Abstract

At an early stage of Russia–Ukraine War, the psychological conditions of Ukraine people relocated to Russia were reported by the International Journal of Loss and Trauma. In this paper, updated findings evidence the war impact on quality of life, depression, loneliness, substance use, and eating behavior among refugees relocated from the Ukraine to the Russian Federation. Indicators of quality of life, mental health, depression, substance use, and unhealthy food intake tend to be attributed to the war regardless of refugee gender, age, religiosity, and marital status. These findings are consistent with those previously reported about the impact of war and location status among Ukrainian “help” professional women showing relocation associated with poor psycho-emotional well-being, increased burnout, loneliness, and substance use. Responses from the refugees continue to evidence key issues that need to be addressed by policy and program decision makers as well as service providers for prevention and treatment intervention purposes.

Introduction

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine provoking the most serious military conflict in Central Europe since 1945. One year later, it has been reported by official accounts that there have been more than 18,000 civilian causalities including 7031 killed and 11,327 injured (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2023). However, the OHCR has reported that actual figures are much higher resulting from exposure to indiscriminate bombing affecting wide impact areas. In addition to the death and injury that have occurred, the number of refugees fleeing Ukraine to neighboring countries has reached about 2,871,519 (UN Refugee Agency, Citation2023) and about 5,914,000 have been internally displaced within the country since Nov. 25 (International Organization for Migration, Citation2023). Overall, refugee data evidence the war has caused the world’s fastest-growing displacement crisis since World War II (UN Refugee Agency, Citation2022).

For the first time in its recent history, Ukraine is now faced with armed conflict within its boundaries, a large scale refugee crisis, and formidable challenges to address public health and social service needs (Javanbakht, Citation2022; Murphy et al., Citation2022; Oviedo et al., Citation2022). Those caught up in the conflict are at risk of post-traumatic stress disorder as well as depression, anxiety, and other conditions including substance misuse and problem eating behavior. Such conditions are expected to increase that will have “long and even inter-generational impacts” (Sheather, Citation2022). Studies from countries that have experienced violent conflict evidence considerable mental health problems among people affected by displacement and other war-induced factors (Bogic et al., Citation2015; Borho et al., Citation2020; Ghumman et al., Citation2016; Miller et al., Citation2002).

Research on refugee mental health tends to focus on assessing the psychological impact of war-related experiences, such as death or serious injury of loved ones, the destruction of people’s homes, and physical and/or sexual violence. However, some studies suggest that what happens to refugees after they leave their homeland (e.g., the stresses encountered in exile, social isolation, loneliness, decrease quality of life and financial well-being) may be stronger predictors of mental health including depression than the amount of their direct exposure to war-related events (Gleeson et al., Citation2020; Miller et al., Citation2002; Sengoelge et al., Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2021).

The Russian–Ukrainian War has generated a wide range of publications and perspectives about the conflict from comparisons of Ukrainian and Afghan refugees to media induced war trauma amid conflicts in Ukraine (De Coninck, Citation2022; Su et al., Citation2022). However, field-based information is relevant for policy and intervention purposes to address the short and long consequences of the conflict between the two countries. During the past year, the psychological conditions of Ukraine people relocated to Russia have been reported in the International Journal of Loss and Trauma, albeit in an exploratory manner (Konstantinov et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). In this paper, further examination is given to depression, loneliness, quality of life, substance use, and eating behavior among Ukrainian people from eastern Ukraine who relocated to Russia.

Methods

The Qualtrics software platform was used for this survey enabling relocated refugees to answer questions online about their living conditions and well-being. The survey was conducted in October–November 2022. The 244 refugees who volunteered to participate were recruited with the approval of regional authorities responsible for human rights in the region of Penza (Russia) located 388 miles southeast of Moscow. Refugees from Ukraine relocated to Russia have been cared for, in part, by non-government agency volunteers, the Russian Orthodox Church, the International Red Cross, and other relief organizations. With government authorization, a psychologist met the refugees, individually and in group meetings, to collect information and provide them with a link to access the Qualtrics software platform at Ben Gurion University of the Negev—Regional Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research (RADAR) Center. Established in 1996, the RADAR Center has received US National Institute on Drug Abuse recognition for its collaborative efforts. The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly; therefore, due to the sensitive nature of the research, the data collected are not available for shared purposes. No external grant funding was received for this study. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 25. The Pearson’s chi-squared test for qualitative/nonparametric variables, t-test, and one-way ANOVA were used. Stepwise regression analysis was used to identify the key quality of life predictors among refugees.

