Abstract

This study reviews and synthesizes the literature on Indigenous women who are pregnant/early parenting and using substances in Canada to understand the scope and state of knowledge to inform research with the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg in Manitoba and the development of a pilot Indigenous doula program. A scoping review was performed searching ten relevant databases, including one for gray literature. We analyzed 56 articles/documents. Themes include: (1) cyclical repercussions of state removal of Indigenous children from their families; (2) compounding barriers and inequities; (3) prevalence and different types of substance use; and (4) intervention strategies. Recommendations for future research are identified and discussed.

Introduction

This study was initiated by the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg, Inc. (AHWC) in Manitoba, Canada, to inform a research partnership to develop and pilot an urban Indigenous doula program to improve health outcomes for Indigenous mothers and their babies residing in the city. The research team, consisting of Indigenous and allied scholars, wanted to understand the state and scope of knowledge regarding Indigenous women and substance involvement in pregnancy and early parenting in urban Canadian prairie settings. Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg is the lead partner on She Walks with Me: Supporting Urban Indigenous Expectant Mothers through Culturally Based Doulas, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research-funded research project designed to meet the needs of urban Indigenous expectant mothers by developing and piloting an Indigenous doula service. The research questions posed for this review were co-developed as a research team.

This topic is of profound importance to Indigenous families, as well as health care providers, social workers, policymakers, and community organizations, given the awakening of public consciousness in the era of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the worldwide context (NIMMIWG, Citation2019; TRC, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation2008). Globally, Canada has the second largest Indigenous population proportional to the general population, including distinct First Nations, Métis, and Inuit groups (Dell & Lyons, Citation2007). About half of all Indigenous people in Canada live in cities, and Winnipeg is the city with the most Indigenous people in the country (Dell & Lyons, Citation2007; Statistics Canada, Citation2020). The Indigenous population (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) in Winnipeg is one of the fastest growing demographics, representing 12.2% of the population (Statistics Canada, Citation2017), and this population is younger, with 46% of Indigenous people being 24 or under, compared with only 29% of non-Indigenous people (Statistics Canada, Citation2017). Given their younger population age, higher fertility rates, and health disparities currently experienced, Indigenous women must have access to culturally appropriate maternal and child health services to ensure infants are given the best start in life and to set them on a healthy pathway (Smylie et al., Citation2010).

Indigenous women have traditionally held positions of leadership and honor as life-givers, caregivers, and mentors for their children, families, and communities. Prior to colonization, medicine women of Indigenous nations attended to fertility, pregnancy, childbirth, infant care, bone-setting, and diverse ailments with plethoric strategies embedded within and arising from intimate knowledge of natural processes (Cidro et al., Citation2018; Olson, Citation2013). The patriarchal appropriation of birthing via obstetrics and the brutalizing forces of colonization actively suppressed, villainized, and outlawed these traditional practices for over a century (Couchie & Nabigon, Citation1997; Jasen, Citation1997). As a result, many Indigenous medicine practitioners went underground to preserve their knowledges that today inform a cultural renaissance and revitalization (Cidro et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Couchie & Nabigon, Citation1997; Olson & Couchie, Citation2013). Despite this resurgence, many social, political, legal, jurisdictional, economic, cultural, systemic, and structural barriers limit Indigenous peoples’ access to their own traditional medicines, as well as to biomedical health care (Lavoie, Citation2013; Nguyen et al., Citation2020). This injustice impacts particularly heavily on Indigenous women who have endured poverty, violence, and traumas and who use substances via manifold compounding sites of oppression, often exacerbated by the vulnerabilities of pregnancy and early parenting (Doty-Sweetnam & Morrissette, Citation2018; Niccols et al., Citation2010; Torchalla et al., Citation2014).

Indigenous groups in Canada were first introduced to alcohol in the seventeenth century by European fur traders (Muckle et al., Citation2011). Initially alcohol was only consumed for special festivities, but over time its use—and the use of other introduced substances—became a way for Indigenous people to cope with despair from the destruction of their lands, waters, families, communities, health, autonomy, and whole way of life and to bear the everyday oppression of living under colonization (Muckle et al., Citation2011). From 1884 to 1985, the Indian Act prohibited the sale of alcohol to First Nations people, effectively becoming a tool for policing racial boundaries, boosting sales of black market alcohol, and leading First Nations people to drink more rapidly, outside of licensed establishments and in secrecy (Campbell, Citation2008). Alcohol, smoking, and drug use are now among the most pressing social and health issues in many, though not all, Indigenous populations in Canada (Muckle et al., Citation2011). The First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey, for example, found alcohol and drug abuse to be the most commonly reported community challenge by 80.3% of First Nations adults (FNIGC, Citation2018).

Furthermore, the history of Canada is fraught with destructive policies and legislation, such as the racist-sexist precedents set by the federal constitution’s Indian Act and the assimilative brutality of the Indian Residential School (IRS) system (TRC, Citation2015). The IRS system is now recognized as a particularly devastating weapon of a much larger, centuries-long program of cultural genocide enacted by the Canadian government and Christian missions (TRC, Citation2015). Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes and taken to residential schools where they were subjected to neglect, racism, and all forms of abuses (e.g., physical, verbal, psychological, sexual, cultural, spiritual), which were justified by state mechanisms that labeled Indigenous parents as categorically “unfit parents,” an intensely bitter irony with numerous, ongoing, harmful impacts (TRC, Citation2015, p. 4). This legacy has carried forward, manifesting in high rates of adverse childhood experiences, trauma, violence, mental health issues, substance use, addictions, and cyclical continuations of the same in Indigenous populations (Bombay et al., Citation2020; TRC, Citation2015).

The Sixties Scoop (from the 1950s to 1990s) was another wave of systemic removal of Indigenous children from their families that enacted further damage (Bombay et al., Citation2020; Tait, Citation2009). The child welfare system continues to apprehend Indigenous children today, at an alarming rate of 400 children per year in the province of Manitoba alone, with tremendous negative impacts on racialized Indigenous mothers who fear the colonial system that punishes, rather than supports and uplifts, those living in poverty (CBC, Citation2020; Halprin, Citation2017; Robertson, Citation2019).

There are clinical guidelines, reviews of best practices, harm reduction training guides, conference proceedings, and qualitative meta-synthesis on caring for women who use substances in pregnancy (Marcellus et al., Citation2016; Nathoo et al., Citation2015; NHRC, Citation2020; Sword et al., Citation2009; Wong et al., Citation2017), but there has not been a scholarly review specific to Indigenous women’s substance involvement in pregnancy and early parenting in Canada. Moreover, while there have been reviews on Indigenous culture-as-treatment for substance use (Lavallée, Citation2019; Ritland et al., Citation2020; Rowan et al., Citation2014), none have been specific to pregnancy or early parenting needs beyond smoking cessation (Small et al., Citation2018). This article sets out to address this gap. The research questions guiding the study are: (1) What are the scope and the state of knowledge regarding Indigenous women who use substances in pregnancy, postpartum, and early years of parenting?, (2) What are the best ways to support this population socially, psychologically, and culturally?, and (3) What are some recommendations and areas for future research?

Materials and methods

We followed the Arksey and O’Malley framework for conducting scoping studies with the following process: (1) formulate the research questions, (2) search for relevant literature, (3) choose the most appropriate articles, (4) record their pertinent data in a spreadsheet and a Word document, (5) organize, summarize, analyze, and report on findings, and (6) consult with stakeholders to ensure relevancy (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). This six-step process is a way of mapping and synthesizing a large amount of literature into one useful document (Levac et al., Citation2010). A scoping review is not the same as a technical systematic review; while it is still systematic in nature, it is less resource intensive. Both types of review yield a way of concisely reporting on the literature area to explore viability “either because the potentially relevant literature is thought to be especially vast and diverse … or there is suspicion that not enough literature exists” (Levac et al., Citation2010, p. 2). In the case of our review, both rationales are true. When we tried to limit the scope of our search to only urban settings (cities and towns) in the Canadian Prairies, we found a very limited number of studies. Upon broadening the search to a wider geographical scope, we found a vast number of relevant articles. Therefore, we used the broader search as a stepping-off point while keeping the focus mainly to Canada, except for international studies that incorporated Canada into their analysis or those that focused on the Northern Plains of the United States.

