Abstract

We do not know if the delivery of Motivational Interviewing (MI) differs across countries. In an international study targeting Elderly people with Alcohol Use Disorder, The Elderly Study, MI was part of the treatment applied. Treatment delivery was measured by means of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code version 4 (MITI 4). Mixed effects models explored potential differences in delivery of MI between the countries. Delivery of MI differed significantly between participating countries: Denmark, Germany and the US. These findings are important to consider when comparing measures of MI integrity across studies from different cultures.

Introduction

Background

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a communication style and therapeutic approach well recognized across the world. A series of systematic reviews and meta-analysis have proven MI effective in increasing the likelihood of behavior change. These systematic reviews include studies executed in many countries and cultures (Dillard et al., Citation2017; Lundahl et al., Citation2010; Smedslund, Citation2011).

MI has an emphasis on listening to the patient, expressing empathy and understanding, and gently showing the patient what direction of change that she considers being in alignment with her hopes, wishes, and needs. The focus of MI conversation is to bring the motivation within the patient forward, rather than trying to persuade the patient (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2012).

During the last decade, the delivery of MI has been increasingly in focus due to considerable variability in effect sizes of MI across studies (Miller & Moyers, Citation2017). Differences in how MI is implemented is known to occur across study sites, across studies, and both across and within therapists (Hallgren et al., Citation2018; Miller & Rollnick, Citation2014). Furthermore, it has been discussed within the MI-trainer community whether MI is even delivered in the same way in different parts of the world and in different societies.

MI is considered one of the therapies or communication styles that are somewhat easily adapted to other cultures (Oh & Lee, Citation2016). One of the reasons is that some recommendations on how to deliver therapy across cultures are particularly inherent in MI (Asnaani & Hofmann, Citation2012; Satre & Leibowitz, Citation2015). However, we do not know much about whether the interpretation of different aspects of MI within different cultures affects the performance of MI (Lee et al., Citation2015). Often cultural differences, even between Western countries, are left unspoken, and adjustments in delivery of treatment protocols are assumed to follow the provider: therapists will know and act within their own set of cultural norms (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2012).

Despite a series of studies on the delivery of MI having been conducted in some Western countries (Brueck et al., Citation2009; Jamieson et al., Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2015; Lindqvist et al., Citation2017; McCambridge et al., Citation2011; Mesters et al., Citation2017; Osilla et al., Citation2018; Woodin et al., Citation2012), no studies have, so far, investigated if we put emphasis on the same elements of MI when it is delivered in the US and Europe. The studies conducted so far are difficult to compare due to significant variations in study conditions. Therefore, comparisons on how MI is delivered across countries and cultures are hampered by the diversity of studies. Hallgren et al. (Citation2018) found the variability in MI delivery in six American studies was, to a large extent, explained by differences between sessions with the same therapist, but different participants. Even though this could be due to differences within the therapist as well, it is in line with the findings of participant characteristics affecting MI delivery. For instance, participant characteristics like criminal history (Owens et al., Citation2017), severity of addiction (Imel et al., Citation2011), and level of motivation for change (Gibbons et al., Citation2010; Imel et al., Citation2011) have been found to affect how MI is delivered. Thus, in order to attempt to compare the delivery of MI across countries, the therapists in the various nations should, as a minimum, treat individuals with similar characteristics and problems. Additionally, any statistical analysis should seek to adjust for differences in these measures.

Instrument to measure elements of MI

Elements of MI are often measured by the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code (MITI) (Moyers, Citation2010; Moyers et al., Citation2014). The MITI is recently refined to reflect the developments in the theory of MI and to improve reliability of the measures (MITI 4) (Moyers et al., Citation2014). The MITI 4 has been applied in some studies so far supporting the reliability to MI and to some extend the validity (Copeland et al., 2019; Kramer Schmidt, Andersen et al., Citation2019; Moyers et al., Citation2016; Owens et al., Citation2017; Serrano, Citation2018). The MITI 4 provides information on the technical elements of MI by means of a measure of the therapist’s ability to cultivate change talk and soften sustain talk; the relational elements empathy and partnership; in addition, detailed information on MI-adherent therapist behavior (affirmation, seeking collaboration, emphasizing autonomy) and MI-non-adherent therapist adherent (confront and persuade) (Moyers et al., Citation2014) is collected.

