ABSTRACT

The network of Cooperative Extension professionals across the United States offers fertile ground for the development of intergenerational partnerships in communities. Cooperative Extension programming prioritizes implementation of evidence-based curricula. This paper provides a reflection of an intergenerational program that adapted evidence-based preschool nutrition education for an intergenerational setting by collaborating with Virginia Cooperative Extension. Specifically, we detail how Cooperative Extension personnel are valuable community partners for implementing evidence-based practices in intergenerational programming via curriculum adaptation. Integrating evidence-based curricula and intergenerational practices can support program sustainability.

Background and rationale

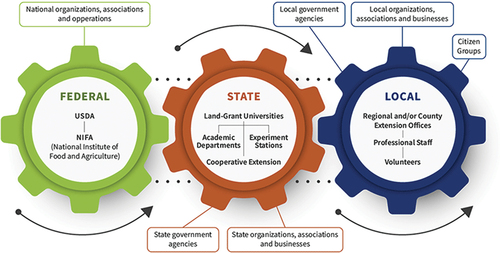

The Cooperative Extension System translates research into action to empower farmers, youth, families, and communities (https://www.nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/how-we-work/extension/cooperative-extension-system). Through partnerships with land-grant universities in the United States, the Cooperative Extension System provides opportunities for evidence-based program development and implementation to address public needs at the local level (See ). Through the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Cooperative Extension educators provide education and foster partnerships to enhance community capacity in or near most of the nation’s approximately 3,000 counties (https://www.nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/how-we-work/extension/cooperative-extension-system). They provide community members with the latest evidence to support healthy families, farms, and communities.

Figure 1. How the cooperative extension system, in partnership with National Institute of Food and Agriculture, translates research into action (image courtesy of USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture).

Extension educators supporting human development rely on evidence-based, practice-informed curricula to provide programs across the lifespan. America’s largest youth development program, 4-H, is one Cooperative Extension program that empowers young people with life skills to become contributing and productive members of society (www.4-h.org). The Master Gardener program (www.mastergardener.extension.org) offers another example of Cooperative Extension programming that trains volunteers with a passion for gardening in all 50 states. The availability of intergenerational Cooperative Extension curricula is limited. Examples include an interviewing program (Pillemer et al., Citation2017), a resource guide of activities to share life experiences (Kaplan et al., Citation2002), a fitness program (Strand et al., Citation2014), and a grandfamilies support program (Fruhauf et al., Citation2022). Our experience suggests other intergenerational programs are offered by Cooperative Extension educators; Extension educators frequently adapt single-generation curricula for intergenerational settings.

The current case report focuses on Food for a Long Life (FFLL), a community-based project that partnered with Cooperative Extension to adapt an evidence-based nutrition program for an intergenerational setting. FFLL, a Children, Youth, and Families at Risk (CYFAR) Sustainable Community Project, aimed to increase healthy food access, knowledge, and consumption using intergenerational strategies. Extension educators collaborated closely with each community organization to develop the intergenerational nutrition program. The programming brought together preschoolers and older adults to participate in shared programming focused on nutrition. Additionally, community sites were provided with a stipend to facilitate their collaboration with the Extension educators. Through the community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) approach (Israel et al., Citation2013), FFLL operated in two communities, one each in Ohio and Virginia. In this paper, we describe the valuable contributions that Virginia Cooperative Extension made to implement the adapted intergenerational nutrition program among two preschools and two adult day service (ADS) centers.

Between September 2017 and March 2020, FFLL partnered with two preschools and two ADS centers to provide nutrition programming. Preschool #1 was paired with ADS #1, and preschool #2 was paired with ADS #2, allowing relationships to develop throughout programming. The preschoolers and their teachers traveled from each preschool to the corresponding ADS center to join the older adults in the activity space. Preschool #1 was near ADS #1, allowing children to walk to their intergenerational sessions, while preschool #2 had access to school buses to reach ADS center #2.

