?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Post-traumatic growth (PTG) involves a positive transformation in the survivor’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to life. However, little is known about the factors facilitating PTG in adolescent survivors of childhood sexual abuse. This study examined how potential variables (self-concept, dissociation, the severity of the abuse, and distress symptoms) contribute and interact to account for perceived PTG in a sample of 70 Israeli adolescents, all survivors of childhood sexual abuse, along with one of their parents. It also explored how survivors’ self-concept, the tendency for dissociation, and distress symptoms moderated the association between abuse severity and PTG. Regression decision trees and linear regression models addressed the study’s questions. The results of the regression trees indicated that survivors with low global self-concept had lower levels of PTG, whereas survivors with high global self-concept and low tendencies for dissociation displayed higher levels of PTG. The linear regression analysis also pointed to the contribution of abuse severity and survivors’ global self-concept to PTG. A positive association was only found between abuse severity and PTG for survivors with moderate to high global self-concept. The discussion centers on the combined pivotal role of positive global self-concept, low dissociation, and abuse severity in facilitating adolescents’ PTG.

Introduction

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is defined as any sexual activity ranging from fondling to sexual intercourse involving a minor and perpetrated by a significantly older person. This abuse typically occurs through coercion, force, or the use of overt or covert threats (Hetzel & McCanne, Citation2005). It is considered a worldwide phenomenon that affects hundreds of thousands of children globally. The European Council recently estimated that one in five children worldwide will experience CSA (Ferragut et al., Citation2022). Meta-analyses nevertheless point to considerable variability in prevalence rates worldwide. Pereda et al. (Citation2009) summarized 65 studies from 22 different countries and found a mean CSA prevalence of 7.9% in males and 19.7% in females. Stoltenborgh et al. (Citation2011) analyzed 217 studies and reported a combined prevalence of 11.8%. Data from Israel collected from 12,035 Jewish and Arab adolescents showed a prevalence of 18.7% (Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2018).

Because CSA involves a violation of the child’s body as a ‘safe, private place,’ it constitutes a uniquely traumatic event that leads to a constant threat of self and body fragmentation that can damage body-mind integration (Lev-Wiesel, Citation2015). Studies have confirmed the deleterious short and long-term consequences of CSA that include, but are not limited to, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic symptomatology (PTS), eating disorders, low self-esteem, suicidal ideation, feelings of guilt, and stigmatization (e.g., Hailes et al., Citation2019; Lo Iacono et al., Citation2021).

Along with these adverse consequences, researchers have also found that post-traumatic growth (PTG) may emerge as a parallel process in the wake of abuse (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1995, Citation1996). PTG, as defined by Tedeschi and Calhoun (Citation2004), entails a positive transformation of the survivor’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to life that includes finding new possibilities and new pathways, expanding social relationships, promoting personal strength and self-reliance, strengthening spiritual beliefs, and gaining a deeper appreciation of life and its value (Elderton et al., Citation2017; Tedeschi & Moore, Citation2021). It is described as the rebuilding and reorganization of global beliefs and goals following “seismic events,” which, according to Tedeschi and Calhoun (Citation2004), can threaten or shatter individuals’ “schematic structures that have guided understanding, decision-making, and meaningfulness” (p. 5).

Current theorizations related to the possibility of PTG after CSA differ since the trauma occurs at a young age, potentially before worldviews are fully formed. In addition, many researchers have cast doubt on the ability of children in general (Kilmer, Citation2006; Taku et al., Citation2012) and child CSA survivors in particular (Sagar & Choudhary, Citation2024) to engage in the cognitive and emotional processes required for PTG. This skepticism stems from the prerequisite of cognitive maturity for self-reflection, as well as the ability to assess losses and gains after hardships, articulate experiences to others, and individuals’ emotional capabilities during trauma (Sagar & Choudhary, Citation2024). However, over the past 20 years, efforts have been made to study PTG in children and adolescents (Meyerson et al., Citation2011), primarily in cancer patients (Atay Turan et al., Citation2023), adolescents affected by parental cancer (Morris et al., Citation2020) or close family member loss (Asgari & Naghavi, Citation2020), and adolescents who experienced PTG after exposure to war (Kimhi et al., Citation2010), or earthquakes (Tang et al., Citation2021).

In addition, several empirical studies have documented PTG in CSA survivors (Kaye-Tzadok & Davidson-Arad, Citation2016; Lahav et al., Citation2020; Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2004; Shakespeare-Finch & Dassel, 2009; Wright et al., Citation2007). Qualitative studies on CSA adolescent survivors in therapy have revealed increased personal strength, renewed hope, and the discovery of meaning (Volgin et al., Citation2019). These authors suggested that survivors of childhood sexual abuse can engage in various cognitive processes that foster post-traumatic growth, including acknowledging the trauma, grappling with the negative emotions linked to the abuse, such as anger, distrust, and disgust, and integrating new insights into their narrative of resilience. This integration allows victims of CSA to challenge detrimental trauma-related beliefs surrounding the violated body, the disempowered and stigmatized self, and a perception of the world as unjust and malevolent. Consequently, the traumatic experience may become a defining element in the survivors’ identity and perspective (Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2015).

At the same time, studies have noted that PTG and post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms in trauma survivors (Schubert et al., Citation2016; Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, Citation2014) and in CSA survivors can co-occur (Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2004; Shakespeare-Finch & Dassel, 2009). Several scholars suggest that these findings may raise the question of whether PTG truly signifies achieving a long-lasting positive personal transformation and hint at the existence of a fabricated positive illusion of PTG, wherein survivors construct an illusion of growth amidst their negative experiences through intrusive or behavioral rumination or dissociation (Boals, Citation2023; Lahav et al., Citation2016, Citation2020; Schubert et al., Citation2016; Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, Citation2014) that shields survivors from traumatic content and may impede psychological adjustment (Maercker & Zoellner, Citation2004). On the other hand, others suggest that the coexistence between the two constructs reflects individuals’ endeavor to reconcile their cognitive appraisals and explore the broader meaning of the traumatic event despite symptoms (Maercker & Zoellner, Citation2004; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004).

Nonetheless, studies have reported positive associations between PTG and a wide range of positive mental health resources (Meyerson et al., Citation2011) in adults, children and adolescents, such as a sense of control and hope (Kaye-Tzadok & Davidson-Arad, Citation2016; Vaughn et al., Citation2009), optimism (Currier et al., Citation2009; Phipps et al., Citation2007), competency beliefs (Cryder et al., Citation2006), self-esteem (Phipps et al., Citation2007), as well as positive self-concept, self-acceptance (Wamser-Nanney et al., Citation2018; Zhou et al., Citation2018) and resilience (Wamser-Nanney et al., Citation2018)

PTG and resilience are considered separate concepts since resilience typically denotes a dynamic developmental process that reflects positive adaptation to challenging life circumstances, whereas PTG signifies a transformative process whereby survivors undergo profound positive changes beyond mere coping and adjustment in the face of adversity. Nevertheless, these two constructs share several similarities (Cryder et al., Citation2006). For example, resilience models on positive change after trauma (Hobfoll, Citation2002; Kilmer et al., 2006; McElheran et al., Citation2012; Vázquez, Citation2013) have highlighted the critical role of personal resources such as self-concept in effectively coping with negative life events (Richardson Gibson & Parker, Citation2003). Studies and models have also emphasized the importance of active coping strategies, such as seeking meaning and spirituality, in promoting PTG. They suggest that personal resources and behaviors can combat self-defeating negative trauma-related cognitions and lay the groundwork for future PTG that enables the survivor to recover and acquire the resources to cope with stressful situations (Barakat et al., Citation2006; Hobfoll, Citation2002).

