Abstract

The transfer of knowledge of effective practice, especially into “usual care” settings, remains challenging. This article argues that to close this gap we need to recognize the particular challenges of whole-system improvement. We need to move beyond a limited focus on individual programs and experimental research on their effectiveness. The rapidly developing field of implementation science and practice (ISP) provides a particular lens and a set of important constructs that can helpfully accelerate progress. A review of selected key constructs and distinctive features of ISP, including recognizing invisible system infrastructure, co-construction involving active collaboration between stakeholders, and attention to active implementation, supports for providers beyond education and training. Key aspects of an implementation lens likely to be most helpful in sustaining effectiveness include assisting innovators to identify and accommodate the architecture of existing systems, understand the implementation process as a series of distinct but nonlinear stages, identify implementation outcomes as prerequisites for treatment outcomes, and analyse implementation challenges using frameworks of implementation drivers. In complex adaptive systems, how services are implemented may matter more than their specific content, and how services align and adapt to local context may determine their sustained usefulness. To improve implementation-relevant research, we need better process evaluation and cannot rely on experimental methods that do not capture complex systemic contexts. Deployment of an implementation lens may perhaps help to avoid future “rigor mortis,” enabling more productively flexible and integrative approaches to both program design and evaluation.

Much has been written about the missing links in the science-to-service (or “research-to-practice”) chain. There is a continuously developing evidence base about the overarching principles and the specific behaviors of effective practice in services for children and families, and the dissemination of this information is the principal business of the many clearing houses, evidence repositories, “What Works centers,” and formal lists of recommended or approved effective programs that now proliferate in many countries. Yet in spite of this, the mobilization of knowledge about “what works” within front line practice remains a challenge (Saldana, Citation2014), especially within “usual care” settings that cater to the vast majority of children and youth in the community (Durlak & DuPre, Citation2008). Blase and colleagues have noted that in many human services “what is known is generally not adopted” (Blase, Citation2012, p. 5). For others, the uptake of knowledge into practice as usual is still taking place at an “unacceptably slow pace” (Mitchell, Citation2011, p. 208). Moreover, even when considerable investment is made to introduce innovations within service systems, sustaining the potential over the longer term continues to challenge policy and practice communities across the globe (Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, Citation2013).

This article provides a broad overview of how the developing theoretical frameworks and associated assessment and evaluation tools derived from the study of implementation processes are currently contributing—and may in time contribute even more powerfully—to bridging the science-to-service gap. It identifies several key features of an implementation lens (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, Citation2005), noting in particular the significance of recognizing the complex adaptive systems contexts (Paina & Peters, Citation2012) within which all public service innovations are located, and which fundamentally determine the ease and speed with which individual programs can become established and be sustained. I argue that when working in complex and constantly shifting systems, such a perspective is a practical and helpful counterweight to what can sometimes be a constraining overconcentration on “rigor” in program design, delivery and evaluation—a constraint that may have been the unintended consequence of an otherwise valuable emphasis of recent years on the development of evidence-based practice and more robust experimental evaluation methods. The article also notes the promise of hands-on, co-constructed support for implementation at the policy and practice front lines for more sustained effectiveness, and it calls for greater attention from policymakers and researchers to how this can be optimized.

FROM INDIVIDUAL PROGRAMS TO WHOLE SYSTEMS: SOME LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE EVIDENCE-BASED MOVEMENT

Over the past decade or two (and less in Europe than in North America), the growth of a more sophisticated and theory-driven approach to individual program design and evaluation has been evident in the children’s services sector. The development of the so-called evidence-based practice movement (Hammersley, Citation2005) has raised the aspirations of many child and family service commissioners and providers to import the perceived rigor and greater certainty of effectiveness of the clinical sciences into the wider field of social intervention. Although we may bemoan the slow speed of change (Chaudoir, Dugan, & Barr, Citation2013; Mitchell, Citation2011), there has been a clear direction of travel toward a more firmly theory-based and empirically testable science of intervention, and a spread of the concept of an evidence-based program (EBP) or an empirically supported intervention/treatment beyond clinical settings into a wide variety of community settings. A modest number of specific EBPs have attracted international investment well beyond their original places of development and have become widely known and implemented in different parts of the globe, including, for example, within Europe the Incredible Years Program (Webster-Stratton, Citation2001); Multisystemic Therapy (Henggeler, Citation2003) Triple P (Saunders, Citation1999), Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (Chamberlain, Citation2003), and Nurse–Family Partnership (Olds, Citation2006). Some of these are supported by sophisticated business models and substantial research programs. The particular approach to intervention design and especially intervention delivery that underpins the best known programs has been extremely influential and has taught the field much. Although the leading programs vary in their degree of specificity in this regard, they share an emphasis on the articulation of content or curriculum by means of supporting manuals or other forms of documentation, which has focused attention on the value of clearly operationalizing and documenting treatment approaches in particular for the purposes of replication. They have also emphasized the importance of adherence by practitioners to the content “as designed” in order to preserve the intended effectiveness of the intervention,Footnote1 (see also Carroll et al., Citation2007; Daro, Citation2010), which has focused attention on the principle of delivery that is faithful to the theory-base of the intervention. Although these may now seem obvious markers of effective intervention to many, it was not always so.

Another valuable contribution of the growth in EBPs has been a stronger engagement across the whole sector with higher standards of research on effectiveness. Over time the leading EBPs have become associated in the minds of many with an approach to evaluation that has moved away from an interest in process assessment toward a preoccupation with outcome measurement. This influence has penetrated to the extent that we now see many fewer “outputs, throughputs, and satisfaction” studies, where the monitoring of activities, attendance and acceptability to service users constitutes the sole focus. Although each of these is a necessary aspect of an effective service, it is now generally accepted that on their own, they do not constitute sufficient proof of effectiveness (Gilliam & Leiter, Citation2003). By contrast we now see many more outcome studies, some with results for service users assessed against a randomized counterfactual, and with relatively less focus on the service delivery process. As research evidence derived from studies using experimental methods has accumulated in relation to EBPs, so the idea that all intervention programs seeking public funding should ideally be similarly tested has gained currency (Department for Education, Citation2013; NESTA, Citation2011).

