Abstract

Women represent approximately half of the refugee population, yet female-specific trauma pre, during, and after the refugee journey impacting post-settlement psychological wellbeing, is rarely explored. This scoping review described sources of evidence, key concepts, and gaps regarding traumatic experiences and the psychological wellbeing of women from refugee backgrounds following traumatic experiences with a particular interest in positive change post-settlement. Inclusion criteria were a) women from refugee backgrounds who experienced traumatic events throughout the refugee journey, and b) reported positive changes in their psychological wellbeing post-settlement. The systematic search strategy identified references from PsycINFO, PubMed, Embase, SCOPUS, and CINAHL databases as well as Google Scholar across 1992–2023. Ten studies were extracted, and data were mapped to study characteristics, trauma characteristics, psychological wellbeing domains, and recommendations for further studies. Findings described an emphasis on qualitative methods, utilizing interviews as a data collection technique, and recruiting participants from countries of origin or host countries with typically small populations of women from refugee backgrounds. It excluded individuals with disabilities. Traumatic experiences were signified as trauma types (refugee trauma and female-specific trauma) and trauma durations (acute trauma and prolonged trauma). Psychological wellbeing domains of autonomy, personal growth, and positive relations were the most represented, and purpose in life and self-acceptance were the least represented across the studies. Studies suggested further exploration of female-specific refugee trauma and its impacts to provide tailored support services. In conclusion, there was a paucity of studies that considered the psychological implications of experiencing female-specific refugee trauma influencing positive psychological wellbeing.

Introduction

The mental health of women refugees is largely neglected in the refugee literature yet approximately half the refugee population globally are women (UNHCR-women, Citation2021). Female-specific traumatic events in conflict-affected regions around the globe are particularly challenging for women (Stark et al., Citation2010). Many are known to persist in post-conflict settings (Hynes & Cardozo, Citation2000; Pavlish & Ho, Citation2009). It is possible that multiple traumatic events pre-dated a women’s refugee status through civil unrest, patriarchy, and adverse childhood events.

The term “traumatic events” has generally been used interchangeably for events constituted as abuse, violence, loss, war, neglect, disaster, and other harmful and stressful incidents, and embodies a multitude of concepts. Gender often plays a part in the type of traumatic threat (Olff, Citation2017). Women suffer and state more interpersonal incidents and sexual assaults than men (Gavranidou & Rosner, Citation2003). Moreover, time, proximity, event intensity, duration, and complexity of the experience of traumatic events impact individuals differently, specifically women, older individuals, and individuals with disabilities (Shannon et al., Citation2015; Shiel, Citation2016).

The majority of women within refugee communities come from male-dominant societies (Bertolt, Citation2018; Burbano, Citation2016; Moghadam, Citation2004) where institutional patriarchy culturally, traditionally, and legally, forces them into gender-based roles founded on dependency and obedience (Moghadam, Citation1992) and multiple forms of violence (Pinehas et al., Citation2016). Negative gender bias and dehumanizing behavior toward women are defined as gender minimization (McCormack & Bennett, Citation2021), which perpetuates dominance over basic rights, including women’s bodies, what they wear, and choice of life trajectories and careers (Sen et al., Citation2007). It is often associated with early and forced marriage and genital mutilation (Hurley, Citation2013). Accordingly, women and girls report being raped and sexually harassed within their own country as well as in refugee camps (Scruggs, Citation2004).

In the transition from their country of origin and post-settlement, women can experience bias and discrimination and are often devalued and excluded through race or color (Kang & Kaplan, Citation2019). These events include intimate partner violence (Hynes & Cardozo, Citation2000; Rasmussen, Citation2007), physical and nonphysical violence including financial abuse, prohibited education, and controlled social connections within their family units (El-Arab & Sagbakken, Citation2019; Hossain et al., Citation2020; Mršević & Hughes, Citation1997; Pan et al., Citation2006) or the community and society (Al-Natour et al., Citation2019; Hossain et al., Citation2020; Miller et al., Citation2007; Ruth et al., Citation2018). For many women from refugee backgrounds, in seeking safety post-settlement, the risk of poly-victimisation (Finkelhor et al., Citation2009) precipitates risk behaviors and inhibits the capacity to protect oneself. The longevity of traumatic distress, risks susceptibility to chronic mental ill-health (Bowers, Citation2009).

Scholars agree that the impact of traumatic events is governed by an individual’s perception or meaning making of the event moderated by personality traits and other social factors, including positive social support (Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1980, Citation1985, Citation1988; Joseph & Williams, Citation2005; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Joseph and Linley (Citation2005) articulated three possible outcomes from the struggle to cognitively and emotionally process after trauma. First, they recognized that some individuals negatively accommodate traumatic events resulting in psychopathology i.e., anxiety, depression, posttrauma stress, and psychosomatic complications (Joseph & Linley, Citation2005; van der Kolk et al., Citation1996). Second, in attempting to remain unchanged or bounce back to their pre-trauma state, some assimilate rather than accommodate maintaining intrusion and avoidance as coping mechanisms leaving them vulnerable to future distress (see McCormack & Riley, Citation2016). For some time, these practices may boost a sense of resilience. Third, those who use cognitive-emotional processing to incorporate the trauma narrative into their overall life story, positively accommodate adaptively for psychological wellbeing (Joseph & Linley, Citation2005). This does not mean lives are without distress, but that posttrauma distress is a motivator for positive change (McCormack & Adams, Citation2016).

Acknowledging that individuals seek meaning and find purpose in the face of suffering primarily stated by Kegan (Citation1980), the literature has moved from focusing on how to manage pathological symptoms to the processes for expediting positive change (see Creamer et al., Citation1992; Horowitz, Citation1982, Citation1986; Janoff-Bulman, Citation1992, Citation2006; Joseph et al., Citation1997; Joseph & Linley, Citation2005; Rachman, Citation1980; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004). Ryff and Keyes (Citation1995) suggest that psychological wellbeing (PWB), rather than subjective wellbeing or hedonism (SWB), as the representation of positive transformation, is acquired through autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. Joseph and Linley (Citation2005) also defined posttrauma growth as a normative affective-cognitive process that results in reconstructing a sense of self, relationship with others, and life philosophy. They denoted PWB dimensions are aligned with the three distinct dimensions of posttrauma growth: “Changes in the sense of self (PWB: environmental mastery, personal growth, self-acceptance), changes in relationships with others (PWB: positive relations with others), changes in life philosophy (PWB; purpose in life, autonomy)” (Joseph & Linley, Citation2008, p. 11).

