88(1), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852319894688

- Baškarada, S., Watson, J., & Cromarty, J. (2016). Leadership and organizational ambidexterity. Journal of Management Development, 35(6), 778–788. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2016-0004

- Baškarada, S., Watson, J., & Cromarty, J. (2017). Balancing transactional and transformational leadership. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(3), 506–515. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-02-2016-0978

- Bennington, J. (2011). From private choice to public value? Chapter 2. In J. Bennington & M. H. Moore (ed.), Public value theory and practice (pp. 31–52). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Bevan, G., & Hamblin, R. (2009). Hitting and missing targets by ambulance services for emergency calls: Effects of different systems of performance measurement within the UK. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A, (Statistics in Society),), 172(1), 161–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00557.x

- Birkinshaw, J., & Gibson, C. (2004). Building ambidexterity into an organization. Mit Sloan Management Review, 45(4), 47.

- Birkinshaw, J., & Gupta, K. (2013). Clarifying the distinctive contribution of ambidexterity to the field of organization studies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0167

- Bledow, R., Frese, M., Anderson, N., Erez, M., & Farr, J. (2009). A dialectic perspective on innovation: Conflicting demands, multiple pathways, and ambidexterity. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2(3), 305–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2009.01154.x

- Boumgarden, P., Nickerson, J., & Zenger, T. R. (2012). Sailing into the wind: Exploring the relationships among ambidexterity, vacillation, and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(6), 587–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1972

- Bozeman, B. (1987). All organizations are public: Bridging public and private organizational theories. Jossey-Bass.

- Cannaerts, N., Segers, J., & Henderickx, E. (2016). Ambidextrous design and public organizations: A comparative case study. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 29(7), 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-12-2015-0210

- Cannaerts, N., Segers, J., & Warsen, R. (2020). Ambidexterity and public organizations: A configurational perspective. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(3), 688–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1676272

- Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E., & Zhang, H. P. (2009). Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organization Science, 20(4), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0426

- Cao, L., West, B., Ramesh, B., Mohan, K., & Sarkar, S. (2023). A platform-based approach to ambidexterity for innovation: An empirical investigation in the public sector. International Journal of Information Management, 68, 102570. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102570

- Carmeli, A., & Halevi, M. Y. (2009). How top management team behavioral integration and behavioral complexity enable organizational ambidexterity: The moderating role of contextual ambidexterity. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.01.011

- Chandrasekaran, A., Linderman, K., & Schroeder, R. (2012). Antecedents to ambidexterity competency in high technology organizations. Journal of Operations Management, 30(1–2), 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2011.10.002

- Chang, Y. Y., & Hughes, M. (2012). Drivers of innovation ambidexterity in small- to medium-sized firms. European Management Journal, 30(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2011.08.003

- Donadelli, F., & Lodge, M. (2019). Machinery of government reforms in New Zealand: Continuous improvement or hyper-innovation? Policy Quarterly, 15(4), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v15i4.6136

- Donate, M. J., & de Pablo, J. D. S. (2015). The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.022

- Douglas, S., ‘T Hart, P., & Van Erp, J. (2022). Identifying and interpreting government successes: An assessment tool for classroom use. Teaching Public Administration, 40(2), 276–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/01447394221079687

- Dudau, A., Glennon, R., & Verschuere, B. (2019). Following the yellow brick road? (Dis)enchantment with co-design, co-production and value co-creation in public services. Public Management Review, 21(11), 1577–1594. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1653604

- Dudau, A., Kominis, G., & Szocs, M. (2018). Innovation failure in the eye of the beholder: Towards a theory of innovation shaped by competing agendas within higher education. Public Management Review, 20(2), 254–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1302246

- Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., Bastow, S., & Tinkler, J. (2005). New public management is dead—long live digital-era governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(3), 467–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui057

- Eisenhardt, K. M., Furr, N. R., & Bingham, C. B. (2010). Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science, 21(6), 1263–1273. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0564

- Faulkner, N., & Kaufman, S. (2018). Avoiding theoretical stagnation: A systematic review and framework for measuring public value. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12251

- Foglia, E., Ferrario, L., Lettieri, E., Porazzi, E., & Gastaldi, L. (2019). What drives hospital wards’ ambidexterity: Insights on the determinants of exploration and exploitation. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 123(12), 1298–1307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.10.004

- Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159573

- Gieske, H., Duijn, M., & van Buuren, A. (2019b). Ambidextrous practices in public service organizations: Innovation and optimization tensions in Dutch water authorities. Public Management Review, 22(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1588354

- Gieske, H., George, B., van Meerkerk, I., & van Buuren, A. (2020). Innovating and optimizing in public organizations: Does more become less? Public Management Review, 22(4), 475–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1588356

