Abstract

The relationship between trauma and subsequent substance use has been extensively studied. Substance dependence and its consequences are a source of further traumatization. This explorative qualitative study is an analysis of the recovery narratives of persons with polydrug dependence, using mainly novel psychoactive substances (NPSs). NPS use, with its unpredictability and major health risks poses a challenge to treatment systems, but only few studies are available on NPS users’ recovery processes. In this longitudinal study, authors explore processes of identity reconstruction in the emotionally valent episodes of 10 respondents’ life interviews. The interviews had been conducted with 77 patients at the beginning of their residential treatment and were repeated a year later with those in recovery and available for the study, altogether 10 persons. Narrative Oriented Inquiry was used as a framework, focusing on the key themes and changes in the narrative mode. Our results support the findings on previous and subsequent NPS use-related traumatization. In this perspective, NPS use corresponds to revictimization. Contrary to available but sporadic evidence suggesting a marked difference between the recovery processes of users of classical substances and NPS users, the respondents in this study could utilize the traditional cultural stock of recovery stories during their treatment. Changes involved more reflective and responsible attitudes and the broadening of a healing social network. Contents describing care/self-care and the emergence of hopeful attitudes were also identified. Further research, involving larger samples and cross-cultural comparisons, could deepen our understandings of NPS users’ recovery processes.

Introduction

Novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) are drugs—either in pure form or in preparation—that are not controlled by international drug control conventions. Individual and community-level risks caused by their use are commensurable with or exceed those elicited by classical substances. By 2023, NPSs have become a global concern affecting 141 countries. The several hundreds of rapidly proliferating substances are categorized by their effect or chemical composition (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Citation2024). The main four types of these synthetic drugs are stimulants, cannabinoids, hallucinogens, and depressants (Shafi et al., Citation2020). Two common NPS types are synthetic cathinones (SCH, beta-ketone amphetamine analogs) and synthetic cannabinoids (SCB) (Prosser & Nelson, Citation2012). Early studies on NPSs focused on the puzzling multitude of these substances and the new risks associated with use, such as HIV-1 outbreak among synthetic cathinone users (Hanke et al., Citation2020), increased risk of Hepatitis C infection (McAuley et al., Citation2019), incidences of severe and sudden cardiac, neurological and psychiatric symptoms, and occurrences of death (Funada et al., Citation2019; Prosser & Nelson, Citation2012; Van Hout et al., Citation2018). Psychiatric symptoms include paranoia, bizarre and violent behavior, and acute psychotic episodes (Bennett et al., Citation2017). Further, NPS use is usually polydrug use, the concomitant use of two or more psychoactive substances multiplying the serious health risks (Higgins et al., Citation2021; Neicun et al., Citation2020; Rinaldi et al., Citation2020). Polydrug use entails unpredictable adverse effects and higher risks of overdose. Dependence occurs when the frequency or quantity of use leads to serious impairments in the bio-psycho-social domains (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs & Drug Addiction, Citation2021). Polydrug use and dependence are a feature possibly related to patient characteristics and to the addictive potentials, volatility, and unpredictability of NPSs.

In addition to the risks associated with the various NPSs, the ethnography of the different user groups, their motives and experiences, and appropriate clinical guidelines were among the researchers’ main questions (Abdulrahim & Bowden-Jones, Citation2015; Gittins et al., Citation2018; Van Hout et al., Citation2018; Wieczorek et al., Citation2022). Marginalized and nightlife users are a traditional user group. The broadband internet, smartphones, and social media established new user communities and new risks (Kaló & Felvinczi, Citation2017). Enhancement and expansion were associated with the contexts of use or NPS type (Wieczorek et al., Citation2022), whereas social and conformity motives characterized the user groups (Benschop et al., Citation2020). In several countries, NPS use is widespread among marginalized groups living under the poverty threshold (Felvinczi et al., Citation2020). In these groups, users’ preexisting poor physical and mental conditions, hopelessness, and helplessness add to the above risks. In addition, access to health services for persons with drug-related problems might be deficient in these areas. Marginalized groups use NPS to escape from their everyday reality and the pains of unsolvable problems (Csák et al., Citation2020). In a study, however, NPS use was found to be associated with mental health problems more than with socioeconomic vulnerability (Neicun et al., Citation2020).

Several studies have confirmed the strong relationship between traumatic life events and substance use disorder (SUD) (Van den Brink, Citation2015). The connections between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use have been extensively studied (Basedow et al., Citation2020; Dass-Brailsford & Myrick, Citation2010; Najavits, Citation2015; Schein et al., Citation2021; Van den Brink, Citation2015). Few articles are available on the specific relationship between NPS use and psychological trauma (Gittins et al., Citation2018). Kassai et al. (Citation2017) identified SCB use as a particular type of trauma.

Recovery processes from NPS dependence have also remained an under-researched area as only few subjects are available for the studies (Kassai et al., Citation2017). These studies are the first step to know more about the recovery processes from NPS use, which represents a new paradigm deeply challenging the treatment systems (Rácz et al., Citation2016).

Recovery from addictions

Recovery is a process to improve one’s health, wellness, and autonomy and develop one’s full potential in life (SAMSHA, Citation2012). Anthony, highlighting the relational aspects of recovery, described it as “a deeply human experience, facilitated by the deeply human responses of others.” (Anthony, Citation1993, p. 531). Mudry et al. (Citation2019) explored the transformative pathways in natural recovery and the major changes in interpersonal relationships from pathologizing modes to healing relational patterns.

