Abstract

The image of the mask is a well-known metaphor in law. It exemplifies the legal persona in that it both hides the private sphere and at the same time it enables participation in the public sphere by means of the legal personality of the rights-and-duties-bearing person that can effectuate legal standing. But legal personhood is itself a fiction, because it is a construction of law without which human beings would “merely” be individual persons. This fiction is most explicit in the artificial personality of corporations. Historically, the attribution of personhood by law shows that issues surrounding personhood, identity, and, or in relation to, the body often lead to normative and philosophical contestations. These are important to note in view of disciplinary cooperations of the “Law and” kind on the view that conceptual differences in cooperating fields lead to new Babels rather than interdisciplinary successes.

INTRODUCTION

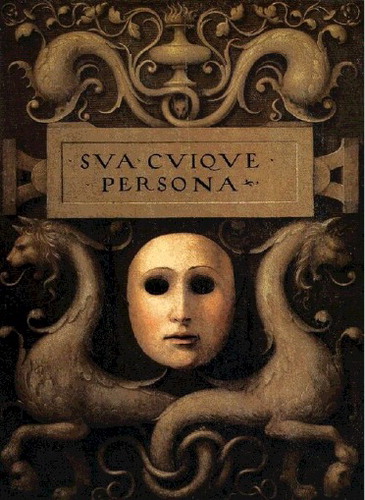

Some years ago when I visited the Pallazo degli Uffizi in Florence, I saw a portrait of a veiled woman by Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio (painted c.1510), with an accompanying panel to cover it. The panel shows a mask with the caption “sua cuique persona,” i.e., to each his own mask ().Footnote1 This enigmatic text prompts the subject of my article. What does “To each his own mask” mean? Whose mask? Which mask? Or should we say “to each his own identity?”

Figure 1. Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Portrait of a Veiled Woman, c.1510. Pallazo degli Uffizi, Florence.

In law, the metaphor of the mask is well known. Exemplifying the legal persona, the mask hides our most private, individual sphere of life and, at the same time, it enables us to participate in the public sphere by giving us a legal personality, i.e., by making us a rights-and-duties-bearing person who can effectuate his or her legal standing.

But legal personhood, while bestowed on the human person at birth in the Western legal systems as we know them, is itself a fiction precisely because it is a creation, i.e., a construction of law without which we would “merely” be individuals, or even “unpersons” in the Orwellian sense, thought to have never existed in terms of the law and obviously without anything resembling a human right.Footnote2 Such individuals would be treated as objects, as was the case with slaves, women,Footnote3 and children in ancient Greece and Rome and even in less ancient times in Western civilization, and as still is the case with animals. In worst-case scenarios, given such lack of formal recognition by law, they could be randomly disposed of, a fate unfortunately shared by those whose formal personhood is simply denied or taken away, as happened, for example, in Nazi Germany.

This fiction of law is most explicit in the artificial personality of corporations, from the medieval concept of the universitas to Citizens United v. FEC 130 S. Ct. 876, 900, 913 (2010), a US constitutional case in which the US Supreme Court held that the prohibition imposed on the basis of the BCRA (Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002) on Citizens United (a nonprofit corporation) to broadcast a film that was highly critical of Hilary Clinton within 30 days of the 2008 primaries was a violation of the First Amendment. To me, the very idea of personhood being assigned to selected “bodies” also draws attention to the liminality of personhood, i.e., to questions concerning the boundaries of what a human being as a person is (and/or the other way around). I will first outline, however briefly, the legal history of the attribution of personhood, highlighting what I suggest remain challenges in our present age in which biotechnological and digital developments seriously question the traditional views on personhood and identity (both in the normative and philosophical senses). In addition, I address some of the issues found to the level of our disciplinary cooperations for purposes of our better understanding of the new challenges on the meta-level of interdisciplinarity, on the view that when fields of knowledge began to diverge in the course of the 18th and 19th centuries and academic disciplines were formed, a divergence on the plane of concepts took place that causes problems of translation between disciplines in contemporary cooperations. By way of tentative conclusion, I discuss the idea of narrated life as a way out of perceived deadlocks pertaining to an exclusively formal-legal view on personhood.

PART I

Legal Personhood: Origins

Point of departure for the historical overview is Roman law, because the codification of Roman law between the second and sixth centuries CE, ordered by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (527–65 CE), hence its name, Codex Justinianus, formed the basis for the development of law in Western Europe once it was rediscovered in Bologna in the 11th century. Roman law's main building blocks were legal personhood, family, property, treaty and tort, with an emphasis on the former. The Corpus Iuris Civilis as it was called, a combination of the Codex, the Digests (codified Roman case law) and the Institutes (educational texts), brought us the tripartite division of the books of private law (civilis for civil or private law as distinguished from canonical laws of the Christian Church) in personae, res, actiones.Footnote4 The division kept its prominence until today. William Blackstone incorporated it in his Commentaries on the Laws of England that was adapted in the British colonies (together with Edward Coke's Institutes) and helped form the basis for American law. American legal formalism as developed by Christopher Langdell in the 19th century, for example, builds on the distinction between actio in rem and actio in personam. John Chipman Gray, unintendedly perhaps, pointed to the contested area of the use of the term person when he wrote,

In books of the Law, as in other books, and in common speech [added emphasis], “person” is often used as meaning a human being, but the technical legal meaning of a “person” is a subject of legal rights and duties.Footnote5

In Germany, the jurist Von Savigny (1779–1861) used the Digests (or Pandectae, hence the name of the movement, Pandektenwissenschaft) to build a closed system of legal concepts. The Napoleonic Code Civil (1804) became the basis for Dutch civil law, the first books of which reflect the original division: persons, both natural and artificial, their goods, and their dealings with them. Roman law, in short, is a factor still to be reckoned with in the cultural landscape of law, whether we like it or not.

The historical root of persona as legal personhood is succinctly brought to our attention by Hannah Arendt (1906–75) in On Revolution:

In its original meaning it signified the mask ancient actors used to wear in a play. (The dramatis personae corresponded to the Greek τα τον δραματος προσώπα.) The mask as such obviously has two functions: it had to hide, or rather to replace, the actor's own face and countenance, but in a way that would make it possible for the voice to sound through. At any rate, it was in this twofold understanding of a mask through which a voice sounds that the word persona became a metaphor and was carried from the language of the theatre into legal terminology. The distinction between a private individual in Rome and a Roman citizen was that the latter had a persona, a legal personality, as we would say; it was as though the law had affixed to him the part he was expected to play on the public scene, with the provision, however, that his own voice would be able to sound through. The point was that “it is not the natural Ego which enters a court of law. It is a right-and-duty-bearing person, created by the law, which appears before the law.” Without his persona, there would be an individual without rights and duties, perhaps a “natural man” – that is, a human being or homo in the original meaning of the word, indicating someone outside the range of the law and the body politic of the citizens, as for instance a slave – but certainly a politically irrelevant being.

