ABSTRACT

This presents a collaborative autoethnography to examine the impact of COVID-19 and concurrent shifting immigration policy on Latinx undocumented women in higher education. The authors leverage an intersectional lens to analyze the matrix of stressors that impact undocumented students during the pandemic. Findings show that: (1) the impacts of the pandemic were exacerbated by concurrent, rapidly-shifting immigration policy; (2) undocumented students take an increasing role in helping their families navigate and respond to their family’s needs during COVID-19; and (3) both the pandemic and policy shifts created additional instability during key transitions for both DACA and fully undocumented individuals in higher education. This collaborative method of research also creates a space for intersectional praxis through which undocumented students and scholars can build community, mobilize action, and co-produce knowledge. This study builds on the knowledge of the experiences of undocumented students in the pandemic, which can serve as a starting point to create institutional and policy solutions to support undocumented students in recovery from COVID-19.

Introduction

In the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic followed a path of devastation in Latinx communities set in motion by historic structural inequities that increased risk of infection in these communities (League of United Latin American Citizens, Citation2020) and limited opportunities for resource deployment (Jan, Citation2020). Undocumented Latinx students and their families experienced additional vulnerabilities due to their immigration status, structural and economic inequities, and their legal exclusion from most public and employee benefit programs such as health care, paid sick leave, and economic relief programs (Page & Flores-Miller, Citation2021; Wilson & Stimpson, Citation2020). Emerging scholarship has also begun to examine the impacts of COVID-19 on undocumented students’ mental health (Goodman et al., Citation2020), socioemotional states (Andrade, Citation2021), and their experiences on college campuses (Enriquez et al., Citation2021). However, research has yet to analyze the ways in which the pandemic and concurrent shifts in immigration policies from 2020–2021 impacted undocumented students. In this article, we draw on the autoethnography tradition of uplifting marginalized voicesas both a political act and an orientation toward social justice (Conquergood & ThePerformance Studies Reader, Citation2004; Denzin, Citation2003; Ellis, Citation1997; Holman Jones, Citation2016) to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and concurrent shifting immigration policy on our experience as Latinx undocumented women in higher education.

We are a collective of five undocumented/DACAmented, Latinx women living across three different U.S. states and at various stages of our educational journeys. Gloria, a DACA recipient, is a faculty fellow at a graduate institution and a researcher at an institute for health equity. Tatiana is also a DACA recipient. She completed her master’s program in the first year of the pandemic. Rosa and Adelin both completed college during the pandemic, and Fatima transitioned into college during this time. All three of them began the process of applying to DACA when it was reopened, yet only Fatima’s application was fully processed before the program was closed to new applicants for a second time. We each engage in this study as participant ethnographers. Collectively, we use an intersectional lens (Crenshaw, Citation1990) to make sense of our shared experiences during this defining public health crisis and to undertake a praxis of reflection, action, and community-building absent permanent immigration policy solutions. Through this study, we hope to contribute to documenting the experiences of undocumented students and scholars during COVID-19, thereby disrupting the invisibility of undocumented communities in this global crisis. We also mobilize the privileges of scholarship to advocate for building a pathway for pandemic recovery that addresses the inequities produced by unjust immigration policy in the United States.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Latinx and undocumented communities

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated inequities and challenges for undocumented students and their families. Latinx communities have borne the burden of COVID-19 infection rates and mortality (Sabatello et al., Citation2021) and have also been disproportionately impacted by economic hardship during this time (Kerwin & Warren, Citation2020). Although research on the impact of COVID-19 on educational outcomes is still emerging, empirical knowledge from other natural disasters suggests that the impact of the pandemic in working-class communities will result in pronounced educational outcomes disparities (Cruz, Citation2021).

Reports show that more than 200,000 DACA recipients continued working in sectors where there is a labor shortage during the pandemic and in fields that protect the safety and comforts of Americans, such as education, healthcare, and food-related occupations (Svajlenka, Citation2020). Undocumented students and their families were excluded from CARES Act relief, which exacerbated financial vulnerabilities, making it difficult to manage the economic impact of the pandemic (Enriquez et al., Citation2021), despite already living and working in precarious conditions with limited access to resources (Garcini et al., Citation2020). Endale et al., (Citation2020) also found that refugee and immigrant youth face exacerbated negative mental health and psychosocial effects because they depend on social, financial, and other services that were shut down during the pandemic.

