Abstract

Given the need for qualitative research on human resource (HR) practices, this study explores and demonstrates the interrelated HR practices around motivating, engaging, and retaining employees. It employs in-depth interviews to explore such practices adopted by 4- and 5- star hotels in Dubai. The findings reveal that HR practices are classified within employer branding and internal branding and directed toward hotel and destination brand image enhancement. This study offers destination managers with HR practices that contribute to enhancing the hotel and the destination brand.

Introduction

Branding of a tourism destination is complex, especially given the interplay of the management of multiple stakeholders (e.g., hotels, supporting services, influenced by factors like human capital (Tasci, Citation2011) to make it a successful brand (Marzano & Scott, Citation2009). Hotels are a primary stakeholder involved in destination branding, contributing to the experience of tourists in creating the feeling of being welcomed to the extent of generating an impression. Employees are “image makers” (Bowen & Schneider, Citation1985) who not only create and deliver the service but also represent the image of the hotel and the destination (Gilmore, Citation2002). Consequently, hotels in a destination must ensure that their brand image makers/employees’ attitude, behavior, and efficiency (Denizci & Tasci, Citation2010) deliver service quality to achieve guest satisfaction and loyalty (Qawasmeh, Citation2016) leading to destination branding (Svetlacic, Primorac, & Siladev, Citation2020). Through good HR department’s employer branding and internal branding practices (Berthon, Ewing, & Hah, Citation2005), hotels can create employee experiences that promote positive employee behavior and performance, engagement (Biswas & Suar, Citation2018; Sehgal & Malati, Citation2013), motivation (Maroudas, Kyriakidou, & Vacharis, Citation2008), and retention (Joo-Ee, Citation2016).

Employer branding relates to practices adopted by the HR department (Huda, Haque, & Khan, Citation2014) and is critical to the HR function (Gaddam, Citation2008). Therefore, there is a need to find out the perspectives of how HR executives implement practices that support the employer brand, which in turn can affect the destination brand. Hoppe (Citation2018) states that employer branding is linked to internal branding, and this has an impact on the employer brand image. Internal branding certifies that HR practices act as enablers to ensure that employees reflect and live the brand (Alshuaibi, Mohd Shamsudin, & Abd Aziz, Citation2016). Foster et al. (Citation2010) state that both employer branding and internal branding concepts must be incorporated to ensure that the organization reflects the same brand image. This study will explore how hotel HR departments’ practices are classified under employer branding and internal branding, and how these practices are tied to the destination management organization’s requirements (DMO) to work together to enhance a destination’s brand image. Hence, this study fills a gap in the literature regarding the importance and role of hotels as major stakeholders in destination branding.

Destination branding depends on a number of factors including its human capital (Michelson & Paadam, Citation2016). Therefore, it is important that hotels develop effective HR practices (e.g., professionalism, education and training), to ensure that employees deliver services that complement the organization’s brand (Abiola-Oke, Citation2019), contribute to the destination’s success (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2016; Volgger & Pechlaner, Citation2014) and enhance its image (Gilmore, Citation2002). Some researchers state that (e.g., Miličević, Mihalič, & Sever, Citation2017) there is a link between destination branding and hotels since hotels influence destination choice and enhance its branding. However, some argue that hotel brands do not determine destination choice (Dioko & So, Citation2012) and have little or no effect on the destination brand (Abiola-Oke, Citation2019). Svetlacic et al. (Citation2020) found hotels are a key element of the tourist product and influence the destination’s image. Further, they state that hotels should invest in HR practices to provide quality leadership, management, training, knowledge, skills and competencies to their employees to ensure they deliver professional service. Additionally, Michael, Reisinger, and Hayes (Citation2019) claim that if destinations want to be competitive brands, they need to pay careful attention to human-resource related factors within the hotel industry. These inconsistencies in the research make it important to explore how hotels’ HR practices influence destination branding. Therefore, this study will explore how hotel HR departments’ practices classified under employer branding and internal branding, and how these practices are tied to the destination management organization’s requirements (DMO) to work together to enhance a destination’s brand image. Hence, this study fills a gap in the literature regarding the importance and role of hotels as major stakeholders in destination branding.

The context for this study is Dubai, an emirate in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The sample chosen is HR executives from 4 and 5-star hotels in Dubai. The hotel sector in Dubai depends on employing a large expatriate population (PWC, Citation2018) from different countries with different work standards, and may lack international and Islamic hospitality experience (Stephenson, Russell, & Edgar, Citation2010). A study on tourism destination competitiveness of the UAE found a major issue with hotel employees, including differences in work ethics, standards, and lack of international work experience. In addition, the image portrayed by expatriate frontline hotel employees does not showcase an authentic Emirati experience (Michael et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the industry fails to attract Emirati job seekers and it is noted that to experience the authentic UAE culture, lifestyle and heritage, more Emiratis need to join the hotel sector (EXSUSDUBAI.ae). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the extent to which the hotel industry invests in good HR practices that provide employee training, leadership, communication, empowerment, creativity, and innovation, allowing for the development of employee skills, attitudes, and service in a way that creates a brand image that also reflects the destination’s brand, in this case an authentic Emirati experience.

Given all the above, the purpose of this study is to understand the role of human resources in hotels and its relationship with the DMO in enhancing destination branding. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to:

develop a conceptual model of HR practices within employer branding, internal branding and hotel and destination brand image enhancement.

identify the HR practices linked to employer branding using Berthon et al. (Citation2005) model and internal branding practices.

identify the collaborative practices between the HR departments of hotels and the DMO and how that supports destination branding.

Literature review

The HR department’s decisions and practices are influenced by a rapidly changing competitive business environment, a tight labor market, and changing customer demands (Abukhalifeh, Som, & Albattat, Citation2013). Further, employees wield power to shape brand perceptions positively or negatively through authentic conversations and interactions with customers and external brand stakeholders (Morokane, Chiba, & Kleyn, Citation2016; Nart, Sututemiz, Nart, & Karatepe, Citation2019). Therefore, it is important for HR managers of hotels to develop practices that keep employees motivated and engaged (Sokro, Citation2012). The literature review below discusses HR practices related to employer branding, internal branding, and the role of HR and destination branding.

Employer branding

Ambler and Barrow (Citation1996, p. 8) adopted Aaker’s (Citation1991) definition of employer brand as a “package of functional, economic and psychological benefits provided by employment, and identified with the employing company.” They further proposed that the employer brand is best managed as a function of HR responsible for employee development, recognition, social and psychological well-being, and monetary benefits.

Berthon et al. (Citation2005, p. 157) expanded Ambler and Barrow (Citation1996) original work by establishing the “employer attractiveness (EmpAt)” model. The model includes five attractiveness principles of employer branding which aim to attract and retain employees. Within the EmpAt model, the economic benefit defined in Ambler and Barrow (Citation1996) work is characterized as economic value. Psychological benefits are categorized as interest and social values, and the functional benefits as development and application values. Interest value focuses on a work environment that offers creative working processes that use employee talent and imagination to deliver creative and innovative goods and services. Social value refers to an enjoyable, collegial, and healthy work atmosphere. Economic value relates to employees receiving good wages and remuneration, work protection and career advancement. Development value includes employee appreciation, career growth, and development. Application value centers on stimulating employees to educate and inform coworkers, thus creating a supportive and client-focused work environment.

