ABSTRACT

Mental health organizations that serve youth are under pressure to adopt measurement-based care (MBC), defined as the continuous collection of client-report data used to support clinical decision-making as part of standard care. However, few frameworks exist to help leadership ascertain how to select an MBC approach for a clinical setting. This paper seeks to define how an MBC approach can display clinical utility to provide such a framework. Broadly, we define clinical utility as evidence that an MBC approach assists stakeholders in fulfilling clinical goals related to care quality (i.e., improve client-clinician alliance and clinical outcomes) at the client (i.e., youth and caregiver), clinician, supervisor, and administrator levels. More specifically, our definition of clinical utility is divided into two categories relevant to the usability and usefulness of an MBC approach for a specific setting: (a) implementability (i.e., evidence indicating ease of use in a clinical setting) and (b) usefulness in aiding clinical activities (i.e., evidence indicating the potential to improve communication and make clinical activities related to care quality easier or more effective). These categories provide valuable information about how easy an MBC approach is to use and the potential benefits that the MBC data will confer. To detail how we arrived at this definition, we review prior definitions of clinical utility, discuss how previous definitions inform our definition of clinical utility for MBC, and provide examples of how the concept of clinical utility can be applied to MBC. We finish with a discussion of future research directions.

Measurement-based care (MBC) is the systematic and continuous collection of data throughout treatment shared with stakeholders to support clinical decision-making and holds promise for optimizing clinical outcomes in mental health care for youth and their families (Lyon et al., Citation2016; Scott & Lewis, Citation2015). Clinical guidelines for the delivery of psychosocial treatments support the use of MBC (American Psychological Association, Citation2006; Lewis et al., Citation2019), and professional organizations have issued a statement supporting MBC as a cornerstone of evidence-based practice (e.g., Coalition for the Advancement and Application of Psychological Science, Citation2018). Since 2018, the Joint Commission healthcare accreditation organization has required MBC (The Joint Commission, Citation2018). In response to the growing evidence and regulatory pressures, mental health organizations are increasingly seeking to adopt MBC as a part of standard care. Yet, few guidelines are available to help organizational leadership determine what MBC approach to adopt. As discussed further below and detailed in , approaches to MBC vary along several dimensions, including the measures used and the characteristics of any technology used to support MBC. When selecting an MBC approach, two critical considerations for adoption and ongoing implementation are MBC effectiveness and clinical utility.

Table 1. Components of measurement based care approaches.

Whereas the parameters of evaluating the effectiveness of MBC are established (see, Kendrick et al., Citation2016), the field has yet to define how an MBC approach can demonstrate “clinical utility.” In mental health, the concept of clinical utility has a history stretching back over 20 years (e.g., Hunsley & Bailey, Citation1999), and has been applied to such topics as diagnostic systems, the conceptualization of personality disorders, and evidence-based assessment (e.g., First et al., Citation2004; Hunsley & Bailey, Citation1999; Milinkovic & Tiliopoulos, Citation2020). Across these applications, clinical utility has been defined in various ways, including the feasibility of implementation, usefulness, cost-effectiveness, potential to improve clinical decision making, and ability to enhance the effectiveness of treatment (First et al., Citation2004; Hunsley & Mash, Citation2007; Reed, Citation2010; Umscheid, Citation2010). We draw on this previous work to define how an MBC approach can display evidence of clinical utility based on how stakeholders (a) interact with the various MBC components, and (b) use MBC data to enhance communication, improve youth and caregiver-clinician relationships, make work within a clinical setting more efficient, and improve youth clinical outcomes. To illustrate how this definition was produced, we define MBC, review prior clinical utility definitions, discuss how the earlier work is used to define clinical utility for MBC, and provide examples of how the concept of clinical utility can be applied to MBC. The paper concludes with a presentation of future research directions.

What Is Measurement-Based Care?

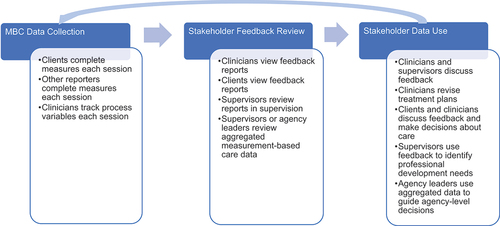

Numerous terms have been used to refer to MBC, such as clinical feedback, progress monitoring, monitoring and feedback, and routine outcome monitoring (Jensen-Doss et al., Citation2020). Here we define MBC as the systematic collection of data throughout treatment that key stakeholders – clients (defined as both youth and caregivers), clinicians, supervisors, and administrators – utilize to monitor treatment progress and guide clinical decision-making (e.g., identification of treatment targets, treatment selection, quality improvement; Scott & Lewis, Citation2015). MBC includes three components: (a) Routine collection of client-reported assessment data; (b) Stakeholder review of data; and (c) Use of data by stakeholders to inform and improve care quality (i.e., positive client-clinician relations and positive youth clinical outcomes). The key to this definition is that data collection and feedback are required to meet the definition of an MBC approach, as data collection without stakeholder review is not MBC. Standard practice is to administer client- or caregiver-report measures at or before each clinical encounter (Jensen-Doss et al., Citation2020; Scott & Lewis, Citation2015). Data from the measures are then analyzed, interpreted, and synthesized into a feedback report disseminated to stakeholders. Feedback reports facilitate communication between stakeholders and prompt decision-making and behavior change at the client, clinician, supervisor, and organizational levels (Connors et al., Citation2021; McLeod et al., Citation2021). However, who receives feedback reports differs across various MBC approaches; for example, some approaches only provide feedback reports directly to clinicians, whereas others offer feedback directly to clients. outlines the components of MBC, including examples of how various stakeholders can use MBC data to inform decision-making.

Effectiveness of Measurement-Based Care in Youth Treatment

A recent review summarizing MBC systematic reviews and meta-analyses for youth and adult treatment concluded that MBC showed a significant favorable influence on clinical outcomes relative to treatment as usual, particularly for clients who were not responding to treatment (Lewis et al., Citation2019). The most comprehensive meta-analysis conducted to date focused on youth and adult treatment concluded that MBC exerts a small but significant effect on clinical outcomes and treatment dropout (de Jong et al., Citation2021). These findings are promising, but the bulk of the effectiveness evidence for MBC comes from adult treatment (see, de Jong et al., Citation2021; Lewis et al., Citation2019). It thus is possible that these findings may not generalize to youth populations.

