Abstract

Multiple psychosocial interventions are efficacious for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) including behavioral parent training, behavioral classroom management, behavioral peer interventions, and organization training programs. Unfortunately, there is a significant gap between research and practice such that evidence-based treatments often are not implemented in community and school settings. Using a life course model for ADHD treatment implementation, we discuss future research directions that support movement from the current, fragmented system of care to a more comprehensive, integrated, and multisystemic approach. Specifically, we offer six recommendations for future research. Within the realm of treatment development and evaluation, we recommend (1) identifying and leveraging mechanisms of change, (2) examining impact of youth development on treatment mechanisms and outcomes, and (3) designing intervention research in the context of a life course model. Within the realm of implementation and dissemination, we recommend investigating strategies to (4) enhance access to evidence-based treatment, (5) optimize implementation fidelity, and (6) examine and optimize costs and cost-effectiveness of psychosocial interventions. Our field needs to go beyond short-term, efficacy trials to reduce symptomatic behaviors conducted under ideal controlled conditions and successfully address the research-to-practice gap by advancing development, evaluation, implementation, and dissemination of evidence-based treatment strategies to ameliorate ADHD-related impairment that can be used with fidelity by parents, teachers, and community health providers.

Children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) experience significant deficits in academic and/or social functioning that typically begin early in life and extend into emerging adulthood and beyond (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; DuPaul & Langberg, Citation2015). Symptomatic behaviors of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity disrupt development of self-regulation skills; negatively impact academic performance and achievement; are associated with higher than average risk for special education eligibility, grade retention, and school-dropout; and lead to problematic relationships with peers and authority figures (e.g., parents, teachers) (Barkley, Murphy, & Fischer, Citation2008; Frazier, Youngstrom, Glutting, & Watkins, Citation2007; Hechtman, Citation2017; Mikami, Citation2010; Normand et al., Citation2013). Given the relatively high prevalence rate of 8 to 11% for ADHD (Danielson et al., Citation2018), this disorder is very costly in terms of health care and educational expenditures (Chorozoglou et al., Citation2015; Robb et al., Citation2011). Thus, it is critically important that effective interventions are implemented across home, school, and community settings to not only reduce ADHD symptoms but also attenuate potentially chronic functional impairments.

Multiple psychopharmacological and psychosocial interventions have been established as effective for treatment of ADHD symptoms and associated impairments. Psychopharmacological regimens primarily include central nervous stimulants such as methylphenidate, but also non-stimulant drugs (e.g., atomoxetine) (Conner, Citation2015). In similar fashion, psychosocial treatments including behavioral parent training, behavioral classroom management, behavioral peer interventions, organization training programs, and, to a lesser extent, academic interventions are effective and associated with medium to large effects on ADHD symptoms and related functional impairments (DuPaul, Eckert, & Vilardo, Citation2012; Evans, Owens, Wymbs, & Ray, Citation2018; Fabiano, Pelham et al., Citation2009).

For many years, the foundation of psychosocial treatment for youth with ADHD has been behavioral treatment (Pelham & Fabiano, Citation2008). Clinicians trained parents or teachers how to manipulate contingencies in the home or school setting to increase the likelihood of children with ADHD following rules, staying on task, and being productive. Although techniques taught to parents and teachers took many forms (e.g., daily report card, token economy, time out from positive reinforcement), the mechanism of action for most of these was to manipulate the way that punishment and reinforcement were provided, make the contingencies consistent and clear to the child, and track the child’s’ responses. Much of the recent research on behavioral approaches have been focused on helping adults learn these techniques and effectively implement them over time (e.g., Chacko et al., Citation2008; Fabiano, Chacko et al., Citation2009; Owens et al., Citation2017).

During the last decade, psychosocial treatments for ADHD have gone beyond behavioral approaches (see Evans, Owens, & Power, Citation2019; Evans et al., Citation2018). The expansion in approaches has been driven to a large extent by a focus on developing effective psychosocial treatments for adolescents, including training interventions (Evans et al., Citation2016; Langberg, Epstein, Becker, Girio-Herrera, & Vaughn, Citation2012), motivational interviewing techniques (Sibley et al., Citation2016), and cognitive approaches (Boyer, Geurts, Prins, & Van Der Oord, Citation2015; Sprich, Safren, Finkelstein, Remmert, & Hammerness, Citation2016; Vidal et al., Citation2015). In addition, family therapy approaches that were identified as relatively ineffective by Barkley and colleagues (Barkley, Edwards, Laneri, Fletcher, & Metevia, Citation2001), have been revisited and enhanced for adolescents with ADHD with some promise (Fabiano et al., Citation2016; Sibley et al., 2016).

Unfortunately, there is a significant gap between research and practice such that evidence-based treatment strategies often are not implemented in community and school settings. For example, only about 31% of families of children with ADHD have received behavioral parent training compared to 91% having ever received psychotropic medication (Danielson, Visser, Chronis-Tuscano, & DuPaul, Citation2018). A recent Office of Inspector General report indicated that 45% of Medicaid-enrolled children with ADHD who were newly medicated did not receive behavior therapy as part of their treatment (US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2019). In addition, only about 32% of students with ADHD are reported to receive classroom behavior management (DuPaul, Chronis-Tuscano, Danielson, & Visser, Citation2019). The underutilization of evidence-based psychosocial treatment for children with ADHD is likely due, in part, to the limited training that education, health, and mental health professionals receive in evidence-based practices, the scant availability of and access to services, as well as challenges related to delivery of treatment across systems (e.g., home, school, healthcare).

The purpose of this article is to identify future research directions that would support movement from the current, oft-fragmented, and inconsistently implemented system of care to a more integrated, multisystemic, longitudinal approach. We first briefly describe a life course model for ADHD treatment implementation across family, school, and health care systems. This model provides a context for prioritizing research initiatives. Next, we present a hypothetical case of a young child with ADHD to describe treatment strategies typically implemented across settings and the child’s development. We use this case to illustrate limitations of treatment content and procedures over time in the context of current knowledge. Finally, we make specific recommendations for research that address these limitations.