Interest in women from refugee backgrounds and their PWB following trauma, like many other traumatic contexts, has predominantly focused on the clinical approach to provide treatments for mental disorders associated with pre-migration and transition trauma (Lindert & Levav, Citation2015). Although this particular perspective serves these women who suffer from the consequences of traumatic events, it also constricts attention based on Western models, forming a perspective in which psychosocial functioning is purely observed as the absence of mental disorders rather than positive changes in psychological wellbeing. One of the key consequences of such a focus is the amplified stigma of women from refugee backgrounds as victims, disregarding other psychosocial needs critical to their psychological wellbeing (El-Arab & Sagbakken, Citation2019; Mršević & Hughes, Citation1997; Pan et al., Citation2006). Therefore, without a holistic understanding of women from refugee backgrounds and their unique journeys inclusive of gender-specific traumatic events, facilitating and supporting their post-trauma potential for psychological wellbeing and possible growth is limited.

A preliminary search for existing scoping reviews up to this date per the JBI Manual (see Peters et al., Citation2020, p. 416) indicated no scoping review has been conducted on this topic across PsycINFO, MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, SCOPUS, CINAHL, and Google Scholar. Therefore, this scoping review aims to locate and map existing peer-reviewed and grey quantitative and qualitative literature regarding women from refugee backgrounds’ (as participants) traumatic experiences pre-, during- and post-statelessness (as a concept) with a particular interest in positive changes in their psychological wellbeing post-settlement (as the context).

Methods

The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018) and the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Peters et al., Citation2020) guided this scoping review. Consequently, according to the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual (see p. 413), an a priori protocol was published with full details on objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, search strategy, rationale, and procedure before undertaking this scoping review (see Taheri et al., Citation2022) to confirm transparency. As reported previously, this scoping review presented a descriptive report of the reviewed material deprived of analytically assessing individual studies or integrating evidence from different research to answer a question in detail (Brien et al., Citation2010). Consequently, no bias is involved, and the quality assessment and critical appraisal of the risk of biases are not required (Peters et al., Citation2020). The JBI Manual (see Peters et al., Citation2020), consistent with PRISMA Extension standards (see Tricco et al., Citation2018), offers a checklist for authors to check whether the scoping review conforms to their reporting standards. The filled checklist is shown in the supplementary online material Appendix A.

Identifying relevant studies

Positive changes in an individual’s life as a consequence of adversities began appearing in the trauma literature during the early to mid-1990s. Consequently, this scoping review identified quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies published in peer-reviewed journals and grey literature in the past three decades (1992–2023). Per the JBI Manual (see Peters et al., Citation2020, p. 418), the leading search was done by a librarian and peer-reviewed by another librarian for relevant studies from five databases: PsycINFO, PubMed, Embase, SCOPUS, and CINAHL as well as Google Scholar for acceptable grey literature. Then, the authors moved the relevant studies they extracted to EndNote and Covidence.

This Scoping review aimed to explore the impacts of gender-specific traumatic events on the psychological wellbeing of women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement. Therefore, the search strategy consisted of three basic constructs: “women refugees” as participants, “gender-specific traumatic events” as a concept and “psychological wellbeing” as the context. The search strategy was the combination of 3 constructs, including a comprehensive list of synonyms of each construct. The authors and librarian utilized a similar Boolean search with truncations and wildcards to extract relevant studies. However, the search string was adapted for each databases’ search engine configurations. Google Scholar was the main source of grey literature, and the combination of three main constructs was used to identify relevant literature. The search was carried out in November 2023. Two filters were initially applied, including non-human studies and 1992–2023. The full-search algorithm is shown in the supplementary online material Appendix B.

Inclusion

As a summary in line with a priori protocol, the reviewers included references in the screening process if:

As a population, women were from the background of forced or involuntary displacement; and as a concept, gender-specific traumatic events sought the type and severity of traumatic events experienced by women from refugee backgrounds pre-, during-, and post-migration; and as a context, references covered psychological wellbeing or positive changes or posttrauma growth, involving self-acceptance, environmental mastery, personal growth, autonomy, positive relations with others, and a purpose in life, during the post-settlement stage.

Exclusion

The reviewers excluded references: A) if they solely focused on voluntary migration or refugee-like status; or B) if they did not singly report on the positive impacts of gender-specific traumatic events on psychological wellbeing and its dimensions; or C) if they did not analyze and report findings about adult women from refugee backgrounds, separately; or D) if they did not report positive changes in psychological wellbeing during the post-settlement, or E) if they only focused on subjective wellbeing or resilience or psychopathology.

Two other exclusion criteria were applied in the full-text screening phase. However, they were not applied in the initial database searches as well as the titles and abstracts screening section. References were excluded: A) if the full text was not available during the screening and data analysis process, or B) if the full text was not available in the English language or was not translated into English.

Screening process

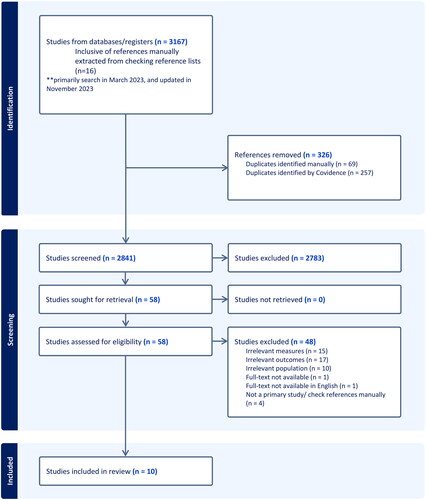

The Authors used Endnote to export 3167 identified references to Covidence. Covidence automatically removed 326 duplicates, and 2841 studies were moved to the titles and abstracts screening section. Per the JBI Manual (see Peters et al., Citation2020, p. 419), in a pilot screening, two reviewers screened 25 randomly chosen studies separately for quality and consistency in screening and finally, the reviewers achieved more than 75% agreement with the screening process criteria before commencing the screening process.

