Abstract

Grief over perinatal loss is a personal experience that has a lasting impact on the life of the surviving siblings. This retrospective study is an in-depth exploration of the symbolic construction of the bond with the lost sibling employing Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, a method to study sensitive themes. Our results have confirmed the strong social and cultural embeddedness of the grief experience. Participants of the study related perinatal loss to other major crises, conflicts, and overwhelming secrets in the lives of their families. Communication outside the family was often insensitive and stigmatizing, transforming bereaved children’s stories into silenced stories.

Introduction

This study discusses sibling grief over perinatal loss in the family from a retrospective view. Siblings’ experiences are analyzed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, a method to explore sensitive themes and interviewees’ meaning-making processes. We aim to describe how siblings could cope with the loss of an infant brother or sister; how they experienced the loss and their bereaved parents; and how it felt to them to remember their deceased sibling later in adult life.

Perinatal loss is defined as the death of an infant due to stillbirth or neonatal death: either a fetal death after 24 gestation weeks or death occurring before the first week of life (Kersting & Wagner, Citation2012). It often becomes a suppressed episode in the lives of families: mourning siblings, who are usually young children when confronted with the event, have to cope with a loss related to fundamental secrets of death, conception, and birth, which represent cultural or family taboos (Fanos et al., Citation2009). In late modernity, death is conceived as doctors’ business, whose knowledge and skills should triumph over the event (Ariès, Citation1974). Rituals that used to help cope with the loss by establishing a link between everyday realities and the transcendent reality of death, and by ensuring community support for the bereaved family, have largely disappeared (Ariès, Citation1974; Seale, Citation1998).

The loss of a sibling substantially changes family dynamics and attachment patterns (Clarke et al., Citation2013; Hughes et al., Citation2001; Leon, Citation1986; Rostila et al., Citation2017). Siblings do not only lose the deceased brother or sister but also their parents as they knew them before the loss (O’Leary & Gaziano, Citation2011). In the cases of perinatal death, family hopes for joyfully celebrating the new life turn into despair. When it happens, women often feel that “their bodies have failed” (Kersting & Wagner, Citation2012, p. 190) and blame themselves for the loss. Family members may be overwhelmed by unspoken doubts concerning their own generative potentials (McAdams, Citation2018). Ambivalence toward the mother’s pregnancy on part of the siblings is a further complicating factor. Siblings may blame themselves for the fatality that is uncontrollable and threatening (Simon, Citation2013). They lose their previous or aspired roles in the family and suffer from a hardly expressible loss, that of their trust in the future (Clarke et al., Citation2013; O’Leary & Gaziano, Citation2011). This “loss of innocence” (Funk et al., Citation2018, p. 13) is a dramatic change in one’s constructions of childhood experiences. Children may also miss their broad social network due to the isolating impact of grief.

The prevalence of complicated grief is the highest among parents who have lost a child—yet this is an under-researched area (Funk et al., Citation2018; Leon, Citation1986). Complicated grief (Shear et al., Citation2013) as a problem is discussed under various labels in the professional literature, such as prolonged or pathologic grief. The condition was included as Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder in the DSM’s fifth edition, Section III (Box 2). A recent proposal is to introduce Prolonged Grief Disorder with leading symptoms as identity disruption, emotional pain, and sensing life as meaningless (Boelen et al., Citation2020). Complicated grief occurs when death is unexpected, prolonged, or violent, the relationship to the deceased person is extremely close or dependent, feelings about the deceased person are highly ambivalent, the deceased person is a child or is young, the event is a repeated element of preceding traumatic losses, and there are co-occurring major stress factors. The lack of social supports and adequate cultural practices, such as death and mourning rituals, survivor’s self-blame, their poor physical or mental health, and the absence of information on the circumstances of the loss are further precipitating factors (Shear et al., Citation2013; Simon, Citation2013; Pilling, Citation2003). Most of the above conditions are present in perinatal loss.