The recovery concept and practices of self-help groups informed the professional theories and models in addictions (Arbour & Harris, Citation2023; Madácsy, Citation2020). Twelve-step recovery communities and therapeutic communities (TCs) rely on the social support provided by the sober community as well as on the rich knowledge of those in sustained recovery as experts by experience. These communities equip the service users with SUD with rich narrative resources to facilitate therapeutic change (Harrison et al., Citation2020; Mudry et al., Citation2019). Recovering persons’ own interpretations of recovery include adopting new lifestyles, enhanced well-being, self-development, accepting what life can give, abstinence, the ability to identify problems, and adequate help-seeking behavior (Laudet, Citation2007). Recently, studies on the potential connections between recovery from addictions and post-traumatic growth have appeared, emphasizing the role of spirituality and community support (Haroosh & Freedman, Citation2017; Ogilvie & Carson, Citation2022; Stokes et al., Citation2018).

Though abstinence is not sobriety, programs that require abstinence have been proven more effective. In their survey study, Kaskutas et al. (Citation2014) described four recovery domains: abstinence, essentials of recovery, enriched recovery, and a spiritual orientation. Essential recovery comprises honesty to oneself, an ability to manage negative emotions while maintaining abstinence and enjoying life without substance use. Enriched recovery involves growth and development, giving a balanced response to life’s ups and downs, and taking responsibility for the things one can change (Kaskutas et al., Citation2014). Jacob et al. (Citation2017) found that carers’, and consumers’ perspectives on recovery differed: carers focused more on the outcomes, mainly understood as freedom from symptoms; for the consumers, recovery was a complex process comprising personal growth and transformation while finding new meaning and purpose in life. Available social support, reciprocity in one’s relationships, follow-ups, and taking personal responsibility for one’s health were identified as key elements during the personal journey from an addict identity to a sober identity marked by increased well-being.

In sum, recovery from addictions is understood as a substantial identity transformation, a second birth or redemption leading to a personally, socially, and spiritually meaningful life (James, Citation1902/1982). The journey with its crises, guiding the person toward a sober identity with vital improvements that permeate all areas of life, is a demanding developmental task. It is a holistic, nonlinear process involving not only deep transformations but the restructuring of daily life as well (Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel, Citation2007; Costello et al., Citation2020). The process requires growing commitments and an ability to learn from one’s mistakes.

Stages and processes of recovery are usually determined according to the transtheoretical model by Prochaska et al. (Citation1992). Precontemplation is characterized by denial, defensiveness, and a focus on the positive impacts of the drug. Recovery seems an irrational, meaningless, and unmanageable endeavor. The next phase, contemplation is characterized by ambivalence. The person is willing to consider drug-free ways of life. Preparation involves steps to quit and/or organize some treatment. Minor changes in personal life are possible, including temporary abstinence. The action stage is about commitment to change. In this phase, persons learn how to ask for help when needed and can identify and manage relapse. Maintenance is characterized by self-care and a sober lifestyle.

The health learning model, describing the specific recovery processes in the context of a therapeutic community (TC), comprises three main elements:

reacting to the program with a focus on the whats (actions, structures, etc.), but not understanding the hows and the whys yet,

working the program and building conscious recovery competence manifested in self-monitoring and an awareness of risks,

responding to the program and achieving a stage of reflective competence with deepening explorations and insights into the personal meaning of recovery (Kelemen & Erdos, Citation2010).

Based on these models, a constructive therapeutic change involves growing commitment to recovery, developing healthier habits, an ability to identify the risk of relapse, asking for help when needed, and the development of reflective skills. For the majority, it takes about two years to reach a stage marked by some stability. Therefore, we identified the respondents in this study as patients in early recovery, proceeding from their preparations to actions and reflections.

Narrative practice

The title of this study refers to a seminal work by two narrative therapists (White & Epston, Citation1990). Changes in narrative identity take place in the dual landscape of events and actions, establishing new coherence and directionality by reconstructing and expressing personal meanings. Narratives connect personal experiences to cultural meanings and social structures and establish the narrator’s position for potential actions (Hiles & Čermák, Citation2013). Narrative frames open the door to new possibilities for deconstructing and reconstructing disorganized, dissociated, or oppressive-dominant narratives—the silenced stories in the domain of the not-yet-said (Neimeyer, Citation2006; Rober, Citation2002). Narrative therapies highlight the importance of telling and retelling (re-authoring, restructuring) the problem-saturated life story, thereby creating new positions and prospects for the future (Tarragona, Citation2008). Trauma, if unexpressed and unanalyzed, often becomes insidious, leading to a variety of health problems. Studies have confirmed that speaking and writing about one’s traumatic experiences lead to enhanced well-being (Chung & Pennebaker, Citation2007; Pasupathi et al., Citation2015; Pennebaker & Smyth, Citation2016).

Storytelling has always been central to twelve-step practices (Arminen, Citation1998; Kiss et al., Citation2022; Madácsy, Citation2020). Rennick-Egglestone et al. (Citation2019) identified several positive outcomes of using personal narratives to support the recovery process. The recipients of the stories could experience connectedness, validation, hope, empowerment, appreciation, reference shift, and stigma reduction. Negative impacts comprised feelings of inadequacy, disconnection, pessimism, and burden. Perceived authenticity facilitated positive changes, while a crisis state was conducive to negative impacts (Rennick-Egglestone et al., Citation2019).

Hänninen (Citation2004) distinguished between three main narrative modes in her model on narrative circulation. The told narrative is a manifest verbal representation of events. The inner narrative is the domain of the not-yet-said that can be externalized and validated by relying on one’s cultural resources and can be transformed into a told narrative during therapy (Rober, Citation2002). The lived narrative is the “real-life drama” with its situational constraints (Hänninen, Citation2004, p. 69). In the model, the inner narrative is connected to both the told and the lived modes, and the personal stock of stories is defined by the cultural stock of stories and the person’s own experiences.

Hänninen and Koski-Jännes (Citation1999) in a qualitative study on 51 recovery narratives have described five story types. As tools for meaning making, the different types offer personalized and culturally matching storylines for identity change.

