Abstract

Treating palliative cancer patients with antithrombotics is challenging because of the higher risk for both venous thromboembolism and major bleeding. There is a lack of available guidelines on deprescribing potentially inappropriate antithrombotics. We have therefore created an antithrombotics scheme to aid in (de)prescribing antithrombotics. A retrospective single-center clinical cohort observational study was performed to evaluate it. Patients with solid tumors with a life expectancy of less than 3 months seen by the palliative team were included. Comparisons were made between patients who were treated according to the antithrombotics scheme and those who were not. 47.6% of patients used antithrombotics. One hundred and eleven patients were included for analysis. Most patients used antithrombotics according to the scheme (n = 80, 72.1%). Eleven patients experienced a clinical event, seven patients in the scheme adherence group (9.9%) and four in the no scheme adherence group (13.8%), which was not statistically significant (p = 0.726). The higher frequency of clinical events in the group without scheme adherence suggests that (de)prescribing antithrombotics according to the antithrombotics scheme is safe. The results of this study suggest that the antithrombotics scheme could aid healthcare professionals identifying possible inappropriate antithrombotics in palliative cancer patients. Further prospective research is needed to investigate this tool.

Introduction

Palliative cancer patients are a highly vulnerable population, that should receive medical treatment focused more on maximizing quality of life rather than curing disease. Treatment in palliative cancer patients should be reevaluated to identify potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), where the benefits no longer outweigh the risks. In general, most preventive medications with long-term benefits can be considered PIMs for patients nearing the end of their life (e.g., medication for primary prevention) (Citation1–4). However, in the case of secondary prevention, some of these medications are not considered PIMs. Therefore, deprescribing them can be a complicated process, in which many factors (e.g., patient characteristics and risk factors, medical history, prognosis and patient wishes) should be taken into consideration (Citation1, Citation3). Also, the use of antithrombotic medication in these patients should be assessed both for risk and effectiveness (Citation4). Using anticoagulants in cancer patients can be challenging because these patients have a four to seven times higher risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE) or cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) than non-cancer patients, but they also have a higher risk of anticoagulation-associated bleeding (Citation5–9). A study performed by Huisman et al. that retrospectively analyzed the use of antithrombotics in the Netherlands, discovered that 60% of patients used antithrombotics in the last 3 months of life. They were often continued until shortly before death (Citation5). However, guidelines on deprescribing antithrombotics in palliative cancer patients are sparse. For example, the OncPal guideline and the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy (STOPPFrail) do formulate a recommendation regarding deprescribing antithombotics in palliative cancer patients (Citation10–11). However, both do not cover a broad range of antithrombotics (only acetylsalicylic acid). In addition, both guidelines were never prospectively tested in palliative cancer patients. Thus, no consensus regarding deprescribing (how and when) of antithrombotics in palliative cancer patients has been reached (Citation5, Citation12).

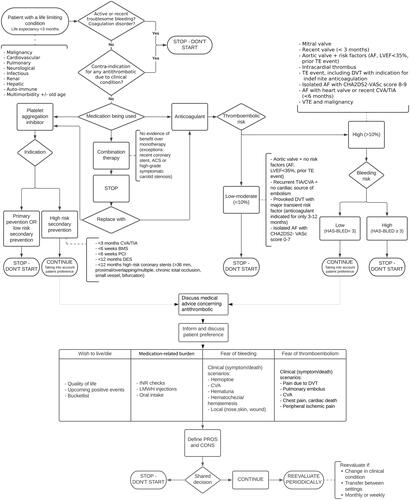

To address the need for specialized clinical guidelines, palliative specialists in the Amsterdam UMC hospital together with Erasmus MC have created a tool, the antithrombotics scheme, to aid health care professionals in considering different factors when deprescribing antithrombotics in patients in a personalized way with a life expectancy of less than 3 months, (Citation13). This scheme considers multiple factors, such as type of medication, CHA2DS2-VASc (Citation14) and HAS-BLED score (Citation15), the indication of the antithrombotic medication, time since the last (thromboembolic) event and the presence of different types of heart valves. Most importantly, the scheme also takes into consideration the patient’s preference which is discussed during a palliative consultation (Citation13). Application of the antithrombotic schema in clinical practice has not been studied so far.

