Witness Blanket is a large-scale, three-dimensional work assembled from almost nine hundred objects sourced from First Nations individuals, groups, churches, government buildings, treatment centers, institutions, and individuals including a small woven basket, a vibrantly patterned sash and a drum set contributed by the Kwikwetlem First Nation (). Conceived and executed by Carey Newman, it was first unveiled to the public in 2014 as a monument to the generations of Aboriginal children removed from their homes and forcibly assimilated into Euro-Canadian society from 1870 to 1996. Incarcerated in church-run “residential schools” funded by the Canadian government, student-inmates were forbidden from speaking their native languages or practicing their native customs. Newman, whose own father endured time in a Residential School, negotiated a contract with the Canadian Museum of Human Rights that conspicuously diverged from typical acquisition agreements. Rather than an instrument enabling a final transfer of ownership rights, the agreement recast acquisition as an ongoing process of caretaking to be renewed at various intervals. The finalization of the agreement through an indigenous ceremony became the first instance that a state-owned enterprise ratified a legal contract through indigenous traditions.Footnote1

Figure 1. Installation view of Witness Blanket, 2013-2014. Wood (cedar), acrylic emulsion ink-jet, acrylic varnish, animal hide, animal tooth, bark, bone, brick, ceramic, composite, fabric, feather, plant fibre, glass, hair, leather, linoleum, melamine, metal, acrylic paint, paper, plaster, plastic, stone. Dimensions variable. Shared stewardship of Carey Newman and the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Photograph by Jessica Sigurdson/CMHR.

The agreement is a step towards a broader conception of law wrought through the process of enmeshment rather than as a delimited set of rules and claims. Witness Blanket is perhaps most convincing as a trust jointly administered by Newman and the Canadian Museum of Human Rights for the benefit of multiple audiences; the donation of objects reads not only as a voluntary surrender of title to property, but also as an act of entrustment.Footnote2 But although the Canadian government formally apologized to former Residential School students in 2008, the words provided insufficient relief. Witness Blanket renews the urgency of this history by virtue of its scale. Twelve meters long, approximately 3.2 meters high and weighing a staggering 1590 kilograms, the work involved hundreds of contributors and will likely include hundreds more as it travels from one venue to another. The physical scale of the work is matched by the scale of its circulation through traveling exhibitions, a book, a documentary, and an elaborate website. All told, Witness Blanket became an indelible presence whose resistance to effacement implicitly condemns a deplorable history of Euroamerican governments regarding treaties with indigenous groups as mere ephemera to be violated or discarded at will. Witness Blanket reads especially clearly as an affective index, one that heightens the quality of attention paid to objects that might otherwise be dismissed, overlooked, or forgotten such as a doll, a broken fixture, or a piece of sporting equipment. Affixed onto tightly fitting pieces of wood that are then inlaid into diamond- or square-shaped frames, the objects are presented as both symbols and evidence of an affective substructure underpinning First Nations legal history. Instead of preconceived form imposed onto passive, human feelings, thoughts and attitudes, law becomes form-giving when it admits how feelings and thoughts take shape through things, even things not usually acknowledged as initially legal in nature.

Witness Blanket stresses how art inhabits the body of law while also reinforcing the integral role law plays in all aspects of art’s creation, reception, and dissemination. What follows is a series of reflections on various aspects of art and law, a complex and vital relationship that includes the physical manifestations of subjective ideas and feelings known as “art” and often treated by “modern” law as property. It also includes, however, the logistics of their conception, execution and circulation. “Art” encompasses the infrastructures formed to extend, but in some cases also limit, the “natural life” of works including conservation practices, reproduction techniques, storage mechanisms, laws that affect their exchange value, and insurance companies that decide when an artwork is too damaged to be sold as such. This issue overlaps with, but also diverges from the legal history of art which in the context of contemporary situations can fruitfully read as an exchange between what artists have in mind for the law and what the law via legislators, jurists, and existing legal histories have in mind for artists. It is kin to, but not twinned with “art law,” a sub-field of legal study and practice mostly concerned with securing various property and economic interests. The remarkable expansion of the art market, particularly for contemporary works during the past thirty years, has seen a correspondingly dramatic rise in the number of articles, books, courses, and law firm practice groups devoted to the subject, particularly in art market hubs like New York and London.

Yet art law scholarship can sometimes appear bent on making artworks conform, or rather, behave, according to existing laws and what those laws assume about what it is art actually does. Many examples of art law scholarship tend to focus on resolving current areas of dispute through policy or legislation recommendations. Conversely, this issue proceeds from an understanding of art and law as both deeply entwined with claims of autonomy. Judicial independence is an example of how society permits law to constitute its own self-regulating domain. Similarly, despite voluminous discussion of art’s imbrication with science, politics, and economics, the belief that art is governed by principles established by its makers or specific to a medium is so intense and steadfast that it becomes a quasi-religious conviction. The shared fixation on preserving their respective autonomies brings art and law together in ways that foreground contradiction, incompatibility, discrepancy and divergence – conditions ascribed to the more compelling examples of contemporary art and how it lives in the world. Authored by an intentionally eclectic array of scholars working in and researching different parts of the world, the articles here examine how law in its various manifestations is problematized by the specific operations of artworks and their enabling apparatuses. They belong to what might be called a legal speculative realism that presumes discontinuity between the actual order of the world and how we impose structure onto the world through human language, thought, customs and norms.

