Abstract

As Customer Engagement (CE) drives brand loyalty and word-of-mouth, it is fundamental to the success of brands. Yet, while previous studies have examined the nature of CE, few have explored CE toward actors other than the focal firm or brand. Therefore, this study analyses and compares antecedents and outcomes of two types of CE: CE with a focal brand (CEF), and CE with other customers (CEC). 2031 customers of Swedish elite football were surveyed and analyzed in a SEM-model. Among others, the results indicate that CEC is more important to brand-loyalty and word-of-mouth than CEF.

Introduction

As Customer Engagement (CE) has been found to drive brand loyalty and word-of-mouth, it has become a fundamental concept for both managers and scholars (Pansari & Kumar, Citation2017). However, considering the multitude of actors whom customers can interact with, and the multiple platforms which customers may engage on, engaging customers is a tough challenge (Hollebeek et al., Citation2019). The increased attention to CE cannot only be seen in the rise of studies on this topic, but also among practitioners. For instance, the Customer Engagement-report of Braze (Citation2021) claimed that 48% of tenure brands, and 39% of young brands deem CE as a top priority to invest in.

In previous literature, scholars have used various definitions, and approaches to measure and examine the nature of CE (Brodie et al., Citation2011; Dessart et al., Citation2016). One stream of research views CE as a three-dimensional construct (cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions), while the other stream primarily is interested in the behavioral manifestations of CE (Hollebeek et al., Citation2022). What is common in both streams of research is that most studies apply a dyadic focus, i.e., are focusing on how customers engage with a focal firm (Vivek et al., Citation2014). Given that far more actors, and platforms are present in the contexts where CE occurs, this dyadic focus may only represent a small share of potential CE (Storbacka et al., Citation2016). Hence, to fully understand the nature of CE, research must go beyond the customer-firm-dyad and study other types of engagement (Fehrer et al., Citation2018). Against this background, this study will therefore go beyond this dyad and examine two different types of CE, i.e., Customer engagement with a focal firm (CEF) and Customer engagement with other customers (CEC). Thus, this study aims to contribute to existing knowledge by exploring CEC and CEF, as well as their antecedents and outcomes, and make an empirical contribution with a detailed analysis of CEC and CEF. In accordance with this aim, we put forward the following two research questions. (1) What are the main drivers of customer engagement with a firm (CEF), and customer engagement with other customers (CEC)? and (2) What are the effects of customer engagement with a firm (CEF), and customer engagement with other customers (CEC), on behavioral outcomes?

A context that is recognized for its intense interactions between customers, brands, and other actors is elite football (McDonald et al., Citation2022). Here, fansFootnote1 attend stadiums, supporter meetings and use social media to interact with each other, as well as with their team (Uhrich, Citation2021). In recent decades, elite football has been increasingly commercialized, seen for instance in the professionalization of club management and the increased interest from private investors and sponsors (Winell et al., Citation2023). This has spurred a lot of positive and negative engagement between fans, and between fans and clubs (Hill et al., Citation2018), thus making the context even more interesting from a CE-perspective. This study applies a quantitative approach and analyses survey data from 2031 respondents who, in the last three years attended at least one game of a Swedish elite football team. The survey data was analyzed through structural equation modeling and the results, among others, contribute to the current understanding of CE by manifesting the fundamental importance of CEC to outcomes of CE. As such, this study contributes to the calls for studies to examine CE beyond the traditional customer-firm-dyad (Fehrer et al., Citation2018; Storbacka et al., Citation2016), and shows the importance of CEC for brand loyalty and word-of-mouth.

Theoretical background

Contextualizing customer engagement

Theoretically, CE is often considered to occur within so called service ecosystems (Brodie et al., Citation2011). A service ecosystem can be seen as a “relatively self-contained, self-adjusting systems of resource-integrating actors connected by shared institutional arrangements and mutual value creation through service exchange” (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016, p.11). Service ecosystems spans across virtual, digital, online, offline, and physical environments, and a myriad of actors with different goals and ideals (Kunz et al., Citation2022). It is through engagement between these actors that value is co-created (Storbacka et al., Citation2016). Thus, engagement between brand and consumers, as well as engagement beyond this customer-firm dyad, are central for value-creation within service ecosystems (Laud & Karpen, Citation2017).

Customer engagement

In essence, CE is a customer’s investment of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social resources in interactions with various actors within a service ecosystem (Brodie et al., Citation2011; Hollebeek et al., Citation2019). Hence, CE can be described to cover the willingness to engage, and the actual engagement behavior which occur within a service ecosystem (Hollebeek et al., Citation2019). During the years, academic approaches to CE have differed in at least two ways (Hollebeek et al., Citation2022). First, when it comes to the actors involved, a vast majority of studies have applied a dyadic focus, i.e., focusing on the engagement between a customer and a focal brand, while few studies have focused on engagement between other actors in a service ecosystem (Morgan-Thomas et al., Citation2020).

