ABSTRACT

Understanding public perceptions of climate change is crucial for more targeted communication and better-informed policymaking. Moreover, the perceptions of climate change encompass different aspects and thus need to be defined and measured using a multidimensional approach. In this paper, we introduce the Climate Perceptions Index (CPI), a composite measure that comprehensively assesses the public perceptions of climate change, based on a sample of over 100 thousand active Facebook users across 107 countries. We construct the CPI as an aggregate of three distinct dimensions that quantify the awareness of climate change, risk perception, and commitment to action. The results show that the extent of climate change perceptions varies significantly across countries and across dimensions. Countries with the highest and lowest scores globally can be found in almost all regions, and across all levels of socio-economic development. Furthermore, we analyze the relationships between the CPI dimensions and find that the influence of risk perception on commitment to action is the strongest at the lowest levels of climate change awareness. This highlights the possibility of climate change risk normalization at higher levels of awareness, and further shows that effective policies and strategies must not only focus on raising knowledge about climate change, but also overcome the normalization of its threats.

Introduction

Perceptions of climate change encompass awareness, risk perception, and commitment to action, three intertwined elements, whose relationships have been explored in diverse ways in the literature (Maartensson & Loi, Citation2022; O’Connor et al., Citation1999). Understanding these elements and their relationships is crucial for effective climate communication and policy making. The Climate Perceptions Index (CPI)Footnote1 can be viewed as an attempt to provide a comprehensive assessment of the public’s opinions on climate change globally. It measures countries’ climate change perception levels on the basis of awareness, risk perception, and commitment to action.

The awareness of climate change has always been a straightforward concept, proxied as the level of self-reported knowledge about the issue, and believed to be shaped mainly by the level of education (Metzger et al., Citation2010). The risk perception, on the other hand, refers to the way individuals perceive the likelihood, severity, immediacy, and personal relevance of climate-related threats (van der Linden, Citation2014). It can vary significantly across countries due to the multitude of factors that affect it, such as the differences in exposure to climate impacts, or cultural beliefs (Lee et al., Citation2015). As for the commitment to climate action, it is defined as the willingness to engage in climate action and advocate for pro-environmental policies (Xie et al., Citation2019).

There is a crucial need for a more comprehensive approach to measuring the public perception of climate change. It is because the link between climate change awareness and the general perception is uncertain due to the mismatch between subjective information (beliefs) and objective evidence (such as the scientific agreement that fossil fuel combustion contributes to climate change). Single-item assessments like “I know a lot about climate change” often yield inconsistent findings (Leiserowitz, Citation2006). It is therefore necessary to consider not only whether an individual is “aware” of climate change, but also the extent to which climate change is perceived as a serious threat. The intersection with awareness is important since it allows a clear demarcation between the case where individuals report a high level of knowledge about climate change while downplaying its risks, and the case where high knowledge implies a higher perception of risks and ultimately increased commitment to action and environmentally friendly behaviors.

Apart from the potential overlaps between awareness and risk perception, the commitment to action is considered to be a unique and important component of the general climate change perception. Individuals can still be reluctant to engage in pro-environmental action despite “knowing a lot about climate change” and perceiving it as a “serious threat.” This is due to the interplay of other significant factors such as the perceived cost of mitigation behaviors and low efficacy which can largely undermine the willingness to act even in cases where individuals have experience with extreme weather events and are aware of climate change. Indeed, the sense of self efficacy and belief in the usefulness of one’s actions is a necessary condition for behavioral willingness (Grothmann et al., Citation2013). This can therefore lead to a clear divide in the proportion of individuals willing to take mitigation action across countries and would depend mainly on whether civic engagement is encouraged or constrained.

In this paper, we measure the public perception of climate change across different countries in a comprehensive manner that covers the above-discussed three dimensions (i.e., awareness, risk perception and commitment to action). Most importantly, we construct the Climate Perceptions Index (CPI), a composite indicator that ranks countries based on the level of perception in all the three dimensions. This allows for a more straightforward insight into the extent to which the public is aware of climate change, perceives its risks and is committed to act against it. Furthermore, it is possible to assess countries’ performance across the three defined dimensions separately which allows for a better understanding of the potential imbalances between awareness, risk perception, and commitment to action. For instance, countries might score the highest in the awareness dimension of the index but not necessarily in others, and the same applies to the risk perception and the commitment to action. Such insight is of great importance and policy relevance as it highlights the areas where public perception is not adequately high. Most importantly, it raises key questions about the way the three dimensions of the index interact with each other.

In addition to the more comprehensive approach of measuring climate change perception across nations based on the CPI, we use the index dimensions to explore the influence of awareness on the relationship between risk perception and commitment to action. This helps to verify whether higher scores in the awareness dimension translate into a stronger relationship between risk perception and commitment to action. Testing this hypothesis is also a step forward in understanding the role of knowledge about climate change in shaping individuals’ behaviors and attitudes toward it.

We carried out this analysis using data from a survey of Facebook users in 107 countries, thereby allowing for an unprecedented overview of the global pattern of public perception on social media among over 100 thousand respondents. The survey was conducted by the Yale program of climate change communication and Meta (Leiserowitz et al., Citation2022). It investigates climate change knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, policy preference and behavior among Facebook users.

The use of this kind of data has multiple implications compared to traditional survey data. On social media, homophily (the tendency for people to interact with others who share similar beliefs and values) can largely contribute to the formation of echo chambers. This leads to a higher risk that individuals are less likely to encounter opposing viewpoints and only receive information confirming their existing beliefs (McPherson et al., Citation2001). Self-reported knowledge about climate change might therefore be associated with the denial of its occurrence since expressive activities on social media (such as voicing one’s opinions or concerns) may promote awareness but can also reinforce existing beliefs if conversations remain within the same social network (Metzger et al., Citation2010).

