ABSTRACT

In this essay, we describe a pedagogy for teaching and studying literature and cities through the embodiment of an urban sound scavenger. Extending Walter Benjamin’s figure of the ragpicker to poetically assemble disparate urban imaginaries, we explore how two linked teaching projects set in Los Angeles, CA, demonstrate listening bodies coconstituting both literary texts and urban environments.

Prelude

The archivization produces as much as it records the event.—Jacques Derrida, Archive FeverFootnote1

In South Los Angeles, CA, 58 students congregate daily on a campus less than 3 miles from what is now a relatively quiet Florence and Normandie, once epicenter of the most destructive civil disturbances in U.S. history, the LA Riots, or 1992 Rebellion. More than 25 years ago, Foshay Learning Center, located on Exposition and Western, would have been cacophonous, encircled by the whir of helicopters and the unplaceable sound of fire. Go south, around 92nd and Figueroa, and you will not now hear the cash register ring at the Empire Market liquor store, where Soon Ja Du shot and killed 15-year-old Latasha Harlins over a bottle of orange juice. Instead, you will find a Numero Uno market. On the right evening, you might hear the people gather for a vigil held every year to remember and mourn her loss. Go north, and you will find the First African Methodist Episcopal Church. How loudly might Maxine Waters have declared that a riot was the voice of the unheard?

In South Los Angeles, the 3:04 pm school bell and the effusion of bodies respond to the kindly machinic announcement by the Expo Line station that the train is arriving. A few hours later, only a nightly preacher’s amplified exhortations of faith remain. A few stops on the Metro takes you downtown. Here is the soundscape of silent skyscrapers, their empty rooms scoring the sky, as silent as the artists’ lofts left too expensive to rent. Here are the sounds of the gutted theaters-turned-jewelry emporia, the hipster noise of Grand Central Market, the strangely unoccupied public square. How silent is the instance of forgetting, the “simultaneous distraction” that Norman M. Klein diagnoses as that collective procedure that manufactures a memory and “defoliates another”?Footnote2

This essay discusses how we teach the city through the affordances of literature and sonic pedagogy. It begins with the premise that to be a student in Los Angeles also means to always be a body within a sonic environment variously organized or disorganized by competing communicative agendas. To tune in, therefore, is something to be taught. We discuss how and why the assembly of urban sonic archives matters for teaching cities, and also for living fully awakened lives in them, in Henri Lefebvre’s sense of enacting one’s right to city.Footnote3 By recycling sound from the environment itself, building urban sound archives equips students to be the aural organ for the city’s ephemeral and pervasive soundscapes while also teaching them to create spaces to hear its song.

A figural embodiment: from Walter Benjamin’s ragpicker to sonic scavenger

To teach a city as complex as Los Angeles, our pedagogy devises the main innovation of recasting a key urban-poetic figure of the scavenger in sonic terms. In theorizing the city-poet in “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” Walter Benjamin aligns a material procedure with a creative-social one, writing that “ragpicker and poet: both are concerned with refuse, and both go about their solitary business while other citizens are sleeping; they even move in the same way.”Footnote4 We read Benjamin here—as recent posthumanist, materialist, and affective turns in urban communication scholarship have gestured—as calling attention to the body’s centrality in any creative, political (and for us, pedagogic) practice of urban space.Footnote5 The body is the “hinge on which past, present and future swing … the fulcrum that folds together here and there,” meaning the site where recollection, occupation, and anticipation interanimate and propel response, affect, and cognition by the experiencing subject.Footnote6 For us, the body, in this case an amalgamation of both the student’s body and the fictive-historical body of the scavenger, is the means by which our teaching is able to link learning about Los Angeles to other cities and times.

Our theoretical framework tracks the body of the 19th-century Parisian ragpicker, who Charles Baudelaire memorializes as “knocking against walls,/paying no heed to the spies of the cops … /but stumbling like a poet lost in dreams,” as a subaltern figure with a genealogy traceable in works of urban theory and literatures: in Benjamin’s collector-flaneur, an analog of Benjamin himself in assembling the monumental Arcades Project in a montage of citations and repurposed city observations; or in Guy Debord’s Situationist who recollages the wayward cartography generated by a dérive.Footnote7 It is the body of the poet-as-scavenger, whose concern is with “refuse” and waste of a consumer society, that we track in Laura Ford’s Savage Messiah, or in the body of a marginal mentally disordered protagonist and his odd pet raven in Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge, the teaching texts of our case studies.Footnote8 What Benjamin made available for us in his reading of the poet-as-ragpicker is a procedure for recycling the embodiment of precarity. Even as the ragpicker is not the part of the boheme, as Benjamin puts it, all the boheme could recognize a bit of himself in the ragpicker because “each person was in a more or less blunted state of revolt against society, and faced a more or less precarious future.”Footnote9 In this essay, we will show how the scavenging impulse embodies an emancipatory space-making practice and how our pedagogic innovation extends that practice by using sonic forms of learning and fostering the production of space.