Few of those working for child and family service improvement would argue against the importance of well-designed and carefully delivered interventions, or deny that robust tests of effectiveness should be key elements of accountability in a well-constructed public service system. It is also true that we are still a long way from both these markers of quality “as standard” in many parts of the wider system of care for vulnerable children and their parents. Insisting on continued efforts to achieve better quality standards remains a clear and pressing responsibility of all who work in the field. However, it is also clear that a focus on promoting the spread of individual evidence-based programs alone has limitations. In many jurisdictions it is the opinion of expert commentators that many of our most important “services as usual” for children and families delivered within the community remain substantially untouched by evidence-based approaches (Chaffin & Friedrich, Citation2004; House of Commons Education Committee, Citation2013). Just one example drawn from the United Kingdom will clearly illustrate this. In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, children’s centers are funded by statute in every neighborhood of the country, often attached to primary schools. They are intended as a basic plank of national Early Years policy within local communities, offering both universal (open access) and targeted services for more vulnerable children and parents. Yet recent research on English children’s centers indicated that less than one fourth of centers were offering EBPs in their mix of provision. Of this already small number, little more than 15% followed an EBP “in full,” and the rest followed an EBP only to some degree. In total, only eight different programs (of a list of 23 possibilities) were represented. Most of the services that were being offered by local children’s centers therefore could not be described as firmly evidence-based (Goff et al., Citation2013, p. 103). The extent to which this finding would be replicated in other areas of community-based statutory provision—say, child protection services, intensive family support, out of home care, or juvenile justice—cannot be known at present. Published surveys or audits of the penetration of evidence-based (or even evidence-informed) interventions are notably lacking, both at local or regional levels and nationally. However, though there might be sectoral and geographic variations, most professionals working in community-based services for children and families will probably recognize this picture from English children’s centers as not unrepresentative, even in countries where encouragement and support for implementing EBPs has been relatively high. For example, in work in progress by Saldana and colleagues in the United States, data on sustainment of specific EBP component practices over time through eight stages of implementation completion for four “high-footprint” (widely disseminated) EBPs show that on average, only 37% of practices are sustained in the longer term (with a range of 80% to 32%; Saldana, Citation2015).

The reasons for poor penetration of EBPs within community-based services as usual are many and various, occur at multiple levels, and have been extensively discussed elsewhere (see Chaffin & Friedrich, Citation2004, for a particularly good discussion of the barriers in specific relation to child welfare services). In the particular English example just cited, in the context of increasingly draconian budgetary restrictions in local authorities, the high up-front costs of providing an EBP compared with the costs of other homegrown but less thoroughly researched interventions is likely to be an especially significant consideration, all other arguments aside.Footnote2 Mitchell (Citation2011) also noted the particular limitations created by the intentionally restricted focus of many EBPs, which means there is still an insufficient range of EBPs to cater to the diversity of multiple and overlapping needs found in communities.

However, even had we an affordable, proven program to meet every need, widespread successful uptake of EBPs into services as usual would still, in all likelihood, be limited. This is because even the highest quality EBP can be constrained in its effectiveness by an unaccommodating, inflexible, or impoverished system context. All new interventions are required to take their place within a wider and preexisting system of care. If the existing system is already stressed, if it rejects, obstructs, or even simply fails actively to support a new intervention, and if it does not act as a good “host,” the most promising innovations can easily become marginalized and fail to sustain their promise (Fixsen et al., Citation2005). The United Kingdom provides several such examples in relation to some of the best known EBPs (see, e.g., Berridge, Biehal, Lutman, Henry, & Palomares, Citation2011; Biehal et al., Citation2010; Department for Education, Citation2014; Little et al., Citation2012; Ofsted, Citation2010). Many more are reported only anecdotally or in the gray literature rather than in the scholarly press or in public documents. We are likely to wait a long time if we limit our attempts to improve quality solely to efforts to encourage the uptake of specific, proven interventions.

THE CHALLENGE OF WHOLE SYSTEMS

Clearly, then, if we want to accelerate the adoption of what is known about the principles of effective practice, and to ensure that the rich store of knowledge that we already have about “what works” in specific contexts is taken up into policy and into frontline practice across the board, we need to look beyond individual programs toward a more ambitious, public-health-focused, systemically aware approach to child and family well-being. The focus needs to be on whole system improvement, not just on increasing the availability and uptake of isolated programs for specific populations and specific issues, pressing and important though these may be. However, the challenge of taking a systemic perspective on the barriers to the uptake of knowledge into practice is that whole systems are complex.

A system, as distinct from an individual organization or agency, is defined by its degree of interconnectedness and interdependency, where decisions and actions in one entity are consequential on other neighboring entities. A complex system has been defined as one where “even knowing everything about that system is not sufficient to predict precisely what will happen” and a complex adaptive system is “one in which the system itself learns from experience how to respond most effectively to achieve the desired goals, however much the external circumstances change” (Welbourn, Warwick, Carnell, & Fathers, Citation2012, p. 17; see also Paina & Peters, Citation2012). They consist of multiple, overlapping elements that often defy attempts to bring them into sharper focus. They are characterized by volatility, unpredictability, complexity, and ambiguity (Ghate, Lewis, & Welbourn, Citation2013) and by paradox, defined as “a state in which two diametrically opposing forces/ideas are simultaneously present, neither of which can ever be resolved or eliminated” (Stacey, Citation2006).

Some analyses that draw comparisons between human service systems and living biological systems note that living systems also generally function to regulate or adjust to external threats to stable functioning, in order to reinstate homeostatic stability, and suggest that service systems can be viewed in the same way. Metz and Albers (Citation2014), for example, noted that in human services, “the infrastructure is often invisible to policymakers and funders, program developers and service providers who work to implement evidence-based models. The ‘invisible infrastructure’ reflects and maintains the status quo, which ‘fights back’ and jeopardizes high-fidelity implementation of innovations” (p. 94). It has been noted that when new services are introduced to existing systems, it is often the case that the existing system, even if not actively hostile to the new innovation, will tend to try to neutralize the impact of the innovation, minimizing the threat arising from implied change, and pushing the innovation to the external boundaries where the disruption will be lowest. As one experienced funder from a major philanthropic foundation (as cited in Fixsen et al., Citation2005), put it, “Systems trump programs” (p. 57). Social investors and innovators know well that they ignore systems at their peril.

GETTING FROM PROGRAMS TO SYSTEMS: HOW IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE AND PRACTICE CAN HELP

The still-emerging field of implementation science and practice (ISP) and its close cousins improvement science, innovation science, and dissemination and implementation science may yet hold our best chance of assisting more individual programs to reach long-term sustainability within complex adaptive systems and allowing the valuable learning from work to develop specific model programs to penetrate the world of services as usual. In its most simple definition, implementation is the process of putting an idea (e.g., a policy, a service, a plan for a specific improvement or innovation) into practical use. Its study and practice can be defined as active and planned efforts to deliver specific approaches, interventions, or innovations “of known dimensions” (Fixsen et al., Citation2005) in ways that maximize and preserve their intended effectiveness. Viewed as a process and not an event, implementation can be conceptualized as encompassing a number of linked stages from initial setup, through embedding of an intervention in daily practice, to ongoing efforts to ensure sustainability and continuing effectiveness (Fixsen et al., Citation2005; Saldana, Citation2014). Although some definitions stress that implementation can be thought of only in relation to a clearly defined practice or clearly specified program,Footnote3 ISP is in fact much less concerned with the content of programs (their theory base, their specific practices) and much more concerned with elucidating the mechanisms of effective change in real-world systems contexts. Increasingly, it tends to be less concerned with fidelity and more concerned with effective adaptation (Chambers et al., Citation2013). It focuses on understanding what creates and optimizes the conditions for effectiveness, taking up the journey to outcomes where traditional intervention science leaves off. It builds upon the decades of learning from intervention and prevention science in respect of what approaches are most likely to lead to specific positive outcomes for service users, but it goes further, understanding that the ongoing implementation context for services and interventions is critically determinant of whether those outcomes are in fact achieved and sustained. Next I outline a selection of the key features of an implementation lens that seem to offer most promise for practical efforts to sustain effective practices and programs.