We further review and discuss these implications in the following literature review section, with special attention paid to the current knowledge about the inter-relationship between awareness, risk perception and the willingness to action. We devote the methodology section to the CPI construction procedure and the description of its underlying framework. We then describe the CPI global distribution of scores with a focus on regional disparities both in terms of the overall CPI score and its dimensions. Moreover, we go beyond the general description of the CPI performance and investigate changes in the cross-country relationship between risk perception and commitment to action depending on the level (scores) of awareness. We then discuss policy implications of the findings and raise some possible limitations in the discussion and conclusion sections respectively.

Literature review: the interplay between awareness, risk perception and commitment to action

Awareness and risk perception

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in understanding public perception of climate change (Lee et al., Citation2015; Leiserowitz et al., Citation2009; van der Linden et al., Citation2015), as it is seen as a crucial factor in effective climate change communication and policy making. Previous research has identified three key elements that summarize public climate change perception: awareness, risk perception, and commitment to action (O’Connor et al., Citation1999). Awareness of climate change is an essential factor in shaping public perception. Studies have shown that individuals who are more “aware” of climate change are more likely to perceive it as a serious threat (Lorenzoni et al., Citation2007). This awareness can come from various sources, including the media, educational programs, and personal experiences. Research has also found that there is variation in awareness levels across different nations. For example, individuals in developed countries tend to have higher levels of awareness compared to those in developing countries (Lorenzoni et al., Citation2007). However, higher levels of self-reported knowledge about climate change can also entail the risk of increased polarization regarding the causes, the risks and policy preferences.

Such discrepancy between the levels of self-reported knowledge about climate change and the general attitude toward climate change is best reflected on social media platforms. On social media, admitting that climate change is happening does not necessarily imply believing in its anthropogenic origins. The view that climate change has no human causation extends beyond awareness and can be linked to scientific skepticism or ignorance as well as ideological and political affiliations (Kahan et al., Citation2012; Metzger et al., Citation2010; Nisbet, Citation2009).

In the literature, it is assumed that individuals with a higher level of education have a greater understanding of the physics behind climate change and a stronger perception of the associated risks (Leiserowitz, Citation2005). However, cultural values and beliefs significantly influence risk perception. For instance, people with more individualistic values, such as personal achievement and independence, are less likely to perceive climate change as a serious threat. Conversely, those with more communitarian values, such as concern for the welfare of the community and the environment, are more likely to view climate change as a threat (Kahan et al., Citation2012). In this sense, even highly educated individuals may hold differing opinions based on their beliefs and political affiliations. For instance, a study by Kahan (Citation2015) supports this notion, revealing that among individuals with higher education levels, those who identified as politically conservative were less likely to perceive the risks of climate change compared to their politically liberal counterparts.

Risk perception and commitment to action

The study of climate change risk perception has received substantial attention in recent decades, with researchers examining this topic extensively (e.g., Capstick et al., Citation2015; Egan & Mullin, Citation2017). A significant body of research has focused on identifying the factors that influence how individuals perceive the risks associated with climate change. These factors include natural hazards (Frondel et al., Citation2017), cues from influential figures (Carmichael & Brulle, Citation2017), and optimistic views regarding technology (Fletcher et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, an increasing amount of research has explored the consequences of climate change risk perception. Studies have shown a positive correlation between climate change risk perception and actions related to climate change mitigation and adaptation (Azadi et al., Citation2019; Jakučionytė-Skodienė & Liobikienė, Citation2021). This suggests that climate change risk perception plays an important role in encouraging actions that contribute to more effective efforts in addressing climate change.

Indeed, a decline in the perception of climate change risk would undermine the overall commitment to contribute to climate change mitigation efforts (Wang et al., Citation2021). This decline poses a challenge in translating general intentions into concrete actions, mainly due to the relationship between specific determinants of behavior (e.g., less favorable attitudes, reduced perceived control, and increased perceived situational constraints) and precise behavioral intentions. Empirical evidence has shown that lower levels of climate change risk perception are associated with not only less positive attitudes toward pro-environmental actions (Mase et al., Citation2015) but also a reduced willingness to engage in such actions, and a decrease in the frequency of environmental-friendly behaviors (e.g., Lacroix & Gifford, Citation2018; Xie et al., Citation2019).

Despite the positive relationship between the perception of risk and the commitment to action, the interplay may still be fundamentally mediated by self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation2006; Bandura & Locke, Citation2003). Generally, risk perception and awareness alone are not sufficient motivations for climate action if individuals lack the sense of self-efficacy and faith in the outcomes of actions (Grothmann et al., Citation2013).Wang et al. (Citation2021) define self-efficacy in the context of climate change perception as “environmental efficacy.” That is individuals’ belief in their capacity to take actions that contribute to combating climate change. Generally, increasing environmental efficacy could boost intentions to engage in pro-environmental actions (Huang, Citation2016; Jugert et al., Citation2016; Lauren et al., Citation2016; Steinhorst et al., Citation2015).

Mediation factors of the relationship between risk perception and commitment to action

Theoretical and empirical foundations suggesting that climate change belief and environmental efficacy mediate the relationship between climate change risk perception and commitment to action can be drawn from the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory proposed by Stern (Citation2000) and Stern et al. (Citation1999). According to the latter, individuals who possess stronger beliefs regarding the natural environment and the environmental consequences of human actions are more likely to recognize the adverse outcomes of not adopting pro-environmental behavior. They also tend to believe that they can mitigate negative environmental impacts by altering their behavior. These convictions, in turn, are likely to activate norms related to their moral obligation to take pro-environmental action and engagement.