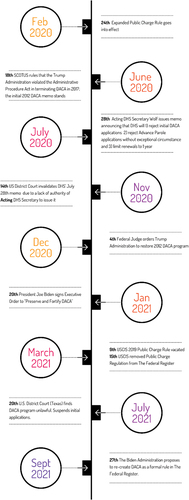

Throughout the pandemic, undocumented students and families have also been impacted by intentional immigration enforcement and shifting immigration policies following various court orders and (in)actions across both the Trump and Biden Administrations (See, ). Despite “Stay-at-Home” orders to mitigate COVID-19 infections, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement raided immigrant communities in California and New York, detained and deported individuals, posing a public health risk to communities and heightening their fear (Lopez & Holmes, Citation2020). Furthermore, multiple studies have documented increased fear and anxiety for self and family due to policies implemented, particularly after Trump took office in 2016 (Andrade, Citation2019; Wray-Lake et al., Citation2018). Intersecting sources of trauma for undocumented students were compounded during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which undocumented individuals had a heightened awareness of the vulnerabilities of their status (Andrade, Citation2021; Liu & Modir, Citation2020).

Intersectionality as a sense-making framework

We use intersectionality (Crenshaw, Citation1990, Citation2017; Hill Collins & Bilge, Citation2020) to guide the sense-making process of the multiple stressors impacting our experiences as undocumented Latinx women in higher education during a time that has also been marked by immense political volatility in immigration policy. Rooted in Black Feminist thought and praxis during the civil rights era, the term “intersectionality” entered legal scholarship in the 1990s (see, Crenshaw, Citation1989, Citation1990; Hill Collins & Bilge, Citation2016) and has since been leveraged across a myriad of fields and disciplines. Intersectionality is concerned with recognizing the ways in which multiple sources of oppression based on socially constructed categories such as race, class, gender, and in our case immigration status, result in exclusion, discrimination, silencing, and violence toward individuals who are ascribed those social categories (Hernandez et al., Citation2015).

We use this analytical framework to examine our experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic as (1) Latinx women in various stages of higher education, which has historically marginalized women and excluded undocumented immigrants (2) undocumented immigrants living in a political climate hostile toward immigrants and (3) part of the working-class or having a working-class background. Yet, intersectionality also serves as a praxis to act and mobilize from within marginal spaces in which we can engage in “criticizing, rejecting, and/or trying to fix the social problems that complex inequalities engender” (Hill Collins & Bilge, Citation2016, p. 39). Adopting intersectionality as praxis allows us to navigate to our own survival across the systems of oppression we are subjected to and to build collective spaces for action, community-building and collective sense-making.

Methods

This study leverages collaborative autoethnography design (Chang et al., Citation2016) to understand our experiences as undocumented women in U.S. higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. This design builds upon earlier autoethnography methods (Conquergood, Citation2004; Denzin, Citation2003; Ellis, Citation1997; Holman Jones, Citation2016) by introducing a collaborative component to the method. This creates additional mechanisms for accountability in both “the process and product” of our shared inquiry (Chang, Citation2013, p. 112) and in the connections we draw between our own stories and the broader sociocultural and political landscape, which is a core function of ethnographic work (Bochner & Ellis, Citation2002).

Data collection

Gloria, Tatiana and Rosa first came together in May of 2021, holding a virtual plática (Fierros & Delgado Bernal, Citation2016; Flores & Morales, Citation2021) to discuss our experiences in the pandemic and to build a space for ongoing reflection and co-production of knowledge around our own experiences. Fatima and Adelin joined the weekly pláticas in the third week, and these pláticas have continued through the time of this publication. In the first plática, we shared our general undocumented stories. Thereafter, we narrowed our conversations to our experiences at the intersection between our undocumented status, our educational journeys, immigration policy shifts, and the pandemic. Transcripts were produced through Zoom, and where transcripts were not available, we relied upon note taking to keep a record of each of our discussions.

