Introduction

Opioid analgesics, such as morphine and oxycodone, are frequently prescribed for pain management. Widespread prescribing and misinformation about the habit forming potential of opioids have contributed to the increase of preventable morbidity and mortality in the last two decades. This led to the declaration of a public health emergency in the United States in October of 2017 (Citation1). Over 67,000 people died of drug overdose in 2018, with opioids being involved in 69.5% of them (Citation2). The economic burden of prescription opioid abuse is also substantial, with approximately $78.5 billion per year being spent toward healthcare costs, addiction treatment, and criminal justice costs, among other expenses (Citation2–3). The opioid epidemic has resulted in increased emphasis on stewardship practices within the healthcare system.

Opioid stewardship, while having no formal definition thus far, has been described as “a set of interventions implemented to improve prescribing, mitigate adverse events, and monitor the use of opioids” (Citation4). The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) provides a similar definition of “coordinated interventions designed to improve, monitor, and evaluate the use of opioids in order to support and protect human health" (Citation5).

In 2018, The Joint Commission implemented new standards for accredited hospitals, focusing on safe opioid prescribing and monitoring of patients (Citation6). Many key principles of opioid stewardship are reflected in these standards, including the need for a leadership team and availability of nonpharmacological treatments. The standards also emphasized the need for creating and analyzing quality improvement metrics to increase patient safety, and monitoring opioid use, adverse events and prescribing. The comprehensive approach outlined by The Joint Commission provides a framework for accredited hospitals to develop opioid stewardship protocols and practices.

Pharmacists have been identified as a member of the multidisciplinary healthcare team that can further the goals of opioid stewardship (Citation7). Pharmacists can obtain specialized training in pain management and palliative care to further become subject matter experts in the pharmacology and treatment of pain syndromes. There are currently 26 Post Graduate Year 2 (PGY2) Pharmacy Residency programs specializing in Pain Management and Palliative Care (PMPC) accredited by the American Society of Health Systems Pharmacists (ASHP), which train pharmacists to integrate into the healthcare team and contribute to complex treatment regimens (Citation8).

Poirier et al. (Citation9). showed benefit in multiple areas after implementation of a pharmacist-directed pain management service. Patient satisfaction scores improved alongside a decrease in overall opioid utilization, decrease in opioid-induced rapid response team (RRT) events, and estimated annual indirect cost avoidance of $1.5 million to $1.8 million per year. Given the benefits of opioid stewardship reported in literature, this editorial aims to describe the current state of integration of opioid stewardship within the active accredited ASHP PGY2 PMPC Pharmacy Residency programs.

Body

Section 1: Survey characteristics

This was a descriptive survey of opioid stewardship principles implemented in active ASHP PGY2 PMPC Pharmacy Residency programs. The survey was composed of three sections including 1) Demographics 2) ASHP PGY2 PMPC pharmacy resident involvement in institution opioid stewardship practices 3) Barriers with institution opioid stewardship practices.

Close-ended questions were used to define participant characteristics and opioid stewardship practices. The institution setting type was a multiple response question, where the survey participants can pick and group identifiers that best describe their institutions. Concentration of the PGY2 PMPC Pharmacy Residency program was defined as the setting where the PMPC pharmacy resident spent >50% of rotational experiences. The opioid stewardship practices included in this survey reflect the high-level overview of recommendations from The Joint Commission and the National Quality Forum Playbook. Open response questions were used to elicit barriers with institution opioid practices.

Surveys were developed using QualtricsXM. The surveys were distributed via email to the active, accredited and candidate ASHP PGY2 PMPC Pharmacy Residency program director and pharmacy resident(s) in the United States.

Section 2: Results

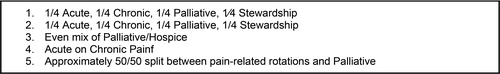

A total of 41 survey responses were attempted, and 20 were completed. summarizes the baseline characteristics of the participants. The majority of the institutions were described as a healthcare system (15%), academia-affiliated (11%), and nonprofit (12%). Participants were from institutions in the Midwest (45%), Southeast (25%), Northeast (15%) and West (15%) United States regions. Only half of the participants confirmed the institution has an established opioid stewardship program. 61% of the participants indicated that the PMPC pharmacy resident is actively involved in the opioid stewardship program. The concentration of the PGY2 PMPC program varied among programs, with 40% of programs focused on malignant and nonmalignant chronic pain while 35% focused on hospice and palliative care. 25% of the programs stated that they offered equal experiences in acute and chronic pain, palliative care and opioid stewardship. describes additional responses to concentration of the PGY2 PMPC Pharmacy Residency programs.

Table 1. Participant baseline characteristics.

Most of the participants responded “Yes” to indicate that the PMPC pharmacy resident is involved meet the majority agreement rates, which was defined as >90% rate in ‘yes’ response. These measures were 1) Does your practice have a prescription take-back program?, 2) When patients are discharged on opioids, is the current PMPC pharmacy resident involved in their transitions of care planning in most of the opioid stewardship quality measures (Appendix A, Supplementary material). Only three measures did not?, and 3) Does the current PMPC pharmacy resident employ a validated screening tool (e.g. SOAPP-R, COMM, ORT, PHQ-9) to routinely identify high risk patients for misuse?.