Furthermore, individuals with stronger environmental beliefs (as captured also in the data we use in this paper, for example in the question “Climate change is caused mainly by human activities”) are more likely to believe in the necessity of climate change mitigation (e.g., “Climate change should be a high, or very high priority for the government of the country where I live”). More recently, an investigation using data from the Round 8 of the European Social Survey by Verschoor et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that stronger climate change beliefs were associated with a heightened belief that reducing one’s own energy consumption could combat climate change. Building upon the VBN theory and the empirical evidence, it can be inferred that belief in the anthropogenic origins of climate change, recognition of its negative impacts, and concern about its consequences are positively linked to a stronger conviction that individual actions can contribute to climate change mitigation. Consequently, this heightened sense of environmental efficacy may induce a sense of moral obligation to act, promoting climate change action. In summary, an increased perception of climate change risk may amplify climate change beliefs, which, in turn, could improve climate change action by fostering a stronger sense of environmental efficacy (Wang et al., Citation2021).

Materials and methods

Conceptual framework

The Climate Perceptions Index is built upon the data collected by Meta in its Facebook International Public Opinion on Climate Change Survey (Leiserowitz et al., Citation2022). In partnership with the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, Meta conducts an annual climate change opinion survey that explores public climate change knowledge, attitudes, policy preferences, and behaviors. The data collection methods, translations, sampling characteristics etc. were undertaken by Meta, and together with simple descriptive statistics of the survey results, they are described in Leiserowitz et al. (Citation2022). There are sixteen questions in the questionnaire, each consisting of multiple response options, out of which only one could have been selected by the respondents. Survey data are provided by respondents for each of the 107 countries (and three additional regional groupings) by Data for Good department of Meta.

After assessing the nature of the questions, we construct the CPI theoretical framework centered around the three concepts which we refer to as CPI “dimensions:” Awareness, Risk Perception, and the Commitment to Action. Based on conceptual fit and statistical testing we select the most appropriate questions from the questionnaire. We choose to create a symmetric index structure, having four questions in each of the three dimensions. This ensures equal weighting for each dimension.

While the questions broadly determine the variables used in the CPI framework, it still needs to be decided how we treat the response categories of each question. To do this, we develop a systematic approach that assigns weights to responses indicating some extent of awareness, risk perception, and commitment to action. These responses with weights are then included in the Index calculation while the rest is disregarded. We prefer this approach over standardizing the individual responses since not all of them can be considered ordinal. Therefore, we give a weight of one to the responses that approximate the highest awareness, risk perception, and commitment to action (usually containing words such as “very high,” “great deal,” “a lot”). Weight of 0.5 is given to the second “best” category (if applicable), usually consisting of words such as “moderate,” “somewhat” and “high.”

However, some questions do not have an entirely comparable scale, and we have to treat these individually. In the Commitment to Action dimension, the “personal importance of climate change” question includes response categories of “extremely important,” “very important,” and “somewhat important.” Therefore, we give the first and “somewhat” categories weights of 1 and 0.5, respectively, which is consistent with our general approach, and assign the “very important” category in the middle a weight of 0.75. Additionally, for the question on responsibility for pollution causing climate change, we set the weights equal for all three non-denying responses (since it is an example of non-ordinal responses). Lastly, for four questions, we include one response category that best reflects the desired extent of awareness, risk perception, and commitment to action. The structure of the Index, with the response categories (and their weights) included for each question, is visualized in .

Figure 1. Structure of the CPI.

The Awareness dimension consists of four questions and measures the level of knowledge, the belief that climate change is a real phenomenon,Footnote2 the ideas about the causes, and the frequency of hearing about climate change. The Risk Perception dimension measures the extent of the perceived risk of climate change from a narrow, personal perspective, where the respondents report the level of concern that climate change will harm them personally, and from an intergenerational perspective, where respondents report the level of concern about the harm that climate change will cause for future generations. And finally, the Commitment to Action dimension measures the willingness to adopt a pro-environmental behavior. The questions capture the importance people place on the issue of climate change and policy preferences regarding the government’s involvement and their country’s accountability in addressing the issue of climate change.

Data treatment and CPI calculation

Survey data is provided by respondents in each participating country. We aggregate the respondent-level data by countries and create country-level proportions for all response categories of each question included in the Index framework.Footnote3 For the aggregation, we apply the survey weights (Leiserowitz et al., Citation2022). We compute the variables as the weighted average of the country-level proportions of the included questions’ response categories as shown in above.

To allow for better comparability across countries and indicators, each of these variables is scaled to 0–100 scores using a theoretical best-case (100) and worst-case (0) method combined with a min-max standardization procedure. This is done by expanding the dataset of two fictitious cases – best and worst – which represent the 100 and 0 scores respectively that are then used in the min-max standardization. For example, the best case is where 100% of respondents agree climate change is happening, and the worst case is where 0% of respondents agree climate change is happening. If a country has 57% of respondents agreeing, their score will be 57. Moreover, scaling the individual variables to 0–100 scores means that also the CPI and its dimensions are measured on the 0–100 scale, where 0 represents the worst possible performance, and 100 the best possible performance.

We use the arithmetic average for the aggregation of individual variable scores into dimension scores, and dimension scores to CPI scores. Being aware of the full compensability of the arithmetic average aggregation (Mazziotta & Pareto, Citation2016), we opted for this method as it is more commonly understood. Moreover, we also tested other methods of aggregation (geometric average and principal component factor’s derived weights), but their results were very similar to arithmetic average.