The AA story: excessive drinking, loss of control, and hubris—as the symptoms of a lifelong disease—lead to isolation and impairments in all areas of life. In the AA narratives, this is hitting rock bottom, the most profound crisis in the addict’s life. Repeated own attempts at recovery fail until the person has learned humility and has joined Alcoholics Anonymous, a potent community resource to master decent ways of life. In this conception, the person is a victim of a disease, and they must learn how to live with it. The only cure is one’ personal commitment to a sober community.

The personal growth story sees addiction as the result of early oppressive relationships and neglect. Growing emancipation, autonomy, and agency are the keys to recovery. The person, a previous victim, should find their own true self instead of conforming to others’ wishes. They are like a “butterfly breaking out of a cocoon” (Hänninen & Koski-Jännes, Citation1999, p. 1842).

The co-dependence story is characterized by silenced stories, a transgenerational “curse.” Addiction is the result of secrecy and the repression of own negative feelings, and recovery is that of honesty and breaking the curse of the transmission by the victim of a victim.

The love story: addiction is a compensation for the lack of love. Recovery occurs when love is given.

The mastery story: initially, addiction is seen as a source of autonomy and later as a threat to autonomy, self-respect, and responsibility. This insight, as the triumph of reason, leads to recovery and the construction of a strong and good self.

These storylines help the person comprehend addiction and recovery, release them from guilt, and give them hope. Each framework is related to a particular gender and type of addiction, though the respondents often integrated the elements of other stories into their narratives. The AA story as a framework was used predominantly by men with alcohol dependence, whereas women preferred the personal growth story. The co-dependence story was characteristic of polydrug users. Love story as a framework was used mainly by persons with bulimia, and the mastery story was characteristic of smokers (Hänninen & Koski-Jännes, Citation1999).

Current study

Kassai et al. (Citation2017) have claimed that NPS users’ recovery processes may differ from those of the users of classical substances. Unpredictable and rapid alternations between NPS users’ positive and negative experiences result in a more fragmented user identity. Therefore, SCB users cannot successfully organize their experiences into collective structures of meaning, and the narrative resources for SCB users to construct a new, non-addict identity during recovery are limited. However, Kassai et al. (Citation2017) could explore a small sample of patients at the beginning of their treatment.

In the TCs providing long-term residential care, the interventions are directed at the social self and facilitate the improvement of mentalizing skills (Fonagy et al., Citation2002), the management of emotions, and the overall reconstruction of identity. Respondents are familiar with and actively use twelve-step resources that highlight relational ethics in interpersonal relationships and the role of spirituality in the healing process.

Therefore, we would predict that progress in recovery is indicated by a more elaborate and balanced view, mirroring the overall development of reflective skills. A spiritual orientation, characteristic of post-traumatic growth, may appear. However, no specific results concerning NPS users’ use of recovery narratives are available. As this is a qualitative exploratory study, we maintain the openness of our analysis, also focusing on the emerging issues—the whats and hows.

Methods

Participants

This sample is a sub-sample of a longitudinal study conducted among 77 patients. Respondents were recruited at the beginning of their treatment. NPS use was confirmed by biological tests. A year later, 10 persons could meet the inclusion criteria of this research (1 year abstinence, and at least 3 months spent in treatment) (Mage = 28.50; SD = 9.03; Min. = 18.00; Max. = 45.00), 1 female and 9 males (Mmonths = 9.1; SD = 1.91; Min. = 5.00; Max. = 10). All of them were polydrug users diagnosed with substance dependence and treated in a TC. is a summary of patient data.

Table 1. Respondents’ demography.

Considering Malterud et al. (Citation2016) principles on information power, this sample size is adequate for our research questions. The narrow research aim, a specific sample, a hybrid analysis combining deductive and inductive directions, and a strong dialogue (the interviews were conducted by a therapist) result in high information power. The study combines case-based and cross-case analyses (Malterud et al., Citation2016).

Ethical approval was issued by the University of Pécs (PTE KK RIKEB, 2019.05.02). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before their inclusion in the study.

Measures

The Foley Life Interview (FLI) is a scheme to facilitate in-depth explorations of the life narrative (McAdams, Citation1993, Citation2007). FLI designates key scenes (nuclear episodes) as peak or nadir experiences, turning points, childhood/adult memories, major loss, and a spiritual/religious experience. In a study conducted in the US on emotionally valent episodes among persons with SUD, the occurrence of redemption sequences as positive meaning making in one’s nadir point texts, together with positive meaning making in high point texts, were indicative of enhanced well-being (Cox & McAdams, Citation2014).

The episodes used in this study were translated by the authors and were the responses to the following questions (the first sentences are quoted verbatim from the original):

High point. Please describe a scene, episode, or moment in your life that stands out as an especially positive experience. This might be the high point scene of your entire life, or else an especially happy, joyous, exciting, or wonderful moment in the story (…)

Low point. The second scene is the opposite of the first. Thinking back over your entire life, please identify a scene that stands out as a low point, if not the low point in your life story (…)

Turning point. In looking back over your life, it may be possible to identify certain key moments that stand out as turning points—episodes that marked an important change in you or your life story (…) (McAdams, Citation2007, p. 2); for further details, please see McAdams (Citation2007).

Procedures

In our study, FLI was conducted when respondents entered treatment after detoxification. Basic sociodemographic data were also collected. The interview was repeated a year later. FLI was conducted in the respondents’ own language, Hungarian.

