Abstract

In Greenland, where addiction-related concerns significantly affect well-being, research has explored alcohol’s impact on health and mortality. However, no studies have focused on mortality among those who received addiction treatment. This study investigates whether individuals treated for addiction in Greenland experience elevated mortality rates compared to the general population. The study encompassed individuals receiving addiction treatment through the national system between 2012 and December 31, 2022. Data on treatment were sourced from the National Addiction Database, and Statistics Greenland. Person-years at risk were calculated and used to estimate crude mortality rates (CMRs). Adjusted standardized mortality rates (SMRs), accounting for age, sex, and calendar year, were estimated using an indirect method based on observed and expected deaths. Of the 3286 in treatment, 53.9% were women, with a median age of 37. About a third had undergone multiple treatment episodes, and 60.1% received treatment in 2019 or later. The cohort was followed for a median of 2.89 years, yielding 12,068 person-years. The overall CMR was 7.79 deaths per 1000 person-years, with a SMR of 1.42 (95% confidence interval: 1.15; 1.74). Significantly, SMRs differed by age at treatment entry, with younger groups exhibiting higher SMRs (p value = .021). This study found that individuals seeking treatment for addiction problems in Greenland had a higher mortality rate than the general population. Importantly, these SMRs were substantially lower than those observed in clinical populations in other countries.

Background

Globally, the World Health Organization estimates that 3 million deaths each year can be attributed to the harmful use of alcohol (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Harmful use of alcohol is associated with the risk of various mental and behavioral disorders, including dependence, liver cirrhosis, certain types of cancer, and cardiovascular diseases. In addition, a significant proportion of the alcohol-related burden on health is attributable to non-natural deaths injuries—including accidents and intentional injuries counting traffic accidents, violence and suicides (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Indigenous populations might be at special risk, as North American studies report a substantial higher rate of alcohol attributable deaths within the American Indian/Alaska Native population than the rest of the population in the United States of America (Karaye et al., Citation2023; Landen et al., Citation2014) as well as in First Nations adults compared to the rest of the population in Canada (Park et al., Citation2015). One review study on cannabis related mortality concluded the evidence to be inconclusive due to a low number of studies, however across the many studies included the results suggested an elevation in levels of accidents and some types of cancers among cannabis users (Calabria et al., Citation2010). Illicit drug use in the indigenous populations in Australia have been estimated to account for 2.8% of deaths (MacRae & Hoareau, Citation2016) and another study from Denmark found a five time increase in standardized mortality rate among cannabis users compared to the general population (Arendt et al., Citation2013).

Peter Bjerregaard concluded in the 1980s that many alcohol-related deaths in Greenland were avoidable. In a study of hospital admission during one year in a Greenlandic town, he found that 12% were due to alcohol, with two thirds of the admission being due to accidents or violence. He estimated that 70% of males’ and 52% of females’ potential years of life lost were due to accidents, suicides or homicides (Bjerregaard, Citation1991). In a later study, Hans Aage found similar alcohol related mortality rates in Greenland and Denmark at 28.2 and 28.4 per 100.000 inhabitants above the age of 14 years for the period 1951–2010 (Aage, Citation2012). Still, Aage identified a significant difference in the share of alcohol related deaths due to liver cirrhosis, which were 24% in Greenland, but up to 64% in Denmark. The low prevalence of liver cirrhosis in Greenland was confirmed in another study, which related the results to possible differences in nutrition, alcohol metabolism and the binge-drinking pattern seen in Greenland (Lavik et al., Citation2006). Around 20% of all deaths in Greenland were unnatural deaths due to external causes (e.g., accidents and suicides) for the time period studied by Hans Aage (Aage, Citation2012). Homicide rates have been decreasing over time and are now at a level of around 15/100.000 inhabitants and one study found 62% of perpetrators in homicide cases to have a problematic use of alcohol and/or cannabis (Christensen et al., Citation2016; Grønlands Statistik, Citation2022). No studies of cannabis related mortality have been conducted in Greenland yet.