[…]

Although the etymological root of persona seems to derive from per-zonare, from the Greek τζώνη, and hence to mean originally “disguise”, one is tempted to believe that the word carried for Latin ears the significance of per-sonare, “to sound through”, whereby in Rome the voice that sounded through the mask was certainly the voice of the ancestors rather than the voice of the individual actor.Footnote6

Two aspects are important to note here. First, the movement of the term persona from its original environment, the theatre, to a new place in law and politics, a movement from literal meaning to metaphoric usage denoting man's social role(s). And following this, secondly, the idea of having roles assigned, i.e., rather than taken on.Footnote7 Since these roles were both social and legal, the connection of law and morality is notable. Young children, women and slaves were not regarded as personae, their status was that of a minor under the guardianship of the pater familias who had complete authority, the so-called patria potestas, over them. Being and having a persona, decided on the basis of “the capacity to enter into obligations in such a way that one could be held legally responsible for fulfilling those obligations,”Footnote8 meant status and privilege in a political sense, minors not being part of the political order. From a moral point of view, the role-aspect was highlighted by Cicero who emphasized that

We must realize also that we are invested by Nature with two characters (i.e. personae in the original), as it were; one of these is universal, arising from the fact of our being all alike endowed with reason and with that superiority which lifts us above the brute. From this all morality and propriety are derived, and upon this depends the rational method of ascertaining our duty. The other character is the one that is assigned to individuals in particular.Footnote9

As far as the former persona is concerned, the distinction between humans and non-human beings that has proved to be detrimental to innovation of legal personhood in our present age is prominent. The latter persona refers to both social and legal roles that may or may not overlap, each with their corresponding duties. To this Cicero adds a third distinction in that the human and his roles are both determined by chance and circumstances, for example, when one is born a male in a noble family, and by choice, in the sense that by executing our free will we decide on, for example, a specific profession or a goal in life.Footnote10

When in the Middle Ages the Christian Church became a source of law by means of its canonical laws, Roman morality was exchanged for doctrines of the soul and immortality. That not only opened up the possibility of inclusion of those formerly excluded on a legal basis – since everybody has a soul – but also the use and meaning of the term persona expanded, not least given the influence of Quintilian's Institutiones on the topic of rhetoric and the writings of the Church Fathers, such as Augustine of Hippo, and Doctors of the Church, such as Saint Thomas Aquinas whose Aristotelian focus on ratio and substance or matter shows in his definition vera persona est rei rationabilis individua substantia.Footnote11 The attention to the persona as physical body was pushed to the background to the benefit of the development of the person as the conflation of the soul and the individual.

This discursive expansion coincided with the institution of universities where the scholastic deductive method of textual exegesis and systematization of knowledge, in law and other fields we now call academic disciplines, took place. And it is precisely the university that benefitted from the development of the concept of personhood. Originally the term for a corporate bodyFootnote12 such as an ecclesiastical collegium (most medieval corporate bodies had a religious of charitative purpose), the universitas could not be excommunicated or be found guilty of a civil or criminal offence and subsequently punished, on the view that the universitas did not have a corporal body and neither did it have a soul or a free will, being only a legal name, nomina sunt juris et non personarum.Footnote13 This doctrine helped Pope Innocent IV (1243–54) who also claimed “cum collegium in causa universitatis fingatur una persona,”Footnote14 maintain the supremacy of the spiritual over secular power.

This bulwark theory, however, was soon demolished. In 1155, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa awarded the schools in Bologna that were devoted to the study of law a special status. These schools were private schools, small societates, each grouped around a magister. Students of different schools began to unite depending on their geographical roots, i.e., citramontanas and ultramontanas, that is, from the Italian side of or from beyond the Alps. Thus two universitates were formed. The students demanded an oath of allegiance from their magistri, organized their relations with the local population, and decided about the jurisdiction for their own internal affairs. Initially, the local authorities tried to prevent this development. When the pope began to support the students, partly for his own profit by introducing the licentia docendi to keep control of those teaching, local authorities in 1270 recognized the universitas as a separate entity, an autonomous corporation with specific privileges for the students such as tax exemption. In short, as alliances of students in Bologna formed a universitas studiosorum, its corporate personality offered protection against both secular and clerical intrusions.Footnote15 Its curriculum covered the whole range of subjects important for a broad education in which boundaries between disciplines were more permeable than in contemporary academia.Footnote16

The development of the corporation and with it the concept of legal personhood accelerated with the growth of commerce throughout Europe, as kings and emperors granted charters. From then on, corporations other than church institutions could also hold property, enter into contracts in their own name, govern themselves by boards, and, if necessary, sue and be sued. From the 17th century onward, the corporation became the legal figure for trading companies such as the Dutch East India Company. Chartered companies began to control international trade. In the United States they also became popular for public projects such as canals and bridges, a topic to which I turn below.Footnote17 The popularity of artificial personhood for practical, commercial reasons is obvious: unlike the human body of the natural person as a legal person, the artificial person does not die, universitas non moritur, as Ernst Kantorowicz explains in his seminal study The King's Two Bodies.Footnote18 The “artificial reason of law,” then, as sir Edward Coke coined it in the early 17th century, produced fictions both to preserve the autonomy of law against the (will of the) absolute sovereign, and to have these fictions reconstruct what is external to law (i.e., as an autonomous discipline) in a conceptual manner to get a grip on the society that law is supposed to order and fulfill its task of ordo ordinans, the ordering order.Footnote19

Legal Personhood: Developments

The theatrical aspect of the persona did not wholly disappear, although it went under the practical legal surface. As Jay Watson points out, in the morality plays of the medieval era the human participants only had allegorical significance, “as opposed to the richer symbolic significance of the persona juris,”Footnote20 i.e., of the later Elizabethan era. As far as the latter is concerned, Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus is the first case in point, featuring the contract as the legal figure per se. The idea of role-playing returns with a vengeance in the lemma persona in the law dictionary conceived by the Dutch philosopher Adriaan Koerbagh which contains the definition: “persona, een mensch, ’t sy man of vrouw; een toneel-speelder, mom-aangesigt.”Footnote21 What is more, the persona as momus is also the mask behind which those who criticize society can hide or retreat from the authorities, both in the legal and the literary senses of the guarantee of anonymity, as often happened in the pamphlet culture in 17th-century Dutch society.Footnote22 To William Shakespeare goes the credit for making the final step toward the truly personal identity of his characters, i.e., an identity other than the group identity that prevailed in the Middle Ages, with their self-knowledge centre stage.Footnote23

The new understanding of the person as an individual permeates the legal theories of the 17th century. With it, in many senses, the main topic of modernity becomes “the riddle of identity.”Footnote24 The convenient idea of a person as one bestowed with a soul and rationality that was predominant as long as the Christian Church's doctrine prevailed, was exchanged for the forensic concept of the persona. The legal figure of the contract became its main representation, as, in the terminology later coined by Henry Maine in the new discipline of anthropology, the development from status to contract was brought to conclusion.Footnote25 The social contract theories of Hugo Grotius (with his emphasis on the appetitus societatis), Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke are obvious examples. To Hobbes, the individual is the building block of society as can also be seen from the frontispiece of Leviathan. What is more, as Hobbes explains in chapter 16 entitled “Of Persons, Authors, and Things Personated,” the individual owns his words and actions and via this concept of ownership he may enter into a contract with others. To Hobbes, in short, everything can be seen in terms of contractual relations:

A Person is he whose words or actions are considered, either as his own or as representing the words or actions of an other man, or of any other thing to whom they are attributed, whether Truly or by Fiction.

When they are considered as his owne, then is he called a Naturall Person: And, when they are considered as representing the words and actions of an other, then is he a Feigned or Artificial person.