Key Features of an Implementation Lens

Recognizing the invisible infrastructure

A key feature of an implementation science approach and where it departs from traditional approaches to exploring “process” in human service interventions is its attention to the systems context and ecology of service delivery, and the recognition that all services (new or preexisting) connect with a wider system of care—whether or not this is explicitly accounted for in the design. Implementation scholars, in noting that the system can either nurture or crush innovation, realize that attempts to develop, deliver, or study programs as if they existed independently of this infrastructure are unlikely to succeed (Fixsen et al., Citation2005). Thus, exploring, mapping, and understanding the systems context of individual services, including identifying the key stakeholders and understanding how the different elements of the system fit together, are prerequisites to assisting those individual services to function effectively. Integral to this perspective is the idea of “disruptive innovation” (Christensen, Grosman, & Hwang, Citation2009), which posits that innovation necessarily must disturb the system status quo, as is the idea of “beneficial toxicity” as a stimulus to adaptive mechanisms (Welbourn et al., Citation2012). Managing the disturbance so that positive and negative aspects are kept in balance is a key activity for implementers who wish to put an innovation into active and practical delivery, and eventually see it become part of the mainstream, business-as-usual of practice.

This in turn relates to the important twin constructs of system (or “community”) readiness, and systems fit or alignment, and a growing focus on the extent to which existing systems and structures are amenable—or can be made amenable—to particular innovations or improvements. Readiness concerns whether the individual practitioner, her or his agency, or the system in which the agency sits is prepared—mentally, practically, operationally, and strategically—to host a new innovation; fit is concerned with how the innovation will integrate with existing conditions, how positive and negative disturbance will be manifested, and what aspects will create most discomfort and require most tailoring to encourage uptake. Deeper and wider consideration of these issues by implementation analysts is enabling a more critical scrutiny of the permitting conditions for innovation. Critically, viewing innovation planning through this lens encourages service developers to consider carefully the context into which an innovation will be introduced and to consider what accommodations may be required to optimize the chances of adoption. At present, often these insights emerge post hoc, after the discomfort has surfaced. The promise of an ISP approach is that eventually these analyses will become second nature to commissioners and providers before investments in new services are committed. The concept of drivers of implementation (factors that lead to higher quality service delivery; presented next) is an attempt to articulate and make visible the key features of this otherwise often hidden implementation infrastructure.

Co-creation

A second key feature of an implementation approach is the explicit attempt to bridge science and practice not only by exhorting practitioners to put research evidence into application, as in traditional approaches to dissemination and diffusion of innovation, but more challengingly by actively working alongside practitioners and policymakers so that their know-how and experience is harnessed to those of the professional researcher. This is exemplified in the emphasis on the significance of co-creation (or co-construction) in an implementation approach. Co-creation is described in the business literature as a process “deeply involving stakeholders in identifying all dimensions of the problem and designing and implementing solutions” (Pfitzer, Bockstette, & Stamp, Citation2013, p. 4). It is more than just consulting with service users, or sharing findings with groups of practitioners as part of dissemination activities once analysis is concluded. A co-construction approach is threaded through the work of most implementation professionals, who use this method in a number of ways, for example, to work alongside program developers and practitioners to review and further develop the theories of change underpinning their services, check the alignment of activities and outcomes, and in various other ways work to make visible the infrastructure underpinning both long-established and new services. For example, a recent development of interest in improvement science in the United Kingdom is the piloting of a researcher-in-residence model, which attacks “the traditional separation of the producers of the research evidence in academia from the users of that evidence in healthcare organisations” and “positions the researcher as a core member of the delivery team” within a practice organisation rather than as a disconnected external observer (Marshall et al., Citation2014, p. 1).

Integrative methods

Third, an implementation lens is highly integrative. The field is developing along multidisciplinary lines in the widest sense, building upon and thriving through integrating insights from a huge range of fields from engineering, manufacturing, life sciences, and business and management sciences, as well as the more familiar fields of human development, social work, psychology, health, and education (Fixsen et al., Citation2005). Thus, we are currently experiencing a rapidly expanding theoretical literature, a proliferation of frameworks for analysis of implementation issues, and more gradually the development of instruments for empirical testing of implementation conditions and implementation efficacy. Although few of the key preoccupations of this developing literature strike the long-standing student of prevention as entirely surprising, what does strike one as different and fresh is the explicitly integrative, synthetic nature of the implementation discourse. The focus in ISP is on understanding how things fit together, and how, as in a well-functioning system, the optimal balance of opposing forces can be maintained in a reasonably effective (if not wholly harmonious) way. Thus implementation drivers have been described as “integrated and compensatory” (Fixsen et al., Citation2005), meaning that when optimally arranged they complement and reinforce one another, and that weaknesses in one driver may be compensated for by strengths in another. ISP also explicitly recognizes that innovation and improvement are continuous, not static, processes, and readiness not just for initial change but ongoing adjustment is the critical factor in achieving any kind of sustainability. This is not just about “scaling” in the sense of making bigger or improving the reach of individual EBPs but about recognizing that healthy systems contain many moving parts, some big, some small, each specialized to a particular function, and that diversity is not only inevitable but actively desirable for maintaining balance in a complex adaptive context.

Key Implementation Constructs and Their Deployment as Tools for Research and Analysis

Systems architecture and systems awareness

How then can these features of an implementation lens be deployed for practical use in implementation research, analysis, and support? Some of the key constructs emerging from ISP that are proving most useful to our field are already being shaped into methods and tools for research and analysis. Perhaps most significant for our interest in taking successful, one-off programs into successful, sustainable systems interventions are the constructs related to understanding whole systems architecture and systems alignment. Thus one of the first tasks for an implementation professional interested in optimizing the capacity for sustainable impact of a given intervention is to undertake, in collaboration with local stakeholders and experts, an analysis of the system into which the new innovation will be inserted. Stakeholder analyses and network mapping and systems mapping (Aarons, Sommerfield, & Walrath-Greene, Citation2009; Paina & Peters, Citation2012) are processes that allow a new innovation to be viewed from multiple perspectives and allow developers and providers to anticipate how the innovation will align constructively with the existing structures, how it may disturb the existing system in both beneficial and antagonistic ways, and to identify the key agencies and key individual stakeholders whose support and leadership will be critical to the innovation’s success. This involves much more than developing a communications plan and requires would-be innovators to recognize themselves within a co-constructed process that reaches beyond the parameters of their own specific planned program or service. Simple systems maps that show the agencies with whom a new innovation hopes to connect, and perhaps also the agencies with whom it does (and does not) connect once it is up and running, can be extremely enlightening in encouraging service providers to anticipate and name potential roadblocks, understand which constituencies have to be won over, and frame a compelling case for how the new innovation complements and improves the existing whole system rather than serving the narrow agenda of a specific interest group. Active engagement in boundary-crossing systems leadership (Ghate et al., Citation2013) during the early stages of planning as well as during the later stages of delivery is assisted by this process.