Approximately 50 adults from the two ADS centers and around 60 preschoolers from the two preschools participated in intergenerational sessions each school year. An additional 160 preschoolers engaged in single-generation nutrition programming provided by FFLL each school year. The two intergenerational groups consisted of 10 to 23 participants per session, while single-generation sessions involved 9 to 22 children, depending on the class size. Children at both preschools were aged 3 to 5 years old and in classes ranging in size from nine to 22 children. Adults at the two ADS centers were over 18, with most being over 65. Due to organizational regulations at the ADS centers, adult demographic data could not be collected.

The Extension educators provided nutrition education in the preschool classrooms, letting children become familiar with the educators and the material. Then, the Extension educators would meet the preschool classroom at the ADS center for an intergenerational session. The Extension educators arrived at the ADS center beforehand to prepare the space in a small activity room. They arranged chairs and materials in a circle with indicators for alternating seating of children and adults to encourage intergenerational interaction.

Next, they invited the adults from the larger adult group space to join the FFLL programming. While the adults waited for the preschoolers and their teachers to arrive, the Extension educators prepared ADS participants for the upcoming nutrition activity by describing the target food and outline for the day’s lesson. Once the children arrived, the Extension educators initiated the nutrition lesson by reviewing what the children had learned in their single-generation classroom session through an intergenerational activity, game, tasting, or simple food preparation. The Extension educators prompted intergenerational interaction and discussion throughout the session. The intergenerational and single-generation sessions occurred twice a month, each lasting approximately 45 minutes.

Theory, methodology, and evidence-based intergenerational nutrition programming

Developed to achieve project goals by promoting positive intergroup contact, FFLL was informed by contact theory tenets that include stakeholder support, perceived equal group status of participants, cooperation among participants working toward a common goal (Allport, Citation1954), and friendship (Pettigrew, Citation1998). Evidence associates implementation of these tenets with higher levels of intergenerational interaction (e.g., Jarrott & Lee, Citation2022; Kwong & Yan, Citation2023). We anticipated that bringing preschoolers and older adults together through nutritional programming would support positive intergroup contact and improved nutrition, including access to healthy food.

FFLL’s focus on healthy food access reflected community members’ identification of food insecurity as a social problem requiring attention. With an emphasis on equitable partnership among researchers and community members at every level of inquiry, Israel and colleagues’ (Citation2013) nine CBPAR principles guided the FFLL program implementation (See Jarrott, Cao, et al., Citation2021 for an overview of our application of the CBPAR principles to FFLL). Evidence-based practices in intergenerational programming (Jarrott, Scrivano, et al., Citation2021) informed program implementation, reflecting the strength-based approach of the contact theory tenets and CBPAR principles.

In addition to drawing from a theoretical and methodological orientation, FFLL sought to incorporate evidence-based nutrition programming and intergenerational training. We selected the Together, We Inspire Smart Eating (WISE; Whiteside Mansell & Swindle, Citation2017) nutrition education curriculum because of its focus on preschool age children and design for low-income families using affordable, healthy food. Intergenerational training involved completion of an Intergenerational Best Practices online course through the Extension Foundation Campus (Project TRIP: Transforming Relationships through Intergenerational Programs) that teaches evidence-based intergenerational program implementation practices.

Adapting curriculum for an intergenerational setting

FFLL engaged Virginia Cooperative Extension staff to adapt the WISE preschool nutrition curriculum (Whiteside Mansell & Swindle, Citation2017) for an intergenerational setting (Scrivano et al., Citation2022). To accomplish this, the FFLL team incorporated and reflected upon evidence-based intergenerational practices (Jarrott, Scrivano, et al., Citation2021). In the following section, we map evidence-based intergenerational practices onto the process of adapting a single-generation nutrition curriculum.

Stakeholder support of intergenerational contact

Throughout the CBPAR collaboration, frequent listening sessions and meetings between community partners and the FFLL team highlighted the need to focus on increasing healthy food knowledge, access, and consumption as well as socialization for older adults. Stakeholders included child and ADS directors invested in achieving dual outcomes (nutrition education and intergenerational contact) through a single mode of programming. Community partners included representatives from city food programs, such as coordinators of local food banks and Meals on Wheels, food and nutrition education staff from Cooperative Extension, preschool administrators who were not directly providing programming, and representatives from the United Way.

