Abstract

Grief is a core human experience. The time following the loss of a loved one is associated with an increased risk for negative health outcomes. Yet, only a few studies investigate bodily consequences of grief and consoling behaviors, specifically the potentially supportive role of interpersonal touch during grief. We conducted an online-study where participants filled in questionnaires and rated videos of short touch gestures and interactions. People who lost a loved one within the last 2 years were asked about their grief experiences and to rate the different types of touch from the perspective of a receiver. People who had not lost a close person in the last 2 years rated the touch from the perspective of providing touch to a grieving individual. The majority of the recent-loss sample reported to have perceived their own body and bodily states less after the loss. Two-thirds reported feeling the presence of the deceased at least once. Grief-sensations were experienced mostly in the chest and upper body, the same areas where the consoling effect of a hug was perceived. Overall, the recent-loss group reported amounts of wanting of the vicarious touch gestures similar to the endorsement by people taking the active touching perspective. However, discrepancies between groups were found for some types of touch, including slow affective stroking. These results contribute to a deeper understanding of the body and bodily interactions like social touch in grief and consolation. Our findings can be seen as a first point of reference on how to interact with grieving individuals and could contribute to novel interventions for individuals with prolonged grief disorder.

Introduction

Almost every human will grieve the loss of a loved one during their lifetime. While most people eventually adapt to the loss, about ten percent develop complicated grief, a psychopathological condition (Bryant, Citation2012). Grief is a complex interaction of bodily, affective, and social processes, yet bodily aspects of grief have mostly been overlooked (Brinkmann, Citation2019). With increasing life expectancies, societal norms of dealing with death and grief have changed. At least in industrialized societies, grieving is supposed to be private and brief (Osterweis et al., Citation1984). In consequence, those wishing to express condolences and console the griever are left with little guidance from societal norms and traditional rituals (Burrell & Selman, Citation2022; Jedan et al., Citation2018).

One potentially impactful way to console others is interpersonal touch. Through touch, humans can communicate a wide range of emotions including sympathy and sadness (McIntyre et al., Citation2022). It has been suggested that primates developed verbal language from non-verbal pre-cursors to facilitate communication to larger groups (Dunbar, Citation1998), as non-verbal communicative behaviors like touch or facial expression are not efficient for maintaining all social bonds (Dunbar, Citation1993). The retention of inter-individual touch behaviors in humans suggests a more niche role, potentially that of intimacy. As it is not possible to use touch to communicate with multiple people simultaneously, touch may signal particular attention to one individual, enforcing social connectedness (Jablonski, Citation2021). Indeed, social touch has been shown to be the preferred non-verbal communication channel for expressing love and sympathy (App et al., Citation2011).

So far, research on functions of social touch mostly focused on intimate relationships (Cascio et al., Citation2019; Kreuder et al., Citation2017), or on pain modulation (Che et al., Citation2021; Goldstein et al., Citation2018; Savallampi et al., Citation2023). The expression of sympathy is common in grief, however research on consoling touch is limited. A previous study using a qualitative approach identified physical isolation as one problematic experience for grieving individuals during the covid-19 pandemic (Scheinfeld et al., Citation2021), suggesting that touch might be especially important during grief. Two studies found a positive effect of touch therapy on subscales of the grief experience inventory (despair, depersonalization, and somatization) (Kempson, Citation2001; Robinson, Citation1995). However, both studies used professional touch as an intervention.

The field of social touch research calls for more elaborate investigations away from basic touch mechanics toward to more context-oriented and ecologically valid investigations (Schirmer et al., Citation2022). Coming from this background, we were surprised to find that the role of nonprofessional touch during grief remains to be investigated. Therefore, we performed an online study to investigate which types of touch grieving individuals would endorse. We hypothesized that there might be a mismatch between attitudes toward social touch in people currently grieving and people taking the perspective of potential consolers (Hypothesis 1). Specifically, we expected that people who are currently grieving would want to receive affective touch like hugs and slow stroking or holding and would rate such affective touch as highly consoling given the known stress-buffering effects of social touch (Ditzen et al., Citation2007; von Mohr et al., Citation2017; Walker et al., Citation2017). Given the western norm of grief as a private individual experience (Osterweis et al., Citation1984), we believe consolers (i.e., that people who had not experienced a recent loss and are asked to take the perspective of consoling a griever though touch) would underestimate the role of touch, therefore endorsing these affective touch types less and rating them as less consoling.

Through touch, especially interpersonal touch, humans learn about their own body and its boundaries (McGlone et al., Citation2014). Perception of one’s body and distinction between this bodily self and the non-self, the surrounding world, is crucial for making sense of the world and for interaction with others (Boehme & Olausson, Citation2022; Fotopoulou & Tsakiris, Citation2017). Through tactile interactions, a grieving individual might be able to experience grounding and support on a more visceral level than through verbal support statements or other forms of nonverbal communication. However, in order to investigate this, the fields needs to first develop a deeper understanding of the phenomenology of bodily experiences in times of grief, similar to what has been done in psychiatric conditions, especially regarding body perception in schizophrenia (Northoff & Stanghellini, Citation2016). Only few articles focus in the bodily phenomenology of grief (Brinkmann, Citation2019; DuBose, Citation1997; Fuchs, Citation2018; Pearce & Komaromy, Citation2022). One qualitative interview-based study reported feelings of depersonalization and derealization in bereaved individuals (Gudmundsdottir, Citation2009). It has been suggested, again based on phenomenological interviews, that bodily memories might play a crucial role in grief, especially regarding oscillations of grief (Hentz, Citation2002) and regarding coping and resilience strategies along the lines of the continuing bonds framework (Simpkins & Myers-Coffman, Citation2017). We therefore wanted to explore bodily phenomenology during times of grief. We hypothesized that grief elicits bodily sensations (Hypothesis 2). Specifically, we expected grieving individuals to (a) perceive both feelings of grief and the effect of consoling gestures as bodily sensations, and (b) that the locations of these sensations would overlap. This hypothesis was based on previous work that documented the bodily locations of different emotions, including grief, suggesting an overlap of sensations of sadness, social longing, love, and togetherness in the chest/stomach areas (Nummenmaa et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, we hypothesized altered bodily perception in times of grief (Hypothesis 3). Specifically, we expected that (a) grieving participants perceive their body and sensations from within their body (i.e., interoception) less clearly, and that they might experience a feeling of presence of the deceased. We also expected that (b) the extend of these altered bodily perceptions might relate to the intensity of grief.