Method

Interpretative phenomenological analysis to explore sensitive data

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) is a relatively new method for the in-depth study of individuals’ lived experiences and meaning-making processes. IPA is committed to idiographic approaches by focusing on the uniqueness of individual experiences, often on existential matters: “IPA is attempting to put the heart back into (and alongside the head in) psychology” (Eatough & Smith, Citation2013, p. 186). The method is sensitive to sociocultural factors (Brocki & Wearden, Citation2006; Eatough & Smith, Citation2013). IPA’s approach is an attempt to grasp the complexity that Hänninen (Citation2004) described in her model of narrative circulation. Three types of narratives, the public (told) story, the historical, lived facts, and the domain of not-yet-said (Rober, Citation2002) or unspeakable inner narratives, representing one’s meaning-making processes in progress are integrated into a circular process. Narrators rely on cultural, situational, and personal (experiential) storying resources when constructing their stories. The not-yet-said may manifest itself in the disclosive space established during an IPA interview (Kassai, Citation2020; Rácz et al., Citation2016, Citation2018). The ongoing process of meaning-making is revealed in speakers’ narratives by the chaotic temporal relations, a fragmented sentence structure, halts, and unnecessary repetitions (Ehmann, Citation2002; Neimeyer, Citation2000).

Sample

An IPA sample is usually homogenous and is relatively small: suggested numbers range between 1 and 30 (Eatough & Smith, Citation2013). All the respondents included in this study either experienced the loss of a sibling directly or had indirect experiences on the impact of the loss in the lives of their families. Participants were recruited by the first author through her professional network. The pandemic situation and some cultural traditions rendered data collection difficult. “Of the dead, say nothing but good” as a notion, together with the suppression of emotions as a cultural expectation sometimes resulted in very brief comments. Detailed information on the 20 interviews selected for the analysis can be accessed at the data repository under the title Interview data. The sample included 8 male and 12 female respondents, with an age range between 23 and 63 (M = 37.35; SD = 11.73). The average length of the interviews was M = 23.28 min (SD = 11.32), with men speaking less (M = 19.85; SD = 10.22) and women, more (M = 25.55; SD = 11.86). A debriefing conversation and further counseling opportunities were made available for those who wished. Ethical approval for this study was issued by Szociális Kutatásetikai Bizottság (Social Research Ethics Committee, University of Pécs, Hungary), under the number 2/2019.

Interviews

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted in the interviewees’ homes by the first author. The language of the interviews was Hungarian. Respondents were encouraged to show some reminders (photos, drawings, etc.) if they wished. First, every interviewee responded to the following question: “Please tell me the story of the loss of your sibling” (same as in Funk et al., Citation2018, p. 2) and they could relate their experiences freely. Subsequent themes included parental grief, the impact of the loss on the surviving sibling’s life, transgenerational impacts, and possible coping strategies. The interviewer was open to any emerging new theme during the conversation. All the interviewees consented to audio recording, to a verbatim transcription of their texts, the use of anonymized data, and the publication of the results.

Analysis

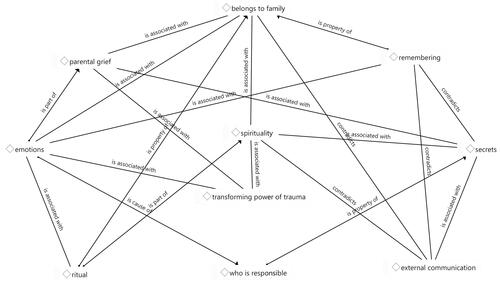

We read through and re-read the interviews several times, made our initial comments, and discussed them in detail. We laid special emphasis on the openness of our interpretations and avoided “evident” clinical interpretations as much as possible (the analysis itself preceded the literature review on the theme). We adhered to IPA’s double hermeneutic (Kassai, Citation2020; Smith & Osborn, Citation2003), asking the interviewees to interpret their own experiences, and then we interpreted their understandings. First, we identified the emerging themes, and then, on a more abstract level, we determined several master themes that were central to our interpretations of the participants’ meaning-making processes (). A final step involved connecting our findings to previous research results. There does not seem to be consensus on the use of a software solution for qualitative data analysis with IPA projects (Copteros et al., Citation2017; Kassai, Citation2020). We followed the routine employed by Copteros et al. (Citation2017) and used a paper-and-pen method first. In the next hermeneutic cycle, we returned to the emerging comments and themes using ATLAS.ti 8 for Windows to build an integrated, visualized interpretation—a conceptual network—of our findings ().

Table 1. Comments, emerging themes, and master themes.

Own source.

Results

The excerpts meant more than illustrations, disclose the thematic relations within the texts. We adhered to the original verbatim transcriptions in the translations, even when these were not fully grammatical. Confusion and chaos in the narrative reflect the intensity and the lack of integration of one’s traumatic experiences. Frequent changes to present tense when speaking about a past event are interpreted as reliving the experience and establishing a narrative position for corrective emotional experiences (Ehmann, Citation2002; Neimeyer, Citation2000).

