Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between suicidality and various mental health problems using longitudinal follow-up data in bereaved families after the Sewol ferry disaster. Data from 226 participants gathered over 7 years (2015–2021) were used. Suicidal risk was measured and mental health variables including depression, insomnia, post-traumatic embitterment disorders(PTED), complicated grief were gathered. A series of Generalized Estimating Equation models were developed to identify the factors associated with potential suicide risk among the bereaved family members of the Sewol ferry disaster. Participants with depression, clinically significant PTED, and complicated grief were associated with suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and having suicide preventive factors. Participants with prolonged PTED were also associated with suicide plan and having suicide preventive factors. The probability of having suicide ideation (from the fourth to the seventh year) and suicide preventive factors (in the fifth year) was significantly decreased compared to the first year since the disaster occurred. This study provided evidence by illuminating the long-term prognosis of suicide risk in disaster-affected families and its correlation with mental health factors. It offered a valuable insight that interventions addressing depression, PTED, and complicated grief are necessary in the long term to reduce their suicide risk.

Introduction

The Sewol ferry sinking disaster, which occurred in 2014, took the lives of 250 high school students who were on a field trip. Only 75 of the 325 students aboard the Sewol ferry survived. The sinking of the Sewol resulted in widespread social and political reactions within South Korea. The disaster was man-made because a later investigation discovered a problem concerning the state of the Sewol at the time of departure (Nash, Citation2014). The ship was imbalanced, as the center of gravity had changed due to previous modifications, and the boat was overloaded at the time of departure. Moreover, the captain misdirected the passengers and abandoned the ship early during capsizing (Park, Citation2014).

People who have experienced the traumatic loss of close family members can suffer from various mental health problems, including suicidal impulses, depression, insomnia, embitterment, and complicated grief (Guldin et al., Citation2017; Han et al., Citation2019; Yun et al., Citation2018). One of the most important consequences of bereaved family mental disorders is suicidal behavior, including suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. A nationwide examination of bereaved cohorts revealed that the risk of suicide, deliberate self-harm, and psychiatric illness increased 10 years after the loss of a close relative(Guldin el al., 2017). In that study, the hazard ratios were generally highest after the loss of a child, or a younger person, and after sudden loss by accident. A register-based cohort study reported an increased risk for suicide-related behaviors in bereaved young people around death anniversaries (Hiyoshi et al., Citation2022).

There can be various mental health conditions as risk factors for suicide risk in people affected by disasters (Jafari et al., Citation2020; Latham & Prigerson, Citation2004). After the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, the follow-up investigation revealed that depressive symptoms among survivors emerged as the most robust risk factor of suicidal ideation (Ran et al, Citation2015). A longitudinal study on Spanish university students’ suicidal thoughts has reported that depressive symptoms are associated, and this association is mediated by the meaning of life (Pérez Rodríguez et al., Citation2024).

Furthermore, analyzing the relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation among active U.S. Army service members, it was reported that clinically significant insomnia symptoms were associated with more than a threefold increase in suicidal thoughts (Vargas et al, Citation2020).

Additionally, in a previous study, when individuals affected by the Sewol ferry disaster were longitudinally tracked, it was observed that bereaved families who had lost their children were still grappling with lingering embitterment (Yun et al., Citation2018). Embitterment has been reported to be associated with aggressive thoughts, including suicidal ideation, and this was revealed in a study conducted with patients from the department of behavioral medicine (Linden & Noack, Citation2018). The concept of ‘posttraumatic embitterment disorder(PTED)’ has been proposed as a novel construct for a subgroup of adjustment disorders (Linden, Citation2003).

In a meanwhile, according to a longitudinal study targeting a community-based sample of recently bereaved relatives of the deceased, it was found that complicated grief increased the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Latham & Prigerson, Citation2004). Additionally, longitudinal study results from suicide bereaved families have reported that prolonged grief contributes to depression and suicide risk, and self-criticism plays a moderating role (Levi-Belz & Blank, Citation2023).