In recent years, several studies have explored Berthon et al. (Citation2005) and tend to support the values of the model. For example, Lee, Kao, and Lin (Citation2018) study of job seekers and current employees in Taiwan supports Berthon et al. (Citation2005) interest, social, and economic value factors, recommending that employer branding is strengthened if the organization closely links functional benefits to the interaction and sustenance of psychological emotions and real personal values to attract young job seekers. Biswas and Suar (Citation2018) study of managers in India focused mainly on the manufacturing sector, except for two organizations, one in hospitality service and other in tourism. They found that HR management factors (e.g., learning and development, performance management) contribute to the development of employer branding, thus leading to employee retention and engagement. Reis, Braga, and Trullen (Citation2017) study of 3000 employees from different professions in Brazil found promotion opportunities, above-average salaries, attractive compensation packages (economic value), and the opportunity to acquire valuable career experiences, and hence more self-confidence professionally (development value), were important. Another study conducted with employees in France across different sectors claims that economic value (e.g., financial stability) is important but should not override emotional value (Benraïss-Noailles & Viot, Citation2021). Despite the many studies in this area, less attention has been paid to employer branding within the hotel sector, especially on the perspectives of senior HR executives and an under-researched context (Behery & Abdallah, Citation2019; Reisinger, Michael, & Hayes, Citation2019), e.g., the city of Dubai, UAE in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries’ (GCC) region where the hotel sector depends on expatriate employees. Therefore, the role of human resources is crucial in creating employer branding strategies to motivate and engage expatriate employees who are living away from their home country, may lack international work experience and standards, and are also unable to provide an authentic Emirati experience (Michael et al., Citation2019; Stephenson et al., Citation2010).

Internal branding

Employees are an organization’s internal brand influencing its brand image (Burin, Roberts-Lombard, & Klopper, Citation2015). Thus, the organization must engender positive and productive employee-brand related behavior (King, Grace, & Funk, Citation2012) through training in service-oriented product knowledge and the organization’s brand values (Kimpakorn & Tocquer, Citation2009). Successful customer interactions and satisfaction within the hospitality environment are dependent on engaged, motivated (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008) and well-trained employees (Ashton, Citation2018; Claver-Cortés, Pereira‐Moliner, José Tarí, & Molina‐Azorín, Citation2008). Furthermore, Claver-Cortes et al. Point out that positive customer interactions and satisfaction increases employee confidence and commitment to the organization (2008).

Therefore, it is important for the HR department to develop strategies that represent a desired brand ethos and culture. This will help promote the ideal brand experience within the organization leading to appealing and positive employee experiences and a progressive work environment aimed at engaging, retaining and attracting the right candidates (Joo-Ee, Citation2016; Mosley, Citation2007). For instance, Paek, Schuckert, Kim, and Lee (Citation2015) used the mediating role of work engagement to evaluate psychological capital e.g., resilience, confidence, and employee morale among hotel employees. They found that employees who demonstrated a high level of psychological capital showed higher work engagement, thus leading to a positive organizational brand image communicated through high-quality customer service relationships (Thompson, Lemmon, & Walter, Citation2015). Further, Morokane et al. (Citation2016) identified that an employee who endorses and identifies with the organization’s brand will positively communicate it (Alshuaibi et al., Citation2016).

Due to the importance of internal branding many studies have investigated this topic however, there appears to be some confusion over whether employer branding and internal branding are the same, interrelated or different, and whether one contributes to the other. For example, Foster et al. (Citation2010) found that there is a close relationship between the concepts of employer branding and internal branding and the terms have been used interchangeably. Aurand, Gorchels, and Bishop (Citation2005) also agrees that there is an overlap between the two. However, Saleem and Iglesias (Citation2016) suggest that the two terms may not be the same. A study within the hotel sector by Kimpakorn and Tocquer (Citation2009) in Thailand found that it is important to build the brand internally thus contributing to the hotel’s employer branding practices. Based on these conflicting views, there is a need for more research into the hotel sector’s HR practices that are linked to internal branding.

Role of human resources and destination branding

Branding is an emotional bond that connects the destination with different entities, including customers, suppliers, current and future employees (Ren & Blichfeldt, Citation2011). Destination branding is a set of collective marketing activities conducted to reconstruct (Hall, Citation2002), reposition (Gilmore, Citation2002), and build a linked brand (Capasso, Citation2017) that promotes everything the destination offers under one umbrella brand (Pereira, Correia, & Schutz, Citation2012). Hotels are a major stakeholder under this umbrella, as they provide accommodation for tourists and contribute to their overall experience and impression of the destination. Therefore, to support the destination brand in fulfilling its brand promise, the role and responsibilities, attitude, behavior, efficiency, and uniformity (Denizci & Tasci, Citation2010) of hotel employees as brand ambassadors (Xiong, King, & Piehler, Citation2013) are crucial, and help sustain the hotel and the destination’s competitive advantage (Iyer, Davari, & Paswan, Citation2018). Therefore, it is important for the HR department to adopt key practices that motivate and engage employees (Sokro, Citation2012), enhance employee wellbeing, morale, and overall company wellbeing (Fathy, Citation2018).

There seems to be a lack of research about the role of HR practices within the hotel industry and what influence they have on destination branding. Svetlacic et al. (Citation2020) highlight that hotels are important to destination branding and, as part of a strategic management role, the HR function plays a key one in ensuring that employees deliver quality service. Quality of service leads to satisfied guests, the spread of positive word-of-mouth and creates loyalty thus influencing destination branding. Abiola-Oke (Citation2019) found that branded hotels support destination branding because it sends a message that branded hotels deliver quality service. However, Jamaluddin and Riyadi (Citation2018) study found no relationship between destination branding and hotel performance. Based on these contentions, a lack of research and the gaps in these studies, this study investigates the role between HR departments’ practices in 4- and 5- star hotels and DMO’s efforts to promote destination branding from the perspective of building a collaborative destination brand.

Within destination branding, the role of the DMO is crucial for the promotion of tourism in a destination (Jeuring & Haartsen, Citation2017). Furthermore, as part of the DMO’s branding strategy it is important for them to work closely and collaboratively with their stakeholders in the destination to transmit values that are attractive and contribute to their brand equity (Hemmonsbey & Tichaawa, Citation2019). Research is still lacking in the areas of collaborative agreements between stakeholders of the destination and the DMO to develop good stewardship, the quality of employees in terms of their knowledge and skills, and the training and education of employees as part of a branding strategy (Svetlacic et al., Citation2020).