Laura Grace Ford and the sonic form of Savage Messiah

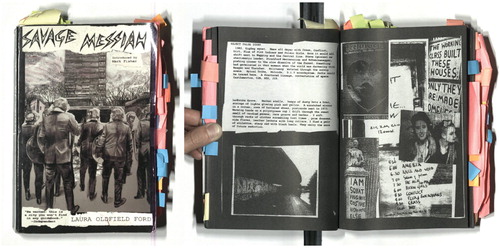

The artistic practices of Laura Grace Ford, author of the zine series Savage Messiah (2006–2009), helped us to craft a bridge between the ragpicker as scavenger of material waste and spatial ambiences, and the student as urban scavenger of sound. In Ford’s work, collection and retrieval create an archive of London laid to waste by neoliberal policies and corporatized interests, where photographs and doodles reassemble London’s derelict spaces—junkyards, squatting settlements, underground punk clubs and bars (). The recovered materials, both formal and thematic, analogize the city’s lost futures, the many Londons that might have emerged from the radical politics of the era of which she writes but are instead foreclosed. Most salient for our teaching are the ways Ford’s work transitioned from print media to multimedia installations featuring the use of sound.

Figure 1. Cover of the authors’ copy of Savage Messiah compilation displaying Ford’s zine aesthetics of an embattled London and a sampling of interior pages building an acoustic world. Typewritten details of bands and memories are composed with collaged photos of punk band line-ups and squatters’ messages.

Sound in Savage Messiah

In the print zines, the “soundscape” is constructed by explicit references to bands and DJs that punctuate the text announcing Ford’s membership in an aural community that may or may not include the zine reader. These moments function as tuning dials for the sympathetic reception of the world Ford’s narrator is traversing—one either hears, overhears, or simply misses the transmission of her signals. Interspersed between fragments of memory and historical reportage, not to mention citations of urban theory, these nominations (Spiral Tribe, The Omphalos, Flux of Pink Indians, Crass, Nobody, Gaslamp Killer, D-Styles) serve as a roll call of identities and events that in turn affiliate or alienate the reader (). The references to punk bands and DJs acknowledge the community whose outrage and lamentation are for the anarchic, anticapitalist London space that might have been.Footnote10

Translating Savage Messiah’s sonic form

After Verso compiled the zines in 2010, Ford’s work developed to include site-specific sonic installations and audio dérives. The sonic mode in the new work translates the democratic hailing of earlier countercultural spaces—the rave clubs and squatted buildings traversed by the author—into digital platforms such as Ford’s blog and SoundCloud,Footnote11 and galleries that exhibit her work. For example, in the recent exhibition “Alpha, Isis, Eden,” hosted by The Showroom gallery in London, large-format magenta prints bring Ford’s zine pages to life in full-scale realization (). With her handwriting scrawled upon the walls and advertisements for luxury real estate developments, the traces of her presence are developed further by a new sound work produced with artist Jack Latham. Audio from dérives conducted in the surrounding neighborhood among the soon-to-be-redeveloped buildings animates the space of the gallery. These field recordings are banal and only sometimes discernible—footsteps, birdsong, and found music—nevertheless they haunt the narrative voice, positing an embattled autonomous subject who mirrors this new Savage Messiah receiver-listener. Both narrator and listener are alternately stranded or subsumed by a landscape they must reassemble and interpret.Footnote12

Figure 2. Ford’s “Alpha, Isis, Eden,” installed at The Showroom gallery in London recreating the zine page as an immersive environment with barrier fencing, jarring walls, and advertisement reproductions defaced by anarchically scrawled narratives while speakers play her new sound work.

We see the zines’ aural dimension translated into Ford’s installation work in multiple ways. Firstly, the application of sound in the exhibition mimics key stylistic features of zine-making—in the use of democratically available technologies, such as photocopiers and mobile devices, and in the traces of the artist’s method, using collages of paper ephemera and compositions of sampled field recordings and diegetic music.

Secondly, the sonic dimension of the installation calibrates listeners’ reception of its space in the way shout-outs to underground music culture had done in the zines, allowing both the zine-maker and the established artist to take the measure, so to speak, of their audiences. Its recognition variously affirms, negates, or half-intimates the listener’s relationship to the imaginary space the work is inducting them into. Such uneven possibilities reveal that belonging to urban space is incomplete at best, and that inhabitation in this particular London is always inflicted by a sense of inchoate relations.

Thirdly, sounds expose the listener’s positionality vis-à-vis the urban space of which the narrator is oracle and poet. The sonic aspects of Ford’s pieces require the reader-listener-viewer to tune in amid a continual toggling between identification and disorientation. In the soundscape of the gallery, the world outside is constituted within the subjective space of the listener. Thus, if reception is constituted by the choices to either tune in or opt out, the use of a sonic environment becomes a key tactic to rehearse the politics of zine culture.

Ambient sound, susceptible to becoming background noise, is easily wasted on the inattentive. Yet tuning in foregrounds the background, or to use R. Murray Schafer’s sonographic taxonomy, the “keynote” of the place becomes its “signal.”Footnote13 This repositioning of sampled environments encourages what Michel Chion identifies as “reduced listening,” where content and sound sources are deliberately ambivalent in order to develop listeners’ capacity to attend to sound “as itself the object to be observed instead of as a vehicle for something else.”Footnote14 In this way, reduced listening produces the opportunity for socializing objectivity, what Chion calls an “objectivity-born-of-intersubjectivity.”Footnote15 The ambivalence of sound gives the listener a moment for perceptual negotiation, testing their interpretations with those made by others who also comprise the listening community.

In other words, sound enables Ford’s new forms to assert the previous zine form’s materiality—its references and scavenged properties—in a new interpretive zone complicatedly negotiated by a receiving agent. Sound enables a more granular reception, wherein the listener is called upon to acknowledge varying degrees of receptivity, to assess distance, or to feel affirmed in recognizing the world of Ford’s work and the urban spaces she inhabits, and the messages being transmitted from there.