The Elderly Study

The Elderly study (Andersen et al., Citation2015, Citation2020) provides the opportunity to study whether MI is delivered differently across three different countries. The Elderly study is an international randomized controlled study of treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), offered to older adults in Germany, the US, and Denmark. In the Elderly study, the communication style was MI, the interventions were manualized, the therapists received the same training, and the same kind of supervision. A strong effort was also made to measure the elements of MI similarly across the sites by training raters in the MITI 4, collectively.

Aim

To investigate if there are differences in the delivery of MI, measured by means of the MITI4, in a study conducted in three countries, in three languages, but with the same inclusion criteria for patients and with similar training of therapists and raters.

Method

Design

In this study, 60+-year-old patients suffering from AUD by The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5) (APA, Citation2013) were offered treatment in an outpatient setting. The participants were randomized to either: (1) a standard treatment with four sessions of Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET), or (2) extended treatment, comprising the same four sessions of MET plus up to eight sessions of Community Reinforcement Approach, adapted to older adults (seniors) (MET + CRA-S). The local ethics committees approved the study. Rationale and further details on the Elderly Study are published in the protocol article: Andersen et al. (Citation2015).

Sample

Participants

Due to differences in how treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder is provided in general in the three countries, participants were recruited differently at the sites. In Denmark, the participants were approached when seeking treatment at three outpatient AUD treatment centers. In Germany, the participants were recruited when seeking treatment for AUD, through a research organized facility offering treatment, through a psychotherapy clinic, and via advertisements. In New Mexico, USA, participants were approached as they entered a primary healthcare center and asked whether they wanted to participate if they screened positive for AUD in a questionnaire.

Inclusion criteria in all three countries were AUD by DSM5 and 60 or more years of age. Exclusion criteria were cognitive deficits (tested by a quiz of questions about the study), current major psychiatric disorder (symptoms of psychosis, mania, severe depression, or suicidal behavior), illicit drug use, under guardianship, and if the participant had received treatment for AUD within the last three months (Andersen et al., Citation2015). Languages accepted in treatment delivery of the study were English and Spanish at the American site, German at the German site, and Danish at the Danish site.

Recordings

At all sites in the three participating countries, all treatment sessions delivered in the Elderly Study were audio-recorded. Between 10 and 20% of the recordings at each site were randomized to assessment for fidelity to MI with the MITI 4 instrument (T. Moyers et al., Citation2014). A subsample of 10–20% of these was randomly drawn to be rated by all raters from the country for inter-rater reliability tests. The raters were blinded as to which sessions were multiply rated.

Procedure

Interventions

The MET sessions were similar to the initial sessions of the COMBINE study (Anton et al., 2006; Miller, Citation1995). MET consists of MI in combination with feedback with emphasis on delivering the feedback in an MI-adherent way, using the feedback to evoke patient change talk and commit to changing behavior (Miller, Citation1995).

The extended intervention (MET + CRA-S) offered an additional up to eight sessions of CRA-S, also carried out once per week. This approach was inspired by the Combined behavioral intervention in the COMBINE study and consisted of a combination of MI, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) (Anton et al., 2006; Meyers et al., Citation2011). The CRA-S comprised five modules with a focus on different coping skills (managing negative moods, coping with cravings and social pressure to drink, help to receiving support from others, finding pleasant and sober activities, and coping with problems related to aging) (Andersen et al., Citation2015). Manuals for both interventions are available online, please see web references.

Training therapists

The therapists were experienced counselors at local treatment centers. Together with the local supervisors, they participated in a four-day training, delivered by an experienced MI-trainer and member of the MINT (Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers). The trainer was also the main author of the treatment manuals for the Elderly Study. The training took place in Denmark and was performed in English. The training was planned as a ‘Train the Trainers’ approach. At the Danish and US sites, all involved therapists participated in the initial four-day training in Denmark. From the German sites, several therapists did not attend the training in Denmark. German therapists attending the initial four-day workshop trained the remaining therapists at the German sites, subsequently.

Regular video meetings between supervisors across all sites of the Elderly Study aligned the supervision given to the therapists throughout the study. Supervision was offered monthly or after every fourth session at meetings with the therapists at each site and was based on randomly chosen recordings of sessions. During the study period, all therapists could approach the local supervisors and ask for feedback on a specific recorded session. All in all, 47 therapists participated in the study: seven in Denmark, three in New Mexico, and 37 in Germany.