We performed basic multivariate analyses (both on the underlying microdata, as well as on the country level values) which validated the groupings of questions, as it ensured a good statistical fit. For each dimension, the analyses tested for correlations between indicators (using the Pearson correlation coefficients) and unidimensionality (using the Principal Component Factor, PCF). We also calculated Cronbach’s Alpha (Tavakol & Dennick, Citation2011) and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (Shrestha, Citation2021) to evaluate the internal consistency across indicators and the goodness of fit, respectively. As for the correlations, out of the 18 correlation coefficients in total (six in each dimension), 17 were reasonably high (>0.38, the highest value was 0.92) and statistically significant at the 1% level. The remaining coefficient was 0.16 and it was significant at the 10% level. The other multivariate test results are shown in and they indicate unidimensionality (based on the PCF results), internal consistency across indicators (based on the Cronbach’s alpha values) and a good statistical fit (based on the KMO results) of each dimension.

Table 1. Multivariate tests results.

Results

The Climate Perceptions Index

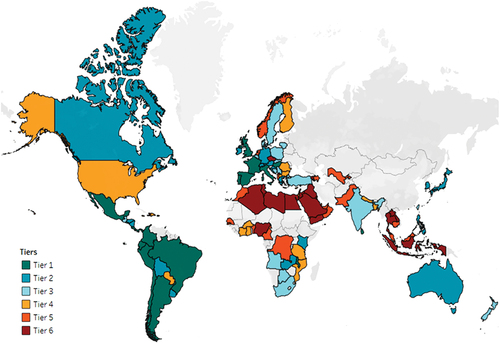

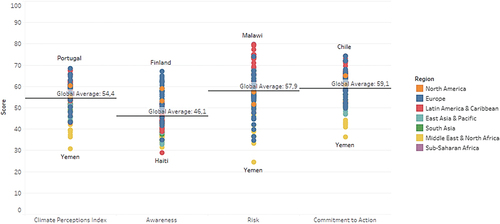

The CPI covers 107 countries and 3 additional regional groupings of countries. We created six performance tiers that were calculated as sextiles based on the CPI’s ranking. Tier 1 denotes the best-performing countries, while Tier 6 indicates the worst-performing countries on the aggregate index. shows the geographical distribution of scores where the higher the score, the higher is the degree of the overall perception of climate change. The scores serve therefore as a composite measure of countries’ awareness, risk perception and the commitment to action. Tier 1 category (the highest sextile) consists of Western Europe and Latin American countries. Tier 2 and 3 categories are geographically more scattered as they include Canada, Australia and India as well as predominantly European countries such as Germany and Poland (plus several Sub-Saharan African countries, including South Africa). Similarly, Tier 4 and 5 categories are geographically dispersed and consist of countries such as the United States, Finland and Norway. Countries with the lowest scores (Tier 6) are predominantly found in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, but also include countries from other parts of the world (for example Indonesia, Thailand, or the Czech Republic).

Clearly, the level of climate change perception (as measured by the CPI scores) varies significantly across countries. The highest and lowest performance can be observed across regions, and simultaneously in developed and developing countries. In addition to the extent of cross-country disparities, the CPI also establishes how the public’s view of climate change matches with the hazards that it poses to countries. For instance, the MENA countries respondents report the lowest scores despite being relatively more vulnerable to droughts and substantial increase in temperatures (Waha et al., Citation2017). While in some of these cases it can be due to the lack of general knowledge about climate change and its risk, the observed low CPI scores in more developed countries such as Norway, Finland, and the Czech Republic reflect a higher level of polarization on the issue (Kahan et al., Citation2012; Nisbet, Citation2009), which might then be exacerbated, especially on social media, due to the lack of exposure to opposing viewpoints. As a result, individuals may become less receptive to alternative viewpoints and more rigid in their preexisting beliefs (Martin, Citation2018).

Low CPI scores in some European countries are mainly due to low performance in the Risk perception and Commitment to action dimensions. For instance, countries such as Finland, Norway, and the Czech Republic achieve some of the highest scores in the Awareness dimension but the lowest scores in the other two dimensions. Such a combination of performance further illustrates that high levels of awareness about climate change do not necessarily translate to a higher perception of its risks nor a higher commitment to action. In more developed countries, higher levels of education translate into higher knowledge about climate change, yet the lack of experience with extreme weather events (or with the destructive consequences of those) might limit the perception of risks. Furthermore, higher education has been found to be associated with increased climate change denial (Kahan, Citation2015) which should undermine the commitment to action as well.

As shown in , the highest scores of the Risk perception dimension are therefore observed in less developed contexts. For instance, while Malawi (clearly an outlier compared to other regional peers) has the highest scores of Risk perception, Sub-Saharan countries have generally moderate scores in the Risk perception and Commitment to action dimensions. Latin American countries appear to have generally high levels of risk perception and commitment to action but, strikingly, significantly lower levels of awareness. However, as a result of having the best scores in both Risk perception and Commitment to action dimensions, Latin American countries achieve the highest scores in the overall CPI. On the contrary, the MENA region countries’ low CPI scores are the result of low performance across all dimensions.

One of the most important findings is that countries’ perception varies significantly across the three dimensions. Latin American and European countries exhibit the greatest gap of scores across the dimensions. For instance, while the Awareness score is the highest among European countries, the Risk perception and Commitment to action scores are generally lower. The same is true for Latin American countries where the Risk perception and the Commitment to action are the highest whereas the Awareness scores are significantly lower. Such imbalances raise questions about the interrelations between the dimensions, especially if we consider the level of awareness as the discriminant factor shaping the relationship between the risk perception and the commitment to action.