Author 4, a librarian specialist, searched the following databases: Scopus, EbscoHost (CINAHL with full text, Bibliography of Native North Americans, Social Work Abstracts), ProQuest (Sociological Abstracts), PubMed, Web of Science (Web of Science Core Collection, MEDLINE), Google Scholar, and graduate theses and dissertations from the Universities of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Regina, and Saskatchewan. Key search terms were developed for our three main concepts—Indigeneity, mothering/birthing, and substance use—and included ():

Table 1. Literary search categories and terms.

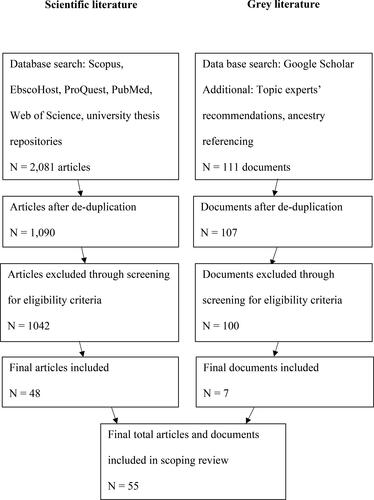

We limited filters to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and United States (known as the CANZUS states) with the publication years between 1995 and 2021, searching in March of 2021. The year 1995 was chosen as the start year because it marks the intended turning point for Indigenous-Canadian relations through the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, which investigated and proposed solutions to improving the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian government and society. Our initial search returned 2,081 articles. The de-duplication of search results was manually completed with the assistance of EndNote X9 software and the method as described in Bramer et al. (Citation2016), which involved exporting references from each database searched. The total number of academic citations after de-duplication was 1,090 journal articles. We conducted an advanced Google Scholar search with the same search terms, and we included the first ten pages of results, equal to the first 100 hits.

Articles were then screened by title and abstract based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010). When it was not immediately obvious if an article was relevant, we looked into the full text to verify (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010). Articles missing any of the main three concepts listed above or from places and dates beyond our scope were excluded; while some excluded articles may contain relevant information, we chose to maintain the focus of the study through strict eligibility criteria (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010). We also cross-referenced our references, requested additional references from topic experts, and performed ancestry referencing (i.e., searching in the reference lists of articles for further relevant reading) (Russell et al., Citation2016). Forty-nine academic journal articles and seven gray literature documents were ultimately included. See for the yield from the literature search. See for a summary of sources included in the analysis.

Table 2. Summary of sources included in the analysis.

Results

We found a wide range of articles in this research, including systematic and scoping reviews, policy and critical analyses, organizational and evaluation reports, graduate theses, book chapters, quantitative trials, and qualitative studies. The study locations with the most publications were Vancouver (n = 6 articles), Sioux Lookout (n = 5 articles), and a cluster of villages in Nunavik (n = 4 articles), in addition to studies that are provincially, nationally, or internationally focused. The main themes that emerged were: (1) cyclical repercussions of state removal of Indigenous children from their families; (2) compounding inequities and barriers faced by Indigenous mothers with substance involvement; (3) prevalence and types of substance use; and (4) intervention strategies being employed to address these issues.

Cyclical repercussions of state removal of indigenous children from their families

This section briefly outlines the literature on how residential schools and child welfare agencies have impacted Indigenous mothers with substance involvement, thus the underlying need for supporting mothers and their infants as inseparable dyads out of racialization and poverty.

Growing up in IRS survivor families

In one study of the Cedar Project in three cities in British Columbia, over 70% of Indigenous women accessing services for substance use in pregnancy had a family history of Indian Residential School (IRS) attendance (Shahram et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017c). Another study of the Cedar Project found that Indigenous women were more likely to attempt suicide if they had a parent who was an IRS survivor or if they had experienced a recent child apprehension, sexual assault, violence, or overdose (Ritland et al., Citation2021). Children of IRS survivors have been disproportionately exposed to mental health problems, suicide, abuse, substance abuse, financial struggles, housing instability, apprehensions, and foster care growing up (Bombay et al., Citation2020; Shahram et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017c). Having experienced apprehension as a child was associated with higher risk of substance use (Shahram et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017c). Having one’s traditional language spoken at home growing up was a protective factor; such Cedar Project participants were less than half as likely to attempt suicide (Ritland et al., Citation2021).

Child apprehension, poverty, and substance use

Findings showed one third of people with substance dependency to be women in their childbearing years and substance use in pregnancy has increased in the general population of Canada, but using substances more often led to apprehension in Indigenous families than non-Indigenous families (Niccols et al., Citation2010). In the Motherisk Drug Testing Laboratory (MDTL) in Toronto between 2005 and 2015, Indigenous women were overrepresented in the drug testing of maternal hair samples, and results were then used against mothers in custody battles with the state (Boyd, Citation2019). It was later found that the test results were not reliable due to lab errors, yet many Indigenous mothers had already lost custody of their children (Boyd, Citation2019). An analysis of this policy found that the “regulation of women, especially poor and racialized women, intersects with the regulation of sexuality, reproduction, mothering, and drug consumption,” and “poverty, rather than illegal drugs, has the most negative impact on fetal health and birth outcomes” (Boyd, Citation2019, p. 17). Legislation and policies that persecute racialized mothers for their poverty have been criticized for punishing women rather than protecting unborn children (Baskin et al., Citation2015).

Child apprehension has been described as very traumatic by both mothers and adult children (Baskin et al., Citation2012; Shahram et al., Citation2017b). Indigenous women in several studies shared negative impacts, noting that the loss of their child was the lowest point of their lives and that they tried harder drugs and/or relapsed the day their child was apprehended (Doty-Sweetnam & Morrissette, Citation2018; Halprin, Citation2017; Niccols et al., Citation2010; Robertson, Citation2019; Wiscombe, Citation2020). Mothers similarly shared feelings of grief, loss, and hopelessness from losing their children and an opening of old wounds from their own childhoods (Boyd, Citation2019; Klaws, Citation2014; Robertson, Citation2019). The power of love for their children was a major motivating factor in reducing and quitting substance use (Doty-Sweetnam & Morrissette, Citation2018; Halprin, Citation2017; Niccols et al., Citation2010; Robertson, Citation2019; Shahram et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017c; Wiscombe, Citation2020). In a study of the destructive impacts of policy and legislation on pregnant and parenting Indigenous women, the most cited reason for successful addiction recovery was the power of loving bonds with children and family (Baskin et al., Citation2015).

Criticisms of the child welfare system

Analysis criticized the child welfare system’s use of risk assessments that highlight Indigenous mothers’ weaknesses instead of their knowledge, strengths, and assets, as well as decontextualize their living environments from their parenting abilities; for example, these agencies employ a questionnaire to assess substance use that serves to build a case against their clients rather than incentivizing disclosure and rewarding help-seeking (Baskin et al., Citation2012, Citation2015). Such assessments have not differentiated between substance use that may impact children in a negative way and substance use for which safe arrangements have been made, equating any amount, frequency, or type of substance use into a form of child abuse and/or maltreatment (Baskin et al., Citation2012, Citation2015). This approach to risk assessment is used despite the fact that many of these same substances are normalized and sanctioned in Canadian settler society for the use of white middle- and upper-class families (Baskin et al., Citation2012, Citation2015).

Mothers are required to hit rapid recovery milestones without support (e.g., finding, getting into, and transitioning out of addictions programs) and with unrealistic expectations that have “excessive focus on compliance regarding case management and child protection standards, which lead to huge administrative requirements and unreasonable demands upon Aboriginal child welfare agencies” (Baskin et al., Citation2015). While the 2011 Commission to Promote Sustainable Child Welfare stated that “compliance measures tell us relatively little about the outcomes for children and families,” compliance assurance is what dominates social workers’ time (Baskin et al., Citation2015, p. 40). Baskin and colleagues argued that, instead of functioning mainly to complete paperwork and perform apprehensions, social work as a profession must shift to address the root causes of inequity that undermine Indigenous mothers’ ability to provide their children with the homes that they envision (Baskin et al., Citation2015).