After screening the title and abstracts of references, 58 references were moved to the full-text screening section in Covidence. The reviewers did the full-text screening based on exclusion and inclusion criteria, and 48 full-text studies were excluded based on irrelevant populations, outcomes, and measures as well as unavailable full texts and secondary studies. Ten references did not cover adult women from refugee backgrounds. Seventeen references did not report on positive changes in psychological wellbeing impacted by gender-specific traumatic events. Fifteen references did not include gender-specific traumatic events as a measure. Four references were excluded as they were secondary sources. Per the JBI Manual (see Peters et al., Citation2020, p. 418), reviewers initially added these references to full-text screening to manually check their reference list. One reference was not available as full text. The last one was excluded as the full text was unavailable in English. Based on the JBI Manual (see Peters et al., Citation2020, p. 419), the reviewers resolved conflicts by consensus in different stages throughout the screening process. Finally, 10 studies were accepted for data extraction and data analysis. The screening process as a PRISMA flow diagram is shown in .

Variation from the scoping review protocol

This scoping review followed the published a priori protocol (see Taheri et al., Citation2022). However, a few variations were present due to the iterative nature of a scoping review (Peters et al., Citation2020) and, per JBI Manual (see Peters et al., Citation2020, p. 413), any deviations from the protocol explained in this scoping review. Open Gray was noted as one of the sources of grey literature in the published scoping review protocol. However, access to Open Gray was denied; therefore, based on the Authors’ agreement and the librarian’s advice, Google Scholar output was doubled to cover more relevant references in this scoping review. Four exclusion criteria were introduced in the protocol. However, exclusion criteria E was added to exclude references if they focused only on subjective wellbeing or resilience or psychopathology in order to refine the screening process. The authors also suggested Nvivo as software for data analysis in the scoping review protocol, as a large number of references was anticipated. However, manual data extraction and charting occurred in the current scoping review due to the few extracted references. Lastly, to practice inclusion within this scoping review, women refugees, as a term used for participants across the priori protocol, were replaced by women from refugee backgrounds or women within refugee contexts across the current scoping review.

Data charting and analysis of the evidence

In the data charting process, the reviewers manually and independently extracted key data from each included study individually, using the introduced data extraction table in the scoping review protocol. Charting data is an iterative process to extract key data from included studies (Levac et al., Citation2010). All the key data covered author, year, title—study type—country of origin—country of study—the study aims, objectives or purpose—population (including age and sample size)—method—measures—gender-specific traumatic events- trauma (including trauma types and period)—outcome(s): post-trauma psychological wellbeing—results: quantitative or qualitative or mixed-methods and recommendations for future studies.

The authors performed a descriptive qualitative content analysis for PWB domains, including basic coding of data and due to the nature of scoping reviews, findings were reported descriptively rather than analytically (see JBI Manual p. 421). A summary of data coded to PWB domains introduced by Ryff and Keyes (Citation1995) was mapped based on Joseph and Linley’s (Citation2005) posttrauma growth domains. In the final meeting, the reviewers discussed and cross-checked the analysis and agreed upon the extracted data, and it became apparent that an additional unforeseen data as meaning making merged, which was additionally charted (see JBI Manual p. 420). Microsoft Excel was used to map data to report a descriptive narrative that included gender-specific traumatic events pre-, during-, and post-migration and their impact on positive changes in the psychological wellbeing of women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement. Data charting of included studies is shown in .

Table 1. Data charting of included studies.

Results

Studies characteristics

Ten studies were found to explore traumatic events experienced by women from refugee backgrounds pre-, during-, and after the refugee journey with a particular interest in positive changes in their psychological wellbeing post-settlement over the past 3 decades.

One study was conducted between 1992 and 2002, one between 2002 and 2012, and 8 studies (80%) were carried out between 2012 and 2023. All 10 studies were conducted in the host countries. Four of them were carried out in North America (the USA and Canada), three of them in Europe (Sweden, Netherlands, and Germany), two of them in Asia or the Middle East (Turkey and Jordan), and one was conducted in Australia. Two hundred and forty-one participants were recruited across all 10 studies, and the participants came from eleven countries, predominantly from the Syrian Arab Republic. Thirty-eight participants were from Africa (Somalia, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Libya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Rwanda), 184 participants were from the Middle East (the Syrian Arab Republic and Iraq), and 19 participants were from Asia (Cambodia and Afghanistan). No large sample size study (> 10% of the population) was available. The age range of the participants was reported as either older than 18 or between 18 years old and 75 years old, and no study covered women from refugee backgrounds with disabilities.

Nine out of 10 studies used purposive sampling, including 2 snowball sampling methods, and only one of them utilized random sampling as the study was carried out through in-depth interviews during a program conducted by a volunteer psychologist with Yezidi women refugees (Erdener, Citation2017). Except for one observational study, all others were qualitative, including 4 case studies, 3 field case studies, and 2 interventions. There was no mixed method or longitudinal study. For data collection techniques, 7 of the studies utilized formal, informal, and semi-structured formatted interviews, 1 study collected data through oral history or shared narratives, 1 study utilized a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire, and the last study was a case illustration. No study was found using a self-report questionnaire or survey method (see ).

Table 2. Summary of included study characteristics (n = 10 for studies and n = 241 for samples).

Trauma characteristics

Two superordinate trauma characteristics, trauma types and trauma durations, were extracted in this scoping review to map out gender-specific traumatic events experienced by women from refugee backgrounds. First, trauma types were inclusive of two sub-groups: “Refugee trauma” occurring to women during their time as refugees, and “female-specific trauma” occurring to refugees as a result of being a woman in the refugee context. Second, trauma duration was inclusive of two sub-groups: “Acute trauma” referring to traumatic events that occurred in a limited period of the women refugees’ journey, and “prolonged or continuous trauma” referring to traumatic events that reoccurred to women throughout the refugee journey and post-settlement (see ).

Table 3. Summary of trauma characteristics.

Women in refugee contexts experienced “refugee trauma” inclusive of war or armed conflict, persecution, betrayal, genocide rape, psychological distress, robbery, torture, massacre or genocide, loss or death, forced relocation challenges (separation from family, prohibition of religious and cultural practices, marginalization, uncertainty about future, language barriers), and starvation. All indicated refugee traumas, exclusive of persecution and loss or death, were reported in the pre-and during-migration phases. Women refugees experienced “female-specific trauma” inclusive of domestic violence, forced marriage, rape or assault or sexual violence or sexual trauma, physical violence, gender-based oppression or social exclusion or stigmatization or violence, and human trafficking or kidnapping. These traumas, excluding forced marriage and human trafficking or kidnapping, were reported across all phases of the refugee journey. One study reported no female-specific trauma.

