ABSTRACT

Young people in rural, regional, and remote communities experience high levels of mental distress. Health services in rural and remote communities are also poorer in quality. Hence, it is critical to understand how social work can help young people in these areas access mental health supports. This scoping review identifies what enables and hinders access to mental health services for young people in rural, regional, and remote areas of Australia and Canada. Twenty-two studies published between 2018 and 2022 were included and analyzed. Findings highlight the need for social workers to reduce peer-stigmatization of mental illness and foster community collaboration.

Introduction

Approximately one-in-seven adolescents across the world experience mental distress or live with a mental disorder at any one time (World Health Organization, Citation2021). However, the prevalence of significant mental distress is notably higher for young people in Australia and Canada. Just over 20% of adolescents in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], Citation2021) and Canada (Canadian Paediatric Society, Citation2023) experience either high or very high levels of psychological distress. In response, both the Australian (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, Citation2021) and Canadian (Government of Canada, Citation2023) governments have pledged funding increases for services to support youth mental health. Yet children and adolescents in rural areas of Australia experience poorer mental health outcomes compared to young people living in urban centers (I. Peters et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the suicide rates of young Australians and Canadians living in rural and remote communities are two to three times higher than their urban counterparts (Barry et al., Citation2020; Ivancic et al., Citation2018).

Social workers in rural, regional, and remote mental health settings provide general counseling and evidence-based talking therapies to young people, with a distinct focus on how social determinants impact individual and community mental wellbeing (Novik et al., Citation2022; Smith, Citation2022). As social workers use psychosocial modalities in their clinical practice (Coulshed & Orme, Citation2018), they can advocate for improving the responsiveness of mental health services in rural and regional communities (Howard et al., Citation2016). The impact of social work practice in rural and regional communities has increased over time, as the number of social workers practicing in these areas has grown (Doxey & McNamara, Citation2015). This has led to the formation of social work roles targeting rural young people in school settings (Gartshore et al., Citation2018; Maple et al., Citation2018). Importantly, social workers advocate for the voices of people with lived experience of mental illness to lead discussion in transforming mental health care practices (Bland et al., Citation2021; Golightley & Goemans, Citation2020), especially in youth mental health settings (Beckwith et al., Citation2021; Ward, Citation2015).

Despite the growth of social work practice in rural, regional, and remote communities a preliminary review of Australian and Canadian literature from 2007 to 2017 in Google Scholar identified only one article from rural Canada (Davis, Citation2013) that examined social work practice in youth mental health settings. Although there is some social work research about mental health practice with young people in urban contexts (Beckwith et al., Citation2021; Ward, Citation2015) there is a distinct absence of literature discussing social work mental health practice with rural, regional, and remote young people.

While there is increasing recognition of the important role social workers play in rural, regional, and remote communities (Doxey & McNamara, Citation2015; Howard et al., Citation2016), it remains unclear how social work can improve mental health service access for young people in these areas. Given the increase in the number of young people diagnosed with a mental illness since the COVID-19 pandemic (Hen et al., Citation2022; Kauhanen et al., Citation2022) it is critical to understand how social workers can promote access to youth mental health services in regional, rural and remote areas. This study aimed to identify what enables and hinders access to mental health services for young people in rural, regional, and remote areas of Australia and Canada through a scoping review. The discussion section outlines how the findings can inform social work practice in improving access to mental health services for young people in rural areas.

Methods

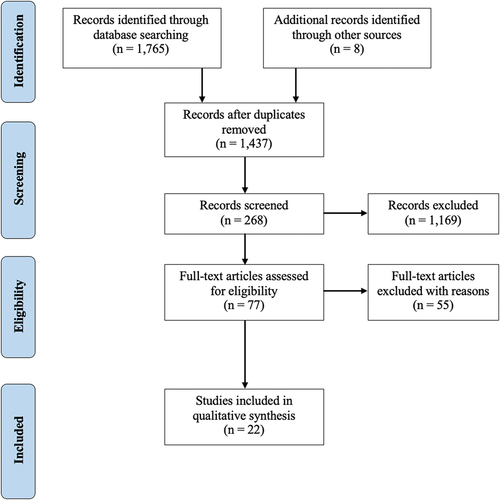

This review follows the framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and enhanced by Levac et al. (Citation2010). A scoping review was chosen to summarize contemporary evidence from multiple study designs to address questions which are too broad to answer within traditional systematic reviews (M. D. J. Peters et al., Citation2021). This research incorporated the first five steps of the framework: (i) selecting the research question; (ii) identifying relevant literature; (iii) analyzing and selecting the studies; (iv) charting the data; and (v) collating, summarizing, and disseminating results (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used for selection of the literature (Tricco et al., Citation2018; see ).