It is not the intention of this issue to press for a projection of art theory into law or vice versa. But if a priority of legal scholarship is to produce “through conversation, a community and a culture of a certain kind,” as James Boyd White proposes, “art and law” aims to redirect the powers of law towards accommodating a plurality of voices rather than privilege those of a self-regulating minority for whom the law is but another means to exclude others from its ranks.Footnote3 Among law and literature’s earliest and most vigorous champions, White reminds us of the precedents set by law and literature for art and law, particularly in the close attention paid to individual works of literature.Footnote4 In like manner, Peter Goodrich inadvertently provides a model for art and law when he observes how law and literature “offers an alternative method for addressing the epistemic question of how we know the diversity of laws, as well as substantive access to the disparate social forms of legal being, of law and society.”Footnote5 Certainly art and law helps expand the role of non-legal discourse.Footnote6 Thinking of whether art too “proffers the possibility of law by other means” raises the bar for thinking about how law projects the study and interpretation of art into the domains of ethics and politics.Footnote7

Keenly shaped by encounters with visual, and increasingly, aural material, art and law especially highlights two general lines of inquiry. One is the role art has in relation to the law, whether it be that of a provocateur, a critic, a mirror, an id, or a conscience. The other line concerns issues raised by the creation, reception, and distribution of art, which can assume the weight and force of law even if unrecognized by legal institutions. Both lines of inquiry suggest how artworks can be venues for thinking about the law outside the contexts within which law is usually made and interpreted.Footnote8

Law is art’s surround. To consider histories of modern and contemporary art without also accounting for the role of law as its uncredited other is to artificially circumscribe historical terrain and willfully narrow the domains of artistic operation. After all, it was through a confrontation with law that members of various avant-gardes acquainted or reacquainted themselves with art.Footnote9 But contemporary art is also a field whose claims to social, political, and economic agency are irrevocably wedded to how artistic identity was – and is – re-actualized through various relationships established between art and law. The prevalence of copyright and freedom of expression as the main pretexts for thinking about the art-law relationship attests to the persistence with which originality and authorship (and their conversion into symbolic and economic worth) are considered so central to art as to be a law onto itself. This unreconstructed emphasis continues despite a prolific literature that argues how and why originality is a myth, one that has more to say about the subjectivity of certain worldviews than about the ontology of a given work.Footnote10 Economic aggregates root art in capitalist jurisdictions, yet there are other spaces besides the market for considering art and law in common. Four are particularly relevant: form, representation, performance, and feeling. Each provides abundant opportunities for thinking about the respective capacities of art and law, including how artworks might operate as something more than legal objects of scrutiny.

If the validity of art and politics relies on the virtues of a given claim, whether on the basis of its logic or affective impact, art and law emphasizes the quality and nature of evidence offered in support of a claim. It has been some time since artworks have been openly discussed as metaphorical witnesses.Footnote11 But recently more attention has been paid to artists whose works actively address how form becomes legally legible representation, the most visible instance being the members of London-based research group Forensic Architecture. Founded in 2010, the group’s multidisciplinary work frequently mobilizes techniques used in architecture to generate evidence in international law cases where admissible evidence can be extremely difficult, if not impossible to source. Among Forensic Architecture’s best known associates is Lawrence Abu-Hamdan, whose 2018 installation work Saydnaya (the missing 19db) recreated the architecture of a Syrian prison using earwitness testimony from survivors who had been kept in extreme conditions of sensory deprivation. Marshalling both cultural theory and his experiences as a prosecutor, Jeremy Pilcher emphasizes Saydnaya (the missing 19db) as a rebuttal against the entrenched faith in words as the primary conduit for representing reality. Listening is sometimes the only means of crafting a durable fact pattern, yet it is often a form of information collection the law is not always willing or equipped to hear despite referring to court proceedings as “hearings.”

The broad question of form connects art and law in numerous ways, not the least of which is the problem of what similarity looks like. For example, a common quandary in copyright cases in common law jurisdictions turns on the definition of “substantial similarity.” What distinguishes a permissible copy from an impermissible one? Addressing museums and libraries, both institutions of cardinal importance for the life of art via research as well as through its display, collection, conservation, and circulation, Winnie Wong approaches this question by asking what is it that distinguishes aesthetic and artistic knowledge from the apparatuses that facilitate and perpetuate what counts as legal knowledge. Her article does not explicitly discuss “the law” as legal practice might comprehend through cases, legislation, and statutes. But it brings to the surface many of the unspoken but rigorously enforced rules structuring how art is defined, perceived, and circulated. In so doing, Wong provocatively contends that gaining real access to the museum and the library requires thinking about both as if one were police, in a courtroom, or in a prison. The domains that most commonly host artworks may lie outside the scope of official legal investigation, but they require attention of a meta-juridical nature.

