ABSTRACT

Social work educators have long struggled with the challenge of finding appropriate strategies for fostering cultural awareness among their students. The purpose of this study is to illustrate how a computer-based simulation, SimChild, can be used in teaching about child protection to enhance cultural awareness among students and expand their insight into how personal biases can affect professional practice. In SimChild, individual students can assume the role of social worker and then collectively discuss the patterns emerging after their individual assessments have been aggregated. This study, based primarily on focus group data, reflects testing conducted at three Swedish universities.

Introduction

Child protection is one of the most crucial areas of professional social work, and decisions in such cases can have far-reaching consequences for children and families. However, predicting which children will be safe and which will be at risk is, as Munro (Citation1996: 793) put it, “an uncertain business.” Like other professional decision-making, child assessments are made under time pressure and based on often uncertain data. As social cognition research has demonstrated (e.g., Fiske & Neuberg, Citation1990; Fiske & Taylor, Citation2013; Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, Citation1982), professional decision-making under such conditions tends to be influenced by unconscious biases. For example, professionals tend to ascribe disproportionate weight to information that is particularly noteworthy or emotionally significant, and cognitive lock-in effects appear to be frequent. If, for example, a social worker initially assesses a given family situation as safe for the child, continued investigation will be less sensitive to warning signals (Munro, Citation1996). Another type of unconscious bias appears when the social worker draws conclusions about an individual case based on general stereotypical preconceptions regarding the social category to which clients are assigned, such as socioeconomic status, gender, and ethnicity (Fiske & Neuberg, Citation1990). The importance of ethnicity in this context has garnered particular attention in recent years.

Research into the effects of ethnic affiliation and race on child assessments by social workers remains relatively limited, although some studies (e.g., Buckley, Citation2000; Križ & Skivenes, Citation2010; Sawrikar, Citation2017; Stokes & Schmidt, Citation2011) do indicate that unconscious biases may play more than a minor role. One important finding is that stereotypical thinking in such contexts can take different forms; this concerns what are customarily referred to as a cultural deficit tendency and a cultural relativist tendency (Chand, Citation2008). In the cultural deficit tendency, social workers interpret the difficulties facing a child as manifestations of a minority culture that is problematic in and of itself. The solution involves either “correcting” the culture in some manner or even “rescuing” the child from the culture via a caretaking process. The cultural relativist tendency is based, at least in its purer form, on the assumption that actions are never absolutely right or wrong. The cultural affiliations of the actors determine what is right and wrong and, consequently, representatives of one culture do not have the right to criticize representatives of another. The cultural deficit and cultural relativist tendencies may appear to be opposites but are actually connected by a static view in which clients are made into passive objects of minority cultures perceived as both homogenous and all-powerful. However, ethnic cultures in modern Europe and North America are not iron cages; rather, ethnic cultures are dynamic, changeable, and characterized by pluralism and internal tensions (e.g., Hannerz, Citation1999).

The stereotypical preconceptions regarding ethnic cultures that can be described collectively as the cultural deficit and cultural relativist tendencies can have disastrous effects on children and families. In the first instance, there is a risk of unwarranted social work interventions that are deeply offensive to the affected families and, moreover, do more harm than good. In the second instance, there is a risk that social workers will fail to intervene because the child belongs to a minority family, i.e., problems that normally lead to interventions are seen as “unavoidable” and thus “acceptable” in minority families.