Cannabis is an illicit drug in Greenland and the official recommendations for alcohol intake are a maximum of 14 drinks with 12 g of ethanol per week for men and 7 drinks per week for women, with no more than 4 drinks on a single occasion for everyone ([Departement], P.T.n.p., 2024; [Portal] & P.T.n.h, 2024). In the Population Health Surveys in Greenland, approximately 40% of the studied population show potential harmful use of alcohol and a binge-drinking pattern where 34% consumed 5 or more drinks on at least one occasion each month (Larsen et al., Citation2018), and this pattern has persisted for many years (Bjerregaard & Aidt, Citation2010; Bjerregaard & Dahl-Petersen, Citation2011; Bjerregaard et al., Citation2008; Dahl-Petersen et al., Citation2016; Larsen et al., Citation2018). Studies have shown an increase in the alcohol consumption levels in Greenland from the mid 1950s till the end of the end of the 1980s where it reached the highest level of around 22 l of alcohol per adult person per year. Since then, many initiatives and regulations have affected the alcohol consumption levels which are now down to approximately 8 l per adult person per year (Aage, Citation2012; Bjerregaard et al., Citation2020). In the Population Health Surveys, cannabis was estimated to be used regularly (more than once a month) for approximately 9% of women and 15% of men (Larsen et al., Citation2018).

High premature death rates among alcohol treatment-seeking individuals are well-documented in various parts of the world (Charlson et al., Citation2015; Pitkänen et al., Citation2020; Roerecke & Rehm, Citation2014). Specifically, mortality rates have been found to be high in indigenous populations (Alaska Native Epidemiology Center, Citation2021; Allen et al., Citation2011). However, no studies have specifically investigated this in the context of Greenland among individuals seeking treatment for addiction problems.

By shedding light on the mortality patterns of individuals who have been in treatment for addiction problems, our study may offer insights into the distinct challenges faced by individuals with addiction issues in this Arctic territory.

Our aims were to: (1) estimate the mortality rate among individuals who have sought treatment for addiction problems at least once and compare the mortality rate with the expected rate; (2) examine mortality among individuals who have sought treatment for addiction problems by gender, age, prior treatment, and treatment outcome (ended as planed or terminated prematurely).

Methods

Design and participants

We included individuals who initiated publicly available treatment for addiction between 2012 and 2022, with treatment completion occurring on or before December 31, 2022.

A total of 3414 patients initiated treatment for addiction problems (either or both alcohol, cannabis and gambling) during the period under study, and had a total of 4784 treatment entries. Among these individuals, 128 were excluded due to the absence of a valid personal identification number.

For the primary analysis, the last treatment entry was used to reduce bias from individuals with severe addiction problems having multiple treatments and potentially living longer. However, to address the possibility of overestimating mortality, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the first treatment entry.

Setting

Greenland, the largest island in the world and the home of approximately 56.600 inhabitant and the majority (90%) is of Greenlandic origin (Grønlands Statistik, Citation2023). Around 60% live in one of the five main cities, 25% live in one of the smaller cities and 15 in the smallest living places (ibid). With a small population living across very large distances and no living places connected by road, all transportation is thus done by boat or flight. This challenging infrastructure also affects the health care services, as all main cities have a hospital however not all types if treatment is available everywhere and many patients have to be transported to Nuuk and some even abroad for specialized care (Niclasen & Mulvad, Citation2010).

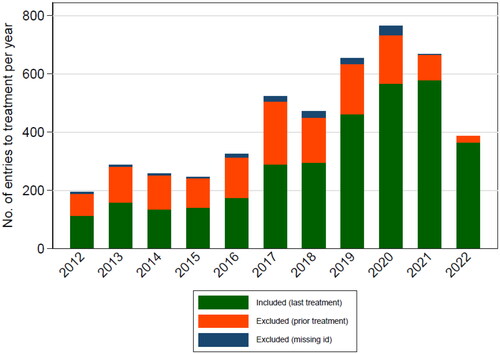

Recognizing the significant health and social problems associated with alcohol and cannabis, the government of Greenland has prioritized prevention efforts in its health strategy (Departement for Sundhed, Citation2012, Citation2020). While individuals in Greenland have been able to seek treatment for addiction problems since the 1980s (Poulsen, Citation2012), the number of individuals seeking treatment remained between 150 and 250 per year for an extended period. However, there was a substantial increase in the numbers in 2016 following the introduction of Allorfik, the national addiction treatment service in Greenland, with more than 700 treatment courses conducted in 2021 (Andersen et al., Citation2022).