Compared to the adult literature, research focused on the effects of MBC in youth populations is limited. In 2018, a Cochrane review concluded that there was not enough evidence to draw conclusions about the impact of MBC on clinical outcomes in youth treatment (Bergman et al., Citation2018). A more recent review concluded that the effects of MBC in youth treatment appear to vary across settings (school-based treatment, individual treatment, group treatment; Parikh et al., Citation2020). However, definitive conclusions were not possible due to variations in the methodological quality of the studies reviewed (Parikh et al., Citation2020). A few critical studies suggest that MBC can promote positive clinical outcomes in youth treatment. First, a randomized controlled trial comparing MBC to usual care in youth samples found positive effects on clinical outcomes (Bickman et al., Citation2011). Second, a randomized controlled trial found MBC produced positive results, but only in cases where clinicians demonstrated sufficient fidelity to the MBC procedures (Bickman et al., Citation2016). Considered together, the evidence for the effectiveness of MBC in youth treatment is not established.

Clinical Utility

Most definitions of clinical utility from the mental health field have been produced for diagnostic systems (e.g., First et al., Citation2004; Reed, Citation2010), including continuous versus categorical approaches to diagnosing personality disorders (e.g., Milinkovic & Tiliopoulos, Citation2020) or evidence-based assessment writ large (e.g., Hunsley, Citation2003; Kamphuis et al., Citation2021). Applying the concept of clinical utility to MBC represents a natural extension of these efforts, so we provide a brief overview of these definitions before defining clinical utility for MBC.

A Brief History of Clinical Utility in Mental Health

Revisions to the DSM and ICD over the decades have been driven, in part, by the desire to improve the usefulness of these diagnostic systems (see, First et al., Citation2004; Keeley et al., Citation2016). Similar motivations have driven changes to conceptualizing and diagnosing personality disorders (i.e., categorical vs. dimensional approaches; e.g., Milinkovic & Tiliopoulos, Citation2020). Collectively, these efforts have suggested that classification systems must demonstrate evidence of clinical utility. Early definitions of clinical utility (e.g., First et al., Citation2004) focused on the extent to which a classification system assists clinicians in carrying out the various functions of that system (e.g., facilitating communication, choosing effective interventions). More recently, the World Health Organization generated a definition of clinical utility with five components (Keeley et al., Citation2016; Mullins-Sweatt et al., Citation2016): (a) Promote communication among users, (b) make conceptualization of mental disorders easier, (c) lead to the more straightforward implementation of the system among users, (d) make it easier for users to select treatments or manage clinical conditions, and (e) improve clinical outcomes (see, Keeley et al., Citation2016; Mullins-Sweatt et al., Citation2016; Reed, Citation2010; Reed et al., Citation2013; Roberts et al., Citation2012). Thus, clinical utility is related to how a system makes clinical work more efficient.

When applied to evidence-based assessment, clinical utility is typically defined as the extent to which the addition of assessment data improves typical clinical decision making clinical outcomes and decreases the financial and psychological costs associated with errors that might be made without the assessment data (Hunsley, Citation2003; Hunsley & Bailey, Citation1999; Kamphuis et al., Citation2021). Youngstrom (Citation2008) noted that the utility of assessment methods depends partly on how the data help answer one or more of the following questions: Do the assessment data predict essential criteria? Do the assessment data prescribe specific treatments? Do the assessment data inform our understanding of processes in developmental psychopathology? In other words, to justify using a particular assessment, research must indicate that the data provided by the measure is unique (not offered by other assessments) and improves upon standard clinical practice.

In sum, several themes cut across previous efforts to define clinical utility. First, implementability is emphasized, such that the approach or assessment must be cost-effective and easy to use in standard practice. Second, the approach’s usefulness is stressed, focusing on how an approach or assessment improves communication, decision making, or clinical outcomes. Next, we consider how to apply these themes to MBC.

Definition of Clinical Utility for MBC

We define clinical utility as evidence that an MBC approach assists stakeholders in fulfilling clinical goals related to care quality at the client (i.e., youth and caregiver), clinician, supervisor, and administrator levels within a particular clinical setting (First et al., Citation2004; Mullins-Sweatt et al., Citation2016). At a more granular level, we divide clinical utility into two categories: (a) implementability (i.e., evidence indicating ease of use in a particular clinical setting) and (b) usefulness in aiding clinical activities (i.e., evidence indicating the potential to improve communication and make clinical activities related to care quality easier or more effective). These categories provide unique information about how easy an MBC approach is to use and the potential benefits that the MBC data will have for stakeholders.

Critical to defining clinical utility is stating what it is and is not. There has been debate over the extent to which utility and validity overlap. Most authors agree that the two concepts are related but distinct (see, First et al., Citation2004; Kendell & Jablensky, Citation2003; Milinkovic & Tiliopoulos, Citation2020). We take a similar position – i.e., evidence for validity and clinical utility provide unique but inter-related information about MBC. Validity evidence speaks to the qualities of a specific measure used in MBC.

In contrast, evidence for clinical utility is judged based on the experience stakeholders have interacting with the various MBC components (including, but not limited to, measurement instruments) and using MBC data. To justify using a measure in MBC, it is necessary to know that it is easy to incorporate into an MBC approach and has a validity profile that supports the planned application of the measure within that approach. Yet knowing that the scores generated by a measure have a promising validity profile does not mean that the measure can be readily incorporated into a clinical setting or make clinical work more efficient or effective as part of MBC (see, Connors et al., Citation2021).

To illustrate this point, specific validity dimensions relevant to using a measure in MBC, such as predictive validity, are related closely to clinical utility as both speak to the effectiveness of clinical care. It is possible that changes to a measure that improves evidence for predictive validity could enhance its clinical utility because it could increase the measure’s potential to enhance the effectiveness of clinical practice. However, this outcome is not guaranteed. If, for example, improvements in predictive validity were produced by adding items to a measure, this could undermine clinical utility by making the measure more cumbersome and less efficient when used in MBC. By separating validity and clinical utility, we thus are distinguishing between validity evidence for measures used in MBC and the clinical utility of an MBC approach – i.e., evidence supporting score validity does not guarantee clinical utility and vice versa.