Second, the dimensions CE have been approached in various ways. Here, one common distinction is between the multidimensional approach (Dessart et al., Citation2016), and the behaviorally oriented locus (van Doorn et al., Citation2010). The main difference between these two is that the multidimensional approach centers on four dimensions of CE, i.e., the behavioral, cognitive, social, and emotional dimensions (Brodie et al., Citation2011), while the latter is mainly concerned with the actual engagement behaviors (van Doorn et al., Citation2010). This behavioral approach has its roots in Brodie et al. (Citation2011) and their definition of CE as reflecting customers interactions with brands. As the actual interactions between customers, and between customers and brands are in focus in this study, the behavioral approach is adopted.

Fan engagement and elite sports

The intense discussions on social media regarding a team’s performances (Vale & Fernandes, Citation2018) and, or the collaboration between fans and teams in, for instance, improving the atmosphere in the arenas (Yoshida et al., Citation2014) are two examples which manifests how elite football is a peculiar context renowned for intense interactions between fans and teams (McDonald et al., Citation2022). Consequently, these peculiarities of elite football make it an appealing service ecosystem to study the more social and complex nature of CE (Vale & Fernandes, Citation2018), not the least considering how scholars highlight that the future of CE studies lies in analyzing different contexts (Brodie et al., Citation2011). provides an overview of studies having examined fan engagement in relation to other central concepts. For instance, Yoshida et al. (Citation2014) who surveyed fans of Japanese elite football, put fan engagement in relation to fan identity, positive affect, BIRGing, referral intentions and purchase intentions. Another example is Sullivan et al. (Citation2022) who surveyed how fan engagement among international fans is driven by perceptions of team authenticity.

Table 1. Studies on CE in elite sports.

Regarding definitions of CE in elite sports, Yoshida et al. (Citation2014) aligned with the behavioral approach to CE and defined fan engagement as “fans, extrarole behaviours in nontransactional exchanges to benefit his or her favourite sport team, the team’s management, and other fans” (p. 403). Similar to other contexts, fan engagement can be expressed in many ways (McDonald et al., Citation2022), and be related to other concepts in many ways (). Uhrich (Citation2014) found that one dimension of fan engagement concerns that fans are eager to discuss aspects of being a fan with others, for instance sharing information of an away trip with others in the fan community. Another expression of fan engagement is the communication on social media, which often occurs on a very frequent basis, back and forth between fans and the clubs, and between fans (Su et al., Citation2022; Yim et al., Citation2021; Yoshida et al., Citation2014). In addition, being a fan is often associated with certain rituals, thus studies such as McDonald and Karg (Citation2014) have identified that behaviors such as singing chants with other fans and watching the games at a pub are other expressions of fan engagement. These examples show the multifaceted nature of CE in elite sports, and that elite football is a service ecosystem where lot of engagement behaviors occur between fans (Yoshida et al., Citation2014).

Research model

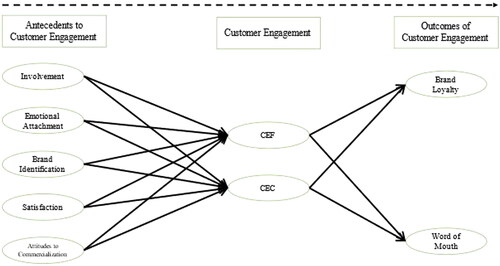

This study departs from prior studies on fan engagement (). This means that, as identified by Yoshida et al. (Citation2014), emotional attachment, and team identification are essential antecedents to CE in elite sports, and that loyalty and word-of-mouth are important outcomes. However, beyond elite sports, and beyond Yoshida et al. (Citation2014), studies on CE have shown other important antecedents (Pansari & Kumar, Citation2017). By aligning with consumer-brand relationship theory (Fetscherin & Heinrich, Citation2015) and empirical studies of CE beyond elite sports, we include involvement and satisfaction as two additional antecedents (Pansari & Kumar, Citation2017). These two are important as involvement is deemed to motivate customers to perform engagement behavior, and as satisfaction has been found to make the customer more willing to interact with others, and with the focal firm (Pansari & Kumar, Citation2017). In addition, the intensified commercialization of elite football is a heavily debated process which must be accounted for considering the calls for CE studies to be context-specific (Brodie et al., Citation2011; Hollebeek et al., Citation2019). The commercialization of elite football refers to the prioritization of financial revenues, often in favor of existing ideals and traditions (Fritz et al., Citation2017), and has been described to erode the authenticity of the sport or club (Hill et al., Citation2018). Authenticity, which in turn has been identified as an important antecedent to CE (Kumar & Kaushik, Citation2022). Thus, we include attitudes to commercialization as our final antecedent to CEC and CEF. illustrates all the 14 hypotheses for this study.

