Abstract

Communication related to intergenerational trauma has the potential to mitigate the health impact of traumatic exposures for caregivers and also to prevent traumatic exposures and chronic stress for offspring. Pediatricians reviewed a generational trauma card (GTC), a graphic depicting generational trauma transfer and strategies to address the health effects of trauma exposure, with 21 adolescent mothers in a primary care clinic. On a Likert scale of 1–5, participants rated high interest in learning about generational trauma (4.2), likelihood of sharing the information with others (4.6) and potential of making changes in their life based on the information (4.5).

The well-researched link between traumatic exposures and poor health and developmental outcomes across the lifespan (Anda et al., Citation2006) has been a call to action for healthcare institutions to incorporate the science of adversity and trauma into routine clinical practice (Garner et al., Citation2012). National medical organizations, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, have advocated for screening for childhood traumatic exposures during primary care visits; however, screening alone has not been shown to lead to increased resource utilization and improved patient health outcomes (Loveday et al., Citation2022). Education can be an important alternative or complement to screening; the impact of education on behavioral change is well documented (Arlinghaus & Johnston, Citation2018 Mar-Apr; Street et al., Citation2009). There is a paucity of research, however, on best practices to educate patients and families on adversity and trauma and limited data on whether patients and families would find educational interventions related to trauma and stress acceptable in a primary care setting.

Education related to intergenerational trauma is of particular importance, as it presents the opportunity to promote the health of two generations. There are four models to describe how trauma can be transmitted generationally, the psychodynamic, family systems, sociocultural, and biological models (Kellerman, Citation2001). Together these highlight that the traumatic impact of caregiver adversity exposure can be transferred to children relationally, through caregiver mental health and parent-child interactions (Black et al., Citation2002; Isobel et al., Citation2019).

Given the high adversity burden in adolescent parents, their children are at heightened risk for unfavorable health and developmental outcomes due to the intergenerational transfer of trauma (Hillis et al., Citation2004; Hodgkinson et al., Citation2014). Therefore, teen-headed families represent an optimal population to educate regarding trauma and health outcomes. This study examined adolescent parent acceptance and assessment of an educational intervention focused on intergenerational transfer of trauma.

Methods

The study was conducted in the Healthy Generations program, a teen-tot primary care medical home for adolescent parents aged 13–22 and their families, located at Children’s National Hospital. The Healthy Generations program provides primary medical care, social work, and mental health services to teen parents and their children. It has been recognized by the Department of Health and Human Services as an evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention program (Cheng et al., Citation2022).

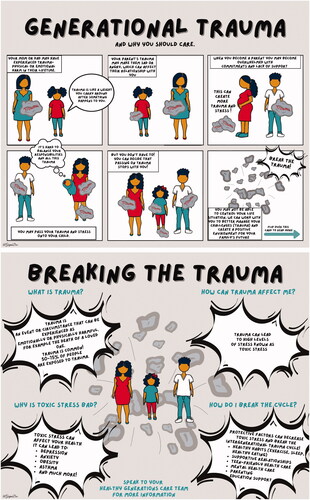

A Generational Trauma Card (GTC) () was developed by healthcare providers of the Healthy Generations program who have collective expertise in working with teen parents and developing education in trauma-informed care (Chokshi, Chen, et al., Citation2020; Chokshi, Walsh, et al., Citation2020). The GTC was developed in accordance with research demonstrating that integration of pictures with simple text in health communications can increase attention, facilitate comprehension, and mediate behavior change (Houts et al., Citation2006). The content of the GTC represents the family systems and psychodynamic models of intergenerational transfer of trauma, highlighting that trauma can be passed through interpersonal relationships and enmeshed patterns of communication (Isobel et al., Citation2019). The front side of the GTC has six panels portraying the generational transfer of trauma from adolescent parent to child. Trauma is graphically depicted as a rock or weight that a person carries around with him or her after a defining event. The back side of the GTC lists definitions of trauma and toxic stress and highlights strategies to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma transfer.

Twenty-one adolescent mothers were recruited for this study during in-person visits in the Healthy Generations clinic. Pediatricians (YS, BC) approached patients for participation in the study and then utilized a semi-structured script (developed by BC) to conduct a 5-minute conversation about generational trauma, using the GTC as an educational tool. Participants then completed a 20-question survey, consisting of demographic, Likert-scaled, and free response questions and received a $10 gift card. Healthy Generations patients were approached universally for participation, without focus on history of traumatic exposures. As part of the Healthy Generations clinic, patients/families are linked with a dedicated social worker, who was available if the GTC and corresponding discussion raised any concerns by patients, which did not occur. This study was approved by the Children’s National Hospital institutional review board.

Results

Among the 21 participants, 43% were 14–17 years and 57% were 18+ years; 91% were Black; and 5% were Hispanic. Twelve participants (57%) had not heard about generational trauma prior to this visit. As shown in , on a Likert scale of 1–5, participants rated interest in learning about generational trauma 4.2. In a corresponding free-text question, participants indicated surprise that trauma can be passed down generationally, that trauma has significant impacts on personal health, and that the cycle can be broken. Participants rated their comfort in receiving this information from their pediatrician as 4.3 and rated the clarity of how the GTC depicted strategies to reduce the effects of trauma on health as 4.7. Participants indicated being very likely to share this information with others (4.6) and to make changes in their life based on this information (4.5). For the free-text question regarding changes participants would make based on the GTC discussion, responses related to the utilization of self-care to prevent the transfer of trauma were prevalent. Examples included addressing emotions, stress, and mental health through mindfulness, a therapist or support group, and taking time to process trauma.