There are indistinctions and inconsistencies in the literature, thus there is a need to differentiate between terms like substance use, misuse, abuse, addiction, functional addiction, debilitating addiction, medicating, self-medicating, maintaining, substance-dependant, risk, and parenting (Boyd, Citation2019). When there is a lack of clarity in the language, slippery interpretations can mean the difference between a mother keeping or losing custody of her child (Boyd, Citation2019).

Traditional ways

Knowledge Keepers and Elders have shared teachings about treating communities holistically and supporting families as a whole (APTN, Citation2019; Wardman, Citation2014). As reported by the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) (Citation2019): “Our Elders say the most violent act you can do to a mother is to steal away her baby.” Historically, health literature and policy has tended to assume that the needs of the mother and the needs of the child are dichotomous and competing, favoring the latter over the former, but service delivery policy is urgently needed to center the family as a unit (Baskin et al., Citation2015; Shahram et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017c).

Compounding barriers and inequities

This section summarizes studies specific to substance-involved Indigenous mothers’ barriers to care and subsequent morbidity and mortality rates, which suggest the need for addressing the former to improve the latter.

Barriers to care

Indigenous women typically were found to have less access to maternity and infant care, as well as poorer pregnancy outcomes than non-Indigenous women (He et al., Citation2017; Sayers, Citation2009). Indigenous women struggling with addictions often carried untreated trauma and presented with self-censorship and shyness in medical appointments due to low self-esteem, internalized stigma, and lack of trauma-informed, culturally safe care (Doty-Sweetnam & Morrissette, Citation2018). One study on pregnant Indigenous women dealing with substance use demonstrated that the fear of punishment, such as child apprehension, and judgmental attitudes resulted in being four times more likely to receive inadequate prenatal care (Baskin et al., Citation2015; Earle, Citation2018). Indigenous mothers in Manitoba who have previously had a child apprehended are less likely to receive (adequate or any) prenatal care in subsequent pregnancies (Wall-Wieler et al., Citation2019).

Mortality and morbidity rates

Owais and colleagues (Citation2020) authored a systematic review that compared mental health measurements of Indigenous and non-Indigenous women in the perinatal period, finding an increased risk of depression (including postpartum depression), anxiety, and substance misuse in the perinatal period for the former; these findings are telling of the impacts of destructive colonial laws (e.g., land dispossession, leadership disruption, child removal) and increased exposure to violence (e.g., structural, systemic, interpersonal) on Indigenous women. The authors noted that Indigenous women’s resiliency and access to traditional teachings were instrumental in promoting mental health, possibly affecting the results of their meta-analysis (Owais et al., Citation2020). Further, they found persistent methodological problems in the literature, such as the overuse of convenience samples (rather than representative samples) and lack of cultural validity.

A review of Indigenous newborn care reported that the Canadian infant mortality rates for Indigenous infants were double that of the non-Indigenous population, which was partially linked to higher rates of preterm births and congenital abnormalities related to a variety of socioeconomic factors including substance use (Sayers, Citation2009). A study conducted in North Dakota found Indigenous infant mortality rates to be 3.5 times higher than mortality rates for white infants, with greater disparities related to inadequate prenatal care and illicit drug use in pregnancy (Danielson et al., Citation2018).

Prevalence and types of substances

This section reports on which types of substances have been studied specific to Indigenous mothers, as well as prevalence per study samples.

Prescription opioids

Between 1991 and 2007 in Ontario, oxycodone prescriptions increased by 850% (Kanate et al., Citation2015). Several studies reported on disproportionately high rates of prescription opioid (PO)-exposed pregnancies with complications in First Nations in northern Ontario (Russell et al., Citation2016; SLFNHA, Citation2017). Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority (SLFNHA) published a research compilation, finding that their region’s pregnancies with PO exposure (mostly oxycodone) doubled from 13% in 2009 to 26% in 2014 (with the highest rates in teenage mothers), which in turn increased Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) rates (Russell et al., Citation2016; SLFNHA, Citation2017). Mothers using opioids were more likely also to drink alcohol, smoke tobacco, and deliver prematurely (Kelly et al., Citation2011). Almost 30% of infants exposed to opioids had NAS, but with daily exposure, rates went up to 66%; more severe NAS infants were more likely to require intensive nursing and to stay in the hospital for longer (Kelly et al., Citation2011). In 2014, the findings of Kelly and colleagues agreed that opioid drug use in pregnancy for First Nations women in the SLFNHA catchment area had risen (to 28.6% of all births) and that some improvements in neonatal outcomes were due to an opioid substitution and tapering program.

Alcohol

Population comparisons. One study found 10% of pregnant women in the general population of Canada drink some amount of alcohol, with 3% engaging in binge drinking (Popova et al., Citation2017). Indigenous people were found to drink at rates four times higher, with 20% engaging in binge drinking (Popova et al., Citation2017); however, data accuracy can vary widely depending on degree of community engagement, geographical differences, cultural group specificity, and age- and gender-stratified data. Ye et al. (Citation2020) studied prenatal drinking in the Northern Plains, USA, showing that more white women drank during pregnancy but more Indigenous women binge drank, especially in the first trimester. A South Dakota study found a lower alcohol consumption rate among American Indian women before pregnancy than their white counterparts, with no differences found in rates of relapse or of drinking during pregnancy (Specker et al., Citation2018). Inuit-specific. We reviewed four articles that provide prevalence data on alcohol use during pregnancy for the Inuit population living in what is now Canada. Studies found that 73-75% of Inuit women drank (any amount) and 54% binge drank in the year pre-conception, dropping to 60-62% during pregnancy and 62% and 33%, respectively, after delivery (Fortin et al., Citation2016; Muckle et al., Citation2011). Those who binge drank during pregnancy represent a subset with the following associations: younger age at introduction to alcohol, more frequent drinking, heavier drinking, more cigarette use, more marijuana use, some use of cocaine and solvents before pregnancy, depression and distress in the postnatal year, past suicide attempt(s), and more verbal aggression in intimate partnerships, when compared to those who abstained (Muckle et al., Citation2011). Fraser et al. (Citation2012) concluded that any amount of binge drinking in the study participants was associated with restricted growth in pregnancy and poorer visual acuity in infants at six months postpartum. Those coupled with a partner and those not using marijuana were more likely to reduce binge drinking at conception (Fortin et al., Citation2016). Fortin et al. (Citation2017) noted that self-reported alcohol use rates were higher when Inuit women were interviewed during pregnancy compared to retrospectively, suggesting recall bias may have been a limitation.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) is the most serious manifestation of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) (Banerji & Shah, Citation2017). A meta-analysis described the prevalence of FAS and FASD among Indigenous people in Canada at 38 times and 16 times higher, respectively, than the generally population; however, this analysis remains controversial in the literature as some scholars argue studies have been methodologically flawed and that no clear evidence differentiates rates adequately (Baskin et al., Citation2015).

Health risks have become better known since the 1990s with researchers pushing for more recognition of FASD as a health crisis and calling for more services for Indigenous communities with limited funding and no national strategy. Instead, public health messaging and growing public concern fed into discrimination against Indigenous mothers (Tait, Citation2014). A landmark Supreme Court case ruled that a pregnant First Nations woman in Winnipeg could not be mandated into addiction treatment and detainment, a policy response used elsewhere (e.g., some states in the US) (Tait, Citation2014). Critical analysis of the history and politics suggested that FASD diagnosis is meaningless without supports, services, and education in place (Banerji & Shah, Citation2017; Halprin, Citation2017; Symons et al., Citation2018; Tait, Citation2014; Tough et al., Citation2007). Cox (Citation2015) wrote a book entitled FASD in a Canadian Aboriginal Community Context: An Exploration of Some Ethical Issues Involving the Access to FASD Service Delivery on the topic.

