Abstract

Educators detect and intervene in a small proportion of bullying incidents. Although students are present when many bullying episodes occur, they are often reluctant to intervene. This study explored attributes of antibullying (AB) programs influencing the decision to intervene. Grade 5, 6, 7, and 8 students (N = 2,033) completed a discrete choice experiment examining the influence of 11 AB program attributes on the decision to intervene. Multilevel analysis revealed 6 latent classes. The Intensive Programming class (28.7%) thought students would intervene in schools with daily AB activities, 8 playground supervisors, mandatory reporting, and suspensions for perpetrators. A Minimal Programming class (10.3%), in contrast, thought monthly AB activities, 4 playground supervisors, discretionary reporting, and consequences limited to talking with teachers would motivate intervention. Membership in this class was linked to Grade 8, higher dispositional reactance, more reactance behavior, and more involvement as perpetrators. The remaining 4 classes were influenced by different combinations of these attributes. Students were more likely to intervene when isolated peers were included, other students intervened, and teachers responded quickly. Latent class analysis points to trade-offs in program design. Intensive programs that encourage intervention by students with little involvement as perpetrators may discourage intervention by those with greater involvement as perpetrators, high dispositional reactance, or more reactant behavior.

Students subjected to bullying experience adverse health outcomes (McDougall & Vaillancourt, Citation2015). Schools represent an ideal setting in which to address bullying and a related set of prevention and health promotion goals (Langford et al., Citation2015). Although bullying often occurs at school, teachers intervene in a small proportion of these incidents (Craig, Pepler, & Atlas, Citation2000). Students, in contrast, witness bullying on their playgrounds, in their classrooms, or on the Internet (Craig et al., Citation2000). Their response plays an important role in the course of these incidents (Salmivalli, Voeten, & Poskiparta, Citation2011). In Grades 1–6, bullying stopped on 57% of the occasions when students intervened (Hawkins, Pepler, & Craig, Citation2001). Bullying is less frequent when bystanders report these incidents to teachers (Cortes & Kochenderfer-Ladd, Citation2014) or support, defend, and encourage students who are targets of bullying to report these incidents to teachers (Saarento, Boulton, & Salmivalli, Citation2015; Salmivalli et al., Citation2011). In a longitudinal study, antibullying (AB) responses, such as telling perpetrators to stop or asking an adult to intervene, predicted a reduction in bullying (Nocentini, Menesini, & Salmivalli, Citation2013). Teachers are more likely to intervene (e.g., provide coaching or support) when informed of bullying incidents by students (Novick & Isaacs, Citation2010). Targeted students who are “supported, comforted, or defended” by at least one peer report greater self-esteem, enjoy higher social status, and are less likely to be targeted than undefended students (Sainio, Veenstra, Huitsing, & Salmivalli, Citation2011, 146).

AB programs often encourage bystanders witnessing bullying to speak out, notify teachers, or seek help from other adults (Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, Citation2012). Although AB programs generate small increases in bystander intervention (Polanin et al., Citation2012), students are often reluctant to intervene or report these incidents (Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016; O’Connell, Pepler, & Craig, Citation1999; Oliver & Candappa, Citation2007). For example, in a study of 2,437 students, 40% of those experiencing bullying had not informed an adult (Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004). In a Finnish study of KiVa, an example of the evidence-based AB programs that have targeted bystander behavior (Polanin et al., Citation2012), students were more likely to defend targets than were those in control schools (Karna et al., Citation2011). These improvements, however, were not statistically significant at the school year’s end (Karna et al., Citation2011).

The decision to seek help when bullying occurs is associated with demographic and developmental factors. Girls are more likely than boys (Batanova, Espelage, & Rao, Citation2014; Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004), and younger students more likely than older students, to seek help (Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004; Williams & Cornell, Citation2006), report bullying (Batanova et al., Citation2014; Trach, Hymel, Waterhouse, & Neale, Citation2010), or defend targeted students (Karna et al., Citation2011). By Grades 6–8, students consider reporting to be less helpful than do their teachers (Crothers & Kolbert, Citation2004). Students fear that reporting may damage their reputation or trigger retaliation (Oliver & Candappa, Citation2007). Those intervening evidence higher empathy, moral engagement, and defender self-efficacy (Gini, Albiero, Benelli, & Altoe, Citation2008; Pronk, Goossens, Olthof, De Mey, & Willemen, Citation2013; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013; Thornberg, Wänström, Hong, & Espelage, Citation2017). Students who have been targeted (Batanova et al., Citation2014; Pozzoli, Gini, & Vieno, Citation2012; Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004) or suffer significant emotional distress (Sulkowski, Bauman, Dinner, Nixon, & Davis, Citation2014) are more likely to intervene or seek help.

Consistent with an ecological systems analysis (J. S. Hong & Espelage, Citation2012), the decision to intervene reflects the influence of the broader social context in which AB programs are conducted. Students who perceive their schools to be less supportive (Eliot, Cornell, Gregory, & Fan, Citation2010), themselves to be less connected to their schools (Sulkowski et al., Citation2014), or their schools to be more tolerant of bullying are less likely to report being targeted to parents or adults at school (Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004). The hesitancy to intervene may be compounded if intervention by peers (Barhight, Hubbard, Grassetti, & Morrow, Citation2017), or the presence of adult supervisors, diffuses the sense of responsibility for responding to these incidents (Fischer et al., Citation2011).

Finally, student intervention appears to be influenced by the design and conduct of AB programs. Students are concerned that teachers will not deal with reports of bullying, will respond ineffectively, or will compound these problems (Bradshaw & Sawyer, Citation2007; Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016; DeLara, Citation2012; Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004). A study of the KiVa AB program in the United States reported that, although a latent variable reflecting the number of lessons delivered, the percentage of activities conducted, and the time devoted to the program predicted increases in peer-reported efforts to stop perpetrators or support targets, peers reported no change in efforts to get help from adults (Swift et al., Citation2017).

Focus groups with 97 Grade 5–8 students conducted to inform the current study’s design suggested that some attributes of AB programs (e.g., strongly worded AB messages, repetitive programming, or punitive consequences) elicited responses which could undermine AB activities (Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016). Participants described students who were reluctant to participate, disrupted presentations, discredited presenters, or targeted peers as a show of defiance following AB activities (Cunningham, Cunningham, Ratcliffe, & Vaillancourt, Citation2010; Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016). These responses are consistent with psychological reactance theory, which postulates that strong persuasive programming may prompt an effort to reassert control that could undermine prevention intiatives (Grandpre, Alvaro, Burgoon, Miller, & Hall, Citation2003; Rosenberg & Siegel, Citation2017; Wiium, Aarø, & Hetland, Citation2009).