Standardized data collection instruments were used—mainly, the World Health Organization—Quality of Life Scale (WHOQOL) (WHO, Citation2022), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001), the Fear of War Scale (FWS) (Kurapov et al., Citation2023), the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) (Smith et al., Citation2008), Short Burnout Measure (SBM) (Malach-Pines, Citation2005), and the De Jong Gierveld 6-Item Loneliness Scale (Gierveld & Tilburg, Citation2006).

The World Health Organization—Quality of Life Scale (WHOQOL) (WHO, Citation2022) contains 26 questions aimed at assessing the respondent’s quality of life over the past two weeks in four areas: physical health, psychological, social relationship, and environment. The respondent response to each statement was assessed on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (completely unsatisfied) to 5 (completely satisfied).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001) is designed to assess the severity of depression and has proven to be a reliable diagnostic tool. The questionnaire consists of 9 questions, such as “Have you experienced indifference and depression during the last two weeks? with four possible choices ranging from “on separate days” to “almost every day.”

The Fear of War Scale (FWS) (Kurapov et al., Citation2023) was designed for self-assessment of fears associated with the war in Ukraine. Respondents are asked to assess 10 statements, for example, “I am afraid of losing my life due to the war” on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Higher scores correspond to a greater fear of war.

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) (Smith et al., Citation2008), was created to assess the perceived ability to recover from stress defined as resilience. The scale contains six statements, such as “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times”; and respondents need to determine their attitude to each statement on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The Short Burnout Measure (SBM) (Malach-Pines, Citation2005) is a widely used self-report measure of burnout that includes symptoms of fatigue and physical exhaustion, depression, mental fatigue, sleeping problems, etc. The 10-item version was used with 5-point Likert scale responses from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

Тhe De Jong Gierveld 6-Item Loneliness Scale (Gierveld & Tilburg, Citation2006) is based on a cognitive approach to understand the sense of loneliness and its causes. The level of loneliness is assessed by the combined expression of two parameters: emotional and social loneliness. The scale includes six questions, such as “There are many people I can fully trust,” and uses three response options: Yes, More or Less, No.

These instruments were found reliable with Cronbach’s alpha scores of WHOQOL = 0.907; PHQ-9 = 0.870; FWS = 0.867; BRS = 0.712; SBM = 0.914; and Loneliness Scale = 0.688. In addition to their survey instrument responses, respondents provided details about their gender, age, marital status, the impact of war on their lives, substance (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, pain reliever, and sedative) use, eating behavior, and psycho-emotional well-being.

Results

Survey respondent background characteristics evidence: 63.4% female and 36.6% male; mean and median ages of 40.9 (SD—11.5) and 39.0, respectively; 67.9% married/partnered; 61.5% religious; and 60.5% with family members still in Ukraine including parents (26.6%) and children (11.2%). Additional information from the refugees shows that 61.5% were from a war zone at the time of relocation to Russia—mostly the ice-free port city area of Mariupol on the north coast of the Sea of Azov that leads to the Black Sea. Among the respondents, 52.5% lost property and housing; 29.1% have health deterioration; 17.6% lost relatives because of the war; and the majority (73.4%) expressed a desire to stay in Russia compared to 25.3% who preferred to return to Ukraine and 1.3% wanting to relocate elsewhere. Also, 46.7% of the respondents reported they have family members and relatives who relocated to countries, such as Germany and Poland. For data analysis purposes, refugee respondents were divided into three age groups: 18–35 years (n = 82), 36–44 years (n = 83), and 45–75 years (n = 79). provides the background characteristics of the survey respondents.

Table 1. Background characteristics of the survey respondents.

