ABSTRACT

Over a period of nine years (2011–2019), I have had the opportunity to engage with – and to contextualize through a decolonial and mental health lens – the growing threats to and the policing of students at different Southern Californian community colleges. These interactions occurred with a non-White majority of students, mainly Xicanas/os, who were present in these community college classes in large numbers. In this paper, I write about a decolonizing teaching strategy that is both culturally sustaining and revitalizing, and conscious of race. Students of Mesoamerican ancestry, identified by the community colleges as Hispanic, benefit when teachers engage them through an Indigenous lens, affording to such students their rightful place as Native Americans to combat forms of trauma and violence. In addition, I outline the initial observations of the Mesoamerican Figurine Project of Rio Hondo College, where students materialized their own views of the human body and self through clay-work and reflective writing. Using the Borderlands lens and the Coatlicue State – I posit “a teaching archaeology of the human body” that nurtures self-determination and births an Indigeneity grounded in land and cosmology.

Introduction

In 2013, I published a document on my website titled “Five Principles of Community in Diverse Learning Spaces in Light of Cultural Transformations” (Garcia, Citation2013). The document began as a revised version of an earlier teaching philosophy (Garcia, Citation2011b). As I updated the text, I began to critically reflect on my brief years in teaching physical anthropology and humanities at different Southern Californian community colleges (Rio Hondo, Cerritos, Chaffey, and Pasadena City College [PCC]). I questioned if the culturally relevant teaching (CRT) strategies of the period were maintaining the aspirations of historically disenfranchised students from varied ancestries amid systemic inequalities (e.g., Paris, Citation2012), trauma, and ongoing forms of violence. At around the same time, Silvia Toscano-Villanueva (Citation2013), a colleague at PCC, had just written about “the healing potential” (p. 30) of the classroom, which she had transformed by integrating the stories of Indigenous people into her lessons. I identify Indigenous people as those of the Western Hemisphere with blood or household ties to all Californian Indian tribes, the Native American, the aboriginal peoples of Canada/Alaska, displaced peoples of Mesoamerica, and the Indigenous peoples of South America. Under Toscano-Villanueva’s (Citation2013) intervention, invited artists, organizers, and medicine people spoke of the ensuing marginalization and policing of her students of color, and in the process, they strengthened revitalization efforts centered on ancestral medicine, ritual, and ceremony. It became the central purpose of Raza Studies Now, and the “Plan de Los Angeles” (see Serna, Citation2016) to disrupt the criminalization of students at the local level with curricula that respond to immediate community needs.

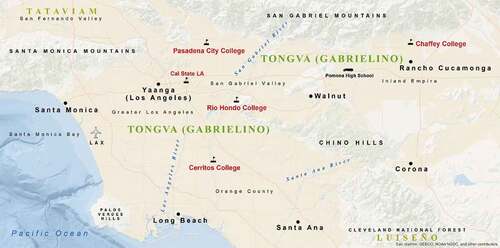

As a member of the Association of Raza Educators Los Angeles Chapter, I devoted much time to training teachers, teaching and mentoring students, conversing freely about mental health, trauma, violence, and the spike in familial deportations under both the Obama and current Trump administrations. In this paper, trauma and violence are identified as any form of physical or psychological experience that affects mental health. Mental health, on the other hand, is acknowledged as the positive mental state of individuals to realize their potential, cope with the normal stresses of life, and still contribute to their communities (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2013). The important understandings that sprang from talks with students transformed into what Elias Serna (Citation2013) refers to as pleito rhetoric – the creation of contending spaces (e.g., Toscano-Villanueva, Citation2013) and the upholding of a Xicana/o consciousness (Urrieta & Méndez Benavídez, Citation2007). I came out as Indian (Alberto, Citation2017), revitalizing aspects of my Native self that has roots in the pueblo of Ixtlahuacán De Los Membrillos, Jalisco, Mexico; the birthplace of my parents, maternal and paternal grandparents, and great grandparents. As an Indigenous Xicano educator, I committed to developing lessons that linked students with vital issues on the Tongva (Gabrielino) territory where we all reside collectively (). In addition to developing rigorous units of learning for all students, I strove to empower students who struggled with low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and trauma, as well as those coming from divorcing households, and from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan. I made a practice of placing family histories and personal student narratives at the center of student learning outcomes (SLOs). I envisioned empowerment as students having control of their own resources and decision-making for their own well-being (Narayan, Citation2005) toward a self-determined and autonomous body. This meant engaging students as agents of change (Freire, Citation2014; Koggel, Citation2009), semillas with innate knowledge (Romero, Arce, & Cammarota, Citation2009), with them trusting that I was devoted to both their well-being and education.

Figure 1. Map showing the sites mentioned in this paper in the Tongva (Gabrielino) territory. Map created by Santiago Andrés Garcia using ArcGIS ArcMap™

In this paper, I write about a decolonizing teaching strategy (Tejeda & Espinoza, Citation2003) that falls in line with a critical culturally sustaining and revitalizing pedagogy (McCarty & Lee, Citation2014), as well as a race-conscious curricula and pedagogical practices (de Los Ríos, López, & Morrell, Citation2015). This is a brief look at some of the strategies I use in the classroom and has similarities to the work of R. Tolteka Cuauhtin (Citation2016). In the classroom, I strive to: 1) revamp Western teaching models that have arisen from racist understandings; 2) facilitate experiences that address the social, political, and mental health goals of disenfranchised groups – that is, the revitalization of ancestral knowledge – of Indigenous students as a response to Article 13 and Article 14 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (United Nations [UN], Citation2008); and 3) transform classrooms into sites where a critical conscious sense of the self is cultivated from an understanding of land and cosmology. In this paper, land and cosmology are defined as the Earth and its moving elements (fire, wind, rain, water, animal relatives, etc.) and the greater Universe visible to the human eye (sky, sun, moon, stars, Venus, etc.). These tenets guide an effort to combat violence against historically oppressed people of color (POC), underserved LGBTQ+ groups, and Indigenous Peoples. The strategy is informed by nine years of observation, ancestral knowledge, and experimental teaching at the community colleges where I work with students that migrate from or have ancestry in Mesoamerica; that is, Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Colombia. Like Juan Gómez-Quiñones (Citation2012), I am conscious of the exchanges between students, teachers, and colleagues that nurture real-life giving and receiving, sparking the sharing of knowledge for the betterment of society. I am working on a shift in my community college teaching, as is Toscano (Citation2016), to bridge the physical and psychological concerns of the disenfranchised with SLOs.

Here, I outline how I serve students of Mesoamerican heritage through an Indigenous lens that takes into consideration ancestry, food, and profound experiences, in addition to race and ethnicity. Jack D. Forbes (Citation1973) worked steadily to teach and engage Mestizas/os of mixed blood as Indigenous; yet, likeminded approaches still have little support from the academy (Miner, Citation2014). Current works (Alberto, Citation2017; Arce, Citation2016; Avila & Parker, Citation1999; Cuauhtin, Citation2016; Garcia, Arciga, Sanchez, & Arredondo, Citation2018; Gómez-Quiñones, Citation2012; Gonzales, Citation2012; Miner, Citation2014; Rodríguez, Citation2014), however, now allow us to interpret and live out the Xicana/o experience in the context of ceremony, maíz culture, and interregional interaction as Native Americans. A more self-determined way of teaching and learning must arise, I argue, as Indigenous people remain marginalized – and criminalized – despite their openness toward assimilating into White-American culture. To offer a decolonizing lesson that is culturally sustaining, revitalizing, and concerned about broad Indigeneities, I introduce the Mesoamerican Figurine Project of Rio Hondo College (http://www.mesofigurineproject.org) (see Part II of this paper) where students work with their hands and clay to materialize and excavate their own “inner consuming whirlwind” Coatlicue (Anzaldúa, Citation2012, p. 68). The ritual attempts to: 1) reclaim ancestral ways of being and becoming, 2) replicate the human body in micro-scale, and 3) allow new meaning of the self to emerge. The work creates real material bodies to arrive at one’s deep self and living realties. Indigeneity surfaces in microform when students write, and extreme heat completes the birthing.

