Abstract

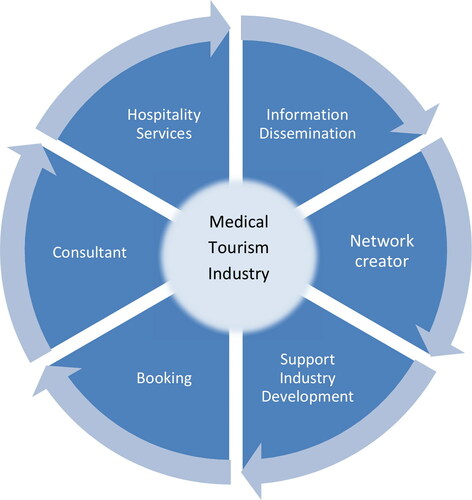

Established scholars encourage academics from different fields to make a contribution to the service research to advance, maintain relevance, and promote diversity in the service discipline. This study focuses on a novel type of intermediaries called medical tourism facilitators that assume a vital function in the medical tourism industry. Applying the case study method, the researchers collected qualitative data from three medical tourism facilitators in the Philippines. The study presents a model that includes six supplementary services, namely: information dissemination, consultation, booking, providing hospitality, network development, and support industry development.

Introduction

The growing population of sophisticated patients who travel outside their country of residence to seek combined medical and tourism services contributes to the Medical Tourism (MT) industry. The number of scientific publications, countries engaged, and estimated profit are some crucial indicators of the booming MT business (Visakhi et al., Citation2017). The promise of financial gain related to the increased demand drives hospitals to adapt to accommodate international healthcare consumers’ requests. However, not all care providers can conform to this new role and have the necessary resources to attend to unconventional patients’ needs, like visa application assistance or coordination of tourism activities during recuperation. Thus, collaborating with medical tourism facilitators (MTFs) or intermediaries (terms this paper will use interchangeably) that supply supplementary services becomes necessary for care providers and consumers (Chee et al., Citation2017). In fact, Enderwick and Nagar (Citation2011) see that the growth of the industry is due to intermediaries’ effectiveness, specifically in the case of emerging market (EM) countries where the industry is under transition. As a result, studies have been conducted focusing on MTF (e.g., Chee et al., Citation2017; Mittelstaedt et al., Citation2009), but the supplementary services they provide have remained unexplored.

In a competitive industry like MT, it is significant to provide complimentary service to enhance sensitive core products such as healthcare offerings (Lovelock, Citation1995). For example, medical tourists need to be well-informed about the medical procedure in a language that might differ from the providers’ mother tongue. Movement of medical tourists might be impeded by regulatory requirements (e.g., visas, health clearance, healthcare insurance) that the service providers are not aware of. Thus, auxiliary services are essential and necessary for service delivery. Lovelock (Citation1995) has suggested a model of service activities that identifies eight key elements or supplementary service clusters (information, consultation, order-taking, hospitality, safekeeping, exceptions, billing, and payment) that can enhance a core product and add value for customers. Nevertheless, limited studies have used this model to discuss various services. Despite only partial use of Lovelock’s model, researchers still acknowledge the potential of its contribution, since it provides a "structured approach" to understand supplementary services (Frow et al., Citation2014).

American and European findings highlight concern about the lack of regulation on MTF operation (Chee et al., Citation2017; Mittelstaedt et al., Citation2009). Some practitioners are apprehensive, because many MTFs represent different providers, have inadequate medical expertise, are relatively short-term focused, and have scant obligation in case of malpractice (Snyder et al., Citation2011). Further, it can be assumed that MTFs that operate in EM countries face difficulty because of the industry’s immaturity and exposure to institutional voids (Hyder et al., Citation2019; Khanna et al., Citation2005). However, intermediaries’ position in coordinating and linking different stakeholders can have a significant effect on the industry (Mohamad et al., Citation2012). MTFs have the control to choose which providers to promote, collaborate with, and endorse. Intermediaries’ professionalism in handling patients determines the patients’ intention to revisit and builds the country’s reputation as a destination, which affects the revenue and future of the industry (Snyder et al., Citation2011). Proper understanding of how MTFs operate is thus significant, given the role they play in the MT industry.