Tobacco

Heaman and Chalmers (Citation2005) found that 61% of Indigenous women in Manitoba smoked in pregnancy compared to 26% of non-Indigenous women and that this was associated with inadequate prenatal care, lack of social support, being single parents, and using illicit drugs.

A study in South Dakota found overall smoking rates to be similar between Indigenous and white mothers before and during pregnancy, with Indigenous women less likely to smoke more than six cigarettes per day and more likely to quit (Specker et al., Citation2018).

Maternal smoking was associated with low breastfeeding rates among the James Bay Cree women in Northern Ontario (Black et al., Citation2008). Maternal smoking is a risk factor for childhood lung diseases and childhood dental decay, particularly important to Indigenous children who are disproportionately affected in Canada (Baghdadi, Citation2016; Redding & Byrnes, Citation2009).

Cannabis, volatile solvents, cocaine, and methamphetamines

There are large gaps in the literature regarding cannabis use in pregnancy in general. In one study of Inuit, 80% of women reported using marijuana before pregnancy, and 36% were using during pregnancy on an average of twice per week (Muckle et al., Citation2011). The same study showed that 62% of women had, at some point in their lives, inhaled solvents (mostly glue, gas, or nail polish remover), 25% had snorted cocaine, and 5.6% had used other illegal drugs; however, other than marijuana, illicit drugs were rarely used during pregnancy (Muckle et al., Citation2011). There were few studies on methamphetamines in pregnancy for the general population, and these were focused on health risks to the mother and fetus or management of labor and delivery (Knight, Citation2021; Pham et al., Citation2021; Premchit et al., Citation2021). We found no studies specific to Indigenous mothers’ use of methamphetamines nor any specific to First Nations or Métis mothers’ use of solvents, cocaine, or other street drugs; therefore, there are large gaps in this research area.

Intervention strategies

This section describes some of the successes, nuances, and lessons learned regarding intervention strategies for helping Indigenous pregnant and parenting women with different types of substance involvement, indicating the need for trauma-informed, culturally safe, holistic supports overall.

Smoking cessation

A large proportion of the initial search results focus on tobacco smoking cessation programs for Australian Indigenous mothers, which we did not include in the review and do not detail here. Small and colleagues (Citation2018) published a systematic review of the experiences and cessation needs of Indigenous women globally who smoke during pregnancy. Indigenous women were often motivated to quit for their own and their babies’ health, because they felt physically ill from the smell of smoke, and due to social pressure; yet barriers to quitting included chemical dependency, lack of programs, lack of social support, and misinformation about risks (Small et al., Citation2018). Stevenson and colleagues (Citation2017) authored a systematic review on Indigenous families establishing smoke-free homes in the CANZUS countries. Recommendations included: mobilizing community champions, role models, and coaches; engaging community members to develop smoke-free spaces and messaging; enhancing self- and collective efficacy; addressing communities as a whole; and strategizing solutions to interpersonal tensions within and between smoke-free households and people who smoke, understanding the central importance of relationships (Stevenson et al., Citation2017).

In a narrative review of CANZUS countries, Gould et al. (Citation2017) observed socially normalized Indigenous tobacco use, as well as socioeconomic disparities, to be barriers to quitting in pregnancy, and they pointed to the important traditional role of Elders as role models and mentors. Traditional First Nations teachings, for example, hold tobacco as sacred, and it is used regularly in ceremony and relationship building (Baskin et al., Citation2015). Community health interventions have sometimes argued that traditional forms do not have the thousands of chemical additives now found in commercial tobacco; further, the smoke is traditionally used more as a smudge and carrier of prayers than an inhalant (Baskin et al., Citation2015).

Prescription opioid treatment

Russell and colleagues (2016) wrote a narrative review on prescription opioid prescribing, use/misuse, harms, and treatment among Indigenous people in Canada, reporting on a pilot program with a subset of pregnant participants (Russell et al., Citation2016). Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win, an Indigenous-focused health center in northwest Ontario, piloted an opioid-tapering program for pregnant women and found Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome to decrease from 30% in 2010 to 18% in 2013 while these rates otherwise increased overall (Russell et al., Citation2016). Russell and colleagues (Citation2016) reported that half of the 166 opioid-using First Nations women at the health center opted to participate, with 9% quitting completely and 83% decreasing their dose by the time of the birth. Similar programs have since been implemented in sixteen of thirty surrounding First Nations communities (Russell et al., Citation2016).

Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win published a research compilation that includes guidelines on safe use of long-acting morphine, buprenorphine, and/or naloxone for treating opioid dependence in pregnancy; maternal and fetal monitoring protocols; and interactions with Type 2 diabetes (Dooley et al., Citation2015; SLFNHA, Citation2017). Notable findings include discovering that, with buprenorphine-naloxone treatment, pregnant First Nations women are able to cease opioid use and infants had healthier birth weights (SLFNHA, Citation2017). Another study demonstrated that, with the implementation of a prenatal urine drug screening protocol, more First Nations women opted to screen, test positivity rates increased, and more patients discontinued opioid use in pregnancy (SLFNHA, Citation2017).

A study conducted in northwest Ontario evaluated a series of multidisciplinary stakeholder workshops to discuss best practices within the local Indigenous context and to develop consensus statements on transitions in care, access to buprenorphine treatment, stable funding for addiction programs, and Indigenous-led services (Jumah et al., Citation2018). Professionals from health, social, and education sectors, together with community organizations, called for:

A national strategy to address the effects of opioid use in pregnancy from a culturally safe, trauma-informed perspective that takes into account the health and well-being of the woman, her infant, her family and her community. (Jumah et al., Citation2018, p. 616)

Psychosocial support

Indigenous women with substance use disorder in Manitoba have informed qualitative researchers that friends and family can be helpful (e.g., role modeling, mentoring, source of strength and inspiration) or detrimental (e.g., asking them to party, using substances in their presence) to their efforts to reduce or quit (Doty-Sweetnam & Morrissette, Citation2018; Halprin, Citation2017). Pregnant Indigenous women in Winnipeg felt judged by peers both for using drugs and alcohol, but also for not using, in social settings, so developing skills and strategies for coping with both types of social stigma are needed (Halprin, Citation2017). Interventions that used an approach that is woman-centered and respectful of a woman’s right to self-determination have been linked to greater program engagement, thus reducing drug and/or alcohol exposure in pregnancy; when women felt more supported and empowered, there was more overall improvement in social and health outcomes (Halprin, Citation2017).

In a review of addictions treatment issues for Indigenous women, Niccols and colleagues (Citation2010) studied six of the fifty National Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program centers in Canada, which are largely run by First Nations community organizations. Interviews with clients and staff identified key elements helpful in this work, such as acknowledging the impact of trauma (e.g., colonialism, interpersonal violence); providing empathy (e.g., grieving loss of child custody); supporting Indigenous spiritualities, cultures, medicines, and teachings; positive role modeling; open, accepting, nonjudgmental communication (e.g., realities of sex work, mothering); and developing healthier relationships and parenting skills (Niccols et al., Citation2010).

Culturally safe midwifery care

A thesis on decolonizing midwifery in Winnipeg’s inner-city neighborhoods, where the highest proportion of substance-involved urban Indigenous women live, recommended increasing cultural safety through providing access to smudging, holding sharing circles, incorporating the Anishnaabeg Seven Sacred Teachings, promoting cultural events, making the clinic feel more homey, creating pamphlets and posters on Indigenous midwifery, and ensuring time for relationship- and trust-building in appointments (Wiscombe, Citation2020).

Peer support

One report on recommendations from five tribes in Minnesota recommended peer support as a community-based intervention. Indigenous people with lived experience are hired as peer recovery coaches, including the certification of doulas as peer recovery specialists (Earle, Citation2018).