We also engaged in reflective writing to complement our pláticas, which has been one of the traditional methods of developing duo- and collaborative autoethnographies (see, Chang, Citation2013; Snipes & LePeau, Citation2017). We each developed a writing prompt question for the group: (1) What did you learn about being undocumented during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) How did the pandemic impact you? (3) How do you understand or process your identity and belonging at this point in time? (4) Where do you find resilience and joy to continue moving forward? These prompts allowed us to engage in self-reflection prior to engaging with each other in conversation. Our writings were available to each other prior to each plática and we began our discussions by sharing observations of common threads in each entry. Through our writing, we created a mechanism to focus our reflections and conversations around our study’s aim as we also balanced the process of building community and holding space for each other during our pláticas.

Data analysis

Following the completion of our writing prompts, we focused the next plática on reflecting on commonalities between our experiences. The first author, then, conducted a narrative analysis of the transcripts and writings (Herman & Vervaeck, Citation2019; Riessman, Citation1993), incorporating the themes that had been collectively highlighted, and organizing these into a table for discussion. Additional themes and examples of themes were added to the table through a collective review. We used the organization of themes to guide our presentation of findings in the following section.

Results

Feeling the shock of the pandemic in our educational journeys

In our first plática, we reflected on the beginning of the pandemic. This was the first time we came together as a collective and also learned about each other’s journeys as undocumented women within the context of education. For most of us, this was the first time that we shared space with other undocumented individuals, and for some, one of the few times throughout the course of our lives to have spoken about our status with others.

Tatiana: When the pandemic struck and everything shut down, I had been living alone in New York City, 2,000 miles away from home, a year and a half into my Master’s program. I contracted COVID-19 early in the pandemic, and I am incredibly lucky that I was not hospitalized. It’s just my mom and me in this country, and she would have been unable to come to my aid. Still, my concern was for her. If she were to get sick, how would she access medical care? And how were we both supposed to stay safe during the spread of an illness that was killing our community one by one? My concerns over the health risk of the pandemic to my mom, the legal environment in the country, and my own emotional state have brought out an emotional and physical reckoning that I was not anticipating. For the first time in my life, I experienced a panic attack. Being undocumented during the pandemic is not for the faint of heart!

Adelin: I was completing my junior year at Chapman. During this time, my mom had her first debilitating anxiety attack that led me to become her primary caregiver. I didn’t know the emotional toll this role would have on my mental health, but the intensity of this pandemic fully hit me when my dad was laid off from his second job. Then, the first stimulus check was issued to only those individuals with social security numbers. I was angry and disappointed in this country.

Fatima: The first few months of the pandemic were tough for me, too. When you live in an immigrant household you never really get to be alone. There are so many priorities for you. It was definitely hard having meetings–even like this one–and I couldn’t turn on my camera because my mom was coming into my room every other second. Doing everything from the apartment became stressful. My parents were behind on paying rent. Most U.S. citizens were given money through the stimulus package, but undocumented people were left without answers. For months and months, my family was not able to pay rent.

Rosa: In early March 2020, all Harvard students were informed of the need to leave campus in four days. Two days later, my mom got laid off from her job and my dad’s construction job became inconsistent. I was granted permission to stay on campus because moving back home would have meant sharing a room with my sister, having unreliable Wi-Fi, and experiencing increased economic instability that would undoubtedly impact my ability to finish my courses in the last semester of my senior year. But even then, I re-entered my role as a navigator, translator and researcher for my family, and this also marked the end of my college experience. In those four days, I said good-bye to mentors, friends and chosen family, transitioned to remote learning while processing a recent ADHD diagnosis, moved to an approved dorm, and took on additional internships to support my family financially.

Gloria: Like all of you, my concerns for my family made the initial phase so scary, well, all of the phases of the pandemic have actually been terrifying. But, the pandemic has taught me that having financial stability as an undocumented person does not mean having peace, and that both peace and stability are so fragile without permanent legal protections. My mom lost her job early in the pandemic, and it made me responsible for household expenses to an extent I was not expecting until they retired. I saw my mom’s stress rise and her self-esteem take a blow because she could not readily find work during the entire first year of COVID. My father continued to work at a restaurant, although with reduced hours, where he was at an increased risk of exposure. As the oldest daughter, I tried to be as reassuring as possible, but I could only think, “This wouldn’t be happening if we weren’t undocumented.”