Methods

We collected data using an English language online survey available between June 2022 and January 2023. The study was advertised through different social media platforms. Participation was completely anonymous, and no personal identifiers were collected. The survey was hosted on Redcap (P. A. Harris et al., Citation2009, Citation2019). The study was positively reviewed by the national Swedish ethics board (2022-02614-01).

Participants

The online survey was accessed 399 times. A total of 116 people gave their consent to participate. Out of these, 95 finished filling out all forms. Participants were informed that they could end their participation at any time without giving any further explanation. They were informed that no personal information was collected that could be traced back to them as individuals. No reward or reimbursement was provided for participation.

A total of 116 people participated (). Depending on the experience of a recent loss, participants were assigned to Sample 1 (loss < 2 years ago) or Sample 2 (loss > 2 years ago or no loss). A majority of participants in Sample 2 had experienced loss of a close person before (71.6%), on average this had occurred 10.2 years ago (±6 years). There were no significant differences in the group demographics (). The most common country of residence was Germany (n = 41) followed by the US (n = 23), and Sweden (n = 21). Twenty-seven participants resided in the rest of Europe, and four outside Europe. In Sample 1, there were 6 non-completed responses (dropout rate 14.0%; 2 males, 4 females; mean age 33.8 ± 13.5 years). In Sample 2, there were 13 incomplete responses (dropout rate 20.5%; 5 males, 7 females, 1 other; mean age 42.4 ± 15.5 years). All demographic information was self-reported, either as a free-text response (age), selection from a list (gender), check-box allowing multiple boxes to be ticked (health situation) or check-box only allowing a single box tick.

Table 1. Demographics.

Table 2. Overview of touch videos viewed by participants.

Overview of procedure

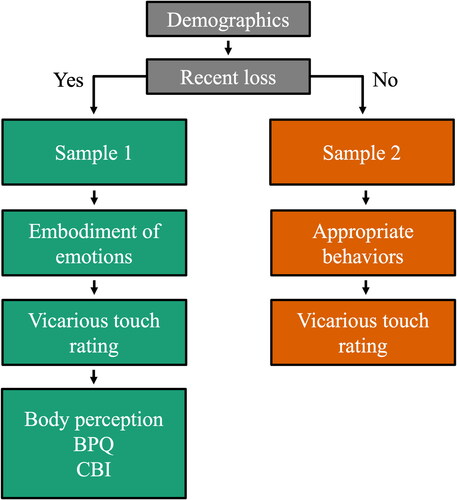

After initial demographic questions (age, gender, education, occupation, living situation, relationship status, general health status), participants were allocated into sample 1 or Sample 2 (). The study procedures differed for the two samples. Details on all measures are given below.

Figure 1. Data collection procedure. Note: Depending on recent loss (within the last 2 years) of a close person, participants were placed in Sample 1 or 2. BPQ = bereavement phenomenology questionnaire, CBI = core bereavement items.

Sample 1 participants filled out the embodiment of emotions. This was followed by the evaluation of the vicarious touch videos taking the perspective of the receiver of touch. After the video rating, four questions about body perception were asked. In the end, Sample 1 filled in the core bereavement inventory (CBI) (Burnett et al., Citation1997) and the bereavement phenomenology questionnaire (BPQ) (Kissane et al., Citation1997). The CBI and BPQ were collected as a comparator of grief intensity in our grieving sample to previous studies.

Participants in Sample 2 were first asked about hypothetical behaviors toward a grieving person. This was included to match reflections on grief and consolation in Sample 1, who filled in the embodiment questions before moving on to the touch video rating. The hypothetical behaviors are not evaluated here, as they did not directly relate to any specific hypothesis. Afterwards, Sample 2 participants rated the vicarious touch videos taking the perspective of potential consoler.

Description of forms

Embodiment of emotions

This form was only filled in by subjects in Sample 1. Subjects viewed a schematic body and were asked to indicate where in their body they felt grief and where they felt the consoling effects of a hug and of non-tactile consoling efforts (talking about the deceased, condolence rituals like cards or flowers) (Suvilehto et al., Citation2015). Participants had to select from a list of body regions (with a reference body showing the regions). The areas were broadly based on those charachterized in earlier studies (Nummenmaa et al., Citation2018) and purposefully kept generic, but some smaller areas were also provided due to their association with bodily sensations in the English language, such as the neck and abdomen (as illustrated by the idiom “having the heart in the throat” and phrase “gut feeling”).

Appropriate behaviors after loss

Participants in Sample 2 were asked about their hypothetical behavior toward a grieving person. They were asked to tick boxes of which behaviors they deemed appropriate toward a grieving person (for different relationship categories: close family member, distant family member, close friend, acquaintance, work colleague): offer condolences, hand shake, offer a hug, holding hands, pat on the shoulder, stroking arms/shoulder/back, send/gift flowers, send a card/letter, ask questions about the deceased, ask questions regarding the wellbeing of the grieving individual, discuss other topics to offer distraction, offer other activities that can distract from grief. These answers were not evaluated here as they were outside the scope of the research questions, however the data is available in the supplementary materials, see Table S1.

Vicarious touch evaluation

Participants in both samples viewed short videos of different types of social touch. Two different sets of videos were included. These were evaluated separately as they originated from different sources and differed in several aspects: Set A showed touch interactions that involved the full body and complex tactile stimulations, while Set B showed very specific, less complex types of touch by a hand touching a forearm. An overview of all videos used in the study is shown in .

Set A videos are in black and white, and show two actors (one man, one woman) from the side and from the neck to just below the hips performing short sequences (2 s) of social touch interactions. For example, one person walks toward the other and gives them a hug. This complex interaction involves approach, pressure touch, and rubbing of the arms and shoulders. Set B videos were in color and display a forearm resting on a surface, which is being touched by someone else’s hand. These videos last 10–13 s and involve simpler touch interactions, for example the hand performing a slow stroking movement.