The influence of awareness on the relationship between risk perception and commitment to action

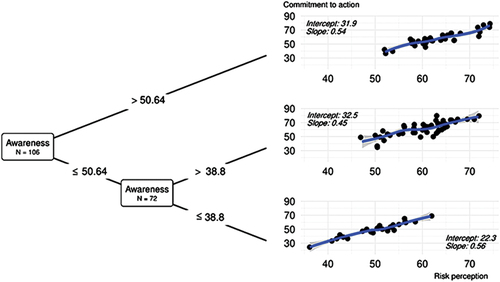

We further investigate the dimensional interrelationships by constructing a linear model tree. This allows us to model the relationship between Risk perception and Commitment to action within different subsets of countries based on the score in the Awareness dimension. We are, therefore, able to compare how risk perception is associated with the commitment to action across different levels of awareness in order to determine whether this association increases or decreases with higher levels of awareness about climate change.

shows the relationship between the risk perception and the commitment to action across different levels of awareness. Countries are divided into two groups: countries with an awareness score strictly higher than 50.64, and countries with a score lower or equal to 50.64. The latter is then split into two groups again: countries with an awareness score strictly higher than 38.8, and countries with a score lower or equal to 38.8. All three split values are calculated as levels resulting in a significant change in the parameters of the models. The effect of the risk perception on the commitment to action is then assessed for each of these 3 groups and summarized by the scatterplots (terminal nodes) in .

Figure 4. Linear model tree: Risk perception vs. Commitment to action.

Overall, the relationship between risk perception and commitment to action is positive but its strength (slope) varies across the levels of awareness. Strikingly, the relationship is the strongest among countries with the lowest level of awareness (i.e., less, or equal to 38.8) with a slope equal to 0.56. For countries with slightly higher levels of awareness (a score between 38.8 and 50.64), the association between risk perception and commitment to action weakens, with a slope of 0.45. As for the countries with the highest level of awareness (a score higher than 50.64), the relationship is stronger (slope equal to 0.54) but still weaker than that of countries with the lowest levels of awareness. We find therefore that the effect of risk perception on commitment to action does not increase with higher levels of awareness. And what is even more striking: in countries for which the awareness score is lower than 50.64, this effect actually decreases with higher levels of awareness.

Such findings provide further evidence that higher levels of awareness about climate change are not necessarily associated with better commitment to action against it. Indeed, self-reported knowledge about climate change does not necessarily imply concerns about its risks or willingness to engage in pro-environmental actions. In fact, various factors can influence the latter, such as political ideology, values, and beliefs that can be shaped (to a great extent) by the level of education (McCright & Dunlap, Citation2011). In this sense, individuals might have negative attitudes toward climate change while at the same time reporting high levels of knowledge about it.

The overall CPI score serves therefore as a comprehensive measure of how responsive individuals are to climate change. Most importantly, it considers not only the level of awareness about the issue but also the extent to which individuals are concerned about its risks, and how much they are committed to engage in environmental action. As a result, countries such as Portugal, Costa Rica and Spain achieve the highest scores due to a combination of several factors. Individuals in these countries have relatively higher levels of education directly affecting the level of knowledge about climate change. At the same time, they are more exposed to the consequences of climate change and have a stronger commitment to engage in civic pro-environmental action.

On the other hand, lower CPI scores (e.g., MENA region countries particularly) are mainly due to lower levels of awareness and risk perception, combined with restrictions to engage in pro-environmental action. Unlike MENA, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa exhibit moderate performance that is mainly driven by the risk perception and the commitment to action dimensions. Indeed, the higher vulnerability to extreme weather events generally results in a higher intention of individuals to engage in pro-environmental action. This highlights the importance of considering not only individual knowledge and awareness, but also the contextual factors that can influence attitudes and behaviors toward climate change (Shi et al., Citation2015).

Discussion

There is a disconnect between awareness and risk perception of climate change

The CPI reveals how individuals perceive climate change in different geographical locations around the world. One of the most striking findings is the significant contrast of countries’ performance in the Awareness dimension and, particularly, in the Risk perception dimension. Prior research has established that higher risk perception is associated with the experience with extreme weather events (Howe, et al., Citation2019; Zhang, Citation2022). Our results show that countries with the lowest performance in this dimension are not only European countries, but the MENA countries as well. For the former, it can be argued to some extent that individuals do not necessarily have a significant exposure to extreme weather changes over the last few years. Compared to the MENA countries however, the results are surprising and raise a number of questions about the ways the perception of climate change risks is shaped.

Indeed, the “psychological distance” to climate change (Jones et al., Citation2017; Spence et al., Citation2012) in some contexts seems more rigid and personal experiences with extreme weather may not have a significant impact on public engagement with climate change. These experiences might not necessarily increase the cognitive salience of climate change or trigger an emotional response (Demski et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it could be that personal experiences with extreme weather do not consistently lead to heightened feelings of personal vulnerability and concern, as they may not make potential risks more concrete.