Methodology

A qualitative method approach using in-depth interviews and Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008) content analysis was adopted to gather a deeper understanding of the HR practices of the study context. The study was conducted with HR executives of hotels in Dubai, who formed the study sample, since employer and internal branding are HR functions. The requirements and procedures for sample selection are detailed below:

The participants were chosen based on expert sampling using two criteria: (a) they should be working in a 4- or 5- star hotel in Dubai, and (b) they must hold managerial positions (e.g., assistant managers, managers, directors, or general managers) in human resources, training, or learning and development (see ).

Table 1. Participant Information

A professional referral sampling technique was used where participants were selected via references provided by the Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing (DTCM), Dubai’s DMO, because of the professional connection with the hotel industry (Hogan, Loft, Power, & Schulkin, Citation2009). The DMO contacted 53 HR personnel from 4- and 5-star hotels, of these 17 participants agreed to be interviewed.

De Gagne and Walters (Citation2010) suggest that for qualitative research the sample size be determined by the researchers based on their assessment of the information to be gathered, in line with information redundancy and data saturation norms. Thus, 15 in-depth interviews were conducted with 17 participants. Interviews 3 and 11 as seen in were done together as the respondents requested for this. In the case of interview 11, the interviewees were from the same hotel chain at different locations in Dubai and have the same designation. As a rule of thumb, 12–40 participants are considered the ideal sample size for a qualitative study (Koseoglu et al., Citation2016), based on adequate data saturation. Furthermore, sample sizes in qualitative studies are commonly smaller in comparison to quantitative studies (Hardy & Gretzel, Citation2011). The researchers decided to stop collecting data once information redundancy was reached (Suttikun, Chang, & Bicksler, Citation2018) and no further conclusions could be drawn (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). Furthermore, credible conclusions were drawn as each interview was audio-taped and transcribed immediately on completion, and observations were documented (Kowal & O’Connell, Citation2014). The duration of each interview was between 60 and 90 minutes and were conducted either at the participant’s office or at the DMO’s office i.e., DTCM.

The interview questions were semi-structured. The interview guide contained 20 questions, two of which addressed an understanding of the interviewee’s role and background in the organization. The remaining 18 questions related to HR practices centered around Berthon et al. (Citation2005) employer branding model and also HR perspectives on internal branding and destination branding practices.

Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Next, NVivo 12 (QSR International) software was utilized for content analysis of the written-interview transcripts (Malhotra & Birks, Citation2006) of 240 transcribed pages (119,666 words minus questions) from 17 participants. This was done to find out the number of times the words motivate, engage and retain were used. This was done by the researchers to understand the importance of employee engagement (Biswas & Suar, Citation2018), employee motivation (Maroudas et al., Citation2008) and employee retention (Joo-Ee, Citation2016) since these attributes influence the employer brand (Barrow & Mosley, Citation2006), leading to positive customer interactions (Claver-Cortés et al., Citation2008) and contributing to the hotel and the destination’s success (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2016).

The next step was the analysis of the transcribed verbatim interviews using Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008) qualitative content analysis approach to understand the HR practices. The procedure consisted of three steps i.e., preparation, organization, and reporting of the results. In the preparation and organization phases of the analysis, the researchers adapted Guba’s (Citation1978) and Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) strategy for examining the categories and relationships within the identified HR practices. According to Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008), the preparation and organization phases involve an inductive and/or deductive analytical approach where the researcher immerses oneself in the data to understand the context in terms of what is being said, what is happening, who is saying it, while sifting and analyzing the data, guided by the aim of the study. For this process one of the researchers undertook this analysis which was later checked and re-checked by the other two researchers. The inductive process required “open coding, creating categories and abstraction” (p. 109). The first step involved open coding through making notes and headings on the written text. Second, to better understand the data and generate knowledge (Cavanagh, Citation1997), categories were developed under the employer branding, internal branding and destination branding practices’ themes. The third step was abstraction, where the researcher created content-characteristic words (Kyngas & Vanhanen, Citation1999), e.g., the category “family” was given to the group of data based on the statement “Whenever I see them [employees] somewhere, it’s like you see family.” The category “connected” was given for “Collaborating on activities and events and making sure that they feel connected.” This was also reviewed in detail by the other two researchers.

This was followed by a deductive analytical approach, which is used when “when the structure of the analysis is operationalized on the basis of previous knowledge” (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008, p. 107). The additional step of deductive analysis was used to sift and classify the HR practices that fitted within Berthon et al. (Citation2005) five “employer attractiveness (EmpAt)” principles of employer branding. After the data was categorized under the (EmpAt) model, the researcher created categories different to the (EmpAt) model values but “keeping within the bounds, following principles of inductive content analysis” (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008, p. 111). For example, instead of naming the data as values under Berthon et al. (Citation2005) model such as interest value, the researchers categorized it differently and named it “innovative practices.” This was done for all the five values, and for each new category name the researchers provided a detailed explanation in the findings justifying the category name and the corresponding Berthon et al. (Citation2005) value. Throughout the findings the researchers provided statements of the respondents to show how the themes and categories emerged.

Findings

The hotel industry is highly competitive and requires good branding practices to motivate, engage, and retain employees (Sokro, Citation2012). Using NVivo, a text search was conducted to analyze the frequency of the following words and their variations: “motivate,” “engage,” and “retain.” “Engage” was the most used word, occurring 57 times, followed by “motivate,” 27 times, and “retain,” 17 times. This step was conducted to find out how important it is that HR departments within hotels focus on motivating, engaging and retaining employees.

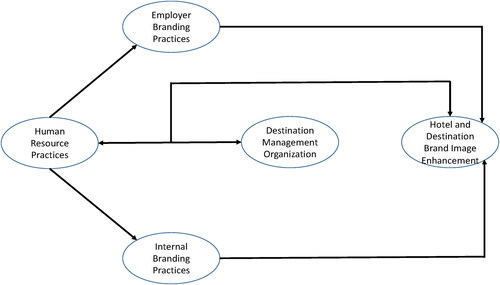

The empirical material constitutes a representative selection of the interviewee statements from senior HR executives in 4- and 5- star hotels in Dubai. The first objective of the study proposes a model that presents the two themes linked to HR practices i.e., employer branding and internal branding, the collaborative practices between the hotels and the DMO, and how they all contribute to destination branding (). The findings of the proposed conceptual model highlight the interdependencies between HR practices and the second objective of the study, and are explained as categories under employer and internal branding practices. The third objective is presented showing the collaborative practices between HR departments in hotels and the DMO with an explanation for each category that emerged from the study aimed at promoting the destination brand “Dubai.”

Employer branding practices

These findings support Berthon et al. (Citation2005) values within their employer branding model. The five categories are classified as “innovative practices,” “create a fun work environment,” “compensation and benefits,” “recognizing and rewarding employees,” and “learning opportunities.”