Hypotheses development

The effect of involvement on CE

Involvement is” the perceived relevance of an object based on inherent needs, values and interests” (Zaichkowsky, Citation1985, p. 2). In elite sports, involvement can be expressed as a motivational state toward a sport object, for instance a team (Funk et al., Citation2004). Involvement has several consequences, among others involved customers are more likely to invest time and energy in their interest (Funk et al., Citation2004). Thus, as Pansari and Kumar (Citation2017) argued, it is likely that involvement motivates customers to engage with their focal brand and, or other customers. In elite sports this means that the more involved a fan is, the more likely they would be to, for instance support the team, and discuss the team, with other fans (Santos et al., Citation2019). However, as few studies have explicitly separated CE into CEC and CEF, we hypothesize that:

H1a: Involvement with the team has a positive impact on CEF; H1b: Involvement with the team has a positive impact on CEC.

The impact of brand-identification on customer engagement

Identification refers to an individuals’, often a customers’, sense of connection between the self and a focal actor, often an organization (Black et al., Citation2021). Compared to involvement and its locus on personal relevance, brand-identification centers on the connection and relationship between a customer’s perceived self-identity and the brand’s identity (Stokburger-Sauer et al., Citation2012). In elite sports, it is the fit between a team identity and the self-identity of the fan that (Stokburger-Sauer et al., Citation2012). Studies have illustrated that the more a customer identifies with a brand, the more the customer is likely to engage with the brand, for instance investing their time to learn about the brand (Kaur et al., Citation2020), or interact with others on social media (Popp et al., Citation2016). Hence, customers that identify with a brand do often develop a sense of belonging to the brand and its community, which makes them more eager to engage in supporting the community, and, or the brand (Carlson et al., Citation2009). Thus, in line with previous studies, we hypothesize that:

H2a: Self-team-identification has a positive impact on CEF; H2b: Self-team-identification has a positive impact CEC.

The impact of emotional attachment with brand on customer engagement

Emotions are defined as customers “mental states that arise from cognitive appraisals of events or one’s own thoughts” (Bagozzi et al., Citation1999) In many cases, emotions are attached to a focal subject, such as a brand, or a team (Yoshida et al., Citation2014). Blasco-Arcas et al. (Citation2016) found that when customers are more emotionally attached to a brand, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that support the focal brand and the community of customers. This means that the more emotionally attached a customer is to a focal brand, or team, the more they care about the brand (Blasco-Arcas et al., Citation2016). People who care about their brand have been found to interact more often with others and providing feedback to the brand (Blasco-Arcas et al., Citation2016). In elite sports, emotions play a major role. Without the immersive and visceral nature of elite football, it would not be the massive industry it is, and fans would not be as willing to interact with their team and, or with their fellow fans (Uhrich, Citation2021). Thus, as with customers outside elite sports, fans who are emotionally attached to an elite football team, should be more highly engaged (Yoshida et al., Citation2014). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H3a: Emotional attachment with a focal team has a positive impact on CEF; H3b: Emotional attachment with a focal team has a positive impact on CEC

The impact of satisfaction on customer engagement

Satisfaction refers to a customer’s judgment that a product, experience, or service fulfilled the expectations of the customer (Oliver, Citation1980). Satisfaction is fundamental for making profits and develop both shareholder and stakeholder value, as well as making customers engage with a focal firm (Pansari & Kumar, Citation2017). More specifically, studies such as van Tonder and Petzer (Citation2018) have highlighted that when a brand manages to meet, or exceed the expectations of their customers, i.e., make their customers more satisfied, the customers are in turn more willing to interact with the brand. Thus, as satisfaction is related to willingness to interact, it is also an important antecedent to CE (Pansari & Kumar, Citation2017). In elite sports, there are many different components that can make fans satisfied, not only the results on the pitches, but also elements such as game atmosphere, social connections with others, events before and after the game, and communication on social media (Kucharska et al., Citation2020). In line with previous literature, we thereby hypothesize that:

H4a: Satisfaction of being a fan has a positive impact on CEF; H4b: Satisfaction of being a fan has a positive impact on CEC.

The impact of commercialization on customer engagement

Studies have found that perceptions of authenticity have a positive effect on CE (Kumar & Kaushik, Citation2022), this since brand authenticity can reinforce the connection between a brand identity and the customers self-identity, thereby driving CE (Kumar & Kaushik, Citation2022). However, the contextual conditions for how brand authenticity is created, or eroded, and how this impacts CE remains vague (Morhart et al., Citation2015). Therefore, and considering that scholars such as Brodie et al. (Citation2011), and McDonald et al. (Citation2022) highlight the need for CE-studies to understand its context, the commercialization of elite football provides a good example. Commercialization refers to the increased prioritization of financial revenues among organizations and in elite football most papers on this topic have argued that it erodes the role of the fan, and the perceived authenticity of the team (Winell et al., Citation2023). Yet, the understanding of how CE is impacted by this process remains vague (Winell et al., Citation2023). To explore this, we hypothesize that:

H5a: Negative attitudes to the commercialization of the league and/or team negatively impact CEF; H5b: Negative attitudes to the commercialization of the league and/or team negatively impact CEC

Outcomes of customer engagement

The impact of customer engagement on WOM

Word-of-Mouth (WOM) implies the referrals customers are making for a brand or an experience (Anderson, Citation1998). For brands it is important to involve customers in WOM as it motivates others to join the customer base and to engage with the brand (Vivek et al., Citation2014). This means that engaged customers, whom for instance are interacting extensively with the focal brand, are more likely to talk about the brand to others, as well inviting others to join the community of customers (Vivek et al., Citation2014). In elite football, WOM entails for instance that fans talk about the experiences of following a team (Asada & Ko, Citation2016). Thus, WOM, is considered a result of fans being more engaged with the brand or being an engaged member of the fan community (Yoshida et al., Citation2014). In line with the previous literature, we therefore hypothesize that:

H6a: CEF has a positive impact on WOM-behaviours; H6b: CEC has a positive impact on WOM-behaviours.

The impact of customer engagement on brand loyalty

Brand loyalty is referred to as the commitment of a customer to repurchase and, or repatronize a certain product, service, or brand in the future (Oliver, Citation1999). Thus, brand loyalty is distinct from CE as it involves behavioral decision-making and often focuses on a repurchases, for instance attending future games of a beloved team (Yoshida et al., Citation2014). Several studies have identified the positive effects of CE on brand loyalty (Fernandes & Esteves, Citation2016). These studies have shown that highly engaged customers have a closer relationship with their team and thus, they are more motivated to remain as customers (Vivek et al., Citation2014), for instance continuing to attend games (Fernandes & Esteves, Citation2016). In line with this literature, we thereby hypothesize that:

H7a: CEF has a positive impact on brand loyalty; H7b: CEC has a positive impact on brand loyalty.

Method

Sample

To analyze antecedents and outcomes of CEC and CEF in elite football, individuals who had attended at least one game in the top-division of Swedish men’s elite football (called Allsvenskan) were surveyed. The rationale for entering the Swedish elite football context is based on how it, despite that teams are far less competitive than teams in major European leagues, such as England and Italy, is often renowned for its large communities of heavily engaged fans (Sund, Citation2014). Moreover, due to how Swedish law prohibits private investors from taking over more than 49% of the clubs, the “Swedish way” of commercializing elite football is rather unique in modern elite sports (Sund, Citation2014). In total, 10 000 individuals who supported five different teams in Allsvenskan, were invited to fill in the online survey. Of the 10 000 invitations (2000 invitations per team), 2031 questionnaires were fully completed (i.e., 20.3% response rate.

Measures

All items () were assessed using Likert scales, ranging from (1) completely disagree; to (5) completely agree. For involvement, the 10-item scale of Zaichkowsky (Citation1985) was used. A three-item scale, adapted from Yoshida et al. (Citation2014), was used to measure emotional attachment. Brand (team) identification was measured through a three-item scale adapted from Trail et al. (Citation2003) and satisfaction was adapted from Oliver (Citation1980). Measures of attitudes to commercialization were formed based on the items of Fritz et al. (Citation2017) and their study on commercialization and authenticity. To measure CEC and CEF, Yoshida et al. (Citation2014) and their behavioral operationalization of fan engagement served as the main inspiration. This adaptation of CE to elite sports accounts for the deep psychological connections between fans and their teams (McDonald et al., Citation2022). As we were particularly interested in examining CEF and CEC, the two dimensions of management cooperation and prosocial behavior were used. CEF is here the disposition and behaviors among the fans that contributes to the managerial work in the club, for instance participating in creating good atmospheres at stadiums (Edensor, Citation2015). CEC encompasses fans socialization with other fans, such as discussing the team on social media (Vale & Fernandes, Citation2018). Finally, for the outcomes of CE, measures of loyalty were adapted from Bauer et al. (Citation2008), and word-of-mouth through Jahn and Kunz (Citation2012). Some items were excluded due to weak loadings (below .5) and, or issues with cross-loadings. In total, 36 items were included (). To increase the validity and reliability of the analysis, the sample was thereafter randomly divided into two groups, where the first half of the sample was used for the CFA, and the other half for the SEM (Kyriazos, Citation2018).

Table 2. Measurement model.

Data analysis

Measurement model

The confirmatory factor analysis of the included items () and constructs was deemed satisfactory (χ2 = 1999.98; df = 538; χ2/df = 3.72; p =.000; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; IFI =.94; Standardized RMR = .047; RMSEA = .056) (Cho et al., Citation2020). To achieve construct validity, some error terms were correlated, such as the items forming CEC. Furthermore, all the standardized factor loadings (SL) were larger than .6, thus indicating construct reliability (Hair Jr et al., 2014). The reliability of the scales was further reinforced as the composite reliability for each scale was above .7, and as the average variance extracted for each scale was greater than .5 (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988).