Prepare staff and participants

The FFLL team completed WISE training to deliver the curriculum in a single-generation preschool setting before adapting the curriculum for an intergenerational setting. The Extension staff leading intergenerational nutrition sessions on the FFLL team also completed the online Intergenerational Best Practices course through Extension before program implementation. The Cooperative Extension educator was key in preparing staff, child, and older adult participants for intergenerational WISE programming. They translated the importance of the intergenerational nutrition program to preschool staff and administrators, focusing on how the program can inform student outcomes. Then, for ADS staff and administrators, they emphasized the social and nutritional aspects of programming for older adults. Consequently, stakeholders understood the potential added value of an intergenerational approach to nutrition education curriculum.

Attend to issues of time

To implement the intergenerational nutrition programming within the routines of the preschools and ADS centers, constant communication was essential. Extension educators maintained the flow of communication with partners and were a valuable resource for understanding issues of time, such as time needed to transport children to the ADS centers and the influence of holidays and vacations on routines.

Incorporate mechanisms of friendship

To build relationships, the same preschool classes regularly met with older adults at the ADS centers, with whom they shared experiences preparing and eating food and their food preferences. Educators used their intergenerational training to facilitate interactions between the participants, some of whom had limited intergenerational experience prior to the FFLL project. For example, discussion prompts were used to encourage intergenerational partners to share information with each other.

Offer something novel

FFLL programming evolved to support different outcomes through shared programming. Preschool administrators wanted a creative approach that incorporated nutrition education while ADS providers wanted an opportunity to discuss nutrition while emphasizing intergenerational interaction. The novel approach of creating an intergenerational nutrition program was attractive to ADS and preschool program stakeholders who realized they could support shared and distinct needs of multiple age groups with shared programming.

Cooperative extension as an essential community partner

In identifying key stakeholders and gaining their support, the FFLL Cooperative Extension educators proved essential in implementing intergenerational, evidence-based practices. Initially, the Cooperative Extension educators concentrated on brokering relationships between centers. They then guided the site through incorporation of the intergenerational evidence-based practices (Jarrott et al., Citation2019) into the nutrition curriculum. Such efforts align with the role of Cooperative Extension in communities to foster partnerships in building community capacity. Its educators are well-positioned to create intergenerational community programs grounded in evidence that reflect community needs and opportunities.

Community programs unable to find intergenerational curricula specific to their goals may find a solution by partnering with Cooperative Extension educators who are a valuable community resource. Extension educators can recruit intergenerational partners and have access to intergenerational practice training through online resources. With access to extensive evidence-based curricula typically designed for a single age group, Extension educators can work with community partners to adapt programming for an intergenerational audience. For example, Extension Master Gardeners and 4-H programming to support skill and relationship development and Farm to School activities (Qu et al., Citation2019), such as Fon du Lac Tribal and Community College’s Leadership through harvest CYFAR program, lends itself to intergenerational adaptations. A STEAM program could partner retired engineers and artists to deliver an intergenerational series with local youth. Extension educators can recruit intergenerational partners and develop programming to reflect participants’ talents, interests, and resources.

Intergenerational programs often end after two years (Hamilton et al., Citation1999); identified barriers to sustainability include lack of administrative and resource support (Canedo-García et al., Citation2017; Jarrott & Lee, Citation2022). Collaborations with Cooperative Extension also face challenges, including the need to sustain positive relationships between community partners and Extension staff, limited communication time due to competing job responsibilities and a mutual reliance on each other to navigate program scheduling. Cooperative Extension offers an avenue to sustainability through brokering relationships for community support as evidenced by the 4-H youth development and Master Gardener programs. Establishing partnerships is a key element of intergenerational program development, and it is a superpower Cooperative Extension professionals possess. Through a partnership with Cooperative Extension educators, FFLL implemented practices grounded in research to support the adaptation of an Extension-approved single-generation nutrition program to create a novel and sustainable intergenerational nutrition program.