The Current Study

Despite this evidence, several important gaps in the literature need to be addressed. First, although many AB programs attempt to engage bystanders (Evans, Fraser, & Cotter, Citation2014), effect sizes are small with fewer than 50% reporting significant improvements (Polanin et al., Citation2012). Meta-analyses conclude that best practices for increasing bystander intervention have not been established (Polanin et al., Citation2012). As such, studies identifying the relative influence of different features of AB programs on bystander intervention would be helpful (Polanin et al., Citation2012; Pozzoli et al., Citation2012; Swift et al., Citation2017). In this study, therefore, we used choice methods from economics (de Bekker-Grob, Ryan, & Gerard, Citation2012) and marketing research (Orme, Citation2014) to study the decision to intervene. Using a discrete choice experiment (DCE), we estimated the relative influence of 11 program design attributes on the intent to intervene by speaking up, reporting bullying, or asking an adult for help. DCEs are predicated on random utility theory (Hauber et al., Citation2016), which proposes that choices, such as the decision to intervene, reflect the combined influence of the individual attributes composing AB programs. The decision to intervene, for example, might be influenced by the frequency of AB activities, the number of playground supervisors, or the promptness of the school’s response to reported incidents. We extended an earlier study of the general AB program preferences of students (Cunningham, Vaillancourt, Cunningham, Chen, & Ratcliffe, Citation2011) by focusing specifically on the decision to intervene. We included a larger sample (N = 2,033), examined age as a covariate, and controlled for the multilevel design of the study. Participants chose between hypothetical AB programs created by experimentally manipulating combinations of design elements. In addition to an experimental manipulation of the components of hypothetical AB programs, this approach has several advantages. Students provide an important perspective on the design trade-offs AB program planners must consider. Complex choices are, moreover, likely to trigger the decision-making heuristics and cognitive biases influencing playground behavior (Fontaine & Dodge, Citation2006) and to reduce the self-presentation biases (Caruso, Rahnev, & Banaji, Citation2009) that color student responses to rating scales (Salmivalli, Karhunen, & Lagerspetz, Citation1996).

Second, small effect sizes suggest that AB programming increases intervention by some students but not others (Polanin et al., Citation2012). Understanding individual differences in the extent to which the components of AB programs influence the decision to intervene could inform the tailoring of AB programs that engage a greater proportion of bystanders. This study, therefore, used latent class analysis (Lanza & Rhoades, Citation2013; Zhou, Thayer, & Bridges, Citation2018) to identify groups of students whose intervention decisions were influenced by different features of AB programs.

Third, Yeager, Fong, Lee, and Espelage (Citation2015) proposed a link between psychological reactance and an apparent decline in the effectiveness of AB programs among older students. Qualitative studies confirm that some students resist the influence of AB initiatives (Cunningham et al., Citation2010; Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016). Psychological reactance, moreover, increases during a period in which the effectiveness of AB programs may decline (Grandpre et al., Citation2003). Although psychological reactance is thought to have limited the impact of a range of prevention initiatives (Bushman, Citation2006; Legault, Gutsell, & Inzlicht, Citation2011; Wiium et al., Citation2009), there is virtually no research on psychological reactance to AB programs. Using a measure based on examples identified by Grade 5–8 students (Cunningham et al., Citation2010; Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016), we examined the association between latent class membership, psychological reactance, and dispositional reactance—a general tendency to resist persuasive efforts (S. M. Hong & Page, Citation1989; Miller, Burgoon, Grandpre, & Alvaro, Citation2006).

Fourth, middle school marks a period when bullying increases (Bradshaw & Sawyer, Citation2007), older students are less likely to intervene (Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004; Williams & Cornell, Citation2006), reporting decreases (Trach et al., Citation2010), psychological reactance increases (Grandpre et al., Citation2003), and the effectiveness of AB programs appears to decline (Yeager et al., Citation2015). We know little about shifts in the features of AB programs influencing intervention at different points during this period. Therefore, we examined the link between Grades 5 through 8 and membership in latent classes whose decision to intervene is influenced by different features of AB programs.

We addressed five research questions.

RQ1: Are there groups of students whose intervention decisions are influenced by different attributes of AB programs?

We anticipated that multilevel latent class analysis (Vermunt, Citation2008) would identify clusters of students whose intervention decisions were influenced by different attributes of AB programs. Given studies revealing that latent clusters of students preferring high-, moderate-, and low-impact AB programs (Cunningham et al., Citation2011), we predicted that class membership would be influenced by measures of program intensity such as the frequency of AB activities, the number teachers supervising playgrounds, and the consequences incurred by perpetrators.

RQ2: Which attributes of AB programs influence the decision to intervene?

We anticipated variation in the relative influence of different attributes of AB programs on the decision to intervene. Given the frequency with which focus groups discussed the plight of isolated students, we postulated that students would be more likely to intervene in schools where support for isolated peers was high (Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016). Rewards for the prevention of bullying, in contrast, exerted little influence on design preferences (Cunningham et al., Citation2011). We anticipated that rewards would exert less influence on student intervention.

RQ3: Is the decision to intervene linked to grade?

Given evidence that psychological reactance to prevention programming increases during the middle school years (Grandpre et al., Citation2003), older students are less likely to intervene (Unnever & Cornell, Citation2004; Williams & Cornell, Citation2006), and the effectiveness of AB programs declines with age (Yeager et al., Citation2015), we anticipated grade-related differences in the components of AB programs influencing the decision to intervene. Assuming agency is increasingly important to older students, we predicted that Grade 8 students would reside in latent classes that were more likely to intervene with less intensive AB programming (e.g., less frequent AB activities, fewer playground supervisors, and discretionary reporting policies).

RQ4: Is bullying involvement linked to latent class membership?

A previous study suggests that students involved as bystanders, targets, or perpetrators would view AB program design from different perspectives (Cunningham et al., Citation2011). We predicted that students involved as perpetrators would be more likely to reside in latent classes that intervened when schools limited the frequency of AB activities, reduced supervision, and minimized consequences.