Figure 1. The antithrombotics scheme.

Derived and adapted with permission from Huisman BAA (Citation13).

ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome; AF: Atrial Fibrillation; BMS: Bare Metal Stent; CVA: CererbroVascular Accident; DES: Drug-Eluting Stent; DVT: Deep Venous Thrombosis; INR: International Normalized Ratio; LMWH: Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; TAVI: Trans Catheter Valve Implantation; TE: Thrombo Embolism; TIA: Transient Ischemic Attack; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.

For the valves, several items should be taken into account to determine if a valve results in high or low risk:

High risk: (items regarding valves): Atrial fibrillation with mechanical heart valve; For biological valves (including TAVI) placed < 3 months ago, Mechanical heart valve in mitral, tricuspidal or pulmonary position; Aortic valve prostheses with additional risk factor in consultation with the surgeon; Heart valve prosthesis (including biological valve) with additional risk factor *; Mechanical heart valve old model: caged ball, tilting disk (Starr-Edwards, Björk-Shiley)

Low risk: (items regarding valves): Mechanical heart valve in aortic position > 3 months ago placed without additional risk factor *; Biological valve > placed 3 months ago.

* Risk factors include: atrial fibrillation, left ventricular ejection fraction< 35%, history of thromboembolism.

This research aims to retrospectively analyze the use of the deprescribing scheme for antithrombotics in palliative cancer patients with solid tumors in Amsterdam UMC. The first aim is to determine how many patients with solid tumors who were seen by the palliative support team were prescribed antithrombotics. The second aim is to identify in how many patients antithrombotics were deprescribed or continued conform and non-conform the antithrombotics scheme. The third aim is to compare differences in clinical outcomes between patients that were treated according to the antithrombotics scheme and those who were not.

Materials and methods

Design

The study was designed as a retrospective single-center clinical cohort observational study. Patients from Amsterdam UMC were eligible for inclusion if they were 18 years or older, had an active solid malignancy, a short life expectancy (<3 months) as assessed by the treating oncologist, and used antithrombotic medication when the palliative support team was first consulted. All patients of one calendar year: 2021, that met these criteria were included. Exclusion criteria were: hematological malignancy, alive at the time of analysis or lost to follow-up with an unclear prognosis (not clearly stated or derived from patients’ files). Hematological malignancy was excluded because in this group, life expectancy is far more difficult to define as <3 months or >3 months. Eligible patients were sought in the electronic patient files EPIC (EPIC, Verona, WI, USA).

Data collection

Electronic patients’ files were reviewed manually. The demographic variables age and gender were collected. Other variables for the antithrombotics scheme (see ) included type of antithrombotic(s), number of antithrombotics used per patient, the indication the antithrombotics were used for if noted in the patient files, type of tumor, tumor localization, comorbidities (cardiovascular or VTE history), CHA2DS2-VASc score (2 categories: 0–7 and 8–9), HAS-BLED (2 categories: 0–2 and 3 and higher) and smoking history. All variables stated above were coded as categorical variables. Furthermore, date of first consultation and date of death were collected. The prescription and deprescribing of antithrombotics medication, after contact with the palliative support team, was retrospectively reviewed using the antithrombotics scheme and classified as adherent to the scheme or non-adherent to the scheme. An event was defined as the occurrence of major bleeding or VTE. Variables were predefined but some were adjusted during this research (Appendix A). The variable renal failure was determined in consultation with the nephrology department of Amsterdam UMC, resulting in a conservative definition of < 30 eGFR (Citation16, Citation17). Because we included patients suffering from oncological diseases, the majority has a history of medication that can alter blood counts, therefore, the definition of thrombocytopenia was set to < 100 × 10^9/L, instead of < 150 × 10^9/L. All data were collected in an Excel database (Excel version 2016, Microsoft, Redmond, USA).