A sonic tale of two cities, volume 1: scavenging sounds in Downtown Los Angeles

We use the potential of Ford’s body of work to extend urban communication’s emphasis on embodiment. We see sound scavenging as “experimental” reading, as Greg Dickinson and Giorgia Aiello via John Dewey qualified the “experiment” in their essay as “making a trial … out of living … to do something that requires the proof of the senses.”Footnote16 In 2016, Ford visited Los Angeles and produced “LOS ANGELES//LONDON—1934/1965/1972/1992/2003/2020,” a prose poem based on a dérive she conducted Downtown.Footnote17 During a London visit with one of the authors, Ford proposed to record sounds in and around the city to support her development of the piece. This section describes the activity that proceeded from Ford’s request as a case study for how to teach the literary text as “presonic.” We discuss how this reimagines the act of reading into urban sound scavenging. We describe the sound archive produced from the text-based lesson we conducted, concluding with preliminary implications for further application of the activity as pedagogy in a public school classroom.

In Ford’s piece, a palimpsestic imaginary of London’s Whitechapel is inserted into Downtown LA as the narrator wanders from Union Station through the Jewelry District. An unnamed interlocutor is addressed alongside musical allusions: “I hear the wafer-thin outline of a Prince song … ” and “For you the map of Downtown LA was scored by Blade Runner.” The unnamed “you” underscores the addressee’s inaccessibility: “When this track came out last summer I sent it as a YouTube rip to your old email address … I cast it like a message in a bottle and left it there waiting,” turning the text into a container of seemingly dead letters.

At the end of “LOS ANGELES//LONDON,” the urban landscape becomes indeterminate, climaxing with a flashback to an encounter with a Whitechapel vagrant woman described earlier: “She says she can see the future, a fiver and she’ll tell me … [her predictions] loop back and forth through the decades [and] are encoded with other times.” The woman, a scavenger of two cities, has made “a shelter from sacks and packing crates,” and is of course a stand-in for the poet and the work. In her figuration, waste is imaged as literal (“sacks and packing crates”) and embodied (“She embodies a vision of England shivering without a safety net”), creating an urban imaginary out of what Benjamin had called the “refuse” of history itself. The figures of the lost lover and homeless woman are spokespersons of a recycled loss, that is, a loss experienced and recovered by the narrator. Encountering London landscapes in Los Angeles conjures doppelgangers, a trope that twins longing for absent others with repressed city histories.

The status of a text we are calling presonic affords participants a unique kind of reception—to read the text while aiding its “completion” as sonic scavengers. The text is made “writerly” in the sense that Roland Barthes has defined, open-ended because of an invented sonic absence.Footnote18 While unplanned, the invitation to collect sound turns the written word into an allegory or adumbration of the sonic environment and inspires the method in our pedagogy.

A situationist LA/London

For the LA/London dérive, University of California Los Angeles graduate students’ sound collection would serve simultaneously as an exploration of a pedagogical method. They practiced Savage Messiah’s tactics of making resonant imaginaries of otherwise unremarked urban space to see what possibilities exist in them for teaching.

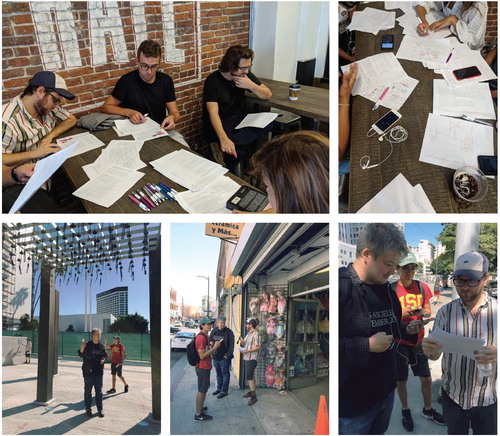

In designing this application, we took up Debord’s suggestion that producing “psychogeographic maps” begins with the “introduction of alterations such as more or less arbitrarily transposing maps of two different regions,” a point he illustrated with a friend’s wandering through the Hare region of Germany while “blindly following the directions of a map of London.”Footnote19 We layered the text of “LOS ANGELES//LONDON” over Downtown Los Angeles, asking participants to scavenge sounds in specific geographies we had identified, challenging them to further annotate the text to see if other spaces would come to mind (). We also asked for new texts: performative—a reading of Ford’s work at the location; cartographical-visual—a mental map of their walk; and lyrical-diaristic—a written creative reflection.

Figure 3. Top row: participants in “LA//London: A Summertime Playlist” preparing for their dérive by making annotations and readying their equipment (photo credit: Andrés Carrasquilllo). Bottom row: a team of scavengers wandering Los Angeles recording sounds led by Ford’s “LOS ANGELES//LONDON” (photo credit: Amy Zhou).

This “ensemble of behaviors”Footnote20 aimed to produce an archive that illumined rehearsals of Ford’s transurban imaginary. Inspired by the dérive, we would stage scenes of spatial communication through sonic practices, akin to Dickinson and Aiello’s formulation of embodied urban communication study as “being through there,” whereby the scholar “moves [away] from the city as represented [symbolic space] … to a city critically performed as social space.”Footnote21 “Being through” Downtown space for us means tracing hauntings cued by the figural guide of the scavenger, creating a matrix where the binaries of the imaged and the inhabited, the semiotic and the somatic, the cognized and the affected, could be negotiated.Footnote22 The body here mediates between the text’s excess of signification and urban space’s excess of materiality. The ephemerality of sound is registered by the archiving process as new longings, what Debord formulated as the “dreams of abundance” that result from psychogeographic exploration of otherwise commoditized urban space.Footnote23

LA/London as a sonic archive

Participants collected approximately 100 sounds on a sunny Saturday afternoon from 12:45 PM to 3:45 PM. Ford’s “LOS ANGELES//LONDON” was read in a dozen locations ranging from Indian Alley in Skid Row to a fabric store in the Garment District. Participants recorded reflections in disparate locations along routes that carried them from new loft developments to old courtyards in Santee Alley ().