Spirituality

Every narrative comprised some spiritual orientation, which was manifested as a religious belief in God, a transcendent experience, and searching for meaning in one’s own life. The lost sibling as a soul or angel exists in a different dimension:

MGA: and I remember the sermon, and I could conclude that whether or not he lives, he is with us, he exists, and … those who stayed here have a task, a mission in life to fulfil.

MBM: he lives, but not here, with us on Earth … he watches us from above and protects us as a blessed soul … so to say, a saint. Not a canonized saint but he is in Heaven, and … and … and he knows that he belongs to us, and we belong to him.

FKE: and he asked me if I believed in God. And I … I remember clearly (…) that I answered yes, I do, but I hate Him.

In some cases, the elder sibling proposes a name for the baby. This responsible act (“nomen est omen”) is often characterized by some spiritual features, e.g., the name is revealed by a natural phenomenon or by a dream:

FKE: My parents asked me what my sister’s name should be … I was standing in the balcony … or perhaps not in the balcony but just in front of the window, but, yes, perhaps in the balcony, and it was summer, the sun was shining, and I said that the sunbeam was caressing me. So, they asked me if the name should be Sunbeam. “Yes, Sunbeam”—so in fact, really, I gave her this name.

MGA: My Mum was not even pregnant at that time, and I had a dream that a brother is born and then disappears. All that remained, all I could remembered when I woke up that he was a boy. And his name was Péter … the days passed, and we were thinking about giving a name … and they were mostly considering girl names and thought that István would do for a boy. And I said not István but Péter. (…) God prepared me for it…

Dreams are traditionally perceived as a connection to the other world, and are a means to get to know the lost sibling who was stuck in the other world:

FKE: I could see her in my dreams. I could imagine her with long brown hair as my brother’s; but hers was curly, with brown eyes.

An apparition-like scene performs a similar function to dreams. The following story is told in a distancing and ambiguous manner (“rounded up a romantic story”). The storyteller does not judge the story as rational; in the Hungarian culture seeing an apparition would not be considered “normal.” Openly, he conforms himself to everyday shared realities; but on a spiritual level he still seems to believe in the reality of the experience and uses it to connect to his brother and cope with the loss:

MVS: and then she (mother) was pushing my baby buggy to the windows of a toy store and I was just looking at the window (…) and I could see a little rag dog there, I laughed and pointed there, saying Geegő, Geegő (lost sibling’s name, baby talk); and somehow I rounded up a romantic story that perhaps I might have seen my brother in some way (…) I could see a small child, my own brother.

The lost sibling belongs to the family as a person. Continuing bonds

Suspecting some medical malpractice is present in several interviews. The strong wish to identify the person who is responsible for the loss is an expression of indestructible family bonds. The perspective of the medical staff and that of the close relatives are very far from one another. For MGA, his baby brother was a family member, while the hospital staff treated him as a non-person—in MGA’s view, in a mechanical and inhumane way. FCzl, sharing her mother’s vivid memories about the harsh medical treatment, related a circumstance that is especially difficult to confront:

MGA: and then I told my Dad… I only wanted to put it all off … that I wanted to see the baby. I don’t care what they (i.e., medical staff) say now, I want to see him. And my Dad asked them to let us see him but they did not allow … did not allow to, what I … I … and this was the other day, the story when (…) when they told us that we could not see him, and I was very, very, very angry and I just could not understand why it happened this way. (…) A child is born, and they know that he has no chance to survive, they just put him in an incubator and neither his mother, nor his father, nor his siblings can see him … not even when … when they explicitly ask for it … why is it better for this child to suffer alone … why not … if he has to die it is not the same … to die in the arms of loving family members. And I … this has been very painful for me that … if they in the hospital condemned him to die … if … he had injuries, or … I cannot decide if these were the results of some malpractice during delivery (…) whether or not they made a mistake during delivery, they surely made a mistake when they let that child, my brother, die without ever feeling the loving arms.

FCzl: My mother told me about it several times, in a bloodcurdling way. How he (the baby) was thrown into a bucket after the delivery, and she could hear the hard knock.

The idealization of the lost sibling is a sign of complicated grief and a dysfunctional defense against the perception of the vital threats related to perinatal death:

FKE: My mother was not interested in suing the doctor (…) as she would not have her baby back, she could not even think of that, for many years … but I would need to know what happened and, uh, yes, I do want someone to be punished for what they did, ruined our lives (…). Yes, she (the lost sister) was beautiful, she was perfect. (…) they piled up lies in the necropsy report that she had been ill but not, but not, this was impossible.