Training raters

Aligning the training of raters and their ratings with the MITI 4 across sites was achieved by videoconferencing and co-rating of sessions. This process is described in detail elsewhere (Kramer Schmidt, Andersen et al., Citation2019). Shortly, by means of ten meetings by video and co-rating of 20 recordings in English, training of raters from the local sites took place. The American site was the lead site in this process and was associated with the Center of Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions in New Mexico, US. Meanwhile, local trainings were carried out in Germany and Denmark where teams of raters were trained in the MITI 4 (Kramer Schmidt, Andersen et al., Citation2019). Germany had two rating teams, one in Munich and one in Dresden, and Denmark and New Mexico each had one rating team. All teams applied the English version of the MITI 4, although, at the Danish site, the raters also had a Danish version of MITI 4 available. At the US site, some sessions were performed in Spanish. Since the rater at the US site did not speak Spanish, Spanish sessions, drawn for fidelity assessment, were excluded (n = 16). Therefore, all American recordings in this analysis were performed in English, all German recordings in German and all Danish recordings in Danish.

Inter-rater reliability of the different rating teams was measured by calculating the intraclass correlations coefficient (ICC). The ICC variant applied was based on Hallgren (Citation2012). Accordingly, a two-way model, absolute agreement, average-measure, and mixed-effects ICC was applied. This ICC takes into account systematic divergencies between raters, and assumes agreement based on a calculated average of all raters as the “true measure” (Hallgren, Citation2012). Benchmarks of ICC is 0.00-0.39 = poor, 0.40-0.59 = fair, 0.60-0.74 = good, 0.75-1.00 = excellent (Cicchetti & Sparrow, Citation1981). As low variance in global measures may produce low inter-rater reliability in ICC (Hallgren, Citation2012), the percentage of ratings, where the raters differed by more than one, will also be reported (Kramer Schmidt, Andersen et al., Citation2019). As there was only one rater at the American site, a second rater, associated with the Center of Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions in New Mexico, US, rated some of the tapes to secure reliability.

Measures

Outcome variables

Variables applied in the analysis were elements of MI delivered by the therapists. As mentioned, the use of MI-elements was identified by raters trained in the use of the MITI 4 (Moyers et al., Citation2014). The rater listens to 20-minute sections of the session between therapist and participant. During these 20 minutes the rater assesses quantity and quality of MI-elements defined by the MITI 4; quantity by counting the therapist behaviors like questions, reflections, affirmations, etc. and quality by a global impression of the therapist behavior. The MITI 4 recommends a calculation of summary scores and provides expert recommendations of benchmarks for these summary scores. A list of all MITI 4 measures, including summary scores, is provided in .

Table 1. Description of MITI 4 scores and median values for each country in the Elderly Study.

We included the following outcome variables derived from the MITI 4: (1) the Technical score (average of cultivating change talk + softening sustain talk), (2) the Relational score (average of empathy + partnership), (3) %CR (Percentage of complex reflections of all reflections), (4) R/Q-ratio (reflection to question ratio), (5) MI adherent behavior (affirmations, seeking collaboration, emphasize autonomy), (6) MI non adherent behavior (confront, persuade); additionally, (7) the presence of persuade with permission was explored.

Additional variables

The potential moderating role of participants’ characteristics was explored and controlled for. These were age, gender, severity of alcohol use at baseline, measured by means of Alcohol Dependence Scale (Skinner & Allen, Citation1982), drinks per drinking day (one drink = 12 grams of alcohol) from day 31–60 before baseline, as measured by the Form 90 (Miller & Del Boca, Citation1994), level of motivation for change (measured with a 1–10 visual scale on three areas: importance to change, readiness to change, and confidence to change), level of education, any previous treatment courses, cohabiting or not, and mild to moderate depression measured with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan, Citation1998) (note that participants with severe depression were excluded from the whole study).

Statistics

A linear mixed-effects model was used to model each outcome and estimate associations between outcomes and predictors. Predictors of variance in the outcome variables were the three countries. Data was hierarchically nested by patient and country, and, additionally, country was coded as a dummy variable with Denmark as the base level. This provided insight into the associations of countries adjusted for the moderating variables. 95% confidence intervals were calculated using bootstrapping, since some residuals were non-normally distributed. As larger correlations between variables may disguise moderating effects, variables were tested for multicollinearity prior to the analysis. The analysis was made in R 3.5.1 using package lme4 1.1-19 for fitting mixed-effects models. Differences in demographics were tested by relevant tests (Kruskal Wallis Rank test, Chi-squared tests, Fishers exact tests).