Set A videos were designed and evaluated before as part of the social touch data base (Lee Masson & Op de Beeck, Citation2018). The included video sequences were all previously evaluated to display a positive affect. Only the action categories “hug” (Database video 2, hug-1; database video 14, hug-2; database video 16, hug-3), “stroke” (database video 4, stroke-1; database video 18, stroke-2), and “hold” (database video 19, hold-1) were included (https://osf.io/8j74m/). Set B videos were standardized touch expressions previously designed by our group to communicate different emotions (attention; love, happiness, sadness, calming, gratitude) (McIntyre et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). These videos are referred to as the emotion assigned in the original study.

Simultaneously with each video, two questions were displayed. Participants were able to re-watch the video by pressing “play” again if they wished to. Participants in Sample 1 were asked whether they would like to be touched this way (answer options: yes/no) and how consoling they would experience this type of touch (0–100 visual-analog-rating scale, endpoints “not consoling at all” and “very consoling”). Participants in Sample 2 were asked whether they would touch a currently grieving person this way (answer options: yes/no) and how consoling they believe this type of touch to be (visual-analog-rating scale, endpoints “not consoling at all” and “very consoling”). All videos used in the study are available (https://osf.io/nxprt/).

Body perception after loss

This form was only filled in by Sample 1 and contained four questions regarding body perception during the first 6 months after the loss: “During the first 6 months after your loss… did you experience a diminished feeling of your own body?” (Answer options: yes/no). “…did you experience problems identifying your bodily sensations (hunger, thirst, tiredness, etc.)?” (Answer options: yes/no). “…do/did you feel more present or less present in your body?” (Answer options: less/more/no difference). “…did you have an experience of felt presence of the person you lost?” (Answer options: No/Yes, once/Yes, multiple times).

CBI and BPQ

At the end, Sample 1 filled in the CBI and the BPQ. The CBI assesses prevalence of thoughts, memories, etc. relating to the deceased person. A typical item from the CBI is “Do you think about ‘x’?” or “Do you find yourself preoccupied with images or memories of ‘x’?” wherein ‘x’ refers to the deceased person. The BPQ assesses how often responders experience phenomena such as feeling sad, anxious, or having intrusive thoughts of the deceased. A typical item from the BPQ is: During the past 2 weeks, how common was it for you to experience the following: “Cried about the deceased” or “Acted as though the deceased were still alive”.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Excel version 16.74 (Microsoft) and JASP version 0.16.4 (Team, Citation2022). Minimally curated data are available (https://osf.io/nxprt/). Demographic data was compared between groups using appropriate tests (t-test, chi-squared test). Given the different origin, style, and focus of the two types of videos (complex full body interaction/specific touch expression by a hand on the forearm), the answers for the two sets of videos were analyzed independently. Endorsement of touch displayed in videos was compared between samples using chi-squared test. Consolation ratings were non-normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk <.001 for both categories of touch videos), and therefore compared using Mann–Whitney U test. Bonferroni–Holm-correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons. Bodily sensations of grief and consoling acts were analyzed using a general linear mixed model with a binomial distribution (sensation present/not present) across body parts and the different aspects relating to grief. Body perception after loss was correlated with the questionnaires (BPQ and CBI) using Spearman’s rank correlation.

Results

Questionnaires

The mean score for the CBI was 28.1 ± 10.8, which is comparable to previous studies where scores were 18–31 depending on relationship to the deceased as well as time since loss (Burnett, Citation1997). The mean of the BPQ (47.9 ± 15.0) was also in line with previous research, reporting mean values of approximately 50, depending on time since loss and relationship to the deceased (Kissane et al., Citation1997). Together, these indicate our sample to be in line with other studies investigating recent loss and grief.

Endorsement and consolation effects of social touch

Participants in Sample 1 (recent-loss) were asked if they would like to be touched in a certain way and how consoling they would experience this type of touch (0–100 scale). 38 participants finished this form. People in Sample 2 (no recent loss) viewed the same videos and were asked if they would touch a currently grieving person this way and as how consoling they believe such a type of touch would be perceived. 58 people finished this form.

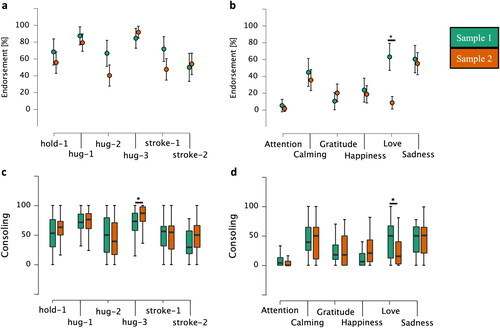

Endorsement rates and the consoling effects are shown in . There was no significant effect of sample for the endorsement rates of Set A videos, χ2(5, 395) = 4.195, p = 0.522, phi = 0.161, . Endorsement rates of Set B videos differed significantly between samples χ2(5, 161) = 18.826, p = 0.002, phi = 0.342. Post-hoc testing revealed this difference to be driven by “Love”, χ2 (1, 96) = 32.4, p < 0.001 phi = 0.449. All comparisons are available in Table S4 This touch was endorsed to a higher degree by the recent-loss sample (63.2%) than by the potential consolers (8.6%), .

Figure 2. Endorsement and consoling ratings for both video sets and samples. Sample 1 participants experienced a loss within the last 2 years and rated videos taking the perspective of receiving the touch. Sample 2 participants did not experience loss in the last 2 years and rated the videos taking the perspective of providing touch to a grieving person. Participants were asked whether they wanted this type of touch (Sample 1) or would provide this type of touch (Sample 2) (panels a and b), and as how consoling they rated this type of touch (0 = not consoling, 100 = very consoling; panels c and d). Descriptions of the videos can be found in . *indicates significant difference between samples after Bonferroni–Holm correction.

Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni–Holm correction of Set A showed that the consoling effect of “hug-3” was rated significantly different between the samples (U = 808, p = 0.007, rpb = −0.321), i.e., people taking the consoler-perspective rated it as more consoling (Sample 1 median = 73; Sample 2 median = 87). All Set A consoling ratings are displayed in and in Table S5.