Following the phenomenological tradition by staying close to the data with a strong focus on the respondents’ unique experiences and meaning making enables the researcher to identify the potentially relevant themes and thematic connections when studying an unexplored phenomenon. For the analysis, we used Narrative Oriented Inquiry (NOI), which, with its pluralistic approach, is a flexible qualitative framework enabling case-based, idiographic approaches and cross-case comparisons (Hiles & Čermák, Citation2013; Kiss et al., Citation2022). This analysis, a combination of theoretically established and explorative directions, utilizes the fabula/sjuzet differentiation as an analytical tool. Fabula describes the events and themes (what exactly is told), and sjuzet, the way the stories are told (Hiles & Čermák, Citation2013). After reading the narratives, we decided to focus on the emotionally valent nuclear episodes (high point, nadir point), an approach by Cox and McAdams (Citation2014), and on the turning point, a recurrent topic in the studies on recovery. The analysis involved parallel readings and re-readings of the episodes and repeated discussions between the authors. As a concluding step, we used ATLAS.ti 8.3, a tool for qualitative data analysis, to make our work more robust and transparent, and the results, easily comparable (For the data, please see the data availability statement).

Results

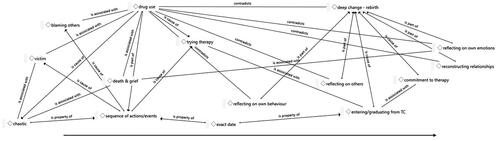

In this section, we summarize the major changes in the respondents’ perspectives. We also provide brief quotations mirroring the respondents’ lived experiences and then interpret and discuss these. are a summary of the main results, comprising the key contents and the changes in the three nuclear episodes between the first and second interviews.

Table 2. Major changes in the fabula/sjuzet in high point excerpts in the 1st and 2nd interviews.

Table 3. Major changes in the fabula/sjuzet in low point texts in the 1st and 2nd interviews.

Table 4. Major changes in the fabula/sjuzet in turning points in the 1st and 2nd interviews.

Changes in high point episodes

shows that initially, six speakers identified high points as identical with or closely related to substance use. Chloe and Patrick (seeing drinking “necessary” in the first episode) mentioned the birth of their own child as a peak experience, accompanied by substance use. Interestingly, both Rory’s and Zach’s initial high point texts follow the narrative organization of a recovery narrative (a personal growth story, Hänninen & Koski-Jännes, Citation1999), but these newly discovered, more colorful, and attractive selves are related to the use and not recovery. Positive experiences of “normie” life are also related, such as good education and having a family. However, these matter-of-fact descriptions are in contrast with the high emotional valence of Devin’s and Zach’s summaries on substance use. Religious spirituality is a core theme for Charles.

In the second excerpt, entering the TC is often seen as a high point, and the key concepts of recovery appear. Substance use is not identified as a high point experience anymore (“was not real”), and the idea of controlled use (as in Alex’s first text) is not raised either. Reflections on happy and painful moments, a broadening social network with sober fellows, and emotionally meaningful relationships are a common themes in the episodes. Aidan and Alex speak about the beginnings of a new life and experiencing recovery-related spirituality. Others refer to the end of denial and self-deception—a recognition that the “more colorful self” was a false one (Patrick, Charles, Chloe, and Zach).

Rory’s narrative is rich in the prototypical elements of a hero’s story, in which the protagonist successfully fights the difficulties, and his achievements are validated in the new environment. This finding is similar to the results of a narrative study involving experts by experience by Kiss et al. (Citation2022).

Speakers are more reflective and self-reflective, also establishing links between past and present experiences and future anticipations. In the second high point episode, several speakers gave a more balanced and realistic evaluation, mentioning some negative aspects of a generally positive experience. Taking responsibility for others is another new theme (Patrick and Pete). When speaking about reconstructing his relationship with his elder children, Patrick noted the relational distance and interpreted it as a natural consequence of his former use. Devin mentioned his fears, and Archie reflected on his traumatizing relationship with his father. However, these negative experiences did not compromise the overall positive value and did not transform the high point story into a sequence of contamination (Cox & McAdams, Citation2014).

Changes in nadir point episodes

In the first nadir point episodes (), speakers usually reported problems associated with substance use or a traumatic event before the onset of use. Some respondents told a different second story; for example, Aiden mentioned a traffic accident first, but his second story was about his own role as a perpetrator in a family conflict leading to violence, with his children witnessing the event. For Rory, rejection by his former friends made him come face to face with the fact that he was no longer acceptable to his former classmates as a heavy user. The same speaker’s grief experience in the second episode—the loss of his father and the guilt he felt about it—is at a much deeper emotional level. Alex’s initial story, a chaotic report on a party experience, is also in sharp contrast with the consequences of the extreme parental neglect he experienced as a teenager. These speakers could share a deeply personal story of the losses they had suffered and the shame they had felt. The three stories seem to be the ones that the respondents were not able to relate to a year before. Others, as Patrick, Charles, Devin, Chloe, Zack, Pete, or Archie told the same or a very similar story, but this time they could share more details, also identifying and describing their own painful emotions. They took responsibility for what they had done—or had missed to do. They could reflect on their own aggression and the harm they had caused to others; and on the emotional numbness related to addiction. They could speak about their previously suppressed grief experiences and suicidal ideations accompanying their substance use.

Changes in turning point episodes

In the turning point episodes (), speakers either mentioned various events related to substance use or their first attempts at recovery, which might imply that they were at different stages in the recovery cycle when entering treatment. Initial help-seeking or previous treatment attempts often changed the user’s perspective and interfered with substance use. Confrontation with the potential consequences also appears in the excerpts, as, for example, in Pete’s recollections on a friend’s NPS-related death or the ankle monitor Archie had to use. Patrick’s hopes for controlled use, a way back to recreational drinking represents a common idea of dependent persons—one that they usually give up in the ongoing recovery process.

A year later, the turning point was entering the TC and/or progressing from an initially ambivalent phase toward a growing commitment to the therapeutic program. These second stories are often about asking for help. A deep change, a choice between life and death (“second chance,” “clean or die,” “this is when all ‘me’ begins,” etc.) is present in almost all the cases. One respondent, Pete defined change as a developing ability to experience and value everyday realities. Taking responsibility for their own lives is also a common theme for most respondents. Mentioning the exact dates (Aidan, Rory, and Pete) is telling about the emotional significance of the event. It is worth noting that Alex instinctively used the 24-h focus (a practice of twelve-step groups) to stay alive and cope with his suicidal thoughts.