Research has highlighted the negative impact of COVID-19 on undocumented students’ mental health (Ro, Rodriguez and Enriquez, Citation2021) and access to services for themselves or their families (Enriquez et al., Citation2021). This prior research highlights that stress due to being undocumented is exacerbated during the pandemic, when access to health care and social services is critical (Hill et al., Citation2021). Liu and Modir, (Citation2020) highlight that due to pervasive inequities in communities of color that create cycles of trauma, crises like COVID-19 create “secondary traumas.” Andrade (Citation2021) further explains that,this secondary trauma makes undocumented students’ immigration status even more salient, placing them “in distressful situations” when compared to other students.

For our collective, the pandemic threatened the health, financial and socioemotional stability of our families, placing us–the eldest or only children (daughters)–at the center of managing and caring for the needs of our families during educational milestones. Structural barriers in education already create uncertainty for undocumented students and produce anxiety about the future (Abrego, Citation2006; Bjorklund, Citation2018; Gonzales, Citation2016). Making educational transitions became significantly more complicated during the pandemic, producing additional stress and even greater uncertainty.

Fatima: During the COVID-19 pandemic, both my internship and my school transitioned to virtual settings. I also completed high school, transitioned to college, and applied to DACA during this time. It was so hard to endure, especially when I had to ask for contributions for my cap and gown. I wish I could have had a job during this time to help my family, but I’m also undocumented. Graduating should have been an exciting time, but instead, I wasn’t excited about college. I was scared and felt alone a lot of the time.

Adelin: For me, the idea of virtual school was initially exciting. However, being at home 24 hours a day, seven days a week became exhausting. I had to take on various household duties that slowly impacted my well-being: daily housekeeping, caring for the toddler my mom took care of, and helping my brother with his schoolwork. One of my professors who knew I was undocumented shared my situation with others, and I received contributions from people through Venmo. When I applied to DACA for the first time, I thought that I would get it before I graduated, which would have meant I could get a job right out of college. I had so many hopes, and it was all for nothing.

Rosa: When the pandemic hit, I was in my senior year at Harvard College. My family was economically stable for the first time in over a decade, and while being fully undocumented, I had three opportunities for post-graduate fellowships. The most difficult part was seeing my post-graduate opportunities become severely limited. The transition from Harvard during COVID-19 also meant the end of my medical insurance despite having a history of severe complex chronic migraines that present with neurological symptoms. Before leaving Harvard, my physician and I had a lengthy conversation about what safe rationing of medication could look like to account for the time I no longer had health insurance. It was also the worst time to be losing health insurance. Before the pandemic hit, I felt like I was well on my way from separating my self-worth and value from my undocumented status. The pandemic complicated my transition to post-college life and made me realize that because of the way that undocumented individuals are treated in this country, by republicans and democrats alike, I always need to “prove” my worth, and that is something I am still grappling with today. Living undocumented as an adult during a pandemic forced me to face a reality that I had been sprinting away from for 22 years.

For Rosa and Adelin, being faced with additional financial need as they completed college meant undertaking another internship and searching for financial assistance within their college, respectively. As a high school student, Fatima did not have a financial aid office to turn to for additional assistance, and her internship site was not aware of how to build pathways for compensation through scholarships or stipends for her. Fatima and Tatiana also experienced the isolation of living in states with limited networks that could help them navigate their undocumented status. The pandemic forced physical isolation for safety, yet, for undocumented students, not having access to information or community can limit both opportunity and knowledge related to navigating one’s immigration status in the transition to college or the workforce (Lauby, Citation2017; Raza et al., Citation2019). The rapidly shifting immigration contexts also made it crucial for undocumented individuals to maintain informed about policy changes.

The impact of shifting immigration contexts

We reflected on the cruelty of the proposed Public Charge Rule changes (and other policies) as well as the continued immigration enforcement during a time where the public health crisis already subjected our communities to trauma.

