ABSTRACT

Academic research networks (ARNs) play an increasingly important role in supporting academics’ research productivity and career development. Research on ARN management has investigated issues related to publishing in English and/or in local languages in different disciplinary and geographic contexts; nevertheless, how lecturers of foreign languages (other than English) in non-western countries manage their multilingual ARNs is under-researched. Employing interview data with 53 Chinese scholars of foreign languages (Japanese, Korean, and Russian) at 10 universities, we examine the types of ARNs they engage with, the roles these play in the research writing and publication process, and their individual agency in network management. Our findings underscore the vital role of ARNs as a form of social capital in research writing and publication, and the situated sociocultural and disciplinary-sensitive nature of ARN management. We identify implications for institutions with respect to local-language academic literacy development and publishing in languages other than English.

Academic research networks (ARNs) are social networks that facilitate the mobility of resources needed for publishing (e.g., Curry & Lillis, Citation2004, Citation2010), and they function as an important form of social capital (Bourdieu, Citation1986/2011) that benefits academics’ research productivity (e.g., Aldieri et al., Citation2018; Hayat et al., Citation2020; Hyland, Citation2015; S. Lee & Bozeman, Citation2005; Melin, Citation2000; Wang, Citation2016), academic influence (e.g., Contandriopoulos et al., Citation2016, Citation2018), and career advancement (e.g., Curry & Lillis, Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2019).

Previous research on ARNs has investigated issues related to publishing in English and/or in local languages from the perspective of academics in the United States and Canada (Contandriopoulos et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Hayat et al., Citation2020; Niehaus & O’Meara, Citation2015), and various European countries (Aldieri et al., Citation2018; Curry & Lillis, Citation2010; Jahić, Citation2016; Kyvik & Reymert, Citation2017; Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004), and with attention to specific disciplines, such as psychology, education, health sciences, business, and computer science (e.g., Contandriopoulos et al., Citation2018; Curry & Lillis, Citation2010; Hayat et al., Citation2020; Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004). Discipline-specific tendencies with respect to ARN types have been noted. For example, informal ARNs tend to be preferred in disciplines such as psychology and education (Curry & Lillis, Citation2010), while formal research groups are more typical in the health sciences (Kyvik & Reymert, Citation2017).

Engagement in ARNs is usually instrumental, strategic, and aimed at strengthening publishing opportunities (Curry & Lillis, Citation2004, Citation2013; Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998). Academics manage their engagement in ARNs through building and navigating relationships, and anticipated reciprocity between members is an important feature of ARN management (Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004). ARNs with strong ties typically display trust and rapport between collaborators, and this benefits research productivity (Jahić, Citation2016; Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004; Melin, Citation2000); ARNs with weak ties are typically shorter lived and serve to facilitate access to resources or research opportunities (Contandriopoulos et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Wang, Citation2016).

Despite the varied disciplinary and geographic focus of previous studies, little is known about how lecturers of foreign languages (other than English) in non-western countries manage their engagement in ARNs. This focus is of interest for three reasons. First, the roles of ARNs in the discipline of foreign language education have specific characteristics not shared by other disciplines. In the case of lecturers of foreign languages who are non-native speakers of their professional language (i.e., the language they teach), networking with colleagues abroad is often conducted through the professional language and involves joint engagement with texts written in that language. The very exercise of participation in ARNs contributes to strengthening the individual’s scholarly identity as an expert user of the language and their academic literacy skills in the language, and it can influence the choice of language for publishing, as elucidated in Ferenz (Citation2005). Second, in light of the lecturers’ ability (or the requirement) to publish in multiple languages (in the local language, in English, and in the professional language), lecturers of foreign languages (other than English) are likely to participate in geographically dispersed ARNs (e.g., in the local academic community, English-language communities abroad, and the research communities in the professional language heritage country/countries), which is facilitated by their multilingual skills. This is different from the types of ARNs reported in previous studies that were only based in English-language and/or local research communities (e.g., Curry & Lillis, Citation2010). Third, ARN management and the agency exercised by multilingual academics in their network interactions can be expected to display context or culture-specific features, as social networking is a context-sensitive activity that requires participants’ awareness of the social, cultural, political aspects of the context in which networks function (Burt, Citation2005). For example, guanxi is often a foundational feature of interpersonal relationships in China (Zhai, Citation2020) and any examination of ARNs within this cultural community would need to take this into account.Footnote1

This study examines how Chinese multilingual academics pursue the objective of enhancing research productivity through engagement in ARNs in multiple research communities. With consideration to sociocultural contexts and disciplinary characteristics, we map out the ARNs that participants engage with, the core dimensions of their ARN participation, the functions of ARNs in facilitating research, and the agency academics exercise in ARN management. To this end, we draw on fieldwork undertaken over four months by the first author at state universities in five regions of China (Tianjin, Hebei, Jilin, Xinjiang, and Gansu) with 53 Chinese scholars of Japanese, Korean, and Russian.

Academics Research Networks of Practice (ARNoPs)

We employ the concept of academic research networks of practice (ARNoPs), as the foundation for mapping out ARN participation, thereby extending the concepts of networks of practice (NoPs) and individual networks of practice (INoPs). Informed by social network theory and community of practice (CoP), Brown and Duguid (Citation2001) emphasized practice as the foundation of networks in their conceptualization of NoPs. They believed that disciplinary “networks of practice cut horizontally across vertically integrated organizations and extend far beyond the boundaries of the latter” (Brown & Duguid, Citation2001, p. 206). The concept of INoPs, as conceived by Zappa-Hollman and Duff (Citation2015), was applied specifically to the analysis of academic (discourse) socialization in second language (L2) contexts. An INoP includes “each individual’s personal relationships within or beyond a social group, community, or institution” (Zappa-Hollman & Duff, Citation2015, p. 339); in their capacity to provide affective and academic support, these relationships contribute to an individual’s discourse socialization (Zappa-Hollman & Duff, Citation2015). Zappa-Hollman and Duff (Citation2015) recognize the hierarchic structure of INoPs which encompasses “nodes (i.e., the individuals with whom a person connects), and clusters (i.e., the labels or identity markers grouping nodes of the same kind)” (p. 339).