Even within a sliver of its day, Downtown Los Angeles projects its commercial identity. The banality of sounds becomes suggestive because they were collected: businesses projecting sanitized pop music at opening hours, the buzz of machinery from various tools of jewelry-making, the clanking garage doors of closing time in the Garment and Flower Districts—these sounds are defamiliarized by their retrieval. Nontransactional human voices are at a minimum, although a few snippets, captured from seller–consumer interactions, are on topics that exceeded the transaction itself. Other clear sonic marks are Latino-inflected—banda music is on at Cafe Amandine, soccer plays in the bowels of the ghostly Jewelry Theater Center, the avocados are being sold dos por dollar. Some sounds are microstories: an elevator announces “R” and the silence dissolves into the celebratory poolside ambience of the Ace Hotel’s rooftop. Of course, the sounds participants make on stairs, passageways, elevators, and other interior interstitial zones reveal that our own bodies always abide. Scattered across the landscape by Ford’s writing, the charge to retrieve sounds materializes minor countercultural moves à la Ford: a satire of commercial musicscapes, a story about the history of incarceration, a memorial to labor—the listener as overhearing and eavesdropping.

In reflections that participants drafted at the end of their scavenging, we read “sharp emotional responses” that show how archivization goes beyond taxonomizing sounds to memory work that leads listeners into the community of Downtown Los Angeles by stitching their lives into the traces of sound they had scavenged:

Today the discount store is empty, like a fragment of dream bubbling up to the daylight. I think of dollar stores and my grandmother, early 1990s, same bad light. (M)

He is the theater, he lets me feel the haunting, and he is right in front of me. Then, now, here, me—the things blend. (K)Footnote24

The sound archive matters as an example of how one “warm[s]” the urbanscape with “passional” melancholy.Footnote25 Part of this passion is social; participants desire to engage others apart from themselves. The reflections personify strangers to address or cast absent dear ones in conversation. Strangely enough, the fuller the space, the more occluded its overall affective atmosphere becomes. The calling up of, or momentary occupation of, optative worlds casts a shadow on the one they had been occupying all along.

An impossible archive

What are the salient lessons from this production of an urban sonic archive? Firstly, the value of scavenged sounds is that they show participants’ attunement to the urban environment through embodying both Ford’s narrative and their own. Sound scavenging stitches the page to the street, mobilizing the entire body in the process. As urban communication scholarship has laid out, “the key site of this coproduction [of immediate and mediated experience of the city] is the body, which folds together imaged and inhabited urban experience.”Footnote26 Asking students to complete the “text” with an immersion in city space lays bare the ways the body, both fictive-historical and literal, occupies and lives in space, entangling each in the other, calling to mind the ways urban knowledge is always endlessly partial and always coconstitutional.

Secondly, if urban sound scavenging brings students into space, then the procedure also shows how space is brought “into” participants’ affective and cognitive capacities. By détourn-ing, or repurposing the text as presonic, we change the conditions of its reading, and we also transform the conditions of spatial encounter. By overlaying a literary text over the city, urban sounds are “storied,” now portals for discovering a city uncannily full of intimacies one could have known or wanted to know. Scavenging sounds make the city’s secrets public, as one of the authors who participated in the audio-dérive reflects:

Capital is waiting for its time, and its time is different from the sounds I hear. If historical materialism has a teleology this is small history, this is little time. I hear it and if I don’t it doesn’t exist. It is a moment, a flash in the pan, a spark from the machine. We only have little time—scavenging sounds that fade and disappear. This is the time of people, humans, animals, us. The rumble of change, of consumerism, it doesn’t need me or anyone else to hear it.Footnote27

Thirdly, scavenging orients the interlocutor of space to what is ad hoc, contingent, and discarded, a precious orientation. It matters to the activity that participants see their work as impelled by a desire to revalue, to take up an anticommoditizing stance in a world where materiality’s fungibility seems a fait accompli. In the tradition of Benjamin, Debord, Lefebvre, and Ford, participants unplug from transmissions of capital and accumulate experiences of noninstrumentalized space. In this way, participants produce a record of alterity, in fact, of loss—of experience, community, authentic address—incurred by the inhabitants of the urban spaces of our time.

A sonic tale of two cities, volume 2: scavenging sounds in South Los Angeles

A sonic fragment

The sound was collected from Vermont and Slauson, where Armando took his last breath. 26 years later, the body shop that once stood there is now a Taco Bell. With this sound, I want the listener to imagine what a normal morning may have sounded like for 18-year-old Armando Ortiz. (Jonathan, 17)Footnote29

This fragment of the environment retrieved by Jonathan, the sound of birds in the parking lot of Taco Bell, is embedded within a network of histories assembled by a project culminating a high-school literature unit on Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge. In the unit, Jonathan and his classmates studied two distinct time periods and places apart from their own: the 1992 events, and late 18th-century London—the setting for the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780, the subject of the novel.