Innovative practices: The first category relates to the practices that are innovative (Reis et al., Citation2017) and how they fit within Berthon et al. (Citation2005) model under the interest value. Employees are important sources of innovation through the creation of situational contexts (Ma Prieto & Pilar Pérez-Santana, Citation2014), such as organizational ambidexterity practices (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019). The HR executives interviewed develop programmes like “Switch and Cross-training,” where managers swap roles or departments with staff. Other programmes include “Thrive Global,” which enhances employee work-life balance, while other motivational programmes aim to improve attitudes, behavior, and habits amongst employees in the workplace (Young et al., Citation2015), thus empowering employees. Further, the study found that innovative employer branding practices expressed in the words of senior HR executives are aimed at improving: employee engagement; motivation; recognition; opportunities to gain new skills; knowledge and experience; teamwork; well-being; spiritual, mental and physical development.

Switch is one programme… other hotels are doing it as well… this is a programme [where] an executive member and a colleague […] get to switch roles for a day… We realised [that] this is engagement and recognition… They also [perform] inter-departmental switches… [for] exposure… you also develop people’s skills, knowledge and experience.

We offer also cross-training if you want to go to a different hotel. So, I think that’s quite motivational.

There’s always emphasis on driving, motivating, and engaging the team that connects […] to the hotel. There are actually four areas: […] trust, […] leadership, […] engagement, and how employees balance work–life. Whether […] spiritual balancing [or] physical work… the hotel is connected… “Thrive Global’ [is] doing a lot to ensure that there’s a focus on balancing working life, balancing your personal needs and aspirations, and balancing your development spiritually, mentally, physically, making sure you stay active.”

Create a fun work environment: As part of employer branding, a work environment that is fun is vital, which is associated with Berthon et al. (Citation2005) social value. The practices are to promote a happy and positive work environment, and provide extra-curricular activities, such as community-walks, walks for a purpose, and educational, social, and sports activities. As expressed by the interviewees, the findings confirm that a fun work environment promotes employee motivation, enthusiasm, engagement, and teamwork. Chan (Citation2019) also found that workplace fun by creating a higher commitment to the organization and greater job engagement.

We have to create […] a good working environment… [and] keep them enthusiastic… the key again is [a] happy staff.

keep employees engaged in extra-curricular activities… and to motivate them … [to] have some fun.

[Given] social activities, sports activities… walk for education, and a few community-walks, we try and get together team members from our hotel and other hotels.

Compensation and benefits: This theme applies to Berthon et al. (Citation2005) economic value. Employee benefits are essential to attracting or retaining talent (Reis et al., Citation2017). As mentioned by interviewees, benefits such as travel programmes, discounted hotel rates, gratuities, rewards linked to performance, maternity leave, promotion, and opportunities to work in different locations make for an attractive workplace where employees are hesitant to leave their jobs.

When you have [been] given the package or the benefit… they [employees] will withdraw the resignation.

We have a programme called Go, which is a team-member travel programme, where you can stay [in] any [location] all over the world.

When you complete five years, the gratuity is 30 days per year. Therefore, the employees in that hotel are very hesitant to leave.

Annual salary increase [is] linked to your performance.

Increase maternity leave to 90 days… [to] make it more attractive.

Promoting people from within, where people […] genuinely deserve [it].

Advertise […] internal vacancy… encourage them… to go to London… and if they have been performing, we […] support the application.

Recognizing and rewarding employees: An organization that provides development values including employee recognition, creates career opportunities and experiences that improves its employer branding (Berthon et al., Citation2005; Chauhan & Mahajan, Citation2013). The HR personnel described different employee recognition practices (e.g., recognizing and rewarding big and small ideas, top talent, listening to employee needs, and setting up personal development plans). Interviewees expressed that such practices provide rewarding experiences and make employees feel valued and motivated.

We [HR managers] are trying to recognise our team members and […] new innovative ideas to make it a rewarding experience, and we are trying firstly to appreciate them as [our] main partners who… bring […] value to the company.

Pay attention to the smaller things that sometimes make a difference [and] goes beyond just basic recognition [by knowing] your team personally… you know who […] the key players [are]; you need to ensure they’re our top priority, ensuring they have a development plan in place… [and] understand [the] needs [of] those who are struggling.

If somebody is a top talent, we pay more attention to that team member, and we see what […] their plans for the future [are].

We have a process of PDP, which is personal development plans and… so people are motivated.

Learning opportunities: Within the application value of Berthon et al. (Citation2005) model, an employer that stimulates employees to teach others in a customer-oriented workplace enhances their employer branding (Berthon et al., Citation2005). The success of hotels is dependent on highly knowledgeable and skilled employees who cater to the requirements of hotel guests (Vokić, Citation2008). The hotels create a variety of programmes to train and develop employees through fast-track and orientation schemes, leading to employee development with a purpose, and creating a healthy and positive work environment (Berthon et al., Citation2005).

Fast-track programmes… [offer] learning and development opportunities.

Orientations to welcome new employees.

Create a healthy work environment… [by] making sure that they have efficient training. These are all not just training but development [with] a purpose.

Thus, the findings above confirm that employer-branding practices adopted by the hotels in Dubai keep employees motivated, engaged, and enhance their retention. Arruda (Citation2013) corroborates that motivated and engaged employees strengthen an organization’s brand and the destination’s competitive advantage (Iyer et al., Citation2018).

Internal branding practices

According to Sehgal and Malati (Citation2013), an organization’s internal branding practices must cultivate a workforce that reflects an organization’s set of values and goals. This study found that HR practices categorized under the internal branding theme include strategies that are employee-centric, and which treat employees like family, thus keeping them connected, building a sense of pride for working for the hotel, providing good leadership and internal communication, and empowering them (). Within each category, the findings illustrate the specific outcomes of the internal branding practices expressed by the interviewees.

Employee centric: According to Backhaus (Citation2018, p. 380), “people make the brand” and are “brand ambassadors” who can influence the brand image of the organization through positive and negative word-of-mouth.

I don’t think it’s […] the buildings; I think it’s mainly the people… I go [to] Spain, I go [to] Switzerland, I’m not even impressed because my eye [is] now […] used to Dubai, only. I’m not impressed with anything else. The element that’s missing is the people.

Family: This study confirms that employees are made to feel like they are part of a family. According to Binke (Citation2019) and Yam, Raybould, and Gordon (Citation2018), an organization built on the foundation of a family with trust and open communication improves loyalty and retention.

[A] part of, you know, a family.

Whenever I see them [employees] somewhere, it’s like you see family.

Connected: Employees should feel connected (Sartain & Schumann, Citation2008). For example, within the hotels in Dubai, HR internal branding practices are aimed at encouraging employees to collaborate and feel connected with the organization and its projects.

Collaborating on activities and events and making sure that they feel connected.

If you come to our hotel and you ask any of our employees, they will know our upcoming projects.

Sense of pride: It is important for employees to feel pride in working for the organization (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004) and employees’ positive word-of-mouth assists in building the hotel’s brand.

Sense of being a part of… a collective vision, mission, and the values.

What I’m happy about is that they feel now it’s their hotel, they want to improve it.

a sense of pride working for the [Hotel] brand.

There’s no internal marketing campaign that will compete with a workforce of 150,000, and 300,000 global employees talking about working for a hotel.