Moreover, sex, age, serious mental disorder, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, loss of a family member, poor economic status, little social support, and injury to the person and family/relatives are the most important risk factors for suicide after a natural disaster (Jafari et al., Citation2020). Sociodemographic, psychological, educational, familial, and social factors are related to suicidal ideation in adolescents after a technological disaster (Pouliot et al., Citation2022). South Korea has one of the highest suicide rates among countries worldwide. Research (Kim et al., Citation2019) has indicated that suicide rates are higher among males than females, and they increase with age. Additionally, it has been found that singles are at a higher risk of suicide compared to married individuals.

However, there is insufficient research on psychiatric problems related to the suicide risk among bereaved families after a disaster. Therefore, we investigated the relationship between suicidality and various mental health problems including depression, insomnia, PTED and complicated grief, using longitudinal follow-up data in bereaved families after the Sewol ferry disaster.

Methods

Study sample & design

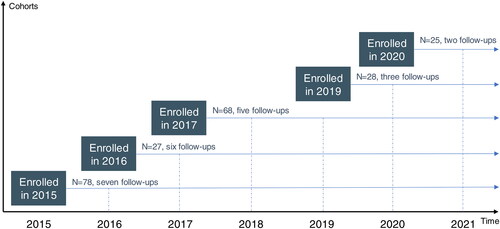

This study was performed as a mental health cohort study for people who have suffered a disaster. It was initiated in 2015, about 1 year after the Sewol ferry disaster. We contacted representatives of the bereaved families and explained the purpose and procedures of the study. After they agreed, we announced the study through the Ansan Mental Health Trauma Center, which was established to support Sewol ferry disaster-related people. With the help of the center, 254 of the 516 bereaved families (236 fathers and 280 mothers) were enrolled in this cohort study. We have followed their mental health through annual surveys and collected independent variables and outcomes. In this study, we used data from 226 participants gathered over 7 years after excluding 28 participants who missing in outcome variable (2015–2021) ().

Covariates

Depression

Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), which consists of two items and a total score of 0 to 6(Kroenke et al., Citation2003). An optimal cutoff score of 3 or above was applied to screen depression. The Korean version of the PHQ-2 has been validated and favorable consistency and test-retest reliability were reported (Seo & Park, Citation2015). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .749 at baseline.

Insomnia

Insomnia was measured using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), which consists of seven items with the total score ranging from 0 to 28(Bastien et al., Citation2001). Higher total scores are related to more severe sleep problems. A cutoff score of 16 was applied as clinically significant insomnia. The Korean version of the ISI has been validated, and adequate reliability was reported (Cho et al., Citation2014). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .901 at baseline.

PTED

PTED was measured using the PTED rating scale, which consists of 19 items including “(1) that hurt my feelings and caused considerable embitterment” and “(2) that led to a noticeable and persistent negative change in my mental well-being”. The degree of agreement was recorded on five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not true at all”) to 4 (“extremely true”) for each statement and the total score of 0 to 76(Linden et al., Citation2009). A mean total score of ≥ 1.6 and ≥ 2.5 suggests prolonged and clinically significant embitterment, respectively (Linden et al., Citation2009). The Korean version of the PTED rating scale has been validated, and good test-retest and internal reliability were reported (Shin et al., Citation2012). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .959 at baseline.

Complicated grief

Complicated grief was measured using the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG), which consists of 19 items and a total score of 0 to 76(Prigerson et al., Citation1995). The clinical threshold of the total score is 26, indicating significant grief with social, mental, and physical impairments (Szuhany et al., Citation2021). The ICG has been translated and validated in Korea and good internal consistency was reported (Han et al., Citation2016). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .946 at baseline.

Outcome variables

Potential suicide risk was measured using the P4 Suicidality Screener (P4), which begins with a question about suicidal ideation (“Have you had thoughts of actually hurting yourself?”) and consists of four items that measure past suicide attempts (“Have you ever attempted to harm yourself in the past?”), a plan (“Have you thought about how you might actually hurt yourself?”), the probability of completing the suicide (“There’s a big difference between having a thought and acting on a thought. How likely do you think it is that you will act on these thoughts about hurting yourself or ending your life some time over the next month?”), and preventive factors (“Is there anything that would prevent or keep you from harming yourself?”). The algorithm categorizes potential suicidal risk as minimal, lower, or higher. We employed four outcome variables derived from the items and classification of the P4: suicidal ideation, suicide plan, preventive factors for suicide, and the potential of the suicide risk classified as minimal, low, or high. A detailed classification of P4 can be found elsewhere (Dube et al., Citation2010).