RQ5: Is psychological reactance linked to latent class membership?

We predicted that students in latent classes who were more likely to intervene when programming was less intensive (e.g., less frequent programming, fewer playground supervisors, less serious consequences) would report more psychological reactance to AB programs and greater dispositional reactance.

Method

Participants

This study was approved by the University/Hospital Research Ethics Board and the participating school boards. We contacted the public and Catholic school boards in an ethnically and economically diverse industrialized urban Canadian community of 530,000 residents. Both agreed to participate. Schools were grouped into five clusters representing the region’s demographic range. Using a stratified random strategy we selected 42 schools with classes ranging from junior kindergarten (ages 3–5) to Grade 8 (age 12 to 14). Median family income in the area where each school was located ranged from $39,050 to $112,506 (Mdn = $74, 021; DeLuca, Johnston, & Buist, Citation2012). The percentage of immigrants ranged from 11% to 48% (Mdn = 22%). According to Statistics Canada, median family income for the community was $94,976 and 24.1% were immigrants.

School boards sent an introductory letter to the schools selected. Of 36 principals we were able to contact, 30 participated. We randomly selected one Grade 5, 6, 7, and 8 class at each school; visited each class; described the project to students; and, via students, sent a consent letter to parents. Students returning parent consent forms received a pack of sugarless gum. If parents consented, students completed an assent stating the survey was voluntary, was anonymous, and could be terminated at any time. Of an estimated 2,985 letters to parents, 2,359 consents were returned; 2,181 allowed their child to participate; 2,050 students were present on the day surveys were completed; 2,039 students assented; and 2,033 completed the survey (overall = 68.1%) .

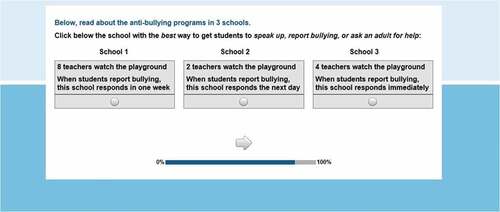

Discrete Choice Experimental Survey Design

The design of the DCE addressing RQ1 and RQ2 is consistent with guidelines (Johnson et al., Citation2013). We derived attributes of AB programs (see ) from focus groups with 97 Grade 5–8 students. Focus group methods are detailed separately (Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016). We selected attributes that were (a) recurrent focus group comments, (b) linked by students to program effectiveness and (c) judged to be actionable targets for program improvement. Given limitations in the number of attributes that can be included in DCEs, we used a consensual process to reduce candidate attributes to 11. Attributes included the frequency, content, and interest level of AB activities; the number of playground supervisors; the extent to which peers reported bullying; the promptness of responses when incidents were reported; and the consequences incurred by perpetrators. Next, we created three levels that described a realistic range for each attribute. Playgrounds, for example, could be supervised by two, four, or eight teachers. The survey was piloted to ensure that each attribute’s levels could be combined logically with those of other attributes (Johnson et al., Citation2013). An experimental design algorithm (Sawtooth Software, Citation2013) generated 13 choice tasks for each participant (). Each choice task presented the AB programs at three hypothetical schools. Participants chose the school at which students would be most likely to speak up, report bullying, or seek help from an adult. Because students engage in less impression management when sensitive questions are posed indirectly, responses to this format may better reflect their views (Fisher, Citation1993). Each school was described by two attributes (). Describing the hypothetical schools with a subset of the study’s attributes is a partial profile design (Chrzan, Citation2010). In comparison to full profile designs, where each option would be described by 11 attributes, partial profile designs simplify choices, reduce the tendency to base decisions on a single attribute, and improve prediction (Chrzan, Citation2010). Next, we generated 999 unique sets of choice tasks (Johnson et al., Citation2013) and randomly one assigned to each student. In addition to 13 experimental choice tasks, each participant completed two hold-out tasks, which were used to estimate internal validity (see Supplementary Table 1).

TABLE 1 Demographic Characteristics of Students in Classes 1–6

TABLE 2 Utility Coefficients and Z Values Presented by Attribute and Latent Class

Additional Measures

Demographic questions

To describe the students in different latent classes, participants indicated their grade and whether they were a boy, girl, or preferred not to answer.

Involvement in bullying

To address RQ4, this scale’s 12 Likert questions, with responses from 1 (not at all) to 5 (many times a week), asked students to report involvement in physical, verbal, social-relational, or cyber bullying as a witness (four items; α = 0.72), perpetrator (four items; α = 0.77), or target (four items; α = 0.74). Those perpetrating, experiencing, or witnessing bullying every month or more were designated “involved.”

Dispositional reactance

To address RQ5, students responded from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to the four-item Hong Reactance Scale for children (e.g., When I am told not to do something I want to do it even more). Internal consistency was 0.70 in a previous study (Miller et al., Citation2006) and 0.69 here. Scores are item totals.

Self-psychological reactance

To address RQ5, students completed seven questions (α = 0.85) indicating how frequently, from 1 (not at all) to 5 (many times a week), they engaged in reactance behavior (e.g., Discouraged other students from joining in AB activities). Scores are item totals.

Peer-psychological reactance

To address RQ5, seven questions (α = 0.89) asked participants how frequently, from 1 (not at all) to 5 (many times a week), they have observed other students engaging in reactance behavior (e.g., tease or bully students who report bullying activities). Scores are item totals.

Procedure

The survey was completed in computer labs or classrooms. If students endorsed an electronic assent, the survey defined physical, verbal, social, and cyber bullying ( and ). The software explained tasks and provided feedback on progress. Students practiced two warm-up choice tasks and completed 13 experimental choice tasks, two hold-out tasks, and additional measures. A member of the study team was present to answer questions. Median time to complete the survey was 21.93 min. Participants averaged 25.10 s (SD = 10.61) per choice task.