How the Design of MBC Components Can Influence Clinical Utility

As illustrated in , the design of each MBC component (data collection, stakeholder review, use of data) has implications for the clinical utility of an MBC approach. MBC approaches vary in how data are collected, how measures are administered (paper versus electronically) when they are issued (sent out before sessions, in the waiting room before sessions, during sessions), whether the measure administration is automated (clinician must manually administer measures, MBC approach syncs with an electronic health record to determine who should receive measures and sends them when sessions are scheduled), whether the MBC measures are uniform across clients or can be tailored, and how they are scored (by hand or electronically). Likewise, the measures have characteristics that can impact the utility, including their length, their relevance to stakeholders (e.g., developmentally appropriate for youth clients, available in appropriate languages, assesses problems or issues that are the focus of treatment, assesses processes that will inform care), and psychometric properties relevant to MBC (e.g., representative norms, availability of reliable change indices). MBC feedback reports vary along dimensions that can impact the utility, such as how quickly they are available (e.g., automatically scored and generated in an electronic approach versus being developed by hand by clinicians) and what feedback elements are available in the report to support clinical action (e.g., flagging suicide risk). MBC approaches similarly vary on characteristics related to the use of data across an organization, including the availability of reports to monitor MBC implementation or how easily data can be aggregated to support organizational operations. Components that are easy to use (e.g., intuitive, requires little learning, can be quickly adopted) are more likely to be perceived as having favorable implementation characteristics. Thus, changes to the components of an MBC approach can influence clinical utility.

The design and content of MBC components can also influence how stakeholders assess the usefulness of an MBC approach. For example, usefulness is impacted by the types of information gathered by measures and the design of the feedback reports (Nugter et al., Citation2019; Page et al., Citation2019). MBC can collect data on one, or more, of the following domains: client symptomatology, mechanisms of change (i.e., the means through which treatment produces a difference in youth clinical outcomes), therapy processes (i.e., what happens in treatment sessions with youth and their families), and aspects of the therapeutic relationship (e.g., quality of the client-clinician alliance). This information is disseminated to stakeholders via feedback reports. Feedback reports vary in the design of their feedback elements; some might just report scores or plots over time, whereas others might use visual displays or alerts to highlight areas of concern (e.g., significant deterioration in symptomatology, endorsement of danger to self/others, problems with the client-clinician alliance; e.g., Hooke et al., Citation2018; Peterson & Fagan, Citation2021). The focus of the measures and the design of the feedback reports determine what information stakeholders have access to and how easily digested it is, thus playing critical roles in determining the usefulness of MBC.

A final consideration is that stakeholders are likely to have different assessments of clinical utility as they often interact with distinct MBC components. Clinicians typically interact with the scoring system, feedback reports, feedback elements, and measures. Youth and their families primarily interact with the measures, administration method, and, in some instances, feedback reports. Supervisors and consultants primarily interact with feedback reports, feedback elements, and aggregated data. Administrators only typically interact with aggregated data, and any report that is produced based on the aggregated data. As stakeholders interact with various MBC components, clinical utility gathered from one stakeholder group may not generalize to other stakeholder groups. Next, we will dig deeper into the two categories of clinical utility.

Clinical Utility Dimension 1: Implementation Characteristics

A key aspect of clinical utility for an MBC approach is the extent to which the approach can be readily integrated into a clinical setting (see, ). Stakeholders will be less likely to adopt an MBC approach if it is not easy to use, a good fit for clinical activities, and practical to deploy. The implementation-relevant dimensions of an MBC approach can be conceptualized as (see, E. Proctor et al., Citation2011): (a) acceptability, defined as the perception by stakeholders that an MBC approach is agreeable or satisfactory), (b) appropriateness (i.e., perceived fit, relevance, or compatibility of the approach), and (c) feasibility (i.e., fit, suitability, practicability, and cost of the approach). These perceptual implementation outcomes speak to how stakeholders view the potential fit, relevance, and ease of using an MBC approach for a particular clinical setting. Information about these implementation outcomes provides decision-makers with data regarding how stakeholders will experience an MBC approach. As stakeholders interact with distinct MBC components (e.g., filling out measures, accessing feedback reports, see, ), our definition of implementability focuses on how each stakeholder perceives the particular MBC components they interact with within a specific clinical setting. provides examples of the types of questions different stakeholders might consider when assessing each implementation-relevant dimension.

Table 2. Clinical utility of measurement-based care approaches.

Acceptability and Appropriateness

The acceptability of an MBC approach is defined as the degree to which administrators, supervisors, clinicians, and clients perceive each MBC component they interact with as agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory (Proctor et al., Citation2011). Appropriateness focuses on how stakeholders perceive the goodness of fit, contextual appropriateness, and accuracy of the description of an MBC approach. This dimension captures the extent to which stakeholders view the MBC approach as compatible with their clinical activities and priorities. These two implementation outcomes are highly related and similar, so they are grouped here. Still, it is possible that an MBC approach might be found acceptable by stakeholders but viewed as inappropriate to their specific setting (E. Proctor et al., Citation2011). Before deployment, acceptability and appropriateness can be judged by stakeholders based on their knowledge of how the MBC approach is to be deployed within a clinical setting. In contrast, following deployment, stakeholders can consider these dimensions based on their experience interacting with the various MBC components.

As detailed in , for youth and their families, acceptability and appropriateness can be influenced by their experiences filling out measures and receiving feedback, as well as the perceived fit between the items on the measures, information in the feedback reports, and their reasons for seeking treatment (e.g., items do not have face validity). Judgments of acceptability and appropriateness by clinicians will be influenced by whether the MBC approach is consistent with their definition of good clinical practice, is a good fit for their client population (e.g., whether multiple languages are available, provides a relevant description of most/all youth), and fits with the way they work. Considerations at the supervisor level could include how much the MBC approach fits the supervisor’s approach to supervision or how they perceive the fit of the approach for the clinicians they supervise and the clients they treat. For administrators, factors that influence acceptability and appropriateness include whether they view the use of the MBC approach as consistent with good organizational practices and if the approach provides data relevant to the clinical mission of an organization (e.g., help promote clinically significant change).