Data analysis

All patient data were analyzed first by the principal investigator to determine if the antithrombotics scheme was applied correctly or not. An independent clinical pharmacist reviewed the data. Discrepancies between the findings of the principal investigator and the clinical pharmacist were reviewed by a third clinical pharmacist to reach a consensus. Clinical consultation was obtainable from two palliative care doctors from the anesthesiology department when the electronic patient files required clinical clarification. The patients were divided into two cohorts: (1) use of antithrombotics conforming to the antithrombotics scheme, labeling this group as “scheme adherence yes” and (2) use of antithrombotics non-conforming to the antithrombotics scheme, labeling this group as “scheme adherence no.” IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corp., Chicago, USA) was used for descriptive statistics on the patient population. A Fisher’s exact test was conducted to identify and analyze potential differences in clinical outcomes between the two patient cohorts. A p-value < 0.05 was set as statistical significance.

Results

A total number of 319 patients that received palliative care in Amsterdam UMC in 2021 were identified. From this cohort, 152 palliative care patients who had both solid tumors and used antithrombotics whilst in consultation with the palliative support team, met the inclusion criteria (47.6%). However, 41 of these patients had to be excluded (see Appendix B for the patient inclusion/exclusion flowchart), the most dominant reason being an unclear prognosis in the electronic patient’s files, making retrospective analysis impossible (n = 17). Thus, 111 palliative care patients were included (). The median age of the study population was 70 years (range 28–92 years). Most patients had primary solid tumors located in the digestive tract (51.3%) and received systemic oncological treatment shortly (days to weeks) before receiving palliative care (72.1%). 41.4% of the patients had a history of VTE and 27.9% had a history of major bleeding. 79.3% of the patients had only one antithrombotic medication, with the most prescribed antithrombotic group being low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs). Most patients (lost to follow-up excluded) were first approached by the palliative support team within just 15 days of their death.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Eleven patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded when analyzing the clinical outcomes, resulting in 100 patients remaining for this analysis. In the patient group with scheme adherence (n = 71), a major bleeding event occurred in two patients and VTE occurred in five patients, resulting in seven out of 71 (9.9%) patients experiencing a clinical event. The median time until event (after the first palliative care consultation) in this group was 56 days. In the patient group without scheme adherence (n = 29), a major bleeding event occurred in three patients and VTE occurred in one patient, resulting in four out of 29 patients experiencing a clinical event after being in contact with the palliative support team (13.8%). The median time until events (after the first palliative care consultation) was 31 days. Fisher’s exact test yielded that the differences in clinical events were not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.726 (2-sided significance). The Odds Ratio of experiencing a clinical event in the non-scheme adherence group as compared to the scheme adherence group was 1.46 (95% confidence interval 0.39–5.44) which was not statistically significant.

We further analyzed the patients with clinical events after first consultation with the palliative support team (n = 11) and the use of antithrombotics within this subset of patients. Firstly, the clinical events in the patients with scheme adherence and the (de)prescription patterns in these patients were investigated. In two patients in which antithrombotics were deprescribed, a VTE occurred. Surprisingly, a VTE also occurred in three patients in whom antithrombotics were continued. In one patient, a major bleeding event occurred after stopping antithrombotic medications and in another patient a major bleeding event occurred after starting antithrombotic medication. Secondly, the patients without scheme adherence and their (de)prescription were analyzed. In one patient a VTE occurred after continuing antithrombotic medication. Furthermore, a major bleeding event occurred in three patients after continuing antithrombotics non-conform the antithrombotics scheme. An outline of all patients with clinical events is given in .