Against this background, it would seem essential for social work schools to make future social workers aware of how ethnic biases can affect their professional assessments and decisions, and help them to be aware of and reflect on their own biases. In North America and Europe, such instruction has often been given under the rubric of “cultural competence.” Even though cultural competence has assumed a central position in the discourse surrounding social work education, there is no clear definition of the term (Johnson & Munch, Citation2009). However, the elementary meaning of cultural competence can, as Azzopardi and McNeil (Citation2016: 283) suggested, be summarized as “an ongoing process whereby one gains awareness of, and appreciation for, cultural diversity and an ability to work sensitively, respectfully, and proficiently with those from diverse backgrounds.” The extensive debate among social work educators regarding cultural competence has not, however, been concerned solely with questions of definition; the approach per se has also increasingly been problematized and called into question. Cultural competence has conventionally often been described as a combination of three components: cultural knowledge (i.e., knowledge of specific cultural groups), cultural skills (i.e., skills pertaining to interventions in such groups), and cultural awareness (i.e., social workers’ awareness of their own beliefs and biases) (e.g., Sue et al., Citation1982; Sue & Sue, Citation2003). The criticism leveled at the concept of cultural competence has primarily concerned the cultural knowledge and cultural skills components. According to the critics, the idea that future social workers could be equipped with specific cultural knowledge and skills is based on the unfounded preconception that cultures are homogeneous and static phenomena (Hollingsworth, Citation2013), and on the preconception that clients can be understood in simple terms as the bearers of such cultures (Tsang, Bogo, & George, Citation2003). The critics further assert that such “culturalization” of clients leads social workers to risk underemphasizing the unique situation of the individual and overlooking the power relationships affecting him or her (Garran & Werkmeister Rozas, Citation2013). As Nadan (Citation2016) pointed out against the background of these and other criticisms, the importance of cultural awareness, rather than of cultural knowledge and skills, has come to be emphasized in social work education (see also Garran & Rozas, Citation2013; Heydt & Sherman, Citation2005; Yan & Wong, Citation2005).

Even as the importance of cultural awareness among social work students has been increasingly emphasized, the difficulties associated with instilling such awareness have been pointed out as well. One such difficulty concerns demonstrating that cultural awareness is significant in all the fields in which social workers are active (e.g., Blunt, Citation2007). Student ability to comprehend how cultural awareness is inherent in all professional practice will not be enhanced if reference is made to such competence in just some of their courses. Another difficulty concerns how cultural awareness is taught. Social work students are often unaware of how their biases can affect their perceptions, attitudes, and practice (Hepworth, Rooney, & Larsen, Citation2002), and instilling cultural awareness is dependent on their being given opportunities to identify unreflective thinking and develop more complex knowledge structures. The problem is that such processes cannot be elicited through conventional classroom instruction, but rather require active learning.

The insight that lectures and other conventional classroom-based activities do not suffice to instill cultural awareness is longstanding (e.g., Eldridge, Citation1982), and the literature also proposes various alternative pedagogical means, all based on active student learning, such as intergroup dialogues (Nagda et al., Citation1999), structured controversy (Steiner, Brzuzy, Gerdes, & Hurdle, Citation2003), cultural genograms (Warde, Citation2012), storytelling (Carter-Black, Citation2007), and the use of literary sources (Garcia & Bregoli, Citation2000). Remarkably, as far as we can see, no attempts involving computer-based simulations have been reported in this context (but see Reinsmith-Jones, Kibbe, Crayton, & Campbell, Citation2015). The present study is intended to illustrate how a computer-based simulation, SimChild, can enable students to enhance their cultural competence in a concrete knowledge context and become aware of how their unreflective thinking can affect their assessments and decisions in child protection cases.

Computer-based simulations have become increasingly common in higher education in both medicine and the social sciences in recent years (Gredler, Citation2004). Attempts to use computer-based simulations in social work education have so far usually involved virtual worlds in which students are given opportunities to interact with standardized clients, for example, to provide training in interviewing skills (Tandy, Vernon, & Lynch, Citation2017). In contrast to such simulations, SimChild is intended to simulate the assessment and decision-making processes that typify social work. SimChild is similar to the dominant model of simulations in advanced professional teaching programs, in which students are assigned, based on a reasonable model of a given professional context, a defined role and tasked with arriving at decisions by analyzing a complex context (Gredler, Citation2004; Salas, Wildman, & Piccolo, Citation2009). In SimChild—a microworld of professional assessments and decision making (Wastell et al., Citation2011)—the student can assume the role of social worker in a child protection case. The students are tasked, in a realistic, safe environment and without potential harm to clients, with analyzing different types of written materials and making and explaining professional decisions based on the vague and contradictory indicators that quite often characterize such cases. All participating students are given access to the same case, but the background circumstances of the case, such as ethnicity, gender, or socioeconomic status, are varied at random, unknown to the students. The individual problem-solving phase is followed by seminars in which the students discuss the aggregated results of their individual assessments so that they can discern patterns and reflect on the effects that the manipulation of the background circumstances had.