This paper aims to examine the role of MTFs in the MT industry in the context of EMs. To fulfill the aim, a research question is proposed: how do medical tourism facilitators operationalize in an emerging market setting? To answer this question, Lovelock’s model is used to identify supplementary services that MTFs may provide.

Literature review

Lovelock’s model and MTF activities

MTF is known by different names, like "medical broker" (Bookman & Bookman, Citation2007) "medical tourism companies" (Connell, Citation2011), "medical agents" (Gan & Frederick, Citation2011) and "medical intermediaries" (Lunt & Carrera, Citation2010), yet a standard definition is lacking. One reason may be due to MTF differences in "organizational type, modus operandi and type and range of services offered" (Chee et al., Citation2017, p. 242). The origin and geographical location of an MTF have been found to determine their size and how they operate (Connell, Citation2011). For instance, the USA has more prominent and organized intermediaries compared to European and some Asian countries, because of the higher demand for and supply of MT services in the region. While in some Asian countries, intermediaries sometimes even operate part time due to the limited market (except for in a few MT frontrunners like Thailand, Singapore, and India). For this study, we define MTFs as "organizations that offer services to assist foreign healthcare consumers in easing exposure in unfamiliar settings by dealing with medical and tourism providers." This means that besides helping with healthcare requirements, MTFs also have a crucial responsibility for patients’ adaptation to the foreign setting and developing a reliable network to different service providers.

Providing supplementary services is fundamental to customize and address the heterogeneous requirements of the patients (Berry & Bendapudi, Citation2007; Rydback & Hyder, Citation2018). In his model, Lovelock has divided eight supplementary clusters into two groups: (1) facilitating and (2) enhancing supplementary services (Lovelock & Wirtz, Citation2011). Facilitating supplementary service are those services that "aid in the use of the core product". This includes information (giving relevant information), order taking (accepting order), billing (documenting payment), and payments (assisting in settling bills). On the other hand, enhancing supplementary services are those that "add extra value for customers." This group is consist of consultation (dialogue to understand consumer need), hospitality (providing hospitality-related services), safekeeping (assisting in taking care of personal possession), and exception (handling special request). However, not all supplementary services are necessary to result in satisfactory service delivery. This is because the "nature of the product, customer requirements, and competitive practices" can also influence what supplementary services an organization offers (Lovelock & Yip, Citation1996, p. 69). It posits that service clusters overlap and collide in the case of complex core services such as the MT industry. Moreover, as Lovelock (Citation1995) initially claimed, "specialized products may require specialized supplementary elements" (p. 46). Taking Lovelock’s model, therefore, helps academics and practitioners choose what particular cluster they need to enhance or facilitate to serve demanding customers.

The use of the internet for marketing has been helpful for care providers to accelerate the internationalization of medical services (Borg & Ljungbo, Citation2018; Butt et al., Citation2019). However, the abundance of information sometimes confuses and overwhelms consumers. Gathering information from the internet cannot always guarantee transparency. Soliciting professional services like healthcare can be tricky due to asymmetric information, wherein the sellers (hospitals) are often more informed than consumers (Enderwick & Nagar, Citation2011). Thus, today’s patients are often inclined to consider advice from family and friends through word of mouth (Hyder et al., Citation2019) and recommendation of intermediaries (Lunt et al., Citation2014). To offer a one-stop solution, intermediaries coproduce offers, gather multiple service providers, and make the product available at a place and time that are convenient for healthcare consumers (Mittelstaedt et al., Citation2009). Care providers give MTFs the responsibility to customize nonmedical services that they cannot provide (Rydback & Hyder, Citation2018). Possessing the web of information, MTF can choose which providers they want to collaborate with, promote, or recommend, making them influential among stakeholders (Skountridaki, Citation2017). MTFs help lessen the patients’ vulnerabilities, moderate information asymmetry, assist in decision making, and provide moral support through the medical journey (Chee et al., Citation2017). MTFs intend to help both patients (through having the possibility to have immediate care) and healthcare providers (through taking away the burden of having a long queue) (Snyder et al., Citation2011). Nevertheless, the question is how patients know that they are dealing with a reliable MTF. Therefore, employing intermediaries is a puzzling matter for both the service providers and clients.

