ABSTRACT

Objective

Cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, research has yet to examine what cognitive characteristics may influence treatment response. The current study investigated decision-making ability and social cognition as potential (a) predictors of differential treatment response to two versions of CBT and (b) moderators of the effect of treatment condition.

Method

The study included 148 children (mean age = 9.8 years) with interfering anxiety and a diagnosis of ASD who were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing two versions of CBT for anxiety (standard and adapted for ASD). Participants completed pretreatment measures of decision-making ability (adapted Iowa Gambling Task) and social cognition (Strange Stories) and analyses tested whether task performance predicted treatment response across and between (moderation) treatment conditions.

Results

Our findings indicate that decision-making ability moderated treatment outcomes in youth with ASD and anxiety, with a better decision-making performance being associated with higher post-treatment anxiety scores for those who received standard, not adapted, CBT.

Conclusions

Children with ASD and anxiety who are more sensitive to reward contingencies and reinforcement may benefit more from adapted CBT approaches that work more explicitly with reward.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous condition, with individual variability in core symptoms (i.e., social communication difficulties and restricted interests and repetitive behaviors) and cognitive functioning, including both the degree of intellectual ability and in specific domains such as executive functioning and social cognition (Charman et al., Citation2011). Anxiety is common in children with ASD, with 20–40% of young people meeting criteria for at least one anxiety disorder (Lai et al., Citation2019). The high degree of individual variability in cognitive functioning in ASD adds to the complexity of developing psychological treatments for anxiety that are effective across this complex population.

Evidence indicates that several versions of cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) can be effective for anxiety in young people with ASD. The benefits are most clear when the intervention is adapted to account for the specific differences in cognitive functioning associated with ASD (Wood et al., Citation2020). Given the high prevalence of anxiety in ASD and the impact additional mental health difficulties have on outcomes and quality of life (Van Steensel et al., Citation2012), understanding how to maximize outcomes in this population is vital. Of interest is whether specific cognitive variables associated with ASD influence differential treatment response and could therefore be targets for further adaptions or specific treatment modules.

Of particular interest is the relationship between an individual’s decision-making ability and their ability to benefit from CBT. Decision-making is a complex transdiagnostic construct (Sonuga-Barke et al., Citation2016) that requires an individual to identify, compare, and select actions to maximize subjective future reward (Oppenheimer & Kelso, Citation2015). This is relevant to CBT, as effective treatment requires behavioral change via a process of gradual risk taking (e.g., exposure, behavioral experiments), consciously making the decisions to change unhelpful thoughts and behaviors, for a future reward (reduced distress). In neurotypical samples, differences in reward sensitivity have been associated with CBT outcomes for those with anxiety (Norris et al., Citation2021). Evidence suggests that rather than being a “cold” cognitive process, decision-making is influenced by emotions (Greene & Haidt, Citation2002), with heightened anxiety creating reasoning biases (Raghunathan & Pham, Citation1999). This distinction is important when considering young people with ASD who have both a high prevalence of comorbid anxiety (Lai et al., Citation2019) and impairments in executive functioning (Demetriou et al., Citation2018). Taken together, this suggests differences in reward sensitivity may be one factor that could influence CBT response in those with ASD.

Few studies have investigated the relationship between decision-making and symptoms of anxiety in ASD. South et al. (Citation2011) found that in a group of adolescents with ASD, increased anxiety was associated with more risk-based decision-making, which was the opposite of what was found in their neurotypical comparison group. This finding was interpreted as anxiety driving more risk-based decision behavior in ASD due to fear of failure (South et al., Citation2011). In a study using the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), youth with ASD had an elevated performance compared to typically developing youth but with a decision-making style that was characterized by a drive to avoid potential loss (South et al., Citation2014). This suggests that while task performance is enhanced in those with ASD, the real-world consequence may be avoidance in social or other complex settings. The relationship between IGT performance and response to CBT has yet to be investigated in ASD.

Another important domain of functioning that may play a role in effective CBT is social cognition, here referring to the processing of social information to effectively detect and understand others’ emotions and social intent (Henry et al., Citation2016). Difficulties with social cognition may negatively impact the ability to benefit from CBT by reducing the ability to learn from new social experiences that may occur as a part of the intervention or even fully engaging in therapy itself. There has been little evidence to support a direct relationship between tests of theory of mind and anxiety symptoms in ASD (Hollocks et al., Citation2014). However, there is some evidence to suggest that thinking biases related to interpreting ambiguous social situations as threatening may drive symptoms of anxiety in ASD (Hollocks et al., Citation2016). To date, the impact of social cognition on CBT for youth with anxiety and ASD has not been investigated.

