Abstract

In 1900, seven European nations gathered in London to agree the Convention for the Preservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa. The Convention sought to regulate game hunting across the African continent, in response to the decimation of wildlife that unregulated hunting for sport and ivory had caused. Six years later, Agnes Herbert and her cousin Cecily set out from London to British Somaliland on a big game hunt. In this article, I explore the interrelationships of memoirs, such as Agnes Herbert’s, with law and literary imagination in the creation of a colonial conservation culture. I do so by invoking Foucault’s thinking about heterotopias. I unpack the temporal modalities in which ideas about big game operate in administrative and literary texts: both the idea of a lost golden age and, more particularly, the futurities of big game that they construct and debate through ideas of “preservation.”

INTRODUCTION

In 1906 Agnes Herbert and her cousin Cecily set out to British Somaliland on a hunting trip. On their return Herbert wrote up their exploits in a travelogue entitled Two Dianas in Somaliland: The Record of a Shooting Trip and published by John Lane. Herbert and her cousin were by no means the first or only women to pursue big game in this period.Footnote1 Nor was Somaliland an especially unusual location for big game hunting. In the 1880s and 90s European visitors mixed big game hunting with, and as, scientific exploration as they surveyed the East African interior topographically, botanically and politically.Footnote2 While British East Africa and Uganda to the south were more renowned for their big game, Somaliland nonetheless garnered a reputation as rich territory for sport. Moreover, administered as it was until 1898 from British India, the protectorate of British Somaliland was a close and therefore regular destination for officers from both Aden and the Indian subcontinent, who pursued big game there on periods of leave for R&R.Footnote3 On arrival in Aden, Herbert and her cousin encountered two other shooting parties at their hotel destined for Somaliland: two officers from India and an older married couple. Together this trio of hunting parties typifies, in many ways, the demography of big game hunting in British Somaliland, being more or less domestic, more or less adventurous, and more or less well-heeled.

Once they landed in Berbera, which was, by then, the main port for British Somaliland, Agnes and Cecily set to work adding to their extensive array of camping equipment with supplies, camels and ponies for transport, and a large retinue of staff to support their trip, including a headman, a cook “two boys (men of at least forty who always referred to themselves as “boys”) to assist the cook, one “makadam,” or head camel-man, twenty-four camel men, four syces [grooms], and six hunters, to say nothing of a couple of men of all work.”Footnote4 While the majority of these servants remain unnamed and undifferentiated in Herbert’s account, two were given nicknames by Agnes and Cecily: the Baron Munchausen, named on account of his purported penchant for lying; and Clarence, so called because Agnes and Cecily couldn’t pronounce his name but agreed it sounded “more like “Clarence” than anything.”Footnote5 These two men proved crucial to the expedition, Clarence as leader of their entourage and the Baron as his second in command. Both men, moreover, tactfully mentored the two cousins and facilitated the hunt, Clarence providing what Herbert calls, “excellent stage-management,” by coordinating the other six hunters to drive animals into range for them.Footnote6

Their entourage established, Agnes and Cecily set off across British Somaliland and over the border into the Ogaden region of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia), shooting a tremendous number of mammals as they went. These included antelope of various kinds, warthogs, lions, leopards and three rhinoceroses. These creatures were then assessed, measured, recorded in notebooks, and their carcasses dissected for the purposes of preserving hides, horns and heads as trophies, and of feeding the extensive hunting party.

Herbert’s descriptions are by turns lyrical, humorous and grisly. The first episode of the chapter entitled, “Cecily Shoots a Rhinoceros,” describes Agnes and Cecily stalking and observing a family of ostriches: “I cornered one little fluffy yellow and black bird, and could have caught him had I wished. He was about twelve inches high, very important looking, and his bright black boot-button eyes gazed at me unblinkingly. Stout little yellow legs supported the tubby quaint body, and then I let him pass to gain solitude and his brothers.”Footnote7 Herbert’s descriptions are rarely those of the scientifically attentive naturalist but seem aimed to make accessible, often through domestic metaphor and imagery (“boot-button eyes”), the flora and fauna of Somaliland to a reader unfamiliar with the experience of big game hunting themselves. She is disarmingly visceral at times, describing, for example, her attempts to hack off the head of a shot oryx with a small hunting knife, driven by a desire not to leave behind the trophy of his horns.Footnote8 Nonetheless, the book rarely becomes self-heroizing and on the occasions it does so, these passages are usually accompanied by a self-knowing tone or are rendered through a performance of modesty.

Why then am I interested in this peculiar and yet not uncommon book and the peculiar yet not uncommon story of two women hunters in Somaliland that it contains? I am interested in what Herbert’s book communicates to us, both through what it contains and what it does not, about the entanglements of law, colonialism and the environment with transgression, nostalgia, and romance at the turn of the twentieth century and the dawning of governmental and intergovernmental conservationism as we know it today. In the late nineteenth century, the British government, like others, began to introduce specifically conservationist legislation at home and in the colonies. These laws laid the ground for the establishment of national parks and nature reserves as ecosystems worthy of preservation. They also regulated practices, such as trade in feathers, that were seen to endanger individual species. This legislation had different implications in different contexts. Focusing on a specific example, the British Somaliland Protectorate, and a particular account, Herbert’s memoir, allows us to unpack some of these implications. In doing so, we can trace the tangled relationships between law and romance as routes by which colonial powers negotiated the pasts, presents and futures of their conservationist impulse.