Data Analysis

Using Latent Gold Choice (version 5.1) we estimated a multilevel latent class model: choices (Level 1) nested within students (Level 2), nested within Level 3’s schools (Vermunt, Citation2008). The probability of student membership in Level 2 latent classes was allowed to vary for Level 3’s classes of schools (Vermunt, Citation2008). At Level 2 (students), we specified discrete random effects models with one to eight classes. To address RQ3 and to improve the estimation, fit, and interpretation of our models (Lanza & Rhoades, Citation2013; Zhou et al., Citation2018), Grade (5, 6, 7, or 8) was entered as a discrete Level 2 covariate (Vermunt, Citation2008). At Level 3 (schools), we specified from one to three latent classes as discrete random effects. To avoid unrepresentative local maxima, each latent class model was replicated 250 times from start points selected according to a semirandom algorithm (Lanza & Rhoades, Citation2013; Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2005). Using effects-coded choice data, this approach integrates conditional logit and latent class algorithms to fit a set of zero-centered utility coefficients maximizing log likelihood (Hauber et al., Citation2016; Vermunt, Citation2008). Students at Level 2, and schools at Level 3, were assigned to a class with the highest posterior probability of membership. We derived Z scores reflecting the probability that utility coefficients within attributes differed from their mean, zero, and importance scores reflecting the proportion of total variation in Level 2 utility coefficients accounted for by each attribute (Vermunt, Citation2008). As a measure of internal validity (Orme, Citation2014) we used utility coefficients from 13 choice tasks to predict responses to the two hold-out tasks (Supplementary Table 1).

Results

Of the 2,033 students completing the survey, 24.0% reported involvement as a target (19.5%) or perpetrator and target (4.5%); 33.0% reported involvement as bystanders who were not targets or perpetrators (). Of those witnessing bullying (88.6%), 57.7% reported telling an adult and 79.1% reported telling a student to stop.

Regarding RQ1: (Are there groups of students whose intervention decisions are influenced by different attributes of AB programs?), Supplementary Table 2 shows that, at Level 2 (students), a six-class model yielded the lowest Bayesian information criterion, included relatively large classes, and captured heterogeneity relevant to program planning. A bootstrap – 2 log-likelihood (−2LL) difference test (Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2005) confirmed that a six-class solution fit the data better than one-, −2LL = 2711.55, p <.001; two-, −2LL = 1278.87, p < .001; three-, −2LL = 716.54, p < .001; four-, −2LL = 413.39, p <.001; or five-class models, −2LL = 185.95, p < .001. Programs that encouraged intervention ranged from Intensive to Minimal Programming. Classes between these extremes were labeled according to the frequency of AB activities (daily = High Frequency, monthly = Moderate Frequency, and twice yearly = Low Frequency) and consequences for perpetrators (1-week suspension = High Consequences, 1-week loss of recess = Moderate Consequences, and teachers just talked to perpetrators = Low Consequence).

Next, we estimated two- and three-class models at Level 3 (schools). Supplementary Table 2 shows that a model with six Level 2 classes, grade as a discrete covariate, and two Level 3 classes (schools) reduced Akaike information criteria (AIC) and AIC3, and was retained (Andrews & Currim, Citation2003). Supplementary Table 3 shows the probability of membership in the two latent classes of schools at Level 3 (53.2% and 46.8%) and the probability of membership in each of the six student-level classes within the two classes of schools. The proportion of participants in each class of students varied within the two clusters of schools with a greater proportion of Minimal Programming students in school Class 2 (15.8%) than in school Class 1 (7.1%).

TABLE 3 Relative Importance Scores Presented by Latent Class and Attribute

RQ2 (Which attributes of AB programs influence the decision to intervene?) and RQ3 (Is the decision to intervene linked to grade?) are considered together next. lists zero-centered utility coefficients from the final model. We begin with attributes that most latent classes agreed would motivate intervention. Five classes (89.6% of participants) thought students would intervene when peers almost always reported bullying and schools responded immediately. Four classes (76.4%) thought students would intervene in schools where students always included those who were left out. Next, we consider attributes eliciting a differential response and examine grade as a covariate of class membership.

Intensive Programming (High-Frequency High Consequence)

This class (28.7%) thought that students would intervene in schools with daily AB activities, eight teachers watching playgrounds, mandatory reporting, rewards for preventing bullying, and 1-week suspensions for perpetrators (). They preferred interesting programming teaching students how to stop bullying. Variation in the inclusion of left-out students exerted more influence on this class’s choices than any other attribute (). Membership in the Intensive Programming class was not linked to grade.

High-Frequency Moderate Consequences

This class (13.0%) thought that students would intervene in schools with daily AB activities, four teachers watching playgrounds, mandatory reporting, and a 1-week loss of recess for perpetrators. Variation in consequences for perpetrators exerted more influence on the decision to intervene than any other attribute (). This class was more likely to be in Grade 5, γ = 0.37, SE = 0.14, Z = 2.63, and less likely to be in Grade 8, γ = −0.50, SE = 0.18, Z = −2.72.

Moderate-Frequency High Consequences

This class (15.2%) thought that students would intervene in schools with monthly AB activities, four teachers watching playgrounds, mandatory reporting, rewards for preventing bullying, and 1-week suspensions for perpetrators. Variation in consequences for perpetrators exerted more influence on this class’s choices than any other attribute (). They were less likely to be in Grade 5, γ = −0.38, SE = 0.15, Z = −2.53, and more likely to be in Grade 8, γ = 0.47, SE = 0.13, Z = 3.71.

Moderate-Frequency Moderate Consequences

This class (23.4%) thought that students would intervene in schools with monthly AB activities, four teachers watching playgrounds, a policy asking students to report bullying, rewards for students preventing bullying, and a 1-week loss of recess for perpetrators. Their choices were sensitive to the inclusion of left-out peers and the likelihood that students would report bullying (). Membership in this class was not associated with grade.

Moderate-Frequency Low Consequences

This class (9.3%) thought that students would intervene with monthly AB activities, four teachers watching playgrounds, voluntary reporting, and teachers who just talked to perpetrators. Variation in consequences for perpetrators exerted more influence on their choices than any other attribute (). This class was more likely to be in Grade 5, γ = 0.61, SE = 0.14, Z = 4.33, and less likely to be in Grade 8, γ = −0.56, SE = 0.20, Z = - 2.84 ().

Minimal Programming (Moderate- to Low-Frequency Low Consequence)

This class (10.3%) thought that students would intervene in schools with monthly or twice-yearly AB activities, two teachers watching playgrounds, and teachers who talked to perpetrators. They thought that students would intervene when asked to report bullying. They were especially sensitive to the frequency of AB activities, mandatory versus discretionary reporting, and the number of teachers watching playgrounds (). They were more likely to be in Grade 8, γ = 0.38, SE = 0.14, Z = 2.72, and less likely to be in Grade 5, γ = −0.42, SE = 0.17, Z = −2.43.