Summarizing group-level changes in the three episodes

When quantifying the results, we could see that most follow-up excerpts (21 of the 30 by the 10 respondents) were about a different story in either the high, low, or turning point texts. In some cases, the storyline was essentially the same, but the narrative mode was quite different (nine of all the episodes by seven respondents). This included, among others, a marked increase in reflections, understood here as connecting one’s own or others’ emotions and behavior to life events and experiences. In the first interviews, non-reflected sequences of actions and events were related, usually in a chaotic manner. Blaming others for one’s fate, unresolved traumas, such as death and grief, and identifying oneself as a victim of substance use and of other people were characteristic of the texts. First attempts at entering treatment were also related. Contrastingly, the second excerpts were about deep changes in life (in 12 excerpts by eight respondents). Commitment to therapy also appeared in six episodes by five interviewees. In the 30 excerpts by the 10 respondents before therapy, we could identify four occurrences of reflections on the participant’s own behavior by three respondents. In the follow-up interviews, we coded 18 occurrences by nine speakers. Initially, reflections on the respondent’s own emotions were presented in five excerpts by four respondents. After one year, this was the second most frequent content with 15 occurrences in nine of the cases. These reflections included a more elaborate view of past relational losses, grief, drug use, and suicide attempts. Reflecting on others’ situations, and parallel efforts to reconstruct one’s relationships were entirely missing from the first interviews but appeared in the second narratives, with five occurrences/four persons of the first one (reflecting on others) and eight occurrences/six persons of the second one (reconstructing relationships). is a summary of the results. The arrow indicates the direction of the changes during the one year.

Discussion

This study used NOI (Hiles & Čermák, Citation2013) to explore changes in NPS-user polydrug dependent persons’ narratives during early recovery as they were working through the recovery program and progressed from their preparations to actions and reflections.

In light of previous results on the etiological role of psychological trauma in SUD (Van den Brink, Citation2015), also supported by our research, NPS use corresponds to revictimization. Respondents’ experiences could meet the rigorous definition of psychological trauma by DSM-5 (Pai et al., Citation2017). This population suffered severe traumas, such as the loss of a parent at an early age, neglect and abuse, criminalization, sex work, rape, homelessness, social isolation, aggression, and severe mental and physical conditions associated with drug use. These traumatic experiences existed either as inner narratives in the domain of the not-yet-said when the respondents entered treatment, or their first stories were chaotic, self-centered, and polarized. Balanced reflections were missing. These features indicate the high emotional significance and low levels of integration of the traumatic experience, which explains speakers’ inability to structure and narrate their life stories adequately. Previous studies found that the appearance of growth meanings was related to enhanced well-being and more adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Cox & McAdams, Citation2014; Pasupathi et al., Citation2015). In this study, respondents were able to restructure the disorganized and dissociated narratives that had existed only as inner narratives. Some speakers mentioned exact dates in their texts, conforming themselves to 12-step storytelling traditions. This is how they designated the boundary between the addict self as “damaged self” or “spoiled identity” as in Kassai et al. (Citation2017, p. 1048), or a “beast” as a respondent’s self-identification in the current study, and the sober, recovering, new-born self, more ready to cope with life’s challenges.

The recovery journey is unique and cannot be described as a simple linear movement between the different stages. As relapse is frequent in persons with SUD, respondents’ nuclear episodes may reflect varied levels of commitment to treatment. At the beginning of the treatment, substance use was strongly attached to high point experiences in life, even if ambivalence was present. However, the turning point stories, predominantly negative events in the first excerpts, were exchanged for positive experiences and commitment to treatment.

Speakers mentioned few relationships in the first episodes, and the social connections they reported were either fellow users or close family members. Most low point stories were about substance use-related personal losses or betrayal. A year later, a healing social network was formed, and sober fellows, friends, and colleagues populated the recovering persons’ lifeworld. This is a finding that Costello et al. (Citation2020) could also identify in their study on early recovery.

In their second nuclear episode, the respondents related substance use to their other difficulties in life. Changes in the narrative mode included more emotional and self-reflective content. Several studies have concluded that thematic and stylistic changes in one’s narratives are parallel to transformations in mental states and identity (Cox & McAdams, Citation2014; Pasupathi et al., Citation2015; Pennebaker et al., Citation2003; Stelzer et al., Citation2019; Stephenson et al., Citation1997). In a study on a non-clinical sample by Pennebaker and Smyth (Citation2016), expressing and reflecting on trauma-related contents and on the accompanying emotions have resulted in marked and sustained positive changes in respondents’ physical and mental health—even if expressing was initially painful for the participants. Further, naturally switching between the perspectives when relating a traumatic experience has led to marked improvements in physical and mental health (Pennebaker & Smyth, Citation2016; Seih et al., Citation2011).

Reflections on others’ emotions and behaviors and efforts to reconstruct interpersonal relationships were key contents in the second nuclear episode. Respondents were willing to consider other people’s perspectives, conforming themselves to shared social realities. These changes can best be described as developments in mentalization, an ability to assess, interpret, and adequately respond to others’ and our own mental states and connect these to our experiences (Fonagy et al., Citation2002). As a result, guilt and shame were exchanged for responsibility, and respondents could accept their imperfections.