In what follows I aim to illustrate these entanglements through engagement with Foucault’s notion of the heterotopia. The heterotopia, as a “counter-site” that offers a “simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live,” provides a productive paradigm by which to make legible the operations not only of the nature reserves established through conservationist legislation at the turn of the century but also of the protectorate as a colonial form.Footnote9 As I demonstrate these operations enfold both law and romance in ways that challenge our expectations. I begin by providing some brief historical and geographical context to Herbert’s book. I go on to consider the various conventions, tacit and overt, that governed the region, its environment, big game hunting and writing about it. In exploring these conventions, and the licence taken with them by writers, hunters and administrators, I argue that nostalgia and romance were written into the early legal governance of colonial conservationism.

CONTEXT

British colonial interest in the Horn of Africa was always strategic. Situated at the point that the Red Sea empties out into the Gulf of Aden, and across from the port of Aden itself, the Northern coast of the Horn was seen as crucial to protecting British trade routes into the Indian Ocean after the opening of the Suez Canal. Nonetheless, British control of what became British Somaliland came about not through strategic planning from London but as a result of unsanctioned actions taken by Frederick Mercer Hunter, an officer in Aden’s colonial administration, which was governed from British India at the time. In 1875 Egypt had claimed control of the Somali coast and, as James Fargher argues, the British had been willing to allow a “friendly power” to control the coast, judging that “the establishment of Egyptian garrisons in the Somali ports would be a cost-effective method of keeping [European] rivals out of the region and of securing Aden’s food supply from the Somali interior.”Footnote10 The upheavals in Egypt in the 1880s, however, led to concerns in British India for the security of the Somali ports. Hunter shared these concerns and took pre-emptive and unauthorised steps to secure Berbera and to remove the Egyptian governor. Hunter went on to agree treaties with Somali clans not only along the coast but increasingly further inland, establishing the basis for the protectorate, which was formally established in 1887, with Hunter as its first governor.

It was not long, however, before the protectorate experienced its own upheavals. By the end of the nineteenth century, discontent boiled over leading to an uprising led by Sayyid Muhammed Abdullah Hassan. Hassan was both critical of the Qadiriyya Islamic order then dominant in Somali society and resistant to colonial rule. Hassan waged two decades of violent resistance against the British across the protectorate’s borders with Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia, mobilizing Somali clans and clan alliances that criss-crossed these recently agreed boundaries.Footnote11 Herbert and her cousin visited during a brief interval of relative peace but it was only in 1920 that Hassan was finally defeated following the first military deployment of the RAF after the First World War.

CONVENTION

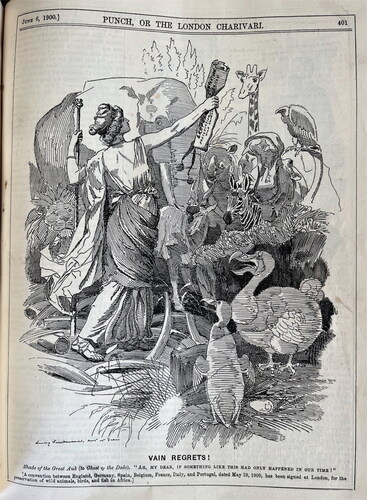

Soon after the establishment of the British Somaliland Protectorate, the British Foreign Office suggested the need for regulations controlling the hunting of game in Britain’s African territories, building on legislation introduced in the Cape Colony in 1886. Meanwhile, in German East Africa, the governor, Herman von Wissmann, not only introduced hunting licences and game reserves in the German colony but also contributed to increasing calls for European collaboration around game preservation on the African continent. In Britain these calls came from an influential set of lobbyists, who drew on their credibility as hunters, administrators and politicians to make the argument for game preservation.Footnote12 Their argument was that without action the colonies would lose not only the sport but also the beauty of the African continent’s fauna. To make their point, they drew comparisons between the potential fate of Africa’s big game and the fate of the American bison as a consequence of unchecked hunting for sport. Von Wissmann and the conservationists were successful and in 1900 the Convention for the Preservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa was signed in London on behalf of the monarchs of the United Kingdom, Prussia, Spain, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and the French president. The Convention received relatively brief notices in the press but was marked with a full-page cartoon in Punch (see ).

Figure 1. Edward Linley Sambourne, “Vain Regrets!” Punch 6 June 1900, 401. The image shows Europe, as a goddess, clutching the convention in front of a gathering of animals. L-R: lion, elephant, eland, rhinoceros, zebra, giraffe, hippopotamus, vulture, ostrich. In the foreground are a great auk, a dodo and a large bird’s egg. The caption reads: “Shade of the Great Auk (to Ghost of the Dodo). ‘Ay, my dear, if something like this had only happened in our time!’” In fact, the African animals depicted were granted different levels of protection under the Convention, with elands and giraffes allotted the highest protection on account of their rarity, and vultures on account of their usefulness. By contrast, the Convention sought to reduce lion populations “within sufficient limits.”Footnote71

The first article of the Convention stipulated the zone within which the provisions of the Convention would apply. This zone incorporated everything from the twentieth parallel North as far South as “the northern boundary of the German possessions of South-Western Africa” and the Zambesi River.Footnote13 The second article set out which animals were to be protected from “hunting and destruction” and under what conditions the hunting and destruction of other animals were proscribed, e.g. “when accompanied by their young.”Footnote14 A series of schedules outlined the various species to which these various conditions applied. The second article also required the establishment of reserves from which all hunting would be banned. These reserves should be of “sufficiently large tracts of land which have all the qualifications necessary as regards food, water, and, if possible, salt, for preserving birds and other wild animals, and for affording them the necessary quiet during the breeding time.”Footnote15 In addition, the second article stipulated that outside the reserves closed seasons should be established and that licenses should be issued for any hunting. The second article also proposed export duties for certain hides and horns, restrictions on certain hunting methods, such as nets, and bans on others, such as dynamite. Ensuing articles agreed timelines for the promulgation of these new rules and scope for introducing improvements to them. Article four committed the signatories to exploring the possibilities for the domestication “of zebras, of elephants, of ostriches, &c,”Footnote16 while article six committed the British government to pursuing diplomatic routes to bring non-signatory powers within the zone into line with the convention.

