ABSTRACT

The article elaborates the theory of hypermediation to describe actions related to digital religion that involve various media platforms. According to this theory, media simultaneously hold material, institutional, and technological characteristics. Furthermore, hypermediation entails the creation of affective spaces between physical and digital actions. The theory of hypermediation draws upon literature on religion and media and is applied to case studies of anti-gender movements: Christian-inspired groups that oppose same-sex unions and promote traditional family values. The group Sentinelle in Piedi employs the Internet to organize silent protests at which people read books as an implicit criticism of media institutions and technologies. La Manif Pour Tous stages performances in physical settings to provoke emotional reactions, then it enhances their impact through online circulation. The article uses these examples to show how the concept of hypermediation can be a starting point to analyze the multimedia character of contemporary religion across material actions and digital spaces.

The contemporary proliferation of Internet technologies and digital media practices generates new opportunities for media use. The distinction between media producers and consumers is becoming blurred, and political participation and activism develop a “hybrid” nature due to the emergence of new media logics and the complex power balance between media actors (Chadwick, Citation2013; Treré, Citation2019). As a result, scholars are increasingly faced with the challenge of finding frameworks to account for blurred media boundaries, interconnected platforms, and intensified participation.

This increasing complexity of the contemporary media landscape also results in changes within religious beliefs and practices. The proliferation of mediated religious narratives shows that religion is increasingly visible in media venues (Herbert, Citation2011), and the lockdowns enacted to stop the spreading of COVID-19 forced several religious groups and individuals to turn to online options (Huygens, Citation2021; Sabaté Gauxachs et al., Citation2021). This has led to calls for religion and media scholarship to focus on the interplay between online and offline venues, and to consider the hybrid intertwining of religion, politics, gender, race, and culture (Lövheim & Campbell, Citation2017). For instance, scholars increasingly look at multiple platforms to capture contemporary religious discourses and their intersections with politics and society, instead of analyzing a single website or medium (see, for instance, Bhatia, Citation2021; Leidig, Citation2021). However, there is still a lack of systematized approaches that account for practices, narratives and identities that exist across platforms and employ various communication strategies. Furthermore, digital religion often exists outside institutional organizations: as Peterson (Citation2019) notes, “research must address the complex, interconnected and messy aspects of the digital moment, in which individuals make meaning in ways that may or may not connect to traditional religious institutions” (p. 8). Following this call, the purpose of the article is to propose the concept of hypermediation as a potential line of inquiry to capture the transformations of media technology and religious groups in contemporary society.

The theoretical framework of hypermediation described in this article is inspired by the work of Scolari (Citation2015) and that of the scholars of the Center for Media, Religion and Culture (Echchaibi, Citation2017; Evolvi, Citation2018) as a model for understanding certain digital actions that exist between the Internet and physical venues. The notion of digital religion, on which this article builds, posits that religion in the Internet age exists in spaces simultaneously linked to online and offline environments (Campbell & Evolvi, Citation2019; Campbell & Tsuria, Citation2021). By taking into account the material, institutional, and technological features of media, the theory of hypermediation constitutes an innovative way to approach digital religion, especially because it offers a framework to explore religious groups existing outside of traditional religious institutions, and that heavily rely on Internet communication. This article is to be considered as a preliminary work that proposes a new theoretical and methodological approach to look at digital religion. In particular, I would argue that hypermediation can be a call for scholars to assume an interdisciplinary look at the interplay of different media forms, and to stress the importance of space and emotions in the study of contemporary religion.

In the first section of this article, I will present the theory of hypermediation by grounding it in media theory with a review of the relevant literature. I will then draw upon previous scholarship on religion and media, focusing on the concepts of mediation, mediatization, and the social shaping of technology to contextualize hypermediation in relation to the intertwining of different media forms. I will also address the creation of emotional spaces of practice, drawing from the notion of third spaces (Hoover & Echchaibi, Citation2014). In the second part of the article, I will illustrate the theory with an empirical case study of anti-gender movements in Europe. These groups, which criticize same-sex unions and organize pro-family and pro-life events, are inspired by traditional Christian values and hold an anti-elitist attitude to the media and political system. Anti-gender groups exemplify how hypermediation works because they engage in digital activism employing both physical spaces and digital media platforms to circulate highly emotional narratives. I will specifically present one group – Sentinelle in Piedi (Standing Watchmen) – and its activities to illustrate how hypermediation involves material, institutional, and technological characteristics. In addition, I will discuss the case of the group La Manif Pour Tous (Demo for All) to show how visual material can be rapidly circulated through Internet spaces and provoke emotional reactions. In conclusion, the article explains how the theory of hypermediation might be a useful starting point for scholars who study religious groups that share three characteristics: the use of multiple media platforms, an emphasis on material practices in relation to the Internet, and a negotiation of media use depending on their values.

Defining Hypermediation

The term “hypermediation” includes the Greek prefix -hyper (ὑπέρ), which means “above” or “beyond,” but it also indicates something that is “excessive” or “exaggerated.” The concept of hypermediation has been used in various fields to indicate the connections between different media forms. In linguistics, for example, hypermedia (or “hypertext”) may refer to texts that feature typographic and non-typographic elements (Djonov, Citation2012). Therefore, the framework of hypermedia can indicate digital venues characterized by hyperlinks and interconnected webpages that embed text, pictures, images, and sound.

Hypermediation can also describe how the proliferation of media in contemporary society brings changes in patterns of media consumption. In this regard, Bolter and Grusin (Citation2000) offer an account of “hypermediacy” as something that includes multiple acts of representation in a given space. The authors describe hypermediacy as a media logic that is part of remediation: the process of reusing and conferring a new awareness upon older media forms. Remediation considers both the proliferation of media content and the increasing embeddedness (and invisibility) of media in society. In the process of remediation, “hypermediacy” indicates how media are made more visible through multiple acts of representations. Bolter and Grusin offer European cathedrals as an example of hypermediacy, for they respond to media fascination by displaying multiple media forms in a specific space, including stained glasses, sanctuaries, and inscriptions (34–35). However, the cathedral represents a space-limited example and does not capture the shifting character of digital media, where people can create complex and collective narratives that are potentially endless. It is for this reason that, I would argue, there is a need to re-think the concept of mediation in light of recent technological developments.