Implementation stages

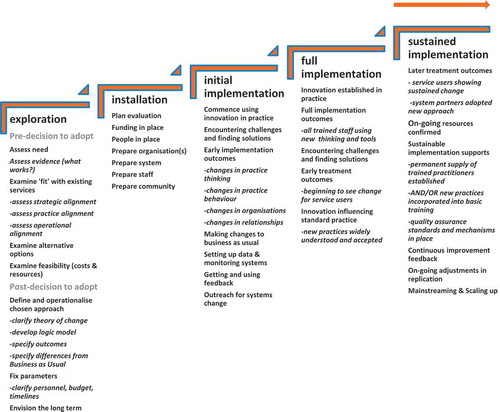

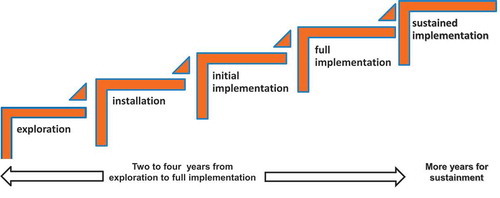

Second, an important construct that forms part of an implementation approach concerns understandings about innovation momentum and process. Thus, the concept of implementation stages (Fixsen et al., Citation2005; Saldana, Citation2014) has already begun to be taken up both as a way of structuring thinking and planning for sustainability and for monitoring and evaluating the progress of innovations. The study of real-world implementation trajectories has revealed that implementation almost always occurs in discernible stages and that critical activities need to be undertaken aligned strategically to the specific stage concerned. Put simply, implementation is a process rather than an event “involving multiple decisions, actions and corrections” along the way (Metz & Albers, Citation2014, p. 93) and has been vividly described by Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, and Kyriakidou (Citation2004) as the “messy, stop-start and difficult to research process of assimilation and routinization” (p. 614). The number of stages identified varies by author: Fixsen et al. (Citation2005), for example, noted four broad stages not including sustained implementation at scale, which can be thought of as a fifth stage; see . Saldana (Citation2014) identifies eight. However all authors agree that it can take several years—typically 2 to 4 years from initial exploration to sustained implementation (Fixsen et al., Citation2005)—and is rarely a sequential linear process but instead is iterative, reiterative, and recursive (e.g., Damschroder et al., Citation2009), frequently involving the revisiting of previous stages, particularly if the groundwork associated with each prior stage has not been adequately completed.

FIGURE 1 Stages of implementation: From exploration to sustainment. Note. Based on Fixsen et al. (Citation2005). © NIRN. Adapted by permission of NIRN. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

Using the concept of implementation stages to assist strategic planning in a forward-looking way makes even the substantial (sometimes overwhelming) ambition of many program developers more manageable; using an implementation stages framework for the analysis of progress, or as an evaluation tool, helps to sharpen the focus and ensure that the expectations of providers, funders, and researchers are realistic. shows, for example, the stages construct as recently used in an evaluation and program development project for a national initiative in foster care improvement for the United Kingdom (Ghate, McDermid, & Trivedi, Citation2014).

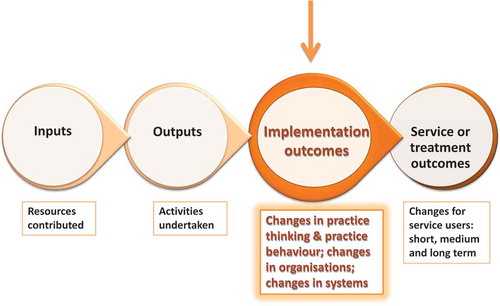

Implementation outcomes

The construct of implementation outcomes has also been brought into sharper focus by means of implementation theory, as distinct from treatment or intervention outcomes (Proctor et al., Citation2011). There is relatively little literature on this subject as yet, and different authors take different standpoints on how implementation outcomes should be defined and measured (Chaudoir et al., Citation2013). However, the basic construct is useful for helping service providers to sharpen their thinking around the nature of the pathways to ultimate impact, and getting providers and funders to recognize that the most critical prior stages on the pathway to the outcomes they consider to be the ultimate goal of intervention are those that are most often neglected: the changes at practitioner, service, and system level that demonstrate that new or changed practices are being properly and effectively employed and supported; see . In the longer term, re-visioning the traditional program logic model to accommodate implementation outcomes as well as treatment outcomes should support better use of scarce resources for impact evaluation. It may help to ensure that no intervention is expensively (and often disappointingly) evaluated for treatment outcomes before “it is proud” and reasonably confident of its potential for effectiveness (Campbell, Citation1993, as cited in Schorr, Citation2003). A more robust focus on the measurement of implementation outcomes would avoid that unfortunate evaluation result, which arises all too frequently, where treatment outcomes are equivocal or negative, but the question left loudly begging is, Did the (prior) practice change necessary to produce the (subsequent) treatment outcomes actually occur?

Implementation drivers

Finally, implementation “drivers” used as categorizations for relevant implementation accelerants at different levels of system ecology (individuals, agencies or organizations, and whole systems) are proving useful as broad frameworks for structuring the analysis of relevant implementation issues in real-world services. The Active Implementation Framework model developed at the National Implementation Research Network in the United States (Blase, Van Dyke, & Fixsen, Citation2013; Metz & Bartley Citation2012; Metz et al., Citation2014) outlines three levels of driver: competency drivers, organization drivers, and leadership capacity drivers; see . Drivers are defined as “building blocks of the infrastructure needed to support practice, organizational and systems change” (Metz & Albers Citation2014, p. 2). Experience suggests that attempts to create definitive generic, globally relevant lists of relevant subcategories of drivers tend to prove problematic, however, because the most significant drivers in play may vary substantially from one intervention and from one systems context to another. Thus, for practical use in the UK service context, for example, substantial adaptations to the basic model often have to be made (e.g., Ghate, Coe, & Lewis, Citation2014). Overall, however, the basic model is a flexible and useful framework both for strategic planning and for analysis and evaluation of the factors necessary to optimize effective implementation ().

BRIDGING SCIENCE AND PRACTICE TO CLOSE THE IMPLEMENTATION GAP: HOW DO WE DO IT?

Flexing the Parameters: Sometimes “How” Matters More Than “What”

It is now widely accepted that the systemic context for social intervention is likely to be both significant for, and a complicating factor in, the adoption of effective practice. Even the best designed programs may fail if the context in which they operate is hostile. It then becomes an unavoidable conclusion that the content of interventions (what is done, as in, what specific practice or therapeutic approaches are utilized) may sometimes be less significant to sustained uptake and effectiveness than the implementation aspects of the intervention (how it is done). This constitutes a major challenge for the fields of intervention and prevention science, which have typically strongly been focused on measuring treatment outcomes (“Did it work?”). To the extent that they have been at all concerned with the implementation aspects (“How did it work?”), they have focused more or less exclusively on measures of fidelity or treatment adherence, and occasionally on practitioner competencies as a moderator of treatment adherence. Yet the evidence of how difficult it is to retain effectiveness across multiple replications and transportations suggests we also need to scrutinize wider aspects of implementation. So, too, do striking findings such as those of Lipsey and colleagues, who found in a review of effective juvenile justice interventions that a well-designed program delivered poorly could be less effective than a less well-designed program delivered well (Lipsey, Howell, Kelly, Chapman, & Carver, Citation2010). This is not to say that content does not matter, just that appropriate content alone does not guarantee results. It is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for effectiveness.