Overall, these works suggest that children and adolescents are likely to exhibit a wide range of responses to traumatic events dictated by their individual resources and the severity of the trauma (Sagar & Choudhary, Citation2024). The current study was designed to better delineate the characteristics of adolescents who are more likely to evidence PTG. This was done by assessing global self-concept, the tendency for dissociation, the level of symptomatology, as well as the severity of the abuse in adolescent CSA survivors.

Personal Resources: Adolescents’ Self-concept

Self-concept is typically seen as a multifaceted hierarchical and developmental representation of the self or the perception of one’s personal and interpersonal characteristics. It consists of a structured set of characteristics, traits, attitudes, opinions, and beliefs that individuals associate with themselves in different stages of development and situations (Harter, Citation1990; Kozina, Citation2019). Self-concept covers cognitive competency schemas as well as an affective component relating to how individuals perceive and feel about their attributes or traits and the ways they interact within their social environment (Côté, Citation2009).

Adolescence is a period of major transformation in self-concept where adolescents strive to develop a more sophisticated and abstract sense of identity and social belonging (Steinberg, Citation2013). They work to define their unique selfhood that is distinct from their parents and peers (Côté, Citation2009) by actively navigating and defining their roles, relationships, and contexts (Goldner & Berenshtein-Dagan, Citation2016).

The physical, social, and emotional changes characterizing adolescence can fragilize adolescents’ perceptions and potentially intensify negative self-perceptions (Esnaola et al., Citation2020). The findings on the trajectory of self-concept in adolescence are inconsistent. Parker (Citation2010) suggested an initial surge in self-concept after the transition to middle school, followed by a subsequent decline, whereas Esnaola et al. (Citation2020) reported a linear trend with a decreasing monotonic pattern. Other researchers posit a U-shaped pattern consisting of a dip in self-concept during mid-adolescence, followed by an upward trend into early adulthood (Marsh & Ayotte, Citation2003)

Studies have indicated that CSA profoundly impacts the perception of the self as a result of the interpersonal harm, threat, humiliation, and exploitation of the body, which survivors experience as a complete loss of power that has been brutally or manipulatively taken from them by the perpetrator (Keshet & Gilboa-Schechtman, Citation2017; Krayer et al., Citation2015). This negative perception of the self may be intensified by the harm inflicted on bodily integrity, which can elicit disgust, reluctance, lack of acceptance, and self-rejection (Badour et al., Citation2013). Several studies have found significantly lower levels of self-esteem and self-mastery in children, adolescents, and young adult victims of CSA (Gewirtz-Meydan, Citation2020; Keshet & Gilboa-Schechtman, Citation2017). Likewise, a meta-analysis of 95 studies probing the magnitude of the effect of trauma and maltreatment on self-concept in children and adolescents reported a small negative relationship between maltreatment and trauma exposure and self-concept. However, there was a significantly stronger effect size for studies that only examined sexual abuse as compared to all other types of exposure to trauma (Melamed et al., Citation2024).

Theoretical models of PTG in child CSA survivors, nevertheless, underscore the role of the self-system, including self-concept, in catalyzing PTG (Kilmer, Citation2006; McElheran et al., Citation2012). Studies have highlighted the ways in which self-concept can mitigate distress symptoms in adolescents subjected to maltreatment or traumatic events (Turner et al., Citation2010, Citation2017; Zhou et al., Citation2018). Notably, adolescents with a positive self-concept are typically believed to have sufficient internal resources of confidence and positive emotions to navigate external threats better (Tang et al., Citation2021). Likewise, a positive self-concept is seen as a protective shield against adverse experiences that can safeguard children and adolescents from trauma-related stress (Moksnes et al., Citation2010; Yin et al., Citation2017). Positive self-concept and self-acceptance were also found to be positively correlated with PTG in adults (Wamser-Nanney et al., Citation2018; Zhou et al., Citation2018).

The Tendency for Dissociation

Adverse and traumatic experiences in childhood, such as child sexual abuse, have been linked to the emergence of dissociation (Bailey & Brand, Citation2017; Hodges et al., Citation2013). Dissociation is defined as a disruption in a person’s consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of the environment (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022) and is often considered to be a learned automatic response to reduce or avoid aversive emotions, thoughts, and memories (Nijenhuis & Van der Hart, Citation2011). Although dissociation offers emotional relief in the short term, it often becomes embedded in survivors’ mental processes long after the traumatic exposure, thus disrupting neurocognitive functioning (Lyssenko et al., Citation2018), fracturing the survivors’ personalities, and reducing survivors’ confidence in their reality-monitoring ability, perceived control, and sense of self (Goldner et al., Citation2023; Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2023).

In recent years, researchers have made efforts to understand the contribution of dissociation as a maladaptive coping mechanism to shaping trauma survivors’ PTG. They have argued that because recurrent use of dissociation to cope with trauma disrupts schema reconstruction, it leads to the formation of fragmented and disintegrated belief systems that preclude survivors from re-processing the traumatic event, developing more complex integrated self-concepts and worldviews, or experiencing profound transformations of PTG (Lahav et al., Citation2016).

Nevertheless, studies in Israel have reported mixed results with respect to the contribution of dissociation to the emergence of PTG. For example, peri-traumatic dissociation (the normative emotional detachment galvanized during or immediately after a traumatic event) was correlated two months later with PTG in adult CSA survivors (Sultana & Lahav, Citation2023). At the same time, PTG was also found to explain elevated levels of revictimization among survivors exhibiting high dissociation (Lahav et al., Citation2020). These variable findings may hint at the potential positive function of maladaptive or illusory coping mechanisms in the PTG process and call for further investigation (Sultana & Lahav, Citation2023).

The Severity of the Trauma and PTG

The severity of distress symptoms in CSA survivors was found to be related to the severity of the abuse, as defined in terms of its characteristics, duration, whether it occurred within or outside the family (Briere, Citation2006; Gokten & Duman, Citation2016), the number of attackers, whether the injury included penetration (Maikovich-Fong & Jaffee, Citation2010), and whether force or violence was used (Mueller-Pfeiffer et al., Citation2013). Much less is known about the contribution of the severity of the abuse to survivors’ PTG. Yet, preliminary evidence indicates that adult survivors who were abused at home by a family member had higher levels of PTG than survivors abused by a non-family member (Lev-Weisel et al., 2004). These findings may echo the complex association between PTS and PTG.