Following this line of reasoning, Scolari (Citation2015, p. 8) offers an alternative definition of hypermediation, understood in relation to Martin-Barbero’s (Citation1993) theory of mediation. Adapting the concept of mediation in contemporary settings, Scolari describes hypermediation as “the complex network of social production, exchange and consumption processes that take place in an environment characterized by a large number of social actors, media technologies and technological languages” (p. 2). Hypermediation thus explores new technologies as well as how people approach them, and not only the display of multiple media forms as in the aforementioned example of the cathedral. In relation specifically to digital religion, hypermediation has also been used by Echchaibi (Citation2017) as part of a reflection conducted by the Center for Media, Religion and Culture at the University of Colorado Boulder to indicate the speed, intensity, and ubiquity of contemporary media, as well as their impact on everyday life and religion. It is similar to the approach taken by Scolari in its emphasis on human and non-human actors and how they are linked, rather than being focused solely on technological changes.

Therefore, hypermediation indicates interconnections between texts, processes of remediation, people’s approaches to new media technologies, and the intensification of practices in the present media moment. The various perspectives on hypermediation all similarly conceptualize it as involving multiple media technologies and the complex intertwining of media practices in contemporary society. This also constitutes my starting point for elaborating a theory of hypermediation as applied to digital religion. However, I consider that hypermediation can benefit from greater attention to the interconnections among media that concur to create religious narratives. By drawing from literature in media and religion, the next section describes three aspects of media which I consider important to understand hypermediation: materiality, institutions, and technologies.

Media as Materiality, Institutions, Technologies

I conceptualize hypermediation as something that goes “beyond” traditional understandings of mediation and “beyond” a single media form, or a single definition of media. This follows the aforementioned work of Bolter and Grusin (Citation2000), who define hypermediation as part of the processes that negotiate and incorporate emerging media technologies in existing communication patterns. I would argue that, to capture the hybridity of the current media system, it is important to provide definitions of media forms that are involved in this multimodal intertwining.

The field of media and religion often regards media as material objects, institutions, and technologies. These perspectives exist in relation to some predominant theories in the field, which are mediation, mediatization, and the social shaping of technology (Campbell, Citation2010). However, I would argue that it can be limiting to adopt theories that focus on a single aspect of media, because the contemporary digital media landscape often relies on communications across media platforms. Hence, these theories have already been combined to create innovative approaches for the study of digital religion: for instance, Hutchings (Citation2017) draws from these frameworks to construct the Mediatized Religious Design approach for the study of online churches. Differently from Hutchings’ work, my focus is on the interplay between platforms rather than online practices, but I similarly draw upon the theories of mediation, mediatization, and social shaping of technology to offer three definitions of media that are not mutually exclusive and aim to offer scholars additional tools to explore digital religion.

The concept of media as material objects can be connected to the theory of mediation, which posits that media are artifacts for communication that produce cultural effects. Martin-Barbero’s (Citation1993) theory of mediation, upon which Scolari (Citation2015) builds the concept of hypermediation, regards media as assuming meaning in relation to the context in which they are created and employed, and as being conditioned by how people use them to articulate and spread narratives. In this respect, Meyer (Citation2011) asserts that mediation activates media as material objects – or “sensational forms” – that help people to experience religion. Meyer’s work calls for a broad and material-based definition of media which includes all those objects – such as books, statues, and bodies – that may serve to aid communication and the construction of meaning, and that are especially relevant in religious practices.

Mediations may assume a focus on institutions when discussed in relation to the theory of mediatization. The proliferation of new media technologies leads to long-term structural transformations in terms of the role of media in society. As a result, media logics increasingly condition cultural and social institutions. Hjarvard (Citation2014) places emphasis on the institutional characteristics of media. In a similar manner to other social institutions – such as family, education, and religion – media develop within existing social structures and function as independent institutions with their own sets of rules. The theory of mediatization posits that media also hold the power to influence other institutions because they impose a set of rules – or “media logics” – on representations of cultural and social meanings (Couldry & Hepp, Citation2013). For instance, in societies where there is a high level of media use, religious groups are increasingly employing media to spread their messages, and people’s knowledge of religion is becoming dependent on media representations, including news reporting and popular culture (Hjarvard & Lovheim, Citation2012). From this perspective, media are not solely objects, but also powerful institutions that condition the existence of other social spheres.

Media might also be regarded as technologies, especially when viewed from the perspective of the theory of social shaping of technology (SST). Discussing social and cultural negotiations of media, SST sees technological change as a social process, and defines technology as involving both the designers and users of technological artifacts (Williams & Edge, Citation1996). Media are thus considered to be technologies that serve specific social purposes and are shaped by people’s uses. This also includes the rejection of media technology, as happens in the case of Amish communities that refrain from using the telephone for cultural and religious reasons (Zimmerman-Umble, Citation1992). In this respect, Campbell (Citation2010) coins the term religious-social shaping of technology to explore how religious communities explore technological innovation. According to Campbell, the focus is not only on media objects, but on media as new technologies that religious communities negotiate through their core values, history, and traditions.

These three perspectives – mediation, mediatization, and SST – are not monolithic and each theory considers some form of interaction among materiality, institutions, and technologies, showing how it is possible to approach media from different viewpoints. As a result, communication processes do not just involve a single media platform or characteristic, but rather include media in their material form, in their institutional capacity, and in their technological aspects. Therefore, I would posit that the theory of hypermediation can help scholars capture this fluid and hybrid character of present-day media if it is considered a framework that accounts for these various aspects of media. Below I will use the theory of hypermediation to explain how the anti-gender group Sentinelle in Piedi employs physical performances and the material act of reading books to influence institutional representations, and it does so through the use (as well as rejection) of digital technologies. However, present-day communications are not only characterized by various media aspects, but also by an intensification of affective narratives and reactions: the next section explains how physical and digital spaces are often characterized by the rapid circulation of emotion.