Results

Participants

All in all, 693 participants were enrolled in the Elderly Study. Characteristics of the participants at baseline, presented by country, can be seen in . Despite all of the participants being adults 60 years+, suffering from AUD, seeking treatment, and thus alike, significant differences between countries were found on almost all participant characteristics, except symptoms of depression and number of heavy drinking days prior to treatment. As expected, due to the differences in the recruitment method, the Danish participants stated to be the most motivated measured by means of importance, confidence, and readiness rulers. They also presented a higher percentage of days abstinent prior to inclusion in the study than the participants in Germany, in particular. In Germany, significantly fewer participants had received treatment before, more were cohabiting, and they had lower levels of alcohol dependence severity. The US participants were significantly more educated, and a smaller proportion was retired. At the US site, only, participant ethnicity was registered. Of the 149 participants at the US site, 51 were Hispanics, 9 were Native Americans, and 6 were not specified (missing data on two participants).

Table 2. Baseline demographics by country in the Elderly Study.

Fidelity to MI

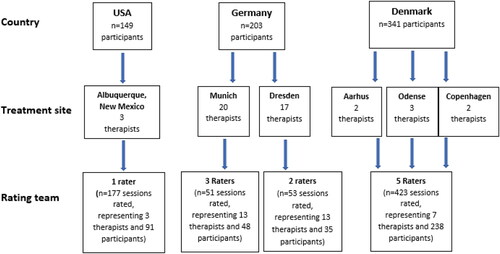

To illustrate how the fidelity assessment was conducted across sites of the Elderly Study, a flow chart of the allocation of participants in each country to number of therapists at each site and, subsequently, which rating team assessed the fidelity to MI, is presented in . Due to the relatively large group of therapists in Germany, only 26 of the 37 therapists were represented in the random measurements. presents median levels of MI-elements in the randomly drawn sessions of the Elderly Study for each country – including summary scores. Since the therapist behavior Confront was only rated once at the US site, and seven times at the Danish site, it was withdrawn from the analysis. Persuade was also quite rare at the US site (rated in six sessions) but sufficiently present in German and Danish ratings to allow for comparisons.

Inter-rater reliability

Interrater reliability by rating team is reported in . Note that there are two rating teams in Germany. The reliability of most measures was good to excellent, but at the US and Munich treatment sites, the reliability of some measures was below fair. However, for global measures and, especially at the US site, although ICC’s were low, percentage of agreement was acceptable in general (). The higher number of raters and multiple rated sessions at the Danish site seems to have disguised a higher level of percentage disagreement between the raters in cultivating change talk.

Table 3. ICCs from the fidelity measurement with MITI 4.2.1 at the four rating teams in the Elderly study.

Table 4. Percentage of agreement on global measures from the fidelity measurement with MITI 4.2.1 from the four rating teams in the Elderly study.

Differences in delivery of MI across countries

Results of the linear mixed-effects model are displayed in . Denmark is the reference site; hence, the outcomes should be interpreted as either rated at the same, higher, or lower level in sessions with a participant with similar characteristics in this country, as in Denmark. Significantly higher levels of relational summary score (coefficient: 0.37 (95% CI: 0.23; 0.5), affirmations (coefficient: 1.51 (95% CI: 1.25; 1.78), seeking collaboration (coefficient: 1.53 (95% CI: 1.17; 1.89), and emphasize autonomy (coefficient: 1.19 (95% CI: 1.01; 1.36) were seen in the US, in addition to a significantly lower levels of the technical score (coefficient: −0.22 (95% CI: −0.37; −0.08), percent complex reflections (coefficient: −0.17 (95% CI: −0.2; −0.14), persuade (coefficient: −0.57 (95% CI: −0.88; −0.26) and persuade with permission (coefficient: −0.36 (95% CI: −0.6; −0.13). Germany was significantly higher on the technical score (coefficient: 0.21 (95% CI: 0.04; 0.37), persuade (coefficient: 0.87 (95% CI: 0.54; 1.24), and persuade with permissions (coefficient: 0.35 (95% CI: 0.09; 0.6), in addition to presenting a significantly lower level of percent complex reflections (coefficient: −0.26 (95% CI: −0.3; −0.23) and reflections to question ratio (coefficient: −0.96 (95% CI: −1.68; −0.24).

Table 5. Results of the mixed effects linear model in the study of differences in delivery of Motivational Interviewing, as measured by the MITI 4 across three countries in the Elderly study.