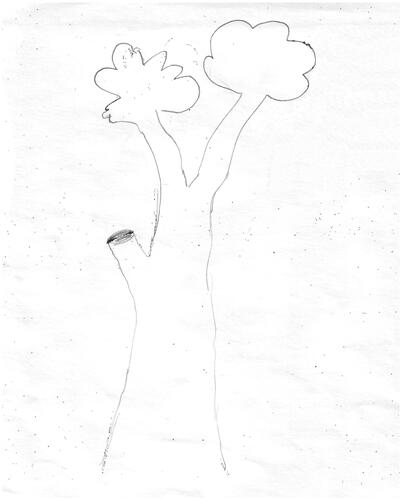

Children’s drawings are very telling about this bond and the related emotions. Two of the interviewees could remember these drawings. In MBM’s picture of a sick tree (=family), one branch had to be cut off and the remaining two branches are healthy. The cut surface resembles a very sad baby face with dark black eyes and a downturned mouth (, data repository).

MBM: I drew a tree that had three branches – I was there then, and my second, now my second brother was the youngest one then, so we were the two brothers who lived, and I drew a tree with three branches, and one of the branches was cut off almost at the base, and I remember that it was covered with concrete.

The interviewee explains that in the cities, concrete is used for protecting the trees after cutting the branches. Instead, concrete is used for covering the roots of a tree growing near the pavement—and for tombstones. The roots often break the cover what symbolizes an imperfect burial ritual and its impact on the survivals’ lives. The interviewee as a young boy represented his deep worries concerning the lack of burial (the hospital cremation) in his picture.

The presence of a phantom sibling is a sign of complicated grief. In these cases, parental attachment to the lost sibling is maintained and has a lasting and profound impact on the survivor sibling’s life (Davidoff, Citation2012; Hughes et al., Citation2001).

FKE: We were shopping with my mother, a kind of girlie evening or girlie afternoon in the mall (…) she (the mother) said that she had had a feeling as if she had been missing something, and she knows that she should have been walking and shopping there with her two daughters (sobbing voice).

Interviewees also had fantasies about the continuation of the lost sibling’s life in this world:

MOD: it would be so cool…as a 20-year-old boy he would also come and skateboard or ride a bicycle with us.

FPI: I was an adolescent boy with all these rebels and I wished my brother hadn’t died. I always mentioned him as my younger brother and not simply a sibling. This is how he was closest to me.

In the next excerpt, MVS points out the family responsibility for the life of their children. This is an uneasy topic and the speaker’s mixed feelings are expressed in repetitions and distancing generalizations (“anyone”; “thing”; “you”; “our psyche”). While he wants to avoid blaming her mother, he emphasizes the possible role of family conflicts in fatality. This is a very painful way of regaining control over uncontrollable events. Following this logic, however, he makes the most of his father’s sacrifice, who, as an alcoholic, gave up drinking for his family when MVS was born. FCzL raises a similar issue in a more straightforward manner:

MVS: I can even imagine that the, the, the … the, the first … uh, fetus was aborted because of this psychological pressure although I cannot tell you why … and that uh, uh, uh, Gergő who knows why … I don’t believe in things happening by chance. There is no such a thing as chance … I think, uh, I do not want to claim that … you cannot decide on a nuchal cord but, but I think our psyche does very strange things sometimes. And … and I want to be properly understood. I do not want to blame my mother as … as I do not think anyone would want to blame the mother for a birth fatality, but who knows, perhaps the child himself, that is, Gergő might have received some impressions and, as a result, he did not want to be here. (…) now we are discussing very fluid things.

FCzL: I used to resent my mother for not being careful enough and not protecting the little fetuses more.

The idea that the lost sibling exists in another world and sometimes connects to this world (watches) but does not interfere is possibly a source of consolation. It is worth noting that the positive contents are described in negative terms, which refers to the speaker’s previous negative expectations and ambivalence (Colston, Citation1999). For FCzL, these negative connotations are explicit:

MVS: (…) it is possible that … that, that in a way he sometimes appears but does not interfere with this world … just as if he would have a look at us, “yeah, this is it here, you are here, and it is all right.” … No … I cannot feel that he would be filled with anger, that is, if I think of Gergő, I cannot feel that there would be any pain but (…) I could never experience that he would be angry for “I could not live”.