Table 2. An overview of antithrombotic use and outcome in all patients experiencing clinical events after consultation with the palliative support team.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the use of the antithrombotics scheme developed in Amsterdam UMC and Erasmus MC for evaluation of appropriateness of antithrombotics in palliative cancer patients with solid tumors. We found that almost half of the palliative cancer patients used one or more antithrombotics (47.6%). In almost three-quarters of patients the antithrombotics scheme was applied properly, showing that the use of antithrombotics is critically reviewed to reduce PIMs. Fewer clinical events were seen in the group who was (de)prescribed conform the antithrombotics scheme as compared to the group without scheme adherence, 9.9% and 13.8% respectively, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The prevalence of antithrombotic use of 47.6% we found is comparable to the MEDILAST study that found that 60% of palliative care patients (including both malignancy patients and non-malignancy patients) were prescribed antithrombotics. In the MEDILAST study, LMWHs were also the most prescribed group of antithrombotics (Citation5). The relatively high frequency of antithrombotic use in palliative cancer patients can be explained by reduced motility in these patients, as well as the presence of previous coagulation disorders and advanced age (Citation18, Citation19). Furthermore, a previous study by Noel-Savina et al showed that 6 months after deprescribing vitamin K antagonists (VKA) or tinzaparin there was no significant increase in the risk of VTE, major bleeding and death compared to patients still on VKA or tinzaparin, indicating that other factors could contribute to the occurrence of clinical events (Citation20). This might well be a reflection of the inherently increased risk for both bleeding and thrombotic events in patients with advanced cancer, underpinning the need for a tool or guidance document to aid health care professionals on assessing the risk and benefit of (de)prescribing the antithrombotic medication of their patients.

Limitations to our study were that it was performed retrospectively in a single-center and depended on prior documentation in the electronic patients’ files. The documentation of the prognosis regarding life expectancy and of the decision-making regarding the use of antithrombotics was not homogeneous and sometimes poor. The subjective nature of this research was minimalized as much as possible by the use of a second independent assessor for all patient cases and a possible third assessor for complex patients. Furthermore, a recurrent trend found was that the palliative support team was called upon for consultation rather late into the palliative phase. Therefore, a short period until death remained to evaluate the outcome after a medication review.

To our knowledge, this was the first research analyzing the use of a deprescribing scheme for antithrombotic medication in palliative cancer patients. The study population was relatively small, but the results suggest that the scheme could be a useful tool to optimize the use of antithrombotics in palliative cancer patients. A future elaboration of the current antithrombotics scheme with advice on which antithrombotic should be (de)prescribed first in patients with combination therapy, would be of added benefit. Future prospective research is still needed though to analyze and validate the antithrombotics scheme, and to investigate if the timing of first palliative consultation can influence the occurrence of thrombotic or bleeding events. In the current retrospective dataset, we noted that the palliative care team was most often consulted within just 15 days of death.

In conclusion, this study shows that the antithrombotics scheme can aid healthcare professionals to evaluate appropriateness of antithrombotics in palliative cancer patients and optimize care in the last phase of life.

Ethical statement

The Medical Ethics Committee at Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc, granted approval of the study under number 2022.0493.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept and design. Data collection was performed by AR. Data analysis was performed by AR, JK and MC. The manuscript was written by AR and was commented on by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to K.B. Gombert-Handoko for her expertise during this research.

Disclosure statement

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Based on the data use policy of Amsterdam UMC and reasonable request, the dataset is available by sending an email message to the corresponding author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, Fay M, Kearney A, Barras M. Reducing potentially inappropriate medications in palliative cancer patients: evidence to support deprescribing approaches. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1113–9. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2098-7.

- Karuturi MS, Holmes HM, Lei X, Johnson M, Barcenas CH, Cantor SB, Gallick GE, Bast RC, Giordano SH. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria in older patients with breast and colorectal cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(5):705–8. doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2019.01.024.