The word person is latine; instead whereof the Greeks have πρόσωον, which signifies the Face, as Persona in latine signifies the disguise or outward appearance of a man, counterfeited on the Stage, and sometimes more particularly that part of it, which disguiseth the face, as a Mask or Vizard: And from the Stage, hath been translated to any Representer of speech and action, as well in Tribunalls as Theaters. So that a Person, is the same that an Actor is, both on the Stage and in common Conversation; and to Personate is to Act, or Represent himselfe or an other; and he that acteth another is said to beare his Person, or act in his name […]

Of Persons Artificiall, some have their words and actions Owned by those whom they represent. And then the Person is the Actor; and he that owneth his words and actions is the Author, in which case the Actor acteth by authority. For that which in speaking of goods and possessions is called an Owner and in latine dominus, in Greek κύριος; speaking of Actions is called Author. And as the Right of possession is called Dominion; so the Right of doing any action is called Authority. So that by Authority, is alwayes understood a Right of doing any act, and done by Authority, done by Commission, or License from him whose right it is.Footnote26

The legal view on (artificial) personhood was also much influenced by the idea of man as a machine. This can be traced back philosophically to Descartes’ Traité de l'homme (1648), a treatise on the subject of the mechanical model of man, and a thought experiment on artificial man, on the basis of the Cartesian distinction between res cogitans (that part of the human which thinks) and res extensa (the human's body),Footnote27 with dire consequences not only for the human being but also more specifically for animals.Footnote28 To Locke, then, goes the credit for taking the debate a step further. While he still thought of the person in terms of a forensic concept,Footnote29 the essential attributes of a person in the sense of identity according to Locke are self-consciousness and memory. This brings him to a definition of the person as, “a thinking intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider itself as itself, the same thinking thing in different times and places,” i.e., “person” is equated with “self,” and this leads Locke to the claim that “[E]very man has a property in his own person. […] The labour of his body and the work of his hands we may say are properly his.”Footnote30 So here too the notion of property rights as applied to one's body results in the freedom of contract as the power to undertake obligations.Footnote31 Later on, Immanuel Kant defines a person as “the subject whose actions are susceptible to imputation. Accordingly, moral personality is nothing but the freedom of a rational being under moral laws,” and Kant also claims that “Rationality is a necessary condition for morality. Moral respect is due that without which there could not be any moral respect. Therefore, rational beings must be respected.”Footnote32 What is important to note is that to Kant all rational beings, i.e., not just humans, can be persons. Nevertheless, the Enlightenment conception of a person in the form of entitlement to (fundamental) rights and as the bearer of duties is the outcome of a long process of legal evolution, while the moral and metaphysical idea of rights as innate to human beings connected to it remains problematic when the status of borderline human beings is to be concerned, for the very simple reason that we lack a (legal) definition of the human being agreed upon by all. This is especially problematic when it comes to the construction of “creatures” by means of new technologies.

Theories of Incorporation

The development of the corporation as discussed above occasioned a diversity of theories, culminating in the 19th and early 20th centuries, with respect to the nature and form of the artificial person and its relation to the natural person. They were geared toward legal practice. Given the overarching conference theme, my focus is on those aspects that return with a vengeance in contemporary interdisciplinary discussions of personhood and identity, and I will discuss some exemplary cases.

The crucial point with respect to assigning legal personhood is that the human being is not a person before the law because he is a human being, but because the law calls him or her “person.” The legal subject is a construction to serve human beings in their activities, especially in relation to others. “Put roughly,” as John Dewey wrote, “‘person’ signifies what law makes it signify,” and this leads Dewey to the conclusion that “for the purposes of law the conception of ‘person’ is a legal conception.”Footnote33 The circularity of the argument is obvious, and quite rightly Dewey urges us, although unfortunately in a footnote, not to confound personality with capacity, i.e., say that all legal personality is equally real because the law gives it existence and equally fictitious because it is only the law which gives it existence. In other words, artificial is not synonymous with fictitious. That which is artificial is real and not imaginary, e.g., “an artificial lake is not an imaginary lake,” because artificial as a juridical term contains the root fiction derived from the Latin verb fingere, to make, i.e., not to feign.Footnote34 To paraphrase Marianne Moore, the gardens may be imaginary but the toads are real, and, one may add, with tooth and claw, especially in today's corporate law.

In due course, then, the fiction theory or artificial person theory based on the view that an artificial person such as a corporation is “not really” a person but precisely what it says: artificial, i.e., an artificial being “existing only in contemplation of law,” was replaced by more realistic views on how collectivities can participate as subjects before the law.Footnote35 Dewey should to my mind especially be credited for his aim to seek non-legal factors which have found their way into the discussion of personality of both natural and artificial persons because this makes his work an interesting stepping-stone for interdisciplinary purposes, not least because he draws the attention to the all too often unconsciously accepted (Kantian) postulate that before anything can be a legal person “it must intrinsically posses certain properties, the existence of which is necessary to constitute anything a person.”Footnote36

As Kantian German legal theory would have it, to be a subject is the precondition for being a rights-and-duties-bearing agent. This has led to confusion, for example, in comparative law because the figure of the trust in common law has no counterpart in the civil law tradition, and to conflict when it comes to assigning legal personhood to new entities other than the natural human being or the collectivity. And one look at Wikipedia entries on the topic suffices to see how persistent the problem is.Footnote37 Such seeming contradiction can be solved only by thinking in terms of the conflation of the subject and his attributes, or rather, as Kevin Crotty writes, “In effect, there is no such thing as a ‘pre-legal’ person who then decides to establish law, just as there is no such thing (for example) as a ‘pre-linguistic’ person who consciously decides to speak.”Footnote38 Dewey distinguishes between thinking in terms of essential nature of things or in terms of their consequences (as pragmatists who focus on “what a thing does” prefer). In the latter case, “the right-and-duty bearing unit, or subject, signifies whatever has consequences of a specified kind,”Footnote39 and consequences are to be ascertained on the basis of facts. This consequential reasoning obviously works better when we deal with human rights issues such as the premise of the inviolability of human dignity, questions concerning the attribution of personhood to, for example, trees as Christopher Stone would have it, animals, or human clones, or in cases with respect to the inviolable rights of corporations, as in Citizens United mentioned above.

Interlude: Practical Consequences

Practical consequences, also as far as the internal differentiation of law of private and public law in the United States is concerned that occurred as a result of the growing demand for specialized legal knowledge during and following the Industrial Revolution and the transformative era of technological progress in the 19th century, can be illustrated by a comparison of two cases about the dogmatic place of the corporation: is that in the field of private law or in public law? The first is the Dartmouth College case (1818). The American laws of property were inspired by Locke. The dominant idea was that the first possessor gains a right of ownership by his physical and financial effort to cultivate the soil, to create things out of available materials, and so forth. Dartmouth College, then, was established in 1769, i.e., before American independence, by Eleazar Wheelock together with 11 other men. They did so on the basis of a government charter that made them a corporation, the Trustees of Dartmouth College. This charter gave the founder the right to appoint the next president of the college, but it was stipulated that Wheelock could not do so other than in compliance with the trustees. Wheelock was then succeeded by his son, John, but the trustees removed him given huge differences of opinion. The New Hampshire legislator then changed the original charter so that another institute of higher education could be founded, Dartmouth University presided by John Wheelock. The trustees took their case to court because of this violation of the original relation between trustees and the government. The questio iuris was: “Is Dartmouth College a private corporation with certain privileges and immunities for its trustees or a public corporation subject to the modifications of state legislature?” In other words, can a public body such as the New Hampshire legislator unilaterally change a charter? The Supreme Court decided that a state legislator could not interfere with the contractual relation that is the basis of any charter. In the words of Chief Justice John Marshall:

A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law. Being the mere creature of law, it possesses only those properties which the charter of its creation confers upon it, either expressly, or as incidental to its very existence […] that this is a contract, the obligation of which cannot be impaired, without violating the constitution of the United States. […] The founders of the college contracted, not merely for the perpetual application of the funds which they gave, to the objects for which those funds were given; they contracted also, to secure that application by the constitution of the corporation’Footnote40

Thus, the contractual aspect of the charter prevailed, and the original right of the contractors remained intact. The Lockean concept of property changed, however, in the course of the 19th century.