Throughout the paper, I follow Dylan A. T. Miner’s (Citation2014) definition of Indigeneity, as it “represents the inextinguishable right of Indigenous peoples to self-determine who they are, how they govern themselves, and how they define their own knowledge and aesthetic system” (p. 7). To build on Part I, I describe self-determination, and, in turn, Indigeneity, alongside a model for ancestral knowledge revitalization and sustainment in line with land and cosmology.

Writing approach and methodology

This paper takes an autobiographical viewpoint (Lind & Bell-Tolliver, Citation2015). I write about the encounters and verbal exchanges that I often share with students removed from memory, observation, and daily classroom teaching. This knowledge is significant as it involves the details of genuine classroom, family, and community life that, in their moments, take into account the knowledge of all participants as valid and a part of the experience. The accounts of teachers working in the local community then allow the experiences to corroborate one another. As does de Los Ríos (Citation2013), I pull from my own intuition, teaching experiences, and reading of the relevant literature to design student coursework. On a more profound level, the strategies I write of here, both as an instructor and author, are grounded in a pathway involving Ixtlahuacáno history, interregional interaction, and Xochipilli-hongo medicine, which are described in Toscano’s (Citation2016) doctoral dissertation. I am of the belief that for Indigenous educational sovereignty to occur, teaching projects must be multifocal, as many Native American groups find themselves in different stages of rebuilding their lives from the initial cultural genocide and newer forms of colonial violence. In hindsight, I realize that the signs and symptoms of trauma and violence surface in the classroom, and they must be carefully mediated and prevented.

Advancing curricula and the contributions of students of color

A major theme that recurs with young students in community colleges revolves around “the human body and ideology” (López-Austin, Citation1988, p. 162), and how the students see themselves through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. How students wield their body, mind, and spirit, and their ability to achieve their goals affect the pathways they choose and the choices they make. Early positive experiences result in stable mental health in adulthood, whereas individuals who experience trauma at an early age struggle with stress, anxiety, and poor decision-making later in life. This remains true of community college students (e.g., Toscano-Villanueva, Citation2013), many of whom have newly graduated from high school in the process of competing with classmates, while overcoming difficulties. One key element of the self has to do with views concerning sexuality and gender, ethnicity and ancestry. For Indigenous students, and those of African ancestry, particularly, knowledge of the self has been developed and understood from a traumatic form of modern colonialism (Arriaza, Citation2004; Avila & Parker, Citation1999; Goodman & West-Olatunji, Citation2010). According to Arce (Citation2016), Indigenous Xicanas/os have been unrecognized due to the absence of their own cultural learning in public schools. What is missing from the curricula are contributions made by POC, whereby part of the problem stems from an overemphasis on White-American and European achievements. Inclusively, de Los Ríos (Citation2013) reminds us that the curriculum is the main instrument for maintaining the legacy of US hegemony in schools. Tackling this head on, Christine Sleeter (Citation2011) highlights how White people in K-12 textbooks receive the most attention across a range of roles, major stories, and achievements. African Americans appear in the context of slavery, while Asians and Latinas/os appear as participants in history with no real contributions. Sleeter (Citation2011) calls for a nationwide discussion on how our views of society are shaped by racial differences, arguing further that curricula that teach directly about racism have a more profound impact on students than lessons that explore diversity on the surface. Drawing from a bank of ethnic studies literature, Sleeter (Citation2011) argues that a critical approach “produces higher levels of thinking” (p. viii), but more so in White students, as this group is newer to ideas that concern power and cross-racial interaction. Sleeter (Citation2011) reminds us that well thought out lesson plans on race and ethnicity will play a crucial role in a society comprised of people from different ethnic and racial backgrounds.

The work of Cati de los Ríos represents one of many efforts by an urban educator to recognize the contributions of historically marginalized populations. In de Los Ríos (Citation2013), one reads an inquiry with the narratives of her former Pomona High School students. More so, her acknowledgment of students is grounded in three principles: 1) cariño (affection) (Duncan-Andrade, Citation2006); 2) sitios y lenguas (spaces and discourse) (Pérez, Citation1999); and 3) coming into voice (Darder, Citation1991). This strategy, for de los Ríos, informs her understanding of students as each navigates issues of becoming in a dynamic urban community. In the testimonials of de Los Ríos (Citation2013), one reads stories of restorative justice, “youth talking out, and talking back” (p. 68), with students speaking in the realities of POC living in the Borderlands of Mexico and the United States. She takes note of the times, for example, in which students frequently “clowned” on one another in derogatory terms, based on how they looked and talked. Despite this, de Los Ríos (Citation2013) maintains that through the rebuilding of spaces in the community and language discourse, students use their biculturalism and bilingualism to challenge stereotypes of race, class, gender, sexuality, and citizenship status. In one particular narrative, de Los Ríos (Citation2013) describes the experiences of Manuel, a self-identified “Blaxican” of both Mexican and African descent who was not wholeheartedly embraced by his neighbors; a student ridiculed by the Pomona Black community for identifying more with his Mexican side, the side of his birth mother who raised him. de Los Ríos (Citation2013) describes how Manuel took on a passion for learning after reading the autobiographies of Malcolm X and Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzáles – works that spoke of Black and Brown unity, struggling together for social justice during the civil rights and Vietnam-war era. de Los Ríos (Citation2013) notes that Manuel began to recognize the wealth of both his ancestries and, largely, began to define his own shifting identity within the academic world.

In a second example describing how teachers are shifting to a more culturally revitalizing and sustaining teaching strategy, I highlight the work of Silvia Esther Toscano. In a special issue on ethnic studies in The Urban Review (see Urrieta & Machado-Casas, Citation2013), Toscano-Villanueva (Citation2013) wrote of how she integrated Arizona’s Mexican-American Studies (MAS) teaching strategies into her own courses. Like the MAS teachers, Toscano observed that the heavily taught discourse of White-American–European achievements and contributions were “dishonoring and denying the significance of [her students’] personal voices” (Toscano-Villanueva, Citation2013, p. 25) at PCC. Through a revamping of the reading list and collective learning, she sought to reclaim the “I” in her students’ writings as a method of contesting systemic racism, patriarchy, and homophobia. Through their own storytelling, her students explored the benefits of reflective writing and the importance of developing a critical consciousness (see also Acosta, Citation2007). In her hybrid Xicana/o–Sociology course, guest teachers, medicine people, and organizers shared messages concerning the local community. Silvia created lessons that contested the trauma and violence experienced by her students of color. These included the “inheritances of intergenerational traumas as well as emerging from a working-class household, being a first-generation college student, coming from a bilingual home, facing state-deportation, and confronting cultural attacks in the form of racial discrimination among others” (Toscano-Villanueva, Citation2013, p. 26). To earn trust among students, the In Lak’Ech canto (“Tu eres mi otro yo/You are my other I” and “Si te hago daño a ti, me hago daño a mi mismo/If I do harm to you, I do harm to myself”; Valdez, Citation1994) became common practice (e.g., Cuauhtin, Citation2016; Rodríguez, Citation2017). Outside of the classroom, Silvia and her students participated in danza Mexica, the sweat lodge ceremony, and Peace and Dignity runs. In her 2013 paper, she writes that these became a form of psychological intervention emphasizing balance and equilibrium. For Silvia, teaching morphed into a “healing craft” that took into account the spiritual and physical needs of students; a teaching strategy that starts when teachers listen to the values and beliefs of students (Toscano-Villanueva, Citation2013), and that is important for the mental health of diverse peoples.