Method

By definition, simulations in higher education are simplifications of reality, but they must at the same time realistically represent professional decision-making, i.e., professional decision-making that is typically based on inadequate and often contradictory information. In addition, SimChild strives for a degree of formal structural mimicry: the forms of the assessments and the steps in the assessment process are reminiscent of those often found in child-care assessments in Sweden and other European countries (Borell & Egonsdotter, Citation2012; Léveillé & Chamberland, Citation2010).

In SimChild, individual exercises are combined with subsequent group seminars (see ). The individual computer-based exercises consist of two phases. During the first phase, the students involved in this study were presented with a case in which their assignment consisted of assessing whether a child needed emergency protection. The case was described in the same way for all the students, but with one difference that was unknown to them: the child and its family had Somali names for half of the students, and typical ethnic Swedish names for the other half (Somalis came to Sweden after the collapse of the Somali state in the early 1990s. Somalis are one of the most segregated groups in the country). The case, described in greater detail below, was presented using information about a telephone call from a concerned neighbor as well as records transcripts and journal notes of meetings and telephone conversations. During the second phase, the students were tasked with deciding, based on additional information about the case, whether a formal investigation of the child should be launched. In support of the decision-making process, the students were asked to answer some closed multiple-choice questions about the child’s situation, and to explain their assessments and decisions in free-text form. The students’ individual answers were then aggregated, with the breakdown of the answers serving, in diagram form, as the basis for discussion in a seminar format. Students who had assessed a child with a Somali name were mixed in the seminar groups with those who had assessed one with a Swedish name, and the discussions were steered toward reflection on the differences in the assessments that the different names had occasioned.

The exercise described here was conducted at three Swedish universities, with a total of 176 social work students participating (university A, n = 72; university B, n = 39; and university C, n = 65). All the students were beginning their educational paths, and the exercises were conducted in conjunction with their taking courses about child protection. The seminars were replaced with focus groups with eight randomly selected students at each university, i.e., 24 students in all. As in the seminar groups, the focus groups were asked to reflect on the results of the individual assessments, with the difference that the moderator in the latter instances played a less obtrusive role.

This study is based on the material gathered in these focus groups along with the data aggregated from the individual exercises at the three universities. All focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed. The data were analyzed by summarizing, comparing, and contrasting the content themes from the groups (Miles & Huberman, Citation1984). Quotations from the transcripts are annotated with the group letter (i.e., university A, B, or C).

Key findings

In the first phase of the individual exercise, the social work students at the three universities were tasked with assessing whether a child needed emergency protection. The following, very limited information was available: The situation involved a 10-year-old boy living with both his biological parents and three younger siblings, which was brought to the attention of social services by a telephone call from an elderly neighbor. The neighbor reported having heard “noise” from the boy’s apartment on several occasions, with raised voices and slamming doors. On the most recent occasion, the neighbor encountered the boy on the staircase “late one evening.” The boy responded angrily when the neighbor spoke to him and left the building. When the social worker contacted the family by telephone to find out what had happened, the mother replied that “there wasn’t any danger” and that the boy had simply left the residence to pick up a homework assignment from a friend. The social worker was given no opportunity to speak with the child, since the mother indicated that he was “sick and asleep.”