Trauma-informed vs. trauma-specific

A study on pregnant and parenting women who have experienced trauma, violence, and addiction in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, using a 48% Indigenous sample, stressed the differentiation of and need for both trauma-informed and trauma-specific services (Torchalla et al., Citation2014). Services that are trauma-informed understand the impact of trauma on development and substance use but do not require client disclosure (Torchalla et al., Citation2014). Services that are trauma-specific directly address trauma and seek to facilitate recovery (Torchalla et al., Citation2014). Trauma-informed care was accessible for women who may not have had the capacity, supports, or resources to address the source of their pain (Torchalla et al., Citation2014).

Family-centered, wrap-around, and holistic approaches

Ritland and colleagues (Citation2020) published a scoping review on culturally safe parenting programs for Indigenous families impacted by substance use, finding pregnancy to be a key time for optimizing intervention efficacy. McCalman and colleagues (Citation2017) wrote a scoping review to examine family-centered interventions by primary health care providers for Indigenous early childhood wellbeing in the CANZUS states. This review found improvements in Indigenous children’s health (e.g., birthweights, weight gain, emotional health, behavior, home safety, vaccinations, and screening rates) and parents’ health (e.g., lower depression, lower substance use, better parenting confidence, involvement, and skills), as well as access to and retention of care (McCalman et al., Citation2017).

Numerous studies concluded that it is crucial to reduce barriers to services, with one approach being the provision of multiple services (e.g., mental health assessment, addictions counseling, prenatal and medical care, education and employment training, housing connections, parenting supports) in one location (Earle, Citation2018; Kashak, Citation2015; Niccols et al., Citation2010, Citation2012; Robertson, Citation2019; Sword et al., Citation2009). In addition to reducing barriers, wrap-around services can provide multiple treatment pathways suited to the preferences and needs of individuals (Earle, Citation2018). Shahram et al. (Citation2017a) reviewed best practices for programs for pregnant and early-parenting women who use substances and found that single-access sites, outreach, harm reduction, cultural safety, nurturing mother-and-child together, and building partnerships are imperative for successful service delivery. In 2004, the United Nations had already concluded that there is a need for coordination services (e.g., substance use treatment, prenatal care, child welfare) at a single site (Niccols et al., Citation2010). Exemplary programs that provide several supports holistically under one roof include Sheway (Vancouver, BC), Toronto Centre for Substance Use in Pregnancy (ON), the Maxine Wright Community Health Centre (Surrey, BC), and New Choices (Hamilton, ON) (Kashak, Citation2015; Niccols et al., Citation2010).

Marcellus (Citation2017) studied a program in Vancouver that integrates practical pregnancy and parenting support, health care, and counseling for mothers who use substances within a woman-centered, trauma-informed, harm reduction, and culturally safe model of care. With a sample that was just over one third Indigenous, participants stressed the need for more long-term solutions around health, social, and recovery services to address underlying determinants of health (e.g., gender, housing, income) using a strengths-based approach (Marcellus, Citation2017).

Parenting programs were found to be an important aspect of holistic care, with one model being the Parent Child Assistance Program (PCAP) used by InSight, an existing mentorship program for Indigenous pregnant and early-parenting women who use substances in Winnipeg (Halprin, Citation2017). Notably, InSight is provided by the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre, the partner who requested this scoping review. PCAP employs a long-term focus on improving social determinants of health (Halprin, Citation2017). PCAP has been shown to help women to access, choose, and properly use birth control, access addiction treatment and health care, reduce substance use, and lengthen periods of sobriety (Halprin, Citation2017). Of those who completed the program in one study at InSight, 73% went on to have alcohol-free pregnancies (Halprin, Citation2017). A study in six rural and remote First Nations communities in Alberta found a three-year-long, PCAP, relationship-based, trauma-informed home visitation service to be culturally safe, well-received, and positively impactful (Pei et al., Citation2019). Further, when women had their children stay with them in addictions treatment facilities, it increased the likelihood of their program completion (Kashak, Citation2015).

Harm reduction

Harm reduction can be defined as policies, programs, and practices that aim to minimize the negative health, social, and economic impacts of substance use, employing a nonjudgmental approach to “meet people where they are at” rather than insist on abstinence for access to services (Dell & Lyons, Citation2007). In a study on alcohol and drug use of pregnant women in Winnipeg, Halprin (Citation2017) found the harm reduction model to be a good fit with expecting Indigenous women who use substances (Halprin, Citation2017). Harm reduction approaches have shown greater participant engagement because focusing on the woman’s health communicates vital messages that she matters, she is cared for, and she is deserving of respect (Halprin, Citation2017). Harm reduction has been a pragmatic way to slow the spread of sexually transmitted infections in these communities. The All Nations Hope AIDS Network in Saskatchewan, for example, included harm reduction services specific to women in their childbearing years (Dell & Lyons, Citation2007; Wardman, Citation2014).

Harm reduction services have improved access to prenatal care for Indigenous women who use drugs (e.g., Healthy, Empowered and Resilient Pregnancy Program in Edmonton, Manito Ikwe Kagiikwe [The Mothering Project] in Winnipeg) (Wall-Wieler et al., Citation2019). These services enhanced outreach, access to, and retention for prenatal care through cultural safety, mother-and-child togetherness, and practical supports (e.g., food vouchers, housing supports, bus tickets) (Marcellus et al., Citation2016; Nathoo et al., Citation2015; Wall-Wieler et al., Citation2019).

Traditional healing

In a review of treatment issues for Indigenous mothers who use substances, authors found that supporting women in reclaiming their identity through traditional ceremony, arts, healing, teachings, and other cultural experiences were key to recovering (Niccols et al., Citation2010). A report from Minnesota that interviewed five tribal communities supports these findings and recommends that culture form the center of perinatal programs for substance users (Earle, Citation2018). Nevertheless, there is at times a tension between traditional healing and harm reduction principles, as the former often requires abstinence for sacred ceremonies while the latter accepts substance use as a fact of life, and substance users can feel shamed about not being pure enough to engage in ceremony (Cidro et al., Citation2021; Dell & Lyons, Citation2007; Earle, Citation2018). Traditional healing starts with spirit rather than the physical (Wardman, Citation2014), and, as noted by Dell and Lyons (Citation2007), “For some, Aboriginal traditions, customs, and cultural ways are incompatible with the use of mood-altering substances,” and “Individuals who use substances such as alcohol or methadone are viewed as being ‘out of balance” (p. 3).

Having said this, traditional culture and harm reduction also have overlapping principles, such as preferring a holistic approach, carrying respect and nonjudgment, building up community support, recognizing gifts and strengths, promoting autonomy and empowerment, and understanding socioeconomic limitations (Wardman, Citation2014). Further, both methods understand the role of colonialism and trauma in substance use (Wardman, Citation2014). There are examples of culturally safe, harm reduction services that employ traditional healing, such as Insite (Vancouver, BC), the Western Aboriginal Harm Reduction Society (Vancouver, BC), and Blood Ties Four Directions Centre (Whitehorse, Yukon) (Wardman, Citation2014).

Discussion

Most of the journal articles and the gray literature reports that we reviewed provide recommendations for services, policy, and research. This section briefly highlights the themes that emerged from the recommendations made in the collective literature.

Recommendations

A major theme is the need for responsive programs. We found many recommendations for increased supports and funding for services that include those that are: urban Indigenous-specific; trauma-informed; women-centered; family-inclusive; culturally safe; integrative of traditional healing; holistic and wrap-around; and community-based. Additionally, there are calls for more substance use prevention and education; addictions interventions and counseling; attention to housing and food needs; parenting and life skills training; treatment options ranging from harm reduction to abstinence; and all-in-one accessible locations. These findings will inform the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre’s (AHWC) development of an Indigenous doula service model in Winnipeg by pointing to potential organizations to be consulted in how best to support Indigenous birthing people who use substances, including Insite, Sheway, Meno Ya Win Health Centre, and Blood Ties Four Directions Centre. As the AHWC InSight program was noted in the literature as a strong example of using harm reduction and a social determinants of health lens in addressing substance use, the pilot doula service will work closely with this existing program to coordinate harm reduction services and ensure the doulas are trained in the methods used by InSight workers.