Networks can be described with respect to a number of dimensions such as the relative strength of individuals’ ties. Networks with greater time engagement and a higher level of emotional intensity, mutual trust, and reciprocity are considered to have strong ties, while those characterized by lesser engagement and intensity are viewed as having weak ties (Granovetter, Citation1983; Zappa-Hollman & Duff, Citation2015). Curry and Lillis (Citation2010) described a range of other dimensions: local and transnational, formal and informal, durable and temporary. We adopted the definition of formality by Curry and Lillis (Citation2010, p. 284) in our study, who described formal networks as “intentionally fostered or supported by official bodies,” such as top-down research-interest groups, while informal networks were “those arising from shared interests and goals of individual scholars” and typically without official or institutional support, such as individual-to-individual ARNs.

Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that engagement in ARNs is dynamic. Dynamism is explored in relation to the density of co-authorship ties (increases or decreases) among members, the disciplinary-specific or multi-disciplinary nature of these ties, and the extent to which ties expand from local to transnational networks (or vice-versa) in accordance with research priorities and circumstances (e.g., Curry & Lillis, Citation2010; Hayat et al., Citation2020).

Function of ARNs in facilitating research

ARNs function as a form of Bourdieusian social capital (e.g., see Bourdieu, Citation1986/Citation2011, p. 86) that supports academics’ research and publishing objectives in varied ways. Previous studies have demonstrated that ARNs can function as “brokers” of academic literacy (Curry & Lillis, Citation2004, Citation2010; Ferenz, Citation2005; N. Luo & Hyland, Citation2016), bibliographic resources (Curry & Lillis, Citation2010, Citation2013), and grant opportunities (Contandriopoulos et al., Citation2018). ARNs can also facilitate a form of mentorship between junior and senior academics, whereby early career academics can experience ongoing support in the development of their research-related identity and skills (Hopwood, Citation2010; Li et al., Citation2019). These instrumental roles conceptualize ARNs as a form of social capital that can be transformed into cultural capital (e.g., knowledge, skills, publications, conference presentations, academic reputation).

Previous studies have shown that specific types of ARNs perform certain functions with respect to facilitating research practice. For example, networks with weak ties can have a useful bridging function, in that they can connect individuals from different social domains and thereby enable access to diverse resources and ideas (Melin, Citation2000; Wang, Citation2016), and facilitate research-related publishing opportunities (Contandriopoulos et al., Citation2016, Citation2018). However, ARNs with strong ties, which are typically informal individual-to-individual networks, can be very productive with respect to publications (Curry & Lillis, Citation2010; Jahić, Citation2016; Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004; N. Luo & Hyland, Citation2016; Melin, Citation2000), a factor which may be explained by the interpersonal chemistry and trust between collaborators (Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004; Melin, Citation2000).

Researcher agency in ARNoPs

The conceptualization of ARNs as a form of social capital helps us view researcher agency as a social practice that entails strategic engagement with ARNs. Networks, according to Bourdieu (Citation1986/Citation2011, p. 87) are “not a natural given, even a social given,” but rather “the product of endless effort.” In their endeavour to create useful social connections, academics agentively shape ARNs (e.g., by selecting, expanding, reducing), and orient ARNs in response to particular circumstances. Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998) conceptualized human agency from a social practice perspective, referring to actors’ temporary construction of engagement in social situations. Widely accepted or established agentive acts are termed strategies, which involve, according to de Certeau (Citation1984, p. 36), a situated calculation of power.

In the domain of academic publishing, academics need to develop strategies to engage with the expectations of places with power. Such places include their affiliated institution, the publishing market, and government agencies they engage with, as these have the power to formulate explicit or implicit language policies related to academic publishing and to define legitimate research performance through these policies (Liu & Buckingham, Citation2022b).

Previous studies have shown that academics from language-sensitive disciplines (e.g., academics of languages other than English, or LOTE) attach symbolic value (i.e., professional identity) to publishing in their professional language (i.e., the language they teach), and invest considerable resources in this goal despite institutional policies that assign greater value to publications in English. These academics typically perceive such publications as a strategy to strengthen their academic reputation and their researcher identity as an expert in the professional language (Liu & Buckingham, Citation2022b; Tao et al., Citation2019). As identities “are also [constituted] by what we are not” (Wenger, Citation1998, p. 164), these academics thereby differentiate themselves from academics without this strategic level of linguistic expertise.

In circumstances where the use of strategies will not lead to the desired outcomes, individuals may resort to tactics. According to de Certeau (Citation1984), tactics can be explained as an improvised response to obstacles. That is, academics, especially those in weaker positions, may not always have the means to pursue a legitimate response (i.e., adopt a strategy) to the challenges encountered when trying to publish. To respond to such circumstances, individuals need to be resourceful and leverage ARN relations in a manner that is not widely sanctioned. For example, Lowrie and McKnight (Citation2004) reported reciprocal non-authorship as an approach to network expansion, denoting a practice whereby “academics willingly included co-authors on a paper where there was no or very little contribution, in return for the same favour” (p. 357). Although it was justified as “a rightful place in the knowledge exchange process” by Lowrie and McKnight (Citation2004, p. 357), it constitutes a tactic, as it violates the notion of academic integrity (Curry & Lillis, Citation2010).

The manifestation of researcher agency in ARNoPs displays sociocultural-situated attributes. This is because actors need to strategically adapt their engagement with the target community with consideration to the prevailing behavioral norms and values of this community (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998). As professional contexts change, academics need to monitor and evaluate their context proactively, and adapt accordingly. For example, culturally situated agency will typically reflect certain values and beliefs. In the context of China, it is widely believed that the practice of granting favors (renqing) as a type of social exchange should be guided by the understanding that one should not expect an equal exchange or maximize one’s advantages, but rather focus on long-term reciprocity, known as guanxi (Zhai, Citation2004). Thus, renqing is not embodied in isolated acts, but rather in the long-term circulation of favors (Zhai, Citation2004). The reciprocal process of guanxi development and maintenance has been investigated mostly in business domains (e.g., D. J. Lee et al., Citation2001; Vanhonacker, Citation2004). For example, Vanhonacker (Citation2004) argued that well-versed knowledge about when and how to settle the incurred indebtedness received from guanxi is critical for maintaining networks in business settings in China.