During the period from 2012 to 2016, individuals seeking addiction treatment were referred through their municipalities social service system and traveled to Nuuk, free of charge. There, they underwent intensive daily treatments, with some residing in designated patient facilities, while residents of Nuuk had the option to remain in their own homes during treatment.

The introduction of Allorfik in 2016 led to the implementation of new local treatment facilities in each of the main cities across the five municipalities of Greenland and implementation of new treatment methodologies - motivational interviewing (Miller, Citation1983) and cognitive behavioral therapy (Magill & Ray, Citation2009) based on evidence and best practice from e.g. Denmark and England (Danish Health authority, Citation2018; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Citation2011). Individuals seeking addiction treatment could now access it directly at these facilities or be referred through channels such as their municipality or employer/workplace. The five new treatment centers cover about 60% of the total population in Greenland (Flyger et al., Citation2024a, Citation2024b). For people living in smaller living places without an Allorfik treatment center, addiction treatment was available through traveling counselors visiting on a regular basis or by traveling to Nuuk for treatment.

Data

Alongside the introduction of Allorfik, a national addiction treatment database was created, consisting of data stemming from the assessment interviews prior to treatment start, and information on treatment termination. This database contains patient information sourced from a Greenlandic version of the Addiction Severity Index and patient record information. In the transition from the old treatment system to Allorfik basic information on previous treatment attendees and their treatment courses (2012–2015) was handed over to Allorfik for registration in the database.

In Greenland, every individual is assigned a unique personal identification number (CPR) at birth. This personal identification number is used to link data from the addiction treatment centers to the register of deaths at Statistics Greenland.

The study and handling of data was approved by the Science Ethics Committee (nr. 2020-26241).

Variables

Information on age, sex, date of treatment entry came from the assessment interview in the national addiction database. Information on prior treatment was coded as “yes” if either the patient reported prior treatment in their entry interview, or if there was a prior treatment record. Otherwise, this variable was coded “no.” Year of treatment entry was categorized into three groups, the first encompassing the years 2012–2015 (before Allorfik), the second the years 2016–2018 (implementation phase of Allorfik), and the third 2019–2022 (Allorfik fully implemented). Age was categorized in five groups: >18, 18–29, 30–44, 45–59 and 60+. Treatment termination was categorized as planned completion, (concluded in agreement between therapist and patient), drop out (patients stopped showing) and terminated against given advice (ended upon patient’s wish). Date of treatment termination and reason of treatment termination also came from the national addiction database. Information on date of death and cause of death among the individuals in treatment were supplied by Statistics Greenland, and data on overall deaths in Greenland per year, sex, and age (in years) were also provided by Statistics Greenland (Grønlands Statistik, Citation2022).

Statistical analysis

We calculated person-years (PY) at risk for each person using the follow-up period (January 1, 2012, to 31 December 31, 2022) where follow-up started from the last assessment admission date until the date of death or study end date (December 31, 2022).

Crude mortality rates (CMRs) were calculated by dividing the total number of deaths by the person-years at risk. Age-, sex- and calendar-year-adjusted Standardized Mortality Rates (SMRs) were estimated using an indirect method (observed deaths/expected deaths). The expected number of deaths was calculated using age-, sex- and calendar-specific death rates for Greenland, available at Statistics Greenland (Statistik, Citation2024). The SMR is expressed as a ratio, where an SMR of 1.0 indicates that the observed mortality is in line with what would be expected in the standard population. The 95% confidence intervals for CMRs and SMRs were calculated based on the Poisson distribution. CMRs and SMRS were also calculated within subgroups specified by age group (five groups), sex, termination of treatment status (completed, dropout or other), and year of treatment entry (before, under, or after transition to Allorfik). This enabled the examination of potential variations across these population characteristics. For selected characteristics, we compared SMRs between groups.

The above was repeated in a sensitivity analysis, using the first admission date, excluding earlier treatment as characteristic. Results can be seen in the Appendix A.

Analyses were conducted in Stata v18.