This section provides an account of how Dickens’s novel became the new text for a pedagogy using sonic scavenging, and how we extended this method—sound scavenging of space—into space-making through sound. Here we mean not only virtual space, but rather, producing space in the Lefebvrian sense of its triadic dimensions, space as perceived, conceived, and lived. The method here considers how bodies of text and space could be conscripted as presonic in the same sense as Ford’s “LOS ANGELES//LONDON,” and how such a procedure enables students to critique their environment by constructing a countersocial imaginary of South Los Angeles. We turn the canonical literary text, as an emblem of an alienated Eurocentric schooling, into a portal to and through the students’ neighborhoods.

The pedagogy aims to expose the history of South Los Angeles transformations as fettered to racist agendas, to enable students to perceive, for example, how recent signs of gentrification are in fact continuous with disinvestment and policing borne by families then and now, and to ultimately locate themselves as powerful and eloquent in shaping their neighborhood moving forward. Building an urban sonic archive teaches students to be producers not only of knowledge but of this neighborhood space. Through a variety of artistic practices (composition, exhibition, community mapping), we asked students to seize the means of production of South Los Angeles, where their collection of urban environmental sound becomes a resource for students and their community to represent and occupy space itself.

A sonic translation of Barnaby Rudge

In two hours, six-and-thirty fires were raging … in every quarter the muskets of the troops were heard above the shouts and tumult of the mob.—Charles Dickens, Barnaby RudgeFootnote31

Inspired by a close reading of chapters in the novel where Dickens represents key moments of the Gordon Riots, from the storming of Newgate to the burning down of Langdale Distillery, the unit tasks students to compose an album “single” by translating stylistic and thematic concerns of a particular passage into its contemporary sonic analog for the 1992 event. Their project extends the concept of sound scavenging by intensifying the second part of the Benjaminian analogy—the scavenger as a poet. After all, Benjamin had defined the scavenger not only as a figure of retrieval, but also of assembly. Understanding space not only as the built environment, but also as the policies, power relations, and imaginaries that inhere in the bodies, human and nonhuman, that constitute it, we imagined the learning products of the unit: an album, an exhibition, and a map, as not only representations or symbols, but productions, of South Los Angeles.

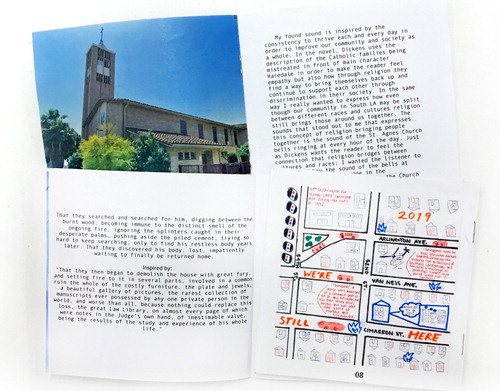

Assembling Never Say Die: A Sonic Tribute to the LA 1992 Rebellion

In this project, students followed the lead of a fragment from a passage, and détourned pieces of Dickensian prose into lists in homage to the Dickensian syntactic habit in the novel.Footnote35 They then scavenged sounds from their homes, parks, and neighborhoods, locating spaces linked either thematically or historically to their project’s concerns. What resulted is an archive of field recordings, poetic readings, interviews, found music, and news reports that provide the source material for students’ compositional challenge to mix, sequence, and reassemble these fragments into a whole ().Footnote36 Their album, Never Say Die: A Sonic Tribute to the LA 1992 Rebellion, officially “dropped” on SoundCloud at the conclusion of the unit.Footnote37

Figure 4. Liner notes students created to accompany the scavenged sounds revealing their inspiration, rationale, and the locations where they were recorded.

In this study of the novel, students are not simply tasked with reconstituting Dickens’s aims in an analysis of literary techniques; rather, they are asked to consider the text as source material for themes and characters to justify a sonic exploration of their own neighborhood. For example, one group homed in on the role of women in urban uprisings, spurred by a reading of Dickens’s representation of female rioters outside of Newgate: “a score of miserable women, outcasts from the world, seeking to release some other fallen creature as miserable as themselves.”Footnote38 They collected domestic sounds from each of their homes (e.g., washing machine, doing dishes, sweeping) to weave with fragments of lullaby and poetry for their final project, “through my mother’s eyes,”Footnote39 a pastiche of imagined maternal emotions and desires during the 1992 Rebellion. Another group reimagined the aristocratic villains of the novel as Los Angeles’s media machine in their project “Only God Can See Us.”Footnote40 The group mixed street-level sounds from contemporary walks to Tom’s Liquor, the “epicenter” of the Uprising at Florence and Normandie, with sampled news commentary and helicopter noise from that historical day. Their single critiques spectatorship as an extension of the violence itself. These two examples of eleven demonstrate how students wedded the archive’s content with research and composition, weaving aspects of hymn, anthem, spoken word, and protest song into their multigenre assemblages. Students’ South Los Angeles sounds from streets, parks, homes, and gatherings announces the lived occupation of the neighborhood—from conversations on the Vermont bus to a parent’s sharp reminder for a younger sister to do her homework.

As a coda to the students’ work, a guest digital composer, Spectral Acoustic, stitched all 58 scavenged sounds into the twelfth single of the album, “Never Say Die.”Footnote41 Spectral Acoustic’s production conveys the openness of the sonic archive—the accumulation of scavenged environmental sound gives South Los Angeles material audibility and plasticity. The piece surfaces unpredictable unities through its primary use of found sounds, with compositional moves restricted to arrangement and nonhuman musical phrases, strangely conscripting ambience itself as a storytelling voice. “Never Say Die” makes music out of the ambivalence of sonic sources. Thus, as a contrapuntal response to the students’ singles, the piece foregrounds the poetics of recursive listening as the conditions for the work itself.