Establishing the research question

This study focuses on determinants that impact young people’s access to mental health supports in regional, rural, and remote areas. Access is a complex concept that must be clearly defined. In this research “accessibility” is defined in terms of equitable and just access to health care (Gulliford, Citation2013). As Gulliford (Citation2013) argues, health care access is informed by both the just distribution of health care for all, and the implementation of processes that promote the fair accessibility of health care. This study also recognizes the five key dimensions of health care accessibility for service users: i) availability; ii) accessibility; iii) accommodation; iv) affordability; and v) acceptability and asserts that Gulliford’s (Citation2013) definition of accessibility must be realized through these dimensions (Khanassov et al., Citation2016; Levesque et al., Citation2013; Penchansky & Thomas, Citation1981).

Furthermore, the preliminary review of literature suggested a lack of existing contemporary social work literature on the topic area. Development of the research question was subsequently broadened to include literature from all health-related disciplines. Therefore, the following question was developed for this scoping review: what enables and hinders access to mental health services for young people in rural, regional, and remote areas of Australia and Canada?

Identifying relevant studies

Articles were included as findings if they were: i) published in English; ii) published between 2018 and 2022; iii) focussed on youth mental health service accessibility in rural, regional, or remote areas; iv) studies or reports conducted in Australia or Canada; v) studies that included the perspective of both service providers and young people in rural, regional, and remote contexts; vi) quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method studies and reports; and vii) peer-reviewed articles, theses, dissertations, and gray literature. Studies were excluded if they were: i) books, ebooks, or book chapters; ii) newspaper articles or news reports; or iii) literature that only elaborated on conceptual ideas or secondary research. Electronic searches were conducted in the following databases during September and October 2022: ProQuest, EBSCO, and Scopus, with Google Scholar also being searched to uncover relevant gray literature. Publication date limiters were set on all databases. The search terms used, including Boolean combinations and truncations, are shown in .

Table 1. Database search terms.

Study selection

Once the search was completed, all identified sources from selected databases were collated into EndNote 20. A total of 1,765 sources were retrieved from the ProQuest (n = 920), EBSCO (n = 461), Scopus (n = 269), and Google Scholar (n = 115) database platforms. After duplicates were removed, 1,429 articles remained. These articles were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following the review of article title and abstracts, the full text of 69 articles were reviewed against the eligibility criteria. Articles were excluded if they: i) focussed solely on the experiences of children under 12 years or adults over 25 years; ii) did not address accessibility of mental health services specifically for young people, adolescents, or young adults; and iii) only discussed the accessibility of mental health services in metropolitan contexts. A further eight articles were included in the final selection after forward citation chaining was conducted in Google Scholar. Only one researcher – the author – was involved in each stage of the screening process.

Charting the data

A data charting table was used to extract and analyze the data for each of the 22 sources (see ). This chart includes details about the aims and methods used in each source. Specific information included related to the scoping review focus, namely whether the article focussed on the perspectives of young people or service providers and the professional disciplines of authors for each article. The data chart was amended throughout the research process to include additional information that was seen as relevant to the aims of the review. Thematic analysis was used to categorize quantitative and qualitative findings from the selected literature into key themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). To assist with coding the data into key themes, a qualitative thematic analysis approach was used to interpret the data (Levac et al., Citation2010). The author identified only themes directly related to the research question. Seven initial themes were identified after reviewing the literature and the data was charted in a Microsoft Word table. These themes were further categorized into three key findings: i) youth-friendly services which provide support in a timely manner; ii) stigmatization of mental health issues among youth; and iii) collaboration with local communities and services.

Table 2. Characteristics of studies included in the findings.

Findings

Overall, 22 sources were included in the review, with most articles being published in 2020 (n = 9) and 2019 (n = 5). Except for a master’s thesis all studies were published in peer-reviewed journals. There was a similar number of sources that explored the perspectives of young people (n = 8) or service providers (n = 9). In addition, five studies examined both the perspectives of young people and service providers. Twelve studies originated from Australia, with the remaining ten studies originating from Canada. Just one study focused on the social work perspective in improving service access for young people in rural areas, whilst most articles were written from a mix of either psychologists (n = 13) or nurses (n = 9).

Two key themes emerged from analyzing the perspectives of young people in the selected studies: (i) the need to have nearby and youth-friendly mental health services to promote accessibility; and (ii) the impact peer stigmatization of mental illness has in stopping young people accessing services. The main theme uncovered from examining the perspectives of service providers was (iii) the ability to collaborate with local services and communities to advance service access.