Table 1. Participant feedback on the generational trauma card.

Conclusions

The GTC is a unique educational tool that allows healthcare providers to discuss on the impact of trauma on health and wellness universally during patient visits, rather than prioritizing discussions based on patient or caregiver ACE score. Adolescent parents were comfortable learning about generational trauma with the aid of the GTC and indicated that it may lead to positive behavior change. By promoting awareness of generational trauma and the impact on health, the GTC can be classified as a preventative intervention, which is recognized as the most effective intervention approach to address the intergenerational transmission of trauma (Isobel et al., Citation2019).

Participant acceptance of the GTC is a critical first step in the further utilization and evaluation of this tool. Next steps will include evaluation of the effectiveness of the GTC and corresponding conversation in leading to specific health-promoting behaviors, such as engagement in mental health services, parenting classes, or self-care habits. Qualitative exploration may also examine the mediators of behavior change, such as an increase in motivation, trust, self-efficacy, or adherence (Street et al., Citation2009). The limitations of our study include its small sample size and its setting of a teen-tot clinic that participants consider their medical home, which could have made them more comfortable discussing generational trauma. Further study is needed to determine generalizability and feasibility in additional settings.

Despite our sample size and unique sub-population, our study adds to the existing literature by introducing a patient-friendly and brief educational intervention regarding trauma and health. As the development of the GTC was rooted in educational theory and research that images can assist with acceptance, comprehension and behavior change related to health communications, we expect that its contents can be modified to allow for broader education on trauma and health, beyond the sub-topic of generational trauma.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Children’s National Hospital institutional review board.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Binny Chokshi

Binny Chokshi, an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the Edward Hébert School of Medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Her educational endeavors and research initiatives focus on the impact of adverse childhood experiences on health across the lifespan. She advocates for a universal trauma-informed approach within healthcare institutions.

Catherine Pukatch

Catherine Pukatch, MD is a third year pediatric resident at Children’s National Hospital. She has an interest in community health, health inequities, and primary care.

Natasha Ramsey

Natasha Ramsey, MD, MPH is a pediatrician, currently in training to receive adolescent medicine specialization. She has dedicated her career to serving diverse populations in the areas of family planning, reproductive health, and HIV prevention.

Alexa Dzienny

Alexa Dzienny is a fourth year medical student and aspiring obstetrician-gynecologist. She is passionate about women’s health, reproductive justice, and global health inequities.

Yael Smiley

Yael Smiley, MD is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. She is the medical director of the Healthy Generations Program and the assistant program director for the Leadership in Advocacy, Under-resourced Communities and Health Equity (LAUnCH) track of the Pediatric Residency Program at Children’s National Hospital.

References

- Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

- Arlinghaus, K. R., & Johnston, C. A. (2018). Advocating for behavior change with education. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 12(2), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617745479

- Chokshi, B., Chen, D., & Beers, L. (2020). Interactive case-based childhood adversity and trauma-informed care electronic modules for pediatric primary care. MedEdPORTAL : The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, 16, 10990. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10990

- Chokshi, B., Walsh, K., Dooley, D., Falusi, O., Deyton, L., & Beers, L. (2020). Teaching trauma-informed care: A symposium for medical students. MedEdPORTAL : The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, 16, 11061. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11061

- Black, M. M., Papas, M. A., Hussey, J. M., Dubowitz, H., Kotch, J. B., & Starr, R. H. Jr. (2002). Behavior problems among preschool children born to adolescent mothers: Effects of maternal depression and perceptions of partner relationships. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 31(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_04

- Cheng, T., Lewin, A., Rahman, T., Hodgkinson, S., Beers, L., & Schmitz, K. (2022). Generations. HHS Teen Pregnancy Prevention Evidence Review on youth.gov. Retrieved January 22 from https://tppevidencereview.youth.gov/document.aspx?rid=3&sid=278&mid=1.

- Garner, A. S., Shonkoff, J. P., & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. (2012). Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics, 129, e224–e231. 10.1542/peds.2011-2662

- Hillis, S. D., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Marchbanks, P. A., & Marks, J. S. (2004). The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics, 113(2), 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.2.320

- Hodgkinson, S., Beers, L., Southammakosane, C., & Lewin, A. (2014). Addressing the mental health needs of pregnant and parenting adolescents. Pediatrics, 133(1), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0927

- Houts, P. S., Doak, C. C., Doak, L. G., & Loscalzo, M. J. (2006). The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Education and Counseling, 61(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004

- Isobel, S., Goodyear, M., Furness, T., & Foster, K. (2019). Preventing intergenerational trauma transmission: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(7–8), 1100–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14735

- Kellerman, N. P. (2001). Transmission of Holocaust trauma‐An integrative view. Psychiatry, 64(3), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.64.3.256.18464

- Loveday, S., Hall, T., Constable, L., Paton, K., Sanci, L., Goldfeld, S., & Hiscock, H. (2022). Screening for adverse childhood experiences in children: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 149(2), e2021051884. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-051884

- Street, R. L., Jr., Makoul, G., Arora, N. K., & Epstein, R. M. (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling, 74(3), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015