Feasibility and Cost

Feasibility speaks to the extent to which stakeholders can successfully use the different components of the MBC approach within a particular clinical setting (E. Proctor et al., Citation2011). This implementation outcome includes the time it takes to fill out measures, analyze the data, and access feedback reports. It is essential to distinguish between feasibility and acceptability/appropriateness as stakeholders can believe an MBC approach is a good fit for the goals and priorities of an organization but find the components of an approach too challenging to implement. Cost includes the resources required to administer and score the measures (e.g., whether a trained clinician must administer the measure), analyze the data, and prepare/review feedback reports. Additional costs can include the time required to train stakeholders to use the system, equipment needed to run the MBC approach (e.g., tablets to administer the measures), and any support costs (Jensen-Doss, Citation2005; Yates & Taub, Citation2003). The feasibility and cost of an MBC approach can similarly influence uptake (Proctor et al., Citation2011), so we group them here. However, there are circumstances where one stakeholder group may emphasize one domain over the other (e.g., administrators placing greater emphasis on cost). Feasibility thus assesses how easily an MBC approach can be integrated into clinical practice from a time and cost perspective.

As illustrated in , feasibility issues focus primarily on practicality for youth, families, clinicians, and supervisors. Practicality for clients focuses on how easy it is to fill out the measures or access feedback reports. For clinicians, practicality focuses on the amount of time required for the administration method, scoring approach, and preparation of feedback reports. And for supervisors, time spent preparing feedback reports or aggregating data impacts feasibility. Administrators will be primarily concerned with the financial cost of an MBC approach to the organizational entity.

Clinical Utility Dimension 2: Usefulness

Usefulness represents the second broad category of clinical utility (see, ) and demonstrates that the MBC approach makes clinical work more efficient and effective. Specifically, usefulness considers the extent to which an MBC approach demonstrates its value relative to standard practice in one or more of the following areas: (a) improving communication and relations among stakeholders, (b) supporting stakeholder decision-making (e.g., diagnosis, treatment planning, treatment evaluation), and (c) making clinical work more effective or efficient (e.g., improving attendance or client clinical outcomes). These usefulness dimensions are interrelated, as improved communication and decision-making are thought to be the primary mechanisms by which MBC leads to increased treatment effectiveness (Jensen-Doss et al., Citation2020). However, as the types of evidence indicating utility in these three dimensions likely differ, it is helpful to consider them as three separate, but interconnected, utility dimensions.

Improving Communication and Relations among Stakeholders

An MBC approach can demonstrate usefulness through enhanced communication among stakeholders and improved relationships. For this dimension, communication is defined as discussions between stakeholders about treatment activities, goals, and youth clinical outcomes at the client, clinician, supervisor/consultant, or organizational level. Relationships among stakeholders can include the quality of the youth- and caregiver-clinician alliance (i.e., strong affective bond and agreement on the activities and goals of treatment; McLeod, Citation2011), quality of the clinician-supervisor alliance (i.e., strong affective bond and agreement on the activities and goals of supervision; McLeod et al., Citation2018), and the culture/climate of the organization (i.e., the expectations, norms, and sense of how things are done in an organization and the effect of the environment on the well-being of the employees; Hemmelgarn et al., Citation2006). Thus, this dimension captures the degree to which an MBC approach improves communication and relations among stakeholders relative to standard care.

As seen in , judgments of usefulness for youth and their families will be influenced by the extent to which an MBC approach improves communication and strengthens the relationship with the clinician. Clinicians will judge usefulness based on improvements in their communication and relationship with clients and enhancements in communication and relations with supervisors. At the supervisor/consultation level, the degree to which an MBC approach improves communication and relations with the clinician will impact the assessment of usefulness. MBC data may improve supervisors’ communication with clinicians and help strengthen their relationships with clinicians. Administrators will judge this dimension of usefulness based on how much MBC data help enhance communication among stakeholders, both within and outside of a clinical setting, and the extent to which the culture and climate of an organization are improved through the use of MBC.

Supporting Stakeholder Decision-Making

The second dimension of usefulness focuses on the degree to which an MBC approach demonstrates its value in supporting decision-making across stakeholders. For clinical care, decision-making is defined as a problem-solving process that involves identifying treatment targets (i.e., assessment of presenting problem, assigning a diagnosis), case conceptualization and treatment planning (i.e., selection and tailoring of an intervention), and treatment evaluation (i.e., need to revise the treatment plan when treatment is not going well, decisions about adding services, termination decisions; Jensen-Doss et al., Citation2020; McLeod et al., Citation2013). For organizational management purposes, decision-making is defined as a quality improvement process that represents systematic and continuous actions that lead to improvements in youth clinical outcomes, organizational functioning, and professional development (Batalden & Davidoff, Citation2007). Thus, this dimension captures the extent to which an MBC approach improves decision-making at the client or organizational level relative to standard care across stakeholders within a clinical setting.

As shown in , decision-making for youth and families involves the extent to which an MBC approach promotes understanding of their presenting problems and improves treatment planning. For clinicians, judgments for this dimension focus on the degree to which MBC enhances diagnosis, treatment planning, and treatment evaluation. At the level of the supervisor/consultant, judgments of usefulness are influenced by how much an MBC approach helps improve understanding of the diagnostic, treatment planning, and treatment evaluation process for clients on a clinician’s caseload and the benefits this has for identifying the professional development needs of individual clinicians. For administrators, assessment of this dimension will be influenced by the extent to which an MBC approach improves quality improvement initiatives.

Making Treatment More Effective or Efficient

This dimension refers to the degree to which the use of MBC improves the effectiveness or efficiency of treatment relative to treatment as usual. Effectiveness can be measured in terms of attendance, symptomatology, or functioning. Efficiency can be measured in how quickly gains are attained. Improvements in these outcomes can be measured at the client, caseload, or organizational level. Youth, families, and clinicians will be most concerned with improvements in these outcomes at the level of the individual client. Supervisors/consultants will be concerned with outcomes at the client and caseload levels, whereas administrators will be most concerned with outcomes at the organizational level.