These reflections lead to another conclusion that is increasingly gaining empirical weight: The key elements of sustainable effectiveness are likely to include the extent to which programs can function in context-sensitive ways. This might mean adapting or accommodating to local circumstances, reflecting local practical considerations or significant cultural preferences. Thus a more sophisticated discourse around the construct of “fidelity” is emerging, as the evidence begins to accumulate that the most successful programs are those that facilitate rather than discourage necessary local or cultural adaptations (Forehand, Dorsey, Jones, Long, & McMahon, Citation2010). The importance of theorizing those aspects of content that are fixed (i.e., essential to effectiveness, also referred to as “core components” in the implementation literature; Blase & Fixsen, Citation2013) and those that are variable (i.e., can be modified without compromising effectiveness) is now strongly emerging as a key aspect of the design of effective programs, and a prerequisite for enabling them to be scaled up and/or transported to new and different contexts without losing efficacy. Fetishizing fidelity and program integrity, and advocating slavish “adherence to the manual” (which in any case rests on the possibly erroneous assumption that the original model “as designed” was already optimal; Chambers et al., Citation2013), is increasingly seen as counterproductive. We increasingly recognize that practitioners in the field will modify anyhow, and that, as a practitioner in the real world, constructive use of one’s own clinical and professional skill and judgment is also a key aspect of effective practice (D’Andrade, Austin, & Benton, Citation2008). As Chambers et al. (Citation2013, p. 2) have recently argued, adaptation and “contextually sensitive continuous quality improvement” are in fact required strategies for achieving sustainable real world outcomes. These are essential evolutionary processes and should not necessarily be denigrated as undesirable attributes of “program drift.” Bridging the science to service gap now requires us to explore and understand more thoroughly how these processes can be optimized without compromising effectiveness.

Researching Implementation Factors: Reclaiming the Process Evaluation

For at least a couple of decades now, policymakers, commissioners, and funders of innovative social programs and interventions have been insisting that service providers be evaluated independently as a condition of funding. In recent decades, research effort has been especially strongly focused on impact evaluation and the measurement of treatment outcomes, especially using experimental design (Cartwright & Hardie, Citation2012). To the extent that “process” or “formative” evaluation has been conducted, these have often tended to be undertaken as parallel descriptive pieces, unsystematic in design and execution, rarely driven by strong theory, and rarely strongly analytic in linking back process findings to “outcomes” (except all too often, as post hoc explanations for equivocal or disappointing intervention results). Generally they have not been fashionable or seen as the “main event” in evaluation research for some years. As a result, we find frustratingly little implementation-relevant data reported in the intervention evaluation literature (Forehand et al., Citation2010), though there is a burgeoning literature on implementation itself, as an overarching field of inquiry.

The increasing number of published implementation frameworks convincingly makes the case that drivers of implementation success operate at multiple levels and across multiple dimensions, in complex and shifting relationship to one another (e.g., Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Fixsen et al., Citation2005; Meyers, Durlak, & Wandesman, Citation2012). Thus, the wide range of factors that have to be integrated in any given study and the multiple levels of implementation ecology at which data have to be collected (see ) have often seemed overwhelmingly discouraging and expensive to deliver.

We have been struggling with this problem from some decades. Indeed, as Blase et al. (Citation2013) noted, quoting authors writing in 1975: “Since the beginnings of the field, the difficulties inherent in implementation have discouraged detailed study of the process of implementation. The problems… are overwhelmingly complex and scholars have frequently been deterred by methodological considerations” (p. 1).

Moreover, these considerations can prove especially problematic in the light of a specific difficulty that the implementation research field faces: one that has arisen, ironically, out of the strong focus in recent years associated with the evidence-based movement on researching treatment outcomes using experimental methods. Although there is little doubt that randomized control trials (RCTs) represent the best research technology currently available to social scientists for the identification of direct causal relationships between interventions and their outcomes for service users in specific contexts, unfortunately they prove less than helpful when we want to know how generalizable the results are (i.e., the likely relationship of external to internal validity), or when we want to know the explanation for the outcome. They can illuminate what worked in specified circumstances (internal validity) but not how, or why, it worked, or whether it will work elsewhere (external validity; Cartwright & Hardie, Citation2012). As has been observed for some while, RCTs all too frequently deliver equivocal and contested results that leave funders and providers none the wiser in respect of the decisions they have to make about how to take research learning forward (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). Increasingly disappointed by the low returns on investment of the resources and time attached to the conduct of RCTs in community-based evaluations, a growing number of evaluation scientists are concluding that these methods—at least in isolation—may not serve service funders and providers well (Cartwright & Hardie, Citation2012; Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2011). Certainly the implementation research field has recognized that RCTs are unlikely to be the only, or even the most useful, tool for measuring the effectiveness of implementation strategies. For example, Meyers et al. (Citation2012) concluded, “Because implementation often involves studying innovations in real world contexts, rigorous experimental designs encompassing all of the possible influential variables are impossible to execute” (p. 3). RCTs, involving as they do a high degree of control over the delivery conditions, are rarely feasible—and rarely appropriate—in the complex adaptive systemic context of real-world implementation strategies. Although RCTs strive to reduce real-world complexity to the minimum number of variables, implementation science and practice must of necessity embrace the natural proliferation of complexity and variability found in real-world social contexts. As Greenhalgh et al. (Citation2004) commented 10 years ago,

Context and “confounders” lie at the very heart of the diffusion, dissemination and implementation of complex interventions. They are not extraneous to the object of study; they are an integral part of it. The multiple (and often unpredictable) interactions that arise … are precisely what determine the success of failure of a(n) … initiative. (p. 615)

Thus, many themes that are critical to understanding implementation simply cannot be tackled using the usual toolkit of the evaluation scientist. They certainly cannot all be captured within the straitjacketed “gold standard” of experimental methods. In this respect, bridging the science to service gap will require a more open dialogue between funders, researchers, and providers that acknowledges the need for rigor and robust empirical testing of the claims made by implementation theorists but also accepts that the traditional toolbox of evaluation science in the social intervention field may need reviewing if we are to benefit from the emerging insights of implementation science. RCTs, for all their appearance of sophistication, are unlikely to be able to capture the complex systemic conditions that in reality dictate the success or failure of innovation in community-based interventions. We need to further develop the methods, and expand, not narrow, our standards of rigor.