While it could be argued that low awareness leads to low-risk perception, we observe that risk perception scores are low even among countries with generally high awareness scores (e.g., European countries). This shows there is a disconnect between awareness and risk perception, illustrating that there are other factors (than education and experiences with extreme weather) that distort the expected simple relationship between the two dimensions. Numerous studies emphasize the pervasive influence of political ideology and partisan preferences in various contexts (Brulle et al., Citation2012; Guber, Citation2013; Krosnick et al., Citation2000). These factors not only diminish the significance of education (Hamilton, Citation2011; Malka et al., Citation2009) but also cast a shadow over the significance of individuals’ personal encounters with extreme weather events (Brulle et al., Citation2012; Carmichael & Brulle, Citation2017; Marquart-Pyatt et al., Citation2014; McCright et al., Citation2014; Ogunbode et al., Citation2017; Zahran et al., Citation2006). This holds particularly in contexts where individuals are more politically engaged and where voters have been observed to adjust their beliefs and attitudes to align with the positions of their favored political party (for example, Dunlap & McCright, Citation2008; Guber, Citation2013; Linde, Citation2018).

It is worth noting, however, that the relationship between awareness and risk perception might depend largely on the way awareness is measured. In research, employing subjective measures of knowledge, where respondents self-assess their level of knowledge (as in the present study), findings have indicated a mix of positive, negative, and context-dependent effects on levels of concern (Malka et al., Citation2009). In contrast, studies relying on objective measures of knowledge, involving respondents answering factual questions, have consistently demonstrated a positive correlation between knowledge and concern regarding climate change (O’Connor et al., Citation1999; Shi et al., Citation2015). However, these investigations have also revealed that the influence of knowledge on concern varies depending on the type of knowledge. For instance, while causal knowledge tends to be positively associated with concern, knowledge concerning the physical attributes of climate change has exhibited both negative and inconsequential associations with concern (Shi et al., Citation2016).

To bridge the gap between awareness and risk perception, policies and initiatives should not only focus on disseminating information, but also on addressing the ideological and partisan divides that hinder climate action. Policymakers may need to employ strategies that appeal to diverse political perspectives and encourage bipartisan cooperation to effectively tackle climate change.

Higher levels of awareness are not associated with a stronger relationship between risk perception and commitment to action

Furthermore, our research shows that no country achieves high scores across the Awareness, Risk perception, and Commitment to action dimensions. Instead, our findings reveal an intriguing pattern: countries with the highest Awareness scores, such as those in Europe, exhibit only moderate levels of Risk perception. Conversely, countries that score the highest in both Risk perception and Commitment to action, many in Latin America, achieve only moderate Awareness levels. This suggests a notable discontinuity in the impact of awareness on both risk perception and commitment to action, where higher awareness does not necessarily translate into higher levels of risk perception nor commitment to action. Our results further support this observation, revealing that the relationship between risk perception and commitment to action varies across different awareness levels. Surprisingly, we find that among countries with higher awareness scores, this relationship is weaker compared to countries with lower awareness scores.

This may be due to risk perception “normalization” which has significant implications on commitment to action. When individuals are repeatedly exposed to alarming communication about climate change, they may tend to adapt to its presence, leading to a weaker connection between their perception of risks and their commitment to action. This effect is particularly relevant in the contexts where the consequences of climate change are often perceived as distant in both space and time (European countries), making it challenging to grasp their immediacy. As a result, climate change related communication aiming at raising risk perception may have little to no real impact on commitment to action.

Such a mediation effect of awareness in the relationship between risk perception and commitment to action was previously established by Lima et al. (Citation2005). They found that indicators of technological prevalence, such as CO2 emissions and chemical use in agriculture, were associated with lower risk perception. This relationship was mediated by increased awareness of environmental hazards linked to these technologies. Higher technological prevalence led to greater awareness of environmental risks due to advancements in policy and risk management. However, this heightened awareness was paradoxically linked to reduced perceived risks associated with those technologies, such as climate change and pollution from chemical use in farming. It appears that individuals tend to develop psychological strategies to minimize perceived threats, which, unfortunately, do not contribute to solving environmental hazards.

In addition, individuals who possess knowledge about climate change may not translate this awareness into action, leading to implicatory denial. This suggests a disconnection between abstract climate change information and its integration into everyday life. Interpretative denial also comes into play as individuals may reinterpret climate change information, perceiving it as a natural occurrence or underestimating its severity. Furthermore, as we use data from social media users, our analysis underscores the potential effect of vested-interest groups engaging in misinformation campaigns further contributing to climate change denial and undermining public understanding of scientific consensus and impeding policy progress (Oreskes & Conway, Citation2010).

In the realm of climate change policy, it is imperative to recognize and address the “normalization” of climate change risks resulting from increased awareness. Effective policies and strategies must overcome the psychological adaptation to threats and the associated disconnect between knowledge and action. Furthermore, confronting climate change denial necessitates countering the reinterpretation of climate information and mitigating the influence of vested-interest groups. Policymakers must consider not only the scientific and economic aspects but also the psychological and sociopolitical dimensions in order to foster meaningful commitment to climate action and mitigation behaviors.

Conclusion

The Climate Perceptions Index offers a comprehensive view of how countries perceive climate change across the globe. Our results show that climate change is perceived differently across countries. There are significant disparities in the extent to which people are aware of climate change, perceive it as a threat and are willing to act against it. Generally, the Latin American countries are the most perceptive of climate change, while countries from the MENA region are the least. The performance of countries from other regions varies significantly across dimensions. For instance, while European countries achieve high levels of awareness, they perform moderately in terms of the risk perception and commitment to action. In contrast, the risk perception levels in Sub-Saharan African countries are higher than the awareness and commitment to action.

However, in this paper we move beyond the general description of country scores and use the Index to reveal the complexity of the relationship between awareness, risk perception and commitment to action. In particular, we study how the strength of the relationship between risk perception and commitment to action varies based on the levels of awareness. Surprisingly, the strongest relationship is found among countries with lower performance in awareness. In contrast, countries with higher awareness do not necessarily exhibit a stronger connection between risk perception and commitment to action. This finding underscores the notion that high awareness does not always translate into proactive environmental engagement (Shi et al., Citation2015). Multiple factors, including political ideology and values, can influence a person’s attitude toward climate change. As a result, individuals may hold views denying climate change despite reporting high levels of knowledge about it.