Media as Emotional Spaces

The interconnections between material, institutional, and technological media forms have implications in terms of space, and spaces have a role in creating certain types of narratives. Therefore, this section explains why it is important to consider hypermediation as potentially capturing the creation of spaces, and the emotional characteristics of these spaces. In particular, space and media intersect in two main ways. First, communication processes always involve physical spaces. The use of media never happens in a vacuum, but is rather embedded in locations that are transformed by their presence and by their material characteristics. For example, media can shape the space of domestic life (Hoover & Clark, Citation2003), influence the way activism occupies public spaces (Lievrouw, Citation2011), or give relevance to existing physical spaces by circulating pictures online (Della Ratta, Citation2018).

Second, the articulation of narratives within digital platforms can create discursive and performative spaces. These spaces are not necessarily based in a physical location, but they do provide people with the means to articulate communities and multiply the options for online consumption. For instance, Lövheim (Citation2011) studies young women’s blogs as “ethical spaces” because they function as platforms for discussing social and cultural values among given groups. Sumiala and Korpiola (Citation2017) address space with their claim that online images and narratives can be “respatialized” by crossing “religious, cultural, and political boundaries” (p. 62). From this perspective, digital platforms where narratives and images are circulated are able to create spatial dynamics whose social and cultural consequences are comparable to physical spaces.

In this respect, Hoover and Echchaibi (Citation2014) employ the concept of “third space” to describe digital religion. Borrowing from architecture, sociology, and postcolonial theory, and addressing the theory of mediation, Hoover and Echchaibi regard the term as describing the hybridity of practices that can be situated between online and offline venues. A third space is an online venue functioning “as if” it was a space of encounter and discussion for given groups, which exist on the Internet but confer new qualities to the religious and cultural experiences of their audience. Drawing from this perspective, it is valuable to consider hypermediation in terms of hypermediated spaces because media are connected to physical venues and create discursive spaces online, embedding the aforementioned material, institutional, and technological media aspects. In my theorization of hypermediation, I believe that these media spaces intensify consumption and communication rather than simply mimicking existing physical spaces. The prefix “hyper” connotes hypermediation as going “beyond” predefined categories of media and mediation, but also as possessing an “exaggerated” character.

The fast – and “exaggerated” – exchanges of hypermediated spaces may result in intense emotional interactions. The interconnected nature of various media platforms and the ability to quickly access a variety of information also create the conditions for people to affectively circulate and consume emotional narratives, which have been studied in relation to social media and their ability to form “affective publics,” as per the work of Papacharissi (Citation2014) on activism and digital storytelling. Social networks can thus be regarded as “affective spaces” characterized by the performance of affective labor (Peterson, Citation2016). With this idea in mind, Abdel-Fadil analyses a conservative Christian Facebook group and defines it as an affective space that enables the intensification of conflictual exchanges (Citation2019) . Drawing on Ahmed’s (Citation2014) work on the cultural politics of emotions, Abdel-Fadil describes online emotions as performative, relational, and directed toward a certain audience.

Hypermediation thus emphasizes the need for scholars to consider also the processes of space-creation on the Internet, and the emotional exchanges created through digital media. Hence, contemporary digital communications do not only involve material, institutional, and technological features of media to establish networked relations, but they also create spaces of discussion and community formation. To provide an example, I will discuss how anti-gender groups such as La Manif Pour Tous charge existing physical spaces with specific meanings through protests and performances. These actions result in pictures and narratives that are circulated online to affectively engage people, especially when they hold a strong emotional character. These two characteristics of hypermediation – space and emotions – permit this theoretical approach focusing on the qualitative and unprecedented changes in media use in contemporary society. The embedded nature of media forms and practices means that the framework of hypermediation also methodologically demands attention to multiple media platforms, something explored in the next section.

Exploring Hypermediation

Because hypermediated spaces exist across various media platforms, and involve material, institutional, and technological aspects, scholars must explore them by looking at interconnections between media narratives. Although this article is primarily based on online material, it pays attention to a variety of digital narratives and pictures that connect to physical venues. Taking a multimethod approach, I followed the websites of anti-gender groups, specifically the websites of Sentinelle in Piedi (www.sentinelleinpiedi.it) and La Manif Pour Tous (hereinafter LMPT, www.lamanifpourtous.fr) and their connected Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter pages. I also explored related pages such as Il Blog di Costanza Miriano (www. costanzamiriano.com), a blog written by Italian journalist Costanza Miriano, who is involved with these movements. Inspired by the principle of online ethnography (Postill & Pink, Citation2012), I read posts on these sites extensively from 2014 to 2018, while also taking comments into account and paying particular attention to visual narratives and pictures. I did not directly participate in discussions but observed how online interactions developed. In some cases, these posts no longer exist online, so I performed my analysis using an archive I created during my ethnographic research. In the process, I also collected newspaper articles and blog posts about these movements.

Moreover, I selected the posts that were informative about these groups’ use of media and discussed actions occurring in physical spaces, focusing in particular on performances. I performed a textual and visual discourse analysis (Wodak & Bush, Citation2004) by doing a close reading of the posts and finding relevant patterns connected to materiality, institutions, and technologies, as will be analyzed in the following section. As most of the texts are in Italian or French, I translated them for the purposes of this article. I then interviewed people involved in these movements. As I will explain in the next section, members of anti-gender groups (especially Sentinelle in Piedi) are often suspicious of journalists and scholars, and some refused to be formally interviewed. However, by interacting with people at a Sentinelle in Piedi event in Milan and by contacting members online, not only was I able to collect various viewpoints on these groups’ activities, but I also conducted three formal interviews with people who have leadership roles within both Sentinelle in Piedi and LMPT. In the next section, I look at how Sentinelle in Piedi and LMPT articulate anti-gender discourses through public protests and performances. The analysis shows how paying attention to all these aspects allows us to understand complex media phenomena and capture certain contemporary communication patterns.