Form also matters as a heuristic for sifting through different situations. Legal meaning is often produced by the shape and distance of situated elements, while the efficacy of law often turns on the formal configuration of things.Footnote12 Recent literature presumes a Latourian flat ontology that puts art and artifact on the same plane, which I think gains greater purchase if we follow Luis Gómez Romero and Ian Dahlmann in thinking of law not as “the exclusive patrimony of jurisprudents, lawyers and legal officers,” but that which “emerges from and belongs equally to each and every member of the community at large.”Footnote13 Romero and Dahlmann are writing expressly of comics which they define as “a locus of emergence of legal meaning.”Footnote14 To recall their discussion is to remind ourselves how art and law, like other generous-minded bodies of humanistic scholarship, calls us to keep “open for as long as possible” questions about what form is and what it can do.Footnote15 Ensuring openness can take many forms, including deliberate experimentation with academic writing as Wong models in her contribution. It also includes wrestling with description as an endless problem even as we continue to regard it as the initial channel through which perceptions of form become intelligible (and also generatively illegible).

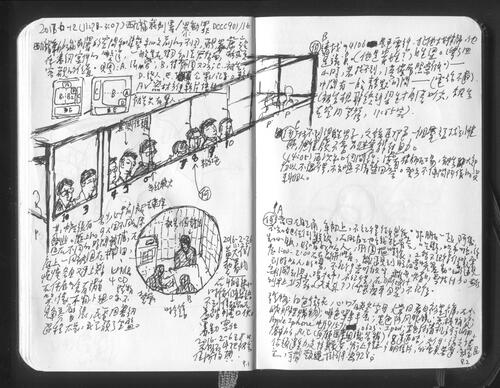

More than a question of choosing which words or theoretical frameworks to use, description entails recognizing the breakdowns that occur when attempting to transcribe sensory perception into words, a struggle animating the sketches of an artist like Pak Sheung Chuen. In 2015, a year after the initial cessation of protests against the undermining of Hong Kong democracy by the People’s Republic of China, Pak attended various court hearings of political cases during which he put to paper images of judges, witnesses, defendants, and lawyers (). A direct violation of official prohibitions against depicting court proceedings while physically in a courtroom, the heavily annotated sketches were accorded artwork status because of their display in a gallery space as well as because of Pak’s professional reputation. But they also read as virtual spaces of actualization whereby the time and labor the artist spent making each sketch as a private citizen is what reaffirmed his commitment to artistic activity. The images allowed Pak “to be immersed into a meditative state of mind” that alleviated the “inner chaos” he felt after the Umbrella Movement ended without achieving any political concessions from the Beijing-backed local government.Footnote16 By occupying space in various Hong Kong courtrooms where Pak converted observation into watchful reflection, the artist was “able to return to the complicated world outside,” that is, to the endless contest between unequal powers known as politics.Footnote17

Figure 2. Pak Sheung Chuen, Drawings from Notebooks, 2017, ink on paper, 14.8 x 21 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

The matter of representation as dissected through a close assessment of visual form assumes heightened importance for scholarship that considers artworks themselves as legal critiques, unresolved hypotheses, ecologies of feeling, and even contiguous worlds affected but not exclusively determined by legal standards. Taking Rafael Cauduro’s 2009 murals for the Supreme Court of the Nation in Mexico City as an exemplary case in point, Desmond Manderson discusses the encounter between visual and legal representation, highlighting in particular Cauduro’s ability to make visible the secrecy of law and its connections with extrajudicial violence. Manderson writes, “the tension between the visible and the secret, the public persona and the back office, the formal and the informal, the acknowledged and the unspoken, lies at the heart of Cauduro’s ethnography of the crimes of modern justice.”

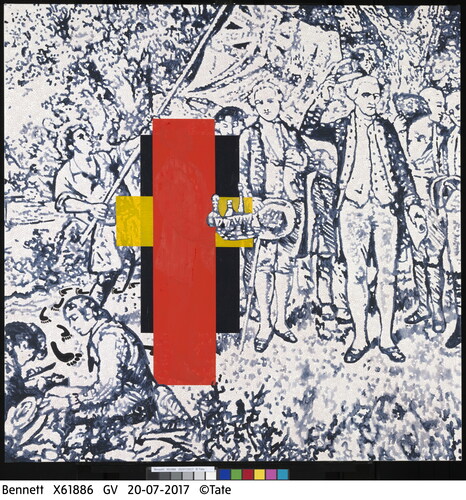

In thinking about the affordances of visual art in relation to law, Manderson has elsewhere read the works of the celebrated Australian artist Gordon Bennett as an instance of how art rectifies the abstracting power of the “western legal perspective” where everything from genocide to discrimination is facilitated by the law’s “tendency to reduce landscapes and people to abstractions, either conformable to standard definitions of property, authority, and law; or if not, rendered invisible.”Footnote18 One of his case studies is Possession Island, a large oil painting from 1991 based on a 19th century etching by Samuel Calvert showing “explorer” Captain James Cook claiming ownership of Australia’s eastern coast in the name of the British Crown (). In Calvert’s work, a Black male attendant stands in the center, wearing European dress and holding a platter replete with decanters and goblets, presumably for a celebratory toast. Despite the centrality of his position in the composition, his role in the narrative is marginal. Possession Island might be, to follow Manderson, an attempt to challenge the “temporal paradox” where certain laws and histories are preemptively declared legitimate, and which over time become difficult to challenge as they indelibly affect “the legal subjectivity of all who live here.”Footnote19