Future Directions

Our definition of clinical utility is intended to help various stakeholders ascertain the pros and cons of adopting a specific MBC approach as part of standard care. Of course, no single study can establish clinical utility; evidence for clinical utility needs to be established via an accumulation of findings across studies. Moreover, an MBC approach can demonstrate promising clinical utility for a particular setting and stakeholders (e.g., outpatient setting and clinicians), but not show promise for another setting (e.g., pediatric setting and clinicians) or a different group of stakeholders within the same setting (e.g., outpatient setting and administrators). Therefore, evidence for clinical utility must be based on studies conducted within specific settings (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, pediatric) and the stakeholders who interact with the MBC approach within that setting (e.g., clients, clinicians, supervisors, administrators). It thus is appropriate to ask how the definition of clinical utility described herein can influence future research and broad-scale implementation. Multiple avenues of research are needed to help establish whether various MBC approaches demonstrate clinical utility. We, therefore, finish with a plan for future research.

What Characteristics of MBC Components Matter Most for Effectiveness?

As detailed in , the components of MBC approaches can vary in several ways. The field would benefit from research examining how altering the design of MBC components impacts effectiveness. To date, most MBC studies have employed methods that compare an MBC approach to a control condition where MBC data are collected but not routinely fed back to clinicians (de Jong et al., Citation2021). While a limited number of studies have compared the effectiveness of MBC approaches that employ different components on client outcomes (Harmon et al., Citation2007; Slade et al., Citation2008), there is a need for comparative research to identify what characteristics of MBC components are most effective.

Design of Feedback Reports Promoting Behavioral Change

There is limited understanding of how feedback should be presented to motivate clinical behavior change and promote positive clinical outcomes (Lyon et al., Citation2016; Tam & Ronan, Citation2017). While a few studies have examined clinician and client preferences related to how feedback is presented in feedback reports (e.g., Hepner et al., Citation2019), very little work has examined which types of feedback are most effective in leading to improved clinical outcomes, particularly in the context of youth mental health care. Theory-guided studies with youth samples are needed to identify how best to design feedback to motivate clinician behavior change and optimize MBC effectiveness. Riemer and Bickman (Citation2011) proposed the contextualized feedback intervention theory (CFIT), a theoretical model for how MBC feedback can improve clinical outcomes in mental health care. CFIT draws from self-regulatory and control theories (e.g., Carver & Scheier, Citation1998), which propose that feedback influences behaviors through a regulatory process wherein individuals adjust their behavior when they perceive that a discrepancy between their current behavior and their goals exists. In the case of MBC, this discrepancy would be based on feedback that a client is not progressing in treatment (for a detailed description of CFIT see, Riemer & Bickman, Citation2011).

CFIT provides several ideas about how feedback should be designed to leverage clinician behavior change. For example, feedback reports should be more effective if they compare client outcomes to established benchmarks for determining whether treatment is on track for positive clinical outcomes, such as empirically-derived trajectories of expected treatment response (e.g., Lambert et al., Citation2002). Riemer and Bickman (Citation2011) also proposed that feedback that includes therapy process information, such as information about the alliance, should increase the utility of feedback. Lessons learned from the audit and feedback literature from healthcare settings may also have implications for the design of feedback reports. A Cochrane review (Ivers et al., Citation2012) of the audit and feedback literature concluded feedback might be most effective when: (a) health professionals are not performing well; (b) feedback is provided more than once; (c) feedback is given both verbally and in writing; and (d) feedback includes clear goals and an action plan. However, there are key differences between healthcare and mental health care (e.g., singular visits vs. weekly meetings; complex multi-session intervention) that raise questions about the extent to which these findings from the audit and feedback literature will generalize to mental health care (Kilbourne et al., Citation2018). Theory-informed research in youth mental healthcare is needed to test these hypotheses to determine how best to design feedback reports to motivate clinicians to engage in behavior change and maximize youth clinical outcomes.

Innovative Methods to Assess and Enhance the Implementability and Usefulness of MBC Components

As with evidence-based practices more generally (Lewin et al., Citation2017), different MBC approaches vary in complexity and how readily they can be implemented in community contexts. As noted in , the components of MBC approaches can differ in important ways (e.g., measures used, administration methods, feedback reports/elements) that may make a component more helpful or usable within specific different settings or by various stakeholders. Therefore, research exploring methods of optimizing the design of MBC components to improve both implementation and clinical outcomes would be helpful to promote clinical utility. Methods drawn from the literature on human-centered design (HCD) – a field focused on aligning innovations with the stakeholders and settings that use those products (Norman & Draper, Citation1986) – may be beneficial to examine the ease of use and identify opportunities to reduce complexity, increase alignment with user needs, and promote positive clinical outcomes. HCD has recently been leveraged to enhance the quality of youth and adult mental health services (e.g., Lyon, Dopp et al., Citation2020; Lyon et al., Citation2019), especially surrounding the evaluation of usability; often operationalized as including both “ease of use” and “usefulness” (Lund, Citation2001). Future studies could seek to enhance the usability of MBC components via testing methods drawn from HCD (Dopp et al., Citation2019) and those adapted explicitly for application to complex psychosocial processes such as MBC (Lyon, Koerner, et al., Citation2020)

Evaluating Which MBC Components Function as Mediators of Behavioral MBC Implementation Outcomes or Moderators of MBC Impact

Also needed are implementation-focused studies that seek to determine the extent to which aspects of MBC clinical utility (including implementation and usefulness; see, ) function as mediators of implementation outcomes such as clinicians’ MBC adoption (i.e., MBC initiation or first-time use) or fidelity (i.e., MBC use as intended; sometimes defined as administration, data review, and feedback to clients; Lewis et al., Citation2015; Scott & Lewis, Citation2015). Some of these studies might be conceptualized within frameworks such as the Technology Assessment Model (TAM), which was initially proposed to explain factors that accounted for the use of technologies by users (Marangunić & Granić, Citation2015). Consistent with elements detailed in , the TAM hypothesizes that user perceptions of ease of use and usefulness ultimately dictate use behaviors. Originally based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation2011), the components of the TAM have received extensive empirical support (see, Marangunić & Granić, Citation2015). Though research will need to establish the relations between ease of use, usefulness, and successful implementation of an MBC approach within clinical settings, the TAM represents a starting point for conceptualizing the interplay among these components. This model can help researchers understand how these proposed dimensions of clinical utility may interrelate to influence the use of an MBC approach. It also provides direction for implementation studies seeking to address significant knowledge gaps surrounding the mechanisms through which implementation strategies impact implementation outcomes (Lewis et al., Citation2020). Implementation strategies are methods or techniques used to enhance outcomes, such as adopting, using, and sustaining evidence-based practices (Proctor et al., Citation2013). Relatively few studies have explored how MBC implementation strategies (e.g., training with active learning, adaptive measurement feedback systems, formation of implementation teams) affect positive implementation outcomes (Lewis et al., Citation2019).