MTF in emerging markets

Many firms find operating in EM countries challenging due to the institutional voids or the “absence of specialized intermediaries, regulatory systems, and contract-enforcing mechanisms” (Khanna et al., Citation2005, p. 4). Missing such assistance can hinder companies’ operations. Thus, the ability of the firms to create their own connections is imperative to find reliable partners with different specializations (Hyder et al., Citation2019). Government support is vital for the growth of the MT industry, particularly in an EM. Enforcing an effective regulatory framework creates a conducive environment for supporting organizations such as intermediaries (Bookman & Bookman, Citation2007). Companies engaging in MT can take advantage of the countries’ reputation to attract patients. As an illustration, Japan claims that its world-class technological advancement is as good as its medical technology. In contrast, New Zealand uses its peaceful and attractive natural resources to encourage international patients (Connell, Citation2011). However, not all countries have the valuable positions that these two do. The MT industry is more demanding for organizations that operate in EM economies. Despite the heterogeneous characteristics, various studies have been conducted in line with Burgess and Steenkamp (Citation2006) that claim that EM settings “are natural laboratories in which theories and assumptions about their underlying mechanisms can be tested” (e.g., Hyder et al., Citation2019; Rydback & Hyder, Citation2018; Sheth, Citation2011). In this study, EM is defined as a country where firms operate in a less-developed environment with an unfavorable reputation due to inadequate infrastructure and weak regulation. This suggests that to operate in an EM context like the Philippines, MTFs face two unique challenges: (1) creation of productive collaboration with other stakeholders and (2) moderating the effect of a negative reputation about the country.

The Philippines is both classified as an EM and among the current MT destinations in Asia. Unlike the leading neighboring MT destinations like Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and India, the country is still working to organize the industry, yet receiving an increasing number of international patients (Ruggeri et al., Citation2015). Firms involved in MT in the country need to be able to work around institutional voids. Thus, understanding the function of MTFs can give a good illustration of how firms are able to manage to operate in such setting.

Concern about MTFs’ operationalization

Many scholars acknowledge the importance of intermediaries in marketing healthcare; hence, many are a concern due to their their inefficient medical background (Mittelstaedt et al., Citation2009; Snyder et al., Citation2011). In effect, some medical professionals become hesitant and apprehensive in collaborating with MTFs (Skountridaki, Citation2017). The inability to cooperate with the right providers impedes the industry’s development, especially in EM countries where a well-defined mechanism is missing. Therefore, the ability of MTFs to initiate a partnership with hospitals with an established reputation and international accreditation is essential not only to facilitate high-quality healthcare service but also to build trust and survive the industry (Gan & Frederick, Citation2011). Consumers’ reliance on intermediaries is to be taken with caution, since some might have limited interest in developing and sustaining healthcare outcomes. This is particularly alarming, as MTFs are often labeled as upstarts (Connell, Citation2011). Operating within limited regulations can mask the responsibility of intermediaries in case of a medical dispute. Playing patients’ advocates while thinking about their business interests puts MTFs in the "nexus of ethical challenges" (Snyder et al., Citation2011). Since the majority of MTFs are paid through commission, their advice is possibly driven by financial benefits and may not be in the best interest of patients. Critics question the authenticity of their medical advice, since some intermediaries operate without adequate medical competence. Thus, it can increase patients’ vulnerability (Connell, Citation2013). This raises concerns particularly for international patients who are restricted due to having illnesses, lacking medical knowledge, and being unfamiliar with to a foreign country (Rydback & Hyder, Citation2018).

The MT industry is complex and can pose some hurdles for providers as well as consumers. Thus, providing a structured outline of MTFs’ services is relevant and indispensable to understand the supplementary services, specifically those that are performed by intermediaries operating in the EM context.