The present study expands previous work from the TAASD study (Kerns et al., Citation2016; Wood et al., Citation2020), a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating CBT for anxiety in children with ASD and anxiety. Young people were randomized to either the BIACA (CBT adapted for ASD; Wood et al., Citation2020) or Coping Cat (standard CBT; Kendall & Hedtke, Citation2006a, Citation2006b), with results indicating that both led to significant reductions in anxiety when compared to treatment as usual, with BIACA having an additional benefit. The current study investigates whether measures of decision-making ability and/or social cognition (a) predict treatment response across both treatments, or (b) moderate the effect of treatment condition. The later analyses will address the question of which young people with ASD are most likely to benefit from the different versions of CBT.

Methods

Participants

This study included 148 children with ASD and anxiety who completed an RCT of CBT for anxiety (see Wood et al., Citation2020). Participants were between 7 and 13 years of age, had a diagnosis of ASD, a full-scale IQ ≥70, and a Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology [RUPP], Citation2002) score of ≥14, across 7-items, which is indicative of maladaptive/interfering anxiety (Storch et al., Citation2012). Ethical approval for the study was given by university-based institutional review boards at each university (University of California, Los Angeles general institutional review board, University of South Florida institutional review board, and Temple University’s Human Research Protection Program).

Procedure

Study recruitment ran from April 2014 to January 2017. Participants were randomized to either (1) standard-of-practice CBT (Coping Cat program; [Podell et al., Citation2010]), (2) CBT adapted for ASD (Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism [BIACA] program; [Wood et al., Citation2009]), or (3) treatment as usual (TaU). Because the aim of the current analyses is to investigate predictors/moderators of CBT response TaU participants were not included. Cognitive measures were administered at baseline, whilst PARS was administered at baseline, mid-, and post-intervention. Assessments were conducted by trained independent evaluators, masked to treatment condition. The ASD diagnoses were confirmed by an independent evaluator using the Childhood Autism Rating Scale Second Edition–High Functioning Version and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–2 (ADOS-2). See Wood et al. (Citation2020) for a full-study procedure for the RCT.

Interventions

Coping Cat

Participants received 16 weekly 60-minute sessions, which has previously been found to be effective in treating anxiety in typically developing youth aged 7–13 years (see Kendall et al., Citation2008; Silk et al., Citation2018; Walkup et al., Citation2008). The program includes (1) recognizing anxious feelings and somatic reactions to anxiety, (2) identifying thoughts in anxiety-provoking situations (e.g., expectations of threat), (3) developing a plan to cope (e.g., reappraisal), (4) imaginal and in vivo exposure tasks, and (5) self-reinforcement for effort. Coping modeling, role-play, and reinforcement are used during treatment. Specific between session homework tasks are assigned. Parental involvement is in two sessions and a 15-minute check-in at the start of each session.

Adapted CBT (BIACA)

Like Coping Cat, BIACA used CBT strategies such as reappraisal of unhelpful thoughts and exposure. The BIACA program differs in that children (1) receive 16 weekly 90-minute sessions (split evenly between children and parents); (2) a modular format guided by an algorithm to personalize treatment; (3) antecedent and incentive-based practices to reduce the influence of aggression and noncompliance on treatment engagement; (4) social engagement skills (e.g., playdate hosting, joining peers at play); (5) special interests are treated as an asset and incorporated into treatment; and (6) target behaviors are reinforced with a reward system at home and, when relevant, in school to promote motivation and treatment engagement.

Therapists’ adherence to the interventions was monitored through session audio recordings. A random selection of sessions (92 for BIACA and 70 for Coping Cat) was coded for fidelity (P.C.K. and J.J.W.) and trained research assistants. Coders noted the presence or absence of required topics for each session. There was adherence of 97% for BIACA and 96% for Coping Cat sessions.