Kassai et al. (Citation2017) identified salient differences between NPS users’ meaning-making processes and experiences and those of the users of classical substances at the beginning of their treatment. The results of our longitudinal study suggest that NPS users with polydrug dependence can learn to utilize the traditional narrative resources of sober communities, most importantly, the AA-story (Hänninen & Koski-Jännes, Citation1999). Though the AA-story seemed dominant in this study, elements of the personal growth story, love story, co-dependence story, or mastery story also appeared. In the active phase of their addiction, these patients used a variety of substances; now as persons in recovery, they combined the narrative elements of the different recovery stories.

With NPS users, the drugs, the patterns of use, and the initial experiences differ, but the underlying problems of dependence, as well as subsequent constructive meaning-making processes, are similar to those of the users of classical substances. Their recovery processes can be interpreted as post-traumatic growth involving the reevaluation of major life events and people, the appreciation of everyday pleasures in life, and understanding oneself more (Ogilvie & Carson, Citation2022).

Limitations

The strengths of this study are its novelty, a highly specific sample of persons who are difficult to reach, the respondents’ confirmed NPS use and abstinence to eliminate self-report bias (McKernan et al., Citation2015), the interview scheme facilitating in-depth explorations, and a longitudinal approach. Patterns of use—NPS use embedded in polydrug use—is consistent with a recent finding by Higgins et al. (Citation2021). This may be a limitation, but perhaps a fact of life that researchers must cope with. Respondents in this sample used different types of NPSs, classical substances, prescription drugs, and alcohol in a chaotic manner, as patients with severe forms of SUD often do. Further, it was difficult to judge respondents’ exact stage of recovery, as it is a cyclic process, and NPS use, with its volatility and unpredictable consequences, probably added to the confusion. The age range was relatively broad, with one female participant in the sample. With all these constraints, the results of this research may add to our understanding of recovery from NPS-related polydrug dependence.

Implications

Our results suggest that the long-term treatment needs of patients with NPS dependence—a form of polydrug dependence—are similar to those of the users of classical substances. Recovering persons in this study could utilize the narrative resources that enabled them to learn and adopt a mentalizing stance, a combination of empathy and mindfulness (Fonagy et al., Citation2002).

Future directions

Further research, preferably involving larger and international samples enabling cross-country comparisons is necessary to investigate the recovery processes of this specific population. Controlled trials could be convincing, but in such cases, researchers would face many practical difficulties due to the chaotic nature of NPS use and the confused patterns of recovery with frequent episodes of relapse. Further, those not in recovery are usually not motivated to participate in a research project. Case studies to evaluate long-term advances in recovery from NPS use could also be utilized as a complementary in-depth research method.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (30.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing their stories with us and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The ethical approval excludes publishing the interviews (in Hungarian) as these could identify the respondents. The codebook and the frequency tables are generated by ATLAS.ti 8.3 are available at https://pea.lib.pte.hu/handle/pea/44417.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ferenc Császár

Ferenc Csaszar, MSc in Clinical Psychology, MD, Psychiatrist at the Department of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, University of Pécs, Clinical Center, Szigetvár Hospital Branch. He is a PhD candidate at the Doctoral School of Neurosciences, University of Pécs. His main area of interest is novel psychoactive substance use and psychotherapeutic methods to increase the efficacy of treatment for substance use disorder, affective disorders, and bipolar disorder.

Marta B. Erdos

Marta B. Erdos, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor in Mental Health and Clinical Social Work at the Department of Community and Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Pécs, Hungary. Before starting her academic career as a lecturer and qualitative researcher in 2000, she used to work as a counselor at an outpatient crisis intervention center. Her main area of research interest is identity transformations.

Rebeka Javor

Rebeka Javor, Ph.D. is a counselor at the Medical School, University of Pécs, Hungary and a member of the Social Innovation Evaluation Research Center at the Department of Community and Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Pécs. Her main area of research interest is clinical psychology, student counseling, and identity development.

Gabor Kelemen

Gabor Kelemen, PhD, MD, is a Professor Emeritus at the Department of Community and Social Studies, University of Pecs, Hungary, and a consultant psychiatrist at CGL Bromley Drug & Alcohol Service, UK. His areas of research interest are recovery from addictions and the phenomenology of shame.

References

- Abdulrahim, D., & Bowden-Jones, O. (2015). Guidance on the management of acute and chronic harms of club drugs and novel psychoactive substances. NEPTUNE.

- Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095655

- Arbour, S., & Harris, H. (2023). Personal recovery: The discussion continues. Journal of Recovery in Mental Health, 6(2), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.33137/jrmh.v6i2.41439

- Arminen, I. (1998). Therapeutic interaction. A study of mutual help in the meetings of alcoholics anonymous. The Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies.

- Basedow, L. A., Kuitunen-Paul, S., Roessner, V., & Golub, Y. (2020). Traumatic events and substance use disorders in adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00559

- Bennett, K. H., Hare, H. M., Waller, R. M., Alderson, H. L., & Lawrie, S. (2017). Characteristics of NPS use in patients admitted to acute psychiatric services in Southeast Scotland: A retrospective cross-sectional analysis following public health interventions. BMJ Open, 7(12), e015716. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015716

- Benschop, A., Urbán, R., Kapitány-Fövény, M., Van Hout, M. C., Dąbrowska, K., Felvinczi, K., Hearne, E., Henriques, S., Kaló, Z., Kamphausen, G., Silva, J. P., Wieczorek, Ł., Werse, B., Bujalski, M., Korf, D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). Why do people use new psychoactive substances? Development of a new measurement tool in six European countries. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 34(6), 600–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120904951

- Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel (2007). What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001

- Chung, C., & Pennebaker, J. (2007). The psychological functions of function words. In K. Fiedler (Ed.), Social communication (pp. 343–359). Psychology Press.