Gloria: It wasn’t only the pandemic. It was the whirlwind of immigration news that shook our community over and over. Building up to the June 2020 Supreme Court decision, I submitted my DACA renewal application and waited more than eight months for approval. After the Supreme Court ruling, I mobilized to fundraise to cover sixteen application fees ($495 each), including Adelin’s, Fatima’s, and Rosa’s, but the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) under the Trump Administration did not allow new applications until late 2020 when a federal judge ordered DHS revise its guidelines. And then, all of a sudden, the program was gone once again, and I had to have conversations with a dozen young people to let them know their application would no longer be considered. I broke down with every conversation. How can we maintain our sanity through this? We’re not just surviving the pandemic; we also have the burden of surviving direct attacks on undocumented communities by the U.S. immigration system.

Tatiana: Yes, one of the things in the forefront of my mind was that we had been waiting to hear the Supreme Court decision on DACA. By June 2020, we knew the decision would come any day, and I didn’t want to be by myself when I heard the news. The day I moved back home was the day the news hit, and while it was a “favorable” ruling, it very well could not have been.

Adelin: It was not good news for all of us. At first, when it was announced that the Supreme Court had allowed the program to open again, attorneys were charging a large sum of money to process applications. I tried calling different non-profit organizations, but all of them had long waitlists. Gloria connected me with an immigration attorney who looked over my application pro bono and she provided me with a check to pay for the fee, so I submitted it in February 2021.

Gloria: It broke my heart that USCIS under the Biden administration took inordinately long to process DACA applications despite his first day executive order to “preserve and fortify” the program.

Adelin: Yeah, that was so meaningless. After five months of waiting and checking the status of my application on a daily basis, I became desperate, and it took a toll on my mental health. I began getting anxiety attacks. In July, just a week after USCIS finally scheduled my biometrics appointment, the federal judge in Texas ruled that the entire DACA program was unlawful and stopped USCIS from processing all initial applications. I felt devastated. It took six months for my application to be processed to the next step, and just 48 hours to cancel everything.

Fatima: I was lucky to apply to DACA in December and it took months for me to obtain it, but I was one of the lucky ones. I remember reaching out to Gloria for the first time via Instagram. I searched up people were undocumented online and found that she had been to Harvard and that she had a Ph.D. I thought if I can find someone successful who is undocumented, I can also do it. I asked her about how to apply to DACA. In my school, I don’t think I really met anybody that’s undocumented and is a girl. I had to explain to my boyfriend that I was undocumented, and he told me not to worry about it. At first he just said, “Apply for a visa or something like that,” because people think it’s so easy, like a two-month process and paying some money. It wasn’t until he took me to my biometrics appointment that he understood. But I was really lucky.

Rosa: When the news broke that the Supreme Court had not allowed for the elimination of DACA in June 2020, I allowed myself to feel a little bit of hope. That hope waned with the passage of time and the non-responsiveness of the Trump administration. By the time a process was announced in November of 2020, I was so numb to the news that it took several reminders for me to begin considering applying for the first time. I set up a meeting with a lawyer in early December and learned that it was not recommended that I submit my application until after Joe Biden was inaugurated. Administrative offices of my high school were closed due to the pandemic, limiting my ability to gather all the supporting documents, and communicating with attorneys was difficult through zoom and email with a case like mine. After finally submitting my application, it was sent back due to an issue with the payment, and I was unable to re-submit due to the Texas federal ruling that came in July 2021. The grief and anger come in waves.

Our discussions on DACA were accompanied by grief, deep pain and anger. Fatima expressed feelings of gratitude, as she would not have to transition to adulthood without some legal protection, albeit temporary. Tatiana and Gloria sought to reconcile the privilege of being protected under DACA for nearly a decade, the frustration of continuing to experience its constant changes, and the uncertainty of the newest court challenge, which has a possibility of ending the program (see: National Immigration Law Center, Citation2022; Svajlenka & Singer, Citation2022). For Rosa and Adelin, the pandemic presented challenges in applying for initial deferred action– from requesting school records, to making appointments with attorneys, to waiting for a decision that was placed on an indefinite hold. As recent college graduates, they also embarked on the challenge of navigating post-college opportunities (Morales Hernandez & Enriquez, Citation2021) with the added disadvantage of having had their last year of college abruptly interrupted by the pandemic.