Methods

This study is part of a larger project that explored the publishing experiences and strategies of 53 Chinese scholars of Japanese, Korean, and Russian as foreign languages at 10 universities. These particular languages were selected on account of the respective countries’ strategic geographic position bordering China by sea or land (i.e., Russia, Japan, North Korea, and South Korea), and their sophisticated university-level scientific research culture. We surmised that, as a result of these factors, Chinese academics who specialize in these languages would be likely to have opportunities to participate transnationally in networks specific to their professional language. A detailed description of the selection of fieldwork locations, languages, and universities is reported in Liu and Buckingham (Citation2022b).

displays the number of academics of each language according to region, academic rank, highest degree attained, and country where the degree was awarded. The foreign language specialization of these academics is as follows: Japanese (n = 21), Korean (n = 10), and Russian (n = 22). They were at early (Lecturer n = 28), mid (Associate Professor n = 15), and senior (Professor n = 15) career stages. Within the domain of their professional language, their specific research specialization included linguistics (n = 18), literature (n = 12), cultural studies (n = 10), translation studies (n = 7), education (n = 3), business and economics (n = 2), and history (n = 1). The majority possessed a Ph.D. degree (over 60%), a third possessed a Master’s degree (32%), and just three participants (six percent) possessed a Bachelor’s degree as their highest qualification. All had authored multiple scholarly publications, and they held a permanent, full-time academic position with publishing requirements for academic career progression. All participants were born in China and Chinese was the first language of all except the three academics of Chinese Korean ethnicity. These had been educated in Chinese and were competent in both oral and written Chinese.

Table 1. Participant information.

Data collection

The data instruments used in the study involved document analysis (official websites), a questionnaire, and a semi-structured interview. Before contacting the 10 universities, we compiled a research profile for the academics specializing in each of the targeted languages from official websites and the academic publication database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure. For each academic who volunteered to participate, we then elicited initial biographic data using a questionnaire on their academic and professional background, and the networks in which they participated.Footnote2

The subsequent in-person interviews (lasting between 40−60 minutes and conducted by the first author in Chinese) focused on networking as a publication strategy and additional topics that have been reported separately (see Liu & Buckingham, Citation2022b). Questions related to ARNs were further broken down into three categories: types of ARNs, function of ARNs, and strategies to manage networks. We discuss our fieldwork experience in Liu and Buckingham (Citation2022a).

We were guided by participants’ self-assessment of their own network(s) in determining their relative strength. To aid participants in their assessment, at the beginning of the interview we provided an explicit explanation of the definitions and key features of networks with strong and weak ties. For example, the network strength should be measured from multiple perspectives (e.g., frequency, emotional intensity, reciprocal concerns) rather than simply considering the number of publications generated from a specific network.

Data analysis

Transcriptions of the recorded interviews, together with the questionnaire, were analyzed using NVivo 12. We employed a hybrid approach of content analysis and thematic analysis involving three stages. illustrates the three stages of data analysis: content analysis, thematic analysis, and relationship analysis. The first stage entailed the content analysis approach, which, following procedures outlined in Neuendorf (Citation2019), involved developing an a priori template of codes that derived from theory, past research, and possible codes developed from the research questions and our knowledge of the interview content.

We then moved to the second stage, a thematic analysis. This involved an iterative analysis of data to identify additional coding categories. We supplemented the “six-phase” approach to thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013) and Braun et al. (Citation2019) by including a reliability check. As illustrated in , our thematic analysis thus comprised seven phases: data formalization, code development, pattern/candidate theme search, revising candidate themes, defining candidate themes, reliability check, and producing the code book. The reflective and recursive nature of the thematic analysis process is illustrated as follows.

For the code development phase, we coded all data, during which we identified anything and everything of interest and relevance to address our research questions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). We coded the original data by units of meaning (e.g., phrase-level, or clause-level), identified the codes that related to the research questions, and classified them into the priori template of broad categories. The codes identified at this stage all emerged from the original data in a bottom-up manner. That is, we first developed the bottom-level codes and then we collated these bottom-level codes into broader codes. The overarching codes at this stage were still specific and not conceptualized as themes.

Following the guidance in Braun and Clarke (Citation2013), the process of identifying possible candidate themes involved a review of the codes, identifying similarities and relationships, and collapsing the related codes into candidate themes. We revised the identified candidate themes to make them more workable for the purpose of addressing the research questions.

An intra-coder reliability check was conducted four weeks after the initial data analysis by re-coding 30% of the interview transcripts. The average value of Cohen’s Kappa for the interview transcripts was 0.92, which reflects a high level of agreement (McHugh, Citation2012). An inter-coder reliability check involving 20% of the interview data was conducted with the assistance of a Chinese native-speaking Ph.D. student of Applied Linguistics who was familiar with NVivo. The average value of Cohen’s Kappa for both interview transcripts was 0.83, which corresponded to a strong level of agreement (McHugh, Citation2012). The codes with a Kappa value lower than 0.60 (a weak level of agreement) were resolved through discussion.

The third stage of data analysis involved identifying relationships between the codes and the participants’ demographic profile, as shown in . The Matrix Coding function in NVivo 12 enabled a comparison of each code group (i.e., at the parent or child node level) with specific demographic information. For example, we explored the relationships between the participants’ network types and attributes such as ethnicity, gender, university rank, years since graduation, highest degree, and degree awarding country (China or abroad).

ARNoPs of Chinese academics of LOTEs

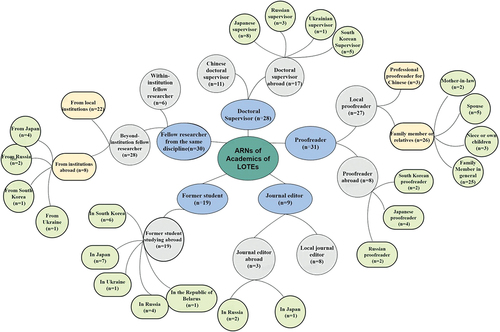

In this section, we report on the multiple ARNs the participants engaged with for publishing purposes and the type of participation from three dimensions: local/transnational, formal/informal, and strong/weak. The participants engaged with various combinations of multilingual ARNs. As depicted in , we identified five main clusters (i.e., social groups) of ARNs: doctoral supervisor (n = 28), fellow researcher from the same discipline (n = 30), proofreader (n = 31), former student (n = 19), and journal editor (n = 9). These were broken down into 11 sub-clusters (i.e., specific instantiations of each cluster) with a location dimension.