FCzL: I thought that they were angry with me because I live, and they don’t.

Parental grief and emotions

Parental grief has a profound impact on the surviving children. They are insecure about or feel threatened by their parents’ emotions. Suppressed emotions and rumination are particularly harmful. If the parents pretend indifference, then the children may think that a child’s life does not matter; or showing one’s emotions is improper. If the parents are immersed in eternal grief, then they become emotionally inaccessible for the surviving children.

FKE: … and then I used to live with my grandparents for about a year, with one or the other. The ones who did not care about me cared about my mother. She, she did not want to get out of bed at all except when she went to the cemetery, and she used to spend all her day either in the cemetery or lying in her bed at home. While she was at home, someone was always around watching as she had grave suicidal thoughts. She thought that I had my father to stay with me and she could go with my sister so that she would not be alone. Practically, she would have left me if she had been able to. (…) (speaking about a photo she is showing) I have the same empty glance as my mother has … truly, my pain is not mine; but what my parents have experienced. Their pain is mine, in reality.

Suppression is a common reaction: FHM: “she (the mother) never used her name when speaking about her. She said the little girl instead. Perhaps this could have been more painful for her.”

When the family can share the burden and accept their own as well as each other’s feelings they can heal from the loss and appreciate the new gifts in life:

MGA: We spent our pocket money and bought shoes, a toy watch, and the like for him … we spent all our money on these … and now all these had to be removed. My father came in and said that we had to tidy up these, so that when Mum comes home these should not be around. … and then we tidied all up and took them to the attic … these were hard days (…) I remember when she came home we were sitting in the living room together and were crying very, very heavily (…) I think she is okay, okay now (…) one can see it when she is playing with her grandchildren so happily. It makes her so very happy. I think it had been a big burden on them that my elder brother got married rather late, just like me, and they had thought that they would not have any (grandchildren) at all.

The transforming power of trauma. External reactions

The trauma of perinatal death is embedded in a family context, making each case unique. Previous traumatic experiences in the family and the way families responded to these events are explicitly related to surviving siblings’ memories of perinatal death in their narratives. Although these traumatic events and circumstances, such as unjust imprisonment in the state socialist era in Hungary, extreme poverty, family conflicts, and parental substance use do not seem to be directly related to the death of the sibling they are closely connected in the interviewees’ reasoning:

MGA: ‘85 was a difficult year in our family, as my father that year (…) it happened well before my sister was born when suddenly over … suddenly he disappeared from home. (…) as a child I only knew that they made my father disappear and nobody could tell me where he is (…) a considerable theft happened in the area (father’s workplace) and my father reported it to his boss and his boss responded briefly that he should not have reported it at all. (…) he (father) was prosecuted and imprisoned (…) she (mother) did not get any information (…) I only knew that there was some big trouble, and I was terrified that I might be taken to child custody. (…) and then my sister was born and I was very happy as this was the only source of joy, this was how we could get away from those events (…) of course we knew that our parents love their children very much but we, the children also told them that we would like it (have a baby in the family again) (…) not consciously, but I wanted another happy, unclouded period after the so many years that had been so hard to survive.

Perinatal loss dramatically changes family roles and identity aspirations. Surviving children do not find their place in this changed setting. Parentification—when the child attempts to take care of the parents and siblings—is quite frequent in these families. Loss of hopes and aspirations concerning their new sibling roles are further complicated by the anxieties concerning their own life, health status, and finally their own parenthood. For these children, the crisis experience is captured in the idea of “I did not know where my place was.” In some cases, parents want to replace the deceased infant by giving birth to another child:

FKE: They were sitting on the chairs beside the coffin in the funeral home. One of my grandmas on one side and the other grandma on the other side… and my parents were just standing beside the coffin, and I went from one of my grandmas to the other as I did not know where my place was and what I should do (sigh) and then, then, of course, I went to my mum.

MGA: He said that I should help her pack her things because she had not been prepared for this and we talked about these things together, toilet paper, toothbrush, pajamas and everything, and my first task was to call my father to come home. And … then … I was a child and there were no mobile phones in those days (…) and I was clever enough to tell my father “Come home, there is trouble (He had to repeat the call) …” and then my father came very quickly and took my mum and I stayed at home with my younger sister, and I told her “yes he is going to be born but look, you should not be happy about it yet” that is, I surely did not handle the situation very well for her … but I wanted to tell her not to be happy … so this is what I said to her “just don’t you be happy, don’t be happy”.