Beyond the “secondary trauma” (Liu & Modir, Citation2020) of the pandemic, we, as undocumented students and scholars experience a third stressor through both the harmful policies of the Trump administration and the performative (in)actions of the Biden administration. Thus, it was not just students’ “undocumented status and the ongoing perceptiveness of such state” that increased vulnerabilities for students (Andrade, Citation2021, p. 10). Students are further traumatized by the constant changes in immigration policy and the intentional exclusion of undocumented individuals from COVID-19 relief funds. The actions of both administrations rendered undocumented families disposable during the COVID-19 pandemic despite relying on their labor as part of the essential workforce (Hinojosa-Ojeda et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion

In this article, we reflect on our experiences as undocumented women across the educational spectrum during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our collaborative autoethnography underscores the role of immigration policy in creating another layer of harm during the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its resulting financial pressures and emotional stress. The COVID-19 pandemic also made it difficult to enter educational milestones because it disrupted an already uncertain path, especially for those of us who did not have DACA. Our study also shows the ways in which exclusion from economic relief and other social benefit programs affects the life of undocumented students who, beyond meeting their school responsibilities, must also help their families navigate the urgent public health crisis.

Autoethnography been has challenged as a research method, given the introspective and individualized approach to scientific inquiry (Atkinson, Citation1997; Coffey, Citation1999), which can present a limitation to this type of research. In this paper, we strengthen our approach to ethnographic research by: examining our experiences against the context of the broader social context of both the pandemic and immigration policy (Bochner & Ellis, Citation2002) and embarking on a collective approach to autoethnography, which allows for collective analysis and challenging of assumptions of any one particular participant ethnographer (Chang, Citation2013).

Furthermore, the value of the present study is not in presenting largely generalizable findings. Rather, the present study allows for insight into the lives of undocumented Latinx women, leveraging the privileges of academia and methods of research to create visibility for the experiences of undocumented people who have historically been made invisible. This is especially true during the pandemic in which undocumented communities have been excluded from various forms of relief and have been destabilized through consistent immigration enforcement and restrictive immigration policy. To that aim, autoethnography presents a tool for “emancipatory discourse [that] breaks silence” through the agency of storytelling and methods of inquiry (Richards, Citation2008, p. 1723). We hope that this study will also present a starting point by which to integrate policy as a concurrent context in future research related to the experiences of undocumented students and undocumented individuals in the pandemic.

From a policy perspective, a permanent and humane immigration solution would set the foundation for COVID-19 recovery, although additional policy will be needed to correct the disparities caused by the historic inequity that undocumented communities have experienced. College campuses need to actively deploy mental health resources, economic relief from private sources, and support students in accessing post-graduate opportunities in absence of permanent immigration policy that will provide the opportunity for undocumented students to recover from the pandemic.

Despite the ongoing challenges and legal instability that undocumented students are subjected to in the middle of the pandemic, we find ways to leverage intersectionality as praxis for change (Hill Collins & Bilge, Citation2016). Creating the collective described in this article allows us to engage in ongoing reflection to co-learn and co-produce knowledge (Chang et al., Citation2016). This space functions as more than a place to theorize about undocumented identity, and similar collectives have been created by other undocumented Latinx scholars (see, Montiel et al., Citation2020). It allows us to be in community with each other, to act in solidarity, and to uplift our experiences. For some of us, this is the first time we are able to share our experiences as undocumented Latinx women in education, even among other undocumented individuals. Coming together has also allowed us to mutually share resources and support each other through the next steps in the transitions we have begun during the pandemic, from preparing for graduate school to obtaining a first consulting opportunity and entering new jobs or professional roles. Through this model of collaboration, we continue to help each other and mobilize our individual and collective abilities to work side by side with our communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the advisors and mentors who helped them to move forward in their educational trajectory despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrego, L. (2006). “I can’t go to college because I don’t have papers”: Incorporation patterns of Latino undocumented youth. Latino Studies, 4(3), 212–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.lst.8600200