- Gieske, H., van Meerkerk, I., & van Buuren, A. (2019a). The impact of innovation and optimization on public sector performance: Testing the contribution of connective, ambidextrous, and learning capabilities. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(2), 432–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1470014

- Gleiss, A., & Lewandowski, S. (2022). Removing barriers for digital health through organizing ambidexterity in hospitals. Journal of Public Health, 30(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01532-y

- Gusenbauer, M. (2019). Google Scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. " Scientometrics, 118(1), 177–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2958-5

- Gutberg, J., & Berta, W. (2017). Understanding middle managers’ influence in implementing patient safety culture. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 582. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2533-4

- Halevi, M. Y., Carmeli, A., & Brueller, N. N. (2015). Ambidexterity in SBUs: TMT behavioral integration and environmental dynamism. Human Resource Management, 54(S1), S223–S238. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21665

- Hartley, J. (2018). Ten propositions about public leadership. International Journal of Public Leadership, 14(4), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-09-2018-0048

- Havermans, L. A., Den Hartog, D. N., Keegan, A., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2015). Exploring the role of leadership in enabling contextual ambidexterity. Human Resource Management, 54(S1), S179–S200. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21764

- Heras, A., Henar, H. M., Estensoro, M. & Larrea, (2020). Organizational ambidexterity in policy networks. "Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 30(2), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-02-2018-0013

- Herrington, V., & Colvin, A. (2015). Police leadership for complex times. Policing, 10(1), pav047. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pav047

- Jansen, J. J., P., George, G., Van den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2008). Senior team attributes and organizational ambidexterity: The moderating role of transformational leadership. Journal of Management Studies, 45(5), 982–1007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00775.x

- Junni, P., Sarala, R. M., Taras, V., & Tarba, S. Y. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0015

- Junni, P., Sarala, R. M., Tarba, S. Y., Liu, Y. P., & Cooper, C. L. (2015). Guest editors’ introduction: The role of human resources and organizational factors in ambidexterity. Human Resource Management, 54(S1), S1–S28. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21772

- Kassotaki, O. (2019a). Ambidextrous leadership in high technology organizations. Organizational Dynamics, 48(2), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2018.10.001

- Kassotaki, O. (2019b). Explaining ambidextrous leadership in the aerospace and defense organizations. European Management Journal, 37(5), 552–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.04.001

- Kinder, T., & Stenvall, J. (2023). A critique of public service logic. Public Management Review, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2182904

- Kobarg, S., Wollersheim, J., Welpe, I. M., & Spörrle, M. (2017). Individual ambidexterity and performance in the public sector: A multilevel analysis. International Public Management Journal, 20(2), 226–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2015.1129379

- Kung, C. W., Uen, J. F., & Lin, S. C. (2020). Ambidextrous leadership and employee innovation in public museums. Chinese Management Studies, 14(4), 995–1014. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-05-2018-0523

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 15(1), 222–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/15.1.222

- Laing, A. (2003). Marketing the public sector: Towards a typology of public services. Marketing Theory, 3(4), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593103042005

- Lin, H.-E., & McDonough, E. F. (2011). Investigating the role of leadership and organizational culture in fostering innovation ambidexterity. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 58(3), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2010.2092781

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Luu, T. T., Rowley, C., & Dinh, K. C. (2018). Enhancing the effect of frontline public employees’ individual ambidexterity on customer value co-creation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(4), 506–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-04-2017-0091

- Magnusson, J., Koutsikouri, D., & Päivärinta, T. (2020). Efficiency creep and shadow innovation: Enacting ambidextrous IT governance in the public sector. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(4), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1740617

- Malik, A., Boyle, B., & Mitchell, R. (2017). Contextual ambidexterity and innovation in healthcare in India: The role of HRM. Personnel Review, 46(7), 1358–1380. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-06-2017-0194

- March, J. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- Marques, T. M. (2021). Research on public service motivation and leadership: A bibliometric study. International Journal of Public Administration, 44(7), 591–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1741615

- Marsilio, M., Cappellaro, G., & Cuccurullo, C. (2011). The intellectual structure of research into PPPs: A bibliometric analysis. Public Management Review, 13(6), 763–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.539112

- Matheus, R., Janssen, M., Bertot, J., Estevez, E., & Mellouli, S. (2016). Exploitation and Exploration Strategies to Create Data Transparency in the Public Sector [Paper presentation].9th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Icegov 2016, 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/2910019.2910091

- Meijer, A., ‘t Hart, P., & Worthy, B. (2018). Assessing government transparency: An interpretive framework. Administration & Society, 50(4), 501–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399715598341

- Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science: The reward and communication systems of science are considered. Science, 159(3810), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.159.3810.56

- Michalache, O. R., Jansen, J. J. P., Van den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2014). Top management team shared leadership and organizational ambidexterity: A moderated mediation framework. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 8(2), 128–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1168

- Mincu, C. (2017). Sharpening leadership edge in the public sector and private business for adaptive-to-change organizations. Calitatea, 18(S3), 9–15.