Nearby, timely, and youth-friendly mental health services

A significant theme highlighted in the literature by young people was that mental health services, which provide support in a timely manner, are youth-friendly, and are located nearby enhance service accessibility. Frequently young people identified that either the convenient location of mental health services or service utilization of outreach programs were key to them being able to access services (Clark et al., Citation2018a; Dolan et al., Citation2020; Loughhead et al., Citation2018; Naughton et al., Citation2018). Specifically, regional Australian adolescent males identified how the presence of school counselors in high schools were key to motivating them to seek help for their mental health issues (Clark et al., Citation2018a). Other young people identified that having mental health clinics in nearby regional towns made traveling to appointments very easy (Dolan et al., Citation2020). Young people also reported being seen more quickly at services that were able to increase the number of appointments they could offer per week (Naughton et al., Citation2018). Other young people who were unable to attend services in-person thought that having clinicians come to their home had led to better service engagement (Loughhead et al., Citation2018).

The delivery of digital mental health programs such as SPARX and NewAccess in youth-friendly spaces was seen by many young people to be an effective access strategy (Fox et al., Citation2020; Litwin et al., Citation2022). In one instance, Inuit adolescents in Nunavut reported that the location of digital mental health programs in easy-to-access venues, such as schools and community centers, was critical in supporting their involvement (Litwin et al., Citation2022). Similarly, Australian young people thought making the NewAccess therapy program available in some regional Headspace centers increased service accessibility (Fox et al., Citation2020). These young people described how the youth-friendly environment at Headspace meant “you sort of felt like you’re being helped through it by a friend … it felt more caring” (Fox et al., Citation2020: 198). Remote Inuit adolescents that trialed SPARX also expressed the need for the app to be available in other centers, such as schools, to minimize their need to regularly travel to mental health services (Litwin et al., Citation2022).

Young people frequently identified long wait times to see a mental health professional, as well as cost, to be the major barriers to them accessing mental health services (Church et al., Citation2020; Guy, Citation2021; Libon et al., Citation2022). In one qualitative survey, almost half (47%) of adolescents either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that long wait times was a significant barrier for them to access services (Church et al., Citation2020, p. 561). In addition, the high cost charged by some counseling services made it difficult to access support and often increased the young person’s level of psychological distress (Libon et al., Citation2022). Long service waitlists often deterred young people from accessing mental health services, with one young person describing how “it would be a huge wait like 400 days just to have an intake appointment” (Guy, Citation2021, p. 103). Another young person discussing their experience of being on a wait list for a service appointment stated:

I remembered I called up for a therapist from [service] and it took almost, I want to say 15 months it took. Like it was a long time. I remember I was 15 so I was just about turning 17 when I got an appointment. (Guy, Citation2021, p. 95)

The person – the people who I talk to, it’s hard for them to understand. If it was someone, for example, who was a second generation [immigrant] who I could talk to, that would probably be wonderful. (Mathias et al., Citation2021, P. 97)

Overall, many young people living in rural areas described having to travel out of town for mental health appointments, which was both expensive and time consuming (Mathias et al., Citation2021). Despite this, rural youth stated that services which provided after-hours or weekend appointments and offered trial counseling sessions were more accessible (Mathias et al., Citation2021).

The stigmatization of young people with a mental health issue

The stigmatization associated with having a mental illness and seeking support was repeatedly identified by young people living in regional and rural Australia as being a critical barrier to them, accessing mental health services (Bowman et al., Citation2020; Clark et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Loughhead et al., Citation2018; Povey et al., Citation2020). Adolescents reported being concerned about being bullied if their male peers knew they were seeking support for their mental health (Clark et al., Citation2018b). These concerns also translated to the school environment, where adolescents reported feeling humiliated when the school counselor came into a class and asked a student to leave for counseling sessions (Clark et al., Citation2018a). Many young people also spoke about feeling as if a culture of stigmatization existed within Australian society in general:

I guess the sort of fear of being judged, the negative associations that come from having a mental illness or mental health issues, or if you go and see someone, is often portrayed by friends, media, lots of different places as a very negative thing. (Loughhead et al., Citation2018: 40)

Significantly, only two Australian studies explored the experiences of young people from Aboriginal and culturally diverse communities in accessing mental health services. LGBTQIA+ and Aboriginal youth in rural, regional, and remote areas of Australia stated they worried about reaching out to mental health services from fear of stigmatization (Bowman et al., Citation2020; Povey et al., Citation2020). Aboriginal adolescents expressed fear that someone might get angry or “mad” at them for seeking help, leaving them emotionally vulnerable (Povey et al., Citation2020, p. 9). LGBTQIA+ young adults also expressed fear about reaching out to mental health supports in their local towns (Bowman et al., Citation2020). They felt that mental health professionals needed to actively promote their services as safe spaces for LGBTQIA+ people to break the culture of stigma for LGBTQIA+ young people accessing mental health services (Bowman et al., Citation2020).