The Current Study

The literature suggests that survivors’ self-concept, the tendency for dissociation, and distress symptoms can impact their PTG. However, only a few studies have examined the contribution of these factors to PTG in adolescent survivors of CSA. It also remains unclear which variables have the greatest influence and how these variables interact to explain PTG. In addition, the possibility that survivors’ global self-concept and the tendency for dissociation moderate the association between the abuse severity and survivors’ PTG calls for scrutiny. Thus, to better identify adolescents most likely to exhibit PTG, the present study utilized decision tree regression models and traditional regression analysis to pinpoint the most prominent statistical variables and determine how these variables interact. We hypothesized that survivors with a higher global self-concept and a lower tendency for dissociation would exhibit higher PTG. Given the mixed findings related to the contribution of distress symptoms to PTG, we did not formulate a specific hypothesis regarding the contribution of distress symptoms to PTG. Further, given the rare findings on the contribution of the severity of the abuse to survivors’ PTG, we did not formulate specific hypotheses as to the contribution of the severity of the abuse to PTG, the moderating role of survivors’ self-concept, or the tendency for dissociation on the association between the severity of abuse and survivors’ PTG. Note, however, that we examined perceived PTG, which assesses the extent to which adolescents believe they have changed positively due to a traumatic event, not actual PTG.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Seventy adolescents who experienced sexual abuse (63 girls, 90%, Mage =15.08, SD = 2.14, age range 10 to 18) and one of their parents (62 mothers, 94%) took part in this study. The participants were recruited from treatment centers under the auspices of the Israel Ministry of Welfare, devoted to treating CSA in the northern district of Israel, using a convenience sampling design. After obtaining ethical approval from the ethics committee for research on human subjects of the Faculty of Welfare and Health Sciences of the University of Haifa, Israel (#146/19), the second researcher contacted the parents and provided information about the goals of the study. The participants were guaranteed confidentiality. All the participants (parents and adolescents) signed written consent forms. The first author administered the self-concept, distress symptoms, dissociation, and PTG questionnaires to the adolescents during face-to-face meetings. Parents completed the questionnaire on the severity of the abuse in their free time.

All the participants were Israeli residents. Fifty-eight percent of the parents were married, and the rest were divorced (36%), widowers (3%) or single parents (3%). Most of the parents were employed (84%). Almost half of the parents (47%) had a high school education, and 30% had college degrees (30%), whereas 23% had elementary school certificates or did not complete high school.

According to the parents, the average age of the child at the time of the first abuse was 10.88 (SD = 2.90, age range 5 to 16). Forty-seven percent of the perpetrators were adult family members, 20% were adult family acquaintances, neighbors, or strangers, and the remainder were peers or older friends (29%). Four percent did not provide this information. In 87% of the cases, the perpetrators exposed their genitals, 91% were asked to expose their genitals to the offenders, 89% had their genitals touched, and 76% were asked to touch the offenders’ genitals. Forty percent of the participants experienced sexual intercourse without full penetration, and about a third (35%) were forced to have sexual intercourse with full penetration. Twenty-nine percent of the participants experienced multiple cases of abuse, and 62% experienced prolonged abuse. No correlations were found between the victims, demographics, or the severity of the abuse and the study variables.

Measures

Self-concept Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, Citation1985)

The global self-concept scale (6 items) from the Self-concept Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, Citation1985) was used to assess the victims’ global self-concept. The items are rated using Harter’s 4-point format (1985) to reduce socially desirable responses. The victim is first asked to decide which “kind of kid” is most like him or her and then asked whether this is only ‘sort of true’ or ‘really true’ for him or her. A score of 1 represents a negative self-concept, whereas 4 represents the positive end of the continuum. The Harter Self-concept Profile for Children (SPPC) is the most widely used measure of childhood self-esteem and has demonstrated good psychometric qualities (Muris et al., Citation2003). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for global self-concept was .88.

The Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, Citation2000)

The BSI-18 comprises 18 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, covering three sub-scale scores of somatization, depression, and anxiety (6 items each), assessing participants’ general distress. For each item, participants report how much a given problem distressed or bothered them during the past week (0 = not at all, to 4 = extremely). An average score was calculated based on all 18 items, with a higher score indicating greater severity of symptoms. A recent meta-analysis indicated internal reliability exceeding .70 (Govindasamy et al., Citation2020). The BSI-18 has been administered to adolescents (e.g., Kim et al., Citation2021). The Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .93.

The Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale (A-DES; Armstrong et al., Citation1997)

This self-report questionnaire examines adolescents’ general tendency toward normal and pathological dissociative phenomena. It consists of 30 items, each rated on an 11-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = never experienced to 10 = experienced all the time). The questionnaire is divided into four subscales: dissociative amnesia, absorption and imaginative involvement, passive influence, and depersonalization and derealization. The overall score is obtained by summing the participant’s responses, with a higher score indicating more severe dissociation. The questionnaire effectively distinguishes between adolescents with dissociative disorders (Armstrong et al., Citation1997), PTSD (Correia-Santos et al., Citation2022), and those without these diagnoses. The Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .94.

The Post Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1995, Citation1996)

The Post Traumatic Growth Inventory is a 21-item widely- used measure of perceived positive changes after trauma. Responses are made on a 6-point scale (0 = I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis, to 5 = I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis). The PTGI yields a total score and five subscale scores: new possibilities (5 items), relating to others (7 items), personal strength (4 items), spiritual change (2 items), and appreciation of life (3 items). The scale has shown good reliability in sexual assault survivors (Basharpoor et al., Citation2021; Walker-Williams et al., Citation2013) and adolescents (Meyerson et al., Citation2011). In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the global PTGI score was .95.

The Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ; Finkelhor et al., Citation2005)

To prevent distress among adolescents, we asked the parents to fill out a modified version of the JVQ sexual abuse scale to evaluate the accumulating linear severity of the abuse. This scale is composed of 10 items presented in ascending order of severity (e.g., “Has someone flashed their sexual organs to you against your will?”) For each item, the parents were instructed to assign a score ranging from 0 to 4, where the higher the score, the closer the familial relationship between the offender and the victim as well as whether the abuse included violence or penetration. A score of 1 pertains to cases where the offender is a stranger, neighbor, or friend older than the victim. A score of 2 relates to cases where the offender is the same age as the victim or older. A score of 3 applies to cases where the offender is a distant family member (cousin or relative), and a score of 4 signifies cases where the offender is a close family member (parent, sibling, or grandparent). A score of zero indicates that the offense listed in the question did not take place.

In addition, parents were asked to indicate exposure to online pornographic abuse (yes/no), the age of the child at the time of the sexual abuse, the number of instances of sexual abuse (1 to 3), and whether the abuse was prolonged (yes/no). An overall score for the severity of sexual abuse was computed based on the parents’ responses, which gave greater weight to items associated with full penetration and violent, prolonged abuse at younger ages perpetrated by a family member from the nuclear family which was calculated as follows:JVQ=. In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the severity score was .91. Previous studies have reported a correlation between the severity of sexual abuse and trauma symptoms as well as indices of depression, introversion, and extroversion among samples of children and adolescents (e.g., Pereda et al., Citation2018).