- Costello, M. J., Sousa, S., Ropp, C., & Rush, B. (2020). How to measure addiction recovery? Incorporating perspectives of individuals with lived experience. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9956-y

- Cox, K., & McAdams, D. P. (2014). Meaning making during high and low point life story episodes predicts emotion regulation two years later: How the past informs the future. Journal of Research in Personality, 50, 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.03.004

- Csák, R., Szécsi, J., Kassai, S., Márványkövi, F., & Rácz, J. (2020). New psychoactive substance use as a survival strategy in rural marginalised communities in Hungary. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 85, 102639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102639

- Dass-Brailsford, P., & Myrick, A. C. (2010). Psychological trauma and substance abuse: The need for an integrated approach. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 11(4), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838010381252

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2021). Polydrug use: health and social responses. Retrieved from https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/mini-guides/polydrug-use-health-and-social-responses_en

- Felvinczi, K., Benschop, A., Urbán, R., Van Hout, M. C., Dąbrowska, K., Hearne, E., Henriques, S., Kaló, Z., Kamphausen, G., Silva, J. P., Wieczorek, Ł., Werse, B., Bujalski, M., Demetrovics, Z., & Korf, D. (2020). Discriminative characteristics of marginalised novel psychoactive users: A transnational study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(4), 1128–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00128-8

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. Other Press.

- Funada, D., Matsumoto, T., Tanibuchi, Y., Kawasoe, Y., Sakakibara, S., Naruse, N., Ikeda, S., Sunami, T., Muto, T., & Cho, T. (2019). Changes of clinical symptoms in patients with new psychoactive substance (NPS)-related disorders from fiscal year 2012 to 2014: A study in hospitals specializing in the treatment of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology Reports, 39(2), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/npr2.12053

- Gittins, R., Guirguis, A., Schifano, F., & Maidment, I. (2018). Exploration of the use of new psychoactive substances by individuals in treatment for substance misuse in the UK. Brain Sciences, 8(4), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8040058

- Hanke, K., Fiedler, S., Grumann, C., Ratmann, O., Hauser, A., Klink, P., Meixenberger, K., Altmann, B., Zimmermann, R., Marcus, U., Bremer, V., Auwärter, V., & Bannert, N. (2020). A recent human immunodeficiency virus outbreak among people who inject drugs in Munich, Germany, is associated with consumption of synthetic cathinones. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 7(6), ofaa192. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa192

- Hänninen, V. (2004). A model of narrative circulation. Narrative Inquiry, 14(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.14.1.04han

- Hänninen, V., & Koski-Jännes, A. (1999). Narratives of recovery from addictive behaviours. Addiction, 94(12), 1837–1848. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941218379.x

- Haroosh, E., & Freedman, S. (2017). Posttraumatic growth and recovery from addiction. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1369832. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1369832

- Harrison, R., Van Hout, M. C., Cochrane, M., Eckley, L., Noonan, R., Timpson, H., & Sumnall, H. (2020). Experiences of sustainable abstinence-based recovery: An exploratory study of three recovery communities (RC) in England. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9967-8

- Higgins, K., O'Neill, N., O'Hara, L., Jordan, J.-A., McCann, M., O'Neill, T., Clarke, M., O'Neill, T., Kelly, G., & Campbell, A. (2021). New psychoactives within polydrug use trajectories – Evidence from a mixed-method longitudinal study. Addiction, 116(9), 2454–2462. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15422

- Hiles, D., & Čermák, I. (2013). Narrative psychology. In C. Willig & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research psychology (pp. 146–162). SAGE Publications.

- Jacob, S., Munro, I., Taylor, B. J., & Griffiths, D. (2017). Mental health recovery: A review of the peer-reviewed published literature. Collegian, 24(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2015.08.001

- James, W. (1902/1982). The varieties of religious experience. Penguin Books.

- Kaló, Z., & Felvinczi, K. (2017). Szakértői dilemmák és az ÚPSZ-használat észlelt mintázatai. In K. Felvinczi (Ed.), Változó képletek. ÚJ(abb) szerek: Kihívások, mintázatok (pp. 103–125). L’Harmattan.

- Kaskutas, L. A., Borkman, T. J., Laudet, A., Ritter, L. A., Witbrodt, J., Subbaraman, M. S., Stunz, A., & Bond, J. (2014). Elements that define recovery: The experiential perspective. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(6), 999–1010. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2014.75.999

- Kassai, S., Pintér, J. N., Rácz, J., Erdősi, D., Milibák, R., & Gyarmathy, V. A. (2017). Using interpretative phenomenological analysis to assess identity formation among users of synthetic cannabinoids. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(5), 1047–1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9733-3

- Kelemen, G., & Erdos, M. B. (2010). Health learning as identity learning in the therapeutic community. Addiktológia, 9(3), 216–225.

- Kiss, D., Horváth, Z., Kassai, S., Gyarmathy, A. V., & Rácz, J. (2022). Folktales of recovery – From addiction to becoming a helper: Deep structures of life stories applying Propp’s theory: A narrative analysis. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 54(4), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2021.1990442

- Laudet, A. B. (2007). What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.014

- Madácsy, J. (2020). Etnográfiai terepmunka az Anonim Alkoholisták magyarországi közösségében. Ethnographia, 131(3), 486–502.

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- McAdams, D. (2007). The Life Story Interview II. Retrieved from https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.northwestern.edu/dist/4/3901/files/2020/11/The-Life-Story-Interview-II-2007.pdf

- McAdams, D. P. (1993). The stories we live by: Personal myths and the making of the self. William Morrow & Co.