Collaborating with local services and communities

In contrast to the perspectives of young people, the 14 studies which reported the experiences of service providers had a different focus as they identified interagency collaboration and the involvement of local community stakeholders as two key approaches to improving mental health support for young people. For example, one Australian study found that mental health service providers in regional Gippsland delivered mental health support for young people more quickly when they collaborated with other youth-focussed agencies in the area (Dolan et al., Citation2020). Professionals working in pediatrics, education and youth mental health services reported that frequent collaborative meetings had improved how young people and their families accessed local youth mental health services (Chandradasa & Basu, Citation2020). Both studies reported that agencies had a better understanding of eligibility criteria and referral pathways for young people through interagency collaboration (Chandradasa & Basu, Citation2020; Dolan et al., Citation2020). Another effective approach to increasing service access for young people was an outreach youth mental health service in a small rural town in Tasmania, Australia, which was developed by two agencies (Bridgman et al., Citation2019). The outreach service improved service engagement, as service providers traveled to meet young people in their local rural communities instead of requiring young people to come into the service located out-of-town (Bridgman et al., Citation2019).

In contrast, service providers in rural Canada described how they established partnerships with local young adult services to ensure the mental health care of young people turning 18 can be smoothly handed over to adult services (Dubé et al., Citation2019; Reaume-Zimmer et al., Citation2019). In another rural area where there were no local adult mental health services, the adolescent mental health service ensured continuity of services by networking with out-of-area specialized services and hospitals (Etter et al., Citation2019).

Surprisingly, only one study identified the importance of collaborating with Indigenous communities to deliver counseling support for First Nations youth in rural Canada (Hensel et al., Citation2019). Service providers discussed how the Rural Northern Telehealth Service is one service that better engages with First Nations young people through partnership with Indigenous stakeholders in rural Canada (Hensel et al., Citation2019). Mental health professionals working at the service often travel to rural and remote communities to engage with Indigenous community members and young people receiving care (Hensel et al., Citation2019). This model of practice has allowed the service to engage with hundreds of First Nations young people (Hensel et al., Citation2019).

However, service providers in both Canada (Katapally, Citation2020; Litwin et al., Citation2022) and Australia (Povey et al., Citation2020) have implemented digital mental health platforms to support First Nations youth. In Canada, service providers collaborated with school principals in rural and remote Saskatchewan to design and implement the digital health platform titled Smart Indigenous Youth (Katapally, Citation2020). The collaborative design of the platform resulted in it being embedded in the school curricula and easily accessible for First Nations adolescents attending local schools across rural and remote Canada (Katapally, Citation2020). Similarly, the provision of the digital health program SPARX in Nunavut has increased the uptick of Inuit adolescents seeking mental health support (Litwin et al., Citation2022). Mental health service providers in rural, regional, and remote areas of the Northern Territory, Australia, have also engaged young Aboriginal people in help-seeking support through provision of the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for Youth (AIMhi-Y) App (Povey et al., Citation2020). Equivalent digital health platforms, such as Innowell, have been trialed among youth mental health services for all young people in regional Australia to great effect (Davenport et al., Citation2020; Fox et al., Citation2020; Rowe et al., Citation2020).

Notably, only one study explored the importance of health providers working closely with LGBTQIA+ youth communities in rural Australia to deliver web-based mental health interventions (Bowman et al., Citation2020). Service providers recognized that the delivery of web-based mental health interventions facilitated LGBTQIA+ young people receiving support to form peer-based mental health support groups with one another (Bowman et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

This scoping review reports on evidence from 22 studies about what enables or hinders access to mental health services for young people in rural, regional, and remote regions of Australia and Canada. These findings highlight the importance of social work practitioners, researchers, and policymakers advocating for equitable youth mental health services by listening and learning from the perspectives of young people and service providers in rural, regional, and remote areas.

Young people in rural areas believe mental health services need to improve accessibility by reducing the time spent on a waitlist for an initial appointment (Church et al., Citation2020; Guy, Citation2021). Despite this need, youth mental health services in rural and remote regions are often plagued by limited clinical service capacity and high volumes of referrals, resulting in long waitlists before young people are seen for an initial appointment (Guy, Citation2021; National Rural Health Alliance, Citation2021). Factors such as spatial isolation and the macro healthcare systems which are predominately structured for metropolitan areas has resulted in young people in rural and remote regions having unequal access to healthcare (Bourke et al., Citation2012; Wakerman et al., Citation2008). This inequality is particularly evident in small rural and remote Australian towns, as the pro-rata allocation of employed health care professionals is considerably less than elsewhere in the country (AIHW, Citation2023). By understanding these factors, policymakers can address specific inequities in health care service provision to rural and remote communities (Russell et al., Citation2013). Thus, it is critical that policymakers consider how issues of healthcare system structures in rural and remote communities are managed to improve youth mental health service accessibility.