Data Analyses

To detect possible multicollinearity among the study variables, we examined the associations between the explanatory variables (i.e., participants’ tendency for dissociation, the severity of abuse, and distress symptoms) and participants’ PTG using a series of Pearson correlation coefficient analyses before conducting the multivariate regression analyses. Next, to explore the ways in which the explanatory variables interacted to explain PTG and the associations between PTG and the severity of abuse across different values of survivors’ self-concept and dissociation, we employed two decision tree regression models.

The decision tree regression approach does not assume or require any structure for the data or an a-priori model. Therefore, it is suitable for dealing with non-linear relationships between variables and identifying optimal cutoff points in the data to achieve the best classification of categories of the dependent variable (Strobl et al., Citation2009). In addition, while regression tree analyses typically require large samples using machine learning approaches, the current study followed previous studies with relatively small samples of CSA survivors or maltreated children that aimed to detect the sequence of “split” points and potential interactions between explanatory variables (e.g., Hébert et al., Citation2006; Sledjeski et al., Citation2008).

To determine the most influential variables, we conducted a linear regression model. The sample size of the regression analysis was determined using Daniel Soper’s a-priori Sample Size Calculator for Multiple Regression (Bakker et al., Citation2020) with four explaining variables, an anticipated effect size of .20, a power of .80, and a probability level of .05. The calculation indicated that the minimum required sample size was 65.

Results

Preliminary Analysis: The Associations between the Explaining Variables and Participants’ PTG

As shown in , the severity of the abuse (JVQ) (r = .24*) and survivors’ global self-concept (SPPC) were positively correlated with PTG (PTGI) (r =.55***), whereas survivors’ tendency for dissociation (A-DES) (r = −.49***) and distress symptoms (BSI) (r = −.49***) were negatively correlated. In addition, the tendency for dissociation and distress symptoms were highly correlated, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of .75. Therefore, we excluded participants’ distress symptoms (BSI) as an explanatory variable from the regression analyses to avoid multicollinearity.

Table 1. Pearson correlations between the study variables.

Accounting for PTG

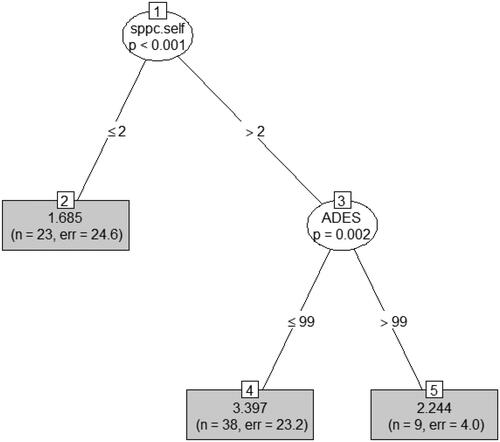

To understand how the explanatory variables interacted to account for adolescents’ PTG, we conducted a decision tree regression model with the R party package (Hothorn et al., Citation2006) using random forest variable selection and Monte Carlo simulation for multiple testing adjustment (Strasser & Weber, Citation1999). The decision tree algorithm was implemented as follows. First, the null hypothesis of independence between each of the four independent variables (i.e., global self-concept (SPPC), the tendency for dissociation (A-DES), and the severity of the abuse (JVQ), and the respective dependent variable (i.e., PTGI) was tested. If the independent variable had no association with the dependent variable, this variable was not included in the model. A random selection of independent variables was performed based on the strength of their association with the dependent variable where the first selected independent variable had the strongest association with the dependent variable. This association was estimated by a p-value corresponding to a test for the partial null hypothesis of a single independent variable and the dependent variable. Then, the algorithm implemented a binary split in the selected independent variable based on the corresponding p-value of less than .05. These steps were repeated recursively for each of the independent variables that were significantly associated with the dependent variable until no remaining variable was associated with the dependent variable.

The decision tree analysis revealed a noteworthy division in survivors’ global self-concept (SPPC). Specifically, survivors with a score of 2 or lower exhibited a lower level of PTG (PTGI), while survivors with a global self-concept (SPPC) equal to or higher than 2 and a tendency for dissociation (A-DES) of 99 or lower displayed a higher level of PTG (PTGI). None of the other explaining variables was found to have a significant impact on survivors’ PTG (PTGI).

To confirm the findings, a traditional linear regression analysis was also conducted to determine the most influential variables on the survivors’ PTG. In this analysis, the severity of the abuse (JVQ), global self-concept (SPPC), and the tendency for dissociation (A-DES) were entered as the independent variables, and survivors’ PTG (PTGI) was entered as the dependent variable. As shown in , the regression analysis explained 42% of the variance (F (3,66) = 15.5, p ≤ .0001). The severity of the abuse (β =.248, p =.011) and global self-concept (β =.438, p = .0003) contributed positively to survivors’ PTG, while the tendency for dissociation contributed negatively (β = −.228, p = .049).

Table 2. Regression Analysis Predicting PTG.

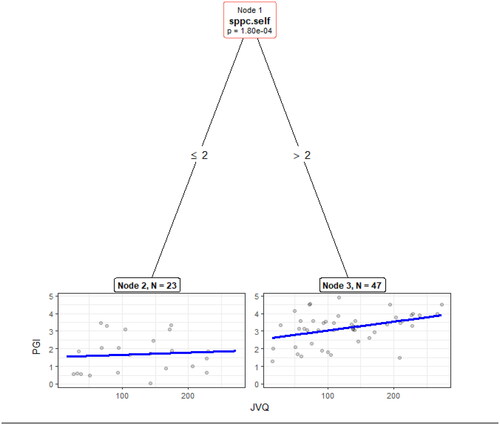

To investigate whether the association between survivors’ PTG (PTGI) and the severity of abuse (JVQ) was moderated by the survivors’ global self-concept (SPPC) or the tendency for dissociation (A-DES), we utilized the ‘lmtree’ function from R’s ‘partykit’ package (Zeileis et al., Citation2008). This analysis leverages model-based recursive partitioning (MOB), which identifies optimal partitioning through M-fluctuation tests (Mf) based on a linear relation and provides a linear regression solution for each node in the final model. The criterion for introducing splits in the tree was a significance level of .05 for the split.

As depicted in , the results indicated that the survivors’ global self-concept (SPPC) moderated the association between the severity of abuse (JVQ) and PTG (PTGI), where the positive association between the severity of abuse and PTG was only significant for survivors with a global self-concept exceeding 2 (Node 3, B =.005, p =.008). By contrast, the relationship was not statistically significant for survivors with a global self-concept of 2 or lower Figure 2.

Figure 1. Regression tree predicting PTG score.