Significantly, the third article posited exceptions that could be applied to the rules. These exceptions applied where hunting was for “scientific” and “zoological” need or when administrative necessity demanded, such as “temporary difficulties in the administrative organisation of certain territories.”Footnote17 The provision of grounds for exception signals the tensions inherent in the competing claims made upon the African colonial territories by the Convention as spaces that might be kept untouched and yet that required untrammelled taxonomy through scientific epistemologies and “administrative organisation.” As we shall see, the exception of temporary difficulties applied almost immediately in British Somaliland, when the troops brought in to fight Hassan hunted game extensively to feed themselves.

The Convention was initially agreed between European powers, despite the fact that non-European rulers also governed regions within the territory demarcated in the agreement. Following the Convention’s signing in London, the European powers sought statements of consent from these other rulers, recognising that without their support the articles of the Convention would only have limited effect both in regulating game hunting and in generating the revenues sought through export tariffs on ivory, horn, feathers and hides. The Sultan of Zanzibar agreed to apply the articles of the Convention to Zanzibar’s mainland territories without much discussion.Footnote18 Emperor Menelik II of Abyssinia was less easily persuaded.

This had particular implications for British Somaliland whose borders with Abyssinia had only recently been agreed in 1897. Correspondence relating to the Convention, published by the Stationer’s Office in 1906, includes the diplomatic letters between the Foreign Office, British officials in Addis Ababa, and Italian diplomats, attempting to persuade Menelik to adopt the Convention, or at least to support its aims through the regulation of trade in horn and ivory. South of Somaliland, Menelik’s reluctance to ratify the convention threatened to open up new routes for trade in ivory and horn, as is made clear in an anxious report written in 1903 by C. W. Hobley, an assistant in the British East Africa administration, concerned that Swahili and Arab traders in the protectorate had received “friendly overtures from the Abyssinians at the north end of Lake Rudoph … [whence] there is safe caravan route … to Addis Abbaba [sic].”Footnote19 For Brigadier-General E. J. E. Swayne, who became Governor of British Somaliland in 1902, the porosity of the protectorate’s border with Abyssinia meant that the Abyssinians, “since the rectification of the western boundary in their favour, [had] with their paid Midgan [sic] gunmen, over-run the western plains on the Somaliland border, practically wiping out in a few years the great numbers of hartebeeste [sic] and oryx which formally swarmed there, and [had] cut off the supply of elephants at its source in the highlands of Harrar.”Footnote20 The emperor continued to resist pressure from the European powers to sign the Convention, on the grounds that “while … he will not fail to cooperate … His Majesty hesitates to undertake an engagement which he knows he is unable to fulfil, owing to the special conditions of the country.”Footnote21 Menelik’s invocation of “special conditions” echoes the language of the Convention itself, with its provision of exceptions where there are “difficulties in … administrative organisation of certain territories.”Footnote22 Thus, while Menelik and the Convention’s signatories responded differently, both disavowed the possibility of implementing the Convention perfectly in the very process of agreeing to it.

The relative paucity of official correspondence concerning the British Somaliland Protectorate’s implementation of the Convention, compared to other colonies such as British East Africa, suggests that it was not a high priority for the protectorate or for the Foreign Office, who led on the Convention’s implementation. Nonetheless, the correspondence shows administrators offering their own observations on the best ways to implement the articles in the protectorate, given its particular economic conditions, patterns of trade and animal populations. Relatively slight though the correspondence is, it illuminates the tensions and contradictions that, from the start, infused the Convention and its implementation in the colonies. We see exactly these tensions and contradictions, for example, in a letter of March 1901, from the protectorate’s Consul-General, J. Hayes Sadler, to Lord Landsowne, then Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. In this letter, Sadler sets out his approach to implementing the articles of the Convention and his rationale for the particular exceptions he wishes to make to full implementation, based on local circumstances. Thus he explains:

I have omitted the word “feathers.” There is a small trade with Harrar [Abyssinia] at Zeyla [British Somaliland] in ostrich feathers, and at Berbera and Bulhar [British Somaliland] a trade of over a lac [sic] of rupees with the Ogaden [Abyssinia]. Neither at Zeyla, nor at Berbera and Bulhar, would it be possible to ascertain whether the feathers are those of ostriches kept in a domesticated state or not, and I should be averse, if it could be helped, to close a trade in ostrich feathers brought from beyond the limits of the Protectorate, which has been long established at our ports.

In the Protectorate itself the ostrich is now rare. A few birds are domesticated at Bulhar and Hargeisa [British Somaliland].

… In view of the fact that … the chances of obtaining an elephant are now remote, I consider that we should not charge more than two-thirds of the East Africa rates for licences….

I would also be inclined to give the officers of the Aden garrison the advantage of a “public officer’s” licence and to a limited number in each year. Previous to the transfer [of administration from Aden to the Protectorate itself], officers from Aden used frequently to visit the Protectorate, and for those who are unable to afford the expense of a journey home, Somaliland is the only place to which officers from Aden can repair for a short relaxation in the summer. For this we would wish to give all possible facilities.