The Pomona High School student inquiry by de Los Ríos (Citation2013, see also de los Ríos, Citation2017) and the reconstructing of the college classroom at PCC into a space of healing (Toscano-Villanueva, Citation2013; see also Toscano, Citation2016) represent ongoing efforts to break from Eurocentric teaching models. This is essential in a Los Angeles area that is home to the largest diaspora of Indigenous people (Alvitre, Citation2015; Blackwell, Citation2017). When teaching models have at their core the ancestral knowledge of students, they become culturally revitalizing/sustaining and eye opening to the educational and mental health needs of all students. Indigeneity, specifically, “opens dialogues and constructs discourses that previously did not exist” (Gómez-Quiñones, Citation2012, p. 42). Through the lens of a Native Tongva (Gabrielino), the work of Martinez, Teeter, and Kennedy-Richardson (Citation2014), and the Mapping Indigenous LA Project (https://mila.ss.ucla.edu/) promise to revitalize the Native ways of Los Angeles.

Indigeneity, intergenerational trauma, and white supremacy

As a community college instructor, I find it necessary to grasp how the students’ early life experiences (being and becoming), and my own, help to shape our place in society. In this paper, I write of an Indigeneity that surfaces from an ancestral connection to the land. I call it household building sustainability (HBS) (Garcia, Citation2014) and it involves growing food and the attainment of waste building materials for the reconstruction of a sustainable household. Indigeneity, as I embody it, includes sustaining a deep connection to the land (Gómez-Quiñones, Citation2012) that has morphed into efforts to restore understandings of how to thrive, engage medicine, and interpret cosmology. In Red Medicine, Patrisia Gonzales (Citation2012) refers to this as a ceremony of return, in which disagreements become interrupted, and soundness emerges within one’s way of living. I am aware that for some Native people, being Indigenous is solely about getting their land back. For others, it is about having their ancestral remains and materials returned. While some simply want to be left alone to live out their lives peacefully after so much violence. Indigeneity, as I observe it, unravels differently in students and cultivates views of who they are. This, I can attest, drives empowerment in students while instilling a sense of confidence to make meaning of traumatic experiences. In teaching spaces, understanding the students’ values matters as it informs teachers of how to best plan their lessons, and the student’s view of his/her self informs how he/she chooses to engage in the lesson. This is how teachers and students best connect in contesting trauma and violence, and in re-generating learning spaces. It is vital we have knowledge of the self and its relations to introduce one to the other in profound ways. We can say, “This is where I’m from, these are my ways, and I’m related to such. Can you teach me about your way of being?” Yet, this is something that teachers rarely relate in the classroom when lecturing or make room for when planning lessons. In the various courses that I teach, the connections that students embody concerning the land are shared through storytelling and scientific inquiry. In Physical Anthropology, for example, the lessons that I guide students through speak heavily of how organisms vary uniquely but remain similar through nature’s ways. Such a discourse of how the Earth works and its related forms remains central to an Indigenous way of life that centers sustainability, giving and receiving, and caring for plants and animals.

Students of the community college are insightful, vigilant, resilient, and open to knowing more or sharing about their ancestry. Through the practice of listening to students, I have become conscious that not all identify as Xicana/o, and that I serve many personas from diverse tribal backgrounds: Maya, Huichol, Mixtec, Zapotec, Purepecha, Taíno, Native American, and Tongva. Uniquely, Rio Hondo stands out for serving a Mesoamerican majority with an 83% “Hispanic” label. During enrollment, students may choose Native American as their identity; however, individuals of Mesoamerican ancestry, as the statistics show, select Hispanic. A lack of reverence for one’s Native culture may stem from a naturally occurring acculturation process, although it may also stem from intergenerational violence; for example, the taking of Indian lands and the building of boarding schools that devastated Native ways when Europeans settled in the Americas. Through conversations with senior students, I am aware that many were encouraged to assimilate and instructed not to speak Spanish or their tribal language for fear of being discriminated against. Maíz scholar, Roberto Cintli Rodríguez (Citation2014), reminds us that Xicanas/os, because of de-Indigenization policies, “have generally not been recognized by society, or by themselves, as Indigenous, though this is now changing” (p. 42). Although it can be challenging at first, the Yalalteca-Zapoteca Lourdes Alberto (Citation2017) offers as a strategy for teachers and students – the moment when Latinas/os assert their Indigenous identities in the classroom as a method for theorizing the prejudices surrounding Indian displacement. Native teachers are best suited to provide Native students with a platform to recover critical parts of the self that were lost when their ancestors were forced to assimilate.

Acknowledging Indigenous people’s human rights entails a firm reckoning on the part of governments, schools, and teachers. Since 1521, sovereign regions south of the US border have been sites of systemic crimes against humanity and ecological devastation by European and US armed forces, as well as equally responsible corrupt local governments (Arriaza, Citation2004; Godina, Citation2003). The theft of land and natural resources remains the driving force behind the diaspora of Native American students who have left their tribal lands. The recent surge of Indigenous children moving and arriving and being separated at the US southern border is evidence of an ineffective and dehumanizing policy. Mobile peoples of Mesoamerica, despite their openness and willingness to assimilate after displacement into White-American culture, are at risk of partaking in what Almaguer (Citation1974; see also Barrera, Citation1979) calls a neocolonial experience, a modern form of racism, sexism, and subtle forms of violence imposed by the goals of imperialism. Threats that are detrimental, rampant, and systemic dominate the social context of historically marginalized students (Goodman & West-Olatunji, Citation2010). Indeed, Indigenous peoples still suffer from heartbreak and envy, the consequences of losing their tribal ways (Avila & Parker, Citation1999). When a young family from El Salvador flees to Los Angeles in response to the invasion of their farms and cities by US paratroopers (Abrego, Citation2017), some obvious war trauma is brought with them that teachers then observe in the classroom. Of the Yaanga (Los Angeles) area, respectfully, members of the Tongva (Gabrielino) have yet to receive federal recognition by the US government. To this day, many of their ancestral grave remains belong to non-Native collections and owners (Martinez et al., Citation2014). These oppressive cycles dominate what Gonzales (Citation2012) refers to as post-Indian stress disorder (PISD), and this has long been held by Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart (Citation2000) as part of the unresolved, cumulative, and painful experiences across generations of Native American people.

In a paper that I presented at Cal State LA (Garcia, Citation2015), and later at PCC, I spoke of the adverse childhood experiences learned of, and of the signs and symptoms observed when engaging community college students: One, students take on assignments without a suitable working space and without household support. Through talks with students, I understand that many live in homes where Elders are absent because of separation/divorce, long hours at work, or deportation. Two, the college drops students for non-payment, or students drop out because of financial crises, while others choose not to buy books crucial to learning. This stems mainly from a low social economic status (SES) that has its roots in an absence of familial support. Three, students enter the classroom with poor reading and writing skills that impede learning, a deficit likely stemming from a specific learning disorder, or an inadequate early education. Through further concerned inquiry, I have come to learn that many of the students I serve are first-generation students, undocumented students, marginalized LGBTQ+ students, victims of sexual violence, and/or DSPS students (students registered with the disabled students’ program), which includes members of the armed forces. Students I engage on a daily basis reveal the following signs and symptoms: frustration, confusion, low self-esteem, stress, anxiety, depression, poor hygiene, and intoxication. As a result, students miss class, battle illness, and disengage from learning. On a more serious level, I often accommodate students with severe conditions such as blindness, epilepsy, diabetes, substance abuse patterns, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) stemming from combat, and cancer. It is common to have students and their therapist sit through a sixteen-week course, and DSPS students often request classmates as note takers. As an adjunct faculty, it is common to teach, lecture, and discuss mental health issues with more than one student on multiple campuses. Unthought-of of when I first began teaching, I now reference the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013) to better understand student well-being. In , I note the most common threats observed, possible causes, and effects on mental health.