Demographics

The demographic factors reported were age, sex (male or female), type of healthcare insurance (National Health Insurance or Medical aid recipients), and monthly household income (1 million South Korean Won ≈ 758 USD).

Analytical approach and statistics

A descriptive analysis was conducted to summarize the general characteristics of the participants and classify potential suicide risk at baseline. The results are reported as medians with interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed numerical data, and frequencies with percentages for categorical data, as appropriate. The Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test for non-normally distributed numerical data and Fisher’s exact test for categorical data were performed to assess the univariate relationship based on potential suicide risk. A linear-by-linear test for trend was performed to investigate the change of covariates over time. To evaluate the scale reliability over time, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) estimates and 95% confident intervals were calculated based on a mean-rating (3, k), consistency, 2-way mixed-effects model. The results were interpreted and reported in compliance with the Guidelines for Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (Koo & Li, Citation2016). A series of Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models were developed to identify the factors associated with potential suicide risk among the bereaved family members of the Sewol ferry disaster. The Huber-White’s sandwich estimator was used to compute the heteroscedasticity-robust standard error (Freedman, Citation2006). A two-tailed p-value < .05 was considered significant. All statistical procedures were conducted using Stata/MP 17.0 software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul of St. Mary’s Hospital at The Catholic University of Korea (registration no. KC15OIMI0261) and the National Medical Center (registration no. H-1505–054–002). Written consent was obtained from all participants. All participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Results

Baseline characteristics and classification of potential suicide risk

summarizes the baseline characteristics of the 226 study participants (97 males and 129 females). The median age was 48 years old. According to P4, 48 (21.2%), 43 (19.0%), and 135 (59.7%) of the participants were classified as having minimal, lower, and higher suicide risk, respectively. The proportion of individuals at higher suicide risk was higher among females compared to males, and it was particularly elevated among groups with the lowest monthly household income. Median of PHQ-2, ISI, PTED rating scale, and ICG were significantly differed by P4 at baseline (p < .05). The ICC estimates for a total of 51 items derived from five scales range from 0.719 to 0.931, indicating moderate to excellent scale reliability over time (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of bereaved family members of the sewol ferry disaster.

Trend of suicidal risk factors over time by potential suicide risk

summarizes the longitudinal change in suicidal risk factors over time since the disaster. It was identified that the PHQ-2 (from 6.0 to 3.0), PTED (from 2.7 to 2.2), and ICG (from 56.5 to 50.0) showed a significant decreasing linear trend over seven years of follow-up (p for trend < .05). Additionally, the ISI showed a significant cross-sectional difference in potential suicide risk groups between the second and seventh years from the disaster, while the ICG showed a significant difference between the fourth and seventh years from the disaster (p < .05).

Table 2. Trend of suicidal risk factors over time by potential suicide risk.