All of the identified ARNs were informal individual-to-individual relationships. For example, where the intention was to publish research in Chinese or English, ties to relatives (e.g., family members) who could assist linguistically were important. For instance, participant HBA (who completed her Ph.D. in Japan) asked her family to proofread the manuscript written in Chinese, as she was concerned that her command of academic written Chinese would be likely to be judged inadequate by her colleagues (see Example 1).

Example 1

Interviewer: You just mentioned your difficulties with academic writing in Chinese, but you have eight publications written in Chinese. How did you manage it?

HBA: I sometimes ask my husband to read my manuscript, sometimes my son, especially the first drafts, before I ask my colleagues to read it. It’s somewhat embarrassing if there are many basic language issues when I ask my colleagues to proofread it for me.

Regarding the location dimension of network participation by participants, the participants engaged with both local and international-based ARNs for publishing purposes, but the internationally-based ARNs were all based in professional language heritage countries. No participants reported involvement in ARNs in English-speaking countries and, in response to an interview question prompt, only six participants displayed moderate interest in developing ARNs there in the future. A major concern expressed by participants entailed the challenge of finding a scholar from the respective research field with bilingual competence in English and Chinese or the professional language. This is illustrated in Example 2 by participant HBJ whose expertise lay in Russian-Chinese cultural studies.

Example 2

Interviewer: Have you ever thought of working with scholars from English-speakingcountries and co-authoring papers in English?

HBJ: Yes, but it is too difficult. I mean, if I worked with a scholar from the English-speaking countries, the co-author has to be at least familiar with Chinese culture and Russian culture because it is troublesome to explain “易经” [Pinyin: Yi jing; English: The Book of Changes/I Ching or “八卦” [Pinyin: Ba gua; English: The Eight Trigrams] or other basic concepts like these in ancient Chinese culture. Also, the co-author has to be qualified enough to work on papers in English for publishing and speak Chinese or Russian so we can communicate. It is just too hard, and it’s much easier to find such a co-author from Russian-speaking countries.

The participants’ disciplinary background was a major factor in developing ARNs with scholars from professional language heritage countries. Over half of the participants (n = 27) emphasized that recognition from, and/or collaboration with, the researchers of the professional language heritage country was the way to demonstrate their expertise as a researcher of the respective language, as explained, for example, by participant JLE in Example 3.

Example 3

Interviewer: Why do you still want to develop and sustain your networks in Japan when you know that publications in English can reach a much larger audience and are much more highly valued by your institution?

HBA: Yes, it is much more highly valued by my institution, you know, a much higher score was given to an SSCI indexed journal article. But I study Japanese culture and Japan, of course, is the authoritative country for my research, not any English-speaking countries. My publications in Japanese, especially ones co-authored with Japanese fellow researchers, strengthen my confidence as a researcher of Japanese culture, and strengthen my professional image as well, you know, not in the eyes of my institution, but of researchers in my discipline.

Regarding the strength dimension of the ARN participation by participants, the doctoral supervisor, informal proofreaders for Chinese-written texts (i.e., relatives), and former students were commonly mentioned as ARNs with strong ties, while the editor, professional proofreaders abroad, and fellow researchers from institutions abroad were commonly referred to as constituting ARNs with weak ties. Of note, doctoral supervisors (whether locally or internationally based) featured most commonly in networks with strong ties.

Surprisingly, most participants identified their ARNs with fellow researchers from the professional language heritage country as weak ties; Only the participants who identified as ethnically Chinese Korean reported having stronger ARN ties in the professional language heritage countries (i.e., North and South Korea) than in China. The cross-border proximity was conducive to maintaining regular in-person contact, as illustrated by the experience of participant JLG, located in the university in Jilin province, in Example 4.

Example 4

Interviewer: You’ve published so many papers in Korean in China, and in North and South Korea; that’s so impressive. How did you do it?

JLG: I have an advantage [referring to his Chinese Korean ethnicity]. I have more opportunities to go to North and South Korea as a visiting scholar than the academics from other regions; this isn’t common for most Chinese academics who teach Korean, I think. I’m often invited to attend conferences and give lectures in both North Korea and South Korea. I’m very familiar with the journals in both countries and I have a good understanding of the current academic interests and research trends in linguistics in these two countries.

The strength dimension of ARNs was dynamic. This is illustrated by the ARN participation by returned graduates (i.e., who completed their PhD degree abroad). These academics faced the challenge of reorienting their ARNs from an external to a domestic focus. A major reason for this shift was that the publications in LOTEs received a lower level of recognition in institutional research performance appraisals, although we identified some variation in this owing to institutional and regional autonomy.Footnote3 This reorientation was not automatic, but was usually prompted by unsuccessful attempts to publish in local Chinese discipline-specific journals, which the participants blamed on their relative lack of familiarity with the local research environment and lack of ties to local ARNs. For this reason, some newly returned graduates preferred to continue to publish in the professional language heritage country/countries, as this allowed them to draw on their accumulated discipline-specific knowledge and their long-term investment in ARNs abroad. Participant TJM explains the type of access that she benefited from in Example 5.

Example 5

Interviewer: These papers were published in Japan, right? How did you manage that as a doctoral student?

TJM: Yes, in Japanese. I belong to several research committees in Japan, and this allows me the opportunity to submit my manuscripts to these journals held by these research committees. Without the membership, you wouldn’t be eligible.

Nevertheless, the need to fulfill administrative career progression requirements at the participants’ university in China (including the need to publish in Chinese language journals) inevitably led to an attenuation of links to ARNs in the professional language country. This is illustrated by participant GSD in Example 6.

Example 6

Interviewer: From your publication history, you started to publish in Chinese this year [pointing at the document]. How did that happen? Did that have something to do with your research network?

GSD: When you return, you have to temporarily give up the things you strongly believe in, like publishing in your professional language…I had to work hard to get promoted first, but publications in Japanese were ranked too low, so Japanese is not currently an important language for publishing. And, of course, my guanxi there is fading away…

Despite a weakening of ARNs with strong ties abroad with the progression of time, some returned graduates achieved a temporary balance of their networks in multiple research communities. This was explained in Example 7 by Associate Professor TJA, currently in Tianjin (China), who managed for a period to maintain professionally relevant personal connections and participated in a variety of research-related activities.