Regarding RQ4 (Is bullying involvement linked to latent class membership?), the Minimal Programming class reported more involvement as perpetrators, victims, and witnesses than the Intensive Programming and the Moderate-Frequency, Moderate Consequence classes. They reported greater involvement as witnesses than the High-Frequency, Moderate Consequence and the Moderate-Frequency, Low Consequence classes. Complete post hoc comparisons are presented in .

TABLE 4 Involvement in Bullying, Reactance Behavior, and Dispositional Reactance Means and Standard Deviations

Regarding RQ5 (Is psychological reactance linked to latent class membership?), the Minimal Programming class reported more Self-Psychological Reactance than all other classes. They reported higher Dispositional Reactance than the Intensive Programming class, the Moderate-Frequency Moderate Consequence class, and the Moderate-Frequency Moderate Consequence classes. The classes did not report differences in Peer-Psychological Reactance. Post hoc comparisons are presented in .

Discussion

Students are often hesitant to speak up or report bullying incidents. This study makes four contributions to our understanding of factors influencing the decision to intervene. First, experimentally manipulating the attributes of hypothetical AB programs builds on investigations studying the cognitive and attitudinal factors associated with student intervention (Gini et al., Citation2008; Pozzoli & Gini, Citation2010; Pozzoli et al., Citation2012; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013; Thornberg et al., Citation2017). Second, latent class analysis points to variation in the impact of different AB program designs on student intervention; attributes that increase intervention by some classes may reduce intervention by others. Third, this study links measures of psychological reactance and dispositional reactance, thought to reduce the effectiveness of AB programs for older students (Yeager et al., Citation2015), to the response of students to hypothetical AB initiatives. Finally, the multilevel finding that classes of students evidencing greater dispositional reactance, psychological reactance, and involvement as perpetrators are twice as likely to be in one group of schools has implications for community-wide implementation.

Multilevel analysis revealed six latent classes with differing perspectives regarding the components of AB programs influencing student intervention. The Intensive Programming class (28.7% of the sample) thought that students would be most likely to intervene in schools with daily AB activities, increased supervision, mandatory reporting, an immediate response to student reports of bullying, and significant consequences for those involved as perpetrators. The Minimal Programming class (10.3%), in contrast, thought students would intervene in schools with less frequent AB activities, fewer playground supervisors, voluntary reporting, and teachers who just talked to perpetrators. As predicted, this class was more likely to be in Grade 8 and reported higher dispositional reactance, more psychological reactance, and greater involvement as perpetrators. The designs influencing the choices of the remaining classes were distributed between the Intensive and Minimal Programming classes. The pattern of attributes influencing the intent to intervene is consistent with studies yielding segments of students with a more general preference for high-, moderate-, and low-intensity programs (Cunningham et al., Citation2011).

AB Program Design Implications

Next we discuss the implications of our findings and, using examples from a selection of AB programs that have reduced bullying, illustrate the types of programming features that influenced student decisions in the current study.

Create a supportive school climate

Consistent with a social ecological model (J. S. Hong & Espelage, Citation2012), most participants thought that students would intervene in schools where students included isolated peers, individuals who may be particularly vulnerable to bullying. The KiVa AB program, for example, ensures that several socially competent classmates support targeted students (Karna et al., Citation2011). Students are more likely to intervene when classroom relationships between students are stronger (Thornberg et al., Citation2017). Students who feel connected to their schools (Sulkowski et al., Citation2014), or consider their schools to be more supportive (Eliot et al., Citation2010), are more likely to seek help from adults.

Increase awareness of intervention by peers

Reporting by peers exerted a strong influence on the decision to intervene. This is consistent with studies finding a positive relation between perceived peer pressure to intervene and efforts to defend targets (Pozzoli & Gini, Citation2010; Pozzoli et al., Citation2012), and with evidence that school-level norms predict peer nominations regarding student intervention (Barhight et al., Citation2017). Without information regarding the response of their peers, bystanders may assume that other students do not support intervention (Salmivalli, Citation2014). Increases in the perception that students in the KiVa AB program defended peers mediated reductions in self-reported involvement as a perpetrator (Saarento et al., Citation2015). Future studies might explore the relative effectiveness of different ways of acknowledging bystander intervention while maintaining the anonymity students valued.

Respond promptly

The time between reporting and response by teachers exerted an important influence on student choices; most thought that students would be more likely to intervene if schools responded immediately. In addition to reducing the risk of escalation, students may interpret prompt responses as an indicator of the extent to which teachers disapprove of bullying, a factor mediating the KiVa AB program school-level effects on peer and self-reports of bullying (Saarento et al., Citation2015). To ensure a prompt and effective response, the KiVa AB program trains teams of teachers to respond according to a consistent protocol when bullying is observed or reported (Karna et al., Citation2011).

Ensure an effective response when bullying is reported

Variation in the school’s response to bullying exerted an important influence on student choices. Students often question the effectiveness of the consequences that schools employ when responding to perpetrators (Bradshaw & Sawyer, Citation2007; Cunningham et al., Citation2011; Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016). Students rate the enforcement of rules regarding conduct to be an important school safety strategy (Booren & Handy, Citation2009). Systematic reviews conclude that consequences are associated with an incremental increase in the effectiveness of AB programs (Ttofi & Farrington, Citation2011). Bullying is less frequent in schools combining fair and consistently enforced rules with caring and respectful student–teacher interactions (Gregory et al., Citation2010). Despite this attribute’s importance, students disagreed regarding the consequences that would encourage intervention: 19.6% were in a Minimal Programming class that thought talks between perpetrators and teachers would encourage intervention, 36.4% advocated a 1-week loss of recess, and 43.9% thought that students would intervene when perpetrators were suspended for 1 week. Focus groups also disagreed with each other regarding the impact of suspensions and loss of recess (Cunningham et al., Citation2011; Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016), concerns consistent with those of teachers (Cunningham, Rimas et al., Citation2016) and policy reviews (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Citation2016).