Regarding discriminant validity, several tests exist. In this study, the principles for assessing discriminant validity are based on the HTMT-criterion, which is argued to be more sensitive to discriminant validity than the Fornell-Larcker-criterion (Henseler et al., Citation2015). According to Henseler et al. (Citation2015), the calculated HTMT-ratios need to be below .9 to indicate discriminant validity at a sample size above 1000. None of the HTMT-ratios from this survey were above .9, thus it indicated no severe issues with discriminant validity. Testing for common method bias is another important check before proceeding with the structural model. Here we followed the principles of the Harmans single-factor-test which stipulates that the single factor must account for less than 50% of the total variance to indicate that there are no issues with common method bias (Podsakoff & Organ, Citation1986). The results of our test indicated no common method bias as the cumulative percentage of variance was below 40%.

Structural model

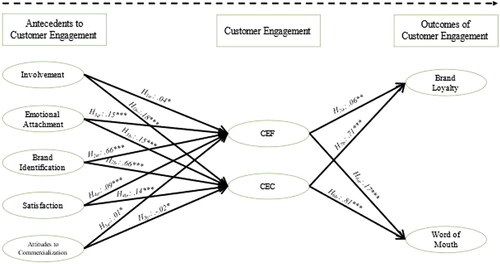

As with the measurement model, the structural model exhibited an acceptable goodness of fit, especially as the sample size was above 500 (χ2 = 2382.61; df = 550; χ2/df = 4.33; p =.000***, GFI = .87, TLI = .91; CFI = .93, RMSEA = .058; Standardized RMR = .0552; NFI = .920)Footnote2 (). The model ( and ) supports 7 out of 10 hypotheses on antecedents to CEF and CEC (p < .05). Those that are not supported, are the effects of involvement on CEF (p = .49), and on attitudes to commercialization and CEF (p = .14), and CEC (p = .95). Regarding the standardized estimates and the relative impacts of involvement, brand identification, emotional attachment, and satisfaction on CEC and CEF, some are more influential than others. For CEF, brand identification (β = .36) is the most influential. For CEC, brand identification is the most important antecedent (β = .42). Among outcomes of CEC and CEF, all the four hypotheses are supported (). However, even though all path coefficients are statistically significant, the effect of CEC on brand loyalty (β = .94) and WOM (β = .57) is larger than the effect of CEF on brand loyalty (β = .02) and WOM (β = .10).

Table 3. Hypotheses and structural model.

Discussion and conclusions

By going beyond the customer-firm-dyad and exploring CEC and CEF simultaneously, this study advances current understanding of CE in both a theoretical and managerial way. The following section is structured so that we first discuss the results in the light of previous studies on antecedents to, and outcomes of CE. Thereafter we discuss how these results advances the current understanding and theorization of CE. Following, we provide how brand managers, within and outside elite sports, may use the results of this study in their work. Finally, we discuss the limitations of this study, as well as provide certain suggestions for future research.

Antecedents to CEF and CEC

Within the literature on CE, several important antecedents of CE have been identified (Pansari & Kumar, Citation2017). However, as most studies have been focused on the engagement that takes place between firms and their customers (CEF), it has been unclear to what extent these antecedents also predict engagement behaviors where customers engage with other customers (CEC) (Morgan-Thomas et al., Citation2020). The results of this paper largely confirm existing knowledge in how satisfaction, brand identification and emotional attachment all have positive effects on customer engagement with a focal brand (Rather et al., Citation2019). By going beyond this dyad, the current results confirm that these antecedents are also important for customer engagement with other customers. However, involvement, which previous studies have identified as important to CE (Brodie et al., Citation2011), seem to only have a positive effect on CEC, not on CEF. The reason for this relationship could be that customers, in this case fans, who are more involved are more willing to interact, and to co-create the experience of being a customer (Brodie et al., Citation2011), in other words, the more involved fans are more eager to engage with other peers (Santos et al., Citation2019), not the focal firm.

Furthermore, as CE is context-specific (Brodie et al., Citation2011) and as the context for this study was elite football, we had an explicit focus on the heavily debated process of elite football commercialization (Winell et al., Citation2023). Commercialization is often depicted to erode authenticity (Fritz et al., Citation2017), which in turn may erode CE (Kumar & Kaushik, Citation2022). As the review in Winell et al. (Citation2023) showed, many researchers are critical toward the effects of elite sport commercialization on fans. However, our results, performed in a Swedish elite football context where the clubs are owned by the fans (Sund, Citation2014), show contradicting results. As Attitudes to commercialization were not influencing CEC, or CEF, it seems that fans who are negative to the commercialization of elite football do not engage less. An explanation to this non-existing relationship may be context dependent. When fans deem themselves as owners of the club, or are members of the club, they take part in decisions concerning commercial elements (Sund, Citation2014). Thus, it is less likely that this commercialization of elite football negatively impacts CE.