Example 7

Interviewer: I noticed from your publication history that you publish in both Chinese and Japanese. Can we say you have reached a balance between publishing in China and in Japan?

TJA: I think at least a temporary balance. I mean, I attend conferences in China, meet Chinese academics at these conferences, and you can see that I mainly publish in Japanese Language Learning and Research and in the Journal of Tianjin Foreign Studies University, because I’ve built personal connections with the editors of these two journals. I also maintained my cooperation with my supervisor. We co-authored some Japanese articles now and then. This balance might not last, because I currently have an increasing number of research projects in China and I may not have enough energy to maintain my contributions on both sides.

After around ten years, all participants who had studied abroad had largely re-oriented their research focus to fit the Chinese context, due to the strength of their ARN ties to the local community. The geographic and cultural proximity and personal, professional, or social network meant that it was easier for participants to exercise agency in the scholarly peer review and publication process. This is explained by HBC in Example 8.

Example 8

Interviewer: It seems you have completely shifted your focus from publishing in Japanese to publishing in Chinese. May I ask what factors contributed to this change?

HBC: Publishing in Chinese at present is more efficient for me. The journals will respond to you more quickly than the Japanese journals, and even if they don't respond to you, you can call the editors if you know them, or ask friends or acquaintances for help who have personal relationships with these editors. If I’m in a hurry to have a publication by a specific date for academic promotion, I can negotiate the date of publication with the editor. The network of contacts in China helps me publish efficiently. I haven’t had regular contact with my supervisor or any academics in Japan for several years now.

The functions of ARNs in research publishing

In this section, we explore the functions of ARNs employed by participants in facilitating research. We identified four categories of functions reported by the participants: bibliographic resource brokers, literacy brokers, publishing space brokers, and research time brokers.

Over 60% of the participants (n = 32) shared their experiences of using ARNs as brokers for bibliographic resources in their professional language. They commonly explained that their affiliated institution had access to the China National Knowledge Infrastructure and international academic databases (e.g., Web of Science, Wiley, Springer, Science Direct); the publications in these databases were mainly in Chinese and English respectively. Access to databases specific to the professional language was rarely offered by institutions. This made it difficult for the academics of LOTEs to keep abreast of trends in their research domain. In the absence of available institutional support, ARNs functioned as important, if not the only, broker to bibliographic resources in the professional language. This is explained the participant XJC in Example 9.

Example 9

Interviewer: Then how did you manage to access literature in your professional language?

XJC: …The only way for me is through our exchange students in Novosibirsk. I tell them what I am interested in, and sometimes the exact names of the books or articles, and ask them to download them from the library at their university…

ARN support became even more important when the sought after studies in the professional language were not available online, as explained by the participant JLE in Example 10.

Example 10

Interviewer: as you have mentioned all these classic literature works were not available online but you needed to do text analyses. How did you manage to access them?

JLE: Thanks to my supervisor. He takes pictures of the chapters I need or scans the books for me. As I mentioned, these books are not available online, and I can't access them anywhere except at the library of that university [in Japan].

Around 90% of the participants (n = 47) mentioned ARNs functioning as literacy brokers in either Chinese, English, or the professional language. Assistance with academic English was limited to writing abstracts for manuscripts in Chinese, as explained by the participant HBH: “for example, in the article, I published in the Journal of Tangshan College this year, I asked my niece to translate my Chinese abstract into English.”

Regarding literacy support for Chinese, the participants often mentioned that their lengthy learning of the professional language had a negative influence on their Chinese academic literacy regarding wording and sentence structure. In such circumstances, they sought informal language support (usually proofreading) from their husband, mother-in-law, or other close family relations. This is described in Example 11.

Example 11

Interviewer: You’ve mentioned the difficulties in writing in academic Chinese, but you still published these papers in Chinese. Did you seek help when you drafted your paper?

JLI: I usually ask my mother-in-law to help, because she is a civil servant and her writing skills are better than mine ... I usually ask her to read through my paper and she always identifies some inappropriate use of words or sentence structure that I can’t spot.

Compared to the informal language support from family members for Chinese and English, the participants resorted to professional proofreaders for manuscripts in the professional language, although they did not always have discipline-specific expertise, as explained, for example, by the participant TJB in Example 12.

Example 12

Interviewer: You’ve published in Korean and in very good journals. Did you seek any language assistance during the process of preparing the manuscript?

TJB: I paid for a proofreader. He was a native speaker of Korean, but he wasn't specialized in my research domain, so he could only revise the general language issues. Even so, I learned a lot from his comments.

Over a quarter of the participants (n = 15) mentioned that participating in ARNs created publishing opportunities. The most frequently reported broker for publishing opportunities was the doctoral supervisor. This is explained by the participant GSI in Example 13.

Example 13

Interviewer: How did you manage to publish in this CSSCI-indexed journal? I heard it was very hard to publish there.

GSI: If I remember correctly, only around 10% of the articles in each issue focus on foreign languages other than English, but all [LOTE] foreign language teachers need to compete for the 10%. You can imagine how fierce it is. I was very excited when I heard my submission was accepted. It was because I co-authored with my supervisor, and he was one of the authority figures in our field.

Another important function of ARNs in facilitating research was as a broker of research time (i.e., contributing in a manner that allows the academic to progress more efficiently). Nearly half the participants (n = 25) emphasized that their weekly teaching load exceeded that of lecturers of English and lecturers of other disciplines. This was due to the more limited number of academic staff for LOTEs, as explained by participant JLD in Example 14.

Example 14

Interviewer: I noticed that you’ve only published one paper while working here as an academic for over three years. Were there any other challenges other than what you just mentioned?

JLD: We have far fewer teachers in our department of Japanese. We only have five teachers. I teach 20 hours each week and teach five subjects. The teachers of English only work 12 to 16 hours per week on average, which is not so different from us, but they only need to prepare one or two subjects. The lesson preparation takes a lot of time. Not to mention the teachers in other faculties, like my husband. He works in the Faculty of Chemistry at our university. He only needs to teach six to eight hours each week and then has time to do experiments in the laboratory.

In addition to workload, family obligations, particularly for female participants, reduced research time. Some participants mentioned the strategy of co-authoring with a network colleague to maintain an active research profile despite time constraints. This is elucidated in Example 15.

Example 15

Interviewer: With so little research time, how did you manage to publish four papers in three years, and in such good journals?