Developing Active Implementation Support

A third priority is to learn the emerging lessons from implementation studies that show that practitioners need more than access to knowledge to make the changes in behavior that are necessary for sustained effectiveness. Greenhalgh et al.’s (Citation2004) article on diffusion of innovations in service organizations is now regarded as a seminal contribution to the nascent field of ISP, drawing attention as it did to the importance of active strategies to embed innovation in policy and practice and the difference between “letting it happen” (also colloquially known as “train and hope”), “helping it happen” (disseminate and diffuse through information and guidance), and “making it happen” (active, practical implementation support). ISP analysts, observing the gap between what we know and what we do, have trenchantly noted what doesn’t “make it happen”: that disseminationFootnote4 (reports, articles, briefing papers, presentations), diffusion (guidelines; mandated approaches), or training approaches are not effective alone. For example, data from studies on classroom practice (Joyce & Showers, as cited in Fixsen et al., Citation2005) suggest that in particular, practice observation and one-to-one coaching is the essential active ingredient that converts knowledge into demonstrated behaviour change in real-world practice settings. More recent reviews of studies also give increasingly strong empirical support for the combination of training and ongoing technical assistance as a route to better intervention results (Meyers et al., Citation2012). The implication is that if we want to accelerate uptake of evidence-based behavior change by practitioners, we need to get serious about investing in different and more intensive ways of supporting staff that go beyond education and training.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Although students of implementation have claimed the term “science” for their endeavors, the implementation field still has some way to go to become a fully fledged science. For example, we are yet to enter the period when we will have widespread and widely replicated systematic evidence that certain implementation strategies work better than others. There are many frameworks but little standardization in how these are being applied in research or in practice (Chaudoir et al., Citation2013). Moreover, the challenges already noted in respect of the fitness for purpose of orthodox research methodologies will need to be addressed before we will have such data. However, the signs are propitious. In recent years much of the attention has been on the development of theoretical frameworks that can be used to structure the analysis of implementation-relevant explanations for the success or failure of given initiatives or interventions. A review of the international multidisciplinary literature by the National Implementation Research Network (Fixsen et al., Citation2005) distilled a set of core principles and constructs on which much of the existing implementation literature is still based. Since then, numerous other theoretical frameworks have been published (e.g., Berkel, Mauricio, Schoenfelder, & Sandler, Citation2011; Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Durlak & DuPre, Citation2008; Meyers et al., Citation2012), and over the coming years we can expect to see increasing consensus around the core elements of these. As the field moves forward, around the world various groups are developing and testing tools for the measurement of implementation-relevant factors, and specialized implementation research and support centers and groups are springing up around the globe. The methodologies are still very much in evolution, and we need faster progress toward robust empirical studies that test the utility of these frameworks, and in particular that test different approaches to implementation and assess differential pathways to effectiveness. Yet we can be hopeful that over the next few years as the field matures, a distinctive, co-constructed, practically focused science of implementation will gain widespread attention, including in Europe where the field is still relatively new. This will build upon, but undoubtedly look somewhat different to, intervention and prevention science as we currently know them.

Perhaps one of the main ways in which it will look different is that ISP offers a clear mandate for scientific enquiry and practice testing and development to work together, as integrated and parallel rather than as separate, sequential processes. It is critically defined by “doing with,” not “doing for.” Implementation scientists need to be prepared to see themselves as active real-time contributors to success, not just post hoc reporters on a process carried out by others. It also critically emphasizes the importance of active implementation support in the form of specially skilled teams who can put science into the service of practice and policy, drawing upon existing evidence, collecting relevant new data, and translating this into practical help for those on the ground at planning or provider levels. ISP recognizes that rigorous, systematic, and scholarly endeavor and practical, pragmatic, problem-solving, hands-on involvement are required for us to make progress in creating sustainable improvement in human services. It increasingly recognizes the limitations of an overemphasis on traditionally narrow orthodoxies of top-down, researcher-driven methods in both intervention design (Chambers et al., Citation2013) and evaluation (Meyers et al., Citation2012). It thereby promises a framework for the integration of best evidence with the know-how of policy and practice and attempts to synthesize these into a recipe for optimizing effectiveness. In the process, it may be necessary to entertain “a trade-off between knowing a few things very well and more things with less certainty” (Sawhill, as cited in Schorr, Citation2003 p. 2).

In terms of potential benefits for the field, the increasing application of an implementation lens has the potential to change the way we carry out needs analyses, how we assess the goodness of fit between favored approaches and the actual contexts in which they will be delivered, how we assess the feasibility of delivery, and how we evaluate impact and scalability. The implementation research community is now turning the spotlight away from the content of effective practices (“what works”) toward the determinants of effective practice (“how works,” “why works”). Understanding more about how “systems trump programs” will in turn lead to a greater understanding of how we assess system readiness to support innovation and how funders and commissioners with system-wide influence can work to ensure the results of their “point” interventions are not undermined or diluted.

Learning how organizational supports can increase the efficacy of on-the-ground practice behavior is opening the door to multidisciplinary teams that combine research and practice to support provider organizations to get more out of the funding they receive. It is heartening to see increasing examples of policy and commissioning bodies recognizing that service providers need not just funding to innovate but support to implement innovation and sustain it over time.Footnote5 The concept of multidisciplinary “Implementation Teams,” both publically and privately funded, who work on the ground to support local providers across a wide range of implementation challenges is gaining credibility and looks set to become an established and thriving area of provision, as evidence emerges of success in promoting enhanced outcomes for service users (Metz et al., Citation2014) . Typically, teams are multidisciplinary, containing experienced researchers, practitioners, and organizational change-management professionals. They focus on matters such as implementation drivers (quality integration and sustainability), data for decision making, (needs, fidelity, outcomes), organizational and systems factors (capacity development, structures, alignment, policy), and problem solving (regular support, troubleshooting, brokering). Notably, some of the efforts in Europe are focusing not just on the “proven” evidence-based interventions (EBIs) but on translating implementation science and practice know-how to support the improvement of services as usual and local innovations that are evidence-informed but not fully evidence-based.Footnote6 They are also using an implementation lens to support ongoing commissioning decisions. Although still not achieving instantaneous results, hands-on expert implementation teams are reported to support more uptake of effective practice, faster, when compared with more passive “letting it happen” approaches (Metz et al., Citation2014).

As implementation science and practice begins to gain credibility and demonstrate—especially to commissioners and funders—its usefulness in creating sustainable effectiveness, we can expect to see research efforts expanding to accommodate a focus on empirical testing of implementation constructs and principles alongside studies of treatment outcomes. The growing number of implementation frameworks that are developing around the world are providing us with detailed and richly populated lists of factors that may be important in explaining implementation success or failure. Used more systematically, they are likely to enrich our ability to analyze the conditions that optimize pathways to effective treatments. They provide, even at this early stage of the field’s development, promising ways to restructure the approach to process or formative evaluation so that it is more systematic and more insightful. We can also expect to see approaches and technologies developing amongst funders and researchers, as well as practitioners, developers, and providing agencies that treat contextual variability as an integral part of the success of innovation rather than as an undermining factor that has to be “controlled out” of the picture (Chambers et al., Citation2013; Paina & Peters, Citation2012; Peters, Adam, Alonge, Agyepong, & Tran, Citation2013). As knowledge and understanding grows of the importance of implementation outcomes for predicting treatment outcomes, we can expect to be better placed for scaling up evidence-based practice, as we learn better how to take existing effective practice and make it work equally well in a wider variety of contexts and systems. This will help assist the vast majority of services to children (“services as usual”) to learn better how to optimize their practice as they continue on an evidence-informed, even if not wholly evidence-based, journey toward becoming more solidly rooted in understanding of “what works.”