Outcomes of CEF and CEC

Previous research has highlighted that when customers are more engaged, they will also remain more loyal (Vivek et al., Citation2014), and invite others to become customers and, or fans (Yoshida et al., Citation2014). In separating CE into CEC and CEF we find that it is CEC that is the most important predictor of brand loyalty and WOM. As Vivek et al. (Citation2014) argue, CE with a firm is still important to these two, yet it seems that it is the social engagement with other peers that are the main driver of brand loyalty and word-of-mouth. A possible explanation to why this could be is that the engagement which occurs between customers often is more immersive and social, than within the traditional customer-firm-dyad (Fehrer et al., Citation2018). Therein, the immersivity of this type of CE, keeps customers within the community, i.e., remaining loyal, as well as makes them invite others to the community.

Theoretical contribution

By examining antecedents to, and outcomes of CEC and CEF separately, this study contributes to the current understanding of CE in several ways. The distinction between CEC and CEF allows us to achieve a more in-dept understanding of CE which goes beyond the customer-firm-dyad (Fehrer et al., Citation2018; Storbacka et al., Citation2016). The results contribute to the ongoing discussions of CE with two important results. First, involvement should be accounted for as a predictor to why customers engage with other customers, but not with the focal brand. This is important to the understanding of CE as the engagement which occurs between customers seem to be driven slightly different than engagement between customers and firms. Secondly, this study shows that the social nature of CEC (McDonald & Karg, Citation2014; Uhrich, Citation2021) is more important to brand loyalty and word-of-mouth, than CEF. Thus, the results of this study contribute to the understanding of CE by manifesting that the more immersive engagement occurring between customers must be accounted for since it has such high influence on outcomes of CE. In all, this study has shown that CE must be understood beyond the traditional dyad (Fehrer et al., Citation2018), not the least since it CEC that seems to be fundamental to central outcomes of CE.

Managerial Implications

From a managerial perspective, the results amplify the need for brands to ensure that their customers are engaging with each other, to attain a loyal customer base who are willing to invite others. Previous CE literature have to some extent pointed in this way already (Yoshida et al., Citation2014), but this study confirms this with empirical results. In elite sports, examples of initiatives that fosters CEC could be creating online forums where fans interact around team-related topics (Vale & Fernandes, Citation2018), events such as tailgatingFootnote3 prior to home games (Bradford & Sherry, Citation2015) and, the creation of fanzones where fans can watch games, meet other fans, and socialize (Frew & McGillivray, Citation2008). The emphasis on CEC is also relevant for managers working outside elite sports, for example in industries characterized by highly involved customers. An example to foster CEC outside this study’s context, could be to create conventions and consumer fairs, such as Comic-Con, where likeminded consumers meet and engage with each other around a certain interest, in this case comic books and superheroes (Kohnen, Citation2014). Two other examples could be taken from (1) LEGO and their creation of platforms to make LEGO-customers be creative and share their way of using the bricks with other customers (Laud & Karpen, Citation2017) and (2), running communities where customers can gather physically and socialize around a certain interest, as in the study of The Hogwarts Running Club and the Harry Potter fans who engage with each other while running (Lizzo & Liechty, Citation2022). To add, the non-significant effects of involvement on CEF, indicates that for managers who are investing resources to raise involvement among their customers, it is important that the main goal of theirs should be to ensure customers engaging with each other, for instance interacting on social media.

Limitations and future research

As with all studies, several limitations must be considered. First, the sample was limited to spectators of Swedish men’s elite football and thus results may differ if other service ecosystems are examined. As Brodie et al. (Citation2011) argue for the contextual conditions of CE, future research should benefit from assessing CEC and CEF in service ecosystems with customers of varying levels of involvement, satisfaction and, or emotional attachment. Also, considering the current development of literature on service ecosystems and actor engagement (Storbacka et al., Citation2016), assessing engagement between other actors than customers and firms would contribute to further integration of service ecosystems to the CE-literature. Thus, adding, and comparing, other types of engagement is highly relevant, for instance examining how CE with digital actors (chatbots, virtual agents etc.) differ regarding CE with other customers. Some of the AVE-values (associated with CEC, loyalty to the team, and attitudes toward commercialization) () are acceptable, but also borderline cases since they are very close to .5. This is as well a limitation and future studies should attempt to refine the scales used in this study.

Notes

1 Fans are in this paper referred to as individuals with a psychological connection to one or several team(s), sport(s), and/or athlete(s) (Yoshida et al., Citation2014).