Developing More Passive Approaches to Data Collection to Increase Feasibility

To maximize the clinical utility of MBC approaches, it will be essential to leverage the digital revolution in healthcare delivery (Keesara et al., Citation2020). Current approaches to MBC focus on “pull,” or asking clients to report on their symptoms and experiences. There is great promise in developing more passive methods to collect this data to reduce client burden and taking advantage of the devices that individuals carry with them at all times (i.e., smartphones; Chiauzzi & Wicks, Citation2021). Much more work is needed to understand which data sources are most informative to clinicians and clients and issues related to privacy that may affect user comfort with accessing different data sources. However, the vision for the future includes an opportunity for highly pragmatic measurement of the client experience, which can be seamlessly fed into the clinical encounter and beyond.

Working with Stakeholders to Understand How Best to Incorporate MBC Approaches into Existing Workflows

To maximize clinical utility, it is critical to work with all stakeholders (i.e., payers, administrators, clinicians, clients, families) to understand how best to incorporate these approaches into existing workflows and clinician decision support systems. For example, there is a rich literature on incorporating nudges into clinician decision-making in healthcare contexts (Last et al., Citation2021). Nudges have effectively increased referral to cardiac rehabilitation, decreased opioid prescriptions, and increased cancer prevention delivery (Patel et al., Citation2020). An area ripe for exploration is the use of MBC as a top-down strategy to promote organizational learning within agencies and across institutions to support a learning health care system. This is particularly true in the U.S., which is behind other countries that have benefited from system-level MBC policies to use aggregated data for system improvement (Connors et al., Citation2021; Jensen-Doss et al., Citation2020). A better understanding of stakeholder value and use of MBC data at all levels, from the bottom (i.e., session) up through levels of increasing aggregation, can help illustrate how a “golden thread” of patient-centered and clinically relevant data (Douglas et al., Citation2016) can spur practice improvement.

MBC is a complex intervention with the potential for differential impact across stakeholder groups and treatment settings. While perceptions of clinical utility are primarily driven by ‘what is’ about current clinical activities, priorities, and workflows, it is essential to assess ‘what could be’ in how MBC can transform learning and organizational culture as data-informed decision-making takes root and influences different process and outcomes. Evaluation approaches, such as the normalization process theory (e.g., May et al., Citation2018) that acknowledge the dynamic nature of MBC implementation and the social context in which such innovation occurs will be essential to integrate into the exploration of MBC components user-centered approaches previously mentioned here. There is a tremendous opportunity to merge these approaches to make MBC the right thing to do and the easy thing to do (Beidas et al., Citation2021).

Working with Payers and Policymakers so MBC Approaches that Demonstrate Utility are Reimbursable

For MBC to truly achieve its promise, it must be reimbursable. Payers are interested in MBC because it offers a potential window into high-quality care and what is often viewed as a black box – the therapeutic encounter. Until clinicians can bill for MBC activities in a fee-for-service environment, and organizations see the utility in collecting MBC in value-based models, it is unlikely that MBC will be adopted at scale, particularly given the financial realities of mental health care in the United States (Stewart et al., Citation2021).

In closing, MBC has the potential to improve the quality of mental health services for youth and their families. By defining clinical utility for MBC, we hope to generate new research that can be used to evaluate whether MBC systems are easy to implement within clinical settings and help to make clinical work more effective, easier, or both.

Disclosure Statement

Rinad Beidas, PhD, receives royalties from Oxford University Press. She provides consultation to United Behavioral Health. She sits on the Clinical and Scientific Advisory Committee for Optum Behavioral Health; the Scientific Advisory Board for AIM Youth Mental Health Foundation; and the Scientific Advisory Committee for the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation.

Vanderbilt University and Susan Douglas receive compensation related to the Peabody Treatment Progress Battery; and Susan Douglas has a financial relationship with MIRAH, and both are Measurement -Based Care (MBC) tools. The author declares a potential conflict of interest. There is a management plan in place at Vanderbilt University to monitor that this potential conflict does not jeopardize the objectivity of Dr. Douglas’ research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- American Psychological Association. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61(4), 271–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271

- Batalden, P. B., & Davidoff, F. (2007). What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Quality and Safety in Health Care, 16(1), 2–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2006.022046

- Beidas, R. S., Buttenheim, A. M., & Mandell, D. S. (2021). Transforming mental health care delivery through implementation science and behavioral economics. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(9), 941–942. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1120

- Bergman, H., Kornør, H., Nikolakopoulou, A., Hanssen‐Bauer, K., Soares‐Weiser, K., Tollefsen, T. K., & Bjørndal, A. (2018). Client feedback in psychological therapy for children and adolescents with mental health problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 20(8), CD011729. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011729.pub2

- Bickman, L., Douglas, K. S., Breda, C., De Andrade, A. R. V., & Riemer, M. (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1423–1429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.002052011

- Bickman, L., Douglas, S. R., De Andrade, A. R., Vides, Tomlinson, M., Gleacher, A., Olin, S., & Hoagwood, K. (2016). Implementing a measurement feedback system: A tale of two sites. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 410–425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0647-8

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-regulation of behavior. Cambridge University Press.

- Chiauzzi, E., & Wicks, P. (2021). Beyond the Therapist’s office: Merging measurement-based care and digital medicine in the real world. Digital Biomarkers, 5(2), 176–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000517748

- Coalition for the Advancement and Application of Psychological Science. (2018). “Evidence-based practice decision-making for mental and behavioral health care.” Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.caaps.co/consensus-statement

- Connors, E. H., Douglas, S., Jensen-Doss, A., Landes, S. J., Lewis, C. C., McLeod, B. D., Stanick, C., & Lyon, A. R. (2021). What gets measured gets done: How mental health agencies can leverage measurement-based care for better patient care, clinician supports, and organizational goals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 48, 250–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01063-w

- de Jong, K., Conijn, J. M., Gallagher, R. A., Reshetnikova, A. S., Heij, M., & Lutz, M. C. (2021). Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce dropout, treatment duration, and deterioration: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 102002. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

- Dopp, A. R., Parisi, K. E., Munson, S. A., & Lyon, A. R. (2019). A glossary of user-centered design strategies for implementation experts. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 9(6), 1057–1064. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby119

- Douglas, S., Button, S., & Casey, S. E. (2016). Implementing for sustainability: Promoting use of a measurement feedback system for innovation and quality improvement. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 286–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0607-8

- First, M. B., Pincus, H. A., Levine, J. B., Williams, J. B. W. W., Ustun, B., & Peele, R. (2004). Clinical utility as a criterion for revising psychiatric diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(6), 946–954. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.946

- Harmon, S. C., Lambert, M. J., Smart, D. M., Hawkins, E., Nielsen, S. L., Slade, K., & Lutz, W. (2007). Enhancing outcome for potential treatment failures: Therapist–client feedback and clinical support tools. Psychotherapy Research, 17(4), 379–392. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600702331

- Hemmelgarn, A. L., Glisson, C., & James, L. R. (2006). Organizational culture and climate: Implications for services and interventions research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00008.x

- Hepner, K. A., Farmer, C. M., Holliday, S. B., Bharil, S., Kimerling, R. E., McGee-Vincent, P., McCaslin, S. E. & Rosen, C. (2019). Displaying behavioral health measurement-based care data: Identifying key features from clinician and patient perspectives. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3078.html

- Hooke, G. R., Sng, A. A. H., Cunningham, N. K., & Page, A. C. (2018). Methods of delivering progress feedback to optimise patient outcomes: The value of expected treatment trajectories. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(2), 204–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9851-z

- Hunsley, J. (2003). Introduction to the special section on incremental validity and utility in clinical assessment. Psychological Assessment, 15(4), 443–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.443

- Hunsley, J., & Bailey, J. M. (1999). The clinical utility of the Rorschach: Unfulfilled promises and an uncertain future. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 266–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.266

- Hunsley, J., & Mash, E. J. (2007). Evidence-based assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091419

- Ivers, N., Jamtvedt, G., Flottorp, S., Young, J. M., Odgaard-Jensen, J., French, S. D., O’Brien, M. A., Johansen, M., Grimshaw, J., & Oxman, A. D. (2012). Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, CD000259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3

- Jensen-Doss, A. J. (2005). Evidence-based diagnosis: Incorporating diagnostic instruments into clinical practice. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(9), 947–952. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000171903.16323.92

- Jensen-Doss, A., Douglas, S., Phillips, D. A., Gencdur, O., Zalman, A., & Gomez, N. E. (2020). Measurement-based care as a practice improvement tool: Clinical and organizational applications in youth mental health. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 5(3), 233–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1784062

- The Joint Commission. (2018). Revised outcome measures standard for behavioral health care. R3 Report: Requirement, Rationale, Reference. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/R3_Outcome_measures_1_30_18_FINAL.pdf

- Kamphuis, J. H., Noordhof, A., & Hopwood, C. J. (2021). When and how assessment matters: An update on the Treatment Utility of Clinical Assessment (TUCA). Psychological Assessment, 33(2), 122–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000966

- Keeley, J. W., Reed, G. M., Roberts, M. C., Evans, S. C., Medina-Mora, M. E., Robles, R., Robello, T., Sharan, P., Gureje, O., First, M. B., Andrews, H., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Gaebel, W., Zielasek, J., & Saxena, S. (2016). Developing a science of clinical utility in diagnostic classification systems field study strategies for ICD-11 mental and behavioral disorders. American Psychologist, 71(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039972

- Keesara, S., Jonas, A., & Schulman, K. (2020). Covid-19 and health care’s digital revolution. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(23), e82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005835

- Kendell, R., & Jablensky, A. (2003). Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.4

- Kendrick, T., El-Gohary, M., Stuart, B., Gilbody, S., Churchill, R., Aiken, L., Bhattacharya, A., Gimson, A., Brütt, A. L., de Jong, K., & Moore, M. (2016). Routine use of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) for improving treatment of common mental health disorders in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 13(7), CD011119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011119.pub2

- Kilbourne, A. M., Beck, K., Spaeth-Rublee, B., Ramanuj, P., O’Brien, R. W., Tomoyasu, N., & Pincus, H. A. (2018). Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: A global perspective. World Psychiatry, 17(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20482

- Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Bishop, M. J., Vermeersch, D. A., Gray, G. V., & Finch, A. E. (2002). Comparison of empirically-derived and rationally-derived methods for identifying patients at risk for treatment failure. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 9(3), 149–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.333

- Last, B. S., Buttenheim, A. M., Timon, C. E., Mitra, N., & Beidas, R. S. (2021). Systematic review of clinician-directed nudges in healthcare contexts. BMJ Open, 11(7), e048801. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048801

- Lewin, S., Hendry, M., Chandler, J., Oxman, A. D., Michie, S., Shepperd, S., Reeves, B. C., Tugwell, P., Hannes, K., Rehfuess, E. A., Welch, V., Mckenzie, J. E., Burford, B., Petkovic, J., Anderson, L. M., Harris, J., & Noyes, J. (2017). Assessing the complexity of interventions within systematic reviews: Development, content and use of a new tool (iCAT_SR). BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0349-x

- Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M., Puspitasari, A., Navarro, E., Howard, J., Kassab, H., Hoffman, M., Scott, K., Lyon, A., Douglas, S., Simon, G., & Kroenke, K. (2019). Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: A review. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(3), 324–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

- Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M. R., Walsh-Bailey, C., Lyon, A. R., Beidas, R., Mittman, B., Aarons, G. A., Weiner, B. J., & Chambers, D. A. (2020). A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implementation Science, 15(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-00983-3

- Lewis, C. C., Scott, K., Marti, C. N., Marriott, B. R., Kroenke, K., Putz, J. W., Mendel, P., & Rutkowski, D. (2015). Implementing measurement-based care (iMBC) for depression in community mental health: A dynamic cluster randomized trial study protocol. Implementation Science, 10(1), 127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0313-2

- Lund, A. (2001). Measuring usability with the USE questionnaire. Usability Interface, 8, 3–6.