In Set B, consoling ratings for “Love” differed significantly between samples (U = 1489.5, p = 0.004, rpb = 0.352), which people who recently experienced loss rated as more consoling (Sample 1 median = 50; Sample 2 median = 15.5). All Set B consoling ratings are displayed in and Table S5. No other ratings differed significantly after correction for multiple comparisons.

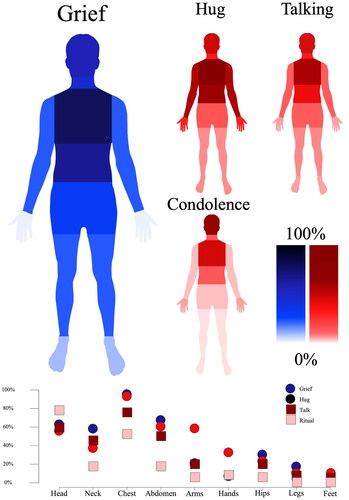

Embodiment of grief and consolation

40 people in the recent loss sample finished the embodiment form. They reported that they experienced grief-sensations mostly in the chest (90.7%, ), followed by the stomach (62.8%), head (58.1%), and neck/throat (53.5%).

Figure 3. Bodily localization of the grief experience and consoling effect of different consoling acts. In addition to the sensation of grief, the acts included hug, talking about the deceased, and a condolence wish in form of a card or flowers. The color gradients indicate endorsement rate.

The consoling effect of a hug was reportedly felt most in the chest (88.4%, ) and the stomach (55.8%), followed by arms/shoulders (53.5%), and the head (51.2%). Consolation through talking about the grief and the deceased was felt most in the chest (72.1%) and the head (55.8%), followed by stomach (46.5%) and neck/throat (41.9%). Consolation from condolence rituals (verbal condolence wishes, cards, flowers, etc.) was felt most in the head (74.4%), followed by the chest (48.8%). These are illustrated in .

A generalized linear mixed model with binomial distribution revealed a main effect of the type of emotion/behavior, χ2 (3) = 35.44, p < 0.001. The model also revealed a main effect of body part, χ2 (8) = 94.96, p < 0.001, and a main interaction effect, χ2 (24) = 116.93, p < 0.001. Notable differences are arms and hands, where consoling effect of a hug was felt more than grief (and the other consoling gestures). Condolence rituals, such as sending cards or flowers were felt more in the head than grief. Due to the amount of potential comparisons, no follow up post-hoc test was conducted (Garofalo et al., Citation2022). Individual body part endorsement rates are presented in table S2.

Body perception after loss

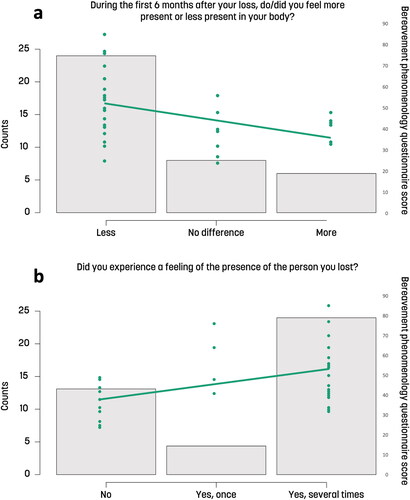

38 people in the recent loss sample finished this form. Body perception was altered for most participants in the first 6 months after the loss: A majority (63.2%) reported that they had diminished feelings of their own body and experienced reduced interoceptive abilities (i.e., less perception of hunger, thirst, etc.). A majority of participants reported feeling less present in their body (57.9%), 31.2% reported no difference, and a few (10.5%) reported feeling more present in their body following loss. A majority (68.42%) also reported to have experienced a presence of the deceased at least once, many experienced this several times (58%).

The two grief questionnaires (BPQ and CBI) were significantly correlated (ρ = 0.84, p < 0.001). Grief intensity as quantified by the BPQ correlated negatively with presence in the own body (ρ = −0.502, p = 0.002), indicating that higher grief intensity was related to reduced self-reported interoception, . It also correlated with the question about presence of the deceased (ρ = 0.460, p = 0.004), i.e., those with more intense grief felt the presence of their lost one more often, . The correlation between “having a diminished feeling of the own body” and BPQ (ρ = 0.321, p = 0.053) had the same directionality but was not significant, and the correlation between “with problems in identifying bodily sensations (ρ = 0.358, p = 0.029) also follow the same trend but did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni–Holms). The correlations between the CBI and body perception questions all had the same directionality but were either trend level non-signiciant or did not survive multiple comparison correction.

Figure 4. Correlations of current grief (BPQ) and body perception after loss. (A) The distribution of answers to the question of bodily presence following loss (Less/No difference/More), overlayed with individual BPQ scores (green). More intense grief correlated with feeling less present in the body. (B) The distribution of answers to the question about presence of the deceased (No/Yes, once /Yes, several times) overlayed with individual BPQ scores (green). More intense grief correlated with experiences of presence of the deceased.

Discussion

In this study, we show that interpersonal touch is largely endorsed and perceived as consoling by grievers. Grievers and potential consolers both rated touch similarly in terms of endorsement rates and consoling effects, although a few mismatches were observed: Slow stroking was perceived as more consoling by the grieving group, while a slow hug that included a pat on the back was seen as more consoling by people taking the perspective of consolers. Furthermore, we here found that while grief and the effect of consoling actions elicit bodily experiences, grief is accompanied with reduced perception of the own body.

Perception of social touch during grief

We hypothesized a mismatch between what kind of touch grieving individuals wished for and what kind of touch people would offer them. The results indicate large resemblance between the samples in touch preferences. This might be explained by a limiting factor of sample allocation in this study (see more detailed discussion also below): participants did not receive any reimbursement for their participation, which might have led to the effect that specifically people interested in the topics of touch and/or grief took part. Therefore, people in the consoling sample might have also been experiencing grief (which was unfortunately not quantified in our survey), which could reduce generalizability of this result. In addition, it is important to note that self-reported potential behaviors in an imagined situation might not match how the same individual would interact with a grieving person in a real life situation. Future research using more ecologically valid methods, e.g., ecological momentary assessments on touch frequency, might elucidate this point further.