The case illustrating this development is Charles River Bridge Company v. Warren Bridge Company, 11 Pet. (36 U.S.) 420 (1837),Footnote41 a conflict between two corporations each with a charter to develop a toll bridge. The charter of the Charles River Bridge Company was granted first and since the trustees feared that the second charter of the Warren Bridge Company would have negative economic consequences for them, they challenged the second charter on the ground that it violated their own vested rights, i.e., their exclusive contract with the government. Here the questio iuris was whether or not the state could infringe the vested rights of one corporation by granting a charter to another corporation. The court allowed it and in this way economic development by means of entrepreneurial competition became possible. A parallel development of private law and public law was the result. The doctrine developed in the Dartmouth College case governed the private–public law distinction, and, paradoxically perhaps, it also protected private interests of the kind protected by the Bridge case that showed an instrumental view on private law.Footnote42

But contract and the body, either of the natural person or the corporation, were no quiet spots as the (in)famous Lochner case (Lochner v. New York (198 U.S. 45 (1905)) shows. A New York labor law of 1897 restricted the maximum work hours in bakeries to 60 hours per week, but the Supreme Court deemed such legislation an infringement of the freedom of contract as protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, i.e., the Lockean rights to life, liberty, and property.Footnote43

However, in stark contrast with, but with explicit reference to, the Lochner decision is Muller v. Oregon (208 U.S. 412 (1908)) on the limitation of female employees’ working hours to 10 per day on the paternalistic ground that women are by definition different from men and therefore they need protection more than freedom of contract. That is to say, the risk that women do not know what is good for them is too big and so a labor law may set aside their freedom to accept longer working days. Here, while acknowledging that women have equal contractual and personal rights with men, the Lockean idea that “every man has a property in his own person” is discarded, with an argument that has an unpleasant eugenic foreboding,

That woman's physical structure and the performance of maternal functions place her at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence is obvious. This is especially true when the burdens of motherhood are upon her. Even when they are not, by abundant testimony of the medical fraternity continuance for a long time on her feet at work, repeating this from day to day, tends to injurous effects upon the body, and as healthy mothers are essential to vigourous offspring, the physical wellbeing of woman becomes an object of public interest and care in order to preserve the strength and vigor of the race. Still again, history discloses the fact that woman has always been dependent upon man. […] Differentiated by these matters from the other sex, she is properly placed in a class by herself, and legislation designed for her protection may be sustained, even when like legislation is not necessary for men and could not be sustained.Footnote44

Ironically, this goes to show that attention to female bodily characteristics introduced inequality as far as the idea of legal personhood as originally connected to the figure of the contract is concerned, and all for the benefit of women.Footnote45

The devastating consequences of a language of concepts can be seen in cases with respect to those other human beings who were deemed inferior to “men”: slaves. Dred Scott v. Sanford (19 How. (60 U.S.) 393, 1857)Footnote46 is the landmark case on the classification of people of color as non-entities in law on the basis of what Justice Taney defined as the single question in this case:

Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen? One of which rights is the privilege of suing in a court of the United States in the cases specified in the Constitution.

His answer was negative, on the view that when the Constitution was drafted, its framers intended to exclude the class of people to which Scott belonged as

a subordinate and inferior class of beings, who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the government might grant them.

Taney's reference to the framers’ intention is an example of a hermeneutics of exclusion.Footnote47 Or, as Rhino has it in Margaret Atwood's recent novel MaddAddam (2013), “Who cares what we call them. […] So long as it's not people.”Footnote48 In the 1859 case of the United States v. Amy, a slave-girl against whom a criminal charge was brought (24 F.Cas. 792), however, the prosecutor said to the judges: “I cannot prove more plainly that the prisoner is a person, a natural person, at least, than to ask your honors to look at her. There she is.”Footnote49 This statement would seem to recognize the girl's humanity and personhood. The prosecutor then ironically argued that while the girl had no legal standing, she could nevertheless be the subject of a criminal charge.Footnote50

PART II

Flaps and Patches”Footnote51

On the basis of the above, I suggest three topics for our ongoing discussion of legal bodies on the plane of interdisciplinary studies that are important both separately and in their interconnections, as far research on the history of ideas is concerned and in view of contemporary technological developments. These are the concept of the free will as the criterion for assigning legal personhood, the very idea of the legal fiction as a linguistic issue concerning the conceptual differences between “artificial” and “imaginary,” and last but not least, the epistemological distinction between subject and object. The latter topic is obviously closely related to, first, the distinction between the legal person and the human person as both body and identity, and, second, on the meta-level, the question after position of disciplines on the disciplinary spectrum, i.e., firmly rooted in the natural sciences paradigm (in- or excluding the social sciences), or belonging to the humanities (again, in- or excluding the social sciences).

To start with the second, what should be kept in mind is that the process of the differentiation of “knowledge” into separate academic disciplines is a process that culminated in the late 19th century and the field of law is a prime example in that a differentiation of law itself took place as economics, sociology, and anthropology left the mother discipline.Footnote52 Each discipline developed its own professional language and methodology, and with differences in outlook and differences in objectives, concepts that fields had originally shared, began to diverge.Footnote53 With the rise of scientific positivism, the Cartesian analytical methodology of the Discours de la Méthode, insisting on its own monistic character as does Hobbesian methodological individualism, triumphed. Thus clarity and certainty, ideally at least, collapsed, both as the general aim of the quest for human knowledge and as the litmus test for ascertaining the scientific underpinnings of any field. In short, the struggle to promote the methodology and unitary model of knowledge of the natural sciences for all disciplines founded in the rationalism and empiricism of the late 16th and 17th centuries came to its logical conclusion.Footnote54

The discussion on the free will as criterion for being a person and a legal person at that is an insightful illustration of this development. It is immediately connected to concepts such as guilt and culpability, and the position taken on the subject has consequences for our views on retribution and the forms it should take, e.g., by incarceration of “the body.” So Dewey was right that the development of concepts such as intent is illustrative of “the history of religion, morals and psychology,” or rather, “the intellectual and scientific history of western Europe is reflected in the changing fortunes of the meanings of ‘person’ and ‘personality’ […].”Footnote55

In law, the concept of the free will is the product of a long development. Its foundation is the combined classical-philosophical view of the will as an ability in the sense of an attribute of the soul, and of religious views ranging from St. Augustine to John Calvin who as champions of predestination as far as the afterlife is concerned also thought in terms of the free will to do the right and abstain from what is wrong (both the mala per se (such as murder) and the mala prohibita what law prohibits).

In the Age of Enlightenment, the topic becomes acute as can be seen from the entries in the Dictionnaires of the French philosophers Pierre Bayle and Voltaire. To Bayle, who was based in Rotterdam, the subjective philosophical concept of the liberum arbitrium indifferentiae is the key: having a free will means that man, for example, is free to decide to go either left or right, even if there is no specific reason to do either. In other words, one has freedom to act if one is, simply speaking able to do whatever one decides.Footnote56 As Voltaire put it succinctly in his Dictionnaire philosophique, “Vous êtes libre de faire, quand vous avez le pouvoir de faire.”Footnote57 Freedom of the will is when one is free in one's decision to act at all. This is the precursor and precondition of the freedom to act in that it presupposes the mental ability to decide whether or not to do this, that or the other.

For lawyers, the interesting question is what it means that a decision is free. That is to say, what are the necessary and sufficient conditions that enable such a decision, and what are the consequences. These are obviously essential questions too when dealing with the topic of the relation between subject and object. From a philosophical point of view, the Cartesian ontological dualism of mind and matter is a necessary presupposition if one wants to assert the working of the free will and the freedom of human agency as contrasted to an all-encompassing determinism. Even though Kant had already discussed guilt and punishment in his Metaphysics of Morals (1797) in the context of what would nowadays be called diminished responsibility on the basis of a psychiatric diagnosis,Footnote58 the view of absolute indeterminism with no restrictions on the individual's free will, i.e., not even by his own innate characteristics and/or restrictions, bodily and otherwise, remained dominant.

It was not until the further development of such empirical sciences as craniology, physiognomy, and anthropometryFootnote59 that it became seriously challenged in the course of the 19th century. With the rise of the new field of criminal anthropology, crime came to be viewed as the product of measurable causes that existed (more or less) independently of a person's free will. In criminal law, the new direction taken on this basis was then founded on the argument that punishment must fit the individual criminal, and, on the claim that there are criminal types whose behavior is determined rather than chosen, that treatment rather than punishment may be appropriate in specific cases.