Methods

Research design

A qualitative approach using case-study methodology was employed to understand how the MT industry functions in the Philippines. Using multiple case studies allows the researcher to examine replication logic, obtain richer data, understand the setting, and encapsulate the dynamic of each case (Yin, Citation2003). The empirical material was gathered from the Philippines, an EM country and MT destination. The unit of analysis used was the three active independent MTFs in the country (during 2015–2016). Some facilitators are owned by hospitals, but the researchers chose to focus on standalone local MTFs to avoid bias toward a single provider. Independent MTFs were also assumed to be more exposed to the direct effect of the context. Composite qualitative data included interviews and relevant documentation gathered through desk-based activity (e.g., reviewing documents and websites) to triangulate the data (Yin, Citation2003).

These three MTFs were almost the same in size but different in length of operation, ownership, and specialization. Diversity in cases contributed to rich data, since they provided different perspectives, levels of knowledge, and experiences about the industry. The rationale was to gather robust data as well as reduce bias (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). For example, being the first official MTF, Case 1 took the initiative and helped a government agency to create applicable criteria to classify facilitators. illustrates the cases and their MT activities. Seven supporting organizations have a connection with the MTFs included in the study (four care providers, two government agencies, and one university). For this paper, we focused on the facilitators but included all the interviews for a complete analysis (e.g., Hyder et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. Summary of the MTFs.

Data collection and analysis

Six managers directly responsible for operations were interviewed on two occasions: March to April 2015 and April 2016. Using a semi-structured interview guide gave freedom to the participants to discuss information that they felt essential to the study (e.g., Snyder et al., Citation2011). Interviews were recorded and transcribed. The interviewees read and signed consent forms before the meeting. A total of 16 interviews were conducted, 6 from MTFs and 10 from the supporting organizations. presents the interviewees’ details and the list of the sources of secondary data.

Table 2. Overview of the interviewees and data sources.

Transcription of interviews and secondary data was recorded in NVivo 11. Having various information sources facilitated the triangulation of findings and reduced bias (Creswell, Citation2013). The analysis was carried out within and across the cases pattern (Yin, Citation2003). First, data was arranged according to individual cases. Second, themes (codes/nodes) were explored and analyzed that represent each supplementary service. For instance, under the theme of consultation, there were significant MTF activities that could be segregated and labeled as two new functions, i.e., linking different organizations and contributing to the industry. These two distinctive services resulted in the two new clusters network development and support industry development. The result was integrated into the extended model. Lastly, cross-case analysis were performed by comparing and searching for replication (Yin, Citation2003). The main themes were divided into two categories: providing supplementary service and operating in an EM context.

Findings

The responses received in the study showed that MTFs in the Philippines are relatively small and new. Simplicity in the workplaces in Cases 1 and 2 suggested that they operate with limited resources. Case 3 had considerably presentable because they placed within the European Chamber of Commerce. In Cases 1 and 2, operations were almost identical (e.g., private, offer a range of medical services and packages). In contrast, Case 3 focuses on retirees’ needs and does not charge for their services. Hence some practices such as preparing the bill and collecting payment were not relevant for them.

The majority of respondents holding managerial positions are Filipinos with an educational and professional background in tourism (except the operations manager of Case 2, who is a nurse). Healthcare consumers were addressed as international patients, patients, clients, and corporate accounts. Thus, these terms are used interchangeably in this section. The exact number of patients could not be found out, though respondents collectively stated that the demand was increasing. Case 1’s founder said that they focused on diaspora, whereas the majority of clients of Case 2 were referrals from the corporate account.

Providing supplementary service

The internet was used to share information about services. Attending a convention, joining international associations, and advertising campaigns helped to link with consumers and foreign counterparts for disseminating country information. Email, Skype, and phone are the primary way of communicating with patients. The most frequent questions were about price, terms of visa, and availability of service. Although some inquiries were quite basic, the respondents assumed that it was a significant issue to make clients interested and informed. Preparation of reliable and updated data through extensive research and close collaboration with stakeholders was essential to be able to answer the inquiries promptly. For instance, a client asked if he could bring his dog with him throughout his medical journey. It was an unusual request that required checking with the hospital and hotel as well as the government agency for permission.