Table 1. Common threats observed affecting student mental health at the community colleges

Recurrent forms of humiliation and violence exist in the psychological abuse directed at POC and Indigenous peoples. In April of 2014, for example, the news broke of basketball’s Clippers billionaire owner Donald Sterling’s racist comments toward the African-American community. TMZ (Citation2014, April) reported Sterling’s voice telling his female friend to keep Black people, and basketball Hall-of-Famer Magic Johnson, away from his games. Just weeks after Sterling’s comments, New Hampshire Police Chief Robert Copeland went on record (see Seelye, Citation2014) to call Barack Obama the “N-word,” citing that he fit all the characteristics of “one.” Both White males refused to apologize. Equally disheartening, Los Angeles AM KFI talk radio hosts, of “The John & Ken Show,” frequently degrade POC, and refer to the undocumented as “illegal aliens,” their children as “anchor babies,” and their homelands as “toilets.” They do so without any critical inquiry as to why people migrate to the USA, or knowledge of the long-term effects of US foreign policy on migration patterns and the premature deaths of innocent civilians. A study by Noriega and Iribarren (Citation2013) found that the hosts of The John & Ken Show use extensive falsehoods, divisive language, and dehumanizing metaphors to marginalize peoples of Mesoamerican ancestry, in particular, the undocumented. The standing president Donald Trump further amplified the inflammatory and racist vocabularies on a world stage during the 2016 US elections (see Lopez, Citation2017). “Get that son of a bitch off the field,” Trump said, his response to Black NFL athletes taking a knee during the national anthem as a response to racial injustices. A calculated scale of hate speech has reawakened America’s racist origins as evident by the well-organized and armed groups that marched in Charlottesville under Confederate and Nazi flag waving. The protest culminated in the death of a civil rights activist run down with a vehicle by a White supremacist. Racism is alive and doing well in America. It originated from a place of Manifest Destiny that sanctioned the inferiority of Black, Latino, and Native peoples (Ladson-Billings, Citation2008). Informed by the intersections of educational equity, social justice, and human rights, I choose not to ignore the present forms of violence that have arisen from early colonial policies, grounded in White supremacy (Ansley, Citation1989; Mills, Citation2003), and that were meant to eradicate the values of POC. “Chicanos and Puerto Ricans, together with Salvadorian, Guatemalan and Mexican migrants, share the bottom of the racial/ethnic hierarchy of these cities [Los Angeles, Chicago, or Philadelphia] with African-Americans, Native Americans, Filipinos and Pacific Islanders” (Grosfoguel, Citation2008, p. 612). For the historically marginalized, ongoing attacks on the body, mind, and spirit exemplify a neocolonial violence, even after centuries of contributions to and assimilation into White America.

Engaging students through an indigenous lens, ancestral food, and a model of indigeneity

As a major tenet of a decolonizing pedagogy, and as a first step in acknowledging the many Native identities, I approach the “Hispanic” majority as a living Indigenous population, in solidarity with all Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Engaging students as Indigenous stands as one form of intervention, a pedagogical shift, to contest the existing criminalization of Native learners at home and in school. I advocate for this non-Western lens of the human body as a baseline for students to cultivate, upon learning, a strong sense of agency and empowerment. The teacher fitted with an Indigenous lens serves to acknowledge the: 1) phenotypes, 2) ancestry, 3) Native diet, and 4) life narrative shaping the human body and ideology of the student. In line with “the need to reclaim and revitalize what has been disrupted and displaced by colonization” (McCarty & Lee, Citation2014, p. 103), an Indigenous lens asks how the most important aspects of a person’s culture may be unearthed and sustained. A Native diet, in particular, although not the only component, remains vital to maintaining a healthy metabolic rate, and, in turn, good health and agency. In addition to nourishing the body, food ways remain central to how one’s culture is passed from generation to generation. Seemingly, Rodríguez (Citation2014) argues that attempts to destroy Indigenous Mexican culture (to assimilate it into an Anglo-American way of life) stand little chance against an Indigenous cuisine that is seven thousand years old. This remains central to a Mesoamerican culture that Rodríguez (Citation2014) points out is sustained by a reliance on corn, beans, and squash. These three sisters – along with wild tomato, chili, and aguacate – provide the appropriate balance of nutrition and ingredients needed for positive human health.

In urban spaces, ancestral food choices have spread through revitalization efforts to help remedy many of the health conditions and illnesses damaging to Native health. The Chia Café Collective of Southern California (https://www.facebook.com/ChiaCafeCollective/) implies this as one of its main objectives: “Reconnecting California Native plants as food, medicine, and utilitarian uses and the ‘gifts’ they provide our human/non-human communities.” In Tending the Wild: Decolonizing the Diet, Tongva community member Craig Torres (Citation2016) advocates strongly for the taking back of human health through Native dieting and the acknowledgment of Indigenous people, their water, plants, and animals. I write about food sovereignty in Garcia (Citation2014), where I model the importance of growing your own food as a contribution to the “Household Clinic” () in fighting against health threats and diseases, and the importance of the three sister foods in the communication of positive family values. As a revitalizing measure, all courses taught under my instruction contain units on raw, healthy, and Native subsistence dieting, along with learning about plants and their medicinal importance. As Gonzales (Citation2012) notes, “kinship with nature and plant knowledge/plant healing is part of family medicine” (p. xxiv). Land-consciousness and naturally cultivated foods and household materials must be central to our lives, because that is where our livelihoods and teachings originate. All societies, all people, for that matter, have a profound and medicinal understanding of plants and animals, and that knowledge must be part of what we teach if we are to address and prevent adverse health outcomes in students related to poor diet. Maintaining an ancestral diet is crucial to the Household Clinic and a part of keeping the Indigenous body healthy.

Figure 2. The household clinic (Garcia, Citation2014)

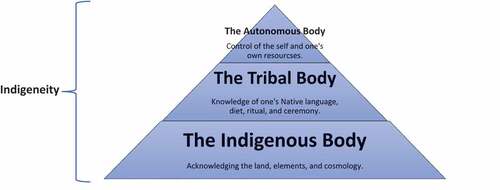

Revitalizing Indigeneity through a cultivation of the Indigenous body () involves three processes: 1) acknowledging the land, elements, and cosmology – the Indigenous Body; 2) knowledge of one’s Native language, diet, ritual, and ceremony – the Tribal Body; and 3) control of the self and one’s own resources – the Autonomous Body. When these three are considered important to life, revitalizing Indigeneity may lead to a more profound tribal identity of one’s own sacred place on this Earth; providing, ultimately, a path for one’s own autonomy for the control of one’s own resources and decision-making. Laying down the Indigenous body through a decolonizing pedagogy represents one method; a foundation on which to revitalize lost ancestral ways of knowing and being. It opens up a host of learning opportunities for the student and the teacher that are not embraced by the Western academy. Only when we engage our “Hispanic” and “Latina/o” students through a lens of land and cosmology will teacher’s best render Native ways of being, history, and instruction (Gómez-Quiñones, Citation2012). The use of terms such as Hispanic and Latino to identify de-Indigenized students fall short of linking bodies to a type of knowledge that is medical in nature and consistently working toward better human health and wellness. Although not all persons of Indigenous ancestry speak their Native language or remain connected to a tribe across time and space, they have the capacity to recover ancestral ways through education, organizing, and ceremony. These remain inherently their own and are connected to the land and cosmology of the Universe. In light of ongoing forms of trauma and violence, such resistance will continue through the creation of decolonizing teaching strategies, and the revitalization of traditional ways. In Part II of this paper, I write about the Mesoamerican Figurine Project of Rio Hondo College as a revitalization effort.