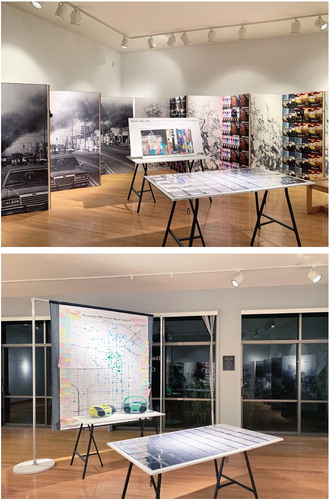

Sounds into space: “LA 1992/London 1780: Sounding Out a Crowd”

If the album demonstrates the way students produced a counterimaginary through a fabulated soundscape of South Los Angeles in 1992, then the exhibition and installation built for the project are memorials in space. As Klein explains, urban imaginaries are actually forms of erasure through fiction, “collective [memories] of an event or place that never occurred but [are] built anyway.”Footnote42 If the prevailing imaginary of South Los Angeles from the 1992 media-complex is actually an ongoing “selective forgetting” of the neighborhood’s inhabitants, the daily-lived history of struggle against disinvestment, racist housing policies, and police violence, then a counterimaginary intervenes by building students’ “fictions” into fact by manifesting their collective memory in space.Footnote43

In the exhibition, listening panels juxtapose two images of civil unrest from the linked cities under study (). Interlaced between a cut-up of the images are panels that hold headphones for visitors to listen to the completed album. Cover art designed by students are wheat-pasted and tiled in between to contrast with unifying images on either side. In this manner, the listening panels stage the listener’s experience of the album amid a fragmented visual language that evokes the task of collecting and reassembling perspectives.

Figure 5. Exhibition of “LA 1992/London 1780: Sounding Out a Crowd” juxtaposing two images of civil unrest from the cities studied. The fragmented images emphasize the reconstruction of perspective, while the tiled album cover art designed by students punctuates the listening stations situated between successive panels. Scavenged sounds could be selected as individual CDs and played on a boombox, while another stereo filled the room with “Never Say Die,” the final track of the collective album.

Accompanying the listening panels, an installation of 60 CDs addresses the problem of giving the sonic archive a physical form. To concretize the archive in space, the exhibition design turns to the near-obsolete form of the audio compact disc as a material reference to the sound technology of the early 1990s. Each individual sound becomes a self-contained material record within the archive, complete with a written disc and accompanying liner notes featuring a hand-drawn “thick” map to demonstrate the layers of history students uncovered at the site of retrieval.Footnote44 When the CD cases are closed, however, they relinquish their individuality, forming an image of a raven as a reference to Grip from Barnaby Rudge, the protagonist’s pet bird (). The CD installation balances the aim of coherence—producing an understandable whole, with the aim of singularity—highlighting each sound’s palimpsest of investigations in producing the corpus of a remembered city.

Sounds into place: “Resounding 1992: A Sonic Map of South Los Angeles”

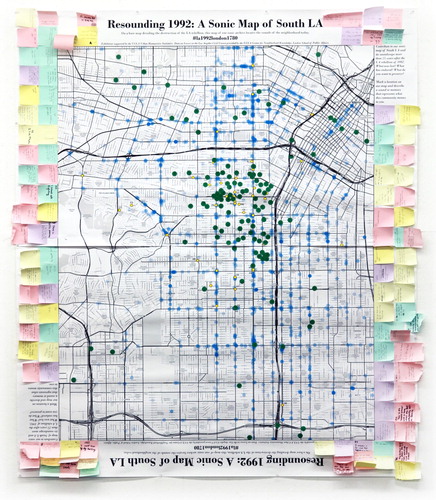

In this final use of the archive, we juxtapose the sound archive with the spatial technology of mapping. Knowing that cartographic representation is subtended by the logic of colonial surveillance, we counter such an agenda with our sonic map. In the map, students geolocated sounds (yellow), and superimposed them on a base map of reported damages from the 1992 Rebellion (blue). A large table version invited visitors to add sonic memories (green), and 116 descriptive Post-it notes feathered the map in response to the prompt ():

Contribute to our sonic map of South LA and its soundscape more than 25 years after the LA rebellion of 1992. What was lost? What has endured? What do you want to preserve? Mark a location on our map and describe a sound or memory that represents what this community means to you.Footnote45

Figure 7. Large map of the scavenged sounds that situated the archive while opening up a community of listeners as students shared their findings and collaboratively mapped with visitors their own recollections of 1992.

Figure 8. Community annotations feathering the map with Post-it notes relating remembered city sounds located by green dots upon the students’ scavenged archive (yellow) and data on damages in the civil unrest (blue).