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard University Press.

- Moran, M. (2003). The British Regulatory State: High modernism and hyper-innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Osborne, S. P., Powell, M., Cui, T., & Strokosch, K. (2022). Value creation in the public service ecosystem: An integrative framework. Public Administration Review, 82(4), 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13474

- Page, S. B., Bryson, J. M., Stone, M. M., Crosby, B. C., & Seo, D. (2021). Ambidexterity in cross-sector collaborations involving public organizations. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(6), 1161–1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2021.1937243

- Palm, K., & Lilja, J. (2017). Key enabling factors for organizational ambidexterity in the public sector. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 9(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-04-2016-0038

- Palmi, P., Corallo, A., Prete, M. I., & Harris, P. (2021). Balancing exploration and exploitation in public management: Proposal for an organizational model. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(3) 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2245

- Palumbo, R., & Manesh, M. F. (2021). Travelling along the public service co-production road: A bibliometric analysis and interpretive review. Public Management Review, 25(7), 1348–1384. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.2015222

- Pandey, S. K., Cheng, Y., & Hall, J. L. (2022). Epistemic decolonization of public policy pedagogy and scholarship. Public Administration Review, 82(6), 977–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13560

- Papachroni, A., Heracleous, L., & Paroutis, S. (2015). Organizational ambidexterity through the lens of paradox theory: Building a novel research agenda. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 51(1), 71–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886314553101

- Parikh, M., & Bhatnagar, D. (2018). A system of contradictory goals and realization of ambidexterity: A case study of a municipal Corporation. International Journal of Public Administration, 41(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.1076465

- Peng, H. X. (2019). Organizational ambidexterity in public non-profit organizations: Interest and limits. Management Decision, 57(1), 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-01-2017-0086

- Pietsch, M., Tulowitzki, P., & Cramer, C. (2022). Principals between exploitation and exploration: Results of a nationwide study on ambidexterity of school leaders. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(4), 574–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220945705

- Plimmer, G., Bryson, J., & Teo, S. T. T. (2017). Opening the black box: The mediating roles of organisational systems and ambidexterity in the HRM-performance link in public sector organisations. Personnel Review, 46(7), 1434–1451. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2016-0275

- Pollitt, C. (2007). New Labour’s re-disorganization: Hyper-modernism and the costs of reform - A cautionary tale. Public Management Review, 9(4), 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030701726663

- Qiu, H., & Chreim, S. (2021). A tension lens for understanding public innovation diffusion processes. Public Management Review, 24(12), 1873–1893. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1942532

- Raisch, S., Birkinshaw, J., Probst, G., & Tushman, M. L. (2009). Organizational ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for sustained performance. Organization Science, 20(4), 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0428

- Rigby, J., Dewick, P., Courtney, R., & Gee, S. (2014). Limits to the implementation of benchmarking through KPIs in UK construction policy: Insights from game theory. Public Management Review, 16(6), 782–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.757351

- Ritz, A., Neumann, O., & Vandenabeele, W. (2016). Motivation in the public sector. Chapter 30. In T. R. Klassen, D. Cepiku, & T. J. Lah, (eds.). The Routledge handbook of global public policy and administration. (pp. 346–359). Taylor and Francis.

- Rosing, K., Frese, M., & Bausch, A. (2011). Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: Ambidextrous leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(5), 956–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.07.014

- Salas-Vallina, A., Alegre, J., & Ferrer-Franco, A. (2021). Well-being-oriented management, WOM, organizational learning and ambidexterity in public healthcare: A two wave-study. International Public Management Journal, 25(6), 815–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2021.1942341

- Scognamiglio, F., Sancino, A., Caló, F., Jacklin‐Jarvis, C., & Rees, J. (2023). The public sector and co‐creation in turbulent times: A systematic literature review on robust governance in the COVID‐19 emergency. Public Administration, 101(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12875

- Sharma, A., Gautam, H., & Chaudhary, R. (2020). Red tape and ambidexterity in government units. International Journal of Public Administration, 43(8), 736–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1652314

- Simsek, Z. (2009). Organizational ambidexterity: Towards a multilevel understanding. Journal of Management Studies, 46(4), 597–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00828.x

- Simsek, Z., Heavey, C., Veiga, J. F., & Souder, D. (2009). A typology for aligning organizational ambidexterity’s conceptualizations, antecedents, and outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 46(5), 864–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00841.x