Although a major finding of this review is that young people in rural and regional areas of Australia (Bowman et al., Citation2020; Clark et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Loughhead et al., Citation2018; Povey et al., Citation2020) and Canada (Church et al., Citation2020; Guy, Citation2021; Mathias et al., Citation2021) felt that the stigmatization of seeking support for mental health concerns severely impacted whether they accessed mental health services, this issue was not recognized in any of the 14 studies which examined the perspectives of service providers. This highlights an important practice gap which could be addressed by social workers in regional and rural areas, given their expertise in building community resilience and empowerment in rural areas (Alston et al., Citation2016). Rural social workers could support the development of community programs that address the stigmatization of mental illness among rural young people.

Another significant finding from the Canadian studies is the importance service providers in rural, regional, and remote regions placed on having strong connections between mental health providers, local community leaders, and generalist community agencies (Hensel et al., Citation2019; Katapally, Citation2020). This was critically important when working with First Nation communities (Hensel et al., Citation2019). The engagement that mental health service providers have with other community leaders and non-mental health agencies in facilitating mental health service accessibility for young people is a key area for social work clinical practice in rural, regional, and remote locations. A strength of social workers is their ability to work with rural communities to establish partnerships and collaborate with other agencies and community leaders (Howard et al., Citation2016). This means social work practitioners in rural, regional, and remote areas have great potential to facilitate fairer access to mental health services for First Nations young people in their communities (Maidment, Citation2020). It is essential that both social workers and service providers learn from and collaborate with First Nation community leaders and educators to improve mental health service engagement.

However, despite some limited evidence, predominately from Canada, which outlines factors which enable First Nation young people to access mental health services in rural, regional, and remote areas (Hensel et al., Citation2019; Katapally, Citation2020; Litwin et al., Citation2022), only one Australian study focussed on the experiences of Aboriginal young people accessing mental health support (Povey et al., Citation2020). Rather, most contemporary Australian studies examine how mental health services can better enable service access for First Nations young people living in metropolitan areas (Sabbioni et al., Citation2018; Wright et al., Citation2019). This points to a knowledge gap in understanding how social workers can promote equal opportunity to access mental health services for Aboriginal youth living in rural and regional areas. Similarly, there is extremely limited understanding in both the Australian and Canadian literature about how LGBTQIA+ young people in these regions have equal access to mental health services. It is critical to address these gaps given that both LGBTQIA+ and Aboriginal young people in Australia are two-and-a-half times more likely to experience mental illness and have a mental health diagnosis (AIHW, Citation2018; LGBTIQ+ Health Australia, Citation2021). while Canadian LGBTQIA+ youth are over three times at risk of suicide compared to their heterosexual peers (Liu et al., Citation2023).

While the findings of this study identify key issues that social work must address to enable fair access of youth mental health services in rural, regional, and remote areas, the limited focus of social work research also needs to be addressed, particularly given that demand for social workers is increasing in rural, regional, and remote areas (Doxey & McNamara, Citation2015). Although most literature co-authored by social workers with other health disciplines analyzed tools and service models of care for improving mental health service accessibility for young people (Bridgman et al., Citation2019; Dubé et al., Citation2019; Hensel et al., Citation2019; Naughton et al., Citation2018), the one article authored by three social workers in Canada limited their focus on just the barriers to service accessibility for young people (Church et al., Citation2020). Social work can position itself to promote equitable access to youth mental health services. A priority for future social work research should be to understand the practices that improve access to mental health services and supports for young people in rural, regional, and remote areas.

Limitations

This scoping review has some limitations. First, the review framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) was not implemented in its entirety, as time limitations meant that it was not possible to consult with mental health services and young service users. In addition, the validity and rigorousness of studies selected for synthesis was not critically examined (see Munn et al., Citation2018). There may also be a risk of bias in the research, as the scoping review source selection process was carried out by one person. The use of an inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed to reduce any personal bias associated with source selection.