Part II. the mesoamerican figurine project of rio hondo college

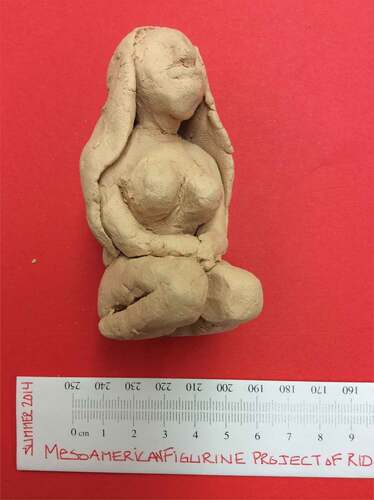

In the summer of 2014, I taught a six-week Humanities 125: Introduction to Mexican Culture class at Rio Hondo College. In Humanities 125, students survey the contributions of Mesoamerican people and their impact on the humanities. I had been teaching the course since 2011, and still do, however, that semester, the lectures and writing exercises were integrated into the Mesoamerican Figurine Project of Rio Hondo College. In addition to meeting SLOs, I made it a priority to grasp my students’ narratives of the human body through an Anzaldúa (Citation2012) Borderlands lens, for its capacity to hone in on the physical and psychological virtues of life. As de Los Ríos (Citation2013) and Toscano-Villanueva (Citation2013) had modeled previously, I validated the experiences of students in light of migration, assimilation, and forms of violence. I strove to cultivate the will to act as an agent of change (empowerment) by allowing students a place where they could tell stories and share their histories. I focused on the human body after observing the signs and symptoms related to the ongoing threats and violence experienced by students (). I had in mind the words of Christine Koggel (Citation2009), who wrote that, “Taking agency seriously involves taking embodiment seriously, and this is because empowerment is enabled through bodies” (p. 251). For three of the six weeks, students worked with their hands and clay to form their own views of the self and body in small figurine scale.

In the following sections, I introduce the project. I describe how I use Anzaldúa’s (Citation2012) Borderlands lens and the “Coatlicue State” –, which led to the creation of the Coatlicue State Writing Exercise. I created this lesson to better understand the experiences and knowledge students bring into the classroom. According to Rashné Jehangir (Citation2010), reflective writing allows students to make sense of their many identities and consciousness through self-authorship. The authoring took place alongside clay-work (Sholt & Gavron, Citation2006) expanded to: 1) reacquaint students with Mesoamerican land ways of knowing and being, 2) serve as a non-invasive therapeutic tool to mediate mental health problems, and 3) assist in reconstructing ideas of the body and self toward a self-determined place to assist in meeting SLOs.

The borderlands lens in humanities 125: introduction to mexican culture

One of the most challenging aspects of working at the community colleges concerns how to best accommodate the many personalities and learning abilities that teachers engage with for roughly sixteen weeks. As colleges accept persons of all backgrounds, its common to get to know adult learners, retired specialists, students with disabilities, the disenfranchised, the undocumented, and recent high school graduates. To take on this task effectively, instructors rely on a host of theoretical lenses and teaching strategies. Knowing this, I chose Borderlands (Anzaldúa, Citation2012) for five reasons: 1) the book is written in tranquil language and students do well with the Spanish translations; 2) Mesoamerican ancestral knowledge systems permeate lengthy parts of the book; 3) the writer-ancestor Gloria E. Anzaldúa models both the positive and adverse realities of a queer Borderlands world; 4) the book is inexpensive, which students appreciate; and 5) the book contains hidden messages that are great for advancing the teaching and SLOs. In Borderlands, Anzaldúa (Citation2012) argues that we must understand individuals through a Borderlands lens that considers the experiences of the unwanted, the ugly, the mutilated, the raped, and the queer. This is life in the Borderlands, she writes, and to many, the borders divide Indigenous tribes across the Americas. In sharing her own queer story, Anzaldúa makes deep appraisals to the Mother Coatlicue of Mesoamerica (), aligning her thoughts with an ancestor that bears both animal and detached human body parts. In her own words:

Coatlicue is one of the powerful images, or “archetypes,” that inhabits, or passes through, my psyche. For me, la Coatlicue is the consuming internal whirlwind, the symbol of the underground aspects of the psyche. Coatlicue is the mountain, the Earth Mother who conceived all celestial beings out of her cavernous womb. Goddess of birth and death, Coatlicue gives and takes away life; she is the incarnation of cosmic processes. (Anzaldúa, Citation2012, p. 68)

Figure 4. The Coatlicue. Pen Drawing by Claudia Itzel Marquez after Wilson G. Turner (Citation2005)

Throughout the Borderlands book, Anzaldúa (Citation2012) summons the Coatlicue, describing her symbolism and perceived meaning. Anzaldúa describes her own internal Coatlicue State, in which she first learned that something was “fundamentally wrong” with her body. She calls her body abnormal, and in dealing with her lesbian sexuality at a very young age, she did everything to hide herself, only to find herself devoured by the Coatlicue. In a pursuit to heal her psyche, however, Anzaldúa writes that our painful disappointments and experiences, if we can make meaning out of them, can lead us to more of who we really are. As many of us often do, she was battling feelings of insecurity, and through some internal form of resistance, she would not give in to the hurting. In a similar style, students of Humanities 125 took the Coatlicue to task, and in the Coatlicue State Writing Exercise, I outlined the following instructions:

I want you all to write about your own Coatlicue State, a time when you had to hide your ideas, yourself, your body, or even your own family, either from shame, ridicule, guilt, oppression, self-fear, or fear of not feeling good enough. I want you all to go deep, allow yourself time to think, and write about when you felt devoured by the Coatlicue in your own Borderlands experience. This exercise is a free write! There are no correct or incorrect responses and using “I” is very much appropriate. (The Mesoamerican Figurine Project of Rio Hondo College, Citation2014)

I asked my students to “go deep.” I was confident that the students would be able to make meaning of the many parts of the Indigenous self – phenotypes, ancestry, diet, and narrative – that exist both inside and outside of the body. In López-Austin’s (Citation1988) the Human Body and Ideology, he writes that the inside of the body is comprised of related parts. What people say and do, what we feel, how we respond, is in a state of transition from one body part to another, which ultimately settles with a greater understanding of the land. The metaphor is in line with the students I observe walking into the classroom with stress, anxiety, and depression (the internal). How students overcome these aspects is through ritual, hustling acts, or pure resiliency (the external). During this period, Coatlicue surfaces into a swollen state of alertness, contesting trauma and violence among the realms of the Earth, its elements, and cosmology.

I am not certain as to how much of an impact the Coatlicue State Writing Exercise had on the mental health of students during the summer of 2014. Openly speaking, psychotherapy, as it is practiced in clinical settings, is not the focus of how I teach and mentor, although I am conscious of the effective potential of teachers to inform and better the health and well-being of students. Contesting trauma and violence simply implies Indigeneity as a measure to mediate and possibly prevent the accumulation of harmful feelings and experiences. In Garcia et al. (Citation2018), I model the most likely therapeutic benefits of clay-work (next section) and reflective writing as pedagogy in the classroom; this literature should be consulted. Elsewhere, Silvia Toscano (Citation2016) has argued that such teaching strategies are needed to begin the recovery from various forms of intergenerational trauma preserved by cycles of oppression. She notes that the forces of assimilation caused serious mental and physical illnesses new to our ancestors; that there was a serious imbalance in our Native communities that now “takes a special kind of training and knowledge to come up with new approaches to healing and to handle new cases” (Toscano, Citation2016, p. 93). In any case, both teachers and students stand to benefit from teaching practices that engage students holistically and involve the sharing of human capital. In his counseling practice, Jose Cervantes (Citation2010) applies a mestizo spirituality to treat individuals of Mesoamerican ancestry with low-level traumas, in which the therapist becomes a spirit companion to the client (see also Avila & Parker, Citation1999). A focus of the treatment centers on both parties situating deep understandings of their own self, family, and community to develop a mutual respect. Cervantes (Citation2010) states that “The psychotherapist is open to learning from the client as this mutual learning forms a basis of equality and mutual respect for each other’s life positions” (p. 533). Similar techniques remain at the core of Toscano’s teaching as a healing craft, and in a similar fashion, the Figurine Project would bridge teaching, learning, and mental health through group work, storytelling, and compassion. During the Coatlicue State Writing Exercise, I observed students in focused and relaxed states. Some chose to write and listen to music on their electronic devices. Some feasted on Native foods that I encouraged students to bring to class, while others chatted quietly among themselves. I recall students being motivated and open to reflective writing, sharing their stories with family, and one student who was also a teacher adopted the project for her elementary students. Students completed work in class where I could guide them through the lessons and writing, as well as facilitate exchanges. With this class in particular, retention was high, and meetings maintained maximum participation.