Figure 3. Gordon Bennett, Possession Island (Abstraction), 1991. Oil paint and acrylic paint on canvas, 184.3 x 184.5 cm. Collection: Tate and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, purchased jointly with funds provided by the Qantas Foundation 2016.

I am struck by Bennett’s strategy of appropriating the work of another, not only because of how the act of visibly adapting, incorporating, or otherwise using the work of one artist by another has generated some of the most glaring tensions between art and law but because it loops back to a word in the work’s title: “possession.” I think, for instance, of Cheryl Harris, whose landmark 1993 article “Whiteness as Property” is enjoying new life among younger artists, curators, and art critics grappling with an age shaped by racial reckoning in the U.S. and by accelerated inequality unfolding on a global scale.Footnote20 Observing how whiteness was accorded legal status and thus “converted into an external object of property,” she contends that “whiteness has been characterized, not by an inherent, unifying characteristic, but by the exclusion of others deemed to be ‘not white.’”Footnote21 Although Harris is speaking explicitly of the U.S., the relationship between race and possession is relevant for Bennett whose practice was strongly motivated by a recognition of a transnational Blackness founded on attempts to “exclude, objectify and dehumanize the black body and person.”Footnote22 Works like Bennett’s signal how indigenous and minoritarian claims to life, visibility, and presence increasingly underscores what is that is vital about art and law.

This is not to suggest that visual representation is any less uncertain, or that we can ever be sure as to what a particular image shows or means, a profound doubt that lies at the heart of the art historical project. An art historian who writes frequently for and between academic and general interest audiences, Sarah Lewis has asked what it takes “to work toward representational justice.”Footnote23 Framed in the context of a journal of photography, her question extends well beyond visual recuperation politics, or efforts to reclaim or construct visibility for bodies made invisible by their social, legal, and economic disenfranchisement. Hers is not a question of representational politics but one that asks how representations emerge when imagination intersects with eyewitness account. Asking what it is that motivates lawyers to turn “to the work of culture,” Lewis appears to answer that very question by considering how the work of Carrie Mae Weems calls attention to justice that is both within but also outside the province of law. For this issue Lewis attends to the ground, a term and concept hugely significant for art as well as in law although with very different consequences for the bodies which it supposedly supports. If art and law are bound in part by what Manderson discusses as “the force of walls,” Lewis breaks new “ground” in discussing how justice requires acknowledging both the fault lines and suture points between artistic and legal conceptions of the world.

As histories of contemporary art increasingly read like synecdoches of capitalism’s myriad trajectories, a crucial task is to envision a history of art and law that accounts for the role of affect that elevates fact-finding to truth-telling. This ranks among the most important justifications for lawyers to write about art and for non-lawyers to discuss the effects of law. For although legal scholars like Philip Areeda urged that law borrow from other disciplines insofar that it could “guide our prudential policy choices,” reality is hardly amenable to this kind of narrowly instrumentalist cherry-picking.Footnote24 To fully realize what he described as the potential of legal scholarship by connecting legal practice with different reserves of humanistic knowledge means delving deeper into other forms of knowing.Footnote25 Goodrich, whose discussions of the visual culture of law has helped open another space for thinking about the place of visuality, and by extension, art within the law, has written how “the social spectacle of law” unfolds not only on the page or on the stage of the courtroom, but more commonly through the “chimerical and evanescent public spheres generated on television and the Web.”Footnote26 But as Judith Butler observes, the “law” is “already working before the defendant enters into the courtroom; it takes the form of a regulatory structuring of the field of appearance that establishes who can be seen, heard, and recognized.”Footnote27 Among the relatively limited number of scholars frequently cited in both legal and art-related scholarship, Butler is perhaps best known for her theories of performativity, including the claim that actions and gestures do not merely reflect personal identity but in fact activate new identifications.Footnote28 Performativity emphasizes how the hypothetical or disruptive quality of the situations posed by art allow it to help forge a dialectic space whereby the law - the structure enabling politics to occur – can reflect back upon the legal sensorium.