Another theme was that of decision-making power. We found recommendations that all levels of governments improve outcomes through engaging directly with Indigenous women’s organizations to return decision-making power and resources to traditional forms of self-governance and to work in the spirit of collaboration rather than authoritarianism. This approach is key to developing and evaluating effective programs, services, and policies for pregnant and birthing Indigenous people. The pilot doula program at AHWC, which is governed by community-based Indigenous service providers, already works in collaboration with their clients and other service providers in Winnipeg but will work to expand and reinforce their networks to include local Indigenous doulas and midwives and partner initiatives/agencies like Manito Ikwe Kagiikwe (The Mothering Project) at Mount Carmel Clinic, as well as researchers and practitioners working on substance use among pregnant and birthing people within the Winnipeg context such as the interprofessional Maternal and Perinatal group for Leveraging Empowerment & Services (iMAPLES).

Furthermore, the literature calls for funding, legislation, and policies to shift by addressing children’s protection needs within the context of family as an inseparable whole. Those struggling with addictions, health providers, social workers, and addictions treatment professionals need more supportive policies with realistic timelines for recovery programming in recognition that healing is not a linear or rapid process. Strong leadership and resources are needed to promote public consciousness and to combat racism, violence, and discrimination against Indigenous women and girls who live in high-risk environments. This finding can inform all levels of government in seeking solutions for these pressing health and social issues.

The gaps in the reviewed literature regarding the specific training needed to support Indigenous birthing people through their perinatal experience while using substances, especially in the context of birth workers/doulas, demonstrates a need for research that connects the use of Indigenous doulas with impacts on substance use for Indigenous birthing people and their families. Based on this scoping review, the doulas within the AHWC program will need to be highly trained in cultural safety, harm reduction, trauma-informed care, and how to negotiate potential child apprehension scenarios. Of particular interest to the pilot development is the 2018 report by Earle, which explicitly recommended certifying doulas as peer recovery specialists and pointed to the success of the Family Spirit home-visiting model in relapse prevention (Earle, Citation2018). It is also possible that we may need to look to existing research on other historically excluded birthing people, including non-Indigenous people of color, and their community-based doula programs/training/research. Moreover, there are additional areas of research to be conducted as outlined in the following section.

Areas for future research

Comprehensive data on substance use in Indigenous populations in Canada are still needed to make up for jurisdictional complexities and exclusions. Research needs to attend to gendered, cultural, and geographical differences, as there is a scarcity, for example, in Métis-, Inuit-, and community-specific knowledge. Going forward, research needs to transcend the deficit discourses and unhelpful comparisons while still attending to important distinctions and inequities. Indigenous groups often already know the descriptive statistics and would prefer solution-focused research.

As such, future research can include family-based addictions intervention implementation studies, transformative studies that provide immediate benefits, and vision development for Indigenous women’s organizations. Research is needed to understand mechanisms, such as advisory councils, that could enable Indigenous women’s involvement in service planning and evaluation, as well as in progressing understandings of gender-aware, culturally safe methodologies. While there is a movement of culture-based and land-based addictions recovery and healing, we found remarkably little in the literature (Niccols et al., Citation2010) specific to Indigenous women in pregnancy and early parenting in this regard. Further, though important connections have been made between trauma, mental health, and substance use, more research is needed on best practices to support Indigenous women in pregnancy and parenting while dealing with multiple oppressions.

Conclusion

This scoping review aims to understand the state of literature about Indigenous women who use substances in pregnancy and early parenting, as well as how to best support healing and recovery, with a special emphasis on Manitoba, Canada. We found several fundamental commonalities: the intimate connections between suffering colonization, child apprehensions, poverty, and substance use; the gendered impacts of institutionalized racism on the vibrancy of Indigenous families; the intersectional barriers that prevent substance-involved Indigenous women from accessing help and the resultant health inequities for them and their children; the lack of a clear and comprehensive epidemiological picture of substance use prevalence and treatment needs across Indigenous communities; and the need for holistic, culturally safe, trauma-informed, women-centered, family-inclusive, one-site services that offer harm reduction and traditional healing options.

A history of oppression can be rerouted with a future of empowerment, and there is a clear need for anti-oppressive, culturally restorative therapies for Indigenous people who are pregnant, birthing, and parenting. Further, pregnancy and birth can signify a time for transformation and new hope, thus services that meet Indigenous women with compassion can leverage greater uptake for improved outcomes, including longitudinally.

Disclosure/declaration of interest statement

This is to acknowledge that no financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of this research. Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

The first author can be contacted to request any aspects of data or materials.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- APTN. (2019). What is a birth alert and what does it means for families? In Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f83FfHy3My0&t=50s

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Baghdadi, Z. D. (2016). Early childhood caries and Indigenous children in Canada: Prevalence, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Journal of International Oral Health, 8(7), 830–837. https://doi.org/10.2047/jioh-08-07-17

- Banerji, A., & Shah, C. (2017). Ten-year experience of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder; diagnostic and resource challenges in Indigenous children. Paediatrics & Child Health, 22(3), 143–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxx052

- Baskin, C., McPherson, B., & Strike, C. (2012). Using the Seven Sacred Teachings to improve services for Aboriginal mothers experiencing drug and alcohol misues problems and involvement with child welfare. In D. Newhouse, K. FitzMaurice, T. McGuire-Adams, & D. Jette (Eds.), Well-being in the urban Aboriginal community; fostering biimaadiziwin, a national research conference on urban Aboriginal peoples (pp. 179–200). Thompson Educational Publishing, Inc.

- Baskin, C., Strike, C., & McPherson, B. (2015). Long time overdue: An examination of the destructive impacts of policy and legislation on pregnant and parenting Aboriginal women and their children. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 6(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2015.6.1.5

- Black, R., Godwin, M., Ponka, D., Black, R., Godwin, M., & Ponka, D. (2008). Breastfeeding among the Ontario James Bay Cree: A retrospective study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 99(2), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405453

- Bombay, A., McQuaid, R. J., Young, J., Sinha, V., Currie, V., Anisman, H., & Matheson, K. (2020). Familial attendance at Indian Residential School and subsequent involvement in the child welfare system among Indigenous adults born during the Sixties Scoop era. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 15(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.7202/1068363ar

- Boyd, S. (2019). Gendered drug policy: Motherisk and the regulation of mothering in Canada. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 68, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.10.007

- Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D., De Jonge, G. B., Holland, L., & Bekhuis, T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 104(3), 240–243. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2016.24

- Campbell, R. A. (2008). Making sober citizens: The legacy of Indigenous alcohol regulation in Canada, 1777-1985. Journal of Canadian Studies, 42(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs.42.1.105

- CBC. (2020). Number of Manitoba kids in CFS care down 4 per cent from last year social sharing. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/cfs-child-welfare-system-manitoba-families-kids-in-care-drops-annual-report-1.5746315

- Cidro, J., Bach, R., & Frohlick, S. (2020). Canada’s forced birth travel: Towards feminist Indigenous reproductive mobilities. Mobilities, 15(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2020.1730611

- Cidro, J., Doenmez, C., Phanlouvong, A., & Fontaine, A. (2018). Being a good relative: Indigenous doulas reclaiming cultural knowledge to improve health and birth outcomes in Manitoba. Frontiers in Women’s Health, 3(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.15761/FWH.1000157

- Cidro, J., Doenmez, C., Sinclair, S., Nychuk, A., Wodtke, L., & Hayward, A. (2021). Putting them on a strong spiritual path: Indigenous doulas responding to the needs of Indigenous mothers and communities. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01521-3

- Couchie, C., & Nabigon, H. (1997). Colonized wombs. In S. Patel, I. Al-Jazairu, & F. Shroff (Eds.), The new midwifery; reflections on renaissance and regulation(pp. 41-50). Womens’ Press Canada.