- Miller MG, Kneuss TG, Patel JN, Parala-Metz AG, Haggstrom DE. Identifying potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(1):34–40. doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2020.06.013.

- Morin L, Todd A, Barclay S, Wastesson JW, Fastbom J, Johnell K. Preventive drugs in the last year of life of older adults with cancer: is there room for deprescribing? Cancer. 2019;125(13):2309–17. doi:10.1002/cncr.32044.

- Huisman BAA, Geijteman ECT, Arevalo JJ, Dees MK, van Zuylen L, Szadek KM, van der Heide A, Steegers MAH. Use of antithrombotics at the end of life: an in-depth chart review study. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):110. doi:10.1186/s12904-021-00786-3.

- Huisman BAA, Geijteman ECT, Kolf N, Dees MK, Van Zuylen L, Szadek KM, Steegers MAH, van der Heide A. Physicians’ opinions on anticoagulant therapy in patients with a limited life expectancy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2021;47(6):735–44. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1725115.

- Agnelli G, Becattini C. Treatment of DVT: how long is enough and how do you predict recurrence. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;25(1):37–44. doi:10.1007/s11239-007-0103-z.

- Prandoni P, Lensing AWA, Piccioli A, Bernardi E, Simioni P, Girolami B, Marchiori A, Sabbion P, Prins MH, Noventa F, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood. 2002;100(10):3484–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0108.

- Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;160(6):809–15. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.6.809.

- Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, Fay M, Kearney A, Khatun M, Barras M. The development and evaluation of an oncological palliative care deprescribing guideline: the OncPal deprescribing guideline. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(1):71–8. doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2322-0.

- Lavan AH, Gallagher P, Parsons C, O’Mahony D. STOPPFrail (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy): consensus validation. Age Ageing. 2017;46(4):600–7. doi:10.1093/ageing/afx005.

- van Merendonk LN, Crul M. Deprescribing in palliative patients with cancer: a concise review of tools and guidelines. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(4):2933–43. doi:10.1007/s00520-021-06605-y.

- Huisman BAA. Optimizing care at the end of life: decision-making on medication with an emphasis on antithrombotics. PhD thesis. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. 2022. ISBN 9789464236927.

- Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137(2):263–72. doi:10.1378/chest.09-1584.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, De Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the euro heart survey. Chest. 2010;138(5):1093–100. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0134.

- Bateman RM, Sharpe MD, Jagger JE, Ellis CG, Solé-Violán J, López-Rodríguez M, Herrera-Ramos E, Ruíz-Hernández J, Borderías L, Horcajada J, González-Quevedo N. Chronic kidney disease: national clinical guideline for early identification and management in adults in primary and secondary care. Crit Care.2008;20(Suppl 2):94.

- Khan F, Tritschler T, Kahn SR, Rodger MA. Venous thromboembolism. Lancet. 2021;398(10294):64–77. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32658-1.

- Boon GJAM, Van Dam LF, Klok FA, Huisman MV. Management and treatment of deep vein thrombosis in special populations. Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11(9):685–95. doi:10.1080/17474086.2018.1502082.

- Oliveira L, Ferreira MO, Rola A, Magalhães M, Ferraz Gonçalves J. Deprescription in advanced cancer patients referred to palliative care. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2016;30(3):201–5. doi:10.1080/15360288.2016.1204411.

- Noel-Savina E, Sanchez O, Descourt R, André M, Leroyer C, Meyer G, Couturaud F. Tinzaparin and VKA use in patients with cancer associated venous thromboembolism: a retrospective cohort study. Thromb Res. 2015;135(1):78–83. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2014.10.030.

- Integraal Kanker Centrum Nederland (IKNL) Code N. Tumorindeling. 2022. Available from: https://iknl.nl/nkr/registratie/tumorindeling. Accessed September 2022.

- Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692–4. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x.

Appendix A.

Definition of variables

Appendix B.

Flowchart inclusion and exclusion of patients