- Andrade, L. M. (2019). “The war still continues”: The importance of positive validation forundocumented community college students after Trump’s presidential victory. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 18(3), 273–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192717720265

- Andrade, L. M. (2021). “We still keep going”: The multiplicitous socioemotional states & stressors of undocumented students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 15381927211000220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2F15381927211000220

- Atkinson, P. (1997). Narrative turn or blind alley? Qualitative Health Research, 7(3), 325–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239700700302

- Bjorklund, P., Jr. (2018). Undocumented students in higher education: A review of the literature, 2001 to 2016. Review of Educational Research, 88(5), 631–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318783018

- Bochner, A. P., & Ellis, C. (Eds.). (2002). Ethnographically speaking: Autoethnography, literature, and aesthetics (Vol. 9). Rowman Altamira.

- Centers for disease control and prevention, demographic characteristics of people receiving COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States, data as of september 21, 2021, access September 21, 2021; https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographics

- Chang, H. (2013). Individual and collaborative autoethnography as method. In Handbook of autoethnography, 107–122. Routledge. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=0QM3DAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA107&dq=individual+and+collaborative+autoethnography+Chang&ots=OztGTiVsQO&sig=8rdNqjg7QIGHEbGHMDOFxLbG5TI.

- Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F., & Hernandez, K. A. C. (2016). Collaborative autoethnography (Vol. 8). Routledge.

- Coffey, A. (1999). The ethnographic self. Sage.

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Policy Press.

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality. John Wiley & Sons.

- Conquergood, D. (2004). Performance studies: Interventions and radical research. (ThePerformance Studies Reader; H. Bial, Ed.). Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 138–167. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/uchclf1989&i=143

- Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

- Cruz, C. (2021). From digital disparity to educational excellence: closing the opportunity and achievement gaps for low-income, black and latinx students. Harvard Latinx Law Review, 24(1), 33. https://harvardlalr.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2021/09/24_Cruz.pdf

- Denzin, N. K. (2003). Performing [auto] ethnography politically. The Review of Education, Pedagogy & Cultural Studies, 25(3), 257–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10714410390225894

- Ellis, C. (1997). Evocative autoethnography: Writing emotionally about our lives. In W. Tierney & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the text (pp. 115–139). New York: State University of New York Press.

- Endale, T., St Jean, N., & Birman, D. (2020). COVID-19 and refugee and immigrant youth: A community-based mental health perspective. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000875

- Enriquez, L. E., Rosales, W. E., Chavarria, K., Morales Hernandez, M., & Valadez, M. (2021). COVID on campus: Assessing the impact of the pandemic on undocumented college students. Aera Open, 7(1), 23328584211033576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211033576

- Fierros, C. O., & Delgado Bernal, D. (2016). Vamos a platicar: The contours of pláticas as Chicana/Latina feminist methodology. Chicana/Latina Studies, 15(2), 98–121. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43941617

- Flores, A. I., & Morales, S. (2021). A Chicana/Latina feminist methodology: Examining pláticas in educational research. In E. Murrillo (Ed.), Handbook of Latinos and Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (2nd edition). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Garcini, L. M., Domenech Rodríguez, M. M., Mercado, A., & Paris, M. (2020). A tale of two crises: The compounded effect of COVID-19 and anti-immigration policy in the United States. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000775

- Gonzales, R. G. (2016). Lives in limbo: Undocumented and coming of age in America. University of California Press.

- Goodman, J., Wang, S. X., Ornelas, R. A. G., & Santana, M. H. (2020). Mental health of undocumented college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.28

- Herman, L., & Vervaeck, B. (2019). Handbook of narrative analysis. U of Nebraska Press.