Section 3: Barriers

The survey included an open response question where participants expressed perceived barriers to implementation of an opioid stewardship program. More than 50% of responses indicated that cost/funding, time, and lack of full-time equivalent (FTE) are prominent barriers. Other responses included “discoordination of care”, “no barriers”, and “not applicable in the hospice practice setting”.

Discussion and conclusion

The differences in the agreement rates could be attributed by multiple factors. One important factor to consider is that these measures may not be applicable to all healthcare settings. For example, screening tools such as COMM, ORT, SOAPP-R are developed to be used in an outpatient setting to evaluate long-term risks and efficacy of opioid therapy. Therefore, PMPC pharmacy programs that focus more in inpatient settings or hospice care may not allow the pharmacy resident the same opportunity to utilize these tools. Conversely, if the PMPC pharmacy program is mainly focused in the outpatient clinic, the pharmacy resident may not have ample opportunity to get involved in opioid stewardship practices performed at discharge. Another consideration is that many pharmacist interdisciplinary inpatient roles are in specialty consult teams, such as acute pain or palliative care services, that may not be as involved in transitions of care as the general floor medical teams. Additionally, they may not be involved in drug take back programs. Drug take back programs are typically located at an outpatient pharmacy, but hospice programs or ambulatory clinics that may be independent from a hospital will not have the same access available. Geographical considerations should be noted as this can affect availability as well.

Despite the discrepancies in survey responses, there is unanimous acknowledgement of the importance of pharmacist involvement in opioid stewardship across different settings. Pharmacists can provide valuable clinical and operational expertise to the interdisciplinary team that can influence healthcare system/hospital formularies, adverse event monitoring programs and others (Citation4, Citation7). Survey results identified the biggest barriers to pharmacist involvement is personnel and time compensation. Opioid stewardship practices may involve heavy administrative and timeline-oriented projects, therefore ensuring protected time is crucial. One solution to maintain opioid stewardship personnel and protected time is utilizing PMPC residents. It can provide adequate experience to meet the following ASHP educational outcome requirements: 1) R1 requirement: leadership and practice management skills 2) R3 authoritative resource on the optimal use of medications in pain and palliative care (Citation8). Furthermore, this will present as an opportunity to develop necessary skills and approaches to interdisciplinary collaboration. PMPC residents may engage in these efforts in a longitudinal or block-based rotation.

Limitations

There may be possible limitations in this study. Selection bias is often unavoidable. Only participants who completed the survey were included in the results. Response rates for this survey were low, therefore there is the potential for non-response bias. An additional demographic question to differentiate between the PMPC Pharmacy Residency program director and pharmacy resident was added after surveys had been distributed, and in turn not all of respondents completed this question. In an effort to reduce chance of respondent fatigue, the survey did not include all of the elements of an opioid stewardship practice. There is a need for future research with revised methods for data collection to include these missing elements.

Conclusion

As the opioid epidemic continues to impact healthcare institutions, there is a strong need for full time pharmacist involvement in institutional opioid stewardship efforts. Implementation remains a challenge due to the lack of funding and FTE, however PMPC pharmacy residents could provide additional support. This descriptive survey reviewed the current state of integration of opioid stewardship within PMPC Pharmacy Residency programs. Incorporating opioid stewardship activities may present a unique educational opportunity for the PMPC pharmacy resident to expand their leadership, project management, and interprofessional skills, while providing a weighted pharmacy presence in interdisciplinary committees. PMPC Pharmacy Residency programs require the pharmacy resident to dedicate most of their time to other learning experiences, therefore they could not commit to this role full time. Consequently, this would only provide a temporary solution to the need for a full time pharmacist and justification for a FTE for institutional opioid stewardship efforts is still warranted.

Disclaimer

The author’s affiliated institutions were not involved in the development or interpretation of this survey and the content is reflective of the authors’ view.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Tanya Uritsky, PharmD, BCPS, from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, for providing ongoing support and reviewing this editorial.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Acting Secretary Declares Public Health Emergency to Address National Opioid Crisis. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/10/26/hhs-acting-secretary-declares-public-health-emergencyaddress-national-opioid-crisis.html.

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief No. 356. 2020;1–8. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db356.htm

- Florence C, Luo F, Rice K. The economic burden of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose in the United States, 2017. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;218:108350. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108350.

- Ardeljan LD, Waldfogel JM, Bicket MC, Hunsberger JB, Vecchione TM, Arwood N, Eid A, Hatfield LA, McNamara LAnn, Duncan R, et al. Current state of opioid stewardship. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(8):636–43. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa027.

- Opioid Stewardship. Accessed October 4, 2020. https://www.ismp-canada.org/opioid_stewardship/.

- The Joint Commission. Joint commission enhances pain assessment and management requirements for accredited hospitals. The Joint Commission. 2017;1–7.

- Uritsky TJ, Busch ME, Chae SG, Genord C. Opioid stewardship: Building on antibiotic stewardship principles. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2020;34(4):181–183. doi:10.1080/15360288.2020.1765066.

- Required competency areas, goals, and objectives for postgraduate year two (PGY2) pain management and palliative care pharmacy residencies. American Society of Healthcare System Pharmacists. 2018;1–29. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/professional-development/residencies/docs/pgy2-pain-management-palliative-care-cago-2018.ashx.

- Poirier RH, Brown CS, Baggenstos YT, Walden SG, Gann NY, Patty CM, Sandoval RA, McNulty JR. Impact of a pharmacist-directed pain management service on inpatient opioid use, pain control, and patient safety. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(1):17–25. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxy003.