“Acute trauma” highlighted by included studies were war and armed conflict, persecution, forced marriage, massacre, betrayal, genocide rape, psychological distress, torture, human trafficking or kidnapping, loss or death, forced relocation and separation from family, prohibition of religious and cultural practices, starvation, genocide, and sexual violence. One study reported no acute trauma type. “Prolonged trauma” referred by included studies were domestic violence, psychological distress and forced relocation challenges (separation from family, prohibition of religious and cultural practices, marginalization, uncertainty about future, language barriers), persecution, physical violence, robbery, sexual violence or assault or sexual trauma or rape, loss or death, gender-based oppression or social exclusion or stigmatization as prolonged trauma.

Sexual violence, loss or death, persecution, psychological distress, and rape were noted both as acute and prolonged trauma. All female-specific trauma except forced marriage, gender-based violence (which occurred explicitly at the borders), human trafficking, and kidnapping were prolonged traumas. One study reported no prolonged trauma.

Psychological wellbeing domains post-settlement

This scoping review focused on the reported post-settlement positive changes in the psychological wellbeing of women from refugee backgrounds who experienced traumatic events throughout the refugee journey. As noted by Joseph and Linley (Citation2005), psychological wellbeing dimensions are aligned with the three distinct dimensions of posttrauma growth: Changes in the sense of self (PWB: environmental mastery, personal growth, self-acceptance), changes in relationships with others (PWB: positive relations with others), changes in life philosophy (PWB; purpose in life, autonomy). Therefore, results were mapped accordingly.

In general, 3 studies used “Posttrauma growth” as a distinct term connected to positive changes in the psychological wellbeing of women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement. Those studies added a few more factors that facilitate positive changes in the posttrauma psychological wellbeing of women within refugee contexts. Spiritual elements were documented to have a positive correlation with posttrauma growth. Spiritual elements enhanced the strength of women to use personal inner capabilities while trusting in God and moving forward (Byrskog et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, reconstructed trauma narratives assisted one woman from a refugee background to disclose and share her traumatic experiences. This process was expressed as posttrauma growth inclusive of “increased compassion and empathy for herself and others, greater emotional maturity, a greater appreciation for life, a deeper purpose and meaning in life, and a deeper spiritual focus that values family and community” (Uy & Okubo, Citation2018, p. 232). Lastly, in a study conducted by Kheirallah et al. (Citation2022), the diversity of positive transformation post-exposure to traumatic experiences in various degrees was documented, including moderate-to-high levels as well as low positive transformation and growth.

Among all PWB domains, autonomy, personal growth, and positive relationships were the most stated, with five reports in the included studies. Purpose in life and self-acceptance were the least stated PWB domains, with two reports in the included studies (see ).

Table 4. Summary of reported psychological wellbeing domains, posttrauma growth and meaning making post-settlement.

Changes in the sense of self

According to Joseph and Linley (Citation2008), environmental mastery, personal growth, and self-acceptance as PWB domains are congruent with changes in the sense of self as a posttrauma growth domain.

Environmental mastery

Findings relevant to “Environmental mastery” as the capacity to manage effectively one’s life and the surrounding world (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995) were reported in 3 studies. After years of post-settlement and becoming familiar with the host society’s rules and regulations, some women from refugee backgrounds reported environmental mastery relevant to the health care system benefits in the host country. They appreciated the available and accessible “free, advanced public healthcare system … the system is committed to providing follow-up and screening” (Al-Hamad et al., Citation2022, p. 1029). Some others valued the new environment as it assisted them to “achieve peace and safety” (Carmody et al., Citation2021, p. 491), while the “environment shaped by rules” (Raboi, Citation2021, p. 94). Available stability and accessible, equal opportunities in the new environment, as other highlighted factors, were emphasized by a divorced woman who “had been able to send her daughters to school and had given them a stable environment” (Raboi, Citation2021, p. 124).

Personal growth

Findings relevant to “Personal growth” as a sense of continued growth and development as a person (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995) were reported in 5 studies. Some women from refugee backgrounds reported personal growth through gaining perspective. They mentioned that living in and fleeing from their country of origin was devastating, but they were aware of not dwelling on what could not be changed. As a result, women from refugee backgrounds reported getting progressively more active in public life, running small businesses, and assisting other women with their children. One of these women summarized all points: “We got strength from all the difficulties we have been through during the war. Everything we went through gave us strength and made us heroic” (Byrskog et al., Citation2014, p. 7). Women from refugee backgrounds denoted that they took pride in themselves and their achievements (Herbst, Citation1992). Some women who participated in a study emphasized that “migration-related struggles coupled with being Syrian refugee women” had contributed to “their personal growth such as learning new things and becoming a different and responsible person” (Al-Hamad et al., Citation2022, p. 1028). Being “given a voice” as well as feeling “welcome” post-settlement were stated factors in fostering personal growth (Al-Hamad et al., Citation2022, p. 1028).

Women from refugee backgrounds also reported personal growth through rebuilding a sense of trust with others. Yezidi women refugees were suspicious regarding family planning offered by the medical team as their lineage was threatened by genocide, and they could not risk having fewer children. However, after approximately six months, most Yezidi women refugees, particularly new mothers and women with many children, came to the medical site to ask for birth control. They sought to help themselves as the initial burden of having and raising more children was traditionally a woman’s responsibility (Erdener, Citation2017).

Self-acceptance

Findings from two studies mapped the “Self-acceptance” outcome as positive evaluations of oneself and one’s past life (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). Women from refugee backgrounds described recognizing their own distancing technique through acceptance of their emotions in the recovery process. They even came to the opinion that they survived because of personal strength. One refugee woman noted, “I survived because I guess I had a strong heart” (Herbst, Citation1992, p. 153). These women separated their traumatic experiences from their sense of dignity and integrity. For example, even though one of these participants reported being raped, and regarding that as a very shameful taboo, she stated that she did not feel guilty (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007).

Changes in relationships with others

According to Joseph and Linley (Citation2008), positive relations with others as PWB domains are congruent with changes in relationships with others as a posttrauma growth domain.