…We are not yet in a position to prohibit the killing of game by the tribes in the interior, the Midgans [Madhiban] especially having been accustomed from time immemorial to live on the proceeds of the chase.Footnote23

I quote Sadler at length because his correspondence here illustrates many of the contradictions that arose in the process of implementation. For example, Sadler’s letter fails to connect the protectorate’s unregulated trade in ostrich feathers with the rarity of the bird. Similarly he fails to entertain the possibility that lowering the rate paid for licences might further jeopardise the already scarce elephant population. At the same time, Sadler’s elision of home comforts and the rigours of hunting exotic game, in his argument for exceptions to be made for officers of the Aden garrison, finds an unwitting parallel in his rationale to exempt the populations of the interior from hunting regulations on the basis of convention. While the Madhibans hunt of necessity and the officers for pleasure, the conventions of necessity and pleasure are used to bypass the full imposition of the Convention by Sadler. His letter thus takes license with the Convention, creating exceptions that seem to stretch to the limit of their definition those outlined in Article 3, namely “important administrative reasons” or “temporary difficulties.”Footnote24

RESERVES

In “Heterotopias of the Environment: Law’s Forgotten Spaces,” Andreas Kotsakis provides a persuasive reading of the legal idea and operations of “the nature reserve of Western environmentalism” in the light of Foucault’s theorisation of heterotopia.Footnote25 Invoking Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, Kotsakis argues that “[e]arly environmental discourse … sought to transform the previously empty, value-neutral physical space into an aesthetically pleasing and thus intrinsically valuable landscape.”Footnote26 Once designated as such, he suggests, reserves embody the characteristics of what Foucault calls “crisis heterotopias,” thereby “ensuring that this rejuvenation [of nature] “takes place elsewhere,” so as not to interfere with continued urban development.”Footnote27 The reserve becomes a “buffer space against complete degradation” and a space for “future restoration.”Footnote28 As such, like Foucault’s heterotopia, it becomes sealed off while nonetheless remaining “penetrable.”Footnote29 In the context of the reserve, Kotsakis suggests that access is only permitted to an elect few who “have embraced specific ethics … [and] speak a certain truthful discourse” that adheres to the preservationist values of the reserve.Footnote30 We find this ideal of the reserve writ large in the petitions made by groups such as the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire, in the years before and following the signing of the Convention. In June 1906, for example, at a meeting with the Earl of Elgin, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, Edward Buxton opened proceedings by observing that there “is no more beautiful or interesting sight within the Empire than the masses of great game visible from the windows of the train” as it passes along the Southern Reserve in British East Africa.Footnote31 On this basis of beauty he entreats that such reserves “should be treated as sacred.”Footnote32

Kotsakis’ definition makes visible the temporal slipperiness of the reserve as heterotopia. “Degradation” and “restoration” occur over time. Reserves, then, are maintained not only as spaces “elsewhere” but also as a “sort of absolute break with … traditional time.”Footnote33 Indeed Foucault identifies this characteristic, which he calls “heterochrony,” as his fourth principle of heterotopias.Footnote34 Foucault elaborates that the temporal break that the heterotopia effects can take two forms. On the one hand, it can be “fleeting, transitory … in the mode of the festival”; on the other, it is the indefinite accumulation of time, exemplified by the museum.Footnote35 Moreover, Foucault suggests a third kind of temporal heterotopia, exemplified by the “vacation village,” which (re)constructs an exotic and “primitive” environment for the leisured pleasure of the visitor, who encounters therein a sense of an untouched past and thereby the collapsing of temporal order.Footnote36 As we shall see, this third kind of temporal heterotopia finds parallels in colonial conservationist practice.

Whilst Kotsakis takes his cue from postwar environmental discourse, his diagnosis of the reserve in heterotopian terms is equally productive when examining the conservationist turn in colonial practice at the start of the century. In Brigadier-General Swayne’s 1905 report, he attributes the reduction of big game “almost, if not entirely, to European sportsmen and the movement of troops.”Footnote37 The troops to whom Swayne refers were those introduced to counter Hassan’s resistance movement. Swayne notes that as well as hunting game for sport, these troops permitted their attendants to hunt game for food, “although sheep were at all times easily obtainable.”Footnote38 This unregulated hunting is thus the kind of degradation that is a by-product of modernity embodied in the militarised colonisation of the protectorate. Such degradation gives rise to a demand for a heterotopic elsewhere in the form of reserves where no game hunting is permitted “except by special license.”Footnote39 These reserves create space for an alternative future in which the past is restored, existing in parallel with, yet uncontaminated by, the contemporaneous pursuits of modernity, whether agricultural, such as the ostrich farming to which Sadler refers, or military, as we find in Swayne’s report.Footnote40

Moreover, in pushing Kotsakis’s analysis of the reserve back from the postcolonial into the colonial era, I think we can complicate his model. For, as its name implies a “protectorate” also operates as a kind of reserve and thus as another heterotopia. Foucault himself observes that “certain colonies” have functioned as heterotopias, by positing “a space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled.”Footnote41 While Somaliland’s two reserves are spaces of exclusion and thus exclusiveness, nonetheless the game regulations imposed across the rest of the protectorate, and the discourse applied to them, likewise set Somaliland apart as a spatial and temporal elsewhere to imperial modernity even while subject to it. This is apparent in Sadler’s argument that officers from Aden be permitted to obtain public officers’ licenses because “Somaliland is the only place to which [they] can repair for a short relaxation in the summer.”Footnote42 Sadler posits Somaliland as a place to escape the modernity of military service. In doing so he invokes the “aesthetically pleasing and thus intrinsically valuable landscape” that Kotsakis notes is created through environmental discourse.Footnote43 Similarly, in his 1905 report Swayne observes of the protectorate that “[w]ith the departure of the troops, this indiscriminate slaughter [of game] has happily become a thing of the past.”Footnote44 The withdrawal of the troops, and Swayne’s insistent one line paragraph noting that “[t]here are no European settlers in the country,”Footnote45 return and retain the protectorate in a state of exception and exemption from European and colonial modernity. In both cases, the protectorate is romanticised. Moreover, this heterotopic romanticism is as a function of the colonial bureaucracy.