Anti-Gender Christian Groups as Examples of Hypermediation

An analysis of the activities and social media use of anti-gender groups can provide a practical illustration of hypermediation, and shows how an attention to different media forms and to the creation of emotional spaces can capture some contemporary characteristics of digital religion. The term “anti-gender” refers to the ideology of groups that promote traditional family values and a conventional understanding of gender roles. More specifically, these groups criticize marriage equality, as well as adoptions and assisted reproduction for same-sex couples. Starting in 2012/13, anti-gender groups such as LMPT have been spreading in predominantly Catholic European countries as a response to LGBTQ+ activism (Paternotte, Citation2008) and to protest the decisions of some governments to allow same-sex unions (Kuhar & Paternotte, Citation2017). The notion of “anti-gender” refers to what has been dubbed “gender theory,” allegedly a left-wing ideology promoted by media, governments, and academia to erase gender differences. While these groups do not call themselves “anti-gender,” this is the term predominantly used in academia (Graff, Citation2016). Being highly mediated and disconnected from traditional religious institutions, these groups exemplify some aspects of digital religion and show the need for frameworks to account for the theoretical complexity of contemporary religion.

While anti-gender movements do not claim to be religious and welcome people from all faiths, the groups are connected with conservative Christianity (specifically Catholicism) by condemning everything that deviates from the perceived norm of the traditional, heterosexual Catholic family (Righetti, Citation2016). Even if not formally recognized by the Vatican or part of a religious institution, anti-gender groups came into being and became increasingly organized thanks also to the effort of organizations such as Opus Dei, a movement within the Catholic Church that wields strong political and social power and promotes constant spiritual engagement for the laity (Garbagnoli & Prearo, Citation2018).

Anti-gender movements are innovative in creating strategies to translate conservative Catholic ideologies into actions that subvert the status quo, such as large-scale public protests (Garbagnoli, Citation2014). These groups do not claim any political affiliation, but have often been studied as part of the wave of European right-wing populism (Kováts, Citation2018). According to Harsin (Citation2018), these political attitudes are paired with the circulation of anti-elitist and nostalgic narratives, which contributes to the spread of post-truth discourses on social networks. The author identifies various post-truth qualities of anti-gender Facebook pages, including the marginalization of certain social groups (specifically, homosexuals) as deviant, the promotion of distrust against media, the spreading of emotions and sensationalistic news, and connections with right-wing populism. As a result, the combination of conservative Catholic ideologies and right-wing political mobilization creates what can be defined as a “hybrid political space of Catholic collective action,” where religion becomes a political arena to influence society at large (Lavizzari & Prearo, Citation2018, p. 13).

Studying the proliferation of anti-gender groups is compelling because they approach politics, religion, and media unconventionally, and a framework such as that of hypermediation can help understand their unusual narrative and performative strategies (Evolvi, Citation2020). They represent a type of militant Catholicism that rails against secularism and tries to make traditional family values more visible. These groups also appeal to right-wing actors without being officially affiliated to political parties, and reject both the political establishment and national media in an anti-elitist effort, while creating transnational networks across European countries. The activist strategies of these groups can also vary significantly: while LMPT organizes demonstrations where people march and sing loudly, the groups Veilleurs Debout (Standing Watchmen) and Mère Veilleuses (Watching Mothers) started protesting by standing in silence. The technique of protesting by remaining totally silent and still also became popular in Italy among the group Sentinelle in Piedi (which is translated from the French and similarly means Standing Watchmen) as a strategy for attracting social attention.

This article focuses on anti-gender groups because they have an hypermediated character. Even if they are just an example of how religion exists in contemporary society, and cannot therefore be generalized to explain all cases of digital religion, they present some important characteristics of the present media moment. For instance, the organization of protests in squares and public places is coupled with an intense media strategy that mostly involves social media platforms, resulting from enhanced opportunities for communication. While these groups tend to have a controversial relationship with media institutions, they embed both material aspects and digital technologies in their protests. I will here use the example of Sentinelle in Piedi’s demonstrations to show how media criticism and endorsement can result in the material, institutional, and technological features of media becoming intertwined. Anti-gender movements also employ narratives, images, and performances that aim to achieve emotional reactions, charging physical venues and digital spaces with specific meanings. I will illustrate this characteristic with the example of how LMPT creates an affective attachment to its logo and circulates strong images to promote family values.

Sentinelle in Piedi: Materiality, Institutions, Technologies

Hypermediation describes how people use various media platforms and create interconnections among actors, translating actions and narratives between online and offline venues. Anti-gender groups exemplify this aspect of hypermediation because their mode of protest involves both participation in physical spaces and online communication. In addition, these groups often reflect on the characteristics of media and tend to criticize what they perceive as mainstream media, finding alternative modes of expression instead. This hypermediated characteristic of anti-gender groups is particularly visible in the protest technique adopted by Sentinelle in Piedi, a group that gained popularity in Italy between 2013 and 2016. The protests consist of demonstrations called veglie (watches), at which silent participants stand a meter from one another, reading a book of their choice. The group does not have formal membership, and people usually come to know of an upcoming veglia via the group’s website or announcements on social networking pages, especially Facebook and Twitter.