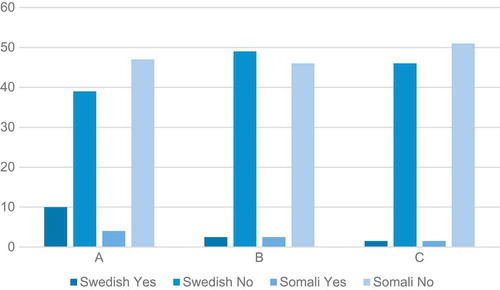

As shown in , only a few students at universities B and C determined in their individual exercises that the child needed emergency protection. Such assessments were somewhat more prevalent at university A, where the students considered the boy with a Swedish name to be in greater need of protection than the boy with a Somali name. When the students in the university A focus group were asked to explain this difference between the assessments of a child with a Swedish ethnic background and one with a Somali ethnic background, they noted that there could be different “tolerance levels” for families with different ethnic affiliations. In the case of the family of Somali origin, the high noise level might be perceived as being just a “natural part” of the culture, while a high noise level in a family with a Swedish ethnic background would be viewed as a warning sign:

The reason for the differences has to do with some students thinking that it is noisier in a Somali family … that it’s part of the culture. (A:2)

Figure 2. Children in need of emergency protection according to students at University A, B, and C (percentage).

Despite the limited background information, the focus group participants believed that, in many cases, the students assumed that violence was present in the family, but that the violence in the family with a Somali name was more tolerated by the assessors than was the violence in the family with a Swedish name:

There may be a different tolerance for violence in a Somali family. Against that background, the effect may be that we are more likely to protect the Swedish child than the Somali one. (A:1)

New information

After this initial assessment, the students were provided with additional information about the case. The family had been called in for a meeting with the child protection services. The father and son came to the meeting, since the mother was minding the three younger children, who were reportedly sick. The father reaffirmed the mother’s previous statement over the telephone, and also believed that the neighbor who had contacted child protection was “easily irritated.” Only after some persuasion did the father allow the social worker to have a private conversation with the boy. During this conversation, the boy reported that he had run out of the apartment because he was angry about having to watch his younger siblings. The father made it clear at the meeting that the family did not want any further contact with child protection. In addition to the information about this meeting, the students were given access to records showing that the family had not had any contact with child protection.

After receiving this new information, the students were tasked with deciding whether a formal child protection assessment of the family should be conducted. In preparation for this decision, the students first had to answer several questions, one of which concerned how they defined the type of risk to which they believed the child was exposed. The students were instructed to choose a maximum of three out of 18 predetermined categories to answer this question. Although the ethnic difference had initially had a limited effect on the assessment of whether the boy should be the object of an emergency intervention, that difference now had a clearer effect.

At university A, the risks to the child with a Somali name were described more often in terms of parenting style than was the case for a child with an ethnic Swedish name (17 versus 10), while deficient care and norm-breaking behavior by the child appeared more frequently in the assessments of the child with a Swedish name than for the child with a Somali name (31 versus 25). When the students in the focus group were asked to reflect on the diagrams showing these differences in their assessments, the discussion first turned to parenting style. Do we, they asked, tend to prejudge the parenting style of ethnic minority parents as problematic, while the problem in an ethnic majority family is judged either as a behavioral problem on the part of the child or a result of deficient care? Some students in the focus group problematized the report that had initiated the case, based on the concept of parenting style. They noted that parenting styles can vary between families with different ethnic origins, but it is not necessarily true that a parenting style that differs from that of the ethnic majority is consequently harmful to the child:

The neighbor reacted to the noisy discussions in the family and viewed this as improper parenting. But she may have made her report because this was not what she was accustomed to or thinks is right. (A:6)

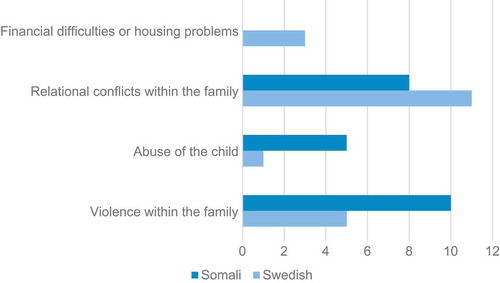

At university B (see ), the concerns about the boy with a Somali name had to do with violence, either violence within the family (10 versus 5 for the child with a Somali versus ethnic Swedish name) or abuse of the child (5 versus 1), while the risk assessment regarding the boy with a Swedish name more often pertained to relational conflicts within the family (11 versus 8 for the child with an ethnic Swedish versus Somali name), financial difficulties or a housing problem (3 versus 0). One student in the focus group summarized the results as follows:

When it’s about a Somali family it’s violence and abuse, but if they’re Swedish then the problems have to do with finances and housing. (B:6)

Another student at the same university offered a similar summary:

I think that we can read from this that if there is a problem in a Swedish family, it will have to do with, for instance, living in too close quarters … that is, external factors. If it’s a foreign family, then it’s abuse of some type. (B:5)

The students at university C who had conducted a risk assessment of the boy with a Somali name often chose to define their concerns using the categories of parenting style (20 versus 15 for the child with a Somali versus ethnic Swedish name), violence within the family (10 versus 6), and relational conflicts within the family (17 versus 11), while those who assessed a boy with a Swedish name cited neglect as a risk category more often (18 versus 12 for the child with an ethnic Swedish versus Somali name). The discussions in this focus group are reminiscent of those conducted at university A, and a number of students believed that it was necessary to maintain critical distance from the neighbor’s interpretation of the situation. For example, one student (C:5) explained that “the tone could be perceived as more aggressive because we are dealing with a different language,” while another student (C:8) summarized the group discussions by pointing out that “it is easy to impose Swedish norms on what is wrong in this particular family.”

The group-based conversations in these discussions eventually converged on the classic conflict between a cultural deficit tendency and a cultural relativist tendency, with one important issue concerning which culture-specific indicators signal that a child is exposed to risk and which such indicators have no significance with respect to a child’s safety. For example, some participants believed that giving a 10-year-old boy the responsibility of watching his smaller siblings deviated from a general norm in Sweden, but does assuming such responsibility actually constitute a risk to the boy?

The discussions in the focus groups also tended, at least to some extent, to go beyond the culturalization of the other that is common to both the cultural deficit and cultural relativist tendencies. For example, the focus groups touched in various ways on the arbitrary and unreflective use of terms such as culture, in which culture is turned into something that the minority, not the majority, has:

I didn’t see it as though I was assessing a Swedish family and I would presumably have made the same assessment [if I had assessed the Somali family]. (A:2)

But perhaps it was because you had a Swedish family that you didn’t think about it? (A:1)

Yes, perhaps. (A:2)

Another problematization in the focus groups pertains to the risk of making specious connections between ethnicity and culture, and to the importance of instead understanding that cultures are in a state of constant flux. For example, one participant reacted to the fact that so many students in the individual assessment phase made stereotypical assessments of the parenting style in the family with a Somali name:

We know nothing at all, actually. These parents could have come [to Sweden] when they were two years old, and they may not have any sort of “typical” Somali parenting style whatsoever. (C:1)

A gradual process: from “evaluation test” to reflection

The foregoing illustrates to some extent the discussions that arose in the three focus groups relating to the presentation of various diagrams summarizing the individual sessions. However, to make the account of the focus group discussions more complete, it is important to add that the insights related by the students arose during a process in which the discussion was initially defensive, as if the students were being subjected to an evaluative test, and then gradually became more reflective and self-critical. Particularly in focus group A and to a somewhat lesser extent in focus group C, the students initially expressed a sort of relief that the first diagram, which summarized their assessments regarding emergency protection, pointed to significant unanimity in the assessments of children with Swedish versus Somali names, as is illustrated in the following quotations from the student discussions:

I can sense relief that there is no major difference. (A:8)

Yes, in a way. It feels comfortable that there is no marked difference. (A:6)

No, it would have been awful [to have differences in the assessments]. (A:1)

Yes, just awful. (A:6)

It appears that the students in focus groups A and C initially understood the exercise to be an evaluative test. There is also a hint that the students had the idea that the simulation per se had a set answer, a set truth, with certain choices within the assessment process being more normatively worthy than others. In this context, their having not made any distinctions based on cultural factors confirmed that the students had, collectively and as future professionals, behaved correctly and were not governed by stereotypical preconceptions or categorizations.