101: W 37th St/You wouldn’t know it unless you did, quiet until its loud. Lost its unity

98: The Area near my house/Sound: silence or sirens

119: A sound that I heard at that place was that I heard someone got shot at the liquor store

174: I saw police men beating a African AmericanFootnote47

This lays the groundwork for the way the sonic map invokes the ethical dimension of “curation” in the original sense of the word:

the original etymology of the term curation [means] “care of souls” or, in some cases, “stewardship of the dead.” [These maps] sought to curate—care for, preserve, document, and archive … despite (or perhaps because of) the precarious material, social, and technical conditions of possibility for the very stories.Footnote48

Album, exhibition, and map—while the products of our pedagogy are aesthetic, they are first vectors of public space. The audience and artist we have in mind is not the postmodern subject-as-urban listener whose headphones and curated playlists signal a withdrawal from urban space through “aestheticizing a private world … whilst the contingent nature of urban space and the ‘other’ is denied.”Footnote50 Instead, sonic scavenging and its outputs as we have laid out here reverses this procedure, embedding the listener-creator in the environment that prioritizes the collective sharing of space, rather than atomizing one’s occupation of it. The technology and learning objectives our pedagogies assemble ask students not just to mediate space, or make media about space, but rather to seize the cultural means of producing it.

Conclusions

One of the main insights in Derrida’s “Archive Fever” is the way the archive, as a technology for extending memory, is “not only the place for stocking and for conserving an archivable content of the past which would exist in any case,” but instead a process that generates precisely what can be preserved and for what ends.Footnote51 He writes: “the technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future.”Footnote52 Taking up this suggestion, we summarize this essay’s focus on the creation of sonic archives as a pedagogy of critical communication because of three main rationales.

Sound scavenging extends the expressivity of space

This pedagogical sequence demonstrates that environmental sound scavenging generates communicative possibilities of space. Field recordings propel participants into the environment, entangling the text with the body in transforming students into listening occupants of the city. By scavenging sounds, students challenge the text’s overdetermined status while conferring “listen-ability” to the urban environment. Instead of treating the urban environment as a field of indifferent noise, our pedagogy imagines a means to endow that field with value through the constitution of students as sound scavengers.

Sound scavenging challenges the hegemonic constructions of space

Sound scavenging enables students to make relations outside the purview of commerce, work, private domesticity, and so on. Created by occupying public space and for a public, our pedagogy teaches students alternate reasons for being in the city—to record, to document, to memorialize, to connect. Unlike traditional archives, these sounds are not evidence of the past, but of the archiving process itself, of the intention to preserve, which speaks loudly about the unevenness of spatial technologies that memorialize some histories and erase others.

Sound scavenging brings communities into relation with each other and with history

These projects highlight the waywardness of agency in community formation. The randomness, contingency, and lack of instrumentality for what is produced reveal the community’s raison d’être in collecting and collectivizing. In foregrounding the scavenging instinct, the need to be present, to stop and proceed at will, to call value into existence where others have failed to, or refuse to look, the sound archives we produced and the products we made from it are evidence of a repertoire of aleatory methods for assembling a transhistorical, transurban space. Rather than creating stable relations between how things are and how they came to be, this is a pedagogy that makes relations where none seem to exist, and from there, to notate and understand them so that spatial-historical accounts include all who contribute to its making.

Burned sounds: a coda

And every night … he’s broad awake, talking to himself, thinking what he shall do to-morrow, where we shall go, and what he shall steal, and hide, and bury. Charles Dickens, Barnaby RudgeFootnote53

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” trans. Eric Prenowitz, Diacritics 25, no. 2 (1995): 9.

2 Norman M. Klein, The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory (New York: Verso, 2008), 13.

3 Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City,” in Writings on Cities, ed. and trans. Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999), 147–59. See also David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” New Left Review 53 (2008): 23–40. Lefebvre proposed the “right to the city” as the “transformed and renewed right to urban life” of those who “inhabit” the city (158). Harvey elaborates Lefebvre’s formulation, stressing that the right to the city is a collective and productive-transformative power over space: “The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city” (23).

4 Walter Benjamin, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 4, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael William Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2006), 48 emphasis added.

5 Giorgia Aiello and Matteo Tarantino, “Introduction: Communicating the City between the Centre and the Margins,” in Communicating the City: Meanings, Practices, Interactions, ed. Giorgia Aiello, Matteo Tarantino, and Kate Oakley (New York: Peter Lang, 2017), xiii–xxviii.

6 Greg Dickinson and Brian L. Ott, “Spatial Materialities: Coproducing Imaged/Inhabited Spaces,” in Communicating the City: Meanings, Practices, Interactions, ed. Giorgia Aiello, Matteo Tarantino, and Kate Oakley (New York: Peter Lang, 2017), 43.

7 Charles Baudelaire, “The Ragpickers’ Wine,” trans. C. F. Macintyre, Poetry Foundation, n.d., https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/54376/the-ragpickers-wine; Guy Debord, “Theory of the Deríve,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2007), 62–66. For Debord, the dérive also designates sets of “playful-constructive” behaviors that emerge from “dropping our usual motives for action or movement” (62).

8 Laura Grace Ford, Savage Messiah (New York: Verso, 2010); Charles Dickens, Barnaby Rudge (New York: Penguin, 2012).

9 Benjamin, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” 8.

10 Ford, Savage Messiah.

11 Laura Grace Ford, Laura Grace Ford (blog), n.d., http://lauragraceford.blogspot.com; Laura Grace Ford (SoundCloud), n.d., https://soundcloud.com/laura-oldfield-ford.

12 “Laura Oldfield Ford: Alpha, Isis, Eden,” (exhibit, The Showroom, London, February 1, 2017—March 18, 2017), http://www.theshowroom.org/exhibitions/laura-oldfield-ford-alpha-slash-isis-slash-eden.

13 R. Murray Schafer, “The Soundscape,” in The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Jonathan Sterne (London: Routledge, 2012), 101.