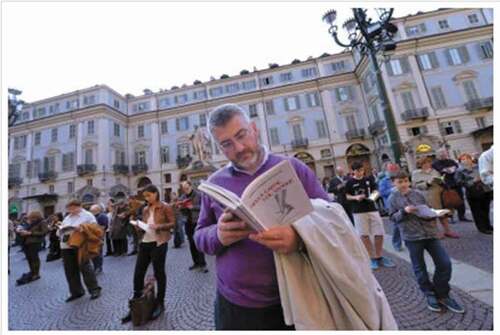

The materiality of Sentinelle in Piedi’s protests is expressed in the gesture of reading a book, a practice that the group’s website describes as being aimed at “deepening, studying, and gaining critical thinking about reality.” Silent book reading has three main symbolic values. First, the content of the book becomes a way to convey a message. While participants can choose their own books, they may read the Bible or works of contemporary Catholic authors. In some cases, they also read the Qur’an or sacred texts from other religions, probably to express their professed multi-faith beliefs. There are also instances of participants reading books of left-wing thinkers, such as Antonio Gramsci, in what seems to be an effort to associate anti-gender protests with subversive and anti-establishment ideologies. Second, reading is an implicit criticism of social media and modern technology, which allegedly prevent people from reflecting in-depth on social issues. Indeed, participants are encouraged to read paper books rather than using technological devices. Pictures of the veglie circulated by the official webpages of Sentinelle in Piedi and their members often give relevance to the books by portraying them in the foreground, as can be seen in . Third, reading a book can be a symbolic reminder of a spiritual exercise, enhanced by the silence of the square. As Righetti (Citation2016) writes about Sentinelle in Piedi, a book is an object “still enveloped by an aura of sacral respect” (p. 290). The sacred character of books, one may argue, is extended to the square when the act of reading is repeated by multiple participants, as in the case of a veglia (). Therefore, books are material objects that convey meanings because of their content, but in this case, they are used in visual performances that create messages about contemporary society and carry almost sacred meanings.

Figure 1. Retrieved from “Il Blog di Costanza Miriano,” March 31, 2014 https://costanzamiriano.com/2014/03/31/sentinelle-in-piedi/ (accessed October 6, 2019).

Figure 2. Retrieved from “Il Blog di Costanza Miriano,” January 21, 2016 https://costanzamiriano.com/2016/01/21/vegliamo-nella-vita-in-piedi-nelle-citta-a-roma-per-il-family-day/sentinelle-in-piedi-2/ (accessed November 5, 2019).

Sentinelle in Piedi’s protests also engage with media as institutions. The act of reading is a symbolic protest against the media system, often criticized on the group’s website and social media. Sentinelle in Piedi also chooses to protest in silence because its members believe that secular media promote gender theory, and so they refuse to release interviews with journalists. When I approached members online and in person, many gave me their informal opinion but did not want to be interviewed because of the suspicion harbored against media experts, media scholars, and academia. The group’s official blog also published the following statement on its home page:

We have gathered here all the information that will facilitate an understanding of why we do not accept invitations for TV appearances and interviews. We are certain that these few lines and the speech you might hear if you come to one square [protest] are enough to understand what we do. We also remind you that all our releases are published on the website’s blog (Sentinelle in Piedi, Citation2016)

This criticism reflects an anti-elitist attitude that generically targets mainstream secular media, defined as national newspapers, television channels, and radio stations that do not have a religious dimension. In so doing, Sentinelle in Piedi reclaim the right to communicate beyond mainstream channels. This attitude against media institutions is ambiguous because their silent reading, far from making them invisible, seems designed to attract media attention. For example, the national Italian newspaper La Repubblica (Schiavazzi, Citation2014) described the group as “hypermediated” (iper-mediatici) precisely because it seeks attention unconventionally through silence and the appropriation of space.

The act of reading is also a criticism of media technologies. This criticism may prove ambiguous: while books in public spaces can symbolize a material media form to counter technology, the group needs the Internet for organizational purposes. From my interviews it emerged that the popularity of Sentinelle in Piedi grew thanks to Facebook, where activities and veglie are organized and advertised on the pages of national and local groups. In addition, the criticism of media institutions encourages members of Sentinelle in Piedi to employ the Internet to articulate and circulate their narratives. The aforementioned quote specifies that members of Sentinelle in Piedi refuse media interviews because “all our releases are published on the website’s blog” (Sentinelle in Piedi, Citation2016). Internet venues are often the only space where Sentinelle in Piedi’s intentions and ideas are clearly communicated. The preference for the Internet over other media outlets might be motivated by the greater agency people feel in controlling digital narratives in a given Internet space.

Therefore, the activities of Sentinelle in Piedi exemplify hypermediation through the hybrid use of material (books) and digital (websites, blogs, and social networks) media. At the same time, they show a controversial engagement with media institutions and so-called mainstream media, as their criticism of media is paradoxically mainly articulated on social networks. Campbell (Citation2010) uses the theory of religious-social shaping of technology to explore how religious groups endorse or reject technological devices. In this case, Sentinelle in Piedi are not against technology per se, but they seem to be suspicious of certain media venues and oppose media institutions through a selective use of technology. Fearing that secular media can misunderstand their intentions, Sentinelle in Piedi mainly rely on actions they feel in control of, such as public protests and blogs written by their members. Reading in silence, far from suppressing communication, seems to be a criticism of the speed of contemporary society and the circulation of information, based on the remediation of paper books that confers a new symbolic function upon them in the context of social protest. This hybrid use of physical protests, books, and the Internet shows how messages are not simply mediated, but hypermediated through different venues. Hence, groups need to consider media logics to have their voice heard, but also find unconventional venues to rapidly circulate emotional messages. Hence, Sentinelle in Piedi create physical and virtual spaces in public squares and on social networks which are aimed at provoking people’s emotions, a strategy that is also adopted by other anti-gender groups, as the next section explores.

La Manif Pour Tous: Emotional Spaces

Hypermediation posits that some digital venues can function as spaces where people share their emotions. As exemplified by the description of Sentinelle in Piedi’s performances, anti-gender groups frequently employ physical spaces to organize demonstrations and circulate emotional narratives in various online venues. These hypermediated aspects of anti-gender groups can be found in the activities of LMPT in France. Employing pictures found on the official Facebook page and website of La Manif Pour Tous, I will further explain how the group employs material aids to demarcate physical and virtual spaces, and how it uses the Internet to enhance visibility of emotional performances.