Contribution to the field

In this paper we describe implementation of research-informed intergenerational practices by Cooperative Extension educators to support the adaptation of an evidence-based single-generation nutrition program.

We highlight the potential for adapting single-generation curriculum for an intergenerational setting.

We describe the value of partnering with Cooperative Extension educators to adapt programming for an intergenerational setting.

Finally, we advance intergenerational practices grounded in research within the context of adapting curriculum.

These strategies may promote the sustainability of intergenerational programs within community settings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank and recognize the efforts of our community partners Jennifer Wood, Julia Thurman, Tywona Tolbert, Samantha Aaron, and Morgyn Manzer. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Blue Cross NC Institute for Health and Human Services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Canedo-García, A., García-Sánchez, J. N., & Pacheco-Sanz, D. I. (2017). A systematic review of the effectiveness of intergenerational programs. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(OCT), 1882. Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01882

- Fruhauf, C. A., Yancura, L. A., Greenwood‐Junkermeier, H., Riggs, N. R., Fox, A. L., Mendoza, A. N., & Ooki, N. (2022). Lessons from the field. Community‐based participatory research: The important role of university–community partnerships to support grandfamilies. Family Relations, 71(4), 1470–1483. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12672

- Hamilton, G., Brown, S., Alonzo, T., Glover, M., Mersereau, Y., & Willson, P. (1999). Building community for the long term: An intergenerational commitment. The Gerontologist, 39(2), 235–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.2.235

- Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (2013). Introduction to methods for CBPR for health. In B. A. Israel, E. Eng, A. J. Schulz, & E. A. Parker (Eds.), Methods for community-based participatory action research for health (pp. 3–37). Jossey-Bass.

- Jarrott, S. E., Cao, Q., Dabelko-Schoeny, H. I., & Kaiser, M. L. (2021). Developing intergenerational interventions to address food insecurity among pre-school children: A community-based participatory approach. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 16(2), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2019.1640827

- Jarrott, S. E., & Lee, K. (2022). Shared site intergenerational programs: A national profile. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 35(3), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.2024410

- Jarrott, S. E., Scrivano, R. M., Park, C., & Mendoza, A. N. (2021). Implementation of evidence-based practices in intergenerational programming: A scoping review. Research on Aging, 43(7–8), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027521996191

- Jarrott, S. E., Stremmel, A. J., & Naar, J. J. (2019). Practice that transforms intergenerational programs: A model of theory - and evidence-informed principles. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 17(4), 488–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2019.1579154

- Kaplan, M., Goodling, A., Miller, M., Cornell, A., & Hanhardt, L. (2002). Tools and resources for intergenerational action and learning (TRIAL): An intergenerational toolboxes curriculum. Pennsylvania State University College of Agricultural Sciences/Cooperative Extension.

- Kwong, A. N., & Yan, E. C. (2023). The role of quality of face-to-face intergenerational contact in reducing ageism: The perspectives of young people. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 21(1), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2021.1952134

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

- Pillemer, K., Schultz, L., Cope, M., & Graf, S. (2017). Building a community legacy together (BCLT)- an intergenerational program for youth and older adults aimed at promoting a more equitable society. Cornell University.

- Qu, S., Fischer, L., & Rumble, J. (2019). Building bridges between producers and schools: The role of extension in the farm to school program. The Journal of Extension, 57(4), v57–4a4. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.57.04.23

- Scrivano, R. M., Naar, J. J., Jarrott, S. E., & Lobb, J. M. (2022). Extending the together, we inspire smart eating curriculum to intergenerational nutrition education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 8935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158935

- Strand, K. A., Francis, S. L., Margrett, J. A., Franke, W. D., & Peterson, M. J. (2014). Community-based exergaming program increases physical activity and perceived wellness in older adults. Journal of Aging & Physical Activity, 22(3), 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1123/JAPA.2012-0302

- Whiteside Mansell, L., & Swindle, T. M. (2017). Together we inspire smart eating: A preschool curriculum for obesity prevention in low-income families. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49(9), 789–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2017.05.345