Note. ADES measures Dissociation, Self-SPPC measures Global Self-Perception. Survivors with a score of 2 or lower exhibited a lower level of PTG (PTGI), whereas survivors with a global self-perception (SPPC) equal to or higher than 2 and a tendency for dissociation (A-DES) of 99 or lower displayed a higher level of PTG (PTGI).

Figure 2. Linear regression-based Tree for PTGI score as a function of JVQ across sample sub-groups.

Note. Self-SPPC measures Global Self-Perception, PGI measures PTG, JVQ measures the Severity of the Abuse. The plots show linear regressions of PTG by JVQ. Survivors’ global self-perception (SPPC) moderated the association between the severity of abuse (JVQ) and PTG (PGI), in which the positive association between the severity of abuse and PTG was only significant for survivors with a global self-perception exceeding 2 (Node 3, B =.005, p =.008). In contrast, the relationship was not statistically significant for survivors with a global self-perception of 2 or lower.

Discussion

The current study investigated the relationship between global self-concept, the tendency for dissociation, distress symptoms, and the severity of the abuse and PTG in adolescent CSA survivors. The findings indicated a positive association between survivors’ global self-concept and PTG, as well as the contribution of higher self-concept to their PTG. These results point to the essential role of positive global self-evaluation in CSA survivors, which helps develop a deeper and more fine-grained understanding of themselves and the world (Arredondo & Caparrós, Citation2021). They are consistent with resilience research that underscores the paramount importance of belief in one’s competence in survivors’ capabilities and future prospects. These convictions have a significant influence on individuals’ responses to stress or trauma by fortifying their capacity to navigate and endure challenging circumstances over time (Cryder et al., Citation2006). This is especially crucial for CSA survivors since CSA constitutes a form of extreme betrayal that is likely to undermine survivors’ core beliefs about themselves and result in a sense of devaluation, powerlessness, and stigmatized self-identity (Keshet & Gilboa-Schechtman, Citation2017; Krayer et al., Citation2015; Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2015).

This is amplified during adolescence, a developmental stage in which adolescents endeavor to establish a cohesive identity and consolidate a stabilized self-concept (Gušić et al., Citation2016; Powers & Casey, Citation2015). Leveraging this flexibility in the self-system during adolescence can help adolescents combat trauma-related negative cognitions and integrate the trauma in a way that fosters growth. The importance of self-concept in facilitating Israeli adolescents’ PTG is especially interesting, given the embeddedness of PTG in collective action, mutual support, and shared responsibility in promoting resilience in the face of adversity (Laufer & Solomon, Citation2006).

By contrast, the findings showed that when survivors have a lower self-concept and, in particular, if they tend to dissociate while exhibiting altered identity confusion and memory problems, their growth may be hindered. This may hint that constructive aspects of growth are associated with less reliance on dissociative strategies. When adolescents compartmentalize and block the abuse and its associated pain, they may be more likely to face difficulties integrating the trauma and transforming. These findings are consistent with qualitative studies on the lived experiences of CSA survivors who have experienced prolonged dissociation associated with a subjective sense of anomaly, oddness, strangeness, and lack of control (Černis et al., Citation2021; Goldner et al., Citation2023).

Contrary to previous data on adults that demonstrated a curvilinear relationship between PTS and PTG, where growth tended to be low when symptoms were either low or high and high when symptoms were moderate (Schubert et al., Citation2016; Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, Citation2014), the findings here revealed a negative association between survivors’ distress symptoms and perceived PTG. These findings are concordant with previous research reporting a negative correlation between perceived growth and heightened general distress and PTS in sexual assault survivors (Frazier et al., Citation2001, Citation2009; Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2004). They may suggest that the distress experienced by adolescents leads to emotional exhaustion and depletes their emotional resources, thus making it challenging for them to explore new perspectives and deliberately engage in a profound search for meaning and personality growth in the face of the heavy demands of processing and integrating their traumatic experiences (Lahav et al., Citation2020). They may become preoccupied with negative thoughts and feelings and influenced by negative cognitive biases that lead them to focus on the negative aspects of their experiences while discounting growth opportunities. This preoccupation may be heightened by direct experiences of the constant clashes and conflicts in the Middle East. Terrorist attacks and wars have exposed most Israelis to anxiety, loss, and trauma, thus prompting adolescents to perceive life in Israel as somewhat dangerous and personally threatening. This may lead to a lack of trust in the country’s leaders and the view that their future is unstable (Goldner et al., Citation2019). It thus poses an additional emotional burden that impedes growth. Note, however, that the average score of participants’ distress symptoms was relatively low, which might mask the possibility of positive associations.

In contrast, the correlation analysis and the traditional regression revealed positive associations with the severity of the abuse based on the degree of violence involved in the abuse, the proximity to the offender, the age at which the abuse took place, and adolescents’ PTG. The more serious and earlier the abuse and the closer the relationship with the perpetrator, the higher the level of reported PTG. It is thus possible that the intensity of the trauma challenges and closes off survivors’ current cognitive schemas, thus potentially enabling them to deliberately reflect on the event while incorporating and assimilating new information about the self and others to regain meaning, restore self-worth and expand their connections and worldviews (Kramer et al., Citation2020; Steinberg et al., Citation2022).

Although the severity of the abuse contributed to PTG in the adolescents here, the moderation analysis indicated that the participants’ self-concept conditioned this contribution. Specifically, the link between the severity of abuse and PTG was significantly positive for survivors with higher overall self-concept. It is possible that when adolescents endure severe abuse, they are compelled to confront the distress it engenders by relying on their self-concept as an internal resource to foster PTG. Thus, a positive self-concept may help adolescents recover from severe trauma. These findings are particularly interesting given previous studies describing the avoidance coping of childhood betrayal trauma survivors, driven by the survivors’ need to maintain a relationship with the abusive caregiver and the completeness of the family (Brooks et al., Citation2019).

Limitations and conclusion

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes establishing causality among the factors contributing to PTG. Furthermore, the small sample size and the use of adolescents’ self-reports in Israeli society limited our ability to draw conclusions. Future work would benefit from incorporating longitudinal investigations, multiple sources of information, and larger sample sizes from diverse cultures to determine whether comparable results can be found.

Despite these limitations, the findings point strongly to the combined contribution of CSA severity, distress symptoms, self-concept, and dissociation to subgroups of adolescent survivors of CSA. These findings highlight the centrality of adolescents’ self-concept in facilitating PTG and should encourage clinicians to work to strengthen this factor. The findings draw attention to the complex interplay between psychological distress and growth after trauma and suggest that clinicians should attend to the ways self-concept, dissociation, and trauma characteristics collectively affect psychological functioning to tailor treatments that facilitate PTG more effectively.