Results

A total of 3286 persons in treatments met our inclusion criteria. provides a visual representation of the number of treatments included and excluded based on specific reasons and corresponding years.

As presented in , the majority of patients were female (53.9%) and the median age at last observed treatment was 37 years. 33.8% of the patients had attended addiction treatment more than once. The majority of patients (60.1%) had attended treatment in 2019 or later and half of the patients completed their treatment course. Ninety-four persons had deceased during the observation period, i.e. until first quarter of 2023. Among those who died, 50 persons died of natural causes, 8 died because of accidents, 31 persons died by suicided and 5 died by assault. In , it is also evident that most deceased were men and that men more often died from unnatural causes.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by gender, 2012–2022 (N = 3286).

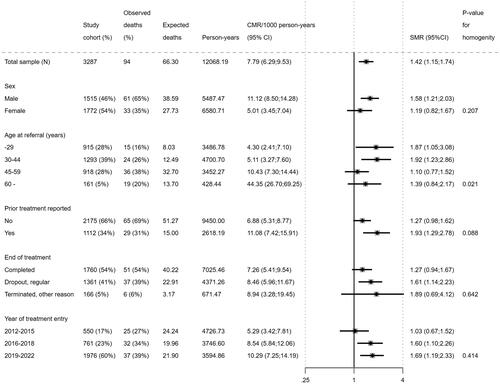

The cohort was followed for a median of 2.89 years (range 0–10.67 years) and a total of 12.068 person-years as presented in . The CMR was 7.79 deaths per 1000 person years (95% confidence interval 6.29–9.53). The SMR was 1.42 death with no significant difference in SMR between males and females (p value = .207). There was a significant difference in SMR, depending on age at the time for treatment seeking, where the young ages groups had a higher SMR than the older age groups (p value = .021). There was no significant difference in SMR depending on whether the individuals had been treated once or several times, whether they had completed treatment or dropped out, or whether they had been in treatment early in the period under study or later.

Figure 2. All-cause mortality (crude mortality rate (CMR) and standardized mortality rate (SMR)) of the study cohort by demographic and treatment characteristics, 2012–2022. p Value for homogeneity test of SMR among subgroups.

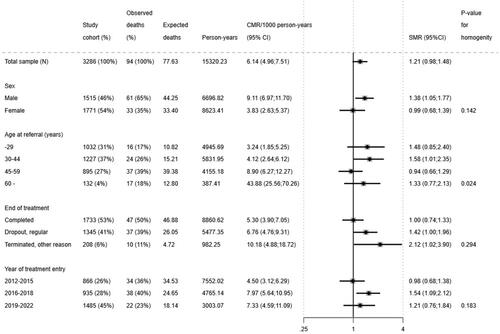

To assess the robustness of our findings, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the first treatment entry for individuals with multiple treatment courses (Appendix and ). Specifically, the sensitivity analysis showed an SMR of 1.21 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.98; 1.48), compared to the SMR of 1.42 (95% CI: 1.15; 1.74) from the primary analysis. Although the SMR from the sensitivity analysis was somewhat smaller and not statistically significant, the overall pattern of mortality risk remained consistent. This suggests that the primary results are largely robust and reliable, despite the methodological differences.

Discussion

This is the first study on mortality among individuals with addiction problems in Greenland who have sought addiction treatment at least once. The study revealed an elevated death rate in the treated population compared to the expected rate using the last treatment entry, indicated by an SMR of 1.42. The sensitivity analysis using the first treatment entry showed an SMR of 1.21, which was not statistically significant. Additionally, a significant difference by age at the time of treatment was observed, with younger groups having a higher SMR than older groups.

It is previously shown that individuals entering treatment for alcohol problems have a higher risk of death as compared to the general population (Pitkänen et al., Citation2020; Roerecke & Rehm, Citation2013, Citation2014). A meta-analysis from 2013 by Roereke and Rehm found a 4.57 times higher risk of all-cause mortality among individuals who entered treatment (Allen et al., Citation2011), and similar rates have been found in later papers (Alaska Native Epidemiology Center, Citation2021; Grønlands Statistik, Citation2023), with higher SMRs for younger age groups and for women. However, in our study, the SMR of 1.42 was comparably low, and females had a lower (though not significantly) SMR than men, which was not even significantly different from the expected number of deaths in this population group in Greenland. This difference in excess mortality among treated individuals could have several explanations.