Made almost invisible in this conservationist discourse are the local populations, such as the Somali graziers whose livestock fed the troops stationed in Aden. Where they do appear in the official correspondence, their roles are determined by the heterotopic paradigm of colonial conservationism. In his 1905 report, for example, Swayne argues that since Somali hunting has been a constant for centuries, during which time game numbers remained healthy, it cannot be held responsible for the more recent decline.Footnote46 Placing the blame squarely on improvement in firearms, Swayne positions the threat externally in relation to the space and temporality of the protectorate. The importation of modern firearms, and the necessity of arming the nomadic tribes in the context of Hassan’s guerrilla tactics, thus becomes a degradation of the natural and unchanging order that Swayne implies would otherwise hold true in the protectorate. Nonetheless, the Somalis are not wholly subsumed into Swayne’s heterotopic ideal, to be protected and conserved. Their nomadism and their networks of (armed) political allegiance trouble the borders of the protectorate both literally and figuratively. By insisting on a heterotopic model of conservation, Swayne’s assessment of the current situation in the protectorate makes visible the challenge of political complexity to this model of heterotopic conservation. The romanticism of, and romanticised erasure of the Somali presence in, official conservationist reports, was one rhetorical manoeuvre used to counter this challenge.

LICENCE

The future imagined by Swayne in his 1905 report is one that through careful management, licensing, and increased staffing, restores game populations for aesthetic and sporting appreciation. For, despite his criticism of the depredations made by the troops, it is not the sport itself of which he disapproves, but its lack of regulation in the protectorate. The appended observations that Swayne includes in his 1905 report, open with his recollections of former hunting exploits in Somaliland, in the early 1890s:

My brother and I were employed in the exploration surveys for the Government of India in 1891-1892. Times have much changed since then. The numbers of wild animals formerly in the country were astonishing. I remember in the rainy season of 1891, entering the rolling western plains, where, at an altitude of five to six thousand feet, we came upon a bushless tract one thousand square miles in area, covered by short succulent grass. The whole ground was covered with immense herds of hartebeest [sic], oryx, and Soemering’s and Speke’s gazelles, and troops of ostriches loomed up and disappeared in the folds of the prairie. On firing a shot the whole mass stampeded, one herd communicating its fears to another until right up to the horizon there was a crowd of galloping animals. I counted four hundred oryx in one herd, and roughly dividing the masses as well as I was able into groups of the same size, I estimated that the total number of animals I then saw could not have been less than ten thousand.Footnote47

As I have suggested already, one feature of this reimagining of the protectorate is its failure to accommodate the Somalis effectively into the conservationist heterotopia. Erasure of their troubling presence is necessary to preserve the apparent inviolability of the protectorate as reserve. Moreover, this erasure makes visible the ways in which the colonial space of the protectorate becomes layered with competing yet entangled narratives. Swayne, like Sadler before him, notes a “strong feeling amongst officers that free shooting should be allowed as some compensation for the hardships of service.”Footnote49 An overriding feature of this hard service was the ongoing military action against Hassan’s insurgency. Central to that action was the arming and maintaining allegiance of Somali clans inimical to Hassan. In the official correspondence relating to the military action against Hassan, the realities of Somali politics emerge and become relevant to colonial thinking. However, just as Somali political agency is erased in the correspondence about implementing the Convention, reference to game and the reserves is almost entirely absent from the correspondence on military operations.Footnote50 Swayne’s tall tale is emblematic of how not only romantic reimaginings of the protectorate, but also a partitioning of such reimaginings from political realities, underpinned colonial policy.

Swayne’s licence with the facts, crossing the border from fact into fiction, is of a piece with big game literature more broadly. Returning to Agnes Herbert, one of the most intriguing aspects of her book is that at least some of it is made up. Research by Gregory Kosc in the archives of Herbert’s publisher, John Lane, has brought to light her correspondence with him, in which she frankly shares her process of “embroidering.” Thus, recalling the creative licence she exercised while writing up her hunting exploits in British Somaliland for publication by Lane, she explained to him in 1908: “in the Somaliland book when you said … “lengthen”[,] I simply took the whole show across a desert”.Footnote51 Herbert’s correspondence is not wholly precise about which episodes in Two Dianas she “embroidered,” however Kosc suggests at least one incident, in which Herbert and her sister fashion makeshift bathing suits in order to take a dip at a watering hole, to the chaste fascination of their Somali entourage.Footnote52

Kosc unearths evidence in the correspondence that Herbert took this approach with most of her big game travel writing, whether recounting her own exploits (as in Two Dianas in Alaska [1908]) or when working with Lane on the publications of others. One such is Captain F. A. Dickinson’s second big game memoir, which recounted his travels in Africa with Winston Churchill, then Under Secretary of State for the Colonies. Dickinson’s first book had not been a critical success and Lane brought Herbert in to assist in the rewriting of a second volume to improve its saleability. As Kosc shows, Herbert’s correspondence with Lane expresses an enthusiastic willingness to rework the manuscript through the addition of her own inventions.Footnote53 Again, it is not clear what fabrications Herbert introduced, but, for our purposes at least, that matters less than the fact of fabrication itself. What Herbert’s invention makes visible is the slipperiness of the distinction between fact and fiction in the big game memoir. If readers expected big game memoirs to recount what their authors “did and saw” (in the words of one of Dickinson’s reviewers), their inclusion of fictitious passages is tacitly transgressive, even if such fictitious passages were a common yet unspoken feature of the genre.Footnote54 As Kosc argues, “Herbert was clearly operating under the assumption that inventing large portions of an account was standard practice.”Footnote55 Moreover, as we see in Swayne’s report of 1905, this practice informed not only the commercial genre of the big game memoir but also administrative documentation.