Conversely, being suspected of not being culturally neutral was perceived, by the social work students, as threatening the values that social workers are thought to represent, preserve, and uphold. The focus groups showed that the students could feel uncertainty, and possibly discomfort, when they were expected to discuss cultural factors associated with child protection: “I don’t know what to say,” noted one student, “because it’s going to sound like I’m a huge racist” (A:4). There are also indications of concerns about being subjected, as a case manager, to review by others, with negative consequences: “How will colleagues or other people view what we’re doing here,” wondered one student, “could I be subject to review or looked upon differently because of this?” (B:2).

As noted, the defensive attitude of the students stood out as an initial phase in the focus group discussions, a phase that subsequently gave way to a more reflective and, in some cases, self-critical attitude. The successive comparisons between the assessments of a boy with a Somali name versus one with a traditionally Swedish name elicited new insights into the complexity of child protection cases and the significance of taken-for-granted starting points. This was reflected in the concluding discussions in the focus groups in statements such as these:

If I were to redo this assessment following our discussion, I would answer differently and discuss [things] differently. (B:2)

When you are making an assessment, you get into it and may not be thinking about what you’re doing. The discussion gave me a better understanding. (A:2)

When you’re making the assessment on your own, you rely on yourself. Then when you get to hear what others think, then it’s like … yes, that could also be the case. (A:2)

Discussion and conclusions

This study has investigated how a computer-based simulation, SimChild, can be used to give social work students insight into how their own beliefs and biases can affect their social work practice, and to enhance their cultural awareness. SimChild—a microworld of professional assessments and decision-making—is based on a specific combination of individual and collective activities. During an introductory phase, the students worked individually to make and explain professional decisions based on vague and contradictory data. All the students had access to the same case, in which the ethnicity of the children and families was varied, unknown to the students. In the ensuing seminars, the students discussed the aggregated results of the individual assessments to discern any patterns. The study used a case relative to preparing social work students for work in child protection, but any kind of simulated case can be used.

This study conducted at three Swedish universities demonstrates that using SimChild gave the students opportunities to develop their powers of critical reflection in three ways. First, the students were given an opportunity to become aware that they made different assessments and decisions based on the variation in the background circumstances (which here pertained to ethnicity, but could also have pertained to, for example, gender, socioeconomic status, or combinations of these variables). Second, the students were given an opportunity to discuss issues concerning why such differences in their assessments and decisions could arise. The question was then what underlying beliefs and biases produce these differences. Third, the students were given a chance to discuss whether a given indicator really signals that a child is exposed to risk, or whether the original risk assessments should rather be viewed as an expression of preconceptions.

Social work educators have long struggled with the difficulties of effectively fostering cultural awareness among students, i.e., insights into their own beliefs and biases and into how such preconceptions can affect social work practice. As noted above, two main challenges face social work educators in this context: integrating cultural awareness in all teaching and thereby demonstrating that it is central to all types of social work, and creating forms of instruction that enable students to discover their own biases, understand how these biases affect their social work practice, and, on that basis, develop more complex knowledge structures. SimChild was developed to address both these challenges.

Considering cultural awareness in just some of their courses does not help social work students understand that such competence should be inherent in all professional social work. The first challenge therefore concerns integrating cultural awareness into various specific knowledge contexts. SimChild is intended for use as an element of courses on child protection, and it is in this context that the students are given opportunities to discover how their own biases can affect their assessments and decisions. The focus group discussions reported here indicate that SimChild clarifies the role that unconscious biases play in such processes, and it is noteworthy that the discussions revealed a complex of problems comprising both cultural deficit and cultural relativist tendencies and, in turn, the difficult balancing act that sometimes characterizes current professional social work.