Given that CSA survivors often perceive themselves as passive, helpless, or guilty—hindering disclosure and exacerbating dissociation, fear, and shame—clinical interventions can focus on enhancing positive self-concept through therapeutic practices that reduce dissociation and promote a sense of mastery and growth. In line with this approach, Lev-Wiesel et al. (Citation2022) recommended combining creative art-based and play-based techniques for CSA survivors, especially children and adolescents, to facilitate the shift from a victim identity to a proactive survivor in transformation. According to the authors, engaging in art-making circumvents dissociation, symbolizes growth and action, and enables exploring opportunities and situations to diminish impaired self-sense.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Limor Goldner

Limor Goldner (Ph.D) is an associate professor at the Graduate School of Creative Arts Therapies in the Faculty of Welfare and Health Sciences at the University of Haifa. She serves as the head of the School of Creative Arts Therapies, the director of the Emili Sagol research center, and the laboratory for at-risk children and adolescents. She concentrates on studying children’s emotional and sexual abuse and the recovery process of women who experience gender-based violence and their manifestations in visual art. In the later issues, she published about 60 scientific papers and chapters.

Inbal Leibovich

Inbal Leibovich (Ph.D) is a certified biblio-therapist. She studies the trajectories for post-traumatic growth and recovery among sexually abused children. She devotes her time to providing psychotherapy for children who have been sexually abused under the supervision of Israelis’ welfare services using verbal and non-verbal approaches. She serves as a teaching colleague in the School of Creative Arts Therapies at the University of Haifa, Israel, where she teaches master courses on trauma and the treatment of sexual abuse.

Dana Hadar

Data Hadar (M.A.) is a data scientist with solid statistics, programming, and visualization, implementing machine learning algorithms and traditional Leibovich statistics to solve real-world problems using R, Python, SAS, SQL, and Tableau. She Works at the Emili Sagol research center, the Department of Physiotherapy and Psychotherapy research lab at the University of Haifa, converting research questions into feature engineering, visualization, and modeling using Python pandas and scikit-learn, R, SAS, and Mplus.

Rachel Lev-Wiesel

Rachel Lev-Wiesel, Ph.D. & Professor emerita at the University of Haifa, Head of the National Center for Children at Risk Assessment and Treatment, at the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Treatment and Research, Shamir Hospital. Her primary expertise is child abuse, sexual abuse, trauma and growth, and the use of drawings for assessment and therapeutic purposes. In the later issues, she published about 200 scientific papers and chapters and seven books.

References

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Ed, Text Revision (2022). American Psychiatric Association.

- Arredondo, A. Y., & Caparrós, B. (2021). Posttraumatic cognitions, posttraumatic growth, and personality in university students. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 26(5), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1831812

- Armstrong, J. G., Putnam, F. W., Carlson, E. B., Libero, D. Z., & Smith, S. R. (1997). Development and validation of a measure of adolescent dissociation: The adolescent dissociative experiences scale. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185(8), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199708000-00003

- Asgari, Z., & Naghavi, A. (2020). The experience of adolescents’ post-traumatic growth after sudden loss of father. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2019.1664723

- Atay Turan, S., Sarvan, S., Akcan, A., Guler, E., & Say, B. (2023). Adolescent and young adult survivors of cancer: Relationship between resilience and post-traumatic growth. Current Psychology, 42(29), 25870–25879. https://doi.org/10.1080/10.1007/s12144-022-03649-z

- Badour, C. L., Feldner, M. T., Babson, K. A., Blumenthal, H., & Dutton, C. E. (2013). Disgust, mental contamination, and posttraumatic stress: Unique relations following sexual versus non-sexual assault. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(1), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.11.002

- Bailey, T. D., & Brand, B. L. (2017). Traumatic dissociation: Theory, research, and treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24(2), 170–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12195

- Bakker, M., Veldkamp, C. L., van den Akker, O. R., van Assen, M. A., Crompvoets, E., Ong, H. H., & Wicherts, J. M. (2020). Recommendations in pre-registrations and internal review board proposals promote formal power analyses but do not increase sample size. PLOS One, 15(7), e0236079. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236079

- Barakat, L. P., Alderfer, M. A., & Kazak, A. E. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31(4), 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058

- Basharpoor, S., Mowlaie, M., & Sarafrazi, L. (2021). The relationships of distress tolerance, self-compassion to posttraumatic growth, the mediating role of cognitive fusion. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 30(1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2019.1711279

- Briere, J. (2006). Dissociative symptoms and trauma exposure: Specificity, affect dysregulation and posttraumatic stress. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(2), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000198139.47371.54

- Boals, A. (2023). Illusory posttraumatic growth is common, but genuine posttraumatic growth is rare: A critical review and suggestions for a path forward. Clinical Psychology Review, 103, 102301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102301

- Brooks, M., Graham-Kevan, N., Robinson, S., & Lowe, M. (2019). Trauma characteristics and posttraumatic growth: The mediating role of avoidance coping, intrusive thoughts, and social support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 11(2), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000372

- Černis, E., Evans, R., Ehlers, A., & Freeman, D. (2021). Dissociation in relation to other mental health conditions: An exploration using network analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.023

- Correia-Santos, P., Sousa, B., Martinho, G., Morgado, D., Ford, J. D., Pinto, R. J., & Maia, Â. C. (2022). The psychometric properties of the adolescent dissociative experiences scale (A-DES) in a sample of Portuguese at-risk adolescents. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 23(5), 539–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2022.2064577

- Côté, J. E. (2009). Identity formation and self-development in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Vol. 1. Individual bases of adolescent development. (3rd ed., pp. 266–304). Wiley.

- Cryder, C. H., Kilmer, R. P., Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2006). An exploratory study of posttraumatic growth in children following a natural disaster. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.65

- Currier, J. M., Hermes, S., & Phipps, S. (2009). Brief report: Children’s response to serious illness: Perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(10), 1129–1134. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp021

- Derogatis, L. R. (2000). Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)-18: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. NCS Pearson.

- Elderton, A., Berry, A., & Chan, C. (2017). A systematic review of posttraumatic growth in survivors of interpersonal violence in adulthood. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015611672

- Esnaola, I., Sesé, A., Antonio‐Agirre, I., & Azpiazu, L. (2020). The development of multiple self‐concept dimensions during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 30 Suppl 1(S1), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12451

- Ferragut, M., Ortiz-Tallo, M., & Blanca, M. J. (2022). Prevalence of child sexual abuse in Spain: A representative sample study. Journal of interpersonal violence, 37(21–22), NP19358-NP19377.