Through the first contact with patients, respondents were able to perceive whether patients would need an interpreter. Respondents collectively claimed that the language barrier was not a problem, since most of the clients coming were English speakers. Interpreter services were available if needed, although it would cost extra, since they needed to hire another firm to assist them. Facilitating teleconferences between patients and doctors were usually arranged by intermediaries to clear up any confusion, as well as to establish trust and rapport between them. Case 2 has an international satellite office (in Papua New Guinea) where managers personally meet patients and prearrange all requirements before traveling.

Respondents appreciated the recommendation they got from former patients/clients. However, they were concerned when former patients endorsed care providers directly to their relatives/friends. The dependability of referrals through relatives and friends should be taken with caution due to the sensitivity of medical care; diagnoses must be customized for every patient’s condition. The Case 1 cofounder also argued:

Your relative is not medically knowledgeable. Do they do proper research? They should talk to us first, because we don’t charge a service fee for any inquiry.

Empowering patients enabled them to “shop around” and look for providers that could suit their budget. However, MTFs were worried that patients would be tempted to choose price over quality when looking for medical services. As the founder of Case 1 stated:

Medical procedure is not just price … it is about your health. It can be cheap but with consequences. We are very careful in choosing partners, since [any] mistake can affect the industry.

MTFs acknowledged that patients were unlike other consumers; they were sick, unfamiliar with the system, and emotional; thus, they needed to seek a professional consultant to assist them. The growing number of clinics that employ aggressive marketing strategies to attract consumers (but have poor medical outcomes) could misguide the public, thus alarming a majority of the participants. Hence, all respondents underlined that they only worked with accredited medical providers (i.e., International Joint Commission, Accreditation Canada, International Organization for Standardization), and reputable tourism providers to ensure the quality of services. Hiring services from professionals with industry competence was an advantage. For example, there were only a few providers that have reputable malpractice insurance. Thus, using MTFs that have insider and tacit knowledge could be advantageous. Creating different medical packages (bariatric surgery, dental packages, cardiac) and wellness packages (executive check-ups) facilitated patients’ choice. On Case 2’s website, patients can even see prices and can virtually combine services and customize their travel itinerary. Since Case 3 aims to assist retirees, their service incorporated visa assistance for an extended stay and finding suitable real state property to purchase.

Upon the first contact, patients/clientele are required to send documentation (e.g., medical abstracts, laboratory results, insurance guarantee) to see which care providers they need and the mode of payment that will cover the cost. Upon receiving all the necessary documents, the MTFs assign a person to look, review, and design a “treatment plan” for the patients. These designated personnel are ideally medically inclined, yet during the interviews, respondents admitted that not all assistants have such a background. Hence, extensive training is provided to prepare these assistants before MTFs allow them to cater to patients. Tourism activities are also considered and designed for the tailored treatment plan. For instance, through consulting the physicians, they can determine what tourism activities patients are allowed to do before the medical procedure and during recuperation. Through coordinating with different providers, MTFs adjust their services and propose a treatment plan. The plan is later sent to the clients for approval.

The designated personnel meet patients from the airport and assist their transfer to accommodation or hospitals. Depending on the patient’s condition upon arrival, case managers can also act as a tourist guide if required by clients or their family members. It was highlighted that the initial itinerary could change (e.g., additional laboratory tests or more extended hospitalization might be needed) due to an unanticipated event. Thus, the assistant role became critical in notifying clients and handling matters. Working closely with patients, MTFs personnel can also provide moral support, especially in the absence of family members. These personnel are also trained to explain medical terms so patients (and their families) could understand the medical result and procedure.

At the end of the itinerary, Cases 1 and 2 help arrange medical clearance (approval that they are fit to travel) and other documents that the client might need for future reference. For some circumstances, MTFs remind patients if medical follow-up was required. Billing and payment were not directly handled by Cases 1 and 2, since their business is based on commissions. Case 3 was a nonprofit and funded by private organizations.

Operating in the EM context

Unanimously, respondents claimed that “selling the country” is the hardest part of their job (e.g., poor global ranking on the Travel and Tourism Index). Also, they stated that inadequate regulations and government ineffectiveness impede industry growth. However, they consider the conditions suitable for the present demand and are still optimistic about the future of the industry. As the cofounder of Case 1 explained:

Marketing a country is relatively easy. But marketing a country that doesn’t have an organized industry will create [its] downfall so quickly and it will be difficult to recover. So we are actually ok that we are not on the radar yet, because we are still fixing the industry right now.