The conflict between indeterminism and determinism in essence comes down to this: the indeterminist presupposes volition per se, and reproaches the determinist for denying the option of attributing the criminal act to the individual. The determinist takes the indeterminist to task for his inability to give reasons for his actions, i.e., other than “I wanted it because I wanted it.” This is the philosophical stalemate of the tertium non datur and, with that, the ontological and methodological problem of those fields of knowledge that take the human as both subject and object of inquiry, and with it the debate on their disciplinary positions on either the explanatory spectrum of the natural sciences or that of the humanities aimed at understanding, rather than explaining, human actions. It is the root of the “Two Cultures” argument of the 1960s when C. P. Snow and F. R. Leavis collided on the topic of the value of the humanities, a fierce argument that contributed to the rise of interdisciplinary studies in the past four decades and has not diminished since.

The deterministic view as espoused by the modern school of criminal law thought of human volition as the combined product of both internal causes, such as the individual's character, and external causes, such as societal circumstances. Where the classical school linked volition to powers of reason and judgment, the deterministic school dealt with questions whether disturbances of the intellectual powers or a mental disease could provide extenuating factors, both with respect to punishment and psychiatric treatment of a defendant.Footnote60

One Dutch determinist, Hamon, concluded that volition is a metaphysical fad, a sophism to be denied by criminologists who necessarily have to accept that criminals could not be held accountable, on the view that positivistic natural sciences have proved that everything is, in one way or another, “determined.”Footnote61 He argued that the only basis for indeterminism is that man is aware of the fact that he has a will, but that is not enough because being conscious of something is not evidence of its existence. Or rather, consciousness and free will can themselves be the determined product of the human brain and its workings, because, as Locke had already argued previously, we do not know the causes that determine our thoughts and actions. This point was well ahead of its times and it was not until 20th-century advancements in neurobiology that its value was accepted.Footnote62 To get out of the stalemate, the topic of (ab)normality was introduced. The supposedly normal person could be punished in the traditional ways; by equating insanity with a lack of accountability (and again in an either/or dichotomy) other remedies in the form of measures could be introduced.

At the end of the 19th century, psychiatrists in the Netherlands became involved as experts in the legislative process concerning the development of the entrustment order as a legal figure.Footnote63 They heavily criticized the legal usage of such terms as “intellectual powers” and “mental faculties.” To them, the legislator should refrain from entering the scientific debate on the influence of the mind on the body and its actions.Footnote64 As Robert Musil brilliantly voiced the problem in his Man without Qualities, set in 1913, what matters is “this ‘I’– the whole body, the soul, the will, the central and entire person as legally distinguished from all others” and “Since a person's liability to punishment is the quality that elevates him to the status of a moral being in the first place, it is understandable that the pillars of the law grimly hang on to it.”Footnote65 So the clash of the empirical behavioral sciences and law on the issue of the free will as found in the debate on the criminal liability of those who lack the capacity either to appreciate the wrongfulness of their conduct or to conform to what the law requires posits the question of the (in)translatability of discourses in interdisciplinary movements in law and other domains. Law's predisposition to seek retribution and deterrence by means of afflicting punishment is in sharp contrast to psychiatry and psychology's main aims to treat the patient and restore his mental health. When in the setting of disciplinary cooperation the ends, means, and methodologies differ, this cannot but lead to tension between the disciplines involved. As a sitting judge, I encounter the problems of differences in conceptual cultures in practice: those of crime statistics when compared with the individual defendant, those of treatment versus punishment, those of economic preferences versus the value of the rule of law in democratic societies, etc.

Scientific developments and new technologies also demand the legal professional's continued attention to human rights and human dignity. To give just a few examples, how are we to deal with (physical or mental) disabilities if biometric features are used as reference for the identification of the legal norm which is “the average person”?Footnote66 How are we to deal with the right not to incriminate oneself as found in Article 6 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (fair trial) when unlawful intrusions in people's lives may be guarded, but bodily materials such as DNA, blood or urine samples, and fingerprints are easily and lawfully taken from defendants, independent of the individual's free will?Footnote67 What is more, both the technological decomposition and commodification of the body into its separate parts,Footnote68 as well as technological enhancements of the body via genetic engineering or xenotransplantation, force us to rethink the legal fiction of the subject. The same goes for the issue of gender identity, or as the French first coined it, “sexe psychologique,” when we note that transsexuality in France at least was classified as a mental illness until 2010, for it recalls the 19th-century use of the concept of personality disease as discussed above.Footnote69 This demands of the humanities as instruments of self-exploration to reconsider their basic question after the nature of the human as both object and subject of inquiry. For example, can new constructs such as clones (to date only existing in the non-human animal form such as the sheep Dolly (mentioned in note 28) or cyborgs be endowed with rights that presume the capacity to bind oneself in law and enter into obligations?Footnote70 And as George Annas rightly asks, “Can universal human rights and democracy, grounded on human dignity, survive genetic engineering?” and “If human rights and human dignity depend on our human nature, can we change our ‘humanness’ without undermining our dignity and our rights?”Footnote71

New technologies result in the implosion of the legal subject as we knew it so that the legal subject and the human, natural person, conceptually different though they are, no longer necessarily coincide. We are used to speaking in legal terms such as privacy, or civil and human rights, but this presupposes a persona that may no longer exist in the same form as when these terms first developed.Footnote72 It also complicates the old question concerning the very idea of human rights as rights that we have simply because we are human, in contradistinction to legal personhood as a construct that makes us a person before the law.

It would seem that the linguistic issue of the fiction as artificial or imaginary is hard to do away with, and as Anthony Amsterdam and Jerome Bruner pointed out, it is not at all easy “to understand how legal categories come into being and are used,” because both typicality or commonness, similarity, and iconicity play a part in the process.Footnote73 Our eradicable tendency to anthropomorphize is not helpful either, though the legal paradigm of personhood obviously has long had its focus on members of our own species.Footnote74 To give just one example from the field of psychology. In his discussion of a grammatical investigation of “person” and “personhood,” Michael Tissaw asks in which way categories and concepts can inform empirical theories on the subject. He refers to Peter Strawson's view that “it is easier to understand how we can see each other, and ourselves, as persons, if we think first of the fact that we act, and act on each other, and act in accordance with a common human nature,” and addresses the source of philosophical confusion that “[W]e use ‘person’ in connection with physical features and sometimes substitute it with ‘body’ […],” or, put differently following Peter Hacker, “‘person’ is conceptually parasitic on ‘human being.’”Footnote75 In the legal setting of the artificiality of the legal subject, this is very difficult to translate and thus such arguments are a source of interdisciplinary confusion.