Anti-gender groups usually organize their protests by planning the role of space, in both offline and online terms. Sentinelle in Piedi demarcates space in public squares by standing in silence, and LMPT organizes marches where people sing and wave flags. In so doing, LMPT often employs its logo – a stylized representation of a family with a man, a woman, a boy, and a girl holding hands – to visually mark its space of action. The logo is generally printed on a pink, blue, or white background, and ideologically connects the groups with a traditional notion of “Christian” family. When members of La Manif Pour Tous take part in a protest they normally wave flags or wear t-shirts displaying the logo. In this way, they symbolically demarcate the space of the protest with the presence of the symbol, as shows. The effect is that of colorfulness and the logo tends to visually dominate the space. In some instances, the group places giant flags with the logo in public places, as exemplified in . This is probably a performance to attract attention, among other things because LMPT, unlike Sentinelle in Piedi, seeks interaction with the press. These displays are then circulated via social networks on the group’s national and official pages, which are usually immediately recognizable through the presence of the logo in their profile pictures. The Internet allows pictures of the demonstration to spread rapidly and this has arguably resulted in the logo becoming visible in online spaces. In this way, LMPT’s social media presence is characterized as a space where users can find certain types of anti-gender narratives.

Figure 3. LMPT official Facebook page, available at https://www.facebook.com/LaManifPourTous/photos/a.2995577050472422/2995577470472380/?type=3&theater (accessed November 4, 2019).

Figure 4. LMPT official Facebook page, available at https://www.facebook.com/LaManifPourTous/photos/a.514044101959075/1343439359019541/?type=3&theater (accessed November 4, 2019).

The LMPT logo is widespread at a local, national, and international level. As the group expanded outside France, a number of countries adapted similar logos, including Italy, Finland, and Germany (Metronews, Citation2016). As a result, the logo has become highly charged with values and symbolic meanings. In some cases, the logo does not include the name of the group, probably because its meaning is generally understood and arguably recognized as a symbol of anti-gender activities. When the president of LMPT in France, Ludovine de la Rochère, met with Pope Francis, she gave him a t-shirt with the logo as a present (LMPT, June 12, 2014), framing it as an object symbolizing ideological belonging to the group. Aside from delimitating space, the logo also arguably evokes affective attachments and reactions. It is a symbol that members of anti-gender groups use as an identity marker by displaying it on their clothes, and it makes their ideologies immediately recognizable to outside observers.

The activities of LMPT involve emotions. For example, the group stages performances that have a strong emotional character, and whose impact is enhanced by online circulation. Some LMPT demonstrations have included dolls displayed in shopping carts, as shown in . The dolls symbolize children that are “sold” to same-sex couples via the practices of adoption and assisted reproduction. Affixed to the carts are labels bearing the slogan “neither for sale, nor for rent” (ni a vendre, ni a louer). In other cases, activists push the shopping carts wearing masks or capes, as well as sweaters featuring the aforementioned logo. The circulation of these images is often paired with an emotional language that posits that babies become “merchandise” for same-sex couples to buy, and women who act as surrogates for other couples are “slaves.” The combination of language and images is arguably emotional because it provokes a range of negative feelings, from the disgust and fear of seeing dolls who resemble newborns being put in shopping carts, to the anger and outrage which becomes associated with the practices of adoption and assisted reproduction.

Figure 5. La Manif Pour Tous official Facebook page, available at https://www.facebook.com/LaManifPourTous/photos/a.1208691645827647/1208692159160929/?type=3&theater (accessed November 4, 2019).

Another emotional performance includes young women clothed in white dresses and with red bonnets on their heads (). The costume evokes Marianne, the feminine embodiment of the French nation. The women dressed as various representations of Marianne are also surrounded by French flags, which sometimes are waved during protests together with those displaying the LMPT logo. The women, who are generally young, white, and smiling, also wear sashes bearing the names of the French regions, in what may be an effort to connect the local and national groups. Unlike the shopping carts containing the children, the presence of these women during protests and marches seems to evoke positive feelings. They arguably symbolize purity and youth, and frame anti-gender protests as a nationalist and patriot act that responds to France’s needs. In both these examples, the circulation of pictures online functions as a tool to amplify narratives and maximize their emotional impact among larger sections of the public.

Figure 6. La Manif Pour Tous official Facebook page, available at https://www.facebook.com/LaManifPourTous/photos/a.514044101959075/1233861226644022/?type=3&theater (accessed November 4, 2019).

Therefore, LMPT’s activities in physical and digital venues are intertwined with creating emotional spaces. The group employs the logo to delimit the physical space of protest and the online space of articulating discourse. Visual performances also add an emotional character to the group’s activities. An analysis of LMPT’s pictures and narratives reveals that the group seemingly attempts to provoke feelings of outrage and anger about LGBTQ+ rights. At the same time, it tries to mobilize potential members to take action, both through negative (disdain and disgust for babies “sold” as goods) and positive (the family displayed on the logo, the purity of the young Marianne) sentiments. French flags being waved during performances can be regarded as “sticky objects” used to cater to specific emotions – in this case nationalistic attachments. As Ahmed (Citation2014) writes, groups spreading hate often do so by framing their actions as acts of love. LMPT creates fear of a society where LGBTQ+ people can form families and raise children and frames same-sex couples negatively, but it tends to describe its activities and use its logo as a symbol of love for children, the Christian family, and the French nation rather than as something based on homophobia. This example suggests that the theory of hypermediation can be used to understand how groups such as LMPT employ physical performances and digital circulation to create subtle and multifaceted messages that rapidly spread online and offline. Groups such as Sentinelle in Piedi and LMPT show how the proliferation of Internet platforms results in hypermediated spaces with various layers of emotional meaning, from criticism of secular media, to fear of social change, to love of the family and the nation.