Optimize the frequency of AB activities

Longitudinal analyses link the dosage of the KiVa AB program to greater peer-reported willingness to help victims, a refusal to reinforce bullying, and efforts to stop perpetrators (Swift et al., Citation2017). The current study suggests potential trade-offs in programming frequency. The High-Intensity and High-Frequency Moderate Consequence classes (41.7% of the study’s participants) thought that students would be more likely to intervene when schools conducted daily AB activities. The remainder thought monthly programming would motivate intervention. This finding is consistent with qualitative studies: Some students advocated more frequent programming, whereas others thought that repetitive activities lost their effectiveness and generated pushback (Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016).

Teach prevention and empathy

Most (66.2%) participants were in latent classes who thought that students would intervene in schools teaching the skills to prevent bullying. Most (77.6%) were also in classes who thought that students would intervene when AB programming helped students understand the impact of bullying on targets. The No Trap program, for example, uses peer educators to teach skills for coping with bullying while focusing on empathy and the feelings of bystanders and targets of bullying (Palladino, Nocentini, & Menesini, Citation2016). This approach is consistent with evidence that confidence in one’s ability to intervene is linked to increased peer intervention (Pronk et al., Citation2013; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013; Thornberg et al., Citation2017). Higher empathy and moral engagement are also associated with increased student intervention (Gini et al., Citation2008; Pronk et al., Citation2013; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013; Thornberg et al., Citation2017). Students are more likely to nominate peers reporting higher empathy as a classmate who “gets an adult to help” (Barhight et al., Citation2017). In addition to their contribution to the decision to intervene, prevention messages inducing empathy could reduce the reactance reported by the Minimal Programming class (Shen, Citation2010), a question meriting further research.

Motivate discretionary reporting

Almost half of this study’s participants were in classes who thought that students would be more likely to intervene if they were asked rather than required to report bullying. Psychological reactance theory predicts that strong persuasive messages may elicit an effort to reassert personal control that could undermine prevention programming (Rosenberg & Siegel, Citation2017). Reporting policies exerted an important influence on the choices of the Minimal Programming class, older students reporting greater dispositional reactance, reactance behavior, and involvement as perpetrators. Reactance, which appears to increase during early adolescence (Grandpre et al., Citation2003), is thought to have reduced the effectiveness of AB programs during this age range (Yeager et al., Citation2015) and limited the impact of other prevention initiatives (Bushman, Citation2006; Legault et al., Citation2011; Wiium et al., Citation2009).

Optimize supervision

The Intensive Programming class thought that students would be more likely to intervene when eight teachers watched playgrounds. Although increased supervision is supported by systematic reviews (Ttofi & Farrington, Citation2011) and is a component of the Olweus AB program (Olweus, Citation1994), most participants (60.9%) were in classes that thought that student intervention would increase with fewer supervisors present. Increasing supervision may limit the sense of responsibility that prompts student intervention (Fischer et al., Citation2011). The effect of increased supervision may also be limited if teachers are hesitant to respond when colleagues are present, supervisors distract one another (Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016), or teachers complicate problems (Bradshaw & Sawyer, Citation2007; Cunningham et al., Citation2011; Cunningham, Mapp et al., Citation2016). Future studies might focus on the link between implementation training for playground supervisors, their adherence to intervention protocols, and the willingness of students to intervene.

Plan for heterogeneity in implementation outcomes

The size of the six student-level classes varied across Level 3’s two classes of schools. A greater proportion of the students in Class 2 were in the Minimal Programming class. These students reported higher dispositional reactance, more reactance to AB programs, and more involvement as perpetrators. Although the Minimal Programming class represents a small percentage of students (10.3%), they may—via social contagion, status as eighth graders, and concentration in some schools—exert a disproportionate influence on the response of their peers (Dishion & Tipsord, Citation2011). Indeed, deviancy training (Helseth et al., Citation2015) was a component of our psychological reactance measures (e.g., discouraging peers from participating in AB activities). The distribution of this class may contribute to variation in program outcome, the need for local adjustments, and additional implementation support.

Limitations

We recruited participants from an ethnically and economically diverse Canadian community. Although results are generalizable to Grade 5–8 students in this context, the applicability of these findings to other settings is unclear. Second, we studied the views of students regarding factors influencing the decision to intervene. To ensure successful implementation, AB programs should also consider the views of educators who conduct AB programs (Cunningham, Rimas et al., Citation2016), and the parents whose relationships with their children may influence the outcome of these initiatives (Kaufman, Kretschmer, Huitsing, & Veenstra, Citation2018). Third, the number of attributes that can be included in DCEs is limited. The decision to intervene could be influenced by attributes, such as volunteer peer educators (Palladino et al., Citation2016), classroom rules (Olweus, Citation1994), or systematic support for students who are targets of bullying (Karna et al., Citation2011), which were not included in our models. Finally, program design should be informed by attributes of the broader school climate, which could influence the outcome of AB programs and the course of targeted students (Gage, Prykanowski, & Larson, Citation2014).

Conclusion

Developers need to identify attributes of AB programs likely to have the greatest impact on specific outcome objectives—in this case, intervening by reporting bullying or seeking help from an adult. Contextually and relationally focused programs in which students include isolated peers, peers intervene, and teachers respond quickly would optimize the intent to intervene. Latent class analysis points to design trade-offs—programs encouraging intervention by students with little involvement, as perpetrators might discourage reporting by students with higher dispositional reactance, more reactance, and greater involvement as perpetrators.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.8 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the support of the students, teachers, and administrators who made this project possible. Stephanie Mielko and Yvonne Chen provided valuable research support. Dr. Jay Magidson from Statistical Innovations provided statistical consultation supporting data analyses. Thipiga Sivayoganathan provided editorial contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

References

- T Andrews, R. L., & Currim, I. S. (2003). A comparison of segment retention criteria for finite mixture logit models. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(2), 235–243. doi:10.1509/jmkr.40.2.235.19225

- Barhight, L. R., Hubbard, J. A., Grassetti, S. N., & Morrow, M. T. (2017). Relations between actual group norms, perceived peer behavior, and bystander children’s intervention to bullying. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 394–400. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1046180

- Batanova, M., Espelage, D. L., & Rao, M. A. (2014). Early adolescents’ willingness to intervene: What roles do attributions, affect, coping, and self-reported victimization play? Journal of School Psychology, 52(3), 279–293. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2014.02.001

- Booren, L. M., & Handy, D. J. (2009). Students’ perceptions of the importance of school safety strategies: An introduction to the IPSS survey. Journal of School Violence, 8(3), 233–250. doi:10.1080/15388220902910672

- Bradshaw, C. P., & Sawyer, A. L. (2007). Bullying and peer victimization at school: Perceptual differences between students and school staff. School Psychology Review, 36(3), 361–383.