But, to paraphrase the prosecutor in United States v. Amy discussed above, “There they are.” From as-yet-imagined human look-alike clones of the film The Invasion of the Body Snatchers to the creatures that people Atwood's fictional world of the MaddAddam trilogy (Oryx and Crake, 2003; The Year of the Flood, 2009; and MaddAddam, 2013),Footnote76 and the computer as an object of love without a human body in Spike Jonze's recent film Her (2013), an object bought by the protagonist Theodore Twombly on the basis of the advertisement “It's not just an operating system, it's a consciousness,”Footnote77 on all fronts the question would seem that of personhood as artificiality in relation to personhood and personality as authenticity. It should be noted that Lawrence Solum already asked after the legal status of artificial intelligence in the early 1990s, and that this is not at all unrealistic given the traditional Kantian notion of personhood with its focus on reasoning skills and autonomy as the criteria for assigning personhood.Footnote78

The point is even more acute today, both on the plane of law where the idea of corporations as devices for the sole purpose of financial structuring, i.e., without a persona component and people, is challenged by companies such as Google and Facebook that proclaim to have a social “mission,”Footnote79 and by path-breaking technological developments such as digital representations of the human described as “Digital-Me.” The latter is a technological device (for now, an imagined blueprint, but with huge potential in the near future) that is a human person’s digital replica. It can be programmed to perform that person's tasks, thus serving as a kind of personal assistant. It can, for example, impersonate its owner when he or she does not want to be disturbed. And when it does, it takes its owner's decisions independently, or rather, as if it were its owner. So the topic of the free will once more returns with a vengeance. It also “knows” or “recognizes” situations in which it is necessary to “switch on” the real Me. So the question whether it has “consciousness” comes to the fore.Footnote80

“To Thine Own Self Be True?” The New Orlandos in Law and the Humanities

The examples mentioned above go to show that the original questions return, e.g., is a human being a person, or is it a mind with a bodily extension? Will it remain a material object per se or will it also develop a parallel a virtual–digital representation? Or, when we think in terms of commodification, do we have, i.e., own our bodies, or are we our bodies?Footnote81 The epistemological distinction between subject and object is as eradicable as it is closely connected to the distinction between the legal person and the (human, not so human) person as both body and identity. To date, what counts in law is still the subject as an independent unit with rights and duties. That is the fiction of legal construction that we all have agreed upon, at least so far. But new technologies add to the fictions of the self in unprecedented ways, and, with that, to the problem of human understanding of (legal) personhood as incorporation and embodiment has become a contested area. As Stephen Toulmin wrote, “Man knows, and he is also conscious that he knows,” and this makes epistemology the area of interdisciplinary enquiry in the humanities, contrasting understanding human action to explaining it, in conformity with the paradigms developed in the natural sciences.Footnote82 So the question we have to ask is not only whether we dominate technology or technology dominates us, but also, with the Cartesian dichotomy of the mind as distinct from the body always hovering in the background, whether the unitary concept of legal personhood should not be replaced by “To each his own mask.”Footnote83

As far as our interdisciplinary cooperations are concerned, I would suggest that following the legal principle of audi et alteram partem, hear the other side, law needs the humanities in order to invite conceptual and methodological challenges. There are good reasons for doing so. The legal and ethical focus for a definition of personhood is still on sentience or cognitive traits (with or without the possession of body parts, as in the case of corporations). At the same time, however, the assumption remains that all human bodies that are capable of independent integrated functioning as biological organisms are persons. This calls for more detailed attention to such emphasis on organic (rather than legal or civic) independence as natural persons remain looked upon through the prism of their being biological beings, on the view that the legal tradition always reflects the normative elements of a culture. What is more, the very idea of there being bodily characteristics (such as DNA) independent of the volition of the person thus formed is under pressure by developments in genetic engineering. And the question where the “I” as opposed to “my” brain is to be found is still undecided, although modern neuroscience has it otherwise. Digital technologies can help construct identities, and that includes false identities. As the legal persona and the human person diverge, the point raised by Joel Garreau is acute, “The law is based on the Enlightenment principle that we hold a human nature in common. Increasingly, the question is whether this stills exists.”Footnote84 New technologies influence the construction of the human, literally and figuratively, since human thought too changes, as “we” became post-human as Katherine Hayles already suggested that we did.Footnote85

This calls for methodological interdisciplinary attention to personhood and identity. To be a person in law, does one have to have subjective consciousness? Does one have to be emotive or morally cognizant? Can a person only be a human being as we think we know ourselves? Physically as well as metaphysically, a human person still denotes a thing in the sense of an individual that occupies space and exists for a period of time, with a certain amount of self-sufficiency, and a form of identity. The latter in the sense of one's experience of oneself as something distinctly unique is characteristic of modernity,Footnote86 as Charles Taylor elaborated upon the Sources of the Self. That ties in with the evolution from status to contract in law, for which development legal personhood is crucial. John Finnis offers a methodological contribution to our topic. He wrote, “Questions about identity are questions about what some object of attention and inquiry is and whether it is the same as, or different from, another object of attention and inquiry,” i.e., the subject–object problem in essence.Footnote87 To Finnis, the human person's quidditas, i.e., “what-it-is includes being a who-(s)he-is,”Footnote88 and he connects it to Aquinas’ (implicit) commentary on Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics that consists of four kinds of explanations of reality that are “instantiated paradigmatically in the human person.”Footnote89 The first kind of order is nature as existing independent of the person; the second order is that of human consciousness,Footnote90 the third order is “that which is anticipated and shaped in deliberation” and this includes “one's personal identity both as self-determining and as self-determined. […] What counts is what one becomes in choosing what one chooses.”Footnote91 The fourth order is that of “culture, or mastery over materials (in the broadest sense of material) – every kind of techne,” or what we would call technology in the broad sense.Footnote92

With this in mind, I suggest that Paul Ricoeur's distinction between one's ipse identity and one's idem identity is of great methodological importance for persona and identity as legal constructs. This distinction, made in Oneself as AnotherFootnote93 is not only a contribution to moral philosophy on the subject of human relations, but also is applied by Ricoeur to law and justice in The Just.Footnote94 What matters to me here, however, given my interest in the field of law and literature, or more broadly, law and the humanities, is his later elaboration on the plane of narrative, because as Ricoeur claims in The Course of Recognition, the important thing for the human is learning to “narrate oneself.”Footnote95 This, I suggest, opens up a possibility to connect the legal persona to the contemporary “varieties” of identity that technology now facilitates.

With the concept of idem Ricoeur points to the way in which the other perceives me, for example, as a legal subject when the situation is legal, but also to the correspondence between who we say we are and our bodily evidence or biological, genetic codes in the form of DNA, fingerprints, physiognomy, voice, gait, as well as stable, acquired habits, and the specific but accidental marks by which the individual person is recognized (such as a scar, as in the example of Ulysses that Ricoeur gives).Footnote96 With ipse Ricoeur denotes the way one perceives oneself in the course of a lifetime's development, i.e., ipse as identity in the sense of human authenticity and uniqueness. In the sense that ipseity is reflexive selfhood,Footnote97 a hermeneutics of selfhood is required, connecting idem and ipse.

Such hermeneutics would include the following features, first, taking into account the capacities to be found in the mode of the “I can” (i.e. the who), secondly, “The object-side of experiences considered from the point of view of the capacities employed” (i.e., the what and the how), and thirdly, “in order to give a reflexive value to the self […] the dialectic between identity and otherness.”Footnote98

To Ricoeur, personal identity is tied to the act of narrating, both in the sense of being able to narrate and being able to narrate oneself, “in the reflexive form of talking about oneself narratively [se raconter] this personal identity is projected as a narrative identity.”Footnote99 This ties in with “law and narrative” approaches that focus on the individual's ability to make him- or herself be heard in a court of law, or, as James Boyd White consistently argues, the ability to tell one's story and be heard,Footnote100 on the view that success in law depends on being able to voice suffering, wrongdoings, rights and their abuses, and so on. In the sense that the individual is “him- or herself emplotted,”Footnote101 the problem of the temporal dimension of the self throughout the individual's life (and with it, its different ipseities, i.e., in the seven ages of man, as Shakespeare has it) and of his or her actions can be solved if we consider that “the personal identity, […] as enduring over time, can be defined as a narrative identity, at the intersection of the coherence conferred by emplotment and the discordance arising from the peripeteia within the narrated action.”Footnote102 The latter is obviously most acute in legal settings on the view that legal conflicts arise when expectations about what should have happened are thwarted by realities. Put differently, the “narrative identity” approach is a tool to bridge gaps between the idem and ipse, for while the idem stands for the more immutable kind of identity, its connection to the ipse’s changing identity throughout a life time takes place by means of narrative, thus connecting (biological) sameness to selfhood.Footnote103

As a heuristic tool, it is eminently suited when dealing with topics in law as varied as those who are unable to give informed consent because of their mental disabilities (think also of the effects of dementia),Footnote104 to assigning personhood to “engineered” or “enhanced” human beings (whether they can “narrate themselves” or their lives need being narrated by others, an important task for advocates), and to issues of privacy as well as other legal consequences of the distinction between the private and the public realm, and, not to forget, the topic of law's underlying ideologies as noted in feminist legal studies and gay-legal or queer studies.Footnote105

In short, if a being is able to narrate its ipse identity more adequately, this can enhance its possibilities to achieve fully if so desired the personhood of the idem kind that is legal personhood, and, with that, the rights-and-duties-bearing consequences. Or, if the attribution of legal personhood itself is not the main issue, the “narrative identity” approach can help illustrate the everyday-life specifics of a being's ipse identity that color the circumstances of the case, for example, when in a divorce case a dispute on rights along the conceptual lines of legal personhood only, would lead to unjust results. After all, what matters for success in law is also mutual recognition.