HBF: You can see from my publication history, I usually co-author with these two academics, and I seldom publish by myself since I built guanxi with them. This saves a lot of time and I can nearly double my publications.

Researcher agency in ARNoPs

Researchers’ agency in managing ARNs was manifested in both selecting collaborators and repaying the social indebtedness incurred, and it displayed distinctly Chinese sociocultural features. Participants were concerned about the volume of social debt incurred from favor-seeking from collaborators and, in consequence, made strategic choices with respect to their engagement. Their explanation for this typically drew on the belief that China was a qingli society, which meant that collaborative practices should consider both the affective dimension of renqing and the rational dimension. In other words, from a rational perspective, favor incurred social debt, which should be repaid. As a result, when considering favor-seeking engagement with collaborators, participants gave greater importance to the volume of social indebtedness incurred than the anticipated benefits. For example, the participant XJC resorted to her previous students rather than her friends or doctoral supervisor to access bibliographic resources in Russian, as in her mind this incurred less social debt: “It’s better to owe a student a favor than a colleague or mentor. It’s easier to pay back” [XJC/Interview]. Participants were cautious of the social debt incurred by seeking favours, as illustrated by the traditional Chinese saying, “Bills are easy to repay, favors are not.” Explicit reference was made to this cultural belief by the participant TJB in Example 16.

Example 16

Interviewer: Have you thought about finding someone more qualified of proofreading your manuscript? I mean, someone with some background knowledge about your research field?

TJB: Of course, but it is hard. The academics in my department are accustomed to doing their research individually and I don’t want to owe them, you know, renqing zhai [social debts to repay].

Emphasis was placed on taking a long-term view to the repayment social debts. This practice echoes the traditional Chinese saying: “Chinese people are always grateful for the help they receive, but there is no hurry to return it, as this is not a one-time affair, but a life-long affair.” The participants placed great emphasis on ARN sustainability in the process and commonly mentioned that the recurring processes of giving and taking contributed to the emergence of guanxi. Friendship-type guanxi (Zhai, Citation2020) with network members (e.g., co-authors, Ph.D. supervisors, proofreaders, or colleagues) predominated. This form of guanxi involves acts in which collaborators seek to enhance or maintain one another’s reputation through the exchange of strategic favors (or renqing), and the affective component is an important element.

Participants typically had few forms of debt repayment at their disposal. One approach, negotiating authorship on a publication, constituted a tactic insofar as it is not a socially sanctioned practice within the academy. For instance, a co-author might renounce their authorship as a favor to the second author, or the sequence in which authors’ names were listed might be negotiated to the benefit of the author who required a first-authored publication. This favor (renqing) of gifting authorship contravenes the widely-accepted academic authorship principle, according to which the sequence of authors’ names should reflect the relative contribution of each to the study. The practice is explained in Example 17 by the participant HBF, who had a long-term collaborative relationship with two regular co-authors, and who had thereby increased her rate of publication.

Example 17

Interviewer: And why always these two academics? How do you manage to sustain such a long-term working relationship?

HBF: A very important reason is that everything is negotiable. When I prepared to apply for promotion to Professor several years ago, they all insisted that I be the first author, although they contributed as much as I did. Last year, one of them applied for promotion to Professor, and I gave up my authorship and I asked her to publish it under her name, because I had been promoted to professor and didn't need a publication as much as she did then. Sometimes you take and sometimes you give; that’s the key.

Discussion and conclusion

This study explored the participation of multilingual scholars in academic research networks of practice (ARNoPs) as a strategy to achieve publishing objectives from sociocultural and social practice perspectives. ARN management was a disciplinary-sensitive, socially-embedded, culturally-specific social practice.

Practice was at the core of ARN management and it involved developing, selecting, re-orienting, and engaging with multiple multilingual ARNs, identifying and leveraging the different functions of ARNs, establishing and sustaining culturally-situated reciprocal relationships through researcher agency, and individualized tactics to achieve publishing aspirations.

The ARN participation by Chinese academics of LOTEs manifested sociocultural dimensions. The important contribution of family members, particularly as literacy brokers of Chinese and English, has not been previously acknowledged. Hopwood (Citation2010) claimed (referring to a U.S. context) that academics are likely to view family members as a source of emotional rather than academic support, while Granovetter (Citation1983) asserted that reliance on family members is less likely among individuals of higher socioeconomic status. The importance of family members in this study can be explained by the central role of foreign language linguistic expertise in our participants’ careers and the difficulty of developing (and maintaining) academic writing skills in multiple languages (Gentil, Citation2005), as well as the broader dependence on familial relationships in China than in western countries (Zhai, Citation2020).

ARNs are known to be dynamic configurations (Curry & Lillis, Citation2010; Hayat et al., Citation2020), sensitive to changes in scholars’ interests, experiences, and connections over time (Curry & Lillis, Citation2013). In this study, the ARNs of returned graduates proved to be particularly dynamic, due to the undervalued position of publications in the professional language heritage country in institutional research performance reviews. The subsequent re-orientation of their ARNs from an external to a domestic focus illustrates the context-sensitive and socially-embedded nature of ARN management. This implies that effective management of ARN depends on academics’ level of understanding of the social, cultural, and political contexts in which their networks function (Burt, Citation2005).

Distinct disciplinary features and variations within the discipline were noticed regarding the network dimension, which has been under-reported in previous research on ARN management (e.g., Curry & Lillis, Citation2004, Citation2013; Hayat et al., Citation2020; Wang, Citation2016). Chinese academics of LOTEs relied on informal individual-to-individual ARNs to assist the progress of research publishing, which confirms the tendency of academics from soft disciplines to engage in informal networks with strong trust-based and friendship linkages (Curry & Lillis, Citation2010; Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004; N. Luo & Hyland, Citation2016; Melin, Citation2000). This suggests that ARN management by academics in soft disciplines typically displays variation in forms of network participation at the individual level on account of the differences in individual researcher agency.