This is one way to explain how some artworks assume the force of law as measured by political efficacy. Consider “legislative art,” a term coined by the artist Laurie Jo Reynolds in connection with Tamms Year Ten, a collaborative multidisciplinary project involving art historians, lawyers, and cultural works. Begun in 1998, Tamms Year Ten illustrated the motivations of legislative art, or artworks that directly engage existing governmental agencies and processes to effect concrete political change. With her colleagues, Reynolds facilitated a host of actions ranging from political lobbying to close a maximum security prison (the Tamms supermax prison in Illinois) to providing those in solitary confinement visual and psychological respite in the form of a photograph depicting any image they desired.

While Tamms Year Ten succeeded in its main objective of shuttering the prison, it also harvested an unruliness of feeling that dislodged any conceptions of the law as impartial and omniscient.Footnote29 That feeling transforms authority is further borne out by the writing of gallerist, activist, and filmmaker Linda Goode Bryant who recounted how a homeowner convinced a judge to desist from condemning her house. In Bryant’s words, the homeowner “broke” the judge down so that even though “the law itself did not facilitate accommodation,” affective force could persuade judges to seek alternatives to punitive legal remedies.Footnote30 Forensic Architecture founder Eyal Weizman has written how material form may only be “suggestive rather than conclusive” and that “to detect is to transform, and to be transformed is to feel pain.”Footnote31 A telling instance is how outrage has been commonly weaponized by animal rights activists to pressure institutions into infringing upon individual rights of expression or integrity.Footnote32 With the exception of artworks involving children or extreme violence, few bodies of work are guaranteed to cause as much emotional turbulence as artworks including live animals, a premise underpinning my article on live animals in post-1990s art. I claim that artworks make hypotheticals material in ways that exercise the legal imagination, but also force acknowledgement of that which the law can appear to deny or suppress: the primacy of feeling and the cumulative internal struggles provoked among those engaged in legal practice and theory.

Especially eloquent on this count is Yxta Murray, one of the very few legal scholars also active as a contemporary art critic. In her article, Murray explores how juridical assessments of complex affective states might be enriched by thinking about and through artworks. She focuses especially on the challenges of representing the effects of rape, a severely underreported crime whose emotional and psychological toll is often grossly underestimated by those tasked with its investigation. Bearing titles like Super Drunk Bitch, Tracey Emin’s text-based quilts and embroidered works “prosecutes and defends in acts of imaginary justice because the state did not, and would not, and someone had to.”Footnote33 Murray argues how artworks, in addition to functioning as alternative fora for investigation, serve as a vital means of recognition for rape survivors whose refusal to communicate or behave in certain ways constitutes self-defense against a skeptical legal establishment for whom the rape “victim” is legible only according to a circumscribed script. Embodied experience has something to say that diverges from the positivist approach to facticity underwriting many examples of legislation and case law. For this issue, Murray reads Yoko Ono’s performance Cut Piece, a work whose resonance might be stronger now than when it was originally performed in 1964. Made two years before Ono famously met John Lennon through her exhibition in a London gallery, Cut Piece involved audience members cutting pieces of Ono’s clothing as the artist sat alone, unguarded, on a stage. The freedom Ono bestows onto her audience sometimes unleashes aggressive behavior that may not legally qualify as assault or rape, but is sufficiently disturbing as to compel subsequent viewers to voice their objections. Cut Piece therefore catalyzes feminist and intersectional voices seeking to “name and claim sexual aggression as a crime.”

How artworks affect the body that speaks, thinks, and acts explains why performance and performativity have been so generative for legal scholars. Both legal and artistic practice involve extensive negotiations, which is itself a variation of performance. When critical race theorist and antidiscrimination lawyer Charles Lawrence was asked by performance artist Mary Babcock what it meant to think about his work through performance, he wrote how it compelled him to reflect not only on his own use of images including representations of “African Americans as white America has imagined us,” but to remember “the host of characters who join me on the stage each time I speak.”Footnote34 In the rarefied circles of blue-chip contemporary art, contract negotiation can even become performance. Insisting that his instruction-based performance works be sold only through oral agreements that take the form of protracted discussion, the German-Indian artist Tino Seghal stages the act of purchase in front of so many witnesses that the discussion becomes a de facto performance.Footnote35 A title transfer becomes an extension of the performance being sold and the conflict often cited as typical of an institutional purchase of Sehgal’s work reads as a bonus spectacle, included as part of the purchase price.Footnote36 Thus while the market may certainly be one of the very few arenas where parties having diametrically and even violently opposing ideological, religious, and social views can potentially arrive at a mutually satisfactory agreement, it hardly discounts the emotional baggage involved in the agreement process.