In Two Dianas, as in other hunting memoirs, fabrication serves to increase the text’s aesthetic pleasure. Herbert is, for example, entertainingly direct about Dickinson’s leaden prose which she sought to enliven not only stylistically but also through the invention of incidents.Footnote56 Fabrication is also used to emphasise the bravado of the author, heightening the dangers to be overcome. In Swayne’s report, fabrication serves similar yet more expansive purposes. As in Two Dianas, Swayne’s fabrication creates bravado (“eight lions before breakfast”) and aesthetic pleasure, the latter exemplified in his lyrical descriptions of the herds he and his brother had encountered at the end of the nineteenth century. The power and beauty of the scenes described are deployed to create a rhetorical appeal to the reader, in this case the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. Furthermore, the extraordinary numbers of game encountered in the past emphasises the urgent need for action in the present to counter the spectre of dwindling populations in the future. The tall tale is thus mobilised in the service of law at the same time that it posits the protectorate as a romantic space, beyond the norms of modernity. This practice of fabrication, in Herbert’s memoir and Swayne’s report, reinscribes British Somaliland as a heterotopia. Here is a place where fictional events are provided as the rationale for legislative regulation, and where fact and fiction are brought together to imbue the landscape with value worthy of protection. Somaliland thus comes to embody a heterotopic form that Kotsakis proposes “can arise from the dual impossibility of forcing the legal domain to hold too many contradictory elements (ecology and development, utilisation and stewardship, etc.), as well as of finding one single real place that can adequately represent this mixture.”Footnote57

If Herbert and Swayne’s fabrications take creative licence with the tacit convention that an author provides their reader with factual accuracy in the written record (whether in memoir or government report), another slippage emerges when we read Herbert’s memoir together with the official reports. Following the implementation of the articles of the Convention, the Commissioner of British Somaliland was required to report annually on the number and species of animals killed under licence. Swayne was replaced in 1906 by H. E. S. Cordeaux who duly submitted his returns to the Secretary of State for the Colonies. In 1906 the sportsman’s licence permitted the killing of two rhinos. In 1907 Cordeaux reduced this to one per licence. This reduction suggests that the original restrictions had not been sufficient to maintain the population. In neither the 1906 nor the 1907 return is there any record of rhinoceroses killed under licence.

Herbert went to Somaliland in 1906 and in Two Dianas she records three kills, one that she shot herself, one shot by her cousin Cecily, and one whose fate was more complicated. Herbert is at pains in her memoir to suggest that while Cecily was in eager pursuit, she [Agnes] was less so, on account of the recent trampling to death of “the Baron” by the rhino she herself had shot. Charged by this third rhino, Herbert and Cecily both shoot, injuring the creature who escapes into a thicket. Their Somali servants attempt to drive the rhino out by setting fire to the thicket but the rhinoceros does not appear. Bored, Cecily and Herbert set off in search of other sport and shoot a female lion. On their return they find amongst the smouldering embers of the thicket the charred remains of the rhino whose wounds had been too severe for it to escape. Herbert notes dispassionately: “until the place cooled it was impossible to retrieve his horns. What a pity and what a waste!”Footnote58

At first it would seem that Herbert’s or Cordeaux’s record is untrue; or, possibly, that both are untrue. Certainly, Cordeaux’s reduction of the number of rhino kills permitted in 1907 suggests that the population was declining, whether or not Herbert and her cousin contributed to that drop. Interestingly, though, Cordeaux makes no suggestion that he plans to change the internal policing of game hunting and in the draft amendments to the protectorate’s Game Regulations, sent to the Colonial Secretary for approval at the end of 1906, he includes revised proposals for Somaliland’s two reserves, extending the smaller one very slightly but reducing considerably the size of a reserve that Swayne had previously proposed should be enlarged along the Abyssinian border.Footnote59 Implicit in these decisions is a faith in the honesty of hunters and their respect for the law, despite the contradictory suggestion, signalled by the reduction in kills permitted, that the licencing system was not working.Footnote60

Early in Herbert’s account she makes a self-conscious play of being discreet about how her licences were obtained to hunt in Somaliland:

We had to obtain special permits to penetrate the Ogaden country and beyond to the Marehan and the Haweea [sic], if we desired to go so far. Since the Treaty with King Menelik in 1897 the Ogaden and onwards is out of the British sphere of influence. How our permits were obtained I am not at liberty to say but without them we should have been forced to prance about on the outskirts of every part where game is abundant. … At one time all the parts we shot over were free areas, and open to any sportsman who cared to take on the possible dangers of penetrating the far interior of Somaliland, but now the hunting is very limited and prescribed. We were singularly fortunate, and owe our surprising good luck to that much maligned, useful, impossible to do without passport to everything worth having known as “influence”.Footnote61

Herbert’s claim to exceptionalism provides an important counterpoint to my reading so far that has broader implications. This counterpoint makes visible the unequal operations of power on which the colonial heterotopia is grounded, and which are otherwise muted in Foucault’s thinking on heterotopia, despite his acknowledgement of the heterotopic work that colonies do. As I have demonstrated elsewhere, non-settler colonial forms of governance frequently relied upon the cultivation of the state of exception as a mode of ongoingness, whereby the law was made commensurate with the singularity of the administrator.Footnote62 This situating of the law in the person of the administrator creates mobility and mutability in the law and its application, so that the law becomes whatever the administrator says that it is. The licence to enact the law as the administrator saw fit was codified in handbooks and other official guidance. We see this approach written into the original form of the Convention, whose third article provides for exceptions on the basis of “important administrative reasons.”Footnote63 The correspondence concerning the implementation of the Convention illustrates that the British Somaliland administrators regularly sought to make use of this provision. Thus, for example, exercising the licence that the state of exception granted them in their administrative role, both Sadler and Swayne argue to extend an exemption to officers from the necessity of regular hunting licences, as we have seen. In Two Dianas, it is Herbert who is exempted from the law, through the application of “influence,” which in these circumstances takes on the force of law in the place of actual law. This exemption creates for Herbert an alternative space in which she is permitted to go where others are forbidden and as a consequence her power to kill is exempted from legal regulation.