On the meta-level of theorizing, it urges us to take advantage of as many perspectives, or disciplinary narratives, as are available, not least for our mutual illumination on the plane of concepts. To the literary theorist the terms “narrative” and “story” are not interchangeable, whereas most psychological literature on the topic does not problematize the distinction. The same goes, as noted above, for the use of person(hood) between legal scholars and those working in the behavioral sciences and the humanities. If the self's narrative is culturally and contextually situated, so are our disciplinary narratives. They suffer the consequences on the interdisciplinary level if they are inattentive to the conceptual and/or grand narratives that guide and inform them.Footnote106

I started with an enigmatic picture. I end with another. That of the Baker of Eekloo, a topos found in 17th-century Dutch and Flemish folktales and iconography ().

Figure 2. Cornelis van Dalem and Jan van Wechelen, The Baker of Eeklo, 1530–73. Flanders. Amsterdam, collection of the Rijksmuseum, currently on loan to the Muiderslot.

If one was not happy with one's persona, one could go to the baker of Eekloo where one's head was then taken of and replaced by a newly baked one in order to start a new life. There was, of course, a risk of failure and some ended up with more than they bargained for, e.g., when they proved to be more hot-headed than asked for. The moral of the story was that one should be satisfied with the identity one has, the person that one is. To me, it offers a sobering thought in that it suggests that there is only so much that can be done with legal personhood.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeanne Gaakeer

Jeanne Gaakeer is Endowed Professor of Legal Theory at Erasmus School of Law, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The focus of her research is on interdisciplinary legal studies and narrative jurisprudence. She serves as a senior justice in the criminal law section of the Appellate Court, The Hague.

Notes

1. The portrait goes by the name of “La Monacha,” “Portrait of a Veiled Woman,” or “Portrait of a Nun.” The caption is taken from Seneca's De beneficiis, II, 17, as cited in Alessandro Cecchi and Antonio Natali, L'officina della maniera (Florence: Marsilio, 1997), 123; and referenced in Liana de Girolami Cheney and Sonia Michelotti Bonetti, “Bronzino's Pygmalion and Galatea: l’antica bella maniera,” Discoveries 24, no. 1 (2007), see http, http://cstl-cla.semo.edu/dreinheimer/discoveries/archives/241/cheney241pf.htm (accessed January, 28 2014). Cf. Seneca, Moral Essays, 10 vols: vol. III, trans. John W. Basore (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975), 82–83: “Adspicienda ergo non minus sua cuique persona est quam eius, de quo iuvando quis cogitat” (It is, then, every man's duty to consider not less his own character than the character of the man to whom he is planning to give assistance). Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio is mentioned favorably in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, available in an unabridged English translation at http://members.efn.org/∼acd/vite/VasariLives.html (accessed January 28, 2014).

2. George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (London: Book Club Associates, 1976), 49.

3. Cf. Aeschylus, Oresteia, Part 3: The Eumenids, ed. and trans. Alan H. Sommerstein (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 3rd Act, 439. Apollo's argument is that Orestes is not guilty of matricide: “The so-called ‘mother’ is not a parent of the child, only the nurse of the newly begotten embryo. The parent is he who mounts.”

4. This division is attributed to the Roman jurist Gaius, 2nd century CE. For extensive discussion of the topics mentioned, see John Maurice Kelly, A Short History of Western Legal Theory (Oxford: Clarendon, 1993); Harold Joseph Berman, Law and Revolution, The formation of the Western Legal Tradition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983); Paul Koschaker, Europa und das römische Recht (Munich: Biederstein, 1947, and subsequent C. H. Beck editions); and Uwe Wesel, Geschichte des Rechts in Europa (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2010).

5. John Chipman Gray, The Nature and Sources of the Law, ed. R. Gray [orig. Columbia University Press, 1909] (New York: Macmillan, 1921), ch. II, sect. 68, 27.

6. Hannah Arendt, On Revolution [1963] (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976),106–07, n. 42, other notes omitted. Cf. Miguel Tamen, “Kinds of Persons, Kinds of Rights, Kinds of Bodies,” Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature 10, no. 1 (1998): 1–32, on the topic of prosopopeia, i.e., the making of a mask, in relation to personification in law.

7. Also, for example, in criminal law, the idea of the offender as “per-sonans” in the social sense, i.e., as a role designated in and by the social order constituted by law, and sounding-through, ideally at least, when heard in court. Cf. in Dutch legal theory J. Remmelink, Luther en het strafrecht (Zwolle: W. E. J. Tjeenk Willink, 1989).

8. Kurt Danziger, “Historical Psychology of Persons: Categories and Practice,” in The Psychology of Personhood, Philosophical, Historical, Social-Developmental, and Narrative Perspectives, ed. Jack Martin and Mark H. Bickhard (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 59–80, at 62.

9. Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Officiis, trans. Walter Miller (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968), book I, xxx, 107, 109.

10. Ibid., book I, xxxii, 115, 117–19; Cf. Danziger, “Historical Psychology of Persons,” 64, on the responsibilities attached by Cicero to the various roles, i.e., conducting oneself as a rational human being, taking into account features of one's own make-up while realizing that being true to oneself means different things for different people, respecting the obligations imposed by social circumstances, and recognizing that with life choices come (other) obligations.

11. Danziger, “Historical Psychology of Persons,” 66. Cf. Daniela Carpi, “Introduction,” in Bioethics and Biolaw through Literature, ed. Daniela Carpi (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011), 1–19, at 3, on prosopon and the definition by Boëtius of the concept of persona, rationalis naturae individua substantia.

12. Corporate from the Latin corpus, body; cf. John Dewey, “The Historic Background of Corporate Legal Personality,” Yale Law Journal 35, no. 6 (1926): 655–73, at 666, n. 15, referring to Gaius's Digests III, 4, 1, that being a universitas or collegium is dependent on an authoritative decision, e.g., via a statute, and, at 658, citing the German theorist Otto von Gierke's Political Theories of the Middle Age, trans. Frederic William Maitland London: C.J. Clay and Sons for Cambridge University Press, 1900), xxvi: “A ‘universitas’ [or corporate body …] is a living organism and a real person, with body and members and a will of its own. Itself can will, itself can act. […] It is a group-person, and its will is a group will.”

13. In full, “quia universitas, sicut est capitulum, populus, gens et hujusmodi, nomina sunt juris et non personarum”; quoted in Otton von Gierke, Das deutsche Genossenschaftsrecht, vol. III (Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlun, 1881), 281.

14. Ibid., 279, n. 102.

15. For this section I draw on materials used in a co-authored book: Jeanne Gaakeer and Marc Loth, Meesterlijk Recht [roughly translated as Masterly Law] (The Hague: Boom, 2001, further editions 2003 and 2005).