Discussion

Although the inclusion of participants, training of therapists, supervision, and rating of the sessions were standardized across the three countries in the Elderly Study, and although we additionally controlled for differences between countries on both patient and site level, differences between countries were found in relation to how MI was delivered. Therapists at the US-site had a higher level of relational score and MI-adherent behaviors. German therapists had a higher level of the technical score, lower levels of reflections, and a higher level of MI-non-adherent behaviors. Danish therapists had a higher level of complex reflections, and a lower level of affirmations.

Cultural adaptations typically refer to modifications to the therapeutic treatment to meet the language, norms, and values of participants (Soto et al., Citation2018). In the Elderly study, an effort was made to deliver the same kind of treatment across countries; thus, except for differences in the language delivered, there were no pre-designed cultural adaptations. In line with common MI-practice, therapists should be displaying cultural competences, i.e., being sensitive and performing awareness of the diversity of their patients, including norms, cultural needs, and unique experiences (Soto et al., Citation2018). Hence, the differences between countries in our study might be an expression of the therapists adapting MI in responsiveness to the local participants (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2012). However, since we do not have any information about norms and values among the participants in the Elderly Study, this can only be hypothesized.

Pertaining to the marked differences in settlement history, there is some support for higher levels of individualism in the US, especially western states like New Mexico, compared to Europe (Cohen & Varnum, Citation2016). Thus, the level of individualism could be hypothesized to be higher in the population at the US site in the Elderly Study, which in turn may explain the US therapists displaying a higher level of emphasize autonomy at this site.

Although there are no studies to support this, a plausible explanation on the differences in delivery of affirmations in the three countries might be that affirmations in the two European countries in this study may not be as commonly used in the population in general as in the US. In turn this may be what we found reflected in the MI-delivery. If the German and Danish therapists were, thus, less accustomed to delivering affirmations and other MI adherent behaviors, their delivery of MI adherent behaviors may have been subtler and less recognizable for the raters despite all the attempts to align the ratings across countries. At the Danish site, the raters might have rated this behavior as a complex reflection.

Language and complex reflections

Since language and linguistics are particularly emphasized in MI (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2012), differences in language between the countries in the present study is another plausible explanation for our findings (Imai et al., Citation2016). Questioning conceptual equivalence in the delivery and rating of MI across language and cultural differences, is not new (Brueck et al., Citation2009; Lee et al., Citation2015). The questioning stems from difficulties with reliably rating complex reflections in languages other than English, but this is not supported by our study. Furthermore, the raters’ lack of experience in MI is argued to be a possible explanation (Lee et al., Citation2015). At the Danish site, the rating team consisted of both experienced and inexperienced raters in MI; thus, this combination could have diminished problems with reliably assessing complex reflections. Additionally, problems in measuring elements of MI may arise if the rater and the therapist do not speak the same native language (Kramer Schmidt, Andersen et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2015), which was not the case in the Elderly Study. In our study, the languages English, German, and Danish have the same origin, Germanic, which should result in fewer differences compared to languages with other origins (Imai et al., Citation2016). All in all, we find it unlikely that differences in language explain the differences found in complex reflections.

Overall, Germany accomplished a lower level of fidelity to the MI according to MITI 4, measured by means of summary scores, compared to Denmark and the US. In Germany, 37 therapists delivered the interventions, and at the same time, Germany only included 203 participants in the study. For comparison, the Danish site had 7 therapists and 341 participants. The German therapists, thus, carried out less sessions on average and gained less experience in MI. These findings should be scrutinized for associations with outcomes, as especially MI non adherent behaviors have been indirectly associated with worse outcomes (Magill et al., Citation2018). The question is whether this study has sufficient power as addressed in a recently submitted paper (Kramer Schmidt, Moyers et al., Citation2019).

Implications

This study’s findings have implications for comparisons between MI studies and imply precaution when analyzing associations between fidelity measures and effectiveness. Fidelity to MI varies across sites, across studies (Hallgren et al., Citation2018), and across countries. Meta-analyses indicate that some of the variability in effectiveness of MI between studies may be due to differences in the delivery of active MI-elements (Magill et al., Citation2018; Miller & Rose, Citation2009; Pace et al., Citation2017). Analyses from the Elderly Study do not imply differences in effectiveness due to differences in fidelity to MI (Kramer Schmidt, Moyers et al., Citation2019). It could be that some of the variability in the delivery of MI has consequences for effectiveness of MI; concurrently, some of the variability may be necessary for MI effectiveness for this participant, in this setting, in this language, in this country. The chase for active elements of MI should probably, to a higher extent, consider differences in studies, including participants, language and other settings in their analyses.