Life Course Model for Treatment of ADHD

We previously proposed a model for treatment of ADHD that emphasizes a life-course perspective to address the long-term implications and outcomes of early life experiences on health, psychological, and educational outcomes of individuals with ADHD across the life span (Evans, Owens, Mautone, DuPaul, & Power, Citation2014). In contrast to prevailing models of care that focus on service delivery to individuals emphasizing short-term symptom reduction, the life-course model prioritizes helping youth with ADHD improve competencies and develop into independent, healthy adults who achieve occupational, personal, and recreational success. Briefly, this model is comprised of four layers of services including (1) foundational strategies to establish appropriate structure and supports in home and school (e.g., parent-teacher communication), (2) psychosocial interventions to increase competencies and address impairments in academic, behavioral, and social functioning (e.g., organization interventions), (3) medication treatment, and (4) accommodations to adapt environments to children’s limitations (i.e., reductions in expectations). These layers represent the sequence within which services should be delivered and combined over time and across systems and settings. The life course model includes seven principles for service delivery including the need to: (a) understand contextual and cultural factors, (b) promote treatment engagement of parents and youth, (c) tailor interventions to child’s developmental level, (d) design interventions to meet individual child and family needs, (e) facilitate alliances within and between systems, (f) offer implementation supports for intervention providers, and (g) conduct progress monitoring to evaluate treatment response. The hypothetical case below describes common barriers faced by families as they attempt to receive treatment for ADHD across their child’s development, highlighting the need for a life course approach to care and closures in the research-to-practice gap.

The Case of “James”

James is a boy who lives with his biological parents and two siblings (9-year-old brother, 2-year-old sister) in a small urban community in the northeastern US. Since toddlerhood, James displayed significant inattention and hyperactive-impulsive behaviors across home and school settings such that he was expelled from two different preschools due to his disruptive activity. Based on this history, when James was four, his primary care provider diagnosed James with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and suggested that James start a low-dose of a psychostimulant medication. Because his mother knew her neighbor had a bad experience with this type of medication, she declined to fill the prescription.

James experienced significant academic (low report card grades, inconsistent work completion) and behavioral (e.g., inattention to instructions, disruptive verbal and physical actions) difficulties as he entered and progressed through elementary school. He also experienced a great deal of difficulty making and keeping friends. His teachers attempted a variety of interventions including token reinforcement programs and daily behavior report card systems; however, none of these were implemented in a sustained fashion with consistency across school years, and James’s parents were not routinely included in plan development. James began receiving psychostimulant medication from his primary care provider when he was in second grade with treatment continuing in various formulations and dosages throughout his school years. Although medication reduced his ADHD symptoms to a significant degree, he continued to experience considerable academic and social impairment. In addition, his parents were reluctant to let school personnel know about James’s medication treatment, i.e., there was a significant disconnect between home and school systems of care for James.

In middle and high school, James exhibited increasing difficulties with organization, and study and time management skills. With school personnel assistance, James’s parents intermittently implemented homework management programs (i.e., inconsistent treatment fidelity). School counselors also met with James periodically to help him with his study skills and time management. By high school, James started to develop symptoms of depression (negative self-cognitions, withdrawal from social activities). Despite these various treatment efforts over the years, he experienced consistent difficulties with school grades, building and maintaining friendships, and developing recreational interests beyond social media and video games. Stated differently, although the combination of psychosocial treatment strategies and medication led to periodic improvements in James’s ADHD symptoms and related impairments, these were never sustained over time nor was his functioning normalized (i.e., commensurate with academic and social functioning of his peers). Failure to achieve and sustain substantial gains may have been due to several factors including lack of access to evidence-based care (e.g., behavioral parent training), inconsistent treatment implementation fidelity, as well as inherent limitations of extant short-term treatment strategies (e.g., effects unlikely to generalize across settings and over time without direct programming that is cross-situational and sustained). The impact of treatment on James’s development also may have been limited by inconsistent collaboration and communication across home, school, healthcare, and community systems. These are among the many areas that should be prioritized for empirical investigation to enhance outcomes for children like James.

Recommendations for Future Research in Treatment Development and Evaluation

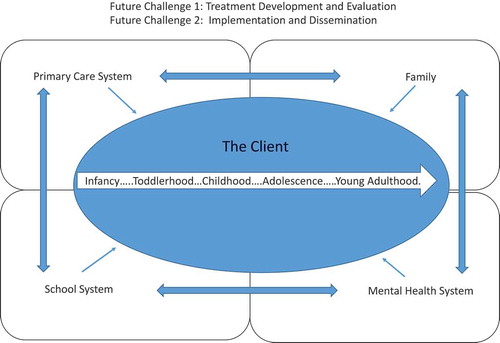

Given the limitations highlighted in the case of James, we offer three recommendations within the realm of treatment development and evaluation and three recommendations within the realm of implementation and dissemination (see below). Collectively, these recommendations directly address challenges to psychosocial treatment of ADHD within and across family, school, primary care, and mental health systems, affirming the child’s long-term development as a priority (see ).

Recommendation 1: Identify and Leverage Mechanisms of Change

In order to adequately address the system of care issues, there needs to be effective treatments and we do not yet have an adequate arsenal to effectively treat children and adolescents with ADHD. The development and evaluation of new treatments is most effective when guided by theory and evidence of mechanisms of change. A variable can be considered a mechanism of change that explains why a treatment works, if the variable is malleable and causally related to the impairment being treated (Carper, Makover, & Kendall, Citation2018; Kazdin, Citation2007). As we consider the variety of treatments that have been evaluated for ADHD and the development of new treatments, it is critical that future research explicitly focus on identifying mechanisms of change that account for treatment effects and aligning intervention approaches to impact the identified mechanism. Using three common treatment approaches described below, we examine the status of research on mechanisms of change related to each.

Behavior Modification

The core elements of a behavioral approach to treatment have historically focused on the use of operant and classical conditioning by parents and teachers. Some research exists indicating that much of the impairment associated with ADHD reflects a performance deficit, not a skills acquisition deficit (e.g., Aduen et al., Citation2018). This finding may explain why psychoeducation approaches are not effective with these children (e.g., traditional social skills training; Evans et al., Citation2018), but can be effective when taught in the context of an intensive behavioral program that uses operant conditioning principles to address performance deficits (Pelham et al., Citation2014). In addition, there has been research on malleable characteristics of children with ADHD that may explain the effectiveness of behavior modification approaches, such as reward sensitivity (Tenenbaum et al., Citation2018; Tripp & Alsop, Citation2001). Identification and an improved understanding of malleable constructs that are causally related to impairment in children with ADHD will help us improve our behavioral interventions and their long-term benefits.