Positive relations with others

Findings from 5 studies mapped “Positive relations with others” outcome as the possession of quality relations with others (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). Women from refugee backgrounds reconnected and established a sense of support within their community through the mourning rituals they practised together. Therefore, day by day, they became an important part of each other’s healing by sharing their loss’s unspoken pain (Erdener, Citation2017). Having a social group was significantly important for these women who lacked emotional support and protection from their own families or relatives (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007). For instance, single mothers found it easier to build and maintain “relationships with other single mothers” within the community or others beyond their community (Carmody et al., Citation2021, pp. 491–492).

Women from refugee backgrounds established connections through empathy as well. Acceptance, compassion, and recognizing they were not alone helped them become instantly available to assist each other (Herbst, Citation1992). They connected to their therapist through a sense of equality, which was empowering to the whole group (Herbst, Citation1992). They also recognized social support from friends (Kheirallah et al., Citation2022, p. 1247) and family, particularly having children, as sources of comfort as these factors could “alleviate the sense of loneliness and pain of separation from immediate family left behind” (Carmody et al., Citation2021, p. 493).

Changes in life philosophy

According to Joseph and Linley (Citation2008), autonomy and purpose in life as PWB domains are congruent with changes in life philosophy as a posttrauma growth domain.

Autonomy

Five studies reported findings on the “Autonomy” outcome as a sense of self-determination (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). Women from refugee backgrounds were able to regulate their emotions as feeling stronger due to “having voices and freedom to speak” (Al-Hamad et al., Citation2022, p. 1028). In addition to psychological strength and control of their fate, learning self-defense, even though they still believed in religious pacifism, was an exercise of physical strength and control. One refugee woman said: “Look at these results! Gangs slaughtered thousands of us like sheep, but we could not kill even one of them! What a shame! Next time, we will have to be ready too!” (Erdener, Citation2017, p. 67). They also described how they were proud of themselves (Erdener, Citation2017) to be able to survive. Moreover, these women were eager to use the education provided, including relaxation techniques and English courses, as a source of personal power in their community (Herbst, Citation1992).

Women from refugee backgrounds demonstrated interest in seeking help and asking for birth control without the knowledge of their partners (Erdener, Citation2017). One of the participants explained, “It was difficult for me to obey my husband. I often disagreed with him, which led to a lot of tension; my husband wanted to continue with the old roles, but I didn’t want to be sent back to the kitchen” (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007, p. 196). As a result of the improved sense of autonomy in women from refugee backgrounds, some men were afraid of losing their authority, so they did not let women refugees seek help or work (Erdener, Citation2017). A few participants reported they were able to seek assistance and further their development after divorce; for example, joining language proficiency classes (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007), residing in a domestic violence transitional housing program, and beginning to advocate for themselves and other genocide survivors (Uy & Okubo, Citation2018).

Purpose in life

Two studies reported findings within the “Purpose of life” outcome as the belief that one’s life is purposeful and meaningful (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). Some women from refugee backgrounds denoted that despite the responsibility they have toward their children, they give their mothers hope to move forward and not give up. For instance, Ajak said, “I wanted to kill myself but couldn’t do it because of my children. I had to take care of my children, although I could cry the whole day” (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007, p. 194). Some women from refugee backgrounds ran small businesses and were appreciated as central to keeping their own and family lives together. These women expressed that their strength to move forward was refined by the prolonged war and armed conflicts (Byrskog et al., Citation2014).

Meaning making and positive changes in PWB

Meaning making and positive changes in the psychological wellbeing of women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement were mentioned in 9 studies. Raboi (Citation2021) was the only study that did not mention meaning making or posttrauma growth but reported positive changes in PWB domain.

Meaning making through spirituality was denoted in various forms. A participant stated a good example of multifaced understanding. She said, “You shouldn’t just say, I can’t manage, … When we grew up, we didn’t hear those words “You never manage this.” I have never heard this from my parents, other parents, the Quran-school. So, the culture gives very much, that we look forward only, that I can make this” (Byrskog et al., Citation2014, p. 8). Deeply rooted religious beliefs practised by the family were the source of strength and ability for women from refugee backgrounds to manage the situations (Smigelsky et al., Citation2017). Similarly, other participants denoted a “better understanding of spiritual matters and having stronger religious beliefs” (Kheirallah et al., Citation2022, p. 1258). Therefore, “belief in God provided meaning to the lives of participants as well as a mechanism to regain control over their future” (Carmody et al., Citation2021, p. 494), similar to Tankink and Richters’s (Citation2007) study.

Another group of women from refugee backgrounds reported making meaning through a sense of gratitude. A statement was used by almost every woman in a study that indicated the significance of physical health and survival throughout the refugee journey for women and their significant others. They said: “We were saved, Hallelujah, we are grateful to be alive. Nothing happened to me and my children” (Erdener, Citation2017, p. 66). Studies reported that gradually rising hope and future plans were evident based on their gratitude for surviving. Some studies noted meaning making through giving back to the community (Herbst, Citation1992; Al-Hamad et al., Citation2022). For example, those who survived openly talked about their trauma to educate others to prevent the recurrence of further issues. Furthermore, some of these women made meaning by gaining a new perspective. Reconstructing trauma narratives and making sense of how social position influenced the recovery process assisted women from refugee backgrounds (Uy & Okubo, Citation2018).

Recommendations of authors on further studies

Ten extracted studies were included in this scoping review, but only 9 recommended several areas for further research or for improving the current circumstances of women from refugee backgrounds.

First, there is a need to explore aspects of refugee experiences and their contributions in meaning making (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007), taking both psychological context and social contexts into account to determine tailored interventions and processes for women’s mental health care within refugee contexts (Smigelsky et al., Citation2017; Al-Hamad et al., Citation2022). Second, investigating post-settlement experiences (e.g., social networks) is essential which can enhance these women’s psychological wellbeing (Byrskog et al., Citation2014), for instance, providing supporting programs inclusive of language proficiency training in host countries (Herbst, Citation1992). Third, examining the integration of an eco-social framework within resettlement programs, refocusing on the psycho-social-spiritual factors specific to women within refugee contexts (Carmody et al., Citation2021). Fourth, the intervention’s outcome needs to be employed as a guideline to enhance the psychological wellbeing of women post-settlement (Uy & Okubo, Citation2018). Fifth, future qualitative and case-control studies with a larger and more representative sample are needed to comprehensively evaluate the effects of trauma experience and positive impacts on psychological wellbeing (Kheirallah et al., Citation2022). Last, Erdener (Citation2017) recognized that further research is needed as a cliché and suggested utilizing available approaches to raise the world’s awareness of women’s hardships within refugee contexts.