As I suggest above, it is quite possible that Herbert’s claims to “influence” are another fabrication, just as it is possible that she did not shoot a single rhinoceros, within or beyond the “British sphere of influence.” If that is the case, however, her fabrication returns us to that other kind of exception: the exception from telling the truth. In either circumstance, Herbert exempts herself from the rules, whether of the Convention or of the conventions of her genre. As the preceding discussion has demonstrated, such exemptions were unexceptional. Fabrication in game hunting memoirs and official reports was not uncommon. Exceptions to the Convention were regularly proposed. The state of exception is thus endlessly malleable, operating across literature, leisure and law.

CONCLUSION

The colonial state of exception’s protean quality returns us to the heterotopia, with its “simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live.”Footnote64 The protectorate, we come to recognise, is composed, legally and imaginatively, through inherent contradictions and incongruities in the apparently factual texts of memoir and administrative report. We find this exemplified in Two Dianas when, about half way through her memoir, Herbert observes:

The reserving of the Hargeisa and Mirso as entirely protected regions has also necessarily restricted the game area. The day of the sportsman in all Africa was in that Golden Age when he, all untrammelled, might stalk the more important fauna, to say nothing of the lesser, as he listed. Now he pays heavy toll, varying with the scarcity of the quarry, and the licenses are not the least part of the expenses. Of course the needful preservation of the big game should, and inevitably must, lead to good results, since to husband the resources of anything is to accumulate in the long run. But the idea of artificial preservation and legislation seems to knock some of the elemental romance out of hunting.Footnote65

Imagining the protectorate as if it was available to the European hunter without the trammels of colonisation requires imagining the Somalis as if they come into existence only as and for the European hunter’s assistance. This way of imagining the Somalis is exemplified by Herbert and her cousin’s (re)naming of “Clarence” and “the Baron.” We find a parallel disavowal of the Somalis in their repeated exclusion from most hunting restrictions on the grounds that they have “hitherto been accustomed to depend on the flesh of wild animals for their existence.”Footnote68 Set apart from the temporality of modernity represented by the leisured European hunting for which the Convention provided, Somali hunting is made at once a part of and excluded from the protectorate’s conservationist model.

These exclusions and exceptions, in both Herbert’s nostalgically imagined Golden Age and the implementation of the Convention, make visible the unreality, the fabrication and the romance, at the heart of colonial conservationism at the opening of the twentieth century. Foucault uses the metaphor of a mirror to describe the contradictory operations of the heterotopia. He observes:

the mirror … exist[s] in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position I occupy. From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there. Starting from this gaze that is, as it were, directed towards me … I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am. The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place that I occupy … at once absolutely real … and absolutely unreal.Footnote69

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katherine Isobel Baxter

Katherine Isobel Baxter is a Professor of English Literature and Deputy Faculty Pro Vice-Chancellor (Research and Knowledge Exchange) in the Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sciences at Northumbria University. An interdisciplinary scholar in colonial and postcolonial studies she has published extensively on Joseph Conrad and on colonial law and literature. Her recent publications include Imagined States: Law and Literature in Nigeria 1900-1966 (Edinburgh University Press 2019) and “What’s love got to do with it? Law and Literature in 1920s British Somaliland” in Ethical Crossroads in Literary Modernism, edited Katherine Ebury, Bridget English & Matthew Fogarty (Clemson University Press, 2023). She is currently working on an international, collaborative project, funded by the British Academy, on comparative desert studies. The project focuses on Somaliland and the Thar desert between India and Pakistan.

Notes

1 For discussions of other women hunters in this period see, for example, Kenneth Czech, With Rifle and Petticoat: Women as Big Game Hunters, 1880–1940 (Lanham, MD: Derrydale Press, 2002), and Angela Thompsell, British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) 101–33.

2 See, for example, F. L. James, The Unknown Horn of Africa: An Exploration from Berbera to the Leopard River (London: George Philip and Son. 1888); A. Donaldson Smith, Through Unknown African Countries: The First Expedition from Somaliland to Lake Lamu (London: Edwin Arnold, 1897); Captain H. G. C. Swayne, Seventeen Trips through Somaliland: A Record of Exploration and Big Game Shooting, 1885-1893 (London: Rowland Ward, 1895 [first edition]). India also had its own well-established traditions of big game hunting and pig sticking which were regularly written up in memoirs.

3 See Captain J. C. Francis, Three Months Leave in Somaliland (London: R. H. Porter, 1895).

4 Agnes Herbert, Two Dianas in Somaliland: The Record of a Shooting Trip (London: John Lane 1908) 30.

5 Ibid. 24.

6 Ibid. 60.

7 Ibid. 227.

8 Ibid. 102.

9 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986) 22–27, 24.

10 James Farghur, “Hunter in Somaliland: Consul Frederick M. Hunter and the Creation of the British Somaliland Protectorate,” Northeast African Studies 21, no. 1 (2021): 119–36, 125. Farghur’s article provides a detailed account of Hunter’s role in the creation of British Somaliland.