WHOQOL-BREF four domain response scores addressing physical health, psychological, social relationship, and environment were transformed to a scale from 0 to 100. Overall, the mean domain scores indicated poor to fair living conditions (Hawthorne et al., Citation2006) among the relocated refugees. Additional analyses evidence males, more than females, with significantly more positive psychological scores; and those married/partnered with better social relationship(s) (p = .035). Refugees from the heavily bombarded Mariupol city area reported significantly lower QOL environment domain scores (p = .008); and younger respondents were likely to report better physical health (p = .015) and social relationship scores (p = .009). Refugees with poor health evidence significantly lower quality of life conditions across all WHO-QOL domains as well as lower resilience (p = .001) and higher levels of fear of war (p = .002) and burnout (p < .001). provides information about the quality of life (QOL) four domains and average scores by gender and respondent health status.

Table 2. QOL domain scores by gender and health status.

Stepwise regression analysis shows the following factors associated with each WHO-QOL domain: physical health—age, marital/partner status, resilience, burnout, and emotional loneliness (adjusted R2 = .568); psychological—depression, resilience, burnout, and overall loneliness (adjusted R2 = .587); social relationship—age, burnout, and overall loneliness (adjusted R2 = .288); and environment—age, marital status, and burnout (adjusted R2 = .202). Additional independent variables including gender, fear of war, and substance use did not significantly increase the proportion of explained variance.

Responses to the Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) used to measure depression, were divided into three levels: never or minimum (n = 60), mild (n = 92), and moderate/severe (n = 52). Forty (40) respondents did not complete the questionnaire. Analysis (i.e., one-way ANOVA) showed fear of war, burnout, low resilience, and low quality-of-life significantly associated with depression (), and not to gender, age, marital and religiosity statuses.

Table 3. Fear of war, burnout, resilience, and quality-of-life by level of depression.

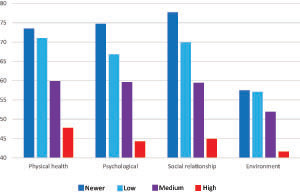

Loneliness was found significantly associated with the fear of war, burnout, poor quality of life, low resilience, and depression (p < .001 for all cases). shows the quality of life scores by levels of loneliness. Respondent background characteristics of age, marital and religiosity were not found associated with loneliness.

Last month substance (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, pain reliever, and sedative) use was reported by 73.3% of the respondents. Males, more than females, use tobacco (72.5 vs. 50.3%; p = .005), alcohol (64.7 vs. 34.0%; p < .001), and binge drink (33.3 vs. 5.1%; p < 001). Females reported significantly more pain relievers (18.5 vs. 5.9%; p = .030) and sedative use (13.5 vs. 2.0%; p = .021). Refugees using pain relievers reported lower levels of health (p < .001), less resilience (p < .001), and more fear of war (p = .004), burnout (p = .013), and depression (p = .031); also, those using sedatives reported lower levels of health (p < .001), more fear of war (p = .002) and burnout (p = .002), and less resilience (p < .001). Binge drinking was found associated with less fear of war (p = .004) and high resilience (p = .002) among the refugee respondents. Also, refugees using pain relievers and sedatives reported lower average quality of life scores (p = .004 and p = .046, respectively).

Among the refugees, 39.4% reported an increase in eating salted and/or sugared foods due to the war; and 36.2% said their weight increased. Respondents who reported eating more unhealthy food had significantly lower levels of health (p < .001), quality of life (p = .007), and resilience (p = .045) as well as more fear of war (p < .001) and burnout (p < .001). Unhealthy food intake and weight gain were found significantly associated with depression (p < .001).

Discussion

This study provides a unique insight into the impact of war on the quality of life and mental health/well-being of Ukrainian refugees relocated to Russia. Indicators of quality of life, mental health, depression, substance use, and unhealthy food intake tend to be attributed to the war regardless of gender, age, religiosity, and marital status. These findings are consistent with those found elsewhere (Armour et al., Citation2011; Blackmore et al., Citation2020; Duagani Masika et al., Citation2019; Hales et al., Citation2018; Javanbakht, Citation2022; Jieqiong et al., Citation2022; Mels et al., Citation2009; Mesa-Vieira et al., Citation2022) and among Ukrainian “help” profession women (Pavlenko et al., Citation2023) during the war showing that country relocation is associated with poor psycho-emotional well-being, increased burnout, loneliness, and substance use.