Working with earth-barro (clay)

The reading of Borderlands (Anzaldúa, Citation2012) and the writing exercises took place alongside the making of the body and material culture in clay form (). For three of the six weeks, students spent about one hour sculpting clay into body parts with their tactile pads, fingers, and palms. I chose clay because I was aware of its use in Olmec times when “cult ceramics” were important in the spread of ritual and ceremony (Garcia, Citation2011a). I was also aware through HBS that working with the hands was helpful in the creation of spatial wellness at the household level, and that it could have positive outcomes in the classroom. In art therapy, therapists and their clients use clay in the exploration of the self and becoming (Sholt & Gavron, Citation2006). In Sholt and Gavron (Citation2006), for example, “clay-work” (p. 66) serves as a non-verbal form of communication (tactile/touch contact). Through clay-work, a person’s psyche’s emotional experiences find expression and validation. The authors note that clay forms represent powerful emotions that were perhaps at one time inaccessible to the client’s consciousness. As “real-like things” (Sholt & Gavron, Citation2006, p. 68) materialize, working with clay enables sculptors to encounter constructive and destructive aspects of the self while in a mental state of changing or forming their identity. Anzaldúa (Citation2012) describes these internal processes, as she herself embodied the Coatlicue eating away at her lesbian body that at the same time was birthing new forms of becoming. The Coatlicue State surfaced when students began sculpting bodies during different stages of life.

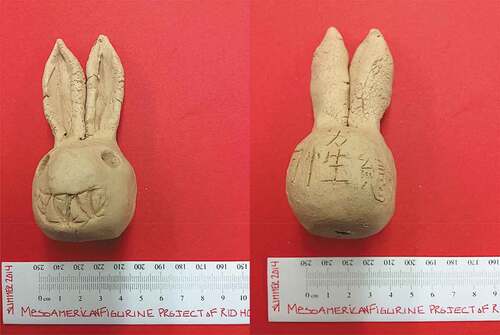

Figure 5. Toothy Bunny. L-Front view, R-Rear view; 兔兒神 (Tu Er Shen). Photos by Santiago Andrés Garcia

Sholt and Gavron (Citation2006) cite the clay’s ability to bridge the physical and psychological realms of human consciousness: “This connection is central in art therapy, an activity that uses art materials [clay], to represent the inner, spiritual world” (p. 66). In a similar fashion to seed sowing and growing food, I trust that shaping clay with the fingers initiates deep primal feelings of belonging, since clay is made from the Earth (see also Sherwood, Citation2004, p. 7). The making of figurines involves Earth, water, and great heat; elements that students learn about and touch, which in ancient times people used in diverse rituals and ceremony. When we turn to Mesoamerican household archaeology, clay figurines inform us of the roles common people play (Blomster, Citation2009; Cheetham, Citation2009). People are shown in both profound and mundane forms: eating, playing, in conflict, in states of homoerotica and sexual fantasy, and existing with the land. Ritual figurine making represents a critical state of becoming that resonates with all people open to connecting with the land and cosmology. I strove to cultivate a critical conscious state of one’s own self in the students through clay-work, exercises, and reflections that fixated on Native foods, plants, and medicine. As an Indigenous educator, I challenged students to arrive at a holistic understanding of the body and its relationships. For that period of the semester, I paced passed the desks of students, walking them through an unearthing of their own bodies via a non-invasive autonomous form of archaeology. This teaching archaeology of the body involved reflecting on the body through writing and dialoguing about the body and sculpting it on a small scale with hands and clay. The goal was to create a material record of the human body, medical in nature, which was perhaps first inconceivable, but now useful in the rebuilding of the psyche in order to bring about new meanings in light of hurtful experiences.

Indeed, many of the figurines tended to embody critical states of being and becoming such as students praying, multiple spirit identities (), the make believe, and sexualized erotica (). Some of the figurines had important inscriptions incised on them such as the head of a Chinese rabbit called “Toothy Bunny” and two canoes with the words “Crow” and “Sioux” carved on their exterior walls (). Other students simply chose to model their facial profiles and cherished foods (). In 2014, Rio Hondo students materialized their own Coatlicue State through clay-work and reflective writing as a first step in contesting trauma and violence toward land-consciousness, self-determination, and body sovereignty. This was my first pedagogical attempt to better understand the mental health challenges of students within a decolonizing pedagogy. In addition to meeting student SLOs, I aimed to generate agency and empowerment in all students. The following is the story of Toothy Bunny, one student’s own Coatlicue State toward the disruption of homophobic violence:

This figurine, for the most part, symbolizes me being a homosexual within the Asian Culture. The Borderland region associated with this figurine is known to be a place where this culture is dominant. I modeled the clay into the likeness of a rabbit which is the symbol of the Chinese god of homosexual love, Tu Er Shen (兔兒神). The name literally means, “rabbit deity.” The story associated with this god is that of persecution and revival. A man, often told to be in a low social class, fell in love with another man of his rank. One day, he sneaked into his love’s quarters, in hopes of glimpsing his naked body. When found, he confessed his love but was sentenced to a horrible death, the cause of which varies from different accounts. Upon his death, which was the result of an act of love, he was elevated to become a god who safeguards those who love men as he did. While the god the figurine was modeled after is benevolent, the smile of the head implies hostility. This is related to the Coatlicue State, where one feels as if in the grips of death but continues to live with inner turmoil. The “toothy smile” symbolizes the defense mechanism homosexuals employ to hide what makes them different from the general majority, all the while living the Coatlicue State. The ears imply some sort of agitation or alertness. This is meant to symbolize how we, the queer, are always on alert to threats or discovery which is often responded to by fleeing. We would withdraw deeper into ourselves and try to bury the queerness within us. Finally, the last icon on this artwork is the Chinese characters at back. The words translate into “male homosexual.” Anybody who has studied Chinese notices the weird positioning of the words. Chinese is written top to down, right to left but the order is written as one writes in English. This is important because it shows the fusion of my two cultures, Asian and American, into one. The characters are written in the back of the figurine to represent how I, like my fellow homosexuals, hid my sexuality so no one knows of it. Much of the symbolism described has negative connotations but the god the figurine is modeled after has a story of hope and rising out of the darkness. This is what I wish to contribute to the humanities. I am certain that my future will be filled with peers of similar cultures. I wish to be a role model to them, that being gay isn’t a bad thing. I hope to help guide them through their journey just as I wished I had a mentor. (Toothy Bunny, The Mesoamerican Figurine Project of Rio Hondo College, 2014)

Institutional review board (IRB) considerations, keeping it realistic, and trauma work

The biggest challenge to the project was pushing boundaries between classroom pedagogy and approved research. Was the Coatlicue State Writing Exercise requiring of IRB approval? Was the clay-work requiring of IRB approval? Was it truly a research project, or just a series of assignments, part of the curriculum? These questions I brought to the attention of the division Dean, who forwarded my concerns to a senior administrator. The outcome was a series of minor recommendations, none of which prohibited the reflective writing or the use of clay-work as pedagogy. Furthermore, Rio Hondo does not have an IRB board for faculty researchers. Teachers who carry out research on campus must be approved by an IRB of their affiliated and approving research institution; I am not a funded doctoral student, and support from the ACLS has only recently arrived.Support for the project came from three sources: 1) students who were enthusiastic about partaking in the summer course activities; 2) the ceramics department that agreed to bisque fire the figurines; and 3) the go-to guide Helping Students in Distress: A Guide for Faculty and Staff published on the Rio Hondo “Helping a Student in Distress” part of the website, and under the Student Health Services Menu. A full version of this guide is found on the California Community Colleges Health & Wellness website (http://www.cccstudentmentalhealth.org/). The handbook states that because faculties are in an excellent place to observe behavioral changes, they are best suited to acknowledging those changes with students, followed by a referral. In the “Guidelines for Intervention and Referral” part of the guide, it offers the following actions: a) be attentive and concerned; b) be willing to help; c) explore ways to effect student morale and hopefulness; d) listen carefully; and e) when in doubt, consult, and refer to the Student Health Center. The philosophy stems from a belief that prevention is preferable to crisis intervention. On page 4 of the latest guide, revised on 8/30/16, it reads: “Extending yourself to others always involves some risk-taking, but it can be a gratifying experience when kept within realistic limits.” In my own case, I was motivated to address the complex issues knowing that I had attained cultural competence over nine years of teaching. I had the support of professionals from clinical and traditional health-related fields, the trust of the students, and confidence in my own abilities to understand the human body and ideology as a trained anthropologist. In the end, I was able to integrate reflective writing and clay-work as teaching units in a Humanities 125 lesson plan. Since 2014, the use of clay-work and reflective writing has been integrated into all assigned humanities and anthropology courses.