Cognitive Strategies

Cognitive or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has an interesting history for youth with ADHD. The original putative mechanism of change for CBT was that children with ADHD were not adequately thoughtful before acting and by teaching children to think out loud, one could improve their thoughtfulness, planning, and problem-solving prior to exhibiting impulsive behaviors (e.g., Meichenbaum & Goodman, Citation1971). Although one could teach children with ADHD to do this during sessions, the skill rarely persisted after leaving the clinician. CBT reemerged in the last decade as a potential approach to treating adolescents and adults with ADHD; however, clinical trials of CBT with adolescents with ADHD have not resulted in improvements in functioning (e.g., Boyer et al., Citation2015; Sprich et al., Citation2016; Vidal et al., Citation2015), and the potential mechanism of change specifically related to ADHD has not been clearly elucidated. Further, although negative self-statements are commonly observed in adolescents with ADHD (like James), and cognitions are likely malleable, there is not yet evidence to suggest that they are causally related to the impairment that is specific to ADHD. In fact, it may be that adolescents and adults with ADHD develop these depression-related cognitive factors as a result of persistent ADHD-related impairment over time and these factors are causally related to the emergence of comorbid depression. This is consistent with recent findings that almost 50% of young adolescents with ADHD experience a decline in their self-worth, and those with decreasing self-worth were more likely than their peers with ADHD without decreasing self-worth to have higher depressive symptoms at age 15 (Dvorsky, Langberg, Becker, & Evans, Citation2019). In order to develop effective cognitive interventions for youth with ADHD, there is a critical need to improve our understanding of cognitive factors that may be causally related to impairment associated with ADHD and to develop techniques to effectively change those specific factors. It is important to consider the possibility that CBT may not be a fruitful path for adolescents with ADHD. Most disorders that can be treated effectively with CBT (e.g., anxiety, depression) involve individuals who think too much (e.g., ruminating, worry) and their thinking is thought to affect their emotions and behavior (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, Citation1979). Conversely, adolescents with ADHD tend to not think enough before acting (i.e., impulsivity) and there are questions about the degree with which their thoughts adequately shape their behavior. Thus, changing the nature of their thoughts may not effectively translate to behavior change.

Training Interventions

Training interventions have emerged as an alternative to behavior therapy for youth with ADHD. Training interventions begin with brief psychoeducation about a target skill (e.g., materials organization) and the majority of the time after that is spent with extensive practice and performance feedback. It has been recommended that for training to be effective, the skill must be directly applicable to an area of impairment, and practice with performance feedback must occur frequently and over an extended period of time (Evans et al., Citation2018). Studies with children (Abikoff et al., Citation2013) and young adolescents (Langberg et al., Citation2012) with ADHD indicate that training and behavioral interventions have similar short-term benefits, but there is evidence unique to training interventions that their long-term benefits may meaningfully exceed those of other treatments (Evans et al., Citation2016). It may be that once skills are established through a training intervention, they become routine and persist longer than behaviors shaped by rewards. Increasing our understanding of the mechanisms for training interventions can lead to development of optimally effective approaches. In addition, training interventions have been applied to relatively few areas of impairment (e.g., study and organization skills) and evaluating them across the diverse range of functioning may yield new tools for treatment.

Recommendation 2: Examine Impact of Development on Treatment Mechanisms and Outcomes

In the first several decades of ADHD treatment research, there was little focus on developmental level. For example, in the series of four evidence-based treatment reviews for youth with ADHD that began in 1998 (Evans, Owens, & Bunford, Citation2014; Pelham & Fabiano, Citation2008; Pelham et al., Citation1998), it was not until the most recent version that levels of evidence were differentiated based on ages of participants (Evans et al., Citation2018). Indeed, all of the issues addressed previously in the discussion of mechanisms of change are not static, as mechanisms are likely to change across development. Thus, it is critical to identify relevant mechanisms at each stage of development. However, even if the mechanism remains the same across development, treatment outcomes may also differ as a function of development. For example, one developmental issue is that effect sizes of behavioral interventions may diminish as children age into adolescence (Sanders, Kirby, Tellegen, & Day, Citation2014). Although it is unlikely that behavioral principles become less relevant as children age, it is possible that the ability of an adult to adequately manage the complexities of reinforcement and punishment that operate in the life of a 15-year-old adolescent is far less than an adult’s ability to manage these in the life of a 5-year-old. The complex web of contingencies in the environment of adolescents means that parents and teachers are competing with numerous other sources of reinforcement and punishment (e.g., peer attention, social reputation issues, variety of achievement goals). Understanding not only the behavioral mechanisms of action, but also those associated with cognitive and training interventions across development are likely to lead the field to new and innovative approaches to treatment.

Recommendation 3: Design Intervention Research Informed by a Life Course Model

Research clearly indicates that ADHD is a chronic condition. A childhood diagnosis of ADHD places individuals at risk for deleterious outcomes in adulthood, regardless of their ADHD diagnostic status later in life (Hechtman et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA) found that beneficial effects of behavioral and medication treatment for ADHD implemented during childhood were not maintained into adolescence and young adulthood (Molina et al., Citation2009). To address the chronic nature of ADHD, the need for sustained monitoring of outcomes over time, the changing presentation of the condition and associated risks over the course of development, and the need for intervention at various points during development (illustrated in the case of James), our team has espoused a life course model of care. This model is complementary with key elements of the chronic care model, which has been recommended as a framework for the management of ADHD (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], Citation2019; Van Cleave & Leslie, Citation2008). Three components of the chronic care model are especially relevant for ADHD intervention development: (1) systems to support population-based care; (2) strategies to facilitate alliances across systems; and (3) strategies to promote self-management of one’s own condition.

Systems to Support Population-Based Care

Historically, care for children with ADHD has been conceptualized at the individual level; services are provided to one child at a time in a reactive manner by responding to problems when they emerge (see the case of James). In contrast, a population-based approach examines the population of children served by an agency or organization (e.g., school district, primary care network), and tracks outcomes for all individuals in the population over an extended period of time. A population-based approach creates opportunities for proactive involvement with children who are identified as being at risk. Services are provided in the context of a multi-tiered or multi-layered system of care to provide the right level of care in the most efficient manner.

Research in Schools

A considerable body of research has been conducted in schools to examine how a population-based approach can be applied. In some school systems, all students are tracked with regard to reading and math performance, and behavioral functioning. Indices of behavioral functioning might include suspensions, office discipline referrals, and frequent ratings of behavior by teachers using brief checklists (Christ, Riley-Tillman, & Chafouleas, Citation2009). Data from these tracking methods are used to determine whether: (a) the child can be supported using evidence-based strategies that can be readily implemented to the entire classroom (Tier 1); (b) additional support may be required using brief, but individualized evidence-based practices (Tier 2); or (c) more intensive evidence-based approaches are needed, which in some cases might require special education resources (Tier 3; Sugai & Horner, Citation2006). Unfortunately, there is very little research on how to translate assessment results into choice of interventions or even tiers of interventions.