Some mismatches existed between the two sample’s ratings, particularly for light stroking of the arm with the fingers. This touch was perceived as consoling and endorsed by grieving individuals, but neither endorsed nor rated as consoling by the control group. This touch expression was originally developed based on an aggregate analysis of touch strategies that people naturally used when asked to communicate a message of love (23). In the grief-related contextual framing of our current study, we did not ask our respondents which emotions, if any, they attributed to the vicarious touch videos. We cannot be sure whether their endorsement is connected to a perceived expression of love, or to something else.

There was also a significant difference in consoling rates between the samples for one of the full body interactions, a slow approach and hug including a pat on the back. Here, people who had not experienced a recent loss and took the perspective of consoler believed this touch to be more consoling than people currently grieving (although both rated the touch as overall consoling). Two-thirds of the sample taking the perspective of consolers also had experienced loss at some point in their life. This can be seen as a strength regarding their ability to evaluate appropriate touch behaviors; however, it also highlights the limitation of a potential sampling bias in the survey respondents. The two groups took on different perspective for the task (griever-consoler) in order to more closely represent a naturally occurring situation. Whilst the visual perspective (ego-centric vs allo-centric view) influences touch perception (Rigato et al., Citation2019; Vandenbroucke et al., Citation2015), few studies have investigated the touching-perspective employed in this study.

Social touch is well known to have a stress-buffering effect, to reduce cortisol and heartrate (Ditzen et al., Citation2007), and to evoke oxytocin-release (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2008; Walker et al., Citation2017). Especially slow stroking as in the “love”-gesture, a type of touch that activates the so-called C-tactile fibers (Olausson et al., Citation2010), is known to relate to stress-measures and interpersonal bonding (McGlone et al., Citation2014). It has furthermore been shown that touch-deprivation is associated with increased amounts of anxiety and loneliness in times of stress (von Mohr et al., Citation2017; von Mohr et al., Citation2021). This suggests potentially far-reaching physiological and psychological consequences relating to the types of consoling touch that our respondents reported wanting during times of grief. The importance of stress buffering effects of social touch in times of grief become especially clear when considering that changes of cardiovascular and immune function during grief have been observed (Brown et al., Citation2022; O'Connor, Citation2012; O’Connor, Citation2019) and might contribute to the increased morbidity and mortality risk after loss (O’Connor, Citation2019; Rees & Lutkins, Citation1967; Shor et al., Citation2012). Some studies have reported changes in neuroendocrine systems: cortisol levels are increased after loss and the diurnal profile fluctuates less in people with complicated grief (Hopf et al., Citation2020). Receiving the right touch from someone close might have the potential to contribute to increasing resilience and overall health in the grieving individual.

Grief as a bodily sensation

While psychological theories implicate the higher-order self in models of the grief-response (Boelen et al., Citation2006; Field et al., Citation2005; Hagman, Citation1995; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006), little is known on how the experience of one’s own body is affected by grief and how grief itself is embodied. Qualitative research suggests that the body does play an important role in the experience and management of grief (Pearce & Komaromy, Citation2022), however, this has not been shown systematically yet.

In accordance with our hypothesis, we found people perceiving grief to a large extent in specific locations in their body, i.e., first and foremost in the chest, followed by the stomach and head. These were the same locations where participants reported feeling the consoling effects of typical condolence rituals. This finding is in line with a more general mapping of emotions (not specifically in grieving individuals), that found sadness, despair, and loneliness to also be perceived in these areas (Nummenmaa et al., Citation2018). Interestingly, feelings of love, togetherness, closeness, and longing are perceived in overlapping regions, indicating that this location of the bodily sensation is not specific to emotions with negative valence.

We furthermore found that the majority of grieving participants reported that they perceived their own body and their bodily states less in the first 6 months after the loss, something which seems to be influenced by the degree of grief, with more grief being linked to less presence within the own body and less interoception (i.e., perception of internal bodily signals). Reduced interoception in times of grief would be well in line with qualitative reports of depersonalization and estrangement from one’s body (Gudmundsdottir, Citation2009). However, both previous work based on interviews and our work based on a self-report question does not allow for speculations regarding underlying mechanisms of altered interoception in grief. Interoceptive alterations have been shown in a number of psychiatric conditions where general symptomatology overlaps with that of prolonged grief disorder, e.g., depression and anxiety (Paulus & Stein, Citation2010). However, interoception itself is a multifaceted and multilayered construct, with potential dissociations between the different types of interoception (e.g., heartbeat interoception vs. intestinal interoception) and the different measures (e.g., interoceptive accuracy and awareness (Garfinkel et al., Citation2015). We—and hopefully others—will follow up on this here reported initial finding of altered interoception in grief within future empirical investigations.

Presence of the deceased

A majority of our grieving sample reported feeling the presence of the deceased at least once, often several times, and grief intensity related to the prevalence of felt presence. This feeling of a presence is a known phenomenon, which has been reported by 30–60% of grievers according to a recent review (Castelnovo et al., Citation2015). In our sample, an even slightly higher percentage of participants reported such experiences. Research on felt-presence experiences suggest that they can have both helpful but also negative impacts on the grieving individual, depending on the relationship between the bereaved individual and the deceased (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011), for example a feeling of the deceased being present might be helpful if it comes with an atmosphere of support, which might be based on the previous type of relationship, e.g., if the deceased was a supportive parent. If the relationship was strained, the feeling of a presence might come with an emotionally negative connotation. It would be interesting to investigate the phenomenology of these experience in more detail, similar to what has been done on voice hearing across cultures and conditions (Luhrmann et al., Citation2015, Citation2021). So far, there is still little research on felt presence experience and most studies are qualitative, interview-based studies in small samples. While outside of the scope of the current work, it should be mentioned that the felt presence experience offers phenomenological support for the predictive processing account as it might indicate the continued prediction of the presence of the deceased: the predictive coding account suggests that throughout our lifetime, we humans develop, train, and maintain a “model” of the world and of our selves (Friston, Citation2010; Seth, Citation2013). Such a model learns from somatosensory input and makes predictions about the causes of sensory experiences based on previously established expectations about contingencies in the world. One such contingency, for which we will have collected a lot of empirical evidence, is the presence of a loved one in the world. If this person dies, we will need strong and repeated evidence about their absence in order to be able to integrate this knowledge and “update the model” (for a related concept of grief as a learning process see (O’Connor & Seeley, Citation2022)). This process might be enhanced by salient experiences as through rituals surrounding death—maybe a reason why we humans developed these? Felt presence experiences might therefore be traces of such predictions about the presence of the lost loved one in the world. This could also explain the correlation between grief severity on the self-report scale and feelings of presence, which we obtained here: if grief is a learning process, feelings of presence might indicate an earlier stage in this learning process. Such experiences of felt presence are not confined to bereavement, but have been reported under many different circumstances, e.g., in schizophrenia, Parkinson’s, and as part of spiritual experiences (for a recent review on “felt presence experiences” see (Barnby et al., Citation2023)).