2 The principles for the fit indices are based on Hair Jr et al. (2014) and Cho et al. (Citation2020). The sample size is large in this study (>500), thus our GFI is lower than .9. However, as the other fit indices are acceptable the overall model is deemed as acceptable.

3 ”Tailgating” are social events, often around elite sport games, where fans meet and eat on the parking lots outside the stadiums (Bradford & Sherry, Citation2015).

References

- Anderson, E. W. (1998). Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467059800100102

- Asada, A., & Ko, Y. J. (2016). Determinants of word-of-mouth influence in sport viewership. Journal of Sport Management, 30(2), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0332

- Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399272005

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Bauer, H. H., Stokburger-Sauer, N. E., & Exler, S. (2008). Brand image and fan loyalty in professional team sport. Journal of Sport Management, 22(2), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.22.2.205

- Black, H. G., Jeseo, V., & Vincent, L. H. (2021). Promoting customer engagement in service settings through identification. Journal of Services Marketing, 35(4), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-06-2020-0219

- Blasco-Arcas, L., Hernandez-Ortega, B. I., & Jimenez-Martinez, J. (2016). Engagement platforms: The role of emotions in fostering customer engagement and brand image in interactive media. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 26(5), 559–589. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-12-2014-0286

- Bradford, T. W., & Sherry, J. F. (2015). Domesticating public space through ritual: Tailgating as Vestaval. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(1), 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv001

- Braze. (2021). 2021 global customer engagement review.

- Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for. Research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703

- Carlson, B. D., Donavan, D. T., & Cumiskey, K. J. (2009). Consumer-brand relationships in sport: Brand personality and identification. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(4), 370–384. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550910948592

- Cho, G., Hwang, H., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2020). Cutoff criteria for overall model fit indexes in generalized structured component analysis. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 8(4), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-020-00089-1

- Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2016). Capturing consumer engagement: Duality, dimensionality and measurement. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5-6), 399–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1130738

- Edensor, T. (2015). Producing atmospheres at the match: Fan cultures, commercialisation and mood management in English football. Emotion, Space and Society, 15, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2013.12.010

- Fehrer, J. A., Woratschek, H., Germelmann, C. C., & Brodie, R. J. (2018). Dynamics and drivers of customer engagement: Within the dyad and beyond. Journal of Service Management, 29(3), 443–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-08-2016-0236

- Fernandes, T., & Esteves, F. (2016). Customer engagement and loyalty: A comparative study between service contexts. Services Marketing Quarterly, 37(2), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332969.2016.1154744

- Fetscherin, M., & Heinrich, D. (2015). Consumer brand relationships research: A bibliometric citation meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.010

- Frew, M., & McGillivray, D. (2008). Exploring hyper-experiences: Performing the fan at Germany 2006. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 13(3), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080802310223

- Fritz, K., Schoenmueller, V., & Bruhn, M. (2017). Authenticity in branding – Exploring antecedents and consequences of brand authenticity. European Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 324–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2014-0633

- Funk, D. C., Ridinger, L. L., & Moorman, A. M. (2004). Exploring origins of involvement: Understanding the relationshissp between consumer motives and involvement with professional sport teams. Leisure Sciences, 26(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400490272440

- Hair, J. F.Jr., Black, W. C., Anderson, R. E., & Babin, B. J. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hill, T., Canniford, R., & Millward, P. (2018). Against modern football: Mobilising protest movements in social media. Sociology, 52(4), 688–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038516660040

- Hollebeek, L. D., Sharma, T. G., Pandey, R., Sanyal, P., & Clark, M. K. (2022). Fifteen years of customer engagement research: A bibliometric and network analysis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(2), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2021-3301

- Hollebeek, L. D., Srivastava, R. K., & Chen, T. (2019). S-D logic–informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(1), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0494-5

- Huettermann, M., Uhrich, S., & Koenigstorfer, J. (2019). Components and outcomes of fan engagement in team sports: The perspective of managers and fans. Journal of Global Sport Management, 0(0), 1–32.

- Jahn, B., & Kunz, W. (2012). How to transform consumers into fans of your brand. Journal of Service Management, 23(3), 344–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231211248444

- Kaur, H., Paruthi, M., Islam, J. U., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2020). The role of brand community identification and reward on consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty in virtual brand communities. Telematics and Informatics, 46, 101321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101321

- Kohnen, M. (2014). ‘The power of geek’: fandom as gendered commodity at Comic-Con. Creative Industries Journal, 7(1), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2014.892295

- Kucharska, W., Confente, I., & Brunetti, F. (2020). The power of personal brand authenticity and identification: Top celebrity players’ contribution to loyalty toward football. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(6), 815–830. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-02-2019-2241

- Kumar, V., & Kaushik, A. K. (2022). Engaging customers through brand authenticity perceptions: The moderating role of self-congruence. Journal of Business Research, 138, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.065