- Hernandez, K. A. C., Ngunjiri, F. W., & Chang, H. (2015). Exploiting the margins in higher education: A collaborative autoethnography of three foreign-born female faculty of color. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(5), 533–551. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.933910

- Hill, J., Rodriguez, D. X., & McDaniel, P. N. (2021). Immigration status as a health care barrier in the USA during COVID-19. Journal of Migration and Health, 4, 100036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100036

- Hinojosa-Ojeda, R., Robinson, S., Zhang, J., Pleitez, M., Aguilar, J., Solis, V., Edward, T., & Valenzuela, A. (2020). Essential but disposable: Undocumented workers and their mixed-status families. http://www.naid.ucla.edu/uploads/4/2/1/9/4219226/essential_undocumented_workers_final.pdf

- Holman Jones, S. (2016). Living bodies of thought: The “critical” in critical autoethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 22(4), 228–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415622509

- Jan, T. (2020), Undocumented workers among those hit first–and worst–by the coronavirus shutdown. Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/05/undocumented-immigrants-coronavirus/

- Kerwin, D., & Warren, R. (2020). US foreign-born workers in the global pandemic: Essential and marginalized. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 8(3), 282–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502420952752

- Lauby, F. (2017). Because she knew that i did not have a social” ad hoc guidance strategies for Latino undocumented students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 16(1), 24–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192715614954

- League of United Latin American Citizens. (2020). COVID-19 Latino impact report. Retrievedhttps://lulac.org/covid19/Latino_Impact_Report_Form/?fbclidIwAR2uS57pYAtELKuFwhcZ68lzB9Kl9QfJ7jjEXqIvq4QrZZ2B5hewonjVmy8

- Liu, S. R., & Modir, S. (2020). The outbreak that was always here: Racial trauma in the context of COVID-19 and implications for mental health providers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 439. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000784

- Lopez, M. M., & Holmes, S. M. (2020). Raids on immigrant communities during the pandemic threaten the country’s public health. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), 958–959. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305704

- Montiel, G. I., Ramirez, J. I. V., & Perez, I. G. (2020). The emergence of undocuPhDs: A critical testimonio of latinx undocumented students. Border-Lines: Journal of the Latino Research Center, 12, 52–74.

- Morales Hernandez, M., & Enriquez, L. E. (2021). Life after college: Liminal legality and political threats as barriers to undocumented students’ career preparation pursuits. Journal of Latinos and Education, 20(3), 318–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2021.1949992

- National Immigration Law Center. (2022, February 3). DACA. National Immigration Law Center. Retrieved March 17, 2022, February 3, from https://www.nilc.org/issues/daca/

- Page, K. R., & Flores-Miller, A. (2021). Lessons we’ve learned—Covid-19 and the undocumented Latinx community. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(1), 5–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2024897

- Raza, S. S., Saravia, L. A., & Katsiaficas, D. (2019). Coming out: Examining how undocumented students critically navigate status disclosure processes. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(3), 191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000085

- Richards, R. (2008). Writing the othered self: Autoethnography and the problem of objectification in writing about illness and disability. Qualitative Health Research, 18(12), 1717–1728. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308325866

- Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis (Vol. 30). Sage.

- Ro, A., Rodriguez, V. E., & Enriquez, L. E. (2021). Physical and mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among college students who are undocumented or have undocumented parents. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–10.

- Sabatello, M., Jackson Scroggins, M., Goto, G., Santiago, A., McCormick, A., Morris, K. J., & Darien, G. (2021). Structural racism in the COVID-19 pandemic: Moving forward. The American Journal of Bioethics, 21(3), 56–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1851808

- Snipes, J. T., & LePeau, L. A. (2017). Becoming a scholar: A duoethnography of transformative learning spaces. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(6), 576–595. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1269972

- Svajlenka, N. P. (2020). Ademographic profile of DACA recipients on the frontlines of the coronavirus response. Center for American Progress. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2020/04/06/482708/demographic-profile-daca-recipientsfrontlines-coronavirus-response/

- Svajlenka, N. P., & Singer, A. (2022, March 9). Immigration facts: Deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA). The Brookings Institution. Retrieved March 17, 2022, March 9, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/immigration-facts-deferred-action-for-childhood-arrivals-daca/

- Wilson, F. A., & Stimpson, J. P. (2020). US policies increase vulnerability of immigrant communities to the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Global Health, 86(1), 57, 1–2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2897

- Wray-Lake, L., Wells, R., Alvis, L., Delgado, S., Syvertsen, A. K., & Metzger, A. (2018). Being a Latinx adolescent under a Trump presidency: Analysis of Latinx youth’s reactions to immigration politics. Children and Youth Services Review, 87, 192–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.032