Limitations and future directions

Since grief is a complex, highly individual process influenced by biological, social, and cultural factors, there cannot be a single “normative” grieving process (Fuchs, Citation2018). Our sample did not examine differences in grief depending on the relationship to the deceased. However, our study corroborates the suggestion that some core phenomena of grief might be seen as shared experiences (Fuchs, Citation2018), such as the bodily experience of the grief. In addition to the individual variance of the grief experience, there is variance in grieving expressions and rituals between cultures (Rosenblatt, Citation2008; Silverman et al., Citation2021). The current study’s generalizability is limited by the same Western and Eurocentric sampling bias as many other studies in the field. How cultures deal with grief is also subject to change over time. Interpersonal touch in times of grief is a particular aspect which has been affected by recent external events (i.e., the covid-19 pandemic) (Petry et al., Citation2020). Our data collection occurred after most covid-related restrictions had been lifted, however, the recent loss sample included loss within the last 2 years, which might include loss experiences during the pandemic. In addition, the recent experience of enforced social distancing because of the pandemic might still influence responses regarding appropriate types of touch.

How individuals experience different types of touch and whether they want to be touched in a certain way and in a certain area of their body depends on emotional closeness, relationship, and the gender of the toucher and the touched (Suvilehto et al., Citation2015). Especially regarding consent to touch, it is highly important to note that our exploratory design did not differentiate for different types of relationship when asking which type of touch a person would consider consoling. This again calls for a more ecologically valid future study design where daily life touch interactions are assessed and evaluated in grieving individuals similar to what has done recently regarding social touch in the general population (Packheiser et al., Citation2023; Schneider et al., Citation2021)

Another important limitation is related to the allocation of the two samples. We use a somewhat random cutoff regarding the time since loss of a loved one in order to allocate people to the two groups. An alternative approach could have been to base the samples on current grief severity, e.g., based on a questionnaire. Participants in the “consoler-sample” did not fill out the grief-related questionnaires, so that we are not able to draw any conclusions regarding potential current grief symptoms they experienced during time of participation. We can therefore not draw conclusions whether differences between samples are attributable to the different roles (receiver and giver of touch) they were supposed to imagine when watching the videos, or whether differences in grief severity could account for different ratings. This could be followed up in future studies by implementing a second run where participants switch their imagined role and by evaluating grief scores across samples.

Conclusion

Considering that probably every human will experience loss in their life and will have to face grief—and considering that the grieving period has been identified as a phase of vulnerability with increased mortality and negative health consequences, it is of high importance to better understand how to support grieving individuals. However, death and rituals surrounding death and grief are not commonly discussed and do not receive much attention in the public nor in the personal realm (D. Harris, Citation2010; Walter, Citation1991). Our results are a first step toward a deeper understanding of the role of social touch in the grieving process and lay the ground for future investigations of the neural and behavioral mechanisms involved. In addition, we hope that our results might contribute to the development of novel interventions in individuals with complicated grief, and to informing the public on strategies of how to interact with grieving individuals. Such interventions might implement therapeutic touch in order to recover the body when people experience depersonalization and disembodiment or might encourage family and friends of the bereaved to incorporate consensual social touch in their consolation behaviors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: RB; Design: RB; Data acquisition: AE, RB; Data analysis and interpretation: AE, RB; Data visualization: AE, RB; Original draft: AE, RB; Final draft: AE, RB; All authors have approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All videos used for the vicarious touch ratings and minimally curated data are available at OSF https://osf.io/nxprt/, DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/NXPRT. The preprint of this manuscript was published on April 28th, 2023 at PsyArXiv doi: 10.31234/osf.io/mdhbq

Data deposition

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adam Enmalm

Adam Enmalm is Ph.D. student at Center for Social and Affective Neuroscience at Linköping University, Sweden. His dissertation studies investigate the role of touch for body perception and self-awareness.

Rebecca Boehme

Rebecca Boehme is an assistant professor at Center for Social and Affective Neuroscience at Linköping University, Sweden. She studies social interaction, interoception and the self. She is interested in how we establish a bodily self, how we connect with each other, and what happens to the self in psychiatric conditions.

References

- App, B., McIntosh, D. N., Reed, C. L., & Hertenstein, M. J. (2011). Nonverbal channel use in communication of emotion: How may depend on why. Emotion, 11(3), 603–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023164

- Barnby, J. M., Park, S., Baxter, T., Rosen, C., Brugger, P., & Alderson-Day, B. (2023). The felt-presence experience: From cognition to the clinic. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 10(5), 352–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00034-2

- Boehme, R., & Olausson, H. (2022). Differentiating self-touch from social touch. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 43, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.06.012

- Boelen, P. A., Van Den Hout, M. A., & Van Den Bout, J. (2006). A cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of complicated grief. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(2), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00013.x

- Brinkmann, S. (2019). The body in grief. Mortality, 24(3), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2017.1413545

- Brown, R. L., LeRoy, A. S., Chen, M. A., Suchting, R., Jaremka, L. M., Liu, J., Heijnen, C., & Fagundes, C. P. (2022). Grief symptoms promote inflammation during acute stress among bereaved spouses. Psychological Science, 33(6), 859–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211059502