- Cox, L. V. (2015). FASD in a Canadian Aboriginal community context: An exploration of some ethical issues involving the access to FASD service delivery. In M. Nelson & M. Trussler (Eds.), Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in adults: Ethical and legal perspectives: An overview on FASD for professionals (pp. 223–239). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20866-4_14

- Danielson, R. A., Wallenborn, J. T., Warne, D. K., & Masho, S. W. (2018). Disparities in risk factors and birth outcomes among American Indians in North Dakota. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(10), 1519–1525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2551-9

- Dell, C., & Lyons, T. (2007). Harm reduction policies and programs for persons of Aboriginal descent. Harm Reduction for Special Populations in Canada, July, 20.

- Dooley, R., Dooley, J., Antone, I., Guilfoyle, J., Gerber-Finn, L., Kakekagumick, K., Cromarty, H., Hopman, W., Muileboom, J., Brunton, N., & Kelly, L. (2015). Narcotic tapering in pregnancy using long-acting morphine: An 18-month prospective cohort study in northwestern Ontario. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 61(2), e88–e95.

- Doty-Sweetnam, K., & Morrissette, P. (2018). Alcohol abuse recovery through the lens of Manitoban First Nations and Aboriginal women: A qualitative study. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 17(3), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2016.1138268

- Earle, K. (2018). Tapping tribal wisdom: Providing collaborative care for native pregnant women with substance use disorders and their infants: Lessons learned from listening sessions with five tribes in Minnesota Fall 2018. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/files/tapping_tribal_wisdom_508.pdf

- FNIGC. (2018). National report of the First Nations regional health survey Phase 3: Volume 2. First Nations Information Governance Centre. https://fnigc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/53b9881f96fc02e9352f7cc8b0914d7a_FNIGC_RHS-Phase-3-Volume-Two_EN_FINAL_Screen.pdf

- Fortin, M., Muckle, G., Anassour-Laouan-Sidi, E., Jacobson, S. W., Jacobson, J. L., & Bélanger, R. E. (2016). Trajectories of alcohol use and binge drinking among pregnant Inuit women. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 51(3), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv112

- Fortin, M., Muckle, G., Jacobson, S. W., Jacobson, J. L., & Bélanger, R. E. (2017). Alcohol use among Inuit pregnant women: Validity of alcohol ascertainment measures over time. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 64, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2017.10.007

- Fraser, S. L., Muckle, G., Abdous, B. B., Jacobson, J. L., & Jacobson, S. W. (2012). Effects of binge drinking on infant growth and development in an Inuit sample. Alcohol, 46(3), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.09.028

- Gould, G. S., Patten, C., Glover, M., Kira, A., & Jayasinghe, H. (2017). Smoking in pregnancy among Indigenous women in high-income countries: A narrative review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(5), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw288

- Halprin, E. (2017). A photovoice study to capture the experiences of women who use alcohol and/or drugs during pregnancy. University of Manitoba.

- He, H., Xiao, L., Torrie, J. E., Auger, N., Gros-Louis, N., Zoungrana, H., & Luo, Z. C. (2017). Disparities in infant hospitalizations in Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations in Quebec, Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189(21), E739–E746. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160900

- Heaman, M., & Chalmers, K. (2005). Prevalence and correlates of smoking during pregnancy: A comparison of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women in Manitoba. Birth (Berkeley, Calif.), 32(4), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00387.x

- Jasen, P. (1997). Race, culture, and the colonization of childbirth in northern Canada. Social History of Medicine, 10(3), 340–383. https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/10.3.383

- Jumah, N. A., Bishop, L., Franklyn, M., Gordon, J., Kelly, L., Mamakwa, S., O’Driscoll, T., Olibris, B., Olsen, C., Paavola, N., Pilatzke, S., Small, B., & Kahan, M. (2017). Opioid use in pregnancy and parenting: An Indigenous-based, collaborative framework for Northwestern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 108(5-6), e616–e620. https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.108.5524

- Kanate, D., Folk, D., Cirone, S., Gordon, J., Kirlew, M., Veale, T., Bocking, N., Rea, S., & Kelly, L. (2015). Community-wide measures of wellness in a remote First Nations community experiencing opioid dependence: Evaluating outpatient buprenorphine-naloxone substitution therapy in the context of a First Nations healing program. Canadian Family Physician, 61(2), 160–165.

- Kashak, D. (2015). An overview of issues, impacts and services for women who are using substances and are pregnant or parenting within the City of Thunder Bay. Retrieved from City of Thunder Bay website: https://www.thunderbay.ca/en/city-hall/resources/Documents/ThunderBayDrugStrategy/Maternal-Substance-Use-Literature-Review-and-Environmental-Scan---Oct-1-2015.pdf

- Kelly, L., Dooley, J., Cromarty, H., Minty, B., Morgan, A., Madden, S., & Hopman, W. (2011). Narcotic-exposed neonates in a First Nations population in northwestern Ontario: Incidence and implications. Canadian Family Physician, 57(11), e441–e447. http://uml.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true%7B%5C&%7Ddb=c8h%7B%5C&%7DAN=108202239%7B%5C&%7Dsite=ehost-live

- Kelly, L., Guilfoyle, J., Dooley, J., Antone, I., Gerber-Finn, L., Dooley, R., Brunton, N., Kakegamuck, K., Muileboom, J., Hopman, W., Cromarty, H., Linkewich, B., & Maki, J. (2014). Incidence of narcotic abuse during pregnancy in northwestern Ontario: Three-year prospective cohort study. Canadian Family Physician, 60(10), e493–e498.

- Klaws, D. F. (2014). Warrior women: Indigenous women share their stories of strength and agency. https://uml.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/warrior-women-indigenous-share-their-stories/docview/1629332440/se-2?accountid=14569

- Knight, E. (2021). Methamphetamine use disorder: A review of evidence for treatment. University of Manitoba Rady Faculty of Health Sciences Department of Psychiatry Grand Rounds, March 9.

- Lavallée, A. (2019). The understanding of cultural inclusion amongs substance use and Indigenous peoples based in Winnipeg, Manitoba. University of Manitoba.

- Lavoie, J. G. (2013). Policy silences: Why Canada needs a national First Nations, Inuit and Métis health policy. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 72(1), 22690. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v72i0.22690

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Marcellus, L. (2017). A grounded theory of mothering in the early years for women recovering from substance use. Journal of Family Nursing, 23(3), 341–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840717709366

- Marcellus, L., Nathoo, T., Poole, N. (2016). Harm reduction and pregnancy: Best and promising practices for supporting pregnant women and new mothers who use substances. Second Biennial Healthy Mothers and Healthy Babies Conference: Advances in Clinical Practice and Research Across the Continuum. http://extension://nhppiemcomgngbgdeffdgkhnkjlgpcdi/data/pdf.js/web/viewer.html?file=http://%3A%2F%2Fhttp://www.perinatalservicesbc.ca%2FDocuments%2FEducation%2FConference%2F2016%2FPresentations2%2FD4iii_Marcellus.pdf

- McCalman, J., Heyeres, M., Campbell, S., Bainbridge, R., Chamberlain, C., Strobel, N., & Ruben, A. (2017). Family-centred interventions by primary healthcare services for Indigenous early childhood wellbeing in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States: A systematic scoping review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1247-2

- Muckle, G., Laflamme, D., Gagnon, J., Boucher, O., Jacobson, J. L., & Jacobson, S. W. (2011). Alcohol, smoking, and drug use among Inuit women of childbearing age during pregnancy and the risk to children. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(6), 1081–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01441.x

- Nathoo, T., Marcellus, L., Bryans, M., Clifford, D., Louie, S., Penaloza, D., Seymour, A., Taylor, M., Poole, N. (2015). Harm reduction and pregnancy: Community-based approaches to prenatal substance use in western Canada. University of Victoria School of Nursing and British Columbia Centre of Excellence of Women’s Health. http://canadianharmreduction.com

- Nguyen, N. H., Subhan, F. B., Williams, K., & Chan, C. B. (2020). Barriers and mitigating strategies to healthcare access in Indigenous communities of Canada: A narrative review. Healthcare, 8(2), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020112

- NHRC. (2020). Training guide: Pregnancy and substance use: A harm reduction toolkit. National Harm Reduction Coalition. https://harmreduction.org/issues/pregnancy-and-substance-use-a-harm-reduction-toolkit/

- Niccols, A., Dell, C. A., & Clarke, S. (2010). Treatment issues for Aboriginal mothers with substance use problems and their children. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8(2), 320–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9255-8

- Niccols, A., Milligan, K., Sword, W., Thabane, L., Henderson, J., & Smith, A. (2012). Integrated programs for mothers with substance abuse issues: A systematic review of studies reporting on parenting outcomes. Harm Reduction Journal, 9, 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-9-14

- NIMMIWG. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: The final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf

- Olson, R. (2013). The politics of birth place and Aboriginal midwifery in Manitoba, Canada. University of Sussex.