The government has initiated formal collaboration among other public-private stakeholders since 2004. However, Cases 2 and 3 have not seen significant results due to the government’s undependability. Nonetheless, all believed that their informal collaboration with other providers could sustain the present demand. Familiarity with the local context (whom to trust and how to do things) gave them an edge in navigating the institutional hurdles to operate in the Philippines. Focusing on the importance of certification to officiate their function as MTFs, Case 1 sought accreditation from the government. But the agency did not have any guidelines on how to certify. Therefore, the Case 1 founder and cofounder assisted the government agency in creating instructions on how to accredit MTFs.

There is a considerable difference between private and public hospitals in the quality of services they deliver in the country, particularly in the provinces, where many retirees reside. To increase quality, Case 3 created its own accreditation standard to check the management system of hospitals. The accreditation was free, opening the possibility for small clinics and hospitals in the provinces that have limited resources to participate, since international certification is expensive. Nine out of 13 participating hospitals passed. This was to ensure that regardless of size and location, providers’ quality could fulfill patients’ needs.

Case 3, being focused on retirees, was concerned about the absence of a government agency that manages directives for the increasing number of nursing homes. Case 3 facilitated a public-private partnership project that was funded by the German government, aiming to develop and implement a quality management system for nursing homes that operate in the country. This quality management system is being implemented in six nursing homes.

Discussion

MTFs in the Philippines are small, new, and have not been around long (Connell, Citation2013). The lack of frills in the workplace and the low number of employees suggest that the Philippines, like other Asian countries, operates with limited resources due to a limited market (ibid.). Respondents revealed that demand was increasing, which corroborates with the study of the World Health Organization (Ruggeri et al., Citation2015).

Lovelock and MTF

This study showed that Lovelock’s supplementary model was useful in defining services that MTFs offer (Frow et al., Citation2014). In line with Lovelock and Yip (Citation1996), empirical evidence indicated that not all supplementary clusters of service are offered and sustained, due to the nature of the services and customer requirements. In this paper, information dissemination, consultation, booking itineraries, hospitality, and exceptions (responding to special requests) were among clusters of services highlighted by respondents, whereas safekeeping, billing, and payment were hardly mentioned or discussed. The increasing number of patients and recommendations that com through word of mouth, however, suggest that MTFs fulfill a necessary function in fulfilling foreign patients’ requirements (Hyder et al., Citation2019; Lunt et al., Citation2014).

Information is disseminated through the internet, and networking (attending international conventions, joining associations) functions to reach the global market (Borg & Ljungbo, Citation2018; Hyder et al., Citation2019). Consultation is commonly done through email, a software application (Skype), and phone calls. Preparing to answer clients’ inquiries is essential, yet for further requests, MTFs need advice from their network stakeholders (Snyder et al., Citation2011). Attending to special requests and problem solving (exception) often start from consultation across the entire process. It is reasonable to assume that although the information service cluster is vital in the initial stage, consultation is even more critical, since it encompasses dialogue with patients while preparing and developing a customized itinerary of service for a seamless medical journey. The sensitivity of the core product, condition, and requirement of customers (sick and unfamiliar), and the role of intermediaries demonstrates how the organization operationalizes (Lovelock & Yip, Citation1996). Therefore, despite the structured approach of the Lovelock’s model, supplementary clusters apparently cannot work independently; instead, they overlap.

Besides their medical condition, international healthcare consumers’ vulnerability is due to their limited medical knowledge and unfamiliarity with the foreign context (Rydback & Hyder, Citation2018). Aspects they are unfamiliar with include access to medical malpractice insurance, knowledge of providers offering the best medical outcomes, top accommodations, and alternative providers that might fit their budget. Snyder et al. (Citation2011) highlight the competence of MTFs in creating a positive patient experience. The result of this study suggests that MTFs take the hospitality service cluster to a new level by providing personal assistants who help patients through their entire medical travel. These assistants acted as patients’ advocates who offer moral support (in the absence of family members), guide tours, and aid in navigating in a complex system of medical service in an unfamiliar environment (e.g., explain medical terms, communicate with the insurance company). The pursuit of these activities indicates that intermediaries attend to international patients and fulfill functions that core providers cannot deliver, as suggested by Chee et al. (Citation2017) and Rydback and Hyder (Citation2018).