Measures

Measure of Anxiety

Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS)

The primary outcome measure was the PARS (RUPP, Citation2002), an independent evaluator-administered scale assessing anxiety symptoms and associated severity and impairment. The PARS Severity Scale scores range from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more maladaptive and interfering anxiety. A total score was created by averaging the scores on the seven items. The PARS has strong psychometric properties when used with children with ASD, including high test–retest (Intraclass correlation = 0.83) and inter-rater reliability (Intraclass correlation = 0.86) and an adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.59; Storch et al., Citation2012). This was found to be slightly higher in the current sample when tested at baseline (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.64). For the current analysis, we used the post-treatment PARS as the dependent variable and pre-treatment PARS to control for baseline anxiety.

Cognitive Measures

Adapted Iowa Gambling Task

This study used an adapted version of the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), simplified specifically for use by children (Garon & Moore, Citation2004). The task consisted of two blocks of 40 card selections with each block using two different sets of four decks. Each set consisted of two advantageous and two disadvantageous decks. Each card from the disadvantageous decks had two bears (which indicated a win of two points) and some cards contained pictures of tigers (which indicated loss). Each card from the advantageous decks had one bear (which indicated a win of one point), and some cards contained pictures of tigers (which indicated loss of points). The primary measure is the number of selections from advantageous decks summed across both blocks (possible score range 0–80).

In addition, an awareness test is completed at the end of each block that consisted of four questions. The first two questions focused on the advantageous decks and consisted of the questions: 1) “Now that we are done the game, which deck was the best to pick from?”; and “Why do you think this was the best to pick from?.” If children identified that they chose one of the advantageous decks for the first question, they were awarded a point. If children were further able to give an answer to the second question indicating the ratio of bears to tigers was higher for the advantageous deck, they were awarded two points. The last two questions proceeded in the same way, except that children were asked about the disadvantageous decks. For the present analysis, the scores for each block were combined into an awareness total score ranging from 0 to 8, with a higher score representing greater awareness. Based on the original study of those without ASD, you would expect children age 6 years or above to achieve a mean score of 6/8 on this task (Garon & Moore, Citation2004).

Strange stories task

The strange stories task (Happé, Citation1994; Happé et al., Citation1999) measures mental state understanding that requires the attribution of mental states underlying non-literal scenarios (e.g., double bluffs, misunderstandings, lies, etc.). The participants were read a series of stories at the end of which they were required to answer a question about the scenario. The participants were exposed to four stories with a theory of mind component with each being scored on a 0–2 scale, with “0” representing an incorrect or “I don’t know response,” “1” a partial or implicitly correct response, and “2” an explicitly correct response, resulting in a score that ranged from 0 to 8. Previous studies using a similar version of this task have indicated that a mean score of around 3.2 would be expected in ASD, versus 5.8 in typically developing controls (Brent et al., Citation2004).

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children 4th edition

The WISC-IV measures general intelligence in children. The WISC-IV generates a Full-Scale IQ (FSIQ), representing overall cognitive ability. For this analysis, FSIQ will be included as a covariate of “no interest” to account for variance in overall intellectual ability in analysis with the IGT and strange stories tasks as predictors.

Statistical Analysis

Participants were included on an intent-to-treat basis with all participants enrolled into a treatment condition being included in the final analysis. Multiple imputation using predictive mean matching (pmm) was used to handle missing data attributable to study drop-out (n = 22). Those who dropped out had a marginally higher baseline PARS score (completers = 3.4; dropouts = 3.61; p = .05), which was accounted for in the imputation. Initial analysis of the RCT included study site as a predictor of treatment response due to differences in variables including ethnicity, household income, and autism severity, but this had no effect on treatment outcomes and so was omitted from the current analysis (see Wood et al., Citation2020).

For both predictors, a separate multiple regression analysis on the imputed dataset with post-treatment PARS anxiety score as the dependent variable was estimated. For each regression model, an interaction between intervention condition and the predictor (moderation) was included along with main effects. Both baseline PARS score (to control for pretreatment anxiety) and FSIQ (to control for overall intellectual functioning) were included as covariates.