- Lyon, A. R., Dopp, A. R., Brewer, S. K., Kientz, J. A., & Munson, S. A. (2020). Designing the future of children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(5), 735–751. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01038-x

- Lyon, A. R., Koerner, K., & Chung, J. (2020). Usability Evaluation for Evidence-Based Psychosocial Interventions (USE-EBPI): A methodology for assessing complex intervention implementability. Implementation Research and Practice, 1, 2633489520932924. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489520932924

- Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M. R., Hendrix, E., & Liu, F. (2016). Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: Results from a comprehensive review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 441–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

- Lyon, A. R., Munson, S. A., Renn, B. N., Atkins, D. C., Pullmann, M. D., Friedman, E., & Areán, P. A. (2019). Use of human-centered design to improve implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in low-resource communities: Protocol for studies applying a framework to assess usability. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(10), e14990. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/14990

- Marangunić, N., & Granić, A. (2015). Technology acceptance model: A literature review from 1986 to 2013. Universal Access in the Information Society, 14(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-014-0348-1

- May, C. R., Cummings, A., Girling, M., Bracher, M., Mair, F. S., May, C. M., Murray, E., Myall, M., Rapley, T., & Finch, T. (2018). Using normalization process theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 13(1), 80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0758-1

- McLeod, B. D. (2011). The relation of the alliance with outcomes in youth psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(4), 603–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.001

- McLeod, B. D., Cook, C., Sutherland, K. S., Lyon, A. R., Dopp, A., Broda, M., & Beidas, R. S. (2021). A theory-informed approach to locally-managed learning school systems: Integrating treatment integrity and student outcome data to promote student mental health. School Mental Health. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09413-1

- McLeod, B. D., Cox, J. R., Jensen-Doss, A., Herschell, A., Ehrenreich-May, J., & Wood, J. J. (2018). Proposing a mechanistic model of training and consultation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12260

- McLeod, B. D., Jensen-Doss, A., & Ollendick, T. H. (2013). Case conceptualization, treatment planning and outcome monitoring. In B. D. McLeod, A. Jensen-Doss, & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Diagnostic and behavioral assessment in children and adolescents: A clinical guide (pp. 77–102). Guilford Publications, Inc.

- Milinkovic, M. S., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2020). A systematic review of the clinical utility of the DSM–5 section III alternative model of personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11(6), 377–397. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000408

- Mullins-Sweatt, S. N., Lengel, G. J., & DeShong, H. L. (2016). The importance of considering clinical utility in the construction of a diagnostic manual. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 133–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-092954

- Norman, D. A., & Draper, S. W. (1986). User centered system design: New perspectives on human-computer interaction (1st ed.). CRC Press.

- Nugter, M. A., Hermens, M. L. M., Robbers, S., Son, G. V., Theunissen, J., & Engelsbel, F. (2019). Use of outcome measurements in clinical practice: How specific should one be? Psychotherapy Research, 29(4), 432–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1408975

- Page, A. C., Camacho, K. S., & Page, J. T. (2019). Delivering cognitive behaviour therapy informed by a contemporary framework of psychotherapy treatment selection and adaptation. Psychotherapy Research, 29(8), 971–973. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1662510

- Parikh, A., Fristad, M. A., Axelson, D., & Krishna, R. (2020). Evidence based for measurement-based care in child and adolescent psychiatry. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(4), 587–599. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2020.06.001

- Patel, M. S., Navathe, A. S., & Liao, J. M. (2020). Using nudges to improve value by increasing imaging-based cancer screening. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 17(1), 38–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2019.08.025

- Peterson, A. P., & Fagan, C. (2021). Improving measurement feedback systems for measurement-based care. Psychotherapy Research, 31(2), 184–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1823031

- Proctor, E. K., Powell, B. J., & McMillen, J. C. (2013). Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science, 8(1), 139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Reed, G. M. (2010). Toward ICD-11: Improving the clinical utility of WHO’s international classification of mental disorders. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41(6), 457–464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021701

- Reed, G. M., Roberts, M. C., Keeley, J., Hooppell, C., Matsumoto, C., Sharan, P., Robles, R., Carvalho, H., Wu, C., Gureje, O., Leal-Leturia, I., Flanagan, E., Mendonça Correia, J., Maruta, T., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Mari, J. D. J., Xiao, Z., Evans, S. C., Saxena, S., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2013). Mental health professionals’ natural taxonomies of mental disorders: Implications for the clinical utility of the ICD-11 and the DSM–5. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(12), 1191–1212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22031

- Riemer, M., & Bickman, L. (2011). Using program theory to link social psychology and program evaluation. In M. M. Mark, S. I. Donaldson, & B. Campbell (Eds.), Social Psychology and Evaluation (pp. 102–139). Guilford Press.

- Roberts, M. C., Reed, G. M., Medina-Mora, M. E., Keeley, J. W., Sharan, P., Johnson, D. K., Mari, J. D. J., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Gureje, O., Xiao, Z., Maruta, T., Khoury, B., Robles, R., & Saxena, S. (2012). A global clinicians’ map of mental disorders to improve ICD-11: Analysing meta-structure to enhance clinical utility. International Review of Psychiatry, 24(6), 578–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2012.736368

- Scott, K., & Lewis, C. C. (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010

- Slade, K., Lambert, M. J., Harmon, S. C., Smart, D. W., & Bailey, R. (2008). Improving psychotherapy outcome: The use of immediate electronic feedback and revised clinical support tools. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 15(5), 287–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.594

- Stewart, R. E., Mandell, D. S., & Beidas, R. S. (2021). Lessons From Maslow: Prioritizing funding to improve the quality of community mental health and substance use services. Psychiatric Services, 72(10), 1219–1221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000209

- Tam, H. E., & Ronan, K. (2017). The application of a feedback-informed approach in psychological service with youth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 41–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.005

- Umscheid, C. A. (2010). Maximizing the clinical utility of comparative effectiveness research. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 88(6), 876–879. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2010.200

- Yates, B. T., & Taub, J. (2003). Assessing the costs, benefits, cost-effectiveness, and cost-benefit of psychological assessment: We should, we can, and here’s how. Psychological Assessment, 15(4), 478–495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.478

- Youngstrom, E. (2008). Evidence-based strategies for the assessment of developmental psychopathology: Measuring prediction, prescription, and process. In W. E. Craighead, D. J. Miklowitz, & L. W. Craighead (Eds.), Psychopathology: History, diagnosis, and empirical foundations (pp. 34–77). John Wiley & Sons Inc.