ABSTRACT

Nearly half of children meeting criteria for a mental health disorder in the United States (U.S.) do not receive the treatment they need. Unfortunately, lack of access to and engagement in mental health services can be seen at even higher rates for historically marginalized groups, including low-income, racial, and ethnic minority youth. Lay Health Workers (LHWs) represent a valuable workforce that has been identified as a promising solution to address mental health disparities. LHWs are individuals without formal mental health training who oftentimes share lived experiences with the communities that they serve. A growing body of research has supported the mobilization of LHWs to address service disparities around the globe; however, challenges persist in how to scale-up and sustain LHW models of care, with specific barriers in the U.S. In this paper, we describe LHWs’ different roles and involvement in the mental health field as well as the current state of the literature around LHW implementation. We integrate the RE-AIM Framework with a conceptual model of how LHWs address disparities to outline future directions in research and practice to enhance equity in the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of LHW models of care and evidence-based practices for historically marginalized communities within the U.S.

In the United States (U.S.), 49.4% of children who meet criteria for a mental health disorder do not receive treatment, which is an estimated 7.7 million children in need of service (Whitney & Peterson, Citation2019). These disparities are more prevalent based on the geographic region where a child lives, their race/ethnicity, and immigration status (Alegria et al., Citation2010; Coker et al., Citation2009; NeMoyer et al., Citation2020; Whitney & Peterson, Citation2019). Mental health disparities have been exacerbated by COVID-19 as racial and ethnic minority communities were more likely to experience infection, loss of a loved one, discrimination, unemployment, and poverty during the pandemic due to structural inequities (Condon et al., Citation2020; Purtle, Citation2020). In order to increase equity in access to mental health services, a public health model of workforce development is needed, especially to address the widespread impact of the pandemic (Barnett, Lau et al., Citation2018; Kazdin & Rabbitt, Citation2013; Peretz et al., Citation2020).

Lay health workers (LHWs) have been identified as an innovative workforce solution to enhance equity in care (Barnett, Lau, et al., Citation2018). LHWs go by a range of terms (e.g., community health workers, family navigators, peer providers, promotoras) and broadly include nonprofessional providers, who have shared lived experiences with the individuals they serve (Gustafson et al., Citation2018; Jack et al., Citation2020). These lived experiences include having similar clinical diagnoses or family experiences (e.g., peer providers, parent partners) or being from the same community with similar cultural backgrounds (e.g., community health workers, promotoras). Traditionally, LHWs were involved in the prevention and treatment of physical diseases, such as HIV, cancer, heart disease, and diabetes (Ayala et al., Citation2010; Katigbak et al., Citation2015; Landers & Levinson, Citation2016; Rhodes et al., Citation2007). LHW-delivered services have been associated with improved health outcomes, cost-savings to healthcare systems, and decreased health disparities (Kangovi et al., Citation2020; Landers & Levinson, Citation2016). During the COVID-19 pandemic, LHWs were identified as having a critical role in community outreach, contact tracing, and addressing social determinants of health (Peretz et al., Citation2020; Rahman et al., Citation2021). In fact, the American Rescue Plan invested $330 million in LHW services to support COVID-19 prevention and control, including conducting outreach for vaccine efforts.

Given these successes within physical health, the roles of LHWs within mental health services has received increasing attention in the past decade (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2018). The World Health Organization’s Mental Health Gap Action Programme identified the role LHWs could have to increase evidence-based practices (EBPs) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where there are extreme shortages in professional mental health providers (Dua et al., Citation2011; Keynejad et al., Citation2021). For this reason, the majority of research on LHW delivery of EBPs has been conducted in LMICs (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2018; Singla et al., Citation2017). However, the workforce shortages and rates of mental health services access among certain groups in the U.S., including immigrants, is equivalent to rates seen in LMICs (Derr, Citation2016; Whitney & Peterson, Citation2019). Therefore, increasing attention is being placed on how LHWs can increase service equity for racial and ethnic minority communities in the U.S. (Barnett, Lau, et al., Citation2018; Kazdin & Rabbitt, Citation2013). There are rich opportunities for mutual capacity building across LMICs and high-income countries about how to scale-up LHW-delivered mental health services to address disparities in low-resource settings (Jack et al., Citation2020).

LHW Models of Care

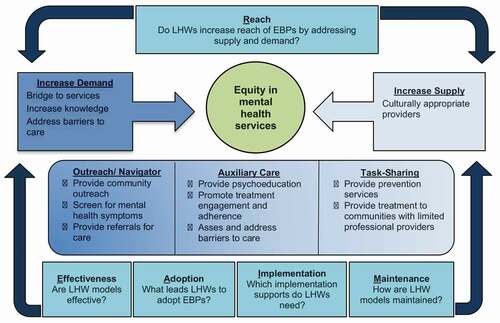

A recently developed conceptual model illustrates how LHWs address drivers of disparities, which are associated with both the supply of providers equipped to deliver EBPs and the demand for these interventions within marginalized communities depending on the roles that they take within mental health service provision (Barnett, Lau, et al., Citation2018). LHWs serve as providers when there is an inadequate supply of professionals to deliver services. Demand for EBPs is impacted by LHWs supporting an individual’s mental health literacy, stigma toward mental illness and help seeking, perceptions of treatment providers, and culturally based beliefs and preferences. These supply and demand drivers of disparities are linked to systems that have marginalized and oppressed racial and ethnic communities, and excluded them from receiving high-quality care. For example, undocumented immigrants are especially unlikely to seek mental health services due to fear of being reported to authorities (Philbin et al., Citation2018). Since LHWs come from similar cultural and personal backgrounds as the individuals they serve, they may be especially adept at helping patients overcome distrust of health systems (Katigbak et al., Citation2015). Different LHW models of care are outlined below and in to highlight how these roles impact supply of and demand for mental health services.

Table 1. LHW models of care

Navigation Models of Care

LHWs in the U.S. frequently have the role to be a “bridge to services” or navigator (Ayala et al., Citation2010; Barnett, Lau, et al., Citation2018). By conducting outreach, providing referrals, and supporting enrollment in services, LHWs in a navigator or bridge role are focused on addressing disparities that emerge due to limited demand for services. The title and specific tasks involved in the role are determined based on whether the LHWs are embedded within healthcare teams or part of community networks (Olaniran et al., Citation2017). LHWs often are volunteers or contracted employees within community-based, grassroots networks, which offer training and coordinate projects with other service sectors (Klein et al., Citation2020). Qualitative interviews with Latina LHWs from a community-based, grassroots network highlighted their central role of acting as a bridge to services by conducting outreach and providing information (Barnett et al., Citationunder review).

When LHWs are embedded within healthcare systems they are frequently referred to as navigators, including patient navigators, wellness navigators, or family navigators (Broder-Fingert, Stadnick, et al., Citation2019). Family navigation is an example of an evidence-based navigation model that is focused on reducing racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities by eliminating barriers to care, in an effort to improve access to health services (Ali-Faisal et al., Citation2017; Broder-Fingert, Stadnick, et al., Citation2019). Similar to many LHW models of care, the evidence-base for navigation was originally focused on physical health, but has been expanded to behavioral health needs, including receiving a timely diagnosis for autism spectrum disorder (Broder-Fingert et al., Citation2018) and therapy services for maternal depression (Silverstein et al., Citation2018). Family navigation is similar to patient navigation, but is unique in its role in the LHW space in its focus on the family (instead of the individual) as the unit of care (Wells et al., Citation2008). Family navigation is based in the Chronic Care Model, which is an evidence-based model for chronic care that promotes interactions between an informed, activated patient and a prepared, proactive practice team (Bodenheimer et al., Citation2002). Navigation is particularly valuable in situations where families must interact with complex systems of care (Broder-Fingert, Qin, et al., Citation2019). For example, a recent study found that family navigation improves access to services for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), specifically decreasing the time from an initial positive screen to formal diagnosis (Feinberg et al., Citation2021). However, findings varied across site, suggesting differences in implementation that might lead to the success of the program. Additional trials are ongoing to test the impact of family navigation on access to services in a number of other disorders and to address exposure to childhood adversity (Ali-Faisal et al., Citation2017; Barnett et al., Citation2021; Broder-Fingert et al., Citation2019).

Auxiliary Care

LHWs can also provide auxiliary services, such as case management and promotion of treatment-related behaviors, in collaboration with professional mental health providers. Supply and demand for EBPs can be impacted by the auxiliary care model. Given high rates of dropout, especially early in treatment or before treatment begins, LHWs in auxiliary roles might help more families engage in and persist in care. This could have an impact on the supply of treatment as well, as professional providers may be able to successfully treat more families if engagement (e.g., attendance, adherence to home practice) increases with auxiliary services and LHWs are able to share the burden of delivering engagement strategies (e.g., providing psychoeducation, phone call reminders). A systematic review of evidence-based engagement practice elements identified matching clients with peer providers (i.e., LHWs) as a way to improve engagement, but did not highlight the techniques these LHWs use to do so (Becker et al., Citation2018). While the majority of the other identified engagement practice elements (e.g., assessment, psychoeducation) were delivered by professional providers or trainees, it is important to identify if peers (i.e., LHWs) use these evidence-based techniques or different ones that promote engagement. Recent qualitative studies have investigated the strategies LHWs identify as critical for engaging caregivers of youth clients (Barnett et al., Citationunder review; Gustafson et al., Citation2021). LHWs highlighted the importance of leveraging their social proximity as a central engagement strategy, which differs from techniques used by professional providers (Gustafson et al., Citation2018; Gustafson et al., Citation2021). Many of the other techniques that were discussed seem consistent with evidence-based practice elements outlined by Becker et al. (Citation2018), including building rapport, identifying, and addressing barriers, and enhancing motivation (Barnett et al., Citationunder review; Gustafson et al., Citation2021). Auxiliary care models that emphasize training LHWs in evidence-based engagement strategies may support professional providers, in that they are able to focus on delivering EBPs, whereas the LHWs can help families address barriers and gain motivation for treatment.

In one example of an auxiliary model, LHWs have been trained to increase engagement in Parent–Child Interaction Therapy by addressing barriers to care and promoting home practice of skills (Barnett et al., Citation2016, Citation2019). More broadly across mental health services, the Parent Empowerment Program trains family peer advocates to work with parents to address their children’s mental health needs and overcome barriers to care (Hoagwood et al., Citation2018; Rodriguez et al., Citation2011). Limited evidence has established the success of these auxiliary models. One trial of the Parent Empowerment Program, found caregivers of children with autism reported lower stress than caregivers who received treatment as usual, but there were no differences in service utilization (Jamison et al., Citation2017).

Task-Sharing

The majority of research with LHWs has investigated if they can effectively deliver EBPs, which is intended to increase the supply of providers in settings with a limited mental health workforce (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2018). Task-sharing ranges from LHWs delivering interventions to low-severity cases and referring to higher severity cases to professional providers in stepped-care models, to serving as the primary providers responsible for all treatment delivery. For example, research within adult mental health has documented LHWs helped reduced the prevalence of mental health conditions among patients within a collaborative stepped-care model in India. The researchers trained LHWs to act as case managers, provide psychoeducation on a variety of topics (e.g., mental health conditions, treatment adherence), provide referrals as needed, and provide short-term interpersonal psychotherapy to participants who had moderate-to-severe symptoms (Patel et al., Citation2010). In this collaborative stepped-care model, prevalence rates of common mental health disorders decreased between 24 and 57% across the four groups over a 12-month period for patients receiving services in public facilities. More specifically, the researchers reported a 36–45% reduction in depressive symptoms including suicide plans or attempts (Patel et al., Citation2011). Given these successes, a stepped-care model was recently adapted for adolescents in India (Chorpita et al., Citation2020). Additionally, LHWs have been trained to be the primary providers of EBPs in LMICs, including parent management training (Puffer et al., Citation2015), trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) for traumatic stress in children (Dorsey et al., Citation2020), and modular transdiagnostic treatments for anxiety, depression and trauma in adults (Bolton et al., Citation2014; Murray et al., Citation2014).

Future Directions

We described how different LHW models of care have the potential to improve the supply and demand of mental health services for marginalized populations, which hopefully increases access to care, the cultural fit of EBPs, and engagement in services. However, limited research has identified if LHW models actually instill greater equity in service access, utilization, and quality for marginalized populations (McCollum et al., Citation2016). Equity means that there are fair opportunities to access services that promote health and wellbeing, with special attention to the needs of those who are at greater risk of poor health due to their social condition (Braveman, Citation2014; Woodward et al., Citation2019). Though research on LHW programs shows the potential for increasing access to high-quality mental health treatment, additional research is needed to see their larger public health impact in doing so. Additionally, it is critical to acknowledge ways in which LHWs, who belong to the same communities they are serving, may be marginalized within research or practice. LHWs often face policies that lead to unequal compensation, training and supervision, or integration into treatment teams (Flores et al., Citation2021; Klein et al., Citation2020; Olaniran et al., Citation2017). If equity for LHWs is not central to the planning and design of studies (e.g., how LHWs will be compensated for their efforts), research and practices can reinforce structural racism experienced by LHWs (Klein et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the future directions we recommend focus on enhancing equity for the families served and the LHWs providing the care (Baumann & Cabassa, Citation2020). These future direction recommendations will be on how LHWs are mobilized in mental health within the U.S. for populations that face systemic discrimination leading to mental health disparities. However, they will be informed by research with LHWs in LMICs, given the rich lessons that can be learned about how to increase access to EBPs within low-resource settings from these efforts (Jack et al., Citation2020).

To outline future directions for LHW research within the field of children’s mental health, we incorporated the conceptual model of how LHWs reduce disparities (Barnett, Lau et al., Citation2018) with the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework (Glasgow et al., Citation1999; Shelton et al., Citation2020), as shown in . The original Barnett et al. (Citation2018) conceptual model illustrated how LHWs address reach of EBPs by increasing supply and demand for services through navigation, auxiliary support, and task sharing. To inform future directions, we integrated a recently updated version of RE-AIM, which focuses on how to measure and address equity in reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of EBPs (Shelton et al., Citation2020). RE-AIM is a widely adopted implementation framework developed to address the research-to-practice gap that limits the public health impact of EBPs and the reduction of health inequities (Glasgow et al., Citation1999). Individual, provider, and setting-level dimensions are addressed by RE-AIM. Reach and effectiveness address whether individuals receive an EBP (reach) and if it works for individuals (effectiveness). Adoption, implementation, and maintenance refer how providers and settings take-up, deliver, and continue using an EBP (Shelton et al., Citation2020)

Figure 1. Integration of RE-AIM with LHW models of care to enhance equity

Reach: Do LHWs Increase Reach of EBPs by Addressing Supply and Demand?

One of the primary goals of LHW models of care is to increase the reach of mental health treatments, by increasing the demand for care with navigator models or supply of providers with task-sharing (Barnett, Lau et al., Citation2018). In RE-AIM, reach is defined as the number of eligible individuals who receive an EBP divided by the number of eligible individuals (Glasgow et al., Citation1999). Though the intention of EBP implementation is often to improve access to high-quality mental health services for marginalized populations, inequities might be exacerbated if EBPs only reach more advantaged populations and marginalized populations receive lower quality care (Stadnick et al., Citation2020). Therefore, a recent extension of RE-AIM suggested research identify if populations are equitably reached when an EBP is implemented, identifying reasons why they are not being reached if that is the case, and finally develop solutions to reach those experiencing inequities (Shelton et al., Citation2020). While LHWs have been identified as an important workforce to increase reach, minimal research has identified: 1) to what extent equity in reach is achieved by incorporating LHWs into EBP delivery in children’s mental health services, and 2) the LHW roles that facilitate equity in reach. As outlined above, LHWs can increase reach by increasing both the number of families that seek and persist in treatment, and the number of culturally appropriate providers who deliver it.

Research is needed to guide how to appropriately match LHW roles to local capacity for mental health services to maximize reach. If an LHW model of care is adopted that does not match the concerns regarding supply or demand for services, it is unlikely to impact equity in reach. For example, data from our team has shown that in a navigator/bridge role, LHWs can successfully link families to autism assessments and mental health services through making referrals and supporting access to specialist care (Barnett, Kia-Keating, et al., Citation2020; Feinberg et al., Citation2021). However, this could have a negative impact on the clinics that receive these referrals if it leads to longer waitlists. This may be especially challenging for non-English-speaking clients, as there is a dearth of linguistically appropriate providers in many settings, which impacts access to care (Ohtani et al., Citation2015). Indeed, in one of our community partnered projects, mental health agency leaders indicated a preference that LHWs not conduct outreach due to the length of the waitlist for Spanish-speaking clients. At the same time, LHWs expressed concerns that families in their communities were not accessing adequate treatment because they did not know about the services or were deterred by these long waits. This example points to the necessity of moving beyond an intervention focused approach to a systems thinking approach when planning for the role of LHWs within children’s mental health services (Javadi et al., Citation2017). An intervention approach might include a trial of whether LHWs are able to provide an EBP and have positive clinical outcomes, whereas a systems approach would focus on how different parts of a complex system need to work together to guarantee that LHWs have appropriate training, supervision, integration within the treatment team, payment for services, and buy-in from various stakeholder (e.g., clients, mental health professionals, agency leaders).

A systems approach often employs methodology from systems science (e.g., simulation modeling or systems dynamics theory), which help to capture the wider system implications of implementing interventions or policies (Luke & Stamatakis, Citation2012). According to the National Institute of Health (NIH, Citation2020), “Systems science considers different components within complex systems across multiple levels to help understand their interactions and influences.” For example, simulation modeling can be used to predict how an intervention, such as behavioral health screening or navigation services, could increase the supply or demand for services, and how that might impact the mental health workforce (Barnett et al., Citation2021). It has been recommended that simulation modeling and systems science help to guide how research, policy, and practice can be leveraged to address health disparities (NIH, Citation2020). Furthermore, simulation modeling has been proposed as an implementation strategy, in that it can guide planning among stakeholders about their assumptions about how a new innovation will impact the supply and demand of an intervention (Sheldrick et al., Citation2021). This may be an especially fitting approach to identify appropriate roles for LHWs to increase access to EBPs in low-resource settings, in that models can be developed to identify whether LHWs are needed to address supply or demand issues that are driving disparities (Barnett, Lau, et al., Citation2018; McCollum et al., Citation2016). As illustrated in , stakeholders may want to determine if outreach is needed to increase knowledge about the availability of an EBP or if equity is being inhibited by the lack of a workforce, in which case task-sharing may be the appropriate model of care to increase access to services. Future research using simulation modeling can identify if this implementation strategy improves equity in reach by helping systems determine the LHW model that is the best fit for their needs.

Effectiveness: Are LHW Models of Care Effective?

In addition to investigating impacts on reach, examining the efficacy and effectiveness of LHW-delivered services is paramount to increase equity in the quality of mental health services. Within the RE-AIM framework, evaluations of effectiveness should include clinical outcomes, quality of life indicators, behavior changes, and if there are negative outcomes from the intervention (Glasgow et al., Citation1999). Further, it is important to evaluate if there are differences in EBP effectiveness across groups (Shelton et al., Citation2020). Overall, research evaluating efficacy and effectiveness of LHW delivered interventions remains limited in the U.S. (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2018; Hoagwood et al., Citation2010). However, drawing from research with LHWs in LMICs, accumulating evidence shows that LHWs can deliver EBPs as primary providers with fidelity and positive clinical outcomes (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2018; Singla et al., Citation2017). For example, a randomized-control trial in Kenya and Tanzania tested LHW-delivered trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy (TF-CBT) in comparison to usual care for children who had lost a parent. Children who received TF-CBT showed greater improvements in post-traumatic stress than those who received usual care, and some maintained those improvements 1 year later (Dorsey et al., Citation2020). This example may be especially relevant following the COVID-19 pandemic, in which roughly 40,000 children in the U.S. lost at least one parent (Kidman et al., Citation2021). At the same time, state regulations and TF-CBT training guidelines limit the provisions of this EBP to professional mental health providers in the U.S. (Barnett, Lau, et al., Citation2018).

Though findings from LMICs are promising on LHW-delivered EBPs, minimal research has investigated if there are differences in clinical outcomes depending on provider experience and education level (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., Citation2018). One recent study found similar levels of fidelity and effectiveness between LHW and professional delivery of a perinatal depression preventive intervention (Diebold et al., Citation2020; Tandon et al., Citation2021), but few other studies have made these comparisons. If LHWs are less effective at delivering EBPs than mental health professionals or their roles in auxiliary care diminishes effectiveness, disparities could be exacerbated for marginalized populations. That is to say, marginalized populations would not have equitable access to the same quality of services. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that improving access to mental health care among marginalized communities requires new service delivery models and may occur in multiple manners (Kazdin & Rabbitt, Citation2013). Indeed, the benefit of increasing access to more individuals may warrant small decreases in effectiveness. Specifically, it has been suggested that LHWs could increase access to prevention services for children and families with less clinical severity (Acevedo-Polakovich et al., Citation2013). Kaplan (Citation2000) highlighted the major role that prevention efforts can play in ameliorating population-level health outcomes. This would translate into creating meaningful impact (e.g., increasing access) on less severe conditions (e.g., subclinical presentations) among the larger population (Kaplan, Citation2000). While the effectiveness of LHW-delivered prevention services has been explored to some extent (Kia-Keating et al., Citation2017; Williamson et al., Citation2014), further research is warranted in this area. Future research that evaluates differences in how LHWs and professionals impact access, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of EBPs could help inform the types of practices and levels of care that are best suited to LHWs. Beyond clinical trials, benchmarking studies and meta-analyses could help illuminate if there are differences in clinical outcomes based on who provides prevention or intervention services, in order to best match individuals to providers who can meet their needs.

Research is also needed to identify if there are additional benefits to auxiliary models of care. This is especially warranted given some evidence that auxiliary services, while designed to augment interventions, could decrease effectiveness (Kaminski et al., Citation2008). For example, adding additional services (e.g., case management, individual parent therapy) to Parent–Child Interaction Therapy for child welfare families did not enhance effectiveness, and in fact had slightly higher rates of re-reported child abuse than families that received the standard intervention (Chaffin et al., Citation2004). It could be that adding elements to interventions has the risk of saturating families’ capacity to continue to engage or weaken the quality of services delivered. In sum, future research in the effectiveness of LHW involvement needs to take a perspective of establishing the effectiveness of different roles for LHWs.

Adoption: What Leads LHWs to Adopt EBPs?

Adoption refers to the number, proportion, and representativeness of settings and providers that decide to deliver a program or EBP in RE-AIM (Glasgow et al., Citation1999). It is important for research to identify what facilitates LHWs adopting evidence-based strategies in the services they deliver. As has been highlighted, we know that LHWs can be trained to deliver EBPs with fidelity from efforts in LMICs (Barnett, Gonzlez, et al., Citation2018; Singla et al., Citation2017); however, their roles in the U.S. may impact adoption of these interventions. For example, it has been noted that peer providers in the U.S. typically focus more on sharing lived experiences and providing support, with more formal interventions being seen as outside of the scope of their job description (Magidson et al., Citation2019). Relatedly, the systems they work within will impact if they have the job flexibility, supervision, and support to adopt EBPs. Therefore, as with other areas of implementation science, investigations of policy and agency-leadership factors that lead to adoption of evidence-based LHW models of care are needed (Aarons et al., Citation2016, Citation2011).

Methodologies such as human-centered design and community-based participatory research, which emphasize engagement with stakeholders to develop solutions to problems identified within the community, are recommended approaches to enhance the acceptability and feasibility of interventions to enhance adoption and eventually sustainment (Kia-Keating et al., Citation2017; Triplett et al., Citation2021). For example, LHWs in Chicago schools were trained to deliver an evidence-based parenting program, but engagement remained low, as very few parents attended the traditional parenting groups. Therefore, the program was refined in collaboration with input from the LHWs to fit with their ability to have frequent and informal contacts with parents to teach strategies to improve behaviors and academic performance (Mehta et al., Citation2019). By co-designing with LHWs, EBPs can be designed to be feasibly delivered and appropriate for the needs of the community. This is especially important, as few EBPs were designed for or evaluated with racial and ethnic minority groups (Miranda et al., Citation2005).

As having common lived experience is hypothesized as being critical for LHWs, it is also important to understand what areas of shared experiences and identities support adoption of interventions. Applying an intersectionality lens, which focuses how an individual’s multiple identities, including race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability, socioeconomic status, age, interact with social systems, is needed when designing, implementing, and evaluating LHW programs (Heard et al., Citation2020). Two examples from our team highlight the importance of applying intersectionality theory to future work with LHWs. One study sought to increase engagement in evidence-based parenting programs for Latinx parents. Latina LHWs identified challenges they faced in engaging fathers within their community. Though they expressed positive attitudes toward father involvement, they noted challenges they faced, especially as women given rigid gender roles within the Latinx community (Gonzalez et al., Citationunder review). Our other study has included formative work with LHWs, youth, and parents to adapt family navigation to support the mental health needs for sexual and gender minority youth. In this project, discussions with community stakeholders have centered on the impact of intersecting identities related to cultural perceptions of gender, sexuality, and parenting. Both of these examples point to important areas that need to be addressed. First, when adopting an LHW model of care, it will be important to identify which aspects of an LHW’s identity are hypothesized as necessary to be able to meet the needs of those being served. Secondly, as it is unlikely that LHWs share all aspects of identity with the individuals they serve, it is important to identify the training and supports they need to adopt and successfully deliver EBPs with different lives experiences from themselves.

Implementation: Which Implementation Supports Do LHWs Need?

Implementation refers to the consistent delivery of an EBP, including the strategies (e.g., training, supervision) that are needed to support delivering the EBP with fidelity (Shelton et al., Citation2020). Multi-site trials of LHW models of care consistently find differences across sites, suggesting differences in implementation that need to be understood (Dorsey et al., Citation2020; Feinberg et al., Citation2021; Patel et al., Citation2010). In order to study implementation, it is important to understand what high fidelity delivery of LHW delivered interventions is. Though fidelity may be defined for structured EBPs used within the task-sharing, it is less clear for other LHW models of care, though efforts have been made to identify core components of family navigation (Broder-Fingert, Stadnick, et al., Citation2019). Therefore, additional research is needed to categorize the mechanisms of change that lead to successful implementation for navigator and auxiliary models.

Additionally, it is critical to understand the implementation strategies that are needed to support LHWs in high-quality service delivery. LHWs have identified a need for training and supervision to support their work with families and communities (Klein et al., Citation2020). In LHW models of care, implementation is often overseen or evaluated by clinical psychologists, who provide training and ongoing supervision (Barnett, Lau et al., Citation2018; Magidson et al., Citation2019). At the same time, psychologists providing training or supervision need to engage in cultural humility and embrace the importance of shared knowledge and skills (Mundeva et al., Citation2018). Thus, it is vital to value the expertise LHWs have in identifying and addressing mental health service utilization barriers within their communities. Indeed, qualitative studies with LHWs have demonstrated that they employ a number of engagement strategies to increase the accessibility and acceptability of services without formalized trainings on how to do so (Barnett et al., Citationunder review; Gustafson et al., Citation2021). Therefore, research is need that identifies the areas of training that are most important for LHWs in working with children and families – it may not be in how to engage members of their communities, but instead ways to address clinical challenges that arise in their interactions with families.

Maintenance: How are LHW Models of Care Maintained?

Maintenance and sustainment refer to the extent to which EBPs become embedded within communities or organizations and continue to be delivered with fidelity and positive clinical outcomes (Shelton et al., Citation2020). For quality implementation, it is critical to focus on what leads LHWs to deliver interventions with fidelity after the initial trial concludes. In many clinical trials in LMICs, LHWs have received a high level of training and supervision from experts from the U.S., which can be resource intensive and limit the ability to sustain the models over time (Barnett, Lau, et al., Citation2018). Recently, efforts have been made to train LHWs with extensive experience in EBPs to become local supervisors (Dorsey et al., Citation2020; Murray et al., Citation2011). Further research is needed to identify sustainable supervision models for LHWs in the U.S. and other low-resource settings.

Sustainment of LHW models of care remains limited due to challenges financing their services beyond the duration of a grant or philanthropic efforts. Future research and policy efforts should focus on identifying financing strategies that increase the sustainment of LHWs as a workforce. Financing strategies include credentialing providers, fee-for-service reimbursements, and bundled payment (Dopp et al., Citation2020). Efforts have been made to develop credentials for LHWs, such as parent support partners in New York State, which allows them to bill for services (Horwitz et al., Citation2020). Others have proposed bundled payments, which focus on quality rather than quantity care within a system as a way to cover LHW salary and benefits (Srivastav et al., Citation2017). Research on financing strategies for LHWs likely requires a team science approach, with expertise from implementation science, health services, and health economics (Barnett, Dopp, et al., Citation2020). This area of research is urgent because without financing solutions, it is unlikely that LHW models of care will be able to adopted and sustained to a level that impacts public health.

Sustainment is also impacted by turnover, which can be related to burnout and job satisfaction (Kim et al., Citation2018). LHWs may experience higher risk for burnout without appropriate supports, as they have many of the same experiences as the families they are serving, including poverty, exposure to traumatic events (e.g., community violence), and discrimination (Jacobs et al., Citation2017). LHWs have identified motivation for and positive effects of helping their communities, but at the same time recognize the need training and supervision to promote feelings of self-efficacy and decrease burnout (Shelton et al., Citation2017; Wall et al., Citation2020). Training and supervision in structured EBPs have been proposed as strategies to decrease burnout in LHWs, because it provides them with tools to address challenges that may arise with their clients (Aarons et al., Citation2009). Future research can continue to identify the impact of different implementation strategies and organizational factors that promote ongoing job satisfaction in LHWs.

Conclusions

As outlined in this article, LHWs have the potential to address mental health disparities as trusted members of the communities they serve. However, research and practice with LHWs must center equity to make sure that care actually is improved and systems honor their roles and contributions (Klein et al., Citation2020). Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of structural racism on individual’s health, safety, and mental well-being was laid bare, highlighting the need to redesign our systems of care (Liu & Modir, Citation2020; Stewart et al., Citation2021). We believe that LHWs are one important component of this redesign, which requires significant investment in mental health infrastructure (Stewart et al., Citation2021). We are not naïve to think that LHWs should be tasked with taking on the pervasive inequities within our society, especially when they are often marginalized within the systems where they work. However, as providers with insights into the problems faced by the most marginalized communities, LHW voices should be central to helping to design, implement, and evaluate solutions to promote mental health equity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the lay health workers, who have contributed to our research. Their insights and contributions have strengthened our understanding of future directions that can help promote mental health equity.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarons, G. A., Fettes, D. L., Flores, L. E., & Sommerfeld, D. H. (2009). Evidence-based practice implementation and staff emotional exhaustion in children’s services. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(11), 954–960. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.006

- Aarons, G. A., Green, A. E., Trott, E., Willging, C. E., Torres, E. M., Ehrhart, M. G., & Roesch, S. C. (2016). The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: A mixed-method study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 991–1008. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0751-4

- Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

- Acevedo-Polakovich, I. D., Niec, L. N., Barnett, M. L., & Bell, K. M. (2013). Incorporating natural helpers to address service disparities for young children with conduct problems. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(9), 1463–1467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.06.003

- Alegria, M., Vallas, M., & Pumariega, A. (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(4), 759–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001

- Ali-Faisal, S. F., Colella, T. J. F., Medina-Jaudes, N., & Benz Scott, L. (2017). The effectiveness of patient navigation to improve healthcare utilization outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(3), 436–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.014

- Ayala, G., Vaz, L., Earp, J., & Elder, J. (2010). Outcome effectiveness of the lay health advisor model among Latinos in the United States: An examination by role. Health Education, 25(5), 815–840. https://academic.oup.com/her/article-abstract/25/5/815/567914

- Barnett, M. L., Davis, E. M., Callejas, L. M., White, J. V., Acevedo-Polakovich, I. D., Niec, L. N., & Jent, J. F. (2016). The development and evaluation of a natural helpers’ training program to increase the engagement of urban, Latina/o families in parent-child interaction therapy. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 17–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.016

- Barnett, M. L., Dopp, A. R., Klein, C., Ettner, S. L., Powell, B. J., & Saldana, L. (2020). Collaborating with health economists to advance implementation science: A qualitative study. Implementation Science Communications, 1(1), 82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-020-00074-w

- Barnett, M. L., Gonzalez, A., Miranda, J., Chavira, D. A., & Lau, A. S. (2018). Mobilizing community health workers to address mental health disparities for underserved populations: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(2), 195–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-017-0815-0

- Barnett, M. L., Kia-Keating, M., Ruth, A., & Garcia, M. (2020). Promoting equity and resilience: Wellness navigators’ role in addressing adverse childhood experiences. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 8(2), 176–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000320

- Barnett, M. L., Klein, C., Gonzalez, J. C., Luis Sanchez, B. E., Green Rosas, Y., & Corcoran, F. (under review). How do lay health workers engage caregivers? A qualitative study to enhance equity in evidence-based parenting programs. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

- Barnett, M. L., Lau, A. S., & Miranda, J. (2018). Lay health worker involvement in evidence-based treatment delivery: A conceptual model to address disparities in care. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14(1), 185–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084825

- Barnett, M. L., Miranda, J., Kia-Keating, M., Saldana, L., Landsverk, J., & Lau, A. S. (2019). Developing and evaluating a lay health worker delivered implementation intervention to decrease engagement disparities in behavioural parent training: A mixed methods study protocol. BMJ Open, 9(7), e028988. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-028988

- Barnett, M. L., Sheldrick, R. C., Liu, S. R., Kia-Keating, M., & Negriff, S. (2021). Implications of adverse childhood experiences screening on behavioral health services: A scoping review and systems modeling analysis. The American Psychologist, 76(2), 364–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000756

- Baumann, A. A., & Cabassa, L. J. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3

- Becker, K. D., Boustani, M., Gellatly, R., & Chorpita, B. F. (2018). Forty years of engagement research in children’s mental health services: Multidimensional measurement and practice elements. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1326121

- Bodenheimer, T., Wagner, E. H., & Grumbach, K. (2002). Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(14), 1775–1779. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.14.1775

- Bolton, P., Lee, C., Haroz, E., Murray, L., & Dorsey, S. (2014). A transdiagnostic community-based mental health treatment for comorbid disorders: Development and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial among. PLoS Medicine, 11(11), e1001757. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001757

- Braveman, P. (2014). What are health disparities and health equity? we need to be clear. Public Health Reports, 129(SUPPL. 2), 5–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S203

- Broder-Fingert, S., Kuhn, J., Sheldrick, R. C., Chu, A., Fortuna, L., Jordan, M., Rubin, D., & Feinberg, E. (2019). Using the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) framework to test intervention delivery strategies: a study protocol. Trials, 20(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3853-y

- Broder-Fingert, S., Qin, S., Goupil, J., Rosenberg, J., Augustyn, M., Blum, N., Bennett, A., Weitzman, C., Guevara, J. P., Fenick, A., Silverstein, M., & Feinberg, E. (2019). A mixed-methods process evaluation of Family Navigation implementation for autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(5), 1288–1299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318808460

- Broder-Fingert, S., Stadnick, N. A., Hickey, E., Goupil, J., Diaz Lindhart, Y., & Feinberg, E. (2019). Defining the core components of family navigation for autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(3), 653–664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319864079

- Broder-Fingert, S., Walls, M., Augustyn, M., Beidas, R., Mandell, D., Wiltsey-Stirman, S., Silverstein, M., & Feinberg, E. (2018). A hybrid type I randomized effectiveness-implementation trial of patient navigation to improve access to services for children with autism spectrum disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1661-7

- Chaffin, M., Silovsky, J. F., Funderburk, B., Valle, L. A., Brestan, E. V., Balachova, T., Jackson, S., Lensgraf, J., & Bonner, B. L. (2004). Parent-child interaction therapy with physically abusive parents: Efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 500–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.500

- Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., Malik, K., Gellatly, R., Boustani, M. M., Michelson, D., Knudsen, K., Mathur, S., & Patel, V. H. (2020). Design process and protocol description for a multi-problem mental health intervention within a stepped care approach for adolescents in India. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 133, 103698. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2020.103698

- Coker, T. R., Elliott, M. N., Kataoka, S., Schwebel, D. C., Mrug, S., Grunbaum, J. A., Cuccaro, P., Peskin, M. F., & Schuster, M. A. (2009). Racial/ethnic disparities in the mental health care utilization of fifth grade children. Academic Pediatrics, 9(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2008.11.007

- Condon, E. M., Dettmer, A. M., Gee, D. G., Hagan, C., Lee, K. S., Mayes, L. C., Stover, C. S., & Tseng, W.-L. (2020). Commentary: COVID-19 and mental health equity in the United States. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 584390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.584390

- Derr, A. S. (2016). Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 67( 3), 265–274. American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500004

- Diebold, A., Ciolino, J. D., Johnson, J. K., Yeh, C., Gollan, J. K., & Tandon, S. D. (2020). Comparing fidelity outcomes of paraprofessional and professional delivery of a perinatal depression preventive intervention. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(4), 597–605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01022-5

- Dopp, A. R., Narcisse, M.-R., Mundey, P., Silovsky, J. F., Smith, A. B., Mandell, D., Funderburk, B. W., Powell, B. J., Schmidt, S., Edwards, D., Luke, D., & Mendel, P. (2020). A scoping review of strategies for financing the implementation of evidence-based practices in behavioral health systems: State of the literature and future directions. Implementation Research and Practice, 1, 263348952093998. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489520939980

- Dorsey, S., Lucid, L., Martin, P., King, K. M., O’Donnell, K., Murray, L. K., Wasonga, A. I., Itemba, D. K., Cohen, J. A., Manongi, R., & Whetten, K. (2020). Effectiveness of task-shifted trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children who experienced parental death and posttraumatic stress in Kenya and Tanzania: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(5), 464–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4475

- Dua, T., Barbui, C., Clark, N., Fleischmann, A., Poznyak, V., Van Ommeren, M., Yasamy, M. T., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Birbeck, G. L., Drummond, C., Freeman, M., Giannakopoulos, P., Levav, I., Obot, I. S., Omigbodun, O., Patel, V., Phillips, M., Prince, M., Rahimi-Movaghar, A., & Saxena, S. (2011). Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: Summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Medicine, 8(11), e1001122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001122

- Feinberg, E., Augustyn, M., Broder-Fingert, S., Bennett, A., Weitzman, C., Kuhn, J., Hickey, E., Chu, A., Levinson, J., Sandler Eilenberg, J., Silverstein, M., Cabral, H. J., Patts, G., Diaz-Linhart, Y., Rosenberg, J., Miller, J. S., Guevara, J. P., Fenick, A. M., & Blum, N. J. (2021). Effect of family navigation on diagnostic ascertainment among children at risk for autism: A randomized clinical trial from DBPNet. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(3), 243–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5218

- Flores, I., Consoli, A. J., Gonzalez, J. C., Luis Sanchez, B. E., & Barnett, M. L. (2021). “Todo se hace de corazón:” An examination of role and identity among Latina promotoras de salud. Journal of Latinx Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000194

- Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M., Boles, S. M., & Glasgow, E. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322

- Gonzalez, J. C., Flores, I., Tremblay, M., & Barnett, M. L. (under review). Lay health workers engaging Latino fathers: A mixed-methods study. Children & Youth Services review.