Discussion

This scoping review is the first known review to map the literature concerning gender-specific traumatic events and posttrauma psychological wellbeing in women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement. However, due to the nature of this review as a scoping review, no rating of the quality of evidence is provided. As a result, implications for practice or policy can only be described, not graded (see JBI Manual, p. 441). Despite the reported growth in the number of conducted studies over the last three decades, there is still a paucity of studies in this area as the number of refugees has risen exponentially over the last decade (UNHCR, Citation2022).

UNHCR reported more than 36% of refugees are hosted in 5 countries: Turkey, Colombia, Germany, Pakistan, and Uganda. However, Turkey and Germany were the only countries from the top host countries that conducted two studies in this area, with no studies conducted in the other three countries. The top 5 countries producing refugees are the Syrian Arab Republic, Venezuela, Ukraine, Afghanistan, and South Sudan (UNHCR, Citation2022). The Syrian Arab Republic, Afghanistan, and South Sudan were the only countries represented, with no participant representing the other two countries on this topic. Age and disabilities, along with gender, were referred to as the key enablers of abuse in women (Shannon et al., Citation2015; Shiel, Citation2016). There was a general paucity of knowledge and gaps in studies specific to women from refugee backgrounds from and within different contexts, inclusive of older individuals, individuals who return back to their country of origin, and those with disabilities. Consequently, more studies concerning female-specific refugee traumatic events’ impact on the development of psychological wellbeing factors for positive change in women from different cultural, racial, and geographical backgrounds in different host countries (inclusive of elders and women with disabilities) are required.

Positive change following traumatic events contributing to psychological wellbeing, more commonly known as posttrauma growth, refers to both a process and an outcome (Joseph & Linley, Citation2005; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004). Despite qualitative studies providing deep insights into idiographic positive changes in participants following traumatic exposure, findings cannot be generalized across women from refugee communities (Carminati, Citation2018). Therefore, large sample size research and self-report questionnaires are required to meet the criteria for generalizability of findings across this population, which is consistent with recommendations for further studies by Kheirallah et al. (Citation2022). Similarly, future longitudinal studies contribute to a more profound understanding of the development and progress of positive changes in PWB and growth of women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement over time.

Within the included studies, participants experienced traumatic events both as refugees and as women. Therefore, this study represented female-specific refugee trauma. “Refugee traumas” (e.g., robbery, forced relocation) were well aligned with the refugee definition of the 1951 Refugee Convention (UNHCR, 2022). However, “female-specific trauma” targeted women throughout the journey even post-settlement (Hynes & Cardozo, Citation2000; Pavlish & Ho, Citation2009) and they suffered from imposed violence either by strangers or family members (Al-Natour et al., Citation2019; El-Arab & Sagbakken, Citation2019; Hossain et al., Citation2020; Miller et al., Citation2007; Mršević & Hughes, Citation1997; Pan et al., Citation2006; Ruth et al., Citation2018). Unfortunately, there is no current gender-specified definition of refugee. In this scoping review, all female-specific traumatic events, except forced marriage, violence (at the borders), human trafficking, and kidnapping, were expressed as prolonged traumas. Therefore, there is a probable relation between female-specific traumatic events and trauma duration yet to be explored.

The lack of a clear definition of trauma, trauma types, duration, and female-specific refugee traumatic events might lead to poor understanding from both practitioners and women from refugee backgrounds. Erdener (Citation2017) stated that researchers avoided trauma classification, fearing that talking about previous traumatic events could re-traumatise the participants. However, participants in other studies agreed that verbalizing the event and sharing their trauma narratives with others assisted their recovery process (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007). Consequently, specific studies that cover every phase of women refugees’ journeys, inclusive of the female-specific traumatic event (acute or prolonged) and its impacts on psychological wellbeing post-resettlement, are long overdue.

Positive changes in PWB domains (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995) are interconnected with the posttrauma growth domains articulated by Joseph and Linley (Citation2005). They believe these changes occur through stimulating an individual’s cognitive appraisal to rebuild their sense of self, relationships with others, and life philosophy. In this scoping review, all included studies stated positive changes in the PWB of women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement, which were aligned with Ryff and Keyes’s (Citation1995) PWB domains. However, only three of these studies (Byrskog et al., Citation2014; Kheirallah et al., Citation2022; Uy & Okubo, Citation2018) directly mentioned posttrauma growth as a distinct term within their studies. Self-acceptance and purpose in life were the least reported PWB domains across studies, which indicated further research and interventions are required to develop these two PWB domains or examine if these domains are interrelated in order to foster more significant positive changes in women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement.

Meaning making was vastly used within included studies but one. Thus, meaning making appears to play a significant role in facilitating or promoting positive changes in the psychological wellbeing of women from refugee backgrounds post-settlement. It did not appear to facilitate self-acceptance and purpose in life. Similarly, regarding the importance of meaning, defining, and recognizing women from refugee backgrounds as survivors of traumatic events with the capacity to move forward and possible growth may avoid further stigmatization of individuals as victims struggling with mental ill-health. Researchers and clinicians should include language that will be considered inclusive by using “women from refugee backgrounds” terminology instead of “refugee women” or “women refugees” as a person is more than the label of refugee (see JBI Manual, p. 418).

Further studies highlighted the need to explore refugee experiences holistically (Byrskog et al., Citation2014), including meaning making (Tankink & Richters, Citation2007). The importance of taking different aspects of psych-social-spiritual factors specific to women (Carmody et al., Citation2021) into account to determine tailored supporting programs (Herbst, Citation1992), and interventions for mental health care of women from refugee backgrounds (Smigelsky et al., Citation2017; Al-Hamad et al., Citation2022) were signified as gaps of studies. Utilizing interventions’ outcomes to update guidelines and frameworks (Carmody et al., Citation2021; Uy & Okubo, Citation2018). Similar to Erdener (Citation2017), this scoping review drew attention to the paucity of understanding and knowledge about female-specific refugee trauma and its association with positive changes post-trauma. It is essential to understand that these studies did not undermine the hardships and suffering women have been through throughout the refugee journey and post-settlement but intended to explore their traumatic journey in a holistic manner and shed some light on an area that has been neglected and may provide hope and awareness for supporting potential positive changes and growth.