FRG: When anyone refers to her (the lost sister) they use my name. This would have been her name, but it is not clear if she got the name officially or they had just wanted it; and I don’t know either if these babies are registered. An absolute role confusion… my parents must have felt this as I soon got a nickname, and everybody used that.

The external validation of the family experience was largely missing, and perinatal death was often commented in an awkward, insensitive, and even offensive manner by outsiders:

MGA: In September, the headmaster asked if my brother had been born and I was upset and said that he had died … .and there was a big silence, he did not ask me anything else and I did not answer (…) and the headmaster said, and this made me extremely upset, that it was better for him as “your family” would not have been able to raise him anyway.

A long-term impact of the mother’s complicated grief (manifested in her suicidal ideations) on the surviving sibling is existential doubt, the denial of own existence as a value, derealization, and a “frozen,” eternal trauma. The surviving sibling knows that she should not feel the way she does, but this rational knowledge does not help her:

FKE: I was a too early child, and this should have come later, and this is how the whole thing could have been all right if she had been the first one and no problem could have happened this way … no, I do not blame myself as I am not responsible for it; neither they (the parents) are responsible for it. Only, only I feel that this is what could have been all right. (…) No, I do not feel guilty because I live, and she does not but I … I would prefer if she lived as it would be so much better (…). This … this is a story that has always been there and will always be there and often when I am thinking of it I am shocked that the story I am telling you is really my life.

Discussion

The stories we analyzed were about losses that had happened decades ago. The perinatal loss in the family is a life-transforming experience for the surviving siblings. This was reflected in the contents of the stories as well as in the fragmentations in the narratives. The master themes identified in our analysis bear much resemblance to the main themes found in other resources (Fanos et al., Citation2009; Funk et al., Citation2018; Kempson & Murdock, Citation2010; Meyer, Citation2015), such as a strong spiritual orientation (guardian angel, celestial afterlife, sensing a presence) and speakers’ efforts at meaning-making. We could identify a continuing bond, in which the sibling lives. A change in family relations as well as in aspired roles and identities was also characteristic of the texts. The results echoed an earlier finding by Neimeyer et al. (Citation2006): strong continuing bonds predict distress “only when the survivor was unable to make sense of the loss in personal, practical, existential, or spiritual terms” (p. 715). In our sample, meaning-making is a central element in the narratives and is often successful in existential-spiritual or even in personal dimensions, but much less in practical terms. The cause of death—a practical question related to possible genetic risks, personal responsibilities, and legal liability—was usually not clear for the bereaved siblings. This could be a result of the information management techniques of “soft” dictatorships, where the retention of information, a form of social control, is used to infiltrate the entire society.

At this point, however, we must note that even if the bereaved siblings could acknowledge the lost sibling as a person and a family member, they did not have time to establish a bond in real-life settings—only in their imagination. This may add to the existing confusion (Meyer, Citation2015). Meyer distinguishes between continuing and symbolically constructed bonds that are often private, and bereaved siblings take active efforts to turn them into a shared family reality. To establish this type of shared family reality, the dead infant must be named, seen, buried, and then remembered. In contrast with earlier conceptions, a continuing bond may have a positive role in the grieving process (Neimeyer et al., Citation2014); but is this so with constructed bonds? The constructed bond seems vital for the surviving siblings, for whom the bond is evidence that a child cannot simply disappear from the family as if s/he had never existed. For the parents, who have different worries concerning their own generativity, constructed bonds may not be reassuring. Studies on the theme are available but the results are contradictory; some authors suggest establishing the bond while others argue that this is a possible source of long-lasting depression and anxieties (Kersting & Wagner, Citation2012).

Neimeyer et al. (Citation2014) claim that grief is not primarily an intrapsychic but an interpersonal process, a socially constructed response to environmental events. Several studies refer to bereaved siblings as “forgotten mourners” (Kempson & Murdock, Citation2010, p. 740.) Death and mourning are natural experiences in life, and pathologizing natural human experiences may make more harm than good. Kempson and Murdock (Citation2010) found that communication toward the bereaved siblings was not responsive to their unique needs, attempting to isolate them from their own grief experience. They cite Devita-Raeburn (Citation2004) “Validation is in short supply when a sibling dies. (…) the less validation, the more ambiguous the loss, the more frozen the grief” (p. 31). In the siblings’ narratives, we could often identify a dissonance between speakers’ rational, culturally affirmed understandings and the underlying emotions: pain, confusion, self-blame, and resentment.