Enriching industry

As a less developed EM, the Philippines suffers from negative features such as the absence of a well-structured regulatory environment and weak government support. Bookman and Bookman (Citation2007) find that the inability of the government to create and implement a useful regulatory framework hinders intermediaries from supporting the MT industry to grow to its full potential. Knowing the tedious process of government action and responding to the need for certification, Case 1 voluntarily contributes to the groundwork for creating guidelines on how to accredit MTF. Case 3 took advantage of the connection with different stakeholders to solicit funds to finance their two projects, the independent accreditation of the hospital management system and the development of a directive on quality management systems in nursing homes (Mohamad et al., Citation2012). Instead of being distracted by unconducive settings, MTFs have learned to act using their resources (connections, know-how). Through local knowledge, these organizations have learned to resolve local issues by initiating alliances with reliable organizations and acting to improve the industry (Hyder et al., Citation2019; Khanna et al., Citation2005).

From the theoretical and empirical evidence, this study analyzed how intermediaries operated in the EM context. Extending Lovelock’s supplementary service model, we developed a model composed of six components (see ). Supplementary components such as billing, payment, and safekeeping have been found insignificant and can be placed as sub-services under information. Consultation services provide action beyond giving information, because here, active interaction happens (i.e., exceptions). Hospitality services were also observed to be vital, specifically during the beginning phase, until meeting the clients in person. Moreover, booking the itinerary (order taking) is critical, since it shows whether the initial supplementary services are a success. Empirical evidence shows that MTFs play a vital role in connecting different stakeholders’ expertise and contributing to the development of the industry’s quality. Thus, developing networks and industry support are added as MTFs’ additional functions. This investigation proposes that the MTFs can facilitate and enhance not only the core (medical) service but also the MT industry in an EM context.

Conclusions

While answering the research question, the study specified that MTFs in an EM context are found to act as information disseminators, consultation facilitators, hospitality providers, reservation agents (order takers), network developers and industry development contributors.

MTFs can be beneficial for the industry if managed and controlled correctly. Operating in the space between two complex services, medicine and tourism, MTFs require competence from both fields. Being part of the healthcare network, all personnel that handle and assist patients must have a certain degree of medical knowledge. Yet this competence was not observed in this study. As researchers claim, ambiguity with regards to MTF operations is not exclusive to EM countries (Chee et al., Citation2017; Lunt & Carrera, Citation2010; Mittelstaedt et al., Citation2009). This means that the intricacy in handling MTFs is not only based on complexity in the environmental setting, but on the industry itself. Regulating MTFs is not as straightforward as accrediting hospitals, because they serve in two different sectors. Further study to advance knowledge is therefore crucial.

This study makes several contributions. First, this research provides a new empirical insight into Lovelock’s model using a novel type of intermediaries that promote multiple services. Second, we provide an answer to the call for further investigation on what we know about facilitators’ activities (e.g., Gan & Frederick, Citation2011; Lunt & Carrera, Citation2010). Third, this research sheds light on the understanding of how MTFs operate and their potential contribution to the industry, specifically from an EM perspective. This paper is also relevant to practitioners who wish to advance knowledge on the present state of this service-driven industry, particularly on how to enhance and facilitate the core services of the MT industry. This study does not warrant comprehensive supplementary services that can fully satisfy patients’ needs, but it provides a practical starting point.

Data that was gathered from MTFs focused only on their interpretation. Although three supporting organizations were employed to substantiate their claims, it would have been interesting to include the medical tourists’ perspectives. Repeating the study in other settings (i.e., countries, industries) could provide robust data for generalization. Facilitators operating in domestic MT also need investigation and could be compared with facilitators engaged in international MT.