Providing good leadership and internal communication: Leadership and internal communication support and improve internal marketing and branding strategies to motivate, inform, empower, and engage employees (Cătălin, Pagalea, & Cristea, Citation2014; Kasilingam & Rajeswari, Citation2015) and retain them (Chauhan & Mahajan, Citation2013).

As a leader or […] manager, you need to leave a legacy behind. The minute you leave, your team members should tell […] people how [they] know [you were] such a fantastic person [and that they are] sad… amazing leadership [is], honestly, […] massive marketing.

Communication is key.

Empowerment: Empowering employees improves the brand image of the hotel (Aldousari, Robertson, Yajid, & Ahmed, Citation2017).

Empowerment to do things within their jurisdiction… let’s say, [as] a waiter, we are [empowering] them […] to resolve guest complaints.

In summary, the above findings help build internal branding practices that facilitate the brand-building of the hotel, which is evident from the findings above through positive word-of-mouth by the employees themselves.

Hotel and destination brand image enhancement

The following strategies discussed below focus specifically on the different HR strategies adopted by the 4- and 5- star hotels that enhance both the hotel and the destination brand image.

The findings reveal that employer and internal branding HR practices are directed as ways to influence the behavior in terms of motivating and engaging employees as representative brand ambassadors (Backhaus, Citation2018) of the hotel and the destination. This was expressed as follows by one of the interviewees who said that “we have so much internal marketing and general branding that is done for employees.”

The HR practices discussed below outline four themes () that emerged from the questions, which specifically addressed practices adopted to enhance the hotel and the destination brand.

Local Emirati culture: To enhance the hotel and destination’s brand identity and attractiveness, hotels must incorporate the unique characteristics of the local culture (Fan, Citation2014), as tourists desire a culturally enriching experience (Kim & Eves, Citation2012). The efforts to showcase Emirati culture is portrayed in many aspects of the brand and service, even if the hotel brand is not local. Employees are trained in local tourist product information. Although the hotel industry does not attract Emirati employees (Michael et al., Citation2019), the HR departments of the hotels in Dubai are working closely with Dubai’s DMO (DTCM) and the Dubai College of Tourism through its “Meydaf” programme to attract and employ more Emiratis.

[As a] European company we still add a local tradition… the local experiences…. we actually offer [such experience] to the guests.

We are trying to encourage Emiratisation so that local nationals […] represent the Emirati culture, and, actually, our hotel is designed [according to] Arabic, Arabic taste, [and] Arabic flavour… [The] Meydaf programme is to enhance localization and Emiratisation.

“The ‘Meydaf’ program provides local nationals with free tailor-made, career counseling and skill development courses including on the job internships and volunteering courses.” (dubaitourism.gov.ae)

Standardizing service and product knowledge by the DMO: The second strategy demonstrates the collaborative efforts of DTCM and the hotels to build among their employees an intimate connection with Dubai, and knowledge of the Emirati culture and destination. Such practices are aimed at service standardization. Further, DTCM provides a training programme called “The Dubai Way” for current and potential employees to connect them intimately with the city, making sure a common message is sent out across the tourism and hospitality sector.

[To ensure] quality and standards… inspectors [make regular appearances] from Dubai municipality, DTCM.

DTCM kicked off something that is right, in terms of standardising the service we offer in hospitality for guests coming into Dubai… the Dubai Way training has standardisation in understanding Dubai [and] knowing Dubai.

Intimately [knowing] Dubai […] immediately translates into knowledge for the guests… [which] makes a difference in the guest experience.

[They must] be consistent in the way they are responding [to] a particular question; so, everybody has to [provide unified answers]… [to] invest in their people.

Positive environmental initiatives: A strategy between the hotel and the DMO directed toward protecting the environment (Young et al., Citation2015) enhances positive images of both the hotel and the destination and improves pro‐environmental behavior and habits amongst employees.

We are very soon planning to have a sustainable class… conducted by DTCM.

We participate with [the] Emirates Environmental Group, which [focuses on] can-collection towards sustainability, so the whole team works… [Thus], there’s […] teamwork.

Collaborative/Collective brand experience: The HR departments of Dubai’s hotels work toward creating an impression that offers a collective brand experience, which is designed to provide positively-remembered experiences with the hotel and destination. These positive experiences, thus, can lead to return visitation and positive word-of-mouth.

This is what you [are] gonna remember when you go back home. You will not think about which specific hotel you stayed in. You would think about the whole experience; about Dubai.

Moreover, this collective strategy also aims to recruit different nationalities to help cater to guests of different nationalities, thus providing a feeling of comfort and homeliness.

[A]way from home… hire different nationalities to engage more with the multicultural guests… we have 48 nationalities… [they] can help the country [become] this big brand and [help] guests feel […] confident.

In summary, the result of the above practices, as described by one interviewee, is “to [help tourists] realize that they have landed in the best place.” Another emphasized that “Dubai has become a successful brand because of [the] existing multinational chain of hotels… it can only be experienced… This energy is a partnership, and it all starts with the vision of Sheikh Mohammed… You get this feeling like, wow, this is different… Partnership has made Dubai successful… Dubai is moving into a space where it has something for everyone.”

Marzano and Scott (Citation2009) emphasize that a successful tourism destination brand is dependent on how best it is managed and promoted through a collaborative approach by its stakeholders, like hotels. This statement is justified by the findings of this study, which confirm that the focus on HR departments working with the DMO of the destination impacts both the brand image of the hotel and the destination, in this case Dubai. Therefore, destination branding activities including collaborative work between hotels and the DMO helps to: showcase and provide visitors an Emirati cultural experience; create a unified brand experience; promote and provide positive environmental initiatives; and standardize service delivery.

Discussion and conclusions

This study explored the role of human resources in hotels and its relationship with the DMO in enhancing destination branding using data gathered from in-depth interviews with HR executives in 4- and 5- star hotels in Dubai. The study accomplished the research objectives by proposing a model that presents the two themes linked to HR practices i.e., employer branding and internal branding, the collaborative practices between the hotels and the DMO, and how they all contribute to destination branding (). This was achieved through the following three objectives.

The first objective of this study was accomplished by developing a conceptual model (see ) of HR practices within employer branding, internal branding and hotel and destination brand image enhancement. The findings reveal that HR practices within employer and internal branding adopted by the 4 and 5-star hotels in Dubai are aimed at motivating and engaging employees to be representative brand ambassadors of the hotel and the destination thus, contributing to both the enhancement of the hotel and destination brand image. Additionally, collaborative efforts between the hotels HR and the DMO contribute to destination branding.

The second objective identified the HR practices linked to employer branding using Berthon et al. (Citation2005) model and internal branding practices. Under the HR practices, the employer branding theme generated five categories, which align and concur with the values within Berthon et al. (Citation2005) model. The results contribute to the usefulness of the employer branding theory and propose new category labels for Berthon et al. (Citation2005) model that fit within the context of the hotel sector where the employees are mainly expatriate, who are unfamiliar with the local culture and lack international work experience. The findings demonstrate that the strategies behind the employer branding practices are linked to: keeping employees motivated, engaged, enthusiastic, valued and recognized; providing opportunities for skills development, new learning and rewarding experiences; enabling well-being, spiritual, mental and physical development; and providing a positive work environment that encourages employee retention. Implementing such practices improves the employee’s performance, motivation, engagement, and commitment (Barrow & Mosley, Citation2006), ultimately strengthening the employer’s brand (Lee et al., Citation2018) and contributing to the destination’s success (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2016). From the internal branding practice’s theme six categories emerged highlighting that employees are key, and they make the difference (Binke, Citation2019). The internal branding practices concentrate on: improving loyalty to the hotel; empowering employees; encouraging a sense of pride in working for the hotel; promoting collaboration; keeping employees connected and up-to-date with the hotel’s new projects and initiatives; and providing good communication and amazing leadership. Such practices can, therefore, communicate and enhance the brand image of the hotel, which is fundamental in building a positive brand image for the organization (Morokane et al., Citation2016). A positive work environment in which employees feel proud to work is reflected in their interactions with guests, which in turn can lead to a positive image of the hotel and destination, thus improving the overall destination branding.

The third objective of the study identified the collaborative practices between the HR departments of hotels and the DMO that support destination branding. Within this theme four categories emerged. These findings reveal that HR departments, which collaborate with the DMO contribute to a collaborative/collective brand experience. The Meydaf programme has helped to achieve the first objective to increase the presence of local nationals in the hotel sector. Michael et al. (Citation2019) findings note that hotels in the UAE fail to have Emirati frontline employees. Therefore, the Meydaf programme is important to the hotel sector as tourists coming to the UAE seek an authentic Emirati experience, a missing factor as most hotel employees are expatriates. The second DMO’s strategic objective contributing to the destination brand is to standardize the quality of service provided to tourists via the Dubai College of Tourism, “Dubai Way,” and to provide training programmes designed to empower employees in tourist-facing roles. This includes providing employees with relevant local information and knowledge, and includes training that is directed toward providing quality of service as some may lack international hospitality experience and also aims to standardize service across all hotels and the hospitality sector in Dubai. Third is the strategy to promote sustainable environmental initiatives further, encouraging teamwork amongst employees and sending positive images of the destination brand. Fourth, as most of the employees are expatriates, the 4 and 5-star hotels cleverly ensure that they are engaged in dealing with guests coming from different countries, therefore promoting a feeling of comfort and confidence and supporting the desired brand image. Further, as expressed by one of the interviewees a guest may not remember a particular hotel, but the service delivered across the entire hospitality and tourism sector (in this case Dubai) has to be unique and a consistent. This, therefore, conveys a positive image of the destination brand, provides a collective experience and, creates an impactful, memorable experience for tourists regarding the destination. Further, this contribution addresses the call for more empirical research on destination branding (Rather, Najar, & Jaziri, Citation2020).

To summarize, the findings support prior studies and suggest that incorporating good and effective HR practices encourages employee motivation, engagement, and retention contributing to the enhancement of the hotels’ and destination’s brand. This study contributes to the need for qualitative research on strategic HR practices by uncovering the complexity of employer and internal branding practices, and the practices of the DMO to build strategic capabilities among hotel employees to create a memorable, supportive, collaborative experience of the hotel and destination brand through efforts that improve expatriate employee loyalty, and keeps them engaged and motivated. Furthermore, such strategies attract and retain talent, help to build a linked brand and support the destination’s overall sustainable competitive advantage. These practices motivate, engage and retain employees to be representative brand ambassadors for the hotels, which influences the guest’s experience, and ultimately enhances both brands. In summary, destination branding is therefore dependent on hotel operators. Moreover, the DMO’s engagement with hotels in developing more effective practices and strategies ensure that employees are productive, motivated, and committed.

Practical implications

This study interviewed HR executives of 4 and 5- star hotels in Dubai and, therefore, has strong practical implications. For example, there should be a strong relationship between key stakeholders such as hotels and the country’s DMO. This creates immense synergy between the hotel and the destination brand to improve the images of both. Further, the findings can assist destination marketers with practical and useful information on HR practices of hotels by identifying employer and internal branding practices to enhance the brand image of the hotel and the destination. Specifically, this study has identified that there is a lack of the local community input in the hotel sector, this does not provide an authentic Emirati brand experience. Therefore, the DMO alongside the Meydaf and “The Dubai Way” programmes can consider other strategies to make the Emirati experience more inclusive in the brand.

The findings of this study highlight that senior executives should recruit more local Emirati personnel to work in the hotel sector, as this will create and enhance an authentic Emirati brand experience for visitors to Dubai. Therefore, more programs like Meydaf should be added and sustained. The study confirms that HR practices are linked to employer branding and internal branding, and this in turn contributes to destination branding. Hence there needs to be a strong and collaborative relationship between the HR departments of hotels and DTCM to build a stronger brand for Dubai. The findings suggest that organizations like, Dubai College of Tourism, DTCM and others should create and continue to support training programs for the hotel industry like the “Dubai Way” thus, empowering employees in customer service roles. The above are valuable lessons and strategies for the hotel industry that can enhance the brand image of Dubai.

Limitations and future studies

First, the study’s findings are destination-specific and, thus, may not be generalizable. Second, our sample’s informants mainly comprised HR executives from 4- and 5- star hotels in Dubai. Future studies could interview employees and use a quantitative approach to gain their perspective about HR practices and destination branding. Further, this study could be conducted in other GCC countries and beyond for generalizable conclusions. Future studies should test the destination branding model to compare if any variations exist between the human resources employer and internal branding practices that influence the destination brand and the collaborative relationship between the hotels and the DMO. Further, other stakeholders within the tourism industry such as attractions, restaurants and local transportation could be investigated.

References

- Aaker, D. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: Free Press.

- Abiola-Oke, E. (2019). The branded hotel as an element of destination branding. Academica Turistica, 12(1), 83–96. doi:10.26493/2335-4194.12.83-96

- Abukhalifeh, A., Som, A., & Albattat, A. (2013). Human resource management practices on food and beverage performance a conceptual framework for the Jordan hotel industry. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 2, 1–3.

- Aldousari, A., Robertson, A., Yajid, M., & Ahmed, Z. (2017). Impact of employer branding on organization’s performance. Journal of Transnational Management, 22(3), 153–170. doi:10.1080/15475778.2017.1335125

- Alshuaibi, A., Mohd Shamsudin, F., & Abd Aziz, N. (2016). Developing brand ambassadors: The role of brand-centred human resource management. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(Suppl. 7), 155–161.

- Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206. doi:10.1057/bm.1996.42

- Arruda, W. (2013). Three steps for transforming employees into brand ambassadors. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamarruda/2013/10/08/three-steps-for-transforming-employees-into-brand-ambassadors/#595b550e1040

- Ashton, A. (2018). How human resources management best practice influence employee satisfaction and job retention in the Thai hotel industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(2), 175–199. doi:10.1080/15332845.2017.1340759

- Aurand, T. W., Gorchels, L., & Bishop, T. R. (2005). Human resource management’s role in internal branding: An opportunity for cross‐functional brand message synergy. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 14(3), 163–169. doi:10.1108/10610420510601030

- Azzopardi, E., & Nash, R. (2016). A framework for island destination competitiveness–perspectives from the island of Malta. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(3), 253–281. doi:10.1080/13683500.2015.1025723

- Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501–517. doi:10.1108/13620430410550754

- Backhaus, K. (2018). People make the brand: A commentary: The Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management. Management Research, 16(4), 380–387.

- Bakker, A., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. doi:10.1108/13620430810870476

- Barrow, S., & Mosley, R. (2006). The employer brand: Bringing the best of brand management to people at work. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Behery, M., & Abdallah, S. (2019). Organizational environment best practices: Empirical evidence from the UAE. Journal of Research in Emerging Markets, 1(3), 27–39. doi:10.30585/jrems.v1i3.343

- Benraïss-Noailles, L., & Viot, C. (2021). Employer brand equity effects on employees well-being and loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 126, 605–613. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.002

- Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L. L. (2005). Captivating company: Dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 151–172. doi:10.1080/02650487.2005.11072912

- Binke, B. (2019). Treat your employees like valued family members: Why that’s essential. Brim Group. Retrieved from https://thebirmgroup.com/how-to-treat-employees-like-valued-members-of-a-family/

- Biswas, M., & Suar, D. (2018). Employer branding in B2B and B2C companies in India: A qualitative perspective. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 5(1), 76–95. doi:10.1177/2322093718768328

- Bowen, D., & Schneider, B. (1985). Boundary-spanning-role employees and the service encounter: Some guidelines for management and research. In J. A. Czepiel, M. R. Solomon, & C. Surprenant (Eds.), The service encounter (pp. 127–147). Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

- Burin, C., Roberts-Lombard, M., & Klopper, H. (2015). The perceived influence of the elements of internal marketing on the brand image of a staffing agency group. South African Journal of Business Management, 46(1), 71–81. doi:10.4102/sajbm.v46i1.84

- Capasso, P. (2017). Destination branding: What it is and in which way hoteliers can benefit from it. Hotelbrand Web site. Retrieved from https://hotelbrand.com/en/destination-branding-what-it-is-and-which-way-hoteliers-can-benefit-from-it/

- Cătălin, M., Pagalea, A., & Cristea, A. (2014). A holistic approach on internal marketing implementation. Business Management Dynamics, 3(11), 9–17.

- Cavanagh, S. (1997). Content analysis: Concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Researcher, 4(3), 5–16.

- Chan, S. (2019). The antecedents of workplace fun in the hospitality industry: A qualitative study. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 18(4), 425–440. doi:10.1080/15332845.2019.1626794

- Chauhan, V., & Mahajan, S. (2013). Employer branding and employee loyalty in hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Systems, 6(2), 34–43.

- Claver-Cortés, E., Pereira‐Moliner, J., José Tarí, J., & Molina‐Azorín, J. (2008). TQM, managerial factors and performance in the Spanish hotel industry. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 108(2), 228–244. doi:10.1108/02635570810847590

- De Gagne, J., & Walters, K. (2010). The lived experience of online educators: Hermeneutic phenomenology. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 6(2), 357–366.

- Denizci, B., & Tasci, A. (2010). Modeling the commonly assumed relationship between human capital and brand equity in tourism. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 19(6), 610–628. doi:10.1080/19368623.2010.493073

- Dioko, L., & So, S. (. (2012). Branding destinations versus branding hotels in a gaming destination—Examining the nature and significance of co-branding effects in the case study of Macao. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 554–563. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.07.015

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

- EXSUSDUBAI.ae. (n.d.). UAE brings efforts to attract young Emiratis to the hospitality industry. Retrieved from http://exsusdubai.ae/znews/uae-brings-efforts-to-attract-young-emiratis-to-the-hospitality-industry/

- Fan, H. (2014). Branding a place through its historical and cultural heritage: The branding project of Tofu Village in China. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 10(4), 279–287. doi:10.1057/pb.2014.28

- Fathy, E. (2018). Issues faced by hotel human resource managers in Alexandria, Egypt. Research in Hospitality Management, 8(2), 115–124. doi:10.1080/22243534.2018.1553381

- Foster, C., Punjaisri, K., & Cheng, R. (2010). Exploring the relationship between corporate, internal and employer branding. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 19(6), 401–409.

- Gaddam, S. (2008). Modeling employer branding communication: The softer aspect of HR marketing management. ICFAI Journal of Soft Skills, 2(1), 45–55.

- Gilmore, F. (2002). Branding for success. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard, & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination branding: Creating the unique destination proposition (pp. 57–65). Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Guba, E. (1978). Toward a methodology of naturalistic inquiry in educational evaluation. CSE monograph series in evaluation, 8. Los Angeles: Centre for the Study of Evaluation, UCLA Graduate School of Education, University of California.

- Hall, D. (2002). Brand development, tourism and national identity: The re-imaging of former Yugoslavia. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4), 323–334. doi:10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540081

- Hardy, A., & Gretzel, U. (2011). Why we travel this way: An exploration into the motivations of recreational vehicle users. In B. Prideaux, D. Carson (Eds.), Drive tourism: Trends and emerging markets (pp. 194–223). Oxon: Routledge.

- Hemmonsbey, J., & Tichaawa, T. (2019). Using non-mega events for destination branding: A stakeholder perspective. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 24(1), 252–266.

- Hogan, S., Loft, J., Power, M., & Schulkin, J. (2009). Referral sampling: Using physicians to recruit patients. Survey Practice, 2(9), 1–5.

- Hoppe, D. (2018). Linking employer branding and internal branding: Establishing perceived employer brand image as an antecedent of favourable employee brand attitudes and behaviours. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(4), 452–467. doi:10.1108/JPBM-12-2016-1374

- Huda, K., Haque, A., & Khan, R. (2014). Effective recruitment challenges faced by the hospitality industry in Bangladesh: A study on selected star rated residential hotels. Economia. Seria Management, 17(2), 210–222.

- Iyer, P., Davari, A., & Paswan, A. (2018). Determinants of brand performance: The role of internal branding. Journal of Brand Management, 25(3), 202–216. doi:10.1057/s41262-018-0097-1

- Jamaluddin, M., & Riyadi, A. (2018). Assessing destination branding and hotel performance of the South East Asia market. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Tourism, Gastronomy, and Tourist Destination (ICTGTD 2018), 302–311.

- Jeuring, J., & Haartsen, T. (2017). The challenge of proximity: The (un)attractiveness of near-home tourism destinations. Tourism Geographies, 19(1), 118–141. doi:10.1080/14616688.2016.1175024

- Joo-Ee, G. (2016). Minimum wage and the hospitality industry in Malaysia: An analysis of employee perceptions. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 15(1), 29–44. doi:10.1080/15332845.2015.1008396

- Kasilingam, R., & Rajeswari, B. (2015). A study on strategic dimension of employer branding in HR practices. Journal of Marketing Communications, 11(1), 31–47.