The second challenge has to do with realizing forms of instruction that enable social work students to discover their own biases and understand how they affect social work practice. The purpose of this article has been to illustrate how a computer-based simulation can accomplish something previously beyond the reach of traditional classroom instruction with lectures and seminars. We believe that the realism of such a computer simulation is a key precondition for such reflective processes to arise.

“Simulation” comes from the Latin simulare, which means to depict and thus refers to attempts of various kinds to approximate reality. SimChild and other simulations in advanced professional teaching programs are, of course, not intended to create exact models of professional contexts; rather, the idea is for these simulations to capture critical situations and processes that encourage reflection on professional practice. At the same time, the importance of points of agreement between the simulation and the actual professional practice should not be underestimated. As a working method, SimChild approximates, as noted above, the child protection methods used in Sweden and many other European countries. The simulation is therefore intended to provide a high degree of formal authenticity. It is also intended to provide a high degree of what we might call substantial authenticity. This means that the social situation of the children and parents involved in the fictive case must be described realistically, encompassing the contradictions and uncertainty that often characterize the material to which social workers have access when making assessments in child protection cases.

Formal and substantial authenticity are, as we see it, essential if the students are to immerse themselves in the simulation exercise. They are also essential if the ensuing seminars, which were replaced with focus groups in this study, are to illustrate, convincingly, the problems of interpretation that can arise in child protection assessments and reveal how the taken-for-granted beliefs of professionals affect their assessments and decisions.

Lastly, a climate of open discussion is an essential precondition for such an exchange of experience. The issues addressed are sensitive, and students do not want to be subjected to moral judgment, be it from their fellow students or their teachers. SimChild has in this regard one obvious advantage as a pedagogic strategy: the students do not primarily discuss one another’s individual assessments (although, in the present exercise, a substantial number of students were willing to share their reflections on their own individual assessments in the focus groups). The students come together around an aggregated and thus anonymized body of statistical material focusing on the tendencies within the entire group of students. This type of tolerant and open climate creates a space for the self-reflection that is indispensable in social work.

References

- Azzopardi, C., & McNeill, T. (2016). From cultural competence to cultural consciousness: Transitioning to a critical approach to working across differences in social work. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 25, 282–299. doi:10.1080/15313204.2016.1206494

- Blunt, K. (2007). Social work education: Achieving transformative learning through a cultural competence model for transformative education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 27, 93–114. doi:10.1300/J067v27n03_07

- Borell, K., & Egonsdotter, G. (2012). Om möjligheterna att replikera professionella utmaningar i lektionssalen: Datorbaserad simulering av barnavårdsutredningar. Högre Utbildning, 2, 47–49.

- Buckley, H. (2000). Child protection: An unreflective practice. Social Work Education, 19, 253–263. doi:10.1080/02615470050024068

- Carter-Black, J. (2007). Teaching cultural competence: An innovative strategy grounded in the universality of storytelling as depicted in African and African American storytelling traditions. Journal of Social Work Education, 43, 31–50. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2007.200400471

- Chand, A. (2008). Every child matters? A critical review of child welfare reforms in the context of minority ethnic children and families. Child Abuse Review, 17, 6–22. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0852

- Eldridge, W. D. (1982). Our present methods of teaching ethnic and minority content-why they can’t work. Education, 102, 335–338.

- Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 1–74.

- Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2013). Social cognition: From brains to culture. Sage.

- Garcia, B., & Bregoli, M. (2000). The use of literary sources in the preparation of clinicians for multicultural practice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 20, 77–102. doi:10.1300/J067v20n01_06

- Garran, A. M., & Werkmeister Rozas, L. (2013). Cultural competence revisited. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 22, 97–111. doi:10.1080/15313204.2013.785337

- Gredler, M. E. (2004). Games and simulations and their relationships to learning. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 571–582). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Hannerz, U. (1999). Reflections on varities of culturespeak. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 3, 393–407. doi:10.1177/136754949900200306

- Hepworth, D., Rooney, R., & Larsen, J. (2002). Direct social work practice: Theory and practice. California: Brooks/Cole.