Strengths and limitations

Shedding light on the potential for female-specific refugee trauma to act as a springboard for recovery and positive psychological change in women from refugee backgrounds and highlighting the paucity of studies in this cohort were the strengths of this scoping review. However, the findings broadly recognized what is presented and missing in the literature rather than contributing answers to a particular question in detail.

Conclusions

This scoping review appears to be the first to identify studies concerning female-specific refugee traumatic events inclusive of mapping multiple traumatic experiences pre-, during-, and after-statelessness. It highlights evidence for their capacity for embracing psychological wellbeing factors for positive change in their lives post-settlement. It included sources of evidence, key concepts, and gaps in the research to inform research and practice. Findings draw attention to the limited insight into the journeys of women from refugee backgrounds, particularly the cultural constraints and potential trauma, prior to engaging in the refugee journey. It offers researchers, clinicians, and policymakers an overview of female-specific refugee traumatic events and psychological wellbeing to inform programs and services specific to women within refugee contexts that will facilitate psychological wellbeing and growth in their new environment.

Implications of the findings for research

This scoping review identified gaps in studies in addition to all mapped recommendations for further studies. Thus, the following is recommended:

studies specific to a) women from different backgrounds; b) within different host countries, and c) female-specific aspects of the refugee journey to redefine the definition of Refugee specific to women,

a comprehensive review of the terminology used to identify, describe, and refer to women from humanitarian backgrounds,

further quantitative and longitudinal studies throughout the refugee journey, including female-specific traumatic events, experiences, and perceptions, and posttrauma positive changes in psychological wellbeing and growth,

further investigation into the role of meaning making across all domains of PWB specific to women within refugee contexts.

Open Scholarship

![]()

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Preregistered through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.29352/mill0218.26621. To obtain the author's disclosure form, please contact the Editor.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (37 KB)Disclosure statement

The first, fourth and fifth authors collaboratively designed the study and published a scoping review protocol. The first author took the lead in this study, supported by the fifth author. The first, second, and third authors screened the title and abstract of references. The third author screened the full-text references and performed formal data analysis with the first author. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. Two librarians guided, reviewed, and ran search strategies within different databases for this scoping review. This research received no grant from any funding agency.

References

- Al-Hamad, A., Forchuk, C., Oudshoorn, A., & Mckinley, G. P. (2022). Listening to the voices of Syrian refugee women in Canada: An ethnographic insight into the journey from trauma to adaptation. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 24, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00991-w

- Al-Natour, A., Al-Ostaz, S. M., & Morris, E. J. (2019). Marital violence during war conflict: The lived experience of Syrian refugee women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing: Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society, 30(1), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659618783842

- Bertolt, B. (2018). Thinking otherwise: Theorising the colonial/modern gender system in Africa. African Sociological Review, 22(1), 2–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90023843

- Bowers, J. (2009). A look at posttraumatic stress disorder’s new possible diagnostic subtype: With psychotic features. The Chicago School of Professional Psychology ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/openview/ecf2c7fc5fbad3bfcbe5451f23bd2598/1?cbl=18750&pq-origsite=gscholar

- Brien, S. E., Lorenzetti, D. L., Lewis, S., Kennedy, J., & Ghali, W. A. (2010). Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implementation Science, 5(1), 2–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-2

- Burbano, E. (2016). The persistence of patriarchy in Latin America: An analysis of negative and positive trends [Honours thesis, Union College]. https://digitalworks.union.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1122&context=theses

- Byrskog, U., Olsson, P., Essén, B., & Allvin, M. K. (2014). Violence and reproductive health preceding flight from war: Accounts from Somali born women in Sweden. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 892. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-892

- Carminati, L. (2018). Generalizability in qualitative research: A tale of two traditions. Qualitative Health Research, 28(13), 2094–2101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318788379

- Carmody, M., Schweitzer, R. D., Vromans, L., & Marca, L. L. (2021). Narratives of women at-risk resettled in Australia: Loss, renewal and connection. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 26(5), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1845069

- Creamer, M., Burgess, P., & Pattison, P. (1992). Reaction to trauma: A cognitive processing model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(3), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.101.3.452

- El-Arab, R., & Sagbakken, M. (2019). Child marriage of female Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon: A literature review. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1585709. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2019.1585709

- Erdener, E. (2017). The ways of coping with post-war trauma of Yezidi refugee women in Turkey. Women’s Studies International Forum, 65, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2017.10.003

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., & Hamby, S. L. (2009). Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics, 124(5), 1411–1423. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-046

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1037/00223514.54.3.466

- Gavranidou, M., & Rosner, R. (2003). The weaker sex? Gender and posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 17(3), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10103

- Herbst, P. K. R. (1992). From helpless victim to empowered survivor: Oral history as a treatment for survivors of torture. In E. Cole, O. M. Espin, & E. D. Rothblum (Eds.), Refugee women and their mental health: Shattered societies, shattered lives (pp. 141–154). Haworth Press.

- Horowitz, M. J. (1982). Psychological processes induced by illness, injury, and loss. In T. Millon, C. Green, & R. Meagher (Eds.), Handbook of clinical health psychology (pp. 53–67). Springer US.

- Horowitz, M. J. (1986). Stress-response syndromes: A review of posttraumatic and adjustment disorders. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 37(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.37.3.241

- Hossain, M., Pearson, R., McAlpine, A., Bacchus, L., Muuo, S. W., Muthuri, S. K., Spangaro, J., Kuper, H., Franchi, G., Pla Cordero, R., Cornish-Spencer, S., Hess, T., Bangha, M., & Izugbara, C. (2020). Disability, violence, and mental health among Somali refugee women in a humanitarian setting. Global Mental Health (Cambridge, England), 7, E30. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2020.23

- Hurley, S. L. (2013). Women’s rights, culture, and conflict implementing gender policy in Amboko Refugee Camp, Chad [Doctoral dissertation, Graduate Program in Environmental Studies, York University].

- Hynes, M., & Cardozo, B. L. (2000). Observations from the CDC: Sexual Violence against Refugee Women. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 9(8), 819–823. https://doi.org/10.1089/152460900750020847

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. Free Press.