Future research should focus on how progress monitoring data can be used to inform decisions about moving up and down a tiered (layered) model of service delivery. Using population-based data, benchmarks indicating the probability of achieving positive outcomes at each tier could be proposed and evaluated. Further, adaptive or sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART) designs (e.g., Pelham et al., Citation2016) could be used to test sequences of tiered interventions and movement to different tiers of care based on response to intervention and attainment of benchmarks. Such research may be particularly important during transitions in schooling such as entry into elementary, promotion to middle or high school, and transition from high school to early adulthood.

Research in Health Systems

Similar to schools, a body of research has emerged supporting the use of a population-based approach for the care of individuals with chronic illnesses (e.g., asthma, diabetes) or at risk for poor health outcomes in the context of health systems. Unfortunately, there has been a striking lack of research to guide the application of this approach related to pediatric behavioral health conditions in health systems, including primary care. Additional research is needed to identify the elements of an approach targeting all children and adolescents with ADHD in primary care. For example, electronic systems are being developed to support the assessment of ADHD and monitoring of outcomes (Epstein et al., Citation2011), but we have much to learn about how data in the electronic health record (EHR) can be used (e.g., through registries) to support universal care for children with ADHD and decision making to move to higher tiers of care when needed.

Strategies to Facilitate Alliances across Systems

Services for children and adolescents with ADHD are offered in several settings, especially schools, primary care practices, and mental health agencies (public and private). Unfortunately, service delivery is fragmented and there is poor coordination across systems of care, often resulting in parents being placed in the challenging position of linking systems (Guevara et al., Citation2005), as was the case for James. At least three approaches have been attempted to facilitate alliances across systems. One approach has been to use electronic information systems to assess ADHD symptoms and impairments and monitor outcomes; assess parent-reported goals for treatment and monitor goal attainment; and share information across systems of care (i.e., families, schools, primary care practices; Power et al., Citation2016). Because electronic information systems have the potential to be provided to a large portion of the population of individuals with ADHD, they have been proposed as part of universal approaches to care (Power, Mautone, Blum, Fiks, & Guevara, Citation2019).

Another approach is to enlist patient navigators to promote collaborations among systems of care. This approach has been proposed as a Tier 2 strategy for families and providers who need an intermediate level of support (Power et al., Citation2019). To date, there has been minimal research on the use of care managers to support care for children with ADHD and critical components of the role of these providers.

A third approach, proposed as a Tier 3 strategy, is to embed evidence-based interventions in the context of integrated methods of service delivery in primary care (Kolko et al., Citation2014). Integrated primary care offers a mechanism to promote collaboration between pediatric providers and mental health professionals in the delivery of evidence-based psychosocial and pharmacological interventions. A limitation is that this approach typically does not promote connections with schools, although models of integrated care have been adapted to link families, schools, and pediatric providers (Power et al., Citation2014). There are many challenges to research related to this work including the feasibility and acceptability of these approaches. For example, there is evidence that the value of integrating services may not be widely shared across professional groups. One study reporting an attempt at integrating teachers’ ratings of children’s behavior into the medication decisions of psychiatrists reported extreme difficulties getting teachers to complete ratings and even when ratings were collected, psychiatrists rarely considered the teacher data when making decisions regarding medication treatment (Pliszka et al., Citation2003). This is just one example of the substantial research challenges that need to be addressed when pursuing the goal of an integrated approach to primary care.

Strategies to Promote Self-Management

Parents have a high level of responsibility for the management of ADHD, especially when children are young. Parents can benefit from psychoeducation (Ferrin et al., Citation2014), as well as strategies to promote readiness for change and motivation to pursue services (Nock & Kazdin, Citation2005). Although the major focus of efforts to promote parental empowerment has been on parents of young children with this condition, it is important to address parents’ ongoing needs for psychoeducation and motivational support, particularly during periods when their children are struggling and resources seem to be lacking. In addition to targeting parents, starting in the upper elementary years, and certainly by middle school, youth with ADHD are capable of assuming some responsibility for the management of their condition. It is important for them to become aware of their limitations in paying attention and regulating their behaviors and emotions, their need for academic and social support, and evidence-based strategies to assist them. In spite of the importance of youth with ADHD to learn how to manage their own care, there is very little research on how to promote their empowerment in managing ADHD. There are exciting opportunities to develop programs to promote youth empowerment to manage ADHD across the developmental span from elementary school through secondary school and into early adulthood.

Recommendations for Future Research in Implementation and Dissemination

The four evidence-based treatment reviews for ADHD (Evans, Owens, & Bunford, Citation2014; Evans et al., Citation2018; Pelham & Fabiano, Citation2008; Pelham et al., Citation1998) that cover over 60 years’ worth of research reveal a striking imbalance toward efficacy studies relative to effectiveness studies. In the last review, less than 10% of studies evaluated treatments implemented by practitioners (i.e., non-research staff). Although efficacy studies have been critical to the identification of evidence-based treatment (EBTs), with so few effectiveness trials, the next generation of research should prioritize studying EBTs under authentic conditions (e.g., with referred rather than recruited cases, implemented by practitioners rather than research staff). Implementation research is the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic adoption of research findings and evidence-based practices into routine practice, with the goal of improving the quality of care (Eccles & Mittman, Citation2006). One example of implementation research involves hybrid effectiveness-implementation trials wherein both implementation and treatment outcomes are evaluated simultaneously (Landes, McBain, & Curran, Citation2019). In a hybrid design, researchers can (1) test the effects of a clinical intervention on relevant outcomes while gathering information on implementation; (2) simultaneously test a clinical intervention and an implementation strategy; or (3) test an implementation strategy while gathering information of a clinical intervention’s impact on child outcomes. We recommend that the field focus on implementation science approaches, including hybrid designs, to study EBTs under authentic conditions to enhance the state of the science related to EBTs for ADHD in three critical areas: access, implementation fidelity, and cost-effectiveness.

Recommendation 4: Develop and Evaluate Strategies that Promote Treatment Access

As described previously, despite strong evidence distinguishing EBTs from other practices, most children coping with ADHD lack access to evidence-based psychosocial treatment (Danielson et al., Citation2018; DuPaul et al., Citation2019). In order to have EBTs make a significant impact on the nearly 7 million youth struggling with ADHD, the next generation of research must develop and evaluate strategies for ensuring that EBTs reach the majority of those affected by the disorder.

One mechanism that can be leveraged to enhance access to EBTs is technology. There are several examples where technology has been pilot tested as a means to enhancing access to care in primary care offices and schools, yet additional work is needed. For example, there is emerging evidence that technology, such as electronic health records (EHR) with templates specific to ADHD and with reminders for quality care actions can increase the likelihood of assessment of ADHD and quality documentation of that assessment (e.g., Johnson et al., Citation2010). Also as discussed previously, electronic systems have been developed to facilitate cross-setting (i.e., primary care offices, schools, and home) communication to enhance access to evidence-based assessment and treatment practices (e.g., Epstein et al., Citation2011). A promising system embedded in the EHR is the ADHD Care Assistant (see Power et al., Citation2016) which was designed to promote (a) shared decision-making between family and provider by identifying family goals and preferences for treatment (Fiks et al., Citation2012) and assessing goal attainment; and (b) the sharing of information among parents, educators, and health providers (Michel et al., Citation2018). Expanded development and evaluation of electronic systems such as the ADHD Care Assistant in the context of pediatric primary care holds the promise of facilitating access to screening, assessment, and early detection of ADHD. Indeed, such a system may have significantly changed the life course for James and his family. However, additional study is needed to overcome barriers to use (e.g., technology support, parent and teacher access to technology) with a specific focus on uptake and sustainment. Additionally, there is a need for expansion of online systems to include measures validated for diagnosis and progress monitoring for preschool and adolescent populations to enhance access to quality assessment for these populations.

Technology is also being leveraged to enhance children’s access to EBTs in schools. For example, using hybrid designs, Owens and colleagues (Mixon, Owens, Hustus, Serrano, & Holdaway, Citation2019; Owens et al., Citation2019) developed and evaluated the Daily Report Card.Online (DRC.O) system, an interactive online resource that facilitates teachers’ knowledge, adoption, and implementation of a daily report card (DRC) intervention. The DRC.O mirrors face-to-face consultation through professional development content (including video models) that teachers can access at their own time and pace, as well as interactive mobile-friendly features designed to support teachers as they develop the DRC, monitor and graph student progress, and modify the intervention over time. Two studies document that, with this technology and very minimal additional support, a meaningful portion of teachers (39% to 54%) can adopt and implement at DRC with positive student outcomes (Mixon et al., Citation2019; Owens et al., Citation2019). However, these were open trials with small samples. Thus, additional more rigorous trials of this and other technologies are needed including study of applications to secondary school students.

Recommendation 5: Identify Strategies to Optimize Implementation Fidelity

Despite the presence of clearly delineated manuals and guidelines for implementation of EBTs for ADHD, many providers are not trained in EBTs and the fidelity with which treatments are implemented is known to degrade when implementation supports and/or accountability are reduced (e.g., Noell et al., Citation1997). Thus, if EBTs are not implemented with high fidelity (as was the case for James), there is likely little chance that they will impact desired youth outcomes (e.g., Owens et al., Citation2018) and ultimately little value in improving access. Thus, two top priorities for future research in the area of enhancing intervention fidelity are the identification of mechanisms for (a) efficient and effective training of those who can provide EBTs for ADHD (e.g., teachers, mental health providers, PCPs) and (b) holding clinicians and teachers accountable for high quality implementation.

There are multiple viable approaches for enhancing training and accountability, and perhaps a combination of these approaches may be necessary. For example, there is emerging evidence that influential peers within a given social network (e.g., teachers within a school, providers within an agency) may be powerful facilitators of enhanced implementation outcomes (e.g., Atkins et al., Citation2008). Although not all specific to ADHD, research is being conducted to determine how influential peers can be efficiently identified and how these influential leaders can be leveraged to enhance others’ knowledge, adoption, and implementation of EBTs (e.g., Cappella & Godfrey, Citation2019). Given the chronic nature of ADHD, a particularly compelling line of research would be to examine how influential peers could facilitate successful transition of students with ADHD across grade levels and school settings.

Second, a review of training strategies across disciplines (Lyon, Stirman, Kerns, & Bruns, Citation2011) highlights the utility of several approaches (e.g., coaching, reminders, problem-based learning) over one-time training in shaping provider behavior. A critical next step in this research is to examine the possible mechanisms of change responsible for the association between training strategies and improvements in provider behavior. By understanding the unique processes responsible for provider behavior change, we may be able to consider which strategies are unique or redundant so that complimentary strategies could be combined to maximize outcomes. In addition, research is needed to examine how such training and implementation supports can be made feasible and sustainable by schools and health/mental health agencies.

Third, there is evidence that measurement feedback systems provided to clinicians can enhance child outcomes (e.g., Bickman, Kelley, Breda, de Andrade, & Riemer, Citation2011). However, this strategy is rarely used in agencies, health systems, or schools. In addition to identifying methods to increase the use of measurement feedback systems in key settings, it will be important to study how the use of technology, influential peers, effective training and feedback systems could be combined to enhance implementation by teachers and clinicians.

Lastly, another innovative mechanism for enhancing quality and desired child outcomes is via a pay-for-success contract. Within such a contract, investors offer capital up front, independent evaluators are leveraged to assess the extent to which desired outcomes are achieved (e.g., cost savings are accrued due to reduction in risk status), and for each success case achieved, the investors receive a return of the principal plus a financial benefit. The U.S. Department of Education has launched several pay-for-success contract projects (https://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/pay-for-success/index.html), some of which are demonstrating promise within rigorous randomized designs (https://ssir.org/articles/entry/pay_for_success_is_working_in_utah). Similarly, health systems are implementing this type of arrangement by focusing on value-based payments through accountable care organizations (i.e., health practices receive lump sums based on patients served and patient outcomes; Rawal & McCabe, Citation2016). Thus, the impact of pay-for-success contracts to optimize ADHD treatment fidelity in health and school settings is a potentially fruitful line for effectiveness research.

Recommendation 6: Examine and Optimize Cost-Effectiveness

As early as the 1998 review (Pelham et al., Citation1998), researchers were recommending analyses to reveal the relative costs and cost effectiveness of behavioral as compared to pharmacological treatments. In the ensuing decade, studies examined the cost-effectiveness of medication management and behavioral intervention as prescribed in the Multi-modal Treatment Study for ADHD (Foster et al., Citation2007; Jensen et al., Citation2001). These studies provided important advancements in our knowledge of cost; however, costs were estimated using treatments provided in the MTA study, which are not replicable and not available in most communities.

Addressing this limitation (i.e., using less intensive treatment protocols), Page et al. (Citation2016) examined the relative cost effectiveness of behavioral, pharmacological, and combined interventions employed in a sequential, adaptive trial investigating the sequencing and enhancement of treatment for children with ADHD (Pelham et al., Citation2016). Findings suggest that starting with a low dose behavioral intervention was less costly ($961) for one year of treatment and more effective in changing impairment in functioning than beginning treatment with a low dose of pharmacological intervention ($1,689). This study is the first to examine treatment sequencing and offers support for the proposed layers in the life course model. However, many more questions about cost remain. For example, from a school perspective, administrators could benefit from knowing the relative cost-effectiveness of various universal school-wide or classwide approaches in preventing the need for more intensive services, or the relative cost-effectiveness of using classroom interventions versus accommodations. School and clinic administrators also could benefit from knowing the relative cost-effectiveness of various models (e.g., technology-driven, one-time training, ongoing consultation) of professional development and implementation supports for teachers and clinicians. Further, to date, published research only reveals cost effectiveness for elementary students; future studies are needed for preschool and adolescent populations, as treatments and risk profiles differ from those for elementary school students.

Conclusions

Given the chronicity of symptoms and impairment associated with ADHD, it is critically important that effective treatment strategies are implemented across home, school, and community settings to reduce symptoms and, most importantly, enhance educational and social functioning over time (see ). Although multiple psychosocial intervention approaches have been found efficacious in the context of controlled investigations, these treatments often are not implemented with sufficient fidelity and/or consistently across systems and time in community and school settings, as was demonstrated by the case of James. Using a life course model as context, we propose six research directions to address major challenges to treatment development, evaluation, implementation, and dissemination. Priorities for psychosocial treatment development and evaluation are to identify and leverage mechanisms of change, examine and address the impact of child developmental status on treatment mechanisms and outcomes, and design intervention research informed by a life course model. Treatment implementation and dissemination investigations should leverage implementation science methods to develop and evaluate strategies that promote access to evidence-based treatment, optimize treatment fidelity in community and school settings, and optimize costs and cost-effectiveness of psychosocial interventions.

To support this work, investigators should consider funding mechanisms such as Clinical Trials to Test the Effectiveness of Treatment Preventive, and Services Interventions offered by the National Institute of Mental Health (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-MH-18-701.html) that are designed to support trials that examine effectiveness of interventions and possible mechanisms of action. Alternative sources of funding that place a priority on effectiveness and implementation research are the Institute of Education Sciences and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Our field needs to go beyond short-term, efficacy trials to reduce ADHD symptoms conducted under ideal controlled conditions and successfully address the research-to-practice gap by advancing development, evaluation, implementation, and dissemination of evidence-based treatment strategies to ameliorate functional impairment that can be used with fidelity by parents, teachers, and community health providers. By focusing research in these directions, we can substantially improve outcomes for youth with ADHD like James.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abikoff, H. B., Gallagher, R., Wells, K. C., Murray, D. W., Huang, L., Lu, F., & Petkova, E. (2013). Remediating organizational functioning in children with ADHD: Immediate and long-term effects from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(1), 113–128. doi:10.1037/a0029648

- Aduen, P. A., Day, T. N., Kofler, M. J., Harmon, S. L., Wells, E. L., & Sarver, D. E. (2018). Social problems in ADHD: Is it a skills acquisition or performance problem? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 440–451. doi:10.1007/s10862-018-9649-7

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019). Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20192528. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-2528

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Atkins, M. S., Frazier, S. L., Leathers, S. J., Graczyk, P. A., Talbott, E., Jakobsons, L., & Bell, C. C. (2008). Teacher key opinion leaders and mental health consultation in low-income urban schools. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 905–908. doi:10.1037/a0013036

- Barkley, R. A., Edwards, G., Laneri, M., Fletcher, K., & Metevia, L. (2001). The efficacy of problem-solving communication training alone, behavior management training alone, and their combination for parent-adolescent conflict in teenagers with ADHD and ODD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 926–941. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.926

- Barkley, R. A., Murphy, K. R., & Fischer, M. (2008). ADHD in adults: What the science says. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Bickman, L., Kelley, S. D., Breda, C., de Andrade, A. R., & Riemer, M. (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1423–1429. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.002052011

- Boyer, B. E., Geurts, H. M., Prins, P. J. M., & Van Der Oord, S. (2015). Two novel CBTs for adolescents with ADHD: The value of planning skills. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24, 1075–1090. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0661-5

- Cappella, E., & Godfrey, E. B. (2019). New perspectives on the child‐and youth‐serving workforce in low‐resource communities: Fostering best practices and professional development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63, 245–252. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12337

- Carper, M. M., Makover, H. B., & Kendall, P. C. (2018). Future directions for the examination of mediators of treatment outcomes in youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47, 345–356. doi:10.1080/15374416.2017.1359786

- Chacko, A., Wymbs, B. T., Flammer-Rivera, L. M., Pelham, W. E., Walker, K. S., Arnold, F. W., & Herbst, L. (2008). A pilot study of the feasibility and efficacy of the Strategies to Enhance Positive Parenting (STEPP) program for single mothers of children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 270–280. doi:10.1177/1087054707306119

- Chorozoglou, M., Smith, E., Koerting, J., Thompson, M. J., Sayal, K., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. (2015). Preschool hyperactivity is associated with long-term economic burden: Evidence from a longitudinal health economic analysis of costs incurred across childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 966–975. doi:10.1111/jcpp.2015.56.issue-9

- Christ, T. J., Riley-Tillman, C. T., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2009). Foundation for the development and ese of direct behavior rating (DBR) to assess and evaluate student behavior. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 34(4), 201–213. doi:10.1177/1534508409340390

- Conner, D. F. (2015). Stimulant and nonstimulant medications for childhood ADHD. In R. A. Barkley (Ed.), Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed., pp. 666–685). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Danielson, M. L., Bitsko, R. H., Ghandour, R. M., Holbrook, J. R., Kogan, M. D., & Blumberg, S. J. (2018). Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47, 199–212. doi:10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860

- Danielson, M. L., Visser, S. N., Chronis-Tuscano, A., & DuPaul, G. J. (2018). A national description of treatment among U.S. children and adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Pediatrics, 192, 240–246. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.040

- DuPaul, G. J., & Langberg, J. M. (2015). Educational impairments in children with ADHD. In R. A. Barkley (Ed.), Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed., pp. 169–190). New York, NY: Guilford.

- DuPaul, G. J., Chronis-Tuscano, A., Danielson, M. L., & Visser, S. N. (2019). Predictors of receipt of school services in a national sample of youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23, 1303–1319. doi:10.1177/1087054718816169

- DuPaul, G. J., Eckert, T. L., & Vilardo, B. (2012). The effects of school-based interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis 1996-2010. School Psychology Review, 41, 387–412.

- Dvorsky, M. R., Langberg, J. M., Becker, S. P., & Evans, S. W. (2019). Trajectories of global self-worth in adolescents with ADHD: Associations with academic, emotional, and social outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 48, 765–780. doi:10.1080/15374416.2018.1443460

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

- Epstein, J. N., Langberg, J. M., Lichtenstein, P. K., Kolb, R., Altaye, M., & Simon, J. O. (2011). Use of an Internet portal to improve community-based pediatric ADHD care: A cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics, 128(5), 1201–1208. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0872

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., Mautone, J., DuPaul, G. J., & Power, T. J. (2014). Toward a comprehensive, life course model of care for youth with ADHD. In M. Weist, N. Lever, C. Bradshaw, & J. Owens (Eds.), Handbook of school mental health (2nd ed., pp. 413–426). New York, NY: Springer.

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., & Power, T. J. (2019). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In M. J. Prinstein, E. A. Youngstrom, E. J. Mash, & R. A. Barkley (Eds.), Treatment of childhood disorders (4th ed., pp. 47–101). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Evans, S. W., Langberg, J. M., Schultz, B. K., Vaughn, A., Altaye, M., Marshall, S. A., & Zoromski, A. K. (2016). Evaluation of a school-based treatment program for young adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 15–30. doi:10.1037/ccp0000057

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., & Bunford, N. (2014). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43, 527–551. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.850700

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., Wymbs, B. T., & Ray, R. R. (2018). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47, 157–198. doi:10.1080/15374416.2017.1390757

- Fabiano, G. A., Chacko, A., Pelham, W. E., Robb, J., Walker, K. S., Wymbs, F. A., … Pirvics, L. L. (2009). A comparison of behavioral parent training programs for fathers of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behavior Therapy, 40(2), 190–204. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2008.05.002

- Fabiano, G. A., Pelham, W. E., Jr., Coles, E. K., Gnagy, E. M., Chronis-Tuscano, A., & O’Connor, B. C. (2009). A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 29–140. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.11.001

- Fabiano, G. A., Schatz, N. K., Morris, K. L., Willoughby, M. T., Vujnovic, R. K., Hulme, K. F., … Wylie, A. (2016). Efficacy of a family-focused intervention for young drivers with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(12), 1078–1093. doi:10.1037/ccp0000137

- Ferrin, M., Moreno-Granados, J. M., Salcedo-Marin, M. D., Ruiz-Veguilla, M., Perex-Ayala, V., & Taylor, E. (2014). Evaluation of a psychoeducation programme for parents of children and adolescents with ADHD: Immediate and long-term effects using a blind randomized controlled trial. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 23, 637–647. doi:10.1007/s00787-013-0494-7

- Fiks, A. G., Mayne, S., Hughes, C., DeBartolo, E., Behrens, C., Guevara, J. P., & Power, T. J. (2012). Development of an instrument to measure parents’ preferences and goals for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Academic Pediatrics, 12, 445–455. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2012.04.009

- Foster, E. M., Jensen, P. S., Schlander, M., Pelham, W. E., Jr, Hechtman, L., Arnold, L. E., … Wigal, T. (2007). Treatment for ADHD: Is more complex treatment cost‐effective for more complex cases? Health Services Research, 42(1p1), 165–182. doi:10.1111/hesr.2007.42.issue-1p1

- Frazier, T. W., Youngstrom, E. A., Glutting, J. J., & Watkins, M. (2007). ADHD and achievement: Meta-analysis of the child, adolescent, and young adult literatures and a concomitant study with college students. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40, 49–65. doi:10.1177/00222194070400010401

- Guevara, J., Fuedtner, C., Romer, D., Power, T., Eiraldi, R., Nihtianova, S., … Schwarz, D. (2005). Fragmented care for inner-city minority children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 116, e512–e517. PMCID: PMC1255962. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0243

- Hechtman, L. (2017). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Adult outcome and its predictors. New York, NY: Oxford.

- Hechtman, L., Swanson, J. M., Sibley, M. H., Stehli, A., Owens, E. B., Mitchell, J. T., … Abikoff, H. B. (2016). Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: MTA results. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(11), 945–952. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774

- Jensen, P. S., Hinshaw, S. P., Swanson, J. M., Greenhill, L. L., Conners, C. K., Arnold, L. E., … March, J. S. (2001). Findings from the NIMH multimodal treatment study of ADHD (MTA): Implications and applications for primary care providers. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 22(1), 60–73. doi:10.1097/00004703-200102000-00008

- Johnson, S. A., Poon, E. G., Fiskio, J., Rao, S. R., Van Cleave, J., Perrin, J. M., & Ferris, T. G. (2010). Electronic health record decision support and quality of care for children with ADHD. Pediatrics, 126(2), 239–246. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0710

- Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

- Kolko, D. J., Campo, J., Kilbourne, A. M., Hart, J., Sakolsky, D., & Wisniewski, S. (2014). Collaborative care outcomes for pediatric behavioral health problems: A cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics, 133(4), e981–e992. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2516

- Landes, S. J., McBain, S. A., & Curran, G. M. (2019). An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psychiatry Research. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019/112513

- Langberg, J., Epstein, J. N., Becker, S. P., Girio-Herrera, E., & Vaughn, A. J. (2012). Evaluation of the homework, organization, and planning skills (HOPS) intervention for middle school students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as implemented by school mental health professionals. School Psychology Review, 41, 342–364.

- Lyon, A. R., Stirman, S. W., Kerns, S. E., & Bruns, E. J. (2011). Developing the mental health workforce: Review and application of training approaches from multiple disciplines. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(4), 238–253. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0331-y

- Meichenbaum, D. H., & Goodman, J. (1971). Training impulsive children to talk to themselves: A means of developing self-control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 77, 115–126. doi:10.1037/h0030773

- Michel, J. J., Mayne, S., Grundmeier, R. W., Guevara, J. P., Blum, N. J., Power, T. J., … Fiks, A. G. (2018). Sharing of ADHD information between parents and teachers using an EHR-linked application. Applied Clinical Informatics, 9, 892–904. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1676087

- Mikami, A. (2010). The importance of friendship for youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 181–198. doi:10.1007/s10567-010-0067-y

- Mixon, C. S., Owens, J. S., Hustus, C., Serrano, V. J., & Holdaway, A. S. (2019). Evaluating the impact of online professional development on teachers’ use of a targeted behavioral classroom intervention. School Mental Health, 11(1), 115–128. doi:10.1007/s12310-018-9284-1

- Molina, B. S. G., Hinshaw, S. P., Swanson, J. M., Arnold, L. E., Vitiello, B., Jensen, P. S., & Houck, P. R. (2009). The MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(5), 484–500. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0

- Nock, M. K., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for increasing participation in parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 872–879. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.872

- Noell, G. H., Witt, J. C., Gilbertson, D. N., Ranier, D. D., & Freeland, J. T. (1997). Increasing teacher intervention implementation in general education settings through consultation and performance feedback. School Psychology Quarterly, 12, 77–88. doi:10.1037/h0088949

- Normand, S., Schneider, B. H., Lee, M. D., Maisonneuve, M., Chupetlovska-Anastova, A., Kuehn, S. M., & Robaey, P. (2013). Continuities and changes in the friendships of children with and without ADHD: A longitudinal, observational study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 1161–1175. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9753-9

- Owens, J. S., Coles, E. K., Evans, S. W., Himawan, L. K., Girio-Herrera, E., Holdaway, A. S., & Schulte, A. (2017). Using multi-component consultation to increase the integrity with which teachers implement behavioral classroom interventions: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 9, 218–234. doi:10.1007/s12310-017-9217-4

- Owens, J. S., Evans, S. W., Coles, E. K., Himawan, L. K., Holdaway, A. S., Mixon, C., & Egan, T. (2018). Consultation for classroom management and targeted interventions: Examining benchmarks for teacher practices that produce desired change in student behavior. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. doi:10.1177/106342661879544

- Owens, J. S., McLennan, J., Hustus, C., Haines-Saah, R., Mitchell, S., Mixon, C. S., & Troutman, A. (2019). Evaluating the impact of the Daily Report Card.Online (DRC.O) system: Replication and expansion. School Mental Health. doi: 10.1007/s12310-019-09320-6.

- Page, T. F., Pelham, W. E., III, Fabiano, G. A., Greiner, A. R., Gnagy, E. M., Hart, K. C., … Pelham, W. E., Jr. (2016). Comparative cost analysis of sequential, adaptive, behavioral, pharmacological, and combined treatments for childhood ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(4), 416–427. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1055859

- Pelham W. E. Jr., Wheeler, T., & Chronis, A. (1998). Empirically supported psychosocial treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27, 190–205. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_6

- Pelham, W. E., Burrows-MacLean, L., Gnagy, E. M., Fabiano, G. A., Coles, E. K., Wymbs, B. T., … Waschbusch, D. A. (2014). A dose-ranging study of behavioral and pharmacological treatment in social settings for children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(6), 1019–1031. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9843-8

- Pelham, W. E., & Fabiano, G. A. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 184–214. doi:10.1080/15374410701818681

- Pelham, W. E., Jr., Fabiano, G. A., Waxmonsky, J. G., Greiner, A. R., Gnagy, E. M., & Pelham, W. E., III. (2016). Treatment sequencing for childhood ADHD: A multiple-randomization study of adaptive medication and behavioral interventions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45, 396–415. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1105138

- Pliszka, S. R., Lopez, M., Crismon, M. L., Toprac, M. G., Hughes, C. W., Emslie, G., & Boemer, C. (2003). A feasibility study of the Children’s Medication Algorithm Project (CMAP) algorithm for the treatment of ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 279–287. doi:10.1097/00004583-200303000-00007

- Power, T. J., Mautone, J. A., Blum, N. J., Fiks, A. G., & Guevara, J. P. (2019). Integrated behavioral health: Coordinating psychosocial and pharmacological interventions across family, school, and health systems. In J. S. Carlson & J. A. Barterian (Eds.), School psychopharmacology: Translating research into practice (pp. 195–212). New York, NY: Springer.

- Power, T. J., Mautone, J. A., Marshall, S. A., Jones, H. A., Cacia, J., Tresco, K. E., … Blum, N. J. (2014). Feasibility and potential effectiveness of integrated services for children with ADHD in urban primary care practices. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 2, 412–426. doi:10.1037/cpp0000056

- Power, T. J., Michel, J., Mayne, S., Miller, J., Blum, N. J., Grundmeier, R. W., … Fiks, A. G. (2016). Coordinating systems of care using health information technology: Development of the ADHD care assistant. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 9, 201–218. doi:10.1080/1754730X.2016.1199283

- Rawal, P., & McCabe, M. A. (2016). Health care reform and programs that provide opportunities to promote children’s behavioral health. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

- Robb, J. A., Sibley, M. H., Pelham, W. E., Jr., Foster, E. M., Molina, B. S. G., Gnagy, E. M., & Kuriyan, A. B. (2011). The estimated annual cost of ADHD to the US education system. School Mental Health, 3, 169–177. doi:10.1007/s12310-011-9057-6

- Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. I., & Day, J. J. (2014). The triple P-positive parenting program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 337–357. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003

- Sibley, M. H., Graziano, P. A., Kuriyan, A. B., Coxe, S., Pelham, W. E., & Rodriguez, L., ... Ward, A. (2016). Parent-teen behavior therapy + motivational interviewing for adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 699–712.

- Sprich, S. E., Safren, S. A., Finkelstein, D., Remmert, J. E., & Hammerness, P. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 57, 1218–1226. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12549

- Sugai, G., & Horner, R. R. (2006). A promising approach for expanding and sustaining school-wide positive behavior support. School Psychology Review, 35(2), 245–259.

- Tenenbaum, R. B., Musser, E. D., Raiker, J. S., Coles, E. K., Gnagy, E. M., & Pelham, W. E. (2018). Specificity of reward sensitivity and parasympathetic-based regulation among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity and disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 965–977. doi:10.1007/s10802-017-0343-0

- Tripp, G., & Alsop, B. (2001). Sensitivity to reward delay in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 691–698. doi:10.1111/jcpp.2001.42.issue-5

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. (2019, August). Many Medicaid-enrolled children who were treated for ADHD did not receive recommended followup care. OEI-07-17-00170. Retrieved from oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-07-17-00170.asp

- Van Cleave, J., & Leslie, L. K. (2008). Approaching ADHD as a chronic condition: Implications for long-term adherence. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 46(8), 28–37. doi:10.3928/02793695-20080801-07

- Vidal, R., Castells, J., Richarte, V., Palomar, G., Garcia, M., Nicolau, R., … Ramos-Quiroga, J. A. (2015). Group therapy for adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 275–282. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.016