14 Michel Chion, “Three Listening Modes,” in The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Jonathan Sterne (London: Routledge, 2012), 48.

15 Ibid.

16 Greg Dickinson and Giorgia Aiello, “Being through There Matters: Materiality, Bodies, and Movement in Urban Communication Research,” International Journal of Communication 10 (2016): 1304.

17 Laura Grace Ford, “Drift Report from Downtown LA,” Journal of Writing in Creative Practice 10, no. 2 (2018): 215–25. Excerpts for this essay are from Ford’s earlier manuscript, “LOS ANGELES//LONDON—1934/1965/1972/1992/2003/2020” (unpublished manuscript, September 23, 2018), n.p.

18 Roland Barthes, S/Z: An Essay, trans. Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1974).

19 Guy Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2007), 11.

20 Guy Debord, “Preliminary Problems in Constructing a Situation,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2007), 43–44. Debord defines a “situation [as] an integrated ensemble of behavior in time. It is composed of actions contained in a transitory decor” (43).

21 Dickinson and Aiello, “Being through There Matters,” 1305.

22 Dickinson and Ott, “Spatial Materialities,” 32.

23 Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” 10.

24 Jacqueline Barrios and Kenny Wong, “Data from: LA//London Summertime Playlist September 23, 2018, Playlist Archive,” (dataset). Data available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

25 Michael Bull, “The Audio-Visual iPod,” in The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Jonathan Sterne (London: Routledge, 2012), 197–208. Bull’s use of temperature is a useful metaphor for the kinds of effects a sonic archive achieves, noting the “chill of city spaces, which are perceived as inhospitable, without the warmth of desired communication” (202). Debord sees psychogeography as rendering the “objective passional terrain of the dérive” available to analysis (“Theory of the Deríve,” 51).

26 Dickinson and Ott, “Spatial Materialities,” 32.

27 Barrios and Wong, “Data from: LA//London Summertime Playlist September 23, 2018, Playlist Archive.”

28 Baruch Spinoza, Ethics: Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect and Selected Letters (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 1992), qtd. in Dickinson and Ott, “Spatial Materialities,” 35.

29 LitLabs Studios, “1_TacoBellParkingLot_Vermont&Slauson (J_Antonio),” SoundCloud, January 28, 2019, https://soundcloud.com/litlabsstudios/1_parking-lot-at-taco-bell_vermont-and-slausonj_antonio?in=litlabsstudios/sets/southlasonicarchive. See also LitLabs Studios, “South LA Sonic Archive: The Found Sounds of Never Say Die,” SoundCloud, January 28, 2019, https://soundcloud.com/litlabsstudios/sets/southlasonicarchive; Jacqueline Barrios and Kenny Wong, “Data from: LA 1992/London 1780: Sounding Out a Crowd Exhibition, January–September Archive,” (dataset). Data available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

30 Richard Winton, “For 25 Years, the Burned Remains of a Teenager Found During L.A. Riots Was a Mystery. Now, the Cop Who Found Him Has the Answer,” Los Angeles Times, May 23, 2017, https://www.latimes.com/la-me-ln-app-riots-john-doe-20170523-story.html.

31 Dickens, Barnaby Rudge, 58.

32 Georg Lukács, The Historical Novel, trans. Hannah Mitchell and Stanley Mitchell (Boston: Beacon, 1963), 34.

33 Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (London: Routledge, 1989), 383.

34 Lukács, The Historical Novel, 36.

35 Guy Debord, “Definitions,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2007), 51–52.

36 LitLabs Studios, “South LA Sonic Archive: The Found Sounds of Never Say Die,” SoundCloud, January 28, 2019, https://soundcloud.com/litlabsstudios/sets/southlasonicarchive.

37 LitLabs Studios, “Never Say Die: A Sonic Tribute to the LA 1992 Rebellion,” SoundCloud, January 21, 2019, https://soundcloud.com/litlabsstudios/sets/never-say-die.

38 Dickens, Barnaby Rudge, 522.

39 LitLabs Studios, “through my mother’s eyes—Her Children,” SoundCloud, January 31, 2019, https://soundcloud.com/litlabsstudios/through-my-mothers-eyes-her?in=litlabsstudios/sets/never-say-die.

40 LitLabs Studios, “Only God Can See Us—Los Perros Mojados,” SoundCloud, February 1, 2019, https://soundcloud.com/litlabsstudios/only-god-can-see-us-los-perros?in=litlabsstudios/sets/never-say-die.

41 LitLabs Studios, “Never Say Die—Spectral Acoustic,” SoundCloud, February 1, 2019, https://soundcloud.com/litlabsstudios/never-say-die-spectral?in=litlabsstudios/sets/never-say-die.

42 Klein, The History of Forgetting, 10.

43 Ibid., 16.

44 Todd Samuel Presner, David Shepard, and Yoh Kawano, HyperCities: Thick Mapping in the Digital Humanities (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

45 Barrios and Wong, “Data from: LA 1992/London 1780: Sounding Out a Crowd Exhibition, January—September Archive.”

46 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 27.

47 Barrios and Wong, “Data from: LA 1992/London 1780: Sounding Out a Crowd Exhibition, January—September Archive.” Responses are transcribed as written.

48 Presner, Shepard, and Kawano, HyperCities, 148.

49 Klein, The History of Forgetting, 11.

50 Bull, “The Audio-Visual iPod,” 207.

51 Derrida, “Archive Fever,” 17.

52 Ibid.

53 Dickens, Barnaby Rudge, 61.

54 Ibid., 688.