- Olson, R., & Couchie, C. (2013). Returning birth: The politics of midwifery implementation on First Nations reserves in Canada. Midwifery, 29(8), 981–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.12.005

- Owais, S., Faltyn, M., Johnson, A. V. D., Gabel, C., Downey, B., Kates, N., & Van Lieshout, R. J. (2020). The perinatal mental health of Indigenous women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 65(3), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719877029

- Pei, J., Carlson, E., Tremblay, M., & Poth, C. (2019). Exploring the contributions and suitability of relational and community-centered Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) prevention work in First Nation communities. Birth Defects Research, 111(12), 835–847. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.1480

- Pham, T., Tinajero, Y., Mo, L., Schulkin, J., Schmidt, L., Wakeman, B., & Kremer, M. (2021). Obstetrical and perinatal outcomes of patients with methamphetamine-positive drug screen on labor and delivery. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 76(4), 187–189. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ogx.0000743316.69504.7c

- Popova, S., Lange, S., Probst, C., Parunashvili, N., & Rehm, J. (2017). Prevalence of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders among the general and Aboriginal populations in Canada and the United States. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 60(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.09.010

- Premchit, S., Orungrote, N., Prommas, S., Smanchat, B., Bhamarapravatana, K., & Suwannarurk, K. (2021). Maternal and neonatal complications of methamphetamine use during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2021, 8814168. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8814168

- Redding, G. J., & Byrnes, C. A. (2009). Chronic respiratory symptoms and diseases among Indigenous children. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 56(6), 1323–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.012

- Ritland, L., Jongbloed, K., Mazzuca, A., Thomas, V., Richardson, C. G., Spittal, P. M., & Guhn, M. (2020). Culturally safe, strengths-based parenting programs supporting Indigenous families impacted by substance use: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(6), 1586–1610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00237-9

- Ritland, L., Thomas, V., Jongbloed, K., Zamar, D. S., Teegee, M. P., Christian, W. K., Richardson, C. G., Guhn, M., Schechter, M. T., Spittal, P. M., & for the Cedar Project Partnership. (2021). The Cedar Project: Relationship between child apprehension and attempted suicide among young Indigenous mothers impacted by substance use in two Canadian cities. PLoS One, 16(6), e0252993. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252993

- Robertson, S. (2019). Families being heard: Indigenous mothers’ experiences with the child welfare system in Manitoba. University of Manitoba. http://scioteca.caf.com/bitstream/handle/123456789/1091/RED2017-Eng-8ene.pdf?sequence=12&isAllowed=y%0A http://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2008.06.005%0A https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305320484_SISTEM_PEMBETUNGAN_TERPUSAT_STRATEGI_MELESTARI

- Rowan, M., Poole, N., Shea, B., Gone, J. P., Mykota, D., Farag, M., Hall, C. H., Mushquash, C., & Dell, C. (2014). Cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: Findings from a scoping study. Substance Abuse: Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 9(1), Article 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-9-34

- Russell, C., Firestone, M., Kelly, L., Mushquash, C., & Fischer, B. (2016). Prescription opioid prescribing, use/misuse, harms and treatment among Aboriginal people in Canada: A narrative review of available data and indicators. Rural & Remote Health, 16(4), 1–14. http://uml.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true%7B%5C&%7Ddb=c8h%7B%5C&%7DAN=119864300%7B%5C&%7Dsite=ehost-live

- Sayers, S. M. (2009). Indigenous newborn care. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 56(6), 1243–1261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.009

- Shahram, S. Z., Bottorff, J. L., Kurtz, D. L. M., Oelke, N. D., Thomas, V., Spittal, P. M., & Cedar Project Partnership. (2017a). Understanding the life histories of pregnant-involved young Aboriginal women with substance use experiences in three Canadian cities. Qualitative Health Research, 27(2), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316657812

- Shahram, S. Z., Bottorff, J. L., Oelke, N. D., Dahlgren, L., Thomas, V., & Spittal, P. M. (2017b). The Cedar Project: Using Indigenous-specific determinants of health to predict substance use among young pregnant-involved Aboriginal women. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0437-4

- Shahram, S. Z., Bottorff, J. L., Oelke, N. D., Kurtz, D. L. M., Thomas, V., & Spittal, P. M. (2017c). Mapping the social determinants of substance use for pregnant-involved young Aboriginal women. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 12(1), 1275155. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2016.1275155

- SLFNHA. (2017). Anishinaabe Bimaadiziwin research program; Research compilation prepared for Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority & Meno Ya Win Health Centre. extension://nhppiemcomgngbgdeffdgkhnkjlgpcdi/data/pdf.js/web/viewer.html?file=http%3A%2F%2Fslmhc.on.ca%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F05%2F04_SLMHC_Research_Compilation_3_2013-2015_edoc.pdf

- Small, S., Porr, C., Swab, M., & Murray, C. (2018). Experiences and cessation needs of Indigenous women who smoke during pregnancy: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 16(2), 385–452. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003377

- Smylie, J., Crengle, S., Freemantle, J., & Taualii, M. (2010). Indigenous birth outcomes in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States: An overview. The Open Women’s Health Journal, 4, 7–17.

- Specker, B. L., Wey, H. E., Minett, M., & Beare, T. M. (2018). Pregnancy survey of smoking and alcohol use in South Dakota American Indian and white mothers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.016

- Statistics Canada. (2017). Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-404-X2016001. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-CSD-Eng.cfm?TOPIC=9&LANG=Eng&GK=CSD&GC=4611040

- Statistics Canada. (2020). Aboriginal peoples highlight tables. 2016 Census. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/abo-aut/Table.cfm?Lang=Eng&T=102&S=88&O=A&RPP=9999

- Stevenson, L., Campbell, S., Bohanna, I., Gould, G. S., Robertson, J., & Clough, A. R. (2017). Establishing smoke-free homes in the Indigenous populations of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(11), 1382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111382

- Sword, W., Jack, S., Niccols, A., Milligan, K., Henderson, J., & Thabane, L. (2009). Integrated programs for women with substance use issues and their children: A qualitative meta-synthesis of processes and outcomes. Harm Reduction Journal, 6, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-6-32

- Symons, M., Pedruzzi, R. A., Bruce, K., & Milne, E. (2018). A systematic review of prevention interventions to reduce prenatal alcohol exposure and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Indigenous communities. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6139-5

- Tait, C. L. (2009). Disruptions in nature, disruptions in society: Aboriginal Peoples of Canada and the “making” of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. In L. J. Kirmayer & G. G. Valaskakis (Eds.), The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada (pp. 196–222). University of British Columbia Press.

- Tait, C. L. (2014). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Indigenous peoples of Canada. In P. Menzies & L. Lavallée (Eds.), Journey to healing; Aboriginal people with addiction and mental health issues; what health, social service and justice workers need to know (pp. 217–230). Centre for Addictions and Mental Health.

- Torchalla, I., Linden, I. A., Strehlau, V., Neilson, E. K., & Krausz, M. (2014). “Like a lots happened with my whole childhood”: Violence, trauma, and addiction in pregnant and postpartum women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Harm Reduction Journal, 11(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-11-34

- Tough, S., Clarke, M., & Cook, J. (2007). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder prevention approaches among Canadian physicians by proportion of Native/Aboriginal patients: Practices during the preconception and prenatal periods. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11(4), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-006-0176-x