- McAuley, A., Yeung, A., Taylor, A., Hutchinson, S. J., Goldberg, D. J., & Munro, A. (2019). Emergence of novel psychoactive substance injecting associated with rapid rise in the population prevalence of hepatitis C virus. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 66, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.008

- McKernan, L. C., Nash, M. R., Gottdiener, W. H., Anderson, S. E., Lambert, W. E., & Carr, E. R. (2015). Further evidence of self-medication: Personality factors influencing drug choice in substance use disorders. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43(2), 243–275. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2015.43.2.243

- Mudry, T., Nepustil, P., & Ness, O. (2019). The relational essence of natural recovery: Natural recovery as relational practice. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0010-x

- Najavits, L. M. (2015). Trauma and substance abuse: A clinician’s guide to treatment. In U. Schnyder & M. Cloitre (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for trauma-related psychological disorders: A practical guide for clinicians (pp. 317–330). Springer International Publishing; Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07109-1_16

- Neicun, J., Yang, J. C., Shih, H., Nadella, P., Van Kessel, R., Negri, A., Czabanowska, K., Brayne, C., & Roman-Urrestarazu, A. (2020). Lifetime prevalence of novel psychoactive substances use among adults in the USA: Sociodemographic, mental health and illicit drug use correlates. Evidence from a population-based survey 2007–2014. PLoS One, 15(10), e0251006. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241056

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2006). Re-storying loss: Fostering growth in the posttraumatic narrative. In L. Calhoun & R. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth. Research and practice (pp. 67–80). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Ogilvie, L., & Carson, J. (2022). Trauma, stages of change and post traumatic growth in addiction: A new synthesis. Journal of Substance Use, 27(2), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2021.1905093

- Pai, A., Suris, A. M., & North, C. S. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behavioral Sciences, 7(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010007

- Pasupathi, M., Billitteri, J., Mansfield, C. D., Wainryb, C., Hanley, G. E., & Taheri, K. (2015). Regulating emotion and identity by narrating harm. Journal of Research in Personality, 58, 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2015.07.003

- Pennebaker, J. W., & Smyth, J. M. (2016). Opening up by writing it down: How expressive writing improves health and eases emotional pain. The Guilford Press.

- Pennebaker, J. W., Mehl, M. R., & Niederhoffer, K. G. (2003). Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 547–577. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041

- Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. The American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102

- Prosser, J. M., & Nelson, L. S. (2012). The toxicology of bath salts: A review of synthetic cathinones. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 8(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-011-0193-z

- Rácz, J., Csák, R., Tóth, K. T., Tóth, E., Rozmán, K., & Gyarmathy, V. A. (2016). Veni, vidi, vici: The appearance and dominance of new psychoactive substances among new participants at the largest needle exchange program in Hungary between 2006 and 2014. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 158, 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.034

- Rennick-Egglestone, S., Ramsay, A., McGranahan, R., Llewellyn-Beardsley, J., Hui, A., Pollock, K., Repper, J., Yeo, C., Ng, F., Roe, J., Gillard, S., Thornicroft, G., Booth, S., & Slade, M. (2019). The impact of mental health recovery narratives on recipients experiencing mental health problems: Qualitative analysis and change model. PLOS One, 14(12), e0226201. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226201

- Rinaldi, R., Bersani, G., Marinelli, E., & Zaami, S. (2020). The rise of new psychoactive substances and psychiatric implications: A wide-ranging, multifaceted challenge that needs far-reaching common legislative strategies. Human Psychopharmacology, 35(3), e2727. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2727

- Rober, P. (2002). Constructive hypothesizing, dialogic understanding and the therapist’s inner conversation: Some ideas about knowing and not knowing in the family therapy session. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28(4), 467–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2002.tb00371.x

- SAMSHA (2012). SAMHSA's working definition of recovery. Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Working-Definition-of-Recovery/PEP12-RECDEF

- Schein, J., Houle, C., Urganus, A., Cloutier, M., Patterson-Lomba, O., Wang, Y., King, S., Levinson, W., Guérin, A., Lefebvre, P., & Davis, L. L. (2021). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States: A systematic literature review. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(12), 2151–2161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.1978417

- Seih, Y. T., Chung, C. K., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2011). Experimental manipulations of perspective taking and perspective switching in expressive writing. Cognition & Emotion, 25(5), 926–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.512123

- Shafi, A., Berry, A. J., Sumnall, H., Wood, D. M., & Tracy, D. K. (2020). New psychoactive substances: A review and updates. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 10, 2045125320967197. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125320967197

- Stelzer, E. M., Atkinson, C., O'Connor, M. F., & Croft, A. (2019). Gender differences in grief narrative construction: A myth or reality? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1688130. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1688130

- Stephenson, G. M., Laszlo, J., Ehmann, B., Lefever, R. M. H., & Lefever, R. (1997). Diaries of significant events: Socio-linguistic correlates of therapeutic outcomes in patients with addiction problems. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 7(5), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1298(199712)7:5<389::AID-CASP434>3.0.CO;2-R

- Stokes, M., Schultz, P., & Alpaslan, A. (2018). Narrating the journey of sustained recovery from substance use disorder. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 13(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-018-0167-0

- Tarragona, M. (2008). Postmodern/poststructuralist therapy. In J. Lebow (Ed.), Twenty-first century psychotherapies: Contemporary approaches to theory and practice (pp. 167–205). Wiley.

- UNODC Early Warning Advisory on New Psychoactive Substances. United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime. (2024). https://www.unodc.org/LSS/Page/NPS

- Van den Brink, W. (2015). Substance use disorders, trauma, and PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 27632. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.27632

- Van Hout, M. C., Benschop, A., Bujalski, M., Dąbrowska, K., Demetrovics, Z., Felvinczi, K., Hearne, E., Henriques, S., Kaló, Z., Kamphausen, G., Korf, D., Silva, J. P., Wieczorek, Ł., & Werse, B. (2018). Health and social problems associated with recent novel psychoactive substance (NPS) use amongst marginalised, nightlife and online users in six European countries. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9824-1

- White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Norton Press.

- Wieczorek, Ł., Dąbrowska, K., & Bujalski, M. (2022). Motives for using new psychoactive substances in three groups of Polish users: Nightlife, marginalised and active on the In. Psychiatria Polska, 56(3), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/131971