Clinical implications

Neimeyer et al. (Citation2014) highlighted the importance of community and cultural resources in the grieving process. Improvements in public attitudes via awareness raising could promote the validation of siblings’ experiences and the creation of a broad supporting network.

Many of the iatrogenic effects mentioned in the narratives, such as disrespecting patients’ rights and communicating in a highly technical, indifferent, or even offensive manner to them are less likely in a present-day Hungarian hospital setting. Progressive professional guidelines have been introduced to protect the families from the destructive consequences of the loss (SZNSZK & OGYEI, 2010). The implementation of the guidelines and practices greatly depends on the organizational culture of the given institution. Bereavement rooms should have been established in every hospital, but this has not happened so far. Further, bereaved families are only incidentally informed about their rights to the fetus’ burial.

Providing grief counseling/therapy to families with perinatal loss is a way to promote post-traumatic growth and the appreciation of life (Kempson & Murdock, Citation2010). In Hungary, a unique system of health visiting was established in 1915 (Magyar Védőnők Egyesülete, Citationn.d.). The visitors, specialized in maternal and child health care, have a continuous and long-term relationship with the families. They could assist them to cope with the loss and refer them to specialized care when needed; but presently, health visitors are not trained to intervene in these family crises. Further, psychotherapy and counseling services are not available everywhere in the country and are only rarely covered by one’s health insurance. Most of the accessible services are delivered in private practice.

Transformations in legislation are relatively quick but access to services and the organizational culture of health care institutions improve more slowly. Changes could be achieved via service development and monitoring the implementation of the existing guidelines and regulations. Targeted training programs about the perinatal loss in the family and its potential impact on the bereaved siblings could be introduced to assist the hospital staff as well as the health visitors in gaining a more holistic understanding of the uniqueness and fundamental life-transforming power of this woeful family experience.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing their stories with us.

Disclosure statement

There is no potential competing interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the library repository of the University of Pécs at https://pea.lib.pte.hu/handle/pea/24829.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Agnes Y. Bornemisza

Agnes Yvette Bornemisza is an Instructor at the Department of Health Visiting and Prevention, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pécs, Hungary. She is a Ph.D. student in the Doctoral School of Health Sciences at the University of Pécs. She is a qualified health visitor, grief counselor, and fairy tale therapist. Her area of research interest is sibling grief over perinatal loss.

Rebeka Javor

Rebeka Javor, Ph.D. is Assistant Lecturer in Developmental and Personality Psychology at the Department of Community and Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Pécs, Hungary. She is a member of the Social Innovation Evaluation Research Center at the University of Pécs. Her main area of research interest is identity development.

Marta B. Erdos

Marta B. Erdos, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in Mental Health and Clinical Social Work at the Department of Community and Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Pécs, Hungary. Before starting her academic career as a lecturer and qualitative researcher in 2000, she used to work as a counselor at an out-patient crisis intervention center. Her main area of research interest is identity transformations.

References

- Ariès, P. (1974). Western attitudes toward death from the middle ages to the present. Johns Hopkins University Press. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.20658

- Boelen, P. A., Eisma, M. C., Smid, G. E., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder in section II of DSM-5: A commentary. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1771008. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1771008

- Brocki, J. M., & Wearden, A. J. (2006). A critical evaluation of the use of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) in health psychology. Psychology & Health, 21(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320500230185

- Clarke, M. C., Tanskanen, A., Huttunen, M. O., & Cannon, M. (2013). Sudden death of father or sibling in early childhood increases risk for psychotic disorder. Schizophrenia Research, 143(2–3), 363–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.024

- Colston, H. L. (1999). “Not good” is “bad” but “not bad” is not “good”: An analysis of three accounts of negation asymmetry. Discourse Processes, 28(3), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539909545083

- Copteros, A., Karkou, V., & Palmer, T. (2017). Cultural adaptations of dance and movement psychotherapy experiences: From a UK higher education context to a transdisciplinary water resource management practice. In V. Karkou, S. Oliver, & S. Lycouris (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of dance and wellbeing (pp. 681–698). Oxford University Press.

- Davidoff, L. (2012). Thicker than water. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199546480.001.0001

- Devita-Raeburn, E. (2004). The empty room: Surviving the loss of a brother or sister at any age. Schribner.