A subtheme of this issue is to explore contemporary art through the language of law: for instance, what happens when we consider participation as a subset of consent, positionality as a question of standing, close looking through the legal standard of strict scrutiny or appropriation as a species of takings. Collaborations involving artists and lawyers have offered new platforms for information exchange, knowledge production, and communal action that can include, but also moves beyond protest organization, acts of civil disobedience, and social service provision.Footnote37 Conversely, assumptions about viewing, artistic intention, reception and materiality are thrown into generative disarray when we consider the legal status of creators and audiences. For example, the profound challenges incarcerated artists face in even thinking about what to make is a metonymy for the systemic inequities that automatically accrue the moment one becomes an inmate. Artworks are often a means of survival, traded, gifted, or sold in exchange for money, favors, or access to prohibited materials. Yet, as Nicole Fleetwood discusses through what she describes as carceral aesthetics, artworks enabled prisoners to form and maintain non-transactional or non-coercive relationships.Footnote38

Throwing the innate difficulty of relationships, place, and materiality into stark relief is artworks involving live animals. I speculate on how artworks involving live animals provide new opportunities for human-animal sociality that exceed beyond rehearsed scripts pitting animal autonomy against human sovereignty in an unending cycle of destruction. Reasonableness or appropriateness is a persistent, if unreliable, and in many cases, exclusionary, basis for adjudicating what qualifies as legally permissible behavior. Yet the unreasonable and the inappropriate is often what gives a contemporary work of art its discursive, social, political, and aesthetic value. Far less certain is whether such value outweighs the affective and moral toll incurred by the realization of a work, especially as the primacy of medium in art historical study tends to frame animal participants as materials subject to human intention and consumption. At the same time, I am continuously reminded of how the globalization of contemporary art increasingly requires non-Euroamerican artists to adhere to norms internalized in Euroamerican law, where the dehumanization of certain bodies can sometimes cause animal rights to read as an alibi for racist and xenophobic sentiment. I look at this problem as a matter of description, specifically the task of describing the experiences an artwork may produce. The disruptions an artwork triggers via efforts to translate sensory perception into words constitute a site where law might cultivate its own capacity for sympathy which, in a period marked increasingly by an awareness of extinction, is urgently needed.

Contemporary art offers a wealth of possibilities for aspiring lawyers and judges seeking to familiarize themselves with the constant irrationality that is the rule and not the exception of the world with which they must engage. Reason was never the default of human behavior. Indeed, law’s myopia towards visual and non-textual material is diagnostic of its suffocating attachment to the notion of common sense. Recall, for instance, the axiom “I know it when I see it” that has come to be something of an unlegislated threshold for determining obscene material.Footnote39 Returning, then, to the problems description and representation pose, we might wonder what becomes more noticeable when we see events happening through the law through the lens of art. What insights might be gleaned, for example, if we consider the fictitious Farmington University in Michigan, elaborately crafted by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to apprehend immigration law violators?Footnote40 How much more can be said if we read Mwazulu Diyabanza’s attempt to reclaim from the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris a 19th century funerary post likely taken from present-day Chad or Sudan not as a crime, a protest, a petition for repatriation, or even as a gesture of liberation but as an artistic event?Footnote41

A specialist in human rights law, Luis Gómez Romero addresses the tension between artistic materials and legal materiality in thinking about the acute proximities between humanity, mortality, and precarity. The first decades of the 21st century has seen the Mexican War on Drugs unleash violence on many fronts of which narrative and historicization are among the most fiercely contested. In his discussion of the early works of two well-known cultural workers, the artist Teresa Margolles and the writer Sergio González Rodríguez, Romero observes how law is sometimes most recognizable because of the destruction it enables in the name of enforcement. Accounting for death through statistics or memory is not enough; what was and is needed is what Romero movingly describes as a “radical grammar of the dead.” How does art retool or even overhaul structures of communication so that death is no longer a sign of finality but a means to imagine how life might flourish through new narratives rather than perish in the service of entrenched state-versus-outlaw binaries? How might the lens of art initiate more nuanced discussion of the ways in which unmediated feelings open new pathways for a commons-based approached to a legal imagination that must account for lives often rendered invisible or voiceless? Yet the illegality of Margolles’s choice of materials, including parts salvaged from human corpses, raises ethical questions about the nature of artistic privilege and the contradictions of a legal system that allows certain illegal activities depending on the identity of the actor.

Some readers may ask if this issue tacitly endorses a kind of New Historicism of art and law that endeavors to understand art’s history through law and law through the context of art’s structures, protocols, and histories. In some respects, yes: many of the contributors are practicing lawyers or legal scholars invested in a tactical relativization that undoes some of the a priori assumptions those in one discipline or profession might have about others. I am also thinking of the small but dedicated coterie of legal scholars for whom specific artworks and the operations of art world infrastructure have been a source of encouragement for thinking imaginatively about the limits, operations, and perhaps most importantly, the futures of law.Footnote42 Neither they nor the contributors of this issue take either “art” or “law” for granted, whether in terms of meaning, implication, properties, audiences, or its constituents. This issue concerns the law as refracted through a belief in the vitality of art and its structures as much as it concerns art by those trained or invested in thinking deeply about law’s operations. What forms of association does art bring to law and vice versa? What knowledges does art and law produce when we acknowledge their existences as reciprocal? What is it that we allow ourselves when we actively recognize art and law as coterminous?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joan Kee

Joan Kee is Professor in the History of Art at the University of Michigan and the Robert Sterling Clark Visiting Professor at Williams College. A public interest attorney based in Detroit, she has written extensively on the intersection of contemporary art and law, including an edited forum on the subject for the Brooklyn Rail, and articles in Artforum, Law and Humanities, American Art, and Law, Culture and the Humanities. Kee’s most recent book is Models of Integrity: Art and Law in Post-Sixties America (University of California Press, 2019).