Finally—and with apologies for the pun—the unavoidable conclusion is that we may now have to address the “rigor mortis” that we may have (unintentionally) encouraged in recent years through an overly narrow focus on approved EBIs, through a narrow preoccupation with fidelity as the main explanatory factor behind interventions that fail, and by insisting on delivery strategies and overly restrictive research designs that cannot capture complex adaptive contexts. It is a question not just of accelerating the uptake of existing research knowledge but of expanding the scope of knowledge that we seek. This means expanding the methods that we use. Closing the gap between research and practice requires us to come to terms with the need for adaptability and flexibility in real-world practice settings. In the search for silver bullets, we may have been fetishizing individual programs and the scaling up of these as catch-all solutions. But the reality is that we fund and deliver interventions in complex adaptive systems where the only thing that is predictable is constant change and challenge. “Fidelity” in this context may be an illusion: We need clearer parameters within which adaptive responses can be made. To achieve sustainability in complex adaptive systems, we need adaptive interventions and adaptive research strategies. In this context, rigor should not mean inflexibility; it should mean “evidence-informed adaptation,” and putting the tools of science into the service of practice as thoughtfully and creatively as possible. The sooner EBI developers and researchers get our heads around this, the better and faster we can work together toward sustained, real-world effectiveness.

Notes

1 For example, see this extract from the Blueprints for Violence Prevention website (http://www.colorado.edu/cspv/blueprints/): “WHAT IS THE KEY FACTOR IN IMPLEMENTING EVIDENCE-BASED PROGRAMS? Blueprints advocate for faithful replication of proven prevention programs—otherwise known as implementation fidelity. When communities ‘tweak’ a program to suit their own preferences or circumstances, they wind up with a different program whose effectiveness is unknown. Evidence-based programs have produced better outcomes when implemented with fidelity.”

2 For example, the per-parent cost of attendance on a leading U.S.-developed EBP (Incredible Years®) works out at approximately two and half times that of attendance at a popular UK-developed parenting support program (the Family Links Nurturing Programme) of comparable length (approximate estimate only; figures derived from costs provided in Goff et al. (Citation2013), based on a sample of local authorities in England, and Simkiss et al. (Citation2013), based on a sample of local authorities in Wales.

3 For example, Fixsen et al. (Citation2005) define implementation as “a specified set of activities intended to put into practice the programme or intervention of known dimensions” (p. 5).

4 Terms are used here in the following senses: dissemination (the “scattering of ideas” and spreading of information, or knowledge by written or oral means), as contrasted with diffusion activities (active encouragement to adopt specific innovative practices) and implementation activities (applying the learning in specific local contexts to change behaviors across the system). Dissemination and diffusion can influence thinking and intentions; implementation, on the other hand, influences practice on the ground.

5 This may include funding the costs of intermediary or purveyor services provided directly by or under license from the developers of EBIs, but other significant examples (in Europe) include access to paid-for implementation support from specialist implementation centers and access to nationally funded assistance to implement related suites of EBPs (e.g., in the United Kingdom, http://evidencebasedinterventions.org.uk/about/national-implementation-service; http://www.cevi.org.uk; and in Ireland, http://www.effectiveservices.org).

6 Terms used here in the following senses: evidence-based—consistently shown to produce positive results by independent research studies conducted to a high degree of scientific quality; evidence-informed—based on the integration of experience, judgment, and expertise with the best available external evidence from systematic research.

REFERENCES

- Aarons, G. A., Sommerfield, D. H., & Walrath-Greene, C. M. (2009). Evidence-based practice implementation: The impact of public versus private sector organization type on organizational support, provider attitudes, and adoption of evidence-based practice. Implementation Science, 4, 83. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-83

- Berkel, C., Mauricio, A. M., Schoenfelder, E., & Sandler, I. (2011). Putting the pieces together: an integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science, 12, 23–33. Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/content/p006g4608861w2t8/fulltext.pdf

- Berridge, D., Biehal, N., Lutman, E., Henry, L., & Palomares, M. (2011). Raising the bar? Evaluation of the social pedagogy pilot programme in residential children’s homes (DfE RR148). London, UK: Department for Education.

- Biehal, N., Dixon, J., Parry, E., Sinclair, I., Green, J., Roberts, C., … Roby, A. (2010). The care placements evaluation (CaPE) evaluation of multidimensional treatment foster care for adolescents (MTFC-A) (DfE RR 194). London, UK: Department for Education.

- Blase, K. (2012, March). Bridging the gap from good ideas to great services: The role of implementation. Paper presented to the Children’s Improvement Board Policy Innovation Workshop, Westminster, London, UK. Retrieved from http://www.cevi.org.uk/conferences.html

- Blase, K., & Fixsen, D. (2013, February). Core intervention components: Identifying and operationalizing what makes programs work (ASPE Research Brief). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/13/KeyIssuesforChildrenYouth/CoreIntervention/rb_CoreIntervention.cfm

- Blase, K. A., Van Dyke, M., & Fixsen, D. (2013). Implementation drivers: Assessing best practices. Chapel Hil, NC: University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, The National Implementation Research Network. Retrieved from http://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/resources/implementation-drivers-assessing-best-practices

- Campbell, D. T. (1993). Problems for the experimenting society in the interface between evaluation and service providers. In S. L. Kagan, D. R. Powell, B. Weissbourd, & E. F. Ziegler (Eds.), America’s family support programs: Perspectives and prospects (pp. 345–350). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2, 40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-2-40

- Cartwright, N., & Hardie, J. (2012). Evidence-based policy: A practical guide to doing it better. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Chaffin, M., & Friedrich, B. (2004). Evidence-based treatments in child abuse and neglect. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 1097–1113. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.08.008

- Chamberlain, P. (2003). The Oregon multidimensional treatment foster care model: Features, outcomes, and progress in dissemination. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10, 303–312. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80048-2

- Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8, 117. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-117

- Chaudoir, S. R., Dugan, A. G., & Barr, C. H. I. (2013). Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: A systematic review of structural, organisational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implementation Science, 8, 22. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-22

- Christensen, C., Grosman, J. H., & Hwang, J. (2009). Innovator’s prescription. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsch, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- D’Andrade, A., Austin, M. J., & Benton, A. (2008). Risk and safety assessment in child welfare. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 5, 31–56. doi:10.1300/J394v05n01_03

- Daro, D. (2010, December). Replicating evidence-based home visiting models: a framework for assessing fidelity Mathematica Policy Research (Brief 3). Retrieved from http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/~/media/publications/PDFs/earlychildhood/EBHV_brief3.pdf

- Department for Education. (2013, May 3). New randomised controlled trials will drive forward evidence-based research [ Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-randomised-controlled-trials-will-drive-forward-evidence-based-research