Factors associated with potential suicide risk

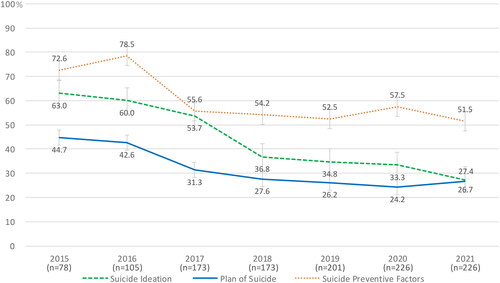

depicts the prevalence rates of potential suicide risk as categorized by suicide plan, preventive factors, and ideation. These rates demonstrated a gradual decrease over the seven-year follow-up. summarizes the results from a series of GEE models to identify the factors associated with potential suicide risk. The depression (odds ratio [OR] = 3.02, p < .001, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.05–4.44), clinically significant PTED (OR = 2.32, p = .004, 95% CI = 1.31–4.11) and complicated grief (OR = 2.34, p = .016, 95% CI = 1.17–4.66) were significantly associated with suicidal ideation. The depression (OR = 2.07, p = .001, 95% CI = 1.35–3.16), prolonged PTED (OR = 4.08, p = .001, 95% CI = 1.77–9.38), clinically significant PTED (OR = 9.39, p < .001, 95% CI = 3.92–22.46), and complicated grief (OR = 4.50, p = .016, 95% CI = 1.33–15.28) were significantly associated with suicide plan. The depression (OR = 2.92, p < .001, 95% CI = 1.93–4.42), prolonged PTED (OR = 1.89, p = .024, 95% CI = 1.09–3.28), and clinically significant PTED (OR = 2.39, p = .004, 95% CI = 1.33–4.32) were significantly associated with having a suicide preventive factors. Suicidal ideation was significantly decreased fourth years after the disaster (OR = 0.51, p = .023, 95% CI = 0.28–0.91) and were observed to decrease by 41.2% in the seventh year (OR = 0.41, p = .01, 95% CI = 0.23–0.74) compared to the first year after the disaster. Suicidal preventive factors also significantly decreased by 45.8% in the fifth years after the disaster (OR = 0.46, p = .032, 95% CI = 0.23–0.93) compared to the first year after the disaster.

Figure 2. Proportion of potential suicide risk over time among the Bereaved Family Members of the Sewol Ferry Disaster.

Table 3. Factors associated with potential suicide risk among the bereaved family members of the sewol ferry disaster.

Most of the responses regarding protective factors against suicide were related to the family or a pet left behind (83.6%), clarification of the truth of the disaster (5.9%), and religious reasons (4.9%). There was no statistically significant relationship was identified between P4 Screener classification and depression, insomnia, PTED, complicated grief, and time from disaster over seven-years follow-up period among bereaved families after the Sewol Ferry Disaster (p > .05; Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

The results of the 7-year longitudinal study tracking the mental health status of the Sewol ferry accident victims’ families indicate that the potential risk of suicide has gradually decreased over time. The GEE models revealed that suicidal ideation and suicide planning showed significant correlations with depression, PTED, and complicated grief over 7 years. However, we were unable to find factors significantly related to suicidality classification measured by the P4 Screener tool. We would like to discuss these research findings.

First, the study shows a decline in suicide risk, indicating that over time, the families may be better coping with the emotional shock caused by the accident and experiencing psychological recovery. Additionally, increased support and treatment following the accident may have contributed to reducing suicide risk (Han et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, it is interpreted that immediately after the Sewol ferry accident, the families of the victims expressed distrust in the government, demanding a thorough investigation into the truth of the incident. This sentiment played a role in the subsequent impeachment of the president and a change in the ruling party (NBCNEWS.COM, Citation2014). The previous research reported an increase in suicidal ideation and attempts within 12 months after the disaster (Kar, Citation2010). However, since this study initiated tracking 18 months after the disaster, it is presumed that this phenomenon was not reflected.

Second, we found that suicidal ideation and suicidal plans were related with depression, PTED, and complicated grief, in line with previous studies (Latham & Prigerson, Citation2004; Lee et al., Citation2023; Ribeiro et al., Citation2018). A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies reported prospective effects of depression and hopelessness on suicidal ideation, attempts, and death (Ribeiro et al., Citation2018). Although our research analysis method did not elucidate the prospective association of psychological factors such as depression with suicide-related factors, there is significance in analyzing all the follow-up data over 7 years. Meanwhile, our study results show that, particularly, PTED is associated with suicidal plans based solely on prolonged PTED levels, unlike depression and complicated grief. This indicates that even without clinically significant levels of PTED, disaster bereaved individuals are not free from the risk of suicide. A follow-up study 18 and 30 months after the Sewol ferry disaster revealed that the bereaved families were still embittered, and the results suggest that embitterment is associated with or can affect other psychiatric symptoms (Yun et al., Citation2018). It is noteworthy that in this study, PTED among the Sewol ferry disaster bereaved families appeared as one of the risk factors for their suicidal ideation or plans, and there is a need to pay attention to and intervene in their long-lasting feelings of anger. Complicated grief substantially heightens the risk for suicidality after controlling for important confounders, indicating an independent psychiatric risk for suicidal thoughts and actions among bereaved adults over time (Latham & Prigerson, Citation2004). Although previous studies have reported that insomnia is linked with suicidality in community and clinically depressed or anxious populations (Winsper & Tang, Citation2014), we did not find any significant associations after controlling the variables.