- Eatough, V., & Smith, J. A. (2013). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In C. Willig & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 179–194). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555.n12

- Ehmann, B. (2002). A szöveg mélyén [In-depth text analysis]. Új Mandátum.

- Fanos, J. H., Little, G. A., & Edwards, W. H. (2009). Candles in the snow: Ritual and memory for siblings of infants who died in the intensive care nursery. The Journal of Pediatrics, 154(6), 849–853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.11.053

- Funk, A. M., Jenkins, S., Astroth, K. S., Braswell, G., & Kerber, C. (2018). A narrative analysis of sibling grief. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 23(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2017.1396281

- Hänninen, V. (2004). A model of narrative circulation. Narrative Inquiry, 14(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.14.1.04han

- Hughes, P., Turton, P. P., Hopper, E., McGauley, G., & Fonagy, P. (2001). Disorganised attachment behaviour among infants born subsequent to stillbirth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(6), 791–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00776

- Kassai, S. (2020). Using interpretative phenomenological analysis to assess recovery processes. L’Harmattan.

- Kempson, D., & Murdock, V. (2010). Memory keepers: A narrative study on siblings never known. Death Studies, 34(8), 738–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481181003765402

- Kersting, A., & Wagner, B. (2012). Complicated grief after perinatal loss. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/akersting

- Leon, I. G. (1986). The invisible loss: The impact of perinatal death on siblings. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 5(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674828609016738

- Magyar Védőnők Egyesülete (n.d). Védőnők az egészséges és boldog családokért [Health visitors for the healthy and happy families]. https://mave.hu/index.php.

- McAdams, D. P. (2018). “I am what survives me”. Generativity and the self. In J. A. Frey, & C. Vogler (Eds.), Self-transcendence and virtue. Perspectives form psychology, philosophy, and theology (pp. 251–273). Routledge.

- Meyer, M. C. (2015). Sibling legacy: Stories about and bonds constructed with siblings who were never known [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Cincinatti, OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. http://uclid.uc.edu/record=b6048073∼S39

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2000). Narrative disruptions in the construction of the self. In R. Neimeyer & J. Raskin (Eds.), Constructions of disorder (pp. 207–241). American Psychological Association.

- Neimeyer, R. A., Baldwin, S. A., & Gillies, J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600848322

- Neimeyer, R. A., Klass, D., & Dennis, M. R. (2014). Mourning, meaning, and memory: Individual, communal, and cultural narration of grief. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in positive and existential psychology (pp. 325–346). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0308-5_19

- O’Leary, J. M., & Gaziano, C. (2011). Sibling grief after perinatal loss. Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health, 25(3), 173–193.

- Pilling, J. (Ed.). (2003). Gyász [Grief]. Medicina.

- Rácz, J., Kassai, S., & Pintér, J. N. (2016). Az interpretatív fenomenológiai analízis (IPA) mint kvalitatív pszichológiai eszköz bemutatása [Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) as a qualitative research tool in psychology]. Magyar Pszichológiai Szemle, 71(2), 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1556/0016.2016.71.2.4

- Rácz, J., Kassai, S., & Kaló, Z. (2018). A kvalitatív pszichológia új szenzibilitása: Előszó. The new sensibility of qualitative psychology. Magyar Pszichológiai Szemle, 73(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1556/0016.2018.73.1.1

- Rober, P. (2002). Some hypotheses about hesitations and their nonverbal expression in family therapy practice. Journal of Family Therapy, 24(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00211

- Rostila, M., Berg, L., Saarela, J., Kawachi, I., & Hjern, A. (2017). Experience of sibling death in childhood and risk of death in adulthood: A national cohort study from Sweden. American Journal of Epidemiology, 185(12), 1247–1254. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww126

- Seale, C. (1998). Constructing death. The sociology of dying and bereavement. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511583421

- Shear, M. K., Ghesquiere, A., & Glickman, K. (2013). Bereavement and complicated grief. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(11), 406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0406-z

- Simon, N. M. (2013). Treating complicated grief. JAMA, 310(4), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.8614

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2003). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 51–80). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Szülészeti és Nőgyógyászati Szakmai Kollégium, & Országos Gyermekegészségügyi Intézet (2010). A Nemzeti Erőforrás Minisztérium szakmai irányelve a pszichológiai feladatokról szüléshez társuló veszteségek során [Professional guidelines by the Ministry of Human Resources on psychological interventions related to perinatal loss]. Hivatalos Értesítő. A Magyar Közlöny Melléklete, 104, 15246–15258.