- Bryant, R. A. (2012). Grief as a psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 201(1), 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.102889

- Burnett, P., Middleton, W., Raphael, B., & Martinek, N. (1997). Measuring core bereavement phenomena. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291796004151

- Burnett, P. C. (1997). Core bereavement items. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/26824/1/c26824.pdf

- Burrell, A., & Selman, L. E. (2022). How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives’ mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. Omega, 85(2), 345–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222820941296

- Cascio, C. J., Moore, D., & McGlone, F. (2019). Social touch and human development. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 35, 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.009

- Castelnovo, A., Cavallotti, S., Gambini, O., & D'Agostino, A. (2015). Post-bereavement hallucinatory experiences: A critical overview of population and clinical studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 186, 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.032

- Che, X., Luo, X., Chen, Y., Li, B., Li, X., Li, X., & Qiao, L. (2021). Social touch modulates pain-evoked increases in facial temperature. Current Psychology, 42(5), 3822–3831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01212-2

- Ditzen, B., Neumann, I. D., Bodenmann, G., von Dawans, B., Turner, R. A., Ehlert, U., & Heinrichs, M. (2007). Effects of different kinds of couple interaction on cortisol and heart rate responses to stress in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32(5), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.03.011

- DuBose, J. T. (1997). The phenomenology of bereavement, grief, and mourning. Journal of Religion and Health, 36(4), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1027489327202

- Dunbar, R. (1998). Grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language. Harvard University Press.

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(4), 681–694. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00032325

- Field, N. P., Gao, B., & Paderna, L. (2005). Continuing bonds in bereavement: An attachment theory based perspective. Death Studies, 29(4), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180590923689

- Fotopoulou, A., & Tsakiris, M. (2017). Mentalizing homeostasis: The social origins of interoceptive inference. Neuropsychoanalysis, 19(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2017.1294031

- Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

- Fuchs, T. (2018). Presence in absence. The ambiguous phenomenology of grief. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 17(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-017-9506-2

- Garfinkel, S. N., Seth, A. K., Barrett, A. B., Suzuki, K., & Critchley, H. D. (2015). Knowing your own heart: distinguishing interoceptive accuracy from interoceptive awareness. Biological Psychology, 104, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.11.004

- Garofalo, S., Giovagnoli, S., Orsoni, M., Starita, F., & Benassi, M. (2022). Interaction effect: Are you doing the right thing? PloS One, 17(7), e0271668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271668

- Goldstein, P., Weissman-Fogel, I., Dumas, G., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2018). Brain-to-brain coupling during handholding is associated with pain reduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(11), E2528–E2537. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1703643115

- Gudmundsdottir, M. (2009). Embodied grief: Bereaved parents’ narratives of their suffering body. Omega, 59(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.59.3.e

- Hagman, G. (1995). Chapter 12 death of a selfobject: Toward a self psychology of the mourning process. Progress in Self Psychology, 11, 189–205.

- Harris, D. (2010). Oppression of the bereaved: A critical analysis of grief in western society. Omega, 60(3), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.2190/om.60.3.c

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O'Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., & Duda, S. N. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Hayes, J., & Leudar, I. (2016). Experiences of continued presence: On the practical consequences of ‘hallucinations’ in bereavement. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 89(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12067

- Hentz, P. (2002). The body remembers: Grieving and a circle of time. Qualitative Health Research, 12(2), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973202129119810

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Birmingham, W. A., & Light, K. C. (2008). Influence of a “warm touch” support enhancement intervention among married couples on ambulatory blood pressure, oxytocin, alpha amylase, and cortisol. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(9), 976–985. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318187aef7

- Hopf, D., Eckstein, M., Aguilar‐Raab, C., Warth, M., & Ditzen, B. (2020). Neuroendocrine mechanisms of grief and bereavement: A systematic review and implications for future interventions. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 32(8), e12887. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12887

- Jablonski, N. G. (2021). Social and affective touch in primates and its role in the evolution of social cohesion. Neuroscience, 464, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.11.024

- Jedan, C., Maddrell, A., & Venbrux, E. (2018). Consolationscapes in the face of loss: Grief and consolation in space and time. Routledge.

- Kempson, D. A. (2001). Effects of intentional touch on complicated grief of bereaved mothers. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 42(4), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.2190/T1U8-JWAU-3RXU-LY1L

- Kissane, D. W., Bloch, S., & McKenzie, D. P. (1997). The bereavement phenomenology questionnaire: A single factor only. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 31(3), 370–374. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048679709073846

- Kreuder, A. K., Scheele, D., Wassermann, L., Wollseifer, M., Stoffel‐Wagner, B., Lee, M. R., Hennig, J., Maier, W., & Hurlemann, R. (2017). How the brain codes intimacy: The neurobiological substrates of romantic touch. Human Brain Mapping, 38(9), 4525–4534. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23679

- Lee Masson, H., & Op de Beeck, H. (2018). Socio-affective touch expression database. PloS One, 13(1), e0190921. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190921

- Luhrmann, T. M., Padmavati, R., Tharoor, H., & Osei, A. (2015). Differences in voice-hearing experiences of people with psychosis in the USA, India and Ghana: interview-based study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 206(1), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.139048

- Luhrmann, T. M., Weisman, K., Aulino, F., Brahinsky, J. D., Dulin, J. C., Dzokoto, V. A., Legare, C. H., Lifshitz, M., Ng, E., Ross-Zehnder, N., & Smith, R. E. (2021). Sensing the presence of gods and spirits across cultures and faiths. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(5), e2016649118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2016649118

- McGlone, F., Wessberg, J., & Olausson, H. (2014). Discriminative and affective touch: sensing and feeling. Neuron, 82(4), 737–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.001

- McIntyre, S., Hauser, S. C., Kusztor, A., Boehme, R., Moungou, A., Isager, P. M., Homman, L., Novembre, G., Nagi, S. S., Israr, A., Lumpkin, E. A., Abnousi, F., Gerling, G. J., & Olausson, H. (2022). The language of social touch is intuitive and quantifiable. Psychological Science, 33(9), 1477–1494. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211059801