ARNs were typically cross-institutional, cross-regional, and cross-national. The latter were typically connected to professional language heritage countries rather than English-speaking countries, which was common among academics from other disciplines, as reported in Contandriopoulos et al. (Citation2018), Curry and Lillis (Citation2010), Hayat et al. (Citation2020), Hultgren (Citation2014), and Lowrie and McKnight (Citation2004). Where the academics’ ethnic background corresponded to their language specialization, as in the case of the Chinese Koreans, the ties with researchers from the heritage country (i.e., North or South Korea) were particularly strong. Nevertheless, the professional identity of all academics as a LOTE scholar was strengthened through engagement with ARNs in the professional language heritage countries, and this reduced their motivation to develop ARNs in English-speaking countries. That is, their professional identity drew from both participation and non-participation in particular communities of practice (Wenger, Citation1998).

In language-specific fields, ARNs typically possess discipline-specific features. A primary function of ARNs involved the provision of scholarly language-specific support (i.e., for Chinese, English, or the professional language). This support was particularly important to access (usually country-specific) bibliographic resources and literacy brokering in the professional language, and thus differed from the previously documented more generic (not country-specific) English-language literacy and bibliographic support sought by academics from other disciplines (see Bardi, Citation2015; Burgess et al., Citation2014; Curry & Lillis, Citation2010). The academic language-specific support enabled academics to transform their social capital (that is, their acquaintanceship with strategically-placed people) into certain forms of cultural capital (e.g., published research articles, and expertise in academic writing), as also reported in Curry and Lillis (Citation2010).

ARNs also contributed to repertoire expansion through opportunities for academic literacy support in Chinese and English. This was of particular importance to participants who had completed their studies abroad, as they received no institutional support in their endeavors to develop their academic literacy skills in Chinese, despite the value of these for career progression (Zheng & Guo, Citation2019). As documented previously, academics in language-related fields both require and value multilingual competence, and even receptive competence in particular languages can facilitate forms of scholarly collaboration (Schluer, Citation2014; Tao et al., Citation2019).

The researcher agency exercised in ARN management carried strong sociocultural features. Within the context of China, engagement in ARNs was viewed from a long-term perspective and this sustainability was underpinned by expectations of reciprocity, known as guanxi, and the long-term circulation of favors, known as renqing (Zhai, Citation2004, Citation2020). The successful management of one’s relations in ARNs depended on knowledge of, and adherence to, traditional sociocultural practices.

The sociocultural dimension in ARNs is a plausible explanation for certain tactical practices (such as renouncing authorship as a favor to the co-author) that in other contexts are viewed as violations of academic integrity (Curry & Lillis, Citation2010). Whilst the practice of negotiated authorship can be used to benefit network expansion (see, for instance Lowrie & McKnight, Citation2004), in the Chinese cultural context, the practice was primarily viewed as a form of guanxi to maintain harmonious relations. Following de Certeau’s (Citation1984) distinction between strategies and tactics, this tactic-like practice might be regarded as an improvised response to macro-level demands that establish often unreasonable publishing criteria for career progression, without sufficiently taking into account the time and resources required to fulfill these standards.

Although elsewhere strong tension exists between the status of English and that of the local language in research dissemination due to the encroachment of English on national academic culture and local language domain loss (see Al-Bataineh, Citation2021; Buckingham, Citation2014; Clarke, Citation2020; Mustafawi & Shaaban, Citation2019), in the multilingual context of China, more than one local language is promoted for academic purposes. Apart from the nation-wide promotion of academic publishing in Chinese (as reported in Liu & Buckingham, Citation2022b), in the Jilin region Korean-language journals (from the Korean Citation Index) are recognized by institutional recruitment and promotion evaluation committees. The elevated status of Korean is doubtlessly helped by the sophisticated academic culture in the heritage language countries which, as we demonstrate, facilitates research-related networking opportunities for Korean-speaking Chinese academics.

Our study has both theoretical and practical implications. First, our study extended the concepts of networks of practice (NoPs) and individual networks of practice (INoPs) by introducing, and demonstrating the application of, the concept of academic research networks of practice (ARNoPs). Future studies might explore the existence of context-specific variations in this conceptual framework for network analyses. Second, our findings indicate that academics’ engagement in ARNs typically evolves in relation to the amount of time spent co-located with network members. Future research could include a longitudinal dimension in study design to observe the trajectory of professional networks.

An important practical implication for institutions from this study concerns the need to value the transnational academic network resources possessed by scholars who completed their studies abroad to promote disciplinary internationalization. In line with Zheng and Guo (Citation2019), Tao et al. (Citation2019) and Liu and Buckingham (Citation2022b), we also underscore the need for institutions to value more highly publications in professional languages to enable viable and sustainable career pathways for foreign language scholars.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yali Liu

Yali Liu completed an MA in Applied Linguistics at the University of Auckland. She completed a PhD at the same institution on the experience of Chinese lecturers of foreign languages in writing for publication. Her research interests focus on applied sociolinguistics, and academic writing, publishing and pedagogy.

Louisa Buckingham

Louisa Buckingham lectures in Applied Linguistics at the University of Auckland. She previously held lecturing positions in Turkey, Oman and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and has also worked in NGO and government sectors. She has a multidisciplinary academic background, which is evident in her wide-ranging publications.

Notes

1. Guanxi refers to “the concept of drawing on connections in order to secure favors in personal relations…[it] contains implicit mutual obligation, assurance and understanding, and governs Chinese people’s attitudes toward long-term social and business relationships” (Y. Luo, Citation1997, p. 44).

2. We obtained ethics approval for this study (UAHPEC-019260). All participants gave informed written consent.

3. As illustrated in Examples 5–7 in Liu and Buckingham (Citation2022b), four of the six national top universities included in the study did not recognize the publications in LOTE-medium journals that were based in the professional language heritage country as valid research achievements for academic promotion; however, the four provincial universities and the remaining two national top universities recognized these publications, and the university located in Yanbian (an autonomous province) not only recognized the journals based in North and South Korea as core journals, but also developed a supplemental directory for the journals that were not indexed.

References

- Al-Bataineh, A. (2021). Language policy in higher education in the United Arab Emirates: Proficiency, choices and the future of Arabic. Language Policy, 20(2), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-020-09548-y

- Aldieri, L., Kotsemir, M., & Vinci, C. P. (2018). The impact of research collaboration on academic performance: An empirical analysis for some European countries. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 62, 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2017.05.003

- Bardi, M. (2015). Learning the practice of scholarly publication in English–A Romanian perspective. English for Specific Purposes, 37, 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2014.08.002

- Bourdieu, P. (1986/2011). The forms of capital. In I. Szeman & T. Kaposy (Eds.), Cultural theory: An anthology (pp. 81–94). Wiley Blackwell.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer.