- Finkelhor, D., Hamby, S. L., Ormrod, R., & Turner, H. (2005). The juvenile victimization questionnaire: Reliability, validity, and national norms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(4), 383–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.001

- Frazier, P., Conlon, A., & Glaser, T. (2001). Positive and negative life changes following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 1048–1055. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1048

- Frazier, P., Tennen, H., Gavian, M., Park, C., Tomich, P., & Tashiro, T. (2009). Does self-reported posttraumatic growth reflect genuine positive change? Psychological Science, 20(7), 912–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02381.x

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A. (2020). The relationship between child sexual abuse, self-concept and psychopathology: The moderating role of social support and perceived parental quality. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104938

- Gokten, E. S., & Duman, N. S. (2016). Factors influencing the development of psychiatric disorders in the victims of sexual abuse: A study on Turkish children. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.07.022

- Goldner, L., & Berenshtein-Dagan, T. (2016). Adolescents’ true-self behavior and adjustment: The role of family security and satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 62(1), 48–73. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.62.1.0048

- Goldner, L., Lev-Wiesel, R., & Bussakorn, B. (2023). “I’m in a bloody nattle without being able to stop it”: The dissociative experiences of child sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(13–14), 7941–7963. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605231153865

- Goldner, L., Lev-Weisel, R., & Schanan, Y. (2019). Caring about tomorrow: The role of potency, socio-economic status and gender in Israeli adolescents’ academic future orientation. Child Indicators Research, 12(4), 1333–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9587-7

- Govindasamy, P., Green, K. E., & Olmos, A. (2020). Meta-analysis of the factor structure of the brief symptom inventory (BSI-18) using an aggregated co-occurrence matrix approach. Mental Health Review Journal, 25(4), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-05-2020-0028

- Gušić, S., Cardeña, E., Bengtsson, H., & Søndergaard, H. P. (2016). Types of trauma in adolescence and their relation to dissociation: A mixed-methods study. Psychological Trauma: theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 8(5), 568–576. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000099

- Hailes, H. P., Yu, R., Danese, A., & Fazel, S. (2019). Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: an umbrella review. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(10), 830–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30286-X

- Harter, S. (1985). Self-concept Profile for Children: revision of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children Manual. University of Denver.

- Harter, S. (1990). Self and Identity Development. In S. S. Feldman and G. R. Elliott (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent. (pp. 352–387). Harvard University.

- Harter, S. (2012). Emerging self-process during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity. (pp. 680–714). Guilford Press.

- Hébert, M., Collin-Vézina, D., Daigneault, I., Parent, N., & Tremblay, C. (2006). Factors linked to outcomes in sexually abused girls: a regression tree analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(6), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.02.008

- Hetzel, M. D., & McCanne, T. R. (2005). The roles of peritraumatic dissociation, child physical abuse, and child sexual abuse in the development of posttraumatic stress disorder and adult victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(8), 915–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.008

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

- Hodges, M., Godbout, N., Briere, J., Lanktree, C., Gilbert, A., & Kletzka, N. T. (2013). Cumulative trauma and symptom complexity in children: A path analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(11), 891–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.001

- Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., Van De Wiel, M. A., & Zeileis, A. (2006). A lego system for conditional inference. The American Statistician, 60(3), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1198/000313006X118430

- Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., & Zeileis, A. (2006). Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 15(3), 651–674. https://doi.org/10.1198/106186006X133933

- Kaye-Tzadok, A., & Davidson-Arad, B. (2016). Posttraumatic growth among women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: Its relation to cognitive strategies, posttraumatic symptoms, and resilience. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 8(5), 550–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000103

- Keshet, H., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2017). Symptoms and beyond: Self-concept among sexually assaulted women. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 9(5), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000222

- Kim, D. H., Michalopoulos, L. M., & Voisin, D. R. (2021). Validation of the brief symptom inventory–18 among low-income African American adolescents exposed to community violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), NP984–NP1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517738778

- Kilmer, R., P. (2006). Resilience and posttraumatic growth in children. In L.G. Calhoun & R.G. Tedeschi (Eds.,), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice in. (pp. 264–288). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kimhi, S., Eshel, Y., Zysberg, L., & Hantman, S. (2010). Postwar winners and losers in the long run: Determinants of war related stress symptoms and posttraumatic growth. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9183-x

- Kozina, A. (2019). The development of multiple domains of self-concept in late childhood and in early adolescence. Current Psychology, 38(6), 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9690-9

- Kramer, L. B., Whiteman, S. E., Witte, T. K., Silverstein, M. W., & Weathers, F. W. (2020). From trauma to growth: The roles of event centrality, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and deliberate rumination. Traumatology, 26(2), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000214

- Krayer, A., Seddon, D., Robinson, C. A., & Gwilym, H. (2015). The influence of child sexual abuse on the self from adult narrative perspectives. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2015.1001473

- Lahav, Y., Bellin, E. S., & Solomon, Z. (2016). Posttraumatic growth and shattered world assumptions among ex-POWs: The role of dissociation. Psychiatry, 79(4), 418–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2016.1142776

- Lahav, Y., Ginzburg, K., & Spiegel, D. (2020). Post-traumatic growth, dissociation, and sexual revictimization in female childhood sexual abuse survivors. Child Maltreatment, 25(1), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559519856102

- Laufer, A., & Solomon, Z. (2006). Posttraumatic symptoms and posttraumatic growth among Israeli youth exposed to terror incidents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(4), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.4.429

- Lev-Wiesel, R. (2015). Childhood sexual abuse: from conceptualization to treatment. Journal of Trauma & Treatment, 4(4), 2167–1222.

- Lev-Wiesel, R. (2015). Childhood sexual abuse: From conceptualization to treatment. Journal of Trauma & Treatment, 4(4), 2167–1222. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1222.1000259

- Lev-Wiesel, R., Amir, M., & Besser, A. V. I. (2004). Posttraumatic growth among female survivors of childhood sexual abuse in relation to the perpetrator identity. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 10(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020490890606

- Lev-Wiesel, R., Goldner, L., & Daphna-Tekoah, S. (2022). Introduction to the special issue the use of creative art therapies in the prevention, screening, and treatment of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 31(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2022.2032895

- Lev-Wiesel, R., Eisikovits, Z., First, M., Gottfried, R., & Mehlhausen, D. (2018). Prevalence of child maltreatment in Israel: A national epidemiological study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0118-8

- Lev-Wiesel, R., Goldner, L., Malishkevich Haas, R., Hait, A., Frid Gangersky, N., Lahav, L., Weinger, S., & Binson, B. (2023). Adult survivors of child sexual abuse draw and describe their experiences of dissociation. Violence against Women, 10778012231155172, 10778012231155172. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012231155172

- Lo Iacono, L., Trentini, C., & Carola, V. (2021). Psychobiological consequences of childhood sexual abuse: Current knowledge and clinical implications. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15, 771511. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2021.771511/full https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.771511

- Lyssenko, L., Schmahl, C., Bockhacker, L., Vonderlin, R., Bohus, M., & Kleindienst, N. (2018). Dissociation in psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis of studies using the dissociative experiences scale. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17010025

- Maikovich-Fong, A., & Jaffee, S. R. (2010). Sex differences in childhood sexual abuse characteristics and victims’ emotional and behavioral problems: Findings from a national sample of youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(6), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.10.006

- Maercker, A., & Zoellner, T. (2004). The Janus face of self-perceived growth: Toward a two-component model of posttraumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 41–48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20447200

- Marsh, H. W., & Ayotte, V. (2003). Do multiple dimensions of self-concept become more differentiated with age? The differential distinctiveness hypothesis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 687–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.687

- Melamed, D. M., Botting, J., Lofthouse, K., Pass, L., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2024). The relationship between negative self-concept, trauma, and maltreatment in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 27(1), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-024-00472-9