- Kunz, R. E., Roth, A., & Santomier, J. P. (2022). A perspective on value co-creation processes in eSports service ecosystems. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 12(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-03-2021-0039

- Kyriazos, T. (2018). Applied psychometrics: The 3-faced construct validation method, a routine for evaluating a factor structure. Psychology, 09(08), 2044–2072. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.98117

- Laud, G., & Karpen, I. O. (2017). Value co-creation behaviour – Role of embeddedness and outcome considerations. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(4), 778–807. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-04-2016-0069

- Lee, M. A., Kunkel, T., Funk, D. C., Karg, A., & McDonald, H. (2020). Built to last: Relationship quality management for season ticketholders. European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(3), 364–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2019.1613438

- Lizzo, R., & Liechty, T. (2022). The Hogwarts Running Club and sense of community: A netnography of a virtual community. Leisure Sciences, 44(7), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1755751

- McDonald, H., Biscaia, R., Yoshida, M., Conduit, J., & Doyle, J. P. (2022). Customer engagement in sport: An updated review and research agenda. Journal of Sport Management, 36(3), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2021-0233

- McDonald, H., & Karg, A. J. (2014). Managing co-creation in professional sports: The antecedents and consequences of ritualized spectator behavior. Sport Management Review, 17(3), 292–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.07.004

- Morgan-Thomas, A., Dessart, L., & Veloutsou, C. (2020). Digital ecosystem and consumer engagement: A socio-technical perspective. Journal of Business Research, 121(January), 713–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.042

- Morhart, F., Malär, L., Guèvremont, A., Girardin, F., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.11.006

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4_suppl1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252099

- Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer engagement : The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0485-6

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

- Popp, B., Wilson, B., Horbel, C., & Woratschek, H. (2016). Relationship building through Facebook brand pages: The multifaceted roles of identification, satisfaction, and perceived relationship investment. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(3-4), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2015.1095226

- Rather, R. A., Hollebeek, L. D., & Islam, J. U. (2019). Tourism-based customer engagement: the construct, antecedents, and consequences. The Service Industries Journal, 39(7-8), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1570154

- Santos, T. O., Correia, A., Biscaia, R., & Pegoraro, A. (2019). Examining fan engagement through social networking sites. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 20(1), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-05-2016-0020

- Stander, F. W., Van Zyl, L. E., & Motaung, K. (2016). Promoting fan engagement: An exploration of the fundamental motives for sport consumption amongst premier league football spectators. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 26(4), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2016.1208920

- Stokburger-Sauer, N., Ratneshwar, S., & Sen, S. (2012). Drivers of consumer-brand identification. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.06.001

- Storbacka, K., Brodie, R. J., Böhmann, T., Maglio, P. P., & Nenonen, S. (2016). Actor engagement as a microfoundation for value co-creation. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3008–3017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.034

- Su, Y., Du, J., Biscaia, R., & Inoue, Y. (2022). We are in this together: Sport brand involvement and fans’ well-being. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(1), 92–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1978519

- Sullivan, J., Zhao, Y., Chadwick, S., & Gow, M. (2022). Chinese fans’ engagement with football: Transnationalism, authenticity and identity. Journal of Global Sport Management, 7(3), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2021.1871855

- Sund, B. (2014). Fotbollsindustrin - andra upplagan. Nomen Förlag.

- Trail, G. T., Fink, J. S., & Anderson, D. F. (2003). Sport spectator consumption behavior. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(1), 1–17.

- Uhrich, S. (2014). Exploring customer-to-customer value co-creation platforms and practices in team sports. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.865248

- Uhrich, S. (2021). Antecedents and consequences of perceived fan participation in the decision making of professional European football clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(4), 504–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1757734

- Vale, L., & Fernandes, T. (2018). Social media and sports: Driving fan engagement with football clubs on Facebook. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 26(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2017.1359655

- van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375599

- van Tonder, E., & Petzer, D. J. (2018). The interrelationships between relationship marketing constructs and customer engagement dimensions. The Service Industries Journal, 38(13-14), 948–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1425398

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2016). Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3

- Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., Dalela, V., & Morgan, R. M. (2014). A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 22(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679220404

- Winell, E., Armbrecht, J., Lundberg, E., & Nilsson, J. (2023). How are fans affected by the commercialization of elite sports? A review of the literature and a research agenda. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 13(1), 118–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-11-2021-0135

- Yim, B. H., Byon, K. K., Baker, T. A., & Zhang, J. J. (2021). Identifying critical factors in sport consumption decision making of millennial sport fans: Mixed-methods approach. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(4), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1755713

- Yoshida, M., Gordon, B., Nakazawa, M., & Biscaia, R. (2014). Conceptualization an measurement of fan engagement: Empirical evidence from a professional sport context. Journal of Sport Management, 28(4), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0199

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1086/208520