11 The border with Italian Somaliland was agreed in 1894 and the border with Abyssinia in 1897.

12 For discussion of this group, see David K. Prendergast and William M. Adams, “Colonial Wildlife conservation and the origins of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire (1903–1914),” Oryx 37, no. 2 (2003). See also Correspondence relating to the Preservation of Wild Animals in Africa (London: Stationer’s Office, 1906) for the extensive correspondence and papers relating to the development and implementation of the 1900 Convention for the Preservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa.

13 Article 1, Convention.

14 Article 2, Section 3, Convention.

15 Article 2, Section 5, Convention.

16 Article 4, Convention.

17 Article 3, Convention.

18 See Marquess of Salisbury to Sir F. Lascelles (Berlin), Sir H. Drummond Wolff (Madrid), Mr. Raikes (Brussels), Sir E. Monson (Paris), Lord Currie (Rome) and Sir H. MacDonell (Lisbon), Foreign Office, 12th September 1900. Correspondence relating to the Preservation of Wild Animals in Africa (London: Stationer’s Office, 1906), 21–22.

19 Hobley to Sir C. Eliot, Kisumu, 10th June 1903. Correspondence, 207.

20 Swayne to Mr. Lyttleton, Sheikh, 21 November 1905. Correspondence, 322-30, 328. Despite his repeatedly asserted conviction that Abyssinians were causing considerable devastation to the game populations, Swayne proposed expanding one of British Somaliland’s two reserves, already established in the protectorate, up to the border and south along it, increasing the reserve’s contiguity with Abyssinia considerably.

21 [Giacomo] Malvano, Italian Minister for Foreign Affairs to Sir E. Egerton, [Rome], 5th August 1905. Correspondence, 287.

22 Article 3, Convention.

23 Consul-General Sadler (Somaliland) to the Marquess of Landsdowne, Berbera 20th March 1901. Correspondence, 129–30.

24 Article 3, Convention.

25 Kotsakis, “Heterotopias of the Environment: Law’s forgotten spaces,” in Law and Ecology: New Environmental Foundations, ed. Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011), 193-213, 195.

26 Ibid., 201.

27 Ibid., 202, quoting Foucault “Of Other Spaces,” 24.

28 Ibid.

29 Foucault “Of Other Spaces,” 26.

30 Kotsakis, “Heterotopis of the Environment,” 202.

31 “Minutes of the proceedings at a deputation from the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire to the Right Honourable The Earl of Elgin, His Majesty’s Secretary of State for the Colonies,” Correspondence, 373.

32 Ibid., 374. Italics added.

33 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 26.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Swayne to Lyttleton, Correspondence, 328.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid., 323.

40 During the early years of the twentieth century the Colonial Office also explored the possibility of domesticating zebras, one of the species singled out for protection under Schedule II of the Convention.

41 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 27.

42 Sadler to Landsdowne, Correspondence, 130.

43 Kotsakis, “Heterotopias of the Environment,” 201. There is also an echo here of Foucault’s example of the “vacation village.” Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 26.

44 Swayne to Lyttleton, Correspondence, 328.

45 Ibid., 324.

46 By contrast, Herbert asserts that “in speaking of the wholesale slaughter of Somaliland fauna by sportsmen and sportsmen so-called, one ought really to include the Somalis themselves … [I]n the days when the elephant roamed the land, their slaughter for the sake of ivory was wholesale, terrific and amazing.” Two Dianas, 244.

47 Swayne to Lyttleton, Correspondence, 326-27.

48 Ibid., 327.

49 Ibid., 324.

50 See, for example, Somaliland Dispatches: Dispatches, etc, regarding the Military Operations in Somaliland, from the 18th January, 1902, to the 31st May, 1904 (London: Stationer’s Office, 1904).

51 Agnes Herbert to John Lane, 24 May 1908, Harry Ransom Center, UT-Austin, John Lane Company Records, 1856-1933, Box 20, Folder 3. Quoted in Gregory Kosc, “Spooring for Contracts: Agnes Herbert Navigates the Twentieth-Century Publishing Industry,” Publishing History 80 (2019) 67-95.

52 Kosc, “Spooring for Contracts,” 67, 68.

53 Ibid., 82.

54 Edward Frank Allen, “The Newest Outdoor Books,” The Outing Magazine 56, no. 3 (1910), 373-74, quoted in Kosc, “Spooring for Contracts,” 82.

55 Kosc, “Spooring for Contracts,” 69.

56 See Kosc, “Spooring for Contracts,” 82.

57 Kotsakis, “Heterotopias of the Environment,” 199.

58 Herbert, Two Dianas, 165.

59 Cordeaux to the Earl of Elgin, Berbera 21st November, 1906. Further Correspondence Relating to the Preservation of Wild Animals in Africa (London: Stationer’s Office, 1909) 32.

60 Swayne, in his earlier returns, repeatedly observed that his figures were inaccurate because hunters failed to report their kills. See, for example, Swayne to the Marquess of Landsdowne, Sheikh, 3 August 1904. Correspondence, 267–628, 267.

61 Herbert, Two Dianas, 5-6.

62 See Katherine Isobel Baxter, Imagined States: Law and Literature in Nigeria, 1900-1966 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

63 Convention, Article 3.

64 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 24.

65 Herbert, Two Dianas, 148.

66 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 27.

67 Herbert, Two Dianas, 118.

68 Somaliland Protectorate Ordinance No. 2 1907. Article 25 “Restrictions on Killing Game by Natives.”

69 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 24.

70 Ibid., 27.

71 See Schedules 1 and 5, Convention for the Preservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa (London: Stationer’s Office, 1900).