References

- Berry, L. L., & Bendapudi, N. (2007). Health care: A fertile field for service research. Journal of Service Research, 10(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507306682

- Bookman, M. Z., & Bookman, K. R. (2007). Medical tourism in developing countries. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Borg, E. A., & Ljungbo, K. (2018). International market-oriented strategies for medical tourism destinations. International Journal of Market Research, 60 (6), 621–634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785318770134

- Burgess, S. M., & Steenkamp, J. B. E. (2006). Marketing renaissance: How research in emerging markets advances marketing science and practice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(4), 337–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.08.001

- Butt, I., Iqbal, T., & Zohaib, S. (2019). Healthcare marketing: A review of the literature based on citation analysis. Health Marketing Quarterly, 36(4), 1–20.

- Chee, H. L., Whittaker, A., & Hong, H. (2017). Medical travel facilitators, private hospitals and international medical travel in assemblage. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 58(2), 242–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12161

- Connell, J. (2011). Medical tourism. CABI.

- Connell, J. (2013). Contemporary medical tourism: Conceptualisation, culture and commodification. Tourism Management, 34(C), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.05.009

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Enderwick, P., & Nagar, S. (2011). The comparative challenge of emerging markets: The case of medical tourism. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 6(4), 329–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17468801111170347

- Frow, P., Ngo, L. V., & Payne, A. (2014). Diagnosing the supplementary services model: Empirical validation, advancement and implementation. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(1–2), 138–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.814703

- Hyder, A. S., Rydback, M., Borg, E., & Osarenkhoe, A. (2019). Medical tourism in emerging markets: The role of trust, networks, and word-of-mouth. Health Marketing Quarterly, 36(3), 203–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2019.1618008

- Gan, L. L., & Frederick, J. R. (2011). Medical tourism facilitators: Patterns of service differentiation. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 17(3), 165–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766711409181

- Khanna, T., Palepu, K., & Sinha, J. (2005). Strategies that fit emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 84(10), 60–69.

- Lovelock, C. (1995). Competing on service: technology and teamwork in supplementary services. Planning Review, 23(4), 32–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/eb054517

- Lovelock, C., & Wirtz, J. (2011). Service marketing – People, technology, strategy. Pearson Education Limited.

- Lovelock, C., & Yip, G. S. (1996). Developing global strategies for service businesses. California Management Review, 38(2), 64–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/41165833

- Lunt, N., & Carrera, P. (2010). Medical tourism: Assessing the evidence on treatment abroad. Maturitas, 66(1), 27–32.

- Lunt, N., Horsfall, D., Smith, R., Exworthy, M., Hanefeld, J., & Mannion, R. (2014). Market size, market share and market strategy: Three myths of medical tourism. Policy & Politics, 42(4), 597–614. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655918

- Mittelstaedt, J. D., Duke, C. R., & Mittelstaedt, R. A. (2009). Health care choices in the United States and the constrained consumer: A marketing systems perspective on access and assortment in health care. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28(1), 95–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.28.1.95

- Mohamad, W. N., Omar, A., & Haron, M. S. (2012). The moderating effect of medical travel facilitators in medical tourism. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65, 358–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.134

- Ruggeri, K., Záliš, L., Meurice, C. R., Hilton, I., Ly, T. L., Zupan, Z., & Hinrichs, S. (2015). Evidence on global medical travel. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93(11), 785–789.

- Rydback, M., & Hyder, S. A. (2018). Customization in medical tourism in the Philippines. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 12(4), 486–500. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPHM-07-2017-0035

- Skountridaki, L. (2017). Barriers to business relations between medical tourism facilitators and medical professionals. Tourism Management, 59, 254–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.07.008

- Sheth, J. N. (2011). Impact of emerging markets on marketing: Rethinking existing perspectives and practices. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 166–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.4.166

- Snyder, J., Crooks, V. A., Adams, K., Kingsbury, P., & Johnston, R. (2011). The ‘patient’s physician one-step removed’: The evolving roles of medical tourism facilitators. Journal of Medical Ethics, 37(9), 530–534.

- Visakhi, P., Gupta, B. M., Gupta, R., & Garg, A. K. (2017). Health tourism research: A scientometric assessment of global publications output during 2007–16. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 7(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5530/ijmedph.2017.2.15

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case Study Research Design and Methods. (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA.