ABSTRACT

Objective: Behavioral teacher training is the most effective classroom-based intervention for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, it is currently unknown which components of this intervention add to its effectiveness and for whom these are effective.

Method: In this microtrial, teachers of 90 children with impairing levels of ADHD symptoms (6–12 years) were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a short (2 sessions), individualized intervention consisting of either (A) antecedent-based techniques (stimulus control), (B) consequent-based techniques (contingency management) or (C) waitlist. Primary outcome was the average of five daily assessments of four individualized problem behaviors, assessed pre and post intervention and three months later. Moderation analyses were conducted to generate hypotheses on child, teacher and classroom factors that may contribute to technique effectiveness.

Results: Multilevel analyses showed that both antecedent- and consequent-based techniques were equally and highly effective in reducing problem behaviors compared to the control condition (Cohen’s d =.9); effects remained stable up to three months later. Child’s age and class size were moderators of technique effectiveness. For younger children, consequent-based techniques were more effective than antecedent-based techniques, whereas for older children the effect was in the opposite direction. Further, beneficial effects of antecedent-based techniques increased when the number of students per class decreased, whilst effectiveness of consequent-based techniques did not depend on class size.

Conclusions: This study shows that both antecedent- and consequent-based techniques are highly effective in reducing problem behavior of children with ADHD. Interventions may be adapted to the child’s age and class size.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and/or impulsivity (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), often leading to difficulties at school with regard to behavioral problems (e.g., impulsive and oppositional behaviors), academic performance (e.g., lower grades) and social problems (e.g., problems in the interaction with peers) (Daley & Birchwood, Citation2010; Kirova et al., Citation2019; Wilens et al., Citation2002). ADHD is one of the most common childhood psychiatric disorders, with approximately 5% of children worldwide meeting full criteria for the disorder (Polanczyk et al., Citation2007, Citation2014), and 10–15% of children experiencing impairing levels of symptoms without meeting full criteria for a diagnosis (Hong et al., Citation2014; Kirova et al., Citation2019).

Behavioral teacher training is the most effective non-pharmacological classroom intervention to counteract the symptoms of ADHD and related behavior problems (Daley et al., Citation2014; Evans et al., Citation2014, Citation2018; Fabiano et al., Citation2009), and to reduce teacher burden and increase levels of teacher self-efficacy (Ross et al., Citation2012). In behavioral teacher training, teachers are taught to change a child’s behavior by using stimulus control techniques. These techniques aim at changing behaviors by manipulating their antecedents, or stimulus conditions, to increase the chance that a child elicits desired behavior, by establish and strengthen the relation between the stimulus condition and response (i.e., child behavior). Such antecedent-based techniques include providing structure and clear instructions, aimed at clarifying what behavior is expected of a child in a specific situation. In addition, teachers are taught contingency management techniques aimed at changing behaviors by manipulating its consequences. According to the principles of behavioral theory, the frequency of behavior will increase when this is followed by positive consequences (e.g., introducing a reward or taking away a penalty), and decrease or fade out when this is followed by negative consequences (e.g., taking away a reward or introducing a penalty). Examples of such consequent-based techniques are the use of praise, ignoring or mild punishment (DuPaul & Eckert, Citation1997; Owens et al., Citation2018). Most current interventions comprises both sets of techniques to reduce children’s problem behavior, with different focus on either predominantly antecedent- or more consequent-based techniques (DuPaul & Eckert, Citation1997; DuPaul & Stoner, Citation2003).

Currently, effect sizes for behavioral teacher training interventions are medium at best, and heterogeneity in effect sizes between studies is large (Daley et al., Citation2014). To increase the effectiveness of behavioral teacher training and to be able to individualize intervention plans, it is of importance to study which intervention components (i.e., sets of techniques) contribute to its effectiveness (e.g., Leijten et al., Citation2015), and to gain insight into child, teacher and classroom factors that moderate effectiveness. Such studies are currently lacking and are needed to optimize treatment outcome for children with ADHD (DuPaul et al., Citation2020; Schatz et al., Citation2020).

According to review studies that compared interventions predominantly consisting of antecedent- or consequent-based techniques, both sets of techniques are effective in reducing problem behavior in children with (symptoms of) ADHD (Gaastra et al., Citation2016; Harrison et al., Citation2019). The few studies that focused on effectiveness of specific consequent-based techniques showed that time out from positive reinforcement is effective in reducing disruptive behavior problems in children with ADHD symptoms (Fabiano et al., Citation2004; Northup et al., Citation1999; Pfiffner et al., Citation2006), although a time-out procedure also requires clear rules and therefore also contains (some) antecedent-based techniques. Further, a meta-analysis by Gaastra et al. (Citation2016) including within-subjects design studies, showed that interventions consisting of predominantly consequent-based techniques were significantly more effective (MSMD = 1.82) than interventions including predominantly antecedent-based techniques (MSMD = 0.31) in reducing off-task and disruptive classroom behavior of children with ADHD. However, so far the effectiveness of these different sets of techniques in isolation has not been examined in a head-to-head comparison, which is important to rule out nonspecific treatment effects and to be sure that intervention effects are not contaminated by the other component. An experimental method to study and compare the effectiveness of these sets of techniques and investigate moderators of effect is a microtrial (Howe et al., Citation2010; Leijten et al., Citation2015).

Microtrials are randomized experiments testing the effects of relatively brief and focused environmental manipulations (i.e., intervention components) (Howe et al., Citation2010). These experiments can measure whether the environmental manipulations bring about meaningful, immediate, change in specific, proximal outcomes (e.g., change in problem behavior targeted with the intervention component directly after delivering the intervention), rather than distal outcomes (e.g., ADHD symptoms in general) that are measured over a longer period of time (Leijten et al., Citation2015). Microtrials could therefore bridge the gap between laboratory or field studies and full-scale trials (Howe et al., Citation2010; Leijten et al., Citation2015) by gaining knowledge on effective intervention components and the identification of specific subgroups that are more or less responsive. Such knowledge can be used for developing more personalized treatment approaches (e.g., does the focus need to be on more antecedent- or consequent-based techniques in school-based settings?) as well as strengthening existing interventions or the preparation of full-scale trials.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate antecedent- and consequent-based techniques in behavioral teacher training for children with ADHD symptoms. For the purpose of this microtrial, we developed two short behavioral interventions focusing on either antecedent-based (stimulus control) or consequent-based (contingency management) techniques. Based on previous findings (see for reviews: Gaastra et al., Citation2016; Harrison et al., Citation2019), we expected that both antecedent- and consequent-based techniques would be effective in reducing problem behaviors on proximal outcomes (i.e., inattention, hyperactive-impulsive and/or oppositional behavior problems targeted in the intervention) compared to a waitlist control group. Although experimental evidence based on randomized controlled trials is lacking, we hypothesized, based on Gaastra et al. (Citation2016), that effects of consequent-based techniques would be larger than effects of antecedent-based techniques. We explored whether several variables moderated the effectiveness of the techniques to generate hypotheses regarding which set of techniques is more effective for which child, teacher and/or class, which is of pivotal importance to tailor future interventions to individual needs. Moderation analyses within microtrials are powerful to detect moderation effects given that only one aspect of an intervention (i.e., set of techniques) is manipulated and its immediate effects are measured on proximal outcomes (Howe & Ridenour, Citation2019). The moderators of interest were demographic and clinical variables that are commonly available in clinical or school-based practice, such as the age, and severity of problems of the child, as well as sense of efficacy, student-teacher relationship and treatment expectancy of the teacher, and the number of students in class. The teacher and class related moderators have all been found related to the effectiveness of behavioral interventions (Durlak & DuPre, Citation2008; Finn et al., Citation2003; Girolametto et al., Citation2003; Vancraeyveldt et al., Citation2015; Williford et al., Citation2015).

Method

Design

This study consisted of two intervention conditions (i.e., antecedent- and consequent-based, see below) and a waitlist control condition, with 30 children and their teachers participating in every condition. One of the authors, who had no contact with the teachers (ML), created a random list of numbers 1–90 to allocate teachers to one of three conditions. Randomization occurred at school level to prevent contamination from teachers receiving an intervention, to teachers in the control condition or to teachers receiving the other intervention (e.g., information drift from a teacher in the antecedent condition to a teacher in the consequent condition, and vice versa). Outcome measures were assessed in all three conditions at three time points: at baseline prior to randomization (T0), during the week immediately after the two intervention sessions, or the two-weeks waiting period (T1), and three weeks after the intervention or waiting period (T2). Given that microtrials are aimed at experimentally assessing immediate effects (Leijten et al., Citation2015) (T1 and T2), assessments of longer term effects were explorative (follow-up three months after baseline, T3). The total study duration was three months (T0-T3) and allowed no holidays between randomization and T2. In case the summer holiday started prior to T3, T3 took place three weeks prior to the end of the school year (but at least four weeks after T2). Since there are no guidelines for reporting on microtrials, we used the CONSORT guidelines for reporting on randomized controlled trials (Moher et al., Citation2001).

Participants

Participants were teachers seeking help with the behavior of one of their students showing ADHD symptoms, and were recruited through school principals, educational consulting associations, and an outpatient mental health clinic. Teachers of 90 children from 52 schools aged between 6 and 12 years old participated in this study. Teachers could participate with a maximum of two students. A total of 30 children (from 25 classrooms of 17 schools) were allocated to the antecedent condition, 30 children (from 26 classrooms of 18 schools) were allocated to the consequent condition, and 30 children (from 26 classrooms of 17 schools) were allocated to the control condition (waitlist).

Children attended regular primary education throughout The Netherlands, in both rural and urban areas, and displayed impairing levels of teacher rated ADHD symptoms. Children were included if they: (a) obtained a score > 90th percentile on the teacher rated Inattention and/or Hyperactivity/Impulsivity scale of the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBDRS) (Oosterlaan et al., Citation2008; Pelham et al., Citation1992), (b) showed at least three symptoms (Veenman et al., Citation2016) on the Inattention and/or Hyperactivity/Impulsivity scale of the semi-structured Teacher Telephone Interview (TTI) (Tannock et al., Citation2002), based on the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000), and (c) obtained a score > 5 (indicating impairment, range 0– 10) on at least one domain of functioning on the teacher rated Impairment Rating Scale (IRS) (Fabiano et al., Citation2006). For five children inclusion took place before summer holiday. For these children impairment was based on the fact that the teacher was seeking help to cope with the child’s behavior, which was substantiated by TTI scores. Children were excluded if they: (a) had an estimated full scale IQ < 70, estimated using a short form of the Dutch version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-third edition (WISC-III-NL) (Wechsler et al., Citation2005) including the subtests Block Design and Vocabulary (Sattler, Citation2008), (b) were taking psychotropic medication during the last month, (c) had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder or conduct disorder according to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000) or DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) as reported by parents on a demographic questionnaire, or (d) if the teacher had received a behavioral teacher training aimed at ADHD symptoms or other behavioral problems in the past year. To check for pervasiveness of symptoms in the home situation, parents filled out the Hyperactivity scale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) at baseline (Goodman, Citation1997). The flowchart presented in displays the inclusion process of participants.

Interventions

Two short interventions were investigated, the antecedent-based intervention using only antecedent-based techniques and the consequent-based intervention using only consequent-based techniques. The interventions consisted of two individual sessions with the teacher by a trained psychologist, the first lasting two hours and taking place at the school, and the second scheduled one week later, lasting 45 minutes, and taking place by video conference. After each session, teachers were instructed to implement the techniques in the classroom for four weeks, and teachers could consult the therapist if required. These protocollized interventions were based on evidence-based behavioral parent training programs (Barkley, Citation1987; McMahon & Forehand, Citation2003; van den Hoofdakker et al., Citation2007) aimed at remediating ADHD and ADHD related behaviors, and consisted of psycho-education on ADHD and training of stimulus control and contingency management techniques.

Common Elements in Both Interventions

Interventions were targeted at four preselected problem behaviors from a list of 32 ADHD-related behaviors (see below), with both sessions targeting one selected problem behavior in one specifically chosen situation (see below) (e.g., difficulties staying focused during individual seatwork). The other two problem behaviors were not directly targeted in the intervention. The first session started with psycho-education about ADHD behaviors. Thereafter, one problem behavior was selected by the teacher in collaboration with the therapist, based on the severity and frequency of occurrence (preferably daily) of the problem behavior. Depending on the intervention condition (see below), the therapist and teacher made a behavioral analysis by identifying (a) antecedents that elicit the problem behavior, or (b) consequences that positively or negatively reinforce the problem behavior (i.e., functional behavior assessment, FBA; Dunlap & Kern, Citation2018). In the next step they defined desired target behavior. The therapist and teacher made a behavioral intervention plan with antecedent- or consequent-based techniques, depending on the assigned intervention condition. This procedure allowed us to have an individually tailored intervention plan for both problem behaviors of every child. The session ended with practicing the technique(s) through role-play and/or visualization. The teacher implemented the plan in the classroom for one week, after which the second session took place. This session started with evaluating the preceding week and adapting the intervention plan, if necessary. Thereafter, the therapist and teacher selected a second problem behavior occurring in a specific situation, and went through the same steps as in the first session (i.e., from behavioral analysis to practicing). The teacher received handouts of the specific techniques trained.

Antecedent-based Intervention

In the antecedent-based intervention (referred to as antecedent condition), teachers were taught how stimuli evoke behaviors and how executive functioning deficits in children with ADHD may lead to difficulties adapting behavior to stimuli. The therapist and teacher identified which antecedents elicited the selected problem behavior. Thereafter, teachers were taught how antecedent-based techniques may be used prior to the onset of behavior and how to alter stimuli in order to elicit changes in child behaviors (Owens et al., Citation2018). Given the experimental set-up of the microtrial that was aimed to study specific intervention components, teachers were only taught antecedent-based techniques in the antecedent condition. The following techniques were briefly explained in this intervention: setting clear rules, providing clear instructions, discussing challenging situations with the child in advance, and providing structure in time and space. One or more techniques were chosen to be part of the intervention plan, based on the behavioral analysis. When teachers brought up that they could use techniques from the other condition (e.g., reward desired behavior), the therapists were instructed to respond that that is a known technique, but that the current training focused on implementing antecedent-based techniques first.

As an example, a desired target behavior may be: “This child can work individually for five minutes on the assigned math task, without asking the teacher for help”. In the antecedent condition, the intervention plan may consist of (1) the teacher giving appropriate individual instructions to the child after the class wide instruction; (2) the child having a step-by-step plan with illustrations (i.e., pictograms) on how to proceed the task and what to do when a question arises; and (3) a timer on the child’s desk to show the remaining time.

Consequent-based Intervention

In the consequent-based intervention (referred to as consequent condition), teachers were taught how consequences affect behavior and that children with ADHD may suffer from an altered reward sensitivity that may influence how their behavior is shaped by the environment. The therapist and teacher identified which consequences positively or negatively reinforced or discouraged desired target behavior. Thereafter, teachers were taught how consequent-based techniques may be used following (un)desired behavior to affect the occurrence of specific behavior. The following techniques were briefly explained in this intervention: praise, reward, planned ignoring and negative consequences. When the full desired behavior was not displayed yet by the child, shaping was explained (rewarding of short sequences of the desired behavior) with the aim to elicit the full desired behavior. Consequent-based techniques such as token economy and time-out were not taught in this intervention given that these techniques also require antecedent-based techniques (e.g., clear rules, discussing in advance). As in the antecedent-based intervention, techniques for the intervention plan were chosen based on problem behavior and behavioral analysis, no antecedent-based techniques were taught, and when teachers suggested to add an antecedent-based technique to the intervention plan they were told to focus on consequent-based techniques first.

As an example, a desired target behavior may be: “This child can work individually for five minutes on the assigned math task, without asking the teacher for help”. The intervention plan in the consequent condition may consist of (1) the teacher frequently rewarding the child’s (attempts to display the) desired behavior (e.g., praise or thumbs up when the child is working or quiet); (2) the teacher praising other children who are working on their task; and (3) the teacher ignoring all of the child’s attention-seeking behavior (e.g., raising hand, calling the teacher’s name).

Therapists

Two psychologists with postgraduate training in behavioral therapy and ADHD and trained in using the intervention protocol (AS and RH), carried out the intervention. To assess intervention fidelity, we measured therapists’ adherence to the protocol based on contamination and the percentage addressed session items. Contamination was assessed using the procedures of Abikoff (Abikoff et al., Citation2013), and defined as therapists’ actions that resulted in the incorporation of features from the non-assigned intervention (e.g., consequent) into the assigned intervention (e.g., antecedent). This could occur either by the therapist recommending the use of non-assigned techniques or the therapist actively supporting and elaborating on the teacher’s suggestions of the use of techniques specific to the non-assigned intervention. The frequency of contamination occurrences in a session served as the outcome. We also assessed the percentage of addressed session items in each session (18 items in session one, 11 items in session two). Furthermore, all intervention sessions were audiotaped. For every therapist, the first session of both conditions were checked on intervention fidelity by two of the authors who are behavior therapists and licensed supervisors in the postgraduate behavior therapy program with ample experience in behavioral parent and teacher training programs (SvdO and BvdH). Fidelity scores were discussed with the therapist during individual supervision sessions. Further, ten percent of the sessions were listened back and scored on intervention fidelity during the study by independent evaluators. After each session, the therapists completed a fidelity checklist in which they were asked which items were covered. During the entire study, therapists and researchers held meetings every two weeks to monitor intervention fidelity and to provide supervision.

Outcome Measures

Daily Measurements of Problem Behaviors

Our primary outcome measure was the assessment of four individual problem behaviors which were derived by teachers from a list of target behaviors (van den Hoofdakker et al., Citation2007), listing 32 possible problem behaviors related to ADHD, including inattentive, hyperactive and impulsive symptoms, and oppositional defiant behaviors. Reliability of this list in the current sample was excellent (α = .90). The daily assessment of target behaviors is derived from the method used by van den Hoofdakker et al. (Citation2007), and can be considered as ecological momentary assessment procedure (EMA; Bolger et al., Citation2003; Shiffman et al., Citation2008). EMA involves repeated assessment of the participant’s behavior in real time and in its natural environment (Bentley et al., Citation2019), therefore minimizing bias and maximizing ecological validity. Such ratings of behaviors combine the advantages of direct observation and the efficiency of questionnaires (Chafouleas et al., Citation2009), are easy to administer, and can be used in multiple settings and for multiple behaviors (Miller & Fabiano, Citation2017).

Teachers rated whether the 32 problem behaviors occurred daily (yes, no), and if yes, they scored the severity on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not severe) to 5 (exceptionally severe). Examples of problem behaviors are: “difficulties staying focused”, “often loses things necessary to work”, “talking excessively”, and “being noncompliant”. From the problem behaviors that occurred daily, teachers selected four problem behaviors they wanted to address during the intervention. Thereafter, for all four problem behaviors, teachers selected a situation in which this behavior occurred most, or was most severe. Situations were derived from the School Situations Questionnaire (SSQ, DuPaul & Barkley, Citation1992). Examples of situations are: “individual seatwork”, “whole class group teaching”, and “at recess”. These four problem behaviors in specific situations were assessed by daily, brief (one to two-minutes) and protocollized phone calls on five consecutive days of a school week at every time point. Trained graduate students, who were masked to the type of intervention condition, made the phone calls. In these phone calls, the researcher repeated the four problem behaviors and teachers rated, for every problem behavior, (a) if the behavior occurred that day and if yes, (b) the severity of each of the observed problem behaviors on a 5-point Likert scale. The mean score over four problem behaviors on five consecutive days served as our dependent variable. To motivate teachers to implement the techniques, at the end of the phone call, teachers in the intervention conditions were asked whether they implemented the intervention plan during that day.

Potential Moderators

We tested several child, teacher and classroom variables as potential moderators. We assessed the following child related factors: age, sex, IQ, ADHD symptom severity, ODD symptom severity (TTI, Tannock et al., Citation2002), school impairment as rated by teachers (i.e., number of domains impaired, range 1– 5) (IRS, Fabiano et al., Citation2006), and daily ratings of problem behaviors at baseline (i.e., four behaviors measured on five days). The following teacher and classroom related factors were tested: self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, RSES, Rosenberg, Citation1965) (range total score: 10– 40), sense of efficacy (Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale – short version, TSES, Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2001) (range mean: 1– 9), perception of the student-teacher relationship (Student-Teacher Relationship Scale – short version, STRS, Koomen et al., Citation2012; Pianta, Citation2001) (range total score: 15– 75), treatment expectancy of the teacher (Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire, CEQ, Devilly & Borkovec, Citation2000) (range total score: 0– 30), and class size (i.e., number of students). For a detailed description of the instruments included in moderation analyses see Supplementary Material S1.

Procedure

Teachers interested in participating received an information letter explaining the research aims and responsibilities of all parties involved. They enlisted one to two children showing profound and impairing ADHD symptoms in the classroom, and informed parents about the study (i.e., provided them with the information letter and informed consent). Teachers, parents, and children older than 11 years, provided consent. After receiving consent, teachers were administered the DBDRS and TTI to screen for eligibility. Baseline assessments took place assessing the child’s behavior during a period of five consecutive schooldays (T0). After the baseline assessments were completed, children were randomized to one of the three conditions. To prevent information drift between teachers, randomization occurred at school level (see Design) and after randomization, no new teachers could enter the study. Teachers of the children either received the two-week lasting antecedent- or consequent-based intervention, or were assigned to the two-weeks control condition (waitlist). Teachers of children in the control condition were allowed to receive care as usual during the study period, and were offered the possibility to use a self-directed behavioral teacher program targeting ADHD symptoms immediately after T2 (PR Program, Veenman et al., Citation2016). Longer term effects were therefore only explored in children of teachers in the active intervention arms. There was no financial compensation for participating in the study. The study procedure was approved by the local medical ethical committee (University Medical Center Groningen, 2016/198) and was carried out between April 2017 and April 2019.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare groups on the demographic variables assessed at baseline.

Effects of Techniques

Multilevel analyses (mixed model) were conducted in Stata (version 16), to compare the intervention conditions to the control condition. Four hierarchical levels were distinguished: observations (level 1), nested within children (level 2), nested in classrooms (level 3), and nested in schools (level 4). Random intercepts at classroom and school level were only included if significantly improving model fit as determined by Likelihood Ratio Test. We inserted condition (control, antecedent, consequent) as between subjects factor, and time (T1, T2) as within subjects variable. Baseline scores (T0) of the outcome were inserted as fixed factor, in order to control for problems at baseline. We investigated effects of condition (averaged over T1 and T2) to compare the intervention conditions to the control condition, and to compare the two intervention conditions to each other. We added the condition by time interaction to the model to test whether there were differences between conditions in development of problem behaviors on specific time points. Additional within conditions analyses were conducted to test when a significant change in problem behaviors occurred. Longer term effects were assessed by examining whether problem behaviors remained stable from T2 to T3 within each intervention condition (i.e., whether the development of problem behaviors from T2 to T3 changed significantly). We also checked whether effects were different for the two behaviors targeted in the intervention sessions, compared to effects averaged over four problem behaviors per child. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated by dividing the difference in mean scores between two conditions averaged over T1 and T2 (short term effects) by the pooled SD (Rosnow & Rosenthal, Citation1996), with .20, .50, and .80 as thresholds for small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Cohen, Citation2013).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine whether intervention effects differed between type of problem behaviors (i.e., inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive or oppositional defiant behaviors), and whether intervention effects were different for children with and without a diagnosis of ADHD. Finally, if children started pharmacological treatment after baseline, sensitivity analyses were conducted without these participants to check if this might have influenced the results.

Moderators

We explored whether child, teacher and classroom related factors moderated intervention effects by adding interactions between the intervention condition and the potential moderator to the multilevel model. We examined whether a factor significantly moderated the intervention effect (averaged over T1 and T2) when comparing both intervention conditions with each other (i.e., antecedent versus consequent condition).

Intervention Fidelity

By using independent t-tests, the contamination scores and percentages of addressed session items were compared between intervention conditions.

Results

displays background characteristics of the sample. Conditions did not differ on any of the screening characteristics (p > .132), with the exception of hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms on the TTI and DBDRS. In the consequent condition three children had a comorbid learning disorder.

Table 1. Background characteristics of the sample

In total, 23 children (26%) had a diagnosis of ADHD as indicated on a demographic questionnaire by parents. None of the parents indicated that children had a diagnosis of ODD. Based on parental report on the Hyperactivity scale of the SDQ, 90% (n = 78) of the parents scored the symptoms of their children in the clinical range (Maurice-Stam et al., Citation2018).

Teachers had a mean age of 38.3 years (SD = 12.0), 91% was female and teachers on average had 14.4 years (SD = 11.3) of teaching experience. There were no differences between conditions (p = .418, p = .722, p = .053, respectively).

Intervention Fidelity

Therapist Reported Fidelity

Therapists’ reports of fidelity showed that on average respectively 98.9% and 99.4% (SD = 2.26, N = 29; SD = 1.37, N = 30) of the session items were carried out in the sessions of the antecedent and consequent condition. Fidelity did not differ between the two intervention conditions (t(45.77) = −1.13, p = .266).

Recorded Fidelity

Based on the recorded sessions, average protocol adherence was high in both conditions (antecedent = 98.0%, consequent = 97.8%). Contamination occurred once in a session of the consequent-based intervention and was not scored in any of the antecedent-based sessions. Contamination did not differ between the two interventions (t(3.00) = −1.00, p = .391).

Effects of Techniques

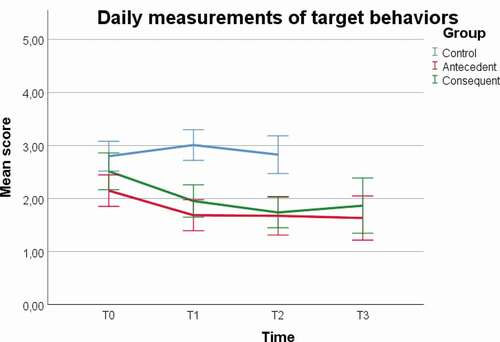

Results on the daily measurements of the four problem behaviors are depicted in and (means and standard deviations at all time points are reported in Supplementary Material S2, Table A). For all outcomes, the random intercepts at levels “school” and “classroom” did not significantly improve the models, so therefore all models were reduced to two levels (observations clustered in children).

Table 2. Effects of condition on different time points

Figure 2. Observed values for the development over time in the three conditions. Scores are means across four problem behaviors measured on five consecutive days

shows the development of problem behaviors over time for the three conditions. After controlling for baseline problems, teachers in both the antecedent and consequent condition reported significant reductions in problem behavior of their student(s) compared to teachers in the control condition, with large effect sizes (see ). There were no significant differences in the reduction of the child’s problem behavior between the two intervention conditions up to T2. Further, effects for both intervention conditions were similar when only the two problem behaviors that were targeted in the intervention were included in the analyses and compared to the control condition: for antecedent: B = −.92, SE = .18, p < .001, d = .86; for consequent: B = −1.04, SE = .18, p < .001, d = .98.

Additional within condition analyses in the antecedent condition showed that problem behaviors decreased significantly from T0 to T1 (B = −.44, SE = .14, p = .002), and remained stable from T1 to T2 (B = −.02, SE = .14, p = .866). For the consequent condition, results showed the same pattern: problem behaviors significantly decreased from T0 to T1 (B = −.56, SE = .14, p < .001), and remained stable from T1 to T2 (B = −.22, SE = .14, p = .133). In the control condition, problem behaviors did not significantly differ between the time points (for T0 to T1: B = .21, SE = .14, p = .146; for T1 to T2: B = .03, SE = .14, p = .842).

Further, within condition analyses assessing longer term effects revealed that problem behavior of children in the intervention conditions remained stable from T2 to T3 (for antecedent: B = −.09, SE = .15, p = .562; for consequent: B = .07, SE = .16, p = .649) (see and ), indicating that the intervention effects persisted up to three months after the start of the intervention. Completers and non-completers of T3 did not differ on any of the baseline characteristics (p > .084). At T3 (N = 53), the majority of the teachers reported to still use the techniques (n = 22 [81%] in antecedent condition; n = 21 [81%] in consequent condition).

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses showed that effect sizes were large for inattentive behaviors (for the antecedent condition [n = 26] versus control condition [n = 19]: B = −.80, SE = .24, p = .001, d = .74, and for the consequent condition [n = 27] versus control condition: B = −1.02, SE = .23, p < .001, d = .95), and oppositional defiant behaviors (for antecedent [n = 19] versus control [n = 19]: B = −.96, SE = .25, p < .001, d = .79; for consequent [n = 12] versus control: B = −.99, SE = .28, p < .001, d = .82). For problem behaviors related to hyperactivity/impulsivity, effect sizes were medium (for antecedent condition [n = 21] versus control condition [n = 28]: B = −.65, SE = .25, p = .009, d = .56; for consequent condition [n = 24] versus control condition: B = .58, SE = .23, p = .011, d = .50).

Sensitivity analyses with the children without a diagnosis of ADHD (n = 67) revealed that results for problem behaviors remained unchanged (from T0 to T2 for antecedent versus control: B = −.82, SE = .17, p < .001, d = .87; for consequent versus control: B = −.93, SE = .16, p < .001, d = .72). Again, there were no differences between the antecedent and consequent condition (B = −.14, SE = .16, p = .385, d = .15).

One child in the consequent condition started pharmacological treatment (methylphenidate) after T0, and five more children started with methylphenidate after T2 (antecedent n = 3, consequent n = 2). To check whether starting with pharmacological treatment affected the results, multilevel analyses were repeated without the children who started medication. Results remained unchanged from T0 to T2 (for antecedent versus control: B = -.87, SE = .16, p < .001, d = .87; for consequent versus control: B = −.85, SE = .15, p < .001, d = .86; for antecedent versus consequent: B = −.01, SE = .15, p = .935, d = .01). Analyses within the intervention conditions also revealed that excluding children who started medication did not affect intervention effects from T2 to T3 (for antecedent: B = −.04, SE = .16, p = .824; for consequent: B = .08, SE = .17, p = .644).

Moderators of Technique Effectiveness

The correlation matrix of the assessed moderators and outcome variable (daily ratings of problem behaviors at T0) is depicted in Supplementary Material S3 (Table B). Planned moderating analyses with sex could not be performed because there were not enough girls in our sample, but sensitivity analyses without girls revealed approximately similar results (from T0 to T2 for antecedent versus control: B = −.77, SE = .18, p < .001, d = .78; for consequent versus control: B = −.80, SE = .17, p < .001, d = .80).

For age, there was an intervention condition (antecedent versus consequent) by age interaction (see ). Further analyses based on median split analyses (median = 8.5 years) showed that for younger children (< 8.5 years) the consequent-based intervention was significantly more effective than the antecedent-based intervention (B = .50, SE = .23, p = .030, d = .50), although the intervention was effective for both age groups. For older children (> 8.5 years), the effect was in the opposite direction: the antecedent-based intervention was significantly more effective than the consequent-based intervention (B = −.49, SE = .20, p = .013, d = .50), with again, the intervention being effective for both groups.

Table 3. Results of moderator analyses (factor by intervention interaction)

For the classroom factor (i.e., class size: number of students, range 14 to 32, median = 24), the antecedent versus consequent comparison revealed a significant moderating effect for class size, showing that within the antecedent condition, the intervention effect was larger when the number of students was smaller (B = .07, SE = .02, p < .001), whereas in the consequent condition the intervention effect was unrelated to the number of students (B = −.01, SE = .03, p = .700), see .

No other significant moderator effects were found, see .

Discussion

The present study examined the effectiveness of antecedent- and consequent-based techniques in behavioral teacher training for children with impairing levels of ADHD symptoms, using a microtrial. Our results indicate that the antecedent- and consequent-based techniques are both highly effective in reducing problem behaviors related to ADHD on the short and longer term (i.e., up to three months later). Effect sizes were large for problem behaviors related to inattention and oppositional defiant symptomatology, and medium-sized for hyperactive-impulsive behavior, with no differences in effect size between both interventions.

Our findings diverge from the meta-analysis by Gaastra et al. (Citation2016) who showed that interventions consisting of predominantly consequent-based techniques were more effective than predominantly antecedent-based interventions. In that meta-analysis, most of the antecedent-based interventions mainly consisted of nonspecific general classroom interventions (e.g., class-wide peer tutoring, music at the background or extended time), in contrast to the consequent-based interventions that were all directly tailored to the behavior of a specific child (e.g., teacher-administered reinforcement, prudent negative consequences). Further, consequent-based interventions often included antecedent-based techniques (e.g., teacher-administered reinforcement included a visible table on the child’s desk to count rewards). Consequent-based interventions included in the meta-analysis were thus potentially more powerful, as reflected in reported larger effects.

The effectiveness of both sets of techniques on reducing problem behaviors was similar to those of full interventions (van den Hoofdakker et al., Citation2007), and effects were irrespective of diagnostic status of the child. We individually tailored both the antecedent- and consequent-based interventions to the needs of the teacher and the child, and the large effect sizes obtained with both sets of techniques may point to the importance of individual tailoring. Behavioral analysis (i.e., FBA) was used to discover patterns in (problem) behavior, for example, in the consequent condition the techniques were adapted to the function of a child’s target behavior, which may have increased effectiveness (Chronis et al., Citation2004; Dunlap & Kern, Citation2018; Ervin et al., Citation2000; Harrison et al., Citation2019; Miller & Lee, Citation2013; Pfiffner et al., Citation2006). Further, the short and focused nature of our intervention may have added to large effect sizes. Focusing on one behavior and teaching a few techniques may be more feasible for teachers than programs in which multiple techniques are being taught over a longer time frame, especially for overloaded teachers. Providing teachers with a detailed intervention plan that can be implemented directly into the classroom may be more effective compared to general recommendations on parenting strategies for ADHD that are not tailored to individual needs. Further, our dependent variables were those behaviors targeted in the intervention, and this choice may possibly have increased the effects obtained and emphasizes the use of ecologically valid measures. Lastly, training effects remained stable up to three months later, whilst problem behaviors usually are found to increase after treatment is withdrawn (Han & Weiss, Citation2005), and for microtrials one would generally not expect distal effects (Howe et al., Citation2010; Leijten et al., Citation2015). Since the follow-up period of the current study was within a school year, and therefore shorter compared to the follow-up period included in a meta-analysis of parent training studies (Lundahl et al., Citation2006; Pelham & Fabiano, Citation2008), this might explain why our effects lasted until follow-up. Further, the relatively simple and individualized intervention plan may be easy to remember and implement, also in the long run.

The second aim of this study was to generate hypotheses about “what works for whom”, by exploring potential moderators of intervention component effects. The results showed that the antecedent- and consequent-based techniques are effective, regardless of IQ, symptom severity of ADHD and ODD, school impairment, and baseline ratings of problem behaviors. Effectiveness was related to the age of the child. For younger children, consequent-based techniques were significantly more effective than antecedent-based techniques, whereas for older children effects of antecedent-based techniques were larger than effects of consequent-based techniques. This is in line with the development of motivational styles. Over time, children develop from more extrinsic to more intrinsic motivational styles, wherefore extrinsic reinforcements may be less powerful in older children (Deci et al., Citation1991; Evans et al., Citation2019). Further, teachers of higher grades, in general, provide less structure and have higher expectations of children regarding initiating and maintaining attention for prolonged periods of time (Harrison et al., Citation2019), whilst planning problems become more prominent when children grow older (Langberg et al., Citation2013), allowing these children to benefit more from external structure by teachers.

Besides child factors, we explored whether characteristics of the teacher and classroom impacted on technique effectiveness. Teacher’s self-esteem, sense of efficacy, perception of the student-teacher relationship, and treatment expectancy of the teacher did not moderate effects. Although dealing with students with ADHD has been found stressful to teachers (Greene et al., Citation2002), and student-teacher relationships are often worse for these children (Ewe, Citation2019), apparently this did not affect the effectiveness of the current interventions. Class size moderated technique effectiveness, with the beneficial effects of the antecedent-based techniques increased when the number of students per class decreased, whereas the effectiveness of the consequent-based techniques did not depend on class size. This finding is in line with the literature on the benefits of low class size for student engagement (see for review Finn et al., Citation2003), indicating that teachers in smaller classes may have more possibilities to one-on-one interactions with students and provide better student support, which in turn may be related to increased engagement in learning and less behavioral problems (Biddle & Berliner, Citation2002).

Current findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, behavioral teacher training programs usually consist of a combination of antecedent- and consequent-based techniques and one might argue that they were separated somewhat artificially for the purpose of this microtrial. Teachers were trained specifically in one set of techniques and the sole focus was on training teachers how to implement this set most optimally. Given the short and personalized nature of the intervention, teachers were highly focused on implementing the intervention plan and rarely reported on the (self-initiated) use of techniques of the other set (i.e., condition) during evaluations at the second session. However, we neither tracked the extent to which teachers used techniques of the other condition nor did we track the use of strategies for other students than the target student. Thus, we cannot fully rule out the possibility that training antecedent-based techniques (e.g., providing clear rules) may have elicited (an increase of) the use of consequent-based techniques (e.g., providing more praise to a child as a result of evoking desired behavior) (Sutherland et al., Citation2002), and vice versa. Nevertheless, the high levels of therapists’ intervention fidelity and our moderation analyses pointing toward specific effects of antecedent-based and consequent-based techniques show that it appeared possible to separate training of specific techniques, and indicate that eliciting the use of other techniques may be a beneficial side effect of the intervention. Second, despite large effect sizes, intervention effects described here were based on teacher informed measures who may have been biased in reporting positive effects (Daley et al., Citation2014; Sonuga-Barke et al., Citation2013). However, individual daily rated problem behaviors using EMA procedures, such as used here, may overcome possible recall or memory bias that can be seen in ratings using questionnaires (Chafouleas et al., Citation2009). Further, researchers who conducted daily phone calls were not masked to whether teachers were in active training condition or control condition, because they asked whether the intervention was implemented that day. However, since phone calls were brief and protocollized, and researchers were not aware in which active condition the teachers were in, researcher bias is unlikely. Future research may include single blinded EMA and/or use blinded observations of the problem behavior to test whether our findings are confirmed by blinded outcomes. Third, although we showed the effectiveness of antecedent- and consequent-based techniques in this study, it is unclear to what extent both sets of techniques add to each other. Single case experimental designs may be used to assess the additional effects of both sets of techniques (Kazdin, Citation2019). Lastly, moderation analyses were done as a first attempt to study what works for whom. We explored multiple (potential) moderators in a relatively small sample, which generated important hypotheses for future treatment development and research regarding potential effects of age of the child and class size on the effectiveness of the techniques studied. However, due to limited power, weaker moderators may have remained undetected. Further research is needed to replicate these findings and draw more strong conclusions about subgroups that are more or less likely to respond to the different sets of techniques.

Clinical Implications and Future Studies

Although the aim of this study was to examine intervention components rather than developing a new intervention, results showed that the current interventions appeared to be as effective as other teacher training programs in reducing problem behaviors. The current interventions may be optimized by combining both highly effective sets of techniques in one intervention. Given the need for short, brief, and evidence based behavioral teacher interventions (DuPaul et al., Citation2019; Gaastra et al., Citation2020), that are preferably individually tailored (Egan et al., Citation2019), a short and individually tailored approach such as used in the current study seems to meet these demands. Our finding that most of the teachers continued to use the techniques up to three months later, strengthens our idea that the current intervention meets teacher needs. After testing its effectiveness, this optimized intervention with both sets of techniques may be implemented as stand-alone first-line treatment to provide teachers with psycho-education and individually tailored advices on behavioral management for ADHD (NICE Guidelines, Dutch Guidelines; Akwa, Citation2019; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Citation2018).

Future studies may take generalization of effects on broader outcomes such as ADHD rating scales or impairment measures into account, albeit reductions in individually chosen problem behavior as reported by the teacher may be most relevant for the teachers themselves (Cuijpers, Citation2019). Further, it is of interest to examine whether neuropsychological functioning of the child affects the technique effectiveness. We will further investigate this as part of our larger research project.

Conclusion

To conclude, both antecedent- and consequent-based techniques are highly effective in reducing problem behaviors of a diverse and representative sample of primary school-aged Dutch children with impairing levels of ADHD (i.e., subthreshold or clinical ADHD), on the short and longer term. There are some indications that age and class size may affect technique effectiveness, which is important information for treatment development and tailoring. The short and individualized nature of the intervention may have added to its effectiveness. Given the high teacher workload and increase in number of students with ADHD in regular primary education, a short and individualized intervention, such as developed in the current study and including both sets of techniques, may be implemented as stand-alone treatment.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (34.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank all children, parents and teachers for participating in this study, and students for their support in data collection.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (AS), upon reasonable request.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1846542.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abikoff, H. B., Gallagher, R., Wells, K. C., Murray, D. W., Huang, L., Lu, F., & Petkova, E. (2013). Remediating organizational functioning in children with ADHD: Immediate and long-term effects from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(1), 113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029648

- Akwa, G. G. Z. (2019). Zorgstandaard ADHD [Dutch ADHD guidelines]. https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/zorgstandaarden/adhd/samenvatting

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th, text revision ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Barkley, R. A. (1987). Defiant children. Guilford press.

- Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Elliott, G., Huffman, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2019). Real-time monitoring technology in single-case experimental design research: Opportunities and challenges. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 117, 87–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.017

- Biddle, B. J., & Berliner, D. C. (2002). What research says about small classes and their effects. Policy Perspectives.

- Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030

- CBS. (2016). Standaard onderwijsindeling 2016 [The Dutch Standard Classification of Education]. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Chafouleas, S. M., Kilgus, S. P., & Hernandez, P. (2009). Using Direct Behavior Rating (DBR) to screen for school social risk: A preliminary comparison of methods in a kindergarten sample. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 34(4), 214–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508409333547

- Chronis, A. M., Chacko, A., Fabiano, G. A., Wymbs, B. T., & Pelham Jr, W. E. (2004). Enhancements to the behavioral parent training paradigm for families of children with ADHD: Review and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/B:CCFP.0000020190.60808.a4

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

- Cuijpers, P. (2019). Targets and outcomes of psychotherapies for mental disorders: An overview. World Psychiatry, 18(3), 276–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20661

- Daley, D., & Birchwood, J. (2010). ADHD and academic performance: Why does ADHD impact on academic performance and what can be done to support ADHD children in the classroom? Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(4), 455–464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01046.x

- Daley, D., Van der Oord, S., Ferrin, M., Danckaerts, M., Doepfner, M., Cortese, S., … Group, E. A. G. (2014). Behavioral interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across multiple outcome domains. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(8), 835–847. e835. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.05.013

- Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 325–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1991.9653137

- Devilly, G. J., & Borkovec, T. D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31(2), 73–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4

- Dunlap, G., & Kern, L. (2018). Perspectives on functional (behavioral) assessment. Behavioral Disorders, 43(2), 316–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742917746633

- DuPaul, G. J., & Barkley, R. A. (1992). Situational variability of attention problems: Psychometric properties of the revised home and school situations questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21(2), 178–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2102_10

- DuPaul, G. J., Chronis-Tuscano, A., Danielson, M. L., & Visser, S. N. (2019). Predictors of receipt of school services in a national sample of youth with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(11), 1303–1319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718816169

- DuPaul, G. J., & Eckert, T. L. (1997). The effects of school-based interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 26(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1997.12085845

- DuPaul, G. J., Evans, S. W., Mautone, J. A., Owens, J. S., & Power, T. J. (2020). Future directions for psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(1), 134–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1689825

- DuPaul, G. J., & Stoner, G. (2003). ADHD in the schools: Assessment and practice. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

- Egan, T. E., Wymbs, F. A., Owens, J. S., Evans, S. W., Hustus, C., & Allan, D. M. (2019). Elementary school teachers’ preferences for school‐based interventions for students with emotional and behavioral problems. Psychology in the Schools, 56(10), 1633–1653. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22294

- Ervin, R. A., Kern, L., Clarke, S., DuPaul, G. J., Dunlap, G., & Friman, P. C. (2000). Evaluating assessment-based intervention strategies for students with ADHD and comorbid disorders within the natural classroom context. Behavioral Disorders, 25(4), 344–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/019874290002500403

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., & Bunford, N. (2014). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(4), 527–551. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.850700

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., Wymbs, B. T., & Ray, A. R. (2018). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 157–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1390757

- Evans, S. W., Van der Oord, S., & Rogers, E. E. (2019). Academic functioning and interventions for adolescents with ADHD. In S. P. Becker (Ed.), ADHD in adolescents: Development, and treatment (pp. 148–328). The Guilford Press.

- Ewe, L. P. (2019). ADHD symptoms and the teacher–student relationship: A systematic literature review. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(2), 136–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2019.1597562

- Fabiano, G. A., Pelham, J., William, E., Waschbusch, D. A., Gnagy, E. M., Lahey, B. B., Chronis, A. M., & Burrows-MacLean, L. (2006). A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 369–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3

- Fabiano, G. A., Pelham, W. E., Jr, Coles, E. K., Gnagy, E. M., Chronis-Tuscano, A., & O’Connor, B. C. (2009). A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.11.001

- Fabiano, G. A., Pelham, W. E., Jr, Manos, M. J., Gnagy, E. M., Chronis, A. M., Onyango, A. N., … Meichenbaum, D. L. (2004). An evaluation of three time-out procedures for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 449–469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80027-3

- Finn, J. D., Pannozzo, G. M., & Achilles, C. M. (2003). The “why’s” of class size: Student behavior in small classes. Review of Educational Research, 73(3), 321–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543073003321

- Gaastra, G. F., Groen, Y., Tucha, L., & Tucha, O. (2016). The effects of classroom interventions on off-task and disruptive classroom behavior in children with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. PloS One, 11(2), e0148841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148841

- Gaastra, G. F., Groen, Y., Tucha, L., & Tucha, O. (2020). Unknown, unloved? Teachers' reported use and effectiveness of classroom management strategies for students with symptoms of ADHD. Child & Youth Care Forum, 49, 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09515-7

- Girolametto, L., Weitzman, E., & Greenberg, J. (2003). Training day care staff to facilitate children’s language. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(3), 299–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2003/076)

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

- Greene, R. W., Beszterczey, S. K., Katzenstein, T., Park, K., & Goring, J. (2002). Are students with ADHD more stressful to teach? Patterns of teacher stress in an elementary school sample. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/10634266020100020201

- Han, S. S., & Weiss, B. (2005). Sustainability of teacher implementation of school-based mental health programs. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(6), 665–679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-7646-2

- Harrison, J. R., Soares, D. A., Rudzinski, S., & Johnson, R. (2019). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorders and classroom-based interventions: Evidence-based status, effectiveness, and moderators of effects in single-case design research. Review of Educational Research, 89(4), 569–611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319857038

- Hong, S.-B., Dwyer, D., Kim, J.-W., Park, E.-J., Shin, M.-S., Kim, B.-N., … Hong, Y.-C. (2014). Subthreshold attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is associated with functional impairments across domains: A comprehensive analysis in a large-scale community study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(8), 627–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0501-z

- Howe, G. W., Beach, S. R., & Brody, G. H. (2010). Microtrial methods for translating gene-environment dynamics into preventive interventions. Prevention Science, 11(4), 343–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-010-0177-2