Conclusion

Young people living in rural, regional, and remote communities of Australia and Canada have a higher likelihood of developing significant mental health concerns and illnesses. However, rural and remote youth have less opportunities to seek or receive mental health care. Notwithstanding, there is little social work research that explores how social work can promote mental health service accessibility for young people. Additionally, there was a notable lack of evidence outlining how social work practitioners can reduce mental health peer stigmatization. Findings from this review suggest that local collaborations between mental health services and community leaders is needed to address mental health stigmatization between young peers. This data highlights the critical need for rural and regional social workers to consider how peer stigmatization of mental health must be addressed to enable equitable access to youth mental health services by partnering with key community leaders and services.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Alison Wannan for her valued feedback and input on the drafting and revision of this article. This research was undertaken at the University of New South Wales, which the author is an alumnus of.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alston, M., Whittenbury, K., & Westerm, D. (2016). Rural community sustainability and social work practice. In J. McKinnon & M. Alston (Eds.), Ecological social work towards sustainability (pp. 94–108). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. (2021, May 11). Historic $2.3 billion National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan. https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/historic-23-billion-national-mental-health-and-suicide-prevention-plan

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018, November 29). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescent and youth mental health and wellbeing 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/atsi-adolescent-youth-health-wellbeing-2018/contents/summary

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021, June 25). Australia’s youth: Mental illness. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/mental-illness

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023, September 11). Rural and remote health. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health#access

- Barry, R., Rehm, J., de Oliveira, C., Gozdyra, P., & Kurdyak, P. (2020). Rurality and risk of suicide attempts and death by suicide among people living in four English-speaking high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(7), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720902655

- Beckwith, D., Briggs, L., Shapiro, M., & Carrasco, A. (2021). Engaging young people in early psychosis services – a challenge for social work. Social Work in Mental Health, 19(2), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2021.1884636

- Bland, R., Drake, G., & Drayton, J. (2021). Social work practice in mental health. Routledge.

- Bourke, L., Humphreys, J. S., Wakerman, J., & Taylor, J. (2012). Understanding rural and remote health: A framework for analysis in Australia. Health & Place, 18(3), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.02.009

- Bowman, S., Brona Nic Giolla, E., & Fox, R. (2020). Virtually caring: A qualitative study of internet-based mental health services for LGBT young adults in rural Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 20(1), 5443. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5448

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- Bridgman, H., Ashby, M., Sargent, C., Marsh, P., & Barnett, T. (2019). Implementing an outreach headspace mental health service to increase access for disadvantaged and rural youth in Southern Tasmania. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 27(5), 444–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12550

- Canadian Paediatric Society. (2023, May 4). Child and youth mental health. https://cps.ca/en/strategic-priorities/child-and-youth-mental-health

- Chandradasa, M., & Basu, S. (2020). Collaborative networking between regional child mental health, paediatric and educational services in Gippsland, Australia: An online survey. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 27(6), 571–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12552

- Church, M., Ellenbogen, S., & Hudson, A. (2020). Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services for rural and small city Cape Breton youth. Social Work in Mental Health, 18(5), 554–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2020.1801553

- Clark, L. H., Hudson, L., Dunstan, D. A., & Clark, G. I. (2018a). Barriers and facilitating factors to help-seeking for symptoms of clinical anxiety in adolescent males. Australian Journal of Psychology, 70(3), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12191

- Clark, L. H., Hudson, L., Dunstan, D. A., & Clark, G. I. (2018b). Capturing the attitudes of adolescent males’ towards computerised mental health help-seeking. Australian Psychologist, 53(5), 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12341

- Coulshed, V., & Orme, J. (2018). Social work practice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Davenport, T. A., Cheng, V. W. S., Iorfino, F., Hamilton, B., Castaldi, E., Burton, A., Scott, E. M., & Hickie, I. B. (2020). Flip the clinic: A digital health approach to youth mental health service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. JMIR Mental Health, 7(12), e24578. https://doi.org/10.2196/24578

- Davis, T. S. (2013). Wraparound in rural child and youth mental health: Coalescing family-community capacities. In T. L. Scales, C. L. Streeter & H. S. Cooper (Eds.), Rural social work: Building and sustaining community capacity (pp. 145–161). Wiley.

- Dolan, E., Allott, K., Proposch, A., Hamilton, M., & Killackey, E. (2020). Youth access clinics in Gippsland: Barriers and enablers to service accessibility in rural settings. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(6), 734–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12949

- Doxey, G., & McNamara, P. (2015). A new role for social work in rural Australia: Addressing psycho-social needs of farming families identified through financial counselling. International Social Work, 58(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872812461046

- Dubé, A., Iancu, P., Tranchant, C. C., Doucet, D., Joachin, A., Malchow, J., Robichaud, S., Haché, M., Godin, I., Bourdon, L., Bourque, J., Iyer, S. N., Malla, A., & Beaton, A. M. (2019). Transforming child and youth mental health care: ACCESS open minds New Brunswick in the Rural Francophone region of the Acadian Peninsula. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(10), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12815

- Etter, M., Goose, A., Nossal, M., Chishom-Nelson, J., Heck, C., Joober, R., Boksa, P., Lal, S., Shah, J. L., Andersson, N., Iyer, S. N., & Malla, A. (2019). Improving youth mental wellness services in an indigenous context in Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories: ACCESS open minds project. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12816

- Fox, R., Nic Giolla Easpaig, B., Roberts, R., Greig, J., Burmeister, O., Dufty, J., & Thomas, S. (2020). Evaluating a low-intensity cognitive behavioural program for young people in regional Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 28(2), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12619

- Gartshore, S., Maple, M., & White, J. (2018). Developing partnerships between University and local service agencies: Exploring innovative social work placements in rural and remote NSW public schools. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 20(1), 65–79.