These present study results are preliminary, based on a limited study cohort with data collected at one point in time during the war and at one location (i.e., Penza, Russia). Additional research is needed, using uniform data collection methods where refugees have relocated, to better understand the short-and long-term impact of the war and factors associated with their health, quality of life, and behavior. In conclusion, this study provides usable information for policy and services intervention purposes among government and non-government organizations, in cooperation and coordination with health, mental health, and social service professionals charged with the task of mitigating the loss and trauma experienced by people affected by the Russian–Ukrainian War.

Acknowledgments

The co-authors of this paper acknowledge the support and cooperation of the Ukrainian refugees who participated in the survey. Gratitude is expressed to Drs. Toby and Mort Mower (Z’L) for their generous support of the Ben Gurion University of the Negev—Regional Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research (RADAR) Center.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [RI]. The data are not publicly available due to [restrictions e.g., their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants].

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vsevolod Konstantinov

Vsevolod Konstantinov is a professor and head of the Department of General Psychology, Penza State University (Penza, Russia). He is the author of six books and over 100 scientific publications. His scientific interests are problems of migrant and immigrant adaptation to new living conditions, socio-psychological aspects of personality maladjustment, and problems of addictive behavior among related issues.

Alexander Reznik

Alexander Reznik, Senior Research Associate of the Regional Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research (RADAR) Center, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, is the author of six books and more than 100 scientific publications on substance abuse among high-risk populations, including immigrants and school dropouts as well as the issue of acculturation.

Richard Isralowitz

Richard Isralowitz, Director of the Regional Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research (RADAR) Center and Professor (Emeritus), Ben Gurion University of the Negev (BGU received recognition and an award from the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) for his “Contributions to Scientific Diplomacy through Outstanding Efforts in International Collaborative Research,” and has served as a NIDA Distinguished International Scientist as well as a Fulbright Scholar. Dr. Isralowitz is the author of 12 books and over 150 publications.

References

- Armour, C., Elhai, J. D., Layne, C. M., Shevlin, M., Duraković-Belko, E., Djapo, N., & Pynoos, R. S. (2011). Gender differences in the factor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in war-exposed adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(4), 604–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.01.010

- Blackmore, R., Boyle, J. A., Fazel, M., Ranasinha, S., Gray, K. M., Fitzgerald, G., Misso, M., & Gibson-Helm, M. (2020). The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 17(9), e1003337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003337

- Bogic, M., Njoku, A., & Priebe, S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

- Borho, A., Viazminsky, A., Morawa, E., Schmitt, G. M., Georgiadou, E., & Erim, Y. (2020). The prevalence and risk factors for mental distress among Syrian refugees in Germany: A register-based follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02746-2

- De Coninck, D. (2022). The refugee paradox during wartime in Europe: How Ukrainian and Afghan refugees are (not) alike. International Migration Review, 019791832211168. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183221116874

- Duagani Masika, Y., Leys, C., Matonda-Ma-Nzuzi, T., Blanchette, I., Mampunza Ma Miezi, S., & Kornreich, C. (2019). Peritraumatic dissociation and post-traumatic stress disorder in individuals exposed to armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(5), 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1597814

- Ghumman, U., McCord, C. E., & Chang, J. E. (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder in Syrian refugees: A review. Canadian Psychology, 57(4), 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000069

- Gierveld, J. D. J., & Tilburg, T. V. (2006). A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: Confirmatory tests on survey data. Research on Aging, 28(5), 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027506289723

- Gleeson, C., Frost, R., Sherwood, L., Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Halpin, R., Murphy, J., & Silove, D. (2020). Post-migration factors and mental health outcomes in asylum-seeking and refugee populations: a systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1793567. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1793567

- Hales, C. M., Fryar, C. D., Carroll, M. D., Freedman, D. S., Aoki, Y., & Ogden, C. L. (2018). Differences in obesity prevalence by demographic characteristics and urbanization level among adults in the United States, 2013–2016. JAMA, 319(23), 2419–2429. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.7270