- Howe, G. W., & Ridenour, T. A. (2019). Bridging the gap: Microtrials and idiographic designs for translating basic science into effective prevention of substance use. In Z. Sloboda, H. Petras, E. Robertson, & R. Hingson (Eds.). Prevention of substance use. Advances in prevention science. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00627-3_22

- Kazdin, A. E. (2019). Single-case experimental designs. Evaluating interventions in research and clinical practice. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 117, 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.015

- Kirova, A.-M., Kelberman, C., Storch, B., DiSalvo, M., Woodworth, K. Y., Faraone, S. V., & Biederman, J. (2019). Are subsyndromal manifestations of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder morbid in children? A systematic qualitative review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 274, 75–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.003

- Koomen, H. M., Verschueren, K., Van Schooten, E., Jak, S., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Validating the student-teacher relationship scale: Testing factor structure and measurement invariance across child gender and age in a Dutch sample. Journal of School Psychology, 50(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.09.001

- Langberg, J. M., Dvorsky, M. R., & Evans, S. W. (2013). What specific facets of executive function are associated with academic functioning in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(7), 1145–1159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9750-z

- Leijten, P., Dishion, T. J., Thomaes, S., Raaijmakers, M. A., Orobio de Castro, B., & Matthys, W. (2015). Bringing parenting interventions back to the future: How randomized microtrials may benefit parenting intervention efficacy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 22(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12087

- Lundahl, B., Risser, H. J., & Lovejoy, M. C. (2006). A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 86–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004

- Maurice-Stam, H., Haverman, L., Splinter, A., van Oers, H., Schepers, S., & Grootenhuis, M. (2018). Dutch norms for the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)–parent form for children aged 2–18 years. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0948-1

- McMahon, R., & Forehand, R. (2003). Helping the noncompliant child: A clinician’s guide to effective parent training. Guilford.

- Miller, F. G., & Fabiano, G. A. (2017). Direct behavior ratings: A feasible and effective progress monitoring approach for social and behavioral interventions. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 43(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508417733454

- Miller, F. G., & Lee, D. L. (2013). Do functional behavioral assessments improve intervention effectiveness for students diagnosed with ADHD? A single-subject meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22(3), 253–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-013-9174-4

- Moher, D., Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., & Group, C. (2001). The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Elsevier.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2018) . Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. British Psychological Society.

- Northup, J., Fusilier, I., Swanson, V., Huete, J., Bruce, T., Freeland, J., … Edwards, S. (1999). Further analysis of the separate and interactive effects of methylphenidate and common classroom contingencies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1999.32-35

- Oosterlaan, J., Scheres, A., Antrop, I., Roeyers, H., & Sergeant, J. (2008). Vragenlijst voor Gedragsproblemen bij Kinderen van 6 tot en met 16 jaar: Handleiding [Questionnaire on behavioral problems in children aged 6-16]. Hartcourt Publishers.

- Owens, J. S., Holdaway, A. S., Smith, J., Evans, S. W., Himawan, L. K., Coles, E. K., … Dawson, A. E. (2018). Rates of common classroom behavior management strategies and their associations with challenging student behavior in elementary school. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 26(3), 156–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426617712501

- Pelham, W. E., Jr, & Fabiano, G. A. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 184–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701818681

- Pelham, W. E., Jr, Gnagy, E. M., Greenslade, K. E., & Milich, R. (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(2), 210–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006

- Pfiffner, L. J., & DuPaul, G. J. (2015). Treatment of ADHD in school settings. In R. A. Barkley (Ed), Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (pp. 596–629). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Pianta, R. C. (2001). Student–teacher relationship scale–short form. Psycho-logical Assessment Resources.

- Polanczyk, G., De Lima, M. S., Horta, B. L., Biederman, J., & Rohde, L. A. (2007). The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 942–948. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942

- Polanczyk, G., Willcutt, E., Salum, G., Kieling, C., & Rohde, L. (2014). ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 434–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt261

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures Package, 61(52), 18.

- Rosnow, R. L., & Rosenthal, R. (1996). Computing contrasts, effect sizes, and counternulls on other people’s published data: General procedures for research consumers. Psychological Methods, 1(4), 331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.4.331

- Ross, S. W., Romer, N., & Horner, R. H. (2012). Teacher well-being and the implementation of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(2), 118–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300711413820

- Sattler, J. M. (2008). Resource guide to accompany assessment of children: Cognitive foundations. JM Sattler.

- Schatz, N. K., Aloe, A. M., Fabiano, G. A., Pelham, W. E., Jr, Smyth, A., Zhao, X., … Hong, N. (2020). Psychosocial Interventions for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Systematic Review with Evidence and Gap Maps. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 41, S77–S87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000778

- Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., & Hufford, M. R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415

- Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Brandeis, D., Cortese, S., Daley, D., Ferrin, M., Holtmann, M., … Döpfner, M. (2013). Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070991

- Sutherland, K. S., Wehby, J. H., & Yoder, P. J. (2002). Examination of the relationship between teacher praise and opportunities for students with EBD to respond to academic requests. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/106342660201000102

- Tannock, R., Hum, M., Masellis, M., Humphries, T., & Schachar, R. (2002). Teacher telephone interview for children’s academic performance, attention, behavior and learning: DSM-IV Version (TTI-IV). The Hospital for Sick Children.

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

- van den Hoofdakker, B. J., Van der Veen-mulders, L., Sytema, S., Emmelkamp, P. M., Minderaa, R. B., & Nauta, M. H. (2007). Effectiveness of behavioral parent training for children with ADHD in routine clinical practice: A randomized controlled study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(10), 1263–1271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3181354bc2

- Vancraeyveldt, C., Verschueren, K., Wouters, S., Van Craeyevelt, S., Van den Noortgate, W., & Colpin, H. (2015). Improving teacher-child relationship quality and teacher-rated behavioral adjustment amongst externalizing preschoolers: Effects of a two-component intervention. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(2), 243–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9892-7

- Veenman, B., Luman, M., Hoeksma, J., Pieterse, K., & Oosterlaan, J. (2016). A randomized effectiveness trial of a behavioral teacher program targeting ADHD symptoms. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716658124

- Wechsler, D., Kort, W., & Compaan, E. (2005). WISC-III NL. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. Derde editie NL. Handleiding en Verantwoording. The Psychological Corporation/Nederlands Dienstencentrum NIP.

- Wilens, T. E., Biederman, J., Brown, S., Tanguay, S., Monuteaux, M. C., Blake, C., & Spencer, T. J. (2002). Psychiatric comorbidity and functioning in clinically referred preschool children and school-age youths with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(3), 262–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200203000-00005

- Williford, A. P., Wolcott, C. S., Whittaker, J. V., & Locasale-Crouch, J. (2015). Program and teacher characteristics predicting the implementation of Banking Time with preschoolers who display disruptive behaviors. Prevention Science, 16(8), 1054–1063. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0544-0