Third, the overall potential suicide risk was not related to psychological variables, including depression, insomnia, PTED, or complicated grief in this study. This result may be related to the finding that preventive factors were also positively associated with the psychological variables in this study and nullified the effect of suicidal ideation or plan. In our study results, factors that prevented bereaved individuals from acting on suicidal thoughts included the presence of remaining family members or pets, the need to uncover the truth about the accident, and religious reasons. These findings should be considered when programs for bereaved or disaster-affected people are implemented to decrease suicidal risk. A study that evaluated potential suicide risk in primary care and oncology patients showed that the most common factors preventing patients from attempting suicide were faith, family, future hope, and fear of failing in their attempt (Dube et al., Citation2010).

The limitations of this study should be discussed. First, sampling bias may be present. This study included 226 participants. In total, 250 students were lost to the Sewol ferry disaster and the estimated number of bereaved parents was about 500. Therefore, the results of this study could not represent the mental status of the non-participants. Still, this study included the largest sample of bereaved parents associated with the Sewol ferry disaster and considered the longest period of time following the disaster. Additionally, there is a limitation that the results of this study are difficult to generalize to the characteristics of the entire disaster bereaved population. Second, the measures for assessing suicidality and psychological distress were self-reported questionnaires. Therefore, the responses may have been over or under-estimated. Moreover, this study was not able to completely rule out the possibility of the influence of other confounding factors that were not measured. Third, because we gathered our initial data 1 year after the disaster, no pre-disaster psychological variables were used. Further studies that examine the preexisting data of these subjects could help elucidate cause-and-effect relationships.

Despite these limitations, this study provides insight into the longitudinal course of suicidality among the bereaved parents of the Sewol ferry disaster. Tracking the mental health status of the families affected by the Sewol ferry accident over a 7-year period provides valuable data for comprehensive treatment and support. Furthermore, the findings showing a connection between suicidal ideation and suicide planning with depression, PTED, and complicated grief underscore the influence of these emotional issues on suicide risk. Recognizing and providing appropriate treatment and support for these emotional difficulties is crucial. This long-term study can help understand changes in mental health and develop prevention and treatment strategies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data not available - participant consent

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

So Hee Lee

So Hee Lee, M.D., Ph.D. is a psychiatrist at the National Medical Center and has completed a fellowship in child and adolescent psychiatry. She earned her Ph.D. from Hanyang University, focusing on the impact of trauma and disasters on mental health. Dr. Lee has developed school-based mental health programs and has been dedicated to providing care and conducting research for North Korean defectors. She has published numerous papers in leading journals and frequently presents at domestic and international conferences.

Jin-Won Noh

Jin-Won Noh, MPH, MBA, Ph.D, USCPA is a chair of division of Health Administration at Yonsei University. She earned her first Ph.D. from Korean University focusing on health policy and second one at Groningen university in the Netherland focusing on global health program evaluation specialzed in vulnerable people(including refugee health). She has authored over 150 scientific peer-reviewed papers and has done over 100 projects. Now she is academic director of Association of Healthcare for Korean Unification and external cooperation director of Korean Society of Traumatic Stress Studies;KSTSS.

Kyoung-Beom Kim

Kyoung-Beom Kim, MPH, Ph.D., is a chair of the Department of International Healthcare Management at Catholic University of Daegu. He holds a master’s and doctoral degree in health policy and health administration. During his tenure as a researcher at the National Cancer Center’s National Cancer Control Institute, he gained experience in bigdata analysis for the National Health Insurance Service. Additionally, while working as a researcher in the Department of Psychiatry at the National Medical Center, he managed clinical data analysis and served as the field survey manager for the Seoul area in the nationwide epidemiological survey of mental disorders funded by ministry of health and welfare. He has diverse experience in the entire process of producing, refining, storing, managing, and utilizing healthcare data from practical survey operations in the field to research environments. Notably, he was an initial member of the registy of the Sewol ferry disaster, participating in the entire process of seven years of follow-up observations and completion. His work spans both clinical settings and research areas, demonstrating a comprehensive expertise in managing healthcare data.

Bo-Ram Shin

Bo-Ram Shin is a researcher at the National Center for Disaster Trauma, National Center for Mental Health in South Korea. She earned her M.A. from Sookmyung Women’s University. Her research interests include, but are not limited to, disaster trauma, psychological disorders, and mental health. She is currently a member of the Korean Psychological Association.