Findings of this study, alongside with the lack of variance in effectiveness due to MI fidelity in The Elderly Study (Kramer Schmidt, Moyers et al., Citation2019), also have implications for practitioners and trainers: it emphasizes that MI is adaptable to different countries and languages and that there is room for the practitioner to make use of some MI-elements more than others. Overall, this supports the adaptability of MI to the participant and is in alignment with the discussions in therapy in general about what works for one participant may not work for the other (Norcross & Wampold, Citation2018).

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. Due to language differences, we do not have any measures of inter-rater reliability across sites. The training of raters was carried out at different time-points across sites, and there was no follow-up on reliability between rating teams, based on English practice examples. The rating teams may, thus, have drifted, similar to how individual raters do without regular meetings (Kramer Schmidt, Andersen et al., Citation2019). Differences between countries in the thresholds to rate persuade were noted in the training process (Kramer Schmidt, Andersen et al., Citation2019), but were, at the time, interpreted as differences in interpretation of the tone of voice in the English practice examples used for the training. However, they may as well be a result of differences in thresholds between countries in general.

As there are only a few studies in this field, the patient characteristics that we controlled for in the model were based on hypothesis on possible interactions with the delivery of MI. Other characteristics of the participants, that we did not include, might affect the delivery of MI, for instance religious beliefs and socio-economic status (Cohen & Varnum, Citation2016; Hays, Citation2009; Norcross & Wampold, Citation2018).

The inter-rater reliability of the MITI 4-measures was high at the Danish and German sites, except for the very rare behavior codes, which are known to increase the risk of low inter-rater reliability (Moyers et al., Citation2016). The low levels of inter-rater reliability in general at the US site, decrease the validity of the findings in this study. This could be due to the rating procedure at the US site where the rater, who rated all the sessions at the US site, was checked for reliability by a second rater after the original measurement. Hence, the rater who checked the first rater for reliability did not have project specific training in rating with the MITI 4, and no meetings with the first rater to discuss reliability.

Furthermore, the number of therapists is limited in this study; therefore, these data are not generalizable to the remaining therapists in these countries. Additionally, our information on the therapists was sparse. We do not have information on the 11 therapists not represented in the ratings at the German site. At the US site, one third of the participants labeled themselves Hispanic, and some therapies were conducted in Spanish, but none of these were rated. Therefore, this study only concerns the recordings in English from this site.

Study

The study also has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the delivery of MI to similar target groups across the Atlantic, based on similar training of the therapists and by means of similar treatment protocols. At the same time, the present study explores MI-delivery to an age group of people that are sparsely investigated, while the demand for effective treatments of AUD in this age group is growing (Andersen et al., Citation2015). Additionally, this study provides information on the reliability of the MITI 4 applied to Danish and German populations.

Conclusion

This study found significant and, possibly, clinically relevant differences across Germany, Denmark, and the US in the use of MI-Adherent behaviors and complex reflection in the delivery of MI. Further studies on how MI is delivered differently within the Western cultures may gain knowledge about how therapists adapt and adjust MI to their own culture.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants, therapists and treatment centers involved in the Elderly Study. We are grateful for the huge effort from all rating teams in the Elderly Study. We also wish to thank Christian Sibbersen and Anna Mejldal for their work with the statistics. Thank you, Annemette Munk Svensson, for proofreading this paper. Finally, we wish to thank the Region of Southern Denmark, The Lundbeck foundation, and The University of Southern Denmark for unconditionally funding the study.

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

References

- Andersen, K., Behrendt, S., Bilberg, R., Bogenschutz, M. P., Braun, B., Buehringer, G., Ekstrøm, C. T., Mejldal, A., Petersen, A. H., & Nielsen, A. S. (2020). Evaluation of adding the community reinforcement approach to motivational enhancement therapy for adults aged 60 years and older with DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: A randomised controlled trial. Addiction, 115(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14795

- Andersen, K., Bogenschutz, M. P., Bühringer, G., Behrendt, S., Bilberg, R., Braun, B., Ekstrøm, C. T., Forcehimes, A., Lizarraga, C., Moyers, T. B., & Nielsen, A. S. (2015). Outpatient treatment of alcohol use disorders among subjects 60+ years: Design of a randomized clinical trial conducted in three countries (Elderly Study). BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 280. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0672-x

- Anton, R. F., O’Malley, S. S., Ciraulo, D. A., Cisler, R. A., Couper, D., Donovan, D. M., Gastfriend, D. R., Hosking, J. D., Johnson, B. A., LoCastro, J. S., Longabaugh, R., Mason, B. J., Mattson, M. E., Miller, W. R., Pettinati, H. M., Randall, C. L., Swift, R., Weiss, R. D., Williams, L. D., Zweben, A., & Combine Study Research Group. (2006). Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: The COMBINE study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 295(17), 2003–2017. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.17.2003

- APA. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Association.