- Meyerson, D. A., Grant, K. E., Carter, J. S., & Kilmer, R. P. (2011). Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 949–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.003

- McElheran, M., Briscoe-Smith, A., Khaylis, A., Westrup, D., Hayward, C., & Gore-Felton, C. (2012). A conceptual model of post-traumatic growth among children and adolescents in the aftermath of sexual abuse. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 25(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.00310.1080/09515070.2012.665225

- Moksnes, U. K., Moljord, I. E., Espnes, G. A., & Byrne, D. G. (2010). The association between stress and emotional states in adolescents: The role of gender and self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 430–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.04.012

- Morris, J. N., Turnbull, D., Martini, A., Preen, D., & Zajac, I. (2020). Coping and its relationship to post-traumatic growth, emotion, and resilience among adolescents and young adults impacted by parental cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 38(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2019.1637384

- Mueller-Pfeiffer, C., Schick, M., Schulte-Vels, T., O’Gorman, R., Michels, L., Martin-Soelch, C., Blair, J. R., Rufer, M., Schnyder, U., Zeffiro, T., & Hasler, G. (2013). Atypical visual processing in posttraumatic stress disorder. NeuroImage. Clinical, 3, 531–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2013.08.009

- Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Fijen, P. (2003). The self-concept profile for children: Further evidence for its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(8), 1791–1802. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00004-7

- Nijenhuis, E. R., & Van der Hart, O. (2011). Dissociation in trauma: A new definition and comparison with previous formulations. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation, 12(4), 416–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2011.570592

- Parker, A. K. (2010). A longitudinal investigation of young adolescents’ self-concepts in the middle grades. RMLE Online, 33(10), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2010.11462073

- Pereda, N., Guilera, G., Forns, M., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2009). The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007

- Pereda, N., Gallardo-Pujol, D., & Guilera, G. (2018). Good practices in the assessment of victimization: The Spanish adaptation of the juvenile victimization questionnaire. Psychology of Violence, 8(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000075

- Phipps, S., Long, A. M., & Ogden, J. (2007). Benefit finding scale for children: Preliminary findings from a childhood cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(10), 1264–1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsl052

- Powers, A., & Casey, B. J. (2015). The adolescent brain and the emergence and peak of psychopathology. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 14(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2015.1004889

- Richardson Gibson, L. M., & Parker, V. (2003). Inner resources as predictors of psychological well-being in middle-income African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Control: journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center, 10(5 Suppl), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327480301005s08

- Sagar, R., & Choudhary, V. (2024). Toward the rainbow after the storm: Post-traumatic growth in children surviving sexual abuse. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19(3), 253-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/09731342231215645

- Schubert, C. F., Schmidt, U., & Rosner, R. (2016). Posttraumatic growth in populations with posttraumatic stress disorder—A systematic review on growth‐related psychological constructs and biological variables. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 23(6), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1985

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & De Dassel, T. (2009). Exploring posttraumatic outcomes as a function of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 18(6), 623–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538710903317224

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Lurie-Beck, J. (2014). A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(2), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.10.005

- Sledjeski, E. M., Dierker, L. C., Brigham, R., & Breslin, E. (2008). The use of risk assessment to predict recurrent maltreatment: A classification and regression tree analysis (CART). Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 9(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-007-0079-0

- Steinberg, L. (2013). Adolescence. (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Steinberg, M. H., Bellet, B. W., McNally, R. J., & Boals, A. (2022). Resolving the paradox of posttraumatic growth and event centrality in trauma survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(2), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-00980-2

- Stoltenborgh, M., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Euser, E., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. (2011). A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment, 16(2), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511403920

- Strasser, H., & Weber, C. (1999). On the Asymptotic Theory of Permutation Statistics. Math. Meth. Stat., 2 (1999). (pp. 220-2500).

- Strobl, C., Malley, J., & Tutz, G. (2009). An introduction to recursive partitioning: Rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 323–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016973

- Sultana Eliav, A., & Lahav, Y. (2023). Posttraumatic Growth, Dissociation and Identification With The Aggressor Among Childhood Abuse Survivors. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 24(3), 410–425.

- Taku, K., Kilmer, R. P., Cann, A., Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2012). Exploring posttraumatic growth in Japanese youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(4), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024363

- Tang, W., Wang, Y., Lu, L., Lu, Y., & Xu, J. (2021). Post-traumatic growth among 5195 adolescents at 8.5 years after exposure to the Wenchuan earthquake: Roles of post-traumatic stress disorder and self-esteem. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(13), 2450–2459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320913947

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1995). Trauma and transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. SAGE Publications.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02103658

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Moore, B. A. (2021). Posttraumatic growth as an integrative therapeutic philosophy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 31(2), 180.

- Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., & Ormrod, R. (2010). The effects of adolescent victimization on self-concept and depressive symptoms. Child Maltreatment, 15(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559509349444

- Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., Finkelhor, D., & Hamby, S. (2017). Effects of poly-victimization on adolescent social support, self-concept, and psychological distress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(5), 755–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515586376

- Vaughn, A. A., Roesch, S. C., & Aldridge, A. A. (2009). Stress-related growth in racial/ethnic minority adolescents: Measurement structure and validity. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(1), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408318775

- Vázquez, C. (2013). A new look at trauma: From vulnerability models to resilience and positive changes. In K. A. Moore, K. Kaniasty, P. Buchwald & A. Sese (Eds.), Stress and Anxiety: Applications to Health and Wellbeing, Work Stressors and Assessment. (pp. 27–40). Logos Verlag.

- Volgin, R. N., Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Shochet, I. M. (2019). Posttraumatic distress, hope, and growth in survivors of commercial sexual exploitation in Nepal. Traumatology, 25(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000174

- Walker-Williams, H. J., Van Eeden, C., & Van der Merwe, K. (2013). Coping behaviour, posttraumatic growth and psychological well-being in women with childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 23(2), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2013.10820622

- Wamser-Nanney, R., Howell, K. H., Schwartz, L. E., & Hasselle, A. J. (2018). The moderating role of trauma type on the relationship between event centrality of the traumatic experience and mental health outcomes. Psychological Trauma: theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 10(5), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000344

- Wright, M. O., Crawford, E., & Sebastian, K. (2007). Positive resolution of childhood sexual abuse experiences: The role of coping, benefit-finding and meaning-making. Journal of Family Violence, 22(7), 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9111-1

- Yin, X., Li, C., & Jiang, S. (2017). The mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship of living environment, anxiety, and depression of underprivileged children: A path analysis in Chinese context. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(7), 941–952. Epub ahead of print 8 November. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317739966

- Zeileis, A., Hothorn, T., & Hornik, K. (2008). Model-based recursive partitioning. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 17(2), 492–514. https://doi.org/10.1198/106186008X319331

- Zhou, X., Wu, X., & Zhen, R. (2018). Self-esteem and hope mediate the relations between social support and post-traumatic stress disorder and growth in adolescents following the Ya’an earthquake. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 31(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1374376