- Golightley, M., & Goemans, R. (2020). Social work and mental health. Sage.

- Government of Canada. (2023, May 24). Government of Canada announces research investment of over $680,000 to support the health and mental wellbeing of young children. https://www.canada.ca/en/institutes-health-research/news/2023/05/government-of-canada-announces-research-investment-of-over-680000-to-support-the-health-and-mental-wellbeing-of-young-children.html

- Gulliford, M. (2013). Equity and access to health care. In M. Gulliford & M. Morgan (Eds.), Access to health care (pp. 36–60). Routledge.

- Guy, M. (2021). The lived experience of youth mental health care on cape Breton Island [ Master’s thesis]. Dalahousie University]. DalSpace Library Repository. https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/80669/MaeridithGuy2021.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- Hensel, J. M., Ellard, K., Koltek, M., Wilson, G., & Sareen, J. (2019). Digital health solutions for indigenous mental well-being. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(8), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1056-6

- Hen, M., Shennar-Golan, V., & Yatzker, U. (2022). Children and adolescents’ mental health following COVID-19: The possible role of difficulty in emotional regulation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 865435. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.865435

- Howard, A., Katrak, M., Blakemore, T., & Pallas, P. (2016). Rural, regional and remote social work: Practice Research from Australia. Routledge.

- Ivancic, L., Cairns, K., Shuttleworth, L., Welland, L., Fildes, J., & Nicholas, M. (2018, June 28). Lifting the weight: Understanding young people’s mental health and service needs in regional and remote Australia. ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2018-06/apo-nid180271.pdf

- Katapally, T. R. (2020). Smart indigenous youth: The smart platform policy solution for systems integration to address indigenous youth mental health. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 3(2), e21155. https://doi.org/10.2196/21155

- Kauhanen, L., Yunus, W. M. A. W. M., Lempinen, L., Peltonen, K., Gyllenberg, D., Mishina, K., Gilbert, S., Bastola, K., Brown, J. S. L., & Sourander, A. (2022). A systematic review of the mental health changes of young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(6), 995–1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02060-0

- Khanassov, V., Pluye, P., Descoteaux, S., Haggerty, J. L., Russell, G., Gunn, J., & Levesque, J.-F. (2016). Organizational interventions improving access to community-based primary health care for vulnerable populations: A scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(168), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0459-9

- Levac, D., Coloquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(18), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- LGBTIQ+ Health Australia. (2021, October). Snapshot of mental health and suicide prevention statistics for LGBTIQ+ people. https://assets.nationbuilder.com/lgbtihealth/pages/549/attachments/original/1648014801/24.10.21_Snapshot_of_MHSP_Statistics_for_LGBTIQ__People_-_Revised.pdf?1648014801

- Libon, J., Alganion, J., & Hilario, C. (2022). Youth perspectives on barriers and opportunities for the development of a peer support model to promote mental health and prevent suicide. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 45(3), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/01939459221115695

- Litwin, L., Hankey, J., Lucassen, M., Shepherd, M., Singoorie, C., & Bohr, Y. (2022). Reflections on SPARX, a self-administered e-intervention for depression, for Inuit youth in Nunavut. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 47(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000218

- Liu, L., Batoman, B., Pollock, N. J., Contreras, C., Jackson, B., Pan, S., & Thompson, W. (2023). Suicidality and protective factors among sexual and gender minority youth and adults in Canada: A cross-sectional, population-based study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1469. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16285-4

- Loughhead, M., Guy, S., Furber, G., & Segal, L. (2018). Consumer views on youth friendly mental health service in South Australia. Advances in Mental Health, 16(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2017.1360748

- Maidment, J. (2020). Social work in rural Australia: Enabling practice. Routledge.