This mismatch between the CPI dimensions highlights the need for a deeper understanding of individuals’ climate change perception across countries, or more precisely, to identify the factors that shape each of the dimensions: awareness, risk perception and commitment to action. This would allow for a better understanding of the key differences between countries in terms of how climate change is perceived and what factors influence it (Lee et al., Citation2015; van der Linden, Citation2014; van der Linder et al., 2015). Furthermore, there is also a need for a better understanding of the causal links between awareness, risk perception and commitment to action, and possible mediation effects and feedback shaping the relationships.

Finally, it should be stressed that despite its wide geographical coverage, the climate change perception assessment in this study is based exclusively on samples of Facebook users from different countries. While the sampling and entry data treatment for each country is carried out by authors of the original survey in a way that minimizes the possible biases (Leiserowitz et al., Citation2022), it still needs to be borne in mind that some social groups (typically older people) may be underrepresented, especially in countries where Facebook is a less common social media type. Our results should therefore be interpreted while accounting for these special features of the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This paper examines in detail, and further elaborates upon the (primarily) policy-oriented work undertaken by the nonprofit Social Progress Imperative, and with the support of the Meta corporation (Htitich et al., Citation2022).

2. Respondents were given also a short description of climate change before being asked whether they believe climate change is happening. The complete survey question is as follows: “Climate change refers to the idea that the world’s average temperature has been increasing over the past 150 years, will increase more in the future, and that the world’s climate will change as a result. What do you think: Do you think climate change is happening?.”

3. By doing this, we are able to establish, for each country in the survey, the exact percentage of respondents in each response category of all survey questions.

References

- Azadi, Y., Yazdanpanah, M., & Mahmoudi, H. (2019). Understanding smallholder farmers’ adaptation behaviors through climate change beliefs, risk perception, trust, and psychological distance: Evidence from wheat growers in Iran. Journal of Environmental Management, 250, 109456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109456

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, 5(1), 307–337.

- Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.87

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1997). Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 314(7080), 572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

- Brulle, R. J., Carmichael, J., & Jenkins, J. C. (2012). Shifting public opinion on climate change: An empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the US, 2002–2010. Climatic Change, 114(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0403-y

- Capstick, S., Whitmarsh, L., Poortinga, W., Pidgeon, N., & Upham, P. (2015). International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 6(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.321

- Carmichael, J. T., & Brulle, R. J. (2017). Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: An integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001–2013. Environmental Politics, 26(2), 232–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2016.1263433

- Demski, C., Capstick, S., Pidgeon, N., Sposato, R. G., & Spence, A. (2017). Experience of extreme weather affects climate change mitigation and adaptation responses. Climatic Change, 140(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1837-4

- Dunlap, R., & McCright, A. (2008). A widening gap: Republican and democratic views on climate change. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 50(5), 26. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.50.5.26-35

- Egan, P. J., & Mullin, M. (2017). Climate change: US public opinion. Annual Review of Political Science, 20(1), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051215-022857

- Fletcher, J., Higham, J., Longnecker, N., & Villamayor-Tomas, S. (2021). Climate change risk perception in the USA and alignment with sustainable travel behaviours. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0244545. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244545

- Frondel, M., Simora, M., & Sommer, S. (2017). Risk perception of climate change: Empirical evidence for Germany. Ecological Economics, 137, 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.02.019

- Grothmann, T., Grecksch, K., Winges, M., & Siebenhüner, B. (2013). Assessing institutional capacities to adapt to climate change: Integrating psychological dimensions in the adaptive capacity wheel. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 13(12), 3369–3384. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-3369-2013

- Guber, D. L. (2013). A cooling climate for change? Party polarization and the politics of global warming. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(1), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764212463361

- Hamilton, L. C. (2011). Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change, 104(2), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9957-8

- Howe, P. D., Marlon, J. R., Mildenberger, M., & Shield, B. S. (2019). How will climate change shape climate opinion? Environmental Research Letters, 14(11), 113001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab466a

- Htitich, M., Krylova, P., Harmáček, J., & Lisney, J. (2022). Climate perceptions index. Social Progress Imperative. https://www.socialprogress.org/climate-perceptions-index/

- Huang, H. (2016). Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2206–2212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.031

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M., & Liobikienė, G. (2021). Climate change concern, personal responsibility and actions related to climate change mitigation in EU countries: Cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 281, 125189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125189

- Jones, C., Hine, D. W., & Marks, A. D. (2017). The future is now: Reducing psychological distance to increase public engagement with climate change. Risk Analysis, 37(2), 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12601

- Jugert, P., Greenaway, K. H., Barth, M., Büchner, R., Eisentraut, S., & Fritsche, I. (2016). Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.08.003

- Kahan, D. M. (2015). The politically motivated reasoning paradigm. Emerging trends in social & behavioral sciences, Forthcoming. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2703011

- Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L. L., Braman, D., & Mandel, G. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 2(10), 732–735. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1547

- Krosnick, J. A., Holbrook, A. L., & Visser, P. S. (2000). The impact of the fall 1997 debate about global warming on American public opinion. Public Understanding of Science, 9(3), 239. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/303

- Lacroix, K., & Gifford, R. (2018). Psychological barriers to energy conservation behavior: The role of worldviews and climate change risk perception. Environment and Behavior, 50(7), 749–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517715296

- Lauren, N., Fielding, K. S., Smith, L., & Louis, W. R. (2016). You did, so you can and you will: Self-efficacy as a mediator of spillover from easy to more difficult pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.10.004

- Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C. Y., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(11), 1014–1020. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2728

- Leiserowitz, A. A. (2005). American risk perceptions: Is climate change dangerous? Risk Analysis, 25(6), 1433–1442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00690.x

- Leiserowitz, A. A. (2006). Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Climatic Change, 77(1–2), 45–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9059-9

- Leiserowitz, A., Carman, J., Buttermore, N., Neyens, L., Rosenthal, S., Marlon, J., Schneider, J., & Mulcahy, K. (2022). International public opinion on climate change, 2022. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and Data for Good at Meta.

- Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., & Roser-Renouf, C. (2009). Global warming’s six Americas. Yale project on climate change communication. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/global-warmings-six-americas-2009/

- Lima, M. L., Barnett, J., & Vala, J. (2005). Risk perception and technological development at a societal level. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 25(5), 1229–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00664.x

- Linde, S. (2018). Political communication and public support for climate mitigation policies: A country-comparative perspective. Climate Policy, 18(5), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1327840

- Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S., & Whitmarsh, L. (2007). Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change, 17(3–4), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.004

- Maartensson, H., & Loi, N. M. (2022). Exploring the relationships between risk perception, behavioural willingness, and constructive hope in pro-environmental behaviour. Environmental Education Research, 28(4), 600–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.2015295

- Malka, A., Krosnick, J. A., & Langer, G. (2009). The association of knowledge with concern about global warming: Trusted information sources shape public thinking. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 29(5), 633–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01220.x

- Manly, B. F. (2004). Multivariate statistical methods: A primer (3rd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC Press.

- Marquart-Pyatt, S. T., McCright, A. M., Dietz, T., & Dunlap, R. E. (2014). Politics eclipses climate extremes for climate change perceptions. Global Environmental Change, 29, 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.004

- Martin, D. (2018). #republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media, by Cass R. Sunstein 2017 328 pp. Business Ethics Quarterly, 28(3), 360–363. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2018.22

- Mase, A. S., Cho, H., & Prokopy, L. S. (2015). Enhancing the social amplification of risk framework (SARF) by exploring trust, the availability heuristic, and agricultural advisors’ belief in climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.12.004

- Mazziotta, M., & Pareto, A. (2016). On a generalized non-compensatory composite index for measuring socio-economic phenomena. Social Indicators Research, 127(3), 983–1003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0998-2

- McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. The Sociological Quarterly, 52(2), 155–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

- McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E., & Xiao, C. (2014). The impacts of temperature anomalies and political orientation on perceived winter warming. Nature Climate Change, 4(12), 1077–1081. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2443

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., & Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 413–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01488.x

- Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

- O’Connor, R. E., Bard, R. J., & Fisher, A. (1999). Risk perceptions, general environmental beliefs, and willingness to address climate change. Risk Analysis, 19(3), 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1999.tb00421.x

- Ogunbode, C. A., Liu, Y., & Tausch, N. (2017). The moderating role of political affiliation in the link between flooding experience and preparedness to reduce energy use. Climatic Change, 145(3–4), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2089-7

- Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2010). Defeating the merchants of doubt. Nature, 465(7299), 686–687. https://doi.org/10.1038/465686a

- Shi, J., Visschers, V. H. M., & Siegrist, M. (2015). Public perception of climate change: The importance of knowledge and cultural worldviews. Risk Analysis, 35(12), 2183–2201. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12406

- Shi, J., Visschers, V. H., Siegrist, M., & Arvai, J. (2016). Knowledge as a driver of public perceptions about climate change reassessed. Nature Climate Change, 6(8), 759–762. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2997

- Shrestha, N. (2021). Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 9(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajams-9-1-2

- Spence, A., Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. (2012). The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 32(6), 957–972. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01695.x

- Steinhorst, J., Klöckner, C. A., & Matthies, E. (2015). Saving electricity–for the money or the environment? Risks of limiting pro-environmental spillover when using monetary framing. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.05.012

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human Ecology Review, 6(2), 81–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24707060

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- van der Linden, S. (2014). On the relationship between personal experience, affect and risk perception: The case of climate change. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(5), 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2008

- van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D., Maibach, E. W., & Ebi, K. L. (2015). The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: Experimental evidence. PLOS ONE, 10(2), e0118489. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118489

- Verschoor, M., Albers, C., Poortinga, W., Böhm, G., & Steg, L. (2020). Exploring relationships between climate change beliefs and energy preferences: A network analysis of the European social survey. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 70, 101435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101435

- Waha, K., Krummenauer, L., Adams, S., Aich, V., Baarsch, F., Coumou, D., & Schleussner, C. F. (2017). Climate change impacts in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region and their implications for vulnerable population groups. Regional Environmental Change, 17(6), 1623–1638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1144-2

- Wang, C., Geng, L., & Rodriguez-Casallas, J. D. (2021). How and when higher climate change risk perception promotes less climate change inaction. Journal of Cleaner Production, 321, 128952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128952

- Xie, B., Brewer, M. B., Hayes, B. K., McDonald, R. I., & Newell, B. R. (2019). Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101331

- Zahran, S., Brody, S. D., Grover, H., & Vedlitz, A. (2006). Climate change vulnerability and policy support. Society and Natural Resources, 19(9), 771–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920600835528

- Zhang, F. (2022). Not all extreme weather events are equal: Impacts on risk perception and adaptation in public transit agencies. Climatic Change, 171(1–2), 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03323-0