- Kim, Y., & Eves, A. (2012). Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1458–1467. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.01.015

- Kimpakorn, N., & Tocquer, G. (2009). Employees’ commitment to brands in the service sector: Luxury hotel chains in Thailand. Journal of Brand Management, 16(8), 532–544. doi:10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550140

- King, C., Grace, D., & Funk, D. (2012). Employee brand equity: Scale development and validation. Journal of Brand Management, 19(4), 268–288. doi:10.1057/bm.2011.44

- Koseoglu, M. A., Rahimi, R., Okumus, F., & Liu, J. (2016). Bibliometric studies in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 180–198. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2016.10.006

- Kowal, S., & O’Connell, D. C. (2014). Transcription as a crucial step of data analysis. In Uwe Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 64–79). London: Sage.

- Kyngas, H., & Vanhanen, L. (1999). Content analysis. Hoitotiede, 11, 3–12.

- Lee, C., Kao, R., & Lin, C. (2018). A study on the factors to measure employer brand: The case of undergraduate senior students. Chinese Management Studies, 12(4), 812–832. doi:10.1108/CMS-04-2017-0092

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ma Prieto, I., & Pilar Pérez-Santana, M. (2014). Managing innovative work behaviour: The role of human resource practices. Personnel Review, 43(2), 184–208. doi:10.1108/PR-11-2012-0199

- Malhotra, N., & Birks, D. (2006). Marketing research: An applied perspective. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Maroudas, L., Kyriakidou, O., & Vacharis, A. (2008). Employees’ motivation in the luxury hotel industry: The perceived effectiveness of human-resource practices. Managing Leisure, 13(3-4), 258–271. doi:10.1080/13606710802200969

- Marzano, G., & Scott, N. (2009). Power in destination branding. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), 247–267. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2009.01.004

- Michael, N., Reisinger, Y., & Hayes, J. (2019). The UAE’s tourism competitiveness: A business perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 53–64. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2019.02.002

- Michelson, A., & Paadam, K. (2016). Destination branding and reconstructing symbolic capital of urban heritage: A spatially informed observational analysis in medieval towns. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(2), 141–153. doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.002

- Miličević, K., Mihalič, T., & Sever, I. (2017). An investigation of the relationship between destination branding and destination competitiveness. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(2), 209–221. doi:10.1080/10548408.2016.1156611

- Morokane, P., Chiba, M., & Kleyn, N. (2016). Drivers of employee propensity to endorse their corporate brand. Journal of Brand Management, 23(1), 55–66. doi:10.1057/bm.2015.47

- Mosley, R. (2007). Customer experience, organisational culture and the employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 15(2), 123–134. doi:10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550124

- Nart, S., Sututemiz, N., Nart, S., & Karatepe, O. (2019). Internal marketing practices, genuine emotions and their effects on hotel employees’ customer oriented behaviors. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 18(1), 47–70. doi:10.1080/15332845.2019.1526509

- Paek, S., Schuckert, M., Kim, T., & Lee, G. (2015). Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50, 9–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.001

- Pereira, R., Correia, A., & Schutz, R. (2012). Destination branding: A critical overview. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 13(2), 81–102. doi:10.1080/1528008X.2012.645198

- PWC. (2018). ADAPT to the hospitality and tourism industry in the Middle East. PCW Web site. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/m1/en/issues/adapt/hospitality.html

- Qawasmeh, R. (2016). Role of the brand image of boutique hotel for customers choosing accommodation, “Le Chateau Lambousa” case study, North Cyprus. Journal of Hotel and Business Management, 5(147), 1–10.

- Rather, R., Najar, A., & Jaziri, D. (2020). Destination branding in tourism: Insights from social identification, attachment and experience theories. Anatolia, 31(2), 229–243. doi:10.1080/13032917.2020.1747223

- Reis, G., Braga, B., & Trullen, J. (2017). Workplace authenticity as an attribute of employer attractiveness. Personnel Review, 46(8), 1962–1976. doi:10.1108/PR-07-2016-0156

- Reisinger, Y., Michael, N., & Hayes, J. (2019). Destination competitiveness from a tourist perspective: A case of the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 259–279. doi:10.1002/jtr.2259

- Ren, C., & Blichfeldt, B. (2011). One clear image? Challenging simplicity in place branding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(4), 416–434. doi:10.1080/15022250.2011.598753

- Saleem, F., & Iglesias, O. (2016). Mapping the domain of the fragmented field of internal branding. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(1), 43–57. doi:10.1108/JPBM-11-2014-0751

- Sartain, L., & Schumann, M. (2008). Brand from the inside: Eight essentials to emotionally connect your employees to your business. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sehgal, K., & Malati, N. (2013). Employer branding: A potent organizational tool for enhancing competitive advantage. IUP Journal of Brand Management, 10(1), 51–65.

- Sokro, E. (2012). Impact of employer branding on employee attraction and retention. European Journal of Business and Management, 4(18), 164–173.

- Stephenson, M., Russell, K., & Edgar, D. (2010). Islamic hospitality in the UAE: Indigenization of products and human capital. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1(1), 9–24. doi:10.1108/17590831011026196

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Suttikun, C., Chang, H., & Bicksler, H. (2018). A qualitative exploration of day spa therapists’ work motivations and job satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 34, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.10.013

- Svetlacic, R., Primorac, D., & Siladev, J. (2020). Small family hotels in destination branding function. In: E. Pinto da Costa, M. Anjos, & M. Przygoda (Eds.), 52nd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development Development, Varaždin, April 2020 (pp. 345–357).

- Tasci, A. (2011). Destination branding and positioning. In Y. Wang & A. Pizam (Eds.), Destination marketing and management: Theories and applications (pp. 113–129). Wallingford, UK: CAB International.

- Tempelaar, M., & Rosenkranz, N. (2019). Switching hats: The effect of role transition on individual ambidexterity. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1517–1539. doi:10.1177/0149206317714312

- Thompson, K., Lemmon, G., & Walter, T. (2015). Employee engagement and positive psychological capital. Organizational Dynamics, 44(3), 185–195. doi:10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.05.004

- Vokić, N. (2008). The role of training and development in hotel industry success—The case of Croatia. Acta Turistica, 20(1), 9–37.

- Volgger, M., & Pechlaner, H. (2014). Requirements for destination management organizations in destination governance: Understanding DMO success. Tourism Management, 41, 64–75. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.001

- Xiong, L., King, C., & Piehler, R. (2013). ‘That’s not my job’: Exploring the employee perspective in the development of brand ambassadors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 348–359. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.07.009

- Yam, L., Raybould, M., & Gordon, R. (2018). Employment stability and retention in the hospitality industry: Exploring the role of job embeddedness. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(4), 445–464. doi:10.1080/15332845.2018.1449560

- Young, W., Davis, M., McNeill, I. M., Malhotra, B., Russell, S., Unsworth, K., & Clegg, C. W. (2015). Changing behaviour: Successful environmental programmes in the workplace. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(8), 689–703. doi:10.1002/bse.1836