- Maple, M., Pearce, T., Gartshore, S., MacFarlane, F., & Wayland, S. (2018). Social work in rural New South Wales school settings: Addressing inequalities beyond the school gate. Australian Social Work, 72(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1557229

- Mathias, H., Jackson, L., Hughes, J., & Asbridge, M. (2021). Access to mental health supports and services: Perspectives of young women living in Rural Nova Scotia (Canada). Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 40(2), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2021-013

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromartaris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- National Rural Health Alliance. (2021, July). Mental health in rural and remote Australia. https://www.ruralhealth.org.au/sites/default/files/publications/nrha-mental-health-factsheet-july2021.pdf

- Naughton, J. N., Carroll, M., Basu, S., & Maybery, D. (2018). Clinical change after the implementation of the choice and partnership approach within an Australian child and adolescent mental health service. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12208

- Novik, N., McKee, B., & Pearce, K. (2022). Social work practice and mental health services outside of urban settings. In B. Jeffrey & N. Novik (Eds.), Rural and northern social work practice: Canadian Perspectives (pp. 154–171). University of Regina.

- Penchansky, R., & Thomas, W. (1981). The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care, 19(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001

- Peters, I., Handley, T., Oakley, K., Lutkin, S., & Perkins, D. (2019). Social determinants of psychological wellness for children and adolescents in rural NSW. BMC Public Health, 19(1616), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7961-0

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H., Garrity, C. M., Hempel, S., Horsley, T., Langlois, E. V., Lillie, E., O’Brien, K. K., Tunçalp, Ӧ., Wilson, M. G., Zarin, W., & Tricco, A. C. (2021). Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews, 10(263), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

- Povey, J., Sweet, M., Nagel, T., Mills, P. P. J. R., Stassi, C. P., Puruntatameri, A. M. A., Lowell, A., Shand, F., & Dingwall, K. (2020). Drafting the aboriginal and islander mental health initiative for youth (AIMhi-Y) App: Results of a formative mixed methods study. Internet Interventions, 21, 100318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100318

- Reaume-Zimmer, P., Chandrasena, R., Malla, A., Joober, R., Boksa, P., Shah, J. L., Iyer, S. N., & Lal, S. (2019). Transforming youth mental health care in a semi-urban and rural region of Canada: A service description of ACCESS open minds Chatham-kent. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12818

- Rowe, S. C., Davenport, T. A., Easton, M. A., Jackson, T. A., Melsness, J., Ottavio, A., Sinclair, J., & Hickie, I. B. (2020). Co-designing the InnoWell platform to deliver the right mental health care first time to regional youth. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 28(2), 190–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12617

- Russell, D. J., Humphreys, J. S., Ward, B., Chisholm, M., Buykx, P., McGrail, M., & Wakerman, J. (2013). Helping policy-makers address rural health access problems. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 21(2), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12023

- Sabbioni, D., Feehan, S., Nicholls, C., Soong, W., Rigoli, D., Follett, D., Carastathis, G., Gomes, A., Griffiths, J., Curtis, K., Smith, W., & Waters, F. (2018). Providing culturally informed mental health services to Aboriginal youth: The YouthLink model in Western Australia. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(5), 987–994. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12563

- Smith, C. (2022, December 15). Mental health social work enabling better access. Australian Association of Social Workers. https://www.aasw.asn.au/aasw-news/2022-2/mental-health-social-work-enabling-better-access/

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C. … Lewin, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Wakerman, J., Humphreys, J. S., Wells, R., Kuipers, P., Entwistle, P., & Jones, J. (2008). Primary health care delivery models in rural and remote Australia – A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 8(276), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-276

- Ward, D. J. (2015). The long sleep-over: The lived experience of teenagers, parents and staff in an adolescent psychiatric unit [ Doctoral dissertation]. The University of Queensland. UQ eSpace Repository. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/data/UQ_356717/s3327153_final_thesis.pdf?Expires=1693997327&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJKNBJ4MJBJNC6NLQ&Signature=hc1L-ODh5D~sF8U42SxSgMiNRL7Tg8ANWcIOwW6RwNvQlyJlnrA8MDEV1Q0GHeiqdrx48iN7Wa8JIHMt8y1yh0nqKqAZi7FNkE5U38keCfnlsGPa-PHsJSxFjnI1io0HksEqa2369MSIBse1ALtdT7dRBr4NF87QLM3lBs30OMX3FhmgoaBkCDrWCeH7rDCad42uwfN5gQW3uz5vEWXUY2dsoWaVNOZGKUHZNTCnGY1I2tp8KmEf-I5YTb8jLnW-K0ghiQs64eOMacc6KRFUkBpZ8sRq78WUsT7Jb8Q67pnTJRweuTnzl1awoA3OrJ10QR1xdYwdMpf671jzZDbh-g__

- World Health Organization. (2021, November 17). Mental health of adolescents. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

- Wright, M., Culbong, T., Crisp, N., Biedermann, B., & Lin, A. (2019). “If you don’t speak from the heart, the young mob aren’t going to listen at all”: An invitation for youth mental health services to engage in new ways of working. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(5), 987–994. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12844