It is known that health-related conditions associated with alcohol problems are among the leading causes of mortality in Alaska (Allen et al., Citation2011). For example, in an Alaska Native study on mortality, Alaska Native people were compared with the rest of the U.S. population in terms of mortality rates. The study found that the all-cause mortality rate was 51% higher, and the rate ratio of Alaska Natives compared to all U.S. residents was highest for alcohol abuse (8.0), chronic liver disease (3.1), suicide (3.0), and homicide (2.8) (Alaska Native Epidemiology Center, Citation2021). In Canada, the difference between first nations and non-aboriginal persons in death caused by alcohol and drug use disorders accounted for a rate difference of 40.9 for men and 27.2 for women (Park et al., Citation2015). Hans Aage compared alcohol related mortality rates between Greenland and Denmark in 2012 and estimated an average alcohol related mortality rate of 28.3 in Greenland and 28.4 in Denmark per 100,000 persons (Calabria et al., Citation2010). However, Aage also pointed out that this rate was based on alcohol-related natural cause of death, and the actual number would likely be higher as the unnatural causes of death (accidents, suicide and assault) made up a higher proportion of the total mortality in Greenland than in Denmark. In Aages study the natural causes of death account for approximately 80% of all deaths in Greenland where in Denmark natural causes of deaths account for more than 90% of all deaths (Danmarks Statistik, Citation2024). The alcohol-related mortality rate and the high rate of unnatural causes of death in the general population may contribute to the lower SMR among treatment seekers observed in our study.

One can also speculate that those who seek treatment in Greenland have a different demographic distribution compared to other countries. For example, in contrast to Denmark, where the proportion of females in alcohol treatment is about one-third (Schwarz et al., Citation2018), in Greenland, the distribution is around 55% female, in spite that addiction problems are slightly more prevalent with men (43%) than women (38%) in Greenland (Larsen et al., Citation2018).

Another explanation for the lower SMRs may be attributed to access to treatment. Prior to the introduction of Allorfik, treatment options were limited, with the sole treatment facility located in the capital, Nuuk. Following the introduction of Allorfik, approximately 60% of Greenland’s population gained easy access to treatment facilities, yet this primarily benefited individuals residing in the larger towns of Greenland. After the introduction of Allorfik, the number presenting to treatment and the SMRs in our study have increased. However, a significant portion of Greenland’s population still lives in sparsely populated areas, making treatment less accessible for them.

Finally, the general addiction pattern in Greenland might also contribute to the differences found in this study and the estimated difference in SMR in other countries. The dominant pattern of addiction problems for a large proportion of the population in Greenland is binging (Larsen et al., Citation2018) where e.g. treatment seekers in Denmark primarily have high levels of consumption every day or several days a week (Schwarz et al., Citation2018). Thus, the difference between the consumption patterns in the population vs the treatment seeking population is markedly different in Denmark but perhaps not so different in Greenland. Alcohol misuse have been linked to risk of suicide in Sápmi youth (indigenous people in north Norway) (Høilo Granheim et al., Citation2023; Silviken & Kvernmo, Citation2007) and binge-drinking specifically have been found to increase risk of suicide enormously (Borges & Rosovsky, Citation1996). The drinking pattern in Greenland have also been related to the low levels of cirrhosis to the liver already described (Aage, Citation2012; Lavik et al., Citation2006), which also could be related to mortality levels.

Future studies should delve deeper into the geographical and sociodemographic characteristics of individuals seeking treatment, as compared to the general population, to gain more knowledge of treatment disparities and unmet needs.