Jeong-Ho Chae

Jeong-Ho Chae, M.D, Ph.D. is a professor of Department of Psychiatry, and director of Anxiety, Mood and Stress Disorders Program at The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital. Dr. Chae has authored over 400 scientific peer-reviewed papers and chapters, has published more than 30 books. He is a founding president of Korean Society of Traumatic Stress Studies, Korean Academy of Medicine for Emotion, Cognition, and Behavior, and Korean Academy of Meditation in Medicine. He had served as a president of Korean Academy of Brain Stimulation, Korean Academy of Anxiety Disorders, Korean Society of Occupational Stress, and Korean Academy of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. Also he was a director of National Research Council for Disaster and Trauma Research and Development and a board of directors of International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). Dr. Chae specializes in research and practice on the psychological trauma, anxiety disorders, stress-related disorders, depression, neurophysiology, brain stimulation, positive psychiatry and affective neuroscience. He was awarded several major National Grants and has won numerous domestic and international academic awards for his research. Dr. Chae is a pioneer in the application of novel treatments such as TMS and tDCS to the treatment of mental disorders in Korea.

References

- Bastien, C. H., Vallières, A., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4

- Cho, Y. W., Song, M. L., & Morin, C. M. (2014). Validation of a Korean version of the insomnia severity index. Journal of Clinical Neurology (Seoul, Korea), 10(3), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2014.10.3.210

- Dube, P., Kroenke, K., Bair, M. J., Theobald, D., & Williams, L. S. (2010). The p4 screener: evaluation of a brief measure for assessing potential suicide risk in 2 randomized effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12(6), 27151. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.10m00978blu

- Freedman, D. A. (2006). On the so-called “Huber sandwich estimator” and “robust standard errors”. The American Statistician, 60(4), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1198/000313006X152207

- Guldin, M. B., Ina Siegismund Kjaersgaard, M., Fenger-Grøn, M., Thorlund Parner, E., Li, J., Prior, A., & Vestergaard, M. (2017). Risk of suicide, deliberate self-harm and psychiatric illness after the loss of a close relative: a nationwide cohort study. World Psychiatry: official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 16(2), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20422

- Han, D. H., Lee, J. J., Moon, D. S., Cha, M. J., Kim, M. A., Min, S., Yang, J. H., Lee, E. J., Yoo, S. K., & Chung, U. S. (2016). Korean version of inventory of complicated grief scale: psychometric properties in Korean adolescents. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 31(1), 114–119. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.1.114

- Han, H., Noh, J. W., Jung Huh, H., Huh, S., Joo, J. Y., Hong, J. H., & Chae, J. H. (2017). Effects of mental health support on the grief of bereaved people caused by sewol ferry accident. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 32(7), 1173–1180. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.7.1173

- Han, H., Yun, J. A., Huh, H. J., Huh, S., Hwang, J., Joo, J. Y., Yoon, Y. A., Shin, E. G., Choi, W. J., Lee, S., & Chae, J. H. (2019). Posttraumatic symptoms and change of complicated grief among bereaved families of the Sewol ferry disaster: one year follow-up study. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 34(28), e194. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e194

- Hiyoshi, A., Berg, L., Saarela, J., Fall, K., Grotta, A., Shebehe, J., Kawachi, I., Rostila, M., & Montgomery, S. (2022). Substance use disorder and suicide-related behaviour around dates of parental death and its anniversaries: a register-based cohort study. The Lancet. Public Health, 7(8), e683–e693. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00158-X

- Jafari, H., Heidari, M., Heidari, S., & Sayfouri, N. (2020). Risk factors for suicidal behaviours after natural disasters: a systematic review. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 27(3), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2020.27.3.3

- Kar, N. (2010). Suicidality following a natural disaster. American Journal of Disaster Medicine, 5(6), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.5055/ajdm.2010.0042

- Kim, J. W., Jung, H. Y., Won, D. Y., Noh, J. H., Shin, Y. S., & Kang, T. I. (2019). Suicide Trends According to Age, Gender, and Marital Status in South Korea. Omega, 79(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222817715756

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

- Latham, A. E., & Prigerson, H. G. (2004). Suicidality and bereavement: complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(4), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.34.4.350.53737