Conclusion

This article has proposed the theory of hypermediation as a framework for capturing the hybridity, intense participation, and intertwining of media practices in contemporary religion. Because digital religion increasingly exists across platforms and involves the creation of narratives in different spaces, it is important to assume a theoretical and methodological approach to address the shifting character of contemporary religion and technological developments. The proposed theory of hypermediation attempts to focus on two points which, I would argue, scholars need to consider when studying digital religion: first, the embeddedness of material, institutional, and technological characteristics of media, which creates narratives that no longer imply a straightforward mediation through a single medium; second, the formation of spaces, both in physical and digital venues, which are often charged with emotions.

This has been discussed through the example of anti-gender groups, which are hybrid in the way they blend religious and political messages across spaces. For instance, the group Sentinelle in Piedi creates performances based on the materiality of book reading, both criticizing and attracting the attention of media institutions, while also employing digital media to spread its messages. Moreover, the French group LMPT displays its logo during protests and on social media pages to demarcate certain spaces of action, and circulates pictures of performances with a high emotional value in online spaces, creating venues for affective reactions. These characteristics of media and the ability to create emotional spaces are interconnected: in its use of material, institutional, and technological media features, Sentinelle in Piedi temporarily appropriates public spaces with its silent presence, which arguably provokes emotional reactions when pictures are circulated online; by enacting emotional performances, LMPT employs material and embodied actions that are further amplified though media technologies. Therefore, these examples illustrate the hypermediated character of groups that rapidly spread narratives via different platforms and the use of materiality within digital culture.

The theory of hypermediation aims to offer scholars who are interested in religious groups that employ multiple media forms new tools for thinking about the present media moment, and to analyze some characteristics of contemporary religion, such as hybridity and fluid practices. Through the lens of hypermediation, researchers are invited to look at the interconnections between digital and physical venues and take into account various media platforms, instead of focusing on a single venue. Methodologically, this can be achieved by collecting both textual and visual data from different websites and social networking pages, and then combining it with interviews and ethnographies. An option for future research may be a deeper exploration of the offline activities of anti-gender groups, including a greater number of interviews and more extensive participant observation. It would also be useful to expand the theory from a media ecology perspective (Treré, Citation2019), especially for what concerns digital activism. One limitation of the theory is that it has been elaborated with the European context in mind, which is characterized by significant media diffusion, and thus it needs to be adapted to other contexts. Nonetheless, the theory of hypermediation stresses the importance of the interconnected nature of various media venues and their emotional aspects, which can add nuances to an understanding of complex phenomena that include a variety of actors and communication strategies.

Hypermediation is still a developing theory that would benefit from more empirical studies and further scholarly reflections, and which hopefully can constitute a line of inquiry for future studies. In particular, there are two main developments that, I would argue, deserve attention in future works. First, it is increasingly important that materiality and space be taken into account when studying digital media. This is particularly true for works focusing on digital religion, which often relies on material and physical practices. While the connections between online and offline actions are often explored in the field of digital religion, there is still a lack of attention to the material aspects of the Internet, including how tangible acts and objects (such as religious books and physical performances) are remediated, embedded, and discussed online (Hutchings, Citation2016). Second, it is important to think about current media use as being informed by specific religious meanings, which can be at times ambiguous and contradictory (Campbell, Citation2010). As the case studies have shown, groups can reject the speed of contemporary media use and criticize national media systems, but they may be forced to engage with certain media spaces because contemporary media logics make it inevitable (Hjarvard, Citation2014), or because of exceptional needs such as those created by the COVID-19 pandemic (Huygens, Citation2021). The theory of hypermediation is an invitation to analyze media proliferation not only in terms of how religious groups and individuals use media, but also how they selectively choose certain media venues and critically assess the role of technology in articulating cultural and social values. With these concluding remarks, this article invites its readers to make use of and further elaborate upon the theory of hypermediation to understand how changes in media alter narrative production about religion and physical performances to create new modes of communication across spaces.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdel-Fadil, M. (2019). The politics of affect: The glue of religious and identity conflicts in social media. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture, 8(1), 11–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/21659214-00801002

- Ahmed, S. (2014). The cultural politics of emotion (revised ed.). Routledge Chapman Hall.

- Bhatia, K. V. (2021). Religious subjectivities and digital collectivities on social networking sites in India. Studies in Indian Politics, 9(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2321023021999141

- Bolter, J., & Grusin, R. (2000). Remediation – understanding new media (revised ed.). MIT Press.

- Campbell, H. A. (2010). When religion meets new media: Media, religion and culture, 1st edition, media, religion and culture. Routledge.

- Campbell, H. A., & Evolvi, G. (2019). Contextualizing current digital religion research on emerging technologies. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 5–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.149

- Campbell, H. A., & Tsuria, R. (Eds.). (2021). Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in digital media (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power, 1st edition. Oxford studies in digital politics. Oxford University Press.

- Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2013). Conceptualizing mediatization: Contexts, traditions, arguments. Communication Theory, 23(3), 191–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12019

- Della Ratta, D. (2018). Expanded places: Redefining media and violence in the networked age. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 21(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877917704496

- Djonov, E. (2012). Multimodality and Hypermedia. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 1–5). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0826

- Echchaibi, N. (2017). Hypermediation as an argument. Center for Media, Religion, and Culture, University of Colorado Boulder. Unpublished essay.

- Evolvi, G. (2018). Blogging my religion: Secular, Muslim, and catholic media spaces in Europe (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Evolvi, G. (2020). Anti-gender movements in Europe: Unusual religions and unconventional media. In M. Díez Bosch, A. Melloni, & J. L. Micó (Eds.). Perplexed Religion (pp. 89–102). Blanquerna Observatory on Media Religion and Culture.

- Garbagnoli, S. (2014). ‘L’ideologia del genere: L’irresistibile ascesa di un’invenzione retorica vaticana contro la denaturalizzazione dell’ordine sessuale. AG about Gender – Rivista Internazionale Di Studi Di Genere, 3(6). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15167/2279-5057/ag.2014.3.6.224

- Garbagnoli, S., & Prearo, M. (2018). ‘La crociata anti-gender.’ Dal Vaticano alle manif pour tous. Edizioni Kaplan.