Sensitivity analysis

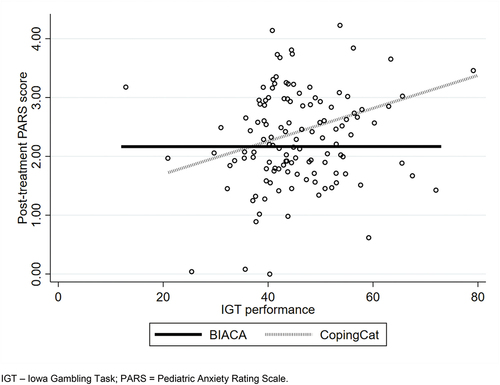

Despite being normally distributed, the spread of the data on both the IGT and PARS outcome scores (see ) warranted further analysis to determine with confidence any moderating effect. To account for the distribution of these variables, and limitations around the power of standard moderation approaches, the analysis was repeated using a non-parametric bootstrap (1000 repetitions) of the imputed data to re-calculate the confidence intervals of the moderation effect (Little & Rubin, Citation2002).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The sample included 148 children with ASD and anxiety randomized to Coping Cat (n = 71) or BIACA (n = 77). The overall sample had a mean age of 9.8 years (range 7–13 years) with no significant difference between conditions in terms of the male-to-female ratio (BIACA 55:21, Coping Cat 58:13; χ2 = 1.8, p = .18). There was no significant difference between treatment conditions on any other descriptive variable (see ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Predictors and Moderators of CBT Outcomes

Iowa Gambling Task

Regression results are presented in . The model was significant (F (5, 118.9) = 5.1, p ≤ .01; r2 = 0.19) and indicated that performance on the gambling task (as measured by advantageous deck selection) was a significant moderator between intervention condition and treatment response (b = −0.028; uncorrected p = .065; bootstrap estimated p = .029).

Table 2. Results of regression analyses of the associations between neuro-psychological variables and post-treatment anxiety scores.

To interpret the interaction, the non-imputed data were plotted (). The figure shows that while there is little association between task performance and outcome for participants in BIACA, a better performance on the gambling task was associated with a worse outcome for those receiving Coping Cat. This effect was confirmed by repeating the regression models “within-groups” that showed a significant association between better gambling task performance and higher post-treatment anxiety scores in the Coping Cat condition only (Coping Cat: b = 0.03; p = .02; BIACA: b = −0.003; p = .78).

The analysis was repeated using the gambling task awareness score, which was not a significant predictor (b = −0.4; p = .21), or moderator of treatment response (b = −0.07; p = .34).

Strange Stories Task

The regression model including performance on the Strange Stories task was found to be significant (F (5, 124.4) = 4.3, p ≤ .01; r2 = 0.16). However, the task performance did not predict CBT outcome (b = −0.001; p = .99), nor did it moderate the relationship between the treatment condition and the outcome (b = −0.05; p = .57). This indicates that the overall significance of the model was entirely explained by treatment condition and baseline anxiety severity.

Discussion

Our results indicate that reward-based decision-making moderates treatment outcomes in young people with ASD treated using CBT. Specifically, a better decision-making performance was associated with a less favorable outcome, but this relationship was found only for those who received standard CBT (Coping Cat), not the adapted version of CBT (BIACA). This suggests that children with ASD and anxiety who are more sensitive to reward contingencies and reinforcement are less likely to respond to Coping Cat, but that adapted CBT (BIACA) can be used for all levels of this variable. The finding that reward sensitivity moderates CBT treatment response is consistent with recent neuroimaging findings in those without ASD (Sequeira et al., Citation2021).

Previous studies found that young people with ASD can demonstrate an elevated performance in decision-making tasks compared to typically developing controls (South et al., Citation2014). This finding has previously been interpreted as enhanced performance driven by the need to avoid loss and which may have negative real-world consequence such as in increased avoidance behaviors, which are known to be associated with the maintenance of anxiety disorders (Norris & Kendall, Citation2021). In the context of neurodevelopmental conditions, previous research using the same version of the IGT found enhanced performance in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and comorbid anxiety compared to ADHD alone and healthy controls (Garon et al., Citation2006). These authors suggested that enhanced performance in those with anxiety is associated with a greater sensitivity to reinforcement learning, particularly through stronger avoidance of loss. This may explain why, in the current study, young people who show better reward-based decision-making may be less responsive to treatment when using the non-adapted CBT, which places less emphasis on reward.

A major adaptation made to BIACA and difference when compared to non-adapted CBT programs is the emphasis on the use of reward as a part of the intervention in a structured way. BIACA uses repeated in-session rewards and parents use daily reward schedules to reinforce in session learning, with rewards carefully selected based on the child’s interests to maximize salience. The program therefore uses reward and reinforcement to achieve goals to a much greater degree than typical CBT. Indeed, by making the relationship between behavior and reward more explicit, it may act to harness the suggested enhanced sensitivity to positive reward contingencies to promote more adaptive behavior.

Consistent with the previous research showing no significant relationships between measures of social cognition and anxiety in ASD (Hollocks et al., Citation2014), this study found that social cognition did not predict CBT treatment response. This finding could be seen as surprising given the relevance of social cognition to the core symptoms of ASD and based on more anecdotal clinical experience that social misunderstanding, or difficulties understanding the intent of others, can lead to significant anxiety for young people with ASD. It is possible that more ecologically valid tasks or measures that focus more on the attribution of social threat (Hollocks et al., Citation2016) may be more sensitive to both symptom severity and may be better predictors of treatment response.

This study benefits from using RCT data and a well-characterized sample. The sample included those with comorbid conditions (i.e., depression, ADHD, etc.) meaning that the sample is representative of the complex presentations seen in ASD. However, there are limitations. The study was powered to detect treatment effects and therefore the sample may be considered modest when conducting moderation analyses. We overcame this by applying statistical methods to robustly explore moderation, but the results merit replication. Additionally, whilst the aim of this study was not to test the relative efficacy of the individual interventions, it should be noted that differences in the duration of sessions may have influenced our results. Similarly, whilst treatment fidelity was high, there remains a possibility that skilled clinicians delivering the non-adapted intervention may have introduced additional adaptation (e.g., social skills training) that may have influenced our results. Future research might beneficially stratify children on task performance at baseline (during randomization) to better understand the impact of cognitive processes on CBT treatment outcomes.

Clinical Implications

The results suggest that to maximize CBT outcomes for anxious children with ASD, those with a decision-making profile characterized by enhanced performance may be more likely to benefit from an adapted intervention, which explicitly uses repeated in-session reward and reinforcement strategies with young people and supports parents to implement reward schedules in parallel at home. This implication is consistent with the view that CBT with young people with ASD should have a strong focus on behavioral approaches. Understanding the cognitive and clinical characteristics of those who may benefit most from adapted CBT and the elements of therapy that may be most helpful is an important step to provide individualized approaches for young people with ASD and direct clinical resources to where they are needed most.

Disclosure Statement

Dr Wood reported grants from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study. Dr Kendall reported receiving royalties, and his spouse has income from the sales of publications of materials about the treatment of anxiety disorders in youth. Dr Kerns reported receiving honoraria for presenting on her research on anxiety and autism, as well as consultation fees for training staff at other research sites in anxiety and autism assessment, outside the submitted work. Dr Storch reported personal fees from Levo Therapeutics, Elsevier, Wiley, the American Psychological Association, Springer, and Oxford and grants from Red Cross, ReBuild Texas, the National Institutes of Health, and Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- Brent, E., Rios, P., Happé, F., & Charman, T. (2004). Performance of children with autism spectrum disorder on advanced theory of mind tasks. Autism, 8(3), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361304045217

- Charman, T., Pickles, A., Simonoff, E., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2011). IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders: Data from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Psychological Medicine, 41(3), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000991

- Demetriou, E. A., Lampit, A., Quintana, D. S., Naismith, S. L., Song, Y. J. C., Pye, J. E., Hickie, I., & Guastella, A. J. (2018). Autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis of executive function. Molecular Psychiatry, 23(5), 1198–1204. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.75

- Garon, N., Moore, C., & Waschbusch, D. A. (2006). Decision making in children with ADHD only, ADHD-anxious/depressed, and control children using a child version of the Iowa gambling task. Journal of Attention Disorders, 9(4), 607–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054705284501

- Garon, N., & Moore, C. (2004). Complex decision-making in early childhood. Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00272-0

- Greene, J., & Haidt, J. (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(12), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(02)02011-9

- Happé, F. G. E., Winner, E., & Brownell, H. (1999). The getting of wisdom: Theory of mind in old age. Developmental Psychology, 34(2), 358–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.2.358

- Happé, F. G. E. (1994). An advanced test of theory of mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(2), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172093

- Henry, J. D., Von Hippel, W., Molenberghs, P., Lee, T., & Sachdev, P. S. (2016). Clinical assessment of social cognitive function in neurological disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology, 12(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.229

- Hollocks, M. J., Jones, C. R. G., Pickles, A., Baird, G., Happé, F., Charman, T., & Simonoff, E. (2014). The association between social cognition and executive functioning and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research, 7(2), 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1361

- Hollocks, M. J., Pickles, A., Howlin, P., & Simonoff, E. (2016). Dual cognitive and biological correlates of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3295–3307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2878-2

- Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. (2006a). Coping cat workbook (2nd ed.). Workbook Publishing.

- Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. (2006b). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual (3rd ed.). Workbook Publishing.

- Kendall, P. C., Hudson, J. L., Gosch, E., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Suveg, C. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 282. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282

- Kerns, C. M., Wood, J. J., Kendall, P. C., Renno, P., Crawford, E. A., Mercado, R. J., Fujii, C., Collier, A., Hoff, A., Kagan, E. R., Small, B. J., Lewin, A. B., & Storch, E. A. (2016). The Treatment of Anxiety in Autism Spectrum Disorder (TAASD) study: Rationale, design and methods. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(6), 1889–1902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0372-2

- Lai, M. C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S. H. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

- Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119013563

- Norris, L. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2021). Moderators of outcome for youth anxiety treatments: Current findings and future directions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 50(4), 450–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1833337

- Norris, L. A., Rabner, J. C., Mennies, R. J., Olino, T. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2021). Increased self-reported reward responsiveness predicts better response to cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 80, 102402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102402

- Oppenheimer, D. M., & Kelso, E. (2015). Information processing as a paradigm for decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015148

- Podell, J. L., Mychailyszyn, M., Edmunds, J., Puleo, C. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). The Coping Cat Program for anxious youth: The FEAR plan comes to life. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(2), 132–141.

- Raghunathan, R., & Pham, M. T. (1999). All negative moods are not equal: Motivational influences of anxiety and sadness on decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 79(1), 56–77. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1999.2838

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology. (2002). The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of the 1467 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(9), 1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006

- Sequeira, S. L., Silk, J. S., Ladouceur, C. D., Hanson, J. L., Ryan, N. D., Morgan, J. K., … Forbes, E. E. (2021). Association of neural reward circuitry function with response to psychotherapy in youths with anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(4), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20010094.

- Silk, J. S., Tan, P. Z., Ladouceur, C. D., Meller, S., Siegle, G. J., McMakin, D. L., Forbes, E. E., Dahl, R. E., Kendall, P. C., Mannarino, A., & Ryan, N. D. (2018). A randomized clinical trial comparing individual cognitive behavioral therapy and child-centered therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(4), 542–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1138408

- Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Cortese, S., Fairchild, G., & Stringaris, A. (2016). Annual Research Review: Transdiagnostic neuroscience of child and adolescent mental disorders - Differentiating decision making in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 57(3), 321–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12496

- South, M., Chamberlain, P. D., Wigham, S., Newton, T., Le Couteur, A., McConachie, H., Gray, L., Freeston, M., Parr, J., Kirwan, C. B., & Rodgers, J. (2014). Enhanced decision making and risk avoidance in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychology, 28(2), 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000016

- South, M., Dana, J., White, S. E., & Crowley, M. J. (2011). Failure is not an option: Risk-taking is moderated by anxiety and also by cognitive ability in children and adolescents diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1021-z

- Storch, E. A., Wood, J. J., Ehrenreich-May, J., Jones, A. M., Park, J. M., Lewin, A. B., & Murphy, T. K. (2012). Convergent and discriminant validity and reliability of the pediatric anxiety rating scale in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(11), 2374–2382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1489-9

- van Steensel, F. J. A., Bögels, S. M., & Dirksen, C. D. (2012). Anxiety and quality of life: Clinically anxious children with and without autism spectrum disorders compared. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(6), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.698725

- Walkup, J. T., Albano, A. M., Piacentini, J., Birmaher, B., Compton, S. N., Sherrill, J. T., Ginsburg, G. S., Rynn, M. A., McCracken, J., Waslick, B., Iyengar, S., March, J. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(26), 2753–2766. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0804633

- Wood, J. J., Drahota, A., Sze, K., Har, K., Chiu, A., & Langer, D. A. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 50(3), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x

- Wood, J. J., Kendall, P. C., Wood, K. S., Kerns, C. M., Seltzer, M., Small, B. J., Lewin, A. B., & Storch, E. A. (2020). Cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(5), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4160