- Bushman, B. J. (2006). Effects of warning and information labels on attraction to television violence in viewers of different ages. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(9), 2073–2078. doi:10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00094.x

- Caruso, E. M., Rahnev, D. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2009). Using conjoint analysis to detect discrimination: Revealing covert preferences from overt choices. Social Cognition, 27(1), 128–137. doi:10.1521/soco.2009.27.1.128

- Chrzan, K. (2010). Using partial profile choice experiments to handle large numbers of attributes. International Journal of Market Research, 52(6), 827–840. doi:10.2501/S1470785310201673

- Cortes, K. I., & Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2014). To tell or not to tell: What influences children’s decisions to report bullying to their teachers? School Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 336–348. doi:10.1037/spq0000078

- Craig, W., Pepler, D. J., & Atlas, R. (2000). Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International, 21(1), 22–36. doi:10.1177/0143034300211002

- Crothers, L. M., & Kolbert, J. B. (2004). Comparing middle school teachers’ and students’ views on bullying and anti-bullying interventions. Journal of School Violence, 3(1), 17–32. doi:10.1300/J202v03n01_03

- Cunningham, C. E., Cunningham, L. J., Ratcliffe, J., & Vaillancourt, T. (2010). A qualitative analysis of the bullying prevention and intervention recommendations of students in grades 5 to 8. Journal of School Violence, 9(4), 321–338. doi:10.1080/15388220.2010.507146

- Cunningham, C. E., Mapp, C., Rimas, H., Cunningham, L. J., Mielko, S., Vaillancourt, T., & Marcus, M. (2016). What limits the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs? A thematic analysis of the perspective of students. Psychology of Violence, 6(4), 596–606. doi:10.1037/a0039984

- Cunningham, C. E., Rimas, H., Mielko, S., Mapp, C., Cunningham, L., Buchanan, D., … Marcus, M. (2016). What limits the effectiveness of antibullying programs? A thematic analysis of the perspective of teachers. Journal of School Violence, 15(4), 460–482. doi:10.1080/15388220.2015.1095100

- Cunningham, C. E., Vaillancourt, T., Cunningham, L. J., Chen, Y., & Ratcliffe, J. (2011). Modeling the bullying prevention program design recommendations of students from grades 5 to 8: A discrete choice conjoint experiment. Aggressive Behavior, 37(6), 521–537. doi:10.1002/ab.20408

- de Bekker-Grob, E. W., Ryan, M., & Gerard, K. (2012). Discrete choice experiments in health economics: A review of the literature. Health Economics, 21(2), 145–172. doi:10.1002/hec.1697

- DeLara, E. W. (2012). Why adolescents don’t disclose incidents of bullying and harassment. Journal of School Violence, 11(4), 288–305. doi:10.1080/15388220.2012.705931

- DeLuca, P. F., Johnston, N., & Buist, S. (2012). The code red project: Engaging communities in health system change in Hamilton, Canada. Social Indicators Research, 108(2), 317–327. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0068-y

- Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412

- Eliot, M., Cornell, D., Gregory, A., & Fan, X. (2010). Supportive school climate and student willingness to seek help for bullying and threats of violence. Journal of School Psychology, 48(6), 533–553. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2010.07.001

- Evans, C. B., Fraser, M. W., & Cotter, K. L. (2014). The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(5), 532–544. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004

- Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., … Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 517–537. doi:10.1037/a0023304

- Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 303–315. doi:10.1086/209351

- Fontaine, R. G., & Dodge, K. A. (2006). Real-time decision making and aggressive behavior in youth: A heuristic model of response evaluation and decision (RED). Aggressive Behavior, 32(6), 604–624. doi:10.1002/ab.20150

- Gage, N. A., Prykanowski, D. A., & Larson, A. (2014). School climate and bullying victimization: A latent class growth model analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 256–271. doi:10.1037/spq0000064

- Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoe, G. (2008). Determinants of adolescents’ active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 31(1), 93–105. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.002

- Grandpre, J., Alvaro, E. M., Burgoon, M., Miller, C. H., & Hall, J. R. (2003). Adolescent reactance and anti-smoking campaigns: A theoretical approach. Health Communication, 15(3), 349–366. doi:10.1207/S15327027HC1503_6

- Gregory, A., Cornell, D., Fan, X., Sheras, P., Shih, T. H., & Huang, F. (2010). Authoritative school discipline: High school practices associated with lower bullying and victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 483–496. doi:10.1037/a0018562

- Hauber, B., Gonzalez, J., Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C., Prior, T., Marshall, D., Cunningham, C., … Bridges, J. (2016). Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete-choice experiments: A report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices task force. Value in Health, 19(4), 300–315. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.004

- Hawkins, D. L., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10(4), 512–527. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00178

- Helseth, S. A., Waschbusch, D. A., Gnagy, E. M., Onyango, A. N., Burrows-MacLean, L., Fabiano, G. A., … Walker, K. S. (2015). Effects of behavioral and pharmacological therapies on peer reinforcement of deviancy in children with ADHD-only, ADHD and conduct problems, and controls. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(2), 280. doi:10.1037/a0038505

- Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

- Hong, S. M., & Page, S. (1989). A psychological reactance scale: Development, factor structure and reliability. Psychological Reports, 64(3c), 1323–1326. doi:10.2466/pr0.1989.64.3c.1323

- Johnson, R. F., Lancsar, E., Marshall, D., Kilambi, V., Muhlbacher, A., Regier, D. A., … Bridges, J. F. (2013). Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: Report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value in Health, 16(1), 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223

- Karna, A., Voeten, M., Little, T. D., Poskiparta, E., Kaljonen, A., & Salmivalli, C. (2011). A large-scale evaluation of the KiVa antibullying program: Grades 4-6. Child Development, 82(1), 311–330. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01557.x