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (2001). Knowledge and organization: A social-practice perspective. Organization Science, 12(2), 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.2.198.10116

- Buckingham, L. (2014). Building a career in English: Users of English as an additional language in academia in the Arabian Gulf. TESOL Quarterly, 48(1), 6–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.124

- Burgess, S., Gea-Valor, M. L., Moreno, A. I., & Rey-Rocha, J. (2014). Affordances and constraints on research publication: A comparative study of the language choices of Spanish historians and psychologists. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 14, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2014.01.001

- Burt, R. S. (2005). Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital. Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, D. C. (2020). Language ideologies and the experiences of international students. In M. Kuteeva, K. Kaughold, & N. Hynninen (Eds.), Language perceptions and practices in multilingual universities (pp. 167–192). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Contandriopoulos, D., Duhoux, A., Larouche, C., & Perroux, M. (2016). The impact of a researcher’s structural position on scientific performance: An empirical analysis. PLoS One, 11(8), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161281

- Contandriopoulos, D., Larouche, C., & Duhoux, A. (2018). Evaluating academic research networks. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 33(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.42159

- Curry, M. J., & Lillis, T. (2004). Multilingual scholars and the imperative to publish in English: Negotiating interests, demands, and rewards. TESOL Quarterly, 38(4), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588284

- Curry, M. J., & Lillis, T. M. (2010). Academic research networks: Accessing resources for English-medium publishing. English for Specific Purposes, 29(4), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2010.06.002

- Curry, M. J., & Lillis, T. (2013). A scholar’s guide to getting published in English: Critical choices and practical strategies. Multilingual Matters.

- de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life ( S. F. Randall, Trans.). University of California Press.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? The American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Ferenz, O. (2005). EFL writers’ social networks: Impact on advanced academic literacy development. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 4(4), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2005.07.002

- Gentil, G. (2005). Commitments to academic biliteracy: Case studies of francophone university writers. Written Communication, 22(4), 421–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/074108830528035

- Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/202051

- Hayat, T., Dimitrova, D., & Wellman, B. (2020). The differential impact of network connectedness and size on researchers’ productivity and influence. Information, Communication & Society, 23(5), 701–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1713844

- Hopwood, N. (2010). A sociocultural view of doctoral students’ relationships and agency. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2010.487482

- Hultgren, A. K. (2014). Whose parallellingualism? Overt and covert ideologies in Danish University language policies. Multilingua, 33(1−2), 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-0004

- Hyland, K. L. (2015). Academic publishing: Issues and challenges in the construction of knowledge. Oxford University Press.

- Jahić, A. (2016). Achieving visibility in the international scientific community: Experiences of Bosnian−Herzegovinian scholars presenting and publishing research in English. In L. Buckingham (Ed.), The status of English in Bosnia and Herzegovina (pp. 115–137). Multilingual Matters.

- Kyvik, S., & Reymert, I. (2017). Research collaboration in groups and networks: Differences across academic fields. Scientometrics, 113(2), 951–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2497-5

- Lee, S., & Bozeman, B. (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science, 35(5), 673–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312705052359

- Lee, D. J., Pae, J. H., & Wong, Y. H. (2001). A model of close business relationships in China (guanxi). European Journal of Marketing, 35(1/2), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560110363346

- Li, W., Aste, T., Caccioli, F., & Livan, G. (2019). Early coauthorship with top scientists predicts success in academic careers. Nature Communications, 10(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13130-4

- Liu, Y., & Buckingham, L. (2022a). A critical approach to interviewing academic elites: Access, trust, and power. Field Methods, advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X221114226

- Liu, Y., & Buckingham, L. (2022b). Language choice and academic publishing: A social-ecological perspective on languages other than English. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2080834

- Lowrie, A., & McKnight, P. J. (2004). Arns: A key to enhancing scholarly standing. European Management Journal, 22(4), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2004.06.011

- Luo, Y. (1997). Guanxi: Principles, philosophies, and implications. Human Systems Management, 16, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-1997-16106

- Luo, N., & Hyland, K. (2016). Chinese academics writing for publication: English teachers as text mediators. Journal of Second Language Writing, 33, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2016.06.005

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282.

- Melin, G. (2000). Pragmatism and self-organization: Research collaboration on the individual level. Research Policy, 29(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00031-1

- Mustafawi, E., & Shaaban, K. (2019). Language policies in education in Qatar between 2003 and 2012: From local to global then back to local. Language Policy, 18(2), 209–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-018-9483-5

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2019). Content analysis and thematic analysis. In P. Brough (Ed.), Advanced research methods for applied psychology (pp. 211–223). Routledge.

- Niehaus, E., & O’Meara, K. (2015). Invisible but essential: The role of professional networks in promoting faculty agency in career advancement. Innovative Higher Education, 40(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9302-7

- Schluer, J. (2014). Writing for publication in linguistics: Exploring niches of multilingual publishing among German linguists. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 16, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2014.06.001

- Tao, J., Zhao, K., & Chen, X. (2019). The motivation and professional self of teachers teaching languages other than English in a Chinese university. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 40(7), 633–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1571075

- Vanhonacker, W. R. (2004). Guanxi networks in China. The China Business Review, 31(3), 48–53.

- Wang, J. (2016). Knowledge creation in collaboration networks: Effects of tie configuration. Research Policy, 45(1), 68–80.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Zappa-Hollman, S., & Duff, P. A. (2015). Academic English socialization through individual networks of practice. TESOL Quarterly, 49(2), 333–368. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.188

- Zhai, X. W. (2004). 人情, 面子与权力的再生产 [Reproduction of renqing, mianzi, and power]. Sociological Studies, 5, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.19934/j.cnki.shxyj.2004.05.005

- Zhai, X. W. (2020). 关系向度理论的提出及其应用 [The development and application of relational dimension theory]. Tourism and Hospitality Prospects, 4(1), 1–11. https://lydk.bisu.edu.cn/EN/10.12054/lydk.bisu.138

- Zheng, Y., & Guo, X. (2019). Publishing in and about English: Challenges and opportunities of Chinese multilingual scholars’ language practices in academic publishing. Language Policy, 18(1), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-018-9464-8