- Gustafson, E. L., Atkins, M., & Rusch, D. (2018). Community health workers and social proximity: Implementation of a parenting program in urban poverty. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3–4), 449–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12274

- Gustafson, E. L., Lakind, D., Walden, A. L., Rusch, D., & Atkins, M. S. (2021). Engaging parents in mental health services: A qualitative study of community health workers’ strategies in high poverty urban communities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01124-8

- Heard, E., Fitzgerald, L., Wigginton, B., & Mutch, A. (2020). Applying intersectionality theory in health promotion research and practice. Health Promotion International, 35(4), 866–876. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daz080

- Hoagwood, K. E., Cavaleri, M. A., Olin, S. S., Burns, B. J., Slaton, E., Gruttadaro, D., & Hughes, R. (2010).Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5

- Hoagwood, K. E., Olin, S. S., Storfer-Isser, A., Kuppinger, A., Shorter, P., Wang, N. M., Pollock, M., Peth-Pierce, R., & Horwitz, S. (2018). Evaluation of a train-the-trainers model for family peer advocates in children’s mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(4), 1130–1136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0961-8

- Horwitz, S. M. C., Cervantes, P., Kuppinger, A. D., Quintero, P. L., Burger, S., Lane, H., Bradbury, D., Cleek, A. F., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2020). Evaluation of a web-based training model for family peer advocates in children’s mental health. Psychiatric Services, 71(5), 502–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900365

- Jack, H. E., Myers, B., Regenauer, K. S., & Magidson, J. F. (2020). Mutual capacity building to reduce the behavioral health treatment gap globally. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(4), 497–500. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00999-y

- Jacobs, R., Guo, S., Kaundinya, P., & Lakind, D. (2017). A pilot study of mindfulness skills to reduce stress among a diverse paraprofessional workforce. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 2579–2588. http://link.springer.com/article/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0771-z

- Jamison, J. M., Fourie, E., Siper, P. M., Trelles, M. P., George-Jones, J., Buxbaum Grice, A., Krata, J., Holl, E., Shaoul, J., Hernandez, B., Mitchell, L., McKay, M. M., Buxbaum, J. D., & Kolevzon, A. (2017). Examining the efficacy of a family peer advocate model for Black and Hispanic caregivers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(5), 1314–1322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3045-0

- Javadi, D., Feldhaus, I., Mancuso, A., & Ghaffar, A. (2017). Applying systems thinking to task shifting for mental health using lay providers: A review of the evidence. Global Mental Health, 4(e14), 1–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.15

- Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(4), 567–589. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9

- Kangovi, S., Mitra, N., Grande, D., Long, J. A., & Asch, D. A. (2020). Evidence-based community health worker program addresses unmet social needs and generates positive return on investment. Health Affairs, 39(2), 207–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00981

- Kaplan, R. M. (2000). Two pathways to prevention. American Psychologist, 55(4), 382–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.4.382

- Katigbak, C., Van Devanter, N., Islam, N., & Trinh-Shevrin, C. (2015). Partners in health: A conceptual framework for the role of community health workers in facilitating patients’ adoption of healthy behaviors. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 872–880. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302411

- Kazdin, A. E., & Rabbitt, S. M. (2013). Novel models for delivering mental health services and reducing the burdens of mental illness. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(2), 170–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702612463566

- Keynejad, R., Spagnolo, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2021). WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: Updated systematic review on evidence and impact. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 24, 124–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2021-300254

- Kia-Keating, M., Santacrose, D. E., Liu, S. R., & Adams, J. (2017). Using community-based participatory research and human-centered design to address violence-related health disparities among Latino/a youth. Family and Community Health, 40(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000145

- Kidman, R., Margolis, R., Smith-Greenaway, E., & Verdery, A. M. (2021). Estimates and projections of COVID-19 and parental death in the US. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(7), 745. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0161

- Kim, J. J., Brookman-Frazee, L., Gellatly, R., Stadnick, N., Barnett, M. L., & Lau, A. S. (2018). Predictors of burnout among community therapists in the sustainment phase of a system-driven implementation of multiple evidence-based practices in children’s mental health. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000182

- Klein, C., Luis Sanchez, E., Gonzalez, J. C., Flores, I., Green Rosas, Y., & Barnett, M. L. (2020). The role of advocacy in community-partnered research with lay health workers in latinx communities (promotoras de salud). The Behavior Therapist, 43(7), 250–254.

- Landers, S., & Levinson, M. (2016). Mounting evidence of the effectiveness and versatility of community health workers. American Journal of Public Health, 106(4), 591–592. American Public Health Association Inc. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303099

- Liu, S. R., & Modir, S. (2020). The outbreak that was always here: Racial trauma in the context of COVID-19 and implications for mental health providers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 439–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000784

- Luke, D. A., & Stamatakis, K. A. (2012). Systems science methods in public health: Dynamics, networks, and agents. Annual Review of Public Health, 33, 357–376. Annual Reviews. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222

- Magidson, J. F., Jack, H. E., Regenauer, K. S., & Myers, B. (2019). Applying lessons from task sharing in global mental health to the opioid crisis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(10), 962–966. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000434

- McCollum, R., Gomez, W., Theobald, S., & Taegtmeyer, M. (2016). How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services? A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 16( 1), 1–16. BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3043-8

- Mehta, T. G., Lakind, D., Rusch, D., Walden, A. L., Cua, G., & Atkins, M. S. (2019). Collaboration with urban community stakeholders: Refining paraprofessional‐led services to promote positive parenting. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(3–4), 444–458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12316

- Miranda, J., Bernal, G., Lau, A., & Kohn, L. (2005). State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 113–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143822

- Mundeva, H., Snyder, J., Ngilangwa, D. P., & Kaida, A. (2018). Ethics of task shifting in the health workforce: Exploring the role of community health workers in HIV service delivery in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0312-3

- Murray, L., Dorsey, S., & Bolton, P. (2011). Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: An apprenticeship model for training local providers. Journal of Mental and Behavioral Practice, 5(30), 1–12. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S107772291300062X

- Murray, L. K., Dorsey, S., Haroz, E., Lee, C., Alsiary, M. M., Haydary, A., Weiss, W. M., & Bolton, P. (2014). A common elements treatment approach for adult mental health problems in low-and middle-income countries. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21(2), 111–123.