- Asnaani, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Collaboration in multicultural therapy: Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance across cultural lines. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21829

- Brueck, R. K., Frick, K., Loessl, B., Kriston, L., Schondelmaier, S., Go, C., Haerter, M., & Berner, M. (2009). Psychometric properties of the German version of the motivational interviewing treatment integrity code. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(1), 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.04.004

- Cicchetti, D. V., & Sparrow, S. A. (1981). Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 86(2), 127–137.

- Cohen, A. B., & Varnum, M. E. (2016). Beyond East vs. West: Social class, region, and religion as forms of culture. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.006

- Copeland, L., Merrett, L., McQuire, C., Grant, A., Gobat, N., Tedstone, S., Playle, R., Channon, S., Sanders, J., Phillips, R., Hunter, B., Brown, A., Fitzsimmons, D., Robling, M., & Paranjothy, S. (2019). The feasibility and acceptability of providing a novel breastfeeding peer-support intervention informed by Motivational Interviewing. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(2), e12703. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12703

- Dillard, P. K., Zuniga, J. A., & Holstad, M. M. (2017). An integrative review of the efficacy of motivational interviewing in HIV management. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(4), 636–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.029

- Gibbons, C. J., Carroll, K. M., Ball, S. A., Nich, C., Frankforter, T. L., & Martino, S. (2010). Community program therapist adherence and competence in a motivational interviewing assessment intake session. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(6), 342–349. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.500437

- Hallgren, K. A. (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023

- Hallgren, K. A., Dembe, A., Pace, B. T., Imel, Z. E., Lee, C. M., & Atkins, D. C. (2018). Variability in motivational interviewing adherence across sessions, providers, sites, and research contexts. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 84, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.10.011

- Hays, P. A. (2009). Integrating evidence-based practice, cognitive-behavior therapy, and multicultural therapy: Ten steps for culturally competent practice. Professional Psychology - Research & Practice, 40(4), 354–360.

- Imai, M., Kanero, J., & Masuda, T. (2016). The relation between language, culture, and thought. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.011

- Imel, Z. E., Baer, J. S., Martino, S., Ball, S. A., & Carroll, K. M. (2011). Mutual influence in therapist competence and adherence to motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(3), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.010

- Jamieson, L., Bradshaw, J., Lawrence, H., Broughton, J., & Venner, K. (2016). Fidelity of motivational interviewing in an early childhood caries intervention involving Indigenous Australian mothers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27(1A), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0036

- Kramer Schmidt, L., Andersen, K., Nielsen, A. S., & Moyers, T. B. (2019). Lessons learned from measuring fidelity with the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code (MITI 4). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 97, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.11.004

- Kramer Schmidt, L., Moyers, T. B., Nielsen, A. S., & Andersen, K. (2019). Is motivational interviewing fidelity associated with alcohol outcomes in treatment seeking 60+ year old citizens? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 101, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.03.004

- Lee, C. S., Tavares, T., Popat-Jain, A., & Naab, P. (2015). Assessing treatment fidelity in a cultural adaptation of motivational interviewing. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 14(2), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2014.973628

- Lindqvist, H., Forsberg, L., Enebrink, P., Andersson, G., & Rosendahl, I. (2017). Relational skills and client language predict outcome in smoking cessation treatment. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1212892

- Lundahl, B. W., Kunz, C., Brownell, C., Tollefson, D., & Burke, B. L. (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(2), 137–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509347850

- Magill, M., Apodaca, T. R., Borsari, B., Gaume, J., Hoadley, A., Gordon, R. E. F., Tonigan, J. S., & Moyers, T. (2018). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing process: Technical, relational, and conditional process models of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(2), 140–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000250

- McCambridge, J., Day, M., Thomas, B. A., & Strang, J. (2011). Fidelity to Motivational Interviewing and subsequent cannabis cessation among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 749–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.002

- Mesters, I., Keulen, H. M. v., de Vries, H., & Brug, J. (2017). Counselor competence for telephone motivation interviewing addressing lifestyle change among Dutch older adults. Evaluation and Program Planning, 65, 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.06.005

- Meyers, R. J., Roozen, H. G., & Smith, J. E. (2011). The community reinforcement approach: an update of the evidence. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(4), 380–388.