- Department for Education. (2014, March 27). Children’s social care services in Birmingham: Ways forward. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-social-care-services-in-birmingham-ways-forward

- Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327–350. Retrieved from http://www.springer.com/psychology/community+psychology/journal/10464?hideChart=1#realtime

- Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI Publication No. 231). Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network. Retrieved from http://www.fpg.unc.edu/~nirn/resources/publications/Monograph/

- Forehand, R., Dorsey, S., Jones, D. J., Long, N., & McMahon, R. J. (2010). Adherence and flexibility: They can (and do) coexist! Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 258–264. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01217.x

- Ghate, D., Coe, C., & Lewis, J. (2014). My baby’s brain in Hertfordshire: An independent evaluation of phase two. Hertford, UK: Hertfordshire County Council. Retrieved from http://www.hertsdirect.org/mybabysbrainevaluation

- Ghate, D., Lewis, J., & Welbourn, D. (2013). Systems leadership: Exceptional leadership for exceptional times. Nottingham, UK: The Virtual Staff College. Retrieved from http://www.virtualstaffcollege.co.uk/dcs-leadership-provision/systems-leadership/

- Ghate, D., McDermid, S., & Trivedi, H. (2014). The Head Heart Hands Programme: Evaluation of the implementation of the first year (Unpublished report). Fostering Network, United Kingdom.

- Gilliam, W. S., & Leiter, V. (2003, July). Evaluating early childhood programs: Improving quality and informing policy zero to three. Retrieved from http://main.zerotothree.org/site/DocServer/vol23-6a.pdf?docID=2470

- Goff, J., Hall, J., Sylva, K., Smith, T., Smith, G., Eisenstadt, N., … Chu, K. (2013, July). Evaluation of Children’s Centre’s in England (ECCE) – Strand 3: Delivery of family services by Children’s Centres (DfE Research Report No. DFE-RR297). London, UK: Department for Education. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evaluation-of-childrens-centres-in-england-ecce

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., & Kyriakidou, O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organisations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82, 581–629. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

- Hammersley, M. (2005). Is the evidence-based practice movement doing more harm than good? Reflections on Iain Chalmers’ case for research-based policy making and practice. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 1, 85–100. doi:10.1332/1744264052703203

- Henggeler, S. W. (2003). Multisystemic therapy: An overview of clinical procedures, outcomes, and policy implications. Child Psychology and Psychiatry Review, 4, 2–10. doi:10.1111/1475-3588.00243

- House of Commons Education Committee. (2013). Foundation Years: Sure Start children’s centres Fifth Report of Session 2013–14 Volume 1. Retrieved from http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmeduc/364/364.pdf

- Lipsey, M. W., Howell, J. C., Kelly, M. R., Chapman, G., & Carver, D. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of juvenile justice programs. A new perspective on evidence-based practice. Washington, DC: Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, Georgetown, University.

- Little, M., Berry, V., Morpeth, L., Blower, S., Axford, N., Taylor, R., … Tobin, K. (2012). The impact of three evidence-based programs delivered in public systems in Birmingham UK. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 6, 260–272.

- Marshall, M., Pagel, C., French, C., Utley, M., Allwood, D., Fulop, N., … Goldmann, A. (2014). Moving improvement research closer to practice: The Researcher in Residence model. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23, 801–805. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002779

- Metz, A., & Albers, B. (2014). What does it take? How federal initiatives can support the implementation of evidence-based programs to improve outcomes for adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, S92–S96. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.025

- Metz, A., & Bartley, L. (2012). Active implementation frameworks for program success: How to use implementation science to improve outcomes for children. Zero to Three March 2012

- Metz, A., Bartley, L., Ball, H., Wilson, D., Naoom, S., & Redmond, P. (2014). Active Implementation Frameworks for successful service delivery: Catawba county child wellbeing project. Research on Social Work Practice, 25, 415–422. doi:10.1177/1049731514543667

- Meyers, D. C., Durlak, J. A., & Wandesman, A. (2012). The Quality implementation framework: A synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50, 462–480. doi:10.1177/104973151454366

- Mitchell, P. F. (2011). Evidence-based practice in real world services for young people with complex needs: New opportunities suggested by recent implementation science. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 207–216. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740910003373

- NESTA. (2011). Ten steps to transform the use of evidence (Weblog post). Retrieved from http://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/day-3-debunking-myths-about-randomised-control-trials-rcts

- Ofsted (2010, June). And the care quality commission inspection of safeguarding and looked after children services: Birmingham. London, UK: Ofsted. Retrieved from www.ofsted.gov.uk

- Olds, D. (2006). The nurse–family partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal Special Issue: Early Preventive Intervention and Home Visiting, 27, 5–25. doi:10.1002/imhj.20077

- Paina, L., & Peters, D. H. (2012). Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy and Planning, 27, 365–373. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr054

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. London, UK: Sage.

- Peters, D. H., Adam, T., Alonge, O., Agyepong, A., & Tran, N. (2013). Implementation research: What is it and how to do it. BMJ, 347. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6753

- Pfitzer, M., Bockstette, V., & Stamp, M. (2013, September). Innovating for shared value. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from http://hbr.org/2013/09/innovating-for-shared-value/ar/pr

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., … Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Heath and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 65–76. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Saldana, L. (2014). The stages of implementation completion for evidence-based practice: Protocol for a mixed methods study. Implementation Science, 9, 43. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-9-43

- Saldana, L. (2015, May). Guiding organizations towards successful implementation: building an evidence-based strategy for implementation assessment and feedback. Paper presented to the Biennial Global Implementation Conference, Dublin, Ireland. Retrieved from http://gic.globalimplementation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015-presentation-slides/GIC_Saldana_keynote_v02.pdf

- Saunders, M. (1999). Triple p-positive parenting program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2, 71–90. doi:10.1023/A:1021843613840

- Schorr, L. B. (2003). Determining “What Works” in social programs and social policies: Toward a more inclusive knowledge base. Retrieved from http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2003/02/26poverty-schorr

- Simkiss, D. E., Snooks, H. A., Stallard, N., Kimani, P. K., Sewell, B., Fitzsimmons, D., … Stewart-Brown, S. (2013). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a universal parenting skills programme in deprived communities: Multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 3, e002851. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002851

- Stacey, R. (2006). Learning as an activity of interdependent people. In R. MacIntosh, D. MacLean, R. Stacey, & D. Griffin (Eds.), Complexity and organization: Readings and conversations (pp. 237–246). London, UK: Routledge.

- Stewart-Brown, S., Anthony, R., Wilson, L., Winstanley, S., Stallard, N., Snooks, H., & Simkiss, D. (2011). Should randomised controlled trials be the ‘‘gold standard’’ for research on preventive interventions for children? Journal of Children’s Services, 6, 288–235. doi:10.1108/17466661111190929

- Webster-Stratton, C. (2001). The Incredible Years program: Blueprints. Boulder: Violence Prevention Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado at Boulder.

- Welbourn, D., Warwick, R., Carnell, C., & Fathers, D. (2012). Leadership of whole systems. London, UK: Kings Fund. Retrieved from http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/leadership-engagement-for-improvement-nhs