Final comments and moving forward

A push on my part nine years ago to develop original teaching materials over those that were readily available led to the development of a decolonizing pedagogy and a project that bridged both SLOs and student health and well-being. I am a much more informed educator today, much more pedagogically equipped, and remain passionate about working for the betterment of student lives. In moving forward, the duty rests with teachers and schools to design frameworks that favor critical pedagogies through an Indigenous lens. When initiated, Indigeneity () may play a larger role in the autonomy and self-determination of student bodies and land-consciousness for a sustainable future, in accordance with their Native way of knowing and being, and in an honorable manner. To serve all students of all backgrounds, Indigeneity cultivates views beyond race and ethnicity; it inclusively entails revitalizing the ancient linkages between humans, land, and cosmology. At the community college, full-time faculty has the muscle to develop such programs, since it facilitates hundreds of students with access to funding, educative resources, and the faculty receives healthy salaries. Full-timers, adjuncts, and counselors observe ineffective school policies, attacks on public education, and the signs and symptoms related to poor mental health in real time. This latter part is of course a pressing and growing issue. As I have shared, when teachers adopt CRT practices with equity and social justice in mind, trauma and violence are pertinent issues that are bound to surface. Teaching in the Borderlands coincides with the hurting events of one’s lives. At what point do teachers address, or not, such human conditions that impede teaching and learning? Are teachers capable of advancing/acquiring a role that has traditionally been the responsibility of licensed clinical professionals? Importantly, who decides when and how trauma is addressed toward a mediation of symptoms that are fast moving and unforgiving to student learning? These questions require a collective discussion with all the involved campus stakeholders. As we await the answers and models, all teachers must be willing and unafraid to redevelop outdated lessons, as well as their own approaches and projects. POC, Indigenous Xicanas/os, are a growing majority, and schools should bear in mind that Western curricula, and other forms of violence, have remained in place and are hurting of our historically marginalized students, their experiences, and revitalization efforts. In hindsight, our students need to know that the community college stands to contest the dehumanizing attacks on the many Native American family groups alive today.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge and thank all past and current students of the Mesoamerican Figurine Project for participating in the clay-work, narrative inquiry, and the excavation of the human body. I thank the American Studies Association for their early recognition of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrego, L. J. (2017). On silences: Salvadoran refugees then and now. Latino Studies, 15(1), 73–85. doi:10.1057/s41276-017-0044-4

- Acosta, C. (2007). Developing critical consciousness: Resistance literature in a Chicano literature class. English Journal, 97(2), 36–42.

- Alberto, L. (2017). Coming out as Indian: On being an Indigenous Latina in the US. Latino Studies, 15(2), 247–253. doi:10.1057/s41276-017-0058-y

- Almaguer, T. (1974). Historical notes on Chicano oppression: The dialectics of racial and class domination in North America. Aztlán, 5(1–2), 27–54.

- Alvitre, C. M. (2015). Coyote tours: Unveiling Native LA. In P. Wakida (Ed.), LAtitudes: An Angeleno’s atlas (pp. 42–52). Berkeley, CA: Heyday.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Ansley, F. L. (1989). Stirring the ashes: Race class and the future of civil rights scholarship. Cornell Law Review, 74(6), 993–1077.

- Anzaldúa, G. E. (2012). Borderlands/la frontera: The new mestiza ( 25th Anniversary, 4th ed). San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

- Arce, M. S. (2016). Xicano/Indigenous epistemologies: Toward a decolonizing and liberatory education for Xicana/o youth. In D. M. Sandoval, A. J. Ratcliff, T. L. Buenavista, & J. R. Marin (Eds.), “White” washing American education: The new culture wars in ethnic studies (Vol. 1, pp. 11–41). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Arriaza, G. (2004). Welcome to the front seat: Racial identity and Mesoamerican immigrants. Journal of Latinos and Education, 3(4), 251–265. doi:10.1207/s1532771xjle0304_4

- Avila, E., & Parker, J. (1999). Woman who glows in the dark: A curandera reveals traditional Aztec secrets of physical and spiritual health. New York, NY: Tarcher/Putnam.

- Barrera, M. (1979). Race and class in the Southwest: A theory of racial inequality. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Blackwell, M. (2017). Geographies of indigeneity: Indigenous migrant women’s organizing and translocal politics of place. Latino Studies, 15(2), 156–181. doi:10.1057/s41276-017-0060-4

- Blomster, J. P. (2009). Identity, gender, and power: Representational juxtapositions in early formative figurines from Oaxaca, Mexico. In C. T. Halperin, K. A. Faust, R. Taube, & A. Giguet (Eds.), Mesoamerican figurines: Small-scale indices of large-scale social phenomena (pp. 119–148). Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Brave Heart, M. Y. H. (2000). Wakiksuyapi: Carrying the historical trauma of the Lakota. Tulane Studies in Social Welfare, 21(22), 245–266.

- California Community College Student Mental Health Program. (2014). Helping students in distress: A guide for faculty and staff. California, CA: Author.

- Cervantes, J. M. (2010). Mestizo spirituality: Toward an integrated approach to psychotherapy for Latina/os. Psychotherapy, Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(4), 527–539. doi:10.1037/a0022078

- Cheetham, D. (2009). Early Olmec figurines from two regions: Style as cultural imperative. In C. T. Halperin, K. A. Faust, R. Taube, & A. Giguet (Eds.), Mesoamerican figurines: Small- scale indices of large-scale social phenomena (pp. 149–179). Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Cuauhtin, R. T. (2016). Healing identity: The organic Rx, resistance, and regeneration in the classroom. In D. M. Sandoval, A. J. Ratcliff, T. L. Buenavista, & J. R. Marin (Eds.), “White” washing American education: The new culture wars in ethnic studies (Vol. 1, pp. 43–66). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Darder, A. (1991). Culture and power in the classroom. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

- de Los Ríos, C. V. (2013). A curriculum of the Borderlands: High school Chicana/o-Latina/o studies as sitios y lenguas. The Urban Review, 45(1), 58–73. doi:10.1007/s11256-012-0224-3

- de Los Ríos, C. V. (2017). Picturing ethnic studies: Photovoice and youth literacies of social action. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 61(1), 15–24. doi:10.1002/jaal.631

- de Los Ríos, C. V., López, J., & Morrell, E. (2015). Toward a critical pedagogy of race: Ethnic studies and literacies of power in high school classrooms. Race and Social Problems, 7(1), 84–96. doi:10.1007/s12552-014-9142-1

- Duncan-Andrade, J. M. R. (2006). Utilizing cariño in the development of research methodologies. In J. Kincheloe, P. Anderson, K. Rose, D. Griffith, & K. Hayes (Eds.), Urban education: An encyclopedia (pp. 451–460). Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Forbes, J. D. (1973). Aztecas Del Norte: The Chicanos of Aztlán. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett.

- Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th Anniversary (30th ed.). New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Garcia, S. A. (2011a). Early representations of Mesoamerica’s feathered serpent: Power, identity, and the spread of a cult (Master’s thesis). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 1495921).