Limitations and strengths

It was not possible to test for differences in the cause of death compared to the general population (only the expected rate) in this study, and this may be considered a limitation. However, it is worth noting that the observed number of deceased individuals was almost evenly distributed between natural and unnatural causes of death, with a significant number of suicides. A study on cause-of-death data from Greenland between 2006 and 2015 indicated that 15% of deaths were attributed to external causes, primarily concentrated in younger age groups (Iburg et al., Citation2020). Another study found extremely high suicide rates among young people in Greenland, with women at an increased risk of death by suicide (Seidler et al., Citation2023). For future studies, it is relevant to conduct a more in-depth analysis of the causes of death within this treatment-seeking population as well as in the general population. Such investigations can yield insights to guide the development of targeted interventions and preventive measures, thereby addressing these critical public health issue.

In continuation, disparities within the treatment seeking population are also interesting for future studies. Other surveys find men to have addiction problems more often than women (Dahl-Petersen et al., Citation2016; Larsen et al., Citation2018), however our study have a small overrepresentation of women seeking addiction treatment and this disparity might affect the results of our analysis.

In this study, persons with multiple treatment courses were only included with their last completed treatment course, reducing the number of data entries. For the primary analysis, the last observation was used to mitigate potential bias from individuals with more severe addiction problems who might have multiple treatments and live longer. This approach aims to reflect the mortality risk associated with the most recent treatment episode, capturing the current state of the individual’s health and addiction severity more accurately. However, this could lead to an overestimation of mortality rates, as individuals who survive longer might skew the results. To address this, a sensitivity analysis using the first treatment entry was conducted, providing an alternative perspective on mortality risk and ensuring that the findings are robust and account for different potential biases. The results from both approaches were quite similar, suggesting robustness and reliability in the findings.

Some cases were excluded due to flawed registration practice which is a limitation to the study, especially because those excluded were not equally distributed over the years. The present study includes registered cases from before Allorfik were all persons referred to treatment where a municipality would pay expenses of treatment and the correct registered cases can therefore be considered reliable. In the first years of implementation however, registration was done manually and without validation to correct personal identification number. Validation was introduced in 2019.

A strength to the study is the linkage to the register of deaths at Statistics Greenland, which has an almost complete registration of death (Iburg et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion

This study found that the mortality rate of people who has sought treatment for addiction problems was higher than the expected rate in the background population with an SMR of 1.42, but lower compared to SMRs for populations in other countries. We found a significant difference in mortality with age as there was a significantly higher mortality rate among the young groups than the older groups who had attended treatment. We found no significant difference in SMRs between genders, prior treatment, reason of treatment termination, or year of treatment entry. The sensitivity analysis, which used the first treatment entry, yielded a not statistically significant SMR of 1.21, which indicates that while the primary findings are robust, the exact magnitude of the elevated mortality risk may vary.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aage, H. (2012). Alcohol in Greenland 1951–2010: Consumption, mortality, prices. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 71(1), 18444. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18444

- Alaska Native Epidemiology Center. (2021). Alaska native mortality: 1980-2018. Anchorage (US): Alaska Native Epidemiology Center.

- Allen, J., Levintova, M., & Mohatt, G. (2011). Suicide and alcohol-related disorders in the U.S. Arctic: Boosting research to address a primary determinant of health disparities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 70(5), 473–487. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v70i5.17847

- Andersen, C., Schou, M., & Niclasen, B. (2022). Allorfik Årsrapport 2021.Nuuk: Allorfik. p. 1–58.

- Arendt, M., Munk-Jørgensen, P., Sher, L., & Jensen, S. O. W. (2013). Mortality following treatment for cannabis use disorders: Predictors and causes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(4), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.09.007

- Bjerregaard, P. (1991). Disease pattern in Greenland: Studies on morbidity in Upernavik 1979-1980 and mortality in Greenland 1968-1985. Arctic Medical Research, 50(Suppl. 4), 1–67.

- Bjerregaard, P., & Aidt, E. C. (2010). Levevilkår, livsstil og helbred: Befolkningsundersøgelsen i Grønland 2005-2009 = Atugassarititat, inooriaaseq peqqinnerlu [Living conditions, lifestyle and health in Greenland - the Population Health Survey in Greenland 2005-2009]. SIFs Grønlandsskrifter (nr. 20). Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, Naalakkersuisut.

- Bjerregaard, P., & Dahl-Petersen, I. K. (2011). Sundhedsundersøgelsen i Avanersuaq 2010 = Avanersuarmiut peqqissusaannik misissuineq [The health survey in Avanersuaq 2010]. SIFs Grønlandsskrifter (nr. 23). Kbh.: Statens Institut for Folkesundhed. 97, 107 sider, illustreret i farver.