- Graff, A. (2016). ‘Gender ideology’: Weak concepts, powerful politics. Religion and Gender, 6(2), 268–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18352/rg.10177

- Harsin, J. (2018). Post-truth populism: The french anti-gender theory movement and cross-cultural similarities. Communication, Culture and Critique, 11(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcx017

- Herbert, D. (2011). Theorizing religion and media in contemporary societies: An account of religious ‘publicization. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 14(6), 626–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549411419981

- Hjarvard, S. (2014). From mediation to mediatization: The institutionalization of new media. In A. Hepp & F. Krotz (Eds.), Mediatized worlds: Culture and society in a media age (pp. 123–139). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hjarvard, S., & Lovheim, M. (eds). (2012). Mediatization and religion: Nordic perspectives. Nordicom.

- Hoover, S., & Clark, L. S. (2003). Media, home and family (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Hoover, S., & Echchaibi, N. (2014). Media theory and the third spaces of digital religion. Center for Media, Religion, and Culture, University of Colorado Boulder.

- Hutchings, T. (2016). Augmented graves and virtual bibles: Digital media and material religion. In T. Hutchings & J. McKenzie (Eds.), Materiality and the study of religion: The stuff of the sacred. New York: Theology and Religion in Interdisciplinary Perspective Series in Association With the BSA Sociology of Religion Study Group

- Hutchings, T. (2017). Creating church online: Ritual, community and new media (1 ed.). Routledge.

- Huygens, E. (2021). Practicing religion during a pandemic: On religious routines, embodiment, and performativity. Religions, 12(7), 494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070494

- Kováts, E. (2018). Questioning consensuses: Right-wing populism, anti-populism, and the threat of ‘Gender ideology. Sociological Research Online, 23(2), 528–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780418764735

- Kuhar, R., & Paternotte, D. (eds). (2017). Anti-gender campaigns in Europe: mobilizing against equality. Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Lavizzari, A., & Prearo, M. (2018). The anti-gender movement in Italy: Catholic participation between electoral and protest politics. European Societies, 21(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1536801

- Leidig, E. (2021). From Love Jihad to grooming gangs: Tracing flows of the hypersexual Muslim male through far-right female influencers. Religions, 12(12), 1083. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121083

- Lievrouw, L. (2011). Alternative and activist new media (1st ed.). Polity Press.

- Lövheim, M. (2011). Young women’s blogs as ethical spaces. Information, Communication & Society, 14(3), 338–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2010.542822

- Lövheim, M., & Campbell, H. (2017). Considering critical methods and theoretical lenses in digital religion studies. New Media & Society, 19(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816649911

- Martin-Barbero, J. (1993). Communication, culture and hegemony: From the media to mediations. SAGE Publications.

- Metronews (2016). Quand la ‘Manif pour tous’ s’exporte à l’étranger. www.lci.fr/international/quand-la-manif-pour-tous-sexporte-a-letranger-1500646 (accessed November 3, 2019)

- Meyer, B. (2011). Mediation and immediacy: Sensational forms, semiotic ideologies and the question of the medium. Social Anthropology, 19(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2010.00137.x

- Papacharissi, Z. (2014). Affective publics: Sentiment, technology, and politics. OUP.

- Paternotte, D. (2008). Les lieux d’activisme : Le ‘mariage gai’ en Belgique, en France et en Espagne. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 41(4), 935–952. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423908081092

- Peterson, K. (2016). Performing Piety and perfection: The affective labor of Hijabi fashion videos. CyberOrient, 10(1), 7–28. www.cyberorient.net/article.do?articleId=9759

- Peterson, K. (2019). Pushing boundaries and blurring categories in digital media and religion research. Sociology Compass, 14(3), e12769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12769

- Postill, J., & Pink, S. (2012). Social media ethnography: The digital researcher in a Messy web. Media International Australia, 145(1), 123–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1214500114

- Righetti, N. (2016). Watching over the sacred boundaries of the family. Study on the standing sentinels and cultural resistance to LGBT rights. Italian Sociological Review, 6(2), 265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13136/isr.v6i2.134

- Sabaté Gauxachs, A., Albalad Aiguabella, J. M., & Diez Bosch, M. (2021). Coronavirus-driven digitalization of in-person communities. Analysis of the catholic church online response in Spain during the pandemic. Religions, 12(5), 311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050311

- Schiavazzi, V. (2014). La crociata delle sentinelle anti-gay nella piazza dove nacque l’Italia. La Repubblica. https://torino.repubblica.it/cronaca/2014/03/30/news/la_crociata_delle_sentinelle_anti-gay_nella_piazza_dove_nacque_l_italia-82295390/ (accessed November 5, 2019)

- Scolari, C. (2015). From (new)media to (hyper)mediations. Recovering Jesús Martín-Barbero’s mediation theory in the age of digital communication and cultural convergence. Information, Communication & Society, 18(9), 1092–1107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1018299

- Sentinelle in Piedi. (2016). http://sentinelleinpiedi.it/

- Sumiala, J., & Korpiola, L. (2017). Mediated Muslim martyrdom: Rethinking digital solidarity in the ‘Arab spring. New Media & Society, 19(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816649918

- Treré, E. (2019). Hybrid media activism: Ecologies, imaginaries, algorithms (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Williams, R., & Edge, D. (1996). The social shaping of technology. Research Policy, 25(6), 865–899. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(96)00885-2

- Wodak, R., & Bush, B. (2004). Approaches to media texts. In J. D. H. Downing, E. Wartella, D. McQuail, & P. Schlesinger (Eds.), The sage handbook of media studies (pp. 105–122). SAGE Publications.

- Zimmerman-Umble, D. (1992). The Amish and the telephone: Resistance and reconstruction. In R. Silverstone & E. Hirsch (Eds.), Consuming technologies: Media and information in domestic spaces (pp. 183–194). Routledge.