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (2006). Schema-change perspectives on posttraumatic growth. In L. G. Calhoun & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research & practice (pp. 81–99). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2005). Positive adjustment to threatening events: An organismic valuing theory of growth through adversity. Review of General Psychology, 9(3), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.262

- Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2008). Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress: An integrative psychosocial framework. In S. Joseph & P. A. Linley (Eds.), Trauma, recovery, and growth: Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress (pp. 1–20). John Wiley & Sons.. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118269718.ch1

- Joseph, S., & Williams, R. (2005). Understanding posttraumatic stress: Theory, reflections, context and future. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(4), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465805002328

- Joseph, S., Dalgleish, T., Williams, R., Yule, W., Thrasher, S., & Hodgkinson, P. (1997). Attitudes towards emotional expression and post-traumatic stress in survivors of the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(1), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01236.x

- Kang, S. K., & Kaplan, S. (2019). Working toward gender diversity and inclusion in medicine: Myths and solutions. Lancet (London, England), 393(10171), 579–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33138-6

- Kegan, R. (1980). Making meaning: The constructive‐ developmental approach to persons and practice. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 58(5), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4918.1980.tb00416.x

- Kheirallah, K. A., Al-Zureikat, S. H., Al-Mistarehi, A. H., Alsulaiman, J. W., AlQudah, M., Khassawneh, A. H., Lorettu, L., Bellizzi, S., Mzayek, F., Elbarazi, I., & Serlin, I. A. (2022). The association of conflict-related trauma with markers of mental health among Syrian refugee women: The role of social support and post-traumatic growth. International Journal of Women’s Health, 14, 1251–1266. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S360465

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-59085-69

- Lindert, J., & Levav, I. (2015). Violence and Mental Health: Its Manifold Faces (2015th ed). Springer Nethetlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8999-8

- McCormack, L., & Adams, E. L. (2016). Therapists, complex trauma, and the medical model: Making meaning of vicarious distress from complex trauma in the inpatient setting. Traumatology, 22(3), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000024

- McCormack, L., & Bennett, N. (2021). Relentless, aggressive and pervasive: Exploring gender minimisation and sexual abuse experienced by women ex-military veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001157

- McCormack, L., & Riley, L. (2016). Medical discharge from the “family,” moral injury, and a diagnosis of PTSD: Is psychological growth possible in the aftermath of policing trauma? Traumatology, 22(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000059

- Miller, E., Decker, M. R., Silverman, J. G., & Raj, A. (2007). Migration, sexual exploitation, and women’s health: A case report from a community health center. Violence against Women, 13(5), 486–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207301614

- Moghadam, V. M. (1992). Patriarchy and the politics of gender in modernising societies: Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. International Sociology, 7(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/026858092007001002

- Moghadam, V. M. (2004). Patriarchy in transition: Women and the changing family in the Middle East. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 35(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.35.2.137

- Mršević, Z., & Hughes, D. M. (1997). Violence against women in Belgrade, Serbia: SOS hotline 1990–1993. Violence against Women, 3(2), 101–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801297003002002

- Olff, M. (2017). Sex and gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder: An update. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup4), 1351204. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1351204

- Pan, A., Daley, S., Rivera, L. M., Williams, K., Lingle, D., & Reznik, V. (2006). Understanding the role of culture in domestic violence: The Ahimsa Project for Safe Families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 8(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-0066340-y

- Pavlish, C., & Ho, A. (2009). Pathway to social justice: Research on human rights and gender-based violence in a Rwandan refugee cAMP. ANS. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 32(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181a3b0c4

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

- Pinehas, L. N., van Wyk, N. C., & Leech, R. (2016). Healthcare needs of displaced women: Osire refugee camp, Namibia. International Nursing Review, 63(1), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12241

- Raboi, S. (2021). Confronting uncertainty: Syrian refugee women in Germany [Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Bayreuth]. https://doi.org/10.15495/EPub_UBT_00006063

- Rachman, S. (1980). Emotional processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 18(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(80)90069-8

- Rasmussen, B. (2007). No refuge: An exploratory survey of nightmares, dreams, and sleep patterns in women dealing with relationship violence. Violence against Women, 13(3), 314–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801206297439

- Ruth, A., Lars, L., & Ingrid, H. (2018). Coping, resilience and posttraumatic growth among Eritrean female refugees living in Norwegian asylum reception centres: A qualitative study. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(4), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018765237

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological wellbeing revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

- Scruggs, N. (2004). International perspectives on family violence and abuse: A cognitive ecological approach (pp. 223–243). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; US.

- Sen, G., Östlin, P., & George, A. (2007). Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report 07.pdf

- Shannon, P. J., Vinson, G. A., Wieling, E., Cook, T., & Letts, J. (2015). Torture, war trauma, and mental health symptoms of newly arrived Karen refugees. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 20(6), 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2014.965971

- Shiel, R. (2016). Identifying and responding to gaps in domestic abuse services for older women. Nursing Older People, 28(6), 22–26. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2016.e815

- Smigelsky, M. A., Gill, A. R., Foshager, D., Aten, J. D., & Im, H. (2017). “My heart is in his hands”: The lived spiritual experiences of Congolese refugee women survivors of sexual violence. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 45(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2016.1197754

- Stark, L., Roberts, L., Wheaton, W., Acham, A., Boothby, N., & Ager, A. (2010). Measuring violence against women amidst war and displacement in northern Uganda using the “neighbourhood method. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 64(12), 1056–1061. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.093799

- Taheri, M., Fitzpatrick, S., & McCormack, L. (2022). The impacts of gender-specific traumatic events on refugee women’s psychological wellbeing: A scoping review protocol. Millenium, 2(18), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.29352/mill0218.26621

- Tankink, M., & Richters, A. (2007). Silence as a coping strategy: The case of refugee women in the Netherlands from South-Sudan who experienced sexual violence in the context of war. In B. Drožđek & J. P. Wilson (Eds.), Voices of trauma. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-69797-0_9

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Target article: “Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- UNHCR-women. (2021). Women. https://www.unhcr.org/women.html

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2022–2023). Refugee statistics. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/globalappeal2021/

- Uy, K. K., & Okubo, Y. (2018). Re-storying the trauma narrative: fostering posttraumatic growth in Cambodian refugee women. Women & Therapy, 41(3–4), 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2018.1425025

- Van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C., & Weisaeth, L. (Eds.). (1996). Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body, and society. The Guilford Press.