- Bjerregaard, P., Dahl-Petersen, I. K., & Statens, F. (2008). Institut for, Befolkningsundersøgelsen i Grønland 2005-2007: Levevilkår, livsstil og helbred [The Population Health Survey 2014]. SIFs Grønlandsskrifter (nr. 18). Kbh.: Statens Institut for Folkesundhed. 174 sider, illustreret.

- Bjerregaard, P., Larsen, C. V. L., Sørensen, I. K., & Tolstrup, J. S. (2020). Alcohol in Greenland 1950-2018: Consumption, drinking patterns, and consequences. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 79(1), 1814550. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2020.1814550

- Borges, G., & Rosovsky, H. (1996). Suicide attempts and alcohol consumption in an emergency room sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 57(5), 543–548. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1996.57.543

- Calabria, B., Degenhardt, L., Hall, W., & Lynskey, M. (2010). Does cannabis use increase the risk of death? Systematic review of epidemiological evidence on adverse effects of cannabis use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29(3), 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00149.x

- Charlson, F. J., Baxter, A. J., Dua, T., Degenhardt, L., Whiteford, H. A., & Vos, T. (2015). Excess mortality from mental, neurological and substance use disorders in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796014000687

- Christensen, M. R., Thomsen, A. H., Høyer, C. B., Gregersen, M., & Banner, J. (2016). Homicide in Greenland 1985–2010. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology, 12(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-015-9729-x

- Dahl-Petersen, I. K., et al. (2016). Befolkningsundersøgelsen i Grønland 2014/Kalaallit Nunaanni Innuttaasut Peqqissusaannik Misissuisitsineq 2014: Levevilkår, livsstil og helbred/Inuunermi atugassarititaasut, inooriaaseq peqqissuserlu. SIF’s Grønlandsskrifter [The Population Health Survey 2014] . Syddansk Universitet. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed.

- Danish Health authority. (2018). National clinical guideline on treatment of alcohol dependence.Copenhagen. p. 161.

- Danmarks Statistik. (2024). Døde efter dødsårsag, alder og køn [Deaths by cause, age and gender]. København: Danmarks Statistik.

- Departement for Sundhed. (2012). Inuuneritta 2 - Naalakkersuisuts strategier og målsætning for folkesundheden 2013-2019 [Inuuneritta 2 - The Government of Greenlands Strategy and Aims for the Public Health 2013-2019]. Nuuk, Greenland.

- Departement for Sundhed. (2020). Inuuneritta 3. Naalakkersuisuts strategi for samarbejdet om det gode børneliv 2020-2030[Inuuneritta 3 - The Government of Greenlands Strategy for Cooperation on the Good Life of Children 2020-2030]. Nuuk, Greenland.

- Flyger, J., et al. (2024a). A qualitative study of the implementation and organization of the national Greenlandic addiction treatment service. Frontiers in Health Services, 4.

- Flyger, J., et al. (2024b). Wishing for a more sober society: a scoping review on addiction problems and treatment services in Greenland leading to the 2016 national strategy for treatment for addiction in Greenland, U.o.S.D. Clinical Institute, Editor.

- Grønlands Statistik. (2022). Dødsfald [Deaths].

- Grønlands Statistik. (2023). Grønlands Befolkning pr 1 april 2023 [Population of Greenland as of 1 April 2023]. Nuuk.

- Høilo Granheim, I. P., Kvernmo, S., Silviken, A., & Lytken Larsen, C. V. (2023). The association between suicidal behaviour and violence, sexual abuse, and parental substance abuse among Sami and Greenlandic adolescents: The WBYG study and the NAAHS. Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, 11(1), 10–26. https://doi.org/10.2478/sjcapp-2023-0002

- Iburg, K. M., Mikkelsen, L., & Richards, N. (2020). Assessment of the quality of cause-of-death data in Greenland, 2006–2015. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48(8), 801–808. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494819890990

- Karaye, I. M., Maleki, N., & Yunusa, I. (2023). Racial and ethnic disparities in alcohol-attributed deaths in the United States, 1999-2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(8), 5587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085587