- Lee, J. E., Choi, B., Lee, Y., Kim, K. M., Kim, D., Park, T. W., & Lim, M. H. (2023). The relationship between posttraumatic embitterment disorder and stress, depression, self-esteem, impulsiveness, and suicidal ideation in Korea soldiers in the local area. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 38(1), e15. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e15

- Levi-Belz, Y., & Blank, C. (2023). The longitudinal contribution of prolonged grief to depression and suicide risk in the aftermath of suicide loss: The moderating role of self-criticism. Journal of Affective Disorders, 340, 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.023

- Linden, M. (2003). Posttraumatic embitterment disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 72(4), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1159/000070783

- Linden, M., Baumann, K., Lieberei, B., & Rotter, M. (2009). The post-traumatic embitterment disorder self-rating scale (PTED scale). Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(2), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.610

- Linden, M., & Noack, I. (2018). Suicidal and Aggressive Ideation Associated with Feelings of Embitterment. Psychopathology, 51(4), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1159/000489176

- Nash, J. (2014). South Korean Ferry was operating illicitly, state report says. TIME. Retrieved February 21, 2017, from https://time.com/2968886/south-korea-sewol-ferry-license-cargo

- NBCNEWS.COM. (2014). After Sewol Ferry disaster, koreans lower trust in government. NBCNEWS. Retrieved September 15, 2014, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/after-sewol-ferry-disaster-koreans-lower-trust-government-n173001

- Park, J. M. (2014). Accused South Korea ferry crew say rescue was coastguard’s job. Reuters. Retrieved September 15, 2014, from https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-southkorea-ferry-idUKKBN0ES0L520140617

- Pérez Rodríguez, S., Layrón Folgado, J. E., Guillén Botella, V., & Marco Salvador, J. H. (2024). Meaning in life mediates the association between depressive symptoms and future frequency of suicidal ideation in Spanish university students: A longitudinal study. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 54(2), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.13040

- Pouliot, E., Maltais, D., Lansard, A. L., Dubois, P., & Fortin, G. (2022). Factors related to the presence of suicidal ideations in adolescents after a technological disaster. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 76, 103003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103003

- Prigerson, H. G., Maciejewski, P. K., Reynolds, C. F., Bierhals, A. J., Newsom, J. T., Fasiczka, A., Frank, E., Doman, J., & Miller, M. (1995). Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59(1-2), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2

- Ran, M. S., Zhang, Z., Fan, M., Li, R. H., Li, Y. H., Ou, G. J., Jiang, Z., Tong, Y. Z., & Fang, D. Z. (2015). Risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents after Wenchuan earthquake in China. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 13, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.016

- Ribeiro, J. D., Huang, X., Fox, K. R., & Franklin, J. C. (2018). Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 212(5), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.27

- Seo, J. G., & Park, S. P. (2015). Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and PHQ-2 in patients with migraine. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 16(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0552-2

- Shin, C., Han, C., Linden, M., Chae, J. H., Ko, Y. H., Kim, Y. K., Kim, S. H., Joe, S. H., & Jung, I. K. (2012). Standardization of the Korean version of the posttraumatic embitterment disorder self-rating scale. Psychiatry Investigation, 9(4), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2012.9.4.368

- Szuhany, K. L., Malgaroli, M., Miron, C. D., & Simon, N. M. (2021). Prolonged grief disorder: course, diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing), 19(2), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20200052

- Vargas, I., Perlis, M. L., Grandner, M., Gencarelli, A., Khader, W., Zandberg, L. J., Klingaman, E. A., Goldschmied, J. R., Gehrman, P. R., Brown, G. K., & Thase, M. E. (2020). Insomnia symptoms and suicide-related ideation in U.S. army service members. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 18(6), 820–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2019.1693373

- Winsper, C., & Tang, N. K. (2014). Linkages between insomnia and suicidality: prospective associations, high-risk subgroups and possible psychological mechanisms. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 26(2), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.881330

- Yun, J. A., Huh, H. J., Han, H. S., Huh, S., & Chae, J. H. (2018). Bereaved families are still embittered after the Sewol ferry accident in Korea: A follow-up study 18 and 30 months after the disaster. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 82, 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.12.007