- Kaufman, T. M. L., Kretschmer, T., Huitsing, G., & Veenstra, R. (2018). Why does a universal anti-bullying program not help all children? Explaining persistent victimization during an intervention. Prevention Science, 19(6), 822–832. doi:10.1007/s11121-018-0906-5

- Langford, R., Bonell, C., Jones, H., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S., Waters, E., … Campbell, R. (2015). The world health organization’s health promoting schools framework: A cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15, 130. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y

- Lanza, S. T., & Rhoades, B. L. (2013). Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science, 14(2), 157–168. doi:10.1007/s11121-011-0201-1

- Legault, L., Gutsell, J., & Inzlicht, M. (2011). Ironic effects of anti-prejudice messages: How motivational interventions can reduce (but also increase) prejudice. Psychological Science, 22(12), 1472–1477. doi:10.1177/0956797611427918

- McDougall, P., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. The American Psychologist, 70(4), 300–310. doi:10.1037/a0039174

- Miller, C. H., Burgoon, M., Grandpre, J. R., & Alvaro, E. M. (2006). Identifying principal risk factors for the initiation of adolescent smoking behaviors: The significance of psychological reactance. Health Communication, 19(3), 241–252. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1903_6

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Preventing bullying through science, policy, and practice. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Nocentini, A., Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Level and change of bullying behavior during high school: A multilevel growth curve analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 495–505. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.004

- Novick, R. M., & Isaacs, J. (2010). Telling is compelling: The impact of student reports of bullying on teacher intervention. Educational Psychology, 30(3), 283–296. doi:10.1080/01443410903573123

- O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4), 437–452. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0238

- Oliver, C., & Candappa, M. (2007). Bullying and the politics of ‘telling’. Oxford Review of Education, 33(1), 71–86. doi:10.1080/03054980601094594

- Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(7), 1171–1190. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01229.x

- Orme, B. K. (2014). Getting started with conjoint analysis: Strategies for product design and pricing research (4th ed.). Madison, WI: Research Publishers.

- Palladino, B. E., Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2016). Evidence‐based intervention against bullying and cyberbullying: Evaluation of the NoTrap! program in two independent trials. Aggressive Behavior, 42(2), 194–206. doi:10.1002/ab.21636

- Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. Retrieved from http://naspjournals.org/loi/spsr?code=naps-site

- Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2010). Active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: The role of personal characteristics and perceived peer pressure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 815–827. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9

- Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Vieno, A. (2012). The role of individual correlates and class norms in defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: A multilevel analysis. Child Development, 83(6), 1917–1931. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01831.x

- Pronk, J., Goossens, F. A., Olthof, T., De Mey, L., & Willemen, A. M. (2013). Children’s intervention strategies in situations of victimization by bullying: Social cognitions of outsiders versus defenders. Journal of School Psychology, 51(6), 669–682. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2013.09.002

- Rosenberg, B. D., & Siegel, J. T. (2017). A 50-year review of psychological reactance theory: Do not read this article. Motivation Science. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/mot0000091

- Saarento, S., Boulton, A. J., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Reducing bullying and victimization: Student- and classroom-level mechanisms of change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(1), 61–76. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9841-x

- Sainio, M., Veenstra, R., Huitsing, G., & Salmivalli, C. (2011). Victims and their defenders: A dyadic approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 144–151. doi:10.1177/0165025410378068

- Salmivalli, C. (2014). Participant roles in bullying: How can peer bystanders be utilized in interventions? Theory into Practice, 53(4), 286–292. doi:10.1080/00405841.2014.947222

- Salmivalli, C., Karhunen, J., & Lagerspetz, K. M. J. (1996). How do the victims respond to bullying? Aggressive Behavior, 22(2), 99–109. doi:10.1002/(SICI)10982337(1996)22:2<99::AID-AB3>3.0.CO;2-P

- Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(5), 668–676. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.597090

- Sawtooth Software. (2013). The CBC system for choice-based conjoint analysis version 8. (Technical). Orem, Utah: Author. Retrieved from http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/download/techpap/cbctech.pdf

- Shen, L. (2010). Mitigating psychological reactance: The role of message-induced empathy in persuasion. Human Communication Research, 36(3), 397–422. doi:10.111/j.1468-2958.2010.01381.x

- Sulkowski, M. L., Bauman, S. A., Dinner, S., Nixon, C., & Davis, S. (2014). An investigation into how students respond to being victimized by peer aggression. Journal of School Violence, 13(4), 339–358. doi:10.1080/15388220.2013.857344

- Swift, L. E., Hubbard, J. A., Bookhout, M. K., Grassetti, S. N., Smith, M. A., & Morrow, M. T. (2017). Teacher factors contributing to dosage of the KiVa anti-bullying program. Journal of School Psychology, 65, 102–115. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2017.07.005

- Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 475–483. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2017). Classroom relationship qualities and social-cognitive correlates of defending and passive bystanding in school bullying in sweden: A multilevel analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 49–62. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.002

- Trach, J., Hymel, S., Waterhouse, T., & Neale, K. (2010). Bystander responses to school bullying: A cross-sectional investigation of grade and sex differences. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25(1), 114–130. doi:10.1177/0829573509357553

- Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27–56. doi:10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

- Unnever, J. D., & Cornell, D. G. (2004). Middle school victims of bullying: Who reports being bullied? Aggressive Behavior, 30(5), 373–388. doi:10.1002/ab.20030

- Vermunt, J. K. (2008). Latent class and finite mixture models for multilevel data sets. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 17(1), 33–51. doi:10.1177/0962280207081238

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2005). Technical guide for latent GOLD 4.0: Basic and advanced. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations Inc.

- Wiium, N., Aarø, L. E., & Hetland, J. (2009). Psychological reactance and adolescents’ attitudes toward tobacco-control measures. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(7), 1718–1738. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00501.x

- Williams, F., & Cornell, D. G. (2006). Student willingness to seek help for threats of violence in middle school. Journal of School Violence, 5(4), 35–49. doi:10.1300/J202v05n04_04

- Yeager, D. S., Fong, C. J., Lee, H. Y., & Espelage, D. (2015). Declines in efficacy of anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: A developmental theory and a three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 36–51. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.005

- Zhou, M., Thayer, W. M., & Bridges, J. F. P. (2018). Using latent class analysis to model preference heterogeneity in health: A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics, 36(2), 175–187. doi:10.1007/s40273-017-0575-4