- Landen, M., Roeber, J., Naimi, T., Nielsen, L., & Sewell, M. (2014). Alcohol-attributable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999-2009. American Journal of Public Health, 104 (Suppl 3), S343–S349. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301648

- Larsen, C. V. L., et al. (2018). Befolkningsundersøgelsen i Grønland 2018. Levevilkår, livsstil og helbred - oversigt over indikatorer for folkesundheden [Population survey in Greenland 2018. Living conditions, lifestyle and health - overview of indicators for public health], in SIF’s Grønlandsskrifter [The Population Health Survey in Greenland 2018]. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, SDU. p. 1–62

- Lavik, B., Holmegaard, C., & Becker, U. (2006). Drinking patterns and biochemical signs of alcoholic liver disease in Danish and Greenlandic patients with alcohol addiction. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 65(3), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v65i3.18103

- MacRae, A., & Hoareau, J. (2016). Review of illicit drug use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, in Australian Indigenous Healthreviews. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. p. 39.

- Magill, M., & Ray, L. A. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(4), 516–527. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516

- Miller, W. R. (1983). Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 11(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0141347300006583

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2011). Alcohol-use disorders: Diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence | guidance and guidelines | NICE.

- Niclasen, B., & Mulvad, G. (2010). Health care and health care delivery in Greenland. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 69(5), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v69i5.17691

- Paarisa [The national prevention departement]. Råd om alkohol [Recommendations on alcohol] Det gode liv [The good life]. (2024). Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://paarisa.gl/emner/det-gode-liv/det-gode-liv-uden-rusmidler/raad-om-alkohol?sc_lang=da.

- Park, J., et al. (2015). Avoidable mortality among First Nations adults in Canada: A cohort analysis. Health Reports, 26(8), 10–16.

- Pitkänen, T., Kaskela, T., & Levola, J. (2020). Mortality of treatment-seeking men and women with alcohol, opioid or other substance use disorders - A register-based follow-up study. Addictive Behaviors, 105, 106330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106330

- Peqqik [The national health portal]. Om alkohol [about alcohol]. (2024). Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://peqqik.gl/Emner/Livsstil/Alkohol/OmAlkohol?sc_lang=da-DK

- Poulsen, B. K. (2012). Alkoholens historie - en historie om påbud, forbud og forskelsbehandling, in Grønlandsk kultur- og samfundsforskning[The History of Alcohol - a Story About Obligations, Prohibitions and Discrimination]. Ilisimatusarfik/Forlaget Atuagkat: : Nuuk. p. 173–195

- Roerecke, M., & Rehm, J. (2013). Alcohol use disorders and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 108(9), 1562–1578. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12231

- Roerecke, M., & Rehm, J. (2014). Cause-specific mortality risk in alcohol use disorder treatment patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(3), 906–919. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu018

- Schwarz, A.-S., Nielsen, B., & Nielsen, A. S. (2018). Changes in profile of patients seeking alcohol treatment and treatment outcomes following policy changes. Journal of Public Health, 26(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-017-0841-0

- Seidler, I. K., Tolstrup, J. S., Bjerregaard, P., Crawford, A., & Larsen, C. V. L. (2023). Time trends and geographical patterns in suicide among Greenland Inuit. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 187–187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04675-2

- Silviken, A., & Kvernmo, S. (2007). Suicide attempts among indigenous Sami adolescents and majority peers in Arctic Norway: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Journal of Adolescence, 30(4), 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.06.004

- Statistik, G. (2024). Statistikbanken Grønland[StatBank][Statistics Greenland]. Retrieved 2023, from https://bank.stat.gl/pxweb/en/Greenland/

- World Health Organization. (2022). Alcohol. Retrieved July 5, 2023, from https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol

Appendix A

Figure A1. All-cause mortality (crude mortality rate (CMR) and standardized mortality rate (SMR)) of the study cohort by demographic and treatment characteristics, 2012–2022. p Value for homogeneity test of SMR among subgroups, based on first treatment entry.

Table A1. Baseline characteristics by gender, 2012–2022 (N = 3286), first observed treatment entry.