- Hawthorne, G., Herrman, H., & Murphy, B. (2006). Interpreting the WHOQOL-BREF: Preliminary population norms and effect sizes. Social Indicators Research, 77(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5552-1

- International Organization for Migration. (2023). Ukraine—Internal Displacement Report—General Population Survey Round 11 (25 November–5 December 2022). Retrieved from https://dtm.iom.int/reports/ukraine-internal-displacement-report-general-population-survey-round-11-25-november-5

- Javanbakht, A. (2022). Addressing war trauma in Ukrainian refugees before it is too late. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2104009. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2104009

- Jieqiong, H., Yunxin, J., Ni, D., Chen, L., & Ying, C. (2022). The correlation of body mass index with clinical factors in patients with first-episode depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 938152. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.938152

- Konstantinov, V., Reznik, A., & Isralowitz, R. (2022a). The impact of the Russian–Ukrainian war and relocation on civilian refugees. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2022.2093472

- Konstantinov, V., Reznik, A., & Isralowitz, R. (2022b). Update: Civilian refugees of the Russian–Ukrainian war. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2022.2135288

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ‐9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Kurapov, A., Pavlenko, V., Drozdov, A., Bezliudna, V., Reznik, A., & Isralowitz, R. (2023). Toward an understanding of the Russian–Ukrainian war impact on university students and personnel. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 28(2), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2022.2084838

- Malach-Pines, A. (2005). The burnout measure, short version. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.12.1.78

- Mels, C., Derluyn, I., Broekaert, E., & Rosseel, Y. (2009). Screening for traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescents in the war-affected eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(6), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.56

- Mesa-Vieira, C., Haas, A. D., Buitrago-Garcia, D., Roa-Diaz, Z. M., Minder, B., Gamba, M., Salvador, D., Gomez, D., Lewis, M., Gonzalez-Jaramillo, W. C., Pahud de Mortanges, A., Buttia, C., Muka, T., Trujillo, N., & Franco, O. H. (2022). Mental health of migrants with pre-migration exposure to armed conflict: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 7(5), e469–e481. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00061-5

- Miller, K. E., Weine, S. M., Ramic, A., Brkic, N., Bjedic, Z. D., Smajkic, A., Boskailo, E., & Worthington, G. (2002). The relative contribution of war experiences and exile‐related stressors to levels of psychological distress among Bosnian refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(5), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020181124118

- Murphy, A., Fuhr, D., Roberts, B., Jarvis, C. I., Tarasenko, A., & McKee, M. (2022). The health needs of refugees from Ukraine. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 377, o864. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o864

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2023). Ukraine: Civilian casualty update 16 January 2023. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2023/01/ukraine-civilian-casualty-update-16-january-2023

- Oviedo, L., Seryczyńska, B., Torralba, J., Roszak, P., Del Angel, J., Vyshynska, O., Muzychuk, I., & Churpita, S. (2022). Coping and resilience strategies among Ukraine War refugees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013094

- Pavlenko, V., Kurapov, A., Drozdov, A., Korchakova, N., Reznik, A., & Isralowitz, R. (2023). Ukrainian “help” profession women: War and location status impact on well-being. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 28(1), 92–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2022.2105482

- Sengoelge, M., Nissen, A., & Solberg, Ø. (2022). Post-migration stressors and health-related quality of life in refugees from Syria resettled in Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052509

- Sheather, J. (2022). As Russian troops cross into Ukraine, we need to remind ourselves of the impact of war on health. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 376, o499. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o499

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

- Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Cheshmehzangi, A., Ahmad, J., Šegalo, S., da Veiga, C. P., & Xiang, Y. T. (2022). Public health crises and Ukrainian refugees. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 103, 243–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2022.05.004

- UN Refugee Agency. (2022). Ukraine situation regional refugee response plan. Retrieved from https://reporting.unhcr.org/document/2219

- UN Refugee Agency. (2023). Ukraine Refugee Situation. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine

- WHO. (2022). WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref

- Wu, S., Renzaho, A. M., Hall, B. J., Shi, L., Ling, L., & Chen, W. (2021). Time-varying associations of pre-migration and post-migration stressors in refugees’ mental health during resettlement: A longitudinal study in Australia. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 8(1), 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30422-3