- Heydt, M. J., & Sherman, N. E. (2005). Conscious use of self: Tuning the instrument of social work practice with cultural competence. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 10, 25–40. doi:10.18084/1084-7219.10.2.25

- Hollingsworth, L. D. (2013). Resilience in black families. In D. S. Becvar (ed.), Handbook of family resilience (pp. 229–243). New York: Springer.

- Johnson, Y. M., & Munch, S. (2009). Fundamental contradictions in cultural competence. Social Work, 54, 220–231. doi:10.1093/sw/54.3.220

- Kahneman, P., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Križ, K., & Skivenes, M. (2010). ‘Knowing our society’ and ‘fighting against prejudices’: How child welfare workers in Norway and England perceive the challenges of minority parents. British Journal of Social Work, 40, 2634–2651. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcq026

- Léveillé, S., & Chamberland, C. (2010). Toward a general model for child welfare and protection services: A meta-evaluation of international experiences regarding the adoption of the framework for the assessment of children in need and their families (FACNF). Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 929–944. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.009

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Munro, E. (1996). Avoidable and unavoidable mistakes in child protection work. The British Journal of Social Work, 26, 793–808. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a011160

- Nadan, Y. (2016). Teaching note—revisiting stereotypes: Enhancing cultural awareness through a web-based tool. Journal of Social Work Education, 52, 50–56. doi:10.1080/10437797.2016.1113054

- Nagda, B. A., Spearman, M. L., Holley, L. C., Harding, S., Balassone, M. L., Moise-Swanson, D., & De Mello, S. (1999). Intergroup dialogues. Journal of Social Work Education, 35, 433–449. doi:10.1080/10437797.1999.10778980

- Reinsmith-Jones, K., Kibbe, S., Crayton, T., & Campbell, E. (2015). Use of second life in social work education: Virtual world experiences and their effect on students. Journal of Social Work Education, 51, 90–108. doi:10.1080/10437797.2015.977167

- Salas, E., Wildman, J. L., & Piccolo, R. F. (2009). Using simulation-based training to enhance management education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8, 559–573.

- Sawrikar, P. (2017). Working with ethnic minorities and across cultures in Western child protection systems. New York: Routledge.

- Steiner, S., Brzuzy, S., Gerdes, K., & Hurdle, D. (2003). Using structured controversy to teach diversity content and cultural competence. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 23, 55–71. doi:10.1300/J067v23n01_05

- Stokes, J., & Schmidt, G. (2011). Race, poverty and child protection decision making. British Journal of Social Work, 41, 1105–1121. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcr009

- Sue, D. W., Bernier, Y., Durran, A., Feinberg, L., Pedersen, P. B., & Smith, E. J. (1982). Cross-cultural counseling competencies. The Counseling Psychologist, 10, 45–52. doi:10.1177/0011000082102008

- Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2003). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Tandy, C., Vernon, R., & Lynch, D. (2017). Teaching note—teaching student interviewing competencies through second life. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(1), 66–71. doi:10.1080/10437797.2016.1198292

- Tsang, A., Bogo, M., & George, U. (2003). Critical issues in cross-cultural counseling research: Case example of an ongoing project. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 31(1), 63–78. doi:10.1002/jmcd.2003.31.issue-1

- Warde, B. (2012). The cultural genogram: Enhancing the cultural competency of social work students. Social Work Education, 31(5), 570–586. doi:10.1080/02615479.2011.593623

- Wastell, D., Peckover, S., White, S., Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., & Pithouse, A. (2011). Social work in the laboratory: Using microworlds for practice research. British Journal of Social Work, 41(4), 744–760. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcr014

- Yan, M. C., & Wong, Y. L. R. (2005). Rethinking self-awareness in cultural competence: Toward a dialogic self in cross-cultural social work. Families in Society: the Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 86(2), 181–188. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.2453