- McIntyre, S., Moungou, A., Boehme, R., Isager, P. M., Lau, F., Israr, A., Lumpkin, E. A., Abnousi, F., & Olausson, H. (2019). Affective touch communication in close adult relationships [Paper presentation]. 2019 IEEE World Haptics Conference (WHC). https://doi.org/10.1109/WHC.2019.8816093

- Neimeyer, R. A., Baldwin, S. A., & Gillies, J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600848322

- Northoff, G., & Stanghellini, G. (2016). How to link brain and experience? Spatiotemporal psychopathology of the lived body. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 76. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00172

- Nummenmaa, L., Hari, R., Hietanen, J. K., & Glerean, E. (2018). Maps of subjective feelings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(37), 9198–9203. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1807390115

- O'Connor, M.-F. (2012). Immunological and neuroimaging biomarkers of complicated grief. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/mfoconnor

- O’Connor, M.-F. (2019). Grief: A brief history of research on how body, mind, and brain adapt. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(8), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000717

- O'Connor, M.-F., & Seeley, S. H. (2022). Grieving as a form of learning: Insights from neuroscience applied to grief and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 317–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.019

- Olausson, H., Wessberg, J., Morrison, I., McGlone, F., & Vallbo, A. (2010). The neurophysiology of unmyelinated tactile afferents. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(2), 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.011

- Osterweis, M., Solomon, F., & Green, M. (1984). Bereavement: Reactions, consequences, and care. National Academies Press.

- Packheiser, J., Sommer, L., Wüllner, M., Malek, I. M., Reichart, J. S., Katona, L., Luhmann, M., & Ocklenburg, S. (2023). A comparison of hugging frequency and its association with momentary mood before and during COVID-19 using ecological momentary assessment. Health Communication, 1–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37041685/, https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2023.2198058

- Paulus, M. P., & Stein, M. B. (2010). Interoception in anxiety and depression. Brain Structure & Function, 214(5–6), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-010-0258-9

- Pearce, C., & Komaromy, C. (2022). Recovering the body in grief: Physical absence and embodied presence. Health (London, England: 1997), 26(4), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459320931914

- Petry, S. E., Hughes, D., & Galanos, A. (2020). Grief: The epidemic within an epidemic. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 38(4), 419–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120978796

- Rees, W. D., & Lutkins, S. G. (1967). Mortality of bereavement. British Medical Journal, 4(5570), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5570.13

- Rigato, S., Bremner, A. J., Gillmeister, H., & Banissy, M. J. (2019). Interpersonal representations of touch in somatosensory cortex are modulated by perspective. Biological Psychology, 146, 107719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2019.107719

- Robinson, L. S. (1995). The effects of therapeutic touch on the grief experience. The University of Alabama at Birmingham.

- Rosenblatt, P. C. (2008). Grief across cultures: A review and research agenda. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: Advances in theory and intervention (pp. 207–222). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14498-010

- Savallampi, M., Maallo, A. M. S., Shaikh, S., McGlone, F., Bariguian-Revel, F. J., Olausson, H., & Boehme, R. (2023). Social touch reduces pain perception – An fMRI study of cortical mechanisms. Brain Sciences, 13(3), 393. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/13/3/393 https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030393

- Scheinfeld, E., Barney, K., Gangi, K., Nelson, E. C., & Sinardi, C. C. (2021). Filling the void: Grieving and healing during a socially isolating global pandemic. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(10), 2817–2837. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211034914

- Schirmer, A., Croy, I., & Schweinberger, S. R. (2022). Social touch—A tool rather than a signal. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 44, 101100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.101100

- Schneider, E., Hopf, D., Eckstein, M., Aguilar-Raab, C., Scheele, D., Hurlemann, R., & Ditzen, B. (2021). Salivary oxytocin and touch in everyday life: Results from an EMA study during Covid-19 lockdown. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 131, 105465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105465

- Seth, A. K. (2013). Interoceptive inference, emotion, and the embodied self. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(11), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.007

- Shor, E., Roelfs, D. J., Curreli, M., Clemow, L., Burg, M. M., & Schwartz, J. E. (2012). Widowhood and mortality: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Demography, 49(2), 575–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0096-x

- Silverman, G. S., Baroiller, A., & Hemer, S. R. (2021). Culture and grief: Ethnographic perspectives on ritual, relationships and remembering. Death Studies, 45(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1851885

- Simpkins, S. A., & Myers-Coffman, K. (2017). Continuing bonds in the body: Body memory and experiencing the loss of a caregiver during adolescence. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 39(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-017-9260-6

- Steffen, E., & Coyle, A. (2011). Sense of presence experiences and meaning-making in bereavement: A qualitative analysis. Death Studies, 35(7), 579–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.584758

- Suvilehto, J. T., Glerean, E., Dunbar, R. I., Hari, R., & Nummenmaa, L. (2015). Topography of social touching depends on emotional bonds between humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(45), 13811–13816. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519231112

- Team, J. (2022). JASP (Version 0.16.4) [Computer Program]. https://jasp-stats.org

- Vandenbroucke, S., Crombez, G., Loeys, T., & Goubert, L. (2015). Vicarious experiences and detection accuracy while observing pain and touch: The effect of perspective taking. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 77(5), 1781–1793. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-015-0889-2

- von Mohr, M., Kirsch, L. P., & Fotopoulou, A. (2017). The soothing function of touch: affective touch reduces feelings of social exclusion. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 13516. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13355-7

- von Mohr, M., Kirsch, L. P., & Fotopoulou, A. (2021). Social touch deprivation during COVID-19: effects on psychological wellbeing and craving interpersonal touch. Royal Society Open Science, 8(9), 210287. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.210287

- Walker, S. C., Trotter, P. D., Swaney, W. T., Marshall, A., & Mcglone, F. P. (2017). C-tactile afferents: Cutaneous mediators of oxytocin release during affiliative tactile interactions? Neuropeptides, 64, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npep.2017.01.001

- Walter, T. (1991). Modern death: taboo or not taboo? Sociology, 25(2), 293–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038591025002009