Notes

1 For the full text and close reading of the transfer agreement see Rebecca Johnson, “Implementing Indigenous Law in Agreements – Learning from ‘An Agreement Concerning the Stewardship of the Witness Blanket’,” Reconciliation Syllabus, January 31, 2020. https://reconciliationsyllabus.wordpress.com/2020/01/31/implementing-indigenous-law-in-agreements-learning-from-an-agreement-concerning-the-stewardship-of-the-witness-blanket/ (accessed October 25, 2020).

2 Interestingly, the agreement appears to explicitly acknowledge Newman’s moral rights to Witness Blanket in mentioning “the Newman family’s inherent connection to the Witness Blanket.” “An Agreement Concerning the Stewardship of the Witness Blanket – A National Monument to Recognize the Atrocities of Indian Residential Schools,” https://reconciliationsyllabus.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/witness-blanket-stewardship-agreement-v04.4.pdf (accessed March 11, 2021). I speculate whether the agreement would be even more effective if it included a fiduciary duty clause obligating both Newman and the museum to act in the best interests of the work.

3 James Boyd White, Justice as Translation: An Essay in Cultural and Legal Criticism (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 91.

4 The editorial work of Daniel McClean, a practicing lawyer specializing in art-specific transactions, has provided much valuable primary and secondary source material for tracking this history in an Anglo-American context. See, for example, Dear Images: Art, Copyright and Culture, co-edited with Karsten Schubert, (London: ICA and Ridinghouse, 2002); The Trials of Art (London: Ridinghouse, 2007); and Artist, Authorship & Legacy: A Reader (London: Ridinghouse, 2018).

5 Peter Goodrich, “Law by Other Means,” Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature 10, no. 2 (Winter 1998): 116.

6 I thank Marco Wan for opening my eyes to the dense and exciting array of scholarship in this area, including Martha Nussbaum, Poetic Justice: The Literary Imagination and Public Life (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1995); Ian Ward, Law and Literature: Possibilities and Perspectives, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); and Peter Goodrich, “Screening Law,” Law and Literature 21, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 1–23.

7 Goodrich, 116.

8 Relatively recent examples of such inquiry include Law and Art: Justice, Ethics and Aethetics, ed. Oren Ben-Dor, (Abindgon and New York: Routledge, 2011); Thomas Dreier, “Law and Images,” Brill Research Perspectives in Art and Law 3, no. 1 (2019), Joan Kee, Models of Integrity: Art and Law in Sixties America (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019); and Research Handbook on Art and Law, ed. Jani McCutcheon and Fiona McGaughey (Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar, 2020).

9 See, for instance, Jonathan Eburne, Surrealism and the Art of Crime (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008); Frederic J. Schwartz, “Brecht’s ‘Threepenny Lawsuit’ and the Culture of the Case,” Oxford Art Journal 41, no. 2 (August 2018): 219–47; T’ai Smith, Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 111–40; Reiko Tomii, “State v. (Anti-)Art: Model 1,000-Yen Note Incident by Akasegawa Genpei and Company, Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 10, no. 1 (2002): 141–72.

10 A welcome addition to this body of literature that takes into account artistic and legal viewpoints is Martha Buskirk’s forthcoming study Is It Ours? Art, Copyright, and Public Interest (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021). Among the most widely cited historians of contemporary art in legal scholarship, Buskirk known for her writings on copies, appropriation, and conceptual art. Scholars of intellectual property will find it especially edifying to read Buskirk’s book together with Winnie Wong, Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade (Chicago, IL: Univeresity of Chicago Press, 2013).

11 See, for example, The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory, and Visual Culture, ed. Frances Guerin and Roger Hallas (New York and London: Wallflower Press, 2007); Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone, 2008); and Jane Blocker, Seeing Witness: Visuality and the Ethics of Testimony (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

12 A recent illustration in point is Lee Anne Fennell, Slices and Lumps: Division and Aggregation in Law and Life (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019).

13 Luis Gómez Romero and Ian Dahlmann, “Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels,” Law Text Culture 16 (2012): 6.

14 Ibid., 6.

15 Jonathan Kramnick and Anahid Nersessian, “Form and Explanation,” Critical Inquiry 42, no. 3 (Spring 2017): 661.

16 Pak Sheung Chuen, untitled text exhibited in “Chris Evans and Pak Sheung Chuen: Two Exhibitions, Para Site, Hong Kong,” c. 2017.

17 Ibid. My thinking on politics here is drawn from Sheldon Wolin’s description of the “legitimized and public contestation, primarily by organized and unequal social powers.” Sheldon Wolin, “Fugitive Democracy,” Constellations 1, no. 1 (1994): 12.