16. It comes as no surprise that the emerging profession of those trained in law became an important factor in the struggle for the supremacy of secular power over papal authority. With the increase of the government apparatus, jurists not only helped the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire found their claim to be the true successors of the ancient Roman emperors and take a stand against the popes, thus demarcating secular power, but also provided monarchs with the means to grab power of jurisdiction to the detriment of local feudal courts and their lords. The imperial reward for such good services rendered was a privileged status for jurists.

17. For a more extensive overview, see Margaret M. Blair, “Corporate Personhood and the Corporate Persona,” University of Illinois Law Review 2013, no. 3 (2013): 785–820, at 788ff.

18. Ernst Hartwing Kantorowicz, The King's Two Bodies, A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 302ff. Cf. Tamen, “Kinds of Persons, Kinds of Rights,” 14–15 [Tommy: titel ontbreekt], that the corpus of corporations is not afflicted by bodily corruption or death. The basic juxtaposition of the two bodies in the sense of the physical body of the king and the office or institution of kingship can also be discerned in the tradition of the funeral effigies of kings. In a different, though related, sense, the idea of an idol as a personification as found in the 1925 Idol case brought before the Privy Council, Pramatha Nath Mullick v Pradyamna kumar Mullick (1925) L Rep 5, shows that “The legal concept of the person can be metaphysically neutral”; cited in Ngaire Naffine, Law's Meaning of Life, Philosophy, Religion, Darwin and the Legal Person (Oxford: Hart, 2009), 166.

19. Cf. Robert A. Yelle, “Bentham's Fictions: Canon and Idolatry in the Genealogy of Law,” Law and the Humanities 17, no. 2 (2005): 151–79, at 159, that “‘Fiction’ as a term of art in jurisprudence goes back to classical Roman Law,” referring to Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria 5, no. 10. 95–99, and Henry Maine's Ancient Law where it says that the fictio was a term of pleading, in the sense of a deliberately false statement used for purposes of ascertaining what the dispute was not about. For a sociological elaboration of a comparable fiction in the form of the view proposed by Emile Durkheim that while individuals may be the material objects in which persons are embedded, persons are not inherent in bodily materials but are collective representations that are socially embedded in these materials, see Spencer E. Cahill, “Toward a Sociology of the Person,” Sociological Theory 16, no. 2 (1998): 131–48.

20. Jay Watson, Forensic Fictions, The Lawyer Figure in Faulkner (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), 29.

21. “persona, a human being, either a man or a woman; an actor, a theatrical mask” (author's translation); see A. Koerbagh, ’t Nieuw woorden-boek der regten ofte een vertalinge en uytlegginge van meest alle de Latijnse woorden, en wijse van spreeken, in alle regten en regtsgeleerders boeken en schriften gebruykelijk (Amsterdam: Wed. Jan Hendriksz. Boom, 1664), http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/koer (accessed January 4, 2014).

22. These “authorities” would include literary authorities too; N. Geerdink, “Politics and Aesthetics – Decoding Allegory in Palamedes (1625),” in Joost van den Vondel (1587–1679), Dutch Playwright in the Golden Age, ed. Jan Bloemendal and Frans-Willem Korsten (Leyden: Brill, 2012), 225–48, at 232, on the pamphlet “Den Gereformeerden Momus” (The Reformed Momus) in which the playwright Vondel is taken to task for his critique of the ruler Merits in the play Palamedes. This goes to show that the persona allows one to split up in numerous identities depending on the context.

23. Cf. Iago the “seemer” in the great struggle for identities in Othello, who claims “I am not what I am” (I.1.65).

24. Roy Porter, Flesh in the Age of Reason, The Modern Foundations of Body and Soul (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003), 63.

25. Henry Sumner Maine, Ancient Law, Its Connection with the Early History of Society and Its Relation to Modern Ideas [1861] (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1950). Maine laid bare the connection between types of culture and forms of law. With the now famous phrase from status to contract, he pointed to the fact that the way in which people live together creates the conditions for the legal concepts with which they regulate their society.

26. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, intro. K. Minogue (London: Dent, 1987), 83–84.

27. For the mechanistic concept of “man as a machine,” see also Julien Offray De la Mettrie, L'homme machine (Leyden: Elie Luzac,1748). The distinction between the subject and object is beautifully described by Borges in his poem on his cat, “Beppo” (from The Cipher, Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1981): “The celibate white cat surveys himself/ In the mirror's clear-eyed glass/ Not suspecting that the whiteness facing him/ And those gold eyes that he's not seen before/ In rambling though the house are his own likeness.”

28. The adamic property claim of Genesis 2:20 led to a view on animals as artifacts, or, as John Rose wrote, the idea that “A cat is like a couch: we explain the origin and destiny of cats with the same procedure we use to explain the origin of furniture”; John M. Rose, “‘Nothing of the Origin and Destiny of Cats’; The Remainder of the Logos,” Between the Species 6 (1990): 53–62, at 56. Talking about cats, Henry James in “The Madonna of the Future” (1879) says, “Cats and monkeys, monkeys and cats – all human life is here” (my added emphasis). On the other hand, our naming of cloned animals such as Dolly the sheep, rather than giving them a number, may well be a sign of recognizing their authenticity. Voltaire's answer to the “mechaniste” Descartes who viewed animals as automata (Discourse de la Méthode, discourse V) is clear: those who look upon animals as objects deny the affective relationship that can exist between, for example, dogs and humans; see Voltaire, Dictionnaire philosophique (Geneva: Gabriel Gasset, 1764), s.v. “bêtes”. Rouseau, in Emile, ou de l’éducation (1762), argues that man and animal are alike in having emotion, so that compassion with fellow beings is the main argument for animal rights, comparable with the “can they suffer?” argument of Jeremy Bentham in his An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (London: T. Payne and Sons, 1789). To date the legal arguments with respect to personhood for animals vary from the “an animal is a linguistically deficient human being that needs protection of the law and/by representation,” i.e., an anthropocentric argument grafted on existing legal concepts, to “a non-legal ethics of care” and “an independent right for animals,” i.e., not on the basis of the idea of welfare but as legal status. Christopher Stone was the first to address the question of legal rights for “objects”; Christopher Stone, Should Trees Have Standing? Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects (Los Altos: William Kaufmann, 1974). See also the blog of the Nonhuman Rights Project (NRP), http://lawblog.legalmatch.com/tag/legal-personhood/ (accessed March 1, 2014), on a lawsuit via the Writ of Habeas Corpus to free the chimpanzee Tommy, arguing his recognition as a legal person. For an example that is as hilarious as it is provocative, see Lord Denning's argument in the fictive case of Grenouille v. National Union of Seamen, a satirical law report published during a strike-induced hiatus in the publication of The Times, as quoted in Lord Denning's memoir The Family Story (London: Butterworths, 1981), 219, http://thevoyageout.tumbl.com/ (accessed February 10, 2014), on the questio iuris: “A frog was a person in law and accordingly had the necessary locus standi to bring injunction proceedings before the courts, especially where the respondent was a wicked and irresponsible trade union,” stating “The facts were simple. Mr Grenouille awoke one May morning to find his pond surrounded by pickets belonging to the National Union of Seamen. They were stopping the public from throwing food into the pond. The frog became ill. He was on the way to starvation. The National Association for Freedom, Enterprise, and Self-Reliance took up his case and last week, through counsel, asked a judge to order the union to remove the pickets. The union, in an affidavit to the court, said that the picket was lawful.”

29. Cf. Danziger, “Historical Psychology of Persons,” 61.

30. John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, book II, ch. xxvii, par. 9; ch. v, par. 27; or idem, Two Treatises of Government, par. 27 (in the Second Treatise on Government).

31. To Hegel, by contrast with earlier thought, the legal persona is the product of the double movement of the contract rather than the precondition of contract. Cf. Karl-Heinz Ladeur, Rechtssubjekt und Rechtsstruktur (Giessen: Focus, 1978), for an extensive treatment of Hegelian subject categories.