- Miller, W. R. (1995). Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. DIANE Publishing.

- Miller, W. R., & Del Boca, F. K. (1994). Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. Supplement, 12, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2014). The effectiveness and ineffectiveness of complex behavioral interventions: Impact of treatment fidelity. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 37(2), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.005

- Miller, W. R., & Moyers, T. B. (2017). Motivational interviewing and the clinical science of Carl Rogers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(8), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000179

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational interviewing. Helping people change (3rd ed., p. 482). Guilford Press.

- Miller, W. R., & Rose, G. S. (2009). Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. The American Psychologist, 64(6), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016830

- Moyers, T. B. (2010). Revised global scales: Motivational interviewing treatment integrity 3.1. 1 (MITI 3.1. 1). Unpublished manuscript, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

- Moyers, T. B., Manuel, J. K., & Ernst, D. (2014). Motivational interviewing treatment integrity coding manual 4.1. Unpublished manual.

- Moyers, T. B., Rowell, L. N., Manuel, J. K., Ernst, D., & Houck, J. M. (2016). The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code (MITI 4): Rationale, preliminary reliability and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.001

- Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

- Oh, H., & Lee, C. (2016). Culture and motivational interviewing. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(11), 1914–1919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.010

- Osilla, K. C., Watkins, K. E., D’Amico, E. J., McCullough, C. M., & Ober, A. J. (2018). Effects of motivational interviewing fidelity on substance use treatment engagement in primary care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 87, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.01.014

- Owens, M. D., Rowell, L. N., & Moyers, T. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity coding system 4.2 with jail inmates. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.04.015

- Pace, B. T., Dembe, A., Soma, C. S., Baldwin, S. A., Atkins, D. C., & Imel, Z. E. (2017). A multivariate meta-analysis of motivational interviewing process and outcome. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(5), 524–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000280

- Satre, D. D., & Leibowitz, A. (2015). Brief alcohol and drug interventions and motivational interviewing for older adults. In Patricia A. Areán (ed.), Treatment of late-life depression, anxiety, trauma, and substance abuse (pp. 163–180). American Psychological Association.

- Serrano, S. E. (2018). Vida PURA: An assessment of the fidelity of promotor-delivered screening and brief intervention to reduce unhealthy alcohol use among Latino day laborers. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 17(4), 519–531.

- Sheehan, D. V. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(SUPPL. 20), 22–33.

- Skinner, H. A., & Allen, B. A. (1982). Alcohol dependence syndrome: Measurement and validation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 91(3), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.91.3.199

- Smedslund, G. (2011). Motivational interviewing for substance abuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (5), 1–130.

- Soto, A., Smith, T. B., Griner, D., Domenech Rodríguez, M., & Bernal, G. (2018). Cultural adaptations and therapist multicultural competence: Two meta-analytic reviews. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1907–1923. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22679

- Woodin, E. M., Sotskova, A., & O'Leary, K. D. (2012). Do motivational interviewing behaviors predict reductions in partner aggression for men and women? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.11.001

Web references

- The Manual for the Extended Condition Motivational Enhancement Therapy with Community Reinforcement Approach (MET + CRA) in the Elderly Study. (2013). https://www.sdu.dk/-/media/files/om_sdu/centre/ucar/materiale/cras+-+community+reinforcement+approach+seniors.pdf?la=da&hash=D45B95B065AA8677747901F2D2AA0032DA1845D3/ Retrieved February 20, 2019 from website at University of Southern Denmark (SDU).

- The Manual for Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) in the Elderly Study. (2013). https://www.sdu.dk/-/media/files/om_sdu/centre/ucar/materiale/cras+-+community+reinforcement+approach+seniors+(standard+version).pdf?la=en&hash=BD6A8F1F10FCC8FBD41E735FDDD49501FAB5761E/ Retrieved February 20, 2019, from website at University of Southern Denmark (SDU).

- The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity coding manual 4.2.1. (2015). Danish version: https://casaa.unm.edu/download/MITI4_2.pdf/ Retrieved February 24, 2019 from CASAA website.