18 Desmond Manderson, Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 183.

19 Ibid., 162.

20 Among the most notable responses or engagements with Harris’s article have been the works of Cameron Rowland which often involve various legal concepts and financial instruments such as Disgorgement (2016). The work displays the full contents of a “Reparations Purpose Trust” that promises to liquidate shares in Aetna when the U.S. government pays reparations for slavery. Aetna is a major insurance company that profited from slave insurance policies.

21 Cheryl I. Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review 106, no. 8 (June 1993): 1725–36.

22 Gordon Bennett quoted by Kelly Gellatly, “Citizen in the Making: The Art of Gordon Bennett,” in Gordon Bennett (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2007), 14.

23 Sarah Lewis, “Vision and Justice: Guest Editor’s Note,” Aperture, February 23, 2016. https://aperture.org/editorial/vision-justice/ (accessed October 1, 2020).

24 Phillip Areeda, “Comment: Always a Borrower: Law and Other Disciplines,” Duke Law Journal 37, no. 5 (1988): 1043.

25 Ibid., 1043.

26 Peter Goodrich, “Screening Law,” Law and Literature 21, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 15.

27 Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 40–1.

28 The most law-specific application of performativity theory may be Butler’s Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative (New York and London: Routledge, 1997).

29 The prison was shuttered in January 2013.

30 Bryant’s observations were made during the course of filming Flag Wars, which she produced with Laura Poitras, well known for her documentaries about Edward Snowden and Julian Assange. Linda Goode Bryant, “‘Law is Life!’: Flag Wars, Local Government Law, and the Gentrification of Olde Towne East,” Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal 16, no. 3 (2006): 720–3.

31 Eyal Weizman, “Introduction: Forensis,” Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014), 29-30.

32 Shame has been a powerful enforcement mechanism in other realms of cultural activity as well. Amy Adler and Jeanne C. Fromer’s article “Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands” explores how individuals, including artists, have sought relief for intellectual property infringement turn to shaming on social media as a more effective alternative to litigation. California Law Review 107 (2019): 1455–530.

33 Yxta Maya Murray, “Rape, Trauma, the State, and the Art of Tracey Emin,” California Law Review 100 (2012): 1680.

34 Charles R. Lawrence III, “Passing and Trespassing in the Academy: On Whiteness as Property and Racial Performance as Political Speech,” Harvard Journal on Racial and Ethnic Justice 31 (2015): 14–15.

35 Although a lawyer prepares or otherwise facilitates the negotiation of a purchase contract with Sehgal, the terms of the contract are orally repeated to the buyer and a wire transfer made to the artist. For an account of how Sehgal developed his transactional model, see Hans Ulrich Obrist interviews Tino Sehgal,” Kunsthalle Bremen (Bremen: Kunstpreis der Böttcherstrasse, 2003), 50–5. For an example of a Sehgal agreement see Elizabeth Singer, “Be the Work: Intersubjectivity of Tino Sehgal’s This objective of that object,” in On Performativity, ed. Elizabeth Carpenter, vol. 1 of Living Collections Catalogue (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2014), footnote 23. http://www.walkerart.org/collections/publications/performativity/be-the-work/ (accessed July 12, 2016).

36 Representatives from both the Walker Art Center and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have characterized the purchase of Seghal works as especially difficult, provoking debate among otherwise consensus-prone acquisitions committees. Arthur Lubow, “Making Art Out of an Encounter,” The New York Times Magazine, January 15, 2010, 24.

37 For a theoretically informed discussion of examples of this kind of collaboration see Lucy Finchett-Maddock, “Forming the Legal Avant-Garde: A Theory of Art/Law,” Law, Culture and the Humanities, September 13, 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1743872119871832 (accessed September 4, 2020).

38 Nicole Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 18.

39 The famous quote has been attributed to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart who contended that a particular film was not obscene even as he demurred from offering a definition of what he considered to be “hard-core pornography.” Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184 (1964).

40 “ICE Acting Deputy Director Sets the Record Straight on Fraud Investigations Involving Undercover Schools,” News Release, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 20 December 2019. https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/ice-acting-deputy-director-sets-record-straight-fraud-investigations-involving (accessed August 19, 2020).

41 Nicolas Michel, “African artefacts: Repatriation activists on trial for attempted theft at Paris Museum,” The Africa Report, 9 October 2020, https://www.theafricareport.com/45048/african-artefacts-repatriation-activists-on-trial-for-attempted-theft-at-paris-museum/ (accessed August 11, 2020).

42 Some examples of this vein of inquiry include Alison Young, Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination (Routledge: Abingdon and New York, 2014); Peter Karol, “The Threat of Termination in a Dematerialized Art Market,” Journal of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A. 64 (Spring 2017): 187–233; Katherine Biber, In Crime’s Archive: The Cultural Afterlife of Evidence (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2018); Art, Law, Power: Perspectives on Legality and Resistance in Contemporary Aesthetics, ed. Lucy Finchett-Maddock and Eleftheria Lekakis (Oxford: Counterpress, 2020).