- Garcia, S. A. (2011b). Teaching philosophy [Archived web document]. Retrieved from http://www.whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/teachingphilosophy.pdf

- Garcia, S. A. (2013). Five principles of community in diverse learning spaces in light of cultural transformations [Archived web document]. Retrieved from http://www.whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/principlesofcommunity.pdf

- Garcia, S. A. (2014). Modeling household building sustainability (HBS) with wood, stone, and paint: Achieving spatial wellness in a West Walnut household of the San Gabriel Valley, USA. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 3(2), 865–894.

- Garcia, S. A. (2015). The Mesoamerican clay figurine project of Rio Hondo College: Modeling race, ethnicity, and identity, among community college learners of suburban Los Angeles. Paper presented at the 2015 Mesoamerican Conference in the Realm of the Vision Serpent: Decipherment and Discoveries in Mesoamerica, in Homage to Linda Scheele. California State University, Los Angeles, April 10–11.

- Garcia, S. A., Arciga, M., Sanchez, M., & Arredondo, R. (2018). A medical archaeopedagogy of the human body as a trauma-informed teaching strategy for Indigenous Mexican-American Students. AMAE Journal, 12(1), 128–156. doi:10.24974/amae.12.1.388

- Godina, H. (2003). Mesocentrism and students of Mexican background: A community intervention for culturally relevant instruction. Journal of Latinos and Education, 2(3), 141–157. doi:10.1207/S1532771XJLE0203_02

- Gómez-Quiñones, J. (2012). Indigenous quotient stalking words: American Indian heritage as future. San Antonio, TX: Aztlán Libre Press.

- Gonzales, P. (2012). Red medicine: Traditional Indigenous rites of birthing and healing (1st ed.). Arizona: University of Arizona Press.

- Goodman, R. D., & West-Olatunji, C. A. (2010). Educational hegemony, traumatic stress, and African American and Latino American studies. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 38(3), 176–186. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2010.tb00125.x

- Grosfoguel, R. (2008). Latin@s and the decolonization of the US Empire in the 21st century. Social Science Information, 47(4), 605–622. doi:10.1177/0539018408096449

- Jehangir, R. (2010). Stories as knowledge: Bringing the lived experience of first-generation college students into the academy. Urban Education, 45(4), 533–553. doi:10.1177/0042085910372352

- Koggel, C. M. (2009). Agency and empowerment: Embodied realities in a globalized world. In S. Campbell, L. Meynell, & S. Sherwin (Eds.), Embodiment and agency (pp. 250–266). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2008). A letter to our next president. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(3), 235–239. doi:10.1177/0022487108317466

- Lind, V. R., & Bell-Tolliver, L. (2015). No longer silent: An autobiographical/biographical exploration of a school desegregation experience. The Urban Review, 47, 783–802. doi:10.1007/s11256-015-0334-9

- Lopez, G. (2017, February). Donald Trump’s long history of racism, from the 1970s to 2016. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2016/7/25/12270880/donald-trump-racism-history

- López-Austin, A. (1988). The human body and ideology: Concepts of the Ancient Nahuas (Vol. I). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Martinez, D. R., Teeter, W. G., & Kennedy-Richardson, K. (2014). Returning the tataayiyam honuuka’ (Ancestors) to the correct home: The importance of background investigations for NAGPRA claims. Curator: The Museum Journal, 57(2), 199–211. doi:10.1111/cura.2014.57.issue-2

- McCarty, T. L., & Lee, T. S. (2014). Critical culturally sustaining/revitalizing pedagogy and Indigenous education sovereignty. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 101–124. doi:10.17763/haer.84.1.q83746nl5pj34216

- Mills, C. W. (2003). White supremacy as sociopolitical system: A philosophical perspective. In A. W. Doane & E. Bonilla-Silva (Eds.), White out: The continuing significance of racism (pp. 35–48). Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Miner, D. A. T. (2014). Creating Aztlán Chicano art, Indigenous sovereignty, and lowriding across Turtle Island. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Narayan, D. (2005). Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Noriega, C. A., & Iribarren, F. J. (2013). Toward an empirical analysis of hate speech on commercial talk radio. Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy, 25, 69–96.

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. doi:10.3102/0013189X12441244

- Pérez, E. (1999). The decolonial imaginary: Writing Chicanas into history. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Rodríguez, R. C. (2014). Our sacred maíz is our mother: Indigeneity and belonging in the Americas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Rodríguez, R. C. (2017). Ixiim: A Maiz-based philosophy. Journal of Latinos and Education. doi:10.1080/15348431.2017.1373649

- Romero, A., Arce, S. M., & Cammarota, J. (2009). A barrio pedagogy: Identity, intellectualism, activism, and academic achievement through the evolution of critically compassionate intellectualism. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 12(2), 217–233. doi:10.1080/13613320902995483

- Seelye, K. Q. (2014, May 19). Police official in New Hampshire resigns amid uproar over slur against Obama. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://nyti.ms/2rx9W67

- Serna, E. (2013). Tempest, Arizona: Criminal epistemologies and the rhetorical possibilities of Raza studies. The Urban Review, 45(1), 41–57. doi:10.1007/s11256-012-0223-4

- Serna, E. (2016). “You can ban Chicano books, but they still pop-up!” Activism, public discourse, and decolonial curriculums in Los Angeles. In D. M. Sandoval, A. J. Ratcliff, T. L. Buenavista, & J. R. Marin (Eds.), “White” washing American education: The new culture wars in ethnic studies (Vol. 1, pp. 133–156). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Sherwood, P. (2004). The healing art of clay therapy. Camberwell, Australia: ACER Press.

- Sholt, M., & Gavron, T. (2006). Therapeutic qualities of clay-work in art therapy and psychotherapy: A review. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 23(2), 66–72. doi:10.1080/07421656.2006.10129647

- Sleeter, C. E. (2011). The academic and social value of ethnic studies: A research review. Washington, DC: National Educational Association Research Department.

- Tejeda, C., & Espinoza, M. (2003). Toward a decolonizing pedagogy: Social justice reconsidered. In P. Trifonas (Ed.), Pedagogies of difference: Rethinking education for social justice (pp. 1–12). New York, NY: Routledge Press.

- TMZ. (2014, April). Clippers owner Donald Sterling to GF: Don’t bring black people to my games, including Magic Johnson [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.tmz.com/videos/0_wkuhmkt8/

- Torres, C. (2016). Tending the wild: Decolonizing the diet [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.kcet.org/shows/tending-the-wild/episodes/decolonizing-the-diet

- Toscano, S. E. (2016). Learning to heal, healing to learn: Sacred pedagogies and the aesthetics of a teaching–Healing praxis among Chicana and Chicano educators in Southern California (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://alexandria.ucsb.edu/lib/ark:/48907/f398876z

- Toscano-Villanueva, S. (2013). Teaching as a healing craft: Decolonizing the classroom and creating spaces of hopeful resistance through Chicano-Indigenous pedagogical praxis. The Urban Review, 45(1), 23–40. doi:10.1007/s11256-012-0222-5

- Turner, W. G. (2005). Aztec designs: Dover pictorial archive. New York, NY: Dover Publications.

- United Nations. (UN). (2008). United nations declaration on the rights of indigenous people. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

- Urrieta, L., Jr, & Machado-Casas, M. (2013). Book banning, censorship, and ethnic studies in urban schools: An introduction to the special issue. The Urban Review, 45(1), 1–6. doi:10.1007/s11256-012-0221-6

- Urrieta, L., & Méndez Benavídez, L. R. (2007). Community commitment and activist scholarship: Chicana/o professors and the practice of consciousness. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 6(3), 222–236. doi:10.1177/1538192707302535

- Valdez, L. (1994). Luis Valdez – Early works: Actos, bernabe ́ and pensamieno serpentino. Houston, TX: Arte Public Press.

- World Health Organization. (WHO). (2013). Mental health action plan 2013–2020. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/89966/9789241506021_eng.pdf;jsessionid=EE3C669ED0F8A6ACBBB6D9734EF95069?sequence=1