- National Institute of Health. (2020). Notice of special interest: Simulation modeling and system science to address health disparities. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-MD-20-025.html

- NeMoyer, A., Cruz-Gonzalez, M., Alvarez, K., Kessler, R. C., Sampson, N. A., Green, J. G., & Alegría, M. (2020). Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among emerging adults: Community-level supply factors. Ethnicity & Health, 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1814999

- Ohtani, A., Suzuki, T., Takeuchi, H., & Uchida, H. (2015). Language barriers and access to psychiatric care: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 66( 8), 798–805. American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400351

- Olaniran, A., Smith, H., Unkels, R., Bar-Zeev, S., & Van den Broek, N. (2017). Who is a community health worker? - A systematic review of definitions. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1272223. Co-Action Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1272223

- Patel, V., Weiss, H. A., Chowdhary, N., Naik, S., Pednekar, S., Chatterjee, S., Bhat, B., Araya, R., King, M., Simon, G., Verdeli, H., & Kirkwood, B. R. (2011). Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: Impact on clinical and disability outcomes over 12 months. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 459–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092155

- Patel, V., Weiss, H. A., Chowdhary, N., Naik, S., Pednekar, S., Chatterjee, S., De Silva, M. J., Bhat, B., Araya, R., King, M., Simon, G., Verdeli, H., & Kirkwood, B. R. (2010). Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 376(9758), 2086–2095. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5

- Peretz, P. J., Islam, N., & Matiz, L. A. (2020). Community health workers and Covid-19 — Addressing social determinants of health in times of crisis and beyond. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(19), e108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2022641

- Philbin, M. M., Flake, M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Hirsch, J. S. (2018). State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 29–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007

- Puffer, E. S., Green, E. P., Chase, R. M., Sim, A. L., Zayzay, J., Friis, E., Garcia-Rolland, E., & Boone, L. (2015). Parents make the difference: A randomized-controlled trial of a parenting intervention in Liberia. Global Mental Health, 2, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2015.12

- Purtle, J. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health equity in the United States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55( 8), 969–971. Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01896-8

- Rahman, R., Ross, A., & Pinto, R. (2021). The critical importance of community health workers as first responders to COVID-19 in USA. Health Promotion International. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab008

- Rhodes, S., Foley, K., Zometa, C., & Bloom, F. (2007). Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: A qualitative systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(5), 418–427. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379707004667

- Rodriguez, J., Olin, S. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Shen, S., Burton, G., Radigan, M., & Jensen, P. S. (2011). The development and evaluation of a parent empowerment program for family peer advocates. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(4), 397–405. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-010-9405-4

- Sheldrick, R. C., Cruden, G., Schaefer, A. J., & Mackie, T. I. (2021). Rapid-cycle systems modeling to support evidence-informed decision-making during system-wide implementation. Research Square. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-409274/v1

- Shelton, R. C., Chambers, D. A., & Glasgow, R. E. (2020). An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: Addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134

- Shelton, R. C., Charles, T.-A., Dunston, S. K., Jandorf, L., & Erwin, D. O. (2017). Advancing understanding of the sustainability of lay health advisor (LHA) programs for African-American women in community settings. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 7(3), 415–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-017-0491-3

- Silverstein, M., Diaz-Linhart, Y., Cabral, H., Beardslee, W., Broder-Fingert, S., Kistin, C. J., Patts, G., & Feinberg, E. (2018). Engaging mothers with depressive symptoms in care: Results of a randomized controlled trial in Head Start. Psychiatric Services, 69(11), 1175–1180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800173

- Singla, D. R., Kohrt, B. A., Murray, L. K., Anand, A., Chorpita, B. F., & Patel, V. (2017). Psychological treatments for the world: Lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 149–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045217

- Srivastav, A., Fairbrother, G., & Simpson, L. A. (2017). Addressing adverse childhood experiences through the affordable care act: Promising advances and missed opportunities. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7), S136–S143. Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.007

- Stadnick, N. A., Aarons, G. A., Blake, L., Brookman-Frazee, L. I., Dourgnon, P., Engell, T., Jusot, F., Lau, A. S., Prieur, C., Skar, A. M. S. & Barnett, M. L. (2020, April). Leveraging implementation science to reduce inequities in Children’s mental health care: Highlights from a multidisciplinary international colloquium. In BMC Proceedings, 14(2) 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-020-00184-2

- Stewart, R. E., Mandell, D. S., & Beidas, R. S. (2021). Lessons from Maslow: Prioritizing funding to improve the quality of community mental health and substance use services. Psychiatric Services, appi.ps.2020002. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000209

- Tandon, S. D., Johnson, J. K., Diebold, A., Segovia, M., Gollan, J. K., Degillio, A., Zakieh, D., Yeh, C., Solano-Martinez, J., & Ciolino, J. D. (2021). Comparing the effectiveness of home visiting paraprofessionals and mental health professionals delivering a postpartum depression preventive intervention: A cluster-randomized non-inferiority clinical trial. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-021-01112-9

- Triplett, N. S., Munson, S., Mbwayo, A., Mutavi, T., Weiner, B. J., Collins, P., Amanya, C., & Dorsey, S. (2021). Applying human-centered design to maximize acceptability, feasibility, and usability of mobile technology supervision in Kenya: A mixed methods pilot study protocol. Implementation Science Communications, 2(1), 2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-020-00102-9

- Wall, J. T., Kaiser, B. N., Friis-Healy, E. A., Ayuku, D., & Puffer, E. S. (2020). What about lay counselors’ experiences of task-shifting mental health interventions? Example from a family-based intervention in Kenya. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00343-0

- Wells, K. J., Battaglia, T. A., Dudley, D. J., Garcia, R., Greene, A., Calhoun, E., Mandelblatt, J. S., Paskett, E. D., & Raich, P. C. (2008). Patient navigation: State of the art or is it science? Cancer, 113(8), 1999–2010. Cancer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23815

- Whitney, D. G., & Peterson, M. D. (2019). US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(4), 389–391. American Medical Association. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399

- Williamson, A. A., Knox, L., Guerra, N. G., & Williams, K. R. (2014). A pilot randomized trial of community-based parent training for immigrant Latina mothers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(1–2), 47–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9612-4

- Woodward, E. N., Matthieu, M. M., Uchendu, U. S., Rogal, S., & Kirchner, J. E. (2019). The health equity implementation framework: Proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0861-y